Historiographic Commentary / Commentaire Historiographique

The Hidden Life of Monuments:

Reflections from the Lost Stories Project

1 SINCE 2012 I HAVE BEEN WORKING WITH historians, educators, artists, and filmmakers to develop the Lost Stories Project, which seeks from the public little-known stories from the Canadian past, gives these stories to artists who transform them into inexpensive pieces of public art on appropriate sites, and documents the artists’ creative process through the production of short films.1 When I came up with the concept for the project it was largely in the context of my own research over the past 15 years, which had explored the public representation of the past in both Quebec and Atlantic Canada with a particular emphasis upon the backstory that is usually impossible for the casual observer to perceive.

2 In the case of Quebec, I examined the public memory of Samuel de Champlain and Mgr. François de Laval, generally viewed as the founding fathers of French-speaking Quebec: one the secular father (responsible for the settlement at Quebec City) and the other the religious founder (the first Roman Catholic bishop of Quebec).2 In regards to Atlantic Canada, I focused my attention on efforts in the early 21st century to commemorate both the founding moment for Acadians – the attempt to establish a permanent settlement on Île Ste-Croix in 1604 (so four years before Quebec City) – and their moment of trauma – the deportation of the Acadians between 1755 and 1763, or what they call “le grand dérangement.”3

3 I learned from these projects what others have also observed: namely, that public remembrance of the past – through such tools as the construction of monuments – is really as much – maybe more – about the people who had the power to erect them than they were about the individuals being honoured. This point was convincingly made by Kirk Savage in his Monument Wars, which explores the commemorative landscape on the National Mall in Washington. Savage paid particular attention to the Washington Monument, the huge obelisk completed in the 1880s that bears no iconography that would directly link it to the first president of the United States. From Savage’s perspective, however, there was nothing odd about this situation because “this was indeed a ‘modern monument’ that had nothing to do with George Washington and his agrarian world. It was a monument to technocratic wisdom and bureaucratic efficiency, seemingly accessible to a democratic people yet remote from their experience and understanding.”4

4 But while there is a large scholarly literature that tries to tease out why and how some individuals are commemorated in public space (and others are not), sometimes this is simply not possible due to a lack of sources. In my own research, for instance, I was unable to find the minutes of the committee responsible for creating Quebec City’s monument in honour of Champlain, which was unveiled in 1898 only metres from the Château Frontenac. One report indicated that those minutes had been sealed inside the monument’s pedestal.5 More broadly, Savage has pointed to the challenges of such research since the archives provide only “a scattered record. Sometimes monument committees are very proud of themselves, and they publish their proceedings and then there are more records and archives. Other times they’re just lost entirely.”6 In this context, I imagined that Lost Stories could provide a solution since I would be able to watch the entire process unfold.

5 What I could not have imagined in 2012, however, was that monuments were about to take centre stage in heated public debates across the globe, mostly prompted by demands for the removal of structures connected with now-disgraced individuals or deeds. By and large, these debates have only reinforced my sense of the pertinence of Lost Stories. As we will see in the following section of this short essay, the controversies surrounding such monuments as those dedicated to Confederate heroes in the American South have dealt only superficially with these structures and have largely ignored the context in which they were erected in the first place. Then, in the subsequent sections, I will return to Lost Stories to discuss what I was able to learn about the process of memory-making from being on the inside.

“There is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument.”

6 What do we see when we pass by a monument in a public space? Some people see nothing, providing evidence to support the often-cited observation by the Austrian philosopher Robert Musil: “The remarkable thing about monuments is that one does not notice them. There is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument.” He goes on: “One must walk around them every day or use their pedestals for protection; one uses them as a compass or a rangefinder if one is heading towards a well-known square. One experiences them as a tree, as part of the scenery, and would stop in momentary confusion should they be missing some morning.”7

7 Musil made these comments in 1927, at the tail end of a spectacular period of monument construction across the Atlantic world – what Maurice Agulhon called a period of “statuomanie.” To take only one example of the intensity of this spurt, in Quebec there were only three monuments in public space in the 1880s – a figure that reached 177 by the early 1920s. This commemorative activity formed part of a larger engagement by leaders, both secular and clerical, who were involved in the process of creating what Pierre Nora has called “les lieux de mémoire,” filling a void “at the end of the [19th] century, when the decisive blow to traditional balances was felt – in particular the disintegration of the rural world.”8 Through the construction of monuments, but also the staging of large historical pageants and the creation of historic sites and museums, the past was employed as a “compensatory strategy” to mobilize support for such constructs as the state and the nation.9

