Articles

Transoceanic Networks of Exchange:

New Brunswick Lumber, Merchant Trade, and the Building of Victorian Britain

Le présent article traite des liens entre le commerce du bois au Nouveau-Brunswick et la construction de villes victoriennes dans les îles Britanniques, en examinant le cas des frères Carvill – trois marchands irlandais engagés dans le commerce du bois et du fer et le commerce maritime des deux côtés de l’Atlantique. Il étudie les relations entre ces diverses activités dans le contexte général d’une ère industrielle. Tout en offrant un aperçu des affaires d’une famille marchande, l’article analyse également les incidences du commerce du bois du Nouveau-Brunswick sur la culture matérielle de la Grande-Bretagne industrielle alors en pleine croissance, en particulier durant la première moitié du 19e siècle.

This article examines the links between the timber trade in New Brunswick and Victorian city building in the British Isles through the lens of the Carvills – three Irish merchant brothers who were engaged in the timber, iron, and shipping trades on both sides of the Atlantic. It considers the interrelationships between these various endeavours within the broader context of an industrial age. While offering insight into one merchant family business, this article also discusses the impact of the New Brunswick lumber trade on the material culture of a growing industrial Britain – particularly during the first half of the 19th century.

1 OVER THE PAST TWO-TO-THREE DECADES, HISTORIANS have increasingly moved beyond conventional provincial or national models of inquiry to embrace broader transnational, oceanic, and global perspectives. The field of Atlantic history emerged from this expansive approach, revealing the rich networks of people, goods, and ideas that were exchanged across the Atlantic oceanic rim.1 These transnational approaches have impacted our understanding of British America by expanding our knowledge of the enormous economic, demographic, social, and cultural ties that connected the British Isles to its North American colonies, especially during the early modern period.2 Dominant themes include the roles played by migration patterns, trade, religion, ethnicity, and class in linking the lands bordering the North Atlantic as well as the political and economic contexts that underpinned those relationships. Our knowledge of northeastern North America, specifically the territory that eventually became Atlantic Canada, has also been enhanced by these broader frameworks. Although the site of economic deprivation during the 20th century, much of this region had previously been an “oceanically oriented marine empire” linked to the wider world through trade and dependent on international markets for industry, identity, and growth.3

2 Despite the substantial influence of the Atlanticist perspective, this methodology is neither new nor radical, as some Canadian scholars had been working in an Atlantic context long before it became fashionable among early Americanists.4 For the Maritime Provinces, situated at the most northeastern extremity of the Americas, geographic location has been a key factor in fostering transatlantic connections, particularly with Europe. The region was dependent on trade with overseas markets, especially the fishing, lumbering, and shipbuilding industries.5 In Newfoundland, the cod fishery was vital to European traders from the early 16th century.6 Scholars have traced the island’s links to the Mediterranean world and beyond, revealing a myriad of connections that impacted migration, trade, and commerce on both sides of the Atlantic.7 In both New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, timber was an important export staple – most notably after 1815 when New Brunswick dominated this share of the market as a major supplier of timber and ships to Britain and the West Indies.8 Neighbouring Prince Edward Island also played its part, and increased shipbuilding and timber exports brought unprecedented economic growth during the same period.9 In these varied ways the Atlantic Provinces supplied important staples to overseas markets, but they also received large numbers of people through the passenger trades.10

3 Immigration into the region increased throughout the 19th century, in particular to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and this is reflected in the population today, the majority of whom are of Anglo and Celtic descent. As in many territories across the British Atlantic it was mostly young, single males who sought opportunities there, the majority of whom made a conscious decision to emigrate in order to better their economic circumstances.11 The Irish were just one of many ethnic groups arriving in British North America during the 19th century, bringing with them their social customs, work practices, language, and folklore while adapting to their new environment.12 Irish merchants played a pivotal role in the transatlantic economy, aided by a growing network of kin and neighbours that reinforced community bonds in the new world while encouraging further migration from Ireland.13 The markedly strong ties between Ireland and the Maritime provinces have been elucidated by a number of scholars, with the Irish constituting the “largest single ethnic group” in New Brunswick during the 19th century.14

4 Despite the impact of the Atlantic perspective on our knowledge of British America, it has had comparatively limited influence on the field of architectural history.15 Scholars have begun to address this lacuna in recent years by uncovering some of the multi-faceted ways the built environment is primary evidence for exchanges in migrant labour, knowledge, and material culture between Britain and North America.16 Of particular relevance is Daniel Maudlin and Bernard Herman’s 2016 volume, the first overarching work of scholarship to address the subject of architecture and urbanism across the British Atlantic world.17 The book analyzes a range of built forms and spaces in a number of diverse locations, including the eastern seaboard of North America, the Caribbean, West Africa, and the British Isles. Valuable and compelling though all of the above studies are, the focus is mainly on the outward flow of ideas and influence from Britain to different Atlantic locations – especially during the early modern period. Little attention, however, has been paid to the reverse flow – the impact of Atlantic culture on the architecture of the British Isles.18

5 Within the context of this historiography, this article links the export of New Brunswick timber to Victorian city building in the British Isles by examining the contribution of three Irish merchant brothers and their engagement in the transoceanic trades during mainly the first half of the 19th century. It investigates the interrelationships between the various strands of their businesses at home and abroad, following the exchange of timber and ships for a range of manufactured goods. At their peak, the Carvill merchants managed a lucrative operation that included 35 ocean-going vessels as well as a prosperous trade in timber and other goods between Europe, North America, and beyond. The most notable feature of the firm was its broad geographical reach, which was not only trans-Atlantic in scope but also imperial: its ships sailed not only to the West Indies but as far as the Indian colonies and Southeast Asia. Although its engagement in the timber, passenger, and shipping trades is paralleled in other studies,19 its expansion into land speculation and church and house construction on both sides of the Atlantic reveals an impressive strategy of business pluralism in which expanding diversification was part of risk management. Finally, this examination of the complex and far-reaching economic networks of the Carvills provides fresh insight into the substantial impact of New Brunswick’s transoceanic lumber trade on the construction industry in Britain and (especially) Ireland.

