Research Notes

Greater New England as Cultural Borderland:

A Critical Appraisal

1 THE IDEA OF BORDERLAND IS MOST OFTEN ASSOCIATED with the argument that land on either side of a border exists in a liminal condition – i.e., it has many of the traits of both regions and yet is different because of the hybridization resulting from the merging of the two regions within a particular space. Michael Dear identifies borderlands as alternative or third nations, spaces inhabited by people who identify with each other on a number of levels based on a shared history and geography and blurred cultures.1 Through exchange, it is argued, transnational cultures are created that are characterized by liminality and hybridity. While much of the debate around the existence of a “Greater New England” has centered on historical cross-border flows of goods, people, and capital,2 it is culture, I believe, that is most important in the creation of the idea or ideal of an Atlantic borderland.3 Did cultural exchange in the Atlantic borderland produce a common culture and therefore a cultural region that is unique to this part of North America? This research note offers some reflection on this question, with a specific focus on settler societies.

Culture and borderlands

2 Before addressing such a question, it is necessary to establish a working definition of border culture and to consider the importance of this complex concept in the study of borders and borderlands. One of the more thoughtful discussions on this subject is that offered by Victor Konrad and Heather Nicol, who see border culture “as the way we live in, write about, talk about and construct policies about the border, and the way in which we have constructed landscapes of binational regulation and exchange.” This is a rich and innovative synthesis of a broad range of theoretical and historical perspectives on the Canadian-American borderlands that uses culture as the lens to understand “re-bordering” in North America. In particular, Konrad and Nicol emphasize the importance of understanding socially constructed cultural identities within local borderland cultures. Their perspective rests upon a view of culture “as a social framework for enabling and limiting thought and action, and then considering it as an effect or expression of political and economic processes that pattern meaning, social relations, and ways of life, as suggested by Michel Foucault and Don Mitchell.”4

3 All borderlands, including those shared between Canada and the United States, are defined by the flows and fusions of cultures facilitated by the transboundary movement of peoples, technologies, symbols, texts, ideas, etc. Together, these flows and networks of material and non-material culture establish reciprocal relations and transactions between individuals, communities, and regions separated by a political boundary. Theorists have identified a number of outcomes of this cultural diffusion, including assimilation, pluralism, and hybridization – the latter often favoured by borderland specialists who focus on syncretist cultural practices that accompany cross-border movements.5 “All such movements,” Jennifer McGarrigle maintains, “help establish patterns of common cultural beliefs across borders and reciprocal transactions between separate places, whereby cultural ideas found in one influence those in another.”6 In the context of post-colonial border theory that emerged in the 1980s and 1990s,7 Homi Bhabha’s discourse of hybridity8 and Victor Turner’s concept of liminality,9 this syncretism, it is argued, is essential in the formation of borderland cultures, borderland cultural landscapes, and associated borderland identities.

4 While attractive, this view of borderland cultures leaves a number of questions that are not easily answered. Does such a cultural diffusion necessarily produce a common culture and similar values? And, in the case of Canada and the United States, does the asymmetry that characterizes this particular relationship produce a borderland culture that is dominated primarily by the latter, with Quebec being the only notable exception? Or is this particular borderland zone imbued with hybrid cultures, landscapes, and identities that reflect elements of both countries and their respective borderland regions or even specific borderland communities? More generally, does a borderland culture reflect a combination of local and regional identities and national allegiances with traits and traditions that transcend the border?

5 Borders rarely separate cultures completely, and so the possibility of a borderland culture and cultural landscape arising from the cross-border movements of peoples, goods, and ideas makes sense. The essentialist view that presumes fixed boundaries for a culture should be questioned, as the parameters of culture extend beyond geographically contained territorial units. Culture moves across local, regional, national, and transnational networks. Yet the idea that such mixing can produce a distinct hybrid culture that is different from those cultures associated with the respective nation-states is an idea that is much more difficult with which to come to terms. Culture is a spatiotemporal matrix of possibilities, limitations, and choices and operates as a fundamental base upon which the idea of a borderland rests. Yet cultures are dynamic and subject to change, either from within or from without and most often from a combination of the two. While cultural hybridity as a concept recognizes the existence of multiple layers of identity, it also is subject to the criticisms of essentialism and oversimplification. It is much too facile to reduce the borderlander to an “essential” idea(l) of what it means to be Canadian/American, or, in this particular case, a “greater New Englander.” Like all other concepts, it requires definition and placement within specific historical and geographical contexts. As Konrad and Nicol state, the Canada-US border culture “is continually forming, apparently always in transition, and inevitably altered through transaction. This culture is dynamic, and constantly evolving, nurtured by successful exchange, and honed by the barrage of challenges that it encounters.”10

6 These reflections underlie the following discussion, which is intended to encourage scholars to think about another direction for the topic of cross-border affinities between New England and the Maritime region – one that emphasizes cultural comparison, at least in a non-Indigenous context, as opposed to the economic and political considerations that tend to dominate historical scholarship. It is tendered in the hopes of stimulating new discussion and encouraging others to take some of my suggestions and subject them to detailed critical analysis. Before tackling the question of culture, however, it is important to offer a brief reconnaissance on the considerable body of historical scholarship that has addressed the origins and development of what has been termed a “Greater New England” or the “Northeastern Borderlands.” The debate over the borderland of the earlier era remains significant to any discussion of the borderland that evolved over the course of the late 19th and 20th centuries. However, as Phillip Buckner comments, the borderland after Confederation was very different than that which existed earlier. Indeed, Buckner asserts, while the borderlands concept is “useful and valuable when dealing with the early period of settlement when the border was nebulous, . . . [it] becomes increasingly difficult to apply in the nineteenth century, particularly after the creation of the Canadian nation.”11

