Articles

“A Clarion Call To Real Patriots The World Over”:

The Curious Case of the Ku Klux Klan of Kanada in New Brunswick during the 1920s and 1930s

Le mouvement Ku Klux Klan au Nouveau-Brunswick dans les années 1920 et 1930 s’inscrivait dans une vague anticatholique qui déferlait sur le Nord-Est. Les liens présumés entre l’organisation américaine et des protestants locaux, tels l’Orange Order et des politiciens conservateurs, conjugués à la longue tradition d’opposition aux catholiques au Nouveau-Brunswick, indiquent que le nativisme du Klan n’était pas étranger dans la province. Plutôt, il faisait partie d’une réaction de toute la région à une population catholique prospère qui s’opposait au milieu protestant anglophone. Le « protestantisme patriotique » transnational du Klan rejetait le bilinguisme et la participation des catholiques dans la sphère politique, tout en faisant la promotion des valeurs traditionnelles anglo-saxonnes et de la moralité protestante.

The Ku Klux Klan movement in New Brunswick in the 1920s and 1930s was part of a wave of anti-Catholicism in the Northeast. The supposedly American organization’s connections with local Protestants, such as the Orange Order and Conservative politicians, coupled with New Brunswick’s long history of anti-Catholicism, indicate that the Klan’s nativism was not foreign to the province. Instead, it was part of a region-wide response to a thriving Catholic population that challenged the Protestant, anglophone milieu. The Klan’s transnational “Patriotic-Protestantism” rejected bilingualism and Catholic participation in the political sphere while promoting traditional Anglo-Saxon values and Protestant morality.

1 THE GROWTH OF THE KU KLUX KLAN IN NEW BRUNSWICK during the 1920s and 1930s reflected the transnational nature of early-20th-century anti-Catholicism in North America and the virulence of intolerance during this period. Its emergence coincided with the rise of hate movements across Canada, from the broader national presence of the Ku Klux Klan in Central Canada and Western Canada to the rise of fascistic organizations in Quebec, and was in part a reaction to the growing political and social involvement of French-speaking minorities and Catholics in general across the northeastern borderlands of Maine and New Brunswick. These minority groups challenged the Protestant, anglophone status quo and prompted the emergence of a transnational “Patriotic-Protestantism” that rejected Catholic participation in the political sphere and bilingualism in schools while promoting traditional national values and a focus on Protestant morality.1 Tapping into this ideology, the Ku Klux Klan in New Brunswick represented a bridge between the American Klan’s conspiratorial anti-Catholicism and the deeply rooted Anglo-Irish anti-Catholicism of the Orange Order. It did so both ideologically and directly, as the organization had connections with the Orange Order and the Conservative Party of New Brunswick as well as cross-border links with the Maine Ku Klux Klan. Although the organization never grew to the size of its neighbour in Maine, nor did it establish the lasting roots of the provincial Orange Order, the New Brunswick Ku Klux Klan represented the transnational nature of the social disquiet that spread throughout Protestant communities in the Northeast during the early 20th century.

2 The arrival of the Ku Klux Klan in Canada was first reported in 1922, broadly coinciding with the expansion of the organization north of its traditional southern stronghold.2 The Canadian Klan had a presence across the dominion, with a strong influence in the Prairie provinces. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these provinces had experienced steady settlement by Protestants, including many members of the Orange Order, and large numbers of eastern and southern Europeans whose religious and cultural institutions differed from that of their Protestant neighbours. In addition, francophone Catholics, including descendants of migrants from Quebec and the Métis (descendants of French fur trappers and First Nations women), presented a challenge to anglophone cultural hegemony.3 As sites of ethnic diversity, these provinces were also sites of xenophobia, anti-Catholicism, and general patterns of nativism as anglophone Protestant communities, often organized around Orange lodges, sought to maintain their supremacy over francophone settlers, the Métis community, and waves of different immigrants from Europe and Asia.4 The Klan even operated in Quebec and threatened Catholic and Jewish homes and businesses, although the organization could not fully establish itself in such a Catholic-dominated province. The Canadian Klan found particular success in Western Canada, the site of major immigration from Asia, Eastern Europe, and Southern Europe. In Alberta, “anti-immigrant sentiments among the local population were inflamed; church leaders, the press and the Orange lodges in the prairies warned of the threats to Canada’s supposed British heritage.” In Saskatchewan, the Klan worked closely with the local Conservative Party. This intimacy involved future Prime Minister R.B. Bennett, who “sat on the board of the [Regina Daily] Star, which became a mouthpiece for anti-French Toryism and one of the most openly favorable press allies of the Klan.”5

