Article

Brother Slattery Wins an Essay Contest

An Irish Christian Brother’s Influence on Education Reform in 1890s Newfoundland

En 1890, le gouvernement de Terre-Neuve organisa un concours de rédaction pour solliciter des opinions sur la meilleure façon de réformer son système d’éducation. Il était largement reconnu que le système ne fournissait pas une éducation de qualité aux enfants de la colonie. La menace qui en résultait pour le contrôle des églises sur les écoles incita le frère chrétien d’Irlande John Slattery à s’inscrire au concours de rédaction. Slattery remporta le concours, quoique sa victoire ait été douteuse. Il proposa une approche prudente en préconisant que la réforme en éducation soit dirigée par les églises, ce qui mena à un paradigme de coopération confessionnelle qui consacra le contrôle des églises sur l’éducation à Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador durant plus d’un siècle.

In 1890, the Newfoundland government held an essay contest to solicit opinions on how best to reform its education system. There was widespread acknowledgement that the system was failing to provide a quality education for the colony’s children. The threat to churches’ control over schools led Irish Catholic Christian Brother John Slattery to enter the essay contest. Slattery was victorious, though his win was dubious. He proposed a church-led conservative approach to educational reform, which led to the rise of a cooperative denominational paradigm that entrenched church control over schooling in Newfoundland and Labrador for more a century.

1 IN THE FALL OF 1890, THE NEWFOUNDLAND GOVERNMENT APPOINTED a committee to enquire into the state of education and explore ideas to address the colony’s educational challenges. The Select Committee on Education solicited the advice of leading educationalists in the colony through an essay contest. On 28 January 1891, it was announced in the Evening Telegram that Brother John Luke Slattery, a Roman Catholic Irish Christian Brother and principal of St. Bonaventure’s College, was the winner.1 Slattery’s essay made numerous suggestions that in slightly modified form became legislation. His key suggestion – the creation of a Council for Higher Education (CHE) on a denominational and not democratic or secular basis – was established in law in 1893.2

2 The story of Slattery’s winning essay and the creation of the CHE offers insight into how leading denominational educationalists influenced and shaped Newfoundland’s public education system to maintain their ideal balance of power. The essay contest occurred in the British Atlantic world, which was shaped by rivalries for influence among Christian denominations who sought continued influence on society.3 Newfoundland possessed a uniquely divided denominational school system – not only did the state fund a separate Catholic system as well as Church of England and Methodist systems but, later on in the 20th century, also separate Salvation Army, Seventh Day Adventist, and Pentecostal systems – and its educationalists watched and were influenced by events, debates, and decisions in the Canadian provinces as well as in the United States, Ireland, and England. As the drama of the essay contest and ensuing legislative debates unfolded, leading educationalists like Slattery were influential in the process both because of their expertise and their ties to voting communities.4

3 The 19th century saw the rise of public education systems, which were intimately tied to projects of state and empire building.5 Newfoundland’s government sought to ensure schools were available to its citizens, even those who lived in distant outports where there was little government presence.6 The rise of non-sectarian systems and loss of Catholic school systems in the wider Atlantic world worried Newfoundland Catholics. The order of the Christian Brothers was created to foster a sense of Catholic community through their schools and to shore up Catholicism’s social influence.7 The Newfoundland Brothers strove to achieve those ends through shaping educational policy in the colony, and their goals aligned with local church leaders who were deeply invested in building up Newfoundland.8 According to the government, education in Newfoundland was focused on shaping productive and moral citizens as well as enabling some social mobility. The means of providing that education was a complex scheme built on a continual negotiation of the balance of power between various churches and the colonial state. This complex church-state relationship shaped the character of the Newfoundland state and the lives of its citizens through influencing the character of the colony’s education system. The pressures of modernity, such as new common educational standards, and demand for scientific knowledge – pressures that were the result of the growing interconnectedness of the world – were factors that contributed to the initial essay contest and shaped the reform debates in Newfoundland. Further, developing national education systems came to be seen as important for constructing national communities in settler nations.9 Newfoundland’s response to a call from politicians, teachers, and clergy for school reform to meet the challenges of modernity and rising educational standards within the British Empire was intimately tied to how religious leaders in the colony envisioned educational innovation within the existing denominational paradigm. These mostly male figures were interested in reforming the education system through improving the intellectual quality of the system and encouraging people to participate in schooling.10 They hoped an increase in school attendance would enable social mobility, contribute to economic growth, and improve the lives of citizens through their access to superior teachers and new forms of knowledge. These men, chief among them the denominational superintendents, celebrated Slattery and the creation of the CHE because it enabled Newfoundland students and teachers to meet standards in place elsewhere as well as for its centralizing effect on the loosely connected denominational schools. This story is simultaneously a local and Atlantic world story that reveals how denominationalists entrenched their role in managing Newfoundland’s schools. Their success demonstrates the existence of a vibrant collaborative conservatism in Newfoundland founded on an acceptance of denominational pluralism. Newfoundland politicians and citizens accepted denominational pluralism in the public sphere, meaning that no one Christian group was seen as superior and that all were viewed as deserving of recognition and consideration in the making of policies that affected their communities and spheres of influence.11 Newfoundland’s church leaders were aware of the need to be leaders in educational reform to retain their influence on society and advocated for education reform in a way that included other churches, which reinforced public acceptance of denominational voices in politics and the view that churches were a constructive social force in the colony.

