Articles

A Black Ship on Red Shores:

Commodore Matthew Perry, Prince Edward Island, and the Fishery Question of 1852–1853

Michael B. Pass is a graduate student at the University of Ottawa, where his PhD dissertation explores Canadian-Japanese relations during and after the Second World War.

Résumé

En 1852 le droit des pêcheurs américains de pratiquer leur métier au large des colonies de l’Amérique du Nord britannique fit l’objet d’un différend entre la Grande-Bretagne et les États-Unis, qui nécessita l’envoi d’un navire de guerre américain sous le commandement du commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry pour procéder au levé des zones de pêche et négocier avec les autorités locales. Cet incident fournit l’occasion d’explorer comment les relations diplomatiques entre Britanniques et Américains contribuèrent à prévenir la résurgence d’un conflit après la fin de la guerre de 1812, et comment elles eurent une incidence sur l’expédition subséquente de Perry au Japon en 1853-1854, ce qui démontre l’importance contemporaine des colonies en tant que ligne de démarcation géopolitique entre la Grande-Bretagne et les États-Unis.

Abstract

In 1852 controversy arose between Great Britain and the United States over the right of American fishermen to ply their trade off the British North American colonies, necessitating the dispatch of an American warship under Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry to survey the fishing grounds and negotiate with the local authorities. This incident provides an opportunity to explore how Anglo-American diplomacy both helped prevent a resurgence of conflict after the end of the War of 1812 as well as how it influenced Perry’s later Japan expedition of 1853-1854, demonstrating the contemporary importance of the colonies as an Anglo-American geopolitical fault line.

1 On the morning of 20 August 1852, the British warship HMS Telegraph entered Charlottetown harbour in company with the American fishing schooner Golden Rule. The schooner and its 11-men crew under the command of Captain Israel Bartlett had been seized two days previously near Cape Kildare on the Island’s north shore by the Telegraph’s captain, W.N. Chetwynd, for fishing within three miles of the shores of a British possession, a violation of treaty between Great Britain and the United States. According to the letter of the law, the 70-ton Golden Rule, her catch, and all her equipment would be impounded, taken into the nearest British port, and then auctioned off in the Court of Vice-Admiralty. This was terrible news for Captain Bartlett as his ship – barely 15 months old and only on her second voyage to the fishing grounds – had already suffered trouble off Prince Edward Island in 1851. That October the Golden Rule had run aground during the massive storm later dubbed the “Yankee Gale,” and while Bartlett and his crew had escaped unharmed the cost of re-floating and refitting their ship had put them $1,500 in the red. If the Golden Rule had to be repurchased at auction, Bartlett (as part owner) and his fellow crewmen might go bankrupt. Hat in hand, Bartlett went ashore to engage the services of Charlottetown lawyer John Longsworth to draw up a petition to the authorities. Admitting to breaching the convention, Bartlett pleaded that the ship was his only real property and that he would be ruined without her. Luckily for the Americans, British Vice-Admiral Sir George Seymour arrived three days later and the schooner was released without charge. The Island press voiced bipartisan approval and, as Prince Edward Island Lieutenant-Governor Sir Alexander Bannerman put it, this was “an act of clemency to the master, a poor man” who had expressed “great regret at the infraction.”1

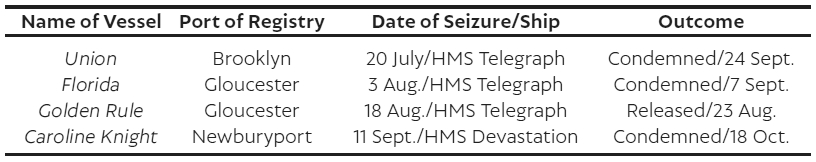

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 12 The Golden Rule was lucky; the authorities would catch three other American fishing vessels trespassing in Island waters during 1852 and they would not escape so lightly. “Several small fishing vessels seized & brought in,” the Charlottetown diarist David Ross noted that August – “like[ly] to be a rumpus with the Yankees.”2 Ross was correct. In what contemporaries would refer to as the “fishery question” of 1852-1853, British warships would take numerous American vessels into ports across the British North American (BNA) colonies – an act that provoked violent criticism by many Americans, not the least by the fishermen themselves. This was an issue that had been simmering for many years. In 1851, Bannerman had observed that American fishermen “daily infringe the Treaty by fishing close to the shore.” British warships, he hoped, would be sent to help as it was clear that “the United States Government cannot be expected to send one of their cruisers to enforce it and otherwise to keep the peace among them.”3 In this prediction, however, Bannerman was to be proved wrong, for at the same time the Golden Rule was released the USS Mississippi under the command of Commodore Matthew Perry had already entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence bound for Prince Edward Island and the fishing grounds.

3 Today, the 1852-1853 fishery question provides an excellent opportunity for a diplomatic and political history of Anglo-American relations during the 19th century and how the BNA colonies were a major geopolitical fault line between both powers. From the Anglo-colonial perspective, it allows for an exploration of why Britain and the United States did not come to blows again after the end of the War of 1812, a trend which eventually culminated in today’s long, undefended border between the United States and Canada where war is now seen as unlikely if not inconceivable. This is noteworthy given that the 1852-1853 fishery question has not received the same scrutiny when compared to other incidents of this era, such as the Oregon Dispute of the 1840s or the Trent Affair during the American Civil War. From the American standpoint, it allows for a focus on Commodore Perry and how his journey to the fishing grounds provides a hitherto unexplored perspective on his later Japan expedition of 1853-1854. By comparing the actions Perry took in the BNA colonies with those he took in Japan, it allows us to better understand why he took an uncompromising stance with the Japanese authorities to open the country to foreigners. It also allows for an exploration of American self-perceptions at a time of national growth and rising self-confidence as the nation expanded westward – self-perceptions that occurred within ongoing debates over its civilizational progress, which dominated discussions over its place in the world.

4 In keeping with the increasingly global study of Atlantic Canadian history, this article places the events of 1852-1853 in a multinational context – a logical progression given the growing body of work on the broader Anglo-American “fishery question” and its historical legacies.4 This is also timely given that many prior studies, written either solely from the American or Anglo-colonial perspective, have often given misleading or incorrect accounts by relying on a mono-national list of sources.5 Using accounts from both sides – with the Prince Edward Island experience anchoring a single, coherent narrative across the diverse experiences of all the BNA colonies – this article examines the political decision-making process behind the fishery question and the voyage of the Mississippi before concluding with an analysis of its significance to both 19th century Anglo-American relations and to Commodore Perry’s Japan expedition. In doing so, it tries to recreate the complex global world occupied by the BNA colonies during the mid-19th century when British orders from London could impact American missions to Japan.

