Articles

The Invisible Island:

Immigration, Environment, and a New Europe on Big Island, Nova Scotia

Cet article examine l’immigration écossaise en Nouvelle-Écosse dans une perspective environnementale. Big Island, qui est absente depuis longtemps des annales historiques, est un microcosme qui illustre la thèse d’Alfred Crosby au sujet de la nouvelle Europe. La théorie fondatrice de l’historien de l’environnement n’a jamais été appliquée à l’histoire de l’immigration écossaise, au Canada ou ailleurs, et son application à Big Island révèle une forte enclave culturelle et géographique qui témoigne de la puissance durable du lieu.

This article examines Scottish immigration to Nova Scotia from an environmental perspective. Big Island, which has been long absent from the historical record, is a microcosm of Alfred Crosby’s New Europe thesis. The environmental historian’s seminal theory has never been applied to the Scottish immigration story, in Canada or abroad, and applying it to Big Island reveals a strong cultural and geographic enclave that serves as a testament to the enduring power of place.

1 BIG ISLAND, LOCATED ON THE NORTH SHORE of Nova Scotia in the Northumberland Strait, sometimes feels like a place outside of time. The island shares with other island communities that dot the shores of Nova Scotia a fierce sense of self-identity based on the shared historical and cultural experience that is nevertheless unique to particular island communities: the community of Tancook Island, for example, is different from that of Pictou Island, and Big Island is different from the other two. Yet residents of each share the experience of island life.1

2 Too often, places like Big Island are almost invisible in the historical record; we know very little about life on the island before 1830. There never was a church on the island, nor are there parish records from the period prior to 1830 in mainland Merigomish across the harbour.2 Census records are equally difficult, as early regional records usually concentrated on settlement around Pictou.3 Once the census process became more established in the mid-18th century, Big Island did not have its own dedicated sub-region unlike nearby Pictou Island; instead, its population was combined with Merigomish, Egerton, or surrounding communities.4 Early census data is not sufficiently granular to determine the island’s exact population and demographics. Big Island teaches an important lesson about the role of environmental history in historical enquiry because, in the absence of records, environmental history can act as text.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

3 This article is an attempt to examine the environmental dimensions of Scottish settlement on Big Island. Big Island’s history has not been well examined thus far; aside from a few scattered entries in place-name encyclopaedias or local histories, it simply does not exist as a focus of historical scholarship. No comprehensive, published study of Big Island exists. While the history of Big Island is not generally known outside of the community, it is a cultural touchstone within it. By employing an environmental history approach, which focuses on the relationship between human populations and their physical environments, it is possible to add Big Island to the broader history of Nova Scotia.

4 Immigration history and environmental history often intersect, but not within the framework of Scottish out-migration to Nova Scotia. Works by J. David Wood and Neil Forkey, however, provide excellent methodology for examining the complex interrelationship between nature and settlers in the Canadian context.5 Wood, in his study of Ontario, examines geographic patterns of demographics and development, seeing place as a “historical where” and landscape as “society’s recreation” for new immigrants.6 Forkey, for his part, examines Upper Canada through the lens of bioregional history, reflecting on settlers’ “search and adaption to a home place.”7 Yet Scottish out-migration to Nova Scotia is very rarely, if ever, placed within the larger context provided by environmental history analysis. Scotland is not mentioned, for instance, in Alfred Crosby’s Ecological Imperialism.8 This is curious, because his concept of Neo-Europes fits the Scottish emigration experience at least as well as the better-known British, French, and Spanish experiences. Although Crosby only mentions Nova Scotia in relation to Port Royal and never mentions Scotland, his examples of Jamestown, Port Royal, and Sydney in Australia share a similar colonial experience with New Glasgow, Halifax, and Sydney, Cape Breton.

5 Crosby’s framework is useful, but this article will qualify it by emphasizing the settlers’ intention and agency more strongly. In their environmental motivations and inclinations, transplanted Scottish Big Islanders were, and to a certain extent remain, exemplars of Alfred Crosby’s concept of settlement driven by the attractive power of temperate Neo-Europes around the world. Crosby argues that Europeans were drawn to places in the New World, Australia, and New Zealand because these places were similar environmentally and biologically to their old homeland and, once there, they manipulated and tailored their new environments to resemble the world from which they had departed. In other words, they created New Europes across the sea. Crosby also argues that much of this phenomenon was largely accidental – settlers were subconsciously attracted to places environmentally similar to their homeland, and the changes they made to the landscape related more to the introduction of familiar (but invasive) species and practices than deliberate choices.9 Crosby’s thesis emphasizes the unconscious nature of this behaviour, but Scottish immigrants to Nova Scotia knew what they were doing when they both chose and changed the land. They had both intention and agency: they magnified (and celebrated in their culture) those elements of the Nova Scotian environment that reminded them of “home” while minimizing or ignoring those that did not. Even if their decisions were constrained environmentally – the form of their agriculture, for example – there was more to their behaviour than simple serendipity.

