Articles

How to Win Friends and Trade with People:

Southern Inuit, George Cartwright, and Labrador Households, 1763 to 1809

British and Southern Inuit traders in late-18th-century Labrador embedded the fisheries and fur trade in their social relations through transculturation. Specifically, British traders such as Capt. George Cartwright changed how they organized their friendships and households, as did Attuiock, an Inuit angakkuq or shaman. Cartwright’s approach evolved from using “luxury” to try to regulate Inuit workers and traders to also including Inuit traders and workers in his friendships and households. Even if Cartwright misunderstood what this meant to his Inuit partners, this approach made sense to them, too, as they were, after all, also agents of this transculturation.

Les commerçants de fourrures britanniques et Inuit du Sud intégrèrent la pêche et la traite des fourrures dans leurs relations sociales par transculturation dans le Labrador de la fin du 18e siècle. Plus précisément, les commerçants britanniques, tel le capitaine George Cartwright, transformèrent leur façon d’organiser leurs amitiés et leur foyer, comme le fit Attuiock, un angakkuk ou shaman inuit. Délaissant le recours aux articles de « luxe » pour tenter de régir les travailleurs et les commerçants inuits, Cartwright s’employa aussi à les inclure parmi ses amis et dans son ménage. Même si Cartwright ne comprenait pas bien ce que cela signifiait pour ses partenaires inuits, cette approche leur semblait logique à eux aussi car, après tout, ils étaient également des agents de cette transculturation.

1 ENGLISH TRADER GEORGE CARTWRIGHT CLAIMED that he had done more than anyone else to open peaceful Inuit-British trade in Labrador. He said this even though other French and British merchants had preceded Cartwright’s 1770 arrival in Labrador and even though Inuit negotiators had already formed the Inuit Peace and Friendship Treaty with Newfoundland Governor Hugh Palliser in 1765. Yet Cartwright does appear to have traded more successfully with his Inuit partners than his predecessors had done. Why was this? Similar to other merchants, Cartwright expanded European fisheries and the trade in furs, oil, and whalebone into Inuit traditional territory. In addition, he believed that British merchants should dominate their Inuit trading partners although, when he attempted to put this belief into practice, his Inuit trading partners resisted him. Eventually, Cartwright adopted Southern Inuit people as his friends and members of his household. Moreover, he adapted himself to Inuit norms of friendships and households.

2 This moment in the ethnographic and economic history of Labrador had broader implications. Soon after Cartwright’s arrival Inuit women who worked for Cartwright gave birth to children fathered by men who worked for Cartwright. Furthermore, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) later sought advice from Cartwright about how to promote trade with Inuit in the Eastern Arctic. Economic historians of the Hudson Bay trade argue that non-commercial behaviours had disappeared soon after the fur trade began there. Yet, in late-18th-century Labrador, Cartwright claimed that his Inuit trading partners had “sentiments of real friendship” for him, as he put it in a letter to Secretary of the Colonies Lord Dartmouth.1

3 This revises the history of Labrador’s contact zones: these years of early English posts that preceded métissage can be described as a time of transculturation, when both Inuit and British people influenced each other.2 This is an alternative to either describing Southern Inuit as acculturated or describing English posts as entirely separate from Inuit habitation.3 Specifically, George Cartwright and his Inuit trading partners such as Attuoick and Shuglawina mixed and remixed their practices of trade, friendship, and households to include Inuit people in British friendships and households and to include British people in Inuit trading networks. They borrowed and re-borrowed from each other in this way at least in part to help regulate labour and facilitate trade. In other words, both British and Inuit traders embedded their economic exchanges with each other within social relations.

4 This article has three parts. First, it looks at British ideas about labour supply and how British proponents of the fisheries and Inuit trade thought about using consumer goods to encourage Inuit and Innu Labradorians to work in the fisheries and fur trade. Second, it explores conceptions of friendship, specifically how George Cartwright drew on ideas of friendship as a response to the failures of early British posts in Labrador. Finally, it looks at households and how George Cartwright and other British traders in Labrador adapted their households to Labrador Inuit households and trading networks.

5 The first part of this article, about luxury, considers how English proponents of trade disputed how consumption correlated with labour supply in the fur trades. Advocates for creating British posts in Labrador held an idea in common with some Hudson’s Bay Company traders that if they introduced their Indigenous trading partners to luxury then this would create “imaginary wants” that would spur Inuit people to collect, process, and transport more commodities for trade. Yet opening this trade was difficult, especially in Labrador where there were many murders and other acts of violence between British and Inuit people during the 1760s. Some British commentators proposed assimilating Labrador’s Inuit, even though the British governors of Quebec and Newfoundland could not regulate the Labrador coast effectively. Furthermore, Labrador’s Inuit inhabitants were, in the eyes of British commentators and governors, a seafaring nation. This is a puzzle, for in other settings British merchants and the navy coerced maritime peoples into working for them using debt, indenture, slavery, and impressment. Yet those institutions do not appear to have been widespread among Inuit workers in Labrador during the four decades after the fall of Quebec in 1759.

