Articles

A Reluctant Engagement:

Alliances and Social Networks in Early-18th-Century Kespukwitk and Port Royal

Using a nominal census taken of the Mi’kmaq in 1708 and the Catholic parish records from the Acadian community of Port Royal, this paper revisits Acadian-Mi’kmaw relations at the beginning of the 18th century. Taken together, these sources illuminate Mi’kmaw reproduction in the areas around European settlement as well as family and social networks that linked these two societies. They reveal that the relationship between the Acadians and Mi’kmaq was stronger for some than for others. These were complex relationships determined by local conditions that varied depending on geography, family history, and economic activity..

À partir d’un recensement nominatif de la population mi’kmaq effectué en 1708 et des registres de la paroisse catholique du village acadien de Port-Royal, cet article revoit les relations entre Acadiens et Mi’kmaq au début du 18e siècle. Ensemble, ces sources mettent en lumière la reproduction chez les Mi’kmaq dans les environs de l’établissement européen ainsi que les réseaux familiaux et sociaux qui reliaient ces deux sociétés. Elles révèlent que les relations entre les Acadiens et les Mi’kmaq étaient plus étroites chez certains que chez d’autres. Il s’agissait de relations complexes déterminées par les conditions locales, qui variaient selon la géographie, l’histoire familiale, et l’activité économique.

1 Despite taking place on Mi’kmaw territory, and there having been a century-old diplomatic relationship between Mi’kmaw and French leaders, it was primarily Penobscot and Wolastoqiyik peoples, whose homelands were on the west side of the Bay of Fundy, who came to France’s defense at Port Royal during the first two turbulent decades of the 18th century.1 Time and time again, when New Englanders attacked, the fourth baron of Saint-Castin, Bernard-Anselme d’Abbadie, and a small cadre of western Wabanaki fighters – most likely his kin – arrived from across the Bay of Fundy to defend France’s stake in Mi’kma’ki.2

2 Understanding turn-of-the-18th-century Indigenous-French relations in Mi’kma’ki is fraught with problems. Although Kespukwitk, the Mi’kmaw district where Port Royal was located, was clearly Mi’kmaw territory, historical documents often make sole reference to the presence of western Wabanaki peoples, particularly the Penobscot and Wolastoqiyik, who lived on the territory along and between the Wolastoq (Saint John) and Kennebec Rivers (present-day southwestern New Brunswick and northern Maine). The celebrated 18th-century historian Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix reported the situation in Acadie as such: “The sole resource of the province [Acadie] lay in our alliance with the Indians . . ., and especially of the Abénaquis [western Wabanaki], among whom Christianity had made great progress.”3 In this light, the absence of the Mi’kmaq in the accounts of the British attacks at Port Royal is revealing. Although historians often suggest that the Mi’kmaq played a role in this conflict, Saint-Castin and France’s western Wabanaki allies conducted most of the action accounted for in the archival record.4 The strong documented presence of Wabanaki peoples, particularly the Penobscot, on Mi’kmaw territory, but seemingly without a Mi’kmaw presence, during the late 17th and early 18th centuries requires that we revisit the Mi’kmaq living around France’s administrative capital of Acadie at the turn of the 18th century.

3 This article builds on William C. Wicken’s work exploring Mi’kmaw experiences of the British conquest of Acadie to further explain why the Mi’kmaq were seemingly absent during Port Royal’s final days as an outpost of the French empire. In his contribution to John Reid et al.’s The “Conquest” of Acadia, 1710: Imperial, Colonial, and Aboriginal Constructions, Wicken demonstrates that in the years leading up to 1710, when Britain defeated the French at Port Royal for the final time, France had little success in drawing the Mi’kmaq towards their settlements. Wicken maintains that, as a consequence, when the British arrived, most Mi’kmaq tended to their own material interests as winter approached rather than aiding in Port Royal’s defense. Britain attacked the French capital in the late fall, the height of the Mi’kmaw eel fishery, and all their men were required for the harvest. The Mi’kmaq could not afford to send their men in defense of the marginal French village and garrison.5

4 Although Wicken’s explanation helps us understand the Mi’kmaw absence during this final conflict, Saint-Castin and the western Wabanaki’s dominance in the historical record calls for greater attention to the specific nature of Indigenous-French alliances at the turn of the 18th century. Analyzing the 1708 French census of the Mi’kmaq, a source that underpinned Wicken’s work, reveals some of the underlying reasons why the Mi’kmaq were weary of frequent interaction with Europeans and only seldom appear in European documentation. Likewise, a closer examination of the parish registers from the Catholic church at Port Royal provides a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between Acadian farmers and local Mi’kmaw residents. Taken together, these two documents provide us with an opportunity to explore early-18th-century Mi’kma’ki in a specific and nuanced way that helps us address local circumstances and contexts within a historiography that tends to more often draw general conclusions.

5 This is important because alliances – though widespread – were also profoundly local during this period.6 Though France had missionaries and military officers in place to maintain relationships among the Penobscot and Kennebec, at Port Royal the relationship with the Mi’kmaq primarily developed with specific Acadian families whose relationship to French authority was ambiguous. On the eve of New France’s fall, none of these relationships were strong enough to warrant widespread Mi’kmaw support of French interests. After Britain replaced France as the more dominant imperial influence in the region, local and specific sets of relationships continued and were shaped primarily by three family groups: the Robichauds, the Pellerins, and the Savoies. What is interesting about these alliances is that some members of these families collaborated with the British following France’s official departure, pointing to the pragmatic choices Acadians and Mi’kmaq had to make if they were to continue living around the new British imperial outpost.

Enumerating the Mi’kmaq and Wabanaki

6 In 1708, the French took detailed censuses of their Indigenous allies along the Atlantic coast.7 The censuses enumerated ten groups: the Wabanaki communities along the Kennebec, Penobscot, and Wolastoq River, where the Saint-Castin family and Wabanaki defenders of Port Royal were based, and Mi’kmaw communities in the districts of Epekwitk aq Piktuk, Sipekne’katik, Kespukwitk, Unama’kik, Siknikt, and Eskikewa’kik; for the most part, the Mi’kmaw census covered the territory that today comprises the province of Nova Scotia.8 The census reveals much about life in these 18th-century Mi’kmaw and Wabanaki communities. Not only does it illuminate the dynamics of these societies as a whole, but, in enumerating community by community, it also provides an opportunity to understand regional differences between each community and their relationships with the French. Taken together, they provide us with a window onto Mi’kma’ki at the dawn of the 18th century.

7 Though these Wabanaki and Mi’kmaw communities were enumerated at the same time, each group was enumerated differently and this reflected their differing history of French engagement. From 1690 to 1701, for example, the French administration was located on the Wolastoq River in Wolastoqiyik territory and focused upon expanding New England settlement near the Kennebec River, while peninsular Mi’kma’ki was more-or-less ignored by imperial officials. Following the Treaty of Ryswick, however, French officials returned to Port Royal and took a much keener interest in affairs there.9 As such, at Penobscot, the census was conducted by the long-time resident missionary Pierre de la Chasse. He enumerated these communities by name and “cabin,” but left out specific details regarding family relationships and ages that may have been well known to French officials. Similarly, along the Kennebec, the census only enumerated the men present in the community who were able to fight; being on the front lines of New England expansion, their families had moved to safer locales – some, but not all, to Canada. On the Wolastoq River, the census enumerated only men and boys who could bear arms, also leaving their relationship to the broader population unclear. With a relatively new presence in Mi’kma’ki, and the growing threat of New England attack, France sought much more specific information about the Mi’kmaq. The newly arrived missionary, Antoine Gaulin, was charged with enumerating Mi’kmaw men who could bear arms. In the process, he recorded the names, ages, and family relationships of each member of the communities he encountered.

8 The difference between the Penobscot and Mi’kmaw censuses is telling. The Penobscot census enumerates their society by cabin and better reflects social organization by including widows and orphans within their specific households, whereas the Mi’kmaw census focuses on nuclear family structure, leaving widows and orphans as a category of their own; we know little from this document about how they fit into Mi’kmaw society. The differences between the two censuses – specifically the inclusion in the Mi’kmaw census of ages and absence of information about residency – likely reflect the deeper relationships France had among the western Wabanaki as well as their relative ignorance of the Mi’kmaq. This conclusion is reinforced by examining the Mi’kmaw census in greater detail, using what we know about age and family structure to draw some general conclusions about the state of Mi’kmaw society at the turn of the 18th century.