4 Scholars such as Gertrude Gunn and Philip McCann have depicted Newfoundland’s denominational education system as a sectarian mess, but that descriptor is misleading as it misses church leaders and educators’ efforts to shape the denominational system to support the colony’s social and economic development.12 Denominational education was inaugurated in 1874 and lasted until 1997, though its roots were planted in the 1830s and 1840s. It was indeed sectarian in that the system after 1874 was characterized by multiple church-run education systems funded by an education grant from the colonial government based on population. However, the term sectarian implies violence between groups and, as Jerry Bannister has argued in his assessment of Newfoundland historiography, there was little actual sectarian violence in late 19th century outside of a handful localized events such as the Harbour Grace Affray of 1883.13

5 Further, as scholars such as Carolyn Lambert, John Fitzgerald, Patrick Manion, and Colin Barr have shown, Newfoundland Roman Catholics, while seeing themselves as part of the Irish Catholic diaspora that needed Catholic institutions, actively participated in developing Newfoundland’s economic and civic institutions and saw themselves as part of Newfoundland society.14 The successful incorporation of Catholics into society over the course of the second half of the 19th century was in part due to their participation in crafting a shared optimistic nationalist ethos that was pro-economic development in Newfoundland, which all churches sought to support.15 This runs contrary to a longstanding argument in Newfoundland historiography that churches, according to scholars such as Greene, Gunn, and McCann, undermined the development of the colony; but such scholars have not studied churches’ efforts to support and stimulate social and economic development.16 And Newfoundland certainly struggled to provide education for its citizens; according to the 1891 census there were 29,769 children attending school while some 37,664 did not, and educational reports from the superintendents show great concern over the low amount of education that the majority of children received.17 Calls for reform to improve the quality of schools were in the air in the 1890s, but the course this reform should take was subject to debate. Yet these debates over possible changes have received minimal to no discussion in the literature, pointing to a need to evaluate denominationalists’ perspectives and impact on Newfoundland’s education system and the significance of its denominational character.

Newfoundland develops a denominational education system

6 In 1836, the relatively new representative House of Assembly of Newfoundland passed the “Act for the Encouragement of Education.” It provided aid to several groups who had established schools in the colony, such as the Sisters of the Presentation’s convent school, the Newfoundland School Society for the Poor (Church of England), the Orphan Asylum School of the Benevolent Irish Society, and St. Patrick’s School (a grammar school in Harbour Grace). Politicians, including Governor Prescott, openly celebrated the beginning of a relationship between religious groups and the government and the good influence on society they envisioned would result from churches’ connection to schools.18 Crucially, this act also laid the foundation for a public school system by providing funding for public boards to create schools throughout the colony. Senior clergy of all denominations within a district, according to the law, had a reserved seat on these boards, which marked them as interdenominational while also formalizing church influence over education.19

7 The decades that followed the 1836 act saw intense debate over who should administer the schools, how they should be conducted, and who should set curriculum. In 1843, Methodists led a successful crusade to push Roman Catholics off interdenominational boards because Catholics objected to use of the Bible as a textbook. The Education Act of 1843 stated that Catholics were entitled to half the education grant based on the fact that they were half of population.20 The law did not declare a right to a separate system, but the right of churches to portions of the education grant. The result was two systems, one Catholic and one Protestant. However, with the arrival of Tractarian bishop Edward Feild from England in 1844, unity amongst the Protestants proved difficult to maintain.21

8 Feild constantly lobbied for an Anglican school system, as in what existed in England, and in doing so he alienated other Protestants.22 From the 1840s to the 1860s, there was constant debate over splitting the Protestant grant. John Haddon, a Wesleyan Methodist who was appointed as the first Protestant school inspector in 1858, reported during the course of his tenure (1858-1874) that he had to grapple with politicking Anglicans and the desire for separate schools by Methodists. Part of the desire for separate schools was rooted in how the board system worked.23 Boards had to include clergy based on a region’s population, and tended to be dominated by one denomination, but such boards often had to administer schools in small communities that differed from the board’s denominational composition.

