Articles

Rehousing Good Citizens:

Gender, Class, and Family Ideals in the St. John’s Housing Authority Survey of the Inner City of St. John’s, 1951 and 1952

This article investigates how gendered middle class family ideals were used to relocate administratively defined “good citizens” from a multidimensional yet often demonized “slum” neighbourhood in St. John’s in the 1950s and 1960s. We argue that under the guise of urban renewal, notions of “good citizens” and “good families” were reconstructed along gendered and class lines through housing eligibility criteria for new subsidized housing projects. Our findings show how housing eligibility criteria initially rehoused only specific families from the inner city area. We conclude by discussing the implications of urban renewal in St. John’s for historical work on modernity and on slum clearance.

Cet article examine comment on s’est appuyé sur un idéal sexué de la famille de classe moyenne pour relocaliser de « bons citoyens », selon la définition administrative, d’un quartier de taudis aux multiples dimensions et pourtant diabolisé de St. John’s dans les années 1950 et 1960. Nous soutenons que, sous le couvert du reaménagement urbain, les notions de « bons citoyens » et de « bonnes familles » ont été redéfinies en fonction du sexe et de la classe par les critères d’admissibilité à de nouveaux logements subventionnées. Nous avons constaté qu’au départ seules certaines familles du noyau central de la ville répondaient aux critères d’obtention d’un nouveau logement. Pour conclure, nous étudions les implications du réaménagement urbain à St. John’s pour les recherches historiques sur la modernité et sur l’élimination des taudis.

1 A CASUAL WALK ALONG THE NORTH SIDE OF NEW GOWER STREET in contemporary St. John’s takes the pedestrian by the Delta Hotel, office buildings, Mile One Stadium, and City Hall. Across the street lies the St. John’s Convention Centre, which is connected by a pedway to City Hall. If the pedestrian looks at the rock face behind City Hall and Mile One Stadium, they are glancing at part of an area that once contained the “central slum” of St. John’s. The hillside behind the buildings in this area once contained 1,500 people. 1 From 1950 to 1966, all of the residents were removed, first under the guise of better housing (1950 to 1956) and later (1960 to 1964) under the auspices of urban renewal. This article analyzes the classed and gendered assessments that planning officials made for the relocations from 1950 to 1956, and argues that the relocation of inhabitants out of the city centre was based on specific narrow constructs of masculinity, femininity, family, and citizen.

2 This article is comprised of six sections. First, we situate the context that informed the planning process from 1950 to 1956 in St. John’s. This was the slow movement towards slum clearance and social housing initiated by the Canadian state in the 1940s and 1950s. 2 The early part of this period predates Newfoundland’s entry into Confederation, but was instrumental in “solving” the slum issue. Reforms to the National Housing Act in 1944 and the emergence of Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation as a funding body in 1946 fostered social housing within a framework that favoured private-sector construction of single-family homes. Canadian municipalities dating to the 1930s had pressured the federal government to do something about slums in their inner cities, and the 1950s was the first realization of significant federal support in this area. We briefly examine the impact of the slum clearance and urban renewal efforts sponsored by the Canadian state in the cities of Halifax, Saint John, and Toronto. Urban planners sought nuclear families in detached houses as the “ideal” family type. While planners, politicians, and administrative officials sought “modern” ways of architecture and living, the removal of inner-city dwellers from slums differed from one context to the next. Those involved in the planning process developed, through surveys and other measures, knowledge about the communities they were relocating. 3 Efforts at slum clearance, urban renewal, and social housing were not just about relocating “slum dwellers” to more favourable surroundings; these were also premised on rehousing appropriate families – more specifically nuclear families. Along with properly planned social housing developments, nuclear families provided the basis for constructing modernity in cities. By modernity, we mean material practices, bureaucratic processes, spatial arrangements, and day-to-day forms of social interaction that embrace formal rules and regulations. We conclude the first section by showing how nuclear families, while dominant, were just one family type in Canada on the eve of social housing. However, St. John’s planning officials looked to the nuclear family as the desirable type of modern family for new public housing developments.

3 Second, we review the social and demographic features of St. John’s in the 1940s. We introduce the problem of the “central slum” of St. John’s to show that the planning vision there since the 1940s was to provide homes in new locations for those who were “better off”; this would initiate a “filtering up” process whereby poorer residents in the slum would occupy the homes left by those moving to a new development – Churchill Park. This did not happen. Churchill Park became a middle class suburb. This sets the context for the post-Confederation period (after 1949), when Newfoundland’s slum clearance and planning processes had parallels recognized by writers elsewhere in North America as well as in the United Kingdom. 4

4 The third section takes us to the first decade after Confederation when the St. John’s Housing Authority conducted a survey (1951 and 1952) to determine the eligibility for public housing financed by Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation and the Province of Newfoundland. From 1950 to 1956, the planning process showed an early preference for stable nuclear families. This survey included gendered and classed notions of “good citizenship” and “good homemaker” as a basis for determining eligibility. In addition, only families that could afford to pay a minimum rental rate were approved. In the process, “good citizen” homeowners and “poor citizen” renters (and non-renters) were deemed ineligible for relocation. Qualitative information from the surveys on these matters is covered in section four.

5 Section five begins with a brief discussion of what happened to those not relocated between 1950 and 1956. In the early 1960s, under the guise of urban renewal, the City of St. John’s cleared out the remaining inhabitants (through expropriation of homeowners if necessary). And in the 1970s and 1980s the City of St. John’s moved to commercialize the former “central slum” while also providing some low-income housing in the area. Today, some urban poor remain in the inner city of St. John’s. Despite the emergence of St. John’s as a servicing base for the offshore oil and gas industry, the remaining urban poor in the city centre have not benefitted from this new wealth. Today, some rely upon food banks. In the meantime, the Newfoundland and Labrador Housing Corporation assesses who among the urban poor are eligible for social housing.

6 We conclude by situating the St. John’s experience within the context of the connections between slum clearance and modernity. While there was a bias in favour of stable families in St. John’s, the experience of this city, like its Canadian counterparts, shows the need to reconsider slum clearance, social housing, and urban renewal as a negotiated and conflicted process in which the ultimate outcome was not fully determined by the original design. Despite the variations in planning outcomes, concerns with modernity were part of the ideology behind slum clearance and urban renewal in Canada.

Slum clearance, urban renewal, social housing, and modernity in Canada, 1946 to 1964

7 Changes to the National Housing Act (NHA) in 1944 (as well as subsequent changes) and the emergence of Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) in 1946 had implications for housing for the subsequent three decades. The 1944 NHA provided for the financing of social housing in Canadian cities. CMHC emerged as a financer of both market-based and non-market-based housing in Canada. 5 In Canada’s cities, the NHA and CMHC influenced the housing of war veterans (late 1940s), early public housing (early 1950s), and urban renewal (1960s). 6 Since the latter two are important for our purposes, this section briefly reviews their impact on Canadian cities and the selection of appropriate families. The modernity involved in these efforts was not just about housing; it was also about the housing of socially appropriate families.

8 Public housing in the 1950s and 1960s favoured nuclear families. CMHC, by insuring mortgages during the 1950s, fostered the entry of the banks into the private housing market. This supported the expansion of middle class suburbs of detached homes. 7 When it came to public housing, the detached single-family suburban home informed CMHC and provincial housing policies. Even if the form of public housing consisted of row houses or apartments, the single-family dwelling became the norm of housing policy.

