Articles

Social Networks across Chignecto:

Applying Social Network Analysis to Acadie, Mi’kma’ki, and Nova Scotia, 1670-1751

This article examines the Acadian community of Beaubassin with a view to better understanding its social hierarchy and the relationships between colonists and their Mi’kmaq neighbours during the period up to 1751. Beaubassin has long been the least understood Acadian community, due in part to its distance from the colonial capital at Port Royal and also because its parish registers are not complete. However, social network analysis can provide new insights. The authors study families across generations, re-interpret a local witchcraft trial, and take a fresh look at the presence of Aboriginal peoples, determining that Beaubassin was a community of growing complexity and with stronger connections to the Mi’kmaq than previously understood.

Cette étude examine la communauté acadienne de Beaubassin en vue de mieux comprendre sa hiérarchie sociale et les relations entre les colons et leurs voisins mi’kmaq jusqu’en 1751. Depuis longtemps, Beaubassin est la communauté acadienne la moins connue à cause de sa distance de la capitale coloniale, Port-Royal, et parce que ses registres paroissiaux sont lacunaires. Une analyse des réseaux sociaux peut toutefois apporter un nouvel éclairage. Les auteurs étudient des familles sur plusieurs générations et jettent un regard neuf sur un procès pour sorcellerie et la présence des Amérindiens, pour constater que Beaubassin était une communauté de plus en plus complexe et que ses liens avec les Mi’kmaq étaient plus importants qu’on ne le croyait jusqu’ici.

1 LOCATED ON THE ISTHMUS OF CHIGNECTO, THE ACADIAN COMMUNITY of Beaubassin was built in the 1670s on the periphery of European influence in Mi’kma’ki. The village was established by two groups of colonists: one from Port Royal loosely organized by Jacques Bourgeois and the other from the Saint Lawrence Valley under the leadership of Michel Le Neuf La Vallière, who was granted a seigneury there in 1676. The initial settlement went well, and Beaubassin was soon recognized as a successful village specializing in livestock.1 A few families stood out for their success. By 1686, the Bourgeois were cultivating nearly 60 acres of land, operating a gristmill, and managing livestock herds numbering over 350 head. Others, however, such as Pierre Morin and Robert Cottard, were just getting by as farmhands. The Mi’kmaq remained a significant presence in Beaubassin, about one-fifth of the population enumerated there according to the Gargas census of 1686.2 Living within such proximity to Mi’kmaw individuals attracted missionaries to the area, who ended up serving both Indigenous and Acadian communities.

2 Life in Beaubassin was far from idyllic. Some of the colonists from Port Royal resented La Vallière’s attempts to impose seigneurial dues such as the corvée (obligatory labour) and successfully appealed their case to the royal court – Le Conseil souverain – at Quebec.3 One of the missionaries, Jean Baudoin, proved to be a controversial figure who argued with local inhabitants and colonial authorities. A series of English raids during the 1690s brought violence, pillage, and broken dykes that, along with adverse weather conditions, culminated in famine and disease.4 Jean Campagnard, a farm worker, was arrested and tried as a witch after the untimely death of two people, including the seigneur’s wife.5 Census data demonstrates that the population grew slowly, from 133 in 1686 to 218 in 1707, with a corresponding gradual expansion of farms.6 After the British conquest of Port Royal in 1710 and the subsequent Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, by which Acadie became the British colony of Nova Scotia, Beaubassin remained a contested, but still marginal, marchland. Few officials and soldiers ventured there, while the Mi’kmaq continued to fish, hunt, and trade.7

3 Only in 1750, with the construction of forts on both sides of the Isthmus of Chignecto, did Beaubassin briefly become central to imperial plans. The French and their Mi’kmaw and other Wabanaki allies destroyed the village in 1751 as a way to deny the community to the British and to force the inhabitants to cross over the nascent Nova Scotia border and settle the area around the new French fort at Beauséjour.8 Many of these Acadians would ultimately be deported four years later.

4 Although the French inhabitants of Beaubassin shared characteristics with their counterparts in other Acadian settlements such as Port Royal and Grand-Pré, their historical experience and way of life were distinct in several important ways. First, they were uniquely positioned by geography to trade and communicate with both Quebec and Louisbourg. Over the 1730s and 1740s, for example, thousands of head of livestock passed through Beaubassin and Baie Verte for Louisbourg every year. Although New England traders also visited Beaubassin, it remained largely within a French sphere of influence and was used as a staging area for French attacks into Nova Scotia during the 1740s.9 The community was also more diverse, founded on Mi’kmaw territory by a combination of Acadian and Canadian families, regularly visited by French fishermen and officials, and seemingly connected with the local Mi’kmaw community.10 In comparison with peninsular Nova Scotia, the Mi’kmaq themselves moved more freely through the region. This was, and continued to be, their territory.

5 For both the Mi’kmaq and Acadians, these conditions translated into substantial population growth after 1713. By the 1730s the Mi’kmaq enumerated by the French in the area around Beaubassin had increased sevenfold, and included new communities (at least new to European observers) at Shediac, Tatamagouche, Shubenacadie, and Antigonish.11 Similarly, there were approximately 1,000 French residents; new Acadian villages had been founded in Chipoudie, Menoudie, and Petitcodiac. In total, the population had doubled by 1740. While the Minas Basin emerged after 1713 as the fastest-growing Acadian community due to its abundant marshlands and river systems, Beaubassin was a close second.12

6 Historians of Acadie have used the relatively complete parish registers of Annapolis Royal and Grand-Pré to study demographic trends and social relationships in the colony. By using family reconstitution methods, Gisa Hynes demonstrated that the 295 couples who married in Port Royal between 1702 and 1730 had on average seven children. Infant mortality was low and four out of five marriages were complete, meaning that both parents lived throughout the childbearing years.13 In a more recent article looking at Acadie as a whole, Stephen White similarly emphasized “children came into the world very regularly every two years, and very few left it prematurely, because infant mortality was virtually negligible.”14

7 The demographic situation was quite different for the Mi’kmaq. Using Antoine Gaulin’s 1708 census – one of the few sources that sheds light on early-18th-century Mi’kma’ki – we can determine some general characteristics of Mi’kmaw demography.15 The census enumerates seven Mi’kmaw summer villages, including the community at Chignecto (Beaubassin). It demonstrates that Mi’kmaw household size tended to be smaller than their Acadian neighbours, with between four and six individuals per household depending on how widows and orphans are counted. The difference between Acadian and Mi’kmaw household size reflects the differences between the Acadians’ more agricultural subsistence practices and the Mi’kmaw fishing, gathering, and hunting economies.

8 When combined with warfare and the increased competition for resources brought about by European colonization, these factors led to lower Mi’kmaw life expectancy and rate of reproduction. Child-woman ratios, calculated from the census by comparing the number of children under five born to women between the ages of 15 and 49, suggest a substantial difference between the Mi’kmaw and Acadian population. This technique is ideal for the pre-industrial period. Under normal circumstances, the average interval between births is about 28 months. A married woman, then, will have at least one child within this time but only a handful will have none or two or more.16 At Beaubassin, for example, the ratio was 1.00, significantly higher than the Mi’kmaw living near Port Royal, while among the Acadians at Port Royal it ranged from between 1.09 to 1.14. Though Mi’kmaq reproduced at a lower rate than their Acadian neighbours, reproduction at Chignecto was higher than elsewhere in Mi’kma’ki. Attention to life expectancy, however, demonstrates that it was the more limiting factor. Fifty-six percent of the Mi’kmaw population in peninsular Mi’kma’ki (present-day Nova Scotia) was under 20 years of age (48 per cent at Chignecto), and just fewer than 20 per cent were widows and orphans (15 per cent at Beaubassin). This suggests that rather than focusing on childbirth, death and/or migration away from the community were relatively common experiences and – given the high percentage of widows – an experience that affected men more than women.17

9 While global demographic calculations are possible for Annapolis Royal and Grand-Pré, and the 1708 census provides some light on Mi’kmaw demographics, details of Beaubassin’s demographic history are clouded by poor source material. The parish registers, for example, have only partially survived as some of the years that are included in the register seem incomplete. There are only 13 baptisms recorded in 1717, for instance, and they all occurred in the month of June. This was clearly a case where the missionary was “catching up” after a long absence because most of the babies concerned had been born the year before. The missionary’s primary role was to serve the Mi’kmaq, and sometimes this meant that the residents of Beaubassin went without the support of a priest. There are also entire years missing, from 1724 to 1731 and again from 1736 through 1739. We simply do not have comprehensive parish data for Beaubassin.

10 To make matters worse, not all of the archival records were transcribed into published transcriptions of the registers. It appears that in compiling his first volume of Acadian Parish Records, Winston de Ville systematically excluded Indigenous individuals.18 The Archdiocese of Quebec archival records include 37 baptisms involving Indigenous people that were not recorded in his transcription. The section below on Acadian-Mi’kmaw social relationships would not have been possible without restoring these and other records to the data set.

11 To further complicate matters, Samantha Rompillon has observed that over 500 people recorded as living at one time in Beaubassin later moved somewhere else – a factor that we must also consider for the Mi’kmaq as well.19 Here we encounter a central challenge of traditional family reconstitution methods and a problem raised by numerous experts.20 This approach only captures sedentary families and thus provides a misleading portrait of the community, its socioeconomic hierarchy, and its social relationships – they appear more static and fixed than they actually were. Others have stressed that the primary source, the parish registers themselves, can be interpreted incorrectly. For example, Bertrand Desjardins has demonstrated that just because people married in a parish does not mean that they lived or moved there. In fact, about half of men and women in New France moved somewhere else after getting married.21

12 Family reconstitution methods are also nearly useless with regards to studying Indigenous populations, since their presence in the parish registers is sporadic at best. Furthermore, the historical record of official correspondences, censuses, and reports reflects the biases and experiences of an imperial elite, who – with a handful of exceptions – had only fleeting interaction with the region’s residents. The archaeological record has helped us expand our knowledge, particularly around the major Acadian settlements, but here too much of the data remains impressionistic rather than exhaustive. Complementary sources such as censuses, tax records, and notary documents can help us better understand and follow the life course of historical actors, but unfortunately few of these kinds of sources have survived for Acadie.22

13 A life course approach, by which experts closely examine common events such as marriage and having children across generations, has also been applied to early Quebec; the conclusion there was that instability and mobility characterized family life, with mortality and infertility acting on a significant minority of couples.23 A closer look at a group of sixteen young couples in Port Royal between 1671 and 1707 reveals a similar situation of instability and mortality. In fact, five of the sixteen male heads of household were dead by 1686, and eight of them by 1707. Six of the sixteen households left Port Royal during the same timeframe, four of them for Beaubassin.24 The census records for the end of the French regime suggest a contrast between consistent, steady economic development in Beaubassin and the pronounced setback and slow recovery at Port Royal after 1693. At the same time, the court documents related to the Jean Campagnard sorcery case in 1684 paint a compelling picture of a growing community running into significant obstacles such as insufficient harvests and diseases.