A Yankee rumpus

5 The convention at the root of the 1852-1853 dispute had been established a generation earlier in 1818. After the War of 1812, the British and Americans had signed an agreement allowing the Americans to fish in the Bay of Fundy and the Gulf of St. Lawrence provided they kept three miles offshore and followed local laws when they went ashore for provisions, repairs, or to shelter from bad weather.6 The 1818 Convention, however, quickly became a sticking point between both sides. The Americans had taken to fishing off the British colonies in the 1830s due partially to the migration of the mackerel, their most prized catch, but also because of the undeveloped state of the region’s own fishery. In Prince Edward Island, the lack of money for such an industry was the key concern; one enterprising Islander suggested in 1832 that such money might be found through the creation of a sort of joint stock company. After all, he argued, “this source of wealth” should not be left to “the numerous sail of American fishing crafts that constantly visit our fishing ground.”7 Still, by the 1850s, little progress had been made. In 1851 Bannerman could still lament that “it must be a long time ere the colonists can find a proper class of men, numerous enough to prosecute the fishery on the same system of sharing as the Americans carry on with great success.”8 Through the 1840s, as both cod and mackerel became scarce off New England, the Americans began to follow the mackerel migration routes into the Bay of Fundy and Chaleur Bay in growing numbers, salting some 225,000 barrels of fish a year on average for the next half century.9 This movement of fishermen did not go unnoticed by the colonials. For Prince Edward Islanders, the American proliferation is best remembered for the ships lost in the previously discussed Yankee Gale, when around 120 American vessels were initially reported missing and numerous ships – the Golden Rule included – were shipwrecked on the Island. A later American report would officially tally the disaster at 49 vessels with a loss of life of 219 sailors.10

6 By 1852, this move northward had brought the Americans into conflict with the colonials and reports of wrongdoing by truculent or drunken Yankees soon began to filter back to the British authorities. One of the earliest incidents for Prince Edward Island occurred in June 1838 when a barque, the Sir Archibald Campbell, was grounded off North Cape and promptly looted by a passing American fishing vessel. This “act of piracy,” as then Lieutenant-Governor Charles FitzRoy fumed to London, was part of a long series of complaints by authorities in all the BNA colonies against American fisherman.11 By July 1852, Bannerman had received word from the harbour master at Malpeque of several American vessels that refused to pay anchorage dues and how the harbour master “had not force enough to take so many vessels, each of them comprising a crew of from twelve to fifteen, and I could say well equipped for defence.”12 Still, the inclinations of most public officials and opinion makers on the Island appear to have been for restraint. As Henry Wolsey Bayfield, a Royal Navy surveyor stationed at Charlottetown, observed in his diary after conversing with Bannerman, Chetwynd, and other officers, controlling the Americans “should be done mildly and discreetly, although firmly; and in such a way as to give as little offence as possible” and that this task “should be a duty entrusted to responsible Naval officers only, and not to the irresponsible commanders of Colonial Vessels.”13 The pro-government press of the Island agreed. One editorial published that August in the Royal Gazette (the mouthpiece of Premier George Coles’s ruling Liberal party) condemned those Americans who fished within three miles while going on to denounce the failure of the fishermen at Malpeque to pay their dues and praising Bannerman for requesting British naval assistance in contrast to the calls from Nova Scotia to man their own ships to protect the fishery. But the paper also hoped that a deal with the Americans would still be “amicably and speedily adjusted.”14

7 Overall, the American encroachment did indeed worry Islanders. Yet, while much was made of American wrongdoing, given that hundreds of American vessels were visiting Prince Edward Island and the other BNA colonies every year, such events seem limited in retrospect. In 1851, for example, Bannerman had noted a case where “about 1,500” fishermen landed at Princetown to attend an agricultural show. He conceded that they “behaved as well and peaceably as so many sailors congregated together could be expected to do,” yet warned that “this will not always be the case where brandy and rum are to be had cheap.”15 Barring the occasional incident of drunkenness, however, most fishermen seem to have had a profitable relationship with locals. Many bartered with Islanders for local produce, and in one instance an American crew even left behind a companion “of unsound mind” in the care of a local doctor for treatment.16 As one journal later reported after speaking with older Islanders about the fishermen, “To their credit be it said, that on the whole, they were a manly, respectable lot, and only rarely, and that when intoxicated, did they seek a quarrel.”17 Indeed, American misconduct was as likely to be the victim of satire as of genuine anger. In 1860 the self-styled “Island Minstrel” John LePage published his mock-epic poem, “The Great Battle of Georgetown,” comparing an 1855 brawl with the then-ongoing Crimean War. By the end of the “battle” many involved “had broken bones/And one was nearly slain,” while one fisherman (“Whose grandsire serv’d at Bunkerhill”) had successfully spiked the town’s only small swivel gun.18 Despite such strife to rival “bloody Inkerman,” in 1852 the Island’s legislature was prepared to resolve the dispute by repealing the 1818 Convention in return for reciprocal free trade.19 As Bannerman summarized the situation for London the following year, “In Prince Edward Island the people and Government are desirous that their neighbours [the Americans], in common with Her Majesty’s subjects, should participate in the fisheries, provided equivalent advantages be conceded by the Government of the United States.”20 While fishermen excesses clearly annoyed Islanders, most still hoped a positive deal would eventually be reached.