9 The CMHC policy critical to public housing in postwar Canada is the 75 per cent federal and 25 per cent provincial contribution to housing developments. 8 Thus municipalities, which are under provincial jurisdiction, finally had the financial leverage to deal with “slum housing” conditions. Brendan Gemmel writes that Halifax (1931), Hamilton (1932), Toronto (1934), Winnipeg (1934), and Montreal and Ottawa (both in 1935) had surveys during the Great Depression documenting deteriorating housing conditions. 9 We can add to this the survey conducted during Second World War in St. John’s by the Commission of Enquiry into Housing and Town Planning on the housing needs of the “central slum” and other areas in the city. 10

10 Regent Park in Toronto in 1947, the first fully public housing development in Canada, was followed by public housing efforts in other Canadian cities in the postwar period. 11 The implementation of public housing differed from one city to the next, but slum clearance, and the surveys of residents in “designated slum areas” that accompanied it, was often informed by a common ideology – one that connected new housing to appropriate families.

11 There is a broad literature on slum clearance and urban renewal that helps to situate the St. John’s case within a larger context. Whether we are looking at classic ethnographies of working class slums on the eve of clearance such as Michael Young and Peter Wilmott’s study of Bethnal Green in East London and Herbert J. Gans’s work on the Italians in the west of Boston in the 1950s – or Canadian works such as Donald Clairmont and Denis W. Magill’s investigations of Africville in Halifax, Greg Marquis’s studies on urban renewal in Saint John, Richard White’s work on Toronto, or Kay J. Anderson’s consideration of the Chinese in Vancouver – issues of modernity are at play. 12 While these writers are critical about the impact of modernity, all acknowledge that, for the working class in these cities, plans were being made to reorder their lives according to some rational design. However, not everyone in need of housing was included in the housing plans.

12 In Canadian cities, slum clearance and the urban renewal process show a degree of variation. And, as White shows for Toronto, it is important to look at slum clearance and urban renewal as distinct phases. 13 Slum clearance was closely connected to early public housing developments in Toronto and other Canadian cities in the 1950s. Urban renewal usually followed in the 1960s. In this case, social housing was only one objective in Toronto and other Canadian cities as urban regeneration plans were also connected to the commercialization of areas that once contained housing. Toronto’s 1947 Regent Park project resulted in the clearing of homes and rebuilding in the same area. However, not all original inhabitants were rehoused in the new development. Sean Purdy notes: “By the time the project was fully constructed, more than half of the apartments and houses were occupied by families who had not lived in the areas before.” 14 White states that some of the applicants for the new Regent Park housing were “not eligible since destitute families elsewhere in the city were considered a higher priority than some of the displaced local residents.” 15 Leases for the new development included the ability to pay a given rent as well as prohibitions on the housing of “multiple families” or the operation of “commercial enterprises.” 16

13 In Toronto the original slum clearance plans were also never fully executed, and, in the midst of some urban renewal plans, resistance by some city residents shaped eventual outcomes. This is present in the dispute over the planning of the never-completed Spadina Expressway. 17 Moreover, tenants in Regent Park as early as the 1960s organized to protest the poor maintenance of the housing project; by the early 1970s, they were also campaigning for fair rents. 18 White argues that while “rational” elements were in place, there was not as much urban renewal in Toronto as critics claimed. 19

14 Halifax had a 1945 master plan dedicated to the study of slum clearance that focused upon several areas, including the North End and Africville. 20 The latter was located on the north shore of the Bedford Basin; Africville was settled in the 1840s by Black refugees from the War of 1812. 21 In the early 1950s, the Halifax Housing Authority built some low-cost housing near the Halifax Commons in the North End. 22 The 1953 Bayers Road Project consisted of 161 units and did not admit families with incomes less that $1,500 per year. The project received 1,000 applications. 23 While Halifax City Council deliberated over slum clearance, it was only in 1956, when CMHC recommended the English planner Gordon Stephenson to do an urban renewal study, that plans for slum clearance and urban renewal took off. 24

15 The neglected Africville “slum” – located near a garbage dump – became one of the areas studied in preparation for clearance and urban renewal. It is the current location of the MacKay Bridge, a classic case of urban renewal connected with “slum” clearance. Despite the outcome, Tina Loo argues that in the lead up to the clearance “progressive reformers” showed concern about the plight of black residents. In the clearance of Africville, however, much discretion was vested in a single social worker. He collected intimate knowledge about the day-to-day lives of the people being relocated. Moreover, this social worker was dealing with homeowners who often lacked secure legal title to their properties. 25 This eventually influenced the transition of homeowners into single-family dwellings or social housing. Clairmont and Magill note that only one-third of all of Africville residents were homeowners after their relocation. 26

16 Finally, for Saint John, Marquis shows discretion was at work in the designation and clearance of slum areas. Despite the shortage of good housing, there was little public housing in the city until the 1940s. In the postwar period, as was the case for other Canadian cities, Saint John’s housing was subject to studies planning slum removal. This included a 1947 master plan that guided slum clearance and urban renewal projects in the 1950s and 1960s. The 1956 Potvin Report recommended the demolition of nearly one-third of the 13,000 residences in the city. Yet the slum clearance and urban renewal projects of the 1950s and 1960s did not solve the affordable housing shortages in the city. Marquis argues that if not for the population decline in the city after 1965 the level of housing need would have worsened. Moreover, Marquis shows that by this time urban renewal efforts were also dedicated to commercializing inner city areas as well as the Saint John Harbour area. 27

17 Toronto, Halifax, and Saint John are important to our story. In each of these cases, city planners were also deciding who should be housed. There was, in many cases, a scarcity of new social housing. As we have seen, Regent Park in Toronto did not rehouse all of the former inhabitants of the area cleared for this new development. And some social differentiation was at work. In Halifax, the decisions concerning Africville residents reflected how the absence of a formal land title informed whether residents would be able to sell their homes and move into new market-based homes or into social housing. In each case, decisions on eligibility were being made. These decisions often involved the selection of appropriate families, an important dimension to our story about St. John’s. Who were these families, and how was appropriateness decided?

18 Integral to such selection were the conceptualizations of the family and modernity. Few concepts have been as much debated as modernity. Modernization broadly, according to Marshall Berman, is an ongoing process of social and cultural renewal shaped by scientific advancements, technological growth, migration, and industrial development that had overarching consequences for restructuring our reality. This ever-present idea to be the first, and to do what is new, has shifted over time. While Berman’s overall thesis is to show how modernity is not solid, he does state that after the First World War the ideological framing of modernity was such that, more so than in other time periods, modernity was something that was seen as solid and unchanging – which it obviously was not.