14 In sum, the trouble with further analysis of Beaubassin is that the censuses and parish registers are not complete and harbour a variety of institutional biases, such as an under-representation of child mortality, the transient labour force, and the resident Mi’kmaw population. Other sources are piecemeal or unavailable. How then can the historian further study the community of Beaubassin? Most historians of Acadie have chosen not to do so, but social network analysis provides one avenue to get beyond these problems and offers fresh insights from old sources. By creating a new database from the admittedly flawed parish registers, the data and visual representations of the community it presents illuminate the community in new ways.

15 Social network analysis is not a new method, dating back to the 1950s, but it has become more popular and also more powerful in recent years thanks to advances in technology. In other disciplines, particularly in the social sciences, the number of studies using SNA techniques is rapidly increasing, but few historians have adopted it and very few for the colonial period.25 Experts emphasize that it is not a panacea; rather, social network analysis can help identify people and relationships of importance in the community that might not otherwise emerge from traditional sources and methods such as family reconstitution. To effectively use this approach, we need to be specific as to what questions we are asking or, rather, what specific things we can know.26 Our social network analysis of the community of Beaubassin focuses on three questions. First, we investigate how social network analysis may shed new light on the evolution of the community of Beaubassin as a whole – from its first generation of colonists to the eve of the community’s destruction. Next, we take a microhistory approach with the Jean Campagnard sorcery case and a social network map of the 1680s. Finally, we wanted to know if social network analysis could be used to stitch together the incomplete and poorly documented parish registers to help us better understand the relationship between Acadians and Mi’kmaq on the Chignecto Isthmus.

16 Nearly 20 years ago, Charles Wetherell cautioned that the use of social network analysis by historians is “an inherently problematic enterprise” due to an incomplete historical record and imperfect understandings of past social relations.27 More recently, Thomas Peace has noted that social network analysis represents the past with its own biases and assumptions; notably, it is a mistake to assume that all relationships can be revealed and were known and significant for historical actors.28 With these cautions in mind, in using these case studies we hope that this article will both expand our understanding of pre-deportation Beaubassin and Chignecto as well as help us better recognize the advantages and pitfalls of using this method to interpret the past.

Evolution of a community

17 Robert Morrissey affirms that SNA is “about the network itself” – the structures and relationships of a community – with individuals only significant in light of the whole. The community he studied, Kaskaskia, had a population of about 300 in 1727.29 Around the same time, Beaubassin had grown to over three times that size, and it grew even faster in subsequent years until the village was destroyed in 1751. As it grew, so did the complexity of its social network. The size of population and its steady expansion poses challenges for interpreting a single social network graph. By dividing our database into blocks of approximately ten years, though, it is possible to not only work around the gaps in the parish registers but also visualize the evolution of Beaubassin over time. This approach also incorporates life course perspectives, since a single map for a period of 70 years would paint a false canvas in which historical actors who were not contemporaries would be measured against each other, and actors who were influential at one time may be nearly invisible when seen across multiple generations. A network, like a community, maintains Thierry Rentet, is “a living and evolving entity.”30

18 Further, in a database relying on baptisms and marriages as source data, it should be no surprise that individuals at the peak of their life course – that is, married with several children – would be the most connected. Of course, this “peak” period only lasts a decade or two and so the most central figures will change over time. This is an important reminder that SNA provides one visualization of relationships and influence, but with significant bias. Couples with fewer children, or couples in which one of the partners dies at an earlier age, are disadvantaged in these calculations. Similarly, individuals who only spent part of their life in Beaubassin, or whose life course peaks occurred during one of the gaps in the parish registers, may appear less influential than they actually were.

19 SNA alone cannot provide definitive conclusions, but it can help us visualize the community in new ways in order to identify clusters, peripheral groups, and key individuals acting as bonds or bridges. By staying at a macro level or “whole network,”31 SNA can retrace the evolution of a community and sometimes with surprising insights. Here, we use Cytoscape 3.3.0, an open source tool for network analysis32, to present an overall picture of pre-deportation Beaubassin.

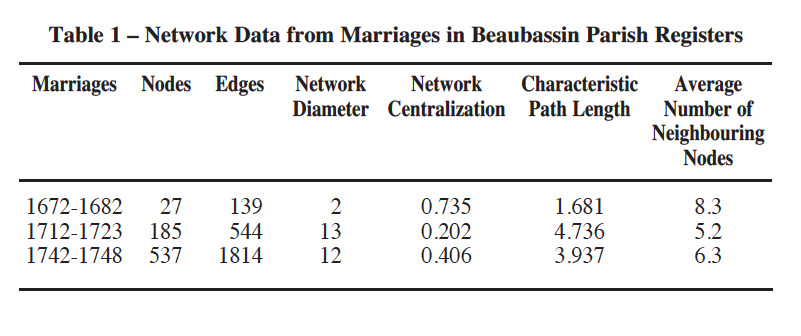

20 SNA breaks the data down into nodes and edges. Nodes are the number of actors (people), while edges are the number of connecting ties (relationships between people) in the graph. The diameter of a network can be defined as the greatest distance between any pair of nodes. Network centralization is an index that “measures the degree of dispersion of all node centrality scores in a network from the maximum centrality score.”33 The greater the dispersion of nodes with different levels of centrality to the network, the higher the score. In other words, it measures to what extent the network is defined by a few highly central actors with influence over a variety of low-centrality actors.34

21 Table 1 examines the community’s marriage records. At first, not surprisingly, there were relatively few nodes comprising a network with a small diameter, meaning that this group of first-generation settlers were also relatively close to each other with many neighbours and short paths (the number of edges) between them. We will identify and study these actors in more detail in the next section, but for our purposes here it is significant to note that Beaubassin went from a state of very high network centralization amongst its first generation to one of low centralization in the second generation after the British Conquest. This was not simply a question of population growth – such as there being more potential marriage partners and witnesses – because this trend is reversed by the 1740s. Despite approximately three times more nodes and edges, network centralization actually doubled between 1712-1723 and 1742-1748. Furthermore, there are other indications that the social hierarchy became more centralized or strengthened during the 1740s. For example, each node had more neighbours and a shorter path to each neighbour than in 1712-1723. Historical actors in 1740s Beaubassin, therefore, tended to have more numerous and closer ties than those of the 1710s.

22 This is a great example of the type of new question that SNA raises. Previous research has emphasized a dispersed settlement pattern in colonial Acadie.35 Although it is not surprising that the seigneur and a few founding heads of household were very influential in early Beaubassin, or that influence became more diffuse as the population expanded, we might not have guessed that the power and influence of the social hierarchy, at least with regard to marriages, grew during a time of rapid demographic increase and the proliferation of new nearby settlements in the third generation.

23 Visualized in this way, we can see how the community evolved – not only as a function of population growth, but through changes in social hierarchy and relationships. For example, many people made choices that reinforced the bonds between them. Such a result invites us to look more closely at the most significant actors in each time period and the clusters that surrounded them. What changed in Beaubassin between 1712-1723 and 1742-1748? Can we attribute this greater centralization to the renewed political tensions that emerged with the War of the Austrian Succession and the departure of some families for Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean? Or does it instead reflect other aspects of community development, such as the emergence of elites leveraging the expanding commercial opportunities brought about by Beaubassin’s growing role as a centre for the regional livestock trade?

24 Baptisms can be studied not only for population growth figures, but also to better understand social relationships between parents and godparents. At first glance, the graph for baptisms is overwhelming due to the sheer volume of nodes and edges. Once again, by breaking it into ten-year cohorts, we can chart change over time. This approach nuances the results in Table 1 with regard to social hierarchy in a number of ways. It is interesting to note that despite the significant population growth seen in the number of nodes and edges, the diameter of the network remained quite modest though certainly increasing. Even with 1,152 actors and 4,984 connections spread over several family villages and hamlets, 1740s Beaubassin was quite dense or close-knit from a social hierarchy perspective. Similarly, we see that nodes in 1740s Beaubassin were directly connected to more people and more closely connected to those people than those of the 1710s. The results for network centralization, however, differ from those we found for marriages. In general there is a steady downward trend, suggesting that the network was less and less centrally organized around a few influential actors.

25 How can we account for this? One possibility is that this is a function of source bias. With baptisms, the actors are either parents or godparents of the children. The same couple could get married only once, but could have multiple children and thus multiple choices of godparents. With regard to the 1740s, with a few hundred married couples as nodes, many with three or four children over the course of the decade, it should be no surprise that the resulting network is less centralized. In fact, both the 1717-1726 network and the 1740-1748 network represent a series of reasonably connected and equidistant nodes without dominant actors. On the one hand, this visualization may simply be less effective at showing the variations in influence of different families because of the nature of the source data. On the other hand, we should not be too quick to dismiss the significance of this finding. This visualization, for example, corresponds with the geographic dispersion of Acadian families in a series of small hamlets and villages. Furthermore, the network centralization trend also demonstrates that the choice of godparents was not focused on a few central actors – that is, the same people were not asked to be godparents for many children – so the graph has an increasing diameter as the population grew.