9 A further issue was that neither Haddon nor his Catholic counterpart held real power under the 1858 act. The boards were not supervised or accountable to any meaningful authority; the governor had theoretical legal oversite, but he did not play an active role in managing schools.24 This created a standardization problem and a need for centralizing reform. Sub-division of the Protestant grant between the different Protestants denominations was seen as a solution to this problem because denominational boards were open to working with a centralized denominationally affiliated body or official. Haddon opposed sub-division, but he constantly stated that centralizing reform was desperately needed. Yet the government dithered and passed no meaningful changes to the system during his tenure. In 1873, the debate over dividing schools came to a boil due to three factors: Feild’s lobbying, clergy’s reactions to census information that showed Anglicans accounted for a near equal portion of the population as Catholics (and Methodists nearly 20 per cent); and an incident in 1873 where the Methodist-controlled Brigus board tried to install a Wesleyan teacher in an Anglican community.25

10 As denominational tensions and lobbying peaked, Haddon wrote: “The great controversy on national education is whether the public schools shall be denominational or unsectarian; and lest the question should be started by our legislators, I beg to be allowed to give my testimony to the value and acceptability of the religious and moral instruction imparted in the Protestant board schools. . . . We are a Christian people, and hold it to be of paramount importance that children shall be taught the leading doctrines of the Christian faith . . . .”26 Haddon highlighted the celebration of religious teachings, the missionary role of teachers, and the social good created by church ties to schools. But while he was optimistic for pan-Protestant schooling to continue, his writing was full of pessimism and awareness that church leaders (including Methodists) were open to sub-division. Feild argued that the wording of the 1843 act made the Church of England eligible for a separate grant.27

11 In 1874, the Conservative Party led by Frederick Carter, who had personally shown hesitancy on the issue in 1870, passed an amendment that sub-divided the Protestant grant. There had been heated public debate between politicians, education board members, and church leaders, but the agreement of clergy in St. John’s led to a general consensus – one that resulted in the creation of three systems (Anglican, Methodist, and Roman Catholic) to be overseen by denominational superintendents. These positions were created in 1876.28 The Protestant superintendents, George Milligan (Methodist) and William Pilot (Anglican), zealously undertook the task of setting up their new school systems and espoused hope for cooperation and the development of “beneficent rivalry.”29 The superintendents, along with the denominational college principals from St. Bonaventure’s, Bishop Feild Academy, and Prince of Wales Collegiate,30 became key influencers in educational matters and the legislature heeded their advice, passing amendments that gave them more control over board’s conduct and the ability to certify and grade teachers.31

12 Driving the debate over sub-division was an awareness by politicians and religious leaders of a need to reform schools and set colony-wide standards. This topic became the key subject of the superintendent’s reports going forward. A crucial issue was how to improve the quality of the education provided, which people hoped would inspire passion for educational excellence amongst both teachers and students. During the second half of the 19th century, limited industrialization in Newfoundland combined with the rise of an increasingly interconnected world brought new forms of knowledge and educational expectations to the colony. This led to denominations trying to improve their educational services by seeking advice and personnel from the old world who were more highly educated, especially in new scientific subjects and pedagogical theories. In 1876, for instance, Bishop Michael Power invited the Irish Christian Brothers to set up schools in the diocese.32 The Brothers were well known for their role in educating Catholic boys in Ireland.33 They successfully established themselves as respected educationalists in St. John’s and gained recognition from the Catholic and wider St. John’s community.34

13 Historians’ understanding of denominational education in Newfoundland is dominated by McCann’s idea that the system was shaped by a weak and uninterested government and manipulative, selfish churches. But this perspective, while fairly assessing the government’s neglect, fails to consider how and why churches shaped education and their motivations. McCann did not examine church sources in his studies of Newfoundland education history, but instead focused on economic questions while considering some government and newspaper sources. And discussion of the system in larger works is often reductive and fails to fully evaluate the colony’s embrace of denominational pluralism, which accepted religious leader’s voices in the public sphere and meant that consulting denominationally tied educationalists from all churches was viewed as important for social harmony.35 Furthermore, while denominationalists wanted to retain their right to denominational schools they also faced financial and logistical challenges. In 1891 Newfoundland and Labrador had a population of 202,040 souls scattered over 6,000 miles of coastline in 1,186 localities, the majority of which were settled by one denomination or were predominantly one denomination.36

14 The story of the essay contest, which has not previously been examined by historians, challenges the narrative of churches as undermining Newfoundland through showing Catholic educationalists as eager participants in education reform, which they saw as a nationalist project that should involve all the colony’s churches. Ensuring education reform was led by churches was important for Brother Slattery because as a Christian Brother he was dedicated to protecting the right to separate Catholic schools. The right to a Catholic system was tied to the continued existence of the other denominational systems due to the wording of the 1843 act and the 1874 amendment. This approach respected denominational pluralism and enabled Catholics to draw support from Anglicans, who also cherished their denominational rights. Grasping how churches understood their role in education and society is vital for understanding denominational education, its significance, why it developed, and how it became entrenched.