6 The second part of this article, about friendship, notes how George Cartwright and other Labrador merchants after 1763 discovered that simply replicating the fishing posts of the island of Newfoundland on the mainland of Labrador was not enough to succeed in Labrador. The first British posts in Labrador were short-lived because the navy promoted a ship fishery there instead of a residential fishery, merchants did not know how to exploit winter resources such as seals, and because English crews and Inuit inhabitants raided each other, including Inuit parties taking English property and English crews massacring Inuit people. After these early posts failed, Cartwright founded his first station on the coast in 1770. Cartwright was an unusual Labrador merchant if only for publishing a 1,100-page journal that documented his time in Labrador. In this journal and other documents, he advocated thinking about Inuit as friends who shared economic interests with British traders and who traders should influence. When he put his theories into practice, however, his Inuit trading partners resisted him. The family of Attuiock illustrates this best. Cartwright’s bids for authority over the family of Attuiock were frustrated in part because Cartwright misunderstood this family’s expressions of the fearful emotion of ilira. These Inuit partners appear to have seen Cartwright’s actions differently than Cartwright himself claimed they did, for they acted as if they were wary of him.

7 The third part of this article examines how Cartwright adapted the organization of his household to the organization of Labrador Inuit winter households of the kindred group or ilarit. His household, similar to many other English households, comprised a changing assortment of dependents and visitors. Cartwright’s Labrador household, which included English and Irish tradesmen and servants, also came to include Inuit women and children. This experience was not confined to Cartwright’s posts. Moravian Brethren missionaries, who settled in northern Labrador after Cartwright had settled in the south, used a language of friendship and kinship to talk about proselytizing and trading with Inuit people. By the mid-1770s Inuit mothers in southern Labrador gave birth to children with English and Irish fathers, including fathers who were servants working for Cartwright. After Cartwright departed Labrador in 1786, the merchant partnership of John Slade and Company traded with Inuit partners and the early families of southeastern Labrador continued to grow when more Inuit mothers gave birth to children with European fathers.

8 In short, early British-Inuit trade in Labrador was embedded in pre-existing patterns of Inuit and English friendships and families. This argument supports substantivist arguments that the fur trade was, as Karl Polanyi once wrote, “embedded in social relations” such as political alliances, gift-giving, spiritual relationships between humans and animals, and how fur-trading companies administered their organizations.4 These substantivist arguments differ from formalist arguments that described the fur trade using formal economic theory, arguing, for example, that trappers and traders were utility maximizers who brought in more furs when prices rose and not fewer furs.5 As we shall see, norms about friendship and kinship suffused both British and Inuit trade in Labrador – even when British commentators of the period wrote about labour supply and consumption using words such as “industry” and “luxury.”

9 British traders and governors believed that “luxury” would stimulate Inuit “industry” or labour supply. The British of Newfoundland and Quebec had a profoundly incorrect notion that, as Quebec Governor James Murray put it in 1766, “all savage people are naturally indolent and calculate only for the present moment.”6 George Cartwright and other advocates of trade in Labrador planned to introduce Inuit and Innu to manufactured goods, especially imported goods. What he and others called “luxury” would create “new wants” among Inuit and Innu people that would spur them to obtain, prepare, and trade more furs, whalebone, and seal oil. In Cartwright’s words, “Trade always creates luxury; luxury, wants; and wants, create industry.”7 Others shared these views. Then-Lieutenant (later Sir) Roger Curtis of the Royal Navy expressed the same idea in a 1772 letter to the Secretary of the Colonies:

In Labrador, the little luxuries merchants traded were generally everyday goods such as tobacco, useful metal wares, and glass beads.9

10 Though smaller in scale than the Hudson Bay Company, the merchant partnerships of Labrador were similar to the HBC in that the HBC also hoped to regulate its Indigenous trading partners.10 One of the several arguments the Hudson Bay Company used to defend its monopoly was the claim that the HBC needed this monopoly as a way to regulate the Indigenous labour supply as company officials claimed that this labour supply did not respond to changes in fur prices.11 Yet the HBC monopoly had opponents, including one Arthur Dobbs whose 20-year campaign to break this HBC monopoly culminated in the 1749 House of Commons Committee on Hudson’s Bay. At the committee, some former employees of the HBC testified that they thought higher prices would increase the volume of trade with Indigenous people in Hudson Bay and not decrease it.12 They believed Indigenous traders were utility maximizers. When the committee examined merchants from London, Bristol, and Liverpool as well as the provost of Glasgow, those witnesses favoured opening up the Hudson Bay trade. Among these witnesses, Liverpool merchant John Hardman argued for regulating the fur trade with “imaginary wants” in even more detail that George Cartwright and Roger Lucas later did:

Hardman believed in this power of imaginary wants. Evidence from Labrador and elsewhere suggests that his view of the fur trade was correct, that an increased demand for consumer goods by households spurred an increase in market-oriented production by these households.14 Even before 1763 in Labrador, Inuit “middleman” entrepreneurs had already specialized in the north-south trade of whalebone, wood, and French and Basque manufactured goods. These entrepreneurs lived in communal households of multiple families. Arguably, these were founded when this trade had concentrated wealth and power in their hands. 15 Yet this is not a sufficient explanation of how trade originated in Labrador, given the violence on the coast during the 1760s. In particular, it does not explain how – with the coast on the verge of war – peaceful trade began in the first place.