From Ireland to British North America: the early years of the Carvills, 1800-1849

6 Francis Carvill was born into a large Catholic farming family c. 1800 in the Mourne area of County Down, in the northeast of Ireland.20 He first appeared in the directories at the age of 26, operating as an ironmonger and hardware man in the port town of Newry. Within a few years, Francis had taken over the extensive iron mills there, where he manufactured spades and shovels for distribution to the surrounding towns.21 By 1836 he was involved in the passenger trade: he advertised space on a new ship that would sail from Newry to New Brunswick that year, claiming it to be “a most desirable Vessel for Emigrants.” The vessel was only six months old and had recently landed a cargo of “first quality” timber from New Brunswick, which was offered for sale in Newry. Francis Carvill announced that he was also awaiting the arrival of six other ships, bringing timber from Quebec and Memel, and iron from Wales and Scotland.22 His younger brother William had emigrated that year to Saint John in New Brunswick, the province’s chief port and primary centre for mercantile trading. Another younger brother George followed in 1844; as young men they were engaged in the iron, timber, and shipping trades in the city.23 It is likely that William and George had served their apprenticeships with their older brother in Newry, and then set sail across the Atlantic to establish the North American side of the business. Like other emerging immigrant merchant families, the Carvill brothers forged new opportunities on foreign soil while maintaining strong connections with industry at home.24

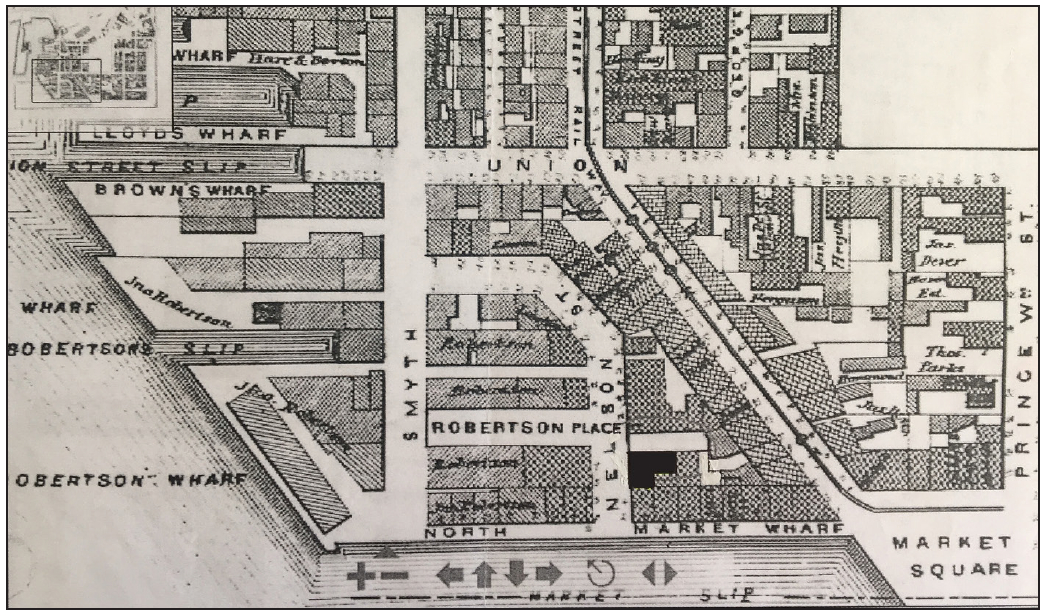

7 Initially, William Carvill had focused on shipping goods directly from his home port town of Newry in Ireland. In the spring of 1837, though, he was advertising the arrival of a cargo of Irish foodstuffs, including 16,000 gallons of potatoes, 20 barrels of pork and quantities of butter, flour, and oatmeal that could be purchased directly from the vessel. In addition, he was selling 60 containers of “Swansea coals, for Smiths’ use” as well as 400 firebricks and 12 casks of fire clay destined for the foundries. The shipment included many metal products: there was an assortment of iron in the form of 4,570 bars and 310 bundles, 312 locks, and 70 tea kettles as well as wrought iron nails, chains, tin plates, 600 spades, and 6 bundles of blister steel.25 While some of this cargo likely came from his brother’s mills in Newry, most of it was sourced from different parts of the United Kingdom – a reflection of the city’s links with other trading ports, particularly on the west coast of Britain.26 Within three months William had landed another shipment from Newry, which included 100 tons of the “best No. 1 Scotch Pig Iron,” 35,000 bricks, and 400 bushels of barley. Scottish pig iron was a staple in the North American trade: it paid good freight and was known as useful ballast.27 The cargo included chains, spikes, tin plates, and 20 tons of assorted iron as well as ship winches, canvas, and sail twine, much of it destined for shipbuilding use.28 By 1838 William Carvill had established premises on Nelson Street in the Kings Ward area of Saint John, the heart of the city’s Catholic community (Figure 1).29 The street was characterized by iron stores and warehouses and was located just behind the North Market Wharf, where schooners and brigantines lined up laden with produce. William offered English, Scotch, and Swedish iron at his warehouse that year, recently arrived on a shipment from Newry, as well as 100 chaldrons of coal from Liverpool30 and a large range of metal products – from forge bellows to anvils and shovels and from sheathing copper to sheets of brass.31 It is likely that some of these goods were acting as ballast: various products, from iron shovels to coal to rock and sea salt, were often used to provide stability to ships.32