The fish wars

8 Nevertheless, not all colonials were as cynical or magnanimous. “Every day I am asked why our poor fishermen go to Labrador to carry on their fisheries,” a resident from the Magdalen Islands complained in 1852, “while hundreds of American and other vessels come here to catch fish of every kind which abounds at our very doors.” He went on to note an incident – “no longer ago than last year” – when “some half-intoxicated Americans were on the point of depriving a poor inhabitant of his life, without any provocation, while no one attempted to protect him.”21 One Nova Scotian commission had offered a “remedy” to the American fishermen in 1852 through their “immediate confiscation or punishment for the least infringement of the treaty of 1818.”22 In regions like the Magdalen Island or Nova Scotia – where a more viable fishing industry already existed unlike in Prince Edward Island – sentiments were more vocally anti-American, though even here quiet cooperation between “White-Washed Yankees” and Nova Scotian “Bluenosers” could still sometimes be seen.23 A picture thus emerges of American fishermen routinely breaking the three-mile limit, punctuated by occasional incidents of wrongdoing ashore.24 Complicating matters was the ambivalent British attitude towards reciprocity. Having repeatedly ignored appeals from all the BNA colonies on this issue for years, in 1852 the new prime minister, Lord Derby, believed that proper enforcement of the 1818 Convention could act as leverage in any negotiations with the Americans and chose to press the point. The colonial secretary, Sir John Pakington, thus sent a circular to all BNA governors explaining his government’s intention to finally take a harder line on the fishermen.25

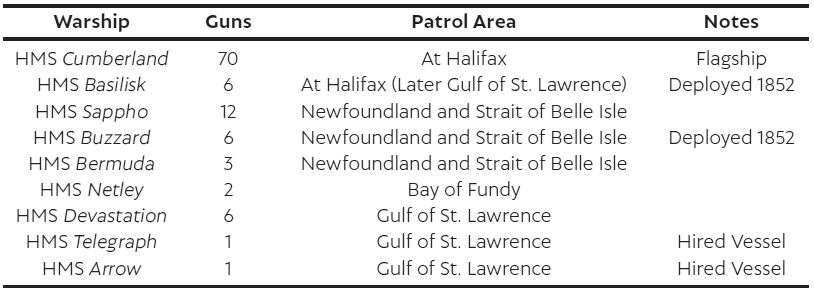

9 As a result, the Admiralty began to reinforce its North America and West Indies Station. By June 1852, two warships had been dispatched from Britain while two further vessels, the Telegraph and the Arrow, had been hired and put under Royal Navy officers (see Table 2). All fell under the jurisdiction of Vice-Admiral Sir George Francis Seymour, who had his flag in HMS Cumberland based at Halifax. Seymour quickly reorganized his command. In May, instructions went out to Commander Colin Yorke Campbell of the paddle steamer HMS Devastation to depart Halifax and patrol the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Campbell’s orders were to catch any fishermen breaching the three-mile limit, but Seymour allowed discretion for “more lenient measures” so long as the Americans got the message.26 In tandem with the Telegraph, these two warships captured all four of the American fishing vessels taken off Prince Edward Island in 1852. Little of this circumspection, however, informed American reactions.

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 210 When news reached the United States that American fishing vessels were being taken by British warships it evoked images of British arrogance at sea prior to the War of 1812, where the impressment of American seamen had served as the casus belli.27 To negotiate the issue, the Earl of Malmesbury, the foreign secretary, had been privately corresponding with British ambassador John Crampton to try to promote a calm discussion of matters with the American Secretary of State Daniel Webster.28 Yet news could not long be contained. Soon, reports in New England newspapers followed letters from concerned individuals in making their way into the hands of Washington politicians. One such report of a fishing vessel boarded by the Devastation that later made its way into the New York press claimed the conduct of the boarding officer had been “insulting,” that other vessels had been similarly mistreated, and that one vessel had even been fired upon.29 On 23 July, Virginian Democratic Senator James M. Mason raised a congressional motion for the Whig President Millard Fillmore to make public his negotiations with the British and report on whether any American naval vessels had been sent to protect their fishermen:

Mason admitted his doubt that this would lead to war. Nevertheless, he fumed “I feel deeply the indignity that has been put upon the American people, in ordering this British squadron into those seas without notice.”30 These views were echoed by other Democratic senators, most of whom correctly saw that events hinged on the issue of reciprocity. But Mason himself was scrounging for political points; 1852 was an election year and discrediting the government of the incumbent Fillmore could only help presidential hopeful Franklin Pierce and the Democrats.31 As Fillmore pondered a response, it was left to newspapers like the pro-Whig Washington Weekly National Intelligencer to counter Mason’s attack. Reprinting the press release prepared by Webster on his negotiations with Crampton, it argued – much as had the pro-government press in Prince Edward Island – that while there were clearly differences in interpreting the 1818 Convention both sides were willing to reconcile and had “amicable dispositions” about the matter. “They will certainly not fight about it,” the paper assured its readers.32

