Articles

The View from Jacob Street:

Reframing Urban Renewal in Postwar Halifax

En nous concentrant sur la période qui a suivi immédiatement l’étude de l’urbaniste Gordon Stephenson sur le réaménagement d’Halifax en 1957 et précédé le début de la relocalisation d’Africville en 1964, nous acquérons une compréhension différente de l’ampleur du transfert de population, de la façon dont l’effet combiné de la race et de la classe sociale a rendu des gens vulnérables au réaménagement urbain, et du pouvoir de l’administration municipale. La compréhension de ces premières initiatives de réaménagement nous amène également à porter un regard différent sur Africville. Les mesures prises par la Ville à cet endroit ont été façonnées par un changement d’attitudes envers le racisme et une tentative, certes inadéquate, de remédier à celui-ci en mettant l’accent sur l’une de ses manifestations les plus visibles : la ségrégation.

By focusing on the period immediately following planner Gordon Stephenson’s redevelopment study of Halifax in 1957 and before the start of the Africville relocation in 1964, we gain a different appreciation of the scale of displacement, the interplay of race and class in shaping people’s vulnerability to urban renewal, and the power of the municipal state. Understanding these early redevelopment efforts also provides us with a different perspective on Africville. The city’s actions there were shaped by shifting attitudes towards racism and an attempt, albeit inadequate, to rectify it by focusing on one of its most visible manifestations – segregation.

1 MENTION URBAN RENEWAL IN CANADA and the case of Africville is sure to come up. Between 1964 and 1967, the City of Halifax relocated the residents of this Black neighbourhood on the Bedford Basin and razed it to the ground.1 It is a local story that has travelled beyond the region. Africville circulates – literally – on postage stamps, in textbooks, and in young adult fiction in libraries and through digital media on platforms like iTunes. The federal government has designated it a national historic site, and it is featured in the Canadian Museum of History’s refurbished Canadian History Hall in the section on “Diversity and Human Rights.” What happened to the neighbourhood has come to be a powerful signifier of racism in Canada and of Black struggle and resilience.

2 Gordon Stephenson, whose 1957 redevelopment plan was fundamental to transforming the city, supported the neighbourhood’s destruction and the relocation of its residents. But he did not consider it a priority. In fact, Africville was not part of his study area and he devoted just a few paragraphs to it. Moreover, the approximately 400 people who called Africville home represented only a small proportion of the estimated 6,000 people displaced by urban renewal; indeed, municipal authorities appear to have uprooted more Black Haligonians from other parts of the city.2

3 This is not to deny Africville’s importance or the trauma its residents experienced: as scholars working from a variety of disciplines have shown, what happened to the neighbourhood reveals the shortcomings of planned social change, the spatial dynamics of racism, the workings of state power, the politicization of the African Nova Scotian community, the face of environmental racism, and the “anti-blackness” of urban planning.3 Nor is it to deny Africville’s ongoing significance for Black identity and the politics of race in Halifax.

4 But if we want to understand the postwar reshaping of Halifax more generally and the social costs of urban renewal, we need to take a broader and a deeper view – one that examines the city as a whole and how municipal authorities acquired properties and dealt with their owners and occupants. Focusing largely on the period immediately after the Stephenson report and before the Africville relocation started, I begin with a brief overview of housing in the postwar period and the debates over the proposed slum clearance of part of Halifax’s North End, an area that was home to a diverse, poor, and working class population that included the majority of the city’s Black population. I then look at how federal redevelopment dollars allowed Halifax to begin to renew itself, starting with its inner core – an area near City Hall and the City Market around Jacob Street.

5 Important as Ottawa was to funding urban renewal, the “federal bulldozer” was not the only force reshaping the city. Its effects were reinforced and extended by Halifax authorities through their enforcement of Ordinance No. 50, a bylaw pertaining to minimum standards for occupancy as well as sections of the city charter relating to safety. The North End was again the target, this time of the city’s building inspectors. As was the case with so many urban renewal schemes, the operation of the federal bulldozer and municipal wrecking ball increased housing insecurity. They had the effect of shovelling out the poor – both Black and White – to equally bad and often more expensive accommodations or pushing them out of the city entirely.

6 Looking at urban renewal in the immediate aftermath of the Stephenson report gives us a different appreciation of the scale of displacement and its victims, people who were among Halifax’s poorest citizens. There, as in other cities in Atlantic Canada, the areas targetted for redevelopment in the postwar period were home to largely White communities of working poor and unemployed.4 Halifax’s demography, and specifically the presence of a small African Nova Scotian population concentrated in the areas targetted for renewal, reveals how both race and class shaped residents’ vulnerability to displacement. While exact numbers are lacking, Black Haligonians appear to have been disproportionately affected by redevelopment although, in terms of numbers, more White Haligonians were uprooted.

7 The latter aspect of urban renewal is not surprising given that the Black population represented less than 2 per cent of the city’s residents in the late 1950s.5 Yet it raises questions about recent characterizations of planning that underscore the primacy of race in city-making. Geographer Ted Rutland makes a compelling case for how “anti-blackness” animated urban planning during the 20th century, with consequences for Black and non-Black residents – in Halifax, the focal point of his study, and more generally. While there is no doubt “planning is an instrument of power and race,” his argument about the fundamental anti-Blackness of planning does not entirely explain what happened to the thousands of poor White residents of Jacob Street and the North End who were displaced. As he acknowledges, they constituted the numerical majority of those who were uprooted. But his assertion that “a deep-rooted structure of anti-blackness has shaped planning’s dealings with all city residents, Black and non-Black” is not supported in this instance: as far as I can see, poor White Haligonians were neither racialized by the planners who argued for the redevelopment of their neighbourhoods nor was the idealized life imagined for them – tenancy in public housing – at odds with their status before displacement as it was for the uprooted residents of Africville. Tenancy was not imposed on them as it was Black Haligonians: they were renters and would continue to be.6

8 That said, Rutland is certainly right that the displacement and housing insecurity that resulted from urban renewal had different consequences for Black and White Haligonians. But there was also a diversity of experiences with redevelopment among Black residents, between those who lived in the North End and those who lived in Africville. Rather than explore it, though, his book takes what happened to Africville as normative. It was not. As we will see, its residents were treated differently than those who lived in the North End – something that points to the many manifestations of anti-Black racism.

9 As well as exposing the scale of displacement and its victims, an examination of urban redevelopment in the aftermath of the Stephenson report reveals the crucial role the municipal state played in city making. While most studies of urban renewal in Canada focus on the federal government, city officials were also instrumental in building a better Halifax. Yet the literature on Atlantic Canada emphasizes the weakness of the municipal state: a fear of taxation meant there were fewer incorporated municipalities in the region than elsewhere, and those that did exist were poorer than their counterparts elsewhere in Canada. As E.R. Forbes points out in his analysis of the 1930s, not only did they have a smaller tax base but their revenues were also often insufficient to allow them to participate in a meaningful way in the matching grant programs offered by the federal government.7 In Nova Scotia, the existence of the poor law – which burdened towns and cities with the cost of social services until the 1950s – was a further disincentive to elaborating a state apparatus at the municipal level. Instead, churches and charitable organizations remained important providers of welfare into the 1960s.8 But, as the redevelopment efforts undertaken by the City of Halifax suggest, that did not mean municipalities were without power. Nor were they incapable of exercising that which they did have in the name of improving people’s lives, particularly when it also meant increasing the tax revenues flowing to municipal coffers.

10 Finally, understanding the redevelopment efforts undertaken by Halifax in the late 1950s and early 1960s provides another measure with which to gauge what happened in Africville. We see how racism influenced the actions of municipal authorities – but not just in the way that has been highlighted in the literature. The view from Jacob Street and the North End emphasizes, as Jennifer J. Nelson does, that Africville “is a story of white domination, a story of the making of a slum, and of the operation of technologies of oppression and regulation over time.”9 But Africville is also a story about shifting attitudes towards racism. The city’s deviations from the practices it followed in the rest of Halifax when it came to redeveloping Africville were motivated by an awareness of the neighbourhood’s history and its own role in shaping it. In that sense those deviations were an attempt to rectify a kind of racism that was increasingly unacceptable, namely segregation. As a result its residents were treated more liberally by municipal authorities – but still inadequately – than were those displaced from other parts of the city, both Black and White.

