Articles

“Let's drop in on our friends at Sunnybrae”:

CBC Radio's The Gillans, Agricultural Reform, and Rural Change in the Maritimes, 1942–1972

David L. Bent works as a contract academic instructor and freelance researcher at the University of New Brunswick, and his current research focuses on agricultural modernization and rural change in the Maritime Provinces. He is the author of Determined to Prosper: Sussex & Studholm Agricultural Society #21, 1841 to 2011: The Story of the Sussex Co-op, the Oldest Agricultural Society in the World, and he is currently reworking his dissertation into a book for McGill-Queens’ University Press’s “Rural, Wildland, and Resource Studies” series.

Résumé

La série The Gillans, diffusée pendant longtemps (1942-1972) à la radio de CBC, fut conçue comme un moyen populaire d’encourager les fermiers des Maritimes à rendre leurs exploitations plus efficaces, plus scientifiques et davantage axées sur le marché. On espérait que l’émission puisse ainsi contribuer à stimuler les économies agricoles en difficulté des provinces maritimes et leurs sociétés agricoles rurales. L’analyse du contenu et des messages des documents relatifs au programme donne un aperçu du processus de modernisation agricole en cours dans les Maritimes au milieu du 20e siècle, et de la façon dont les fermiers s’adaptèrent aux effets de la modernisation sur l’agriculture et le mode de vie rural en général.

Abstract

CBC radio’s long-running serial The Gillans (1942–1972) was conceived as a popular means to encourage Maritime farmers to make their operations more efficient, scientific, and market-oriented. In doing so, it was hoped the show could help bolster the Maritime provinces’ struggling farm economies and their winnowing rural societies. Examining the content and messages of program’s scripts offers insights into the process of agricultural modernization that was underway in the Maritimes during the mid-20th century, and also into how farmers coped with the impact modernization had on agriculture and on rural life in general.

1 Noon was more than just a mealtime for many mid-20th-century farm families in the Maritime Provinces. As the family gathered at the dinner table, the radio was often tuned to the CBC for the Farm Broadcast. This Halifax-produced, half-hour long, weekday, noon hour program featured the news and weather as well as several segments specially geared to farmers’ concerns, such as produce prices, market information, and agriculturally themed commentary and interviews. For most listeners, however, the highlight of program came when the announcer intoned “Let’s drop in on our friends at Sunnybrae,” signaling the start of an 8-10 minute segment called The Gillans.1 Running from 1942 to 1972, The Gillans was, by far, the most popular part of the Farm Broadcast. The series chronicled the adventures of a fictional Maritime farm family, the Gillans of Sunnybrae Farm, and their neighbours and friends, in the fictional rural community of Littlevale.2 Listeners were drawn to The Gillans for its charming and relatable characters, down home humour, gentle melodrama, and sympathetic portrait of farm life.

2 The Gillans was not, however, produced solely for entertainment. Carefully interwoven into each episode’s narrative were tips aimed to help farmers modernize their farms, improve their efficiency, and increase their returns. This educational directive, in fact, was the main impetus for the creation and production of the show. The Gillans was conceived as a popular medium to educate Maritime farmers on modern agricultural techniques and help shore up the regional farm economy and rural society, both of which were under considerable stress by mid-century. This agenda places The Gillans within the context of a great agricultural modernization movement that aimed to make the regional farm sector more productive, more efficient, more scientific, more market-oriented, and thus more economically sound. Scripting The Gillans from mid-1949 until the end of its run was Jean Pell, a housewife from Hebron, Yarmouth County, with a knack for storytelling. Pell’s talents brought the denizens of Littlevale to vivid life for her listeners, and made the show entertaining, informative, and, consequently, long-lasting. Working in tandem with her producers as well as extension workers from the Nova Scotia Agricultural College (NSAC) at Truro and the provincial Department of Agriculture in Halifax, Pell subtly incorporated educational tips and information into her stories to help her listeners improve their farming methods, output, and quality of life in their communities.

3 There are many consistencies in the scripts from one year to another, such as the commitment to agricultural improvement. But over the course of its run one can discern a decline in the show’s confidence of what the future held for farming. During the 1940s and 1950s, farming was presented as a vocation with a bright future. Though not without its challenges, any problems besetting farming could be overcome through better techniques, good business sense, and old-fashioned hard work. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, in the face of ongoing rural outmigration and a financial pinch on remaining farms, it had a decidedly more pessimistic tone about farming’s future. Examining The Gillans thus represents more than a stroll down memory lane. The program was an important cog in the campaign to modernize Maritime farming, easily its most popular manifestation, and its scripts reveal much about the agenda, ideology, and hopes of the advocates of farm modernization. It also illuminates the consequences of this transformation, as by its last years its characters were grappling with the economic, social, and ecological dislocation caused by agricultural modernization. Despite the world changing around it, though, the series was consistent in its positive portrayal of farmers. In contrast to the standard popular culture depictions of rural folk as dumb, backwards, unsophisticated hicks, on The Gillans farmers were intelligent and progressive and farming was a craft worthy of respect. This doubtless helped it retain a loyal audience for 30 years, as it offered Maritime farmers a kindly voice of solidarity, education, and entertainment during very challenging times.

4 The Gillans cannot be properly understood without understanding the environment of agricultural modernization that birthed it. The late-19th to mid-20th centuries was a time of energetic and sweeping rural reform efforts in Canada due to a persistent farm crisis brought on by industrialization and urbanization. The burgeoning industrial towns and cities represented a bountiful market, and many farmers expanded their operation, both in size and output, to meet the demand. In the Maritimes this was evidenced by the tremendous growth in the dairy sector that catered to the local demand for milk and butter, and the success of the apple export market to Great Britain.3 This change was not without cost, as only farms large and profitable enough to afford the expensive machinery and chemicals needed to remain competitive could stay afloat. As a result farm numbers began to decline, and many of the more successful farms absorbed abandoned farms and thus added to their operations’ output.4 Furthermore, young people were increasingly finding farm life – characterized by long hours, hard labour, and often-meager financial reward – unappealing, and were increasingly seeking their fortunes in urban areas. By the 1920s Canadian urbanites surpassed rural dwellers demographically, although more workers were still employed in rural primary sectors than in the urban blue- and white-collar sectors. By the 1940s even this was no longer the case, and in the decades that followed Canada became an overwhelmingly urban country.5

5 This situation alarmed many observers, who viewed agriculture as the foundation upon which all other economic prosperity was based. As it was feared that a diminished farm sector would weaken the overall economy, an aggressive reform movement emerged in the late 19th century to bolster the agricultural sector. Agrarian reformers aimed to adapt agriculture to the modern age by bringing it in line with the ethos of industrial capitalism, making it more mechanized, efficient, productive, and market-oriented.6 Provincial governments were among the key players in this movement, funding agricultural colleges, beginning with the Ontario Agricultural College (OAC) at Guelph in 1874, as well as extension services to instruct farmers in modern agricultural practices. In the Maritimes, this effort was exemplified by the founding of the provincially sponsored NSAC in 1905, the creation of provincial agricultural extension services during the 1920s, and the encouragement of the co-operative marketing of strictly graded produce during the 1930s.7 The onset of the Depression added an air of greater urgency to farm improvement, and reformers were desperate to spread their message to a broader audience so as to stave off greater economic calamity.

