Articles

Mi’kmaw Women and St. Francis Xavier University’s Micmac Community Development Program, 1958-1970

Between 1958 and 1970 the St. Francis Xavier Extension Department operated the Micmac Community Development Program (MCDP), which aimed to bring economic development and adult education programs to Mi’kmaw communities. The MCDP had a complicated place in the lives of Mi’kmaw women. In its acceptance of racialized visions of Mi’kmaw women, its emphasis on feminine domesticity, and in its willingness to monitor Mi’kmaw families, the MCDP served the gendered and assimilative agenda of the federal state. However, its community development projects and rights-centred rhetoric also provided some Mi’kmaw women opportunities to challenge a legacy of isolating and silencing colonialism.

Entre 1958 et 1970, l’Extension de l’enseignement de la St. Francis Xavier University a géré le Micmac Community Development Program (MCDP), qui visait à offrir des programmes de développement économique et d’éducation des adultes aux communautés mi’kmaq. Le MCDP jouait un rôle complexe dans la vie des femmes mi’kmaq. Par son acceptation de visions racialisées des femmes mi’kmaq, son insistance sur la domesticité féminine et sa volonté de surveiller les familles mi’kmaq, il servait les objectifs sexistes et assimilateurs de l’État fédéral. Cependant, ses projets de développement communautaire et sa rhétorique centrée sur les droits ont aussi donné à certaines femmes mi’kmaq la possibilité de remettre en question l’héritage d’un colonialisme qui avait pour effet d’isoler et de réduire au silence.

1 BETWEEN 1958 AND 1970, THE ST. FRANCIS XAVIER (ST. FX) Extension Department implemented the Micmac Community Development Program (MCDP) in northeastern Nova Scotian Mi’kmaw communities. It aimed to foster economic development through adult education and grassroots self-help. Its identification of males as the driving forces of economic improvement meant that the MCDP was founded with the primary intent of engaging Mi’kmaw men. However, when men’s participation unexpectedly fell short, the Extension Department welcomed Mi’kmaw women as participants in community development initiatives. These women came to occupy an important, complex, and at times contradictory place in this program. To a significant extent, the MCDP functioned as an extension of the colonial state as it perpetuated mid-20th century assumptions about Indigenous people, particularly Indigenous women, and facilitated state interventions in the lives of Mi’kmaw women and their families. However, by giving Mi’kmaw women opportunities for collective organizing, by encouraging their public activities, and by placing them in the public limelight as spokespersons for their communities, the MCDP contravened its own colonial perspective and agenda. Through it, Mi’kmaw women found strategies to undercut a colonialist legacy that had long served to isolate and silence them.

2 The Micmac Community Development Program was modeled on St. Francis Xavier University’s Antigonish Movement. With the goal of alleviating the poverty that faced rural fishing villages that had been blindsided by the rise of industrial capitalism, St. FX faculty, many of whom were Roman Catholic clergy, in 1928 founded the university’s Extension Department under the directorship of Fr. Moses Coady. Armed with a “you can do it” attitude, Extension Department staff preached a message of community empowerment – encouraging rural Nova Scotians to organize themselves to mediate the economic difficulties they faced. Through programs of adult education as well as the establishment of credit unions, consumer co-operatives, producer co-operatives, and co-operative wholesaling, the Antigonish Movement brought economic relief to tens of thousands of people in struggling rural communities.1

3 The Antigonish Movement, though, belonged to people of European descent. Moses Coady’s own 1939 account of the movement, Masters of their Own Destiny: The Story of the Antigonish Movement of Adult Education Through Economic Cooperation, explicitly identified the “the people” of the movement as Nova Scotia’s Scottish, Irish, and the French “pioneers” whose “common problems and difficulties . . . [have] tended to fuse them so that they are now Canadians first and Scottish, Irish, or French second.”2 Although boasting a principle of human equality, the Eurocentric bias of the Antigonish Movement meant that it, like Coady’s account of it, ignored the Mi’kmaq even though their Roman Catholicism, impoverishment, and location in rural northeastern Nova Scotia very much aligned them with other communities engaged in the movement.3

