Articles

Trans-Atlantic Sheep, Regional Development, and the Cape Breton Development Corporation, 1972-1982

Cape Breton Development Corporation (DEVCO) – a federal Crown corporation created in 1967 – was charged with stimulating employment to compensate for the decline of island coal mining. Following the failure of industrial promotion, DEVCO adopted a participatory regional development practice between 1972 and 1982. With specific reference to sheep producers, this article argues that DEVCO focused on imparting entrepreneurship, boosting production, and selling a particular kind of Cape Breton. However, DEVCO objectives were undermined by the very capitalist processes they sought to amend. The Cape Breton sheep story provides a way into the broader history of regional development in these years.

La Société de développement du Cap-Breton (SDCB), une société d’État fédérale créée en 1967, était chargée de stimuler l’emploi afin de compenser le déclin de l’exploitation du charbon dans l’île. Après l’échec des efforts de promotion industrielle, la SDCB a adopté une approche participative du développement régional entre 1972 et 1982. En ce qui concerne particulièrement les producteurs ovins, cet article fait valoir que la SDCB s’est employée à transmettre l’esprit d’entreprise, à accroître la production et à vendre une conception particulière du Cap-Breton. Les procédés capitalistes mêmes qu’ils cherchaient à modifier ont cependant compromis les objectifs de la SDCB. L’histoire de l’industrie ovine au Cap-Breton permet d’aborder l’histoire plus générale du développement régional au cours de ces années.

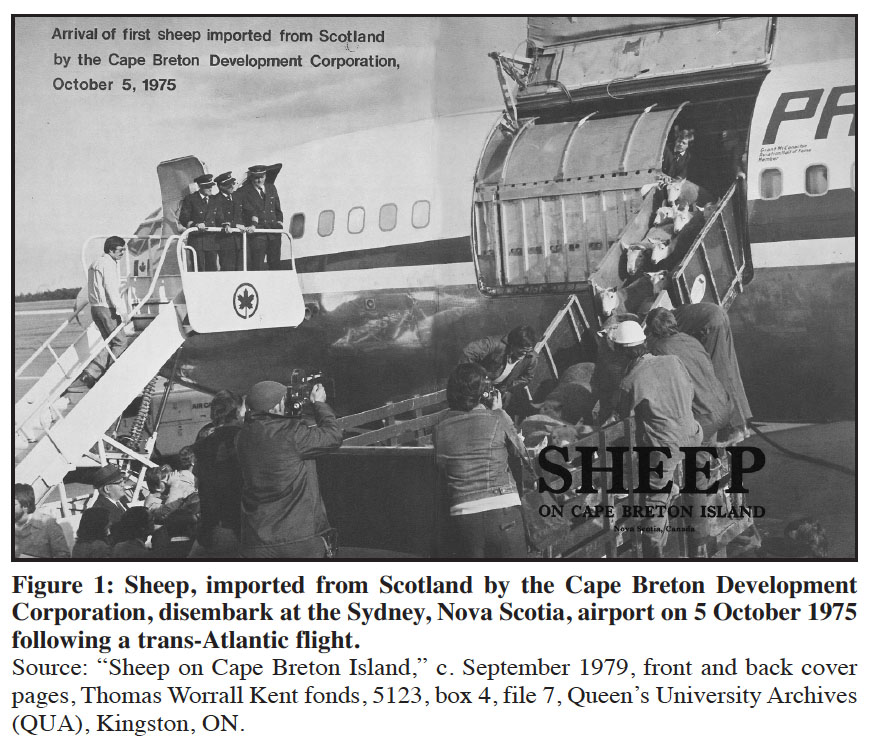

1 ON 5 OCTOBER 1975, A DOUBLE-DECKED BOEING 707 carrying about 500 sheep from Scotland landed at the Sydney Airport in Cape Breton. The sheep were received on the tarmac by “the sound of pipes and applause.” Cape Breton Development Corporation (DEVCO) officials, who had arranged the transport, believed that the trans-Atlantic livestock would contribute to the development of Cape Breton.1 Using sheep – and the curious airport scene – as an entry-point, this article examines DEVCO’s approach to regional development during the 1970s.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 12 Regional development mattered in both a global and a Canadian context. From the late 1950s, decolonization and the Cold War focused particular attention on global inequality. Development was an idea rooted in a broadly shared conviction in the necessity of alleviating poverty. To develop was to intervene in the processes shaping existing social relations and to seek to amend them. Such an aim enabled a range of actors to re-think colonial relationships. The proponents of modernization theory were particularly influential in re-imagining the world as a binary place comprised of developed and underdeveloped nations. To “catch up” with developed counterparts, it was largely agreed that underdeveloped societies required restructuring to facilitate the pursuit of material prosperity and economic progress.2 Increasingly, the same binary logic contributed to new ways of thinking about inequality and economic processes within countries. No longer were countries unitary economic spaces. Governments in North America, Europe, and the Third World all sought to address geographical concentrations of poverty and uneven development in the interest of preserving political unity and economic legitimacy.3 Indeed, economists and policymakers in Canada identified significant inequalities among regions and sought to do something about them.Policymakers, like later scholars drawing on dependency theory, focused their attention especially on the Atlantic Provinces — where lower average incomes were not only a statistical fact but also an established source of political tension within Canadian federalism.4

3 The liberal case for regional development in the 1960s and 1970s was that Canadians “should have good opportunities to earn their living at roughly comparable standards wherever they live from sea to sea.” In that respect, regional development was a call for spatial justice and for a measure of socio-economic democracy. A newly interventionist state might alter the processes of capital accumulation to make them more equitable and evenly distributed. The goal of regional development, as a memorandum to federal Cabinet went on to explain, was “that economic growth should be dispersed widely enough across Canada to bring employment and earning opportunities in the hitherto slow-growth regions as close to those in the rest of the country as proves to be possible without an unacceptable reduction in the rate of national growth.”5 The federal government developed new programs focused on these areas.

4 The economics and social science scholarship on regional development initiatives in Canada is ample. Often with reference to interwar precursors, it parses the wide array of regional development policies. Some of these – including the Agricultural and Rehabilitation Development Act (1960) and the Fund for Economic Development (1966) – focused particularly on rural reconstruction. But others – the Atlantic Development Board (1962), the Area Development Agency (1963), the renamed Agriculture and Rural Development Act (1966), and the Department of Regional Economic Expansion (1969) – sought to foster urban-centric development in slow-growth regions by investing in infrastructure and attracting industry with capital incentives.6 However, historians have scarcely begun to consider such programs.7 Like regional development more broadly, DEVCO has hitherto been examined by social scientists. In addition to Allan Tupper’s article-length account of DEVCO’s creation, a number of theses and papers examine – in varying depth – the corporation’s stated development policy.8 Two past DEVCO officials have added their own analyses.9 Departing from earlier scholarship, this essay is concerned less with public policy-making itself and far more with how regional development worked in practice within one historical context.