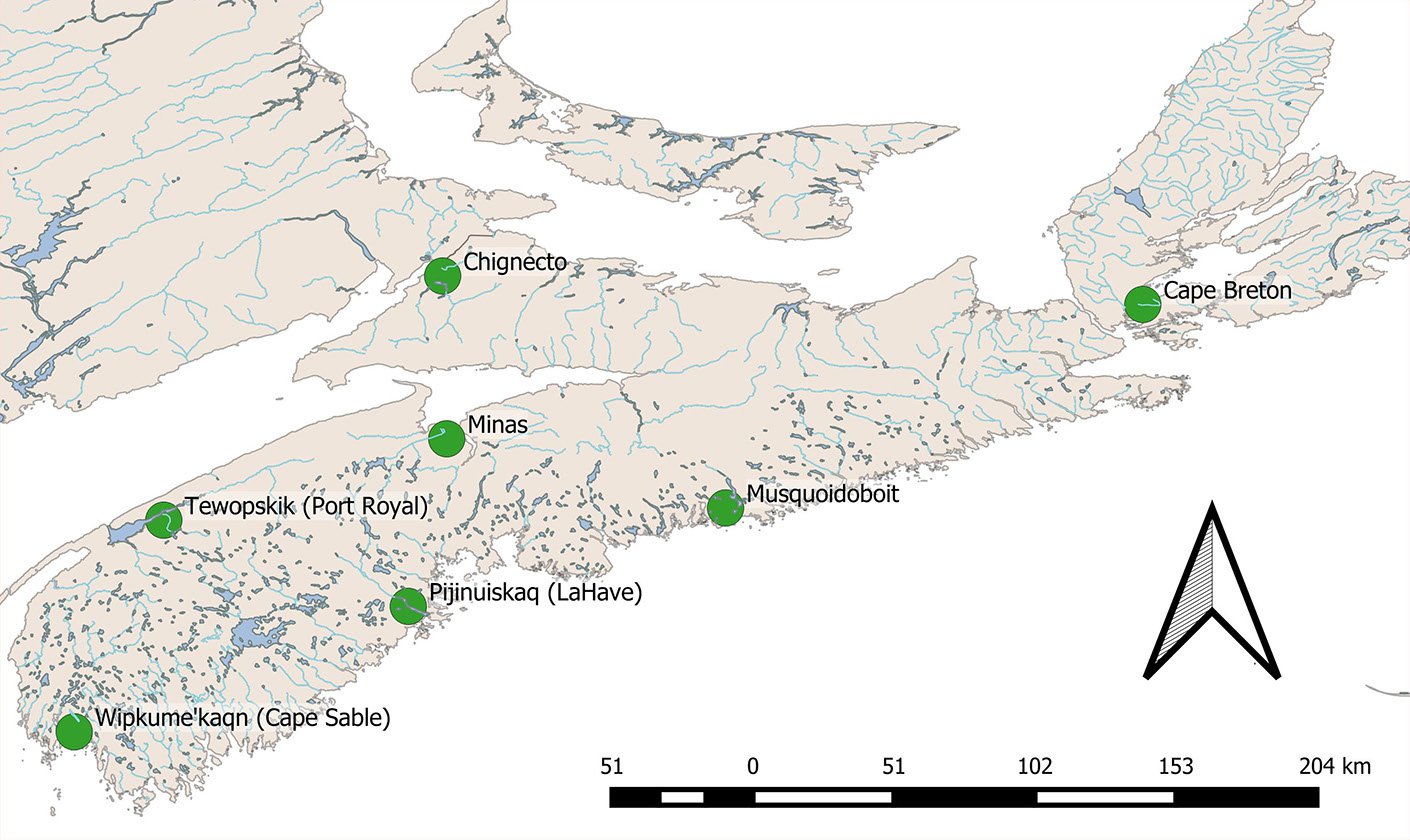

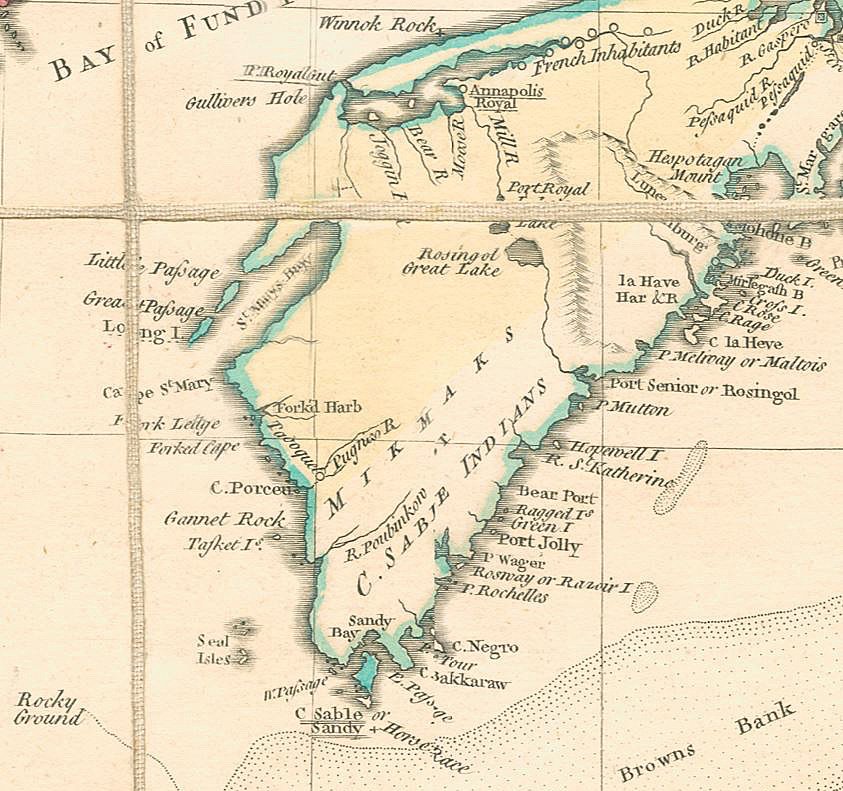

9 Gaulin was the first missionary in nearly a century to work extensively in peninsular Mi’kma’ki. He recorded the names, ages, and family groupings for 836 people living in the seven communities: Port Royal, Cape Sable, La Hève, Minas, Musquodoboit, Cape Breton, and Chignecto. It is very likely that Gaulin – who had only begun actively serving as a Roman Catholic missionary to the Mi’kmaq and was likely not familiar with their population – under-counted. In addition to communities about which he may have been unaware, his census does not account for Mi’kmaq that may have been away hunting or travelling or who, due to his association with cultural and religious conversion, may have been unwilling to interact with the missionary. Nonetheless, the details within the census provide the most specific information available about 18thcentury Mi’kma’ki. As such, the census, which covers at least part of six of the Mi’kmaq’s seven districts, serves as one window into Mi’kmaw family and village life as well as relationships with neighbouring communities in the years immediately before the fall of Port Royal. The descriptions of this world, provided below, should be read recognizing the biases of the 18th-century colonial record and the scholarship developed from it.

10 Each of the communities on the census most likely represents a Mi’kmaw summer village. Summer villages were social and political units primarily composed of households allied to a particular keptin and situated around a particular geographical feature, usually a key river or bay. At these villages, families could interact with each other, men and women could find partners, and collective decisions could be made about issues that affected the community as a whole such as trade and war.10 Rather than representing a permanent village with a fixed population, the summer village was a stable location from which Mi’kmaw families could move in and out depending on the availability of resources and their desire to visit friends, trade with neighbouring communities, or engage in warfare.11 In Kespukwitk, where Port Royal was located, Gaulin enumerated three summer villages: Tewopskik (near Port Royal), Wipkume’kaqn (which the French and English called Cape Sable) and Pijinuiskaq (the LaHave River).12 Gaulin recorded 102 Mi’kmaq living at the summer village at Tewopskik, around Port Royal, in 1708.

| Population | Male | Female | Children13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Port Royal | 102 | 28 | 35 | 39 |

| Minas | 59 | 14 | 20 | 25 |

| La Hève | 126 | 33 | 32 | 61 |

| Cape Sable | 97 | 32 | 26 | 39 |

| Chignecto | 97 | 30 | 29 | 38 |

| Musquodoboit | 159 | 44 | 41 | 74 |

| Cape Breton | 196 | 55 | 55 | 86 |

| Total Kespukwitk | 325 | 93 | 93 | 139 |

| Total | 836 | 236 | 238 | 362 |

11 Although beyond the census there is little information about Tewopskik during the first half of the 18th century, early-17th-century accounts of the area suggest that the location was chosen because of its easy access to inland resources and annual fish migrations. When Pierre Dugua de Mons and Samuel Champlain arrived in 1605 following a disastrous winter spent on Saint Croix Island, on the other side of the Bay of Fundy, they initially built their fort near a Mi’kmaq community. The French and Mi’kmaq were so close that Parisian lawyer, Marc Lescarbot, was able to inspect the Mi’kmaw community on his first day in Mi’kma’ki. He later added that the Mi’kmaq lived only four hundred paces from the French encampment.14 Lescarbot’s interpretation is suggestive that this was a summer village; he arrived at the height of summer and immediately claimed to have inspected Mi’kmaw wikuom.15 This was the last time, however, that the community at Tewopskik was described in much detail. With time, the Mi’kmaq seem to have moved away from the French settlement or warranted less interest from visitors and colonial officials.

12 The community, however, must not have moved far. The Mi’kmaq maintained somewhat frequent interaction with some Acadians and French administrators. In 1703, for example, a Mi’kmaw man named Louis was paid for running letters to various outlying French settlements.16 Jean Delabat’s 1708 map, which otherwise lists property by the name of the landholder, indicates “cabanes” directly across the river from the main village.17 Although not specifically indicating a Mi’kmaw presence, the absence of more specific information about the individual landholder and the title “cabanes” – a term often used to demarcate an Indigenous presence – suggest that this may well have been a Mi’kmaw encampment. After the French defeat the British twice chastised Prudent Robichaud, a well-known Acadian settler who worked closely with them, for interacting with the Mi’kmaq, suggesting that they continued to live nearby.18 The interactions between Robichaud and the Mi’kmaq are important because of where he lived. The Robichauds lived at the Cape, southeast of the fort along the river known at various times as the Allains or Lequille River – not far from the present-day community of Lequille, Nova Scotia.