11 Like many older cities in Canada and in the Atlantic region, Halifax struggled with housing quality and availability in the first decades of the 20th century – in no small part because of the devastation that resulted when a munitions ship collided with another vessel in the city’s harbour in December 1917.10 The explosion killed and injured thousands and left thousands more without adequate shelter – if any at all. To help these people, the Halifax Relief Commission embarked on what was Canada’s first public housing project – the “Hydrostone district” – a 325-unit, English-style garden suburb built amidst what used to be the community of Richmond Heights in the North End.11

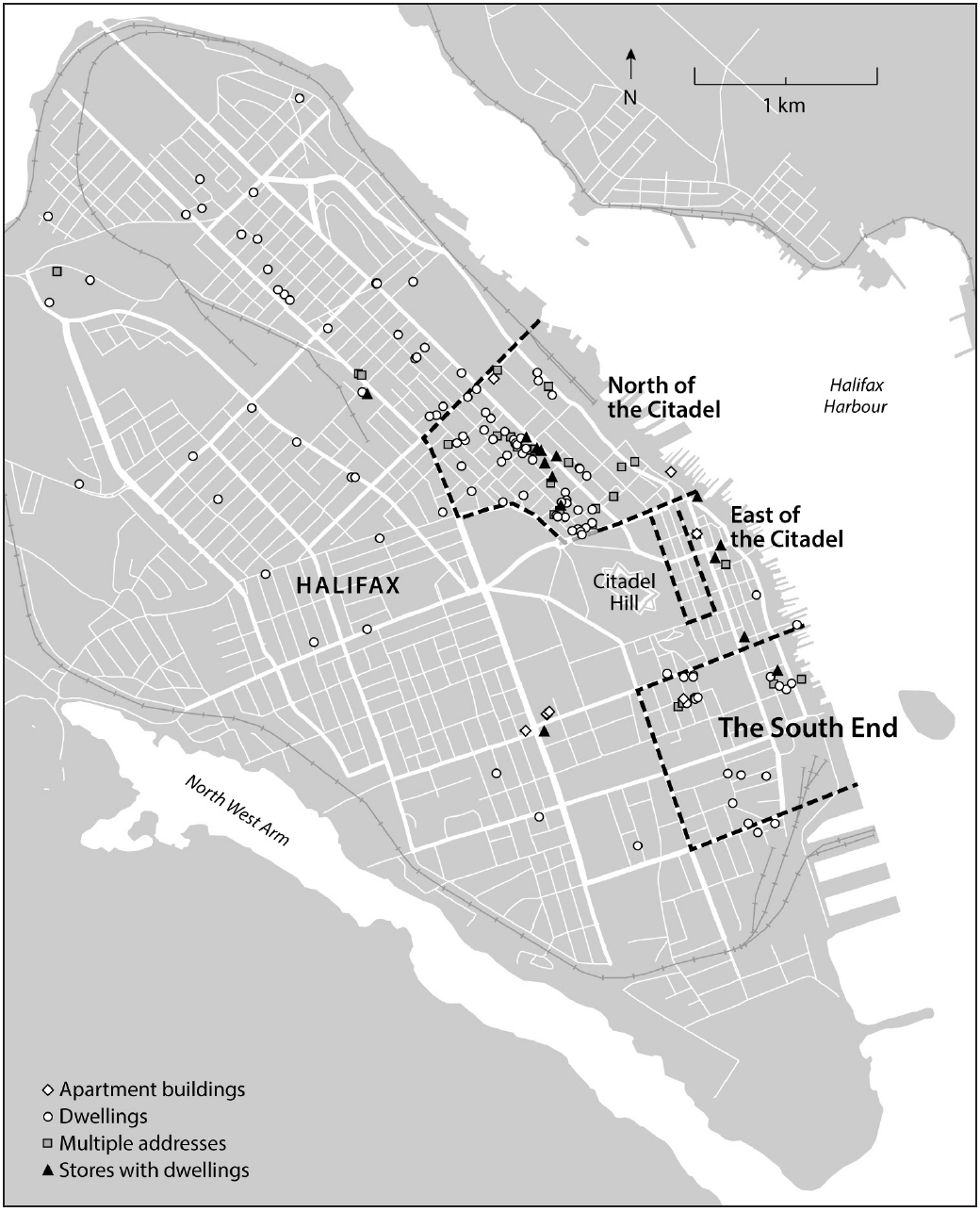

12 The Second World War brought Halifax’s housing problems to the forefront again. This time the cause was not a catastrophic explosion: it was a flood of people. In addition to military personnel, men and women seeking work in wartime industries moved to Halifax in great numbers and this put much pressure on its limited and aging housing stock. With the influx of just over 19,000 people between 1939 and 1945, the city of about 65,000 saw its population increase by nearly 30 per cent. People crowded into whatever space was available: a family of 8 lived in one room, 25 people made do in a 4-room house, and 36 in a 12-room building. Those spaces were often in poor condition: a 1944 housing survey revealed that 43 per cent of the city’s 12,000 dwelling units were “not structurally good,” and many lacked basic amenities like sanitary facilities.12

13 The housing shortage was so severe that some considered it detrimental to Canada’s war effort. In response, the federal government engaged in a publicity campaign to dissuade people from moving to the port city. There were also discussions about establishing a 50-mile cordon around Halifax and relocating 4,000 people who were not employed in wartime industries out of the city to alleviate the problem. The one thing the federal government did not do was deepen its involvement in the home construction business. Even after the veterans returned and it was clear that those who had moved to the city for work were there to stay, Ottawa took a cautious approach. As John Bacher points out, the success of the public housing it helped build in Halifax simply highlighted the scale of the problem: when it was completed in 1953, the Bayers Road project received 1,000 applications for just 161 units.13

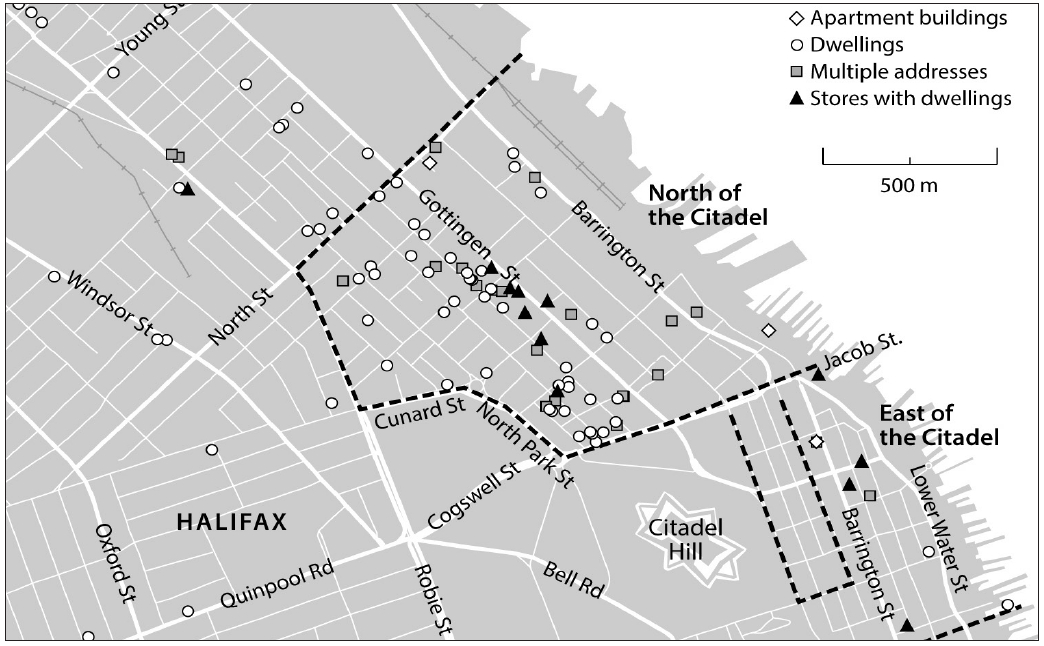

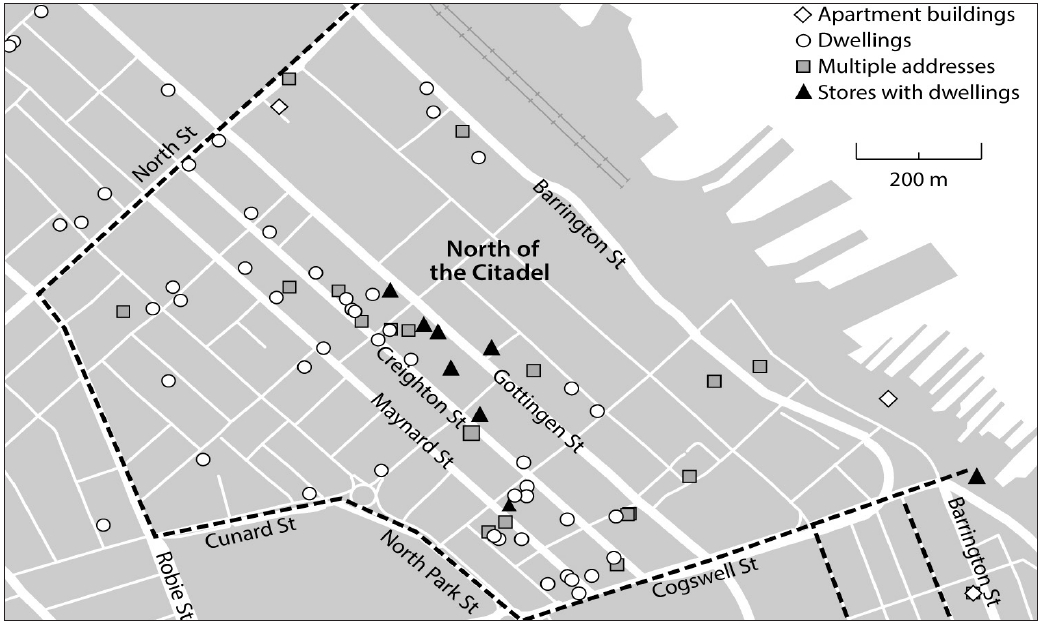

14 Municipal authorities were well aware of the city’s housing problems, and at war’s end they converted Department of National Defence barracks and staff housing as well as some city-owned properties into emergency shelters. “By no means first class,” the 419 units were “immediately occupied and a long waiting list soon formed.”14 Although the federal assistance to these shelters ended in 1949, the city continued to operate them. When the last was closed in 1961, its tenants had to be evicted; this suggests that the housing problem continued.15

