Research Notes / Notes de recherche

An Analysis of Jacques Cartier’s Exploration of the Gaspé Coast, 1534

1 SOME ASPECTS OF JACQUES CARTIER’S VOYAGE OF EXPLORATION along the Gaspé coast in 1534 continue to be subject to debate and discussion. This study takes account of the divergent views expressed in published works by scholars and historians relating to this voyage. Many years of navigation and research spent on the waters between Cap d’Espoir and Cap Gaspé have enabled us to also gather first-hand information concerning this part of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, visited by Cartier on his first voyage. We had the opportunity to follow Ganong’s advice, which was to follow Cartier’s course, and view the places he described in his narrative from the same positions that he did. A similar methodology was used by Lewis for the North Shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence aboard a sailboat, and by Morison on an airplane.1 We have carefully examined some facts not fully considered by previous historians, who were sometimes unfamiliar with the distinctive features of this maritime region. We reached different conclusions regarding the identification of some place names, about the possible coastal course taken by the expedition’s vessels, and also over the landing place of Cartier in Baie de Gaspé. More broadly, this research note is also intended as a contribution for those interested in the early exploration of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the history of the Gaspésie region.

2 Cartier’s voyage of 1534 was one among several attempts by the maritime powers of Europe to find a shorter sea route leading to the spices and gold of Asia. With the landing of the Genoese navigator Christopher Columbus on the shore of the New World in 1492, Spain was given access to an immense and rich continent. Vasco de Gama’s caravels had rounded southern Africa at the end of the 15th century, opening a new trade route to India for the maritime power of Portugal. Pope Alexander VI, assuming international jurisdiction, had divided the world outside Europe between Spain and Portugal in 1493. One year later, with the Treaty of Tordesillas, the two kingdoms agreed that the line of demarcation would be drawn north-south 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. Ships would soon bring back from the Americas precious metals and goods to Spain. Portugal now had access to spices and silks from India, timbers and dyes from Brazil, and gold and slaves from Africa.

3 European politics, during the early decades of the 16th century, was characterized by conflicts, rivalry, and warfare among the major kingdoms in competition for the hegemony and control of the continent. The Treaty of Tordesillas was unacceptable to the other European kingdoms; it was ignored in some cases, and eventually contested.2 English and Portuguese ventures in search of a northwestern passage, between 1497 and 1509, ended without lasting results, although they may have influenced the early expansion of the Newfoundland fishery.3 For the king of France, Francis I, it became an economic imperative to obtain direct access to the Spice Islands and the gold of the hoped-for new lands. Already controlled by the Portuguese, the long and difficult navigation around the Cape of Good Hope was not an option for France, and neither was the dangerous sea route around the South American continent identified in 1520 by the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan.

4 It was under a commission from the king of France that a Florentine, Giovanni da Verrazzano, explored the North American coast from South Carolina to New England in 1524. Verrazzano’s voyage definitively confirmed that these countries were not part of eastern Asia but a new continent, a landmass blocking the access to the eastern sea.4 It was also evident that the Americas were already occupied by millions of Natives, speaking hundreds of languages.5 The differences between the two civilizations were great. Many European rulers considered the Indigenous people as savages to be conquered and evangelized, and the lands they occupied as territories full of resources, natural and human, to be exploited. This conceit, combined with the introduction of diseases from Europe, had already had adverse effects on Indigenous cultures in some areas. Among the resources to be exploited were the cold and rich waters surrounding some of these lands. Fishermen from Portugal, England, Brittany, Normandy, and French Basque Region were already fishing for Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) in the vicinity of Newfoundland long before Cartier’s first voyage. Fishermen and whalers from the Spanish Basque Country were probably not far behind.

