Historiographic Commentary

Critical Museum Theory/Museum Studies in Canada:

A Conversation

1 CANADIAN SCHOLARS HAVE BEEN CRUCIAL in shaping the active field of critical museum theory/museum studies, with anthropologists, sociologists, historians, art historians, and curators working to challenge and reimagine the educational function, social role, politics, and pedagogy of museums while expanding the very notion of what a “museum” has been in the past and could become in the future. The trajectory of this endeavour has been examined at length in university courses, essays, and handbooks, which all highlight arguments made since the 1960s about the powerful role of museums in reinforcing class distinctions, creating narratives of national identity, and glorifying colonial attempts to subjugate Indigenous peoples as well as more recent considerations of how museums foster the active contributions of visitors, promote varying modes of intercultural exchange, and enable affective encounters with memory.1 In an effort to reflect on the current state of this field in Canada and share some of its diversity, Lianne McTavish decided to pose questions to leading scholars and invite their response. Her goal was to highlight the issues of particular interest to Canadian museum scholars, which have developed alongside but also in distinction from the burgeoning literature on museums stemming from the United Kingdom, United States, and Australia – all centres of research on museums. In September of 2016, McTavish approached another specialist of Canadian museums, Andrea Terry, who helped create a group of participants able to address pressing concerns from a variety of backgrounds, including cultural studies, art history, and communications. What follows is the e-mail conversation that took place among the five co-authors, although some of them have also met in person to exchange ideas. This discussion moves far beyond a narrow, bricks and mortar conception of museums to include the effects on museum practices of government policies, shifting funding models, the 2015 report released by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, and the celebration in 2017 of Canada’s 150th “birthday.”

2 Susan Ashley is a cultural studies scholar interested in the “democratization” of culture and heritage institutions, especially in relation to access and expression by minority groups. She has published numerous refereed articles on museum policy and practice, and edited the book Diverse Spaces: Identity, Heritage and Community in Canadian Public Culture. Heather Igloliorte is an art historian of Inuit and other Native North American visual and material culture whose research centres on circumpolar art studies, the global exhibition of Indigenous arts and culture, and issues of colonization, sovereignty, resistance, and resurgence. In addition to her research and writing on these subjects, she has been an independent curator of Indigenous art for the last 12 years; her nationally touring exhibition, SakKijâjuk: Art and Craft from Nunatsiavut (2016-2019), is accompanied by a 188-page full-colour catalogue of the same name, produced in three volumes ( English, French, and Inuktitut). Lianne McTavish has published widely on the history of museums in Canada including a monograph Defining the Modern Museum, which focuses on the history of material exchange, women’s contributions to museology, and professionalization at the New Brunswick Museum in Saint John. Her current research project examines small town and rural museums in Alberta, and she regularly curates exhibitions of contemporary art. Kirsty Robertson has produced numerous publications on activism, visual culture, and changing economies, with a monograph, Tear Gas Epiphanies: Protest, Museums, and Culture in Canada, near completion. She is currently undertaking a large-scale project focused on small-scale collections that work against traditional museum formats. Andrea Terry specializes in contemporary, modern, and historic visual and material culture in Canada, as well as contemporary cultural theory, and gender issues. Among her many publications in these areas is a monograph, Family Ties: Living History in Canadian House Museums.2

What is the present trajectory of critical museum theory/museum studies in Canada? What would you consider the most important developments in the field?

3 Kirsty Robertson (KR): There are two points that strike me. One comes from Ruth Phillip’s 2015 essay on the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, which describes the recent disappearance or shrinkage of many programs that grew out of the Task Force Report on Museums and First Peoples (released 1992).3 Phillips notes significant funding cuts to such programs, the retrenchment to settler histories in major institutions, and a backing away from many successful collaborations that took place between Indigenous (primarily First Nations) communities and museums.4 Heather Igloliorte, on the other hand, notes that when authoritative museums are faced with cuts and parochialism, independent curators can sometimes intervene in museum narratives in ways that permanent staff cannot.5 At the juncture of these two observations, I see some very interesting developments. For example, a number of important critical interventions have recently taken place at institutions that have been considered to be quite conservative – provincial/municipal/university galleries – but are now breaking new ground through projects that are curator-led (both by permanent and independent curators). It is as if the critical museum theory of the past decade is being pushed in new directions through practice, through projects driven by critical questions coupled with extensive programing and in-depth catalogues. Work by curators such as Srimoyee Mitra (Border Cultures: Parts One, Two, and Three, Windsor Art Gallery) and Wanda Nanibush (Toronto: Tributes and Tributaries, 1971-1989, Art Gallery of Ontario) have unsettled some major institutions in challenging and provocative ways, in each case using a close examination of the gallery’s location in its respective city to ask questions about migration, borders, and belonging (in cities, nations, and in art collections and archives).6 Similarly, artist Brendan Fernandes’s performative dialogue with the African collection at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre (Queen’s University, Kingston) reversed expected museum norms through direct engagement with the artefacts.7 I have also been inspired by the work of a number of emerging curators. Among them is cheyanne turions, who often uses the term “thinking alongside” in her projects to describe how curators can work with/converse with artists and other practitioners in order to create exhibitions that are open-ended or that ask questions rather than providing answers. Her approach expands the role of curator into that of a visible participant in, rather than an organizer of, exhibitions.8 It would seem then, that faced with retrenchment, the art/museums world has responded thoughtfully and with originality; but, as Phillips notes, all of these projects are fragile, and dependent upon continued funding.