The historical debate

7 John Bartlet Brebner, George Rawlyk, and Graeme Wynn have described a pre-revolutionary Nova Scotia and Acadia as part of a wider economic and cultural unit whose constituent parts were linked by ties of trade and kinship.12 Before their expulsion, Acadians traded their agricultural surplus with New England and so New Englanders were familiar with the Bay of Fundy region. After the expulsion, farmers, then called “Planters” – primarily from eastern Connecticut and to a lesser extent from Massachusetts and Rhode Island – took up former Acadian lands in the Annapolis Valley, around the head of the Bay of Fundy, and along the St. John River. The Planters, with their particular English dialects, village greens, Cape Cod cottages, and Congregational and Baptist churches, introduced New England influences to the Maritimes’ cultural landscape.13 The end result, scholars have argued, was a northern extension of New England into the former Acadia. However, while the influx of Planters almost doubled the population of Nova Scotia, many subsequently returned home or left for the Ohio country despite the Royal Proclamation edict banning settlement west of the Appalachians.14

8 Even though the Planters for the most part chose not to participate in the American Revolution, they still remained, in Graeme Wynn’s opinion, “New Englanders at heart.”15 They brought with them a culture firmly rooted in New England traditions and continued to travel to New England states and maintain kith and kin connections. But they did not have too much success in transplanting institutions in their new homes. For example, as Elizabeth Mancke has demonstrated, the Planters were prevented from replicating the townships of New England in several crucial ways that tended to increase their reliance on Halifax.16 In fact, as Daniel Conlin documents, a considerable number of Planters from Liverpool, Nova Scotia, operated as privateers targeting American vessels after the end of the war.17 And perhaps most importantly, as John G. Reid points out, the Planters “crossed into a different sphere from that which had spawned the rebellion. It was one in which loyalism was a possible and relevant choice because of the crucial significance here [i.e., Nova Scotia] of the imperial state as well as the more pragmatic influence of the economic and military power of Halifax, but where the revolutionary crisis further south could reasonably be seen as a local difficulty that impinged but little on the wider world of which Planter Nova Scotia formed a part.”18 In this respect Reid echoes the argument made by Viola Barnes, who presents a case that the governor of the colony, Francis Legge, and the powerful Halifax merchants, saw an opportunity for Nova Scotia to expand its position in the North Atlantic triangle trade when New England competition would be reduced with the coming of the revolution.19

9 Largely missing from this earlier literature is the central role that Aboriginal nations played in both the Maritimes and New England before the Revolutionary War. After the coming of the Europeans, Native peoples quickly became engaged in the fur trade – at first dealing with Europeans on their ships moored in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and then later on land. At this point Native peoples held a position of power in this particular “middle ground,” but soon found themselves mired in the conflict between the British and French over control of the region. In the Maritimes, and in northern Maine as well, Native peoples allied themselves with the French, whom they believed were more interested in the fur trade than in taking their lands. By 1720 nearly all of North America east of the Appalachians was in English hands; Acadia had been lost to the British in 1713, but the French still hung on to Île Royale (Cape Breton Island). The British, however, were still wary of Native peoples’ alliances with the French and so negotiated a series of treaties with the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet peoples between 1725 and 1779.20 There were no land cessions whatsoever in the agreements, but the arrival of the Planters after the Acadian expulsion of 1755 and the Loyalists in the 1780s increased pressure on the Aboriginal land and resource base. While the treaties of 1760-61 conducted between the British and Native peoples following the defeat of France were once viewed in the context of British hegemony and Indigenous subjugation, more recent scholarship asserts that the Planter era was a period in which Aboriginal groups remained more powerful than is commonly believed.21 This position of relative power diminished with the flood of Loyalists into the region and the subsequent marginalization of Native peoples.

10 While the Planters had considerable impact on the immediate period preceding the Revolution, it was the 35,000 Loyalists arriving during and shortly after the war who had the greatest impact on the future direction of the Maritimes. Donald Meinig, Graeme Wynn, and J.M. Bumsted maintain that the Planters and the Loyalists introduced some key American political cultural values, including representative government, and as a consequence were key players in the development of a Maritimes-New England borderland.22 There is no doubt that these two groups played a significant role in cultural transfer. However, the diffusion that did take place did not produce a mirror landscape image of New England. Peter Ennals and Deryck Holdsworth maintain that even though New England architectural styles made an impact on the Maritime landscape, “Maritime Canada did not become an extension of the New England cultural region, parroting every stylistic change as it came along. While the Cape Cod house was transferred to Nova Scotia, the Connecticut salt box house was not.”23 Mancke warns, in a similar vein, that while the cultural landscape of Nova Scotia reveals evidence of New England origins, by the end of the 18th century Nova Scotian society had already been shaped in accordance with the institutions and values of the British Empire.24 Most notably, the Loyalist presence, although still dominant in certain regions of the Maritimes, was overwhelmed but not eliminated within a relatively short period of time by immigrants from Great Britain; this was particularly true of the Scottish migrants displaced by the Highland clearances and the Irish potato famine migrants.25

11 Although cross-border connections weakened somewhat after the American Revolution, the Maritimes colonies continued to trade timber and fish products with the “Boston states” in what Wynn calls “Greater New England.” He adopts the core-periphery model developed by Donald Meinig and divides the international region into a core (Massachusetts), a domain (southern Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, Maine, and Connecticut), and a distant sphere (Prince Edward Island, Cape Breton, and northern New Brunswick and the rest of Nova Scotia). Boston served as the metropolis of this transborder region, and what Wynn calls the 18th century “Boston-Bay of Fundy axis” continued to function into the 19th century, in his opinion, as “a critical determinant of interaction.” Wynn chooses to leave Newfoundland out of the loop, which suggests that he considers it to be either too distant or too closely connected to Britain and thus too far removed from the United States to be considered part of a “Greater New England.”26 This omission is entirely understandable given the fact that Newfoundland’s relationship with New England, while important, was in many ways different than the relationship that developed between the Maritimes and New England. As a consequence, I will deal mostly with the latter and only consider the “place” of Newfoundland within the wider Atlantic borderland when it is appropriate to do so.