19 After the First World War, notions of modernity became more polarized and narrow than just a century earlier. Berman explains this change: “Their twentieth-century successors have lurched far more toward rigid polarities and flat totalizations. Modernity is either embraced with blind and uncritical enthusiasm, or else condemned with a neo-Olympian remoteness and contempt . . . . Open visions of modern life have been supplanted by closed ones, Both/And by Either/Or.” After the Second World War, modernity was something that could be exported to those who needed it – namely the “developing” world but also to those areas in the “developed” world that were decidedly un-modern, such as urban slums. 28 For functionalist thinkers in the social sciences after the Second World War, the dimensions of achievement and economic growth were connected with modernity as realized by the expansion of nuclear families and suburbs. 29 For urban planners, influenced by modernity, social progress was stalled by densely populated slums that did not have the living features necessary for a modern world. They put forward architectural designs and urban planning arrangements that would supposedly provide better living for all. 30

20 While once accepted in social science literature as progressive, modernity is now is often reviled for undermining the lives of many people – especially within the context of the need to assimilate pre-modern people to modern views and lifestyles. The slum clearance and urban renewal plans and outcomes in Canada, the United States, and Europe have come under heavy criticism in recent years in that communities were undermined in the name of social progress. 31

21 For our purposes, modernity is pertinent in terms of the role that it assumed since the early 1950s in the slum clearance and urban renewal projects that took place in St. John’s. Embedded in these projects was a concern about having appropriate families ready to occupy the social housing projects, an approach that had much in common with what was to happen in Canada during the 1950s and 1960s.

22 According to the functionalist perspective, modernity ushers forth the nuclear family as the “family type” appropriate for industrial society. 32 Whereas the extended family was conducive to a pre-industrial agricultural society, the nuclear family integrated well with the spatial mobility patterns required by industrial society in the early post-Second World War period (the 1950s and 1960s). The nuclear (or “natural”) family for functionalists was a heterosexual family with children living at home. 33 These families had a gendered division of labour, with males performing “instrumental roles” in the public labour force and females assuming “nurturing roles” in the privacy of the home. Children, in turn, were socialized into appropriate roles as the nuclear family prepared them for schooling and other social functions that had been performed by the family in a pre-industrial period.

23 While the preceding notion of the family and its “normalcy” is widely criticized in sociological circles, this family type was numerically dominant for the first six decades of the 20th century in Canada. 34 One cannot, however, attribute the dominance of the nuclear family to inherent features of modernity. Historical research has shown that the “normalcy” of the nuclear family was an extension of the “ideals” of “masculinity” and “femininity” from the middle to the working classes. During the Industrial Revolution, working class females were common in the labour force and factors such as the ideological shift towards appropriate gender roles and the struggle for a family wage for male wage earners hastened the rise of the nuclear family. 35

24 In the period following the Second World War, the nuclear family’s dominance was reinforced by social welfare policies. Research on the state and social policy in the postwar period shows that whether it is in the form of social housing or welfare entitlements, there was an institutional bias in favour of nuclear families. 36 This bias entered social housing programs in postwar St. John’s.

St. John’s on the eve of social housing and urban renewal

25 St. John’s was in the midst of a housing crisis in the 1940s, which developed from the aftermath of two significant fires (1846 and 1892) coupled with continual growth of the population and lack of proper management at both the municipal and provincial level (due in part to the Commission of Government discussed below). 37 St. John’s had a population of 44,603 in 1945, which reached 79,884 by 1966. 38 The majority of its population was derived from European settlers (mostly from England and Ireland) who arrived after the 16th century. 39 Manufacturing, army bases, and the service sector were significant employers in the city by 1945, which attracted people from outport communities reeling from the two world wars. 40 A gendered division was evident in the number of men who were employed versus women, the type of work that men and women did, and their weekly salaries. For example, while 11,361 men held wage employment in 1945 only 4,853 women were employed. Males were mostly working in service, transportation and communication, and manufacturing industries and earning on average a weekly salary of $26.56 per week, while women mainly worked in the service and trade sectors earning on average $13.38 a week. 41 The wage disparity can be explained by the social norms at the time, which dictated that women, if working at all, ideally worked after completion of schooling but before marriage and were more likely to work part-time. 42

26 The city center “slum area” mostly mirrored these working demographics, which reflects the diversity of the socio-economic status of its inhabitants. The “slum area” was predominantly working class Irish Catholic, but New Gower Street, which was the southern boundary of the area, also included a small percentage of the immigrants (Chinese and Syro-Lebanese) who resided in the city. 43

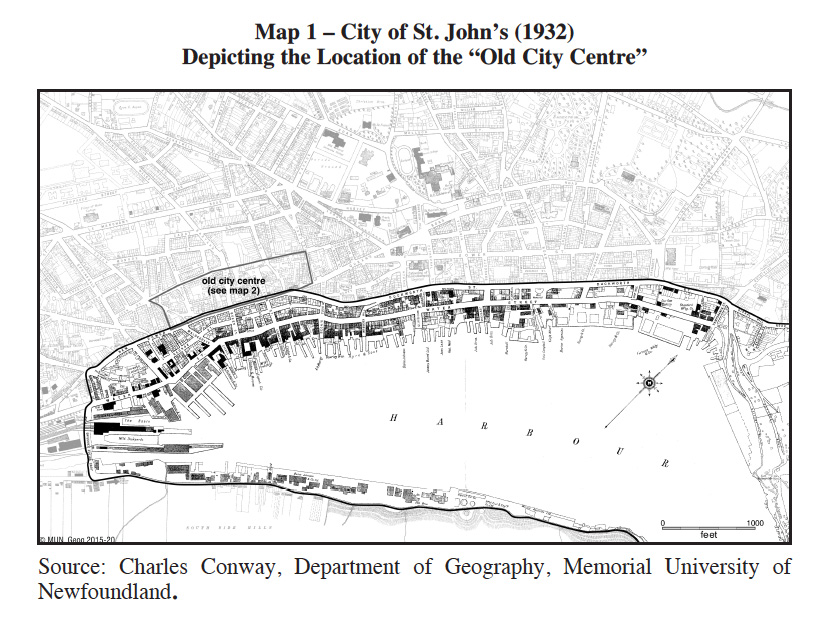

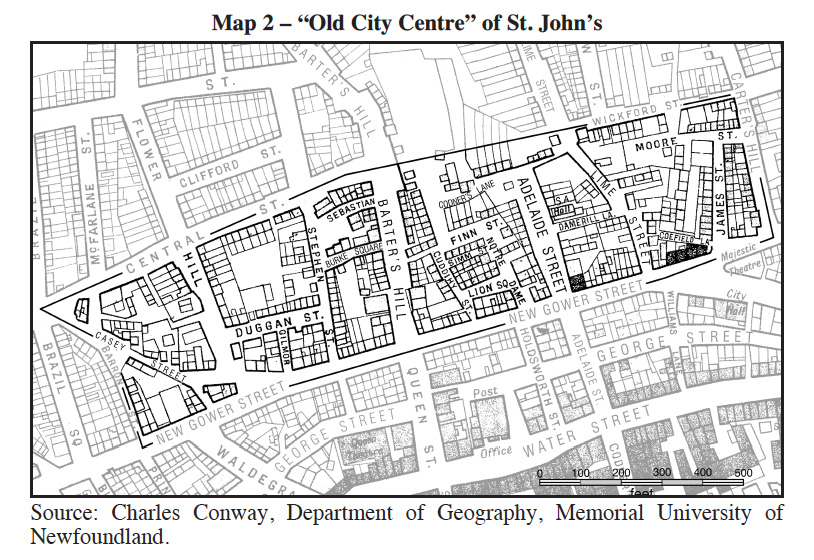

27 The “slums” north of New Gower Street drew the attention of St. John’s Municipal Council in the early 20th century (see Map 1 and Map 2). 44 In the early 1930s Newfoundland was in the midst of a financial crisis, and rule over the country reverted to Great Britain until it joined Canada in 1949. 45 While Newfoundland was under rule from Great Britain (the Commission of Government), St. John’s Council was offered a loan for new housing but the commission wanted financial jurisdiction until the loan was repaid. The municipal council refused this offer. In 1939, councillor John Meaney called upon the city and the commission to build homes. In 1942 Eric Cook, the deputy mayor, moved to have the newly elected council act on housing. A 13-member committee under the leadership of Justice Brian Dunfield (appointed by the Commission of Government) lead a Commission of Enquiry on Housing and Town Planning (CEHTP). Dunfield rapidly began to exercise control over the CEHTP. As we shall see, the CEHTP did not solve the “slum problem,” but prepared the groundwork for post-Confederation projects that did so. 46