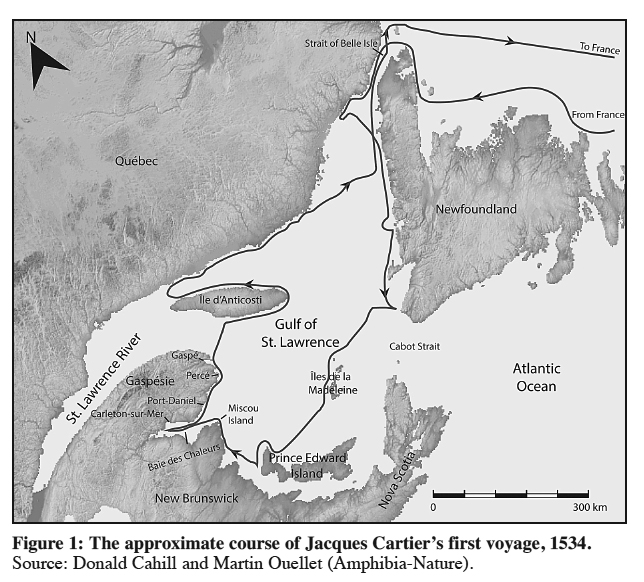

5 Rumours of the existence of a large unexplored gulf were certainly part of dockside discussions in certain fishing ports in Western Europe before 1534. It is highly probable that some ships had already ventured further inside the Gulf of St. Lawrence, either in search of new fishing grounds or simply because they were pushed in that direction by prolonged bad weather. A strait known as the Baye des Chasteaulx (Stait of Belle Isle) could possibly lead, like the passage discovered by Magellan in Tierra del Fuego, to the eastern sea that he had named the Pacific Ocean. Jacques Cartier, a Breton mariner of Saint-Malo, was instructed by the king of France to renew the search for a passage to Cathay and to discover new lands. Cartier, at 43 years old, was known as "Capitaine et Pilote pour le roi."6 On 20 April 1534 he left Saint-Malo with two ships and 60 men, and reached Cape Bonavista in Newfoundland on 10 May. Cartier then proceeded, for the next two months, on a systematic exploration of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.7 Cartier’s mandate from the French Crown was "faire le voyage de ce royaume es Terres Neufves pour descouvrir certaines ysles et pays où l’on dit qu’il se doibt trouver grant quantité d’or et autres riches choses" and "de voiaiger et allez aux Terres-Neuffves passez le destroict de la baye des Chasteaulx."8 He was ordered to sail beyond the Strait of Belle Isle in the hope of finding, in an area known as the Grant baye, a northwest passage to Asia.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 16 As noted by Selma Barkham, "Previous Breton voyages had pioneered the Strait of Belle Isle for cod-fishing, and gradually French Basques, following the Breton lead, appear to have brought back reports of fabulous whaling grounds."9 Fishermen were certainly already frequenting the Strait of Belle Isle, and Cartier’s meeting with a large ship from La Rochelle in that area gives evidence of such activity. In his narrative, Cartier also wrote about a busy fishing harbour known as les Ilettes. Study of the early toponymy and documentary references shows that mariners from Finistère were among the precursors in the Strait of Belle Isle.10 It is, however, only after Cartier’s voyage of 1534 that the Gulf of St. Lawrence makes its first appearance in early cartography.11 After passing through the Strait of Belle Isle, Cartier then sailed south along the west coast of the island of Newfoundland and reached the Magdalen Islands and the northern part of Prince Edward Island. He continued his exploration along the coast of New Brunswick without entering the Northumberland Strait and finally caught sight of the northern point of Miscou Island, which he named Cap d’Esperance. Opposite to it, when Cartier and his mariners looked to the north and one point (11.25 degrees) to the northeast they saw a cape and other lands in the distance.12 The cape was the reddish wall of rock forming the upper part of Mont Sainte-Anne,13 which rises abruptly to 340 metres behind the present locality of Percé. The other lands were the summits of the surrounding hills in the same area, also relatively close to shore. Here Cartier observed a wide expanse of water, possibly leading to a passage open to the west.14

7 Taking shelter in a cove that he named la Conche Sainct Martin (Port-Daniel), Cartier explored Baie des Chaleurs with two longboats and found out there was no passage such as the one for which he was searching. At Pointe Tracadigache,15 Cartier and his crewmen met with members of the Mi’kmaq, whose numbers at that place he estimated at more than 300 persons (men, women, and children). Cartier’s narrative observed that these Mi’kmaq went from place to place in canoes catching fish in the summer season for food, and that, despite their superior numbers, they were friendly and willing to trade. Mi’kmaw groups had already had direct contact with European explorers and fishermen on the Atlantic shores, and this area of Baie des Chaleurs was the northern part of the vast Mi’kmaw territory.16

8 Disappointed, and certain that there was no passage through this bay, the two ships hoisted their sails and left Conche Sainct Martin on Sunday, 12 July 1534:

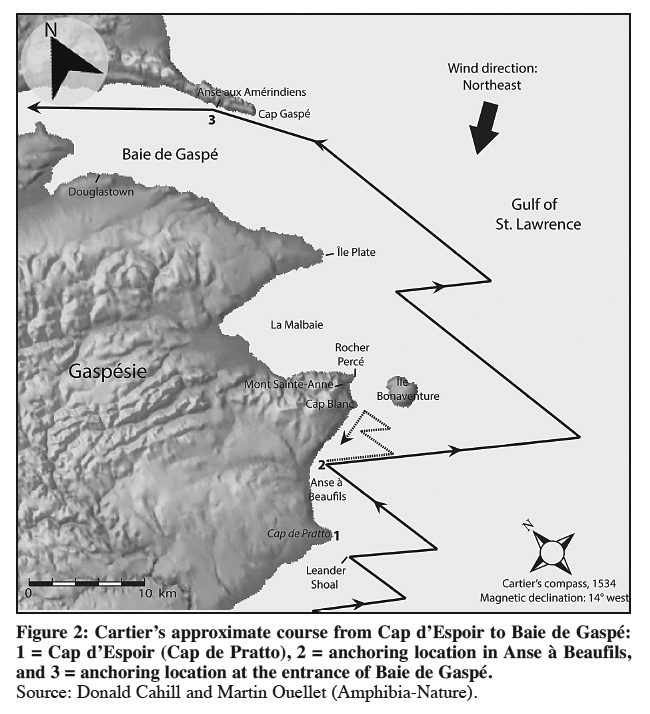

They sailed east some 18 leagues along the coast, as far as Cap de Pratto. And there, they found extraordinary tidal current, shallow water, and a very rough sea. They considered it preferable to hug the shore between the cape and an island, which lay approximately one league east of it, where they dropped anchor for the night. The next morning, at daybreak, they sailed with the intention of continuing to follow the coast, which now ran north-northeast, but strong headwinds prompted them to anchor again at the same spot they had left previously. They remained there that day and night, and then sailed on the following morning (Tuesday, 14 July), until they came abreast of a river lying 5 or 6 leagues north of the cape.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 29 There is a controversy among historians over exactly which cape was Cartier’s Cap de Pratto, and over the meaning and origin of the word itself.20 There are also diverse opinions as to whether Cartier named it or whether the name is older than Cartier’s first voyage. In order to identify clearly which cape it was, it is important not to rely solely on distances given by Cartier in his account but to also carefully examine other important pieces of evidence such as his compass headings, descriptions of geographical features, and soundings as well as the state of the sea and the weather conditions.

10 The essence of navigation in this era was dead-reckoning, which means "plotting your course and position on a chart from the three elements of direction, time, and speed."21 A precise measurement of the distance travelled required knowledge of the ship’s speed. Among the problems involved was an inability to measure time precisely, compounded by having only an approximate knowledge of the speed of currents. Cartier had no chip log or other reliable method of measuring accurately the speed of his vessels,22 and he frequently used the word "environ" (approximately) when giving a distance travelled. For all that, Ganong rightly observed "His few soundings, matched on our charts, are surprisingly accurate. His compass directions, of course always magnetic, are rarely much in error, and in cases we have reason to suspect a vagary of copyists. He was least successful in his distances, which, in absence of the log or equivalent, could be nothing but estimations."23 His accounts of distance were estimations certainly, but more than just guesswork. Cartier and his pilots were skilled and experienced navigators and an error of one or two leagues is quite acceptable when sailing uncharted water with 16th century crude instruments, especially when confronted by bad weather conditions, strong tidal currents, and poor visibility.24