8 In this context, as history took centre stage, Musil believed that monuments, once they became part of the landscape, no longer attracted the public’s attention, no matter how much care may have been invested by its proponents to consider the site selected as well the structure’s form, iconography, and inscription. But was his observation accurate? It played into the sense that the public was not particularly engaged with the past, a perspective that was effectively challenged 20 years ago by Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen in their path-breaking book The Presence of the Past. Interviewing nearly 1,500 Americans, they found that nearly all of their respondents were involved in activities connecting them to the past. Simply put, they found that “people pursue the past actively and make it part of everyday life.”10

9 In the 20 years since the publication of Rosenzweig and Thelen’s book, the engagement of the public with monuments has become particularly visible due to the heated controversies regarding the appropriateness of honouring such individuals as Robert E. Lee – the general of a breakaway state that was committed to slavery in the American South, John A. Macdonald – Canada’s first prime minister who was also closely connected with the introduction of residential schools, and Edward Cornwallis – the governor of colonial Nova Scotia who offered a bounty for the scalps of Indigenous people. In a sense, however, these controversies have only made more pertinent than ever the question of what people actually see (or do not see) when they look at a monument; or to put the matter slightly differently, if monuments are not invisible, then what can they tell us about the past?

10 On one level, monuments can be read literally as objects presenting the lives of noteworthy people. While there can be differences of opinion as to the meaning of those lives, recent debates have tended to focus – often with little attention to the features of the structures – on whether these individuals warranted a special place in public space. By ignoring the particular form of the monuments, these debates have ironically made the structures less visible while serving as the starting point for referendums on the lives of the subjects.

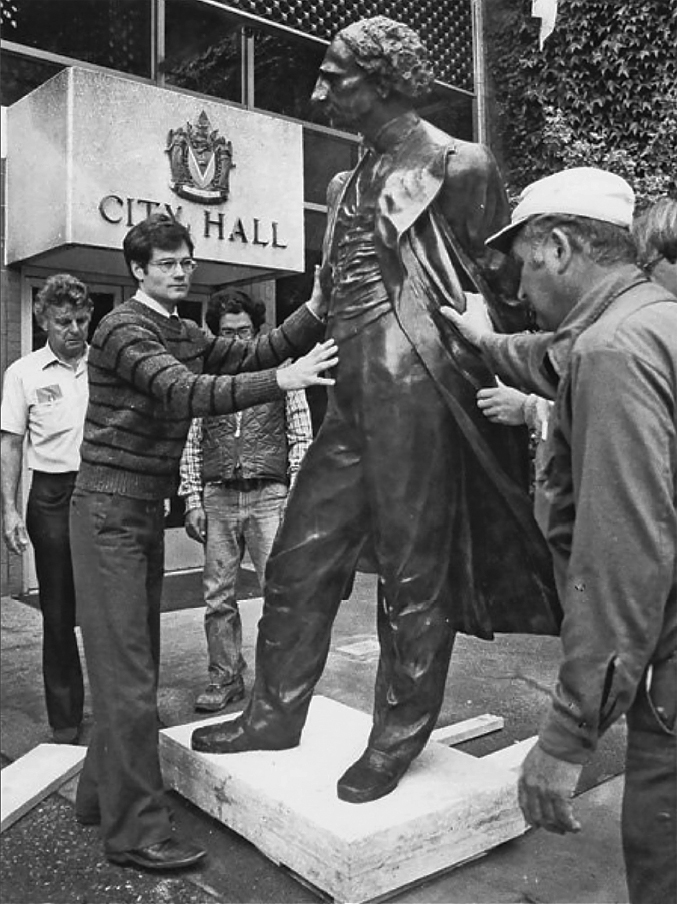

11 To take only one example of what these exchanges usually look like, let’s turn to the debate over the removal of a statue to John A. Macdonald at the entrance to Victoria’s City Hall during the summer of 2018. Katie Hooper, executive director of the Esquimalt First Nation, applauded the removal “as an important step in the city’s reconciliation journey, a symbol of progress towards an end to discrimination and oppression.” By contrast, John Lutz, a professor of history at the University of Victoria, was much more cautious: “The story that John A. Macdonald tells is multiple stories. There’s a story about the founder of Canada, who could be celebrated, there’s a story about the Member of Parliament from Victoria, who should be remembered, and then there’s the story about the man who helped formulate the Indian Act and was part of the colonial process in Canada that we have to remember and not celebrate.”11