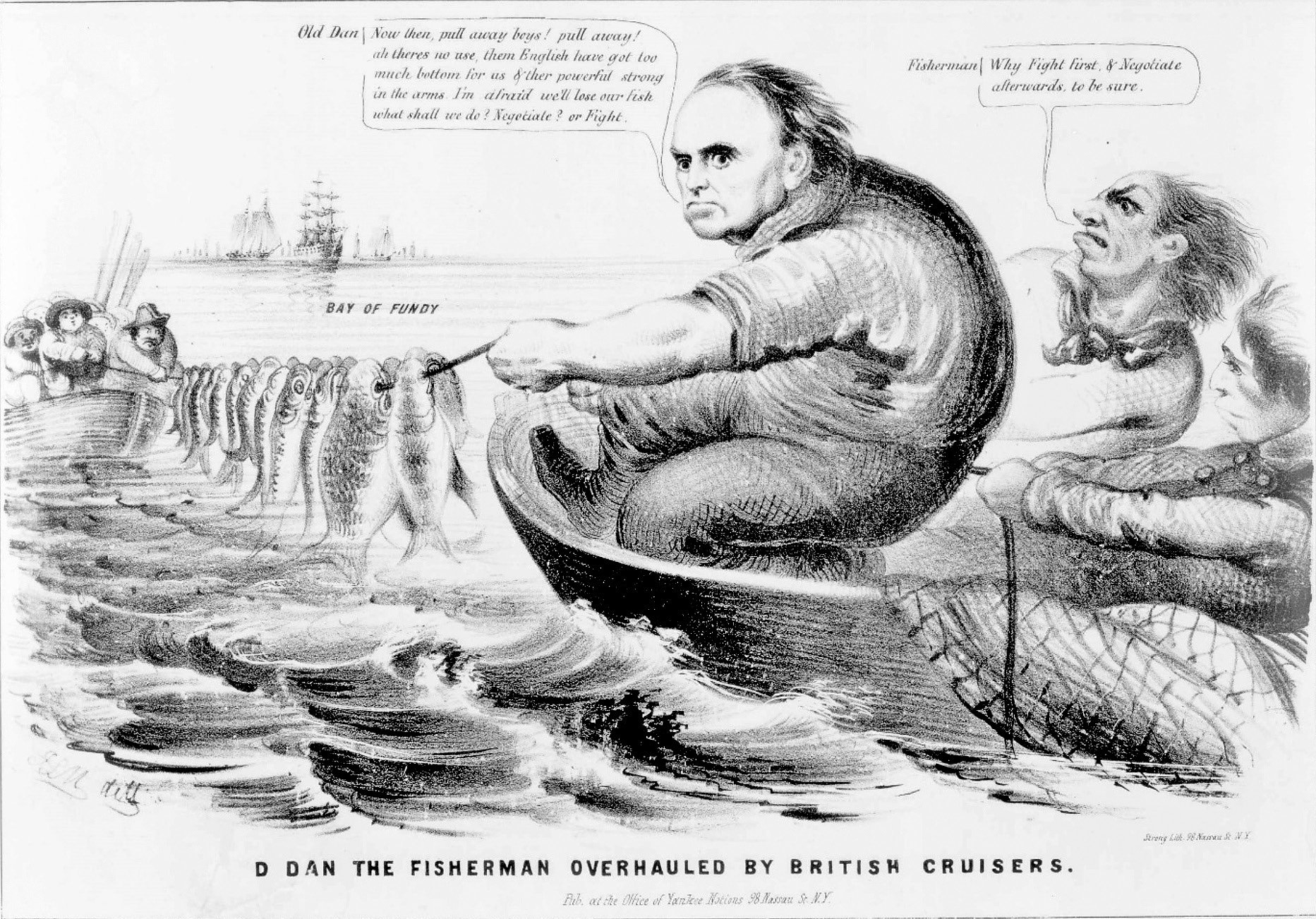

11 Yet, despite the calm views that prevailed among many Americans, there was also genuine anger.33 “A great excitement prevails here on the fishery question, and your conduct in the Senate excites the warmest approbation along the coast,” one New England letter writer enthused to Mason after his speech.34 One contemporary American political cartoon had an arrogant and unreasonable John Bull covered in fish being lectured to by Brother Johnathan while an American fisherman laments his vessel being taken by “that damned Britisher.”35 Another had a boat of fishermen led by Daniel Webster playing tug-of-war with a boatload of British sailors over a line of fish. Webster ponders whether they should fight or negotiate. “Why fight first & negotiate later, to be sure,” a fisherman recommends (see Figure 1). In reality a sickly Daniel Webster – he was, in fact, dying – lamented that he was being misused by the press but saw there was little he could do in his state, half-heartedly suggesting that perhaps he could travel north to discuss matters personally with the colonials.36 President Fillmore was equally concerned. With Mason’s speech, his administration could no longer debate the issue privately with the British; they would need to send a ship to the fishing grounds to make a show of government resolve and control rowdy Americans if needed. Luckily, the president had just the ship, and the man, for the job.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1Old Bruin and the fishermen’s pranks

12 Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry was not a happy man during the summer of 1852. A career naval officer whose gruff voice and stern personality had led many to dub him “Old Bruin,” Perry was also a widely travelled and scientifically minded sailor. In his long career he had promoted the steamship as the way of the future for the United States Navy, had sailed in numerous voyages around the globe, and had also played a major role in the 1846-1848 Mexican-American War.37 As of January 1852, Perry had been preparing for what he hoped would be the crowning achievement of his career: the forcible opening of Japan and their signing of a treaty with the United States. Since the 17th century Japan had refused to establish diplomatic relations with foreign countries despite periodic visits by Western “Black Ships,” which had tried to open negotiations.38 As American trade with China increased and as whaling ships began to frequent Japanese waters during the 19th century (and shipwrecked seamen began to claim abuse at the hands of Japanese officials), American calls to “open” Japan grew in intensity. Perry intended to end this impasse. Mustering a powerful naval force, he would sail directly for the Japanese capital of Edo (today’s Tokyo) and force their government to come to terms.39

13 Yet by July 1852 that plan appeared to have stalled. “We hear nothing, of late, of the Japan expedition,” an editorial in the New York Herald observed. “Is it given up? Can they not engage sailors at twelve dollars a month? What is become of Commodore Perry? What is the administration waiting for?”40 But Fillmore’s administration, sadly for Perry, had found that the same election posturing that had given Mason a pulpit in the Senate had also monopolized the energies of the Whig Party as they prepared for their upcoming National Convention, a situation that became especially acute after Secretary of the Navy William Graham resigned to run as Winfield Scott’s running mate to replace Fillmore. While this meant that, despite some mild pressure, the expedition managed to stay above electioneering partisan politics, it also meant the expedition was left in limbo. There were, in addition, logistical difficulties. Perry’s plan was predicated on having enough ships, especially steamships, to sufficiently overawe the Japanese. Yet, by July, he had only three on station in Asian waters, two of them sail-powered. Most other American warships were already on duty closer to home. This left two steamers, the USS Mississippi at New York and the USS Princeton (still under construction in Boston), as the only vessels immediately able to join the expedition. Despite the “unpardonable and altogether unnecessary” delays Perry found in its construction, to muster the largest fleet possible he would have to wait for the Princeton’s completion.41

14 But for President Fillmore, Perry’s delay was his boon. As early as 20 July Fillmore had considered the possibility of sending the Mississippi to the fishing grounds if the need arose, a fact he had shared with the British.42 The day after Mason’s outcry in Congress, Fillmore held a conference with his cabinet at the White House to discuss the issue. As newly appointed Secretary of the Navy John P. Kennedy jotted in his diary, all present agreed that “the English interpretation of the treaty seems to be clearly correct; and all that we can complain of is the rather brusque manner in which they have so suddenly determined to enforce their restrictions.”43 On 27 July Fillmore informed Kennedy that it had become necessary to send a ship, and Kennedy’s first official act as naval secretary became writing through the night preparing orders for Perry and the Mississippi.44 Two days later, Fillmore informed Webster that he need not drag himself to the colonies for he had “concluded to send Capt. [sic] Perry with the Mississippi to the fishing grounds to give protection to our fishermen, if any be needed, and to inquire into the whole matter and report here.”45 “I think it was very wise in you to order Commodore Perry down on the fishing-grounds,” a relieved Webster replied. “He will inspire respect, and the promptitude of your action will satisfy the country.”46 On 2 August, with the Mississippi already at sea, President Fillmore sent a letter to Congress informing them of his actions and assuring the Democrats that Perry would ensure the fishermen’s protection.47