4 Susan Ashley (SA): My research interests stem from my background in communication and cultural studies, rather than museum studies. Museums and heritage are the sites where I engage with concerns around the making and communicating of cultural heritage. This research may or may not coincide with practices on the ground within Canadian museums. From my studies of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, practical urgencies of debt, static funding, and shrinking audiences take a front line. Yet my concerns are about how museums go about “democratizing” cultural production, understanding how people express culture and heritage, and the role that museums might play in their cultural lives.

5 Thus, my studies of museums in Canada, and elsewhere, have a critical focus on “democratizing” and “publicness” in relation to museums as social institutions. This began with my earliest publication as a MA student reflecting on museum’s changing role as both voice of authority and as a space for public opinion.9 I think it is still important to consider these two concepts of “democratizing” and “publicness” as central to museum theory and museum practice in Canada. The concepts have been infinitely theorized, and I cannot review all here. Important to me has been the way cultural policy theorist Kevin Mulcahy differentiates between activities that “democratize culture” and “cultural democracy.”10 The first is a process by which institutions disseminate and enable access to cultural forms in order to enlighten or educate its citizens. The second is a more bottom-up form of policy that supports platforms where people are culturally active on their own terms. “Publicness” is an odd word, but it encapsulates that feeling for me when I think about the ideals of “contact zone” — the role of the museum as a social space in our shrinking public sphere, but also a quality denoting transparency, performance, or “for the good of all.”11

6 Lianne McTavish (LM): Both Robertson and Ashley note how financial constraints can hinder the social and political opportunities supported by museums and which contribute to a retreat from some of the goals espoused by museum scholars, including the indigenization and democratization of museum spaces. Museum administrators and workers sometimes receive conflicting messages, encouraging them on one hand to shore up the authority of the museum and provide quantitative evidence of its value – usually understood as the sheer number of visitors rather than the quality of their experience; they are also asked, on the other hand, to promote inclusiveness by inviting people to make their own meanings within museums, drawing attention to the exclusions and weaknesses of such organizations. This paradox is not exactly new according to Tony Bennett’s arguments about the multiple contradictions informing 19th-century museums, but as Robertson points out it can enable ingenious strategies that both make visible and resist conservative museum structures, including a glorification of settler histories, and insistence on narrow definitions of the “museum” that exclude many small, local sites of heritage production.12 In addition to the curatorial practices she mentions, I believe that another crucial development in critical museum theory/museum studies in Canada and elsewhere is the increasing attention paid to small, rural, community-based, and independent museums and galleries. Much previous literature, including my own, analyzed large, urban, national and provincial museums, but now scholars like Fiona Candlin and Kirsty Robertson, among others, are turning their attention to small, strange, and apparently marginal “micromuseums and showing how such institutions are influential, important, and worth careful study.”13 My current work is focused on the small town and rural museums in Alberta, noting how the mostly local museum workers and volunteers strive to attract tourists while engaging the community in meaningful ways despite limited resources (http://albertamuseumsproject.com). I analyze the innovative solutions used at such museums as the Fort Chipewyan Bicentennial Museum in northern Alberta, which acts as a cultural centre allowing the largely Indigenous community to tell family histories within it, and the World Famous Gopher Hole Museum in the central Alberta hamlet of Torrington, which reshapes the conventions of 19th-century natural history museums to offer dioramas filled with taxidermied gophers that theatrically enact the region’s heritage. These unique museums defy authoritative government policies and standard narratives in ways that give me hope about the future of museums, however museum processes are defined or understood. Studying these museums, at the same time, can be threatening to the institutional definition of museums and I have received negative feedback from some members of the Alberta Museums Association (AMA), a non-profit society that promotes the development of museums in Alberta, highlighting those that adhere to its set of professional standards. In the Spring 2017 newsletter of the AMA, the vice-president of its board of directors decried my “loose definition of a museum which includes a number of commercial shops that happen to feature displays, as well as tourist attractions with minimal educational interpretation.”14 This response indicates that more expansive scholarly work can unsettle the authority of museums in Canada, challenging the forms of professionalization that developed slowly and unevenly during the 20th century and that were arguably never hegemonic; I have analyzed how this process took place at the New Brunswick Museum in Saint John, where efforts to replace so-called “amateur” curators with those equipped with university degrees and primarily devoted to researching and preserving collections were fiercely resisted, providing a point of comparison for my current research on the small town and rural museums often run by local people without official museum training and interested in entertaining as well as educating a broad public.15