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

12 Neither Hooper not Lutz had anything to say about the Macdonald statue per se. In debating Macdonald’s life – and not the physical object designed to represent him – the monument disappeared from the discussion, leading to a response from its sculptor, John Dann (pictured above), who felt that his 1981 work had been misread or, more accurately, not read. He pointed out that the statue was “not a representation of a single person, but it is a work of art representing all humanity. . . . We have here the strengths and flaws of Macdonald and our ourselves.”12

13 It is hard to understand how this rather literal presentation of Macdonald is not about Canada’s first prime minister, but Dann’s intervention is a useful reminder that there was an object under discussion that only represented an individual and was not the individual himself. His response, moreover, points to a tendency to see the story being told by such a structure as fixed, which is perhaps understandable given that we are dealing with objects chiselled from stone. Nevertheless we sell such structures short in viewing them as if they did not form part of a larger landscape that can change over time, in the process changing their meaning.

14 As Kirk Savage explains, “The world around a monument is never fixed. The movement of life causes monuments to be created, but then it changes how they are seen and understood. The history of monuments themselves is no more closed than the history they commemorate.” To make this more explicit, Savage points to Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia; it saw the construction – during the era of statuomanie – of a series of monuments in honour of Confederate generals and leaders, including one to Robert E. Lee. Savage describes how this commemorative landscape was designed to “strengthen a canonical narrative of the Confederate past – a saga of white valour and statesmanship.” But the meaning of this story was transformed with the construction on Monument Avenue in 1996 of a structure to commemorate Arthur Ashe, the African American tennis player, campaigner for AIDS education, and native of Richmond: “Now the procession of Confederate heroes, icons of white supremacist rule in Richmond, culminates ironically in an emblem of exactly the sort of black citizenry the Confederacy feared, outlawed, and fought.”13

15 But even if we recognize that the story suggested by a monument can change, it still keeps from view the real reason why it even exists. One of the more troubling aspects of the most recent debates about the removal of monuments is that such controversies tend to keep the focus on the individuals being remembered and, in the process, keep out of view the motives of those who created the structures. While our eyes are drawn to the actions of Lee, Macdonald, and Cornwallis, we are only discussing them because there were individuals who had the power to install structures in prominent public spaces and who were motivated to act for reasons that had much more to do with the times in which they lived than those in which their heroes did. In a very real sense, these are monuments to their creators, maybe more than they honour the subjects on their pedestals.

16 To make this more concrete, take the case of the protests against the monuments to Confederate heroes such as Robert E. Lee; such protests only rarely recognized that these structures were not entirely about the leaders of the Confederacy. As Eric Foner has explained: “Like all monuments, these statues say a lot more about the time they were erected than the historical era they evoke. The great waves of Confederate monument building took place during the 1890s, as the Confederacy was coming to be idealized as the so-called ‘Lost Cause’ and the Jim Crow system was being fastened upon the South, and in the 1920s, the height of black disenfranchisement, segregation, and lynching. The statues were part of the legitimation of this racist regime and of an exclusionary definition of America.”14

17 Similarly, in regard to the Cornwallis monument in Halifax, John Reid has shown that “in important respects, it had only limited connections either with history or even with the city of Halifax.” Rather, the drive to have Cornwallis commemorated in the early 1930s spoke to interest in promoting the imperial connection and – maybe even more importantly – providing an anchor for a park that was constructed by the CNR in front of its new hotel while in the process adding to the city’s attractiveness to tourists. As Reid put it, the movement that led to the construction “was governed not by history, but by a potent mixture of imperialism, a racially-charged triumphalism based on the savagery-civilization binary, state promotion, and an economic agenda.” Connections to the more distant past were “strictly coincidental.”15

18 Robert Musil, in his focus on the physical structure, missed the link to its creators. As he put it, “What becomes harder and harder to understand the longer one thinks about it is why are monuments erected to great men.”16 But, of course, these monuments were not entirely designed to commemorate the “great men.” And this inability to grasp the deeper roots and meanings of a monument continues nearly a century after Musil wrote his essay. In fact, the heated debates over the past few years have only served to keep the roots of the monumental landscape in the shadows. It has been as if the intensity of the conflicts has prevented participants from recognizing that the stakes are much deeper than the validation of the individuals displayed on the monuments.