5 Studying DEVCO provides a compelling way into the history of regional development in Canada. Unlike other regional initiatives pursued through federal-provincial planning and cooperation, DEVCO was unique: a Crown corporation with significant autonomy and a mandate covering Cape Breton Island. It was created in 1967 as part of the federal government’s decision – prompted by a crisis of corporate profitability, the prospect of community collapse, and public demand – to nationalize Cape Breton’s coal mines. On the one hand, DEVCO’s Coal Division was tasked with reducing the mine labour force and winding down longstanding coal mining operations. On the other hand, its Industrial Development Division (IDD) was responsible for stimulating alternative industry and employment.10 Therefore, DEVCO’s overall task – in line with similar government responses to declining coal industries in Britain, Belgium, and France – was to restructure the economy in a coal mining area.11 The practice was contradictory because the state sought to generate a revived liberal democratic capitalist order in which state intervention would become marginal. Not only did policymakers fail to identify capitalism as the cause of regional economic differences, they sought to achieve greater equality by using use public funds to induce capitalist development in a circumscribed economically depressed region.

6 Historians interested in DEVCO must contend with a paucity of surviving records. DEVCO was not covered by federal government archives legislation. In 1987, IDD was dissolved and regional development responsibilities passed to Enterprise Cape Breton Corporation, which reported to the Atlantic Canada Opportunity Agency.12 At some point, as far as I can ascertain from my enquiries, IDD’s records were destroyed – by DEVCO or by one of its succeeding agencies. Therefore, a note on available sources is in order. The best material on DEVCO’s development activities in the late 1960s, including Board of Directors’ meeting minutes, can be found in the Senator Alasdair B. Graham fonds at Library and Archives Canada. Testimony before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Regional Development is also relevant. A Cape Breton Development Corporation fonds at the same archives is less useful, as it relates mostly to coal mining and often pre-DEVCO years. For detailed documents on DEVCO development policy between late 1971 and 1977, the Thomas Worrall Kent fonds at Queen’s University Archives are essential. Equally, the collections of the Beaton Institute are indispensable. Highlights include a complete set of DEVCO annual reports; numerous DEVCO press releases contained in the Rev. Andrew Hogan, MP fonds; and a Cape Breton Development Corporation fonds proper – though its bulk comprises coal mining engineering materials. Both the Cape Breton Post and Cape Breton Highlander newspapers are valuable sources. The Beaton Institute has an index for each, covering up until 1972 and 1976 respectively. A number of reports commissioned by DEVCO are held as part of Cape Breton University Library’s Bras d’Or Collection, now digitized at http://openmine.ca. Finally, I conducted a number of interviews with past participants.

7 The following narrative and analysis examines DEVCO’s regional development program in Cape Breton during the 1970s, with specific reference to sheep. A first section sets out necessary political, economic, and intellectual context. A second details DEVCO’s intervention in sheep-related activities. Breaking with 1960s industrial promotion strategies, DEVCO responded to changing conditions with a new form of development. I argue that DEVCO’s re-worked regional development practice turned on imparting entrepreneurship, boosting production, and selling a particular kind of Cape Breton. DEVCO sought regional redress by intensifying the interactions of select Cape Bretoners with the market. Between 1972 and 1982, sheep producers were drawn into a participatory kind of regional development. However, as the sheep story illustrates, DEVCO did not meet its economic objectives and the capitalist processes it sought to amend undermined its regional development efforts.

A special place

8 Trans-Atlantic sheep were imported to Cape Breton in 1975. However, that event followed a mid-1960s political crisis, DEVCO’s creation, and the corporation’s initial failure to re-industrialize the island’s economy. A resulting re-imagination of regional development practice in the early 1970s prompted attention to sheep farming and related industries.

9 Corporate-controlled coal and steel industries, operated with a minimum of investment and labour cost, were the focus of the economy in industrial Cape Breton from the start of the 20th century.13 But profits declined and coal markets eroded following the Second World War. Moreover, royal commissions in 1946 and 1960 highlighted growing federal government concern over the soaring cost of coal subsidies first introduced during the Great Depression.14

10 The continued operation of the Cape Breton coal and steel industries was the predominant local political question, and popular mobilization shaped government’s eventual response. Maritimes elites, farmers, workers, and fishermen expressed discontent over the regional inequalities within Confederation from the 1920s.15

11 During the 1950s, political and business elites responded anew to outmigration and the decline of primary industries. Wanting to better participate in rising postwar standards of living, they insisted on the need for “a vigorous capitalist economy, an interventionist democratic state, and mass consumption.”16 Atlantic Canada-minded federal regional development policies, focused increasingly on urban industry rather than rural reconstruction, were introduced in response to the pressure. In Cape Breton, the prospect of de-industrialization heightened widespread concern. And Cape Bretoners, prompted by a series of layoffs and mine closures in the 1950s and early 1960s, intensely lobbied the federal and provincial governments for coal industry-specific corrective action.17

12 In reply, a 1966 federal study was launched and it laid the groundwork for the formation of DEVCO. The Donald Report argued that the dependence of the Cape Breton economy on a single industry – a federal government-sustained one, at that – was no longer viable. The report insisted that the state should buy the mines and, over a period of 15 years, wind down coal mining operations. Moreover, with the savings accrued from an end to subventions, government could stimulate a diversified economic base that would provide workers with alternative employment.18 Here was a basic program for how the liberal state should respond to the crisis of profitability of a monopolistic corporation, to the prospect of community collapse, and to the vocal pressure of workers dependent on the coal industry.

13 That the federal government endorsed such an initiative only reinforced how much the issue mattered to regional electoral politics. According to two insider accounts, Inverness-Richmond MP and Liberal cabinet minister Allan J. MacEachen provided the direct impetus to form DEVCO in summer 1967.19 Still, the federal Liberals demurred on additional nationalization of island industry. When 35,000 Cape Bretoners responded to the announced closure of the Sydney steel mill by marching in the Parade of Concern in mid-October 1967, the provincial government stepped in with its own Crown corporation, Sydney Steel Corporation (SYSCO), to operate the mill.20 Despite state ownership, uncertainty remained about a timeline on the continued existence of the coal and steel industries.