15 Beyond reacting to the housing shortage, the city also recognized the need for “a program of reconstruction and rehabilitation” to “effect . . . an orderly transition from wartime to peacetime conditions.” To that end, and among other things, the terms of reference for its 1945 Master Plan directed officials to study Halifax’s housing problem and recommend specific areas for slum clearance and the construction of low cost housing.16

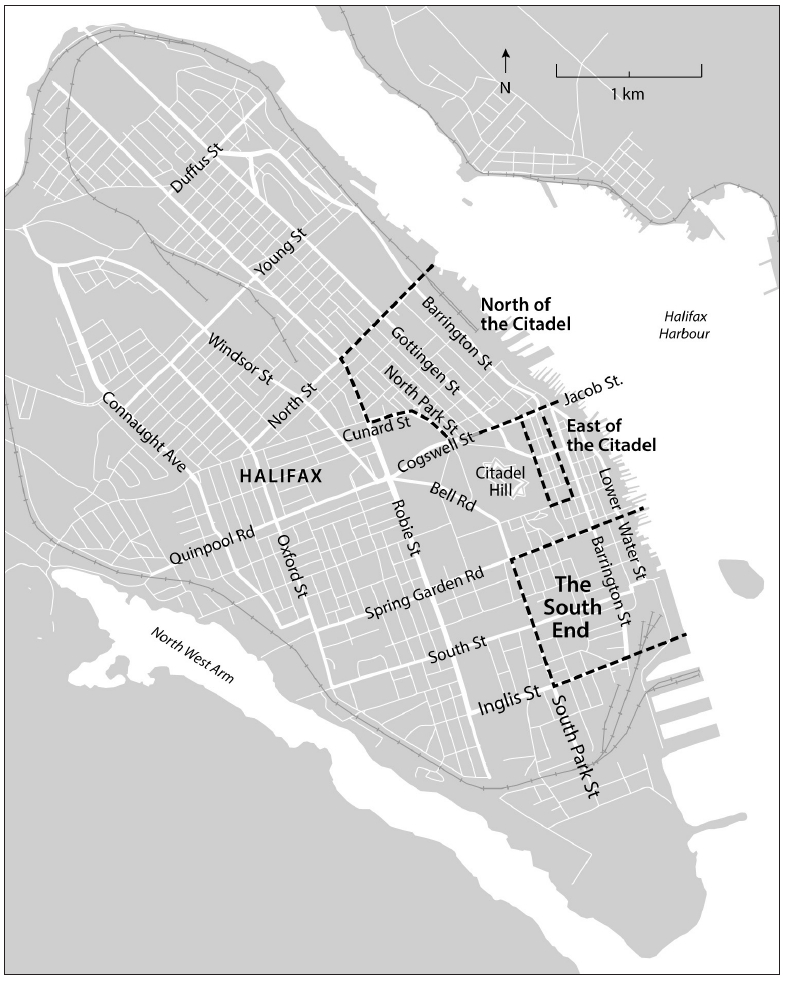

16 Locating the slums of Halifax proved to be relatively straightforward. The Master Plan targetted 200 acres in the south end and 160 acres north and east of the Citadel as candidates for redevelopment (Figure 1).17 The latter area, which comprised the historic North End (an area from, roughly, Cogswell Street to North Street, and between Robie and Gottingen Streets) and a number of blocks downtown, around city hall and the city market (what would become the Jacob Street and, later, the Central Redevelopment Area), were deemed in particular need of attention: the buildings were overcrowded, and many lacked basic sanitary facilities, were structurally unsound, or both. Worse still from the city’s perspective, it spent more on providing the area with fire, police, medical, and other social services than it did elsewhere, but the taxes it collected were between half and two-thirds what it garnered from an average residential neighbourhood. As the Civic Planning Commission put it, “The entire community thus subsidizes the maintenance of slums.” Clearance and redevelopment would increase property values and hence municipal revenues. Perhaps surprisingly, there was little discussion of Africville in the Master Plan: all the Civic Planning Commission had to say was that “the residents of this district must, as soon as reasonably possible, be provided with decent minimum standard housing elsewhere.”18

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

17 Although the area north and east of the Citadel was a mix of residential and commercial properties, the Civic Planning Commission argued it “cannot reasonably be considered suitable for individual home ownership.” Instead, it imagined the area being redeveloped to provide “thousands of low rental apartments” – an idea that was subsequently taken up in Halifax’s 10 Year Development Plan, or “Official Town Plan” (1950). In setting out the projects the city would embark upon in the immediate future, planning engineer J. Philip Dumaresq saw the area as rehousing those displaced in the process of clearing the North End as well as those who lost their homes in the blocks east of the Citadel around Market Street and City Hall – an area which he considered “one of the worst slum districts in the City of Halifax” and a priority for redevelopment (Figure 1).19

18 If identifying the slums of Halifax was easy, the city’s Slum Clearance and Public Housing Committee soon learned that doing something about them was not. Created in 1951, it held public hearings on the Town Planning Board’s proposals to clear parts of the North End in 1951, 1954, and 1956. While the exact boundaries of the clearance area changed, it centred on Maynard Street and Creighton Street. This neighbourhood – and not Africville – was where the majority of Black Haligonians lived, some 1,200 people, or nearly three-quarters of the city’s African Nova Scotian population. There may have been more African Nova Scotians in this part of Halifax than elsewhere, but Whites still made up the majority of the population of the North End. Indeed, in contrast to Africville, the Black residents on Maynard and Creighton had White neighbours.20 They were spatially integrated into the city, whereas the residents of Africville were not.

19 Most of those appearing before the committee were in favour of slum clearance for the same reasons that were put forward in other cities embarking on the same program: it would improve the physical and moral health and welfare of residents. The Halifax Trades and Labour Council considered “the stinking, desolated, over-crowded, expensive slum sections” to be “the biggest blight in cities of the world today.” In its view, “to consent to the exploitation of oneself is immoral; to consent to the exploitation of others is just as immoral.” Supporting slum clearance helped fulfill its aim to “secure a decent, separate home for every worker.” On behalf of the Welfare Council of Halifax, social worker Gwendolyn Shand argued “decent housing is essential for wholesome family life. Poor housing has always been one of the causes of disease, delinquency, broken families and general demoralization.”21 Similarly, the Halifax branch of the Community Planning Association of Canada made the connection between overcrowding and crime, noting “almost without exception, juvenile delinquents come from sections where there is bad housing . . . . When families have moved to better residential areas, with opportunity for play, nothing further has been heard about the children who were previously delinquents.”22

20 But many who lived in the area designated for clearance had their own ideas of what was in their best interest, and they opposed redevelopment. The Black residents of the Maynard and Creighton streets area found a spokesman in Reverend W.P. Oliver, the long-time minister of the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church that served the neighbourhood. A member of the Slum Clearance and Public Housing Committee, he was an important advocate for the Black community in Nova Scotia. In 1945 he founded the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Colored People, an integrated group committed to, among other things, securing better housing for African Nova Scotians and promoting “better human relations based upon a mutual understanding among the various groups, with special emphasis on colored-white relations.”23 While insisting he was not against progress, Oliver had misgivings about the plan to clear the North End and encouraged people to do as he did and let the city know their position.

21 Identifying Haligonians as Black or White is difficult in the absence of census information. I have done so on the basis of their addresses and the substance of what they wrote. In a series of letters written as part of an organized campaign, Black residents pushed back against the proposed clearance of their neighbourhood. Despite their lower socio-economic status, a greater proportion of them owned their homes compared to their White counterparts. Ownership was “a form of insurance against involuntary removal” and the racism that made it difficult to find shelter in the city.”24 W.P. Oliver contended that 35 per cent of African Nova Scotians in the North End were homeowners, significantly more than the 23 per cent average for the census tract as a whole. Although he did not supply statistics, Gordon Stephenson observed that “for longstanding social reasons, the highest owner-occupancy rate is in that part [of Halifax] in which there is a high concentration of Negro families.”25

22 For Black Haligonians, the violence of slum clearance did not just lie in being made to move; it also stemmed from the forcible taking of their property and hence their security. As the language they used suggests, they recognized slum clearance as an aggressive attempt to reorganize property ownership in the city. Historians’ arguments about the relative weakness of the municipal state in Atlantic Canada aside, these African Nova Scotians had no doubt about its power.