4 While the jurisdictional positioning of the Mi’kmaq as “Indian” wards of the federal state might have contributed to their omission, it seems likely that racialized ideas held by architects of the Antigonish Movement, including Coady, also supported their exclusion. In a rare statement concerning the Mi’kmaq, Coady articulated assumptions that aligned him with the ethnocentrism of his age while also reflecting the tendency, before the “left turn” of the post-Second World War era, to blame Indigenous people’s economic struggles on “Native values” that were regarded as being both anathematic to progress and unalterable.4 Seeking to understand the cause of the economic malaise affecting the region in 1935, Coady asserted that a general “lack of education and consequent inactivity and lethargy of the people” undermined the region’s prosperity. As he continued, Coady specifically criticized the Mi’kmaq: “I agree that fundamentally economic causes are responsible for a lot of things, but forty million MicMacs in the British Isles . . . would not have resulted in much of a civilization.”5 Coady appears to have believed that the Mi’kmaq, as a people, were fundamentally incapable of the “you can do it” attitude required of the Antigonish Movement.

5 Only after the Second World War did the Extension Department expand its work into Mi’kmaw communities, a redirection inspired by a number of factors. A general softening of non-Indigenous Canadians’ attitudes toward Indigenous people seems to have created a climate within which the Extension Department became more inclined to work with Mi’kmaw communities. And while events of the Second World War generated new empathy among Canadians for the plight of Indigenous people in Canada, emerging social science theories that emphasized how malleable environmental circumstances, not innate racial traits, were to blame for difficulties faced by Indigenous communities began to shape public perceptions and state policies.6 These shifting perspectives inspired the St. FX Extension Department to turn its attention to issues facing Mi’kmaw communities.7 Also fostering interest in Mi’kmaw communities was a crisis of purpose within the Antigonish Movement as wartime economic growth and the post-war emergence of the welfare state undercut the rural poverty that had been the raison d’être of the movement. The MCDP was not the only means by which St. FX sought out new communities in need of assistance during the late 1950s. In 1959, just as the MCDP was under way, St. FX established the Coady International Institute to spread Antigonish Movement ideas about adult education and community-based development to people in “developing” areas around the globe. Newly inclined to work with non-Euro-Canadian populations both at home and abroad, and compelled to seek out new target communities, Extension Department staff for the first time turned their professional attention to Mi’kmaw communities.

6 These communities were appropriate clients of the Extension Department. Located within the orbit of the St. FX Extension Department, they faced staggering levels of poverty. Moreover, their long heritage of economic malaise, occasioned by the confinement of the Mi’kmaq to inadequate, isolated, and dwindling reserve lands, as well as the faltering markets for Mi’kmaw handcrafts and a reduction in Mi’kmaq access to natural resources due to increasing state interference, was compounded in the first half of the 20th century by a series of relocations of northeastern Nova Scotia Mi’kmaw communities.8 In the 1920s, two decades of discord between residents of a Mi’kmaw reserve located on King’s Road in Sydney and non-Indigenous Sydney residents who coveted reserve land came to an end. The federal government, which sided with Sydney residents, was tasked with negotiating the dispute via an Exchequer Court hearing. The Mi’kmaw community was removed, against the wishes of many residents, from its attractive urban harbour- side location to Membertou, a less desirable site on the outskirts of the industrial city.9 The 1940s witnessed a wider relocation initiative as the federal government, again using coercive tactics, “centralized” Nova Scotia’s Mi’kmaq. By the end of the process, about half of the province’s Mi’kmaw population lived at one of the two “modern” federal Indian reserves – Indian Brook, near Shubenacadie on the mainland, and Eskasoni, on Cape Breton Island.10 While these relocations were nominally intended to improve the financial situations of Mi’kmaw communities, they only worsened the conditions of the many relocated families who were trapped in overcrowded communities that lacked employment opportunities, adequate housing, natural resources, and water services.