6 Fortunately for them, there was a popular medium that allowed them to reach more Canadians than ever before: radio. The 1930s saw the formation of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), a national radio broadcaster expected to entertain and educate Canadians. In its early years, adult educators flocked to the CBC to produce educational programs for Canadians of all walks of life and farmers were no exception. Farm folk were avid radio listeners. By the mid-1930s as much as one-third of all radios owned in Canada were found on farms, providing entertainment and a means to escape the isolation of farm life.8 In 1939 the CBC formed a Radio Farm Broadcast Department, charged with producing farm-themed programs to both entertain farmers and keep them abreast on the latest developments in their industry. The first head of the department was Orville Shugg, and the flagship of his department’s programing was the lecture- and debate-themed Farm Radio Forum. Airing on Monday evenings during winter from 1941 to 1965, the forum provided a venue for farmers to discuss and find solutions to the challenges facing their industry. Agricultural reform activists across the country encouraged farmers to form local listening “forums” to discuss the issues raised on the program, and apply what they learned to their operations. The Farm Radio Forum proved a phenomenal success. At its peak in the late 1940s it boasted over 1,600 registered forums, with an estimated membership of over 21,000.9

7 Despite the forum’s success, many in the Farm Broadcast Department, including Shugg, felt that its formal and educational format might intimidate or put off some listeners. As such, they became convinced that a “common touch” was needed to ensure that CBC’s farm programs connected with as many listeners as possible. In 1940 Shugg, drawing on an unpublished novel he had written several years earlier, devised what he called the Farm Family Dramas. These were conceived of as short programs placed within the noon-hour farm broadcast presenting the entertaining adventures of a fictional farm family, all the while inserting educational topics of agricultural improvement and contemporary rural issues into their narrative. The first of these dramas, The Craigs, premiered in 1940, airing in Ontario and Anglo-Quebec. Its success, and the knowledge that agricultural issues would vary across the country, prompted Shugg’s department to subsequently create three additional Farm Family Forum programs: The Jacksons on the Prairies, The Carsons in British Columbia, and The Gillans in the Maritimes.10 The shows were instant hits, and farm families made listening to the adventures of their regional radio avatars a part of their noon-hour routine well into the 1960s.

8 The Gillans premiered on 12 January 1942, with a script by Norman Creighton, a resident of Hantsport, Hants County, who had worked as a freelance writer for the CBC for several years. While the impetus for the series came from top CBC brass, Creighton can be credited with the creation of The Gillans. He was seeking steady writing work, and, having contributed to several agricultural programs, was offered the chance to try writing scripts for the proposed Maritime Farm Family Drama. Being sent scripts of The Craigs for inspiration, he composed five preliminary scripts for approval from the CBC in Halifax. The CBC executives liked what they saw, and shortly thereafter Creighton was hired on as the chief writer for the show. Taking his cues from The Craigs, Creighton established the main character relation for The Gillans as a father-son dynamic wherein the son (a stand-in for the audience) asked questions about farming and learned from his father’s example, with a similar mother-daughter dynamic concerning domestic matters.11 Creighton wanted his characters to speak like real farmers; thus his dialogue incorporated the colourful expressions his friends and neighbours used, adding a layer of authenticity to his fictional world.12 During its early years The Gillans was scripted either by Creighton or by author Kay Hill, but both quit the show in 1949, finding the job of writing five scripts a week too taxing.13 Following their departure The Gillans got a new writer, Jean Pell.