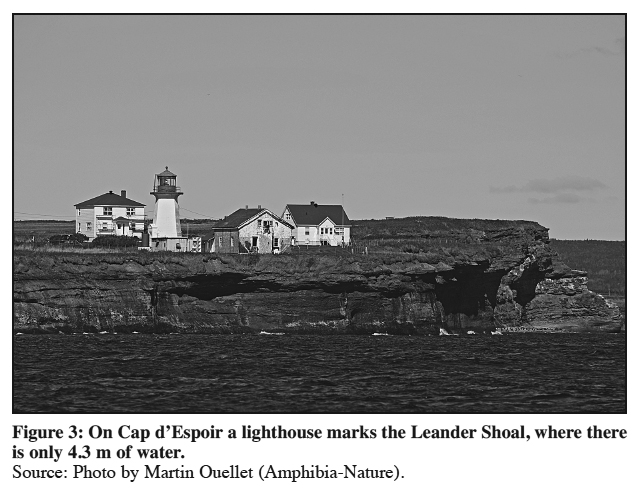

11 One of the most important things a pilot must know is the depth of water under the vessel’s keel. Sailing unknown coastal waters, Cartier’s men were constantly taking soundings with their leadline, a precise and reliable instrument when properly operated. When he left Conche Sainct Martin Cartier travelled approximately 18 leagues (some 56 km), and at Cap de Pratto his soundings, which were accurate, warned him of an area of shallow water (petit fontz).25 We believe that Cartier’s petit fontz was Leander Shoal (Haut-fond Leander), which lies 1.5 nautical miles (2.8 km) off Cap d’Espoir. The stretch of water between Port-Daniel and Percé is free from danger except at Leander Shoal where that the water depth changes suddenly, measuring only 14 feet (4.3 m).26 Leander Shoal is well known to local mariners and is best avoided in rough weather. It is considered a difficult area, especially for small craft,27 and presents a danger of grounding for large vessels with deep draught. At Leander Shoal, facing adverse winds and bad seas,28 Cartier decided to sail closer to shore between Cap de Pratto and an island approximately one league east of it in order to anchor for the night. This island is unanimously identified by historians as Île Bonaventure.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 312 The manoeuvre described here by Cartier is quite clear. He took shelter in the cove of Anse à Beaufils, partially protected by the headland of Cap Blanc. Our conclusion is that Cap de Pratto is Cap d’Espoir.29 The Rocher Percé cannot be considered as Cap de Pratto, as the Île Bonaventure lay between south and south-southeast of the rock when using Cartier’s compass.30 The channel between Île Bonaventure and Cap Blanc or Rocher Percé cannot be considered as shallow, the depth of water varying between 11 and 20 fathoms (20 and 37 m), as it is deep enough to accommodate even today’s largest ships.31 Moreover, Cartier’s narratives identified Cap de Pratto as the entrance of Baie des Chaleurs32 and also informed us that this bay runs east-northeast and west-southwest.33 We cannot consider the Rocher Percé or Cap Blanc as the entrance of Baie des Chaleurs and, following Cartier’s compass, it is at Cap d’Espoir that the coastline takes an east-northeast and west-southwest orientation.34

13 On Monday, 13 July, at daybreak, Cartier’s ships left the cove of Anse à Beaufils with the intention of following the coast. It ran north-northeast, which suits the orientation of the coast between Cap Blanc and Rocher Percé. But at Cap Blanc, strong northeasterly winds prevented them from sailing any further and so they had to anchor again, for the rest of the day, in the cove of Anse à Beaufils. It was not possible for Cartier to sail through the channel between Percé and Île Bonaventure against strong northeast or north-northeast winds with his ships. If a sailing ship wishes to proceed in the direction from which the wind is blowing, it is necessary to follow a zigzag course, known as tacking. Square-rigged ships could not come closer to the wind than six points (roughly 60 degrees). This meant that there was a sector of 12 points where the wind was contrary.35 In the narrow channel between Percé and Île Bonaventure, any fresh breeze from the northeast invariably builds up big swells and breaking waves, and this also would have prevented Cartier’s ships from tacting into the wind.36 If Cartier could sail his ships through this difficult channel against strong headwinds, probably towing his longboats, nothing would prevent him from continuing his course for Baie de Gaspé. However, to sail against the wind, if it could be done at all, it was necessary to proceed with extended tacks.

14 So the next morning, this time not trying to follow the coast through the channel, the vessels aimed to get round Île Bonaventure and with a series of tacks they sailed five or six leagues (some 30 km) north of Cap de Pratto. What was then the meaning and origin of the word "pratto"? Some historians believe it to be a Spanish word meaning "meadow" that was given by anonymous Basque fishermen on early fishing voyage.37 The Spanish and Portuguese translation for meadow is prado.38 The absence of any concrete material evidence of fishermen presence on the Gaspé coast before Cartier’s exploration enjoins us to be sceptical about pre-Cartier fishing voyages in this area. Cartier was using an old French word – "prateau"39 – a "small meadow" (petit pré). As defined by Moisy, "Prat, du lat. pratum, se dit encore pour pré. En italien prato et en espagnol prado. Prat avait un diminutif, prateau. En provençal, ce diminutif est pradel ou pradet."40 The forms pratto and prato are possibly spelling variations of prateau in the narratives, or may have been taken from one of the numerous dialects of the time. The Desceliers world map of 1546 gives Cap de Prey. It seems that there were several words to describe a meadow or pré in old France.41 Two of these words were "prael" and "placel."42