11 Amid the violence of Labrador in the 1760s Inuit traders were wary of British and British American visitors alike. According to the Moravian missionaries Jens Haven and Christian Drachart, who encountered Inuit people in 1765 and 1770, these people were not fond of the Europeans on the coast, especially when it came to the “many irregularities with respect to their women” by sailors and the “inhumanities” and “outrages” of British Americans who stole from, assaulted, and killed Inuit people.16 British visitors were fearful of Inuit people, too. As Lt. Curtis wrote to the Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1772, “At that time they [Inuit] were believed to be a more savage, ferocious, evil people than perhaps they really were. The Merchants dreaded the Loss of their Craft [fishing gear], & the Servants considered their Lives to be in danger.”17 Danger seemed very present to everyone on the coast.

12 Britain could scarcely govern coastal Labrador. New France had administered French posts there until 1759-60. In 1763 Britain annexed Labrador to the naval government of Newfoundland and, in August 1765, the Southern Inuit gathered at Cape Charles with Governor Palliser and concluded negotiating the Labrador Inuit Treaty, a peace and friendship treaty.18 Yet, as John Reid explains, British “peace and friendship” could be two-sided: nations who had not consented to “peace and friendship” could be categorized as “enemies.”19 Moreover, in 1772, seven years after this treaty relationship began, Lt. Curtis advised the secretary of state for the colonies that Labrador’s northern “Esquimaux must either be civilized or extirpated. Perhaps the latter would be most expeditious, but Justice + Humanity directs us to the other . . . . In short they must either not be or be Friends with us.”20 But Curtis overestimated British efficacy in Labrador. The Quebec Act (1774) transferred Labrador to the British government of Quebec effective in 1775, yet Quebec’s laws were unclear and largely ineffective so far from the capital. In Labrador the Royal Navy continued to regulate the fishery, and the Newfoundland Act (1809) re-annexed Labrador to Newfoundland.21 These hopes to assimilate Labrador Inuit by policy or law were impracticable.

13 An alternative to assimilation could have been indentured labour. After all, English observers thought of Labrador’s Inuit as “really seafaring men” who were not “real Indians.” In one court case during Quebec’s British regime, an attorney argued for the distinction this way: on the one hand there were “les vrais Sauvages,” who were the Innu of the woodlands and, on the other hand, there were “les Eskimaux qui ne sont pas des chasseurs de pelleteries dans les bois mais bien des gens de mer des pêcheurs de loup marin et baleine et qui sont toujours à l’eau froide ou sur les glaces de la mer.”22 In his 1772 letter, Lt. Curtis had called the Inuit “a maritime nation,” and he did so again in a 1774 article for readers of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. The Inuit were proficient navigators who used kayaks, umiaks, and shallops. Curtis commented that Inuit people were “almost ever in their Canoes” and “navigate their Shallops without a compass in their thickest Foggs & are very good Coasters.”23 Governor Hugh Palliser saw this as an opportunity. It was his “opinion that those people who have hitherto been so much dreaded, may in a very short time by kind treatment and fair dealing, be made exceeding usefull people to His Majesty’s Subjects, they are expert whale catchers and naturally fishers, are almost amphibious creatures, living constantly on little Islands along the coast, and subsist almost wholly upon fish.”24 Navy logbooks from Labrador record dozens of waterborne encounters with Inuit during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and the navy used Inuit pilots as well.25 Although few British visitors saw how the Inuit also used inland Labrador,26 British observers did see that the Inuit were hunters of marine wildlife. They noted that when trading, gift giving, and salvaging goods, Inuit people were interested most of all in metal wares and manufactured marine gear including ropes, sailcloth, fishhooks, ulublades, and boats (especially “battoes, and shallops”).27 Labrador’s Inuit may not have been deep-sea sailors, but they lived on the shores of the ocean, used maritime resources, and had maritime skills.

14 These were skills that the naval officials and British merchants sought, so it is surprising that British masters do not appear to have coerced Inuit maritime labour. Other British and British American merchants, shipmasters, and crimps used debt, indentures, and slavery to regulate boatmen, fishermen, whalers, and merchant seamen, especially when these workers were Africans, African Americans, or Indigenous North Americans who might find more opportunity at sea than amid settler society on shore.28 In Newfoundland, masters used credit to regulate labour in the fisheries. In the wage and lien system, merchants outfitted fishing crews who then sold their catches back to the merchants. In the truck system masters paid wages in credit that was tied to purchasing goods from masters at prices that the masters set. This could reduce real wages below nominal wages, to the dismay of servants who found their earnings seemed to vanish when clerks reckoned their accounts. These servants could even find they had become debt peons, although it seems this abuse of truck by merchants was not widespread in the Newfoundland fisheries. Eventually, credit did become a source of bondage for Inuit who traded with Moravians in the north.29 But the question remains: given that in 1765 Governor Palliser had written that the Labrador coast, “with respect to the Indians is kept in a state of War,” how did Inuit-British trade and employment originate?