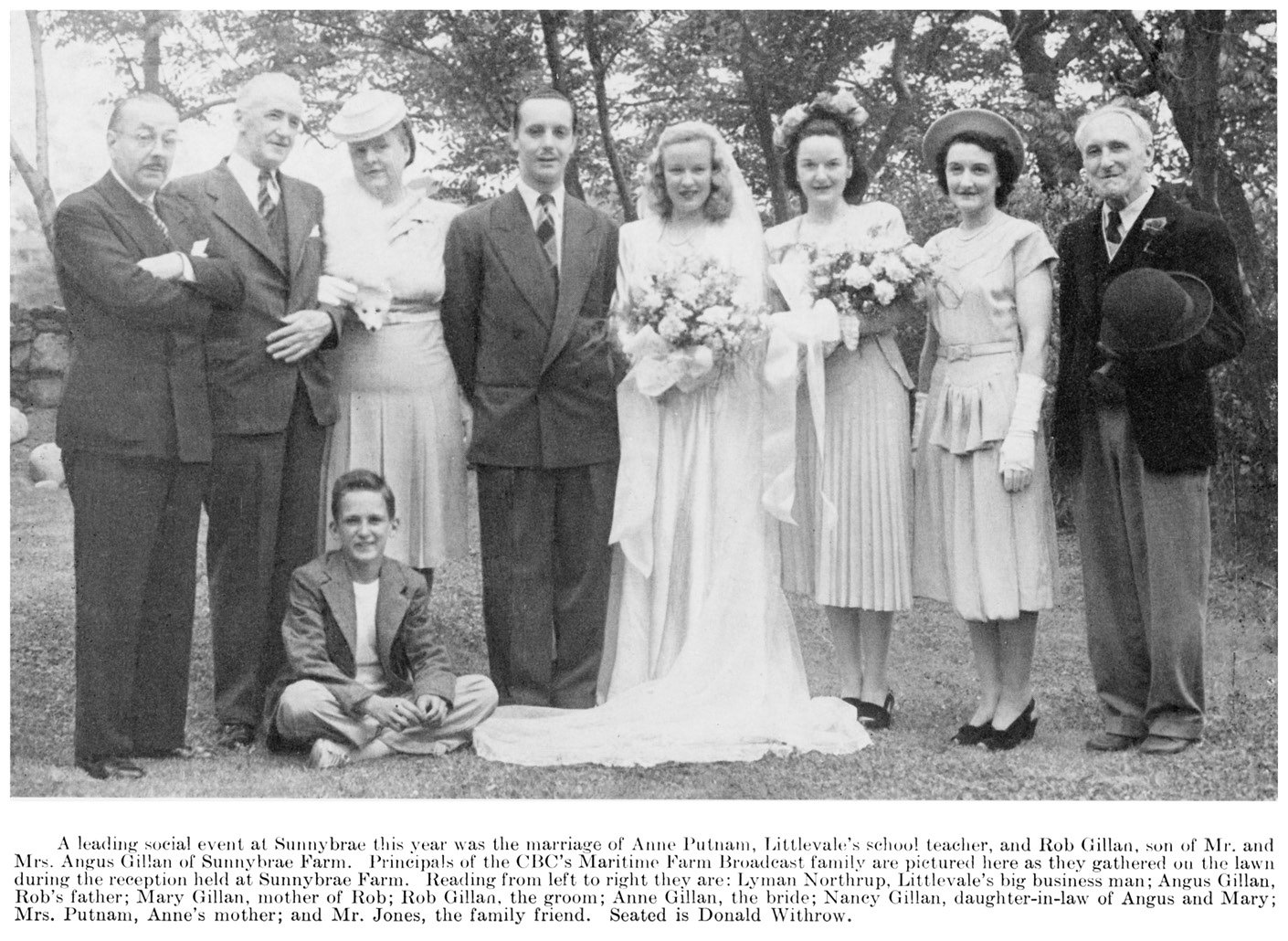

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 19 Bucking the typical Canadian migration trend, Pell was an Ontarian who moved east and found a career. Pell was born in St. Catharines to Reginald and Ella Mason in 1915, but her family had Maritime links, as all of her grandparents were from Nova Scotia. Her father was a construction engineer who worked in cities across Ontario and the bordering American states, so she grew up in a predominately urban environment, but her family did have rural connections. Jean’s maternal uncle, Willard Longley, originally hailed from a farm near Paradise, Annapolis County, and had made agricultural science his career. Studying at the NSAC, the OAC, and the University of Minnesota, by the 1920s Longley had become a leading agricultural scientist. In 1927 he returned to the NSAC to serve as both a professor of agricultural economics and head the recently created provincial Agricultural Extension Service. Once established in Truro, Longley and his wife, Clio, who regretted that they had no children of their own, invited their teenage niece Jean to come live with them.

10 Pell graduated from the Truro Academy in 1930 as valedictorian, winning the Governor General’s Medal for excellence. After finishing a secretarial course at Success Business College, she found a job at the C.E. Bentley department store in Truro and was soon writing the store’s adverts. Sensing that she had a talent for this sort of work, in the early 1930s she moved to Montreal to work for the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency – one of the largest ad firms in the world. Pell’s talent was quickly recognized by the management, and she was appointed an account executive for major accounts such as Kraft Foods and Buckley’s Cough Syrup. For the Buckley’s account, foreshadowing her later career, she also wrote promotional short stories and radio scripts. Yet despite her talents, as a woman she was expected to give up her career once married. Thus, in 1946, following her marriage to Major William Pell, Jean dutifully left her job. Following William’s discharge from the armed forces the Pells settled down in Hebron, Nova Scotia, eventually having two children; but Jean Pell’s life as a small-town housewife was soon upended.14

11 In mid-1949 The Gillans was without a writer, prompting a search for someone to fill the position. According to Pell, one day, out of the blue, she received a call from a CBC radio producer asking her if she would be interested in taking over as writer for the program.15 Why the producers approached her is unclear, but it is likely that her uncle, Dr. Longley, had some influence on the decision. As the director of the provincial Extension Service, he would have been keenly interested in the continuation of The Gillans, and, aware of his niece’s writing and advertising talents, probably thought of her as a natural choice to write the program. In any event, Pell accepted the offer, submitted some preliminary scripts for approval, and was shortly thereafter hired to be the sole writer for The Gillans.

12 Writing for The Gillans made for an extensive workload for Pell on top of her domestic and maternal duties. The show aired five days a week, requiring her to set aside a part of her daily routine to produce new scripts, with each averaged seven-to-eight pages. She was expected to mail in a week’s worth of scripts to Halifax every Friday, except during a month-long summer hiatus. Pell was also obliged to make monthly trips to Halifax to meet with CBC producers like Jack Johnson and Peter Hamilton, who had The Gillans among their many radio and television responsibilities, to discuss ideas for scripts and what farm issues to incorporate into the show.16 These issues were worked out between Pell and the producers at their meetings at least a month prior to airing.

13 Input into what was raised and discussed on The Gillans, though, was not limited to Pell and the producers. Professors from the NSAC and agents from the Department of Agriculture were always available for consultation, and, when The Gillans dealt with non-agricultural matters, input was sought after from figures such as lawyers, doctors, and the police. At times Johnson and Hamilton also sought out the opinions and advice of ordinary farmers regarding issues discussed on the program. Pell followed their lead in seeking inspiration from actual farm folk. As someone with no farm experience, she was keenly aware that she was at a disadvantage in writing on farm life. Consequently, during the show’s summer hiatus she often made paid trips to rural bed and breakfasts or boarded with farm families. These trips allowed Pell to absorb the rhythms of daily farm life, see how farmers worked, and get ideas for stories.17

14 Once Pell completed the scripts, the stage was set for the production at the CBC studios in Halifax. In its early days The Gillans was performed live during the Farm Broadcast, but in later years, to accommodate the cast’s varied schedules, a week’s worth of shows were recorded one evening a week. The show’s producers and crew went out of their way to bring Sunnybrae to life in the minds of listeners. To keep track of where things were situated, the producers drew a map of the property laying out where the buildings, roads, and mailboxes were, and who owned the adjoining properties.18 Sound effects were paramount to any radio production, allowing listeners to imagine the characters as real people living in an actual environment. Jack Johnson praised The Gillans’ engineers for their ability to create the auditory illusion of a farm by replicating “the sounds of the milking machine being put on the cow or taken off. The roosters would crow – sheep sounds – calves being fed – the screen door being shut – dishes being washed – glass being broken . . . . Yes the soundman was an important element to the reality of the show.”19

