Articles

The Life and Times of the Nova Scotia Cricket League, 1906–1914

Cet article examine l’expérience éphémère mais révélatrice de la Nova Scotia Cricket League (NSCL) et montre que le cricket était un sport complexe et profondément enraciné chez les colons en Nouvelle-Écosse avant 1914. Même si au 19e siècle le cricket dans la province avait été pratiqué dans des cadres sociaux largement coupés les uns des autres – par l’élite et les militaires, des clubs dans les régions rurales et les petites villes ou des équipes de travailleurs des mines de charbon – la NSCL représenta un effort visant à amener une plus grande intégration du sport. Des joueurs de diverses conditions sociales partageaient régulièrement la surface de jeu. Malgré le déclin que le cricket finit par connaître dans la région, la NSCL a fourni pendant quelque temps un lieu où s’accordaient les différences sociales.

This article examines the short but indicative lifespan of the Nova Scotia Cricket League (NSCL), showing that in Nova Scotia prior to 1914 cricket was a complex and deeply rooted settler sport. Although 19th-century cricket in the province had developed in largely disconnected social frameworks – elite and military cricket, rural and small town clubs, and working class teams on the coalfields – the NSCL represented an effort to bring about greater integration. Players from diverse social backgrounds routinely shared the playing surface. Despite cricket’s eventual decline in the region, for a time the NSCL provided a venue for the negotiation of social differences.

1 As a global sport, cricket is complex in both its history and its historiography. It is a truism of sport history that every human society is characterized by its own particular patterns of physical recreation – as holds true also for such other social and cultural phenomena as education and religion – and therefore that the study of sport offers sensitive insights into the dynamics of social interaction. The construction of socio-cultural solidarities and the negotiation of socio-cultural differences, including those bearing on class, race, and gender, have proceeded through sport in multiple and immensely diverse contexts. Where empire and (in some parts of the world) its settler colonial manifestations have been involved, these can become powerful cross-cutting historiographical themes as the study of cricket has abundantly demonstrated.

2 Numerous historians have examined the varied social roles of cricket in imperial Britain.1 Cricket in the longstanding settler colonial fabric of the United States has been treated by historians such as George B. Kirsch, Tom Melville, and Jayesh Patel.2 Richard Cashman and others have explored the testing of barriers of social class through cricket in Australia.3 Essays collected by Bruce Murray and Goolam Vahed have positioned the development of South African cricket in an imperial context.4 Caribbean cricket was the subject of C.L.R. James’s Beyond a Boundary – uniquely influential as a work of sport history but also a profound meditation on race and empire in the West Indies and beyond – while the Barbadian historian Aviston Downes has more recently provided innovative interpretations of the imperial and gendered dimensions of cricket in that region.5 The growing historiography of cricket in India includes most prominently the wide-ranging study by Ramachandra Guha, A Corner of a Foreign Field, portraying a sport that could become a focus of resistance to caste discrimination and yet could also channel volatile religious tensions.6 Along with studies that have dealt interpretively with the global diffusion of cricket, such as that of Jason Kaufman and Orlando Patterson, cricket as a multi-dimensional sport has thus received extensive and internationalized historiographical attention.7

3 Taken together, the strands of this complex literature illustrate the profound social and cultural variations found within a single sport. Cricket, from its origins as an English vernacular pastime of the early modern era that was initially exported primarily to North American colonies, evolved during the 18th century as an organized sport that was diffused on an imperial scale both to settler colonial societies and to areas such as India and the Caribbean where players of British origin eventually formed a minority and where the sport could become a vehicle of anti-colonialism. Even when comparing settler colonial contexts, diffusion had distinctive results not only in the degree to which the sport reinforced settler colonialism itself but also in its influence on the entrenchment or surmounting of social barriers within settler society. Yet despite the variety and sophistication of the international historiography on cricket, historical writing on cricket in Canada has traditionally had limitations in scope and has lacked any significant emphasis on social diversity. The guiding assumptions have been that cricket was essentially a sport for a mainly homogeneous minority consisting primarily of upper-class recent migrants from England (or, in some cases, those who would have liked to be English and upper class, and had affectations to match) as well as military and naval officers belonging to imperial forces.8 Taking the specific case of Nova Scotia, where evidence of organized cricket dates to the 1780s, this article argues that cricket was a deeply rooted settler colonial sport and that the social diversity of the participants made it also an important venue for the negotiation of differences based on social class and race/ethnicity.

4 Both for Nova Scotia and for Canada as a whole, a limiting factor on cricket historiography has arisen from the implicit biases that were integral to certain major primary sources. Especially influential was the voluminous 1895 documentary collection of John E. Hall and R.O. McCulloch, Sixty Years of Canadian Cricket, which concentrated on leading clubs and international tours while attributing an elite character to cricket wherever it was played in Canada (including in Halifax).9 The American Cricketer magazine, meanwhile, faithfully covered upscale cricket clubs in major Canadian urban centres, especially when they played similar teams from the United States – meaning that the repeated encounters in which the Halifax Wanderers and Garrison clubs faced opponents from Philadelphia received thorough treatment. It was true that on one occasion in 1906 the largely working class Stellarton Cricket Club was favourably written up by a Stellarton physician who was also a member of the team. Also, an article was authored in the following year by a player from the Garrison club, who selected a notional Nova Scotia team and not only named an African Nova Scotian as captain (the Africville schoolteacher Mowbray Fitzgerald Jemmott, of the Halifax Caribbeans) but also included a professional player (Henry G. Davy, of the Wanderers) whose day job was as a milkman.10 Despite these hints of a broader reality, however, a historian relying unduly on the American Cricketer would inevitably receive a view of Nova Scotia cricket that focused disproportionately on its urban and socially elitist facets. Detailed analysis, by contrast, reveals the more complex reality of a settler sport in which participants of widely varied social backgrounds shared the playing surface, even though sometimes uneasily.11 In particular, the short but indicative lifespan of the Nova Scotia Cricket League (NSCL) exemplifies the diversity and continuing evolution that characterized cricket as a Nova Scotian sport during the period up until 1914.

5 In its 19th-century forms, Nova Scotia cricket can be divided into three main categories. One of these was Halifax cricket, consisting primarily of clubs composed of players drawn from the city’s professional and commercial middle and upper classes (from 1882, pre-eminently the Wanderers) along with the Garrison club and the military and naval teams that were associated with it. In social terms there were complexities, notably in that the Garrison club included among its players non-commissioned officers as well as rank and file so that it was no mere coterie of officers. And yet it was here in Halifax – and to a lesser degree in the Sydney Cricket Club – that cricket came the closest to resembling the simplistic model of being a military and upper-class sport. Even so, the non-military Halifax cricketers were drawn primarily from established settler families rather than from recent English migrants. The second category consisted of rural and small-town cricket clubs distributed throughout the province, in which teams would characteristically include some members of highly localized social elites but would be represented mainly by skilled artisans, small-scale merchants, and others from the middling ranges of society.12 Thirdly, predominantly working-class cricket developed strongly from the mid-19th century on the three Nova Scotia coalfields and expanded over time to include other industrial workers.13 While the three forms of cricket bequeathed by the 19th century were never entirely separate from one another, notably in that the Wanderers made periodic tours of the province and would play against local clubs, nevertheless the contacts among them were sporadic and unsystematic. The Nova Scotia Cricket League, during its years of existence from 1906 to 1914, was the first serious effort to bring them together. Not only did it thus offer an entirely new opportunity to establish cricket as a sport within which social differences could be negotiated, but also, in its extension to clubs that included the Halifax Caribbeans and later the Whitney Pier Cricket Club, it brought teams composed of players of African descent into the position of forming a further category of cricketing in the province.

6 In a longer-term sense, the origins of cricket in Nova Scotia – and elsewhere in the Maritime colonies – are difficult to establish with any precision. In October 1786, a Halifax cricket team drawn from the “Dock Yard and Town” published a newspaper challenge to potential opponents from the army and navy.14 The establishment of formal cricket clubs in Halifax was under way by the 1840s.15 It is likely, however, that the sport had multiple origins and that one of them was the vernacular sport of “wicket,” which was current in the New England colonies from which many of Nova Scotia’s 18th-century settlers originated.16 Other migration streams came from the British Isles while British military and naval influences also persisted, notably in Halifax itself. The diversity of early influences notwithstanding, the mid-19th century saw cricket in its then-modern form to be characteristic of the sport throughout the province. The 1858 rule book of the club then known as the Halifax Cricket Club, for example, specified – along with such arcane rules as providing an elaborate process for “getting rid of an obnoxious member” – that the latest edition of the laws of the sport as prescribed by the global governing body the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) would be decisive in resolving all disputes.17 Overarm bowling, legalized by MCC in 1864, quickly came to prevail, even though underarm bowling – in Nova Scotia as globally – continued to be permissible and was seen in some matches.18 In general, the scoring details that began to be published in mid-century in newspapers province-wide read interchangeably with those in any other part of the cricket world.