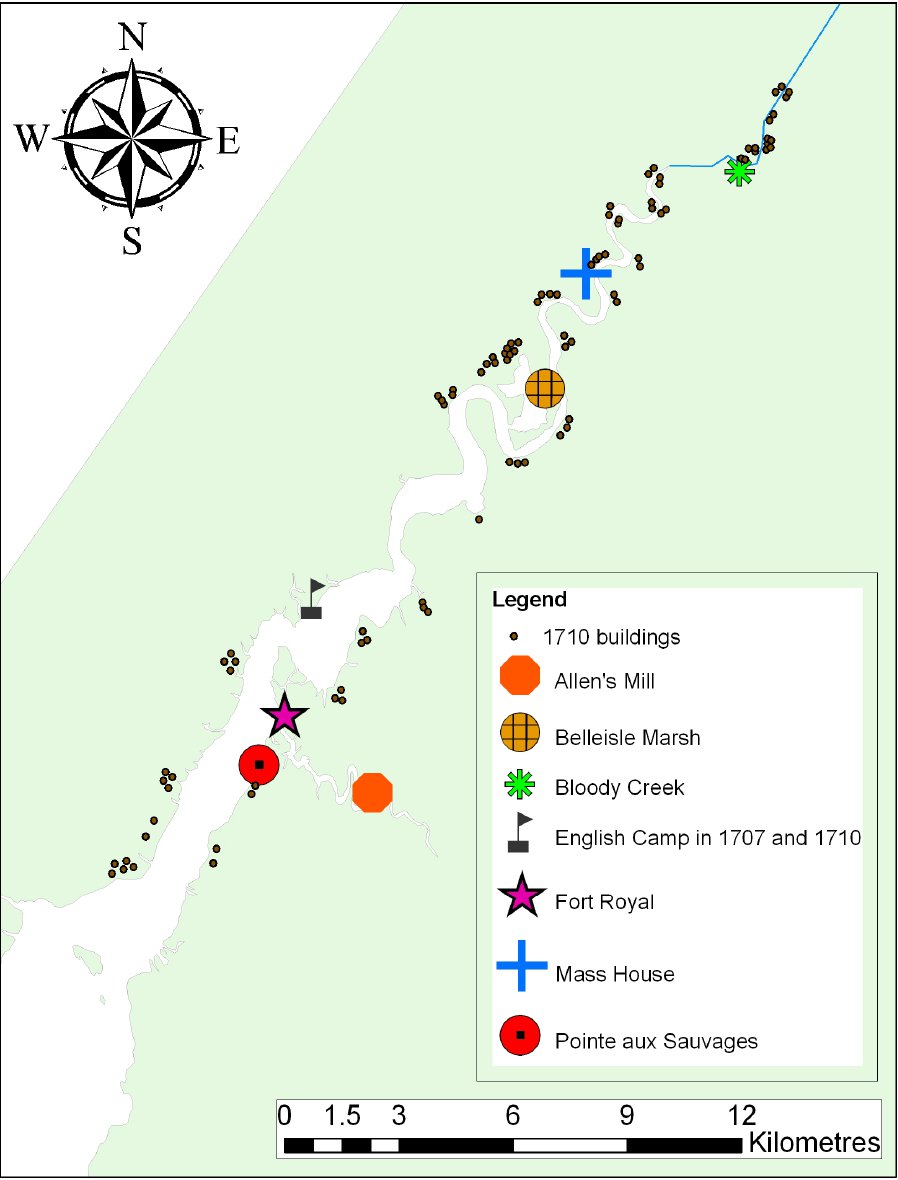

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

13 This area is one of the few places in Kespukwitk where the archival record reveals continuous Mi’kmaq use over the past four centuries. Archaeologists have found pre-colonial Mi’kmaw shell deposits and a Mi’kmaw fishing weir in, and along, this river.19 Champlain’s 1613 map of the area indicates that the Mi’kmaq used this area to fish.20 In the 1680s, Gargas noted the presence of a Mi’kmaw family living in this area. Four others had wikuom near the fort at Port Royal.21 Throughout this period, the southern bank, at the mouth of the river, where the Robichauds settled later in the 18th century, was known as Pointe aux Sauvages – a direct reference to an Indigenous presence.22 In the early 19th century, William Bartlett included a Mi’kmaw encampment in his depiction of the General’s Bridge over the Allains River in Canadian Scenery Illustrated.23 Some Mi’kmaq continued to live in the community of Lequille along the river’s banks during much of the 19th and 20th centuries.24 Indeed the photograph below was taken at Lequille in 1920. It includes Ben Pictou (centre with the white mustache) the well-known Mi’kmaw chief from the community.25 All of this suggests that the river may have been the centre of the Mi’kmaw summer village during the 17th and 18th centuries, though its proximity to the fort and absence in the historical record should caution us from drawing too firm a conclusion.

Display large image of Map 2

Display large image of Map 2

14 At the end of the 17th century the French population around Tewopskik hovered between 500 and 600 people, about one third larger than that of the Kespukwitk Mi’kmaq. Colonists lived in highly diffused settlements along the river they called Dauphin (the Annapolis River today). Few settlers lived near the fort. According to the Gargas census, which also lists each French hamlet around Port Royal, only about 17 per cent of the French population (80 people) lived within the environs of the fort. Another 16 per cent (74 people) lived at Belleisle, about six kilometres upstream. The rest lived in hamlets of between 10 and 25 people spread out along the river for more than 30 kilometres. The French communities at Cape Sable and La Hève were similar in size to these hamlets.26

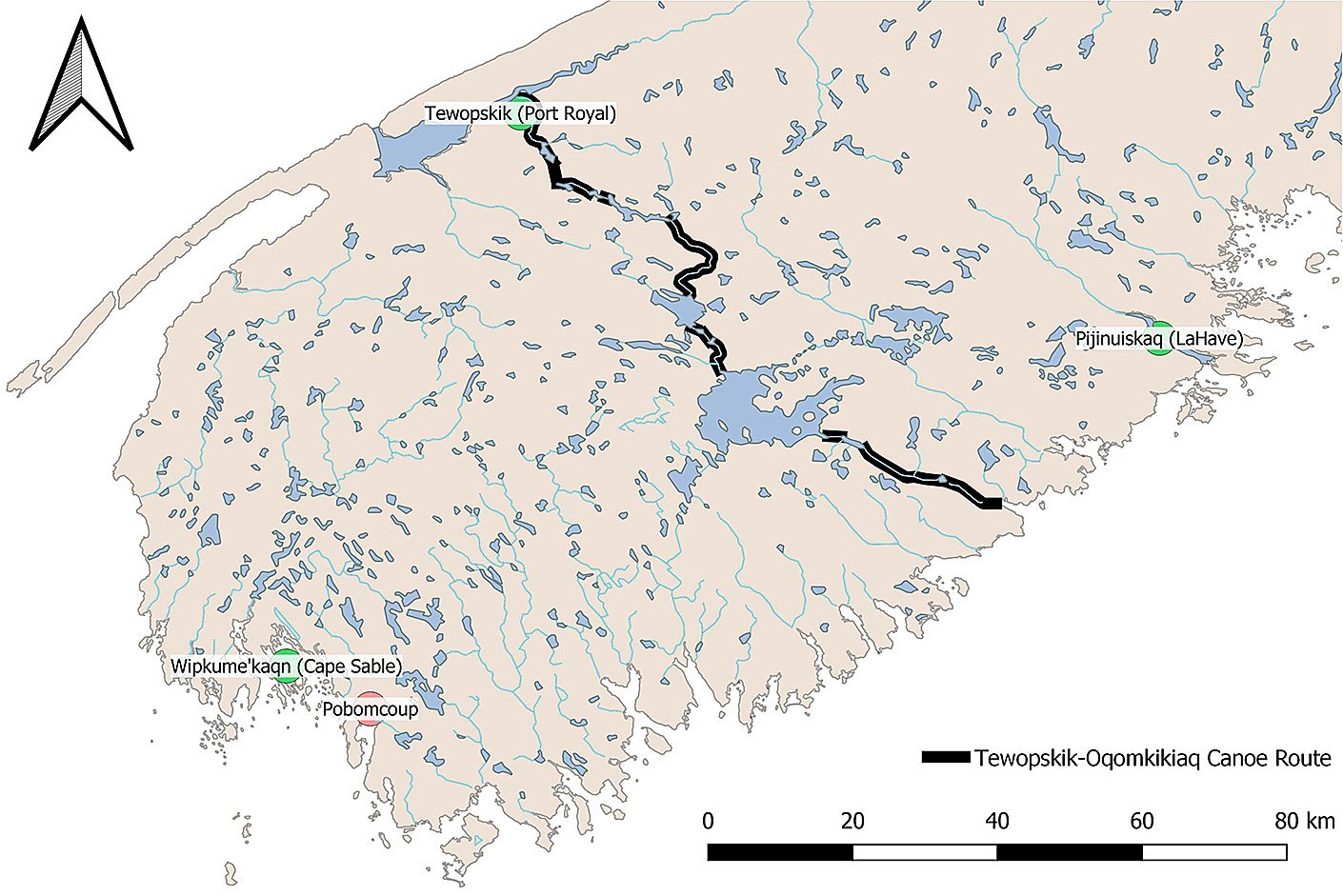

15 The Mi’kmaw community that gathered at Pijinuiskaq (LaHève) in the summer was located across peninsular Mi’kma’ki from Tewopskik on the Atlantic coast; these two places were known to the French as Port Royal and Le Hève (see Map 1). With a population of 126, Pijinuiskaq was the largest of the three communities. The village was located along what is known today as the LaHave River, where Isaac de Razilly briefly tried to start a French colony in 1632. The Mi’kmaw community living in this vicinity were likely connected to Tewopskik through Oqomkikiaq (Port Rossignol/Liverpool), southwest of Pijinuiskaq. From there the Mi’kmaq travelled upriver to the height of land north of Lake Kejimikujik, which connects to the Lequille River. This was a well-known Mi’kmaw canoe route during the 17th and 18th centuries, connecting Pijinuiskaq and Tewopskik.27

16 Although it was the largest village, we know the least about it. Unlike Tewopskik, Pijinuiskaq did not have a large population of French settlers nor was it geographically situated to encounter as many European and New England fishers as Wipkume’kaqn. We do know, however, that for both Mi’kmaq and Europeans it was an important site for the fishery and fur trading. A British report in the 1760s described Pijinuiskaq as having “many Islands well situated for the Curing and drying Cod fish . . . [and] the [La Hève] River is an Excellent Harbour very capacious and navigable having nine fathoms at its entrance and gradual soundings to three fathoms at Nine Miles, and Navigable for Sloops and Smaller Vessels to the Falls, twelve miles from its entrance.”28 It is not clear where along this river the Mi’kmaq lived, though they participated in both the fur trade and fishery.29

Display large image of Map 4

Display large image of Map 4

17 Cape Sable was the general term that Europeans used to refer to all of the Mi’kmaq living in Kespukwitk.30 Unlike Tewopskik and Pijinuiskaq, where the name of the place identified a particular location or key river system, the term Cape Sable referred broadly to a region that stretched from the present-day village of Port La Tour to the town of Yarmouth.31 The principal area of occupation was near the Tusket Islands, where the Mi’kmaq had a summer village at Wipkume’kaqn or “the place of eels.”32 This was the community of Antoine Tecouenemac, the Mi’kmaw man at the centre of Wicken’s essay on Mi’kmaw activities during the final British assault on Port Royal.