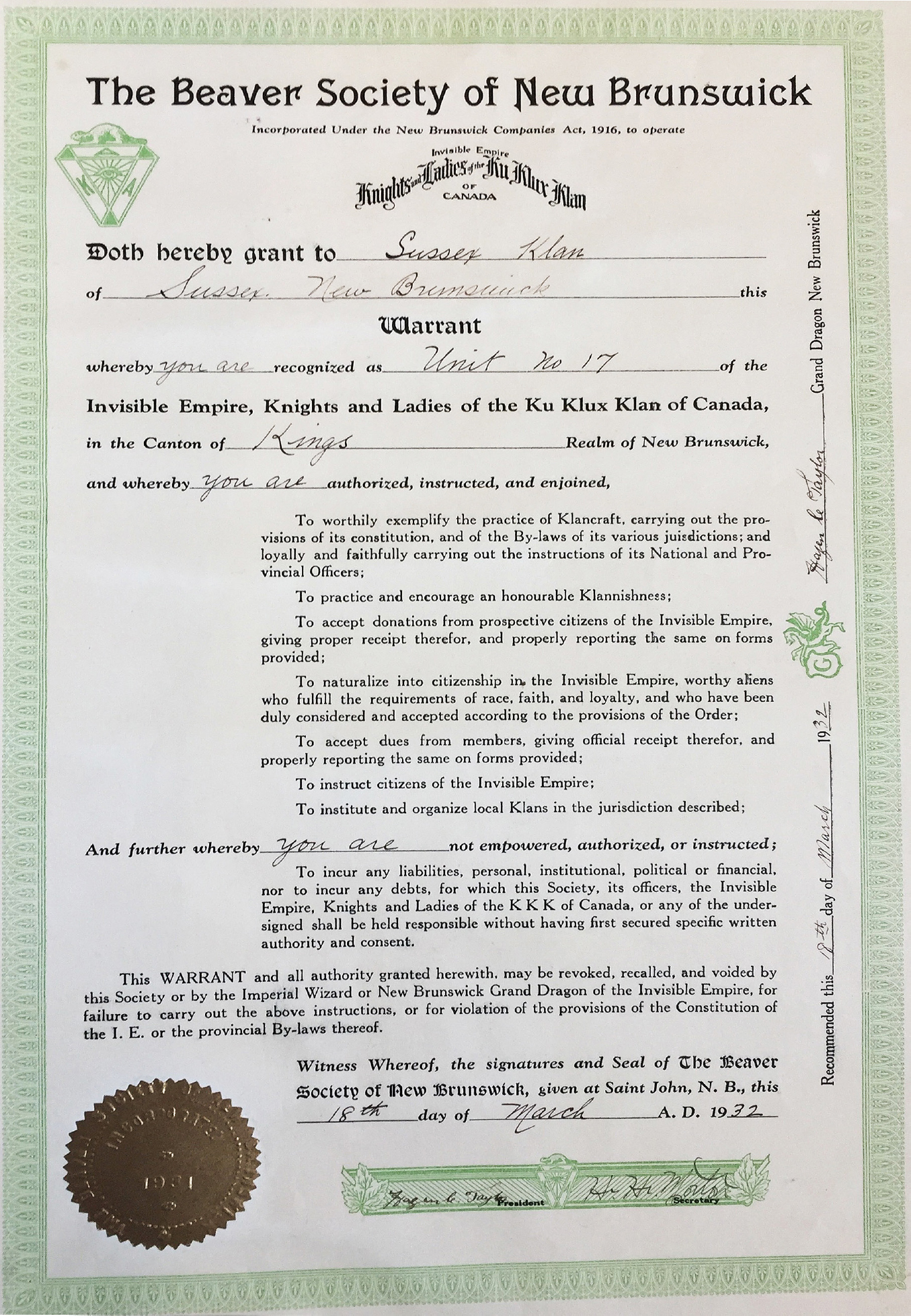

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

3 “Patriotic-Protestantism” and the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan in New Brunswick and the rest of Canada also coincided with the rise of other right-wing movements across the country. During the calamitous Great Depression, many who were dispossessed by the collapsing economy were “drawn to the Fascist cause, an attraction reinforced by a willingness to blame certain ethnic or racial minorities for the people’s woes.” Jews were a major target of fascist attacks, as was the case in Europe, due in part to “the heightened social tensions wrought by economic crisis, and the widely broadcast histrionics of Adolf Hitler, which reinforced the image of Jews as permissible targets, [that] provided an opportunity, in the early depression years, for provocation and street action.” French-speaking Canada also faced the emergence of right-wing hate movements, as Quebec saw the rise of explicitly styled fascism led by Adrien Arcand. His fascist and nationalist parties and press organizations promoted the fear that “the twin processes of industrialization and urbanization had created large and telling strains on the province’s social and economic structures.” Arcand and others saw the need for “a national savior, a great leader at the helm of the right sort of party” – one who saw “the Jews, and the ‘Jewish problem,’ as the key to the mystery of the enslavement of not only his own noble and suffering people, but the world.”6

4 The Ku Klux Klan in New Brunswick was formed in this environment of discontent and conspiratorial fear. The rise of a politically active and socially vibrant Acadian community in the early 20th century fanned the fears of nativists in the province. The Acadian population in New Brunswick, which numbered nearly 137,000 in 1931, had long been ignored and denigrated by the anglophone population and had traditionally been economically marginalized from the rest of New Brunswick. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries the community was increasingly drawn into the province’s pulp industry.7 At the same time Acadians’ customary hunting and fishing rights were restricted by the provincial government, who hoped to build a tourism industry geared towards sport hunting and fishing. Coupled with a lack of available land for settlement, “French New Brunswickers were among the most affected by these corporate intrusions and privileges . . . [as] their communities on the fringes of the pulp company’s vast cutting empires were providing much of the cheap labour demanded by this new economy.” With “francophones rapidly reaching numerical supremacy in the northern counties,” it was increasingly clear for anglophones in the early 20th century that dealing with the Acadian community was unavoidable.8

5 The francophone Acadians had long been under the heel of the dominant Protestant anglophone population. After the expulsion of most of the Acadian population beginning in 1755, Acadians and other Catholics in what would become New Brunswick were deprived of their political rights as members of the British Empire while decisions about francophone language and education rights were typically made to benefit anglophone Protestant supremacy in the province. It was not until the mid-19th century that an “Acadian Renaissance,” built upon the development of Acadian educational and religious institutions, began to take shape. Even by 1870, “there were only two Acadian professionals: one lawyer, P.-A. Landry, and one doctor, Alexandre-Pierre Landry.”9 The development of an Acadian middle class in the years following Confederation, coupled with the growing engagement of the population in the economic life of the province, allowed Acadians to become a vital part of New Brunswick’s political sphere.