12 Using this framework, Wynn identifies several “Greater New Englands.” The first he designates a “greater New England of experience” produced by seasonal and permanent movement of people from both sides back and forth across the border carrying goods and ideas that served to integrate the region and produce a common outlook. Over time, this movement became increasingly one-way but managed to maintain its directional focus in spite of the western fever gripping North America. Wynn also identifies a “greater New England of the primitive and the romantic.” Although much more pronounced later, the image of the Maritimes as a pristine wilderness was beginning to take shape at mid-19th century and created a vacation hinterland for the more urban and densely populated New England core. Borrowing from the frontierists, Wynn argues as well that a ready availability of land, isolation, and pioneer conditions combined with proximity to the United States to create a “greater New England of attitudes and artefacts” that resulted in a relative decrease of British manners and customs. While he does recognize that over time the Maritimes developed regional, national, and even imperial sentiments that found expression in the region’s culture, Wynn also notes that a common experience, interconnected economy, shared attitudes, and a similar material culture ensured the continuation of a “Greater New England.”27

13 Others have challenged Wynn’s thesis, instead focusing on internal developments, growing links with central Canada, and continuing connections with Britain that individually and collectively tempered New England’s influence on the Maritimes despite increasing economic integration. Mancke maintains that Nova Scotia and Massachusetts developed differently because of different cultures of localism and governance.28 The British, she argues, governed Nova Scotia more directly than New England. Different cultures of localism and institutional practices of land grants and town incorporations facilitated an ideological spirit of independence among New England’s settlers and adherence to authority among Nova Scotians, despite the fact that many of the latter were recent immigrants. In particular, she argues that the Nova Scotian townships were politically impotent and isolated from each other because imperial authorities curbed efforts to reproduce New England-style local autonomy.

14 In another piece, Mancke applies her concept of intersecting and competing “spaces of power” by which she means “systems of social power, whether economic, political, cultural, or military, that we can describe functionally and spatially” to challenge the conventional use of the core-periphery colonial model to explain early modern empires in the northeastern part of North America. Such empires, she contends, had more to do with multiple claimants to different spaces, activities, and resources than with a metropolitan-controlled settlement as such. Early on, political boundaries in the region, she maintains, “became defined by the functional specificity of commercial and cultural relations between Europeans and Natives rather than being taken from the abstract and mathematically defined boundaries articulated in royal charters. Those political boundaries, in turn, encompassed strikingly different configurations of power than those of colonies whose boundaries more closely conformed to the spaces of power defined in charter grants.” Mancke also argues that during the 18th century Nova Scotia was in no position to be self-financing, unlike the other older colonies to the south, and as such continued to be more dependent on imperial connections with a European core (Britain) than on links with a transnational region core (New England).29 Julian Gwyn insists that the evidence shows that Nova Scotia, and by implication the rest of the Maritimes, was never too dependent on New England even after economic ties strengthened. In spite of increasing trade over time, Nova Scotia was not the product of New England imperialism but rather of British imperialism in which New England played a significant role both before and after the American Revolution.30

15 While there is little doubt that the Atlantic region continued to move within the orbit of both “Old” and “New” England and that increasing trade and migration, particularly the former, ensured a greater degree of integration between the Maritimes and the “Boston states,” the question remains as to whether or not economic links, historical connections, and geographical propinquity ensured cultural integration during the period. Certainly the pre-revolutionary Planters and later the Loyalists left their imprint on the colonies in terms of material culture and social and political institutions; but they were a divided group and, as such, carried with them a mixed bag of values and commitments to imperial, Loyalist, and republican ideals. American values, opinions, and ideals, as well as material goods, were indeed carried to the Maritimes by trade, migration, and various forms of communication (e.g., newspapers). “But,” as William Godfrey asserts, “the reality was that the American loyalist presence was being rapidly absorbed in Nova Scotia and would soon swamped in New Brunswick by immigrants from Great Britain.”31

16 This position is defended most vigorously by Phillip Buckner, who has never strayed from his long-held belief that the British Empire shaped Canadian identity. Regarding the relative impact of Loyalist versus later British immigrants, he states: “The British immigrants had succeeded where the Loyalist elite had failed in establishing metropolitan culture as the norm throughout the region . . . [and] the transformation of the Maritimes from a ‘borderland’ region of the United States into a region increasingly aware of and committed to its British identity owed infinitely more to the flow of emigrants from the Britain after 1800 than it did to the influence of the Loyalists and their descendants.”32 Whereas ethnic diversity, fragmented religions, and geographical isolation combined to create what Wynn terms “a patchwork quilt of different ‘allegiances’ – Acadian, Loyalist, pre-Loyalist, Palatinate, Yankee, Scots, Irish, English”33 – earlier in the century, such a description, according to Buckner, “is totally misleading” for the Maritimes of 1860. In his view, the Maritimes of this period, and here he makes no mention of Newfoundland, was characterized by a population, at least an Anglophone population, who increasingly identified with their particular colony rather than with the wider region, British North America, Britain, or the United States. As population density increased and geographical isolation was eroded, a process of ethnic fusion took place within the colonies that created a distinctive local culture that was an amalgam of British, American, and uniquely regional influences.34 Perhaps most importantly, he argues in another piece that “the existence of a border leads naturally to the evolution of different institutions and values.”35

17 Considerable economic integration primarily through trade and secondarily through migration and investment took place between New England and the Maritimes after Confederation; but attachment to Britain, a slowly evolving but challenging association with Canada, and a developing regional consciousness counteracted further incorporation into the US orbit. Few advocated joining the US, but much debate occurred over the direction to be taken even before the end of the Civil War and the abrogation of the Reciprocity Treaty. Support for some form of British-American union was more widespread in the Maritimes during the late 1850s and early 1860s than is commonly believed.36 Maritimers were well aware that Canada needed winter ports on the Atlantic seaboard and recognized the potential that the colonies to the west presented in terms of a hinterland for Maritimes products. And while Maritimers welcomed American trade and investment, they were still wary of the threat of annexation.

18 A strong association between the Maritimes and New England, along with a growing relationship between Newfoundland and New England, continued after Confederation, but the composition of this connection changed. Cross-border migration became even more significant but then declined in importance. Cross-border transportation by boat improved, but land-based transportation, while improving significantly with the advent of the automobile, continued to be problematic. Cross-border investment increased, but remained relatively minor compared to that taking place in other borderland regions. Cross-border communication expanded, but was tempered by the development of technologies that extended the information field well beyond the borders of the transnational region. Cross-border trade continued, but declined in relative importance in light of increasing connections taking place within both Canada and the United States. Cross-border governance became more important towards the end of the 20th century, but faced obstacles that impaired its effectiveness. Integration continued, but it was moderated by nationalist forces – economic, political, social, and cultural.