18 The 97 Mi’kmaq at Wipkume’kaqn lived a similar distance away from the French settlers as the Mi’kmaq at Tewopskik. The French lived in a village nearby at Pobomcoup, a seigneury that had been granted to the d’Entremont family in 1653.33 Pobomcoup was close enough to be in regular contact with Wipkume’kaqn, but the villages were not side-by-side. Charles d’Entremont, the seigneur during the 1730s, provided some insight into the proximity of the two communities. In 1736 he testified to the British council at Annapolis Royal about Suzanne Buckler. Buckler was the sole survivor of the ship Baltimore, whose crew mysteriously died after the ship put in for fresh water in Tiboque harbour (near Cape Sable).34 After being found by the Mi’kmaq, Buckler lived with them but sought French help. D’Entremont noted that Joseph Vigé, an Acadian who had been fishing eels with the Mi’kmaq, “came to Pobomcoup towards the evening to acquaint them with the Lady’s request.”35 This testimony suggests that the villages were close enough that Vigé could travel to Pobomcoup easily, but far enough away that Buckler would not have otherwise encountered d’Entremont (see Map 3).

19 Encounters with seafarers were common in Wipkume’kaqn and Pijinuiskaq. As the furthest extension of Mi’kma’ki into the Atlantic Ocean, the area was heavily visited by sea-going vessels – particularly fishing vessels from New England. The Kespukwitk Mi’kmaq had interacted with European fishers since the early 16th century, serving as intermediaries in the nascent fur trade between fishers in northern waters and more southern Indigenous peoples.36 This fur trade brought considerable change to Mi’kmaw culture: the writings of many early visitors to the region observed, for example, that some coastal Mi’kmaq had begun sailing European-style ships and speaking a half-Basque pidgin language by the beginning of the 17th century.37 The development of this knowledge and skill is a testament to the many interactions between the Mi’kmaq and Europeans that went undocumented during the 16th century and demonstrates the important place of the ocean in Mi’kmaw society.

20 New England developed a significant fishery off the coast of Kespukwitk. According to George Rawlyk, by 1677 over 500 New England men participated in this fishery, easily bringing in over 12,000 quintals of cod, the size of catch Rawlyk cited for 1676 during King Philip’s War.38 By the late 1690s, the fishery was so important that one trader argued that “nothing but a vigorous asserting of our [New England] uninterrupted right and custom will preserve” the New England fishery along the Cape Sable coast.39 The potential for conflict between New England fishers and the Mi’kmaq grew as more fishers came on shore to fetch fresh water and needed supplies. Most of these encounters went undocumented, but between 1677 and 1710 the Mi’kmaq captured at least 13 fishing vessels along their coasts.40 Most often these attacks were part of broader conflicts with New England, but they could also result from local tensions. The importance of this place for the New England fisheries can be seen most clearly after the Acadian deportation when, in 1760, the land around Wipkume’kaqn was granted to fishers from Cape Cod, Plymouth, Nantucket, and Marblehead.41

21 In addition to its dense fishing traffic, Wipkume’kaqn also had greater regional significance for the Kespukwitk Mi’kmaq than the other two communities. Early writers emphasize that the Mi’kmaq from all three communities buried their dead on an island in the region. For example, after Panounias, a Mi’kmaq from Tewopskik, was killed by the Armouchiquois on the Saco River, his body was kept until spring and then taken to Wipkume’kaqn for burial.42 Similarly, Martin, a prominent leader at Pijinuiskaq during the early 17th century, died at Tewopskik. Rather than being buried there or taken back to Pijinuiskaq, the Mi’kmaq wanted to bury his body at Wipkume’kaqn. The French eventually persuaded them to bury him as a Catholic at Port Royal. Each story demonstrates the significance of Wipkume’kaqn to the Mi’kmaq at both Tewopskik and Pijinuiskaq.43 Burial practices are but one sign that a regional identity – broader than the three-fold division Gaulin decided upon – existed among these communities, anchoring them collectively to the district of Kespukwitk.

22 Only a handful of other documents connect these places together. For the most part they recount relationships between individuals rather than communities. Jesuit Pierre Biard, an early visitor to the region, observed, however, that in the summer months community leaders from different villages came together to make decisions for the common good.44 The archival record does not shed light on how this took place, although it may have involved larger general meetings, on which, by the mid-18th century, French missionaries could capitalize. In 1748, for example, an anonymous French document that surveyed the Atlantic Coast observed that French missionaries would meet between 200-300 Mi’kmaq – about the same size as the three places enumerated – on the Feast of St. Louis (25 August) at Pobomcoup near Wipkume’kaqn.45 Though this article focuses specifically on Tewopskik, the centre of the early French presence in Mi’kma’ki, it is important to remember the importance of these interconnections for the Kespukwitk Mi’kmaq; their world was not centred upon France’s or England’s growing imperial presence.

Demographic consequences

23 By the early 18th century, each of these summer villages faced significant, though different, challenges. In terms of Tewopskik, the population of Acadians at Port Royal was nearly double the enumerated Mi’kmaw population in all of Kespukwitk.46 The Mi’kmaq living around Wipkume’kaqn and Pijinuiskaq were less affected by this demographic growth, but they continued to interact with the coastal European and Euro-American fisheries and other visitors to their shores.

24 The 1708 census provides one avenue for assessing the relative significance of these changes. Using the census, the relative health of the Mi’kmaq living around Tewopskik can be determined by calculating child-woman ratios. Child-woman ratios serve as a useful tool for assessing a society’s fertility in the absence of more detailed source material. Without direct information about childbirth in 18th-century Mi’kmaw society, these ratios use census data to provide a rough estimate of a society’s fertility level. Because the 1708 census provides the ages of the population, we can compare the number of children under five born to married women between the ages of 15 and 49.47 In Tewopskik, for example, 13 women between the ages of 15 and 49 had 11 children age 4 and under. The child-woman ratio for that community was thus 0.85 children per married woman of childbearing age. This technique is ideal for 17th and 18th century pre-industrial societies where, according to Gary Warrick, under normal circumstances – where no outside factors such as malnourishment or other bodily stress affected the mother – the interval between births for the average woman is about 28 months (just over two years). A married woman, then, under a natural fertility regime would have at least one child within this time period but only a handful would have none or two or more.48

25 There are a number of limitations to this approach. To ensure that only women likely to conceive are included in the analysis, child-woman ratios exclude widows and other single women with children under five because they were unlikely to conceive again without a full-time partner. The ratio also does not account for infant and child mortality. Some children who were born during this period died before the census was taken and were thus not enumerated. Likewise, the census is only as good as its enumerator. It is unlikely that Gaulin counted the entire Mi’kmaw population. He was, after all, relatively new to the region. Given that the much better-known Acadian population resisted enumeration from time-to-time, it seems likely that Gaulin would have faced similar, if not more significant, challenges.49 Finally, the 1708 census provides a very small sample size. It only includes 133 mothers and 124 children. Small deviations in the numbers can cause considerable variability in the ratios. Despite these challenges, and in the absence of additional evidence, child-woman ratios provide a useful window in to the overall health of Mi’kmaw society.

| Community | Std Ratio | Ratio | Mothers | Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Mi’kmaq Outside of Kespukwitk | 0.91 | 0.94 | 87 | 82 |

| Total Mi’kmaq in Kespukwitk | 0.79 | 0.91 | 46 | 42 |

| Total Mi’kmaq | 0.89 | 0.93 | 133 | 124 |

| La Hève | 1.05 | 21 | 22 | |

| Cape Sable | 0.75 | 12 | 9 | |

| Port Royal | 0.85 | 13 | 11 | |

| Minas | 0.80 | 10 | 8 | |

| Musquoidoboit | 0.97 | 29 | 28 | |

| Cape Breton | 0.94 | 33 | 31 | |

| Chignecto | 1.00 | 15 | 15 | |

| Port Royal Acadians 1700 | 1.14 | 57 | 65 | |

| Port Royal Acadians 1701 | 1.09 | 55 | 60 |

26 Overall, the enumerated Mi’kmaq had a child-woman ratio of 0.93. Although lower than the child-woman ratios for the neighbouring Acadians at Port Royal,51 most Mi’kmaw communities had child-woman ratios around one. This suggests that the overall Mi’kmaw population was relatively healthy and had few constraints on their ability to reproduce. In fact, when this data is set alongside William Wicken’s child-woman ratios for Mi’kmaw communities at the turn of the 20th century, we find that the early-18thcentury Mi’kmaw population was relatively robust. The child-woman ratios for some communities approach those of the 18th-century Acadians and 19th-century non-Mi’kmaw farming and fishing communities.52 The general scholarly consensus is that fertility in sedentary agricultural societies such as 18th-century Acadie or 19th-century Nova Scotia was higher than in societies, like the 18th-century Mi’kmaq, which had to move frequently to maintain their supply of food.53 On the contrary, these ratios suggest that the effects of frequent migration or – as will be discussed shortly, periodic malnutrition – did not seriously limit Mi’kmaw women’s ability to reproduce.