6 Scottish immigration is a frequently explored and popular topic in Nova Scotian history,10 but the phenomenon has yet to be explored via an environmental perspective linking people and place.11 Examining the complex historiography of environmental, social, and economic conditions in Scotland itself – Culloden, the unravelling of the clan system, runrig, famine, sheep farming, crofting, kelp production, the Clearances – is outside the scope of this particular study.12 Key works by Bumsted, Devine, Hunter, and Richards help provide background context, especially when they deal with the areas of the Highlands that produced emigrants bound for Big Island, such as Perthshire and the Isle of Mull.13

7 On both sides of the ocean – Scotland and Nova Scotia – the Highland migration is a phenomenon deeply intertwined with a sense of place.14 Island communities can be easily romanticized by outsiders – the seemingly easy pace of life, the connection to a past still apparent in homesteads and barns – but in reality there is a fierce independence and cultural cohesion found in island communities – characteristics that are reinforced by the sense of separation from the mainland.

8 In the case of Big Island, the cultural artefacts created by history – the island’s family names of MacLean, MacGregor, Cameron, and others, for example, together with artefacts created by historical behaviour such as agricultural activity, landholdings, and architecture – reflect a past that is strongly tied to a sense of place, both real and imagined. On the one hand there is a tangible connection to the place that is Big Island, an environment where conditions shaped the form and course of the community that continues to inhabit it; yet there is also a deeply felt connection to a place that is still, for many in the Big Island community, an imagined home: Scotland, from whence their ancestors emigrated during the 18th and 19th centuries. It is therefore possible to examine Big Island within the context of this duality and to begin to understand the role of biogeography in the island’s human history.

9 As a case study, Big Island is an outstanding example of 18th- and 19th century Highland immigration to Nova Scotia. In effect, settlers on Big Island recreated Scotland. Small landholdings, mixed farming, subsistence rather than wealthy living, and persistence of settlement – some residents on the island today still hold their family’s original land parcels – created a familiar landscape out of a foreign one. The island’s enduring culture and cohesiveness captures the essential connection that existed between people and physical landscape and does so down to the present. This study is based on land grants, petitions, poll tax documents, genealogy, artefacts that reflect family histories, local community knowledge of the land, unpublished reminiscences, and diaries15 – all of which demonstrate the foundation of a settler community that is characterized by independence, cultural strength, political engagement, and deep landscape memory.16

10 Big Island, then, can be read historically as a micro-example of one of the broadest historical phenomena of the last half millennium. More than that, the island can serve as a foundation to examine the elements of neo-Europes as practical environments and symbols that inspire such fierce loyalty to place.

11 In the interest of keeping the scope of this case study as focused as possible, it is best to begin on the destination side of the Atlantic. The latter 18th and much of the 19th centuries were characterized by an exodus of tens of thousands of Highland Scots to the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Some of those émigrés settled in Nova Scotia. Records from the period are incomplete – information about the ships that made the trans-Atlantic passages seldom survived, and even more rarely do they include a passenger list – so it is impossible to know the exact number of settlers who sailed to Nova Scotia compared to other destinations.17 Some historians, such as James Lawson, argue that better agricultural land in the United States made British North America an “afterthought” for Scottish immigrants.18 Others, such as David Dobson, contend that the American Revolution caused the immigrant tide to shift from the United States to its northern neighbour after 1783.19 It is safe to say that the region that eventually would become Canada was neither a leading destination nor a complete backwater, but somewhere in between.

12 When compared only to other destinations within British North America, there is no doubt that Nova Scotia was an extremely popular choice. Highlanders’ reasons for choosing to settle in the Maritimes were deeply rooted in environmental and geographical factors. Although Nova Scotia had a familiar name, intended to evoke the landscape and climate of Scotland itself, it was still a foreign land in the 1770s, when Scottish immigration began in earnest.20

13 The catalyst that started to direct the tide of immigration towards Nova Scotia in the late 18th century had everything to do with geographic strategy. After Britain lost the Thirteen Colonies in the American Revolutionary War, it became easier to send Scottish settlers to lands that were still held by the Crown: the region that would later become Canada.21 Scots also generally remained loyal to the British Crown, and preferred to stay within the British colonies.22 This worked well for the British government, which, after the shock of losing the Thirteen Colonies, realized that it was a strategic imperative to colonize the remaining British North American holdings with loyal British subjects.23 Jutting out into the Atlantic and bordering American waters, Nova Scotia in particular acted as a natural “geopolitical buffer zone.”24 British fears seemed to be realized during the War of 1812, when the threat of an American invasion became abundantly clear. Narrowly averting the loss of its remaining North American colonies, Britain realized that a populated landscape could in itself serve as a line of defence against American expansionism and began to directly subsidize emigration in 1815.25

14 Among the first settlers relocated under this new British policy were those from the military regiments that had fought for the Crown in the American Revolutionary War. In 1784, the 82nd and 84th regiments received land grants along rivers, bays, and harbours in what is now Pictou County.26 The Big Island grant awarded to Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Robertson of the 82nd Regiment of Foot, also known as the Hamilton Regiment, was part of this process.27 Robertson’s agent, Robert Stewart, also a member of the same regiment, soon had the island’s 1,500 acres filling up with Scots from Robertson’s kin, clan, and kirk, who were flowing in from the home country (See Figure 2).28

15 The fact that the British government granted Big Island to Robertson, a military man of high rank and later clan chief of the Robertsons, suggests that the island was a highly valued and sought-after section of the county. It could be that the settlement of Big Island was not an administrative afterthought but an important geostrategic element of British policy: Big Island is flanked by Merigomish Harbour on one side and the Gulf of St. Lawrence on the other, which Britain regarded as a key strategic element of its position in eastern North America. It is also important to remember that the men receiving land grants from the Crown in this region were not ordinary settlers but military veterans. By prudently placing trained soldiers in key geographic areas, the British government was in essence attempting to put “boots on the ground” as a deterrent against invasion.