6 While the francophone Acadians were an increasingly prominent and highly visible minority group in the province, Irish Catholics had long served as a target for nativist attacks in New Brunswick and would continue to be targeted by groups such as the Klan during the 20th century. Irish immigrants fleeing the horrors of the Potato Famine began arriving in the province in large numbers during the mid-19th century. This was a shock to the anglophone Protestant population, one that elicited a powerful nativist reaction. The provincial Orange Order helped lead this reaction. As I have elsewhere pointed out, “the Orange Order had established itself as a respectable organization in Protestant Canadian society,” a fraternal order that was foundational to Protestant communities across Canada. Despite this respectability, “it virulently attacked Catholic and francophone rights and privileges in society.” Orangemen portrayed themselves as extralegal protectors of ancient British liberty and culture, reflective of the British loyalism of the colony.10 To this end, Orangemen and Irish immigrants routinely and violently clashed throughout the mid-19th century, often on religious or ethnic holidays packed with symbolic meaning.11 Adding to the ethnic tensions in the province, Irish Catholics also competed with the francophone Acadians for control of the local Catholic Church and the language of church services and education in particular.12 The ethnic and religious tensions between Protestants, Irish Catholics, and Acadians remained a prominent part of New Brunswick’s social fabric as the 19th century gave way to the 20th.

7 In light of the economic and demographic swings occurring in the province, the political scene in New Brunswick began to shift during the First World War. Nativist groups such as the Orange Order called Catholic loyalty into question, pointing to the Irish Easter Rising in 1916 and Québécois nationalists who “questioned the rationale for fighting in a European war under the direction of Britain.”13 Though many Irish Catholic Canadians “made the case for Catholic loyalty and sacrifice during the war, they had been made guilty by association because their francophone and immigrant co-religionists were considered inherently ‘disloyal’.”14 In much the same way that conscription served to divide English and French in the central Canadian provinces, the lack of Acadian support for the war effort became an issue of social and political import.

8 The “sagging recruiting campaign among New Brunswick’s French-speaking citizens” caused major alarm among supporters of the war effort. Even more alarming was the francophone community’s support for Wilfrid Laurier and the Liberal Party’s “anti-conscription stand,” which galvanized Acadian voters and built a long-standing relationship between the Liberal Party and francophones in New Brunswick.15 To conservative Protestant anglophones who saw an alliance between their political and ethnic rivals, “it seemed that the Liberal Party was the Acadian party, and it was ‘they’ who were going to govern New Brunswick. . . . It was a terrifying prospect – a diabolical plot.” At a time when issues such as the funding of sectarian schools dominated the political sphere and “cultural and religious loyalties [were] always lurking beneath the surface of voting patterns,” the emergence of an explicitly Protestant political agenda, built upon fears of growing Catholic influence, was predictable.16

9 The New Brunswick Ku Klux Klan was well-suited to exploit this conspiratorial moment among the Protestant population.17 In much the same way as other nativists in Canada and in the United States, klansmen in New Brunswick were quick to look for conspiracies among francophones and other Catholics and the politicians reliant on their vote. The Klan saw these conspiracies as rooted in a moral corruption brought on by the growing presence of Catholics and French-speaking Acadians in the social and political fabric of the province; they thus sought to act as a bulwark that maintained the traditions of the white, Protestant, and conservative society that had dominated New Brunswick for more than a century. The Klan was ready to act as both an extralegal force meant to intimidate others into submission and, if the need arose, to act as a military force intent on destroying the enemies of “White, Gentile, Protestant civilization.”18 It did not operate in a vacuum, as it looked across the border to the influential and politically powerful Maine Ku Klux Klan as both a source of ideological and material support. Within New Brunswick, the Klan worked with the more respectable forces of conservatism, the Orange Order and the provincial Conservative Party, to pursue its ambitious aims.

10 The Ku Klux Klan in New Brunswick was constantly on the lookout for Catholic conspiratorial behavior. In a letter circulated by G.E. Davies, chairman of the Debec Junction Klavern’s Legislative Committee and king kleagle of the New Brunswick Klan, Davies proclaimed that “the Roman Church, thru its high representatives in various parts of Canada are conducting a schismatic campaign against the rights of every freeman, including those of its denomination” by expressing its opposition to the 1930 Divorce Act in Ontario.19 Working “thru members of International Labor Unions,” another source of conspiratorial rhetoric from the Klan, “these authorities” had supposedly issued “instructions to vote against” the pending law and threatened the public schools through a demand for the “repayment of Public school taxes.” These conspiracies reflected a constellation of issues that struck fear into the heart of Protestant New Brunswick. Klansmen also feared the Catholic Church’s influence over the press. They supported the Protestant-leaning Carleton Sentinel, which Davies claimed had written glowing stories about the Klan’s actions and against “the Catholic Priest at Debec”; this priest had “visited the Office of the Sentinel, demanding an undertaking from the editor that the publishing of news items pertaining to the Klan movement be stopped, making a viscious [sic] attack on its officers, and [threatening] the stoppage of all Catholic subscriptions.”20 The image of a unified and controllable bloc of Catholic readers led by nefarious Catholic priests was shared by both the Maine and New Brunswick Klan organizations and represented one of many conspiratorial tropes both nativist groups utilized.