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 115 After 1763 British merchants moved into Southern Labrador and Quebec’s Lower North Shore, a region that Inuit occupied and used year-round.30 Prior to the British regime, New France concessions and seigneuries operated by French merchants based in Quebec had been located mostly to the west of Blanc Sablon. During the British regime, British merchants based in Quebec, such as John Lymburner, began to operate posts in the Blanc Sablon area while the Quebec-based merchants Daniel Bayne and William Brymer gained the first British grant of a fishing post in the Straight of Belle Isle region, located at Cape Charles. Bayne and Brymer held this post from 1763 until 1765, when Palliser’s naval government expelled them to suppress the sedentary fishery of year-round posts and instead extend to Labrador the free and migratory ship fishery of Newfoundland without year-to-year rights in posts. Later, in 1773, this Newfoundland policy was amended to permit year-to-year rights in posts in Labrador that supported sealing and salmoning merchants, who needed to customize their nets according to the topography of each post and who overwintered to take advantage of Labrador’s year-round economy of seasonal resources.31 After this expulsion of Bayne and Brymer, the British merchants Nicholas Darby and Michael Muller took over this site and built several additional posts nearby with crews from England and Ireland.32

16 Darby’s posts struggled due to not using resources year-round, and Inuit attacks drove him from the coast. Darby had a crew of 150 in his first year, but none agreed to overwinter on the coast. After the fishing season was over and Darby’s crew had departed, Inuit parties disassembled his premises, perhaps to salvage metal from the buildings similar to how Inuit traders salvaged metal from buildings elsewhere on the coast. The next year some of Darby’s crew of 180 overwintered on the site, but they were not productive because they did not know how to fish for seals during the winter. Darby returned a third time in 1767 with a crew of 160. In October of that year, as winter approached, an Inuit party raided Darby, likely in retaliation for British and British-American attacks. The raiding party killed three of Darby’s crewmembers, drove the rest of the crew from the Cape Charles post, captured two boats, and set fire to the premises. In retaliation, British marines led by Francis Lucas massacred up to 24 Inuit and captured nine Inuit women and children (including the woman named Mikak). Lucas took these captives to York Fort, a blockhouse garrisoned by marines at Chateau, near Cape Charles, then to St. John’s. From there he took three of the captives to England: Mikak, her son named Tutuac, and an orphaned boy named Karpik. Mikak became one of the first of Labrador’s intermediaries between the British and the Inuit: Inuit who navigated English culture or English who navigated Inuit culture. She appears to have influenced the Moravian grant at Nain by speaking for it in both England and Labrador and then by piloting a vessel of Moravian Brethren missionaries to that location.33 Darby left the Cape Charles site, and merchant interest in Labrador abated except for one merchant house with posts protected by the York Fort blockhouse. The earliest British stations in Labrador had floundered.

17 In 1770 Cartwright established a sealing and trading post at Cape Charles, on Nicholas Darby’s former site. Cartwright was in a partnership with Thomas Perkins, Jeremiah Coghlin, and Francis Lucas, but of the four he was the only merchant to inhabit the post. Cartwright brought a retinue of various tradesmen and their wives, indentured servants, his companion and housekeeper Mrs. Selby, and his servant Charles Atkinson.34 Advising other merchants on who to bring with them to Labrador, Cartwright listed sealers, boats-masters, midshipmen, boatbuilders, joiners, basket makers, coopers, sawyers, furriers, bricklayers, tailors, shoemakers, tinmen and tinsmiths, leather-dressers who prepared hides, and “Women Servants, who can Cook, Wash, and Milk etc.” Cartwright added: “The Women should be good-tempered, and not too delicate.”35

18 Fairly or not, Cartwright claimed credit for ending these hostilities of Inuit and British in Labrador and for advancing British posts in Labrador more than anyone before him had done. 36 Cartwright’s partner Lucas brought the family of Attuiock from Arvertok, the Inuit settlement that was adjacent to present-day Hopedale, to meet Cartwright at his Cape Charles post about 500 kilometres to the south. Of this encounter during early October 1770, Cartwright wrote:

19 Occasionally, Cartwright stayed in a tent close to Inuit encampments. He adopted Inuit technologies – including sealskin boots and clothing, dog-pulled komatik sleds, and sod houses – technologies that other posts in Labrador and northern Newfoundland also adopted.38 He traded and loaned to his Inuit friends firearms, shot, and powder during years when other English merchants or Moravians missionaries did not do so.39 The only Labrador merchants with similar engagement with Inuit life were the Moravian missionaries in northern Labrador, who founded their mission at Nain after Cartwright had founded his Cape Charles post.

20 In many ways Cartwright was an atypical Labrador merchant. Most of the Labrador merchants were natives of the English West Country, but Cartwright came from a landed family of the East Midlands where his father had been the high sheriff of Nottingham. At the end of an army career, George Cartwright was brevetted from lieutenant to captain then went on half-pay; his brother, Lt. John Cartwright of the Royal Navy, introduced George Cartwright to Newfoundland.40 And despite his success befriending Inuit people, Cartwright was a relatively small trader who struggled to be profitable. The largest merchant partnership on the Labrador coast was Noble and Pinson, who employed up to 300 servants at once and operated over a period of 50 years. By comparison, Cartwright’s various partnerships employed up to 70 workers at any time, but sometimes as few as five, and his ventures appear to have taken place over a period of between 16 and 22 years. His partners left him short-supplied, several fires damaged or destroyed his buildings, his partnership lost a vessel to a shipwreck, the merchants Noble and Pinson dispossessed him of his best posts, privateers raided him during the American Revolution, and he went bankrupt in 1784. When compared to merchants in Newfoundland, Cartwright’s suggested prices for furs were low.41 These were some of the respects in which Cartwright was an outsider among England’s Labrador merchants.