26 The importance of godparents has been little studied in colonial societies, but they provide a key element of the social network graph.36 Would we consider being a godparent a strong tie or a weak tie – a close bond within a cluster of actors or a bridge between different groups of actors?37 It could be both. In the context of early modern France and its colonies, the choice of godparent was quite important but the motivations were diverse. Some godparents were chosen from within the family or from close friends so that these individuals could help nurture and support the child. Other godparents were selected from elites including lords, state officials, community notables, and their wives. In these cases, the expectation was rather that the godparent would be a kind of patron and bring prestige to the family.38 Here again, SNA has provided an insight that would otherwise have been difficult to see. The results suggest that in early Beaubassin, families tended to adopt the second strategy, while subsequent generations were more likely to subscribe to the first.

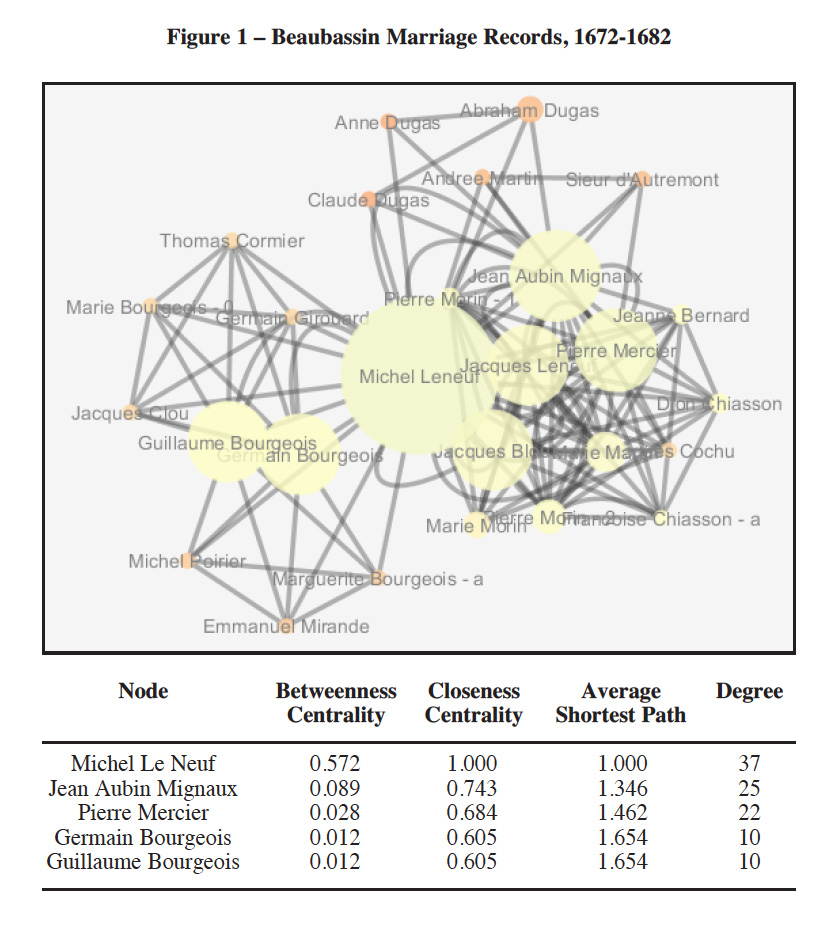

27 Each of these graphs, seen from a macro level, indicate that Beaubassin was a community that not only got bigger, but also saw a shift in how people interacted with each other. From a formative period dominated by a few families and the seigneur, to a second generation of more disparate expansion, to a third generation of rapid population growth but also retrenchment of social hierarchy, Beaubassin evolved as a function of the combined choices of individuals and families. The next section looks at SNA through an individually focused lens to complement this macro view.

Social hierarchy visualized through relationships

28 Many historians have affirmed that Acadian colonial society was more egalitarian than that found in New France or France. As this interpretation goes, the relative productivity of marshland agriculture, coupled with abundant natural resources and trade opportunities, as well as a desire to remain neutral from imperial entanglements, created an environment in which nearly all could flourish.39

29 Though popular, this conclusion is contested. Jacques Vanderlinden, in a study of marriages during the French period up to 1713, divided Acadian society into centre, periphery, and edges. Centres were composed mostly of the original colonists and their children, the edges consisted of those who did not fit in with the rest of the group – such as the accused witch Jean Campagnard – while peripheries represented newer arrivals who had some connection to the centre group, but could not yet rival them for influence in the social hierarchy.40 Gregory Kennedy suggests that Acadie during the French regime was typical of other French rural societies in having a social hierarchy led by a few elite and notable families (such as the seigneurs and state officials) as well as a centre group of prominent heads of household. These studies are supported by colonial census records, which clearly demonstrate that some families had much more land and livestock than others.41

30 We wanted to know if SNA could provide further insights into this social hierarchy and especially the role of particular individuals and families, not only for the French period but also beyond – right up to 1751. Visually, a SNA graph should correspond nicely with Vanderlinden’s notion of a centre, periphery, and edge. While it is true that parish registers cannot capture the entirety of human networks, such as economic and political relationships that would have been just as important in any community, the choice of marriage partners, of godparents, and of official witnesses can serve as a mechanism for evaluating influence and links between families. There was certainly some overlap between social-spiritual ties and economic-political ones and, in the absence of other historical documents, SNA offers a different way to interpret the sources.

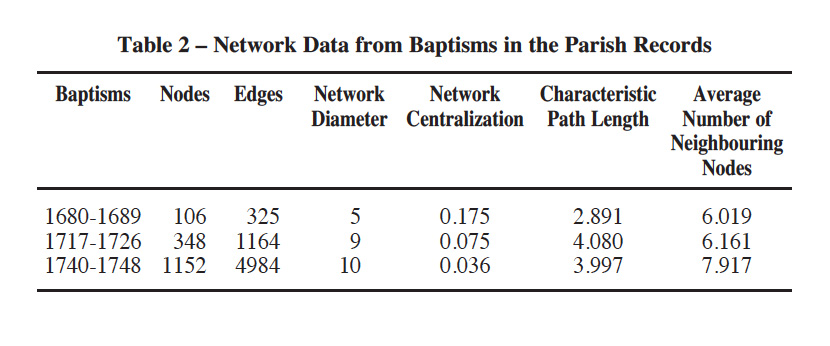

31 Figure 1 represents the Beaubassin marriage records of 1672 to 1682 and the top five, most-connected actors in the network. It is no surprise that the seigneur, Michel Le Neuf La Vallière, was an important actor. The graph demonstrates that he was by far the most central actor, serving as a hub for the group of Canadian colonists (e.g., Mignaux, Mercier) and also a bridge to the founding Acadian families (e.g., Bourgeois, Girouard).42 In short, both clusters of colonists sought relationships with the seigneur and his family. This is reflected in his very high betweenness centrality score, calculated by the number of shortest paths between all nodes that include the actor. Another way to put this is that it measures the amount of influence the actor exerts over the interactions of other nodes in the network. Closeness centrality, on the other hand, is a measure of the relative distance of one actor to all others in the network.43 The sheer number of La Vallière’s connections (degree) also suggests the power of his social influence in early Beaubassin. In this case SNA provides new evidence for the old debate over the importance of the seigneurs in Acadie, reinforcing the notion that at least for certain time periods they exerted considerable leadership.44

32 As we saw with the analysis of the community as a whole, the graph for baptisms is less centralized owing to the nature of the source in which multiple couples have influence simply by having children. An analysis of the top actors, however, reveals that the founding families were preferred as godparents. While the seigneur is not among the top actors, his wife is a top actor. In fact, four of the five top actors are women, and three of the actors are members of the Bourgeois clan from Port Royal. This group maintained properties in Beaubassin and Port Royal, and they were central figures in the trade with New England. If both clusters of colonists (Quebec and Port Royal) sought to connect to the formal prestige of the seigneur through marriage, it seems that the choice of godparents was guided rather by the pragmatic consideration of connecting to a family for economic benefits – particularly through godmothers. The baptism map also lends itself to Vanderlinden’s approach, with a dense cluster of centre families (Bourgeois, Poirier, Mirande, and Cormier), a variety of peripheral families with fewer ties (Mercier, Belou, Chiasson, and Girouard), and a handful of families on the edge (Massé, Gaudet, and Labarre).

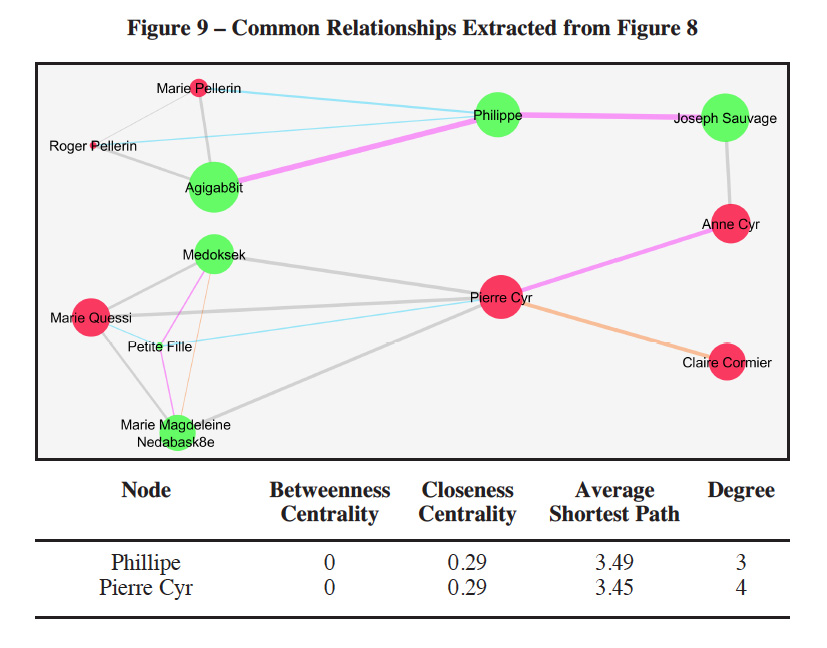

Display large image of Figure 3Note: Several nodes with higher betweenness centrality scores were excluded because they were central within tiny isolated

networks separate from the principal graph.

Display large image of Figure 3Note: Several nodes with higher betweenness centrality scores were excluded because they were central within tiny isolated

networks separate from the principal graph.