15 For what reason did Cartier used the toponym Cap de Pratto to identify Cap d’Espoir? Considering that this rocky coast was full of trees at that time, Cartier was not pointing to the existence of a meadow on these cliffs.43 We believe that Cartier used the word pratto as a nautical term, an equivalent of the word parcel used by the Portuguese mariners of the early 16th century – that is, a word that designated a shoal or a bank – an area of shallow water where navigation could be hazardous in bad weather.44 Since Leander Shoal is a bank of very small size, Cartier seemingly used the word pratto as a diminutive form of the Portuguese parcel or the French placel.45 In this regard, it is well worth noting that Cartier knew the Portuguese language.46 When scrutinizing the two narratives of Cartier, we observe that he had several nautical words to describe a reef or a bank close to the surface: "bastures," "basses," "hesiers," "bancq," "arasiffes," and "plateys." But to describe a small underwater bank like the Leander Shoal, he seemed limited to petit fontz, as the words "bas-fond" or "haut-fond" were probably not in use in his time, or at least not known by him.47 It was part of Cartier’s duty, as master-pilot for the king, to make maps of his explorations and survey the hazard of navigation. Did Cartier name the cape himself? It is possible that early fishermen could have informed Cartier of the existence of a strait (Baie des Chaleurs) open to the west, but, since there is no documentary or historical evidence of European presence before Cartier in this area, we have to consider highly plausible that Cartier himself named the Cap de Pratto on his voyage of 1534.

16 The two ships then continued their exploration:

Sailing off the entrance of Baie de Gaspé, on Tuesday, 14 July, Cartier’s ships encountered such strong contrary winds, fog, and poor visibility that they were forced to seek shelter inside the bay. These conditions, and the course he had sailed round Île Bonaventure, explain why Cartier made no description of remarkable features such as Rocher Percé, Mont Sainte-Anne, Pic de l’Aurore, La Malbaie, Cap Gaspé, or Rocher La Vieille.49 They undoubtedly anchored somewhere between Cap Gaspé and Anse aux Amérindiens (formerly Anse aux Sauvages), temporarily protected by the high cliffs of Cap Gaspé,50 to wait for better weather and make ready to set sail. They remained anchored near the entrance of Baie de Gaspé until the 16th, when the wind increased to such an extent that one of the ships lost an anchor.