The government holds an essay contest

15 In 1890, the Whiteway government, which held significant nationalist ambitions to develop the economy,37 decided to hold an essay contest to hear proposals for education reform that could work in Newfoundland. The colony faced challenges in providing high quality and consistent education because of minimal oversite of schools and lack of shared standards in the many small, sparsely populated communities, which struggled to retain teachers or motivate them to improve their qualifications, and it had a unique denominational system that also had to be considered – though why an essay contest as a means of gathering opinions was chosen is unclear.38 Entrants were required to address six subjects: first, they were asked to offer general opinions on the overall system; second, to make recommendations regarding administrative issues – especially the current method of school inspection; third, to discuss taxation and how schools should be funded; fourth, to examine if compulsory attendance was a reasonable and or a feasible option for the colony; fifth, to recommend a means of improving the material and intellectual situation of teachers; and, finally, they were invited to comment on any other pressing issues. James Murry, a recently elected Independent Member of the House of Assembly for Burgeo-LaPoile, was the chair of the Select Committee on Education and author of the call for essays.39 The call stipulated that the essays be submitted without names so that the committee could adjudicate them without being accused of bias, but also with information that could subsequently be used to identify the writer after they selected a winner.40

16 The adjudication committee was denominationally balanced, with one Roman Catholic (Brother R.M. Fleming), one Methodist (Professor Robert E. Holloway), and one Anglican (Sir Robert Pinsent, DLC). The supposed anonymity of the essays, however, was a farce. First, Slattery’s correspondence with Brother Maxwell in Ireland reveals that his essay was discussed amongst the Brothers.41 Second, Brother Fleming, who sat on the adjudication committee, related to Brother Maxwell in a letter written in March of 1891 that he had lobbied heartily for Slattery’s paper. Fleming stated he knew that it was Slattery’s and that he even admitted such to his fellow committee members. He wrote that he was adamant that, out of the selected top four papers, Slattery’s should receive first place.42

17 The committee stated that they had forty-one submissions. There were nineteen from the Anglicans, nine from Catholics, nine from Methodists and three from Presbyterians, and one ineligible contribution from a former teacher who had moved to Donegal, Ireland. While most essays came from men, three were from women. There was a mix of professions with eight clergy, two physicians, and twenty-nine teachers. The essays ran the gamut: sixteen called for the abolishment of denominational education, fourteen argued explicitly in its favor, and eleven did not mention the issue at all.43 Reportedly, because of the high quality of the essays, the committee chose to place four essays instead of three. The first received fifty pounds, the second thirty pounds, and third and fourth twenty pounds. The four essays that placed were as follows: 1st – Brother John Luke Slattery, St. John’s (Roman Catholic); 2nd – Rev. H. Lewis, Brigus (Anglican); 3rd – Father M.F. Howley, Bay St. George (Roman Catholic); and 4th – Dr. J. Sinclair Tait, St. John’s (Methodist), who was an elected Liberal Party MHA for Burin.44 Sadly, while the winning essays were reportedly printed and seem to have been circulated, only Slattery’s essay has been found.

18 Brother Slattery’s win was a bit dubious because of Fleming’s conduct, though the two other members of adjudication committee seemed to have agreed with Fleming about the merits of Slattery’s paper.45 Further, Brother Slattery’s winning contribution was almost never to be because Bishop Power’s reticence to be involved with the current government led to confusion over if Catholics should participate.46 Correspondence between Slattery and Brothers in Ireland shows a deep concern over indecision regarding the contest by members of the Catholic hierarchy, especially Bishop Power, and worry that a Methodist essay would likely argue for secularization.47 In a celebratory letter relating the competition results, Slattery noted that Bishop Power was much relieved at his decision to enter. He wrote that Power had told him that his essay was “‘A great triumph for the Church and for us all,’ he said. ‘Only for you,’ he added ‘we should have the Wesleyans directing our Educational System’.”48 Slattery felt the need to defend the Catholic viewpoint, which meant directly addressing denominationalism and arguing for denominational pluralism in educational governance.

Slattery’s essay: Innovation within a denominational paradigm

19 According to Slattery, “The Main object of this paper is to show how the present denominational system may be retained, yet so improved as to give results satisfactory to the people and to the Government.”49 He argued that denominationalism had produced a good system and a positive spirit within in the colony and made wary references to discord over educational matters in other places. He wrote: “Any material change in this matter will disarrange the present machinery, create distrust, and perhaps stir up religious discord. If we look to some of the neighbouring provinces, notably Manitoba and Ontario, not to mention the United States and some of the countries of the Old World, frightful risk will be seen of having an educational system out of harmony with the feelings of any considerable section of the population.”50 Critical to understanding this argument as the foundation of Slattery’s essay is his identity as an Irish Christian Brother. The Irish Christian Brothers were founded in 1802 by Edmund Rice. While there is debate relating to Edmund Rice’s desire to develop a relationship with the National School Board in Ireland, which was largely Protestant and state controlled, the Brothers’ schools remained independent. Over time, the Christian Brothers’ schools dominated the education of Catholic boys in Ireland. The schools had overtones of Irish nationalism as the Brothers sought to inculcate a sense of identity based on Catholic religiosity and Irish cultural practices and heritage.51 Slattery’s views on denominationalism were formed in the Irish context of the fight for Catholic institutions and rights.52 He pointed to the tumultuous debates about the right to have Catholic school systems in the Canadian provinces as arguments in favour of denominationalism. These debates were highly fractious. In Manitoba, debates became so heated that Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier was required to intervene to settle the issue in 1896, which resulted in the loss of Catholic schools.53 Slattery saw that throughout the Atlantic world Catholic schools were in jeopardy. Slattery invoked Newfoundland’s long history of denominational education, which he claimed had created strong communities and led to an embrace of denominational pluralism, as opposed to sectarian tension (indeed there was little to no violence between groups), as supporting evidence for retaining the denominational model.54 Slattery’s essay espoused a view of Newfoundland that saw religious identity as important and valuable to communities and the colony as a whole. This view was also one shared by much of the Newfoundland Catholic community. According to Fitzgerald, Lambert, and Manion, clergy and laymen worked to build a strong and influential Catholic community that was engaged and accepted as an important partner in the political project of shaping Newfoundland government and society.55