7 By the time that the Extension Department was seeking new outlets for its work following the Second World War, Mi’kmaw communities in Nova Scotia were in dire economic straits. The poverty facing Mi’kmaq living on Cape Breton reservations at this time was recounted in meetings of a special joint committee that investigated Indian Affairs between 1959 and 1961. In 1960, a report from Chapel Island informed this committee that “our Reserve for the past two years has witnessed serious unemployment and destitution” while the community at Wagmatcook lamented that many families were “living in shacks unfit for human habitation.” The band council at Eskasoni, one of the communities transformed by centralization in the 1940s, emphasized “incomes are very low and inadequate to meet living requirements.” 11 Centralization’s negative ramifications continued to be felt at Eskasoni, and six years later, in 1966, a report of the Community Planning and Improvement Committee of the Eskasoni Band Council stated:

It was within this context of economic malaise that the Membertou band council in 1957 sent a request to the St. FX Extension Department for assistance in “outlining and promoting a study program for the reserve” at Membertou, a community that, even three decades after its relocation from King’s Road, lacked basic water and sewerage services.13 Federal officials, some of whom were advocating a community development model of Indian reserve administration, also offered words of support; but to the chagrin of the Extension Department they stopped short of funding the initiative, which was christened the MCDP.14

8 Borrowing from the playbook of the Antigonish Movement, the MCDP initially featured two components: annual residential short courses held at Margaree exclusively for Mi’kmaw delegates on the western side of Cape Breton Island and a series of on-reserve community development initiatives, including adult education and economic development projects.15 In 1964, Ottawa assumed the cost of administering the MCDP. This move, which followed intense lobbying by the Extension Department, coincided with the creation of a short-lived and controversial Community Development program by the Indian Affairs Branch (IAB), the federal agency responsible for overseeing Canadian “Indian” policy.16 With this partnership in place, the Extension Department retained control over staffing and day-to-day operations but accepted new accountability to the IAB in the form of regular progress reports and meetings with IAB officials.17 An Extension Report of March 1964 explained the autonomy and overlap of the Extension Department in the new relationship with Ottawa, noting that while the objectives of the MCDP “correspond with aims and practices presently promoted by Indian Affairs . . . it is not the intention of St. F. X. Extension to duplicate the efforts of Indian Affairs’ personnel presently in the field, but to perform a liaison and catalytic function wherever the occasion presents itself.”18 By the end of the 1960s, four full-time and several part-time fieldworkers from the Extension Department were at work at five Cape Breton reserves and two on the northern Nova Scotia mainland. These fieldworkers were paid by, and regularly reported to, the IAB.19 By this time, the Margaree short courses had fallen from favour (the last one being held in 1963), and the MCDP, armed with the Antigonish Movement mantra of teaching people to “help themselves,” was fixed on a loosely defined program of on-reserve development initiatives that emphasized “Indians’ readiness to participate voluntarily in their formulation and implementation.”20

9 Mi’kmaw women figured prominently in the MCDP in highly gendered ways that harkened back to the Antigonish Movement – a movement overseen by Roman Catholic men who held deeply engrained assumptions about women’s places in society. Ideologically conservative and imbued with Roman Catholic doctrine, the Antigonish Movement was starkly antifeminist. As historian Rusty Neal has argued, the Antigonish Movement’s mantra of universal equality was undermined not only by its Eurocentrism but also by its subjugation of women.21 Women’s involvement in the movement was limited to their roles as homemakers and household consumers, a status quo that was endorsed by both male leadership and female fieldworkers.22

10 Mi’kmaw women’s place in the MCDP was defined in a similar way to that of non- Indigenous women in the earlier Antigonish Movement. Depicted as poor, rural women, Mi’kmaw women were characterized as defenders of the home and were tasked with facilitating community economic growth by embracing middle class ideals of household management and child rearing. The MCDP initially believed that while Mi’kmaw men would be responsible for economic development, which was the central focus of the program, Mi’kmaw women’s involvement would be limited to the domestic realm. The short course programs that predominated in the MCDP’s early years saw men “debate the major problem of employment which concerns them chiefly” while the women discussed “their role as homemakers.”23 As with the earlier Antigonish Movement, female MCDP fieldworkers did not openly challenge such subordinating views of femininity.24 Neither did they openly protest the pay differential that saw them earn $4,800 per year to their male counterparts’ annual salaries of $7,000.25 The collaboration of the IAB beginning in 1964 affirmed the MCDP’s initial gendered predilections and meshed with Ottawa’s long commitment to imparting to Indigenous people the gender ideals associated with Eurocanadian society.26 Joan Sangster’s observation that Indian Affairs’ economic undertakings in Indigenous communities “imagined male breadwinners as the answer” and saw women’s work as “ancillary” was certainly true of the MCDP, which downplayed Mi’kmaw women’s wage-earning potential and treated women’s work as supplemental to men’s family wages.27