Display large image of Figure 1

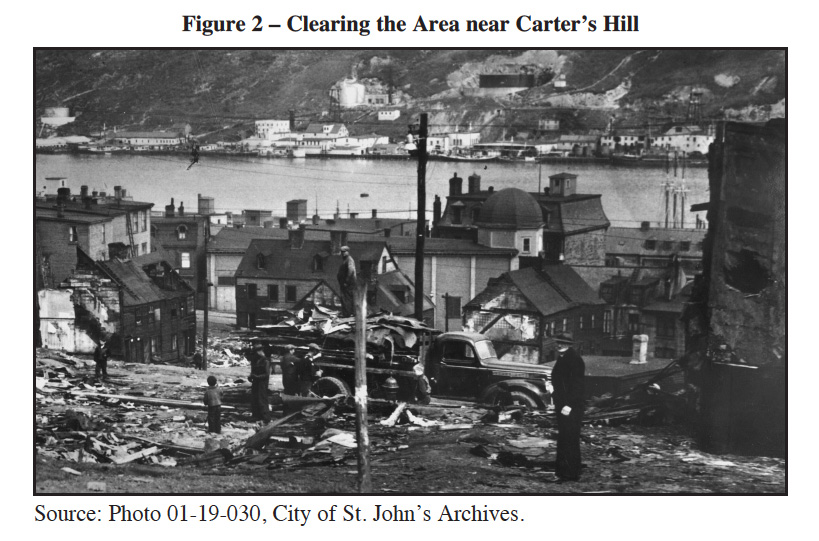

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

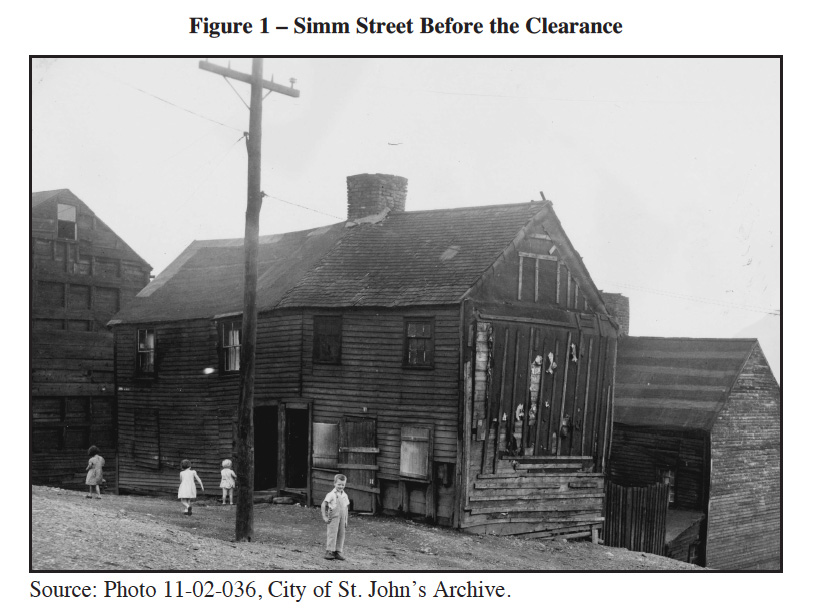

Display large image of Figure 328 CEHTP (1943) did a survey of 6,500 homes in St. John’s to assess the overall quality of homes, the desire for better housing, and the willingness to pay for such housing. It received 5,700 survey responses that covered 4,613 homes. While data were not provided by street name, a substantial portion of the dwellings (many of which were located in the city centre) needed to be replaced (1,000), were to be soon condemned (525), or were to be immediately condemned (225). 47 Most homes in the latter two categories lacked water or sewer facilities. Many city centre households collected water from public tanks. Wastewater was dumped into open drains that ran downhill and at night a horse-drawn wagon collected “night soil” that was then dumped into a collection tank at the top of Adelaide Street. 48

29 Following British and Canadian planners, CEHTP advocated market-based solutions. 49 CEHTP established the St. John’s Housing Corporation (SJHC) to build housing on land north of St. John’s. The objective was a “filtering up” process to relocate the “better off” in the city centre to new housing, and free up better housing in the city centre for those in more destitute conditions. The housing development known as Churchill Park became a middle class suburb. It was part of 800 acres of expropriated land that became the basis for housing developments after Newfoundland became a Canadian province in 1949. A total of twenty (four-bedroom) homes were built by 1947; the average price for each home was $11,300. 50 This was beyond the means of most homeowners in the city centre. In 1945, the average price for the 30 homes of residents located in the portion of the “central slum,” where the current City Hall is now located, was just over $3,000. 51

30 Prior to 1949, the only social housing development in St. John’s occurred on acquired property (Ebsary Estates) northwest of the city centre. This was co-financed by the Municipal Council and Commission of Government. This development was known as the “Widow’s Mansions” and consisted of seventeen properties with four apartments each; some from the “slum area” were rehoused there. 52

The St. John’s Housing Authority and social housing in St. John’s, 1950 to 1956

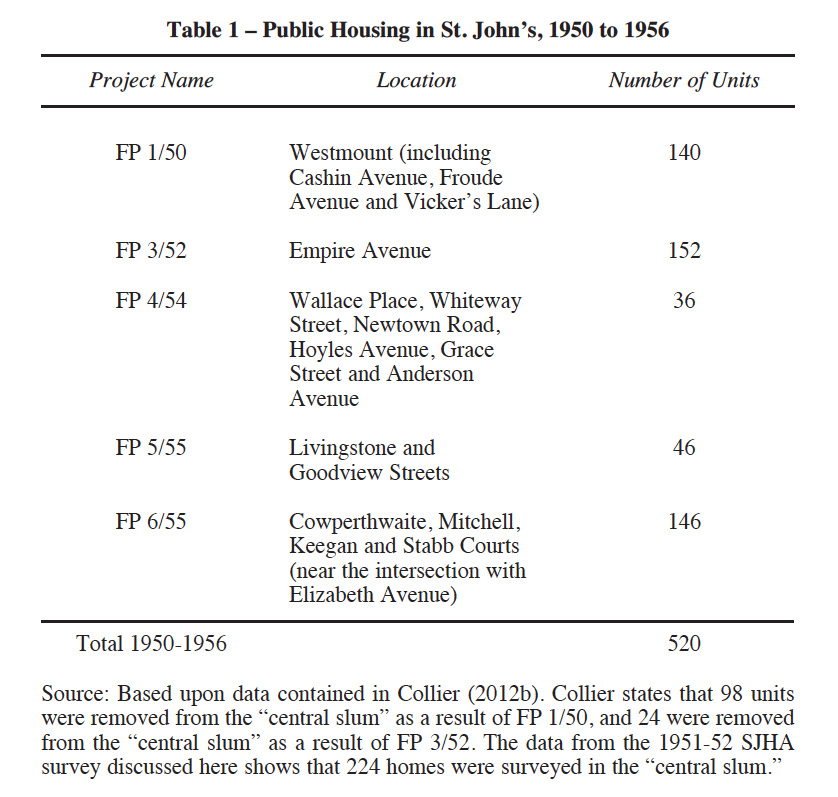

31 Confederation and the entry of the federal government into the housing market through CMHC ultimately solved the “problem” of the “central slum.” Under the auspices of the Section 35 of the NHA, the federal and provincial governments divided the costs associated with public housing: 75 per cent federal and 25 per cent provincial. 53 From 1950 to 1956, six federal-provincial (FP) projects were undertaken in St. John’s (see Table 1).