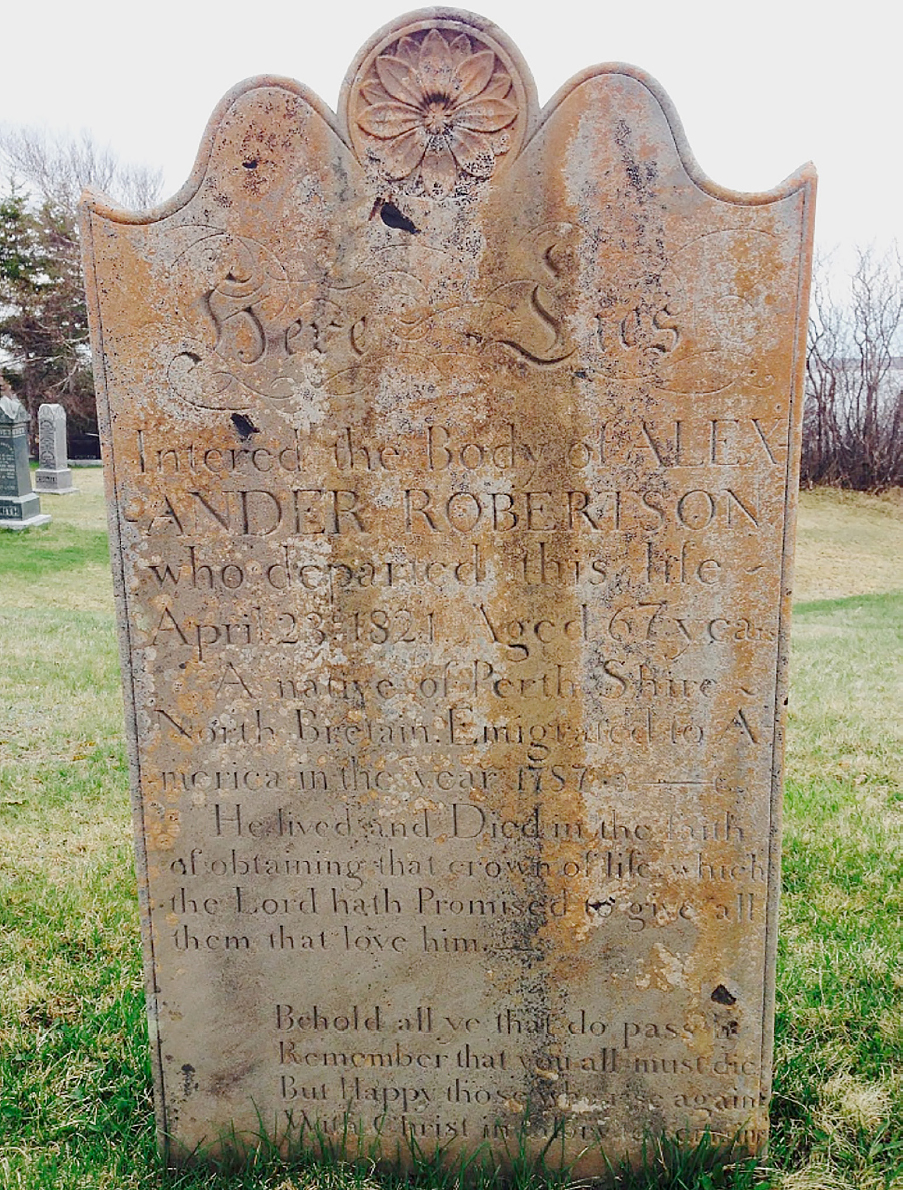

16 Many members of the 82nd and 84th regiments also brought their families to settle in Pictou County. In the case of Big Island, Lt. Col. Robertson remained in Scotland to lead his clan, but had his agent build a house near Smashem’s Head and encouraged his extended family to take up land on the island.29 The first of these was his third cousin, also named Alexander Robertson. The younger Alexander Robertson’s gravestone tells us that he settled on Big Island in 1787 (Figure 3), but not much more is known about him. He may, in fact, have been a military man like his uncle: an unpublished manuscript written by one of his descendants confirms that the only possession of his to survive is his sword.31 Whatever his personal status, Robertson is recognized within the community as the father of Big Island settlement and the first link in the subsequent chain of Scottish migration there.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

17 Once these early settlers had landed, they served as a foundation for further Scottish immigration. Chain migration by families thus became an extremely powerful pull-factor.32 Chain migration is a well-documented phenomenon across all cultures in immigration history, but for Highland Scots it was especially strong. Highland culture had been tightly bound by links encompassing family, clan, village, and their wider geographic environment.33 Between the 1770s and 1850s this loyalty magnified the tide of collective emigration that was already being driven by economic and political conditions in Scotland, effectively transplanting entire families and communities across the ocean. Big Island may be viewed as a representative example of this process. Alexander Robertson’s relatives, of Struan, Perthshire, settled on Big Island in the 1780s. The next generation they were joined by others from Blair Athol, also in Perthshire, and part of the clan Robertson lands, and from Mull in the Western Highlands. To give just one powerful example, 56 years after Alexander Robertson came to Big Island in 1787, his niece Isabel MacGlashan from Blair Athol followed him to Big Island with her husband and young son in 1843. Oral history among Robertson’s descendants on Big Island confirms that the early settlers on the island knew each other in Scotland before they emigrated, and were neighbours and friends on both sides of the Atlantic.34 Chain migration not only established initial patterns of settlement; it created strong echoes that have persisted for generations. In the case of Big Island settlement, chain migration may also have mitigated to some extent a problem encountered by late-coming Highland settlers in other parts of Nova Scotia: a paucity of high-quality land for improvement and cultivation.35 The tight family connections evident across the waves of immigration to Big Island at least partially insulated later arrivals against the full range of hardships that were experienced by their contemporaries in other settlement areas. Land clearances were facilitated by the availability and efforts of neighbours in the community, and the earlier settlers aided the later arrivals with advice, clothing, and provisions that could be spared.