7 Yet if the form of the sport was global, most Nova Scotia cricket at this time was essentially local. Many of the matches played were between teams drawn from within a single club, most commonly between married and single players but also extending to many other arbitrary and inventive distinctions; among clubs consisting primarily of mineworkers, for instance, there were a number of variations of teams representing underground versus above-ground workers. Games were also played between rival clubs, although still locally in most cases either within towns and villages or pitting one neighbouring community against another. The exceptions were found in occasional matches that involved socially elite teams from the main urban centres of the Maritimes. In August 1869, for example, the Halifax Phoenix Cricket Club received a visit from the Fredericton Cricket Club, accompanied by its president who also held the political role of provincial secretary of New Brunswick.19 Other matches might also involve travelling, but still within the confines of localized, often waterborne, transportation. The Springhill team, the most durable working-class team in Cumberland County, would play its matches not only with the nearby town club in Amherst but also with the Windsor Cricket Club – which, despite having some associations with King’s College, retained the character of a traditional town club – at the geographical mid-point in Parrsboro.20 Railway development eventually allowed for faster and longer-distance travel, but even to the end of the 19th century and beyond most cricket remained essentially local. As such, it could generate such fierce rivalries as those between Digby and Annapolis Royal and between Stellarton and Westville; but in settler society it also had an important role in facilitating social relationships among adjoining towns and villages.21

8 During the later decades of the 19th century, the Wanderers emerged as the principal exception to this localized pattern. As well as its provincial and regional tours, the club quickly made its way into the international world of cricket and not only in terms of matches and tournaments with opponents from Philadelphia and other US centres. In 1886, the club participated in a tournament in Montreal during which it met defeat against the first West Indian touring side – an all-white team assembled from Barbados, British Guiana, and Jamaica – despite stubborn resistance from the Halifax lawyer William Alexander Henry.22 As an individual, Henry was a member of a number of Canadian international teams, and headed the batting average when he was one of two Wanderers players who in 1887 joined the “Canadian Gentlemen” in the most extensive cricket tour of Great Britain by any team representing Canada.23 As late as in 1904, aged 41 and far beyond the peak of his career, Henry came close to a Canadian record by scoring 225 runs for the Wanderers in a single innings against the Garrison club.24 Nevertheless, viewed from a different perspective, this match exemplified the stale patterns into which Halifax cricket had fallen. The Wanderers continued to draw international recognition and, within Nova Scotia, even a degree of deference. When a match was proposed in 1892 between Digby and the Wanderers, the Digby Weekly Courier noted that “of course it can hardly be expected that Digby can defeat a team with such a record as that of the Wanderers.”25 And more than a decade later, when a combined Pictou County team was defeated by the Wanderers, the report in the Morning Chronicle carried the subheading, “Pictou County Cricketers Made a Great Showing Against the Wanderers.”26

9 As the ensuing 1905 season opened, however, the Halifax Daily Echo reported on a serious lack of opponents for the Wanderers, owing to uncertainty (for unspecified reasons) as to whether the Garrison club would be able to field a team.27 Match after match with the Garrison had characterized recent seasons for the Wanderers, together with occasional matches with naval and United Services teams, or with visitors from New Brunswick and the United States, that were often arranged at short notice. A commentator in the Evening Mail a year later put the matter bluntly. While noting that public interest in cricket was noticeably increasing – a point confirmed elsewhere in the province – and that “more than ever before youngsters may anywhere be seen swinging their bats, and nearly every local school has its eleven,” the writer was scathing about the state of club cricket, but also had a proposal:

10 The proposal soon brought results, although not quite in the form that the writer had originally put forward. In late June 1906 the Evening Mail reported beneath a large front-page headline that, rather than a Halifax league, a provincial league would be formed, with four teams participating in the first season. Three – the Caribbeans, the Garrison, and the Wanderers – would be from Halifax, and the fourth was to be the Windsor club. By the end of the season, after the Wanderers had won the championship, the Evening Mail was congratulating the NSCL on its success: “Great interest has been shown in these games and the league seems to have revived cricket locally.”29 Yet there remained good reason to question how much had really changed. The precedents for league cricket were, as ever in cricket, partly international. In the northern English counties of Lancashire and Yorkshire, in parts of Australia, and in Massachusetts, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the establishment of cricket leagues that took advantage of the five-and-ahalf-day work week to provide opportunities for amateur or semi-professional players of non-elite social origins. Nearer to home the closely related sport of baseball had experimented with leagues from the early 1890s onwards in both New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, though with decidedly mixed results in terms of success and sustainability.30 The most immediate precedent for the NSCL, however, had originated in Pictou County, where the first county cricket league had begun in 1897 with teams from Albion Mines, New Glasgow, Stellarton, Thorburn, and Westville.31 The initial aspiration that the league would “help to make a kindlier feeling among the different towns of the county” went unrealized, as the seasons of the early 20th century yielded an increasingly violent animosity between Stellarton and Westville; but as early as during the first season, a match between Albion Mines and Westville drew a substantial crowd of 600 spectators.32 The early NSCL, on the other hand, had undoubtedly aroused interest in Halifax and Windsor, but in reality it had been contested by clubs that had often in the past played matches against one another. And while the league had no doubt made these encounters more purposeful, it had provided little that was genuinely new – save for the emergence of both Jemmott (primarily as a bowler) and Davy (primarily with the bat) as outstanding players of the generation following the retirements of Henry and others of the original Wanderers, equalled only perhaps by the all-round player Frederick Handsombody of Windsor. As the headmaster of King’s Collegiate School, Handsombody was a rare example of a Nova Scotia cricketer who actually did fit the profile of being an English immigrant of a gentlemanly sort.33

11 The second season of the NSCL, however, not only introduced a further outstanding player in the person of the Westville bookkeeper Harry Saunders but also brought about a more fundamental change in establishing the clear supremacy of working class Pictou County cricket over all competitors, the Wanderers included. Tight, disciplined, and using (insofar as reported in newspaper team lists) only 14 active players in their three championship seasons from 1907 to 1909, Westville swept through the league with apparent ease. The local correspondent of the Pictou Colonial Standard captured the moment after Westville had inflicted a heavy defeat on Windsor in late July 1907 by anticipating correctly that “the Provincial championship will leave the citadel for the little mining town in Pictou County, the home of cricket.”34 During the 1908 season Stellarton also joined the NSCL – having declined to do so for financial reasons in 1907 – and so resumed the old Pictou rivalry with Westville, but with little success. When Westville again went undefeated, the Halifax Morning Chronicle allowed that “Westville deserves great credit and there is no disputing their title. They excel the other teams in the League in every way; they field better, their bowling is much superior, and their batting is far ahead of any other of their opponents.” More generally, the newspaper added “When the Nova Scotia League was founded the grand old game received a new lease of life in Halifax, and now the game has more followers than ever before.”35 The 1909 season showed little change, when Westville again prevailed, despite conceding their first and only defeat in the league in an end-of-season game against the Garrison.36

12 Westville’s failure to enter for the league in 1910 undoubtedly had a connection with the decamping of Saunders and another high-quality player, Alex Jamieson, to the Stellarton club. What was cause and what was effect is not clear from surviving evidence, but the Westville community was offended according to the Colonial Standard and the correspondent of the Westville Free Lance was not entirely convincing in the assertion that “Harry is a star Cricketer and Westville was sorry (not sore) about loosing [sic] a good bowler and batter . . . . The Standard man don’t need to take the matter to heart as Harry is still popular here.”37 In any event, the result was to extend the ascendancy of Pictou County cricket, as Stellarton won successive NSCL championships in 1910 and 1911. A reporter in the Halifax Herald expressed surprise in September 1910 that Stellarton had prevailed over the favoured Garrison club, which supposedly had “a far larger field to pick players from than any of the other clubs, and also far more time to practise. They play cricket at times, that stamps them as easily the best in the league, then they flunk it.”38 A year later, no surprise was expressed when Stellarton again defeated the Garrison in the final and deciding match of the season, with Saunders scoring 81 runs as well as taking wickets as a bowler.39

13 By now, the composition of the league had changed substantially. Windsor and the Caribbeans had dropped out after the 1907 season, Windsor having found it impossible to compete effectively. The Caribbeans continued to exist as a club, under varying names, and would re-enter the league in 1914 as the Halifax West Indians. A major addition in 1910 was the entry of the Sydney Cricket Club to the league. Only two subsequent additions would be made: the Truro club played one unsuccessful season in 1912, while the Whitney Pier Cricket Club – composed primarily of African-descended steelworkers of Caribbean origin – would participate in the war-shortened season of 1914. The Sydney Cricket Club, which was well known historically as an elite club in social terms, had, since the opening of the steel plant at the turn of the 20th century, undergone substantial changes in adding players not only from among white-collar workers at the Dominion Iron and Steel Company (DISCO), but also from steelworkers and those in related industrial occupations. Entry into the NSCL accelerated this process, as the club then co-opted Africandescended steelworkers who had brought their cricket skills from the West Indies, such as William Knight and Alfred Prescott.40 Despite aggressive – some said unscrupulous – competition from the trophy-starved Wanderers, led by the South African professional Arthur Leighton, whose on-field tactics matched his abrasive personality, Sydney won its first NSCL championship in 1912.41 The club had boosterish support on behalf of all “enthusiastic devotees of the grand old national game,” along the lines that “a local sporting team to win in somewhat of a national tournament, provides an excellent publicity theme. It is to the interest of every individual citizen that the Sydney cricketers should win in this season’s Nova Scotia league schedule.”42 Sydney in 1912 were, unexpectedly, the last champions of the NSCL. The 1913 season ended inconclusively, with the Garrison club unable, reportedly “through military duties,” to complete its schedule and thus bring about a final result in the context that all four competing teams – Garrison, Stellarton, Sydney, and Wanderers – were in close contention.43 And in 1914, despite favourable predictions for the NSCL season that highlighted the expansion to six teams through the entry of the Halifax West Indians and Whitney Pier, the league was abandoned a few days after the declaration of war.44

14 Despite the inconclusiveness of its final two seasons, the NSCL had undoubtedly succeeded in fulfilling its goal of entrenching cricket as a major sport for both players and spectators and doing so not only in Halifax but also in other regions of Nova Scotia. In Sydney, for example, the Daily Post commented in June 1914 that “a sign of the times is the interest that is being manifested among the youth of the city in cricket . . . . In all sections of the city the youth are now daily to be seen playing the grand old national game.” And in mid-July, the same newspaper reported the presence of “a large number of citizens” at the opening NSCL match between Sydney and Whitney Pier.45 While membership in the league had fluctuated, and the area of the province covered had extended north from Halifax rather than southwest into the thriving cricket culture of Digby and Yarmouth counties, nevertheless, from the perspective of the sport as a whole, the founding of the Bay of Fundy Cricket League in 1913 – including teams from Digby, Saint John, and Weymouth – had established a potentially effective counterpart to the NSCL.46 Among many war-related developments that were unforeseen in August 1914, however, the First World War marked an end to the prosperity of cricket in Nova Scotia. The sport was still played during the 1920s and 1930s, with a league briefly existing in Cape Breton, while Stellarton and Truro played matches against one another and the Wanderers occasionally entertained visiting military or naval opponents. But cricket was now decisively overshadowed as a summer team sport by baseball to the point that historical memory of the sport continued for the most part to be expressed not in any sense that it had ever existed as a formal activity but rather in children’s street and playground games reaching at least as far forward as the 1960s. Thus for the historian, assessment of the significance of the NSCL must centre not so much on any legacy that it may have created but rather on its socio-cultural significance in its day and – without descending too far into counterfactuality – on the nature of the trajectory that was interrupted in 1914.47