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

8 By 1842 the Carvill store on Nelson Street was well stocked with refined and common iron, German steel, stoves, grates, and pots in addition to farmers’ spades and miners’ shovels. Although metals were the core of the Carvill import business, they also stocked the “best Liverpool soap,” American flour, and Irish malt whiskey.33 During the 1840s, William’s advertisements increased: he imported oakum from London and iron from Staffordshire, Bristol, Liverpool, and the Clyde.34 He also received goods on consignment, such as the supplies of tobacco and gunpowder tea that he imported from New York and the cases of Irish linen that landed from Newry.35 The variety of these imports were clearly a response to localized domestic markets. As Douglas McCalla has shown for Upper Canada, settler families were reliant on a wide range of purchased goods bought in local stores that had for the most part been imported from the United Kingdom.36

9 After the depletion of homegrown forests by the middle of the 17th century, Britain began to rely increasingly on foreign supplies of timber. Most of this was sourced in the Baltic Sea region of Northern Europe, while North American timber made up a relatively small share of British imports. However, during the first decade of the 19th century, political tensions in Europe marked a sea change for the wood industry in British North America. By 1808, two years after the Napoleonic blockade, Baltic supplies had plummeted and Britain was importing 70 per cent of its timber from its British North American colonies (compared to just 1.3 per cent in 1800).37 The following year the British government increased import duties on all foreign timber, largely ensuring Britain’s reliance on Canadian markets for decades to come. These changes had a dramatic impact on the timber market in British North America, which coincided with the rise of industry in Britain. Between 1801 and 1851 more than 1.9 million houses were built in Britain to cater for a booming population, leading to an exponential growth in the demand for timber.38 The arrival of the railway also created an unprecedented demand, with over 1,700 sleepers needed to lay each mile of track – “sleepers” are the timber boards on to which iron rails are laid – as well as the large quantities required to furnish carriages and to build new railway stations. Forests 4,000 miles away, therefore, became the source for Victorian church timbers, warehouses, ships, and railway infrastructure in a growing industrial Britain. New Brunswick was strategically placed to benefit from these developments. Bordering the Atlantic Ocean, the region was equipped with a large river system that enabled exploitation of its extensive pine and spruce forests. Exports of ton timber multiplied almost twentyfold between 1805 and 1812, and increased over four times as much by 1825. The port of Saint John became increasingly important as a centre of trade – a deep-water port that stayed ice-free all year long.39

10 When William Carvill landed in British North America in 1836, he found a booming urban economy in Saint John where, over the following five years, there was a substantial expansion of industry in the city.40 The 1830s was particularly significant in marking the transition from ton timber (balks of wood hewn square) to lumber (processed wood). This led to the building and expansion of saw mills, and the quantity of deal41 exports from Saint John almost tripled in that decade from 30 to 80 million feet.42 During his initial years in the city, Carvill capitalized on this new market demand. In 1838, a year of increased timber exports due to a spurt of railway building in Britain, he placed two notices in the local newspaper: one to purchase 500,000 superficial feet of deals, and another to charter a vessel to carry a cargo of deals to an unspecified port in Ireland.43 As his ships were returning mainly with iron goods from Britain, he could exchange some of these as part payment for the timber as other merchants were doing.44 By the late 1830s, he was just one of the many merchants exporting local timber from New Brunswick and importing metal goods and other products from the United Kingdom.

11 In 1841 the British timber market collapsed, leading to an economic crisis that ripped through the Saint John economy.45 That year public meetings were held in the city to petition Queen Victoria against the proposed removal of duties on Baltic timber, which had protected the colonial lumber market since the Napoleonic blockade.46 By 1842, although timber exports from the province were falling,47 Carvill continued in the trade; by the end of that year, he was offering 600 tons of white pine for sale as well as 200,000 superficial feet each of pine boards and deals.48 William’s younger brother George arrived in Saint John in 1844, where he worked in his brother’s iron store on Nelson Street. Within two years, George had taken a leasehold interest in a saw mill along with two other lumber manufacturers a few miles further up the St. John river at Milford in Lancaster.49 The mill was one of a number operating in the area; deals sawn here usually travelled down the river in small boats, where they were delivered at the city wharfs for reloading onto ships.50 From the mid-1840s, however, colonial lumber became increasingly under threat from foreign markets. By 1848 the trade in New Brunswick had been reduced by two-thirds, leading to an exodus of about 5,000 people from the province.51 This was further compounded by the repeal of the Navigation Acts in 1849, which meant that colonial traders were now competing directly with American markets. These changes had an impact on the timber trade in Liverpool: that year there was a reduction in supplies of pine from Saint John of nearly 10,000 logs compared to the previous year.52