23 “I am against the City taking over our homes. I have always tried to keep my home in the best shape I could. I am satisfied with it and so is my family,” Mrs. Carey of 177 Creighton Street wrote to the mayor and members of the Slum Clearance and Public Housing Committee in 1954. “Why should the City take it or buy it from us? My parents lived in this part of the city and we were brought up here. We live in the best manner we can for our incomes. If you take this district where will we go?” In registering his opposition, Henry Kane underscored his military service. “Now after many years of sweat, tears and broken hearts, I have been able to purchase my home, in which I now live and I do not wish anyone to come along and destroy it,” he wrote. “I certainly do not wished to be chased out of this section or have my property taken away and my family scattered.” And the Browns let the city know that as “property owners” they opposed “being pushed out.”26

24 Louise James echoed the sentiments of her neighbours and gave explicit voice to the fears many African Nova Scotians had about redevelopment: “I have not the money to live in a more expensive house and even if the City gave me good money for my home where could I go?”27 Low-cost public housing was the obvious answer, but many Black Haligonians did not consider it a viable option; despite assurances, many believed that they would not be welcome in such facilities.28 Finding private accommodation was also difficult. As the Jewish Labour Committee discovered during its investigations in Halifax in the early 1960s, African Nova Scotians faced serious discrimination in securing housing and employment.29

25 If owning a house was a source of security, W.P. Oliver also considered it proof of an individual’s moral worth. “I am opposed to taking people out of their own homes and compelling them to live in apartments,” he told his colleagues on the Slum Clearance and Public Housing Committee. “Men and women who have had the spirit of citizenship and spunk to save and build a home should be allowed to live as first class citizens.” In his view, to force people to give up their homes was to erode their status as citizens. At the very least, it was discriminatory. He wondered if the city was holding Black homeowners to higher building standards, or, short of that, whether Black homeowners were being made to pay for the fact that White landlords had turned the area into a slum by not keeping up the properties they rented out in the neighbourhood.30

26 Many of the White residents in the North End were also opposed to slum clearance. While their arguments echoed some of the same sentiments about security and citizenship, they also emphasized what in their view was the antidemocratic nature of redevelopment. “Would those in authority be glad to give up their homes and go in apartments with dozens of other families and pay rent to someone else instead of ownership and privacy?” asked “Disgusted” in a letter to the Mail-Star. “We are going to suffer because of what some others think is a good idea,” Creighton Street grocer Harold Hoare observed. “These homes might not provide much toward another home [i.e., in terms of the compensation owners received] but at least they are a place to live. Under this scheme where is the security for these people? Where is the justice?” According to C.H. Griffith of 17 Bauer Street, “A small group in authority has decided to confiscate an area of the city, force the people out and demolish their homes, regardless of their unanimous disapproval. Is that democracy?” In his view, “Every man has an inalienable right to protect his home, and defend it against all enemies.”31

27 Given this opposition, and despite more than a decade of discussion after issuing its Master Plan, the city chose not to proceed with slum clearance. Instead, it would undertake a redevelopment study. On the basis of advice from the federal minister of Public Works, the mayor and council hired University of Toronto-based architect and planner Gordon Stephenson for the job in July 1956. Like many of the planners hired in Canada in the postwar period, he was British.32 Before coming to Canada, he studied with noted Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, and, in the United States, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He worked first in Britain on postwar reconstruction and then in Australia, eventually returning there permanently in 1960.33

28 Although the Slum Clearance and Public Housing Committee had done a preliminary survey in 1955 of a 56-block area in the North End adjacent to the Citadel, in the ensuing debate about clearing the Maynard and Creighton streets area the city’s critics and even the pro-development Mail-Star encouraged it to “get all the facts first” before proceeding.34 Doing so became financially palatable because of changes to the National Housing Act, which allowed municipalities to share the costs of formulating a redevelopment plan with Ottawa. Other amendments in 1956 further incentivized slum clearance through a cost-sharing program that helped cities to acquire and clear properties in such residential areas, and allowed them to put that land to its “highest and best use” rather than requiring it to be redeveloped for low-cost rental housing.35

29 Certainly these financial incentives played a role in Gordon Stephenson’s hiring. As one former city alderman told planning scholar Jill Grant, at the time “at least 75 per cent of the Council were not pro-planning” as they saw it as interfering with free enterprise. Yet in the end they were convinced to hire a planner, in no small part because access to federal monies for redevelopment required cities to create comprehensive plans and because “other cities had them [planners] and this was supposed to be the thing to do.”36

30 The alderman’s comment speaks to the general enchantment with planning expertise in the postwar period. In North America the 20 to 25 years after the Second World War have been dubbed planning’s “Golden Age,” a period when such expertise “was perhaps most unchallenged.”37 North American cities contracted with planners and established their own planning departments, deploying them against urban decline. As Wendell E. Pritchett argues, planners were instrumental in developing that discourse of degeneration – one that positioned their profession as possessed of the expertise to address and ultimately reverse it.38

31 Cities had grown organically over centuries and as a result, it was not uncommon for people to live, work, play, and pray in the same neighbourhood. While Jane Jacobs would come to see this variety of uses as the lifeblood of cities, beginning in the mid-19th century in Europe, and especially after 1945 in North America, urban experts considered such jumbled use inefficient and unhealthy; indeed, the encroachment of commercial and industrial enterprises on formerly residential districts could only result in “blight” and, ultimately, the development of slums: these were areas “with run-down buildings, dirty streets, and a high crime rate . . . almost exclusively occupied by poor people.”39

32 Never precisely defined in the urban context, “blight” connoted disease; indeed, that was its original meaning. Members of the Chicago school of sociology were the first to apply the term in a city setting in their examinations of poverty in the 1920s and 1930s. In doing so, they naturalized urban decline and justified intervention by experts. In their view, cities were organisms with metabolisms and ecologies. Just as the expertise of the plant pathologist was required to diagnose and treat crops afflicted by blight, so too was scientific intervention by planners necessary to address urban decline and prevent its spread. Comprehensive planning – seeing the city as a whole – would ensure rational and profitable urban growth.40 In setting out a blueprint for a modern, healthy, and efficient city, “master plans” like the one produced for Halifax called for the separation and regulation of land use through zoning and for the “renewal” of blighted areas and slums through the acquisition and clearance of their properties.

33 Released in June 1957, Gordon Stephenson’s redevelopment study of Halifax was in many ways a classic statement of the ideals of postwar planning. It called for municipal authorities to revise the city’s zoning, to apply its bylaw relating to minimum standards for housing (and indeed to make those standards more stringent), and to strengthen building and health inspection. Since any modern city had to accommodate cars, it discussed parking and road works, including highways, to improve the flow of traffic.

34 Most importantly for my purpose, Stephenson also outlined seven redevelopment schemes and underscored the need to provide housing for those displaced. Like the Master Plan of 1945 and the 10 Year Development Plan, he focussed primarily on the area north and east of the Citadel – that is, on the North End and the area around City Hall and the City Market. And like these two previous plans he treated Africville’s redevelopment as a foregone conclusion, something that was both necessary and long overdue:

Moving them out, in other words, was an act of justice for a maligned minority, something beyond discussion. He did not, however, prioritize the area’s redevelopment or even include it in his study area.

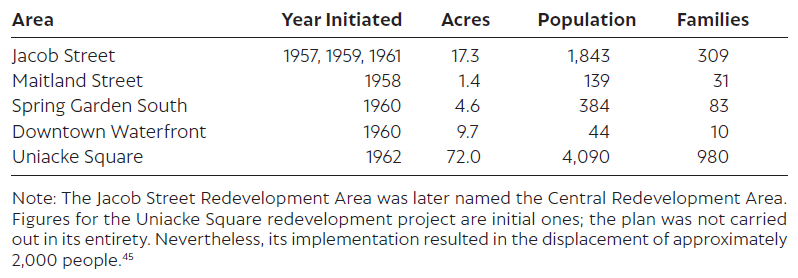

35 Stephenson insisted he had not produced a detailed, costed plan but a set of ideas that could be adopted as part of a comprehensive proposal to be carried out over 20 years.42 City Council, however, was not so patient. By the time Halifax officials approached the first residents of Africville about leaving in 1964, they were well practiced in acquiring properties and demolishing them with the “federal bulldozer” – that is, with funds provided through the federal government under the National Housing Act.43 Consistent with Stephenson’s recommendations, they had initiated five redevelopment projects with provincial and federal support (Table 1 and Figure 2). Together, these promised to uproot literally thousands of people.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