11 The Ku Klux Klan of Kanada drew upon a deep well of conspiracy, as evidenced by C. Lewis Fowler’s pamphlet, The Ku Klux Klan, which served as both an ideological document for the Klan movement in Canada and as a repository for conspiracy theories and Fowler’s dramatic ideas about the Klan’s place in modern society.21 Fowler’s uncorroborated interpretations of papal circulars presented the church’s “condemnation . . . toward our government and educational system” as part of the global conspiracy to convert Protestants throughout the United States and Canada. Fowler attacked Catholic schooling, claiming that “Rome has actually invaded our schools through her pernicious textbook system” and that this endangered Protestant education by removing the Bible from schools while substituting it with Catholic propaganda. Fowler connected the Catholic priesthood with “ancient Roman paganism . . . [as] a product of orientalism, having been transplanted in Rome from the East.”22 Through this line of argumentation, Fowler stripped the Catholic Church of its white, Western status, giving the Klan the right to oppose the Church as part of its program of white supremacy.23 Fowler painted the Ku Klux Klan as a valiant force, rooted in ancient Scottish rites and descended from the hearty Nordic races that were destined to defeat the conspiracies arrayed against it and preserve a traditional Protestant society.

12 Inflamed by a web of conspiracies, the Klan in New Brunswick saw itself as a bulwark against social and moral decay. The Klan celebrated its agenda of halting the moral decay of modern society and perhaps even of reversing the profound changes klansmen saw cropping up around them. Ending the influence of Catholicism and liberalism was part of this, as they viewed New Brunswick society as fundamentally conservative and rooted in the traditions of British Protestantism. This nostalgic longing for an idealized past in which a traditional, conservative home life dominates is foundational to conservative thought. As political scientist Corey Robin points out: “Behind the riot in the street or debate in Parliament is the maid talking back to her mistress, the worker disobeying her boss. That is why our political arguments . . . can be so explosive: they touch upon the most personal relations of power.”24 The Klan and its fellow nativist organization, the Orange Order, understood intimately that political interests extended far beyond the halls of power, and they shared an impulse to involve themselves in conflicts over education and personal responsibility as a means of pursuing their agenda.

13 As an organization dedicated to the preservation of a Protestant British identity in Canada, the Klan in New Brunswick placed a great deal of interest in the display of the flag and the maintenance of a traditional, Protestant identity. The 1920s and 1930s were transitional decades for the shaping of Canadian identity, as Canada’s evolution towards independence continued and ideas of continentalism, which saw Canada’s future as deeply intertwined with the United States and the western hemisphere as opposed to with its imperial brethren, became even more prominent. The declining fortunes of the British Empire after the First World War, its military disengagement from North America, and growing Canadian autonomy on the international stage all led Canadians to reconsider the utility of their ancestral devotion to the British and motivated “Canadians to develop a strong, shared sense of national identity – one new and distinctive, not simply a local version of British identity.”25 The Klan and the Orange Order participated in the debates over Canadian identity, coming down hard on the side of renewed Britishness and the promotion of traditional Anglo-Canadian values.

14 The Klan sought to preserve the traditional nationalistic imagery of British North America. One klansman named Roy Stableford wrote to King Kleagle Davies to bring up his concern that “very little respect is being showed to ‘Our Flag’ these days, and it is not being displayed in our schools” in Sussex.26 The Klan in New Brunswick saw the school system as a primary locus for patriotic indoctrination and battlefield against Catholicism and the French language. A few months after Stableford first expressed his anxiety about the flag to Davies, the Sussex Unit of the New Brunswick Klan passed a resolution decrying “that very few of our schools in New Brunswick are living up to the school law regarding the flying of the flag.” This served as a clarion call for klansmen in the province to “put forth every effort in our own community and all over our Province, to see that our flag is placed on every school in the Province,” as well as to ensure “that every teacher be instructed to give flag drill every week.”27 To this end, the Sussex Klan “appointed a School Committee who are working at present on getting a list of: all schools in Kings Co., the names of their trustees and their denominations; The School Teachers’ names and their denominations; What schools are flying the Flag and the ones that are not.” They also sought to make the Klan an example of proper patriotism by “[resolving] that each member of this Klan have a flag placed in a prominent place in his home,”28 thereby strongly connecting proper behavior in the public sphere with the private. The Klan’s self-appointed role as enforcers of patriotic conduct in schools and public life was deeply linked to the changes occurring around them.