21 Cartwright wrote more about Southern Labrador’s contact zone than anyone else of his time. Chief among Cartwright’s texts was his published journal of 1,100 pages that describes his enterprises in Labrador. Cartwright edited this document himself and published it by subscription from Nottinghamshire as A Journal of Transactions and Events during Sixteen Years on the Coast of Labrador (1792); there is no handwritten original known to have survived. A spirit of improvement animated this Enlightenment travelogue, with passages that variously resembled a merchant’s aide-memoire, a sportsman’s game book, a gentleman amateur’s natural history, and a factor’s account among other genres.42 In the journal and his many other writings, Cartwright portrayed Labrador as a sportsman’s paradise that also could be commercially exploited by overwintering at posts that had diversified industries based on the seasonal availability of natural resources. He also advocated establishing British political administration there, appointing himself to public office, and granting property rights in fishing posts, among other “improvements.”43 His vision for Labrador was to adapt the Newfoundland fisheries to Labrador conditions.

22 His journal shows that Cartwright’s changing ideas about friendship and family shaped how he acted toward Inuit workers and traders. Cartwright called Inuit men his friends and he called Inuit women and Inuit children his family. Cartwright, for instance, came to count among those who he named as his friends an Inuit man, named Attuiock, who was an angakkuq (shaman). The other people who Cartwright named as his friends were merchants, masters of servants, or holders of a military or public office – men similar to Cartwright himself. Cartwright associated Attuiock with other men among these ranks.

23 At first friendship for Cartwright meant sharing economic interests. Among 18th-century English gentlemen and merchants, friendship was a relationship of reciprocal usefulness between partners who had interests in each other’s interests. 44

24 This was exactly how Cartwright described his friendship with Attuiock when writing a letter to his family in England during his first year on the coast: “Through the means of the Indian [Inuit] family which wintered with me my interest is pretty well established amongst those savages.”45 This was part of an economic strategy for Cartwright. As part of his advice for prospective merchants in the Inuit trade, Cartwright advised that “so soon as you can discover the leading men, attach them to your interest, by associating freely with them and admitting them to your table at times.”46 Cartwright pitched his tent by Inuit camps. He gave gifts to his Inuit friends and looked to participate in their social lives. He gave boats to Attuiock and wrestled, danced, and played with visiting Inuit traders and guests the way Inuit people did with their own friends.47 Reminiscing on this, he wrote in verse:

No Broils, nor Feuds, but all is sport and play

My Will’s their Law, and Justice is my Will;

Thus Friends we always were, and Friends are still.48

The point of gaining this influence was to increase trade, as Cartwright explained elsewhere in his advice to prospective merchants:

Cartwright put this into practice by flooding his Inuit friends with friendly gestures. He learned to speak some Labrador Inuttut and brought an Inuit boy named Noozelliack to England to become an interpreter, although the boy died of smallpox while in England. Cartwright dined and hunted with Inuit men, similar to how he dined with his British friends. These Inuit included Tooklavinia, Attuiock’s youngest brother, and Shuglawina, who was a headman (angajuqqaaq).50 Cartwright described Shuglawina as “the chief’ and “the chief of the these tribes,” while Shuglawina was another of Cartwright’s friends in trade.51 Whether Shuglawina, Attuiock, and other Inuit traders realized it or not, they fit into Cartwright’s model of friendship between English men who had interests in each other’s interests.

25 Cartwright’s Inuit friends may not have seen this because Cartwright yoked violence to his purported benevolence. This resembled how Cartwright attempted to govern his servants. He attempted to punish Inuit people in a manner similar to how he punished workers – by scolding them and issuing beatings followed later by lenity followed later by escalated beatings. Similar to his treatment of his servants, he also provided medical treatment to Inuit people, adjudicated Inuit domestic disputes, and regaled Inuit people with gifts of food and drink. In a master-servant relationship, these regales were sources of power and also symbols of authority redolent of how crews negotiated with masters for food, shelter, clothing, wages, and gentle usage. A master in turn negotiated with workers, whose resistance could stymie him in ways limited only by their own ingenuity including working slowly or fighting him. In addition, both law and popular customs constrained how a master could exercise his claim to authority. These popular customs of the master-servant relationship can be seen as instances when culture mediated class relations or, alternatively, as instances when popular culture revealed the underlying class relations between creditor merchants and debtor fishermen.52

26 In this case of Cartwright and his Inuit friends, his regaling of Inuit people was a claim to authority; but his Inuit friends and family contested that claim. When Cartwright acted as if his Inuit friends were his servants, for instance, they resisted Cartwright’s actions and thus frustrated Cartwright’s epectations for their deference. These Inuit trading partners had their own frustrated expectations about appropriate conduct, and when Cartwright attempted to punish them they did not interpret his actions the way he had hoped that they would. When he hit Inuit men they fought back, turning supposed beatings into brawls. He had desired deference, but struggled to attain it. Cartwright advised prospective merchants to be aloof with Indigenous people: “If they displease you talk to them cooly & firmly but never fly into a passion with them.” He did not, however, always heed his own counsel, and he berated Inuit traders for driving hard bargains. On other occasions Cartwright refused to do business when he believed that Inuit traders had cheated him. He physically attacked one man who he believed had stolen from him, claiming to his readers that this was a justifiable retaliation: “Having reproved him in a very angry tone for his behaviour, I gave him a few strokes. He instantly made resistance, when catching him in my arms, I gave him a cross-buttock (a method of throwing unknown to them) and pitched him with great force headlong out of my tent.” After these instances of conflict, Cartwright refused the gifts his Inuit trading partners offered to reconcile with him. Cartwright explained to his readers that this was his attempt to dominate Inuit people by rejecting gifts that came from those whom he believed to be his subordinates.53 The actions of Cartwright’s Inuit trading partners suggest that they did not see him in the way that he presented himself to his English readers.