18 In addition to physical geography and climatic similarity, the availability of natural resources was a significant pull factor in the Scottish settlement of Nova Scotia. The burgeoning timber trade at the end of the 18th century was an “enormous magnet” for Nova Scotian immigration.36 Historian Lucille Campey goes as far as to argue that “but for Canada’s timber trade with Britain, this great exodus of Scots could not have happened.”37 As Britain’s landscape became more and more denuded of forests during the Industrial Revolution and new tariffs on continental timber imports after 1812 drove prices up sharply, tapping into the resource base of the colonies became even more appealing. Nova Scotia had a plethora of fine trees suitable for the planking and masting of ships, but it suffered from a dearth of workers. The timber industry boom is therefore another reason why so many ships left Scotland during this period: trade-ships sailed west across the ocean, carrying Scottish settlers as cargo, and sailed back with holds full of timber, a resource that was both economically important and strategically critical. The Scots were the first Europeans to settle permanently on the North Shore of Nova Scotia and they slowly carved a niche into the environment they found there, initially by clearing timber to send overseas. As they cleared, the settlers uncovered land of a fertility similar to that which they had farmed in the Highlands. They were therefore able to apply well-known agricultural techniques from their old world to supply their needs in the new.38 As geographer Cole Harris explains: “Their hand implements – spade, cas chrom(wooden hand plough), and hoe – were more efficient tools in stumpy, semi-cleared fields than animal-drawn ploughs and harrows, which they did not know and had never used in Scotland.”39 Although they found themselves in an unfamiliar landscape, settlers could at least take comfort in their employment of familiar agriculture techniques. Timber culling and tilling the land went hand-in-hand. Timber extraction was the economic basis of the early Scottish Nova Scotian settlement experience, but agriculture was its foundation. Settlers from the Hector, for example, landed in Pictou in 1773 and exported their first shipment of lumber just two years later, in 1775.40 Timber is also responsible for the enduring settlement patterns on the North Shore: settlements such as those on Big Island developed near timbered lands and around harbours and rivers, which facilitated the transport of the resource to markets both regionally and across the Atlantic. According to the island’s oral tradition, oak was harvested from Big Island as early as French colonial times, and this continued during the Scottish settlement period. Pictou Harbour in particular became a hub for the timber trade, serving as the region’s entrepot for settlers flowing in and timber flowing out.41 The culturally Scottish geographic enclave that continues to prosper along the North Shore is therefore a direct result of the region’s historic timber trade.

19 A collection of secondary environmental pull factors also contributed to the Scots’ decision to emigrate. Of the British Empire’s colonies in the 18th century, the Atlantic region was quite simply the destination closest to Scotland – which meant the most affordable passages.42 The Maritimes also shared a similar climate with Scotland, and the Highland emigrants were not deterred by the region’s cold, fog, and wet weather although they did have to get used to more snow than was common in Scotland. Out of all the Maritime provinces, Nova Scotia in particular was attractive to settlers because it was a predominantly coastal environment, aesthetically similar to Scotland.43 The deep, land-locked forests of New Brunswick and the gently rolling, pastoral landscape of Prince Edward Island were striking in their own way, but they did not offer quite the same reflection of Scotland as Nova Scotia’s rugged landscape.44 For those Scottish settlers who had grown up in the Hebrides, the Western Isles, or along the Highland coasts, the opportunity to resettle to coastal locations must have been a powerful, deeply felt draw. Furthermore, as J.M. Bumsted first discussed in the pages of this journal45 and then developed much more extensively in his People’s Clearance, at least in the first phase of the Clearances, which Bumsted defined as running from the end of the Seven Years’ War to the end of the Napoleonic Wars, pull factors weighed heavily in the decisions of Scots to leave their homeland. In his view, “the Highlanders . . . had a fairly clear idea of what they were doing in opting for emigration.”46 Awareness of the existence of a landscape that offered the geographic familiarity of home would likely have been especially attractive, on its own merits, to these self-directed Scottish migrants.