The “place” of culture in the Atlantic borderland

19 The question of culture as it pertains to borderlands, it seems to me, revolves around the degree to which cultural hybridization takes place as a result of historical processes of cross-border exchanges. Pronounced regional cultures on both sides of the border certainly developed over time. Despite some differences, though, the Maritime Provinces shared much in common, including historical and cultural heritage and a traditional orientation towards the ocean. Newfoundland developed a number of ties with the Maritimes, but remained significantly different because of its unique history, culture, landscape, and arts. One feature that all provinces in Atlantic Canada, including Newfoundland, had, and still have, in common is their peripheral place within Confederation, a position that has generated a shared set of values and outlooks towards the rest of the country.37 Despite the perception held by many Canadians that the region is inherently conservative by nature and, as such, has often voted for the party in power, there is ample evidence, James Kenny suggests, to support the argument that progressive and radical values have also shaped the history of Atlantic Canada.38 From such a political culture, there developed a concern in the late 20th century over the demise of Keynesian economic philosophy in the face of neo-liberalism and the beginning of a dismantling of the welfare state that had propped up a struggling economy for such a long time.39

20 New England, on the other hand, has long been viewed as having a liberal political culture, a perception that dates back to the early 19th century when Federalists from the region united in opposition to Jeffersonian Republicanism and vociferously opposed the decision of the James Madison administration to engage in war against Britain. James Curry suggests that this cohesion on policy lay behind the decision made by the six states in the mid-20th century to develop the New England Regional Commission (NERC) to deal with shared problems, including a struggling economy, a need for improved social welfare, and environmental concerns. History demonstrates, Curry maintains, that “throughout the last 200 plus years, the New England states and its leaders have been recurrently, if not continually, united by policy and politics.”40 He goes on to argue that the collapse of the textile industry and the resultant economic decline earlier in the 20th century have served as a unifying force in the region, much like, I would suggest, economic stagnation has created regional coherence within Atlantic Canada.

21 However, Curry’s argument fails to acknowledge the diversity of ideology and political opinion that exists in New England. Daniel Elazar argues that there are three political culture types among Americans: a moral political culture, an individual political culture, and a traditional political culture.41 The moral political culture, he suggests, is one that sees government as a positive force and operates from the belief that society is held to be more important than the individual. The individual political culture, on the other hand, advocates limiting community and government intervention into private activities and works from the principle that private concerns are more important than public concerns. The traditional political culture, Elazar claims, views government as playing a positive but limited role in securing the maintenance of the existing social order and reflects an attitude that embraces a hierarchical society as part of the natural order of things. With these criteria in mind, Elazar assigns US states to different political cultures and in doing so, divides New England in two, with “Upper New England” (Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont) classified as a moral political culture and “Lower New England” (Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut) categorized as an individual political culture. This political culture division correlates with the urban and economic division that also separates northern and southern New England.

22 Yet Elazar’s political regions may be challenged on the basis of the significant difference in political ideology that has existed for quite some time between New Hampshire and Vermont. Elazar’s definition of “moral political culture” does not apply very well to New Hampshire, which has a long history of libertarian politics as opposed to Vermont’s history of moderate communitarianism. The two states, so similar in geography and yet so different in social, cultural, political, and economic structures, diverge considerably in their support of taxes and government spending and in their attitudes towards environmental protection. A study conducted by two Harvard researchers in 2007 suggest that during the latter half of the 20th century Vermont underwent a specific kind of inter-state migration composed of upscale, left-leaning people supporting a kind of progressive counter-culture that tended to be more left-leaning in its political ideology and more concerned about preserving a cleaner and more rural environment. They also point to the fact that starting in 1927 after massive flooding, Vermont began to accept federal money and this set in place a history of support of the principle of government intervention. New Hampshire, on the other hand, traveled a different path and created a political culture more supportive of industry and urbanization, thus making the state attractive for more conservative blue-collar workers. This was particularly true for the southern part of the state.42 That New Hampshire chose this path is understandable when one considers the fact that the state engaged fully in canal and railway building during the 19th century in order to attract capital for industrialization. Vermont, on the other hand, was more isolated and less blessed with industrial raw materials and, as a result, was largely bypassed by the development taking place elsewhere in New England. And while the decline of the mill industry hurt New Hampshire significantly, the southern part of the state would eventually benefit from the post-industrial hi-tech development spreading outwards from Boston.

23 The differences between the north and south and the very significant distinctions among states, particularly between Vermont and New Hampshire, lead me to conclude that it is too facile and misleading to speak of a unified New England political culture. In the same vein, it is also misleading to put too much emphasis on the idea of a cohesive Atlantic Canada. For most of its history, Newfoundland operated in a very different context and, as a result, developed a culture, economy, and society unlike that of the Maritimes.43 As well, the Maritimes is also more culturally complex than outsiders might believe. In two different studies, Ian Stewart and David McGrane and Loleen Berdahl convincingly show that towards the end of the 20th century the value sets of Maritimers were changing and that a regional political culture transcending provincial boundaries did not exist in the Maritimes.44 Thus, I believe that it is too problematic to compare and contrast an Atlantic Canadian political culture with a New England political culture for the simple reason that no monolithic or monoculture exists either north or south of the border.

24 The same reasoning applies to a discussion of literature. While the sea in general, and human interactions with the ocean in particular, are common frames of reference for both New England and the Maritimes, the literature of both regions differs in some fundamental ways. The shared position of marginality within Canada and the larger globalizing world is reflected in the literature of the Maritimes. Challenging Northrop Frye’s garrison mentality thesis that views Atlantic Canada as a region of isolated individuals at the mercy of an unforgiving nature, Gwendolyn Davies instead sees this part of Canada (including Newfoundland) as a cohesive community unified by a literature that is on the periphery – just like the region itself. Such a literature, she argues, has “mimetically explored the region’s sense of identity by exposing the social, political, and economic forces attempting to erode it.”45 In a similar vein, Janice Kulyk Keefer suggests that Maritime writing is a unique body of literature produced from a distinct society whose primary features are a strong sense of community and an open attitude to nature.46 Community as a source of identity is juxtaposed against the modern forces associated with central Canada.47

25 The literature of Atlantic Canada has for some time now imagined the region in relation to a more powerful centre, whether it be central Canada or New England, and more often the former than the latter.