15 The Klan associated this supposed decline in patriotism to the moral failings of Canadian society. In Stableford’s first letter to Davies, he declared that the Klan “will also bring back the Bible and the Family Altar into the Canadian home once more, just as it was in the days gone by.” Returning the Bible to the household, central to the Protestant tenet of Sola scriptura, challenged what Klan supporters saw as the Catholic Church’s unwillingness to allow its adherents to understand the Bible itself. Klansmen and other Protestant advocates feared the threat of “mental incarceration . . . inevitable to all who live within the bounds of the papal system,” and so hoped to defend what they saw as the province’s traditional Protestant orientation.29

16 As a Protestant organization fighting for proper morality in New Brunswick, the Klan also presented itself as a force for temperance in the province. Even before the advent of Prohibition in the United States, New Brunswick had long been a source of contraband flowing into Maine, as “nearly all of [the New Brunswick-Maine border] was unguarded woods where people came and went according to their pleasure and custom.” As such, smugglers “did not have to invent a wholly new art – they merely revived and refined the old.”30 Protestant groups such as the Ku Klux Klan often linked Catholics with violations of the liquor laws and general moral degeneracy.31 Issues such as alcoholism and prostitution have long been a source of social contradiction. Cheryl Krasnick Warsh points out that “the concept of ambivalence, as defined by the social anthropologists, was created to describe conflicting attitudes towards alcohol consumption, which were the legacy of the anti-liquor movement.” Warsh further states that “the negative aspects of drinking as a state of cultural remission were behaviours targeted by the temperance crusaders,” among whom the Klan was both prominent and fanatical. The linkage between Catholics and alcohol was often more a result of Protestant efforts, as “the enthusiastic adoption of coercion as a means to achieve prohibition by the evangelical Protestant churches, and the use of intemperate, anti-Catholic, and xenophobic language by prohibitionists frustrated by the persistent failure of their agenda” turned many Catholics, some of whom supported drinking reforms, away from the temperance movement.32 The Klan raided “houses, suspected of being disorderly, card rooms and illicit liquor joints” – all locales linked with Prohibition and the threat of moral degeneracy.33 Internally, the Klan viewed “excessive or habitual drunkenness” as a major offense against the organization, one that could result in banishment and ostracization.34 Attacks on these dens of iniquity, as well as the Klan’s fierce internal management of alcohol, point to its efforts to enforce a moral prerogative in New Brunswick along the lines of its traditional vision of society.

17 The Ku Klux Klan of Kanada, the New Brunswick Klan’s parent organization, explicitly described itself as a chivalric force for the moral betterment of Canadian society. The Provisional Constitution and Laws declared “this Order is an institution of Chivalry, Humanity, Justice, and Patriotism embodying in its genius and principles all that is chivalric in conduct, noble in sentiment, generous in manhood and patriotic in purpose.” To this end, the Klan’s “peculiar objects are: first to protect the weak, the innocent and the defenseless from the indignities, wrongs and outrages of the lawless, the violent and the brutal” – a bold claim coming from an organization most known in both the United States and Canada for pursuing terror campaigns against the weak, the innocent, and the defenseless. Nevertheless, this ideal colored their worldview. The Klan also declared that one of its primary objects was “to shield the sanctity of the home and the chastity of womanhood,” another attempt to revert society to a simpler, more traditional time before the rise of the liberated flapper in a jazz club. To this end, the Klan made “disrespect to virtuous womanhood” yet another major offense that could carry the punishment of banishment from the order.35

18 Further connected to its self-appointed role as a social guardian, an interesting facet of the Ku Klux Klan during its rise in the 1920s and 1930s was its explicit emphasis on militarism. Article XIX, Section 1 of the Provisional Constitution and Laws declares “the government of this order shall ever be militaristic in character, and no legislative or constitutional amendment hereafter shall encroach upon, affect or change this fundamental or principal law of the order.” The constitution also describes the military structure of the Klan organization, assigning ranks and responsibilities to offices such as the king kleagle and organizing the geographic extent of each military command should the necessity arise for the Klan to act for “the betterment of our people, the development of our country and the security of our civilization.”36

19 In perhaps the most disturbing section about military matters, the Klan constitution describes the organization’s belief in the need for rationalistic, scientific studies of the Canadian population to facilitate its agenda to impose its will over the country in case of open military conflict, calling it “the duty of the military organization to make surveys of a social, educational, economic, religious and other conditions in the entire nation, to locate and determine the name, address, nationality, business relationships, political affiliations and activities, religious affiliations and activities and other general characteristics of each and every person in the entire nation.”37 The extreme readiness the Klan hoped to demonstrate in defense of “White, Gentile, Protestant civilization” portrays the movement less as a fraternal organization or nativist movement and more as a fascistic organization that deeply threatened both the rule of law and the monopoly of force held by the Canadian state.

20 The Ku Klux Klan’s emergence in the 1920s and 1930s parallels the rise of fascism in Europe. Both the Klan and the European fascist parties saw themselves as forces meant to reshape the societies they saw around them. In his study on the rise of fascism as an ideological force across Europe, sociologist Michael Mann describes fascism as “the pursuit of a transcendent and cleansing nation-statism through paramilitarism.” Although the question of addressing nationalism in the Klan’s ideology and actions in the northeastern borderlands more fully is beyond the scope of this article, the Klan certainly saw itself as a cleansing force that pursued an exclusive vision of society through paramilitary means. The paramilitarism of the European fascists, which Mann saw as “entwined with [the] other two main fascist power resources . . . electoral struggle and in the undermining of elites,” was certainly familiar to klansmen in both New Brunswick and Maine, who used their organization as a force for the advancement of the Protestant agenda and the curtailing of party politicians’ authority.38

21 Of course, any comparison between the Ku Klux Klan and the fascist movements of Europe requires several caveats. Unlike the modernism and continental philosophy at the heart of fascist theory, the Klan’s ideological foundations were rooted in long-standing North American nativist traditions, with the anti-Catholicism and anti-radicalism of the colonial era comingling with pseudo-scientific racial theories. The Ku Klux Klan did not share fascism’s disgust with democracy or classical liberalism; it instead preferred Anglo-American political and economic traditions, if perhaps restricted to those ethnic and religious groups who the Klan saw as most capable of engaging in civic life. At the same time, the Klan certainly emerged during the same post-war uncertainties that plagued European fascists and shared with them a predilection for militarism, extralegal violence, and sharp divisions between the nation and its external enemies.