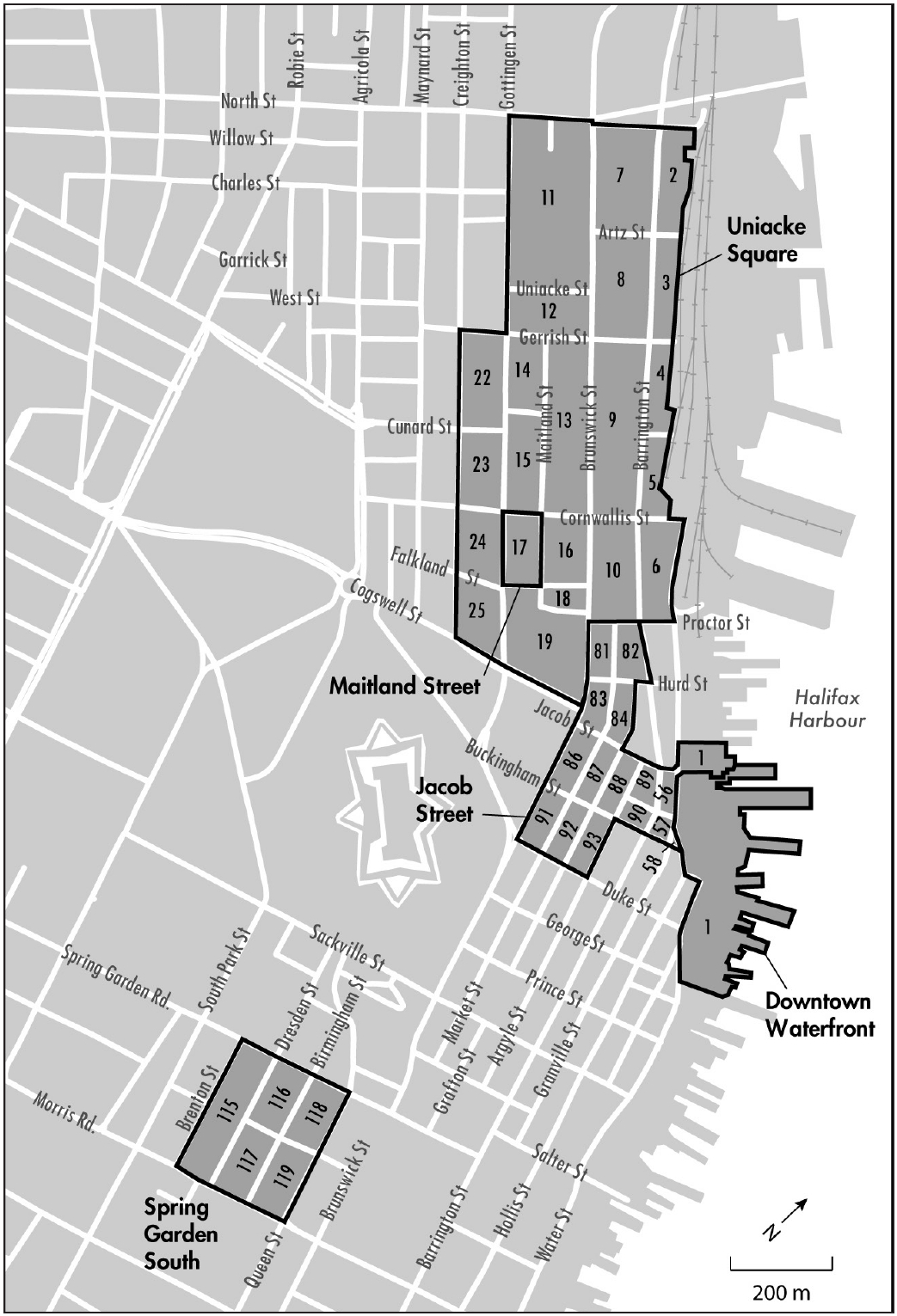

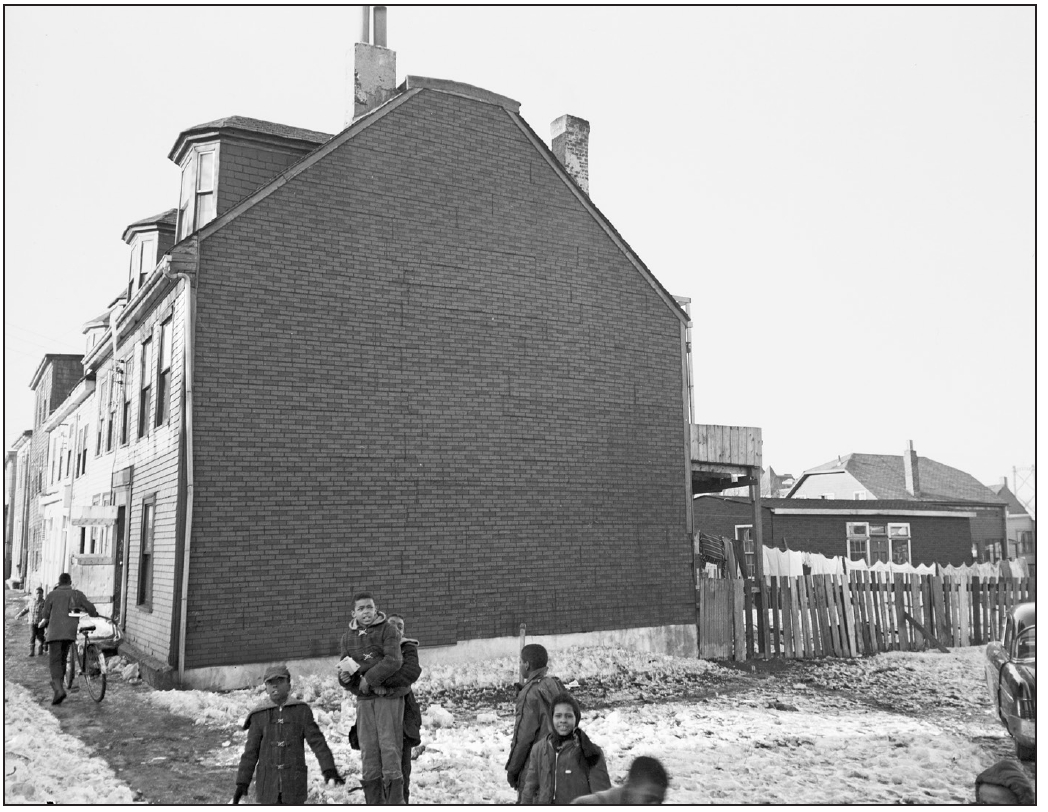

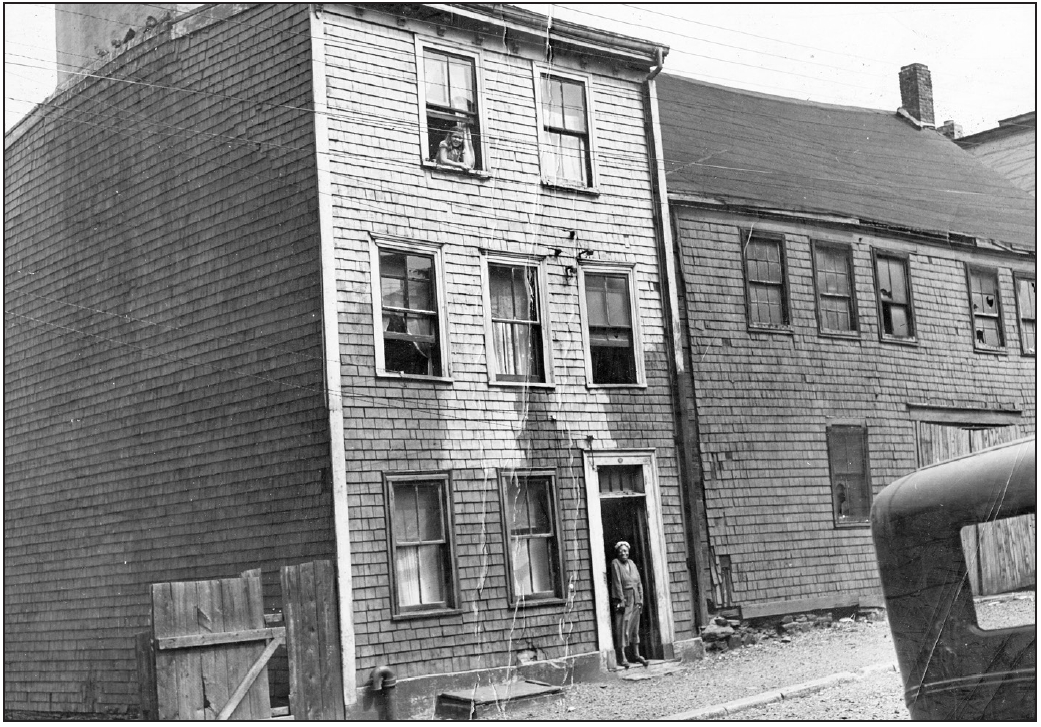

36 As “the worst part of the central area” of Halifax, the blocks around City Hall, the City Market, and Jacob Street were the first priority for redevelopment (Figure 3). With a few exceptions, Gordon Stephenson, like J. Philip Dumaresq before him, considered them “generally in deplorable condition,” a slum: “Here are some of the worst tenements, and dirty cinder sidewalks merge with patches of cleared land littered with rubbish. It is suggested that the clearance of this area should have high priority.” Like many planners, Stephenson believed the physical state of the neighbourhood was indicative of its moral state. The maps in his Redevelopment Study suggested that crime and juvenile delinquency characterized the area, and that it was home to a large number of poor and unhealthy people. As part of his research, he mapped the location of “hard core” relief cases, children testing positive for tuberculosis, incidents under the criminal code, fire risk, and “serious deficiencies in sanitary equipment.”46 To borrow Sean Purdy’s phrase from his work on slum clearance in Toronto’s Regent Park, Jacob Street was one of Halifax’s “pariah spaces” – made so in no small part by the work of planners like Stephenson and those who came before him.47

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

37 Consistent with the thinking on urban reform, Stephenson believed overcrowding was ultimately to blame for these conditions. Indeed, the blocks around Jacob Street were some of the worst in his study area – and the city generally – where as many as two-thirds to three-quarters of the dwellings were overcrowded.48 The solution was to knock them down and get people into better housing, though not necessarily in the same area.