26 This depiction of a region unified by a communal folk culture that stands against the forces of modernism coming from the outside has great appeal, particularly for the tourism industry, even though most Atlantic Canadians have for some time now lived in modern urban centres.48 Such a narrative flies in the face of those who argue that it is time to re-imagine the region beyond its hinterland relationship to a more powerful core. The philosopher Warwick Mules, for example, believes that “the advent of globalisation favouring local/global interconnections has the potential to disrupt and redefine the relation between the centre and its regions, where local sites previously subordinated to the power of the metro-centres can now find empowerment in their global interconnections.”49 Yet while modern technologies have expanded the spatial reach of many Atlantic Canadian communities and individuals beyond the region, “the quest of the folk” still remains strong and the attachment to place continues to play a significant role in the culture of the region.

27 According to the influential critic of American literature, Randall Stewart, New England literature at the time of the revolution was characterized by the Puritan tradition of order and restraint and a pervading religious tone.50 Puritanism, while certainly making its presence felt, was soon challenged by writers (e.g., Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau) fully committed to transcendentalism, which emphasized spiritual understanding, the power of nature, and the common man. During the late 18th and 19th centuries, New England was viewed by its writers as the cultural hub of the nation and in no way inferior to or dependent on any outside metropolitan centre. Yet it is too simplistic to think of New England as a unified region, in this case a cultural region as defined by literature. Literature produced by New England-based writers covers a complex array of themes and so, as Kent Ryden states, “as a physical presence, to be sure, New England has an independent presence; as a cultural region, however, New England is an emphatically human invention.”51 As already noted, the most obvious distinction is between the more industrial and urban south and the more rural and peripheral north; but even within these regional subdivisions there are a variety of smaller-scale cultures and distinct local economies.

28 As Ryden points out, there was a tendency among regional writers earlier in the 20th century to portray New England as a pre-modern rural refuge from the ravages of history such as the Great Depression and the social challenges presented by a modernizing, urbanizing, and industrializing world; later in the century, writers criticized the idea of New England as a coherent cultural region instead focusing more attention on those groups who had been excluded or marginalized from the popularly recognized regional identity.52 In another article, he cites the argument made by Joseph Conforti that critical regionalist authors, including Ernest Herbert, Carolyn Chute, and Richard Russo, have shifted the conceptual heart of the traditional New England northward, into Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont.53

29 And yet, Ryden argues, these writers portray this part of New England in a manner very different than that which dominated before:

By fusing the local with the global through situating current issues in a particular place, suggests Marleen Schulte, these authors have developed a new form of regionalist writing.55 It is in this part of New England, they infer, that this kind of dynamic reflection can best take place, suggesting that southern New England has already been lost to the modern globalized world. Literature has provided the medium for New England writers to debate identity, which suggests that there is no unified regional identity upon which they can agree.

30 A folk culture strongly rooted in the past and framed by the region’s hinterland status within Canada continues to carry weight in the interpretation and articulation of a Maritimes regional identity, at least among certain filmmakers and tourism promoters. Their position is analogous to that expressed by earlier novelists, including Thomas Raddall and Ernest Buckler, who remained committed to a pre-modern past where community served as a bulwark against the configuration of Confederation that placed the region into a peripheral position vis-á-vis the central Canadian core. The more recent representation of the Maritimes, however, focuses less on the region’s folk culture and more on the articulation of the region’s cultures (e.g., Herménégilde Chiasson and Anne Compton), themes of cultural inclusiveness (e.g., George Elliott Clarke), and the region’s history of underdevelopment and recent attempts to deal with neo-liberalism and globalization (e.g., David Adams Richards and Lynn Coady).56 Similarly, New England narratives of the past and the present have also centered on themes of anti-metropolitanism, economic decline, outmigration, and placelessness. In particular, much of the recent New England literature focuses less on the region’s peripheral relationship vis-á-vis a southern New England, or any other American, core and more on the negotiations made by places in response to overwhelming forces of modernization and globalization. As stated, increasingly this literature has been set primarily, although not exclusively, in northern New England. While the Maritime’s and New England’s (particularly northern New England’s) literatures share similar themes and tropes, it is important to note that while border crossings do occur from time to time there exists no significant body of literature that articulates hybrid, fluid, and liminal identities and cultures in the Atlantic Canada-New England borderland.

31 While New England and Atlantic Canada differ considerably in political culture and do not fully emulate each other in terms of regional literature, the movement of people, ideas, and goods across the border ensured that culture was transmitted and shared over time. This diffusion of culture took many forms, including that of sport. Colin Howell shows that during the period between the world wars “Maritimers and New Englanders developed a sense of shared sporting culture through connections on sporting diamonds, in hunting grounds, on the ocean, and along long-distance race courses.”57 Howell also suggests “What made borderlands sporting interaction particularly important to Maritimers during the interwar period was the region’s deep-seated sense of alienation and isolation from the rest of Canada.” He asserts, however, that after the Second World War the imagining of the northeast as a coherent transnational sporting region gave way to other constructions, most notably a pan-Canadian sporting connection that served as a countervailing force to a borderland sporting culture.58

32 New England and the Maritimes also differ somewhat in their visual arts traditions. Realism, which attempts to represent subject matter truthfully and without the framing of “ideal” conventions and mythological elements, distinguished the arts of the Maritimes for much of the 20th century. Maritimes realism grew out of rural roots and was most prominent in New Brunswick, where artists such as Alex Colville, Christopher Pratt, and Mary Pratt painted in a realist style. Colville, who taught at Mount Allison University in Sackville, had several gifted students, including Mary Pratt and Tom Forrestall, who helped spread the realist tradition throughout the region.59 While Colville and others were influenced by the American Realist movement, which also began as a reaction to and a rejection of Romanticism, the direction taken south of the border differed considerably from that in the Maritimes. While some realist artists (e.g., Andrew Wyeth and Norman Rockwell) sought to interpret rural and small town imagery, American realism was generally more urban in focus than its Canadian counterpart. In particular, the Ashcan School of New York City, which included artists such as George Bellows and Robert Henri, portrayed the social existence of lower class immigrants residing in cities. The urban focus of American artists did have an impact on some Maritime realists, including Miller Brittain and Jack Humphrey, both of whom studied in New York and, in the case of Humphrey, also in New England. But the work of these Saint John-based artists stands out as an exception to the general inclination towards rural themes in Atlantic realism.