22 In 1925 the Telegraph-Journal of Saint John reported that “the K.K.K. had a busy ‘week-end’ in Woodstock,” attacking more “houses, suspected of being disorderly, card rooms and illicit liquor joints.”39 This interest in the rougher side of society reflected the Klan’s self-image as a moral force and its willingness to engage in extralegal activities to demonstrate its worldview. The Klan made its presence known in New Brunswick during the conflict over Prohibition, and the police found that “in their fight against booze use and abuse, the forces of law and order had a powerful ally” that was willing to threaten, cajole, and make use of violence in its crusade against immorality and Catholicism.40 Violence and intimidation were means of cowing enemies and exciting allies, but more than that the Ku Klux Klan had tied these extralegal means of coercion, not so different than the random outbursts of hatred and violence endemic to human history, to a socio-political organization with an explicit vision for society. For the Klan as well as for fascists, “paramilitarism was violence, but it was always a great deal more than violence.”41

23 The Klan’s crusade for a social rebirth certainly involved threats and intimidation aimed at the weak. In 1928, the Daily Gleaner reported that two women were terrorized “by vested and hooded marauders, who lighted a fiery cross.” Though the article never explicitly identifies the men as klansmen, it claims that “a letter thrust under the door of the house contained insulting remarks and stated that the man [the husband of one of the women] and his wife were ‘marked by the Invisible Empire’”– a clear reference to the Ku Klux Klan. It is unclear why the women were targeted, but the article declared that “the persons threatened are highly respectable.”42 Whatever the root cause of the demonstration, the incident showed the New Brunswick Klan’s willingness to use terror against their enemies. W.W. Thorpe and Charles Enman, in their article on the Klan movement in New Brunswick, further report that the Klan attempted to intimidate a lawyer defending an alleged murderer, which the Klan saw as an affront to justice.43 The Klan’s menacing behavior may have even included murder. Edward E. Armstrong, a farmer in Perth, New Brunswick, received a threatening letter from the Klan in 1927. The next year, “he was found dead in a barn near his home. It was murder. Whether the Klan did it was never shown. But to threaten violence is itself a type of violence.”44

24 In its pursuit of a new society, the New Brunswick Ku Klux Klan cultivated connections with other Protestant organizations, both inside and outside of the province. The founders of the Canadian Ku Klux Klan were Americans; Canadian nativists disparaged them as con men “whose only interest in the movement was a monetary one,” a common criticism of Klan organizers in both Canada and the United States.45 Early accounts of Klan activity in the province described the presence of Americans, such as a report of a cross burning that claimed that “the cross . . . was ignited by two men who arrived in an automobile which bore a New York license.”46 Although the Canadian Klan had “decided to get rid of all those not 100 per cent British,” the organization still cultivated connections across the border.47 In 1927, “by special invitation. . . [for] a special occasion,” the Houlton Ku Klux Klan Klavern in Maine invited their Canadian counterparts to “attend Church and Parade” in Littleton, Maine – a town north of Houlton near the Canadian border.48 Transnational events like this one, facilitated by a porous border, presented the international face of the Ku Klux Klan and the forces of nativism in the Northeast.49

25 In addition to the Canadian participation in Klan events in Maine, Americans were a common sight at Klan events in New Brunswick, signalling both the proximity and sympathy that existed in the northeastern borderlands. Highlighting this overlap, the Sussex and Saint John klaverns sent a request to King Kleagle Davies to “procure the ablest speaker from the State of Maine” for a Klan ceremony near Sussex.50 The Klan in Maine presented a powerful example of the strength the organization could exert over society and politics. The Maine Klan boasted at least 40,000 members at its peak and played a key role in state and local elections throughout the 1920s, including the election of a rumored klansman as governor in 1924.51 With its size and influence, it served as an ideological and material bulwark for the growing organization in New Brunswick. More than simply inviting speakers “from away,” New Brunswick klansmen also encouraged the participation of their American counterparts in local events, boosting the number of klansmen at events during the early years in the province and augmenting the spectacle at the heart of the Klan’s imagery.52 At the first open-air “naturalization ceremony” held by the Klan in New Brunswick, the Daily Gleaner reported the presence of “approximately two hundred robed and hooded Knights from all sections of the province and the State of Maine,” revealing an interesting internationalism for a pair of nativist, intensely nationalistic organizations.53

26 The Ku Klux Klan in New Brunswick also cultivated connections with the local Orange Order lodges, an obvious fit for Protestant, virulently anti-Catholic, and nationalistic organizations. The Orange Order was firmly established in the province with 169 lodges, and “[the Klan and Orange Order’s] strength tended to be concentrated in the same areas, namely Carleton, York, Kings, Saint John and Albert counties.” Moreover, “the Orange Order and the Ku Klux Klan were not only in sympathy with each other, but likely shared membership.54 Prejudice served as a bonding factor between the two,” providing a foundation for the growing Ku Klux Klan in New Brunswick. Klan speakers at a naturalization event praised the Orange Order, calling it “the backbone of Protestantism” and claiming that “the K.K.K. stood beside it.” The two groups were united by their resistance to Catholicism, leading one speaker to declare that “Protestantism was not purely a religious term, but ‘because every time someone tries to impose on us we protest against them’.” This dynamic intrinsically linked the Klan and the Orange Order’s opposition to Catholic influence with the efforts of men such as Martin Luther and the Reformation more generally.55 The Klan even supported the benevolent causes of the Orange Order, such as the New Brunswick Protestant Orphanage Home. One Klan leader declared that the orphanage was “a cause deserving of the support of all Klansmen and Klanswomen,” leading him to propose the Klan raise money for “this Protestant Institution.”56 This orphanage and others like it were a long-standing concern for Orangemen, who believed that the placement of Protestant children into Roman Catholic institutions was akin to a betrayal of faith.57