7 KR: At the same time as these interesting developments are occurring, I am quite fascinated by what is not happening in Canada. I have been watching, with great interest, museums in the United States respond to the Trump administration. For example, the Museum of Modern Art rehung part of their permanent collection to include works by artists from countries that would have been affected by a travel ban.16 Numerous small museums in New York City responded to the call for the #J20 art strike, and shut their doors for a day.17 Some of these are the same institutions that Chin Tao Wu and others called out in the 2000s for their deep links to the wealthy elite, and they are, in some cases, the same institutions that have been criticized for accepting funding from oil companies and other controversial sources.18 Yet they do seem to be stepping out of a torpor and acting to respond to the current moment. Concurrently, major museums such as the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, have instituted “rapid response” collecting models, which allows them to collect “in response to major moments in history that touch the world of design and manufacturing.”19 What would such models of rapid response collecting and curating look like in Canada? That is a question, I think, that remains to be answered.

How has the Truth and Reconciliation Commission affected museums and/or critical museum theory in Canada?

8 Andrea Terry (AT): The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s activities (2010-2015) cast “an undeniable light on mechanisms and effects of Canada’s colonial formation that reverberate through the conditions and relations in the present.”20 As editors of The Land We Are: Artists and Writers Unsettle the Politics of Reconciliation, Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill and Sophie McCall – Métis artist and settler scholar respectively – characterize reconciliation as “contested terrain in relation to Canada as an ongoing settler colonial enterprise.” Public interest in the TRC motivated various cultural sectors to provide “unprecedented funding” and generate reconciliation-themed exhibitions, public events, and symposia.21 This thematic focus, however, prioritizes the concept of reconciliation, thereby dismissing land rights and/or restitution. And so, as burgeoning scholarship and ensuing art projects attest, artists and writers remain committed to continually invoking processes of decolonization, particularly those pertaining to reconciliation discourse.

9 Not only are the artworks arising from such collaborations insightful, provocative, and engaging, so too is the accompanying scholarship. In their co-edited collection of essays, Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Stó:lō scholar of Indigenous art and music Dylan Robinson and settler scholar of Indigenous literatures Keavy Martin characterize such endeavours as “aesthetic action” – artistic practices that play upon all the senses, revealing how public structures and national discourses “privilege certain bodies and contribute to the ongoing oppression of others – and also suggest to us possibilities for different kinds of engagement and understandings.”22