14 DEVCO, a federal Crown corporation overseen by a board of directors, assumed control of Cape Breton’s coal mines in October 1967. Its Coal Division was directed to reduce the workforce, cut costs, and slowly end mining. Between 1968 and 1977, DEVCO received about $400 million from the federal government – $230 million to cover coal mining operating losses, $120 million for mining capital expenditure, $50 million for development.21 DEVCO was, to a significant extent, a coal company.

15 The development prerogative, though, justified the corporation’s existence. To compensate for the elimination of mining jobs, an Industrial Development Division was empowered “to promote and assist the financing and development of industry on the Island to provide employment outside the coal producing area” and to broaden “the base of the Island’s economy.”22 At its outset, IDD borrowed principles – including modernization theory, growth poles, and the use of capital incentives – from other contemporary federal and provincial regional development efforts.23 Indeed, one direct DEVCO antecedent was Industrial Estates Limited (IEL), a Nova Scotia agency created in 1958 within a consensus that economically marginal areas should seek to attract industry from elsewhere. After 1964, IEL sought to diversify the provincial economy, and to create jobs, by providing companies with equity, grants, and financing.24 DEVCO adopted an equivalent goal as well as the same means of attaining it.

16 Early DEVCO officials envisioned a growth-oriented, technologically adaptable industrial economy. Their answer to gradual de-industrialization in coal (and potentially steel) was to promote re-industrialization for an emergent continental consumer economy. Cape Breton was to become a site of assembly. The corporation, in a contradictory affinity for state-aided “free enterprise,” largely sought to foster new secondary manufacturing industries. Newly established plants would create jobs, prompt further private investment, and eventually lead to self-sustaining economic growth and prosperity. DEVCO assumed that it was fixed capital costs that prevented firms from locating in Cape Breton. Therefore, it used capital incentives and infrastructure investment to attract new industry to two informal growth poles at either end of the island. But a strong majority of the firms DEVCO helped finance in 1968 and 1969 went bankrupt in swift succession in 1970 and 1971 as the North American economy slowed. Having spent its initial allocation of development funds, it was unclear whether DEVCO would go on to pursue its mandate. However, DEVCO did chart a new program for regional development.

17 High unemployment, a low labour participation rate, outmigration, and plant closures marked Cape Breton as the island experienced acute effects of the deepening North American recession. Continental postwar growth was the product of an expansionary capitalism driven by Cold War rearmament, trade liberalization, and consumer spending. A crisis of accumulation, however, took shape from the late 1960s, right at the moment of DEVCO’s failed attempt to stimulate secondary manufacturing. By the mid-1970s, unemployment, inflation, and a relative decline in industrial employment across North America brought “embedded liberalism” into question and emboldened advocates of neoliberal restructuring.25

18 Defensive activism in Cape Breton remained. In 1976 significant joblessness provoked several community responses, including a crisis town hall meeting sponsored by a rising local NDP as well as the creation of employment committees, job centres, and unemployed workers’ unions.26 By one calculation in 1977, unemployment and non-employment meant that Cape Breton had four jobs when it should have five, or a 53,000 labour force with ten per cent unemployment when full employment would see 60,000 jobs.27 This was the economic context for continued efforts to boost the island’s economy during the 1970s.

19 Tom Kent, DEVCO’s president between late 1971 and January 1977, was the key figure in remaking regional development in Cape Breton. An advocate of a more proactive liberalism, Kent, a journalist-turned-bureaucrat, was central to federal government social and economic reforms from 1963. Although critical of the Trudeau government economic policies, he decided to take the DEVCO position.28

20 Kent dispensed with two key aspects of DEVCO’s past policy. First, he reversed plans to end coal mining. The Coal Division’s attrition policy had reduced productivity and employment in the mines, but IDD had not succeeded in building an alternative industrial base. Therefore Kent did not envision a viable regional economy without active coal and steel industries, and DEVCO backed the rationalization and modernization of each.29 The sharp rise in global oil prices in 1973 and 1979 did allow DEVCO to boost coal production and consider new investment. But when the price of oil collapsed in the early 1980s, hopes for renewed economic development via coal did as well. Moreover, by 1978, global recession and overproduction scuttled a plan to build a massive new steel complex in Cape Breton.30

21 Second, when it came to economic diversification, Kent rejected using capital incentives to entice underfunded “foot-loose” industries to locate in Cape Breton. He argued that the industries DEVCO had previously assisted would not have succeeded anywhere, but especially not off the “beaten path” where labour, transportation, and production costs were high.31 An alternative was required.

22 Kent’s vision of regional development framed DEVCO’s subsequent sheep-related intervention. In his view, DEVCO was a business operation with unusual motives – one that might offer a viable alternative to outmigration or economic decline. Development, he suggested, was about boosting future earnings and creating the income that people wanted. Therefore, DEVCO needed to confront both unemployment and underemployment. In addition, it should build from local people and local resources. Kent argued: “Development is for people. The basic idea of development is concerned with the quality of life. It is improvement in the way that people, as individuals, are able to live.”32

23 In practice, what did people-centered development require? Kent argued that entrepreneurship – understood as “seeking and taking economic opportunities” – was “the essential ingredient” in preventing the attrition of Cape Breton society.33 The absence of that quality had to do as much with psychology as it did economics. Kent felt that, in the past, Cape Bretoners had been “losers,” exploited by foreign capital, looked down on by other Nova Scotians, constricted by failing industries, and dispirited as young people departed.34 As a result, he decided that DEVCO needed “to supply the initial entrepreneurship that is the pre-condition of the normal economic mechanisms beginning to function more satisfactorily.”35 It was not that DEVCO should substitute for the private sector, but it needed to kick-start “more vigorous local enterprise” that might spur economic growth and also attract outside capital.36 By correcting what was abnormal about Cape Breton, Kent believed that the region’s economy could pick up as normal. Therefore, Kent contended that DEVCO would both work to identify “real opportunities” and to convince Cape Bretoners that those opportunities could be developed. He hoped not just to build up businesses, but build “momentum.” To do so meant that DEVCO would have to be more than a “developer” and itself become an entrepreneur. DEVCO would take risks in support of various ventures, and even be prepared to go into business itself. In the process of whatever entrepreneurial endeavour it undertook, DEVCO would be imparting entrepreneurialism and a possessive individualism to Cape Bretoners.37