27 The interaction between the two organizations, and the key linkages cultivated among members, extended into the political sphere as well. Despite, or perhaps because of, the Klan’s constant vigilance for conspiracy among their enemies, it was they themselves who often engaged in secretive and apparently quid pro quo arrangements with local politicians. A key figure in the activities of the Canadian Ku Klux Klan nationwide was Imperial Kligrapp (or Supreme Secretary) James S. Lord. In addition to this post, Lord was also a Conservative member of the Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick from 1925 to 1930 – a period when the Conservative Party was deeply engaged in maintaining anglophone supremacy in the face of the Liberal Party’s growing affiliation with French speakers both inside and outside of New Brunswick.58 Lord took a keen interest in the Klan’s activities and growth in his home province, promoting the cause and attending to many administrative issues faced by the klaverns in the province. Another key connection between the political world of New Brunswick and the Ku Klux Klan was Harry H. Morton, who served as a kleagle in the province. Morton also held a position in the Department of Public Works. During the election of 1935 this connection worked to the political advantage of the Liberal Party, which was increasingly competitive with the long-dominant Conservatives due to its growing connection with the Acadians.59 Morton’s importance to the Klan in New Brunswick went well beyond his authorship of political tracts or his nativist civil service; he cultivated a relationship with one of the most prominent politicians in New Brunswick during the early part of the 20th century – Richard Burpee Hanson.

28 Hanson was a prominent figure within the Conservative Party of New Brunswick, who served as a Member of Parliament among other political posts.60 A member of the Orange Order, he also acted as a key linkage between the New Brunswick Ku Klux Klan and the more respectable forces of conservatism in the province. His correspondence with Harry Morton ranged from political favors for the New Brunswick Ku Klux Klan, both for the organization as well as for individual Klan members, to his sympathetic positions on contentious political issues in the province.

29 Morton often turned to Hanson for help with legal or administrative issues faced by the growing Klan movement in the province. In one such situation, while serving as a member of Parliament, Hanson helped Morton pursue a copyright on the Klan’s moniker and rituals in New Brunswick, a key issue as factions and competing organizations arose within the Klan and threatened to break apart the movement. Hanson referred to the Ku Klux Klan as a “highly important order in New Brunswick” and claimed that he was “acting for the legitimate branch” in the legal dispute over the copyright. Hanson also stressed the mutually beneficial relationship between himself, the Conservative Party of New Brunswick, and the Ku Klux Klan. He called Klan members “the very best supporters we have” and claimed that “I want to do whatever I can for them,” which highlights the important connection between the nativist organization and the political realm of early-20th-century New Brunswick.61

30 Hanson also highlighted his ideological connections with the Ku Klux Klan. In the same letter dealing with the copyright issue he expressed his unwillingness to deal with the Copyright Office, stating “I do not like to write direct to the Commissioner as he is probably of the Roman Catholic faith, and it might leak.”62 The secretive nature of the Klan’s anti-Catholic activities was clearly amenable to sympathetic politicians. In a letter to Morton the following year, Hanson again expressed his reticence to deal with a “French Canadian Roman Catholic” with whom he was “sure I could get nowhere with . . . without being right on the spot.”63 Exchanges such as these reinforce the obvious parallels between the Klan’s positions and those of mainstream Conservatives in the province.

31 Hanson and Morton also conferred on issues of nationalism and national imagery. The issue of “foreign” flags being flown in the province, particularly by Acadians, was an important one to the Klan as it inflamed their sense of national aggrievement and provided them with kindling for their nativist attacks on the Acadian population. Morton claimed that he “had a number of enquiries from various Units regarding the law in regard to the flying of the flag.” He further claimed that “there are many communities that fly only the French Flag on public buildings and personal properties,” which challenged his understanding “that it is not proper to fly any foreign flag in the Dominion unless the British Flag was flown higher on the same pole.”64

32 Hanson’s response maintained that while “so far as I am aware there is no law on the subject” of flying foreign flags, it was his belief that “it is a matter of principle, however, that wherever a foreign flag is flown the Union Jack should appear above it.” Additionally, supporting Morton’s interest in the Acadians’ use of a separate flag, Hanson claimed that “it is not proper to fly any foreign flag on any public building in Canada.”65 In a subsequent letter Hanson further emphasized – after consulting with the under secretary of state in Ottawa – that the issue of the flag “is one of the matters, such as the playing of the National Anthem, which is governed by traditional custom,” appealing to the conservative, tradition-centred mindset of the Klan and other nativist movements.66

33 The Klan’s close connection to New Brunswick politicians at both the provincial and national levels paralleled its involvement in New Brunswick elections. The Ku Klux Klan certainly animated a certain segment of the populace that saw the francophone and Catholic populations as intimately connected with anti-British and anti-Canadian sentiments. This belief was driven by figures such as Liberal Premier Peter J. Veniot, who opposed conscription during the First World War as well as the temperance movement, both of which were special interests of the Ku Klux Klan and other nativist forces in the province. Veniot, a Liberal, Acadian, and Catholic, saw his subsequent defeat in the 1925 provincial election as a conspiracy and “claimed in the legislature that among the forces that had conspired against him were the Orange Order and the Ku Klux Klan.” Although many shrugged this off and “attributed his defeat to other factors than the ‘race and religion’ cry,” later reports “claimed knowledge of ‘Yankee interlopers’ who had worked against Veniot in prominent Protestant counties in New Brunswick.”67 The American presence in the New Brunswick Klan and the experience of Maine klansmen in electoral politics lends credence to Veniot’s accusations, as would its rumored involvement in subsequent provincial elections.