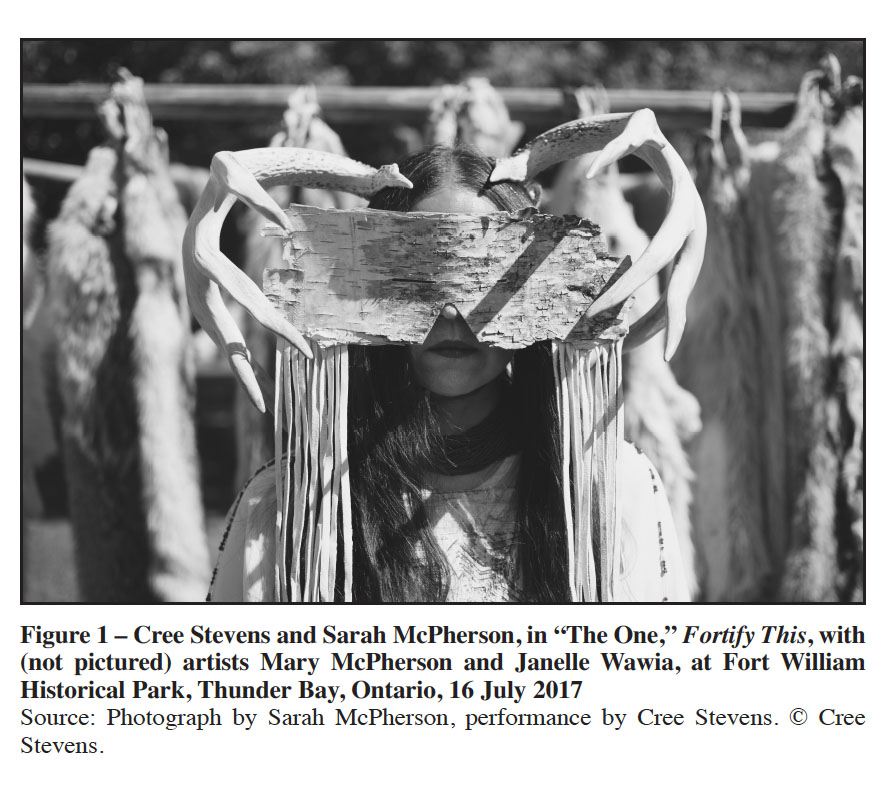

10 Now while a great deal is currently in the works and much remains to be explored further, a good example of collective engagement in “aesthetic action” is unfolding in Thunder Bay, Ontario, where I live and work at present. Working in collaboration with Anishinabekwe (Ojibwe) and Cree First Nations artist Cree Stevens, we organized a performance procession entitled “Fortify This” in which invited Indigenous artists produced wear-able art and perambulated through Fort William Historical Park (FWHP), a reconstructed 19th-century fur trade fort and “living history” site that offers guided tours by period-costumed interpreters (see Figure 1). This took place on 16 July 2017, and our collective goals were to first highlight the longevity, complexity, and creativity of Indigenous visual, material, and performative cultural production in northwestern Ontario; second, we wanted to bring together emerging and mid-career artists, as well as local Indigenous youth – especially those involved in Neechee Studio23 – so that we might collaborate and decolonize representations of the past in the present and also push for more critical awareness in the public sphere.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 111 In calling attention to the achievements of performance art and artists, the date selected for this project marked 30 years since internationally renowned multi-disciplinary artist Rebecca Belmore (Anishnaabe) (b. 1960), from Upsala, Ontario, and a member of the Lac Seul First Nation at Frenchman’s Head, Ontario, performed Rising to the Occasion in association with Definitely Superior (Thunder Bay’s artist-run centre). Wearing a Victorian-style ball gown with a protrusive bustle resembling a beaver dam that visually signalled the colonial fur trade’s primary target, Belmore strode down the streets of downtown Thunder Bay, providing a critical response to the 1987 British royal visit of Prince Andrew and Lady Sarah Ferguson to Thunder Bay and, more specifically, to FWHP.24 Occurring in the context of the silent protest parade, Twelve Angry Crinolines, conceived of and organized by Lynne Sharman, Belmore characterizes this performance in a 2014 interview with curator Wanda Nanibush as “key to building a foundation for my performance art practice.” Twelve Angry Crinolines included both the silent procession up Red River Road and a “mad tea party” held in Northwestern Ontario’s first artist-run gallery organization, Definitely Superior. Nine performance artists took part, Belmore leading the way followed by Kim Erickson, Karen Maki, Lynne Sharman, Ana Demetrakopoulos, Lori Gilbert, Glenna McLeod, Joanne Lachapelle-Bayak, and Sandy Pandia. Belmore goes on to recall: “The royals came to our city for a handful of hours as performers, replaying colonial history complete with birch bark canoes and a fake fort. This was incredibly absurd to me. What to wear for such an absurd occasion?”25 Using Belmore’s work as a jumping-off point, “Fortify This” sought to highlight the presence and accomplishments of Indigenous agency and cultural continuities and, more precisely, to decolonize FWHP. As a project of social justice and resistance, decolonization supports and mobilizes Indigenous rights, cultural autonomy, self-determination, and sovereignty. Working collaboratively, our work aimed to strategically disrupt entrenched settler colonial discursive and representational systems in contemporary Canadian society and chart new courses for the future. In so doing, we look to films such as Coming Together to Talk (Thunderstone Pictures, 2016), a documentary by Michelle Derosier, Ardelle Sagutcheway, Savannah Boucher, and Casha Adams. Filmed over nine months, it explores the lived realities of Indigenous youth in Thunder Bay, Ontario, through interviews with youth, Indigenous scholars like Dr. Cynthia Wesley-Esquimaux, and lawyers such as Dr. Cindy Blackstock. All of these participants come together and emphasize the need to listen to difficult and uncomfortable conversations and to acknowledge both the oppressive policies that require the youth to leave their families to attend school in Thunder Bay and the consequent fears, threats, and racial discrimination that often accompanies such experiences as well as the possibilities for change. As Derosier puts in a CBC interview talking about the film, she learned to heed these conversations, to learn “what it is that we need as Indigenous people, not what other people need, not what colonial structures need from us, or want from us, or have taken from us, but what we need to heal ourselves.” The film underscores this point featuring an animated crow who appears sporadically throughout, speaking directly to the youth in Ojibway, telling them they are loved, valued, and worthy – that their ancestors accompany them to help fortify them. Speaking to the bird’s significance, Derosier explains “a crow can adapt and it can live in the bush and it can live in the city and it can do that very well. . . . We can learn from that, from the animals, from the birds.”26

12 KR: Reconcile This! – a special edition of West Coast Line (published in 2012) – was one of my favourite texts that I read last year.27 Drawing on that journal, I think that on the one hand the TRC has helped to stop the retrenchment that Phillips was noting under the Harper government, and has put First Peoples’ issues front and centre in many museums. But, on the other hand, all of those actions require seeing the TRC as a fully positive undertaking: they require seeing the federal government apology and the TRC as a culmination of reconciliation, rather than seeing reconciliation as a long-term practice tied up in much wider processes of decolonization. In short, the important criticisms that many had of the TRC, and that Terry mentions above, never really showed up in museums, even as institutions were willing to undertake some of the recommendations. I think these tensions are illustrated by the embrace by museums of the Canada 150 celebrations.