24 Kent’s views on a changing continental economy shaped the form of those activities. He questioned the association between development and large-scale modern industries. Rather, in “the so-called post-industrial society on which the developed world is now plainly entering” he argued that the “right economic future for Cape Breton lies in producing a great variety of things in enterprises that are mostly fairly small, that produce the specialities on which an increasing affluent and educated and sophisticated society will spend more of its money.”38 Future sources of income and employment would come in service industries and in specialized processing and manufacturing operations: “This is the kind of business that the people of Cape Breton, with their unique environment and distinctive history and traditions and pride, should be able to do.”39

25 Kent assumed that that Cape Breton was “a special kind of place.” In doing so, he foregrounded tourism as a way to increase earnings and popularize a “Cape Breton theme” to which local entrepreneurship would relate.40 The laundry list of products he eyed connected commodities with the presumed Cape Breton “cultural situation”: lamb, oysters, furniture, pleasure boats, woollen goods, fish, whiskey.41 Suggesting that “a slower, gentler style of life is coming back into style,” Kent believed that new economic activities could be accommodated in such a way as to allow Cape Breton to remain “almost entirely a place of nature, as it is understood by people whose cultural roots go back to Scotland and Brittany and Ireland and the north of England.” He went on to suggest that “an effective development policy,” responding to “these real opportunities,” will “be one that combines the exploitation of primary and service activities that fit the distinctive environment and style of Cape Breton.”42

26 In these terms, Kent’s vision somewhat recalled what historian Ian McKay has described as “Innocence” – a 1920 to 1950 form of liberal antimodernism that ideologically served to stabilize, at least to some degree, the existing socio-economic order amidst regional economic decline. Local elites and the provincial state imagined that Nova Scotia’s essence lay in an unchanging rural, rugged, and picturesque Scottish folk society by the sea.43 In so doing, they constructed a generic past-ness amenable to exchange. Myth-making was caught up with commodification, and it formed the basis of tourism promotion from the mid-1930s.44 Accordingly, Kent set out a DEVCO policy geared towards greater sensitivity to, and increased commodification of, rural Cape Breton. Not only did DEVCO seek to provide the material and ideological requirements of increased tourism, it looked to root regional development in an idealized understanding of natural resources, cultural tradition, and rural authenticity. In fact, within the wider frame, DEVCO’s rural turn was not unique and was in line with the changing emphasis of international development practice.45

27 Under Kent’s stewardship, IDD turned toward tourism, fishing, farming, and forestry as well as some associated secondary processing and production. Cape Bretoners were selectively involved in an entrepreneurial, quasi-participatory regional development. In practice, IDD assistance came in a few regular forms. First, IDD provided loans to private businesses. Second, it undertook a few commercial projects of its own. Third, it engaged in what is now called public-private partnership. IDD loans, capital, and ownership equity deferred economic risk with a view toward private profit and eventual full private ownership.

28 Most pertinently, DEVCO assistance to independent producers followed a fourth pattern. IDD consulted with producers’ organizations – and where one did not exist, stimulated their creation. Cape Breton sheep producer, cattle owner, oyster farmer, beekeeper, Christmas tree cutter, vegetable grower, and handicraft maker associations were mobilized. IDD then delivered loans and expertise to producers presumed to have shared problems and be in common cause. Notably, in several cases, IDD established its own commercial subsidiary in a given sector. These subsidiary companies were DEVCO-operated and almost entirely owned by DEVCO. Their creation increased the distance between those offering technical and financial assistance and those receiving it. To the extent that development remained participatory, DEVCO was in a position of acting on behalf of, rather than in conjunction with, producers. Nonetheless, DEVCO policy stressed that even if it took the “operational lead” the end goal was to have producers’ cooperatives eventually take control.

29 Such an approach was undertaken with scarce reference to Cape Breton’s history of cooperative organization.46 Still, in stimulating producers’ associations, IDD employees took a development support role akin to that of Antigonish Movement extension workers. Moreover, the accent Kent placed on participation, first, recalled earlier efforts to have primary producers collectively accommodate capitalism and, second, emphasized that DEVCO represented a temporary redistribution of government resources pending economic renewal.

Cape Breton Lamb

30 In 1972, several years before Scottish sheep were airlifted in, Tom Kent surveyed Cape Breton’s agricultural scene. To his mind, lamb stood out as “one product whose quality, for the little that is now produced, is outstanding.” He felt that it “could be a high-class food for the affluent market.”47 There were sheep on the island from the mid-17th century, but flock sizes declined beginning in the mid-19th century.48 Drawing on this longer trajectory, Kent aimed to reverse the decline and re-establish Cape Breton as a prominent place of sheep production. Such a vision played on historical continuity with the past, and Kent juxtaposed the rise and fall of coal mining with the fall and presumed rise of sheep farming. Early sheep farmers had been drawn to the mines and given up their flocks, the narrative went, but now rural renewal presented itself if DEVCO could change the attitudes of Cape Bretoners towards the possibilities of the sheep industry.49 In fact, as it would be applied to sheep producers, DEVCO regional development practice worked to build entrepreneurship, increase production, commodify a particular vision of Cape Breton, and extend interactions with capitalist markets.

31 In a sheep policy crafted in 1973, Kent argued that Cape Breton had the natural resources – grass, this case implied – to improve food production. “The problem in economic engineering,” he continued, “is whether those resources can be organized to respond to the market.” To that end, he felt that expanding sheep production was necessary, and different forms of capital assistance could have a substantial effect in that regard.50 Noting relatively high prices, Kent insisted that producing lamb was an “important opportunity.” He continued: “But for all their years of struggle and disappointment, Cape Breton farmers cannot be expected to seize the new opportunity unless they can reckon on some definite assurance that their work will not be in vain. DEVCO’s program provides that assurance.”51 DEVCO would take on “a degree of risk itself,” and provide assistance so that the economic constraints facing sheep producers would be lessened and they might better benefit from the market.52 Sheep farming, moreover, was not unrelated to tourism. Tourism might not only deliver consumers who would eat local lamb, but sheep would dot Cape Breton hills and become a part of the scenery of an economic renewal.53 Not just lamb, but lamb associated with Cape Breton, was needed for success.