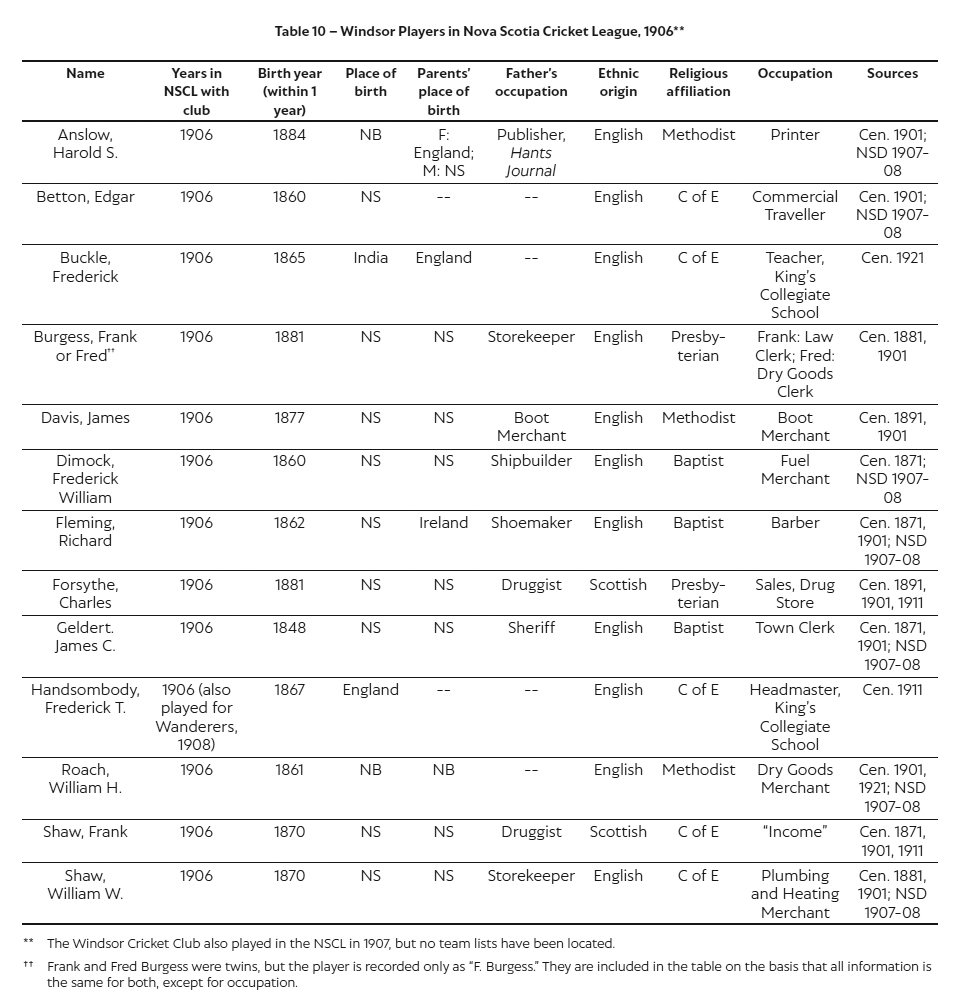

15 Essential to both of these elements is to establish who played in the NSCL and, to whatever extent the sources allow, why they did so. In important respects, the NSCL transformed the sport of cricket in Nova Scotia by intermingling the traditional contexts in which sport had been played as well as by accentuating the influence of African-descended cricketers with Caribbean associations. The NSCL clubs fell into a variety of analytical categories: the traditional town clubs; the traditionally elite clubs that had adapted to the demands of the league; military cricket; working class cricket; and the African-descended, Caribbean-connected cricketers. Undoubtedly the least successful of the teams that participated in the league were the traditional town clubs of Windsor and Truro. Windsor, participating in the NSCL in 1906 and 1907, was a longstanding cricket centre that had been partly sustained through connections with King’s College and its collegiate school but more predominantly was a town club similar to others in the province. The club’s lack of league success came despite the undoubted individual abilities of Frederick Handsombody, as well as Frederick Buckle, who had been born in British India and was now a teacher at the collegiate school. The other team members generally represented the ownership of small local businesses – a coal and wood merchant, a drug store owner, a dry goods merchant, a plumbing and heating contractor, a barber. Almost all of these individuals had been born in Nova Scotia or New Brunswick, although a few of those had one or both parents who had immigrated from the British Isles. The average age was relatively high, although the age of almost 60 years of the town clerk, James Geldert, was exceptional even for the Windsor team. The majority of the players (8 out of the 13 who can be identified) had been born between 1860 and 1870. Although it was unsurprising that almost half of the players gave their religious affiliation as Church of England, nevertheless these were outnumbered by the combined total who were Baptist (3), Methodist (3), or Presbyterian (1). By contrast with most parts of the province, in Windsor no Roman Catholics were reported as playing for the club in the NSCL.48

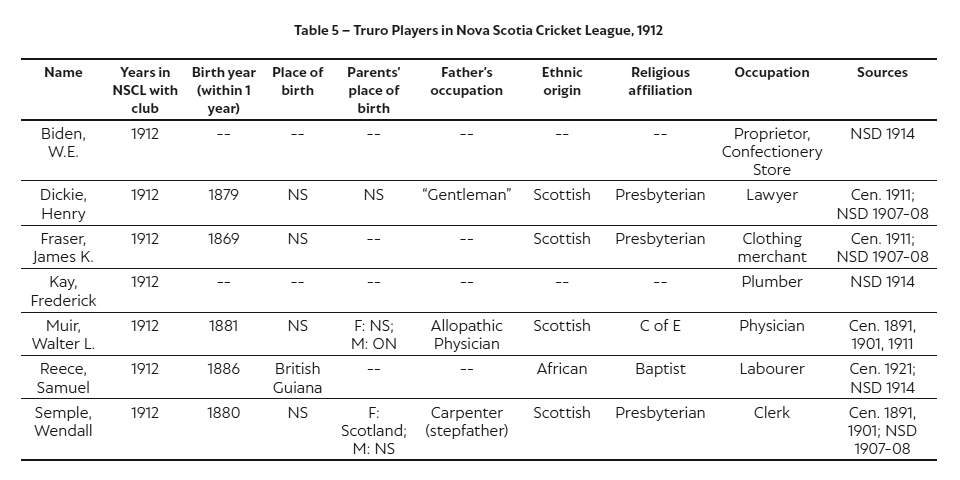

16 There were parallels between that Windsor team of 1906 and 1907 and the Truro club that made a brief and undistinguished appearance in the league in 1912. Truro used 17 players during its only season in the NSCL, but only seven can be identified and of these only two can be attributed full census identification as opposed to the name and occupation derived from the town directories.49 Although the number is too small to support broad generalizations, the team had a number of older players ranging up to the 42 years of the clothing merchant James K. Fraser – a characteristic that (as with Windsor) may help to explain its lack of success in the league. Also similarly to Windsor, there were no listed Roman Catholics. Occupations ranged from a lawyer and a physician to the owners of a confectionery store and a men’s clothing store to a plumber as well as a clerk who was the son of a carpenter, and also Samuel Reece (or Rees). Reece was described as a labourer in a 1914 town directory, but by the time of the 1921 census was declaring that he had his “own shop.” He was exceptional in that he was the only identifiable player not born in Nova Scotia, the only Baptist, and the only player of African descent. An immigrant from British Guiana, he later played a prominent recruiting role in launching the No. 2 Construction Battalion.50 More generally, the diagnostic feature of the many 19th-century town cricket clubs, of which both Windsor and Truro were survivals, was their combination of players from the middling range of society with a minority from a tiny and localized elite, thus facilitating social networks and potential upward mobility. Within reason, age and modest athletic ability did not need to stand in the way of participation – but such a model was ill-equipped to provide the degree of skill and aggression on which success in the NSCL depended.