20 Taken together, environmental pull factors drew many Scottish Highlanders to emigrate to Nova Scotia. They traded an increasingly uncertain world of absentee-owned sheep farms, the appalling drudgery of kelp-making, the horror of collapsing clans, famine, and overpopulation for a new one of seemingly abundant land in an environment that rewarded a pioneering, independent spirit and promised economic security through timber processing and self-sustaining agriculture. They traded one side of the sea for the other, but in so doing they also traded one kind of life – of narrowing horizons and shrinking opportunity – for another that promised the opposite. Nova Scotia presented a clean slate, but it also posed brand-new challenges and adjustments would be required. In the oral history of Big Island’s MacGlashan family, for instance, is the story of James MacGlashan, who emigrated with his family from Blair Athol. A three-year-old in October of 1843, he disembarked the ship wearing nothing but a thin homespun shirt and a kilt. The MacGlashans soon discovered that October in Nova Scotia was not October in Blair Athol, and they and the women of their new community soon traded their kilts for stout pairs of britches more suitable for the harsher winters. The tartan kilt was therefore abandoned as day-to-day apparel by the Scottish settlers, although both kilt and tartan retained overwhelming cultural currency in the new communities in Nova Scotia. The settlers changed in apparent ways, just as they began the process of transformation of their new environments into something more familiar – a New Scotland in ways more than just in name, a New Europe across the sea.

21 As noted above, the most significant change wrought by Scottish settlers was also the most immediate: the clearing of the land and the implementation of agriculture. Clearing the land had already been initiated in many areas by the timber trade, but during the latter 18th century Nova Scotia was still far more forested than the Scots’ denuded homeland. Wrestling the thick forests into cultivation was not easy work. John MacLean, who settled in Barney’s River across the harbour from Big Island, evokes the discouraging and difficult process needed to turn a foreign landscape into a home in his poem A’Choille Ghruamach (The Gloomy Forest):

Behind the hills in this gloomy wood

In this lone desert by Barney’s River,

With bare potatoes alone for food.

Ere cultivation is seen rejoicing

O’er all the land and the trees are cleared,

My strength will foil in an arm exhausted

While yet the children are left unreared.47

22 While the wooded landscape in which MacLean and many others like him found themselves was not domesticated, it was domesticable and they soon adjusted it so they could do the work they had always done. In this way, agricultural settlers were “ecological revolutionaries.”48 The Highlanders were independent-minded farmers who were used to rocky soil and short growing seasons.49 They applied the same mixed farming techniques they had used in Scotland, inasmuch as they set about raising a few sheep or cattle and planting arable crops and vegetables where possible.50 A 1793 poll tax return only includes one definitive Big Island head of household – Alexander Robertson – but notes that he owns two cattle or horses and ten sheep while the other Merigomish settlers on the return average a modest two cattle or horses and two or three sheep – a small, solid base for a mixed farm.51 By 1858, numbers had grown. An assessment bill for that year records 17 rateable inhabitants of Big Island. The document records the number of horses, oxen, cows, sheep, and acres of land each Islander owns, as well as their subsequent valuation and collection rates. The number of livestock, for instance, ranges from one to two horses, two to nine cattle, and ten to twenty sheep. Farm size ranges from twenty-three acres to one hundred and sixty acres.53

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

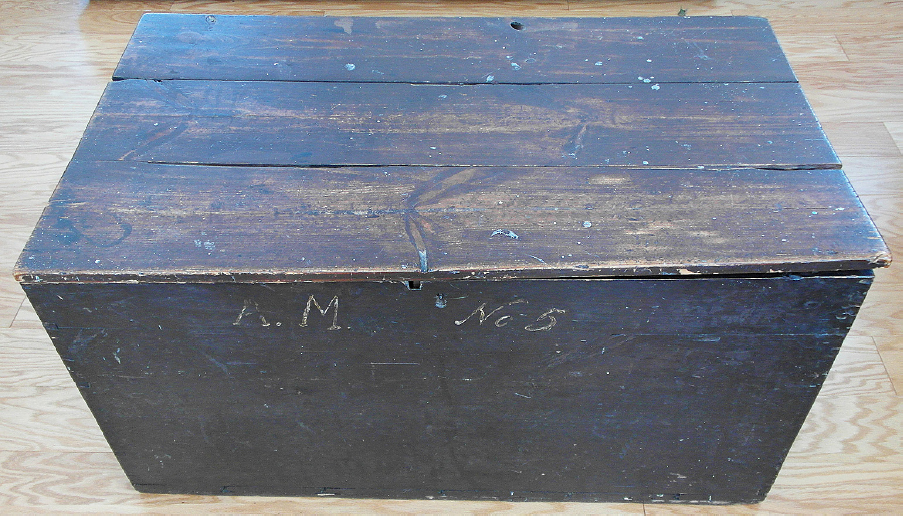

23 With land cleared and farming begun, Highland settlers were able to sculpt a New Europe and a New Scotland and begin to establish lives that were uniformly better than the ones they had left behind. As one commentator remarked, “Even the long hut, in the depths of the forest, is a palace compared with some of the turf cabins of Sutherland or the Hebrides.”54 While Nova Scotia’s soil was adequate agriculturally, it was, with only a few exceptions, by no means rich. Consequently, high-density agriculture did not develop in most of the province as it did, for example, along the St. Lawrence or on Prince Edward Island, where agricultural communities were characterized by significant socioeconomic stratification. Farming communities in Nova Scotia were invariably successful but modest in their means. The Scottish settlers inhabited fairly independent communities in which societal organization remained relatively flat. The Nova Scotian settlement patterns produced geographic enclaves that moulded the Scottish settlers into a “patchwork pattern of peoples” on the landscape, a pattern characterized by minimal social stratification.56 Like little James MacGlashan and his parents who came in 1843 with five trunks to their name (See Figure 4), many families came with modest means but were by no means destitute. This pattern – of modest success – continued to define the Scottish experience on Big Island.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

24 Scottish settlers were interested in making an honest, moderate living in this new landscape, and most importantly, remaining free. Writing about the impact of Highland Regiments settling on their new land grants in North America, historian G. Murray Logan gives insight into the Scottish psyche of the late 18th century:

25 Clearly, the values of liberty and self-determination must have served as powerful motivation, and justification, for many settlers. They were willing to give up everything they had known – their home, their family – for the possibility of freedom in an unknown landscape. In the New World, Highlanders could truly exercise their free will. A 1749 advertisement from the Gentleman’s Magazine also taps into this spirit:

O’er as happy a country as ever was seen

And blessed her subjects, both little and great

With each a good house and a pretty estate.