32 If Kent wanted to engineer improved economic and ideological conditions, sheep farming was already shaped by shifting market relations. Maritime agriculture, marked from the 19th century by unequal distribution of land and resources deepened by market-driven stratification, underwent post-Second World War changes following interwar difficulties.54 The conclusions of scholars examining Prince Edward Island are instructive. Despite provincial government efforts to sustain agricultural trade, farm incomes and profit margins fell. People responded by abandoning farms, finding other sources of income, or investing in mechanization and additional land. Overall, there was a decided 1950-to-1980 movement from farming to part-time farming and to non-farm employment.55

33 Indeed, sheep farming alone did not sustain rural Cape Bretoners engaged in the practice. A 1952 federal Department of Agriculture study of 99 Nova Scotia sheep farms noted that the average flock size was fewer than 30 sheep. Farmers averaged 5.7 hours of labour per sheep and their return – after expenses, just under half the sale price of a ewe – worked out to $1.37 an hour.56 Not all that much had changed by 1978, when an analysis confirmed that Cape Breton farmers operated on a part-time basis. Consultants estimated that it would take a minimum of 500 sheep to make a full-time living. No Cape Breton farmer reached that threshold. Just 11 of the island’s 90 sheep producers had flocks larger than 200 animals. By contrast, 37 farmers had between 50 and 100 sheep and another 35 farmers had less than 50. Producers either practiced mixed farming or held other employment. As a result, sheep returns supplemented rural incomes derived from some constellation of farm activities, part- or full-time, non-farm work, seasonal wage labour, handicraft production, old age pensions, and unemployment insurance.57

34 Sheep-raising followed a seasonal rhythm linked to the livestock’s reproductive cycle. Each fall, farmers sold off most of the lambs born that spring to local abattoirs or at sales in Mabou and Truro. Flocks of breeding animals, reduced almost by half, were then maintained through the winter. For smaller producers, finding further buyers for wool and the hides of farm-slaughtered animals was not worth the cost or difficulty.58

35 DEVCO’s financial, technical, and commercial assistance to sheep farmers was slowly elaborated over the course of several years. After sounding out individual sheep farmers, IDD officials met in May 1972 with a small number of farmers who already had a loose organization. The officials expressed interest in aiding the lamb industry, and asked farmers to form a formal association through which DEVCO could channel its efforts. The sheep owners agreed, and the resulting Cape Breton Sheep Producers Association (CBSPA) was a voluntary organization that served to better organize and rationalize the sheep sector. It allowed DEVCO to engage sheep producers and to get them to participate in development.59

36 The members picked David Newton to serve as CBSPA president. Newton and his wife Pamela were early back-to-the-landers from New York who moved, baby and dog in tow, to a small farm at Point Edward in 1963. They stayed and raised a family of six children. Like other rural residents, they periodically re-evaluated their priorities for generating income. The family acquired a few sheep and the flock grew to about 100 animals. Initially, Newton also cut pulp and grew vegetables. Yet an illness to one of his children pushed him to get a job in town as a Cape Breton Post associate editor. Not long after assuming the CBSPA role, Newton was hired by DEVCO and made IDD’s Director of Primary Production.60

37 DEVCO’s goal was to help existing farmers raise sheep more efficiently and effectively, and to raise their economic returns. DEVCO’s initial financial aid to sheep producers consisted of a series of loans, guarantees, and market support. These measures aimed to increase the size and quality of flock sizes in Cape Breton. Only farmers with at least 25 sheep were eligible for support. An unintentional effect of DEVCO (as well as provincial government) subsidies, however, was to make sheep-raising more attractive and to draw more people into the industry, especially among the good number of back-to-the-landers who moved to Cape Breton because of its cheap land.61 DEVCO, for instance, offered low-interest loans to allow farmers to clear land and to buy breeding stock, fence wire to enclose new pastureland, and fertilizer to improve grazing; about 50 took advantage of the loans. With respect to guarantees, DEVCO agreed to buy lamb in 1974 and 1975 at 1973 prices, thereby ensuring farmers a certain profit. Prices, though, rose and rendered the guarantee moot. DEVCO, too, sought to counteract the tendency of farmers to sell off the quickest growing lambs and keep slower-growing brethren for breeding. It agreed to buy ewes at market rate and lend them back to farmers for breeding. Overall, DEVCO counted a 30 per cent increase in flock numbers in 1973 alone.62

38 DEVCO’s attempts to boost production were fit to concurrent attempts to “enable Cape Breton lamb to penetrate the larger markets of North America.” In 1973, Newton got together a truckload of sheep to send to a meat packer. With most lamb sold locally to that point, the corporation insisted that it was its experiments “in negotiating sales that will make Cape Breton lamb known in the major consuming centres as quality meat.”63 The emphasis on quality and on “Cape Breton lamb” underlined the sense that marketing had to do with more than delivering lamb to buyers at a reduced cost to farmers. Rather, ensuring high returns and increased lamb consumption was tied up with the diffuse concept of “reputation” – which to DEVCO officials connoted desire not only for tasty lamb, but also lamb associated with Cape Breton.

39 DEVCO provided technical assistance to sheep farmers as well. A demonstration farm and sheep herd in Mabou, overseen by Ann MacDonald and later Frazer Hunter, became a resource centre for sheep farmers. It offered services such as a ram rental program for breeding.64 In addition, a few sheep husbandry extension courses were put on.65

40 By 1974, Newton felt that the sheep industry was not expanding as quickly as farmers had hoped nor to the extent that DEVCO had believed was possible. DEVCO resolved to supplement breeding efforts by buying up stock from elsewhere. Newton initially travelled the eastern seaboard and bought about 500 ewes. Still, it was felt that the availability and quality of sheep restricted the further expansion of the industry in Cape Breton. Ignoring leading global lamb-producing nations Australia and New Zealand, DEVCO employees drew on a consensus among farmers and Nova Scotia agriculture officials that the sheep stock best suited to Cape Breton could only be found in Scotland. As Newton explained, white-faced North Country Cheviot sheep were “of the highest quality” and most adaptable to Cape Breton’s natural environment because they had the very wool to offer protection from driving rains and a harsh climate.66

41 Cape Breton Lamb Ltd. (CBL) was a company created by DEVCO in late 1974 to facilitate a large-scale importation of sheep from Scotland to Cape Breton. Given that imported livestock were subject to strict quarantine regulations – sheep had to be at least three-and-a-half years old and held in isolation for thirty months – the capital and logistics required were beyond the individual farmer. DEVCO reasoned “an organization distinct from present sheep enterprises” was needed. CBL was to be a facilitator of sheep industry expansion. DEVCO envisioned a significant multiplication of the imported sheep, a favourable return on its investment, and an estimated 78 full-time jobs resulting from its intervention.67