27 As it happens, Cartwright misread the resistance of his Inuit friends. When Cartwright looked at Inuit people, he saw faces smiling back at him and he loved it as he thought this was a sign of their devotion to him. This was a misunderstanding. As Coll Thrush argues, this smiling and agreeableness were expressions of the emotion called ilira in Inuktitut. This is a feeling of shyness, embarrassment, awe, nervousness, fear, or hostility. Unpredictable, inscrutable people cause one to feel ilira, especially when these people are prone to scolding or criticizing others. Inuit people have often said that ilira describes the feelings evoked by interacting with qallunaat (white people, especially English speakers). Qallunaat often misunderstood expressions of ilira to mean deference, agreement, and compliance.54 These contrasting experiences of how Inuit people expressed ilira and how Qallunaat interpreted it are suggested by how Cartwright wrote of his Inuit friends. During 1770-1771 he wrote: “It was sometime before I could bring the Equimaux Indians left with me by Lucas to tollerable behaviour, or get the better of the dread they had that I should murder them on [every] slight occasion; but I fancy now they have as great regard for, and as little dread of me as their own country people, ‘tho’ at the same time they are in great awe and carefully avoid doing any thing which they think will offend me.” 55 Likewise, describing the outcomes of his friendship, Cartwright wrote of camping adjacent to his Inuit trading partners: “I depended on the great provision of friendship which they had made and was not deceived; for they behaved very well and did nothing without my consent.”56 The belligerence of Cartwright was not the Inuit way. An Inuk may have described Cartwright’s beatings and scoldings as ningaq (anger and physical aggression) and huaq (verbal aggression) that came from someone who did not act in the restrained, inummarik manner of an authentic Inuit person, who was guided by the cerebral faculties called isuma.57 Cartwright had hoped for deference from his Inuit partners, but this was not enough to make him superordinate in their eyes.

28 Other traders in Labrador also described trade as friendship. During the French regime, French merchants had traded on credit and supported the widows and orphans of their Indigenous trading partners. According to the later British Governor of Quebec James Murray, “This created the strongest tyes of gratitude, friendship & interest in both partys.” Murray reported that this “friendly intercourse” and “fatherly treatment” had created durable attachment of Inuit traders to French merchants, “whom they considered as their Father friend[s] and benefactor[s].”58 In Southern Labrador, some British merchants followed this example during the 1760s, advancing payment for the next year’s furs in a system of consignment that the Hudson’s Bay Company sometimes attempted in the Hudson Bay trade.59 In Northern Labrador, the Moravians traded with Inuit at their missions. These missionaries were Protestant pietists based in Bohemia. The British government had issued a grant for them to found a mission and trading station at Nain (Nunajnguk), to the north of Hamilton Inlet, where they had arrived in 1771.60 The Moravians attempted to settle, convert, and trade with Inuit people in relationships that they called amity and brotherhood, another language of friendship and kinship. For instance, Jens Haven was a missionary who had learned to speak the Inuit language in Greenland. When he met Labrador Inuit at Quirpon on the tip of Newfoundland’s Northern Peninsula in 1764 he reported that he had told them that he was their “very good friend.” When he returned in 1770 to settle in Labrador, he again insisted on his friendship. Although Moravians thought about credit as a financial transaction – for instance, Haven gave a receipt of payment when purchasing whalebone – they benefitted from how their Inuit partners thought of credit as a reciprocal relationship that created obligations for both the creditor and the debtor. James Hiller argues that these Moravians resembled Inuit entrepreneur-traders in that they mediated the trade in manufactured goods from Europe to Inuit traders, as well as being political and religious intermediaries between Inuit people and both British government and divinity.61 In this way, others on the coast of Labrador also spread this type of friendship, household organization, and trade.

29 Inuit traders, for their part, related to Cartwright through the extended kindred group or the ilarit, which was the core of winter household groups. Kin groups and voluntary associations that were similar to kin groups organized Inuit society before European contact and during early encounters. During the 20th century, ethnographers of Labrador and the Nunavik Inuit described the extended kindred ilarit as a group of family groups, tending to be patrilineal, based on pre-settlement camp groups, and with various economic and social functions. Members of an ilarit were generally connected through marriage, and these marriages tended to be endogamous within an ilarit.62 The eldest male of a family usually led these groups. Cartwright began to engage this organization of Inuit leadership, authority, and winter habitation when Lucas brought the extended family of Attuiock to trade with Cartwright at Cape Charles in the hopes of attracting other Inuit traders there. The group spent the winter of 1770-1771 near Cartwright’s station, including Attuiock himself, his two wives, three children, his youngest brother Tooklavinia and Tooklavinia’s family, Attuiock’s nephew Ettuiock, and a woman who Cartwright called Attuiock’s “maidservant.” This was an extended family of entrepreneur-traders in Labrador’s pre-existing north-south trade.63