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 132 The city became one of the earliest and largest beneficiaries of this funding. The SJHC provided cleared and serviceable land that became the site of these FP projects. In addition, the St. John’s Housing Authority (SJHA) became the vehicle for selecting tenants for these FP projects. As we shall see, need was not the only factor in determining eligibility. In fact, SJHA looked for viable nuclear families in terms of economic ability to pay and good citizenship characteristics – attributes not characteristic of a substantial minority of “central slum” inhabitants

33 In order to find tenants for the FP projects, SJHA conducted a survey in 1951 and 1952 of 501 homes in the inner city of St. John’s. The SJHA survey included 260 families in 224 households that were relocated between 1951 and 1964. This constituted the “central slum” that authorities had deliberated over in previous decades. 54 Initially, the poorest slum dwellers were excluded from positive assessments. The “least eligible” for public housing were often left in the slum until the final clearance under the auspices of urban renewal in the 1960s. 55 Our preliminary findings show that stable working class renters and homeowners were favoured by SJHA. However, many homeowners remained in the area along with the poorest inhabitants until the City of St. John’s turned to the commercialization of the inner city.

34 In assessing the data from the 1951-1952 survey, we have to go beyond the simple classification of A, B, C, D, E, or F provided on the file folder for each family. 56 There were no definitions provided for any of these categories, but category “C” meant rejection. In addition, some file folders did not have the category “C” but were definite rejections based upon the comments within the file. A closer examination shows that some rejections (category “C”), especially for homeowners, were made after the family head revealed that they were either building a new home, moving, or wanting to stay in their current location. In addition, homeowners who received a “favourable” recommendation were not necessarily accepted or moved into public housing.

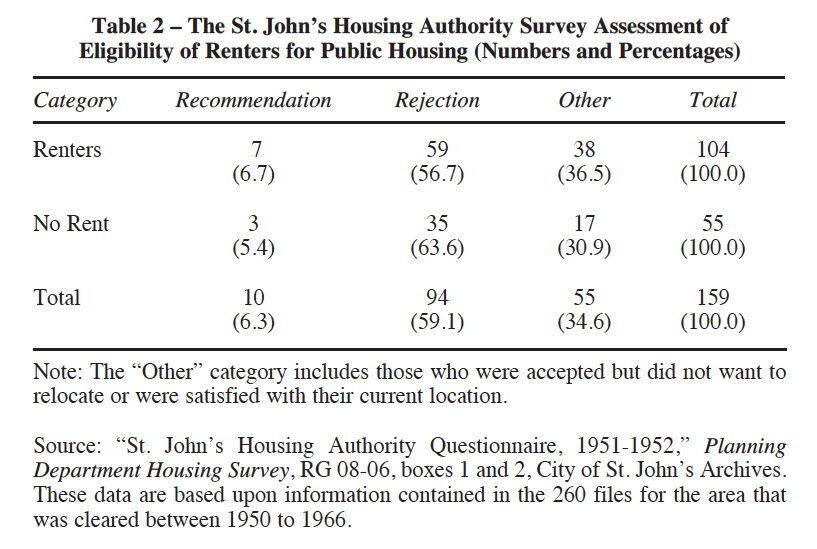

35 Table 2 shows the breakdown of eligibility for public housing for renters and those who paid no rent. In terms of the latter, several families were housed in dwellings owned by the City of St. John’s but who were not paying rent. In the cases of both renters and those who did not pay rent, the rejection rate was more than 50 per cent. Some of the reasons included the inability to pay rent in the new public housing, “poor citizens,” and being “on social welfare.” In many cases, these categories overlapped.

Display large image of Table 2Note: The “Other” category includes those who were accepted but did not want to relocate or were satisfied with their current

location.

Display large image of Table 2Note: The “Other” category includes those who were accepted but did not want to relocate or were satisfied with their current

location.

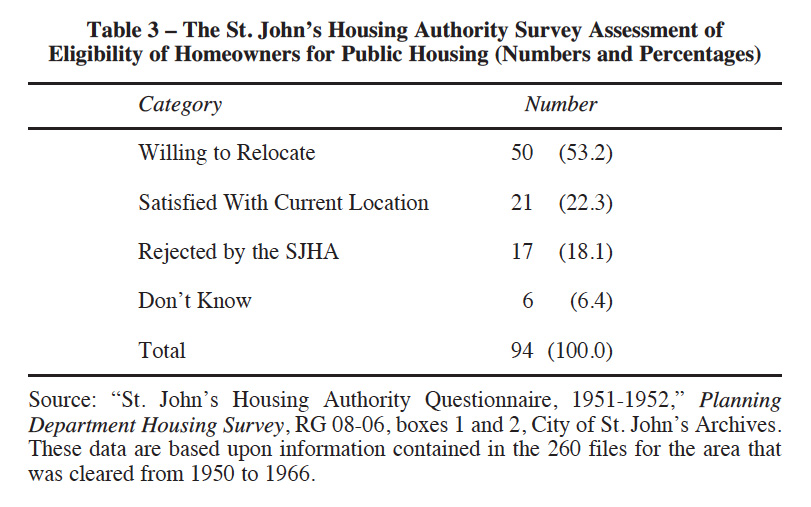

36 Given that there were more public housing units available than for the ten recommended (see Table 1), many in the “other category” must have eventually been accepted into public housing. While we do not have such figures, one thing that is clear is that the first comprehensive attempt to clear the “central slum” is based upon a social determination of eligibility. In addition to assessing those renting and not paying rent, SJHA also provided an evaluation of homeowners in the area. These data are summarized in Table 3. In this case, the rejection rate is only 18.1 per cent. In the majority of cases (53.2 per cent), homeowners were willing to relocate.

Display large image of Table 3

Display large image of Table 337 For many, the issue of “proper compensation” was critical to ensure the recouping of the value of the home – especially as many planned to buy elsewhere in the city. The statement “no renters” indicated that it was a homeowner being surveyed. Nevertheless, as we shall see, the provision of new public housing for homeowners was not part of the final decision by provincial authorities. A bias emerged in favour of “stable renters” or those who could still afford rents after the maximum rental supplement by the province.