| Community | Std Ratio | Ratio | Mothers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Kespukwitk – 1708 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 87 |

| Kespukwitk – 1708 | 0.79 | 0.91 | 46 |

| Total Mi’kmaq – 1708 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 133 |

| Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq – 1871 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 259 |

| Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq – 1881 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 285 |

| Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq – 1901 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 218 |

| Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq – 1911 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 242 |

27 Mi’kmaw reproduction had a much more significant effect on the communities that came into frequent contact with European settlers, traders, and fishers. The communities Gaulin listed as Port Royal (Tewopskik), Minas, and Cape Sable (Wipkume’kaqn) all had child-woman ratios that were well below average and share some similarity with Wicken’s 19th-century ratios. The location of these communities near key Acadian villages and French ports-of-call set them apart from the others in the census, which had more-or-less robust child-woman ratios. The Mi’kmaq in these places were more likely to compete directly with Europeans for local resources and were more likely to come into contact with European diseases. Over time, the growth of European settlements and the fisheries likely limited Mi’kmaw access to some resources, forcing them to migrate more frequently in order to sustain their families. Recurrent migration would have increased the stress placed on women, lowering their nutrition while increasing their workload. Both of these changes, then, would have affected the frequency with which women could conceive, limiting their family size.56 Given the difference in child-woman ratios, it seems probable that most Mi’kmaw households were part of stable and relatively sedentary communities. For those living near the French in Kespukwitk, however, competition for resources may have caused migration to play a more important role.

28 This interpretation is reinforced by French descriptions of the Mi’kmaq during this period. Although there is limited evidence indicating a significant change during this period, a few primary documents suggest that the resourc base in Kespukwitk was dwindling. Prominent colonist Nicolas Denys, for example, suggested that New England fishers had destroyed the seal fishery at Cape Sable by the mid-17th century.57 In 1703, Jacques-François de Monbeton de Brouillan, the French governor of Acadie, wrote that the Mi’kmaq “ne trouvent plus a vivre par le moyen de la chasse ce qui fait qu’ils nous tombent souvent sur les bras et nous causent une depence qu’on ne sçauroit Eviter.”58 Although the Mi’kmaq were probably not as needy as the governor suggested, by this time it appears that the growing settler population had begun to put new pressures on the local environment. This change likely contributed to the lower child-woman ratios noted in Port Royal, Cape Sable, and Minas.

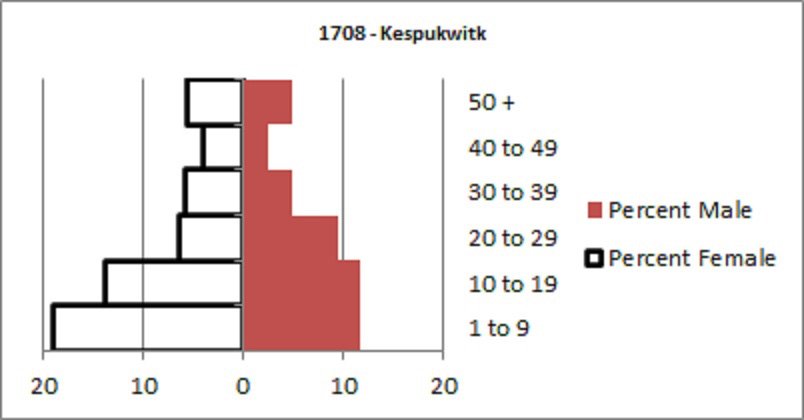

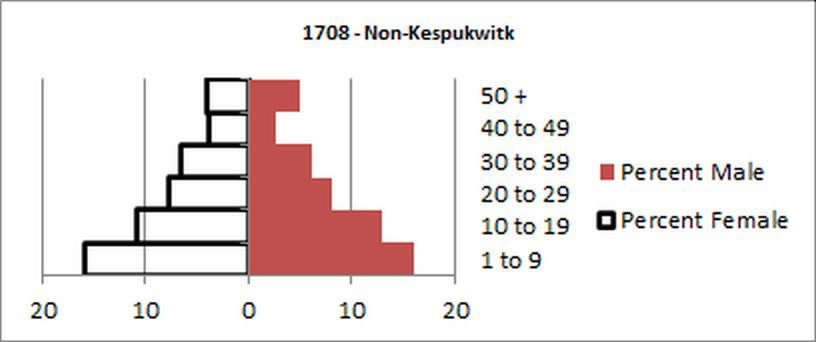

29 Despite the importance of these child-woman ratios, as with all populations, the Mi’kmaw population was influenced more by mortality than reproduction. This can be seen most clearly by transforming the information in the 1708 census into age pyramids such as those in Graph 1 and Graph 2. Taken together, they illustrate that the Mi’kmaq lived in a relatively young society. About 56 per cent of the population was below 20 years of age. This is similar to the nearby Acadian population, for whom about 61 per cent of the population was younger than 20 years of age.59 Adult deaths did not occur evenly between genders. There were more women than men, suggesting that the death of male heads of household often shaped these communities.60 Orphans and widows made up 17.7 per cent of Mi’kmaw society.61 Proportionately, there were about twice as many widows living in Mi’kmaw society than in the neighbouring French community.62 In Kespukwitk, widows comprised about 20 per cent of the population. Although the Mi’kmaq were reasonably fertile, population growth was held in check by an increased incidence of adult mortality.

30 Disease, transmitted by Europeans and their animals, and facilitated by other factors such as migration and declining access to resources, may have also made an impact on the size of Mi’kmaw households.63 Many Europeans commented on this aspect of Mi’kmaw life. During France’s early days in the region, both Lescarbot and Biard noted that disease was prevalent among the Kespukwitk Mi’kmaq.64 Over a half century later, the governor of Port Royal, Louis Alexandre des Friches de Meneval, complained that the fur trade was suffering because many of the best Mi’kmaw hunters had died.65 Rather than warfare or other external factors, disease likely accounts for the high number of widows and orphans in Mi’kmaw society. It slowed Mi’kmaw population growth, and likely limited the size of Mi’kmaw households. Disease, then, did not have a random or general impact across Kespukwitk; rather, the relatively healthy ratio for Pijinuiskaq suggests that poor health – most likely disease – resulted from close contact with Europeans.

31 Warfare also played a role in reducing the size of the Mi’kmaw population. It had a more local effect and seems to have hit Kespukwitk harder than elsewhere. Although peninsular Mi’kma’ki was relatively peaceful during the 17th century, for the four decades before the census was taken the Mi’kmaq had been involved in aiding the Penobscot and Kennebec in their fight against New England encroachment.66 Mi’kmaq from most of the districts participated in this conflict, but Kespukwitk, or rather the waters off its shores, was a key location where the Mi’kmaq and New Englanders came into direct contact. Even during peacetime, the extension of the New England fisheries into Mi’kmaw waters no doubt exacerbated conflict and violence.

32 No additional census information exists for the Mi’kmaq before France’s defeat. Some scholars have suggested that this was a population in decline.67 My evidence does not support this conclusion entirely. With child-woman ratios around one, it is likely that the Mi’kmaw population was growing at the turn of the 18th century. But, when placed beside the Acadian population, the slower rate of Mi’kmaw growth remains striking. Between 1703 and 1714 the French population at Port Royal had nearly doubled from 485 to 895 while between 1708 and 1722 the Mi’kmaw population dropped by four.68 When compared with the Mi’kmaq elsewhere in Mi’kma’ki, lower rates of reproduction and increased frequency of disease and warfare no doubt encouraged the Tewopskik Mi’kmaq to migrate away from the region and minimize their interaction with European neighbours after Britain’s victory in 1710.

33 A consequence of this was that by the 1720s the summer villages at Tewopskik and Pijinuiskaq became more tightly linked. Pijinuiskaq had the highest child-woman ratio in all of Mi’kma’ki, suggesting that the Mi’kmaq there had avoided some of the demographic consequences experienced at Tewopskik and Wipkume’kaqn. By way of the Lequille River, the Tewopskik Mi’kmaq could somewhat quickly reach the Atlantic coast while maintaining access to their traditional land and resources. By living at Pijinuiskaq, they could benefit from more robust living conditions and avoid interaction with the rapidly growing Acadian population and British garrison. By the late 1730s, French intelligence reported that the Mi’kmaw villages of Tewopskik and Pijinuiskaq had indeed formed one community.69 As this French observation demonstrates, living further from the British at Pijinuiskaq allowed the community to continue interacting with the French at Louisbourg, and through itinerant Catholic missionaries, without attracting British attention. In an effort to protect their population and maintain access to important food supplies and trade goods, these Mi’kmaq responded to the challenges posed by Europeans by reducing the amount of time spent near growing colonial and military settlements. Though the Mi’kmaw community around Annapolis (formerly Port Royal) and Lequille did not disappear, this evidence suggests that their use of space shifted away from a more regular presence near the British fort and Acadian settlements. The lower child-woman ratios around Tewopskik and Wipkume’kaqn in the 1708 census suggests that this transition was likely underway before Port Royal fell to the British for a final time.