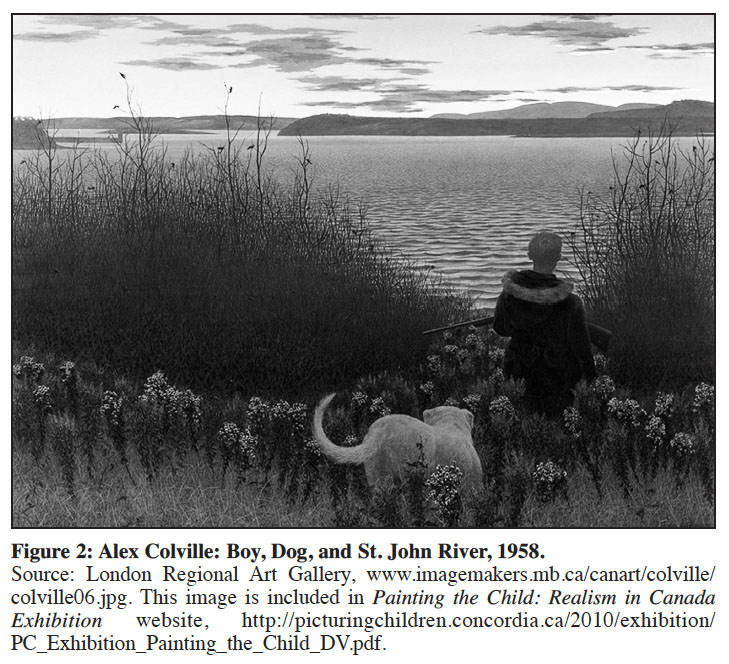

33 While American realism was expressed by artists and writers all across the country, it was most pronounced in New York City. The visual arts tradition in New England, on the other hand, was different. Like their Maritime counterparts, New England artists reacted against modernism but did so by embracing a romanticism influenced by the colonial revival movement. The colonial revival was a loosely defined cultural movement inspired by a romantic connection with the past fostered by the alienation and angst associated with an urbanizing and industrializing present. Writers such as Harriet Beecher Stowe set stories in puritan New England while impressionist artists such as Childe Hassam and Adelaide Derning painted bucolic New England landscape scenes and pre-urban folkways (Figure 1). The subtle modulations of colour and the impressionist techniques of such painting stand in stark contrast to the detail, colours, shapes, and styles used by the realist artists of Atlantic Canada (Figure 2).60

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 234 There are many different levels and scales of cross-border culture. This discussion, so far, has emphasized that while people, primarily from the Maritimes, brought elements of their culture with them across the border and that cultural messages and meanings, primarily from New England, accompanied the flows of communication and capital crossing that same border, there developed no significant hybrid Atlantic or northeastern culture, at least at the meso- or regional scale. While human relationships with the sea produced similar iconographic landscapes on both sides of the border (e.g., lighthouses and quaint fishing villages), they were more the result of analogous historical and geographical conditions than cultural hybridization.

35 Over time, it appears the traditional flows and networks that linked Atlantic Canada and New England changed and, to some extent, weakened. Communications and transportation technologies (e.g., television and air travel) facilitated cross-border flows but did not necessarily produce greater cultural integration. And the economic and, to a considerable extent, cultural ties between the Maritimes and the rest of Canada, particularly the centre, increased over time. Certainly, economic dependency between this periphery and the central core strengthened. It was within Canada that the Maritimers, and Newfoundlanders after 1949, chose to delineate their cultural identities. The United States in general, and New England in particular, continued to play a role in this project, but it was Atlantic Canada’s relationship with Canada that served as the dominant frame of reference.

36 Identity, affinity, and imagination are important ingredients in the development of a border culture. These elements are difficult enough to discern in the present, let alone the past. Nevertheless, there is evidence, I believe, that shows that it was at the local scale and between proximate communities that cultural interaction and mixing was most intense. It was in these places that two peoples, separated by a border, had the greatest opportunities to work and play together and communicate ideas and values. Border culture, in this sense, is most pronounced and manifest at the local scale; in the case of the Atlantic borderland, the space in which this took place was, and to a considerable extent still is, circumscribed by distance. While the majority of Maritimers who migrated to Boston and surrounding industrial cities in certain contexts had some opportunity to interact with each other at a social, workplace, and/or family level, they had no place from which they could assert a place-bound identity that would support either processes of cultural differentiation or cultural hybridization. There is little evidence of a trans-local fusion of a Maritime or Newfoundland culture with a New England culture taking place either in Boston or most New England communities where Americanization, however defined, proved to be victorious. Nor did a similar process take place in Atlantic Canada, where the number of American-born was so insignificant as to be inconsequential. However, a meeting of Atlantic Canadian, or at least Maritime, and New England cultures did take place along the New Brunswick-Maine border. It was in these much smaller and more proximate border communities that processes of differentiation and interconnection were contextually bound, culturally specific, and, as a result, most intense.

37 This line of reasoning parallels that of Emmanuel Brunet-Jailly, who identifies the specific culture of borderland communities as one of four analytical lenses from which to view borderland regions.61 Victor Konrad and Heather Nicol extend this argument even further, asserting that within the Canada-United States borderlands culture needs to be “re-imagined as a heterogeneous rather than a homogeneous concept” incorporating diverse perspectives.62 In this context, place and its related features play a major role in determining how culture influences people. A borderland “place” is a location defined by the intersection occurring between the global and the local as well as the social relations resulting from the interaction of people from both sides of a border. Such interaction happens within specific contexts, and in the case of the Atlantic borderlands was, and is, most pronounced along the New Brunswick-Maine border.