Display large image of Figure 1

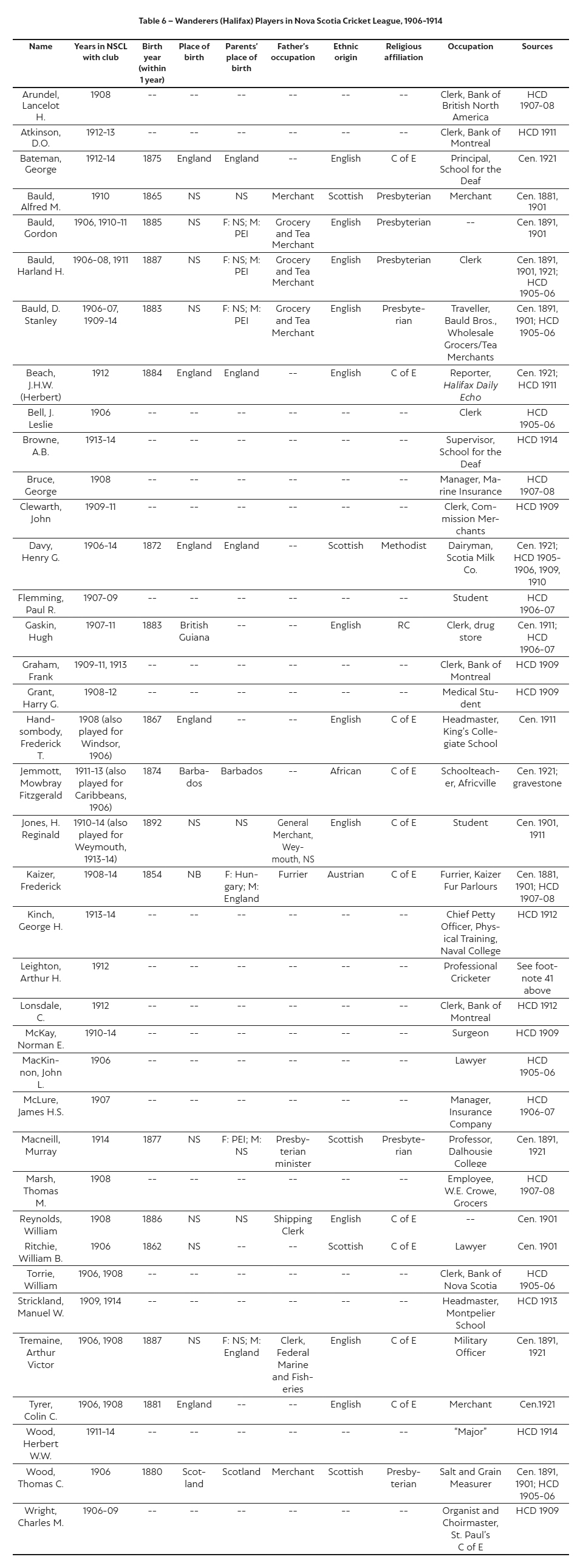

Display large image of Figure 117 Teams that were consistently competitive in the NSCL, but in each case won the championship only once, were those that were traditionally known as elite clubs in a social sense – the Halifax Wanderers and the Sydney Cricket Club. The Wanderers club, as it entered the 20th century, enjoyed a high cricketing reputation based on the prowess of players such as W.A. Henry, but also carried traces of having its origins as a social club for young men who could afford the time not only to play cricket but also to tour extensively with the team. During the years of the NSCL, the demands of touring were much less, as visits to the United States and to other parts of Canada declined, but still noticeable was the tendency of the Wanderers to use many players in a season as members of the club were given the opportunity to play even if they lacked the ability to command a regular place in the team. During the nine seasons of the NSCL, the Wanderers used an average of more than 20 players per season, ranging up to 26 in the 1908 season and 25 in 1911. Certainly there were core players of proven ability such as the veteran Frederick Kaizer (a furrier with the family firm in Halifax, the last of the original Wanderers, and a rarity in being a competent batsman well into his fifties), Stanley Bauld (a commercial traveller on behalf of the family business of grocers and tea merchants), and in the later years of the league the Dalhousie student Reginald Jones, but there were also many others who were more peripheral players but came from the professional sectors of Halifax society (law, medicine, education, Church of England clergy), owners or managers from some commercial companies, and a noticeable representation of bank clerks.51 Names from the genuinely wealthy commercial aristocracy were generally absent, but nevertheless Nancy Kimber MacDonald has found a useful measure of the club’s social composition to be an analysis of the occupational characteristics of members of the club executive. The large majority of these club leaders between 1882 and 1925 were in the top two levels of the scale developed later in the 20th century by the sociologist Bernard Blishen, and more than half were found in Blishen’s Class 2, summarized by MacDonald as having “included some engineers, professors and clergymen; but . . . [mostly] owners or managers of wholesale and retail trade businesses.”52

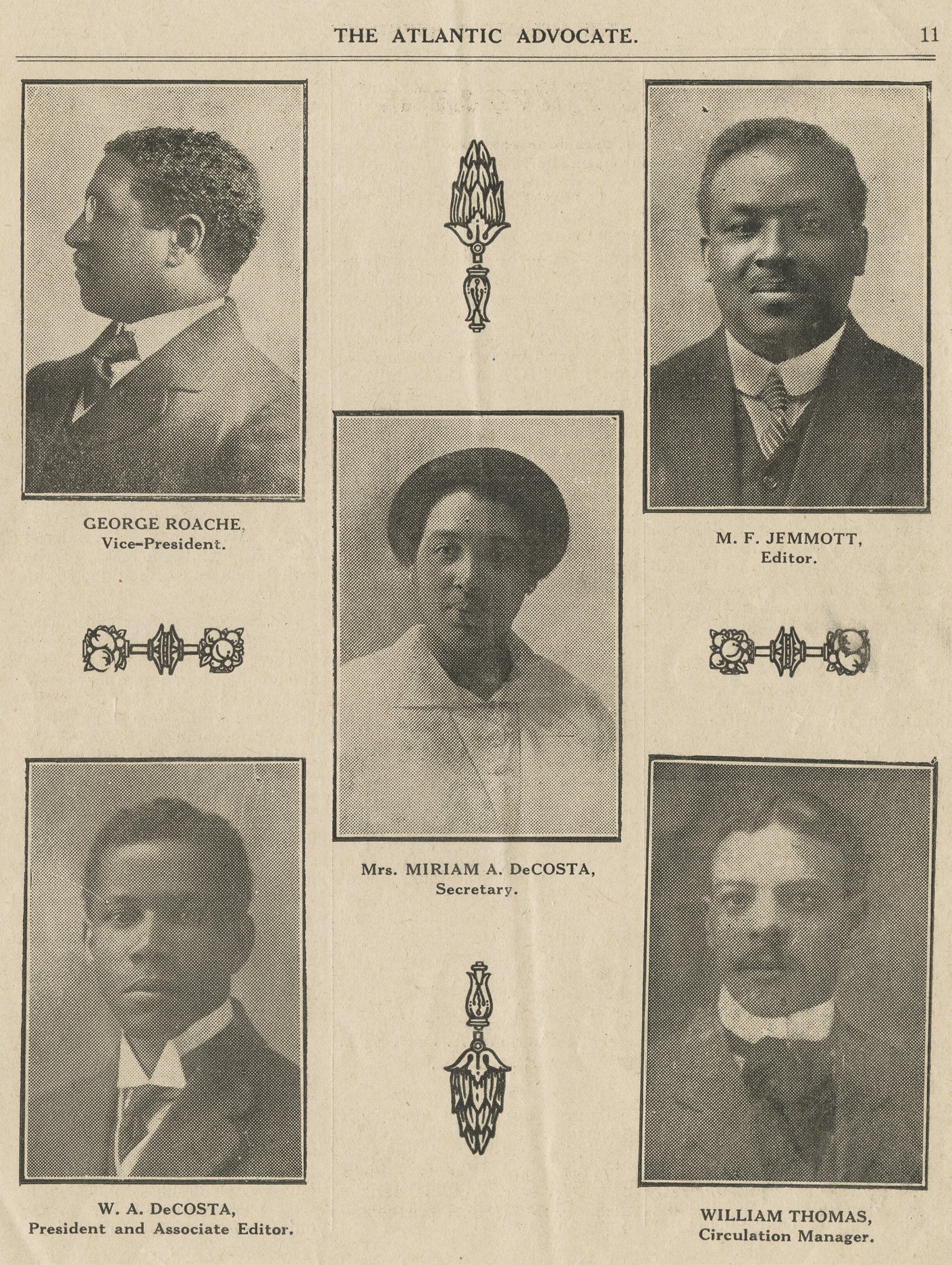

18 Still, the Wanderers did attempt to adapt to the demands of the NSCL through diversification. The club experimented with professionalism – H.G. Davy became a regular and successful player – although other professionals did not last as long with the club and Arthur Leighton in particular left in disgrace after a single season.53 Just as notably, the club resorted to recruitment of certain players who had already played in the league for other teams. Frederick Handsombody joined the ranks of the Wanderers for the 1908 season and a further capture was Mowbray Fitzgerald Jemmott, who played for the Wanderers in 1911 and 1913. Jemmott, like Samuel Reece but primarily in his capacity as an influential schoolteacher, was also connected to the raising of the No. 2 Construction Battalion, and he became in 1915 the first editor of the Atlantic Advocate magazine and thus a prominent spokesperson – to quote the magazine’s subtitle – “devoted to the interests of colored people.”54 Born in Barbados in 1874, he was a rare African-descended player to represent the Wanderers; his addition to the team provides evidence of the club’s determined though ultimately fruitless attempt to rekindle past glories.55