38 There were 185 properties in this redevelopment area.49 Most of the residential ones were occupied by their owners, many of whom had tenants. Indeed, Halifax was a city of renters rather than owners, with 53 per cent of dwellings occupied by tenants in 1951. But in the census tract in which the Jacob Street Redevelopment Area was located, 86 per cent of dwellings were occupied by tenants. That said, the area was not entirely residential: some buildings housed families and small businesses, and the neighbourhood also featured other businesses like the Sanitary Barbershop and Keller’s Second Hand. It was also home to some larger enterprises like Clayton’s Clothing and machinists W&A Moir as well as institutions like the Navy and the Salvation Army, whose hostel served 2,200 men every month.50

39 The cost of acquiring and clearing land in the redevelopment area was shared equally between the municipal and federal governments. While the city preferred to acquire land through negotiation, it did resort to expropriation when discussions with owners reached an impasse. In acquiring properties, city Compensation Officer C.D. Smith used a formula: initially, he offered owners assessed value plus 5 per cent.51 Many settled for that amount. His recommendations came before the Redevelopment Committee of City Council for discussion and approval. Occasionally property owners, especially the proprietors of small businesses or their legal representatives, appeared before the committee to plead their cases. Few opposed redevelopment; instead, what they took issue with was the compensation offered and the difficulties of finding alternative housing and re-establishing their businesses.52

40 Once owners sold, they had 30 days to vacate. In cases where the building was a tenement, the 30 days was meant to allow tenants enough time to find other accommodations. That was not always possible, which meant the city left the building standing and became a landlord, collecting rent until such time as it could facilitate moves for these tenants and demolish the property. Although tenants did not appear before the Redevelopment Committee to take issue with what was happening to them, they did make their feelings known other ways. A significant number refused to pay their new landlord rent even though that effectively disqualified them from being accepted into public housing.53 A few others simply refused to leave, forcing the city to call the police to evict them.54

41 Despite these small rebellions, the process of acquiring properties in the Jacob Street area moved quickly at first: the city secured nearly half them in the first year of the redevelopment program, 1958-1959.55 Getting the rest proved to be more difficult, requiring protracted negotiations and, in some cases, formal expropriation proceedings.56 By 1962, it had acquired all the land and issued a call for redevelopment proposals. After a false start, construction on Scotia Square finally began in the late 1960s and was followed by the Cogswell Interchange. In between, as Christopher Parsons notes, the neighbourhood looked remarkably like the bombed out British towns Gordon Stephenson had helped rebuild as a young planner.57

42 Almost from the start of redevelopment in the Jacob Street area, the city’s aldermen and its welfare department expressed concerns about those forced out by redevelopment. While the city was obliged to rehouse displaced families (but not individuals), its redevelopment program was also diminishing the accommodations available and driving up rents. This had secondary effects, making life harder for poor and working-class residents in a city that had a history of housing shortages.

43 In fact, the problem of high rents and housing insecurity was compounded by two initiatives the city undertook on its own and outside jointly funded redevelopment areas like Jacob Street. Both have largely escaped attention in discussions of urban renewal in Halifax. But as will become apparent, these municipal initiatives to address substandard housing and blight were at least as important as the federal bulldozer – the NHA – in reshaping the city. They speak to the power of the municipal state in unsettling the lives of some of its most vulnerable residents.

44 That is not to suggest that housing was always needlessly demolished: as the Committee on Works minutes reveal, many poor and working class Haligonians lived in abysmal conditions that threatened their health and safety. For example, in 1958 the city ordered a three-storey tenement near Cunard and Agricola Streets taken down because it was dilapidated: home to 44 people, its floors sagged and its walls bulged from structural weaknesses. “Mrs. Parsons, a tenant in the above building, said that her nine-year-old daughter was in the hospital for the third time this year and another daughter had a serious bronchial condition. She said her husband was a disabled war veteran and couldn’t afford to pay high rent.”58

45 The Hollis Street property owned by Lillian King was ordered demolished because “there was no hot water in the building, no bath, no vent in the toilet, evidence of rats and that the roof was leaking.” A tenant who had lived in King’s building for five years informed the Committee on Works that the house “was alive with rats; that in some places the floor would collapse under a person’s weight.”59

46 The basement floor of the house Albert J. Walker owned and rented out on Brunswick Street rested directly on dirt, and the rooms were not very high; less than seven feet in the basement and only five feet, five inches in one of toilets. Nevertheless, he took the city to court in 1961 to challenge its teardown order.60

47 The municipal wrecking ball gained part of its momentum from Ordinance No. 50. Passed in 1956, this bylaw, which took effect 1 January 1958, set minimum standards for the occupancy of dwellings built before 1945.61 Halifax was one of the few cities in Canada to have a minimum standards ordinance, or so it claimed.62 It required property owners to maintain dwellings “in a state of good repair and structurally sound and fit for human habitation.” To that end, it set out requirements for space, ventilation, light, and sanitation, among other things.63

48 Building inspectors for the Works Department informed owners of the repairs necessary to bring their dwellings up to standard and set a deadline for them to do so, one that was backed by severe penalties. Not only were those who failed to comply subject to a fine of up to $100 or two months imprisonment, but “every day during which any such contravention or failure to comply continues shall be deemed a fresh offence.”64 In some cases, inspectors judged buildings to be beyond repair. Their recommendations for demolition were passed on to the Committee on Works, a body of the City Council, for a final decision.

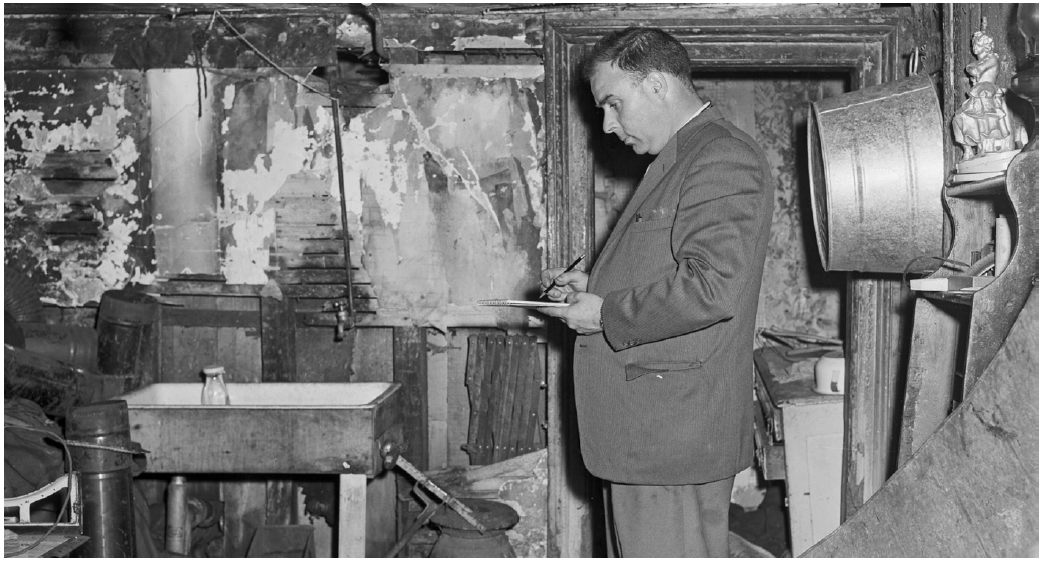

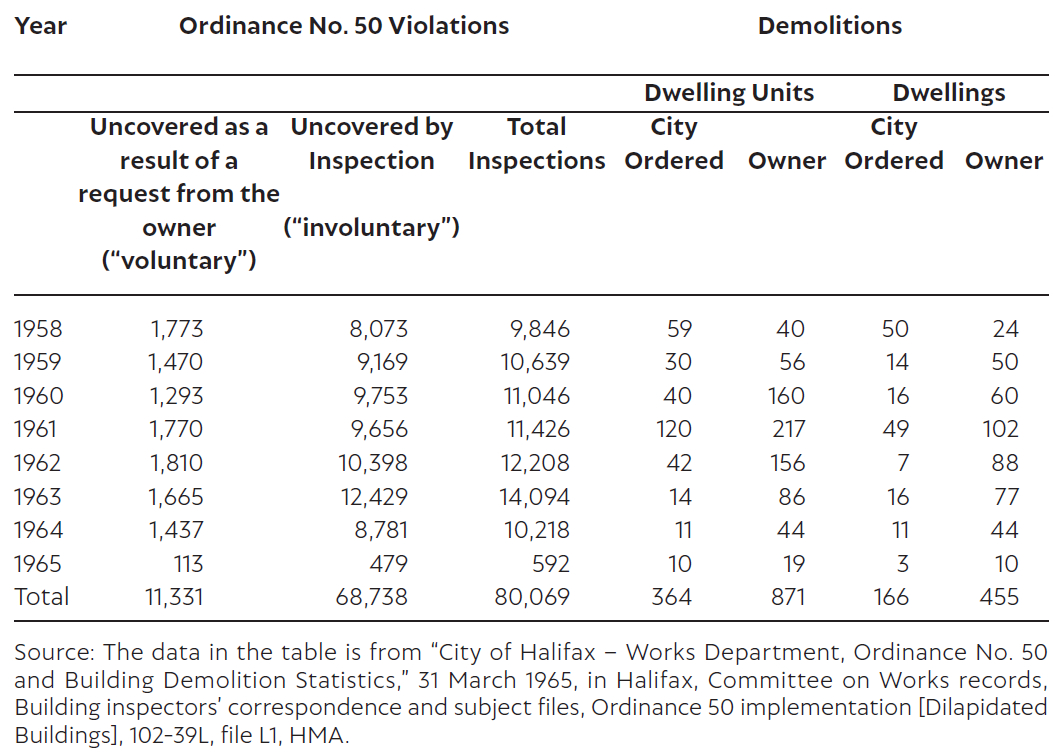

49 Although Stephenson thought the standards set out in the ordinance were too low, he nevertheless pushed for their “forthright” and “vigorous” application.65 If the impressive number of inspections undertaken by the small staff at the Works Department is any indication, he got it.66 Inspections rose steadily until 1963 (Table 2). Violations of Ordinance No. 50 came to the city’s attention in one of two ways: the first, which the Works Department deemed “voluntary,” included those violations that were uncovered as a result of a request from a property owner for an inspection or for a building permit to do minor repairs, something that necessitated an inspection. Violations also came to the attention of the Works Department in the course of building inspectors’ regular work (Figure 4), as part of the process of issuing tax certificates, from private individuals wishing to buy a property, from real estate agents wishing to buy or sell a property, or from tenants in substandard buildings. Because they did not arise from a request from the property owner, they were deemed to have been uncovered involuntarily.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

50 In addition to revealing the vigorous enforcement of Ordinance No. 50, the statistics in Table 2 also suggest that doing so had an additional and perhaps unanticipated effect: confronted with the prospect of undertaking expensive repairs, some owners chose to demolish their buildings. Regardless of whether owners did the necessary repairs or took down their offending dwellings, the city achieved its goal of improving conditions – but it was at the cost of diminishing the supply of housing.67 Between 1958 and 1965, 1,235 “dwelling units” were torn down.