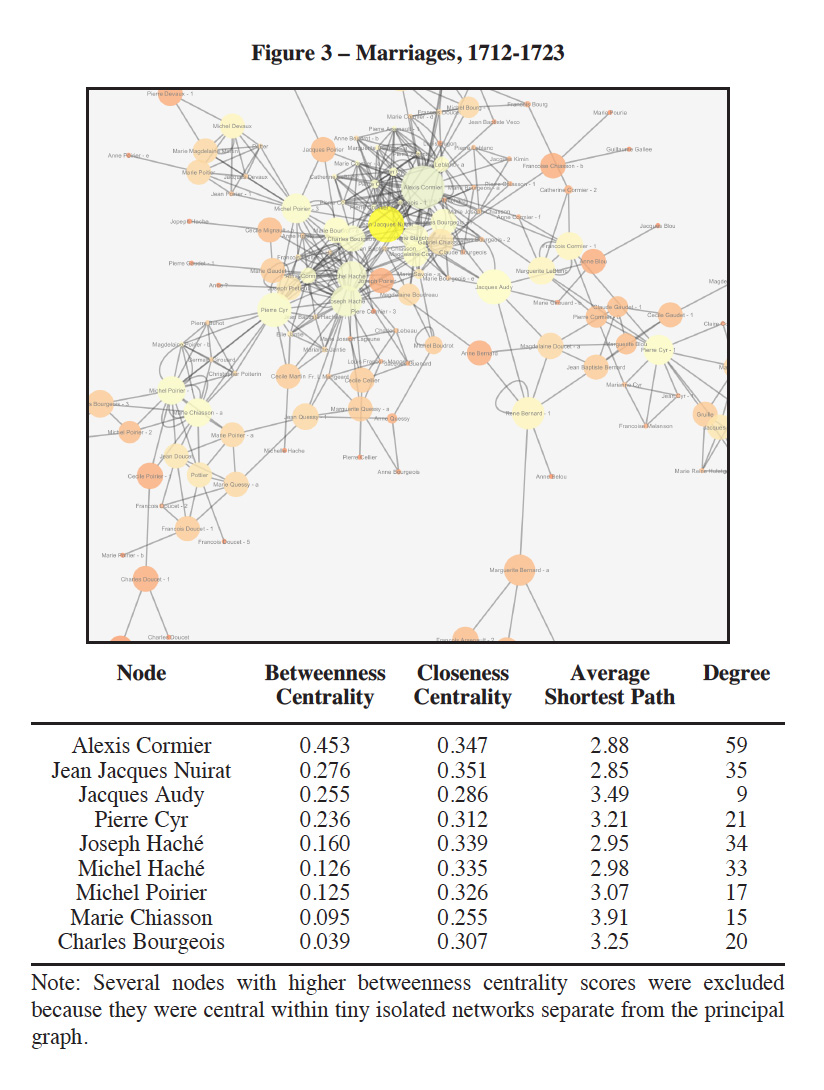

Display large image of Figure 4Note: Several nodes with higher betweenness centrality scores were excluded because they were central within tiny isolated

networks separate from the principal graph.

Display large image of Figure 4Note: Several nodes with higher betweenness centrality scores were excluded because they were central within tiny isolated

networks separate from the principal graph.

33 If SNA demonstrates that early Beaubassin was very much a “small world”45 in which people deliberately chose to make ties with key actors and to reinforce their position in the community through marriage and godparent choices, how did this change in subsequent generations as the population grew, and do the same families retain their influence?

34 Figure 3, which represents marriages in Beaubassin between 1712 and 1723, indicates a dense central cluster composed of families such as the Bourgeois, Cormier, Haché, and Poirier – several of the same founding centre families that we saw during the early period. The Hachés, who were not mentioned before, were among the original colonists brought by La Vallière from Quebec.

35 Perhaps even more interesting than this representation of the centre is the ability to visualize several distinct “bridge” actors connecting the centre to the periphery. These included Jacques Audy, Pierre Cyr, and Marie Chiasson. Viewed in SNA terms, the paradigm of centre, periphery, and edge persevered in the immediate aftermath of the British Conquest of Acadia. The La Vallière are notable by their absence – Michel Le Neuf had died in a shipwreck while returning to Acadie in 1705 – while the rest of his family moved back to Quebec thereafter. Other nodes filled the void.

36 Figure 4 demonstrates the complexity of the relationships during the 1740s. The central cluster seems to radiate around Charles Héon (the largest circle). Charles was born in Normandy and arrived at Beaubassin in the 1720s, marrying Anne Clemenseau in 1726. He remarried in 1748, this time to Marie-Jeanne Bourgeois. In 1757 he was among the refugee families who travelled to Quebec, where he died in 1758.46 He is identified as a blacksmith, but this does not explain how he was, by far, the most-connected person in 1740s Beaubassin, with 269 direct ties to other nodes. He had no obvious previous links to the community. The second most-connected individual with 113 ties, Pierre Derayer (the circle at “5:00” to Héon), only arrived in Beaubassin from France in 1743, and we know virtually nothing else about him except that he married Françoise Arsenault in 1745. The third most-connected person, Jean Damian, had only 48 ties, and the number quickly falls to 20 and below for the rest of the population.

37 Why were Héon and Derayer so often present as witnesses for marriages in Beaubassin? Other new arrivals from France were not so prominent. In fact, one in eight grooms in Beaubassin after 1710 were from France so new arrivals were not unusual. Were Héon and Derayer French officials, adding prestige by their presence to the ceremonies? Were they selected for important community posts, such as notary or delegate? Previous research into the Loudunais, where some of the original Acadian colonists came from, showed that each parish had a sacristan, whose duties included witnessing marriages. This would be the first time that this could be identified for colonial Acadie, although other residents in Port Royal and Grand-Pré have been identified as vestry managers (marguilliers).47 Does the map exaggerate the influence of Charles Héon and Pierre Derayer? What exactly was their role in the community? SNA has presented us with a puzzle that will require further research to solve.

38 As we saw in the previous section, the community of Beaubassin evolved from a highly centralized social hierarchy with the first generation, to a more disparate phase of expansion in the 1710s, followed by greater integration in the 1740s. The study of egocentric, or individually focused, networks and individual statistics suggest that Vanderlinden’s hypothesis about the enduring influence of centre families as well as the existence of isolated groups on the edge of colonial society is valid, but not without significant nuance and change over time. New arrivals from Quebec and France played significant roles in social hierarchy, especially around marriages, while a few centre families remained preferred as sources of godparents. Women were as important as men when it came to spiritual ties, and more research into godmothers in Acadie seems a promising lead. SNA has helped us identify a variety of individuals and families that may not be at the top of the list in Acadian genealogies, but nevertheless wielded considerable social influence during certain time periods.

The trial of Jean Campagnard: a microhistorical approach

39 The settlement of Beaubassin was no easy task. The sons of Jacques Bourgeois spent years travelling between Port Royal and Chignecto, building the dykes and supervising the desalination of the marshes before eventually settling there permanently with their wives and children in 1676.48 That same year, the governor of New France, Louis de Baude, Comte de Frontenac, awarded Michel Le Neuf de la Vallière the Chignecto seigneury. Both men were well aware of the presence of settlers like Bourgeois in the area; Vallière’s seigneurial grant expressly discouraged him from interfering with those who were “already established in the area,” which is likely what prompted him to arrive with a settler group of his own – two families, four bachelors, and his own household.49 This created four separate social groups in Beaubassin: the Mi’kmaq, who had lived on this land from time immemorial (Group1); the Bourgeois family, who arrived from Port Royal starting in 1671 (Group 2); other settlers from Port Royal who followed them (Group 3); and the Quebec group, who arrived with Le Neuf (Group 4).

40 The difficult conditions the latter three groups faced are demonstrated by the large number of adult deaths in the first few years, including heads of household and farmhands.50 One of the people who died, François Pellerin, had a long, lingering, feverish death that sparked the accusations that Jean Campagnard was a witch. A farmer with daughters and a very young son, Pellerin employed Campagnard as a farmhand first at Port Royal and then at Beaubassin following the family’s move there. On his deathbed, Pellerin accused Campagnard of bewitching him by blowing a mysterious substance into his eyes while they were out working in the fields in an attempt to usurp his place as head of the family.51 While this was the first of a string of accusations made against Campagnard when he was brought to trial in 1684, it is the only accusation leveled against him during the plague of 1678 that was characterized by the outbreak of a feverish disease that caused the deaths of several Beaubassin settlers.52 Why, when many people in the settlement were ill, was Pellerin the only one to suspect witchcraft as his cause of death? An analysis of the people involved with the other accusations and, in particular, mapping Campagnard’s relationships with all three settler groups, provides some interesting clues as to the motivations behind accusations of sorcery.

41 The death of a spouse created the necessity of finding a replacement, and this proved to be an early opportunity for the bachelors of Le Neuf’s group to integrate with the households from Port Royal. Pellerin’s widow Andrée Martin provides a case in point. Her children were too young to take over the farm. She needed help. Pierre Mercier, who had been engaged to one of Pellerin’s daughters, decided to instead marry his widow, gaining a farm that was already in production. Other Acadians made similar decisions. Examples include Jean-Aubin Mignaux marrying Anne Dugas, the widow of Charles Bourgeois, and Emmanuel Mirande marrying Marguerite Bourgeois, another widow with small children.53 Not everyone, however, so easily found a spouse. Jean Campagnard was frustrated, first when Pellerin reneged on an apparent promise to marry him to one of his daughters, and later when Roger Quessy and Françoise Poirier refused Campagnard’s request to marry one of their daughters. Numerous depositions suggest this as motive for Campagnard’s sorcery, not only causing Pellerin’s death but also sickening Quessy’s cattle. Marie Martin further suggested that Campagnard was enraged when the seigneur’s wife refused his sexual advances.54 For some reason, Campagnard had developed an unhealthy reputation in the community.