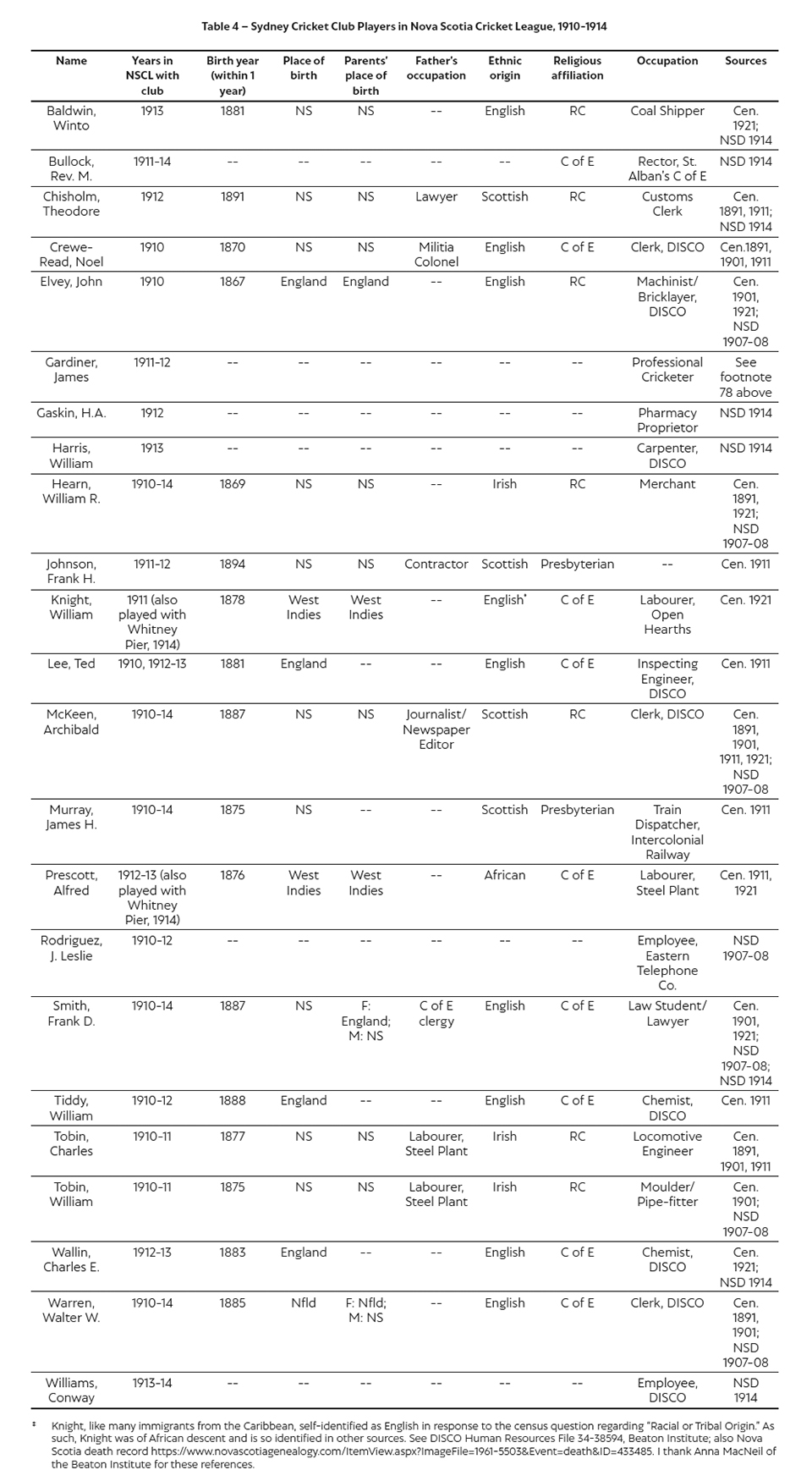

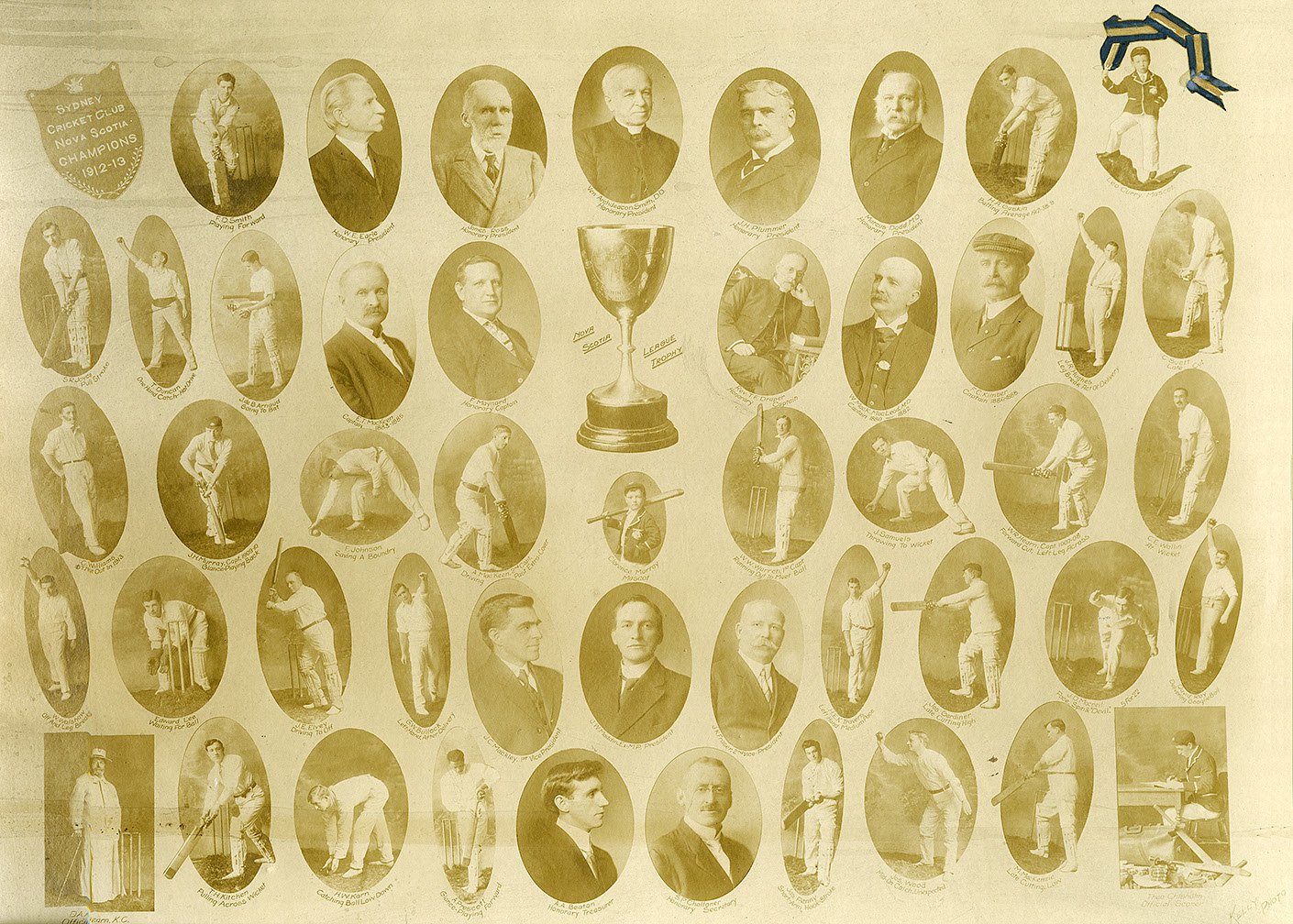

19 The efforts of the Sydney Cricket Club to find success in the league had some parallels with the Wanderers, but were more effective. The club had origins at least as early as in 1863, when its members represented squarely the respectable Protestants of a growing town.56 This characteristic persisted into the league era in players such as William R. Hearn (a merchant and stipendiary magistrate, though also part of an Irish Roman Catholic family), Rev. M. Bullock (rector of St. Alban’s Church of England), the pharmacy owner H.A. Gaskin, and even a young lawyer such as Francis D. Smith. However, soon after the establishment of the steel plant, the club’s players began to show a greater social range. An early example was John Elvey, an English-born machinist who played for the DISCO club, the Open Hearth club, and for the Sydney Cricket Club during its first season in the NSCL in 1910. Also playing for Sydney in 1910 – and also, like Elvey, Roman Catholics – were the Tobin brothers. From a Sydney family in which both parents were Nova Scotia-born (though they had at least one Irish-born grandparent), the younger brother Charles was an accomplished batsman who – as a locomotive fireman and later a locomotive engineer – played also for the Intercolonial Railway team. The older brother William Tobin was a moulder and pipe-fitter who was also a notoriously fast bowler. The Sydney Cricket Club’s dependency on the steel plant continued to be evident throughout its five seasons in the NSCL, whether white collar workers such as Archibald McKeen and William Warren, chemists such as William Tiddy, or working-class employees who included Caribbean immigrants of African descent such as William Knight and Alfred Prescott. Although racial tensions persisted, and eventually the West Indian steelworkers formed their own Whitney Pier Cricket Club, the NSCL had moved the Sydney club away from its traditional composition, even though the more socially elite figures continued to dominate the club executive – whether it was the lawyer and former Member of Parliament James William Maddin as president during the club’s NSCL championship season or honorary presidents such the rival DISCO industrialists James Henry Plummer and James Ross.57

Display large image of Figure 2

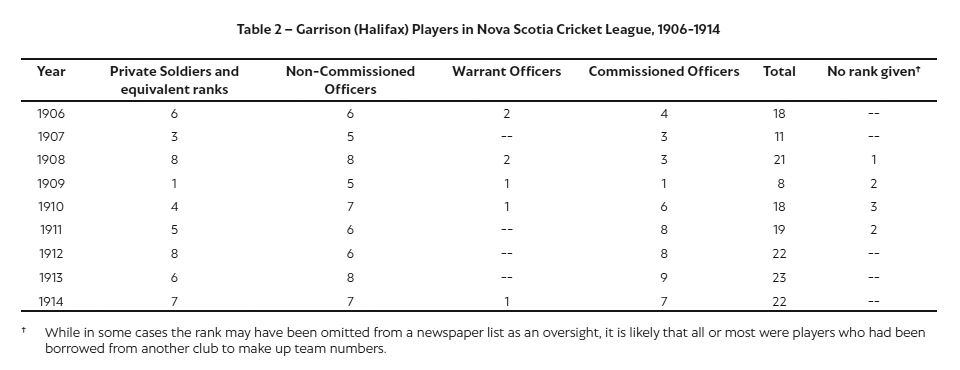

Display large image of Figure 220 Military cricket, as far as the NSCL was concerned, meant the Garrison club. The club itself, however, was a composite, standing at the apex of the complex structure of regimental teams and even the naval team from HMCS Niobe that all made up the Garrison League. Imperial troops had been withdrawn from Halifax in 1906, although the Canadian units that now formed the garrison were composed to a substantial degree of former British soldiers.58 Thus, the cricket culture of the city was unlikely to be weakened, and indeed Corporal W.J. Daplyn, a member of the Garrison team in the 1906 NSCL season and also the inaugural secretary-treasurer of the league, wrote in the American Cricketer in June 1907 that “it was feared that the withdrawal of the imperial forces from Canada would seriously affect cricket in Halifax and district, but, thanks to the enthusiasm of a few of the Garrison Club, last season was most successful, more cricket being played than had been the case for many years.”59 Assessment of the composition of the Garrison team is hindered, however, by the non-appearance in census or directory records of most or all of the participants, although it is clear from newspaper listings that the team was made up of all ranks from private soldier (and equivalents such as gunner or bandsman), through non-commissioned officers, to commissioned officers – depending on the season – ranking as high as colonel. Analysis of Garrison players in the NSCL, in all seasons from 1906 to 1914, shows that the percentage of privates and equivalents averaged 28.2 per cent over the nine seasons (from 12.5 to 38.1). The percentage of non-commissioned officers (including for this purpose warrant officers) averaged 43.0 per cent (from 27.3 to 75.0), while the percentage of officers averaged 28.8 per cent (from 12.5 to 42.1). Thus, while the club was wide-ranging in representing the Halifax garrison, if any group was numerically central it was that of the NCOs such as Daplyn.60

21 Working class cricket in the sense that working class players predominated on any given team – as opposed to the partial integration exemplified by the Sydney Cricket Club – was particular in the NSCL to Pictou County. Teams such as Stellarton and Westville came out of a much larger tradition of cricket on all of the Nova Scotia coalfields, but the trajectories had differed geographically from one county to another. In Cumberland County only the Springhill club had established itself securely, and by the turn of the 20th century its activity had become restricted to occasional games with the increasingly fragile town club in Amherst.61 Thus, cricket had made only an incomplete transition in the county to being a working class sport. In Cape Breton, in addition to the steel works teams that emerged after the establishment of the plant in 1901, the coal towns and villages of the industrial area of the island had by then an extended tradition of playing cricket and by 1907 teams from Bridgeport, Dominion, New Aberdeen, and Sydney Mines were joined with Sydney and North Sydney in a county league that reportedly demonstrated that “local interest in the grand old game of cricket is growing apace.”62 From the point of view of off-island competition, however, the Sydney Cricket Club retained its pre-eminence, co-opting players from other clubs as needed.