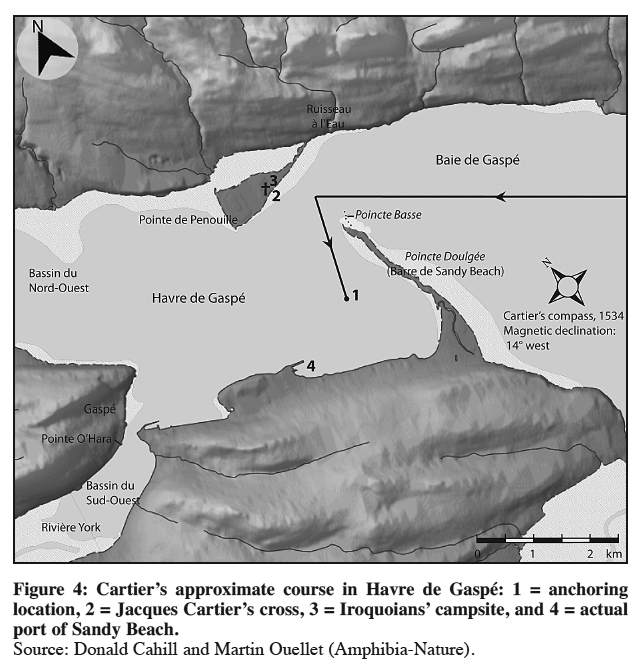

17 To be sure, the expedition was not seriously compromised by the loss of one anchor. As noted by Proulx: "L’inventaire de la ‘Michèle’ de 120 tonneaux indique quatre ancres; c’est aussi le cas de la ‘Marie-Johan’ de Bordeaux de 80 tonneaux. Le vaisseau ‘l’Hermine’ de 500 tonneaux en compte six mais il n’y en a que quatre sur la ‘Barbe,’ pendant qu’un navire de 39 pieds de quille et un tonnage sans doute inférieur à 70 tonneaux n’en possède que trois."51 The anchor was one of the vital pieces of equipment of every sailing ship. The number of anchors carried aboard varied, depending on the size of the ship. Cartier’s 60-ton ships would have carried at least three to four anchors each.52 Yet the loss of one anchor indicated that Cartier’s crew was dealing with a significant storm, with thick fog and strong easterly or southeasterly winds causing heavy swells in the bay. They had to leave that precarious and unreliable anchorage in 17 fathoms (31 m) of water. They took shelter 7 or 8 leagues (some 21 km) farther into the bay (a mere estimation in such conditions of fog, rain, and wind), in a good and safe harbour that they had previously explored with their longboats. Cartier brought his ships behind the sand bar of Sandy Beach, where they were in perfect safety, protected from the heavy swells and breaking waves then raging in the outer part of Baie de Gaspé.53

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 418 Where exactly did Cartier anchor his ships inside the sand bars of Sandy Beach and Pointe de Penouille? It is important to note that Havre de Gaspé, just inside the sand bars of Sandy Beach and Pointe de Penouille, was, and is still today one of the best harbours in North America. As an 18th-century author emphasized:

Cartier had no reason to steer his vessels through this intricate passage to Rivière York (Bassin du Sud-Ouest), taking the risk of running aground, while he was already in perfect safety in the harbour. They were in a better position in the harbour with more room to manoeuvre, and would have been almost ready to sail with a fair wind and good weather conditions. As the later surveyor Henry W. Bayfield would put it: "The admirable bay of Gaspé possesses advantages which may hereafter render it one of the most important places, in a maritime point of view, in these seas. It contains an excellent outer roadstead, off Douglastown; a harbour at its head, capable of holding a numerous fleet in perfect safety; and a basin where the largest ships might be hove down and refitted."55 It is reasonable to believe that Cartier anchored his two ships in Havre de Gaspé, southwest of the sand bar of Sandy Beach.

19 In his Cosmographie56 written in 1544, Jean Alfonse, who was pilot for Sieur de Roberval’s expedition of 1542, gave a detailed description of the sailing directions to enter the harbour and indicated exactly where to anchor. Alfonse, a contemporary of Jacques Cartier, was considered an expert mariner in his time:

There is no ambiguity in Alfonse’s indications to enter Havre de Gaspé. You must keep your vessel on the north side to avoid a shoal, poincte Basse, which lies to the southwest. This poincte Basse58 was a spit of sand extending underwater at the northern extremity of the sand bar of Sandy Beach.59 This underwater shoal was still considered as a danger in 1847, and Purdy and Findlay gave the same advice as Alfonse in their sailing directions. They warned mariners always to "beware of the south point entrance [Sandy Beach], off which the shoal water extends to some distance," and added that "in rounding the point of beach, give it a berth of a quarter of a mile, in order to avoid a shallow spit which extends from it."60

20 Continuing with Alfonse’s indications, once the poincte Basse is clear you must steer your vessel toward the south shore [Sandy Beach hamlet] keeping poincte Doulgée a distance of two cables length61 on your port side (left side); then you may drop anchor in the southwest of the cove in 15 brasses (25 m; near the actual port of Sandy Beach). This text indicates clearly that poincte Doulgée was the first name given to the actual sand bar of Sandy Beach. This old French word "doulgée" – means delicate and fine – and describes perfectly this remarkable sand bar.62 It could have been named by Cartier, early fishermen, or by Alfonse himself. Alfonse’s instruction to enter Havre de Gaspé matches perfectly those given by Captain Bayfield 300 years later in his sailing directions. A map of 1778-1781, made by Des Barres, a military engineer and surveyor for the British Admiralty, shows an area of 13 to 15 fathoms (23 to 27 m) in the southwest of the cove of Sandy Beach.63 Water depths in Rivière York’s Basin, between 5 to 9 fathoms (9 to 16 m), do not match Alfonse’s anchoring location.