42 The building up of these sorts of tensions was common in witchcraft cases. Suspected witches might face community censor for years before formal charges were laid. In early Montreal, for example, when Anne Lamarque was charged with sorcery in 1682, the accusations went back almost ten years.55 While the allegations began with Pellerin’s death, Campagnard was only formally accused of sorcery in 1684 after the death of the seigneur’s wife. Marie Martin testified that he poisoned her with ensorcelled butter, while Marie Godet claimed that Campagnard administered the poison with a prick to the neck. In both cases, Michel Le Neuf acted quickly, arresting and imprisoning Campagnard and calling for witnesses from the community.56 Many swiftly reported their own sufferings supposedly at Campagnard’s hands. Before the 1678 accusation of Campagnard, it is unclear how socially popular or unpopular he was. He was hired labour and a relative newcomer to Port Royal society, having arrived in Port Royal in 1673; but the depositions mention other contemporary hired hands in Beaubassin who escaped Campagnard’s fate as well as an entire village worth of newcomers who arrived with LeNeuf. According to the testimony of the other villagers, his status as an outcast solidified with the accusations of witchcraft.

43 Roger Quessy’s testimony included an accusation that Campagnard had used witchcraft to sicken another farmhand, Pierre Godin, while he was sleeping. Godin confirmed the story and both men noted that Campagnard only removed the curse after he was threatened.57 Quessy then explained that when Campagnard sought his daughter in marriage he was reluctant to refuse outright as “he was aware of his bad reputation,” and was afraid of what he would do in retaliation. Instead, he said he would have to wait to consult with his wife. When Campagnard returned to hear the inevitable “No,” he told the family they would regret their decision eight days from hence. Exactly eight days after their encounter, a number of their cattle fell ill and nothing could cure them. As they suspected witchcraft was the cause, they asked the priest to bless their hay but to no effect. Finally, they asked the seigneur to deal with Campagnard. Le Neuf did not arrest the suspected witch at that point, but he did threaten to “run his sword through him” if he did not undo the spell. The cattle were well again within a day.58 Meanwhile, Jean-Aubin Mignaux accused Campagnard of casting an incantation on his crops to cause a poor harvest. Campagard responded that if Mignaux had a bad harvest it was his own fault for having farmed it badly.59 It seems no coincidence that Mignaux was one of the bachelors who married into the community.

44 To apply Vanderlinden’s concept of centre, periphery, and edge groups of families in Beaubassin, the centre group was clearly the Bourgeois clan and their immediate connections including the Dumas, the Girouard, and the Belliveau families. Unlike many of the Beaubassin colonists, they were numerous enough to avoid needing to hire outside labour to develop their properties. During this initial phase of settlement, they chose godparents and marriage partners chiefly from within their core group.

45 Sometime after 1676 new families began to arrive, creating a distinct periphery. Thomas Cormier, whose father had moved from La Rochelle to Cape Breton with Nicolas Denys in the 1630s before eventually establishing his family in Port Royal, arrived in Beaubassin by 1682. A carpenter by trade, the 1671 census indicated that at Port Royal he owned only 6 arpents of cleared land, 7 head of cattle, and 7 sheep. After the move to Beaubassin, however, the 1686 census showed that the Cormier family increased their fortunes enormously to include 40 arpents, 30 head of cattle, 10 sheep, and 15 pigs.60 Members of the Le Neuf family, and in one case, a mariner with no permanent ties to the community, stood as godparents to his children when they were baptized together in Beaubassin. The Quessy family arrived around the same time as the Cormier family. Roger Quessy had himself been a hired hand in Port Royal, and did not own any land there. In Beaubassin, however, the 1686 census reveals that he owned 8 arpents of cleared land, 18 head of cattle, 6 sheep and 8 pigs. The parish registers suggest, however, that there were few links between this family and the other colonists.61 Another example of this periphery group was François Pellerin and Andrée Martin who, as we have seen, married Pierre Mercier after Pellerin’s death. Owners of a single sheep and one arpent of cleared land in Port Royal in 1671, the Mercier-Martin household in Beaubassin included a large farm of 40 arpents in 1686. Mercier’s children by Martin all received members of the seigneurial family as godparents with one exception. The youngest Mercier child had Marguerite Bourgeois as a godparent.

46 The principal witnesses against Campagnard were all members of this peripheral group, with closer ties to the seigneur then to the Bourgeois clan. Since Michel Le Neuf, angered by the death of his wife, was the authority who accused and imprisoned Campagnard, it should come as no surprise that he would seek evidence from those who he or his family members had sponsored and supported. The Bourgeois clan is noticeably absent from the proceedings. Germain Bourgeois gave the only deposition from this family, and his statement is of a decidedly different character than the others. Identified as a witness to François Pellerin’s death, Bourgeois admitted he overheard Pellerin accuse Campagnard of witchcraft but then added “The man was obviously delirious with fever. I did not take the accusation seriously.”62 This is the only expression of skepticism to be found across 14 depositions. Why was Germain Bourgeois the only individual who expressed skepticism, while the families on the periphery were lining up to pronounce against the supposed sorcerer?

47 A clue lies in the nature of labour and settlement at Beaubassin. Farming the marshlands around the Bay of Fundy required extensive work to construct dykes (called levées in Acadie) and canals as well as the famous aboiteaux – the box and clapet at the base of the dykes that allowed rainwater to drain out while preventing tidal water from coming back in.63 Once the dykes were in place, it took years for drainage and desalination and there was a constant need for upkeep and repair. By 1680 the Bourgeois clan, who were able to sojourn from Port Royal during the 1670s, had built several productive farms. The more recent arrivals, on the other hand, were bachelors or young families just starting out, relying heavily on hired hands like Jean Campagnard and Pierre Godin.

48 Our alleged sorcerer had arrived in Acadie from France in 1670 alongside the new governor Hector d’Andigné de Grandfontaine. He had been recruited for the colony because of his experience working on dyked farms in Poitou and soon found work at Port Royal, later moving to Beaubassin. His skillset was in demand, so much so that even the seigneur, Michel Le Neuf, hired him to help establish his estate once the court ruled that he could not impose the corvée on the colonists.64 Jean Renaud, another hired hand who had known Campagnard at Port Royal, later testified that the accused was a reliable and skilled labourer.65 When Campagnard was interrogated in Quebec, as the case took on more gravity, he stated that the seigneur owed him over 700 livres in wages and claimed that this was the true motivation behind the accusations of witchcraft.66 Indeed, the seigneur had imprisoned him for nine months before his case was transferred to Quebec.

49 Was this trial really just a dispute over money? It seems that several households owed Campagnard wages for work he had completed as a farmhand, although we lack the records to know the details. He does seem to have been able to establish himself as a farmer in his own right; one deposition cites the lord’s wife attempting to buy hay from him, while the Mignaux deposition accusing Campagnard of cursing his crops suggests an attack by a competitor and rival.67 Perhaps some of the inhabitants resented his success. The 1686 census records over 400 arpents of cleared, drained farmland at Beaubassin, and another possibility is that his services as an expert in dykes were no longer needed. In addition to the seigneur’s personal motives and Le Neuf’s possible role in mobilizing testimony from those families to whom he was connected, there were plenty of reasons for the families on the periphery in Beaubassin to despise Campagnard. Many owed him money, others feared his rise as a competitor, and some had rebuffed him as a potential suitor for their daughters. Whether the product of superstitious belief or pragmatism or some combination of the two, many of the inhabitants of Beaubassin determined that they wanted to be rid of him and decided to pursue charges of sorcery to do it. The conseil souverain at Quebec recognized this. Although they found him not guilty, he was ordered to never return to Beaubassin.68

50 The SNA map of 1680s Beaubassin described above provides new insight into the Campagnard case by localizing the witnesses amongst those on the periphery of the community with close links to the seigneur Michel Le Neuf. The absence of the central Bourgeois clan reveals much about the nature of social hierarchy and the labour economy on the frontier in Acadie. Campagnard had hoped to integrate into the community in the same way as the bachelors Le Neuf brought from Quebec. Unfortunately, for reasons that will probably never be fully understood, he was marked as dangerous and undesirable soon after moving to Beaubassin. What we can say is that this trial demonstrates a deliberate and rather drastic strategy by a specific sub-group of Beaubassin society to remove someone they saw as a threat. Social networks mattered in late-17th-century Beaubassin.

Social network analysis and Mi’kmaw-Acadian relations

51 The razing of Beaubassin in 1751 reveals much about the cross-cultural world that developed on the Isthmus of Chignecto over the late 17th and early 18th centuries, as well as the considerable imperial investment that arose out of the War of the Austrian Succession. As British troops under Charles Lawrence arrived to entrench their position, Mi’kmaq associated with the French missionary Abbé LeLoutre set fire to the village, reducing it to cinders and ash. This forced the residents to flee closer to new French fortifications north of the banks of the Missiguash River. In a few moments, the work of several generations had been destroyed.

52 What do we make of Mi’kmaq destroying an Acadian village? Lawrence regarded this as proof of Acadian disloyalty and blamed the French. Louis de la Corne, the ranking French officer in the region, claimed that “si les Sauvages ont mis le feu à Beaubassin ce n’étoit pas par mon ordre et qu’il avoit tort d’avoir cette pensée . . . .”69 According to Charles Lawrence, the British official who met with the French officer, La Corne also added that the Mi’kmaq “claimed it [Beaubassin] as their own.”70 While certainly serving France’s broader military goals, France’s distancing iteself from Mi’kmaw actions was a rhetorical tactic commonly used during the 17th and 18th centuries to acknowledge Indigenous autonomy and territorial sovereignty in the face of competing English claims.71 Following in this tradition, La Corne acknowledged that this space was not merely Beaubassin; for the Mi’kmaq themselves, it remained Chignecto – a region connecting the Mi’kmaw districts of Sikniktewaq and Piktuk aqq Epekwitk. And so, despite it being an increasingly militarized space with a European population of over 2,500 Acadian settlers, the indigeneity of this space remained.