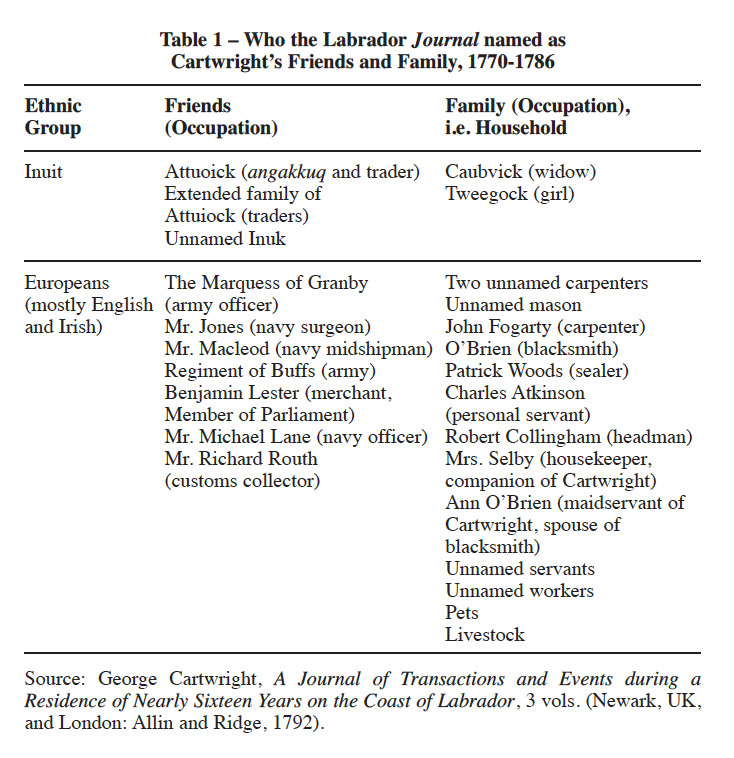

30 Cartwright later incorporated Inuit people into the household of his own family. “Family” in the usage of Cartwright and other Englishmen of his time, meant a household that included dependents. Naomi Tadmor argues English families were permeable households and, when English people spoke of family, most often “what they had in mind was a household unit, which could comprise related and non-related dependents living together under the authority of a householder: it might include a spouse, children, other relations, servants and apprentices, boarders, sojourners, or only some of these.”64 Cartwright came to include Inuit women and children in his family, along with many tradesmen, male and female servants, and his housekeeper and companion, Mrs. Selby (see Table 1).

31 His view of the family suggests that their numbers also included others who he did not specifically name as his family. For instance, later Cartwright incorporated at least four other Inuit into his household: a boy named Jack, a woman named Cattook, a woman named Tweegock, and the daughter of Tweegock (named Phillis). Cartwright described these Inuit people as “my household servants,” and occasionally called Tweegock his slave. Cattook worked as a housekeeper, and Jack’s work as a furrier closely resembled the work of Cartwright’s late furrier and personal servant Charles Atkinson.65 George Cartwright’s family was not just a household, but a houseful of overlapping family groups who worked together.66

Display large image of Table 1Source: George Cartwright, A Journal of Transactions and Events during a

Residence of Nearly Sixteen Years on the Coast of Labrador, 3 vols. (Newark, UK,

and London: Allin and Ridge, 1792).

Display large image of Table 1Source: George Cartwright, A Journal of Transactions and Events during a

Residence of Nearly Sixteen Years on the Coast of Labrador, 3 vols. (Newark, UK,

and London: Allin and Ridge, 1792).

32 And so it turns out that the women who worked at Cartwright’s posts were often Inuit women. Inuit women were co-producers in Labrador’s fisheries and fur trade, just as Irish women were “vital co-producers” in the Newfoundland fisheries.67 When traders brought half-moon metal blades to Labrador, Inuit women used these as multi-purpose ulu knives that are ideal for preparing skins. Missionary Christian Drachart described these as “such Knives as the Shoe-makers use to cut their leather.” With ulu knives, needles, and other tools, Inuit women used caribou and seals to make clothing, tents, and boats shells. Cartwright almost never acknowledged this, but he did write “if an Eskimeau Woman cannot be procured to put on the Seal-skins covering, Painted Canvass must be substituted” on kayaks. In addition, Inuit women in Labrador also worked in what a Moravian missionary called “Domestic Bussiness.”68 The work of these Inuit women made Cartwright’s stations run.