Display large image of Figure 5

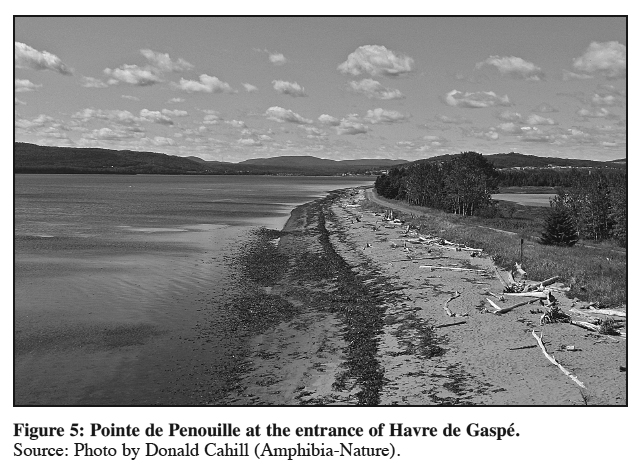

Display large image of Figure 521 It was at this time, in mid-July, that Cartier’s crew met with St. Lawrence Iroquoians64 who lived along the shore of the St. Lawrence River Valley. More than 200 persons (men, women, as well as children) had travelled to Havre de Gaspé to fish for mackerel, of which there was a great abundance. Cartier’s account mentions seeing a large quantity of mackerel, which the Natives caught close to shore with nets.65 On his map of Baie de Gaspé, Captain Thomas Bell, who was secretary and aide-de-camp to General Wolfe, noted about Sandy Beach: "Part of Sand Bank dry at high water; fine mackrell on it."66 The prevalence of these fish in this area is confirmed by Pierre Fortin’s later account. On his way to Sandy Beach aboard his ship’s boat in the summer of 1857, Fortin came across some 20 boats, line-fishing for what he described as an abundance of mackerel in this part of Baie de Gaspé.67 The Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus) is a salt-water fish that never penetrates into fresh water, so the area surrounding the channel between Sandy Beach and Pointe de Penouille was certainly the best spot for the Iroquoians to spread their fishing nets. The most probable location for the Iroquoians’ campsite was not on the narrow isolated sand bar of Sandy Beach, but on Pointe de Penouille at the entrance of the harbour. There, they had a small wooded area accessible for fire and shelter,68 they were close to their fishing grounds, they had access to a stream of fresh water close by (Ruisseau à l’Eau), and they were also in a strategic position with a broad view of the entire Baie de Gaspé.69