53 A problem with historical interpretation arises, however, given the asymmetries of the colonial record. Despite Mi’kmaq making somewhat frequent statements of autonomy and sovereignty, their relative absence from European colonial sources has resulted in a historiographical silence.72 The parish registers for Notre Dame du Bon Secours at Beaubassin help to develop our understanding of this early period of French-Mi’kmaw interaction. Although there are large chronological gaps – the registers cover only the early 1680s and 1730s as well as most of the 1710s and 1740s – the relationships they reveal are important and reinforce the image of this community seen in Gargas’s census. Between 1680 and 1686, 37 baptisms involving 57 Mi’kmaw and 39 French participants are recorded in the registers; in the 1720s another five baptisms were recorded involving 17 Mi’kmaw and 14 French participants.

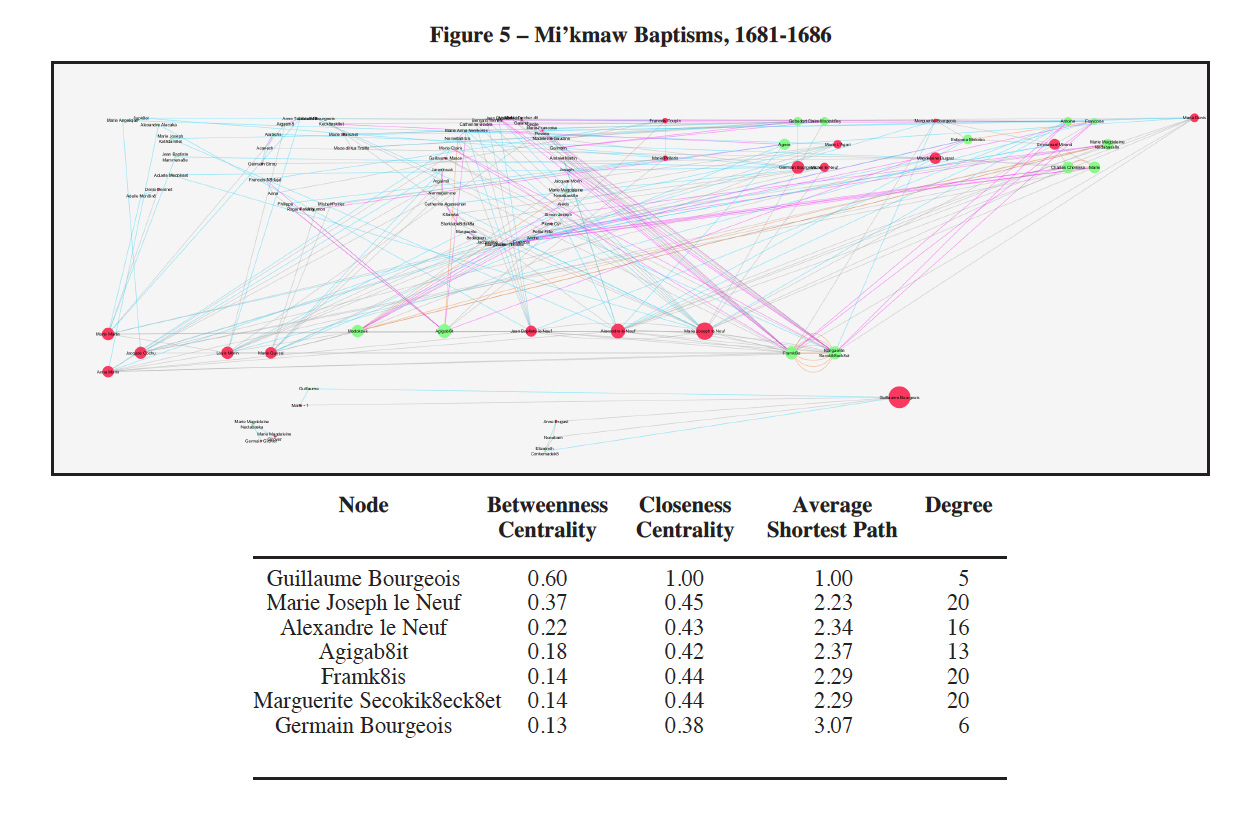

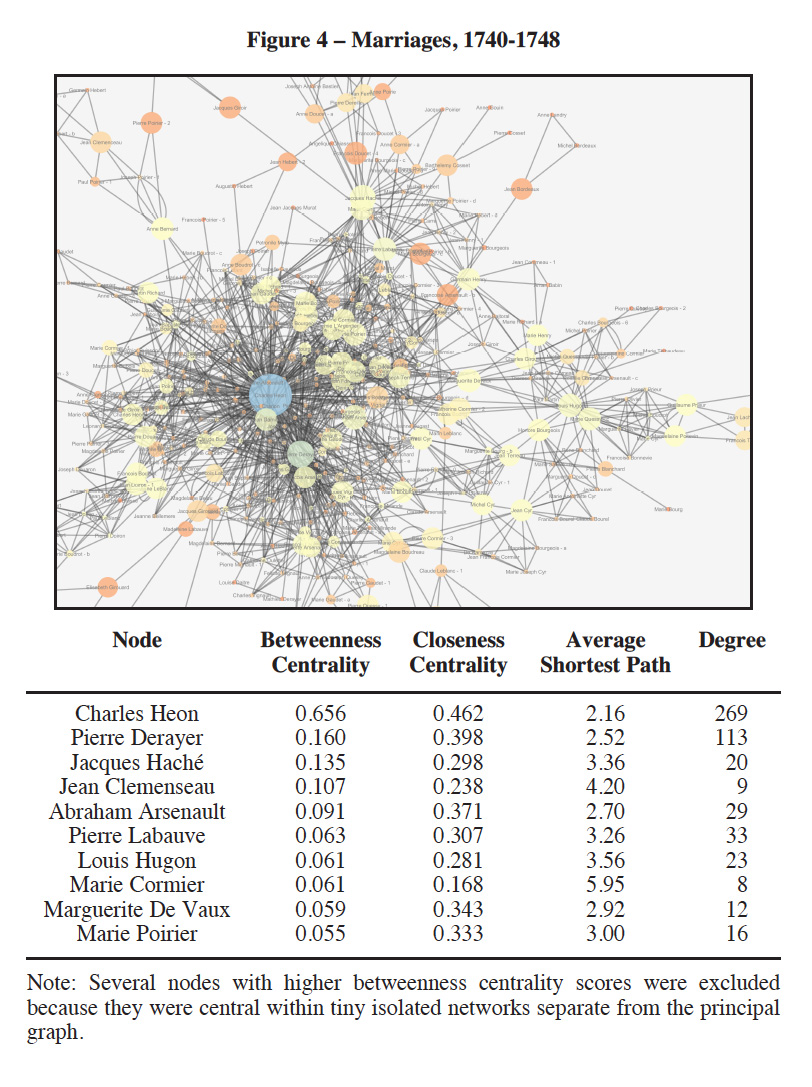

54 These records can be represented visually. Figure 5 depicts the records from the 1680s. The lighter (green) nodes represent Mi’kmaw individuals while the darker (red) represent the French, and the edges reflect the relationship between individuals as described by the parish registers: purple for parents, orange for spouses, blue for godparents, and grey for sharing in the act together (all of these colours are visible in the online version of this article). The size of each node reflects its “betweenness centrality,” or the likelihood you would need to pass through it on a path between any two nodes. Larger nodes, then, play a more central role in the network.

55 Here, much like in the broader analysis of the community as a whole, the two founding families of the Acadian settlement appear as the most connected part of this network. Guillaume Bourgeois, son of Jacques, had the highest betweenness centrality, followed by Michel Le Neuf’s daughter and son (Marie-Joseph and Alexandre). Almost universally, these people served as godparents in Mi’kmaw baptisms, perhaps signifying that these centre families controlled the region’s fur trade. This analysis, though, is somewhat misleading as Guillaume Bourgeois was only connected to five people and is not part of the larger network. The Le Neufs, however, were deeply embedded within a much more interconnected network, reinforcing our earlier conclusion about seigneurial influence at this time and the family’s deep ties to the fur trading Denys family.73

56 This visualization also reveals something more significant. The next three pivotal people in the network were Agigab8it, Framk8is, and Marguerite Secokik8eck8et.74 These people were the heads of two prominent Mi’kmaw families. Agigab8it represented one family (his partner, Neme8a8rbis, does not often appear in the registers and therefore is not represented in the same way as Framk8is and Secokik8eck8et) and Framk8is/Secokik8eck8et represented the other. As heads of families, many of their relationships reflected those they had with their children. Taken together, baptisms involving members of these two families comprised nearly one-third of all the baptisms included in these early parish registers and they are the only families who appear in the record for more than one year. This suggests that these families were unusual. Given that the Gargas census only listed 21 Mi’kmaq living at Beaubassin at this time, it seems reasonable to suggest that his census reflected the presence of these two families living on a more regular basis near the burgeoning Acadian settlement.

57 The fur trade was the most important link connecting these Mi’kmaw families with the French and, for the most part, it is safe to conclude that this social network suggests a broader pattern of trade. Le Neuf had begun trading in the region as early as 1670.75 By the 1680s, the region had become an important node in the coastal trade. Nineteenth-century historians such as Rameau Saint-Père referred to this place as “un établissement demi-commercial et demi-agricole.”76 Reflecting on his 1685 visit to the region, Jacques de Meulles noted that each April an English ship came to the community trading necessary supplies for furs acquired from the Mi’kmaq.77