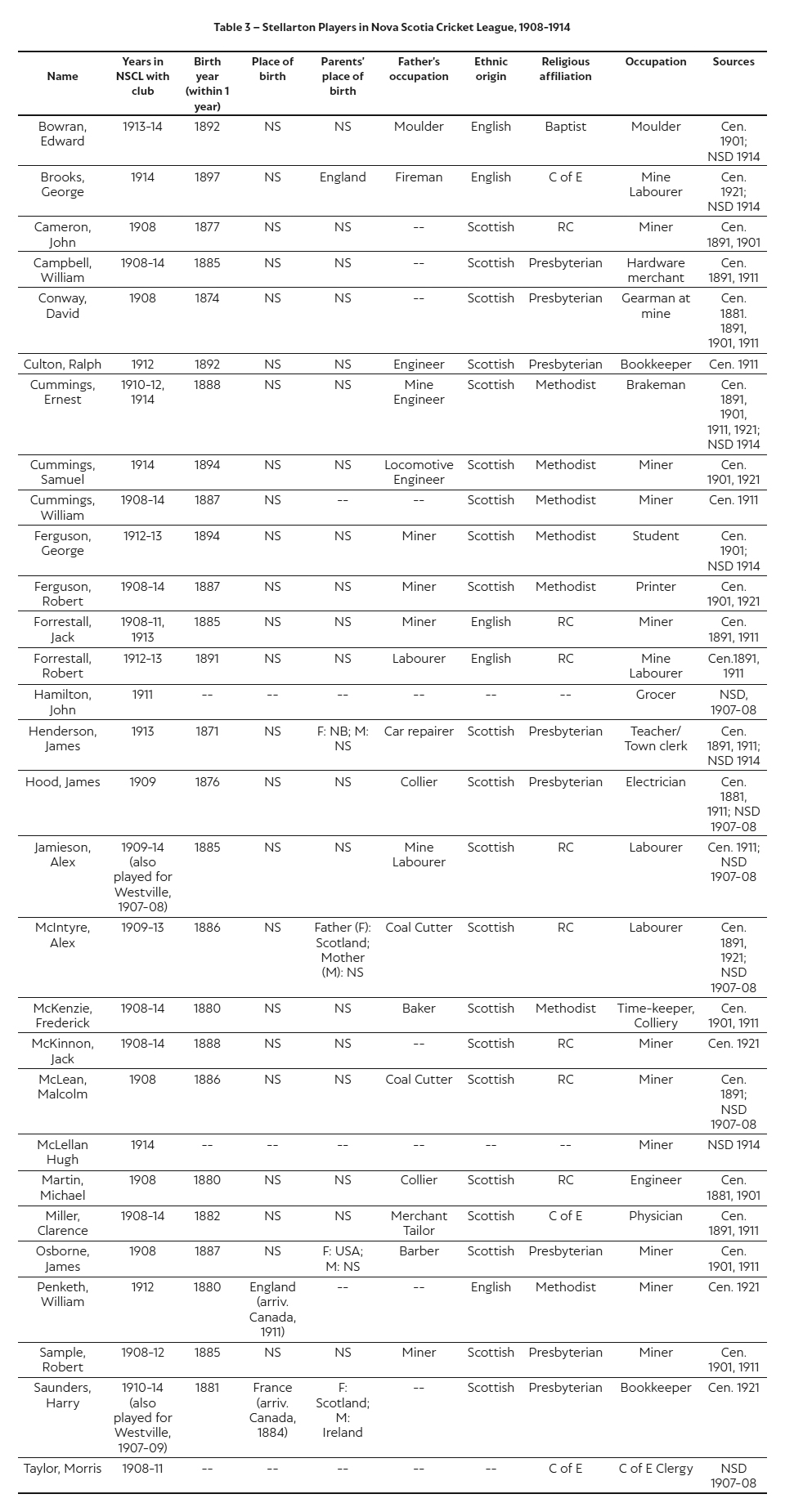

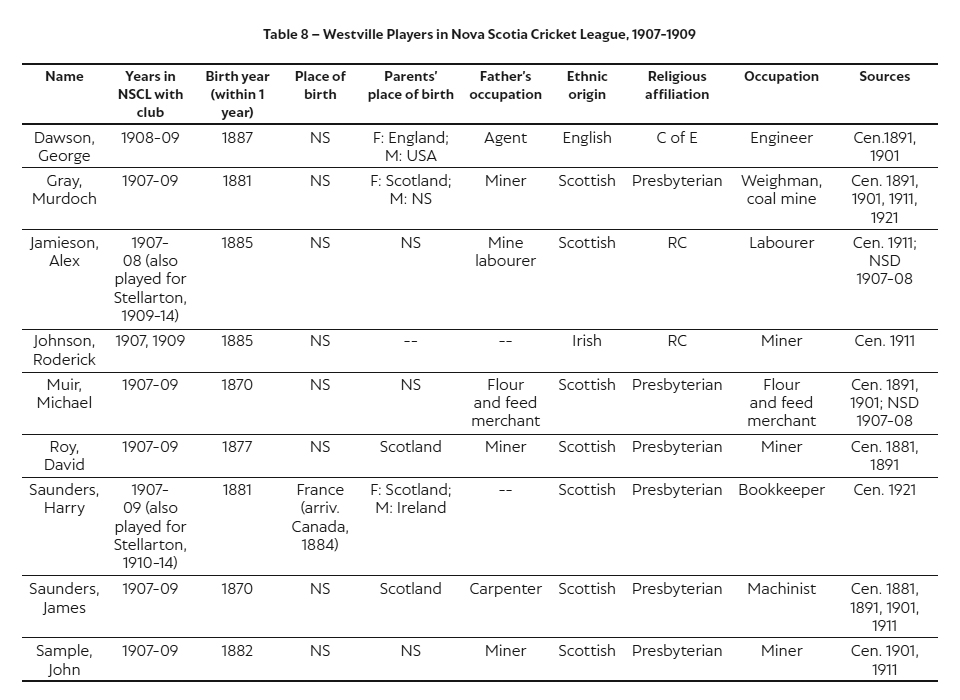

22 In Pictou County, Stellarton and Westville had left the older town clubs of Pictou and New Glasgow far behind by the turn of the century and even a strong pit village team such as Thorburn had lost the ability to compete effectively. In the NSCL it was not strictly necessary to be a coal miner in order to play for either of the two leading teams, although miners and other pit workers formed the majority. Of the nine identifiable Westville players, Michael Muir was a flour and feed merchant, while Harry Saunders was a keeper. The 29 identifiable Stellarton players included – as well as Saunders and another bookkeeper – a grocer, a hardware merchant, a printer, an electrician, a moulder (presumably at the nearby Scotia steel works), a student, and three members of the town’s tiny professional elite: the physician Clarence Miller, Church of England rector Morris Taylor, and for a single season the teacher and town clerk James Henderson. All the others were either miners, “mine labourers,” or had skilled occupations within a mining context such as brakeman, gearman, or timekeeper. With the exceptions of Saunders, whose birthplace was in France, and the English immigrant miner William Penketh, all of the 26 whose birthplaces can be established were Nova Scotiaborn and the main religious affiliations were Methodist, Presbyterian, and Roman Catholic, though Miller, Taylor, and the mine labourer George Brooks belonged to the Church of England. For Westville, mining occupations also predominated, as did Nova Scotia birth (universal except for Saunders), and the Scottish Presbyterianism of seven out of the nine. In summary, both clubs fielded community teams, but they were community teams that reflected the largely working class character of the sport in the county in the NSCL era.63