15 Laid down in 1839 under the supervision of Perry himself, the Mississippi was one of the oldest and most reliable steamers in the American navy. Having already served as his flagship during the Mexican-American War, Perry had developed quite an attachment to the ship he had once dubbed “a paragon.”48 In 1852 the ship’s new captain, William McCluney, was also an old friend of Perry’s from the Mexican War.49 Another sailor recently signed aboard was the ship’s new purser’s clerk, 16-year-old William Speiden Jr., who would keep a diary of his experiences on the Mississippi from joining the ship in March 1852 through to the Japan expedition, including his journey to the fishing grounds. On 31 July, having received his orders from Secretary Kennedy, Commodore Perry himself boarded the Mississippi and the ship departed New York. A few days later, beginning what would become a common shipboard pastime over the next three years, Speiden wrote what he dubbed “machine poetry” with some of his fellow sailors to help pass the time. Their first stanza ran:

We left New York with our hopes raised high,

to go to the Banks, where playing their pranks,

The Fishermen were for a very long time.50

Catching up with the colonials

16 The Mississippi’s first destination was the most easterly settlement in the United States: the town of Eastport, Maine. There, the ship was to pick up any last-minute instructions before heading on to the fishing grounds, boarding any American fishing vessels they came across and impressing upon their crews the importance of heeding the British authorities and the 1818 Convention. Arriving on 3 August, the Mississippi remained at anchor until the 7th, collecting information about colonial affairs and exchanging pleasantries at parties held by both the British consul and the locals. “Everything indicates a favorable issue,” Perry telegraphed back to Washington. “I shall leave for St. John, New Brunswick tomorrow, fog permitting.” Delayed by the fog until 11:00 in the morning, the Mississippi departed Eastport to arrive at Saint John later that evening.51

17 On 9 August, the Mississippi exchanged salutes with the guns of the city as Perry went ashore to be greeted by an honour guard of the British 72nd Highlanders in full “magnificent costume.”52 Perry then proceeded with two subordinates to Fredericton to meet and dine with the acting governor of the colony, Lieutenant-Colonel Freeman Murray. Discussions revolved around two vessels that had been seized in New Brunswick waters, the Coral and the Hyades, though Perry agreed that they had been breaching the treaty and nothing more could be said. “The interview was most friendly, evincing the absence of all irritation or acrimonious feeling on either side; and everything that was said by me in support of our rights was cheerfully admitted,” Murray reported happily to London.53 Indeed, things had gone so well, Speiden reported, that when Murray and Perry’s men returned to the Mississippi on the 12 August it was with “the English flag flying on our foremast,” and another round of salutes fired off.54 As predicted, Perry had found both sides reconcilable and British “aggression” to have been limited – contrary to Mason’s hyperbole. As Whig Senator William Seward later acknowledged in Congress, “It appears that Commodore Perry found the British authorities adhering practically to our own construction of the convention of 1818.”55 Still, while feting civilians may have encouraged British and colonial goodwill, it still did not actually resolve the fishery question itself. For this, Perry would need to talk with Vice-Admiral Seymour and his Royal Navy officers at Halifax.

18 On 13 August, the Mississippi took on a pilot and departed for Nova Scotia. After a leisurely voyage, stopping a passing American fisherman and procuring some fresh fish, the Mississippi arrived off Halifax on 15 August. There, Perry found both Seymour’s HMS Cumberland as well as the steamer HMS Basilisk showing the British flag. The following day Perry went ashore for dinner and an initial meeting with Seymour at his private residence, both men finding the other reasonable. In this and subsequent meetings both men discussed the pressing issues of the fishery question; this included the question of which bodies of water in the Gulf of St. Lawrence Americans were excluded from since the 1818 Convention refused their entry to any “bay” within three miles of colonial waters.56 These waters encompassed the prized mackerel grounds of Chaleur Bay, but they also included the seas around Prince Edward Island. Conferring over a map with Perry, Seymour admitted that “In my opinion, the terms of the convention would not admit of the space between the east point and north cape of Prince Edward’s Island being considered a bay from which foreigners may be excluded; and I collected from the Commodore that, as the space it includes is where the American fishermen fish with most advantage, the United States’ Government would most strenuously resist the definition of the term ‘bay’ being applied.” Reciprocity or not, Yankee fishermen were going to continue their fishing off the Island’s shores. Seymour also noted “Commodore Perry . . . admitted that other vessels of war had been in preparation to follow him . . . but the conciliatory spirit of the communications which had passed between us, makes it unlikely that he should encourage more vessels being sent unless any unforeseen event should again arouse the excitable spirit of the United States’ people.”57 Meeting also with Nova Scotia’s Lieutenant-Governor Sir Gaspard Le Marchant, Perry again left a favourable impression; Le Marchant later reported: “I have been given to understand that Commodore Perry has declared himself completely satisfied with the conduct of the Local Government, and that his nation has no ground of complaint against the proceedings of the Colonial authorities.”58

19 The Mississippi remained at Halifax a further three days. More civilians came aboard the steamer and were “very much pleased with everything they saw,” according to Speiden.59 Indeed, the Halifax Chronicle would rhapsodize at length about “this magnificent war steamer” Mississippi and its “gallant Commodore Matthew Perry” in the days after their arrival.60 Meantime, Seymour informed his subordinates of Perry’s itinerary. “The Mississippi is about to sail to-day for the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Bay of Chaleur,” Seymour reported, “where Commodore Perry has expressed his desire Commander Campbell should meet him in the Devastation, which I have directed. I sent for Commander Campbell over from [Pictou] yesterday, while his sloop was coaling, and the Commodore has repeated to me before that officer, the assurance that he shall endeavour, during his progress, to prevent, and not to cause difficulties.”61 With the ground prepared, the Mississippi put to sea on 19 August, closely followed by the Basilisk; Seymour himself had decided to travel to Prince Edward Island to observe the results of Perry’s voyage.