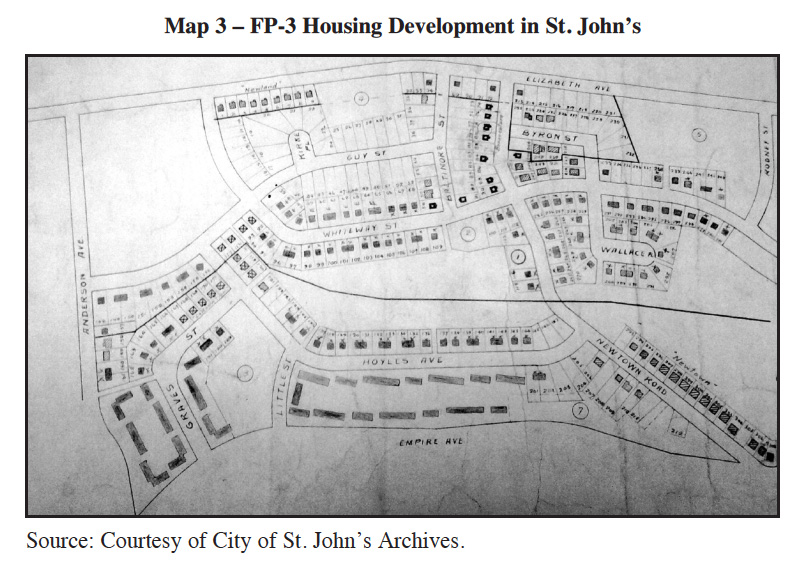

38 The 1951-1952 survey was in preparation for the 152 apartments in the Federal-Provincial (FP-3/52) project in the Anderson Avenue and Elizabeth Avenue area north of the city centre (see Map 3). This area was part of the “land assemblage” cleared to make way for the Churchill Park suburb in the late 1940s. 57 FP-3/52 was the second of five projects from 1950 to 1956. However, notes from the survey show that some were asked to consider one of the “few remaining apartments” in the Westmount (FP-1/50) area that surrounded the Ebsary Estates area. Ninety-eight houses in the city centre were taken down as part of the FP-1/50 project. Only 24 houses in the city centre were taken down in conjunction with FP–3/52. 58

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 439 Further for the 152 apartments in FP-3/52, only 85 of the total of 326 recommendations in the SJHA survey involved relocation to this area. Since only 24 homes were taken down in the city centre as a result of FP-3/52, at most only 27-28 families were relocated. 59 The remainder of the 152 dwellings went to other applicants from St. John’s. This would include 57 other people surveyed and recommended who lived outside of the city centre, and 67 people not surveyed. 60

40 Before we turn to qualitative assessments made by those who administered in the 1951-1952 survey, it is useful to turn to the thoughts of Stanley Pickett, the first city planning officer for St. John’s. Pickett hailed from the United Kingdom and was made responsible, in part, for planning the clearance of the “central slum.” 61

41 Pickett was not averse to “selecting” tenants for public housing based upon eligibility criteria. 62 However, he was perturbed with the fact that far too many tenants for the FP-3/52 housing development were selected from individuals outside of the 501 surveyed in the city centre (including 241 from outside of the “central slum”):

Pickett added that the City of St. John’s should have been the primary decision-maker when it came to allocating housing:

A copy of this letter was sent to Brian Dunfield, chair of the Town Planning Commission.

42 Provincial authorities may have influenced the SJHA. The Department of Municipal Affairs and Supply indicated that the provincial government could only provide so much rental assistance. Clarence Powell, deputy minister of Municipal Affairs and Supply, noted in 1954 that the SJHA received 1,200 applicants for 152 dwellings on Empire Avenue. These applications were most likely for the FP-4/54 project (see Table 1). While the intention in all of these FP projects was to remove individuals from the central area, this was not always possible as one had to be a tenant, and a large number of people in the central area owned their own homes. In addition, 62 applicants could not qualify on the basis of a needed income of at least $900/year. The economic rental was $55/month for these units, and the subsidy for all units was a maximum of $20/month. 64

43 Given this, it is not surprising that SJHA made use of eligibility criteria in assessing the inhabitants of the “central slum” for the FP-3/52 project (see Table 1). While all inhabitants of the “central slum” were eventually “cleared” by the early 1960s, these initial assessments are important in that the “housing chances” (to paraphrase Weber) of residents were not equal. 65 By the late 1950s, those who remained in the “central slum” were most likely homeowners and those on “social welfare.”

44 In addition to rehousing “stable renters,” SJHA was aware of the requirements for the housing units put up by federal and provincial authorities. SJHC was also a signatory to these agreements. Stable renters with incomes “not too high” were sought for dwellings that would not include subletting or the addition of commercial establishments. 66 The result meant FP projects (see Map 3) consisted of homes designed for individual families. The FP projects were located northwest, north, and northeast of the old “central slum.” These projects, once on the periphery of St. John’s, are now centrally located within a much larger city.

45 Good citizens, good housekeepers, stable renters, and family sizes not too small (i.e., usually no smaller than four individuals) or too big (i.e., usually no more than nine individuals) were prerequisites for an overall favourable evaluation. Often employers or neighbours of family members were sought out and asked to confirm the character of occupant, as mentioned in the quotations below. This seemed to be one of the measures used to gauge the quality of the “citizen.”

46 What needs to be kept in mind is that the SJHA survey was a proactive effort to see who would be eligible for new housing, as well as seeing who was willing to move. SJHA sought out potential applicants, and then decided who would be eligible if an application was made. Moreover, some of those rejected included “good citizens” who were homeowners deemed “not eligible” for new public housing. In the early 1950s these homeowners and those on social welfare proved to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. 67

47 In the following case, a homeowner who was favourably evaluated did not receive a recommendation for a new home:

Despite this favourable evaluation, the front of the questionnaire is marked with the comments “Owns House” and “Family too small.” There is a second file with the same address and name, with the survey of 1952. The file states “Mr. (Name) has no idea what he should do if the house is bought or demolished – [he is] not interested in an apartment.” In other words, the male owner of this residence did not want to rent.

48 The following homeowner also received a favourable evaluation, but was rejected. There were seven living in the household: a male homeowner, two sons, two daughters, a granddaughter and grandson. The file notes: “The family has been living here for a number of years in quite comfortable circumstances, but if they are forced to sell out, in the interest of the slum clearance, they hope to purchase elsewhere which would afford them the same comfort.”

49 In another home of six people, with a male employed by the municipal council, the survey stated “this house, situated at the top of [name of street] is in a fair state of repair, with water and sewage and other conveniences; the house is old, like the others in this locality, but it is looked after and could not be classed as a slum in the real sense.” This homeowner was not interested in relocating at the time of the survey. Regardless, the “notes” on the file folders for some homeowners indicated a category ‘C’ or rejection, likely due to an administrative decree that only renters were eligible for housing.

50 Some renters were declared “good citizens.” In reference to a home in one of the worst streets in the “central slum,” one surveyor noted:

This family of “good citizens” was given a favourable recommendation for public housing. This was the case for another family:

On the front of the survey for this family, it was written: “Family too Small.” There is a second file with the same address and name, with the St. John’s Municipal Council Housing Survey, 1952. The outside of the folder had “Not Interested” written on the front, and inside it is stated that the family is planning to move out in the spring.