11 In addition to being subjected to a gender bias characteristic of the Antigonish Movement, Mi’kmaw women involved in the MCDP were, as “Indians,” also objects of a racialized scrutiny that secured for them a particular gendered role in the project. The St. FX Extension Department included a number of non-Indigenous female fieldworkers assigned to work with Mi’kmaw women. Holding positions that in some ways echoed those of the professional social workers studied by Karen Tice, Extension Department fieldworkers maintained case records although they seem to have been neither tutored in professional standards nor particularly consistent in their record- keeping.28 Although most of their records were general and perfunctory statements about daily schedules and activities, on several occasions fieldworkers’ case notes offered up more candid and intimate details of specific Mi’kmaw women’s lives. One set of field notes, for example, offered a particularly strong critique of the moral and maternal capacities of one specific Mi’kmaw woman. Referring to her as “rather lacking in intelligence,” the fieldworker criticized the woman’s alleged sexual indiscretions by noting that she had a “reputation for running around, although she denies guilt of it.” The fieldworker continued with a critique of the woman’s maternal capabilities, observing that this mother not only did “not care for the children and barely saved them from being taken by Children’s Aid” but that her neglect imperilled the health of her children who, it was noted, must be “watched for Impetigo and other communicable diseases.” The fieldworker concluded: “There is no doubt that the children have suffered from their home environment.”29 Such records reveal fieldworkers’ consistent acceptance of, and willingness to reinforce, negative stereotypes of Indigenous femininity, which presumed Indigenous women’s innate predispositions to domestic ineptitude and home-destabilizing sexual immorality.30

12 These racialized characterizations of Mi’kmaw women that infiltrated the MCDP in the 1960s were neither new to that era nor unique to the Extension Department. Such attitudes had a very long pedigree in both federal Indian policy and in public discourse. They were, for example, highlighted in northeastern Nova Scotia in the early decades of the 20th century as they informed the debate and the Exchequer Court hearing surrounding the relocation of the King’s Road Reserve in Sydney. Drawing on well-worn stereotypes of “squaws,” a word used by supporters of the community’s relocation, it was alleged that Mi’kmaw women were not only bereft of the domestic skills required to maintain a hygienic, healthy community but were also intemperate and sexually promiscuous. Mi’kmaw women’s alleged slovenliness, intemperance, and immorality were presented as threats to the physical and moral well-being of the non-Indigenous residents of Sydney.31 Although these unflattering portrayals of Mi’kmaw women did not go uncontested, they nevertheless served to justify the federal court’s decision, which was adopted by the IAB, to remove the King’s Road community against the wishes of many community members.32 This same conceptualization of Indigenous women was also the ideological footing of other federal programs. For example, as Kristin Burnett has shown, a public health regime established on Indian reserves in Canada in the second decade of the 20th century linked claims of Indigenous women’s inadequate household management to ill health, child mortality, and other public health issues.33 These ideas were also at the heart of a national network of state-encouraged Native homemakers’ clubs that first emerged in the 1930s and clearly influenced the work of the MCDP. These homemaker clubs, like the MCDP with its fixation on domesticity, supported the conclusion that Indigenous women were the cause of the deplorable conditions prevailing in their communities and, thus, should also be the source of its remedy.34