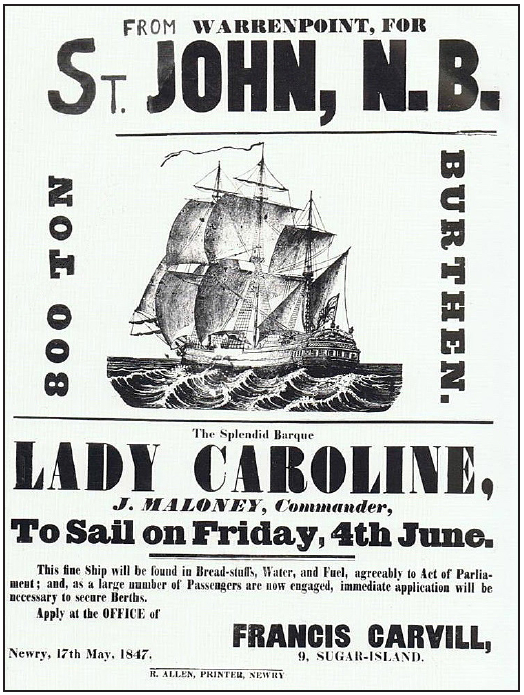

12 The trans-Atlantic networks of the Carvills also extended into the realm of emigration and settlement. The eldest brother Francis had introduced shipbuilding to the town of Newry in 1845 by launching the vessel the Mary Anne from his building yard on Merchant’s Quay.53 By this time he had a range of enterprises, dealing as an “iron merchant, hardwareman, spade, shovel manufacturer, timber and slate merchant.”54 He operated from two premises: one on Merchant’s Quay and another at Sugar Island, the latter of which included a sawing and planing mill, a spade and shovel factory, and a weaving factory – all powered by a “modern steam plant.” During the worst years of the Great Irish Potato Famine Francis remained the main emigration agent in Newry, securing passages on numerous vessels between Ireland and North America.55 An example is the 1,000-ton vessel named the British Queen, advertised as a “superior copper-fastened, fast-sailing packet-ship” that would set sail from Warrenpoint to New Brunswick in 1846.56 The vessel, he claimed, was “very spacious and lofty,” well-ventilated, and equipped with “Breadstuffs and Water” and suitable for emigrants to Saint John or Boston. The trans-Atlantic voyage was often perilous, and many ships made the journey only once during the Famine period. However, Francis Carvill’s ship, aptly named The Brothers, made a voyage every year from Newry to New York – a total of ten Atlantic crossings during the Famine era.57 In New Brunswick William Carvill also offered space for passengers on ships to ports in Britain and Ireland, such as the “fast sailing ship” he promoted in September 1843 – soon to set sail direct for Newry with “excellent accommodations for Cabin Passengers.” Working as a commission agent, he was offering space on another of his ships three years later, where a few cabin passengers could be “comfortably accommodated” on a voyage to Liverpool.58 Thus the Carvills do not appear in the records as operators of the disease-ridden and overcrowded “coffin ships,” so often a feature of Irish Famine literature (Figure 2). Rather, their involvement in the passenger trades was a logical extension of their role as trans-Atlantic merchants – particularly during times of mass emigration.59

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

13 Like many of their fellow North American traders, many timber merchants were also investors in shipping in Saint John.60 With a product destined mainly for ports in Britain and Ireland, these timber merchants could increase profits by selling both cargo and ship on arrival.61 New Brunswick vessels, constructed with local materials and built more cheaply than in Britain, were in great demand there despite the costs and risks associated with the trans-Atlantic voyage. William Carvill was first recorded as a ship owner in 1836, the year of his arrival in New Brunswick, when he launched a schooner of 70 tons.62 Over time, his vessels increased in size. During the 13 years that he spent in British North America, William invested in at least 14 ships; he was the sole owner of at least four of these, and shared ownership with the remainder. The majority were sold within a year or two of their launch, probably to minimize the risks associated with the trans-Atlantic voyage. Most of the ships were sold either in Newry or Liverpool, with a few in other ports in Scotland and Ireland. These were all locations of the main purchasers of British North American vessels.63 Even after sale, William continued to trade goods in some of these ships: an example is the 730-ton vessel, the New Zealand, which he launched in February 1842 but sold it in Newry 17 months later.64 Within two months William was announcing its return to Saint John, laden with a cargo of iron and tin from Liverpool.65 The New Zealand demonstrates the Carvill family’s links with kin networks in Saint John: it had been built by James T. Smith, a shipbuilder originally from Monaghan in Ulster (not far from Carvill’s home county). Smith had emigrated to New Brunswick in 1819, where he cut timber before working in the shipyards of Saint John.66 Furthermore, at least five of William’s vessels were built by the Ruddock family from Kinsale in Ireland, who were major shipbuilders in the city.67 An example is the vessel they built for him in 1847, the Loch Steoy, which was claimed to be a “very superior and splendid coppered ship” and “equal, in point of model, materials and workmanship, to any vessel ever built at this port.”68 William and George also invested in ships together. They were joint owners of the 871-ton ship, the Charles Chaloner, which, in 1846, made its maiden voyage to Liverpool that year, probably with a cargo of deals. The ship returned to New Brunswick with ballast in November, and set sail again for Liverpool nine days later, where it was finally sold the following year.69 The Carvill brothers were not the only owners of this vessel as they shared it with two merchants – Edward Chaloner and Quinton Fleming – eminent timber brokers in the city of Liverpool and thus attracting buyers from all parts.70 The city was the chief lumber port of the British empire, and Liverpool merchants dominated the British timber trade.71 As importers of iron and other products from Europe, and exporters of timber and ships from North America, the Carvills had by this time laid the foundations of a successful trans-Atlantic merchant firm, with respectable international connections.

William Carvill’s return to Ireland: 1849-1870

14 1849 was a tumultuous year in Saint John, which saw two fires in the city and some of the worst ethno-religious riots in New Brunswick’s history; clashes between Irish Catholics and Protestants killed at least ten people.72 William Carvill returned to Ireland that year, his home country still grappling with the fallout from the mass disease, starvation, and emigration of the Famine years.73 Leaving his younger brother George in charge of the business in Saint John, William travelled to Dublin and married into a prominent Catholic merchant family the following year.74 As part of the marriage settlement he acquired a number of landholdings, including 21 acres in Rathgar – a growing suburb adjoining the city.75 While making a new life in Ireland, though, William continued to collaborate with his younger brother George in British North America. In January 1850 they changed the name of the firm to “William & George Carvill,” a partnership that would last for another 19 years.76 Saint John began to recover from the commercial difficulties of the preceding years, and there was a substantial growth in business in the city from 1851. The Carvills continued to export lumber to Dublin and their ships returned mainly with cargoes of iron, which would help supply the “important and heavy manufacturing interests of St. John and the province” for many years to come.77