13 Heather Igloliorte (HI): I think that many Indigenous artists, curators, and scholars in particular are also hesitant to engage in the 150 celebrations for some of the same reasons that Robertson has outlined. Of course, it would be ridiculous to celebrate Canada’s sesquicentennial and leave out Indigenous peoples; there would be rightful outrage at an erasure of that kind, and Indigenous peoples do have something of value to add to this national conversation. To begin with, projects such as Kent Monkman’s nationally touring exhibition Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience at the Art Museum of the University of Toronto have been intentionally staged during the sesquicentennial celebrations to draw the public’s attention to the darker side of Canada’s “birthday” and provides a sober counterpoint to the patriotic festivities. Furthermore, I would not fault any Indigenous person for applying for 150 funding to do something good for their communities or to celebrate their resilience. Although I have declined several 150-related invitations this year, I did recently participate on an Indigenous-led jury to create a book series celebrating the work of three generations of Indigenous artists in Canada – this is the small way that I decided I felt comfortable in taking part. At the same time, I question how Canada can justify the heavy price tag for these nation-wide activities while telling First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples that it does not have the means to honour its responsibility to provide its citizens with urgent, basic needs like clean drinking water and childhood education. As my colleague filmmaker Alethea Arnaquq-Baril recently remarked during a Walrus Talk on the same topic, “Why isn’t my land, water, language, education, or health worth spending this kind of money on?”28 In addition, other First Peoples, and particularly artists, are troubled about being asked to participate in the celebration the 150th anniversary or to accept funding from its coffers.29 To do so is to tacitly ask us to also celebrate, or at least ignore, our shared history of attempted genocide and ongoing colonialism. And there is a very real fear that the timing of this all, coming at the conclusion of the TRC processes and the mobilization for the Calls to Action, will be viewed as the celebratory “end” of the reconciliation process, when we have just barely begun to collectively understand the “Truth” in “Truth and Reconciliation.”

14 KR: Exactly – how can museums work towards reconciliation while simultaneously celebrating the imposition of a settler nation? And it is frustrating to have to ask these questions, because I believe that museums large and small are full of people who understand how problematic uncritical celebrations of Canada’s 150th “birthday” are but who are simultaneously beholden to funding programs that dictate content. As I noted earlier, via Phillips, funding cuts can lead to retrenchment and parochialism in museums. But there is another side, as public funding is essential. It can be deeply problematic, however, when it comes with strings attached. There are many critiques of the corporate sponsorship of museums and exhibitions, but government funding is sometimes equally or even more suspect. Arguments against or even critical of government funding are so complicated, because they inevitably collide with right-wing agendas to defund public monetary support of the arts as in the recent proposed defunding of the National Endowment for the Arts in the States.30 Ultimately, I do think the TRC recommendations had an effect on museums, and on the institutions that train museum workers, but I also think that the shortfalls illustrate how deep the processes of decolonization must go to have effect – and we are a long way from there.

15 SA: I know little about the impacts of TRC on Canadian museums and defer to Igloliorte, Terry, and Robertson. My only remark comes from my experience studying the Royal Ontario Museum. During research there in 2009, I was aware of the participation of ROM’s curators in the Canadian Museums Association and the Assembly of First Nations’ major cross-Canada inquiry into representation in museums – the Task Force on Museums and First Peoples that was sparked by The Spirit Sings and other museum disasters.31 I was struck in 2009 by negative remarks by one ROM senior curator on the task force, who felt that very little had been done to encourage participation and collaboration by First Nations community members in exhibition development. Rather, the curator felt that lack of time and resources, and the strength of market-driven decision-making in the institution, determined the museum’s agenda. When I returned to the ROM in 2016 to do further research, senior management said that the redevelopment of the First Peoples’ Gallery would be entirely collaborative in nature with strong leadership from Indigenous staff members and external communities.” I have no confirmation yet that this is truly the case and what the process on the ground has been, but the ethics of management may well have changed if one can judge by their recent public apology to an African Canadian group that had protested over the Into The Heart of Africa exhibition.32

16 HI: I agree with Ashley. I feel that today we have to approach such efforts by museums with a kind of sceptical or even cynical optimism: we should hope for the good outcomes but anticipate challenges to this process. We must demand transparency in the process and accountability to the community. The thing we have to keep in mind about the on going legacy of the task force report is that it constitutes a series of “principles and recommendations” that were never formally adopted as policy.33 So while in the 1990s and early 2000s great strides were made towards the decolonization of museums in Canada that seemed to indicate an irreversible march forward – including increasing Indigenous access to and interpretation of the cultural heritage held in museums, the repatriation of human remains, and the training and hiring of Native staff – under the Harper government we witnessed the swift demise of much of this critical relationship-building work across the country. Curators, museum staff, and collections managers who had been previously able to foster and maintain long-term, respectful, reciprocal relationships with Indigenous and other stakeholder communities were undermined and underfunded for the better part of a decade as cultural and museum funding was slashed, and artists and Indigenous organizations were likewise devastated by dramatically decreased spending on the arts and heritage.34

17 Now with Trudeau’s government beginning to undertake the restoration of funding for the Canada Council for the Arts, it appears that things are looking up again. This, coupled with the Canada 150 funding and the movement around the TRC Calls to Action regarding museums and First Peoples, seems to herald a positive new era; but I have learned that we cannot take this work, or the funding and institutional will required to adhere to best practices, for granted. Until such time as there is a balance of power in our institutions – in terms of not only curatorial staff but also administration and board membership – there is no guarantee that the ethical, progressive work of one generation will continue.