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 251 In addition to enforcing Ordinance No. 50, municipal authorities also deployed three sections of the city charter to rid Halifax of blight – namely, sections 754 (Dangerous Buildings), 756A (Buildings Destroyed or Partially Destroyed by Fire), and 757 (Dilapidated Buildings) – the latter of which was the most frequently used and the section under which most demolitions were carried out. 69 Concerns about dilapidated buildings came to the attention of the Works Department the same way violations of Ordinance No. 50 did – that is, through voluntary and involuntary means.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

52 These sections of the charter empowered building inspectors to order dilapidated buildings removed by a specific date. In cases where owners did not comply, the Committee on Works held a public hearing. It heard from the owners and/or their representatives and considered a comprehensive report on the property in question produced by the Works Department in consultation with the city’s fire, health, electrical, and plumbing departments. In almost every case, the committee supported the recommendation of the Works Department and ordered demolition at the owner’s expense.

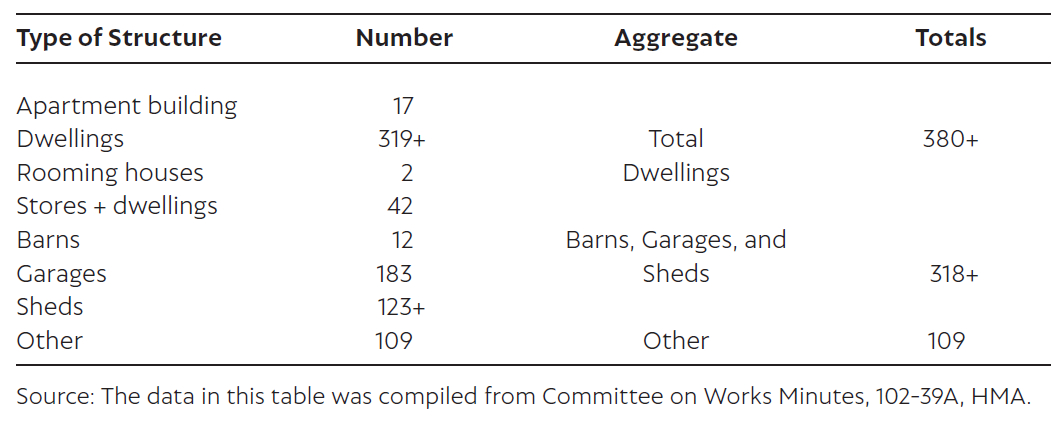

53 Unlike Ordinance No. 50, demolitions under the city charter were not limited to dwellings, but included all buildings. Table 3 and figures 5, 6, and 7 have been compiled from summaries of demolitions for the years 1958-1963. The figures are incomplete (especially for 1962), but they are nevertheless revealing of the geography of demolition undertaken by the city largely outside federally funded redevelopment areas like Jacob Street. The city demolished dwellings in the older parts of the city, particularly north of the Jacob Street redevelopment area, in the North End, including Maynard Street and Creighton Street. Unsuccessful in their earlier efforts at slum clearance, municipal authorities chipped away at that area through their application of the city charter.

54 In addition to targetting substandard housing, the Works Department also had its building inspectors identify barns, garages, and sheds – nonresidential buildings – for demolition. Although these buildings were dispersed throughout the peninsula, like the residential dwellings targetted for demolition they too were concentrated in the North End. Ridding the area of such buildings was meant to reduce the costs of redevelopment. When the city began the process of acquiring properties in the North End as part of the Uniacke Square redevelopment project, it would not have to pay out quite as much if it had already made owners get rid of at least some of their dilapidated buildings. Given that the city and the federal government shared the costs of acquisition and clearing equally, municipal officials were likely interested in any economies they could achieve.

Display large image of Table 3

Display large image of Table 355 Although municipal officials were aware as early as April 1958 that Halifax’s most vulnerable residents were losing their housing to redevelopment, they were hard-pressed to know exactly how many. In part, this was because of the speed with which properties were acquired and demolished in the first year of the Jacob Street redevelopment: one alderman noted that 110 people had been put out in a single night when the city demolished 15 buildings.71

56 Gordon Stephenson estimated that implementing all his recommendations would result in the displacement of approximately 6,000 people, but that figure did not include those who lost their homes to the municipal demolition program. The city’s best guess was that 1,770 families would be rendered homeless from 1958 to 1960 thanks to the combined effects of its redevelopment program as well as the enforcement of Ordinance No. 50 and the provisions of the city charter. Daunting as that number was, it did not include those who were displaced by private development; the city’s director of welfare, H. Bond Jones, estimated this number to be 500.72

57 While rehousing families displaced by redevelopment was a condition of receiving federal funding, they numbered just 407.73 Public housing was meant to take care of them, but construction on Mulgrave Park (348 units) was alarmingly slow and not all displaced families were deemed fit by the housing authority to be accommodated as they failed to meet its normative standards of respectability or its income thresholds.74 The first who did were not able to move in until just before Christmas in 1960, and the project was not completed until June 1961, more than three years after the Jacob Street redevelopment project had started. In any case, Bond Jones insisted the city needed at least ten times as many units, some 4,000, which “will be taken up as fast as the contractor can get them over.”75 The city, backed by the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), took a very different view and insisted that it only needed to provide housing for one out of every four families displaced.76

58 Halifax had a “housing emergency” on its hands, one largely of its own making.77 Although Gordon Stephenson had insisted “it will not be possible to carry out the redevelopment schemes in the Study Area without first providing housing on three sites in the northern part of the city,” the city had completed just one by 1961, Mulgrave Park, and had just come to an agreement with the federal government about a second, to be called Westwood Park (209 units).78 While the loss of Halifax’s housing stock hit all poor and working class residents hard, Black Haligonians had a particularly difficult time finding alternative shelter. As W.P. Oliver told the Committee on Works in 1958, when it ordered the house at 175 Creighton Street demolished under s. 757, racism prevented its tenants – members of his congregation – from being rehoused. When they “attempted to obtain other quarters they were quite successful on the telephone but when they went to the property, they were told it was occupied.” In his view, “unless some solution was found, his parishioners would wind up on the street.”79 Municipal authorities agreed, acknowledging the problem “was particularly acute with coloured families, to whom alternative housing is extremely limited.”80 The building came down nevertheless (Figure 8).

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

59 Incidents like these led H.B. Jones to report the following:

Some families ended up sleeping in their cars or “putting up little shacks, or they are moving into somebody’s two-car or one car-garage” in the city and, increasingly, outside it.82 The welfare officer estimated that 200 families were leaving Halifax every month. “We have pushed hundreds of families all over Halifax County. We have them living in Digby, many in Cape Breton; we have them as far as Windsor and beyond. We are driving these people out.”83

60 In addition to homelessness, eliminating substandard housing had the effect of creating overcrowded conditions in the remaining housing stock. Estimates were that at least 1,000 Halifax families were living in one room in 1959.84 The irony of urban redevelopment creating new slums was not lost on some in municipal government, including Mayor Charles Vaughan: “The houses being torn down were certainly not fit accommodation but at least they were shelters for some people.”85

61 The solution, articulated by more than one alderman, was to slow down the demolitions and to coordinate them with the availability of new housing. 86 That did not happen. Indeed, the local press thought things were going too slowly. By failing to hire more staff to speed the inspection process, the city was letting landlords “escape penalties and avoid being compelled to make their properties fit for human habitation.”87

62 Despite the fact the city knew it was creating a housing emergency and its Works Department was stretched thin doing inspections, it seemed impossible to stop the municipal wrecking ball once it was in motion and the vista it had partially revealed – of a modern, prosperous city – was visible.

63 Looking north from Jacob Street, you get a different perspective on Africville. Slum clearance there unfolded in a strikingly different way than it did elsewhere in the city. Municipal officials were explicit in their intention to “deviate from the strict letter of the law” in acquiring properties and relocating residents. They chose not to pursue an agreement with the other levels of government under the NHA to clear the area, nor did they apply Ordinance No. 50 or the provisions of the city charter to rid it of substandard buildings before entering into negotiations with residents.88 Instead, they came up with new and different procedures to acquire land and property in Africville, ones that were more liberal than those used in the rest of the city.