22 On 24 July, a cross was raised at the entrance of the harbour:

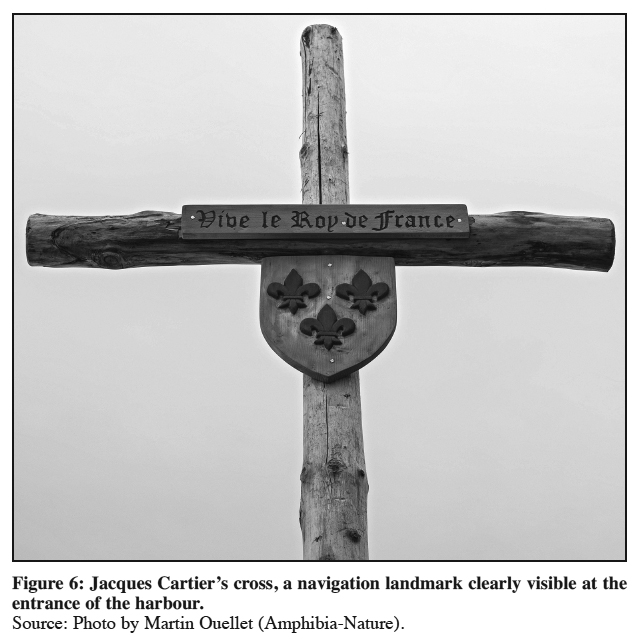

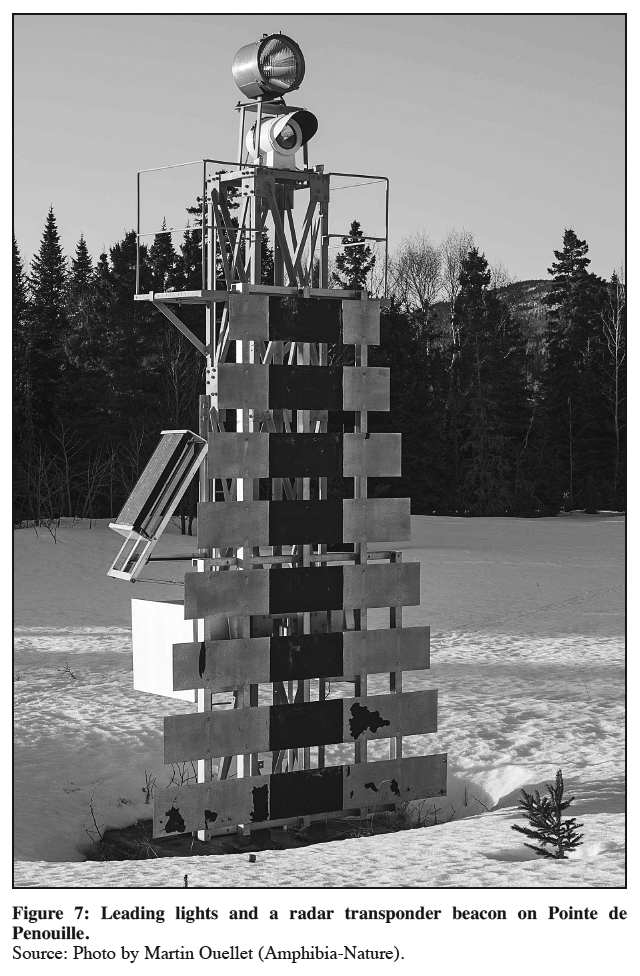

We believe that Jacques Cartier and his crewmen erected the 30-foot (9-m) wooden cross on Pointe de Penouille, right next to the Iroquoians’ encampment, and its essential purpose was to serve as a navigation landmark, a guide for mariners to enter Havre de Gaspé safely.71 The instructions to enter the harbour given by Captain Bayfield’s sailing directions also tend to confirm this conclusion.72 The landmark’s alignment on Bayfield’s map of Gaspé Harbour and Gaspé Basin of 1838 can also help us determine the approximate location where the cross would have been useful as a landmark on Pointe de Penouille. Clearly visible at the entrance of the harbour, the cross could also have made a strong political statement on behalf of the king of France. More than 480 years after Jacques Cartier’s voyage, leading lights and a radar transponder beacon are located on Pointe de Penouille for the safety of modern mariners and commercial shipping.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 623 The objective of this research note is to bring to bear a new examination of Jacques Cartier’s exploration of the Gaspé coast in 1534. The Relations attributed to Jacques Cartier give us the first description of many areas of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and its Indigenous people in the early decades of the 16th century. It is highly plausible that Jacques Cartier and his crewmen were the first Europeans to sail the Gaspé coast, and we believe it is reasonable to consider his Cap de Pratto as Cap d’Espoir. Bad weather conditions and strong adverse winds forced Cartier’s ships to sail round Île Bonaventure and seek shelter inside Havre de Gaspé, perfectly protected by the poincte Doulgée (now called barre de Sandy Beach). It was during those days spent among the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, in a territory they called Honguedo, that Cartier and his crewmen erected a nine-metre wooden cross on Pointe de Penouille to serve as a navigation landmark.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 724 The cross, on which they hung a shield with the Fleurs de Lys and the inscription "Vive le Roy de France," was also a strong affirmation of France’s intentions for this territory. The raising of the cross may indicate that the Gaspé Peninsula and its immediate surroundings were not frequented by Spanish or Portuguese fishermen and were considered as new lands to be discovered.73 The first appearance of the Gulf of St. Lawrence in early cartography was based on Cartier’s narratives and on his – now lost – original maps.74 During a second voyage in 1535, Cartier continued his exploration up to the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, but he did not find a western passage to Asia nor precious metals. The first contact and trade he established with the St. Lawrence Iroquoians at Gaspé in 1534 would end in incomprehension, mistrust, and conflict during this second voyage.

25 Cartier’s expeditions, though not resulting in immediate benefits, had opened a new and vast country for the Kingdom of France. The Iroquoians, by contrast, would ultimately disappear as a group from the St. Lawrence River Valley. How, why, and when exactly this took place is highly debatable.75 The rich fishing grounds of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and their adjacent shores were henceforth exploited for the development of the dry-cod fishery.76 By the end of the 16th century, this waterway giving access to the hinterland would also prove profitable with the establishment of the fur trade industry, and eventually the colonization of a new territory called Nouvelle-France.77