“Yankee Doodle” in the gulf

20 On 22 August, the Basilisk dropped anchor in Charlottetown harbour. Disembarking the following day, Seymour was met on the dock by Governor Bannerman and some of his council.62 Taking time to order the release of the Golden Rule and catch up on events, Seymour then proceeded across the Island by land and rejoined the Basilisk off Richmond Bay on the 26th. He had hoped to meet again with Perry, but the Mississippi had already passed the Island. “The American steam-sloop of war Mississippi, Commodore Perry, was off here, but did not touch at Charlotte Town,” Bannerman later reported, “which I regret, as I could have easily satisfied him of the danger of allowing this question to remain in an unsettled state, and the risks he ran from the landing of so many of his countrymen in direct violation of the law, and without their being under any control.” However, Seymour learned that Commander Campbell and the Devastation had encountered the Mississippi on 25 August off the Island’s north shore as planned.63

21 After leaving Halifax, the Mississippi had passed between the Cape Breton and St. Paul Island on 21 August before entering the Gulf of St. Lawrence to anchor off the Magdalen Islands by nightfall. At daybreak Perry cruised around the archipelago and boarded 11 American fishing vessels, then proceeded westward to Chaleur Bay. After an unfortunate collision while Perry’s men were boarding the schooner Abigail Brown the following day, the Mississippi finally made landfall off the Island of Miscou on 24 August having boarded another 16 American vessels.64 In his report to Washington, Perry noted “These vessels generally had a copy of the treaty on board. They complained, however, of a want of precision in it in reference to the Bays, Inlets, and Indentations of the Land. . . . All seemed anxious to fish inside the Bay of Chaleur. It may be remarked that they all seemed aware of the necessity of compliance with the Treaty with Great Britain, and that if they were caught fishing inside the limits it was at their own responsibility.”65 Perry also noted – diligent promoter of the American navy that he was – that the fisheries provided the United States with an ideal “nursery” for its sailors in times of war and that “the crews of these vessels appear stout, healthy and American.”66

22 On the 25th, the Mississippi proceeded southward along the north shore of Prince Edward Island, stopping that morning to question more fishermen. As Perry had noted in Halifax, this was another major fishing ground for the Americans. Later in the afternoon, according to Commander Campbell’s report, “while standing along shore observed eighteen sail of American fishing-vessels within about two miles of the land, hove-to and apparently fishing. While nearing them, observed the American Commodore coming along shore in the opposite direction.”67 “At about 3 PM,” Speiden reckoned, “we made another fleet, and on our standing for them we saw a steamer come towards us from among them, and shortly thereafter we showed our colors to H.B.M. Steamer Devastation.”68 Campbell, boarding the Mississippi, met with Perry, who reiterated his observation about the American desire to fish in Chaleur Bay. Perry also noted “The Telegraph had detained another vessel called the Golden Rule, but that it was ‘quite right,’ and that he had been told by the other American fishermen that that vessel was taken fishing within the three miles.”69

23 What followed was one of the most contentious events of Perry’s whole voyage. According to Campbell’s account, he then gestured to the 18 American fishing vessels that had crowded around the two warships:

Speiden, however, told a very different story:

This incident was apparently not discussed in Perry’s post-action report, nor was it mentioned in the American press. Given Perry’s similar omissions while in Japan, such actions paint a consistent image of a self-confident officer who always wished to control the narrative and profoundly disliked public scrutiny and criticism.72

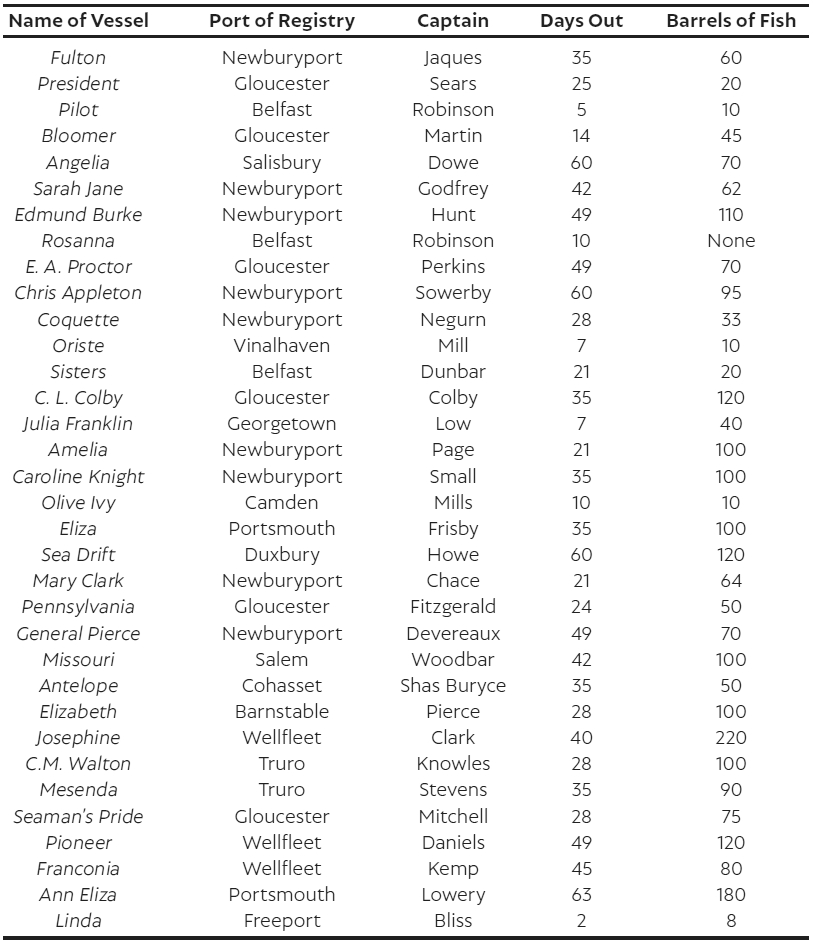

24 According to a list published in the American press after the Mississippi’s return, Perry boarded 34 vessels off Prince Edward Island that day – the most of his cruise. In doing so, his men noted not only the name of the ship in question, but also that of her Captain, her home port, and how many days it had been since they put to sea. They also noted how many barrels of fish had been caught as of their inspection, “thus illustrating the superior skill or industry, or both, of our countrymen in that, as in most every other avocation of pursuit,” as the New York Times opined in their own list (see Table 3).73 This is notable for the fact that one of the ships boarded by the Mississippi, the Caroline Knight, which was captained by Benjamin Small, was later caught blatantly breaching the three-mile limit by the Devastation. The testimony from both the crew of the Devastation and the crew of a passing Nova Scotian fishing schooner was damning and, when asked to justify these actions, the ship’s owner, George W. Knight, argued his case on the dubious grounds of “the almost moral impossibility there exists in ascertaining at all times the exact line or distance from the coast within which the prohibition extends.” Governor Bannerman privately dismissed this position as “so absurd a plea in justification” as he had ever heard.74 While Bannerman speculated that this was likely a legal ploy cooked up by the ship’s owners to avoid blame, it is possible that Perry’s stunt in playing “Yankee Doodle” had led Captain Small and his crew to believe that they had the tacit support of the American government behind them and thus encouraged a more assertive stance.75 Regardless, having seen to the fishermen and met with the British authorities, the Mississippi’s mission was complete, and the ship plotted a return course for New York.