Display large image of Figure 3

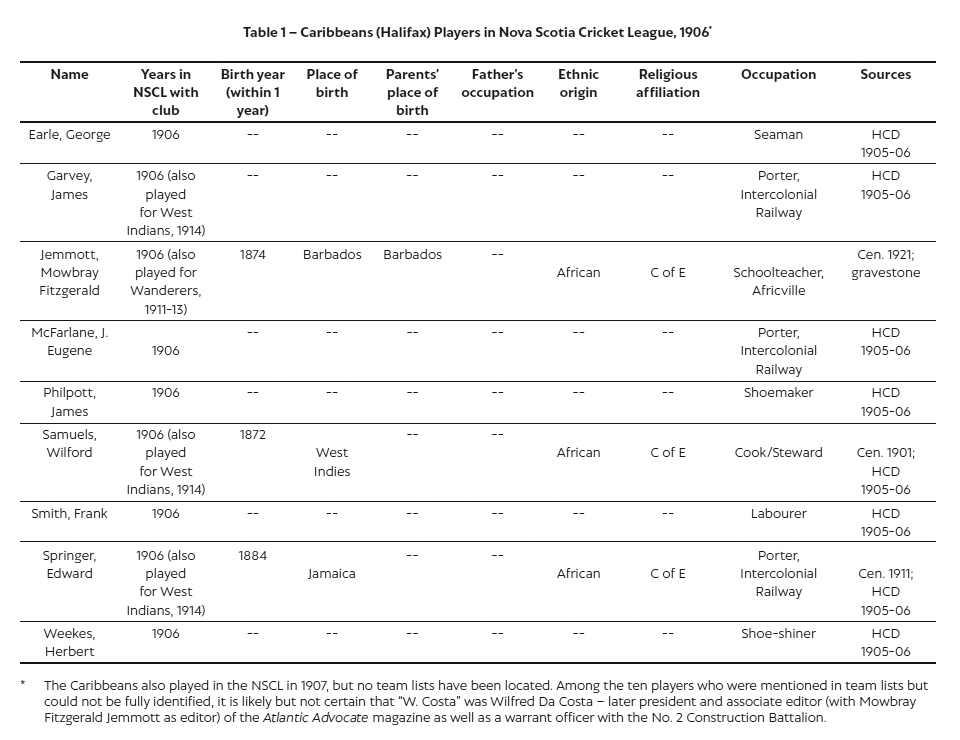

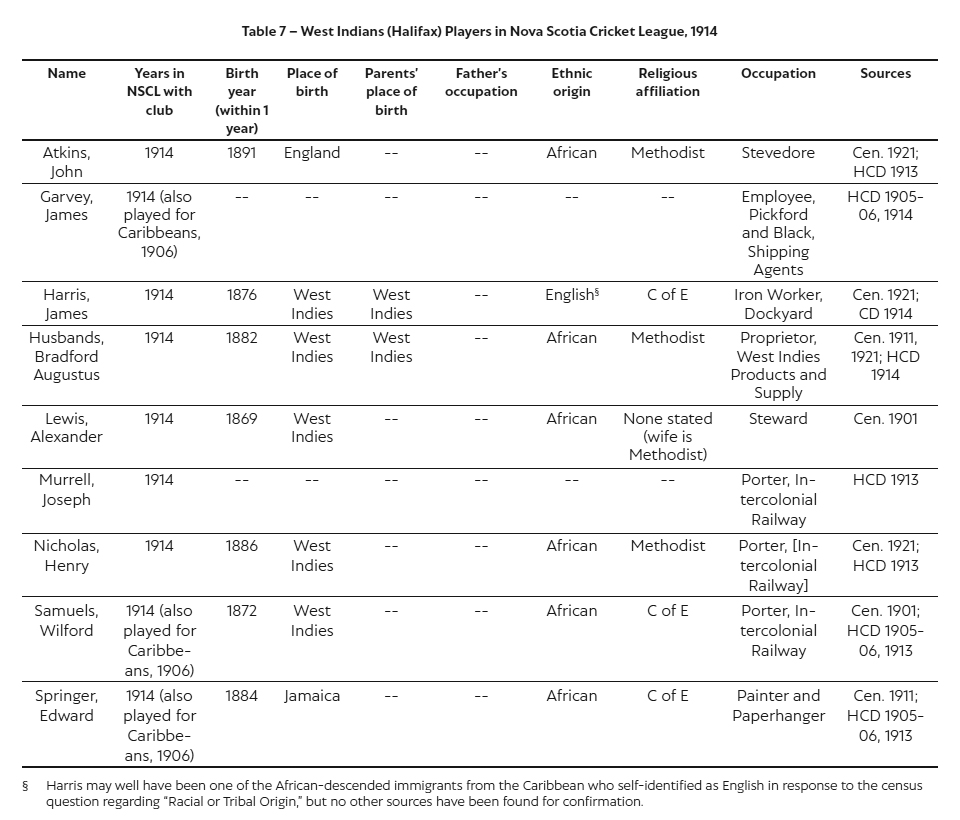

Display large image of Figure 323 Finally, the teams that were composed of players of African descent who had Caribbean connections had a strong character as neighbourhood clubs. The naming of the Whitney Pier Cricket Club, which had antecedents in the earlier Steel Workers Cricket Club, spoke for itself. Of the 13 reported players who represented Whitney Pier during its only NSCL season in 1914, only six can be identified. All were born in the British West Indies, all professed to be adherents of the Church of England, and all were labourers at the steel plant – in two cases, specifically in the open hearths. Only in age did they diverge significantly. William Knight and Alfred Prescott, both of whom had previously played in the league for Sydney, had reached their mid-30s, while Osman Seale was a recent immigrant still in his late teens.64 The Halifax Caribbeans, meanwhile, used 19 players during their first season in the NSCL in 1906. The club remained in the league in 1907, but listings of the team are absent from newspapers. Of the 19 players of 1906, at least partial identifications can be found for nine; however, only three of these were located in census records while the others were found in city directories only. Of the three for whom fuller details can be given, one was Jemmott and the other two were Wilford Samuels, a cook and steward (presumably aboard ship) and Edward Springer, who was a porter on the Intercolonial Railway (ICR) but later became a painter and paper-hanger. Springer, in his early 20s, specified Jamaica as his birthplace, while Samuels was in his mid-30s and gave his birthplace only as the West Indies. The occupations of the others were diverse: George Earle was a seaman, James Garvey and Eugene McFarlane were also ICR porters, James Philpott was a shoemaker, Frank Smith a labourer, and Herbert Weekes a shoe-shiner. What is most striking is the addresses at which they lived. Eight of the nine lived within a few minutes’ walk of one another, on the parallel streets of Creighton Street and Maynard Street, in the city’s north end, while Jemmott’s home on Gottingen Street was also close by. This was, if generalization can be made from just under half of the players, a neighbourhood team in the most literal sense.65 When the team made its return to the NSCL as the West Indians club in 1914, only Garvey, Samuels, and Springer were still playing. They were three of only nine who can be identified out of 25 players, making overall assessment even more difficult. John Atkins, though born in England, was a stevedore identified in the census as being of African descent. James Harris was an ironworker at the naval dockyard. Bradford Augustus Husbands was a “general agent” who was also the proprietor of a firm designated as “West India Products and Supply.” Alexander Lewis was a ship steward, while Joseph Murrell and Henry Nicholas were both ICR porters. Eight of the nine can be placed at addresses, and again all were close to one another on Creighton Street (3), Maynard Street (2), Gottingen Street (2), and John Atkins on nearby Cornwallis Street. An article in the Morning Chronicle, however, hinted at the drawing of players from further afield, possibly also explaining how large was the number of players used in a single war-shortened season and how few of them can be identified in census and directory records: “The . . . [West Indians] will be a strong aggregation, consisting of several of the best men on last year’s Fenwicks team, together with some of the stewards of the West Indian boats, among whom there are some great cricketers.”66 Thus, along with neighbourhood roots, the 1914 West Indians may well have had a rolling complement that included players who had even more direct connections with the Caribbean than hitherto.67

24 Thus, the NSCL was noteworthy in part simply for the inherent diversity of the participants. Some motivations for playing cricket were undoubtedly shared across the spectrum, in that physical exercise and recreation are common purposes of sporting activity and also in that team sports offer an additional opportunity for social contact and competitive achievement. But other inducements were more particular. Part of the story of the NSCL lies in professionalism. It is safe to say that nobody became wealthy as a result of playing cricket in the province, in the NSCL or any other arena. Nevertheless, some players received sufficient compensation to make a temporary livelihood while others enjoyed financial or other benefits that augmented their other resources. The NSCL itself defined professionalism carefully, and put limits on its scope. As the league prepared in May 1907 to enter its second season, the annual meeting – including the executive officers and representatives from all the clubs – held “a very lengthy discussion” on professionalism and arrived at a conclusion. The league would “allow a club to play its professional coach in the league matches, provided that he was a bona-fide resident of the town for which he plays, and that each club register its professional coach.”68 The newspaper report of the meeting made no mention of whether a vote was required in order to pass the regulation, but it could have come as no surprise over the ensuing years that the only clubs to appoint professional coaches were the Wanderers and Sydney. This continued the longstanding practice by which clubs in urban centres in both New Brunswick and Nova Scotia had the resources to hire professionals, and did so at times to the resentment of less prosperous opponents. As early as in 1887, the Moncton Cricket Club found it impossible to withstand “the bowling of Comber, St. John’s professional”; but in 1901 it was the Moncton club itself that hired the controversial “Roberts, the professional trainer.”69 The problem with Roberts was that he had spent the previous two years as professional coach to the Truro club and had continued to play for that club even after moving to live in Moncton. Following a match between Truro and Windsor in 1900, there had been “some talk about a protest against Roberts but it is a good experience for amateurs to butt against ‘cracksmen’ on the crease once in a while.”70 The Wanderers, meanwhile, had a series of professional coaches following the turn of the century, including “Lohman” in 1901, whose origins were English but who was recruited from a similar position with the Staten Island club in New York.71 Henry Davy, also English-born and at the time a gunner in the Halifax garrison, followed Lohman in 1902.72 Davy ultimately had a long career with the Wanderers, playing for the club in every NSCL season. Indeed, his role had a connection to the NSCL’s approach to professionalism, as obliquely indicated by “Rover,” a regular correspondent of the Halifax Herald, who observed in July 1906 that “I am pleased to hear that the Wanderers have decided to play Davy again this season, as it would be a great loss to local cricket to bar such a good all-round man as he is from taking part in the game, and the Nova Scotia Cricket League is very wise, in my opinion, in allowing professionals to play for the club for which they coach.”73 That Davy continued to play for the club, even during the 1912 season when Arthur Leighton was the professional coach, was unusual. Presumably during the later years he was unpaid by the club, although it is entirely possible that the nature of his employment with the Scotia Milk Company might not have stood up well to close scrutiny.

25 Professionalism in Pictou County, while hinted at in the evidence, is more difficult to pin down. As in other sports – rugby, baseball, hockey – in which working class community and workplace teams emerged, compensation for players could take many covert forms. Harry Saunders was one player whose career was likely shaped by such considerations. Saunders had been recruited from Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1901, while that club was on a New England tour. He returned temporarily to play in Providence and New Bedford in 1905 and 1906, and even after his move from Westville to Stellarton in 1910 he was reported in 1913 to have briefly “forsaken cricket to play professional ball.”74 Saunders remained primarily a cricketer while also playing baseball in some seasons, and his frequent changes of team and of sport suggest a degree of pragmatism beyond the pure love of playing. More generally, expense payments were in cricket – notably in England, on a scale reaching even to the famous W.G. Grace – a time-honoured vehicle for informal compensation. In a revealing episode in 1908 the Westville club, as reigning NSCL champions, accepted an invitation to visit the Sydney Cricket Club, which had not yet entered the league. In a large front-page headline, the Sydney Daily Post trumpeted that “The Local Cricketers are Making Big Preparations” to receive the champions.75 The visit did ultimately take place a number of weeks later, but not until repeated delays had arisen from Westville’s requirements for upfront expense guarantees ranging up to the substantial sum of $50.00.76 At an individual level, suggestions came from Stellarton in 1906 that the duties of a Westville player at the Drummond colliery were purely nominal while many years later the Westville cricketer George Dawson recalled – although this was in a context of baseball, which along with many other Pictou cricketers he also played – that “instead of a regular salary he received his travelling expenses, an arrangement that suited him perfectly.”77 Thus, while professionalism in Pictou County may have been less overt than for the Wanderers or when in 1911 the Sydney Cricket Club hired James Gardiner as “special coach” – whose cricket experience supposedly extended to “England, Scotland, Ireland, Malta and India” – it was nevertheless an inescapable subtext of the sport.78