64 Rather than restrict compensation to those who could prove legal ownership, municipal authorities decided to compensate all residents who claimed it: it negotiated with those who had deeds to the properties they occupied and those who did not – who in fact made up the majority. It also paid any municipal taxes residents owed and cleared their accounts at the Victoria General Hospital.89 The decision to take a broad approach to compensation meant the city could not enter into a redevelopment agreement with the other two levels of government: the National Housing Act only allowed for the compensation of people who had formal, legal ownership of the properties slated for acquisition and clearance.90

65 Having decided to dispense with the usual requirement for proof of ownership, the city also dispensed with the usual personnel and the formula it had used in coming to settlements in its other redevelopment areas. It hired a social worker to deal with Africville residents, acknowledging that different sensitivities and skills were required to acquire their properties and relocate them. Peter MacDonald’s job was taxing, but his caseload of some 80 families living on 13 acres was less than that of C.D. Smith who, as Halifax’s sole compensation officer, was charged with buying properties in the rest of the city’s redevelopment areas. Unlike Smith, MacDonald was empowered to compensate those without property as well as those who were tenants, boarded, or lived with relatives – something that again spoke to the different approach the city took.

66 In addition, MacDonald’s recommendations for compensation were sent to a special Africville Subcommittee of City Council for review and approval rather than to the Redevelopment Committee. Its membership included two African Nova Scotian members of the Halifax Human Rights Advisory Committee, the advocates for the community, as well as the usual representation of aldermen.

67 Finally, municipal authorities agreed to help relocated residents find jobs, get the kind of education that would qualify them for better ones, and gain access to capital. They hired a job placement officer dedicated to the task, and organized night school classes aimed at getting Africville men to the level they needed to qualify for trades training.91 In addition, the city’s Social Planning Department helped establish the Seaview Credit Union, with a board of directors that included 11 former Africville residents. Designed to make loans available to former residents, it was for a time a positive force in stabilizing the financial circumstances of some families and in “providing a valuable social development experience, through participation in the decision making of the Credit Union operation.”92

68 As was the case with others who were displaced by redevelopment and demolition, the city also helped Africville’s residents find alternative accommodation. But the lengths it sometimes went to were extraordinary. For instance, it purchased a house on Gottingen Street for one couple, allowing them to rent it a rate they could afford, and it paid some unexpected repair bills on a house purchased by another former Africville family.93

69 All this raises the question of why the city of Halifax treated Africville differently. Perhaps it was simply being consistent: Halifax officials had always treated Africville differently, whether it was by failing to provide it with piped water, connect it to the sewer system, or sort out property ownership for the purposes of taxation. But those differences stemmed from inaction, from more than a century of neglect borne of racism. The divergent practices it followed in acquiring property and land in Africville required the city to expend more money and effort in compensation than it otherwise would have had it stuck to “the strict letter of the law.” Since only a handful of residents had deeds to their properties, the compensation paid out would not have been very much; certainly it would have been less than the more than $600,000 it expended.94

70 Rather than neglect, the course of action the city pursued in Africville seems to have been prompted by a sense of embarrassment. Racism, classism, and its location at the far north end of Halifax combined to put Africville beyond the pale of the city’s concern for much of the 20th century. But as attitudes began to change in the postwar period, thanks in no small part to the civil rights movement in the United States, Africville became an a source of shame. National and international coverage shed unfavourable light on race relations in Nova Scotia, and it became harder to ignore the situation in the neighbourhood. Writing for the New York Times, Raymond Daniell noted “there are no ‘White Only’ signs in this seaport, the capital of Nova Scotia, nor do Negroes have to go to the back of the bus.” But the province nevertheless had a “racial problem.” In his view “a sort of self-imposed segregation exists among a docile colored population.” Maclean’s Magazine agreed, calling Africville “the Black ghetto that fears integration.” Mary Casey informed readers of the Globe and Mail about the racial segregation in Halifax, noting that Africville was “worse than any blighted area already demolished by the city.”95

71 To the shock of many Canadians, Nova Scotia seemed afflicted by the kind of racism they associated with the United States. One of them, Mrs. Fleur Campbell, was so enraged by what she read that she urged “an economic boycott of Nova Scotia until integration of Africville into the White city of Halifax is effected – with the help of the RCMP if necessary.” Campbell might have been thinking of Norman Rockwell’s then-recent painting of six-yearold African American Ruby Bridges being escorted to her desegregated school in New Orleans by federal marshals. Haligonians Mildred Millar and Leah Epstein, members of the Inter-Racial Council, took issue with the parallels drawn between racism in their city and that in the United States.96 Both wrote to the Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star to assure readers that “while things are very far from perfect here . . . Halifax will not be another Selma,” referring to the violence that had been visited upon civil rights activists who tried to march from that Alabama city to the state capital of Montgomery in 1965 to demand the right to vote for African Americans.97 As Scott Rutherford argues in terms of anti-Indigenous racism in 1960s Kenora, Ontario, Canadians commonly associated racism with the United States. Doing so was an assertion of anti-Americanism and nationalism, and, among other things, served to perpetuate the idea that racism, when it occurred in Canada, was aberrant, localized, and not part of the country’s history.98

72 Regardless of whether Halifax was another Selma, Alderman Abbie Lane believed Africville had become “a blot” on the city’s reputation visible beyond its borders.99 The community was obvious in a way it had not been before. The continuing existence of what looked to outsiders like a racially segregated “ghetto” was evidence that Halifax was not a “modern metropolis.”100 Among other things, a modern city was an integrated city. Even Black community advocate Reverend W.P. Oliver supported the destruction of Africville and the relocation of its residents – this despite the fact he had opposed the redevelopment of the North End because it would create housing insecurity for the African Nova Scotians who lived there.101

73 In light of the embarrassing reports about Africville and the shifting attitudes about racism informing them, municipal authorities were moved to act. For the city’s Development Department, integrating Africville’s residents was a “social necessity.” In acknowledging but denying residents’ request that arrangements be made for them to continue to live together after the relocation, municipal authorities argued “the City is a comprehensive urban community and it is not right that any particular segment of the community should continue to exist in isolation.” As well, there were practical reasons for integrating Africvillers: the CMHC would not fund segregated housing, and even if it agreed to such a project authorities argued that it probably would not be economically feasible. Given the level of poverty among the neighbourhood’s residents, it was unlikely that a separate public housing facility would generate the kind of average monthly rent that was necessary for it to operate financially.102

74 In addition to shifting attitudes about segregation and the acceptability of overt racism, the differential treatment of Africville’s residents also arose from an acknowledgement of the city’s longstanding neglect and the community’s “historicity.”103 Authorities admitted that doing nothing “has been the basic approach for over 100 years”; a statement that was the closest they came to recognizing the city’s responsibility for creating conditions in Africville. As well, the city may have been swayed by the fact many of its families had lived in the area for generations; this was acknowledged by both housing expert Albert Rose, who advised the city on Africville, and Gordon Stephenson, who claimed a kind of indigeneity for residents when he argued they were “old Canadians.” Certainly, in justifying the course of action it took in acquiring land for redevelopment, the Development Department recognized residents had lived there for “generations” and argued its actions were in the interest of “history and fair treatment.”104

75 In short, the city’s differential treatment of Africville was borne of embarrassment about segregation and was a reaction to the racism that had created it. The course of action it pursued did not result in better outcomes for all residents, but it is nevertheless significant. How the city chose to treat Africville sheds light on the power of the shift in attitudes about one particular manifestation of racism that was emerging in the early 1960s – and the limits of the critique that came from that shift. Both the city and the community’s advocates were motivated to take the action they did in Africville because racial segregation had become increasingly unsupportable, an issue of civil rights.

76 More numerous than Africvillers, the Black residents of the North End who were displaced by renewal garnered no such consideration. Racial segregation may have been unacceptable, but anti-Black racism still was. Despite their greater numbers and their poverty, they were geographically integrated into the city. Although municipal authorities acknowledged the difficulties Black Haligonians experienced in securing alternative housing, they were not moved to act differently. Indeed, they refused to even slow down the demolitions or coordinate them with the availability of housing.

77 The concern with the spatial expression of racism – with segregation – was consequential. Not only did it result in the differential treatment of Africville’s residents, but it also obscured other manifestations of anti-Black racism and the diversity of experiences Black Haligonians had with urban redevelopment. Equally importantly, it rendered the classism that characterized urban renewal invisible to both municipal authorities at the time and scholars of Halifax since then. Like the other areas in the city slated for redevelopment, Jacob Street and the North End were class-based ghettoes (Figure 9). Their White residents may have fewer difficulties in securing alternative housing than their Black neighbours, but redevelopment still disrupted their lives fundamentally. Ultimately, urban renewal in Halifax amounted to shovelling out the poor, whose vulnerability to displacement then and now was configured by both class and race as well as the ongoing power of the Africville story.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

TINA LOO enseigne l’histoire canadienne et l’histoire de l’environnement à l’Université de la Colombie-Britannique. Son dernier ouvrage

est Moved by the State: Forced Relocation and Making a Good Life in Postwar Canada (Vancouver, UBC Press, 2019).

TINA LOO teaches Canadian and environmental history at the University of British Columbia. Her latest book is Moved by the State: Forced Relocation and Making a Good Life in Postwar Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019).

Notes