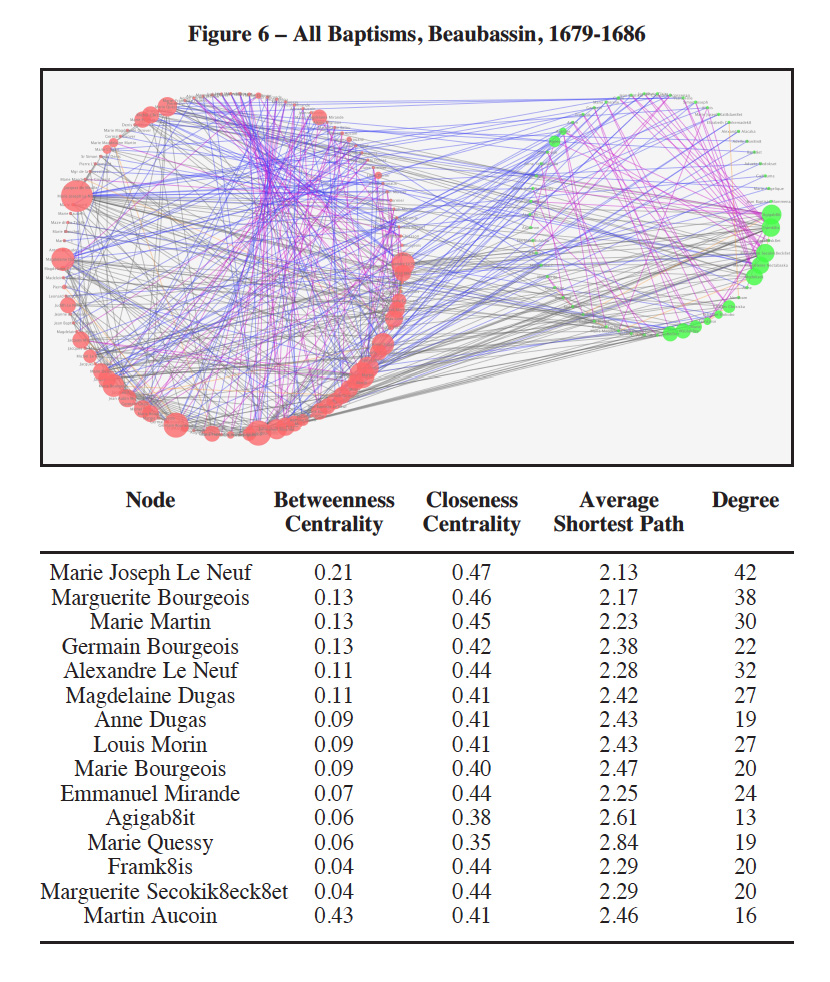

58 This image changes slightly if we account for the fact that both in figures 2 and 5 our data has been sorted by ethnicity before being displayed in the graph. In Figure 2 we used Winston de Ville’s transcribed parish records, which, with a handful of exceptions, included only French participants. In Figure 5 we have selected all of the records involving Mi’kmaw participants from the transcription and archival sources. In bringing this record set together, we have an opportunity to understand what this community looked like as a whole.

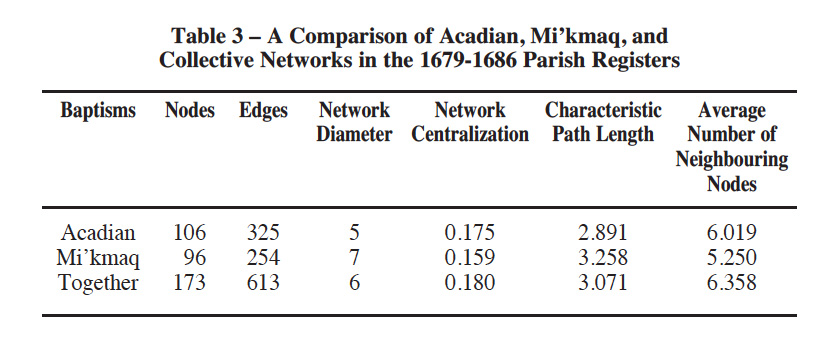

59 Table 3 below compares the reconstituted parish registers, as they appeared in the original source, with the separate Mi’kmaw and Acadian analyses presented earlier in this article. What is immediately noticeable is that the Mi’kmaw network was less centralized, with longer paths between participants, a higher network diameter, and fewer neighbours. This suggests that the Mi’kmaw community (as reflected through this Catholic source) was slightly less cohesive, at least when considered alongside their Acadian neighbours. That the overall network, which more closely reflects the source itself, is similar to the Acadian graph points to the prominence of key Acadian figures in baptisms in both communities and their overwhelming presence in the parish registers.

Display large image of Table 3

Display large image of Table 360 Indeed, focusing more specifically on the individuals listed in Figure 6, it is clear that both prominent Acadians, such as the Le Neuf and Bourgeois families, and prominent Mi’kmaq dominated late-17th-century social networks. Only two of the people who ranked in the top 15 for betweenness centrality (Marie Bourgeois and Martin Aucoin) were not involved in Mi’kmaw baptisms during these years, suggesting that it was the centre families at Beaubassin who interacted most directly with the Mi’kmaq. Equally important is the prominence of women in linking this network together, a subject that requires deeper investigation.

61 It must be remembered that the relationships depicted here are those shaped by the church. The priest who recorded these events, Claude Moireau, is not depicted in this graph. Obviously, everyone in the graph would have been connected to him. In this early period, the priest was the key player in binding these two communities together. Rameau considered Moireau the “trait d’union” between the French and the Mi’kmaq.78 Though living at Beaubassin during this period, Moireau was an itinerant missionary throughout Mi’kmaw and Wolastoqiyik territory. From 1675 to 1680 he served both French and Indigenous communities throughout the region, visiting the Saint John River Valley, Minas Basin, and Gaspé. In 1680 he replaced Chrestien LeClercq, who until that time had been the principal missionary in Mi’kma’ki. Rather than relocating to LeClercq’s mission on the Miramichi, however, Moireau spent his time at the rapidly expanding French settlement at Beaubassin. There he built the first church, dedicated to Notre-Dame de Bon Secours, and served the French and Mi’kmaw communities until 1686.79 It is likely that Moireau’s arrival in the region was the first time that many Mi’kmaq encountered a Catholic priest. Over half (57 per cent) of the people he baptized were adults over the age of 15. Of the 13 baptized children, 5 were children of parents who were baptized at the same time.80

62 Although important, Moireau’s departure did not mark a point of rupture in this relationship though it does suggest a difference in the Catholic clergy’s relationship to the Acadians and Mi’kmaq in the region. His successor, Jean Baudoin, a former musketeer in the King’s guard before his calling to the cloth, accompanied Mi’kmaq from the region on war parties in northern New England and Newfoundland.81 In 1693, the French governor accused Baudoin of failing to serve his Acadian parish in favour of working among the Mi’kmaq.82 Indeed, it seems quite likely, given that he died in 1698, that Baudoin spent much of his ministry at Beaubassin outside of the Acadian community and with the region’s Mi’kmaw population. Even after his death, Catholic priests continued to favour their work among the Mi’kmaq. In 1705 the French governor at Port Royal requested additional priests for the colony, claiming that the men serving Port Royal and Beaubassin had left the Acadian villages to work among the Mi’kmaq.83 This likely explains some of the gaps in the parish records from the community.

63 If we place the parish registers in this broader context of priestly absences, and look at a wider array of colonial census records, the separation between these two communities is even more apparent. Although the numbers align in the 1680s, broader French enumerations of the Mi’kmaq in the region yield a much larger population than the 57 people who appear in the registers, demonstrating that the families of Agigab8it/ Neme8a8rbis and Framk8is/Marguerite Secokik8eck8et were likely anomalies.

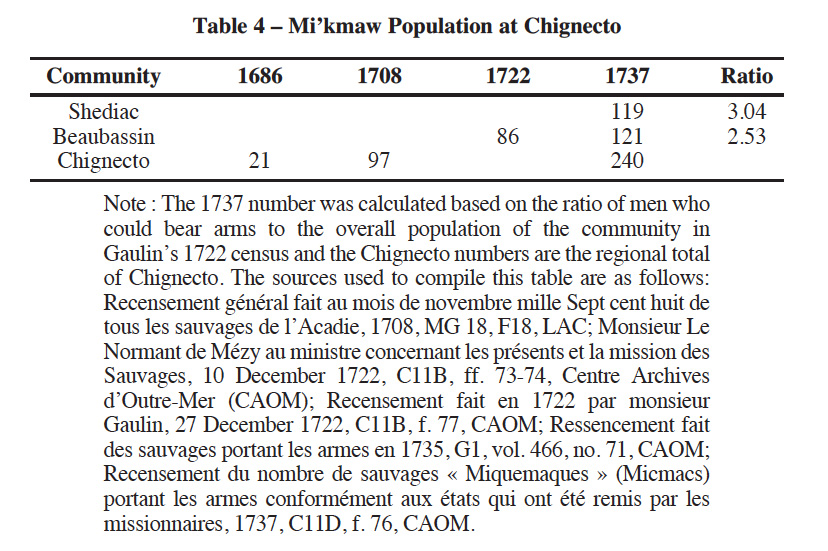

Display large image of Table 4Note : The 1737 number was calculated based on the ratio of men who could bear arms to the overall population of the community

in Gaulin’s 1722 census and the Chignecto numbers are the regional total of Chignecto. The sources used to compile this table

are as follows: Recensement général fait au mois de novembre mille Sept cent huit de tous les sauvages de l’Acadie, 1708,

MG 18, F18, LAC; Monsieur Le Normant de Mézy au ministre concernant les présents et la mission des Sauvages, 10 December 1722,

C11B, ff. 73-74, Centre Archives d’Outre-Mer (CAOM); Recensement fait en 1722 par monsieur Gaulin, 27 December 1722, C11B,

f. 77, CAOM; Ressencement fait des sauvages portant les armes en 1735, G1, vol. 466, no. 71, CAOM; Recensement du nombre de

sauvages « Miquemaques » (Micmacs) portant les armes conformément aux états qui ont été remis par les missionnaires, 1737,

C11D, f. 76, CAOM.

Display large image of Table 4Note : The 1737 number was calculated based on the ratio of men who could bear arms to the overall population of the community

in Gaulin’s 1722 census and the Chignecto numbers are the regional total of Chignecto. The sources used to compile this table

are as follows: Recensement général fait au mois de novembre mille Sept cent huit de tous les sauvages de l’Acadie, 1708,

MG 18, F18, LAC; Monsieur Le Normant de Mézy au ministre concernant les présents et la mission des Sauvages, 10 December 1722,

C11B, ff. 73-74, Centre Archives d’Outre-Mer (CAOM); Recensement fait en 1722 par monsieur Gaulin, 27 December 1722, C11B,

f. 77, CAOM; Ressencement fait des sauvages portant les armes en 1735, G1, vol. 466, no. 71, CAOM; Recensement du nombre de

sauvages « Miquemaques » (Micmacs) portant les armes conformément aux états qui ont été remis par les missionnaires, 1737,

C11D, f. 76, CAOM.