No landlords are there the poor tenant to tease

No lawyers to bully, no Bailiff to seize.58

The verse perfectly captures what was so attractive about the New World to Highlanders: it represented freedom from oppressors, whether they be landlords or lawyers, and a freedom to do what they pleased with their own land. On Big Island, immigrants’ ideas of a “good house and a pretty estate” can still be seen in the simple, modest, wood-frame houses that first-generation settlers built for themselves upon arriving in Nova Scotia (Figure 5).

26 The MacLean home on Big Island, for example, was built in two stages: first, the cellar was excavated and lined with stone; covered with floorboards it served as shelter for the first winter’s occupation. Next, the MacLeans constructed the upper floors with rough-hewn timber, which is still visible today. These were not lavish homes, but they were practical and comfortable. Similarly, during a visit to Pictou County in September 1803, Lord Selkirk describes the farm of one of the original settlers from the Hector, who had arrived 30 years before:

Highlanders had therefore set about recreating the way of life that they had lost in Scotland: one based on self-sufficient, small-scale farming. As Cole Harris notes:

Nova Scotia’s ample plots of land and general geographic isolation offered a refuge from the encroachment of aggressive market economies and rampant industrialization. Aside from what one commentator deemed “the extravagant desire they cherish to purchase large quantities of land,” Highlanders tended to live modestly and independently.61 They owned their own land because they cherished the freedom of being their own masters. This freedom and control created a distinctive settlement pattern on Big Island. Using the natural contours of the gently sloped land, Islanders built individual homesteads on the low-lying harbour side, forging connections with the mainland community, and farmed the upland side facing the Northumberland Strait. The same basic pattern survives on the island to this day. It is clear that moderation, loyalty to landscape, freedom, and autonomy are all still very much a part of Scottish cultural identity. Scottish landlords may have been concerned first and foremost about the capitalist market economy, but Scots in Nova Scotia were free to farm and treat agriculture as a way of life rather than a mechanism for the profit of others.62 But neither were they bucolic nor insular. Many chose to participate in market economy activities such as the timber trade to supplement their income, but the key was that it was their choice and not that of a landlord, a bailiff, or a lawyer. Owning their own land and making their own choices about how to use it were critical factors in the Highland settlers’ sense of autonomy and independence. Best of all, in this New Europe there was little to no threat of eviction.

27 It is therefore a tragic irony that the very security established in Nova Scotia by the dispossessed occurred at the same time as the dispossession of others. John Reid states in the pages of this journal that the arrival of the Scots led to “increasing territorial encroachment [which] eroded Native resource harvesting as well as raising related issue such as the desecration of sacred sites and the non-Native occupation of areas that even by colonial authorities had been designated formally or informally for Native use.”63 Displacement of the Mi’kmaq by the Scots has been examined in the Cape Breton context,64 but the extent to which it may have been a factor in the Scottish settlement of Big Island is unknown.65 Also largely unknown are the potential differences and similarities between Mi’kmaq and Scottish conceptions of, and relationships with, the landscape and topography around the North Shore/Piktuk more broadly.66 While this is far beyond the scope of this particular environmental history, it could be an insightful line of future inquiry.

28 One certain difference, however, is the agriculturalization of the land, and, once agriculture was firmly established, Scottish settlers began to develop the infrastructure necessary to drive the civic evolution of their new communities. Better, stronger infrastructure empowered immigrants in their pursuit to live independently. Infrastructural development enabled them to continue to build their new homes, their new lives, and their New Europe on their own terms. Roads were often the initial step towards formal physical infrastructure.67 Members of the 84th Regiment, experiencing similar hardship to their 82nd Regiment comrades in Merigomish, petitioned the governor for help building a road connecting Nine Mile River in Pictou County to other parts of the county. Explaining their predicament, the petition reads:

29 Physical infrastructure eased the challenges faced by the settlers on Big Island; the island’s first road ran near to the water on the Merigomish Harbour-side of the island, reflecting the harbour’s importance for early settlers.69 To Highland emigrants, roads meant connections and connections drove community. Transportation, communication, everyday life, and community centered around water, and roads allowed this community to grow. There is a poignant passage from a 1908 petition in the Nova Scotia Archives, in which Big Islanders write asking for telephone poles to be installed along the causeway connecting the island to the mainland:

Although the petition is of a later date than those discussed above, it nevertheless attests to both the importance of reliable roads as providing social connection and also the centrality of Merigomish Harbour for Islanders – highlighting the role that physical geography can play in defining a community.