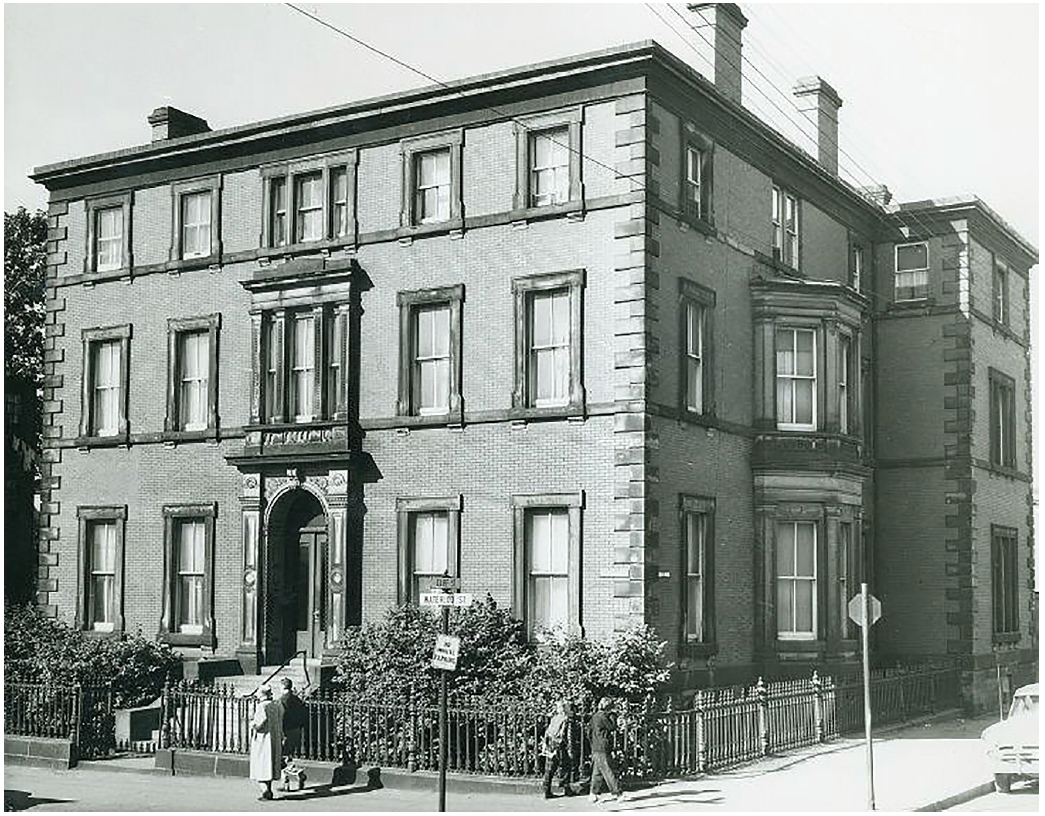

15 When the elder Carvill brother Francis died in Newry in 1854, he was hailed as the largest employer and the most extensive trader in the port.78 The business was taken over by his son, and within a few years William and his nephew were advertising the sale of two vessels that had recently arrived in Dublin from New Brunswick. In October 1857, for instance, they announced the landing of the barque the Emerald Isle, which had been launched the previous month in Saint John and was described as a “beautiful New Clipper Barque” – a fast sailing ship that had travelled to Ireland in just 22 days.79 A brigantine was also for sale: built for private use the previous year in Saint John, it has since been upgraded with new masts, spars, sails, rigging, anchors, and chains.80 That same year a Newry newspaper reported the launch of a “splendid ship of about 1,000 tons burden” from a building yard in Saint John, called the William Carvill, “after one of our enterprising merchants.”81 This ship was owned by William’s brother George, and would set sail from Wales to Calcutta in 1861, making the 7,726-mile voyage in just more than four months. It continued to trade in the ports of Ceylon, Mauritius, and India over the next two years, and was mastered by a George Copeland, from Warrenpoint in County Down. Joseph Seeds of Dublin took over this ship in 1865, and sailed it from India to Yemen, and onwards to Burma over the next few years, until it was finally sold in Dublin in 1872.82 Clearly, by this point, the Carvills had extended their horizons from the trans-Atlantic merchant trade to operate in other British colonial territories bordering the Indian Ocean.

16 The 1850s was a time of increased building activity in Dublin city, as improvements in transport and communications solidified its place as the capital of business and commerce in Ireland.83 By 1853 William had established himself as a corn merchant in the city at the centre of the timber trade, at a site on Sir John Rogerson’s Quay.84 The capital was in the process of transformation, as speculators began to carve out new roads in the newly emerging suburbs outside the city boundaries. William took possession of his lands in one of these districts that year – a 21-acre site straddling the Dodder River in Rathgar – consisting of an assembly of structures, including a mill-race, a calico mill, and a medium-sized house (Figure 3). By 1857 he had converted the existing industrial structures to a saw mill and advertised the arrival of a number of shipments of timber that year, including 500 tons of pine and birch timber from Saint John.85 On arrival in Dublin, some of this was auctioned off at his premises in the city while the remainder went for processing at his “Rathgar Saw Mills.”86 Due to a post-Famine rise in construction activity, timber imports had been rising in recent years so that by 1859 Dublin imported almost twice as much lumber as Belfast.87