Display large image of Figure 2

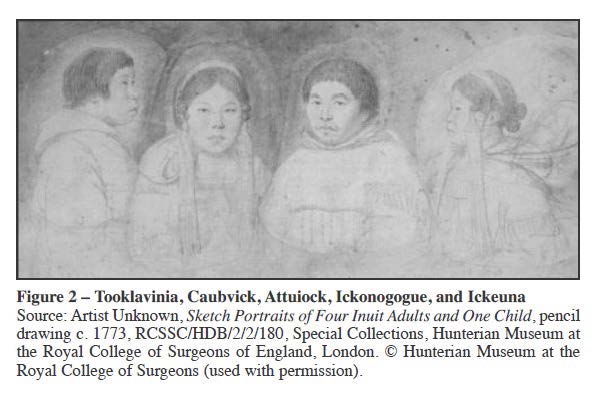

Display large image of Figure 233 Cartwright had mixed success understanding Inuit families and households. In 1772-1773, Cartwright brought some of the family of Attuiock to England: Attuiock himself, Ickongoque and her daughter Ickeuna, Tooklavinia, and Caubvick (see Figure 2).69 Cartwright’s avowed agenda was to awe them with the military power, urban architecture, country estates, and the vast population of Georgian England. His efforts could have been summarized using Governor Hugh Palliser’s instructions to Moravian missionaries meeting Labrador Inuit 1765: “To give them [Inuit] a proper Idea of his Majesties gracious disposition towards them, and of the Strength and opulence of the British Nation and the Benefit they will enjoy in a Commerce with them.”70 Once in London, these travellers were a sensation. They drew crowds and wore Inuit-style clothing that Caubvick and Ickonogogue assembled from cloth instead of sealskin. The voyage started out well, but in the end four of the five travelers died of smallpox. After Tooklavina’s death widowed Caubvick, Cartwright began to include references to Caubvick when he spoke about his own family. Cartwright’s workers also formed families with Inuit women. After the mid-1770s, Inuit women began to have children with English and Irish men who worked for Cartwright. In 1775 Tweegock gave birth to a girl named Phillis whom John Ryan fathered. In 1776 Nooquashock gave birth to twins whom David Scully fathered. In 1778 Tweegock gave birth to another girl, fathered by James Gready.71 None of these children survived to adulthood until an Inuk named Sarah gave birth to William Phippard, Jr., fathered by William Phippard.72 In 1786, the final year of Cartwright’s Labrador residence, he attempted to marry an Inuit partner by proposing to a young Inuit woman who was a wife of Eketcheak. She rebuffed him.73 Cartwright’s workers may have had understood Inuit families better than he did.

34 The Nain mission reduced but did not stop Inuit travel in their southern territories. After the Nain mission opened, the volume of Cartwright’s Inuit trade decreased. He attributed this to the Moravians having “engrossed” Inuit trade. This trend continued until Cartwright’s Inuit trade all but stopped in 1773. 74 Also in 1773, an epidemic of smallpox killed many of Labrador’s Inuit inhabitants. In 1772, rival merchants Noble and Pinson had dispossessed Cartwright of his best salmon posts at Cape Charles. Cartwright decamped to Sandwich Bay, three hundred kilometers to the north but still south of both Hamilton Inlet and the future Moravian mission of Hoffenthal (Hopedale) at Arvertok – the usual wintering home of Attuiock’s family. Cartwright largely stopped noting Inuit trade in his journal, and he began buying peltry from Innu traders instead. Yet some Inuit traders continued to make voyages to the south.75 During the 1780s, the merchant house of John Slade and Company expanded their Newfoundland operations from Fogo Island to Battle Harbour, close to Cartwright’s former Cape Charles post. Starting in 1796, Inuit traders began to appear in the partnership’s Battle Harbour account ledgers and, in 1798, at least 12 Inuit traders exchanged seal oil, sealskins, and other pelts for firearms, munitions, and textiles.76 Inuit people had not ceased to travel to their traditional southern territories.

35 Inuit women continued to have children with English and Irish men after Cartwright departed Labrador in 1786.77 The partnership of Hunt and Henley operated the Sandwich Bay post after Cartwright, and Hunt and Henley eventually sold the post to the HBC in 1873. The HBC had begun to establish locations in Labrador in 1836 at the pre-existing merchant posts of Rigolet and Northwest River. The company intended to draw trade away from the St. Lawrence and other, smaller Labrador traders.78 These HBC posts employed women on contracts to do work such as cooking and sewing clothing. Company men at these posts had children with local women, causing Labrador’s resident population to grow. These Labrador Métis families became a majority of the population in southern Labrador during the 19th century, and were a pool of male and female workers for the HBC. In these families, Inuit women passed on Inuit culture to new generations.79 In these respects Labrador resembled Western North America, where women were both workers in the fur trade and creators of kinship networks.80 Writing during the early years of this history, Cartwright only hinted at this work and even derided it.81 It was more important than he or other merchants likely realized.

36 Ann Carlos and Frank Lewis summarize the relations of Indigenous traders with the Hudson’s Bay Company by writing that these “had elements that were social, cultural, and religious, but theirs was primarily a commercial relationship.”82 This simplification is useful, yet it does not do justice to the British-Inuit friendships and families that existed in Labrador 50 years before the Hudson’s Bay Company began to trade there. During the early years of transculturation, British and Inuit traders influenced what their trading partnerships meant to each other. British merchants who worked in Labrador were at the edges of British authority and needed to learn from the Inuit inhabitants, who were more than just consumers of trade goods or producers of commodities. So Cartwright and other traders adapted themselves to Inuit methods of forming friendships and households, even if they misunderstood why these friendships and households were significant. And one reason why this was significant is because the English and Irish men who partnered with Inuit women in Labrador had children together who became Labrador Métis or Southern Inuit. Cartwright documented this but did not, of course, cause this. His writings show the increased significance of both Inuit households to English trade and Inuit workers in English households during a pivotal moment in Labrador’s distinct pattern of gendered work. There was ambiguity in Cartwright’s words and behaviours. We might expect nothing else. He had once attempted yet failed to describe his ties to Inuit people as being primarily commercial, when these were modelled on the complexities of Inuit and British friendships and households.