38 It is in this zone that people and communities interact most directly on a daily basis and share an array of interrelated activities and cultural expressions. It is the area where, theoretically, the greatest potential exists for cultural overlap, if not cultural hybridization. Frequent contact generates trans-cultural processes that transcend or mediate cultural differences. Also important is the fact that people on both sides of the border also face the same environmental conditions that result in shared cultural adaptations and, consequently, similar cultural behaviour.

39 This is the premise behind the work of Edward (“Sandy”) Ives, who made a career out of studying the cultural connections that developed between Maine and the Maritimes. In particular, he shows how the lumber woods of New Brunswick and Maine fostered a vibrant folksong tradition during the 19th and early 20th centuries. With the migration of Maine lumbermen to the northern woods of the Midwest in the late 19th century, scores of men from the Maritimes and Quebec, but primarily from New Brunswick, came to Maine to work in the camps and in doing so brought their cultural baggage, including their music, with them. Ives demonstrates how many of these songs reflected the integration of work in the woods and social activity in the camps. The music centered on shared themes and referred to specific places and people on both sides of the border. He also points to an asymmetry present in the Maine-New Brunswick folksong culture: “In my fieldwork over the past forty years, I have found ten good singers from the Maritimes to every one from Maine, and even those who were from Maine were often second-generation Maritimers or had strong Maritime connections. Taking that one step further, most of these thousands of province men who came to work in the Maine woods had two things in common: they were from poor rural areas and they were of heavily Irish or sometimes Scottish ancestry.”63 Eventually, Ives began to document via oral histories the details of lumbering and the lives of the workers employed in that industry. Regardless of which side of the border they were employed, the lumbermen of the St. John River Valley faced similar conditions and shared common lifestyles. Victor Konrad suggests that Ives and others (e.g., Richard Judd and W.E. Greening) identified a cross-border migration of loggers, techniques, machines, capital, and traditions that produced a temperate woods tradition that extended from New England and the Maritimes in the east to British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon in the west, and even north to Alaska and the Yukon.64

40 In a similar vein, Greg Marquis argues that early in the 20th century “New Brunswick’s old-time musicians, although rooted in local communities . . . shared a borderlands musical culture with New England and beyond.” Among other places, it was in the lumber camps, the lumber drives, and in the mills that fiddle music was shared among workers from Maine, the Maritimes, and Quebec, thus promoting a trans-border popular culture that originated in a common Celtic background that transcended regions throughout the eastern part of North America. The advent of radio followed by television further strengthened this musical bridge as people on both sides of the border, but primarily on the Canadian side, could listen to and see musicians from across the line perform tunes that appealed to their shared nostalgia for the “old country.” Over time, regional variations developed as the southern style of fiddling and country music out of Nashville more and more dominated old-time and folk music south of the border while the “down-east” style, popularized by groups such as Don Messer and the Islanders, came to take over the Maritimes scene. Thrown into the mix was the Acadian style of folk music that resonated in certain regions such as Madawaska.65 Eventually, traditional Maritime folk and old-time music diminished somewhat in the face of musical styles coming from outside the region; there is evidence, though, that towards the end of the 20th century there was a significant revival of long-established influences in both the folk and the folk-rock scenes.

41 In contrast, traditional Newfoundland music, with its pronounced Celtic and other European roots, continued to flourish. American troops stationed in military bases in Newfoundland and Labrador during the Second World War brought country and western and swing music with them. In particular, the American radio station VOUS (Voice of the United States), broadcast out of St. John’s, brought American popular culture to Newfoundlanders.66 Over time, other kinds of music from the United States and elsewhere were introduced to the province by radio and then other media. Nevertheless, Newfoundlanders continued to celebrate and maintain their unique musical heritage even as some of them moved away from traditional folk music. Towards the end of the 20th century, many bands actively combined original and traditional material in their repertoire. However, the musical connection that joined the Maritimes and northern New England did not exist to the same extent for Newfoundland. The province’s distance from New England meant that its music remained relatively isolated from that market even though over time the national media of Canada, in particular the CBC, ensured that the folk music culture of Newfoundland expanded beyond its borders to the rest of the country and even further.

42 Cultural diffusion in the context of borderlands implies transnational flows of people, symbols, practices, texts, ideas, etc., that together create a dynamic process of interchange that is reciprocal in nature. The outcomes of such diffusion are varied; they can include assimilation, pluralism, hybridization, or a combination of one or more of these processes. Scholars of the Atlantic borderland generally point to the Madawaska region of the upper St. John River as the place where cross-border culture is most pronounced. By the middle of the 19th century Madawaska had developed as a unique district in the northeast, a place where Acadians, Québecois, Anglo-Maritimers (primarily from New Brunswick), and Anglo-Americans (primarily from Maine) came together to form a cultural fusion that was clearly different and more distinctive from any other borderland place within the wider region. Arguably, it was the French “fact” that distinguished this particular borderland place; the dominance of the French language, architectural styles, customs, and Catholic religion enabled Acadians, Québecois, and Brayons, despite their internal differences, to control space and create a place that would offer protection from an overwhelming Anglo-American and Anglo-Canadian cultural presence.67 As Victor Konrad argues, it was a combination of a cross-border culture, market forces and trade flows, cross-border political influences, and the policy activities of multiple levels of government that produced a functional borderland place unmatched elsewhere, either in the northeast or, arguably, any other part of the Canada-United States borderland zone.68 On the other hand, Béatrice Craig, the leading Canadian scholar on the history of Madawaska, asserts that “there is no evidence that in the nineteenth century the permanent residents of the St. John Valley thought of themselves as ‘transnationals’ or of their region as a ‘borderland’.”69 Yet while they might not have thought in such terms, Madawaskans on both sides of the river belonged to an international borderland community that functioned on the basis of shared culture, intermarriage, and social and economic intercourse. Madawaska serves as the best example of what McKinsey and Konrad identify as a “divided cultural enclave,” a culturally homogeneous region split in two.70

43 However, over time, the French “fact” played less of a role in joining the New Brunswick and Maine sides. While the French language has survived in New Brunswick, the result of language legislation, cultural institutions, and constitutionally guaranteed French-language school systems, it has declined dramatically in Maine – particularly among the young. Familial and economic connections fostered by proximity still operate within the region, but an increasing language division has, arguably, eroded cross-border culture. The decline of French on the American side dates back to the early 20th century, when the language was forbidden in the classrooms of Maine except as a foreign language. In fact, until 1960, state law required that English be the only language used for teaching in the public schools of the state.71 More recently, there has taken place an expanded effort to preserve French language and culture in Madawaska, which is generally regarded as the hearth of Acadian culture in Maine. Acadian heritage is still celebrated on the Maine side in the form of festivals and music events, but any association with this particular legacy has been weakened through the loss of language.