20 Underpinning Slattery’s argument for denominationalism was his view of how communities should work. He felt that cooperation between the churches and the government was the best way to engage citizens in the provision of education. He was opposed to creating education as another government service. In support of this point he wrote:

Looking through the Island, the educational establishments, not erected on the denominational principle, are conspicuous by their absence. Uproot this principle and private efforts are at an end. This is the one green spot in the great desert of dependence on government suppling every want, public and private. I regret to say it, but the fact cannot be denied, that the people look to each successive Government, more and more, for those things they should procure for themselves.56

21 Slattery was sceptical about the role of government in directly shaping people’s lives, which he saw as a more proper sphere of influence for the church. This point of view differed greatly from the school promoters like Egerton Ryerson in Canada, who embraced the government’s foray into shaping people’s lives through schools.57 Local people, through participating in the church, according to Slattery would be able to shape their communities, though there was the implicit expectation that they would be properly deferential to the church. Critical to understanding this view is his thinking about apathy and personal responsibility. One of the Select Committee’s central requests was for advice on how to encourage attachment to education in the colony.58 Slattery felt that for education to be embraced it must involve people at the community level. Crucially, he argued against implementing a tax system to pay for education because he thought a school tax would make education a government service, writing “The people have long been so trained to look to the Government for everything that a great prejudice would be created against any Educational system resting on the basis of direct taxation.” However, he did admit that it might be possible to levy enough revenue for education from an income tax that would not harm the poor. He noted, though, that it would be important for the government to enter into a partnership with local communities to ensure some direct local financial contribution in a sort of matching scheme for that approach to work.59 No tax for education was ever implemented in Newfoundland during colonial independence.

22 Slattery’s beliefs about stimulating attachment to education through personal financial responsibility can be understood as his way of ensuring people were participants in education through their respective denominational schools. Slattery also argued against compulsory attendance by making similar points about a need to inculcate a love of education and not alienate people from education and from local authorities who might have to enforce attendance. He also noted that enforcing such a law, given the geographic challenges in the outports where it was most needed, was unfeasible, and he was focused on motivating students to attend. To inspire parents to send children, he recommended creating a reward system of book and monetary prizes for attendance.60 For Slattery, the flaws in education in Newfoundland could be attributed to the “apathy of the people, and in the circumstances of the Island.”61 His ideas for improvement were grounded in invigorating the system so as to encourage a spirit of enthusiasm for education, which would also reinforce participation in the churches.

23 The most notable element of the essay was its strategy for encouraging higher education, which would improve the quality of teachers and create opportunities for students. Slattery recommended that

a Central Council of Education representing proportionately each denomination, could do much in the interest of Education. But on no account, should it be connected with the Government. Should it be connected, politics would guide imperceptibly and party spirit rule in a matter that should be above party and beyond the heat of politics.

The Members of this Department might be named by the heads of the different denominations and approved by the Governor in Council.62

24 Slattery’s insistence that the council not be government controlled was fundamental to his sense of an ideal church-state relationship. His partnership vision limited power for the government while also balancing it amongst the different denominations, which reflected an acceptance of Newfoundland’s other churches. This council would regulate exams and standards for grades of teachers and for students who sought admittance to post-secondary institutions abroad. The council would be balanced between the denominations based on population, with the current three superintendents given the ability to make important decisions relating to the exams. Slattery also proposed the exams be sealed and students assigned a number to avoid any denominational favouritism in the grading and corresponding prizes and scholarships. This council was to be an interdenominational body that effectively responded to the challenges of modernity. The two main challenges were enabling the teaching of new scientific subjects connected to new jobs and meeting contemporary common educational standards.63