42 CBL was modelled to involve sheep farmers and become a vehicle of independent producers seeking to establish themselves on a more commercial basis. If DEVCO would provide a loan to cover operating expenses and own half the company, the other shares were made available to participating farmers. Yet only about ten producers bought shares, just enough for DEVCO to make a case that its importation scheme had actual farmer support. By 1977, DEVCO owned 96.2 per cent of the company and CBL was to a significant extent a subsidiary acting on behalf of, rather than in conjunction with, sheep farmers. Ann MacDonald was CBL’s manager, Newton its president, and Kent chairman of the board.68 This kind of top-down development made the scale of CBL’s activities possible, but not, as we will see, without generating tensions with the producers it was designed to assist. DEVCO continued to consult with experienced farmers and CBSPA, but neither the association nor CBL’s minority shareholders had a true hold over DEVCO’s undertakings. That said, DEVCO believed that CBL could be dissolved once the importation and quarantine were complete and the sheep stock sold to producers.

43 From spring 1975, DEVCO personnel made arrangements regarding transportation, quarantine, certification, and purchases. Sheep from 46 different farms in Scotland and northeastern England were bought, totalling some 1,500 head with just 58 rams among them. When all was set, DEVCO transformed the importation of the first 500 sheep into an October 1975 media event. DEVCO-commissioned filmmakers as well as the news media were on hand to capture the scene.69 The importation was replicated in fall 1976, with about 1,300 more sheep flown in.70 Following the importations, CBL’s main activity was managing quarantined flocks. Sheep were briefly held at Point Edward and then contracted to local farms for three years. Come 1978, CBL’s inventory was 3,206 sheep.71

44 DEVCO planned to unload the post-quarantine sheep to two markets. First, it would sell sheep to Cape Breton sheep farmers with the intention of building the size and quality of their flocks. Second, it would also sell a smaller number of sheep to buyers from across North America in order to build a reputation for Cape Breton as a site of excellent breeding stock.72 DEVCO, in other words, wanted farmers to engage both in the feeder and breeder (as it were) markets, possibly undercutting Cape Breton’s claim to a special, Scottish breed all of its own. Newton recalled that gaining publicity for DEVCO’s sheep was thought more important than strictly protecting Cape Breton claims to the white-faced North Country Cheviot breed.73

45 CBL’s plans to make a return on its investment via sales to other North American sheep farmers, though, hit a diplomatic hurdle. According to American regulations, British sheep could only enter the United States via Canada. But, as Kent explained in May 1978 to Canada’s federal Minister of Agriculture Eugene Whelan, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) changed its rules and refused to allow importation until the fifth year in the lives of the first-generation progeny. Moreover, the new rules required a 60- rather than 30-month quarantine. Kent deemed the change in rules “sudden and arbitrary.” Newton met with the USDA officials in Maryland, but did not made headway. Moreover, he suspected that USDA changed its guidelines under pressure from American sheep breeders aware that DEVCO’s sheep were coming to market.74 Whelan contacted his American counterpart, while Kent reached out to the US ambassador to Canada. The diplomacy did not have an effect, and USDA stood by its policy.75

46 The diplomatic exchanges occurred amidst a wider DEVCO effort to advertise “The Great Sheep Sale,” the grandly named fall 1978 auction to sell off the sheep imported three years prior. CBL’s sale brochure laid identification with the past, nature, rural charm, and inherent Scottishness on thick. Advertising the Cape Breton lamb industry blurred into overt DEVCO self-promotion and self-congratulation. In one section the brochure juxtaposed modernity and antimodernism and deployed Scottish place names in a description of the 1975 importation, itself the “pinnacle” of DEVCO’s assistance to the sheep industry. Emerging from a double-deck of a Boeing 707 were “rams with names of ancient lineage – Braeval, Champion, Brotherstone Rover, Achscrabster sailor – whose massive frames were formed by the Pentland Firth and on the sides of Lauderlake. Following them came the ewes, flatfooted and bright eyed hill stock from the shores of Lock Shin, motherly park ewes from Orkney and Balnamoon. Five hundred head in all, vanguard of another thousand to follow, centurians in a new army.”76

47 A CBL promotional brochure laid out even more extensive imagery. “Among gourmets,” it began, Cape Breton lamb “basks in a reputation of quality – it has acquired a distinction over the years which is the envy of other sheep producing areas.” Sheep, it asserted, had been in Cape Breton as long as Acadians and Scots. The Mabou highlands, the shore near Framboise, and Margaree were deployed as connotative place names to rival those of Scotland. The white-faced Cheviot sheep were “fine boned and vigorous,” and the brochure matched them to a naturalist and scenic paradise: “There is no question that the Island of Cape Breton, not only on the western side and on the high, most drenched hills, is admirably suited to sheep production. Disease, the bane of lowland areas does not thrive. And so on the hills and shores of Cape Breton, an animal has developed which is vigorous and able to withstand adversity.”77 Hold that thought for later.

48 The lamb itself was “noted for its fine texture, its lack of coarseness,” and DEVCO’s copywriter insisted that this was likely related to what could be foraged in the Cape Breton environment: “The lambs are not stuffed with grain in feed lots nor are they growing fat in lush bottom pastures. They have ample milk from the ewes and in the high hills there are plentiful fine-stemmed grasses. In the spruce and fir woods where the flocks shelter from the mid-day heat, there are berries, a bite of mushroom, an occasional browse among hardwood saplings, clear water, and always a tang of salt in the air, for the sea is never far off.” The sensory tour concluded with an uplifting sales pitch. DEVCO assistance and improving markets “add to the growing conviction that the sheep industry will play a significant part in a reviving rural economy, and a quality-conscious public will be able to ask for and be served Cape Breton lamb.” It finished: “When you eat lamb, wherever you may be, perhaps it will evoke thought of hills and shorelines, and the forests, fields, and lakes of Cape Breton Island.”78

49 CBL sold about 800 offspring to Cape Bretoners and another 350 or so to other buyers drawn from across Canada. On another day, many of the original quarantine animals were sold off. About 2,000 sheep changed hands. On a final day of the sale, CBSPA held its third annual auction. Fifty-three local producers conscripted 1,700 lambs for sale and prices exceeded those of the previous year by 15 per cent.79 Newton believed the high prices were a sign of success. That Cape Breton sheep were “commanding premium prices,” as he put it, was an indication that “sheep are damned good and that doesn’t just include the offspring of imported sheep. Local sheep got very satisfactory prices. I’m sure the farmers are happy. I know the buyers are happy.” He observed that since the prices were as much as four times what a butcher would pay, farmers would be spurred to breed their purchases or sell them as breeding stock.80 Newton voiced no downside to the high auction prices.