13 This vision of Mi’kmaw women and the focus on their domesticity meant that the overriding – and remarkably unwavering – stated objective of the MCDP was the promotion of “a home management program in the Indian homes [and] . . . improved housekeeping practices.”35 Consequently, the content of the Margaree short courses that dominated the early years of the program was highly gendered. Short-course programs for men focussed on issues of community economic development and governance, while women were instructed in domestic matters such as housekeeping, nutrition, and childrearing. At the first short course held at Margaree in October 1959, for example, the 15 women in attendance took part in sessions that emphasized their responsibilities as homemakers and mothers. The women viewed a film entitled “Food For Freddy” and, joined by a provincial nutritionist, discussed such matters as “the necessity of eating the foods recommended in Canada’s Food Rules” and rules for economical, but nutritious, grocery shopping. Female participants were also entreated to consider “What could you do to make your kitchen more pleasant for the family?” and were advised of their paramount role in the formation of their children’s character, particularly their duty to impart “the notion of modesty” to daughters. 36 Highly gendered programs also characterized the on-reserve activities that dominated the MCDP after 1964. The pronouncement of one female fieldworker that women of “all ethnic groups . . . from St. John’s to Vancouver . . . [desire to be] average North American homemaker[s]” reveals the central place that domestic training for Mi’kmaw women had in the MCDP. 37

14 Given this objective, the primary task of female fieldworkers was to be what Karen Tice refers to as “professional friends”; in order to establish a rapport with Mi’kmaw families, they were to meet and chat with Mi’kmaw women in their own homes where they would, ideally, be privy to Mi’kmaw women’s “private concerns.”38 The

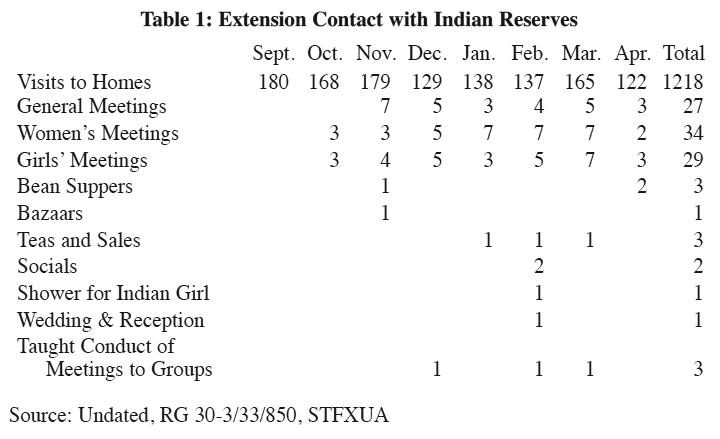

15 importance of women fieldworkers’ “intensive home visiting” campaign shines through in the activity reports of Extension Department workers. 39 The results of these visits appear in a few handwritten case notes, but most were summarized and appear in formal and typewritten summaries entitled “Progress Report.” An undated chart (see Table 1) reveals that between September and April of an unspecified year (probably 1963-64), fieldworkers met with Mi’kmaw people a total of 1,322 times. Of these, 1,218 visits – or 92 per cent of all meetings – were home visits. The late-winter schedule of fieldworker Margaret Gillis was typical of her female colleagues and shows a similar emphasis on home visits. In February of 1961 Gillis spent 9 of her 16 days on reserves visiting women at home, while that March she spent 10 of her 14 days on the reserve engaged in home visits.40

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 116 Home visits allowed fieldworkers to instruct Mi’kmaw women, hands-on, in their domestic tasks. Lessons in nutrition, household budgeting, food preparation, and hygiene were intended to correct perceived flaws in Mi’kmaw women’s character and to provide a foundation for economic revival in Mi’kmaw communities by fostering frugality in homemaking while also creating well-adjusted children, who would become industrious citizens.41 Mi’kmaw women who were receptive to these lessons were championed in fieldworker reports. Fieldworker Effie MacIsaac, for example, heaped praise on one Mi’kmaw woman for being a “dedicated mother, an excellent housekeeper and manager, and during her marriage an excellent wife.” MacIsaac continued that it was thanks to this woman’s “patient quiet energy” that she raised 13 children “to have all the characteristics of future fine citizens.”42

17 This emphasis on Mi’kmaw women as homemakers and mothers had a tenacious grip on the MCDP despite the fact that the middle class brand of domesticity championed by fieldworkers was largely incompatible with conditions prevailing on poor northern and northeastern Nova Scotian reserves, many of which lacked sewage services and running water. Fieldworker Kathleen Malinowski identified this tension, writing in a 1962 report that while she felt that “I must work with the women to help them improve their housekeeping . . . I had to consider crowded quarters, poor sanitation, muddy yards, the lack of running water, and the absence of other comforts essential to good housekeeping.”43 Still, such a realization did not lead to a reorientation of the MCDP away from women’s domesticity.