25 Slattery’s essay also spent considerable time addressing how to improve the rates of teachers’ salaries and how to create interdenominational schools in small towns. Underpinning Slattery’s suggestions was a vision of a cooperative denominational model that restricted the role of the state and eliminated the potential for democratic – read secular – control of education. In relation to teachers, Slattery proposed a scheme to raise wages based on certificates, which would be graded and administered by the council discussed above. Slattery argued for three revenue streams to make up the total of teacher’s salaries. The streams would be based on their attained grade, local board pay, and bonuses resulting from inspection. The proposed central board/council would control the grade, and thus two of the revenue streams (grade and bonus), resulting in a centralizing effect. According to Slattery, control of a teacher’s grade would give the council control over the bonus because it was to be based on the grade as well as inspector reports of improvement of qualifications and quality of teaching. However, this proposal still had a position for the local board to have influence through their control over a part of their teachers’ salaries. Slattery viewed the denominational colleges in St. John’s as fulfilling the function of normal schools, though they were not technically normal schools. In cooperation with the council, the colleges would develop and implement a new shared curriculum for training teachers.64 His suggestion regarding inspection also spoke to his vision of cooperation amongst the denominations. “Each Inspector would take a district in rotation,” wrote Slattery. “In this way, the work could be efficiently done, and no denomination run the risk of unfair treatment.”65 In addressing the issue of how to create amalgamated schools, Slattery argued that when there were less than 20 children of one denomination in a community then an amalgamated school should be allowed.66 He wrote that these schools should be controlled by a central board, connected to the superintendents and the council, that would handle exams for students and teachers. His view was not a democratic one. The churches were clearly meant to hold most of the power, with citizens and local communities exercising influence over education through participating in their respective churches. Churches already controlled their education systems, which were run by the denominational superintendents. Slattery argued that staffing the CHE with church-appointed representatives was good because it would further collaboration and entrench control and influence. Slattery placed the onus and control of education in the hands of the churches, whom he envisioned would work together for the betterment of the colony.

26 Slattery’s essay suggested innovations grounded within a conservative denominational paradigm. It was conservative in that it shored up traditional ideas of churches as institutions with a right to mould society; but it was as well an innovative adaptive call for denominational collaboration that acknowledged of Newfoundland’s denominational pluralism. Churches, as demonstrated by Peter Berger and others, rejected being pushed out of the public sphere and their traditional areas of influence and they strove to resist the advance of secularism, which had led states to claim broad powers and influence over citizens and society.67 Slattery’s victory in the essay contest was celebrated with enthusiasm in the Catholic community. In the following legislative session Slattery was asked to speak before the legislature and noted in his correspondence with Brother Superior Maxwell that Bishop Power referred to the upcoming Act to Consolidate and Amend the Acts for the Encouragement of Education as “his bill.”68

27 The Select Committee on Education asserted that the selection process was completely anonymous and the denominationally balanced committee impartial, but that was a significant overstatement.69 The praise of Slattery’s essay, which was not discussed as a Catholic essay in the report, was remarkably high. In fact, the Select Committee on Education wrote in their report that much of Slattery’s essay was so valuable as to there being no need for further debate about how to improve teachers’ salaries and stimulate enthusiasm for education in the colony.70 Slattery’s victory in the essay contest was cheered by many sides because his essay offered insightful ideas for improving education in Newfoundland. His suggestions regarding teachers’ salaries were included in the 1892 education act.71 However, a straightforward implementation of his vision for a council to implement higher education grounded within a conservative cooperative denominationalist paradigm was to go through a contentious two-year process.

Democracy and denominationalism: Establishing the Council for Higher Education

28 In their report concerning the essay contest, the Select Committee on Education made numerous recommendations based on Brother Slattery’s essay and ideas from other submissions.72 The report listed eleven resolutions to be made into legislation – resolutions that would alter, improve, and dismantle parts of the then-current education act.73 In these resolutions, the descriptions for new bodies for regulating education were similar to the ones espoused by Slattery but there were important differences. The committee saw more room for government involvement, and in their first resolution they suggested the creation of a permanent educational committee that would be staffed by government officials. Going forward, the committee said there should be no alteration of the denominational system. Concerningly for denominationalists, they suggested that the government committee work closely with the superintendents. The committee wanted the government to have more control over decisions and money. In resolution six, they described a new central board of education made up of the education committee and the superintendents.74 This body would be responsible for the exams, prizes, and setting new standards. Essentially, it would become the council that Slattery had envisioned. This was a more democratic approach that allowed voters to influence decisions by electing MHAs who would sit on the council. Further, it would have created a church-state partnership wherein the government had significant influence and more financial control.75 For example, in resolution eight, they tried to give the government more control over the denominational superintendents. This resolution suggested that new superintendents be chosen from the teaching profession and subjected to government examinations as opposed to being nominated by church leaders and confirmed by the governor.76 While the committee’s report stated that they were largely in agreement with Slattery’s essay, their vision was not in line with his essay in terms of the balance of power between church and state as reflected in English Canadian norms.

29 The committee’s report was published in the Evening Telegram on 4 March 1891.77 The contentious issue, according to James Murry, the Independent MHA for Burgeo-LaPoile, was the degree of church control over the system. Several members of the committee placed asterisks next to their names to indicate that they had reservations about the report, but the notes accompanying the asterisks did not describe their reservations.78 Murry wanted to restructure public education in Newfoundland to more closely imitate Nova Scotia’s school system, which he argued inspired loyalty on the part of teachers due to its unified character.79 He was, however, a first-time MHA and an independent with limited authority and support from Whiteway’s Liberal government, and the process resulted in accusations that he wanted to head the new committee and had overstepped his role by proposing the Select Committee on Education Report become legislation.80 In place of the committee’s resolutions, a short education bill was proposed by Murry. At the same time, a separate bill, reportedly very similar, was also proposed by Dr. Tait, who wrote the fourth-place essay.81 Slattery’s correspondence reveals that Catholics and others greatly opposed these bills, and he lamented them as poor efforts to encourage education. The Church of England Synod and Methodists were opposed because the superintendents’ powers might be limited, and the make-up of the respective council did not reflect the colony’s demography.82