15 But no matter how well-informed were Pell and the producers, or how clever were their soundmen, The Gillans would not have lasted long without its engaging characters. Heading the clan was Angus Gillan (played by newspaper reporter James L. Robertson), a commonsensical patriarch with a slight Scottish accent and a fondness for quoting the poetry of Robert Burns. At Angus’s side was his wife Mary, played by Abbie Lane, a journalist and Halifax municipal politician in her regular job who served as an alderman and for a time deputy mayor.20 Angus and Mary had three children, named, from eldest to youngest, John, Jean, and Rob. The most prominent of their children was Rob, played by disc jockey and musician Baz Russell. While his brother married a local girl, Nancy, and took over his father in-law’s farm, and his sister married an employee of the federal Department of Agriculture and moved to Ottawa, Rob remained on Sunnybrae to help his father. Rob eventually started a family of his own, which included his school teacher wife Ann, played by Lohta Miller, and their four children – from eldest to youngest, Billy, Mary Ann, Rob Roy, and Chuckie – most of them being played, at least when they were very young, by Anna Geddes.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 216 Besides the Gillan family, the cast included many of their neighbours and friends. Among them was English immigrant Henry Jones, played by Leslie Pigot, who was trying his luck at poultry farming, but usually had a hard time due to his inexperience. By the show’s final years he had retired from farming to run a general store. Jones’s missteps were frequently used as cautionary tales for listeners, as were those of his son Lester, played by David Murray Jr., who worked for the Gillans as a hired man. Lester was presented as a sort of “clever idiot,” always concocting schemes to improve or ease his farm work without thinking them through – often with disastrous, but comical, results. Contrasting with the Joneses was Cyrus “Cy” Weatherbee, played by Bill Fulton, a migrant from Western Canada, who was presented as the embodiment of progressive farming, albeit a bit of a blustery one. Weatherbee was frequently trying new farm methods to secure greater profit and efficiency, and often succeeding thanks to his foresight and business sense. The contrast between the elder Jones’s struggles and Weatherbee’s success caused considerable tension between them. This was usually milked for comedy, with Jones being prickly and jealous and Weatherbee pompous and condescending. The cast was rounded out by other neighbours, hired help, and friends.

17 From the outset, every episode of The Gillans contained at least one reference to ideas or techniques farmers could use to modernize their operations. These could be discussions about entirely new methods of farming, or just simple tips on how to improve existing methods. However, the story and character interaction always took precedence over the educational elements of the program. This was a wise move, for had it been the other way around, and the program took the form of a lecture or sermon, the show likely would not have been as successful as it was. But this approach was not without its risks, as some of the educational material was so subtly inserted into the scripts that one could be forgiven for wondering if the original listeners even noticed it.21

18 For example, in the earliest of Pell’s Gillans script preserved, the only lesson in the story reminded farmers to put their hay mowing machines out of gear when they had stopped the horses. The episode opens on a hot summer day with Angus and Rob stopping for a rest from mowing hay. Rob supposed there was no need to ask if Angus had thrown the machine out of gear, but Angus replied that it was always a good idea to ask because “too many farmers have suffered accidents by forgetting to turn this little lever.”22 After this exchange the plot moved on, but this casual aside demonstrates how cleverly Pell could insert farm tips into her stories. It also illustrates a typical setup on The Gillans regarding character interaction, particularly Angus’s role on the show. Jack Johnson explained that the show took a “father knows best” approach in regard to its educational content, with Angus presented as a knowledgeable patriarch explaining to the younger Gillans, and sometimes his neighbours, the benefits of better farming methods or gently reprimanding them for errors in their ways.23

19 Another good example of subtlety is found in a July 1960 script. Mary Gillan was a keen flower gardener, and that summer she was the head of a committee organizing a flower show for the Littlevale Women’s Garden Club. The judge they had arranged for the show, however, backed out, and Mary was having no luck finding a replacement. Both Angus and Rob firmly refused to step in, ostensibly for lack of qualification, but it is implied they wanted nothing to do with a stereotypically feminine pursuit. Desperate, Mary turned to Henry Jones, but he too was reluctant for the same reason. In order to wrangle Jones into the position, Mary and Angus used his feud with Weatherbee to manipulate him by insinuating that they could ask his rival to judge. Jones was outraged, “WEATHERBEE! What does he know about flowers? Or . . . artistic arrangements? Or ANYTHING ELSE, for that matter?” Now thoroughly riled up, Jones immediately volunteered his services to save the women from being involved with that “pot-wallopper Weatherbee.” It makes for an entertaining episode, so much so that listeners might have missed the tip: when the Gillans first approached Jones, he was on his way to his sheep pasture with a scythe in hand to, he explained, trim down burdocks to prevent any damage to the wool.24

20 Subtlety was preferred, but at times the show could be more direct. This is seen in another early Pell script in a conversation concerning using limestone as a hayfield fertilizer. At this time, provincial agricultural agents were heavily promoting increased hay production as a means to produce greater dairy and beef yields.25 The greater use of chemical fertilizers on hayfields was a key component of this effort, and it seems The Gillans were recruited to ensure more farmers got the message. Singing the praises of limestone, Angus exclaimed, “We never had such a crop! . . . It acts as a plant food too – supplying calcium and magnesium – not only to the plant, but to the animals that eats the plant. . . . The Ag rep was telling me the other day that an investment of $45 in a can of lime will return $135 in increased production and improved soil conditions.”26 This is not to say that Angus was completely sold on using modern chemical fertilizers in place of more traditional methods. On one occasion, coming in for dinner after a morning picking potatoes, he cautioned that over-reliance on fertilizers depleted the soil of its natural chemical richness, and overlooked the benefits of natural fertilizers such as manure.27

21 When not encouraging farmers to adopt new methods of fertilizing their field crops, The Gillans was also encouraging them to try their hand at entirely new crops. This was likely indicative of the effort to diversify the Maritime agricultural economy, initiated, in part, due to the recent loss of the British apple market that had devastated many farmers.28 Several early Pell episodes, for instance, explore Rob’s efforts at beekeeping, an activity that would not only yield honey but also provide pollination; it was also mentioned that he learned a lot about the craft by acquiring free bulletins from the federal Department of Agriculture.29 The show also urged farmers to be cautious when trying their hands at new crops. Henry Jones was especially pleased with his corn in the summer of 1949. After years of struggle it seemed that Jones had finally acquired a green thumb and could not resist showing off his crop. Upon his inspection, though, Angus delivered some deflating news to Jones. Rather than the table corn variety that he thought he planted, it turned out that it was much less valuable popcorn. Jones obtained the seeds for free from a man passing through Littlevale, whom he had helped replace a flat tire. Even though the traveller was likely not a swindler, but only ignorant of what the seeds were, Angus made clear that he only used seeds obtained from registered vendors thus driving home the lesson to the listeners.30

22 Though The Gillans made space to discuss new opportunities, the issues most often raised centred on encouraging farmers to adapt new techniques to traditional work and/or to assuage any anxiety towards these practices. There was certainly a lot of novelty for farmers to absorb. The post-war era witnessed rapid and widespread farm mechanization, with traditional horse-powered farming being phased out in favour of machine-powered agriculture. The numbers reveal how dramatic was this transition: in Nova Scotia alone, between 1941 and 1961 the number of tractors increased by nearly fivefold from 1,386 to 7,034, while the number of farm horses plummeted from 36,172 to 8,917.31 Sunnybrae was no exception to this trend. Whereas in 1949 the Gillans were still using horse-drawn equipment, a decade later they had purchased tractors and various tractor-powered machines. The transition not only sped up the rate at which the Gillans harvested their hay crop, but also when they began their haying season. In the summer of 1960 Angus and Rob observed that thanks to their new machines they could begin the harvest at least ten days earlier, giving the fields enough time to produce a second crop.32