18 The overweening emphasis on women’s domesticity was accompanied by fieldworkers’ failure to recognize the economic importance of women’s waged labour, an orientation that corresponds to a broader colonial tendency to cast Indigenous women as idle non-workers.44 By the 1950s, the waged work of Mi’kmaw women, primarily as domestics for middle class Euro-Nova Scotian families, had, perhaps, grown relatively more important to Mi’kmaw household economies as men struggled to find employment and as markets for men’s craft work in particular dried up rapidly in the wake of increased factory production.45 Fieldworkers, though, rarely acknowledged women’s waged labour and, when they did, they saw it not as an important source of income for household economies but rather as an impediment to women’s domestic roles. Lamented one fieldworker: “Some of the poorest kept houses on one reserve are those of women who go out to work at housekeeping.” The Extension Department’s emphasis on women’s domesticity (versus wage labour) persisted throughout the MCDP. In 1969 – the final year of the program – fieldworkers remained steadfast in their commitment to women’s homemaking skills and, concerned that such skills were still wanting, proposed that they be further fostered via the introduction of a “contest in home crafts awarding a good prize each month for the best kept home on the reserve.”46

19 In addition to inculcating an idealized female domesticity, home visits also served a surveillance function – one that appears to have grown over time, particularly once the IAB became involved. By the late 1960s, fieldworkers’ devotion to the Antigonish Movement mantra of “self-help” was competing with their position as informants to the Indian Affairs Branch that funded the MCDP in full after 1964. Fieldworkers’ contact with women in their homes gave them a venue of surveillance upon which the IAB was eager to draw. Through their reports, fieldworkers sometimes relayed confidential observations about individual women’s lives to their superiors at St. FX. When the IAB became involved in the MCDP in the mid-1960s, fieldworkers’ observations about matters such as finances, household hygiene, family relationships, pregnancies, and alcohol use were being used by the federal government to shape its policy response to Indigenous people.47 It is important to note that fieldworkers’ roles as agents of surveillance were not infallible. In 1968, for example, fieldworker Effie MacIsaac found her access to the reserve at Afton limited when community opposition to her presence meant that she was “no longer being invited to the meetings.”48 Likewise, it is difficult to ascertain fieldworkers’ commitment to surveillance. MCDP fieldworkers were employed primarily to establish a rapport with households and to coordinate programs in communities, and so reports, which were geared toward these goals, offer only slight evidence of their work as collectors of information. However, although their role as interlopers appears to have been secondary to other tasks, the knowledge fieldworkers gained via home visits always had the potential to be passed along to the IAB or other government agency.49 The Extension Department’s strong support for a partnership with Ottawa that was marked by IAB oversight seems to have been generally accepted by staff, including fieldworkers. The fieldworker who judged certain Mi’kmaw women in her jurisdiction to be “trustworthy sources of information” certainly seems to have accepted this task.50

20 As informants, fieldworkers revealed a general acceptance of stereotypes of Indigenous peoples and their belief that the Mi’kmaq – especially women – required increased intervention in their lives. Fieldworker reports are rife with judgements about the supposed shortcomings of Mi’kmaw society, particularly their alleged resistance to change. Kathleen Malinowski’s 1962 lamentation that because of the Mi’kmaq’s “way of life . . . [the] . . . process of change is understandably very slow” was typical.51 A 1966 report of fieldworker Effie MacIsaac offered a similar assessment, blaming the “ghastly conditions” prevailing at the reserves of Afton and Pictou Landing on residents themselves, and suggesting that “nothing [but laziness] is preventing these people from advancing in the Economic sense because work is available . . . for any man who wishes to work.” MacIsaac also considered alleged sexual indiscretions of “young Indian girls who frequently bear illegitimate children” to be a source of crisis in the communities. MacIsaac’s remedy to the problems facing the reserves rested on the inculcation of domesticity that featured so prominently in the MCDP. She suggested that the creation of “a sewing class for the women and the girls” and the offering of “a homemaking course for the women” would alleviate the community’s problems – including the recurrent “problem” of women’s character.52