50 The second “Super Sheep Sale” was held in fall 1979 to sell off the second group of sheep imported in 1976. DEVCO maintained its demonstration farm and technical assistance, but CBL ceased to be a going concern after the sales, its chief function fulfilled as anticipated. Later auctions were held by CBSPA.81 Therefore, DEVCO’s sheep intervention appeared to follow its original designs: financial, technical, and commercial assistance were giving way to a self-sufficient industry marshalled by independent producers in common cause.

51 Beginning in 1973, DEVCO eyed additional ways that sheep farmers could earn income. A small tannery was run at the Mabou demonstration farm and there was some talk that CBL might become involved in slaughtering and chilling facilities, tanning, and the manufacture and sale of wool and wool products.82 DEVCO’s interest in value-added sheep products was connected to Kent’s sense that secondary manufacturing and, indeed, cottage industries, should be closely tied to Cape Breton’s resources. Dan White, then a 27-year-old high school teacher active in the community and local media, was hired in July 1974 to become IDD’s Director of Secondary Industry.83 DEVCO and White moved ahead with a nascent kind of vertical integration in sheep-related industries in 1976. Both a wool mill and a tannery were set-up in advance of the completion of the sheep quarantines. DEVCO officials bet that market conditions would be favourable and that sheep producers would indeed soon have large flocks.

52 In the first instance, IDD personnel hoped to process local sheep wool and then distribute finished yarn through Island Crafts (a DEVCO subsidiary selling handicrafts). They initially worked with independent yarn producers associated with the Cape Breton School of Crafts. But, eyeing increased mechanization of production, DEVCO bought a small craft mill in Quebec, relocated it to Cape Breton, and recruited a family to operate it on their farm at Irish Cove. Cape Breton Woollen Mills Ltd. was established in October 1976 as a public-private partnership between DEVCO and the Cash family. Though production was scheduled to commence in July 1978, the mill ran into a number of technical, mechanical, and quality issues. For instance, North County Cheviot sheep wool proved insufficiently malleable and Australian sheep wool had to be purchased so that the wools could be blended. Though never intended to be a large industry, the mill employed as many as 17 people.84

53 IDD followed up by considering a further public-private venture to produce knitted woollen garments from local yarn. An Icelandic company was invited to apply its component production model (albeit with clothing in the distinct “Cape Breton Image”). Information seminars were held, but the project was not carried forward.85 Meanwhile, for the mill, markets proved scarce, costs high, and sales fell during an early 1980s recession. In 1984, a new cost-cutting regime at DEVCO sold the full mill ownership to the Cash family. Yet the mill required more work and capital than the family were willing to invest, and they wound down operations.86

54 In a second initiative, DEVCO sought in 1976 to expand its Mabou tanning operations. DEVCO officials concluded that since the sheep hide sales were good, efforts should be made to turn out a better-finished product. Unable to locate a willing local investor, IDD bought new equipment and set up a physical plant under the auspices of a company called the Woolbur Tannery at Blue Mills.87 Carl Reichel, a Czech-born tanner having cash flow problems at his business in Newfoundland, was brought on as manager. The tannery temporarily closed in 1978 and, with difficulty obtaining sheep hides locally, had to buy various hides from elsewhere to keep production going. Pending the expansion of local flocks, then, larger-scale tanning operations were tenuous. In October 1982, the company was sold to Reichel and renamed.88

55 Cape Breton had 11,960 sheep in 1966, 6,382 in 1971, and, thanks to DEVCO’s importations, 10,123 on 64 farms in 1976. In 1981, in part because some imported sheep had been auctioned to off-island farmers, there were about 8,000 head in Cape Breton. However, the number of sheep was just 2,582 in 1991 and under 1,500 in 2009.89 What happened?

56 Most immediately, disease affected the horizons of Cape Breton’s sheep industry under DEVCO’s watch. In spring 1979, farmers and DEVCO staff at the Mabou demonstration farm spotted pulmonary adenomatosis (PA) among their sheep. PA is a lung disease spread, in close contact, through nasal and oral secretion. It causes cancer-like tumour growth on the lungs to the point where sheep die from asphyxiation.90 Government veterinarians were quickly mobilized and found no further incidences in a survey of 50 Cape Breton flocks. Three Cape Breton cases were later discovered, though PA was not identified in DEVCO sheep beyond the initial outbreak. The origin of PA may well have been with the other sheep that farmers mixed in with their newly purchased North County Cheviot sheep.91

57 A second disease was more consequential. Under quarantine, DEVCO’s imported sheep had produced fewer lambs than had been hoped. Moreover, abortions had been a common occurrence. It was not until farmers sent dead lamb to the provincial veterinary laboratory in Truro that a cause was pinpointed in April 1980: enzootic abortion (EAE). EAE, a bacterium in the chlamydia group, is a disease indigenous to North America and spread among sheep largely though the inhalation or ingestion of infected materials such as aborted fetuses, placentas, and vaginal discharges. It causes pregnant ewes to abort, typically late in the gestation period. Not all those sheep infected abort their pregnancies and immunity is generally produced after initial cases. A federal Department of Agriculture circular suggested that once a flock became infected, 25-30 per cent of pregnant ewes aborted. In subsequent years, the number might fall to about five per cent.92

58 Between ongoing sales of lamb and the arrested birth rate caused by EAE, sheep numbers in Cape Breton began to drop. By fall 1980, there had been an estimated 16 per cent flock loss. Farmers were feeling the adverse effects. Guy Sanders, a sheep and cattle farmer in Orangedale, remembered the debilitating feeling of having worked all year only to have to bag dead lambs. With profit margins already slim, a number of Cape Breton sheep farmers pressed for compensation and relief.93 In mid-September 1980, DEVCO responded with an aid program. Centrally, farmers were given access to a vaccine newly developed in Britain. After the British government refused to sell to DEVCO on account of its limited supply, David Newton travelled to Scotland to buy up a stock privately. DEVCO reimbursed farmers for the vaccine cost and imposed a one-year moratorium on interest payments on its loans to sheep producers. All the while, DEVCO’s Frazer Hunter insisted that there had been no adverse effect on sheep sales.94