44 Strong cross-border connections also developed during the 19th century between St. Stephen and Calais. Such linkages also continued throughout the 20th century, further reinforcing the idea that together these two communities represent one of the most integrated borderland places within the greater northeastern region. Brandon Dimmel shows how residents of these two small lumbering towns crossed the St. Croix River to work, visit, shop, and participate in sporting events, festivals, and national holidays. Dimmel suggests that the relationship between the two communities at the turn of the 20th century represents the borderland model that McKinsey and Konrad identify as “balanced cultural interaction,” occurring “between comparable centers, especially urban centers with equivalent levels of development.”72 He refers to the celebration of Victoria Day by residents of Calais and commemoration of the 4th of July by citizens of St. Stephen as well as co-participation in a combined Calais-St. Stephen baseball club that played against clubs from other New Brunswick and Maine towns as examples of cross-border interaction that resulted in the development of a cross-border identity. The economic integration resulting from the movement of cross-border labour and capital “translated,” Dimmel argues, “into deep social and cultural connections between St. Stephen, Calais, and the Milltowns on both sides of the border. Local men joined fraternal organizations that not only welcomed members regardless of their citizenship but attempted to maintain good relations between residents of St. Stephen and Calais.” Strong connections between the two communities were also forged by cross-border marriages. “Calais marriage records,” Dimmel states, “show that nearly one in ten marriages in the 1890s involved a resident of Calais marrying a person from St. Stephen or Milltown, New Brunswick. During the decade encompassing the First World War (1910-1919), approximately 17 per cent of all marriages recorded in Calais were of the transnational variety.”73

45 However, the cohesive fabric of this transnational community, Dimmel shows, was weakened to some extent with the onset of the First World War. At first, St. Stephen residents demonstrated modest support for the Canadian war effort, a reaction Dimmel suggests that may

This would change, he maintains, with Canada’s participation in the Battle of Second Ypres in April of 1915, which resulted in the first casualties of St. Stephen and area soldiers. From that point until the U.S. entered the war, St. Stephen residents supported the war effort and were critical of American neutrality and any negative opinions towards the war expressed in the very conservative Calais newspaper. The war also brought out attachments to the British Empire and fostered greater national pride. However, Dimmel argues, support for the Canadian war effort in Calais increased over time, particularly as residents of the Maine community recognized the price their northern neighbours were paying on the battlefields of Europe. And with the American entry into the war in April of 1917, the bond between the two borderland towns increased even more. This connection continued over time, even as St. Stephen and Calais faced increasing economic uncertainty. Notably, Dimmel posits that the relative isolation of both communities from larger provincial and state neighbours encouraged strong local and, by extension, transnational identities.74

46 Although Madawaska and Calais differed in some significant respects, both places throughout the 19th and 20th centuries shared a peripheral position within New England and were isolated from the political, economic and cultural center of the region located to the south. A geographical position characterized by peripherality within and isolation from New England quite possibly made these two communities and other Maine towns along the international border more susceptible to influences from Canada in general and from New Brunswick and eastern Quebec in particular. People in Madawaska, Calais, Fort Kent, Edmundston, St. Stephen, and other communities on both sides of the border developed an association with each other and the location they shared, and in this sense they developed over time an attachment to and an identity based on their specific borderland place. Borderland identity and culture is context-dependent. The isolation facing these communities produced some degree of place dependency as well as sense of place and place attachment. In Madawaska, traditions from different cultures blended together in the same place to create something that did not previously exist. But such mixing was not nearly as evident in Calais-St. Stephen or any other communities within the New Brunswick-Maine borderland zone during the 19th and early 20th centuries. If anything, the landscapes of late capitalism characterized by chain stores and malls and having very little to do with the unique cultural landscapes of the past in either the Maritimes or New England came to dominate.

Conclusion

47 Did cultural exchange among settler societies in the Atlantic borderland produce a common culture that is unique to this part of North America? My answer is a qualified “no.” While proximity and a shared environment ensured the development of many economic interdependencies and cultural similarities, there is little evidence, outside of the Madawaska area, of the emergence of a Maritime or Atlantic or “Greater New England” cultural hybrid – i.e., a third space where cultural antecedents were altered by the process of mixing. My case is not made as an indictment against those who have emphasized cross-border affinities within the northeastern borderland. Indeed, many of these scholars have acknowledged the particularities and distinctiveness of the Maritime provinces and northern New England as well. Instead I am arguing for an approach that emphasizes and addresses the complexities of cross-border interaction, one that recognizes the significant changes that took place over time and is sensitive to considerations of scale and context.

48 Outside of Madawaska, I see little evidence of hybrid landscapes or identities that reflect either elements of both the Atlantic region and New England or their respective borderlands. Cultural similarities do exist; for example, New England Loyalists and Planters introduced architectural and urban designs to the Maritimes. But this was cultural transfer, not cultural hybridization. Strong historical and geographical similarities, including a shared Anglo-Celtic settlement, a pronounced French presence, and a marked orientation towards the sea also ensured other connections. Over time, American culture in the form of media (e.g., cable television) and consumerism, more often conveying messages and values from outside than from within New England, made increasing inroads into the Maritimes. But these influences were more than counteracted by the interweaving of a developing national culture and a strongly entrenched regional culture. It is much too simplistic to reduce the northeastern borderlander to an archetype based on the cultural anomaly of Madawaska. In my opinion, the study of borders and borderlands must be grounded in their specific contexts so as to avoid the temptation to overgeneralize based on one case.

49 RANDY WIDDIS