21 Fieldworkers also occasionally served more directly interventionist surveillance functions that profoundly – and sometimes negatively – shaped Mi’kmaw women’s lives. For example, when fieldworker Elizabeth Tower in 1969 coordinated the psychological assessments of three Mi’kmaw women who were seeking to further their education through the federal Manpower Mobility Program (for which “Indian” people became eligible in 1965), her interventionist actions had the effect of reinforcing women’s domesticity even if this was not Tower’s intention.53 The fact that all three women were subjected to screening suggests that employment training was viewed as an exceptional life course for these women, in contrast to a more natural and acceptable path as homemaker. The assessments also served ultimately to limit the three women’s employment options; in all three cases an attending psychologist concluded that owing to unexplained “cultural factors” as well as to the educational limitations and supposed intellectual deficiencies of the subjects, none of the assessed women were appropriate candidates for higher learning.54 MacIsaac also endorsed greater state intervention along these lines when she lobbied for a psychologist to be employed to treat the various “Indian” pathologies she believed haunted Mi’kmaw reserves and undermined their economic success.55

22 The MCDP, following the lead of colonial policies of the federal state, emphasized Indigenous women’s flaws and demanded their careful scrutiny and the application of corrective middle class values surrounding domesticity and morality.56 However, the MCDP’s colonial mandate was murky and Extension Department workers also challenged key dictates of colonialism by championing both Mi’kmaw cultural validity and political autonomy.57 A foundational document of the MCDP, published in 1959 – a time at which the Extension Department was lobbying for but had yet to secure IAB funding – reveals the tension that existed within the program as it simultaneously promoted the agenda of the assimilative federal state while also challenging its key tenets. By adopting the prevailing and condescending perspective that the Mi’kmaq were “living aimless, inefficient and what we may call wasted lives,” the MCDP at times disregarded the political and cultural integrity of the Mi’kmaq. However, the Extension Department also called for Mi’kmaw political self-empowerment and urged the Mi’kmaq to “move forward with a new determination to develop themselves through their own groups, organizations and programs of action with outside direction but independently of the government.”58 In various contexts, including at the final Margaree short course held in 1963, the Mi’kmaq were also called upon to “find ways to preserve their language, their culture, their religion and their family style of life.”59 The formal merger of the MCDP with the IAB in 1964 created an interface for greater tensions between the MCDP’s acceptance of assimilation and its goal of promoting Mi’kmaw autonomy. While eager to be affiliated with the IAB (and its financial resources), the MCDP – and its employees – also chafed against the federal agency. In one episode in 1967, the then-director of the MCDP, Paul Jobe, wrote an angry letter concerning a testy visit that had apparently been paid to the St. FX Extension Department by Charles Reardon of the IAB. Though the nature of the conflict is not clear, it compelled Jobe to differentiate the work of the MCDP from that of the IAB and to assert his program’s autonomy. Insisting that “what you do in the field is none of my business, and what I do is none of yours,” Jobe also warned Reardon to “never under any circumstances enter my offices again.”60 This letter hints at the complex position of the MCDP, which was theoretically, at least, committed to fostering Mi’kmaw community independence. As one MCDP employee put it, “We attempt to work ourselves out of a job.” 61 At the same time, though, it was an organization that was willingly partnered with, and funded by, the IAB.62