23 Despite this progress, there was a generational divide in the Gillan family regarding these changes, with Rob being more ready to adapt to the new environment and Angus far more hesitant. This was more than an older man being wary of change, but rather was rooted in practical concerns about the costs of machinery to farm finances and profits. This can be seen in one of the few times The Gillans were presented on television for an episode of Country Calendar. In the show the Gillans hosted Country Calendar presenter (and Gillans producer), Jack Johnson at Sunnybrae. In the course of their conversation Johnson and Angus discussed the problems mechanization posed to smaller farmers. Angus stated: “It’s a problem. Those of us who can’t farm BIGGER will just have to farm BETTER.” And when Johnson asked if this meant small farmers should adapt the latest techniques and acquire modern equipment, Angus replied cautiously: “Putting too much in machinery or buildings or expensive feed can take the profit off even the highest-producing cow.”33

24 This wariness can also be seen back on the radio in a 1960 episode, where Angus, Henry Jones, and Nelson (a curmudgeonly neighbour with no use for modern farming) visited Weatherbee’s farm to see his new hay conditioner, a machine attached to the back of the mower that crimped and crushed newly cut hay to allow quick drying, baling, and storage. Weatherbee boasted that the hay he was cutting would be ready to bale the following day, while it would typically require two days to dry. Jones scoffed at this and derided the machine as a new toy for “the suckers” being manipulated by the machinery companies. An annoyed Weatherbee retorted that the conditioner was the best machinery investment he had ever made, and, despite its hefty $900 price (nearly $8,000 today), predicted that within a decade “every farmer in the country will be pulling one of these behind his mower.”34 Weatherbee tried to convince Angus to purchase one, but, being skeptical about the machine’s cost and practicality, he declined.

25 Despite Angus’s misgivings, Sunnybrae was becoming increasingly mechanized and this posed a question as to what to do with the previous source of farm labour – the horses. The Gillans had two horses, a mare named Fanny and a gelding named Prince, who had provided invaluable service to the farm and had, in a sense, become companions of the family. Angus was particularly attached to Prince and bristled at any suggestion that the horses were obsolete or did not pull their weight. His sons were of a different mindset. In one episode, Rob and John were discussing what space there was available in the Sunnybrae barn to house additional livestock and new machines. John stated bluntly “The day of horses are over,” and the Gillans should get rid of them to free up space and feed for profitable livestock. Rob agreed, but, aware of their father’s feelings, declined to take his brother’s advice even though John insisted that Angus was a “practical man” who would see the wisdom in it.35

26 Unbeknownst to the brothers, Angus was in the barn and overheard their conversation. After Rob and John left, their father went over to see Prince, and, after weighing his sons’ words, stated “I can’t do it . . . twenty-five years.” He then went into a lengthy recitation of Burns’s “The Auld Farmer’s New-Year-Morning Salute to his Auld Mare, Maggie,” in which a farmer pays his respects to an aged horse for her years of hard work.36 In the end, a solution was found for the Gillans to keep their horses and house new livestock and machines by renting a retiring neighbour’s barn. Pell’s script sheds light on an emotional side of farm mechanization that is often overlooked and highlights not only the deep attachment that many farmers had to their horses, but also the reluctance of many to put them aside despite the obvious economic rationale for doing so. No doubt many listeners could relate to the conundrum that Angus and his sons were facing.

27 Though the bulk of the tips and educational material on The Gillans focused on the traditionally masculine farm labours, the program also made space to discuss the feminine, domestic sphere of farm life. In the process, the show offered a glimpse into the changing rural gender relations. As the aforementioned flower-show tiff demonstrates, most denizens of Littlevale held traditional ideas on the proper male and female spheres, as, admittedly, would most of their listeners. The show addressed women’s issues accordingly, and most tips for women concerned how to improve housework or laid out recipes that farm wives might want to try. Pell’s scripts nonetheless show the stirrings of changing attitudes. The Gillan women often pushed back against longstanding patriarchal assumptions, albeit gently and, like their men, were navigating through the challenges of modernity.

28 Women’s issues were, for the most part, also subtly interwoven into the show. In one episode, for example, Rob came upon his mother putting her curtains back up after cleaning and ironing them and asked why she has put wax paper over the ends of the rods. She explained: “If you put a piece of wax paper over the end of the rod, it will slip through the curtain without catching or tearing it.”37 This tip was inserted as an aside, but at other times advice was more direct – especially when it came to relaying recipes. In mid-summer 1949 the Gillans took on a female boarder, Georgia Grey, a city woman seeking a stay in the country to soothe her jangled nerves. Georgia is something of an anomaly in Littlevale: a single, middle-aged, working woman who came from a modestly well-off family.38 Due to her family situation she had never cooked before, but was eager to learn. Over the course of her visit Mary obliged by instructing her (and the audience) in recipes for such things as pies, pickles, Yorkshire puddings, and preservatives. Of course, dinner hour was not an ideal time for farm wives to be listening to the radio with pen and notepaper in hand. Consequently, during one lesson on canning apples Mary pointed out that she acquired the recipe for free by writing the federal Department of Agriculture and assured Georgia (and the listeners) that “when the home economists of the Department recommend a method or recipe, you can depend on it to be good.”39

29 In the post-war era, old hands in the kitchen such as Mary often found that they had much to learn. Domestic labour stood on the threshold of a revolutionary transformation, modernizing at a pace no less rapid than other forms of work. As elsewhere, much of the change was driven by technological innovation. Labour-saving electrical devices, such as washing and drying machines, stoves, vacuums, and sewing machines – to say nothing of electrically provided light and hot water – made housework considerably less strenuous and time-consuming. These new gizmos being electrically powered meant that any who wished to take advantage of them would have to have access to electricity in their homes. Fortunately, the era was witness to a massive program of rural electrification where governments invested heavily to provide cheap electrical power to rural areas.40

30 While the benefits of electricity to both labour and leisure were obvious, as with all change it was greeted with some trepidation. When the Pell scripts began, Rob and Ann were living in the same house as Angus and Mary, despite having been married for some time. The young couple had built their own home on Sunnybrae, and had outfitted it for all the modern electrical devices that Ann would desire, but it had recently burnt to the ground in a fire caused by too many appliances overloading the circuit. This experience, unsurprisingly, had made the Littlevale women wary of electrical appliances, and several episodes from around this time focused on making kitchens more convenient and efficient without resorting to electricity.41 Reticence towards electricity did not last, though, as a decade later Ann was happily enjoying an electrified kitchen in her rebuilt house, whereas Mary still had a wood stove that in the summer could turn her kitchen into a veritable sweatbox. Ann tried to convince Mary to get an electric stove, and, though somewhat receptive, like many women of her generation, she remained wary of electric kitchens and kept her wood stove for the duration of the series.42