34 Firmly established in the province by the late 1920s, the Klan also made its presence felt in the 1935 election, a contest between Conservative L.P.D. Tilley and his Liberal opponent Allison Dysart. Dysart, a Catholic, was the target of an attack by the Ku Klux Klan in a broadside. Labelled “Strictly Private and Confidential,” Circular No. 888 declared that “we are on the eve of an Election, and one Party is headed by a Roman Catholic and whose followers are most [sic] Romans.” The circular claimed that “an effort has been made in the press and from the platform to have the public believe that Allison Dysart is English and Scotch in an endeavor to cover up his actual religion.” It also linked Dysart to francophone politicians such as Clovis Richard and Andre Doucet. Continuing to harp on the threat of a Catholic leader, the Klan circular asked: “How can we protect the Constitutional Rights of Canada and keep it free from Foreign domination if we support a Roman Catholic leader, dominated by Rome?” Such strident language clearly echoed the longstanding trope of a Catholic conspiracy orchestrated by the pope and maintained through compliant politicians. Calling upon klansmen across the province to act yet again as a bulwark against the enemies of Protestantism, the circular concluded by stating “It is therefore the duty of every Klansman, not only to vote and support the Protestant Government, but each, and every one, should work unceasingly to see that Dysart and the other Romans are defeated. New Brunswick must be kept Protestant.”68

35 Both sides reacted sharply to this “leaked circular.” John McNair, a Liberal candidate in York County, attacked the circular and claimed it demonstrated “the Klan was interfering in the election . . . [by engaging in] a religious canvass against Opposition leader Dysart.” The Conservative Party refuted those claims, responding that “the Liberals themselves had introduced the circular into the campaign to tar their opponents with the stigma of dirty tactics.” McNair’s response to this accusation was to identify the author of the supposed circular as “a Conservative and an employee of the government” – Harry H. Morton. McNair’s attacks seem to have benefitted the Liberals, as they swept to a clear victory in 1935, winning forty-three seats to the Conservatives’ five.69 Though the effects of the Great Depression played a role in sweeping away the Conservative Party, as Prime Minister Bennett’s entire five-year tenure “was overlain by the dark cloud of the Depression,” it appears that the tide of anti-Catholicism as a political factor had ebbed as well, just as it had done in Maine during the late 1920s.70 It is clear, however, that the Ku Klux Klan in New Brunswick had an impact on the politics of the province, forcing politicians, both supporters and opponents, to reckon with the forces of nativism and ethno-nationalism.

36 The Ku Klux Klan in New Brunswick presents a curious case of the challenges of identity. In many ways, it was an extension of the phenomenon of nativism and anti-Catholicism that had swept the United States in the years after the First World War. Its opponents in Canada certainly viewed the Klan as “Yankee interlopers,” troublemakers who sowed discord and interfered in the internal politics of provinces such as New Brunswick. At the same time, however, the Klan’s connections with local Protestant organizations such as the Orange Order and sympathetic politicians, as well as New Brunswick’s long history of anti-Catholicism and opposition to Acadian integration into provincial society, indicate that nativism was not a foreign force in the region. The easy acceptance of an American organization among a “foreign population” and its powerful resonance with many elements of New Brunswick society suggest that the national distinctions between Americans and Canadians in the Northeast could be overlooked, while the unifying forces of the Protestant religion and Anglo-Saxon heritage served as a means of connecting state and province to a borderlands framework. The Klan’s peculiar nature in New Brunswick points to an understanding of identity and patriotism distinct from the national themes that typically dominate discussions of these ideas.

37 Indeed, as Scott See argues with regards to a spike in nativism in the mid-19th century, “historians frequently use modern boundaries to restrict and define their studies. . . . In the circumstance of numerous clashes between Protestants and Irish Catholics in the Western world of the nineteenth century . . ., it makes little sense to restrict historical studies to hidebound national constructs.” Indeed, for nativists in both the 19th and 20th centuries issues of religion, race, and identity “were guided by an intricate combination of factors: local and foreign, immediate and distant.”71 The Klan itself understood this dynamic, indicated both by its cross-border interactions and by its own pronouncements; as the Klan constitution – adopted by both American and Canadian klaverns – boldly declared: “The phrase ‘Invisible Empire’ in one sense denotes the universal geographical reach of this Order and it shall embrace the whole world.”72 The desire for a global “empire,” one that encompassed all Anglo-Saxon communities, suggests that nationalism was never the essential aspect to the Klan’s ideology. Instead, ethnic identity and a shared religion were crucial to the Klan’s vision of a purified, Anglo-American utopia. By presenting the Klan as a transnational force, as they themselves perceived themselves to be, we can better understand their efforts to reshape the world around them.