A reluctant engagement: Mi’kmaw-Acadian relations

34 Within this context, it should not be surprising that interactions between the Kespukwitk Mi’kmaq and the Acadians living around Port Royal were primarily local, kin-based, and informal. Traditionally historians have seen dykeland agriculture as a principal division between the Mi’kmaq and the French. Some scholars argue the division accounted for their positive and symbiotic relationship70; others emphasize that, though the division of land was important in framing the initial relationship between these people, as the French population grew – and Mi’kmaw and Acadian use of space converged – tensions increased and the relationship became more complicated.71

35 It is easy to overstate the points of both convergence and divergence between these societies. Tewopskik was a shared space where some Mi’kmaq and Acadians would have encountered one another regularly, but both populations were sufficiently dispersed that many Mi’kmaq and Acadians did not interact frequently. By 1710 their relationship remained informal; what relationships existed were between individuals rather than communities. Some Mi’kmaq had common interests with some Acadians, while others lived relatively separate lives.72 The variety of relationships between these two communities, where some Mi’kmaq interacted with settlers more frequently than others, added to the diversity of ways that the Mi’kmaq responded to the British arrival in 1710 and helps explain why Indigenous participation in defending the village was primarily a western Wabanaki affair.

36 One way to assess the interaction of the Mi’kmaw and Acadian communities is through the registers from St. Jean-Baptiste Parish, a Catholic parish that included Port Royal. The surviving registers begin in 1702. The Mi’kmaq appear in these documents very infrequently. Of the over 3,500 acts in the registers, only 55 involve a Mi’kmaw person. Of these records, 43 were created between 1726 and 1735 – the high point in Mi’kmaw-British relations before the Acadian deportation.73 Only three baptisms and one marriage predate the British victory.74 At least 97 Acadians and 122 Mi’kmaq, less than half of both societies, were listed in these 55 documents. Though they provide only a glimpse into this relationship, when assessed together they reveal which Mi’kmaq and Acadians were familiar enough with each other to participate in a baptism or marriage together.

37 The parish records between 1726 and 1735 provide the most thorough information on this relationship. A total of 93 Mi’kmaq and 44 Acadians participated in 6.5 per cent of the baptisms, marriages, and deaths in Port Royal during this decade.75 This amounted to about 31 per cent of the Mi’kmaw population and 6 per cent of the Acadians.76 Only 40 per cent (10 of 25) of the Mi’kmaq were from Tewopskik, while 52 per cent (13 of 25) were from Wipkume’kaqn, and 8 per cent (2 of 25) were from Pijinuiskaq. Acadians, most of whose families had lived in Mi’kma’ki for at least two or three generations, usually served as witnesses and/or godparents. Thirty per cent of the settlers were women, while 70 per cent were men. A more even gender balance existed among the Mi’kmaq. Forty-seven per cent of the participants were women while 53 per cent were men. The Mi’kmaq more frequently interacted with French men than women, likely reflecting the patriarchal nature of early-modern Acadian society. Well below half of both populations engaged with each other in these types of religious ceremonies. The long absence from Port Royal of French administrators, who wrote most of the documents that survive from this period, means that there is little direct evidence of interaction between Acadians and the Mi’kmaq from the French period in Mi’kma’ki’s history. If the parish registers are any indication, only a small portion of both societies interacted with each other.

38 But if we take a slightly different approach, and shift our emphasis from the principal participants in these events to a focus on those people on the periphery, who participated as witnesses and godparents, a picture of Acadian and Mi’kmaw social networks emerges. Taking this approach suggests that Mi’kmaw-French ties were maintained through family connections. Indeed, members of the Pellerin, Savoie, and Robichaud families comprised about one-third of all Acadian participants in these records. Although there were some Acadians, including the members of these families, with whom they likely interacted, the evidence from the parish registers, when considered alongside the child-woman ratios, suggests that the collective Mi’kmaw relationship with the Acadians was relatively distant. During this period, it was based more on individuals and families than collective strategies.