51 Another family was rated highly, but could not afford to pay the rent in the new public housing units:

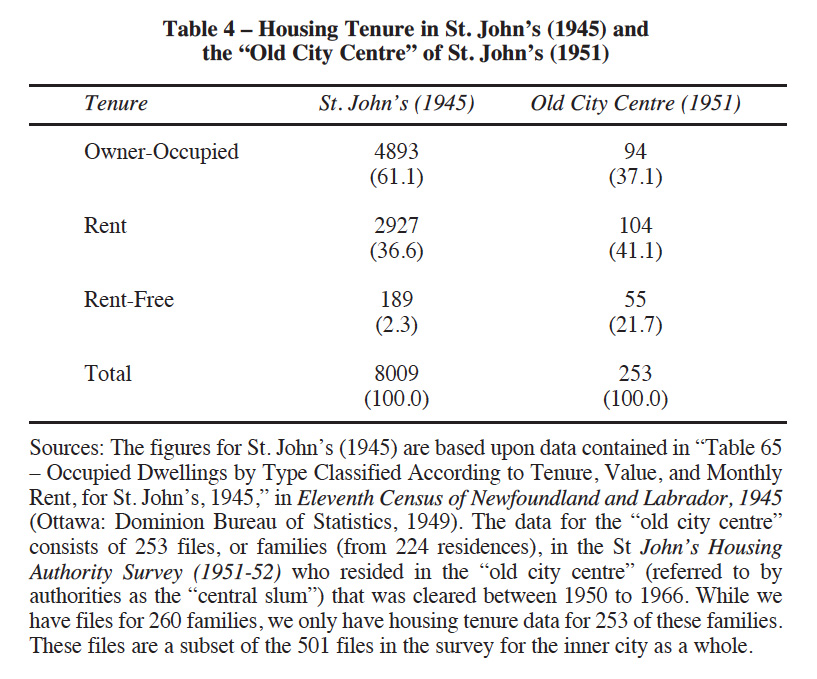

The front of the questionnaire is marked with “not interested, rent too high.” Table 4 shows that the “old city centre” contained a disproportionate percentage of those who lived “rent-free” in St. John’s. While the data for St. John’s, as a whole, are from the 1945 census, it is highly likely that not much changed by 1951 when the SJHA survey of the inner city was completed. As we can see from Table 4, while less than 3 per cent (2.3) of all tenancies were “rent-free” for St. John’s in 1945, over 20 per cent (21.7) of all tenancies in the “old city centre” were “rent-free” in 1951.

Display large image of Table 4

Display large image of Table 452 In contrast to “stable renters” and “homeowners,” many paying low rent (usually around $5 to $10/month) or no rent (living with a relative, on social welfare, or in homes owned by the municipality) received unfavourable evaluations. 69 The exclusion of low-income and no-income earners for the new housing projects shows how notions of citizenship (and their significance in meeting the eligibility criteria) were biased towards those who were not just economically stable; but the quotations below also indicate a bias toward abled bodied, healthy, and conforming to ideal family (and religious) doctrines (such as children born after marriage). Despite this, surveyors were sympathetic to the plight of some of these individuals. In this case of an “abandoned woman” living rent-free in her mother’s home, the surveyor notes:

On the front of the questionnaire, it is written: “Family too Small.” There is a second file (1952) with the same address and name. The report states “Mrs. (Name) husband deserted her some years ago, and contributes nothing toward the support of herself and son. The house is the property of Mrs. (Name) mother, with whom she lives.” A second letter from the St. John’s Housing Authority dated 25 October 1952 states in red: “CATEGORY ‘C’. REJECTED. THIS FAMILY AND INCOME IS TOO SMALL” (emphasis in the letter).

53 In the case of another family who was rejected, the surveyor also showed some sympathy:

In contrast to the two families above, the following family received no sympathy despite its hardship:

Finally, the following cases were rejected due to social welfare:

For the latter case, a second folder with the St. John’s Municipal Council City Planning Department Housing Survey dated 6 October 1952 contains a letter from the St. John’s Housing Authority dated 27 October, 1952, which states in red “CATEGORY ‘C’. REJECTED,” and in black “THIS IS EVIDENTLY A WELFARE CASE” (emphasis in the letter).

54 Welfare cases were largely made up of families unable to provide income, or a sufficient income to pay rent. They were usually single-parent families, multigenerational families, elderly individuals or couples, or contained family members who were disabled and/or ill. In some cases they were unrelated individuals renting out rooms, or just co-habiting. In many instances these overlapped.

55 The survey assessments outlined in this section provide an idea of what surveyors considered to be and not to be “good citizens.” Good citizens were those individuals who were pleasant, forthright with their employment and financial information, who were currently or soon-to-be employed, married with children, and owning a decent number of household “effects” such as furniture. On top of these, gendered notions of citizenship were also included. Men were judged on the state of the house repairs and how much they drank, while women were judged on the cleanliness of the home and their “social mindedness.” Thus “good citizenship” was a key criterion (at least during the survey) for obtaining a rental house or apartment.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5The arrival of urban renewal, 1960 to 1970

56 Our analysis shows that the functionalist argument that the nuclear family is a natural outgrowth of modernity requires scrutiny. In the “central slum” area of St. John’s, and perhaps in other “slum areas,” the doubling up of families was a common occurrence. As the data for the 1951-1952 survey of the inner city slum area shows, 16 percent of all households had more than one family with 260 families sharing 224 homes. Slum clearance was part and parcel of the social construction of the nuclear family required for modernity and “good citizenship.” In this case, the state played a key role in normalizing nuclear families via their criteria for the new housing developments that went hand-in-hand with the requirements of what became urban renewal. And, for this to happen, state authorities needed to evaluate, consolidate, and nurture good citizens. Modernity did not arrive in situ; it was manufactured out of plans, priorities, and temporary setbacks. The “slum” was cleared in a protracted and deliberate manner.

57 In the midst of the 1951-1952 SJHA survey, the city of St. John’s moved to ensure that the dwellings in the “central slum” did not receive any repairs beyond what was necessary to keep such dwellings “wind and airtight,” passing, in 1952, a by-law to that effect. 70 This proved important as many dwellings (including those condemned by the city in 1951 and 1952) remained until urban renewal funding arrived in the mid-1960s. The nature of the early clearance during the 1950s suggests that homeowners (ineligible but favourably evaluated) and those on meagre incomes, including social welfare, remained in the “central slum” until the final clearance.

58 The foregoing discussion shows the impact of social evaluation in determining eligibility for public housing in early postwar St. John’s. For some, this had the effect of devaluing their properties. A committee was formed in May 1964, which included the Progressive Conservative Member of the House of Assembly for the area, to secure better compensation for those whose properties were wanted by the city. In June 1964, the provincial Liberal government passed the city council’s “Central Area Redevelopment Act.” This act included wide powers of expropriation. In 1964, 130 properties (residential, commercial, and estate) were identified by city council for the purpose of being purchased. The regular and special minutes of city council from 1964 to 1966 provide data on 89 of these properties, 55 of which were residential. For residential properties, 40 homeowners accepted the offer from city council, and 15 were expropriated. These latter individuals “held out” for better compensation. All expropriations occurred after the “Central Area Redevelopment Act” received royal assent. In the meantime, city council in the 1960s prepared for the commercialization of the former “central slum.”

59 Prior to this commercialization, and later in tandem with it, new public housing developments took place in areas adjacent to the former “central slum.” These showed that the social housing projects during the 1950s had not been sufficient. While we do not have full information on where the remainder of those removed from the “central slum” from 1964-1966 ended up living, it is reasonable to assume that the 1965 public housing development of 210 units in Buckmaster’s Field north of the city centre (known locally as Buckmaster’s Circle) may have housed some former “central slum” inhabitants. Others may have relocated to social housing in a development in the northeast of the city centre. Finally, some may have moved into abandoned houses in the Gower Street area in the East End of the city.