19 As a case in point, in the fall of 2018 Duke University Press published a 20th-anniversary edition of Sanford Levinson’s Written in Stone: Public Monuments in Changing Societies. Designed to coincide with the recent controversies, this edition includes a lengthy afterword that focuses on the subjects that the monuments commemorated but provides little commentary on what they represented for those who had created them. His preoccupation, as Levinson himself put it, was with determining if it was possible to honour individuals, such as Cecil Rhodes, Woodrow Wilson, and Robert E. Lee, whose lives may have had “personal achievements,” but also aspects that were “outright discreditable and even despicable.”17

20 By focusing on the surface meaning of monuments, Levinson missed an opportunity to go to the root causes that had led to the creation of such structures in the first place. Recognizing the power of the physical object to distract us from focusing on its larger meaning, Savage observes “A funny thing happened once a monument was built and took its place in the landscape of people’s lives: it became a natural fact, as if it had always been meant to be. . . . Public monuments exercised a curious power to erase their own political origins and become sacrosanct.”18 In that regard, the visibility of monuments helps contribute to the invisibility of their origins.

Finding Lost Stories

21 In order to make the origins and meanings of a monument more transparent, the Lost Stories Project – after completing a pilot episode in 2013 – received funding in 2016 from the federal government’s Canada 150 fund to solicit four stories from Canadians living in the country’s different regions, to commission artists to create public art telling those stories on appropriate sites, and to select filmmakers who would document the artists’ creative process. The project has also developed educational material that allows high school teachers to challenge their students to think about why some stories (and not others) are “lost,” and to ask them to think about how narratives other than the ones created by the artists and filmmakers might have been developed. Lost Stories allowed me to become part of the production process in order to understand it better; I abandoned my earlier role as the distant observer trying to explain the creation of historical markers from earlier times.19

22 Lost Stories was funded by the federal government, as part of its efforts to mark the country’s sesquicentennial in 2017. Ottawa provided $235,000, but never asked about the stories we selected and whether they were sufficiently celebratory for the anniversary being marked.20 Indeed, because we were trying to give attention to stories that had been “lost,” they tended to be connected with events that had previously been brushed aside, precisely because they dealt with painful episodes from Canada’s past.

23 In total we received more than 150 stories that came to us through a variety of channels, from which four needed to be selected so that the different regions of Canada would be represented. Fairly quickly, in poring through the submissions, the question arose as to what constituted a “lost” story since – as I was frequently reminded by our collaborators – if no one knew the story, then it would never have been found. In the end, however, we did not spend a lot of energy over defining lost, and rather focused on finding stories that gave voice to communities that had not always had an opportunity to tell their own narratives. Given this orientation, the involvement of those communities in the process was crucial because we definitely did not want to be telling stories about other people’s pasts.

24 In addition, the selection of stories was dependent on finding ones that could be commemorated on a meaningful and accessible site – an issue that emerged as a significant problem in regard to our story from Atlantic Canada (but more on that below). I imagine that this had been less of a problem for telling the stories of “great men,” whose backers tended to be well-connected members of the community. We were committed to giving our artists – once selected from open competitions – complete freedom (subject to the budget provided), which meant that it was impossible to know in advance what any given piece of public art would look like. In several cases, this turned out to be a problem because local government officials refused to provide carte blanche for artwork on public space, eliminating stories that had definitely been lost.

25 In the end we were sent relatively few stories that actually pertained to people who had been marginalized, that had the support of the pertinent communities, and that could be installed on an appropriate site. These considerations led us to tell the chilling story of individuals with leprosy (mostly Acadians), who were confined to Sheldrake Island in northeastern New Brunswick in the 1840s; the complicated story of Inuit travelling from the North who made a home for themselves in Ottawa’s Southway Inn; the inspiring story of Yee Clun, a Chinese Canadian businessman from Regina who in the 1920s challenged Saskatchewan’s White Women’s Labour Law that had prevented him from hiring such women to work in his café; and the heart-wrenching story of boys from the Stó:lō First Nation who were kidnapped by American miners during the British Columbia gold rush of the 1850s.

26 Once the stories were selected by the Lost Stories team, the search began to find artists to create commemorative works on the sites we had secured and filmmakers who would shadow the artists to allow viewers to see the twists and turns that take place in creating public art. In regard to both the artists and filmmakers, we insisted on engaging individuals who had some connection to the story, usually by way of belonging to one of the communities depicted. More broadly, these communities were given the opportunity to play lead roles in the process of selecting the artists and filmmakers and staging significant public events to inaugurate the artwork. This was most evident in the episode connected with the Stó:lō First Nation, which took the lead in all aspects of the process, telling its own story, and not having it told by others. In this regard, the project provided a small step towards reconciliation and de-colonization.