Display large image of Table 3

Display large image of Table 3Conclusion

25 On 1 September, the Mississippi concluded its tour 32 days after first setting out. Upon receiving word, the Weekly National Intelligencer was quick to voice the government’s approval: “Commodore Perry, by his tact and address, has done much to increase the amity and good feeling which should exist between the [British] Provinces and ourselves. . . . The fishing question presents no difficulties which cannot be arranged by the present Administration.”76 Ambassador Crampton, writing from Washington, was able to tell his government that two American warships, which had been retained pending Perry’s return, had been allowed to proceed with their original missions, a clear sign of a return to business as usual.77 As for President Fillmore, he was apparently satisfied at the outcome as he personally read Perry’s report on his mission before returning it to Secretary Kennedy for filing.78 As Fillmore later concluded in his third (and final) annual address as president, “considerable anxiety” had been caused by the summer’s events but affairs had now been settled and he had decided on “a reconsideration of the entire subject of the fisheries on the coasts of the British Provinces, with a view to place them upon a more liberal footing of reciprocal privilege.”79 Reciprocity had been agreed to in principle. The devil, it turned out, was in the details and the affair would not be formally resolved until 1854 with the signing of the Anglo-American Reciprocity Treaty by Fillmore’s Democratic successor, Franklin Pierce. The resulting influx of American capital would finally allow Prince Edward Island to develop its own fishery (employing some 2,300 men and 1,200 boats by 1861), albeit one that remained firmly tied to American apron strings.80

26 As Perry discovered, the fishery question was more the result of frayed nerves and inflamed rhetoric than British aggression or raucous fishermen. While an Anglo-colonial desire to force a resolution to the reciprocity issue was the undeniable catalyst to events, it was not merely an excuse as the colonial authorities had repeatedly made their displeasure at American fishing transgressions known to London well before 1852. Still, while Americans were routinely fishing within the three-mile limit, accounts of wrongdoing ashore were often exaggerated and the British were inclined to be lenient, as the Golden Rule incident highlights. Nevertheless, this apparently anticlimactic end to the fishery question should not blind us to the real constraints under which both the Americans and the Anglo-colonials were operating. There was plenty of pressure, for instance, on administrators from both sides to force the issue. Prime Minister Derby, while convinced the Americans would negotiate over the fisheries, still worried what would happen to the BNA colonies should the worst happen. “We have a long and undefended frontier, and I cannot but fear that recent events have greatly shaken the loyalty, most especially of the West Canadians, the first to be invaded and the first to be succoured.”81 Indeed, by 1852 British strength in North America was weak and comprised only a little more than 7,000 regulars while the Royal Navy was simultaneously decommissioning three steam sloops serving on the Great Lakes.82 Many Americans also saw the potential for war. “The excitement over the fishery question was then at fever heat,” one American account later observed. “Mutterings of war were already heard in the newspapers. Employment for the Mexican veterans [of the 1846-1848 war] seemed promising.”83 To discount such views as exaggerated is to miss the point. The fact that prompt action was seen as necessary by both the British and the Americans is explained by their recognition that any dispute over the fisheries could spiral out of control if left unchecked. Both sides thus chose to de-escalate.

27 In retrospect, the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 was only a single volley in a series of disputes between the Anglo-colonials (later Canadians) and the Americans over the fisheries that paralleled the equally fractious diplomatic relations between them. Reciprocity itself would be abrogated by the Americans in 1866 as punishment for British sympathy towards the Confederacy during the Civil War. The issue would be again raised during talks over the Treaty of Washington in 1871 and would flare up again during the 1880s and around 1910, when the issue was finally arbitrated at The Hague.84 Yet despite these irritants, there was no renewed Anglo-American conflict, and one reason for this can be seen in the events of 1852. In short, there was a broad consensus on both sides to avoid war – one that stretched from high administrators down to many average civilians.85 From the sober calculations by men like Bannerman and Fillmore, to the cordial meetings between Seymour and Perry, down to Lieutenant Chetwynd’s interactions with Israel Bartlett and the thousands of other peaceful interactions between Prince Edward Islanders and the American fishermen, there were few points where problems could arise and this set a pattern for the years to come. Most officials at the top did not want to rock the boat, while among the fishermen, as Brian Payne has noted, those of both nations often developed informal codes of conduct to smooth over relations at an individual level.86 The result was that despite formal disputes, both nations’ policy makers remained conciliatory while ordinary citizens often voted with their feet for better relations (sometimes literally). By the 1890s, when the socalled Venezuela dispute was rankling British-American relations, many were again becoming alarmed at the possibility of war. Yet, as Richard Preston notes in a telling anecdote, cross-border socializing between Canadian and American soldiers continued throughout the incident, as when the US Army and Navy Journal cheerfully reported that among the guests attending a reception at the barracks in Sackets Harbor, New York, were “delightful officers from the barracks at Kingston [Ontario].”87 Well before President Cleveland’s rhetoric over Venezuela the 1890s, the threat of war for political gain pushed by men like Senator Mason in 1852 was struggling to remain politically relevant.88

28 As for Commodore Perry, his voyage also had its benefits. While conferring with Seymour at Halifax, Perry had inquired whether the British could send along copies of their maps on Asian waters to aid his Japan expedition. On Seymour’s behalf the Admiralty duly sent “four books and eighty sheets of charts, of the latest publications, all descriptive of the parts of the world to which I am bound,” much to the commodore’s delight.89 But Perry returned to find his hopes for a quick departure dashed. Leaving New York in the Mississippi on 23 October for Annapolis where the Princeton had finally been completed, Perry’s new steamship travelled only as far as Norfolk before its engines failed and were found to be defective. “Finding that unless I sailed alone . . . I might be detained several months longer,” a furious Perry later wrote, “I determined . . . to proceed with the steamer Mississippi without further delay.” On 24 November Perry departed Norfolk alone, finally bound for Japan.90