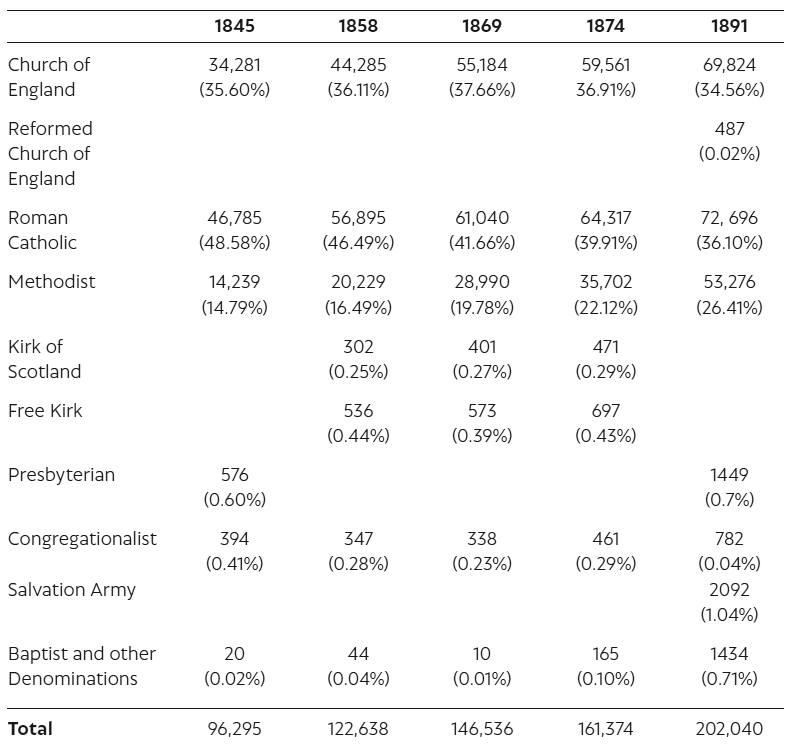

30 The opposition from the Anglicans was especially significant because they agreed with Catholics on the importance of the denominational principle. Further, as shown in Table One, Anglicans and Catholics made up a significant proportion of the population. In 1891, Catholics and Anglicans combined to account for 70.68 per cent of the population.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1

31 This was deeply significant because support for church leadership having a role in politics was a norm in Newfoundland. In fact, it was an agreement in Newfoundland politics following the 1860s that appointments would respect denominational proportions. Methodists in the colony had a long history of different views on education and church-state relations, and though in Newfoundland there was more comfort with a church-state relationship on the part of the hierarchy in St. John’s many were reluctant in their embrace of denominationalism in education. But, unlike in Ontario, where Methodists and dissenting Protestants were a significant majority and shaped the development of a public system disconnected from churches, Newfoundland Methodists were a minority.83 Further, other dissenting Protestants, who were influential in education debates in English Canada, accounted for less than two per cent of the population.84 This meant that dissenting Protestants had limited influence on educational policy.

32 Dr. Tait, a Methodist educated in Nova Scotia, vigorously advocated for his bill and commented that the government should recombine the Protestant denominations.85 MHAs debated the merits of Tait’s and Murry’s councils, and found them unworkable due to lack of coordination with churches and superintendents.86 MHAs also dismissed the idea of multi-denominational schools for fear they might be unworkable, which is curious given Slattery’s and the Anglican Synod’s support for these schools in limited circumstances.87 Despite efforts by MHAs to pass an act, there was no reconciling the two bills. Dr. Tait’s bill was withdrawn and, while a version of Murry’s went forward, it failed to pass. One year later an 1892 act was passed that included the recommendations relating to teachers from the Select Committee’s report; but higher education was not mentioned and was left to the denominational colleges.88

33 On 8 July 1892 St. John’s burned to the ground. That fall brought with it the challenges of rebuilding and saw a resurgence in debates and conversations about building up educational services in the colony. Slattery’s correspondence reveals that the issue was not dead. In fact, frequent conversations were happening amongst denominational leaders over the state of higher education. Slattery wrote on 3 May 1893 that he had been conversing with the head teacher of the Protestant Academy (it is likely he meant the Church of England’s Bishop Feild Academy) about the state of higher education and what might be done. He wrote that he “regretted the apathy that hung over education matters, having no competition, no life, no soul in any department.”89 Following that conversation, the Anglican man (likely Bishop Feild Academy’s principal William Blackall) then brought to a meeting the head of the Methodist Academy, and the three subsequently went to the three denominational superintendents with their suggestions. The group then went together to the government and presented their case to the legislature, which responded positively. On 24 May 1893, the government passed An Act to Provide for Higher Education.90