Sheldrake Island

27 With the stories selected and the artists and filmmakers in place, the process of creating commemorative markers began. But for the remainder of this essay I will focus on what I learned from being on the inside of the process in regard to our project in New Brunswick, which focused on telling the story of people with leprosy on Sheldrake Island. I shared the responsibility for looking over the four projects with my colleagues John Walsh (who was the lead for the story in Ottawa) and Keith Carlson (who did the same for the one in British Columbia). In addition to taking the lead for the project in Saskatchewan, I was glad to do the same for the one in New Brunswick; the latter conveniently dovetailed with my own research in the province over the past 15 years.

28 Within days of the launch of our call for stories, we received a carefully prepared dossier from Commemoration Sheldrake, a group of individuals who lived along New Brunswick’s eastern coast between Miramichi (near to where the island is located close to the mouth of the Miramichi River) and Tracadie (from which many of the individuals who were confined to the island were sent). The group was bilingual, but my first contact was with the Acadian members who had long had a connection with preserving the memory of the impact of leprosy in this part of the province.21

29 The story of leprosy in northeastern New Brunswick has been told by others, most notably Laurie Stanley-Blackwell.22 For reasons that are not entirely understood even today, leprosy came to this part of the province in the late 18th century. The disease carried with it a stigma due to the physical deformities that it caused and the fear that it generated since there was no treatment for leprosy at the time. By the 1840s, officials in New Brunswick were sufficiently alarmed by the persistence of the disease, particularly in the Acadian peninsula, that they decided in 1844 to send all those with leprosy to Sheldrake Island. There they endured terrible conditions, leading some to try to escape and leading authorities to turn the lazaretto into a site that resembled a prison by installing guards following the burning down of the buildings by those interned there.

30 Most of the individuals sent to Sheldrake Island (or Île-aux-Becs-Scies) were Acadians, whose leaders lobbied to have a proper lazaretto established closer to the communities that had been most affected.23 As a result, in 1849, after 32 individuals had been sent to the island, 15 of whom died, the survivors were evacuated to Tracadie; a proper lazaretto was established there, which went on to treat people with leprosy until its closure in 1965. Today there are cemeteries in Tracadie-Sheila, both to patients who died at the lazaretto and to the Sisters, members of the Congrégation des Religieuses Hospitalières de St-Joseph, who attended to the ill; and there is also the Musée historique de Tracadie, which focuses on the history of the town’s lazaretto. In contrast with the strong public memory in the region of what happened subsequent to the Sheldrake Island tragedy, however, the episode on the island had become “lost.”

31 Even though I had just finished a project on the creation of Kouchibouguac National Park, whose northernmost boundary is only about 40 kilometres from Sheldrake Island (as the crow flies), I knew nothing of that particular aspect of the leprosy story when it landed in my inbox. Nevertheless, I immediately understood why it was important, particularly to the Acadian members of Commemoration Sheldrake, to have the story told. One of the things that I learned both from my Kouchibouguac project, and a previous one dealing with the public memory of the founding of Acadie in 1604 and the grand dérangement 150 years later, is that Acadian leaders are determined to have their own stories told after long having been denied that opportunity. They shared this trait with the other communities with which we worked in 2017.

32 In terms of the founding of Acadie, Acadians were determined – on its 400th anniversary in 2004 – to come out from the shadows created by the Québécois insistence that the French Canadian experience had begun with Champlain at Quebec City in 1608. For them, the “founder’s” name was Dugua, and the location was Île Ste-Croix. As for the memory of their deportation, they insisted on a public recognition of what had happened beginning in 1755, leading to a royal proclamation that wrongs had been committed and the declaration that 28 July – the date in 1755 on which the decision was taken to remove the Acadians – would henceforth be a “Journée de commémoration du Grand Dérangement.” In neither case did the Acadian leaders achieve all that they wanted: there was no apology and some would have preferred that the day for commemoration had been on the date when the forced removals began. Nevertheless, their stories were being told on a public stage as they had never been told before. 24

33 Similarly, in terms of Kouchibouguac, I discovered a community – mostly made up of Acadians – which was eager to put its story on the record. When the park was created in the late 1960s and early 1970s, no one asked any of the more than 1,200 people who were removed from their homes whether this was what they wanted. The removal of the resident population was part of Parks Canada procedures at the time, and so there was no reason to have asked the residents for their perspective. Nevertheless, this was another case of removal (although not carried out as forcefully as the one in 1755), and over the years resentment had grown about how they had been subjected to what was often called “une deuxième déportation.” When I began doing interviews with former residents in that context, after getting beyond suspicions about me being an outsider asking about their lives, I found a community that wanted to put its story on the record.25

34 In this context, I was not entirely surprised when I was warmly welcomed on a site visit to the Acadian Peninsula in the fall of 2016, during which I was kindly housed and fed by members of the committee. But what struck me the most was how they had carefully choreographed the day we had together during which they introduced me to the story of leprosy on Sheldrake Island. The journey began in Tracadie-Sheila, where I was given the tour of the existing markers of public memory of leprosy – specifically the museum and the cemeteries. But we also spent time along the water, where people with leprosy had been placed on boats en route to Sheldrake Island 65 kilometres away; and the same experience was described to me during a stop at Neguac, halfway on the journey and the last stop before those with leprosy arrived at Sheldrake Island.