How do different scholars and practitioners approach the study of museums?

18 LM: Museums provide opportunities for scholars from diverse backgrounds, allowing them to bring their own questions and training to the subject and have their research reshaped by the encounter. It is, therefore, difficult to identify critical museum theory/museum studies as a discrete field of study, despite the proliferation of courses, anthologies, and textbooks in the area. Although museums – however defined – challenge scholars to rethink their methodologies, investigators perhaps inevitably bring a disciplinary framework to their research by producing and evaluating arguments about museums based on their own training such as drawing on the forms of knowledge production considered most legitimate within their disciplines. It is striking that historians of art and visual culture, including Ludmilla Jordanova and Carol Duncan, examine how museums promote specific kinds of looking, using museum installations and displays as primary sources worthy of careful analysis.35 Cultural theorist Mieke Bal likewise argues that the arrangement of objects and other visual signs creates narratives, regardless of the intentions of creators or perceptions of specific audiences.36 This focus on how sites of display convey messages using visual conventions, spatial dynamics, and juxtaposition is typically of less interest to historians, who often rely on written documents and archival records to produce accounts of the creation and construction of displays and who place such accounts within broader frameworks related to nation building, government funding, or the influence of particular patrons or administrations while highlighting change over time.37 Scholars trained in the social sciences are skilled in conducting interviews and analyzing the resulting data, relying on this knowledge to examine museum programing, visitor experience, and how people behave within particular social spaces (especially in sociological and tourism studies).38 All of these and other approaches strengthen the broader fields of critical museum theory and museum studies, but sometimes there are misunderstandings among scholars based on differing methodologies, understandings of the kinds of primary and secondary sources that should be cited, and assumptions about the tacit knowledge that constitutes authoritative scholarship.

How has the definition of a “museum” changed over time and what is most significant about this change?

19 SA: I should have said from the outset that the “museum” takes so many forms in this country that any general ideas expressed may not be applicable to all. “The museum” is not a realistic frame. Changes to the policies and practices within the Royal Ontario Museum have so many factors that are not shared by small ethnic community centres, for example, or zoos, or gopher collections.39 It is possible to suggest broad changes, such as the evolution from collection to education to participation to well-being amidst pressures of changing funding models, policy, and professionalization as Stephen Weil wrote about American museums.40 But I will offer two observations.

20 Significant, I think, is the influence of museum and heritage theory on the positioning of “cultural heritage” away from “object” or “resource” towards its perception as a consciousness or process of understanding one’s relation to the past. Moving away from tangible to intangible implies a valuation of the past that is complex, layered in a “web of significance.”41 My memory of my granny in its complexity is part of my heritage. My sense of the place where I lived most of my life is also part of my heritage. These sensibilities are not things, but might coalesce within objects or locations as holders of impressions. My life, personally and as part of community, radiates a web of significance. Looked at in this way, the museum is a space for objects that bear an ecology of signification that stretches back in an infinite variety of relationships. This understanding allows for non-European and/or Indigenous perspectives to contribute equally to our understanding of the heritage-ness of anything.

21 Thinking this way also enables us to consider the museum-like activities of any people in a different way. Practices and process become the focus of enquiry in a more cultural studies orientation. This is why I am currently engaged with heritage-making practices by immigrant groups in Canada and the UK. How do people removed from their “home” country draw the past into their new lives and the lives of their children and grandchildren? Migrants leave most tangible heritage behind and might not connect to existing Canadian historical and museum resources. Communities in Canada have long been involved in grassroots museum-making driven by passionate individuals who are thinkers and innovators in their own right. These processes continue today across the country in shopping malls, community centres, and online.42 The importance of these museal activities in social, economic, and political terms is often overlooked.

22 AT: My work explores not so much the definition but rather the function of museums. So, for example, along with sociologist Morgan Poteet, my current research explores paradigmatic shifts affecting museum formation in Canada in the 21st century.43 For example, on 10 August 2008, amendments to the Canada Museums Act allowed Parliament to establish the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR)44 – the first federal museum to be mounted in more than 40 years and one of two such sites to be located outside the national capital region. Just over two years later, on 25 November 2010, more amendments brought about the formation of the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 in Halifax.45 Both signal the reorientation of attention, paid formerly to object and narrative permanence, to current and future social responsibilities. Issues-based museums fundamentally differ from traditional artifacts and material cultural-focused museums in that these “new” museums aim to engage a “universal citizenry.”46 In other words, these institutions endeavor to address socio-political issues and concerns pertinent to a heterogeneous global audience.47 Significantly, over the course of the past decade a wealth of critical scholarly attention has targeted the CMHR with its exploration of human rights and social justice. In 2015, for example, the University of Manitoba Press published The Idea of a Human Rights Museum, the inaugural collection of essays for its newly formed “Human Rights and Social Justice Series.” Edited by Karen Busby, Adam Muller, and Andrew Woolford, the 16 essays explore the formation of the CMHR; they situate it within the wider socio-political global context, drawing comparison between the CMHR and institutions throughout the world that showcase human rights and social justice.48 Why has Pier 21, an institution that formed alongside the CMRH, seemingly escaped such extensive critical consideration?49 Is it not an issues-based museum? Does Pier 21’s operation as a public history museum dedicated to representing “what it was like to immigrate through Pier 21 between 1928 and 1971” render it fundamentally historical in nature and thus preclude it from such analyses?