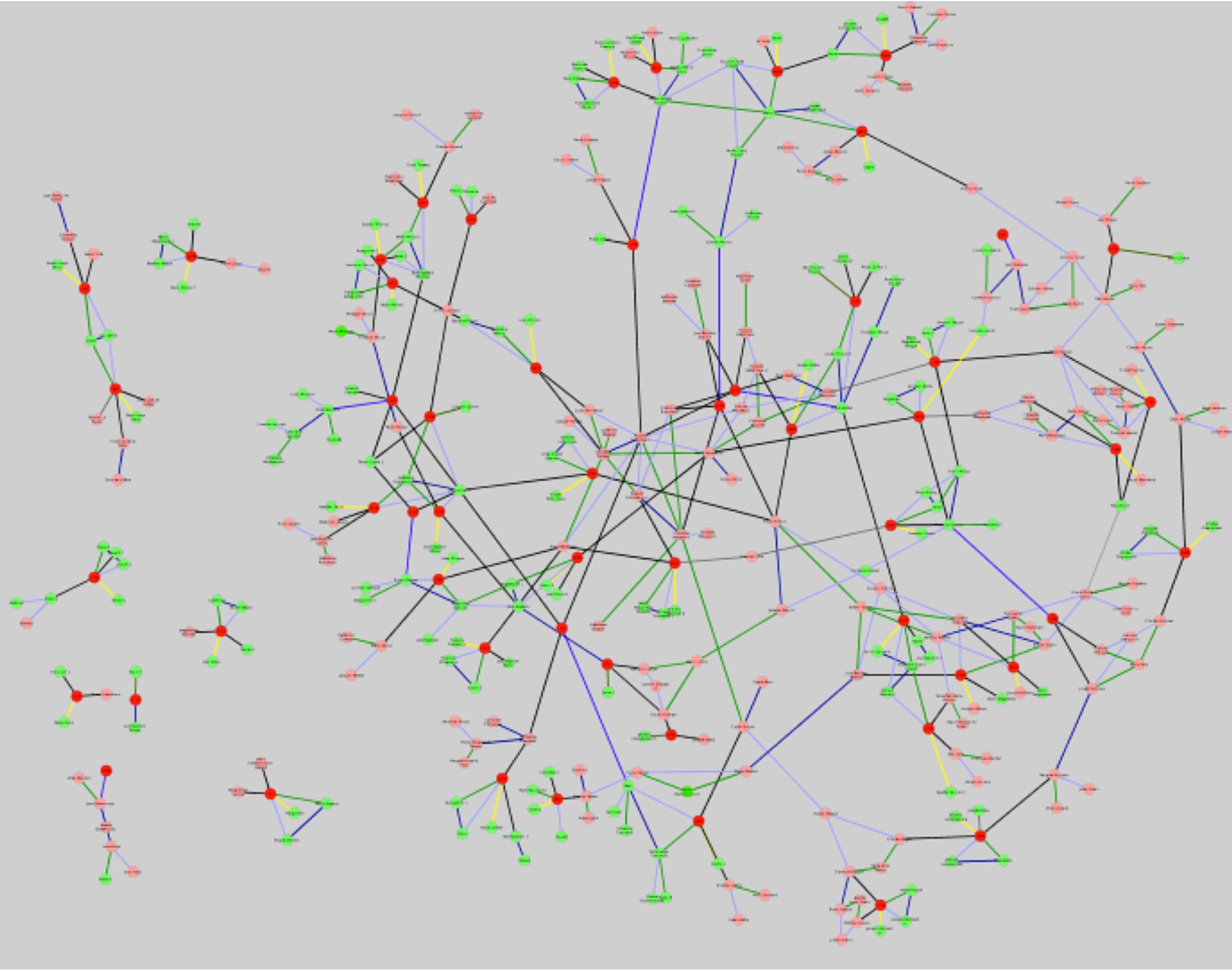

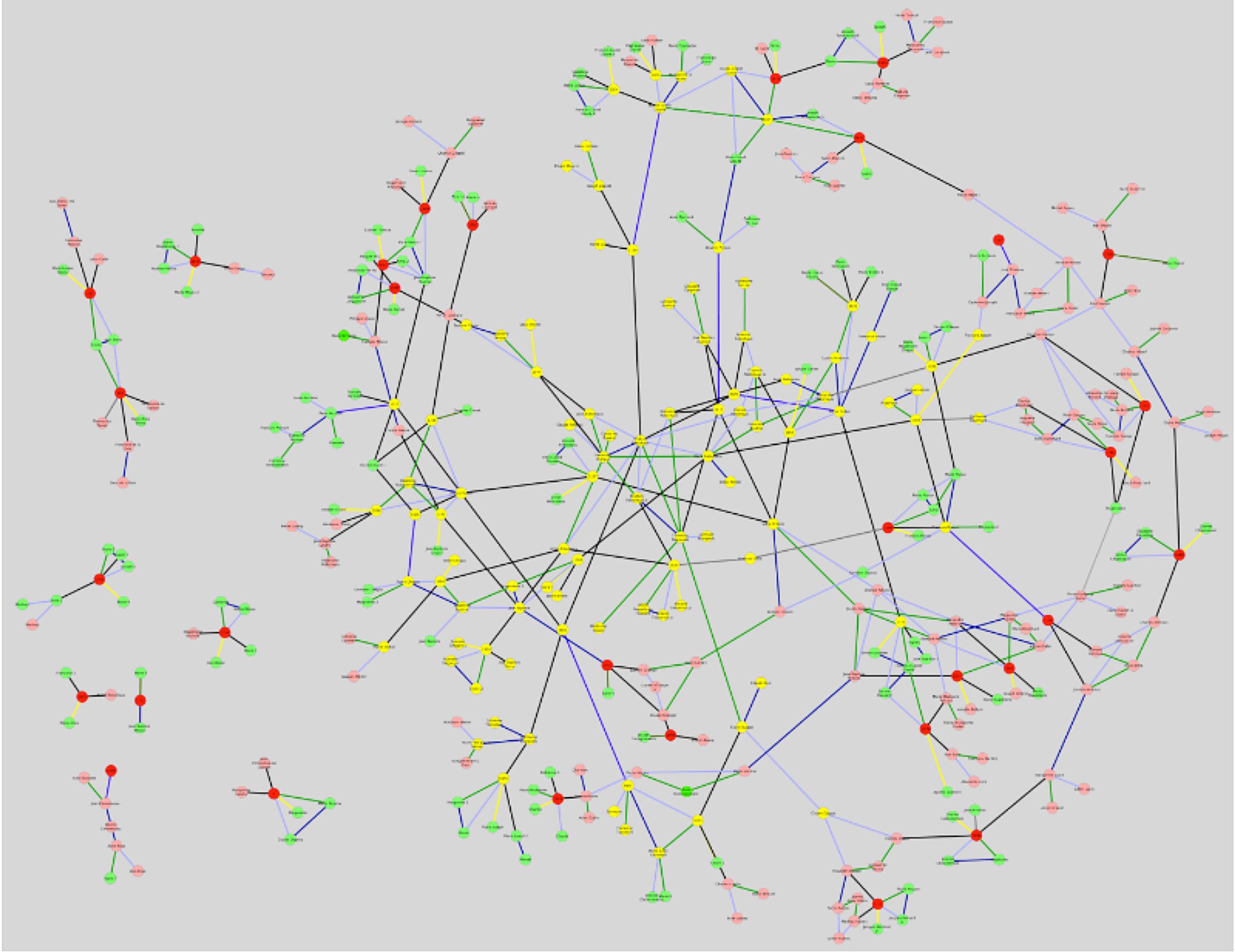

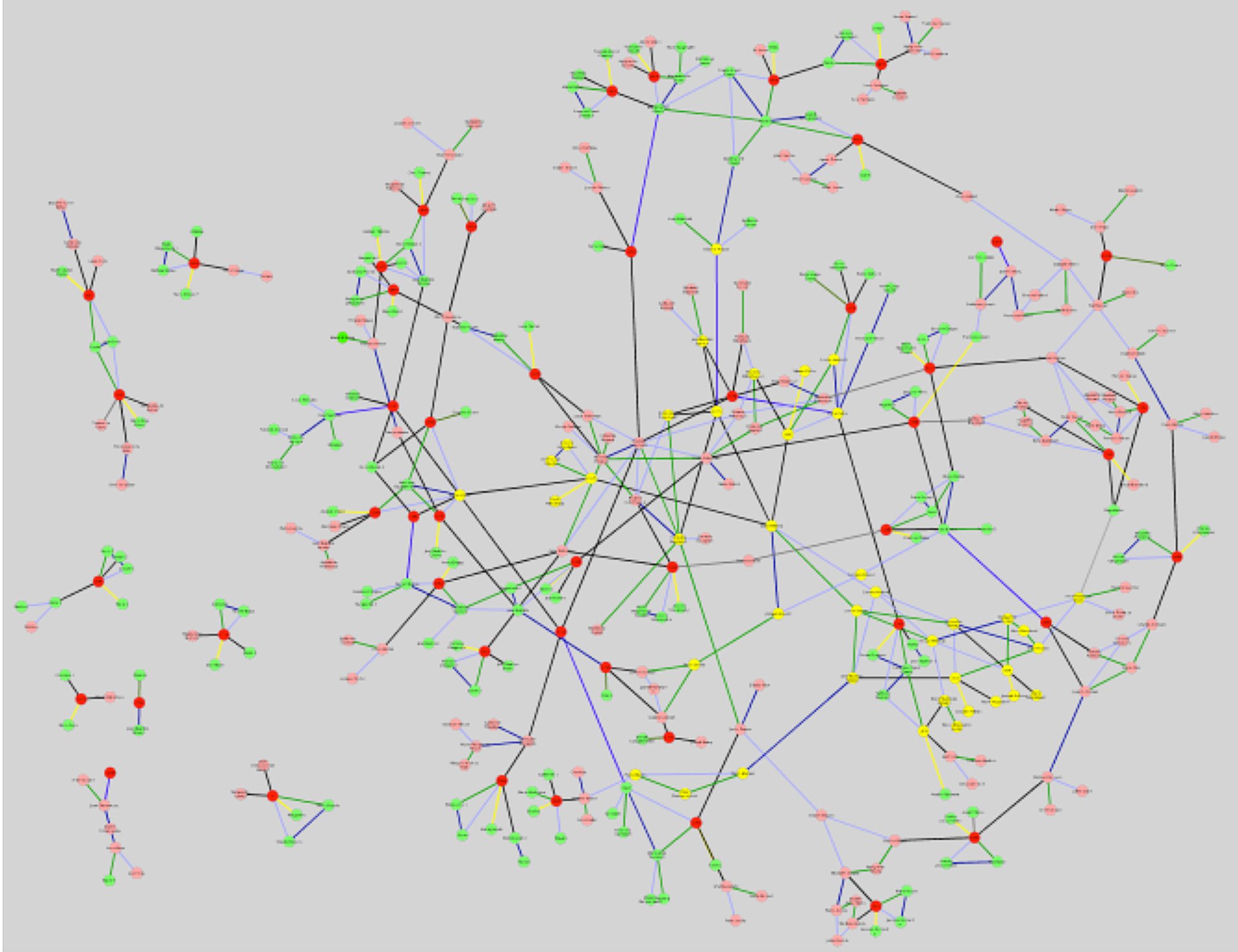

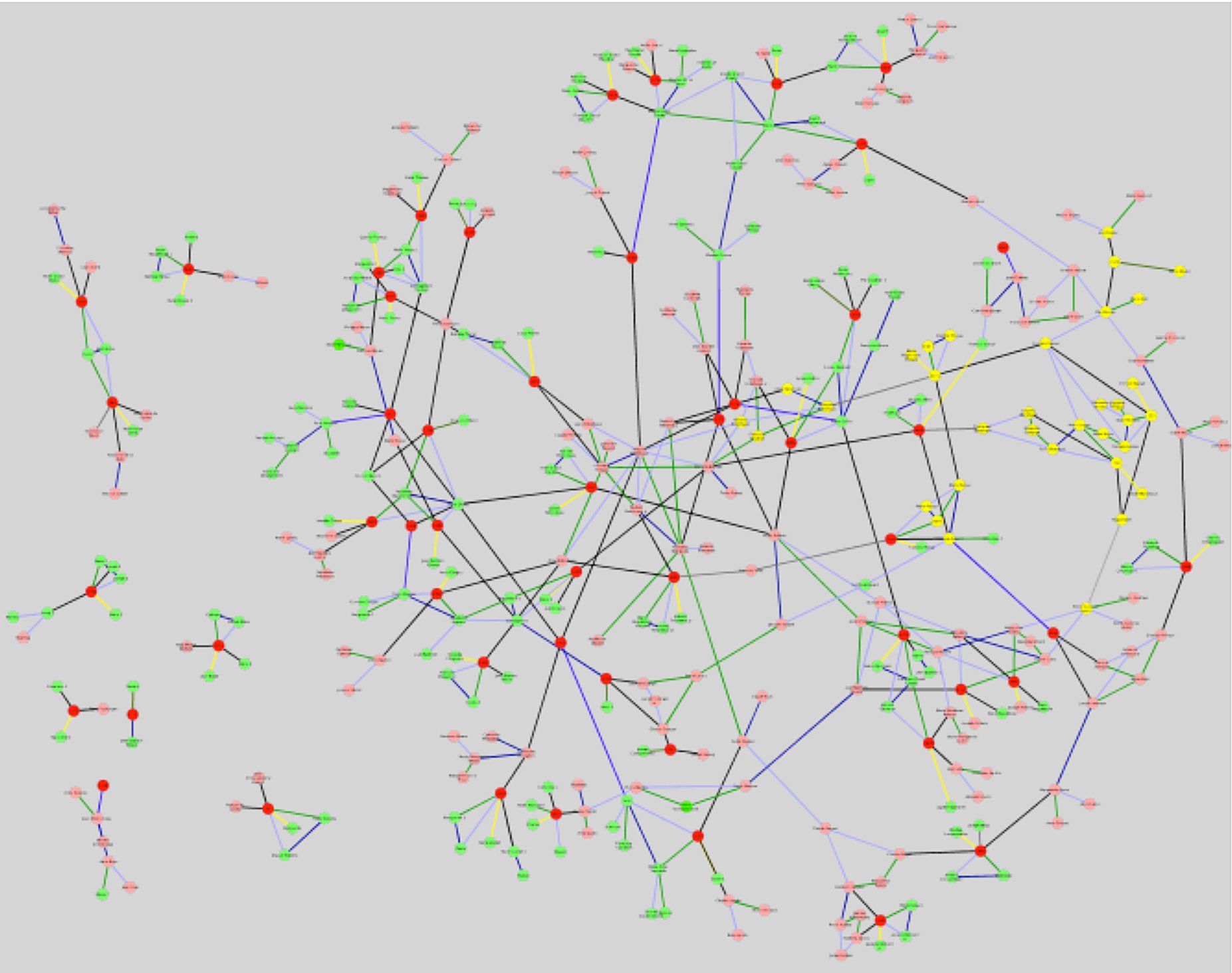

39 In the diagrams below, I have visualized the 55 acts in the Port Royal parish registers in order to demonstrate how the Acadians and Mi’kmaq were connected to each other. Here, the darkest dots signify the acts, the lightest dots represent Mi’kmaw participants, and the remaining dots represent the Acadians [note: in the online version of this article, the diagrams are in colour and red dots signify the acts, green dots represent Mi’kmaw participants, and pink dots represent the Acadians while the lines represent relationships: green connects mothers, purple fathers, yellow baptized children, blue spouses, and black witnesses]. Thirty-eight of these acts involved people who lived in an interconnected social world. When the parents of the Acadian participants are added to this visualization, the interconnections between the acts become even more striking. Now 46 parish records are connected, leaving only 18 Acadians and 26 Mi’kmaq outside of the central network. It is important to recognize that just because most people are located within one large network it does not mean that everyone in this network knew each other. Rather, all Acadians and Mi’kmaq in the network were within one-to-two degrees (that is, they knew someone who knew someone) from a different religious ceremony involving the Mi’kmaq at the Port Royal church.