35 It quickly became clear to me that – much like the Kouchibouguac story – this one also needed to be understood in the context of the deportation. The point had often been made by Acadian leaders during the 1840s that while most of those with leprosy were Acadians, the site chosen by English-speakers for their internment was far away from their communities (such as Tracadie and Neguac) to the north. So when the boats took loved ones to some unknown location, it was inevitable that they were reminded of the boats that had done the same thing (with more tragic consequences) at places such as Grand-Pré less than a century earlier. In 1844 there would have been grandparents of the young people transported to Sheldrake Island whose own relatives would have lived through the grand dérangement, either having been deported or escaping to places such as the Acadian Peninsula. Stories of this trauma would still have been common in communities in the region in the mid-19th century, and here were the boats taking Acadians away once more.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

36 Ultimately our land journey ended at the Sts. Peter and Paul Church in Bartibog Bridge, from which Sheldrake Island can be seen. But there was still a journey on water as we went out to the island, where there was only one structure to indicate that a lazaretto had once been here; this structure – a well that had been constructed by those interned on the island – would have meant nothing to me if my hosts had not explained to me its story. The island was otherwise overgrown, except for a summer home that I was told was rarely used by someone who lived near Moncton (several hours away by car).

37 When the travelling was over, we sat around a table in the church hall, where the members of Commemoration Sheldrake told me that they had a site for a commemorative installation to honour the 15 people who had died on the island; it was the piece of land adjacent to the church from which the island could be seen. What they lacked were the resources to create the public art, and I had those resources thanks to Canada 150. On the face of it this was a marriage made in heaven, and I immediately recognized that we had found our story from Atlantic Canada.

38 In the weeks that followed we put out a call for artists and filmmakers, leading to our selection of Marika Drolet-Ferguson and Julien Cadieux – two young and already accomplished creators from the region. So everything was on track until I started receiving some odd phone calls, the first of which came from the individual who owned the island and who had learned of our visit to his property thanks to a photo in the local newspaper the Miramichi Leader.26

39 In part, the phone call was a response to our having “trespassed” on the island. In fact, I was told by my hosts that individuals in the area frequently stopped on the island, signing a book that was left for visitors to “check-in” inside the chalet. Indeed, it is a matter of law that the shore up to the high water mark on any island is public property to provide a safe stopping point for travellers in trouble. That being the case, the photo did not show us as intruders; but as the phone call continued, it became clear that it had more to do with public memory than our brief stop on the island.

40 The owner, an English-speaker, was troubled by the efforts of the committee, indicating particular annoyance with how the Acadian members were trying to make the story of what had happened on his island better known. During our conversation, he denied that 15 people had died on the island; this was in spite the fact that the research carried out by Paulette Robichaud of the commemorative committee, which is highlighted in Julien Cadieux’s film, established the names of the people who never returned. So if they never left the island, where could they be if not buried there? Connected to this question of fact, he expressed concern about efforts by Commemoration Sheldrake to have the island declared a national historic site, which would provide official recognition of a story that he did not accept.27 And, of course, he was also standing in the way of allowing Acadians to tell their story, which played into the question of voice that was so central to Lost Stories.