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

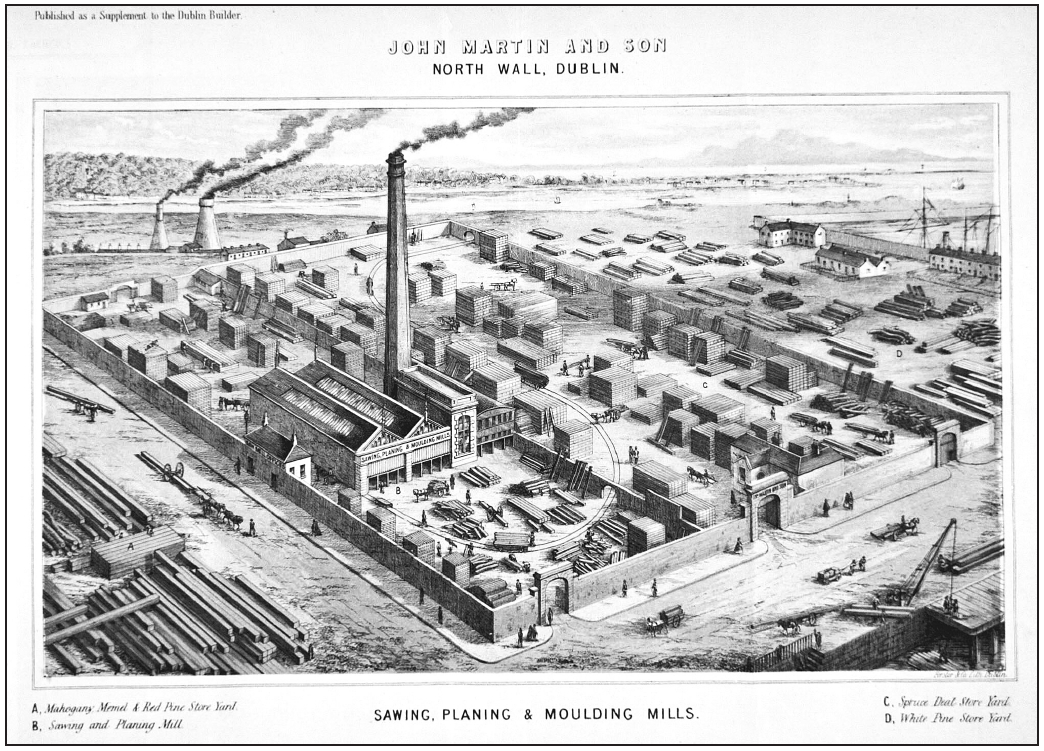

17 Much of this timber provided the raw material for the city’s busiest period of domestic construction. The 1860s was a time of a flourishing of the building trades, as Ireland benefitted from Britain’s mid-Victorian boom and a post-Famine economic upturn. This is reflected in a report from the Dublin Builder in 1860, which predicted a busy building season as it boasted: “Our suburbs are extending, green fields are metamorphosed into populous districts . . . “bustle” is the word in every quarter, and the welcome sounds of the hammer and trowel are met at each step.” By 1862 there were eight saw mills in Dublin, most of them operating from a wholesale yard on the quays where new steam-powered machinery manufactured doors, sashes, and mouldings faster and cheaper than ever before. Timber merchants advertised in local newspapers, announcing the arrival of red deals from Norway as well as white American oak and red pine from British North America, Mexico, and Russia; much of this went to fuel the housing boom.88 Martin & Sons were Carvill’s competitors: they advertised alongside them in January 1859, promoting “several Cargoes of North American and Baltic WOOD GOODS at the Custom House Docks. The firm had recently erected an extensive sawmill at North Wall Quay, which was illustrated by the Dublin Builder the following year (Figure 4). The drawing demonstrates the potential scale of such an operation, where a labyrinth of yards stored a wide variety of timber; the saw mill was central to the complex, where planing and moulding machines manufactured sawn timber including railway wagons and furniture. Nearby, a timber wharf was being extended on a continuous basis to cope with the increasing loads of timber imports to the city.89

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

18 From the late 17th century, fire prevention laws ensured that the majority of houses in Britain and Ireland would in time be faced with either brick or stone.90 Behind every masonry façade, however, was a supporting structure of timber, including floor and ceiling joists, roof rafters, and trusses. The material was also used to build internal partitions, staircases, doors, windows, moulded archways, skirtings, and furniture. It was, therefore, a key raw material in the domestic construction market, equalling, on average, about 30 per cent of the total cost of a house.91 A standard terraced house required several kinds of wood: in Dublin one specification stipulated “picked red pine” for the windows and external doors, and “Norway boards” for the floors. Pine was used for all building purposes, but in a typical house it was often used to form bearing timbers, external windows and doors, staircases, and flooring. In the early years white pine was in plentiful supply in New Brunswick, producing logs of up to 80 feet in length, but there was a gradual changeover to spruce when pine supplies began to deplete.92 Spruce was also used for inferior forms of carpentry, such as floor joists, studding, and rafters, and as a cheaper flooring finish.93 William Carvill was importing both types of timber into Dublin in the 1850s: he landed a cargo of “St. John Pine” and white and red pine from Quebec in 1857, but over the following years he also imported large quantities of spruce.94 The cargos usually arrived already sawn into deals, planks, and battens, which were various sizes of processed timber used mainly for house construction.95 William offered a higher price for the nine-inch deal, and this was used for the simplest form of floor construction in Britain, consisting of boards fixed to a series of joists spanning from wall to wall, without the need for intermediate support.96 In partnership with his brother in New Brunswick, William Carvill continued to import large quantities of timber from British North America; but his trade expanded over the years to include mahogany from the West Indies and “Memel timber, plank and Lathwood” from the Baltics.97 Mahogany was used for hardwearing surfaces in houses, such as door saddles or handrails, and for high quality joinery and cabinetry. Lathwood – narrow strips of wood used as an underlying framework for plaster ceilings and walls – was another important component in house construction. Carvill also landed quantities of elm and oak timber from Quebec, used mainly in the shipbuilding industry, and Saint John birch, which was used mainly for furniture and ornamental purposes.