26 For other players of the NSCL era, however, amateurism also had its rewards. At the most practical level, participation in cricket through one of the more traditional town teams – or in an urban context through the Wanderers or the Sydney Cricket Club – could be not only a declaration that the player was self-sufficient to the point of having the leisure time to invest in the sport but also a way of entering a social network that afforded the hope of upward social mobility. In a gendered and imperial context, moreover, playing cricket could be seen as a laudable display of manly and gentlemanly values, expressed through what the Hants Journal described unoriginally in May 1907 as “this noble English game.”79 As Jared van Duinen has noted in an Australian context, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw an increasingly explicit association of sport – and cricket in particular – with empire in the settler dominions.80 Thus, among many such evocations in Nova Scotia, the visit of the Sydney club to Halifax during its first NSCL season to play both the Wanderers and the Garrison in 1910 led a grandiloquent correspondent of the Halifax Herald to praise the players of all the clubs for “upholding the grand old game of England,” while observing that “Sydney has given an impetus to cricket this year, which will do much good. They are good stuff and play the game in a manly and straightforward spirit.”81 Of the social benefits of modelling imperial masculinity there could be no doubt, and yet there were many purposes to which such values could be turned and which in reality demonstrated social cleavages rather than a happy and respectable consensus. Minor in itself, but revealing, was the decision by the Sydney club in 1911 to justify the levying of an admission charge for cricket matches held in the otherwise public environs of Victoria Park on the ground that the practice would “assist in this small way to advance the interests of gentlemanly and manly outdoor games.”82 Also in Sydney, though somewhat before the NSCL era in the city, similar rhetoric was used to rebuke outbreaks of rowdy behaviour and theft at a match between the home club and a combined team from Sydney Mines and North Sydney. The report in the Sydney Daily Record commented that all of it “goes to show that the youth of the city today have not that inbred manliness and gentlemanliness that characterized the boys of the past,” and that the “continual hooting and rooting” of the crowd “may be the usual and proper caper at a game of baseball, but it is decidedly obnoxious to gentlemen who play the gentlemen’s game of cricket.”83 At the most general level, I have argued elsewhere (with Robert Reid) that there was a highly practical discursive element to the expression of imperial and manly values regarding Nova Scotia cricket that helped to bridge the social separations that existed in a diverse and heterogeneous sport.84 Thus, when the Pictou County press described in lyrical terms the encounter in 1910 between two teams with very different social class compositions, there was in reality more at stake than the words themselves conveyed:

27 Yet imperial and gender-related values were also integral to the entry of the Caribbean clubs and players into the NSCL. The extended visit to England in 1900 of a West Indian touring team within which the inclusion of key African-descended players went far beyond a token presence, had launched a new phase in the negotiation of race in West Indian cricket. Although, as Geoffrey Levett has pointed out, objections to racial mixing in the team by English commentators were compounded at times by racist abuse, and even more so during a subsequent tour in 1906, while the increasing influence of South Africa in imperial cricket also tended to marginalize West Indian participation, nevertheless within the West Indian colonies cricket continued to offer opportunities for limited social advancement.86 As Aviston Downes has argued, education modelled on English public schools was provided for a minority of pupils of African descent; but the version of the imperially shaped masculinity that these schools advanced was then broadened to a wider cohort of working class men, who blended in a sport culture that emphasized, among other things, an admiration for fast, aggressive bowling as opposed to any idealization of cultured batting.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 428 Association of masculinity and empire, especially if acting upon these values through sport or through enlistment in imperial forces was expected to lead to colonial reform and social justice, was not contradictory to this cultural evolution.87 Thus it is not surprising that among the Halifax Caribbeans and the subsequent West Indians club there were direct personal associations that linked cricket both with the No. 2 Construction Battalion and with the publication during the First World War of the Atlantic Advocate. Jemmott was of course a central figure: a spin bowler of exceptional menace to opponents, who in his first NSCL match took all ten Garrison wickets for a paltry 15 runs; a teacher who emphasized imperial participation to students who would subsequently enlist; and the founding editor of the magazine.88 It is also likely, though not established conclusively, that the “W. Costa” who played with Jemmott for the Caribbeans long before the foundation of the NSCL but also in the league’s first season, was Wilfred Da Costa, who was the publisher of the Atlantic Advocate and also served as company sergeant-major with the battalion.89 Wilford Samuels was another cricketer who served, as a private, and Samuel Reece of Truro – in addition to his recruiting efforts – was a corporal.90 In a context where African-descended West Indians, like African Nova Scotians, had to struggle to be accepted for service – at enormous personal cost, not least to the Jamaican volunteers who endured freezing conditions on a troopship in Halifax harbour in May 1916 – Caribbean-related cricket in the NSCL formed one important dimension of a forceful advocacy network in which sport, journalism, and overseas service were closely aligned.91

29 Thus, already a deep-rooted and socially diverse settler sport as it emerged from the 19th century, cricket developed into greater maturity in the pre-1914 era, with the NSCL integral to this process. Not only did players from diverse social backgrounds routinely share the playing surface while facing one another as opponents, but in the NSCL there were also instances where the same would go for teammates. Even an imperial and gender-related discourse could serve to bridge awkward disconnections. Not that there is any scope here for a triumphalist narrative. Cricket could never dissociate itself fully from stresses that continued to exist in society at large, whether those of social class or of race. There was no better symbolization of class tensions in the sport than the occasions during the summer of 1909 when the Sydney Cricket Club hospitably entertained visiting teams from the Royal Canadian Regiment and the Royal Canadian Engineers as the soldiers took a break from intervening in the ongoing coal strike of that year – an intervention at the expense no doubt of striking miners who were also players in the Cape Breton Cricket League.92 And while players with the Caribbean-related clubs could at times be greeted with tributes to their genial and gentlemanly demeanour, they were also subjected to such clumsy wordplay as being described in a Sydney newspaper as “the west Indies ‘dark’ horses.” As well, there was an acrimonious dispute during the summer of 1913 over scheduling of a match between the Sydney Cricket Club and “the West India XI of the steel plant” – the forerunner of the Whitney Pier Cricket Club – that quickly took on ugly racial overtones.93 Nevertheless, sport in many historical contexts has taken the role of facilitating the negotiation of social differences and, in Nova Scotia in the era of the NSCL, cricket had developed certain distinctive abilities to do so. For the historian, cricket has the additional benefit of inviting international comparison and linkage, as the sport took on new characteristics that were particular to settler dominions and other colonial settings.

30 The study of Nova Scotia cricket also suggests the possibility of a wider reappraisal in a more broadly Canadian context. While sport diffusion to and among the component societies of British North America had varying trajectories depending on the chronology of the geographical spread of settler colonialism, the existence of complex social and cultural patterns within the settler sport of cricket outside of Nova Scotia – and outside of the Maritime region – deserves to be more fully explored. The Canadian experience of this exceptionally widespread sport of the “long” 19th century – to 1914 – can offer insights of importance not only to Canadian history itself but also to a vibrant international historiography.

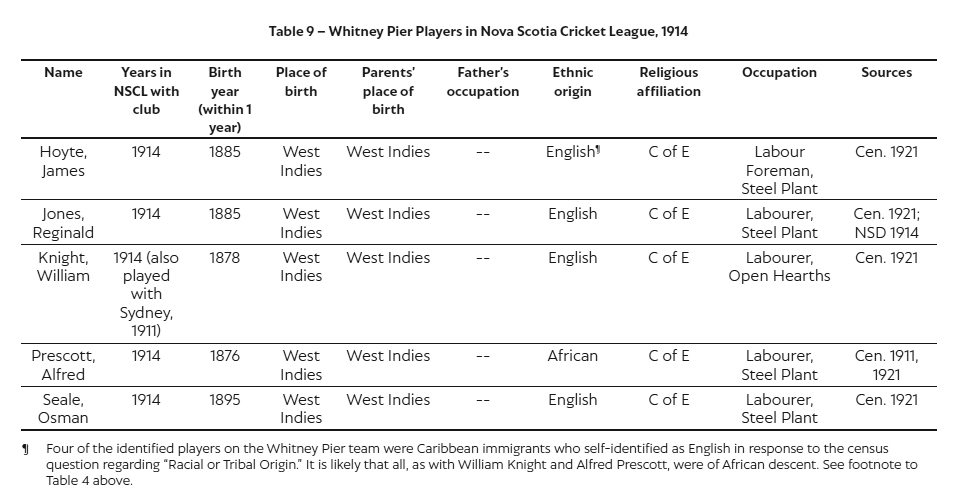

Introduction to tables

The ten tables below represent names drawn from full team lists published with match reports in the following newspapers: Acadian Recorder (Halifax), Daily Record (Sydney), Eastern Chronicle (New Glasgow), Evening Mail (Halifax), Free Lance (Westville), Halifax Daily Echo, Hants Journal (Windsor), Morning Chronicle (Halifax), Morning Herald (Halifax), Sydney Daily Post, and Truro Daily News. Because not all matches were reported, and not all match reports included team lists, the lists are not necessarily complete for any given club or season, and so the tables are not primarily intended to yield quantitative results. Of the players whose names were listed in the newspaper reports, not all could be identified further – some names could not be located, while in other cases there were too many who shared the same name. For identification purposes, use was made of nominal census returns (accessed through Ancestry.ca), provincial McAlpine’s Directories (NSD) published in 1907-08 and 1914, and the McAlpine’s Halifax City Directories (HCD) published from 1906 to 1914. Identification rates were as follows:

- Table 1 Caribbeans, Halifax, 1906: 9 players identified, 10 unidentified

- Table 2 Garrison, Halifax, 1906-1914: players are identified only by rank, as their names would not normally appear in census records or directories

- Table 3 Stellarton, 1908-1914: 29 players identified, 12 unidentified

- Table 4 Sydney, 1910-1914: 23 players identified, 16 unidentified

- Table 5 Truro, 1912: 7 players identified, 10 unidentified

- Table 6 Wanderers, Halifax, 1906-1914: 40 players identified, 54 unidentified

- Table 7 West Indians, Halifax, 1914: 9 players identified, 15 unidentified

- Table 8 Westville, 1907-1901: 9 players identified, 5 unidentified

- Table 9 Whitney Pier, 1914: 5 players identified, 8 unidentified

- Table 10 Windsor, 1906: 13 players identified, 0 unidentified