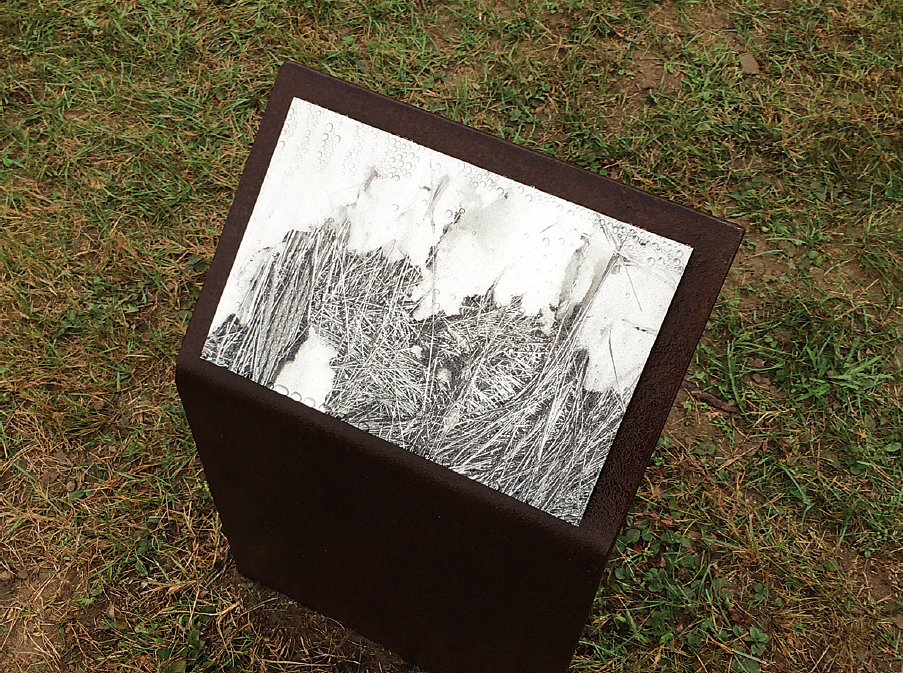

41 In the months that followed, Marika Drolet-Ferguson began to develop her project, often shadowed by Julien Cadieux. I instructed both of them to avoid going onto the island beyond the shore in order to avoid further conflict with the property owner, a tactic that seemed to work as we never heard from him again. Working with the group that had brought me the story, the artist developed a concept, building on her practice as a photographer, to create 15 markers (in a sense, substitute grave markers) along a trail that would end at the point at which the island could be clearly observed. Each of these markers would have a photograph of some aspect of the natural environment around the island in order to evoke a sense of what those interned on Sheldrake Island would have experienced, exposed as they were to the elements.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

42 And then there was a second phone call, this one in June 2017, roughly a month before the carefully scheduled inauguration of the project, on 19 July, the date on which the first individuals had been sent to Sheldrake Island in 1844. This call came from Bill Hicks, a senior official in the New Brunswick Department of Tourism, Heritage, and Culture. Even though the department had known of our project since the previous fall, it had chosen to wait until late May 2017 to confirm – as required by law – that there was no evidence beneath the surface to suggest that there had been an Indigenous presence. When an initial archaeological inspection was carried out, the results that were communicated to our partners and me indicated that nothing of significance had been found. Indeed, we were encouraged to go ahead with our planning – the archaeologist having gone so far as to ask our artist if she could be on hand on the day of the installation to assure that we would only be using land that had already been cleared.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

43 In that context, Bill Hicks called to tell me that the archaeologist had spoken too quickly and that further investigation was required because the initial results had been misread. This investigation ultimately confirmed that a significant and heretofore unknown Mi’kmaw encampment had been discovered. So we had managed to find two lost stories. Since the site could not be disturbed without appropriate consultation with the pertinent Indigenous interests, this discovery scuttled our location as well as plans to inaugurate the artwork on the date of the anniversary.

44 Our partners were determined to go ahead with a commemorative event on the anniversary date, regardless of whether the installation was possible, and so staged a moving ceremony at the Église St-Jean-Baptiste et St-Joseph in Tracadie-Sheila, leaving Sheldrake Island a bit in the shadows on what should have been its day to be featured. As part of the ceremony, a plaque, indicating the names of the 15 people who died on the island and which would have been installed at Bartibog, was inaugurated in the Cimetière des lépreux in Tracadie.

45 I decided to attend the event if only to find a new location for our 15 commemorative markers, which had already been produced so sure were we that everything was on track. En route from Moncton to the event in Tracadie-Sheila, I was met by Bill Hicks (of the phone call) to look at a possible location from which Sheldrake Island could (almost) be seen. The site he selected was in Loggieville, on the south shore of the Miramichi, roughly across the river from Bartibog Bridge (our planned site) and over a kilometre west of Sheldrake Island.

46 This site was clearly a step down, but I could not have anticipated the irritation it generated among our Acadian partners when I presented his idea following the commemorative events later in the day. They explained to me in no uncertain terms that the Loggieville side of the Miramichi had always been settled by English-speakers, while Acadians – going back to the aftermath of the deportation – had made their way up the coast, on the other side of the river. In that context, the Acadian members of Commemoration Sheldrake could not fathom remembering their ancestors in “foreign” land.