34 The Council for Higher Education (CHE) was formed along the lines that Slattery’s essay had envisioned. The debates surrounding the resolution in the legislature resurrected the issue of denominational control, but this time concerns about the council’s denominational character were not the main point discussed. The main debate focused on if it might be appropriate to spend $4,000 on higher education when there were many settlements in the colony that still lacked schools. MHAs Tait and Morine combined these arguments with statements that extolled the good of Nova Scotia’s school system to argue against the new bill and the creation of the church-controlled CHE.91 Other MHAs expressed concern that the council might favor the wealthy children and those who attended the top schools in St. John’s, which would result in limited social mobility. When the vote came, only three opposed the resolution: Dr. Tait, Murry, and Morine.92

35 The new CHE consisted of 22 members appointed by the Governor in Council. The three denominational superintendents and heads of the three denominational colleges were to be ex officio members. The remaining 16 members, divided between the churches based on population, were to be nominated by their denomination’s leadership.93 The role of the CHE was to draw up a syllabus for new certificates, which would be the standard across the denominational systems. The exams, written by British educationalists, were in line with British standards for the University of London and enabled students to access universities and colleges. Its structure and mandate gave leading educationalists in St. John’s new influence over outport schools and teachers.

36 Slattery was one of the original members of the CHE. His correspondence shows some of the early inner workings of the body, which reflected denominational blocks pushing their own standards. Slattery’s writing, however, is light in tone, and he portrayed the atmosphere as highly collaborative.94 The design of the CHE enshrined denominational representation in educational administration – an idea encoded into the very first education act of 1836. The Hon. Surveyor General Henry J.B. Woods commented in the passing of the legislation that “as he understood it the main principle underlying the resolutions was the germ of a university based on the broadest principles without regard to denominational difference.”95 This highly positive view of the cooperative ethos of the council was in sharp contrast to the statements of men like Murry, who saw enshrining denominationalism as furthering sectarian division. Slattery certainly saw it as protecting denominationalism and respecting denominational pluralism. Many focused on the idea that the creation of the CHE was an indication of the potential for cooperation going forward; it may have also foreshadowed the creation of Memorial University College in 1925, which was established through the collaborative efforts of the denominational superintendents.96

37 The creation of the CHE was cheered and celebrated. Anglican synod records and conference reports from the Methodist church lauded the council’s potential for improving education and welcomed a healthy enthusiasm for competition.97 While they cheered the creation of the CHE’s potential for improving education broadly, the Brothers also embraced the rivalry between the denominations and were ecstatic about their boys and other Catholic students’ achievements over those of other denominations because it showed Catholic educational excellence.98 The 1893 reports of the Methodist and Anglican superintendents expressed optimism for the newly created CHE, which they, along with Catholics leaders, envisioned as initiating a new cooperative era – although Milligan did worry about denominationalism in his report.99 While the body, however, was criticized at times for the low numbers of students who took its highest level exams in the early 20th century and that it made teachers too focused on exams and the students likely to take them, its real significance lay in its inauguration of a cooperative denominational model of education governance – a model that was held up as a social good. The CHE endured until shortly after Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, and the church-state partnership in education until 1997.100

Slattery’s sectarian solution to Newfoundland’s educational challenges

38 After the first CHE exams in 1894, Slattery wrote concerning the results: “I may be wrong, but I am much deceived if a great victory has not been won for the cause of Religious Education.” 101 The establishment of the CHE was celebrated by the government and churches as a step forward. Some MHAs worried about the entrenchment of denominationalism, and some of the Methodists and politicians who had lobbied for a secular system or at least reforms that would have increased government control protested the move, but these people’s concerns were not influential. Denominationalists were able to influence the more powerful politicians, and there was public acceptance of the importance of church ties to schools. While sectarianism is often defined as violent and volatile, the success of cooperation between denominations points to the need to reconsider the history of denominational education and sectarianism in Newfoundland and Labrador. The depiction of the system as a sectarian mess is misleading and obscures the history of churches’ understanding of their social role and their relationships with the colonial state and struggle to improve the system with limited financial means and in the face of immense logistical challenges. Slattery’s essay is significant because it led to the creation of a formal body that facilitated denominational cooperation tying all the churches together through respecting Newfoundland’s denominational pluralism, which also helped enshrine in law that the churches were the state’s partners in education while also embedding in public discourse that the churches were important partners in building up Newfoundland and not undermining it.

39 Slattery wanted, as his essay stated, “to show how the present denominational system may be retained, yet so improved as to give results satisfactory to the people and to the Government.”102 He achieved his goal. The creation of the CHE, led by the denominational superintendents and college principals, resulted in church-tied educationalists being given authority over the colony’s efforts to improve and modernize education. The denominational paradigm began its formation in 1836, when clergy were included as denominational voices on boards, but it was fully established and transformed into a cooperative denominationalism through the creation of the CHE with the 1893 act, which brought together all the colony’s denominations in a shared body. This conservative cooperative denominationalist paradigm, which espoused the idea that churches should influence society and social institutions, would be enshrined again and again in Newfoundland when major reform was discussed, such as in 1920 when the government sought to create an official Department of Education during the era of Commission of Government (1934-1949) and during the negotiation of the Terms of Confederation after 1949.