19 By 1854 Britain’s gradual reduction in protectionist policies had finally tipped the balance away from colonial timber markets. By 1861 the most common timber used in Britain was sourced mainly in the ports of Northern Europe, providing “the best balk timber for construction carpentry, and the finest deals for the finishings of the joiner.”98 When all duties on timber, both foreign and colonial, were finally lifted in 1866, it further shifted the balance in favour of European sources of lumber.99 Although British North American lumber no longer represented the bulk of timber imports to Britain, it was still known for producing “excellent” woods. In 1866 the Dublin Builder reported that British North American white, red, and yellow pine was still in demand in European markets due to its superior quality and size.100 To further complicate matters, Canadian pine timber was reportedly mixed up and sold as Baltic pine, as it was only slightly paler in colour than its Northern European equivalent.101

20 With a ready supply of labour and materials sourced at cost, timber merchants often engaged in construction as an extension of their normal business operations. By 1865, for instance, William Carvill was keen to play his part in the house-building boom in Dublin and began to speculate in building around his home in Rathgar. Between 1865 and 1870, he laid out 2 new streets and built 18 semi-detached houses: numbers 1-14 Rostrevor Terrace (after his home town of Rostrevor, County Down) and numbers 2-6 Orwell Park. Rostrevor Terrace is grand in scale, consisting of a series of wide, semidetached homes clad in red brick and set back behind generous front gardens (Figure 5). These houses were a means of amassing wealth and financial security: although some of the Carvill dwellings were sold, the majority were retained as lucrative rental properties, and/or absorbed into the marriage settlements of his children.102 Behind these relatively austere facades are richly decorated interiors, complete with cornicework, foliated ceiling roses, and delicately carved timber stairs. With the majority of Carvill’s shipments coming from British North America, it is likely that the timber supporting these ceilings and floors, before being nailed into place in Dublin’s Victorian suburbs, passed through the hands of lumberjacks and sawyers, shipwrights, and merchants 4,000 miles away across the Atlantic Ocean. Now some of the city’s most highly valued structures, these houses are therefore the products of exodus and enterprise – exodus to a New World to benefit an old one – all the while facilitating one family’s rise to nouveau riche status.

George Carvill remains in British North America, 1849-1884

21 After William’s return to Ireland, George acted as agent for his brother and he sent his ship the Catherine to Liverpool in 1849 to be put up for sale. In return William sold a number of George’s vessels, such as the Francis Carvill, named after their deceased older brother, which he sold in Liverpool in 1863.103 George continued to invest in ships, the majority of which were sold within a few years of their launch in various ports in Britain or Ireland.104 Clearly, it was a risky business: of the 21 ships that George invested in, six were lost at sea. An example of this was the Dundalk, which was sent to Ireland for William to sell in 1860. After failing to find a buyer it was returned to Saint John, from where it subsequently left for a voyage to Cuba in 1863 and was never seen again.105 Another recorded loss was the Maggie Chapman, which was launched from Saint John in 1868 but abandoned on a voyage from Philadelphia to Antwerp in Belgium 10 years later.106 The most dramatic case, however, was the loss of the Eblana, a vessel of 650 tons built in Saint John in 1868 for George Carvill. For 12 years this ship carried deals across the Atlantic, returning mainly with coal as ballast. Known as an “ocean racer,” by 1880 it was reported to be one of the fastest vessels in the port of Saint John having raced several times across the Atlantic along with another of George’s ships. 107 Whereas most vessels made the voyage to Britain in 25 to 30 days, the Eblana took only 16. On its return to North America in January 1880, with a cargo of 400 tons of coal, it was shipwrecked 12 miles off the coast of Saint John, with the loss of ten lives.108 Although shipwrecks were not uncommon, the extent of fatalities suffered here appears to have been significant. The news reached newspapers in Boston and Montreal, and the reports all lamented the loss of Captain Barry, his first mate, six sailors and a woman and her 3-year-old son.109

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

22 Like many merchants in the city, George Carvill began expanding into land speculation by acquiring property in the Saint John Harbour area.110 The first record of this is in 1850, when he sold a 10-foot wide plot fronting on to Waterloo Street in the Wellington Ward area.111 By the following year he appeared in the census as a 30-year-old single man, living in a house on the same street along with three servants who were all of Irish descent.112 Within two years, however, he had married Margaret Lucinda Fogerty at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, the daughter of an Irish lawyer from that city.113

23 George continued in partnership with his brother William in Ireland, shipping lumber mainly to the port of Dublin and importing iron into the province.114 They also continued in their capacity as co-owners of the saw mill in Lancaster; in 1852 the brothers were among those campaigning for the extension of the port of Saint John to facilitate the transport of lumber from there.115 From the store and warehouses at Number 4 Nelson Street, the firm sold a range of metals: from bar, sheet, and pig iron to tin plates, spikes, and anchors and chains as well as different forms of steel (cast, german, spring, and blistered). The best makes of anvils, vices, and bellows were available for blacksmiths’ use, in addition to patent metal for the making of ship’s bolts.116 William and George also operated as commission agents for a shipping line from Ulster. Between 1851 and 1856 they placed several advertisements in the New Brunswick Courier, appealing to locals who wished to engage passages for their friends on the “first Spring Vessels.”117 The firm was only one of several agents operating on these ships, as evidenced by the passenger list for the ship the Mary Ann. Sailing from Derry in Ireland to Saint John in June 1856, only 31 of the 158 passengers had booked through W. & G. Carvill while the remainder had bought tickets through other agents.118 In 1862 W. & G. Carvill confirmed that they had been operating as commission agents on this line for over 30 years, claiming they had been “singularly fortunate, as during that long period it has met with no disaster and not one of its passengers has ever been lost.”119

24 Like his brother William, George Carvill began to engage in building construction in his local community. When Reverend Thomas L. Connolly was consecrated as the second bishop of New Brunswick in 1852, he announced his intention to build a cathedral to cater for the city’s growing Catholic population. Connolly formed a building committee to oversee the project that consisted of 12 of the city’s “most respectable Catholic citizens,” including the iron merchant George Carvill. They held their first meeting in November of that year where they agreed on an overall budget of £10,000 and raised £2,500 that night, including a substantial £100 from each of its members.120 Connolly began acquiring land for the cathedral the following year, on a large site on Waterloo Street, opposite George’s house on the outskirts of the city. Work began in the spring of 1853, aided by volunteer labour, where “fully 400 men, labourers and various trades and callings were crowded around the site of the proposed edifice, enthusiastic volunteers in the work of digging the foundation.”121 As part of a rising Catholic mercantile class, George Carvill played a prominent role in the planning and funding of the project; but his firm also supplied building materials in the form of various quantities of steel, iron, slate, and cement.122 The cathedral opened its doors in 1855, but was not fully complete until a steeple was added to the bell tower in 1871. Today this substantial stone building is still the tallest structure in Saint John, designed in the English Gothic style by the New York architect Charles Anderson.123