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 331 The concerns of the Gillan women were not confined to the kitchen. Several episodes touched upon their involvement with their local Women’s Institute. Women’s Institutes were associations of rural women that allowed them to collectively work to better their communities through volunteer work while also promoting culture and the learning of modern homemaking techniques. First emerging in Ontario in the late 1890s, the Institutes proved popular and quickly spread across Canada, reaching the Maritimes in the early 1910s and subsequently the United States and Britain.43 On The Gillans, Georgia Grey’s presence again provided a plot device to allow Mary and Ann to explain the benefit of the Institutes and promote the good works they did in fostering better homes, better schools, and better communities.44

32 Their Institute activity aside, most in Littlevale, including the Gillan men, regarded a woman’s proper place to be in the home. This fact was illustrated in an episode where Ann, a teacher before she married Rob, was offered a chance to teach again. The local school board was searching for a permanent teacher for the upcoming school year and approached Ann with an offer to fill the role until they found a suitable candidate. Both Ann and Mary were favourable towards the idea, but Angus and Rob were opposed – largely because they felt it not right for a married woman to work. Angus was particularly acerbic on the matter – “It’s not natural. A married woman ought to be home with her family” – even though, as Mary pointed out, Ann and Rob had no children yet and the job represented some extra money. Rob was more diplomatic than his father but was nonetheless wary, seeing it as a threat to his status as the family breadwinner and something that would take up their mutual spare time. Ann provided similar counter arguments to Mary and, in the end, Rob reluctantly agreed to her returning to the classroom.45 Much to Rob’s surprise, however, Ann turned down the offer, informing Rob that they will soon have “a brand new little responsibility” in the form of their first child.46

33 Time passed and Ann and Rob’s family grew to include four children, and Sunnybrae grew along with them. While in 1949 Angus and Rob were still using horse-powered machines, by the early 1960s they had two tractors. Likewise, where they once milked 10 cows, by the 1960s they had 30 and had also expanded their herds of pigs and sheep. To feed their increasing livestock they had expanded their land under cultivation, and even bought new property to cater to their expanding operations and built a silo to house the excess hay. While most of their cultivated land was devoted to producing hay, some shrub land was converted into productive blueberry and strawberry patches, and they had set apart sections of their woodlot for Christmas tree cultivation. The Gillans were also planning to physically expand their operation by renting the barns and fields of a retiring neighbour and purchasing his milk quota. All these efforts were returning the Gillans increased yields, thanks in no small part to the modern methods Angus and Rob applied to their operation. All in all, Sunnybrae, though not especially large, was operating along business lines and returning a decent profit.

34 The Gillans were adapting well to changing times, but not all change was welcomed. In August of 1960, while the show was on its summer hiatus, James Robertson, the actor who played Angus, died suddenly from a heart attack. Robertson’s death promoted an outpouring of grief from Gillans fans, inundating the program’s producers with letters and calls from all over the Maritimes, and engendered some questions about the show’s future. Most fans wanted the show to continue, but were adamant that Angus not be recast as they regarded Robertson as irreplaceable. In the end, after seeing the fan reaction, the producers decided to let the character die as well. Thus, with permission from Robertson’s family, Angus Gillan died in the same circumstances as his performer.47 When listeners tuned into The Gillans on 29 August, they were greeted by the announcer solemnly intoning “Three weeks ago, on a sunny summer day, tragedy struck the Gillan family. Angus came in for his dinner one day . . . and didn’t go out again to the fields he had worked for so long. Death came quickly . . . and without prolonged pain. But there is pain in the hearts of those who loved him.”48

35 The death of Angus was an emotional moment on The Gillans.49 In its aftermath, Pell skillfully depicted a family coping with a sudden bereavement in a realistic and relatable manner. Angus’s death left them emotionally drained and short-tempered, frequently snapping at one another or breaking down in tears at the mildest provocation. Through it all Rob Gillan behaved as men were expected to, stoically and without much display of emotion, but the scripts carry instructions for his performer to “pause” or “breathe in” whenever anyone complimented his father’s character, indicating that he was steeling himself to retain his composure. But Angus’s death provided The Gillans with more than just an opportunity to showcase familial grief. In keeping with its educational prerogative, it allowed for the show to addresses issues it had never had the chance to tackle before such as the passing of a property from one generation to the next and all the legal procedures that went along with it. For the sake of realism, the settlement of Angus’s estate was presented in a drawn-out fashion, and his sudden passing posed many unforeseen consequences for his family.

36 Fortunately for the Gillans, Angus had left a will and, even before its reading, all were confident that he had bequeathed Sunnybrae and all its accoutrements to Rob. Pell’s scripts stress the wisdom of Angus preparing a will, thus encouraging her listeners to do the same – largely for the sake of their families. This is made clear a few weeks after Angus’s death, when Mary received an unexpected visitor, Florence Cooper, a former resident of Littlevale whom Mary had not seen for years. Florence was back visiting her brother, Bob, who now owned their family’s farm, and had come to Sunnybrae to pay her respects to Angus. Florence expressed relief when Mary informed her that Angus left a will, relating how her own father’s death precipitated a falling-out among his children. Her father died without a will and afterwards Bob sought to take over his operation, which did not sit well with Florence and their other brother Hank.50 A settlement was eventually reached, whereby Bob got the farm and his siblings received some financial recompense, but even so the family rift was deep and had only recently begun to heal. A few weeks later Rob and John expressed similar relief that their father left a will, citing the Coopers’ example as something they were fortunate to avoid.51 The lesson from these episodes is clear: a farmer should have a will prepared, even if he is young and healthy, to ensure an orderly settlement of his estate and to ease the strain on his grieving family.

37 Even though there were no family squabbles over Angus’s estate, this did not mean that settling it was entirely smooth sailing. The reading of the will was delayed for several weeks due to the Gillans’ lawyer, Mr. Foley, being away. The will, when finally read, confirmed Rob’s status as the heir of Sunnybrae while Mary was bequeathed the house she and Angus shared as well as his remaining money and insurance, with additional money set aside for Angus’s other children and his grandchildren.52 Rob was surprised to learn that the reading of the will was not the end of the matter, as Foley informed him that he still had to make a petition of probate and have the estate appraised before all was settled. Fortunately, Rob and Angus had been keeping an annual farm inventory for several years, which made the process all the easier. The local bank manager, whom Rob asked to act as an appraiser, expressed his shock and relief at this, humourously emphasizing the episode’s lesson: “Inventory? You already have an inventory? . . . Let me look at you! . . . Most farmers would rather fork two loads of hay after supper than do a bit of writing. . . . A farmer doesn’t seem to mind the smell of manure . . . but the smell of a bit of ink seems to make him sick.”53 In the weeks that followed, Rob, as executor, went through all the required motions: filing a petition of probate, having the appraisers take stock of the estate, advertising the estate in The Royal Gazette, and preparing to pay off any debts and taxes Angus still owed.