23 As Poteet and I work towards examining the institutional history of the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, tracing its evolution from an interpretation centre into an immigration museum and federal Crown corporation, we are considering its formation in the context of ongoing immigration policies, practices, and related neo-colonial narratives that reflect the socio-political environment that receives immigrants and refugees. We are interrogating, more specifically, the relationship between and the changing environment for immigration in Canada, including ongoing relations with Indigenous peoples and changes to the refugee system. My research and analysis target the site’s dependence on and exhibitions of volunteerism and community engagement, represented in the site’s published online research materials, marketing, and programing. In so doing, I consider how Pier 21 depends upon and projects the necessity of community volunteerism in order to probe issues bound up in concepts of benevolence and citizenship as well as possibilities for social change. Significantly, this research resulted from my having lived and worked in the east coast and my manuscript research developed from my awareness of sites in and around the region where I grew up.

24 Accordingly, my focus on critical museum studies in and throughout various locals in Canada draws on my moving from place to place as an “itinerant academic.” While such a role is not desirable in the long run, it has afforded me remarkable opportunities to explore sights, sites, settings, and regions and to collaborate with excellent colleagues, friends, and artists. As Ian McKay explains in his 2000 Acadiensis article “A Note on ‘Region’ in Writing the History of Atlantic Canada,” graduate students and emerging scholars often make “pragmatic decisions” by choosing study and research venues located in close proximity to their residence of choice.50 Building on such pragmatism and expanding it to collaborate has, in my experience, led to increasingly sophisticated analyses and publications. It strikes me that collaborative projects inspire greater and more dynamic interdisciplinary work, thereby eschewing, particularly in the field of critical museum studies, any one discipline’s “claim to fame.”

25 HI: As Terry notes, we have just witnessed the opening of the first new national museum in Canada in four decades: the CMHR. Also underway in Winnipeg is the major expansion of the Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG), which is adding a new building that will contain the nation’s first Inuit Art Centre. Ground has not yet been broken, but I have begun working with the WAG on the development of this new initiative that is intended to be a space for the experimental and critical exploration of new museological practices that foreground Indigenous ontologies and epistemologies. Ever since the task force report was published, museums in Canada have been trying to reimagine their engagement with Indigenous peoples – to varying degrees of success, as we have discussed. At the WAG a revised commitment to Indigenous methodologies is made tangible through the establishment an Indigenous-led team of curators and an Indigenous Advisory Circle that will advise and guide our efforts. The circle is being formed at the outset of this collaboration. This is in significant contrast with, for example, the inaugural Indigenous Advisory Committee of the CMHR, on which I served for two years; I began serving approximately one year before the opening, at which point it was too late to recommend any significant changes to museum content until after the opening day. That advisory committee was instead formed to assist the museum in envisioning a way forward as well as to help the museum respond to some of the aforementioned public and scholarly critiques. How can we draw on Indigenous knowledge and worldviews to reshape the WAG, not only in its exhibitions and activities, but in its very mechanics – its mandate, practices and protocols, relationships, responsibilities, aesthetics, and ethics? For me, I am seeking to begin to fundamentally alter the relationship between Indigenous peoples and museums. How can we ensure that the Inuit Art Centre feels, thinks, sounds, and is activated as an Inuit space? How can we take this ethos, and weave it throughout the entire WAG complex, so that the Indigenous peoples of Treaty One, and all the other peoples who have long called that place home, feel engaged, respected, and honoured in the museum? How much of this dream is really possible within the confines of a contemporary art gallery? I and my colleague Dr. Julie Nagam, co-chair of the WAG’s Indigenous Advisory Circle, a curator at the WAG, and associate professor at the University of Winnipeg, as well as the other Indigenous curators with whom we are collaborating, are asking ourselves these difficult questions about museums now.