59 Farmers also wanted more information. At the request of the Sheep Producers’ Association of Nova Scotia, the province launched a special task force on EAE and PA.95 Additionally, veterinarians and farmers met at an information meeting held at the Nova Scotia Agricultural College in December 1980.96

60 For angered sheep farmers, there remained the issue of culpability. Many believed that the sheep imported by DEVCO were the cause of both diseases and thought that the quarantine, overseen by the federal Department of Agriculture, was sloppy and that government had not been prompt in revealing the presence of disease once it was discovered. An internal federal Department of Agriculture investigation concluded that there had been no government wrongdoing regarding the DEVCO sheep importation and quarantine. Yet an investigation by journalist Parker Barss Donham made regulations look decidedly partial. If government officials had clearly wanted to guard against ailments not present in North America (such as scrapie and foot and mouth disease), PA appeared to fit the category. In documents Donham obtained regarding a separate 1976 importation of sheep from France, PA and EAE were cited as possible diseases to look out for. No such mention was made on DEVCO’s import permit.97

61 Farmer anger more pointedly targeted DEVCO, too. Indeed, at least three charged that DEVCO officials were aware of the diseases and had concealed them so that the imported sheep could be sold off. Jean MacLean, a former DEVCO shepherd, concurred and suggested that concerns she had voiced to superiors about abortion losses had not been taken seriously.98

62 Amidst all of this, striking was the lamentation of the lost reputation of Cape Breton lamb as much as the loss of actual sheep. But the sentiment was hardly surprising given the repeated emphasis Newton and Kent had placed on building up the Cape Breton lamb brand. Dr. Bruce Nettleton, a Truro veterinarian who had previously taught a DEVCO husbandry course, captured the theme in February 1981 when he argued that in the year since the discovery of EAE, Cape Breton had lost its reputation in the agricultural sector as a place of top quality breeding stock. Moreover, he concluded that the great enthusiasm for the industry that prompted the sheep importation was the first step in the industry’s downfall. DEVCO officials, then, were the implied culprits. He observed that breeding stock were selling at 50-67 per cent of their 1979 levels and sometimes below slaughter prices.99 For his part, Newton was defiant and argued that disease was a minor problem and that it did not obscure the success of the importation, which he labelled “a bloody triumph for this area.”100 However, the public controversy, as well as Tom Kent’s departure from DEVCO’s Board of Directors in 1982, led new DEVCO decision-makers to end the corporation’s support of the Cape Breton sheep industry.101

63 Putting pause to concerns over disease was that PA did not spread and the EAE vaccine proved immediately effective. When it came to the trajectory of the Cape Breton sheep industry, however, the prevalence of disease was not the whole story. In fact, DEVCO’s commercial activities and marketing interventions appear to have produced an economic bubble. The much-trumpeted sheep sales in 1978 and 1979 generated record sale prices because DEVCO insisted that sheep from Scotland were well adapted to Cape Breton and that they would be the basis of a desirable and profitable product, Cape Breton lamb. Newton, recall, believed that soaring prices were a fine indication of success. Most of the buyers, however, were the very Cape Breton farmers DEVCO hoped to assist in building up their flocks. In the view of longtime Margaree sheep farmer John MacKinnon, the subsequent problems the industry faced came about because too many inexperienced newcomers got involved in sheep production. If he sounded curmudgeonly, he also observed that many Cape Breton sheep farmers “paid these ridiculous prices and they found they didn’t make a go of it . . . .”102 Farmers had invested in new ewes at the height of prices sustained by DEVCO fanfare regarding its trans-Atlantic sheep, with no guarantee that inflated prices would hold and benefit producers in the future.

64 Yet not only did farmers not really benefit from the sheep-related program, DEVCO’s efforts to extoll a distinctive Cape Breton lamb – and thereby encourage consumers to pay more for it – failed to have an effect. Unable to compete with cheaper New Zealand and Australian imports in a small but integrated market for lamb, new and even established small-scale sheep farmers in Cape Breton gradually got out of sheep farming and focused on other things. Plus, coyotes migrated to Cape Breton by the mid-1980s and keeping large numbers of sheep safe increasingly required costly investment in new fencing and barns. The remaining sheep farmers mostly chose to keep smaller herds and, therefore, raised sheep only as one among several economic activities. Occupational pluralism remained a key strategy for rural household economies.103

Conclusion

65 In 1986, a DEVCO consultant report surveyed Cape Breton agriculture. It concluded that the sheep industry “appears to be in a state of decline and, almost without exception, farmers and farm leaders felt that the sheep program originally promoted by the Corporation failed to reach its objectives.”104 Such expressions contrasted with the sense of hope initially generated by regional development.

66 I have argued that DEVCO’s development assistance to sheep producers sought to boost production, impart entrepreneurship, intensify market interactions, and sell lamb linked to a specific vision of Cape Breton. DEVCO succeeded in generating short-term enthusiasm for sheep farming and in briefly boosting the island’s sheep stock, but not much beyond that in its transitory involvement with the Cape Breton sheep industry.105 Farmers spent a lot of time, effort, and money on the DEVCO promise of future increases in income and of revitalized sheep and sheep-related industries. The economic return failed to materialize. Due ultimately to market constraints, DEVCO was unable to foster a rural sheep industry on the desired commercial scale.

67 In the broader frame, DEVCO consisted of a limited and temporary redistribution of state resources in the interest of reconciling liberal democracy with the spatial and social consequences of the capitalist system. DEVCO applied regional development – an international practice with particular relevance to the unequal economic position of Atlantic Provinces within Canada – to Cape Breton. The Crown corporation, accepting a dim future for the coal mining operations it took over in 1967, attempted to diversify the island’s economy by using capital incentives to draw secondary manufacturing industry from elsewhere. When that strategy failed, new DEVCO president Tom Kent crafted what he felt was an entrepreneurial and authentic form of regional development better suited to local people and resources.

68 Beginning in 1972, the corporation sought regional economic renewal through a participatory kind of development that worked to deepen the interactions of a limited number of Cape Bretoners with the market. DEVCO attempted to alter select conditions without transcending the capitalist structures and social relations producing persistent inequalities. As DEVCO’s engagement with sheep production demonstrated, regional development in Cape Breton was dissipated by the very contradictions it sought to adjust. In the process, improvements in standard of living, as well as political alternatives, were deferred.