30 Social infrastructure also developed in tandem with physical infrastructure. Once there were enough people in a given area, settlers sometimes built a collective community space such as a church or a school.71 Big Islanders, for their part, petitioned for help building a schoolhouse in 1853.72 By 1858, Big Island was referred to as a school district in assessment documents and had appointed its own collector of school rates.73 Although there was never a church on Big Island, residents would travel directly across the harbour to Merigomish every Sunday to attend services.74 The beginnings of economic infrastructure also eventually emerged. Islanders petitioned for assistance in building a wharf in 1870 and again in 1880.75 On Big Island, where life centered around water, a wharf provided both a key means of transportation and an essential piece of physical infrastructure for the burgeoning fishing industry, which complemented farming.

31 It is clear that within a few decades of arriving – by clearing land, establishing agriculture, and developing infrastructure – Scottish settlers were transforming Nova Scotia from what effectively had been a timber-trade outpost into a home across the sea. In the space of less than a century from the arrival of the first settlers on the North Shore of Nova Scotia, a community network of farms, churches, schools, and roads developed from what once had been a few coarse dwellings and scattered rough blazes through the woods.76 Individual family farms remained the basic unit of settlement, the axis upon which everything else turned. Clusters of farms were often organized according to family ties or friendships brought from Scotland. These clusters of homes and farms served as the larger social community, and in places like Big Island they still do.

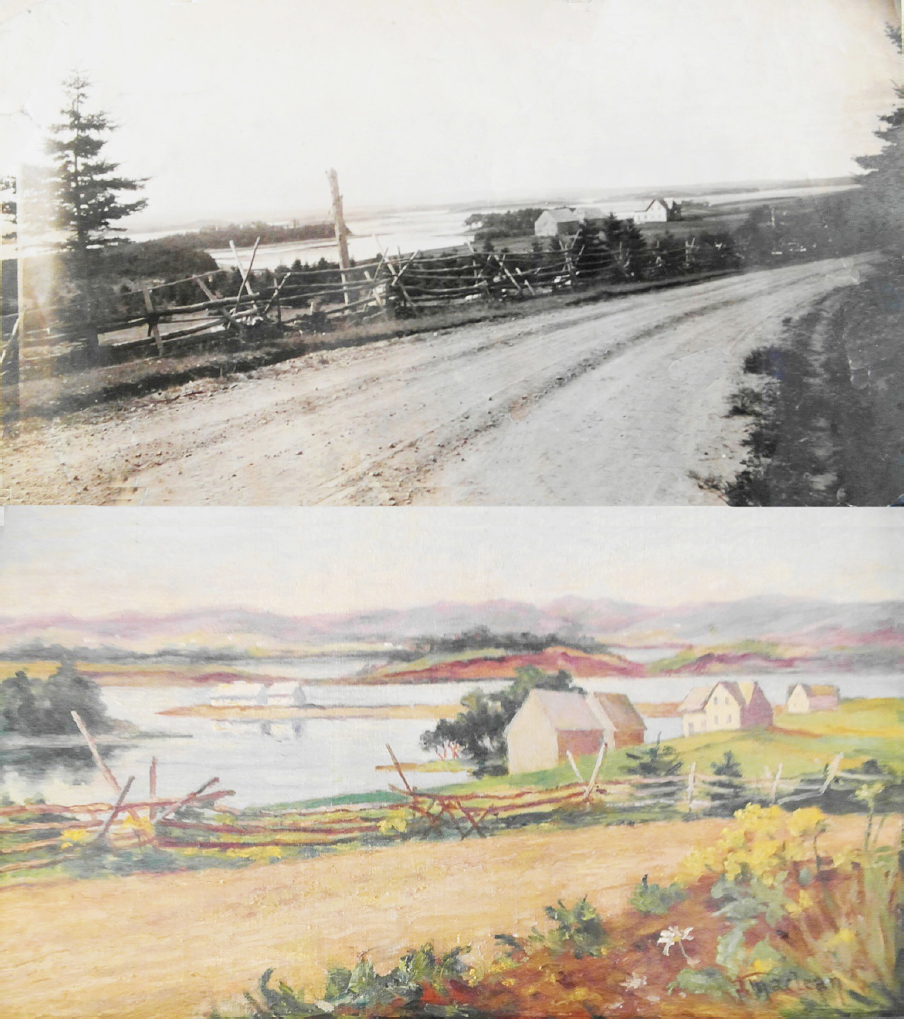

32 While Scottish settlement patterns centered on the countryside, there was also development in towns and it is important to consider rural settlements like Big Island in this wider context. One resident of Pictou estimated there were about 500 living in the harbour town in 1788, and “a few more” around Merigomish harbour.77 By the turn of the 19th century, Pictou had grown to “sixteen or eighteen buildings, including barns, a blacksmith shop and the jail, closely environed by the woods. There was no church, but a place was fitted up in a shed . . . where service was held in the summer, but in winter time it was in private houses.” Further up the coast, settlement around the East River also eventually became the sizeable town of New Glasgow.78 Despite these semi-urban communities, markets and industry on the North Shore remained largely decentralized because of the isolated physical geography of the province.79 This, combined with the ample amount of agricultural land available, enabled Scottish settlers to remain relatively rural and recreate the home they had lost across the sea (Figure 6).