26 KR: I discuss this question with my undergraduate students every year, and they initially have very firm ideas about what constitutes a museum and are always surprised to find that, if pushed, they also tend to have quite flexible and expansive ideas of what constitutes a museum. So while the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and other governing bodies have defined museums in concrete and useful ways, the term itself is used to describe many things ranging from personal collections, stores, or websites to giant sprawling museum complexes. I do not think we have yet reached saturation of the term “museum” (as happened with curating, leading to David Balzer’s term “curationism”51), but it is definitely getting hazy around the edges. The corollary to a spread in the use of the term is a continued distrust of museums. A perception remains that most museums have not undone or properly accounted for their role in the imposition of colonial structures of power.52 Thus, I see a lot of really productive critical work taking place to grapple with what museums could be and how they still need to change. And I also see people just turning away from museums, looking for other venues. Sometimes this is located in a growing interest in non-mainstream museums – in tiny spaces, micromuseums, and artists making museums. And both of these positions on museums tend to be coupled (in students) with anxiety about the job market. Museums are still objects of study and criticism, but they are also perceived as safe harbours in a difficult job market, as objects of curiosity, and, increasingly, as malleable framing devices; the word museum/gallery can be applied to all sorts of interesting and fascinating independent projects that do not necessary follow the strictures of the museum as defined by ICOM.53

27 SA: People are immensely “culturally active” in very public and networked ways. But what is the place of museums as actors within such networks? Claims of expertise no longer hold automatic authority in this interconnected society. If we think of museums in Canada as storehouses of information and material culture related to knowledge, without institutional understanding of, and adaptation to, this new way of being in the world, this warehouse museum idea is doomed. How can museums think reflexively about new practices that adapt to the new world? For example, maybe central warehouses of objects are no longer the answer and instead artifacts should be preserved in infinite networks of families or communities – devolved networks of care, knowing, and passion.54

28 At the same time, museums are also seen as unique spaces for face-to-face encounters with material culture and other, breathing human beings.55 The disappearance of “public” space in society has been an ongoing issue in communication and cultural studies as both real spaces and online communities are increasingly controlled by “private” interests.56 But the importance of the first-hand embodied and affective experience of the world and its people is a central concern not just in museum studies but also in much of sociological, cultural policy, and cultural studies research, especially in the debates around the value of culture.57 Questions about the “publicness” of institutions embody those concerns. But operating as public spaces is not an easy task, and instead invites the complexity and conflict that characterize any human interaction. How to commit to face-to-face publicness involves dealing with issues of timeliness, intimacy, mutuality, and risk, which creates thorny problems with institutional barriers that have been theorized, but infrequently solved. 58

29 LM: I consider the museum as a process of establishing relationships and identities rather than a unified entity or single place, having arrived at this understanding by means of historical research.59 While working in the archives at the New Brunswick Museum, I realized that 19th- and early-20th-century discussions about what the museum in Saint John should or could be – by members of the Natural History Society of New Brunswick, founded in 1862 – never aligned with the collections or displays they produced; the members of the group were not satisfied with their museum, endlessly trading local specimens for international objects (which were then re-traded), reorganizing the installations, creating temporary displays, and fundraising for a new building. Researchers at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford have similarly argued that the museum is “the least moored, stable, or pre-constituted entity imaginable.”60 Instead of providing a linear history of how the New Brunswick Museum was established, I examined how meanings and identities were negotiated in relation to the museum, analyzing the links made with provincial schools, the government, international natural history societies, and, eventually, patrons. This way of thinking highlighted the museum as an idea that encouraged such performances as the Oriental Exhibition of 1924, when members of the Women’s Auxiliary, who were largely white and middle class, staged a temporary take-over of the display spaces in Saint John by dressing in Asian costume to serve tea and cake to visitors. The fundraising event empowered the women who were otherwise excluded from managing the museum’s displays, even as their subversive act relied on the appropriation of Asian culture. This Oriental Exhibition is just one example of how the museum has promoted the contestation of meaning in complex ways that cannot simply be either decried or celebrated.61

30 This conversation between Ashley, Igloliorte, Robertson, Terry, and myself provides a mixed review of critical museum theory/museum studies in Canada, indicating that even as curators, staff, administrators, and scholars move towards decolonizing museum practices and making museums more inclusive such efforts are often hindered by a lack of resources. Funding cuts by the Harper government continue to have a negative effect on the cultural sector, and the recent increase in funding opportunities, including monies devoted to celebrating Canada’s 150th “birthday,” can be constraining – reinforcing the colonizing legacy of the conception and purpose of many museums. At the same time, researchers in Canada remain “skeptically optimistic” (to paraphrase Igloliorte), inspired by the important interventions led by Indigenous scholars, artists, and activists in collaboration with settler scholars. The recommendations made by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada have not yet had a major impact on some large, urban, and national museums, but smaller galleries and independent curators are leading the way by providing innovative exhibitions and programing. In keeping with the increasing importance of smaller venues, scholars of critical museum theory/museum studies are now investigating rural, independent, and seemingly marginal museums that defy the traditional definition of museums as places exclusively devoted to the preservation and display of authorized heritage. This expansive scholarship is part of a broader international trend that is moving beyond national narratives and urban centres to find the future of the museum. It is our hope that this conversation has highlighted the hard questions that still need to be asked of museums, even as it promotes the rich possibilities of the ongoing interdisciplinary research in critical museum theory/museum studies and draws attention to the particular challenges faced by the museum community in Canada.

with contributions from

SUSAN ASHLEY, HEATHER IGLOLIORTE,

KIRSTY ROBERTSON, and ANDREA TERRY