60 The commercialization of the former “central slum” was only realized in the late 1980s as St. John’s positioned itself as the “oil capital” of the northwest Atlantic. At this time, land close to City Hall became the site of the Radisson Hotel in 1987 (now the Delta Hotel). This hotel was built on land acquired by Basil Dobbin (a local property developer) in 1980. One hundred and thirty homes were acquired in 1980 and demolished in 1982. These homes were adjacent to the land once occupied by the former “central slum.” After the Radisson Hotel was built, the former “central slum” area quickly became filled with commercial properties including the St. John’s Convention Centre and the Mile One Stadium. The City of St. John’s also used NHA funding for some low-income housing near City Hall, and for rent-geared-to-income housing in a complex west of the former “central slum.”

61 In the late 1960s, the Newfoundland and Labrador Housing Corporation (NLHC) absorbed the SJHC and centralized public housing decision-making. With the exception of some projects that the City of St. John’s developed in the city in the 1980s, public housing in the city was subsequently and is now directed by the NLHC.

62 In the fall of 2013, the City of St. John’s removed the inhabitants of several homes on the east side of Waldegrave Street (see Map 2) in order to prepare for the expansion of the St. John’s Convention Centre. While this street was not within the “central slum” discussed in this paper, it lay just south of this area. The inhabitants were on social welfare and represented the continuance of poverty in the city centre of St. John’s. The homes have now been removed and the St. John’s Convention Centre occupies the corner of New Gower Street and Waldegrave Street (down to Water Street). In the meantime, some of the poor in the city centre access a soup kitchen in the George Street United Church and a food bank on Cookstown Road. While “visible” in the former “central slum” of the inner city, the poor are in reality “invisible” amidst the wealth of a revived central city.

63 The urban poor may be invisible in the city centre, but are present in what were once working class suburbs north, northwest, and northeast of the former “central slum.” These former suburbs are the FP-1 to FP-6 projects of the 1950s. The former suburbs are in a more central location of a geographically dispersed St. John’s. In addition, the “oil money” that has poured into St. John’s since the 1980s has arguably contributed to escalating housing and rental prices in the city. This was confirmed by a provincial government official who, in an interview in 2011, declared “here on McFarlane Street (just north of the former “central slum”) a house sold for $99,000 – only worth $30,000 – [the buyers] valued the plot of land 20 feet wide. More and more of that happens . . . people are displaced – the price of housing – the landlord raises the rent for one room $250/month to $500/month. Apartments once $500 are now $800 to $900/month.” He added that since 2008 the market has “driven past” what people on social assistance can afford on the current government rental subsidy. 71 While the “central slum” is long gone, urban poverty and low-income housing needs remain.

Conclusion: reconsidering modernity and slum clearance

64 In their study of Oke-Foko, an inner-city slum in Ibadan, Nigeria, Grace Ogunyankin and Michelle Buckley place “slum” in quotation marks: “The term is often used from an outsider’s perspective and is a value-judgement on those living in areas designated as ‘slum.’ The outsider’s perspective often discounts the insider’s perspective and masks the experience and everyday reality of those living there.” 72 While 21st-century Oke-Foko is separated from the “central slum” of St. John’s in time and space, the image of the “slum” as one imposed by outsiders remains. From the early decades of the 20th century until its designation as the “central slum” in the 1940s, the inner city of St. John’s had the physical and assumed social characteristics of a slum. This is noted in the McGill architect John Bland’s consideration of the “central slum” as an area of juvenile delinquency, and in Steven High’s informants’ views of the place as having a “red light district.” 73 While some of the 51 former residents of the “central slum” and areas adjacent to the “slum” interviewed for a larger study of which this article is a part acknowledged some prostitution in the area, none referred to the area as a “red light district.” In fact, only two individuals, both from streets adjacent to the “slum,” referred to the place as a “slum.” The other 49 informants never used this term.

65 However, the “central slum” was used as a term by planning officials and that is what mattered in the relocation. While officials with SJHA showed some compassion towards those who were worse off in the “central slum,” this article demonstrates that their ultimate objective was to select out the most deserving from this area for relocation. “Good citizenship” was an important marker in early post-Confederation Newfoundland. It is not surprising that the use of good male workers and good female homemakers served as benchmarks for selecting potential housing applicants. This was, after all, the 1950s, and this period has become iconic for valourising the gendered division of labour that is reflected in the good citizenship criteria used by the SJHA.

66 This usage, though, shows that we need to consider two dimensions of “slum clearance” and “urban renewal” that are not usually connected in the literature. First, although the labelling of the “slum” in terms of its physical and social backwardness is widely cited in the literature, most research does not show how planning officials interrogated the moral character of “slum” inhabitants beyond a sweeping overview. 74 This survey by SJHA demonstrates that officials collected abundant information on the work life and day-to-day practices of “slum” inhabitants and used this to socially differentiate the “slum” population. The demarcation used is not that of “slum” dwellers versus other inhabitants in St. John’s; it is a demarcation that attempted to see to what extent some “slum” inhabitants had the social characteristics viewed laudable amongst those who lived outside of the “slum.” After all, those being relocated needed to “fit in.” Authorities during the postwar period were in the midst of making planning a “scientific discipline.” This could only be accomplished in a holistic consideration of the reordering of both architectural and social space, and that was a prelude to what happened in urban renewal studies. As Canadian cities launched such studies in the late 1950s as part of applications for more funding from CMHC, the documents that emerged were multidisciplinary considerations that collected knowledge on necessary street construction, housing design, and social backgrounds. 75

67 Second, we also need to reconsider the issue of “slum clearance” within the context of what constitutes modernity. The functionalist conception of modernity viewed the heterosexual nuclear family of male workers and female homemakers as part of a modern society. This research shows that in the case of slum clearance, modernity was part of a social accomplishment in the making. Modernity in housing did not occur due to the emergence of an industrial economy and urban living. Planners sought what they wanted, often from other places. While there is not room to digress on this point, the fact that British planners, or British-influenced planners, had an impact on the planning process needs some reconsideration. How did the distillation of ideas from across the Atlantic enter some Canadian cities and move on to other cities? In other words, how was modernity achieved in municipal settings? Finally, in the Newfoundland context, modernity was also embedded in projects such as fisheries, industrial development, and the resettlement of rural communities. 76

68 In conclusion, while being critical of the use of defined categories for rehousing individuals from the “central slum” we are not suggesting rehousing should not have occurred. As noted elsewhere, many of the residents of the former “central slum” needed to be relocated. 77 The existence of substandard housing without water and indoor plumbing is inadequate habitation for anyone in a modern western society. CMHC funding provided the new Newfoundland government with the necessary funding to deal with an issue that had been in existence for over 50 years. Our interview data, moreover, show that while there was a mixed reception to the new neighbourhoods to which former “central slum” residents relocated, many interviewees indicated that access to indoor plumbing and heating made lives more bearable for their mothers. They no longer had to bear the brunt of daily trips to the water tanks that existed in various locations of the “central slum.”

69 The problem is that not enough housing was provided for in the early stages of CMHC funding to deal with the residents of the “central slum.” In addition, the viability of the FP projects was contingent upon both demonstrated need and the ability to pay rent. As we have seen, this meant that housing officials, humane or otherwise, had to use social categories to determine who was eligible, and the ideals of good citizenship were put to use in the SJHA survey. While remaining residents of the “central slum” were resettled in the midst of urban renewal in the 1960s, the initial categorization favoured stable workers in nuclear families. By the 1960s, those on social welfare and homeowners seem to be amongst the last to leave the “central slum.”