38 Throughout all this Rob served as a stand-in for the average farmer. Most listeners would likely have known little about these legal procedures and would have shared Rob’s aggravation at how time consuming and byzantine it seemed. At one point, after being told that the estate still owed additional income tax, Rob’s frustration boiled to the surface, and he sputtered in anger: “Hey, you know what I think? I think this whole thing is just a racket! A man works hard all his life – like Dad did – when he – dies, well, why can’t his – whatever he has just go to – whoever he wants to have it . . . . Lawyers! The trouble is the government is full of lawyers! Naturally they make laws to give themselves work!”54 The next episode featured an extended dialogue between Rob and Foley wherein the lawyer explained to him, and the listeners, the necessity for all the “rigmarole,” stressing that the laws were in place to protect people and that their complexity was only to ensure that there were no loopholes or oversights.55

39 As the fallout from Angus’s death demonstrated, the farmers’ world was becoming increasingly complicated. Farmers were learning that in order to succeed they needed to know how to navigate a labyrinth of legal, bureaucratic, and financial regulations. Rob and John were not shy about expressing their frustrations about this, but it was clear to them that they had no choice but to accept it. Weatherbee, ever the progressive farmer, chided the Gillan boys and other farmers for their reticence to adapt to the modern world. Singling out the use of accountants, he declared: “Too many farmers are scared of them fellas. . . . If you’re going to accumulate you have to speculate a little. . . . Thunderation, I don’t know what’s wrong with you young fellas these days! . . . The management and the paperwork. It’s what’s keepin’ small farmers small. They’re scared of the paperwork.”56 In response, Rob acknowledged that farmers need to adapt to changing times, no matter how difficult the process may be.

40 Much of the focus of The Gillans’ final decade concerned Rob and his operation adapting to changing times, and all the difficulties that entailed. Farming was becoming an industry built on brains as much as brawn, and established and aspiring farmers needed to reconcile themselves to this new reality. Agricultural education was no longer a luxury or an indulgence, but a prerequisite for farming success. Angus had always spoken in favour of farmers availing themselves of what agricultural educational was available to them. At one point, Angus inserted himself into an argument between two teenage boys, Donald and Bobby, who were working as day labourers at Sunnybrae. While their argument was ostensibly over potato cultivation, the boys were actually sparring because they were pursuing the affections of the same girl. Donald, seeing an opening, acted like a know-it-all on potato farming by showing an impressive knowledge of their cultivation and marketing, which led Bobby to dismiss him as a “bookworm.” It was at this point that Angus interjected: “And what’s wrong with books, lad?” Bobby replied that his father “says you can’t farm out of books. Don here’s going to be wasting his time in Agricultural School, while I’m getting the real thing on Dad’s farm.” Angus, though, would have none of this attitude: “You’re in the wrong furrow when you sneer at Agricultural Colleges. I just wish I’d had the advantage of such training when I was a lad.”57

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 441 Angus’s recognition of the importance of education was seen in his will, where he left each of his grandchildren $300 to assist in their “education and establishment.”58 While not legally binding, Rob took this to mean that the money should be set aside for college funds. After hearing the will Rob spoke with his eldest son, Billy, and pressed upon him the importance of honouring his grandfather’s wishes. Billy, whose first impulse was to use the money to buy a new bike, was reluctant to endure any more education after high school and pointed out that neither his father nor grandfather went to agricultural college. Rob countered that modern farmers needed education in agricultural science and modern business practices if they hoped to succeed, and the matter was settled that the money would be set aside for a college fund.59

42 Though Billy was initially disappointed, the college fund proved to be a wise investment, as by the series’ final years Billy was indeed attending agricultural college. After a few years at the NSAC at Truro, he went on to further his studies in Montreal at Macdonald College of McGill University. By this time any reticence about furthering his schooling was long past, and he was now an enthusiast for applying modern farming methods to the operation of Sunnybrae. While in 1960 he had been dismissive of a farmer needing to learn book keeping, by 1970 he was urging his father to consider adapting his accounting and inventory to the nascent digital age by joining the “Canadian Farm Management Data System” – or “Can Farm” for short – a computerized book keeping system.60

43 Science undoubtedly brought some welcome benefits to farmers, but not all its effects were benign. Among them was the increasing reliance of modern farming on chemical fertilizers and pesticides. While these were good for increasing the quantity and quality of produce outputs, they carried with them threats to the natural world. By the turn of the 1960s these threats were becoming all too evident to the public at large, and the effects of the pollution had become a prominent part of public conversation. The debate around pollution was not limited to that resulting from modern agriculture but rather covered a variety of subjects, including the radioactive fallout from nuclear testing, the chemical waste stemming from industrial production, and the massive use of insecticide spraying of commercial forests.61

44 The Gillans did not shy away from tackling these hot-button issues, but one can discern a decidedly different attitude between how the show approached the matter of pollution in the early 1960s and the early 1970s. Most of the early environmental concerns raised on The Gillans pertain to the use of chemical pesticides. A few weeks before he died, Angus and Mary had a conversation pertaining to the infamous flower show. Mary informed Angus that Ann had decided against dusting her choice for the show, a rose, with the insecticide DDT for fear that any birds eating dead bugs or worms could be killed or sickened in turn. While Angus believed the birds would not eat dusted worms, he conceded “We don’t have as many birds as we used to, and I suppose spraying’s in part responsible, but – . . . .” Before he could continue equivocating, Mary interjected and asked when was last time he saw a bluebird while noting that there were fewer and fewer robins returning every spring – to which her husband had no reply.62 Later that episode Mary raised the topic with Rob, who was more confident about the safety of chemicals than his father: “Aw, DDT doesn’t kill birds. Not at the recommended rate anyhow.” He blamed any harm the chemical did to birds on farmers not following the directions and using more than the recommended dosage, thinking it would bring them better results. He also made an economic argument, stating that farmers needed to spray to compete as modern consumers would not buy “wormy vegetables or scabby apples.” To this Mary reluctantly conceded, but decided that “for the kitchen garden – and certainly with flowers – well . . . I think from now on I’ll settle for a few less flowers and a few more birds.”63