40 Most of these records are linked by family relationships. The Robichauds were by far the most pivotal family linking these parish records and they were likely the family most closely associated with the Mi’kmaq living around Port Royal. If we look at only dots that are three degrees or less from Prudent Robichaud, the patriarch of the family after the conquest [in the online version these dots are highlighted in yellow in the three last diagrams on the previous two pages], we can see that he was connected to many of the interior relationships in this network. If we look at two degrees of separation or less – that is smaller than what is highlighted below – he was connected to 27 Mi’kmaq and 27 Acadians through 10 acts. These relationships are indicative of the important role Robichaud played as a liaison between the Acadians and Mi’kmaq. Robichaud is one of the few Acadians mentioned in official correspondence as having had a relationship with these people.

41 Although no other family can be as easily and directly linked to the Mi’kmaq, the Pellerin and Savoie families were also over-represented in the parish records relative to other Acadian families. They both had at least five members participate in religious ceremonies with the Mi’kmaq. The Pellerin family, linked on this network through Etienne Pellerin, was connected by 2 degrees or less to 11 Mi’kmaq and 21 Acadians through 5 acts. Importantly, both the Pellerin and Robichaud family lived near the Lequille River. Indeed, if we return to Delabat’s 1708 map, the Pellerin property was located directly across the Dauphin River from the “cabanes” discussed earlier.

42 Germain Savoie connected the Savoie family, through similar relationships, to 9 Mi’kmaq and 21 Acadians through 4 acts. These families were not as distinct as they appear here, however, because this network does not depict sibling relationships. The Savoies and Pellerins were interconnected through Jeanne Savoie, Germain’s older sister and Etienne’s wife. If treated as one family, the Pellerin/Savoie’s had relationships similar to the Robichaud’s. They were connected to 9 acts, 20 Mi’kmaq and 42 Acadians.

43 Taken together, these three family networks connected 33 per cent of the acts in the parish registers, comprising 37 per cent of the Acadians and 27 per cent of the Mi’kmaq involved in these acts. Though they were not overwhelmingly dominant in the parish records, relative to other Acadians at Port Royal these families stand out and this suggests a more sustained relationship.

| Graph | Acts | Acadians | Mi’kmaq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Network | 55 | 160 | 169 |

| Robichaud | 10 | 27 | 27 |

| Pellerin | 5 | 21 | 11 |

| Savoie | 4 | 21 | 9 |

44 Given their overall representation in the parish registers related to the Mi’kmaq, it is not surprising that all three families had deeper connections to people living beyond Kespukwitk. These families, importantly, were just as connected to Wabanaki allies to the west of Mi’kma’ki, a fact that reflects the important influence of the Penobscot on the French during the 17th and early 18th century.77 Etienne and Jeanne’s son François married Marie Martin, the daughter of Pierre Martin and a Wabanaki woman named Anne Ouestuorouest.78 The Robichauds were also connected to the Wabanaki through Francois Robichaud’s wife, Marie Le Borgne de Belisle, whose uncle was Bernard-Anselme d’Abbadie, about whom this article began. The family had other connections to the Mi’kmaq through Prudent’s wife, Henriette Petitpas. Her brother Claude had married a Mi’kmaw woman named Marie Therese.79 Similarly, François Savoie, Germain’s son, married Henriette Petitpas’s niece, Marie Richard, thus connecting them to the Petitpas and Robichaud family.

45 These conclusions confirm what we know from other sources. It is well known, for example, that Prudent Robichaud had a strong relationship with the Tewopskik Mi’kmaq. Twice the British chastised him for interacting with the Mi’kmaq during the early 1720s, and we have already seen the close proximity in which these families lived to Lequille.80 What is more surprising is the light that the Robichauds’ relationship with the British sheds on the Mi’kmaqs’ reluctant engagement in defending French interests in the early years of the 18th century. Despite his censure in the 1720s, Prudent Robichaud was a strong supporter of the British regime. Not only was he the first Acadian to sign an oath of loyalty to the British monarch in 1715, but also, in the years immediately following the British victory, a handful of relatives, including his brother’s stepdaughter, married members of the British garrison.81

46 Given Robichaud’s position between Mi’kmaw and British social and kinship networks – even before the Treaty of Utrecht cemented France’s military defeat – it seems quite possible that the Tewopskik Mi’kmaq were similarly aligned. In fact, in the immediate aftermath of France’s defeat during the winter of 1711, the Mi’kmaq from Kespukwitk came to the fort in an effort to achieve a workable peace.82 Though they never fully welcomed the British garrison, and indeed the late 1710s and early 1720s were marked by warfare against the British at Annapolis, violence related to the imperial regime change that took place in 1710 was relatively slow to erupt. Instead, if the Mi’kmaw relationship to the pro-British Robichaud family is any indicator, the Kespukwitk Mi’kmaq were quite likely prepared to continue as they had before France’s defeat: developing and maintaining local relationships somewhat independent of whichever European power claimed control over their land.

Conclusion

47 Returning to those violent days of the early 18th century, when France was defeated by Britain at Port Royal, a closer look at Mi’kmaw life in turn-of-the-century Kespukwitk helps explain why it was Saint-Castin and his more western Wabanaki kin who sought to defend France’s interests. The ties connecting the Mi’kmaq to the French were weak. Though Tewopskik was the place where France established itself along the Atlantic seaboard, French interests were always westward. Shifting their attention back to Mi’kma’ki in the early 18th century, not enough time had passed before the French defeat for a robust relationship to develop. On the ground – if we might project backwards from the 18th-century parish registers – relationships with the Acadian settlers were most likely pragmatic and localized. Not all Mi’kmaq and Acadians were in the same situation.

48 The sparse nature of evidence about these peoples encourages homogenous generalizations about the Acadians and the Mi’kmaq. But local conditions mattered when it comes to determining how the Mi’kmaq engaged with European settlers and imperial officials. Deeper analysis of these documents suggests that, for the most part, these societies lived apart and that there were only a handful of instances where meaningful relationships were established.

49 Taken together, the 1708 census and the St. Jean-Baptiste Parish registers suggest that caution should be taken when studying this period. Olive Dickason, for example, over-emphasized the importance of Acadian/ Mi’kmaw métissage when she concluded in 1982 that by the 18th century the Acadians were well on their way to forming “one race” with the Mi’kmaq.83 In the 1708 census, Gaulin separated the Acadian and Mi’kmaw communities with little reference to their intermixing. Although there is some evidence of intermarriage – the similarity in Pijinuiskaq’s child-woman ratio to that of the Acadian population at Port Royal might give us pause – there are few French family names listed in his enumeration of the Mi’kmaq. Although the French listed at Pijinuiskaq had Mi’kmaw ancestors, it is not at all clear whether the Mi’kmaq were similarly related.84 In fact, this seems unlikely. Gaulin knew the Mi’kmaq well enough to determine their names, ages, and family relationships (if not their broader social composition). If an Acadian had been living among them at the time of the census, it seems likely that their presence would have been noted. Intermarriage between these communities, as Wicken has noted, existed primarily in the 17th century.85 Its legacy, and likely a continuation of trade, helps explain the existence of the social networks depicted above. The Robichaud, Pellerin, and Savoie families in Port Royal were involved with the Mi’kmaq in a disproportionately large number of religious ceremonies relative to their Acadian neighbours. Although the Mi’kmaq and Acadians generally drifted apart over time, relationships between specific Mi’kmaw and Acadian families continued to link these societies.

50 No single, overarching Indigenous-French relationship existed in Mi’kma’ki. Although some Acadians and Mi’kmaq built important personal and economic relationships, French officials placed greater priority on developing a relationship with the Kennebec, Penobscot, Wolastoqiyik, and Passamaquoddy peoples whose territory further west and across the Bay of Fundy both France and England coveted. Due to their own warfare in New England – and France’s strategic interest in protecting the waterways that led to the St. Lawrence Valley, by using people like the fourth Baron of Saint Castin – these Wabanaki had a much more significant relationship with the French than any Mi’kmaw community. Although the French presented some economic opportunity through trade and military alliance, there was little reason before the British conquest of Port Royal for the Mi’kmaq to interact frequently.

51 In this context, it comes as little surprise that few Mi’kmaq came to Port Royal’s defense when the British attacked at the beginning of the 18th century. Coming to France’s defense would have only exacerbated the challenges that these communities had already started to face. It was not until the late 1710s, after France invested more heavily in Mi’kma’ki at Louisbourg, that the Mi’kmaw-French relationship really began to develop and Mi’kmaw and French military interests began to coalesce.