25 While building up a “large and prosperous iron business,” George had also begun to invest in stocks and shares: from 1853, he was as a stockholder of the Globe Assurance Company, the European and North American Railway Company, and the Saint John Fire Insurance Company.124 A testimony to his success, he built a large three-storey house for himself and his growing family in 1865 on a large plot on the corner of Waterloo and Cliff Street across from the Catholic cathedral (Figure 6). Complete with a grand arched entrance onto Waterloo Street, the house was designed in a Neoclassical style by leading New Brunswick architect Harry H. Mott.125 This three-storey over basement house was one of the largest houses in the district and was clad in brick with stone surrounds to the windows.126 Standing out against the mostly timber-clad houses in the area, it is possible that the brick and stone used to build this house arrived as ballast on one of George’s ships. By 1875 he was responsible for 5,000 tons or more of newly registered shipping, classifying him as a major ship owner in Saint John – a city that had reportedly been transformed “from a wilderness condition to that of a wealthy and populous city, and a great port known all over the world.”127 Two years later Saint John was engulfed by flames; the Carvill premises on Nelson Street were destroyed but were quickly rebuilt.128

26 The 1880s saw the passing of the older generation. In July 1884, George Carvill died in Saint John, followed by his brother William five months later in Dublin. George Carvill was remembered as one of the most prominent businessmen in the city and “one of our wealthiest citizens,” having presided over one of the leading iron enterprises in the Maritimes.129 Both men left behind substantial fortunes, emblematic of their rise in status. The value of George’s real estate amounted to $57,500 (about $2.0 million CDN today), which included his city residence at Waterloo Street, a house at Paddock Street, and his warehouse on Nelson Street. He was also the owner of 24 vacant lots: two on Nelson Street, one on Water Street, three on Main Street and 18 in Churchville in the parish of Simonds. His brother William Carvill died with assets worth over £44,687 (about £3.3 million today),130 also a substantial fortune for the time and a “considerable portion” of which consisted of shares in ships; but these assets had fallen in value by the time of his death. He owned, in addition to his business premises, houses and lands in Dublin city and county and in his home county of Down. Both men are commemorated in impressive carved stone monuments, which dominate the skyline in their respective cemeteries in Saint John and Dublin.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

Conclusion

27 The three Carvill brothers participated in international commercial networks that linked the timber, shipping, and passenger trades on both sides of the Atlantic. Born into a farming background at the turn of the 19th century, Francis Carvill was the driver of the family business. He introduced shipbuilding to the port of Newry, and his mills and factories made him the largest employer in the town. His younger brother William Carvill sailed for New Brunswick in 1836, leaving one British colony to forge opportunities in another. He took advantage of a window of opportunity during the first half of the 19th century, when protectionist tariffs made the export of colonial lumber a profitable business. He also imported a range of products, from foodstuffs to coal, fire bricks to tobacco, and a large proportion of the various types of metal goods that had been pumped out of the forges of a growing industrial Britain. When George Carvill arrived in the province in 1844, he built on the successes of his brother, and became one of the main importers of iron to the Maritimes.

28 The Carvills were part of a community of migrating Irish into North America; but rather than arriving poor and disadvantaged in the new world, they brought with them expertise and capital as they left behind their farms to further their careers in the new world.131 The trans-Atlantic trade enabled these immigrants to enter the ranks of the merchant class, where they contributed to industrialization by exporting wood and ships to Europe, importing iron, and investing in railway infrastructure and building. Their business operations, however, carried very high risks, with George Carvill’s losses in ships only one such example.132 Their expansion beyond the trans-Atlantic trade into the Indian colonies, as well as their diversification into the passenger trades, property acquisition, and house construction, no doubt enabled them to offset losses in one sector by gains in another. Versatility was essential for survival in British North America, where colonial commerce operated within the context of a “marginal trading environment.”133

29 International trade produced a two-way exchange of people and goods, which transformed the social and built environments on both sides of the Atlantic. Irish immigrants landed on North American shores, and shaped the demographics of the future Canadian state. New Brunswick trees were exchanged for British iron and steel, key products that fuelled the industrial age. These materials found their way into the architecture on both sides of the Atlantic: British iron and steel supports the stone facade of Saint John’s Catholic Cathedral, and New Brunswick timber likely forms the skeletal frame behind William Carvill’s brick facades in Dublin. Never before had such large quantities of British North American timber been used throughout the United Kingdom, particularly during the first half of the 19th century, as new churches and houses, town halls, and railway stations were built to cater for a growing population. Today, the legacy of New Brunswick’s industrial past remains embedded behind many brick and stone facades throughout Britain and Ireland. From floor joists to rafters, flooring to windows, and doors to staircases, this is all primary evidence for the province’s transoceanic, industrial, and colonial past.

SUSAN GALAVAN est titulaire d’une bourse de recherche postdoctorale Marie Sklodowska-Curie FWO (Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek – Fonds de la recherche scientifique, Flandre) au département d’architecture de la KU Leuven, en Belgique. Ses recherches

sont axées sur l’architecture domestique du 19e siècle; elle a rédigé la première étude approfondie des maisons de style victorien

de la capitale irlandaise et mène actuellement des recherches sur la typologie des maisons en rangée dans diverses villes

de Belgique

SUSAN GALAVAN is a FWO (Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek – Scientific Research Fund – Flanders) Marie Sklodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Architecture, KU Leuven,

Belgium. Her research focuses on 19th-century domestic architecture; she wrote the first in-depth study of Victorian housing

in the Irish capital and is currently researching the row house typology in a number of cities in Belgium.

Notes