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

33 The new pattern of rural economy in Nova Scotia looked strikingly similar to the old Highland model of mixed subsistence agriculture in clusters of families and friends.80 Essentially, Scottish settlers recreated clachans – small Highland villages – along rivers, around harbours, and all along the North Shore, adding to them the infrastructure they needed to live independently. Nova Scotia’s physical environment lent itself naturally to rural and decentralized patterns of settlement, and Scottish settlers deliberately took advantage of this, forging communities with “intense local attachments where most people found the principal meanings of their lives.”81 The basic framework they created still exists, largely unchanged, and reflects the deep imprint that the settlement patterns of 18th- and 19th-century Scottish immigrants have left on Nova Scotia’s landscape.

34 The Scots also transported their culture through place names and monuments as well as through their agricultural practices and community structure. In doing so, they put the final touches on their new home and New Europe. Scottish place names run all along the North Shore of Nova Scotia, ranging from the obvious (New Glasgow) to the obscure (Lismore). Like Scotland, Pictou County has an Arsaig, a Glengarry, a Knoydart, a Gairloch, and a Loch Broom.82 As well as naming many of Nova Scotia’s towns and villages, Scots assigned Gaelic names to local natural features. Place names were an easy way for settlers to give a new, intimidating landscape a more familiar, Scottish identity.83 In doing so, settlers quite literally “grounded the past into the present.”84 On Big Island, the senior Alexander Robertson christened his house “Struan,” named after his home in Perthshire, and a nearby bluff gained the wartime nickname of his fellow 82nd Regiment comrade, Robert “Smashem” Stewart, who lived there and acted as Robertson’s agent (Figure 7). When plotted on a map, Scottish nomenclature, whether inherited from the geography and people of the Highlands or newly christened in Gaelic, gives a striking visual representation of immigration patterns.85 On Big Island and elsewhere along the North Shore, place names strikingly show the indelible imprint that Scottish settlers left on their landscape.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

35 Another way to imprint Scottish characteristics on the landscape was by building monuments and memorials. Down the road from Big Island, for example, in Knoydart, there is a cairn overlooking the Northumberland Strait built in remembrance of those who fought at the Battle of Culloden. More than a simple memorial, the Culloden Cairn actually marks the burial place of three survivors of that famous battle.86 It was likely both comforting and a cultural anchor for settlers in a land far away from home to possess not merely a familiar reminder of that home but a remembrance of the moment when Highland power was shattered in the Jacobite cause, a moment that ushered in such misery for the Highlanders and began the wave of emigration to the new lands across the Atlantic. Place names and monuments provided that piece of home, and, along with agriculture and infrastructure, together formed a cultural, social, and economic web within which Scottish settlers built a New Scotland in Nova Scotia – a distinctive geopolitical and cultural entity that extended well beyond a simple name harkening back to auld lang syne.

36 The Scottish migration story to Nova Scotia is not a unique one as every emigrant group has experienced push and pull factors, times of adjustment and rebuilding, and periods of hardship and plenty. Like the Highland Scots, the Acadians and the Irish share the connection between cultural values and environmental values. In varying degrees and ways, each group’s immigrant story is tied closely to land – its structures and limitations defined them culturally and economically.87 Acadians recreated as best they could their French homeland on the new landscape, in which “low population densities, strong communal bonds, . . . and land reclamation schemes” took centre stage.88 The Scots’ close comrades and Celtic cousins, the Irish, are renowned for their “preoccupation with the nature of place” and the “mystical” and “magic” bonds they form with their landscape, whether inherited in the Old World or adopted in the New.89 Like the Irish, Scottish clans viewed land not only in ecological terms, but in sacred terms too: it represented an “ancestral home,” “the kinship of one generation to another,” and the connection between “the tribe and the soil.”90 What makes the Highland story notable, however, is the almost-identical nature of the bioregional zone in which settlers found themselves compared to the bioregion they had left.91 In Nova Scotia Highlanders found, by choice and by chance, a near-perfect reflection of home.

37 Big Island stands as a testament to this power of place. The island is still undeniably clannish; it remains an extremely cohesive community of about 40 full-time residents after more than 200 years. In the future, further study of the island should be undertaken using, perhaps, the burgeoning scholarship on “islandness.”92 For now, Big Island – and Scottish immigration to Nova Scotia in general – are examples of cases where using place instead of time as a context for history can better serve our understanding of the past as it continues to echo through the present.93 In environmental history, landscapes like Big Island convey a sense of timelessness. Time there unfolds like a continuum rather than a chronology, with the landscape itself acting as the constant.

38 Highland emigration to Nova Scotia is part of the broader historical and ecological phenomenon of “cultural and intellectual transport from Europe to North America” and the “expansion of European people and ideas.”94 This includes ideas about landscape and the nature of our relationship to the environment. In many ways, Highland emigration is the story of the collision between the old ecological view of land and a new industrial capitalist economy defined by commercial farming and industrial activity. Once it became clear they could no longer live where they wanted and in the manner that defined them, many Highlanders chose to emigrate. Most Highlanders refused to be reduced to wage labour, separated from both their land and their family and clan kinship structures. Instead, they sailed across the ocean with the hope of finding a new land to farm and raise their families. A few found their hopes fulfilled on Big Island. There, they recreated a Scotland that had been lost to them, carving small farms out of the mediocre soil, making a modest living, and staying for generations. There, they created deep landscape memory. For historians, studying places like Big Island reveals that the landscape itself can be the aide-memoire; the landscape itself acts as the parchment to record the past. On Big Island, Scottish settlers and their descendants could once again build a life based on loyalty – to the land, the people, and the place. Their legacy is indeed visible.