45 The danger of spraying was not limited to birds. In one episode, Rob offered to spray Nelson’s potato field with “topkill,” an arsenic-based herbicide designed to lessen the number of vines on potato plants and thus increase the tuber size. Nelson initially declined, citing an example of a farmer in nearby Ridgeville who lost three cattle from drifting “topkill” spray. Rob assured him that the deaths were not the result of drifting, but from the cattle getting loose from their pasture and eating the sprayed plants. Rob guaranteed that if Nelson kept his cattle in their pasture the spray would not hurt them, and this convinced Nelson to allow Rob to spray.64 A few weeks later Rob was horrified to learn that Nelson had lost two cattle from an illness that sounded like chemical poisoning. The cattle never got out of the pasture to eat the sprayed plants and Rob insisted there was not a breath of wind when he sprayed, which ruled out drift. Nonetheless, Nelson blamed Rob’s spray for the deaths. As the local veterinarian, Dr. Harris, was conducting a post-mortem lab report, Rob promised to pay for the dead cows if the report concluded that his spray was responsible.65 Harris’s report did conclude that the cattle died of arsenic poisoning, but it turned out that they were poisoned by Nelson’s carelessness rather than Rob’s spraying. Due to a dry summer parching his pasture Nelson had been giving his cattle mill feed, and some improperly stored “topkill” was accidently knocked into the pail he used to mix the feed. Harris concluded the episode by driving home the moral: “When will you fellows learn that you’re handling POISON. You’ve got to learn to follow the manufacturer’s instructions. And . . . if you’ve GOT to save it . . . store it properly.”66

46 The lessons drawn from Nelson’s poisoned cows are typical of The Gillans’ earlier approach to environmental issues. The chemicals used in agriculture did pose a risk, although said risk was limited to people and animals in the immediate vicinity of their use. To mitigate the risk, the onus was on the farmers to educate themselves on how to use chemicals safely and, if used properly, farmers could expect their operations to benefit from them. By 1970, however, the situation had become more complicated. The people of Littlevale were now aware that the ecological risks posed by modern agriculture were wider and deeper than originally feared, and that these were part and parcel to a grander trend of ecological despoliation brought on by industrial modernity. By 1970 Littlevale’s river, once a source of local recreation, including fishing, swimming, and rafting, has been condemned due to contamination from sewage and industrial runoff, both rural and urban, though the Gillan family was hopeful that an effort to establish a water treatment plant could alleviate the problem.67

47 This did not sit well with Henry Jones, who in the show’s last years became Littlevale’s resident ecologist. In one instance, while arguing with Weatherbee in his store over a tardy order of strong rat poison he stated: “It is against my better judgment to contribute to the use of stronger and stronger pesticides.” Weatherbee was indignant: “That ain’t pesticide, that’s RAT KILLER,” but even Weatherbee was not oblivious to the threats of pollution: “We might be gonna die of pollution all right – them fellas that’s dumpin’ the oil in the water . . . killin’ off plankton, THEM fellas is playin’ with fire, but we ain’t gonna die of PESTICIDE pollution.” He then made familiar economic arguments for its use. Jones was unmoved by this reasoning, countering that people would be healthier eating non-sprayed produce: “You can take worms OUT, but you can’t take the spray residue out.”68 On another occasion, while with talking with Rob and Weatherbee, Jones decried the rising trend of confining of cattle to feed lots as it broke the natural cycle of grazing and manure fertilization and thus increased the reliance on chemical fertilizers. While Rob was somewhat sympathetic, Weatherbee was dismissive and mocked Jones as a “pollution nut.” Unmoved, Jones ended with a dire warning that modern man had been waging a war against nature “and the consequences are beginning to come home. . . . Instead of stepping UP the war, it’s time we de-escalate it, because it’s a war we can’t possibly win.”69

48 Episodes from the last years of The Gillans frequently show the characters coping with other forces of social and cultural change, such as secularization, women’s liberation, and, most distressingly, the ongoing exodus of young people from the countryside. In one episode, Rob had a conversation with the local preacher, Elwood, who asked Rob how many of his sons he anticipated would remain in farming. After a pause, Rob said that he hoped at least one, presumably Billy, would come back to the farm; but Rob also wanted all three to get an education, as it would “raise their sights.” He then laid out a scenario where he allowed Rob Roy to stay home to work the farm after high school, with the result of the lad becoming frustrated from a lack of money and spare time and comparing himself unfavorably to a young man his own age working at a service station. Hardly a glamorous or high paying job, but it boasted an eight-hour workday, a steady salary, and more time off, allowing him to afford a car and entertain a girlfriend. With such inducements, Rob doubted any young person would stay in farming. When Elwood asked about possible solutions, Rob mentioned farms he has heard of that were run along business lines – that is, a two-man operation, with each taking an eight-hour shift. Elwood observed that it looked like the traditional family farm was on the wane, to which Rob, with a heavy heart, agreed.70

49 This conversation sums up the milieu of rural Canada in the early 1970s. For The Gillans and their listeners the world was rapidly changing around them, and there was little they could do but adapt as best they could. For the show this meant, as it had from its earliest days, encouraging its listeners to keep their operations up-to-date with the latest farming methods and technology, and being ever mindful of the demands of the market. To this end, the program was an important component of the effort to modernize Maritime farming, always encouraging its listeners to gear their operations towards maximum efficiency and profit. It had much success in this, as agricultural extension representatives frequently reported that the program was a great source of information for farmers and that it helped motivate farming people to improve both their operations and local communities.71 Maritime farms had become much more market-oriented, mechanized, and efficient by the end of its run than they had been at the show’s outset; but these same forces also ensured that only those farms with sufficient capital and land could remain afloat, resulting in a winnowing of the farm population. The anxieties surrounding the collapse of the Maritime farm population were reflected in the final years of the show. The Gillans could do little to combat these forces, but likely helped farmers cope with them by providing them an entertaining reprieve from their woes as well as a voice of solidarity and consolation in troubled times.

50 The Gillans program itself could not adapt to the changing times. By the late 1960s a declining rural audience prompted the CBC to scrap most of its farm-themed programs, including the Farm Radio Forum and the other regional farm family dramas. For a time, The Gillans bucked this trend, persisting until 1972 when it too was cancelled. Why this longevity? Jack Johnson likely had a point when he argued that The Gillans outlasted its sister Farm Family Dramas by virtue of it simply being the best of them.72 Jean Pell’s writing skills, its charming characters, and the talented cast and engineers brought something to The Gillans that the other dramas lacked, keeping listeners tuning in longer. An equally important part of its appeal was the positive image it projected of farming and farmers. Johnson later recalled that The Gillans, being intelligent, ambitious, and progressive farmers, “gave rural people . . . a sense of their own dignity” and “a feeling of self value and self esteem.”73 To be sure, the characters on The Gillans were not perfect. They made mistakes and could be stupid, rude, lazy, or stubborn; but these flaws just made them more relatable, and the creators made sure that their underlying morals were impeccable.74 It is important to note that The Gillans also had a sizable urban audience. Despite having no vocational reason to tune in, many town and city folk did so because they were drawn to the appealing characters and entertaining stories.75 Thus, pure entertainment was a key factor in The Gillans’ wide and lasting appeal. As Johnson put it, “They were a lot of fun.”76