64 In the most detailed enumeration of the Mi’kmaq before the mid-19th century – Antoine Gaulin’s 1708 census – a population of 97 people are listed at Chignecto; 14 years later, in another census taken by the Catholic missionary, the number dropped to 86. Thirty years after that, there were twice as many people (although here we have included the community nearby at Shediac, enumerated for the first time in this census).

65 If we take the 1708 census (which provides names, ages, and family groups) as representative of the most detailed understanding the French developed of the Mi’kmaq as a collectivity, then the information provided in the parish registers suggests that this community was very poorly understood. Of the names in the census only a handful of people re-appear in the registers and, of those, we can only guess based on the similarities of first names and ages. For the most part, the Mi’kmaq in the parish registers do not seem to appear in the 1708 census. Similarly, it is also clear that only a handful of the region’s Mi’kmaw inhabitants appear in the parish registers. After the 1680s, in fact, very few individual Mi’kmaq appear in the historic record at all, suggesting a growing distance between these communities.84

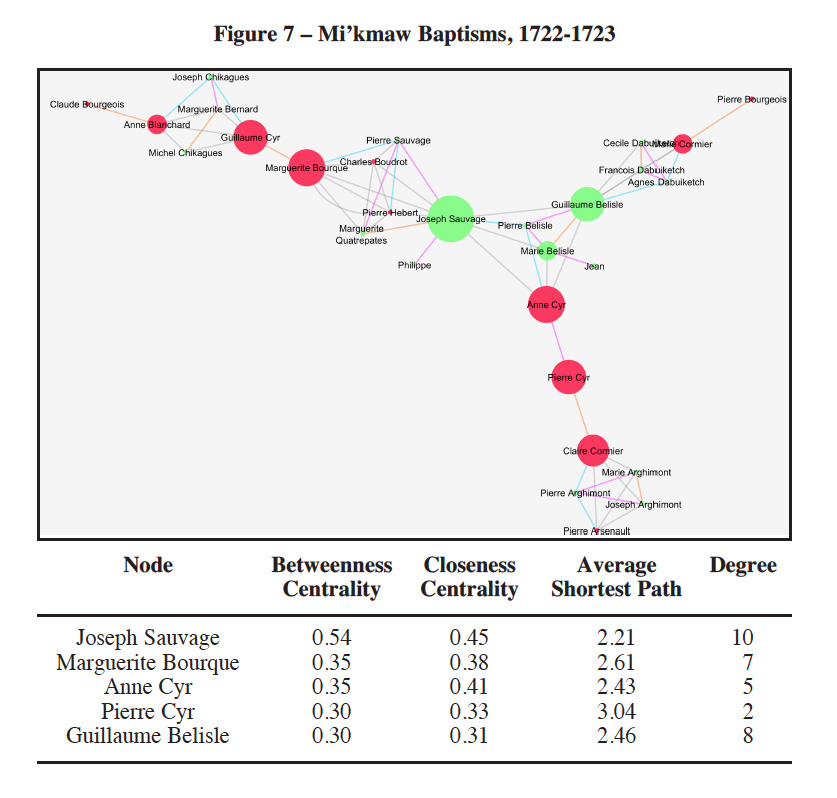

66 Despite these discrepancies in the historical record, SNA can help us avoid overstating the separation that may have existed. There are five parish records from the early 1720s that involve Mi’kmaw individuals. Given that the records were written a mere ten months apart, it should be hardly surprising to learn that they form a single network. Here we see that two Mi’kmaw men – Guillaume Belisle and Joseph Sauvage – lie at the heart of the network connecting these records together.

67 Careful attention to the Acadian participants is also revealing. Of the twelve Acadians in this network, three are members of the Cyr family. Two of these people, Anne and Guillaume, were particularly well connected to the Mi’kmaq. The Cyrs, according to Gregory Kennedy’s work on this community, emerged as a prominent family in Beaubassin during the 18th century along with the Bourgeois and Cormiers, founding families of the Acadian settlement. This small window suggests some continuity with the earlier records but also the evolving nature of the relationship between the Mi’kmaq and Acadians. Much like the network from the 1680s, the relationships between the Acadian and Mi’kmaw communities in Chignecto were structured through some of the community’s most prominent families even while the specific family composition seems to have changed over time.

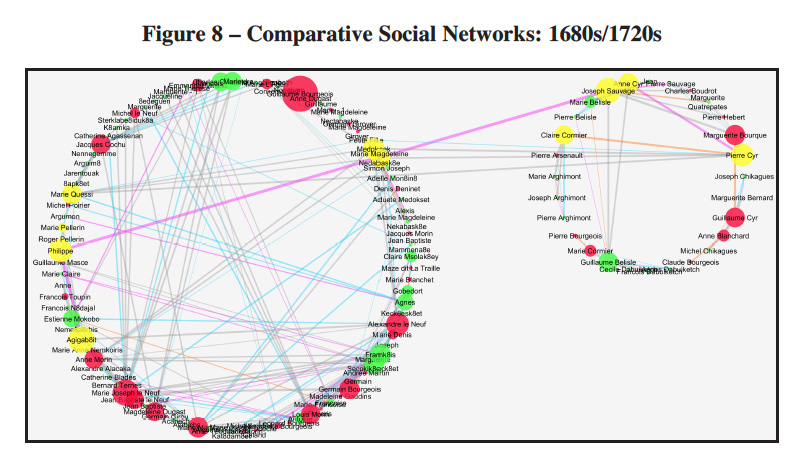

68 Merging the two networks reinforces this conclusion. For the most part they form two separate networks (depicted in Figure 8 as two circles); we can see that they remained connected in a meaningful way through the Acadian Pierre Cyr and the Mi’kmaq Philippe (highlighted in yellow alongside their first-degree neighbours). Note that in Figure 9, which extracts these relationships, Philippe and Pierre are the two nodes that link both networks with a high level of connectedness. Given the dominance of centre families in each network, the idiosyncratic nature of the parish records, and these possible bridges between record sets, this social network graph suggests that perhaps key members from these communities remained connected throughout this period.

69 By combining these records, another important pattern emerges. The one person we may be able to trace through the documentary record over this period is Philippe. In 1685, he appears in the parish registers as the baptized nine-year-old son of Agigab8it. In the 1708 census, there is only one man using the name Philippe (Arguimeau) and he is listed as being 38 years old, about the age Agigab8it’s son would have been at that time. Though Arguimeau is not identical to Agigab8it – a six-year gap remains between their ages – if we assume an error in transcription here, the rest of the data seems to be congruent with this being the same person.85 In the census, Philippe Arguimeau had a son, Joseph, who was ten years old. In the 1720s, Philippe and Joseph appear again in the parish registers where Joseph served as a godparent and the priest noted that Philippe was his father and a Mi’kmaw keptin (captain). The Arguimeau family is also the first to be listed in the 1708 census, perhaps suggesting family prominence and that we are working with the same person. William C. Wicken has also identified continuity in the prominence of this Mi’kmaw name. In addition to the parish records, he notes that men named Arguimeau signed treaties on behalf of the Mi’kmaq at Chignecto in 1726 and 1761, as well as setting out to negotiate with the British in 1755.86

70 Although this analysis is built on circumstantial evidence – based on a misalignment of Philippe’s name – what we know about 17th-century Mi’kmaw leadership structures is consistent with the evidence above. French officials who observed Mi’kmaw society during this period noted that keptins were often male and selected through a combination of their family relations and success in war and hunting.87 Le Clercq believed that household size and relationships were critical components to achieving leadership in Mi’kmaw communities.88 At the local level, keptins administered the distribution of hunting territories, managed the collection of furs, and helped to shape the community’s response to issues that affected all of its members.89 All of this would explain both Agigab8it’s prominence in the parish records of the 1680s and the continuing interactions of his family with the Acadian community growing up around them.

71 Throughout the French regime, a Mi’kmaw presence is consistently noted in the area around the Acadian settlement at Beaubassin. Indeed, a 1751 map of the Chignecto Isthmus notes the presence of a Mi’kmaw wikuom, a dwelling, and burials just south east of Fort Gaspereaux about 20 kilometres away from the principal Acadian village at Beaubassin.90 Though the historical record demonstrates that it is unlikely a strong relationship existed between the Mi’kmaq and the Acadians (otherwise we would expect them to appear more regularly in the parish records and other sources), social network analysis presents a more nuanced picture of the way these communities interacted. It demonstrates that these relationships were likely built through the fur trade and, though declining over time, persisted for decades. What SNA reveals to us is that some Mi’kmaq and some Acadians in the Chignecto region developed relationships strong enough to participate in religious acts together. Examining those relationships helps us to better understand the nature of both Acadian and Mi’kmaw social and political life at the turn of the 18th century.

Conclusion

72 In the historiography, Beaubassin stands out as the least understood Acadian settlement of the pre-deportation era. An isolated region for French and British alike, it remained an important part of Mi’kma’ki and a commercial centre for colonial trade networks to Quebec, Louisbourg, and New England. Unfortunately, the incomplete historical record has always been a challenge for those wishing to reconstitute or better understand Beaubassin’s community dynamics. In this article, we employed SNA methods to provide new insights and to suggest new lines of inquiry. Our research results reveal how the community evolved over 80 years and three generations, from the overlapping of founding groups from Port Royal and Quebec through a period of wider dispersion to a more developed stage of cohesive social hierarchy complete with defined centre, periphery, and edge groups of households. A more focused approach around the Campagnard witchcraft trial allows us to retrace the close links between the family of Michel Le Neuf and several peripheral households, who worked together to eliminate a rival. Similarly, attention to records involving the Mi’kmaq reveals some of the inner workings of these communities. By restoring a complete data set from archival records involving Mi’kmaw individuals whose records were not transcribed into published versions of the parish registers, we have been able to find evidence for greater connection between prominent Acadian and Mi’kmaw households than has previously been understood. In Beaubassin at least, close relationships between some Acadian and Mi’kmaq went beyond trade and may have persevered right up to the time of the community’s destruction. Further analysis with SNA for this and other early modern communities holds promise for a better understanding of daily life, power, and influence in the Atlantic region.