29 It is also worth reflecting on how Perry’s actions compare with those he later took while in Japan. Indeed, the context of both missions – a naval expedition to press for the rights of American sailors (whalers in Japan; mackerel fishermen in the BNA colonies), which relied on both impressing local officials and making a show of American resolve – are both broadly similar. First, there is the “Yankee Doodle incident.” In Japan Perry “orchestrated ceremonies of American power in the form of spectacular parades and cultural presentations,” as Jeffery A. Keith has argued.91 While not attempting to overawe the colonials with American superiority, off Prince Edward Island Perry still let the band of the Mississippi play “Yankee Doodle” (with its Revolutionary War-era, anti-British overtones) even while publicly and repeatedly admitting that Anglo-colonial criticisms were indeed valid. Perry’s likely intent was to try and cheer his “stout, healthy and American” fishermen-cum-navy-reservists despite having to officially reprimand them. But in context, even Speiden wrongly read the Devastation ’sdeparture as a sign of British retreat and later reflection convinced him that “the English there have fishing grounds which they do not make use of themselves and are unwilling that others should use them. Our fishermen who are industrious and enterprising, thinking that that was not the right way to act, intruded on their grounds,” concluding that the British were the real instigators.92 As seen throughout this article, this was hardly a fringe view among Americans.93 This was, in many ways, the same contemporary rationale being used by the US government in such disparate instances as the US cheating Native Americans of their land as well as why Americans believed that Japan needed to be “opened” by American naval power. As one American editorialist phrased it in 1852, “The same law of civilization that has compelled the red men of our forests to retire before the superior hardihood of our pioneers will require the people of the Japanese empire to abandon their Algerine cruelty.”94 This argument’s use against the BNA colonialists and their governments, however, who were arguably no less “enterprising” or “civilized” in national self-perception than their southern neighbours, deserves comment.

30 The above facts demonstrate that American chauvinism during this era was not entirely based on racism. While racism – most visibly expressed in the Antebellum American acceptance of slavery – was undeniable, Americans’ sense of their own civilizational superiority could be clearly articulated against the most “civilized” of its fellow neighbours. Indeed, these sentiments are likely better explained by the American belief in their own progressiveness and preordained greatness, which found root in the idea of Manifest Destiny. While Fillmore and his Whigs remained wary of uninhibited territorial expansion, many other Americans were not so restrained.95 “By the mid-nineteenth century,” as Keith again notes in the context of Japan, “Americans assumed their star was rising as Europe succumbed to decadence. And, in this spirit, Perry as well as his crew conceived of their mission as an opportunity to advance American civilization further westward.” Much as Perry later ordered the Mississippi’s band to blare “Hail, Columbia” for his initial landing in Japan, this same band’s rendition of “Yankee Doodle” in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and indeed the controversy over the fisheries itself, can be understood as the posturing of an up-and-coming nation that “staked its cultural identity to, and developed its foreign policies from, [both] a dangerously racist and staunchly chauvinistic worldview.”96

31 It is also tantalizing to consider what impact Perry’s voyage had on his later conduct. Did Perry’s experiences in the BNA colonies, in other words, inform his later actions in Japan? This is a difficult question to answer, but there are points worth considering. Firstly, the American government was clearly satisfied with Perry’s diplomacy, though it remains an open question if knowledge of the “Yankee Doodle” incident would have raised eyebrows. As the official version of his Japanese voyage contained in the Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan (fastidiously compiled under Perry’s direct authority97) later stated, despite delays, “the Commodore was not idle” as he had been “ordered to repair in [the Mississippi] to the fishing grounds, and assist in amicably adjusting the respective rights of the English and American fishermen,” and that he “performed this duty satisfactorily to the government.”98 Perry thus chalked up his voyage as another diplomatic success, perhaps serving as a vote of confidence in his ambassadorial skills where his plans for Japan were concerned.99

32 Finally, it is worth comparing this earlier voyage to the Japan expedition regarding their local receptions. As shown, the Anglo-colonials praised the conduct of Perry and his men in every port they visited, with the “gallant Commodore” and his “magnificent” warship lauded by government officials and civilians alike. Flattery and stock rhetoric no doubt played its part in this. But the seemingly gratuitous focus in nearly all accounts on the gun salutes given, on the flying of the opposite nation’s flags, on references to personal “tact” and “gallantry” by those officers present, and even the angry appeals from Senator Mason for “comity” and “national courtesy” arise from 19th century conceptions of honour and civility. With this pomp and circumstance, men on both sides were signalling their mutual respect and openness by acting according to well-established rituals known to both the Americans and the Anglo-colonials due to their shared cultural heritage. Following these unspoken rules, the colonials sought to make Perry’s arrival a magnanimous one. “Indeed we feel assured that on the part of the members of the Government, and that of the community at large, there was every desire manifested to render [the Mississippi’s] visit agreeable,” as one New Brunswick newspaper openly asserted after the ship’s visit to Saint John.100 While Japan’s isolation prior to Perry’s arrival can be exaggerated, Japanese leaders in 1853-1854 were truthfully ignorant of many Western social conventions and through the application of their so-called “seclusion” (sakoku) edicts were – at least as far as Perry and other Americans could reason – merely acting deceptively and in blatant opposition to “proper etiquette.”101 Given the curt rebuff to a previous American attempt to open Japan by Commodore James Biddle in 1846, Perry knew that any attempt to establish an open dialogue with high-ranking Japanese officials, similar to the one he had established with Vice-Admiral Seymour in 1852, was impossible and a forceful demonstration of American determination and hospitality was thus required.102 When Perry did eventually land in Japan, it was with the same combination of dress uniforms, gun salutes, musical renditions, and military pageantry that he had employed and been met with in the BNA colonies. But what were, for the visiting surveyor Henry Bayfield, “the usual salutes” exchanged between the Mississippi, the Cumberland, and the Citadel upon Perry’s arrival in Halifax were, for Japanese witnessing Perry’s landing, an alien display that “caused some little stir among the Japanese troops, who did not seem exactly to understand it.”103 If Anglo-American cultural affinities had helped ease the fishery question and reaffirm for Perry how “civilized” and open nations were supposed to act, then the antithetical reactions of the Japanese merely demonstrated their inferiority to Perry and justified his adversarial response in attempting to “educate” them.