47 Our attention then turned to the question of where Marika Drolet-Ferguson’s installation could be installed in Tracadie-Sheila, where the story of leprosy already had a central place in public memory. Within a matter of weeks, we had access to a site that was sandwiched between the museum that already told the story, particularly in terms of Tracadie’s lazaretto, and the Cimitière des lépreux, where the plaque had been installed in July. Ultimately, in September 2017, the installation was inaugurated, following a moving and well-attended ceremony on a rainy day.

48 Our partners seemed content that the Sheldrake Island story was finally being told, and they reminded me that more people would probably visit the artwork in Tracadie-Sheila than would have been the case at Bartibog Bridge; this latter location is some distance from communities populated primarily by Acadians, who would be the most interested audience for the subject. Nevertheless, I know – even if visitors to the site might not (unless they had read this piece) – that that artwork was not designed to be installed in Tracadie-Sheila and that the island that was supposed to be, in a sense, part of the installation is 65 kilometres away. So if the point was to make Sheldrake Island visible, I am not sure if we entirely succeeded.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

49 Of course, the island is visible in Julien Cadieux’s film Sheldrake, but the story of the movement of the installation from its intended site is mentioned only briefly. This was the filmmaker’s choice, as we had promised all of them (much like the artists) complete artistic freedom. Anyone who sees this film (or his other films) will recognize a director whose creations have a poetic element.28 He was not attracted by telling a story of bureaucratic frustration for fear of losing the look and feel of Sheldrake. At my insistence, there is passing reference to the lost opportunity at Bartibog, but I suspect that the installation at Tracadie comes off in the film – as it does in person – as if it was natural. Much like those historians who need to remind the larger public that the Confederate monuments are really about Jim Crow, it is left to me to explain how the Sheldrake installation exists as a reflection of both Acadian persistence and of its limitations.

Stories told, lessons learned

50 In addition to the installation in Tracadie-Sheila, there are now commemorative markers telling little-known stories in Ottawa, Regina, and Hope, British Columbia. Unlike the monuments to great men, these are all located on sites somewhat off the beaten path but which have meaning for the communities whose stories are being told. The marker in Ottawa – an aluminum version of the qamutiik, the Inuit dog sled, by the Inuk artist Couzyn van Heuvelen, is located on the site of the hotel that provided a home away from home for Inuit travellers. In Regina, a photographic installation presents the story of Yee Clun, the Chinese-Canadian café owner who in the 1920s successfully challenged the province’s law that prevented Chinese business owners from hiring white women. His story is told in a park not far from Yee’s business through images created by Xiao Han, herself a Chinese immigrant to Saskatchewan. Finally, the story of Stó:lō boys who were kidnapped during the Fraser River gold rush is represented in the carving by Coast Salish artist Terry Horne; it depicts a boy and his father, trying (but not succeeding) to hold hands. The carving has been installed on land provided by the Chawatil First Nation on a site overlooking the river where one of the boys was taken away by American miners returning home.

51 Because these sites were under the direct control of parties (a retirement home, a community development organization, and a First Nation) that were committed to having the stories told, the construction of these three markers provided none of the surprises that occurred in regard to Sheldrake Island. Nevertheless, the films created by Mosha Folger (Qamutiik), Kelly-Anne Reiss (Yee Clun and the Exchange Café), and Sandra Bonner-Pederson (Kidnapped Stó:lō Boys) did not tell the full stories of the projects any more than did Julien Cadieux’s Sheldrake. As Jeff Webb has pointed out in a review of Lost Stories, while the films focus on the construction of these commemorative objects, “other creative acts – filmmaking and historical reconstruction are less exposed to view. . . . While we see the working methods of the artist, the methods of the filmmakers and the practices of historians are hidden from the viewer. . . . Is the story itself not a creation of the person who tells it, the historian who crafts it, and the filmmaker who shapes it out of sound and images that have been captured as digital data files?” 29

52 There are of course limits to what can be shown in film and still keep the viewer’s interest. This was precisely Julien Cadieux’s point in restricting the amount of attention to the problems that beset installation of the Sheldrake Island commemorative object. Nevertheless, Webb’s point is well taken. As we saw in regard to the monuments to contested individuals, public discussion of the meaning of commemorative objects tends to be superficial – focusing on the merits of the individual being represented and only rarely starting from the fact that these objects are simply representations created by individuals with stories of their own within a particular historical context. Lost Stories has tried to move behind the scenes, but we can go still further to draw back the curtain on the complicated process that shapes how the past is presented to the public.