23 This tension between reinforcing and challenging the colonial aims of the state was evident in the Extension Department’s work with women. Even while MCDP fieldworkers recycled stereotypes and accepted some surveillance role, their rhetoric of female domesticity did not reflect the full extent of the program’s work. The MCDP provided Mi’kmaw women with opportunities to engage in community projects in ways that released them from the confines of homes and the gazes of fieldworkers’ home visits in ways that subverted the colonialism that defined their lives. For their part, Mi’kmaw women took advantage of these opportunities while resisting what they viewed as unwarranted intrusion into their lives. Mi’kmaw women were initially intended to be subsidiary players in the MCDP, their roles limited to domestic space and removed from what was regarded as the more important realm of reserve economic development. However, when men proved reluctant to be involved – and when Mi’kmaw women showed considerable willingness to participate – women’s engagement emerged as the de facto focus of the program.63 As Table 1 suggests, women, who were the first lines of contact in the home visits that vastly dominated fieldworker activities, were far more likely than were men to interact with Extension Department staff. Apart from general meetings, which tended to feature matters of governance and economic development plans aimed at (but not limited to) men, most sites of Mi’kmaw-fieldworker interaction featured women and girls.

24 Ironically, the Extension Department first expanded its work with women in an effort to attract men to its programs. Like generations of missionaries and government officials before them, fieldworkers recognized that women were effective “change agents” and they knew that coveted bonds with men might be established by winning over women.64 In 1962, for example, Malinowski reported that

Fieldworkers also strove to win the favour of women who opposed the MCDP in the belief that such women could be “trouble maker[s] [if] . . . on the wrong side.”66 The ability of women to influence men in implementing MCDP initiatives was not lost on fieldworkers and was apparent in a dispute that emerged at Membertou in 1965. When friction between the elected chief and the man heading up a community improvement project threatened to scuttle the work of the Extension Department, women interjected and held talks with the chief that “resulted in a modest amount of cooperation.”67 Similarly, in 1962, Malinowski noted the success of women in promoting men’s involvement in a “grounds beautification” project: “At first women in the Homemakers’ Club got their husbands interested in the project; and then other men were influenced.”68 Thus, even while the Extension Department’s engagement of women was initially intended to shore up men’s support, it led to women being involved in ways that contravened the MCDP’s own emphasis on female domesticity.

25 Women’s involvement also served as a means of challenging gendered colonial marginalization. Mi’kmaw women, like all Mi’kmaq, had, over the course of centuries, suffered land encroachment, resource depletion, economic deprivation, and social disorientation. And settler impositions and the interfering hand of the federal state after Confederation created particular challenges for Mi’kmaw women. The Indian Act, introduced in 1876, was especially onerous for women who found themselves subject to new legal regimes that treated them as legal dependants of men and formally denied them property and other rights under law. Legislation that stipulated that Indian women who married non-Indian men would lose their Indian status also had the capacity both to divest them of reserve land rights and to alienate them – and their offspring – in a host of ways from their own communities, as a loss of Indian status would prevent women and children from accessing reserve land and IAB services such as schooling.69 Canadian Indian policy was especially adept at muting women’s political voices. While all “Indian” people in Canada were defined as “wards” and denied a meaningful say in the administration of their own affairs by the federal state, the system of band chiefs and councils that was imposed by Ottawa upon Mi’kmaw communities in 1899 formally prevented Mi’kmaw women from voting or running for office in band council elections until 1951, and, in practice, for years thereafter.70 Mi’kmaw women were, therefore, formally prevented from engaging in a political realm that gave Mi’kmaw men input into community affairs, albeit within structures created and overseen by the colonial state.

26 Mi’kmaw women were also particularly hard hit by the rise of industrial capitalism that had negatively affected rural Nova Scotian communities and had helped spark the Antigonish Movement. Mi’kmaw manufactures – barrels, hockey sticks, and other wooden items – were undermined in the early 20th century by factory production of these goods. While both men and women suffered from these shifting tides of production, they presented particular problems for women. Because of a colonial legal framework that aimed to replicate in Indigenous communities middle class patterns of female dependency on male breadwinners, employment opportunities may have been greater for men while Mi’kmaw women bore the brunt of economic dependency.71

27 Viewed in this context, the MCDP’s engagement with Mi’kmaw women afforded them opportunities that challenged the isolating and silencing tendencies of colonialism. Extension Department programs saw Mi’kmaw women of all ages unite around community causes.72 Women enrolled in sewing and cooking classes, gathered in quilt-making groups, participated in home nursing courses, and hosted community social events such as teas and bean dinners. Although these projects linked women through their roles as homemakers, they also gave women opportunities to gather and operate outside domestic spaces in community buildings, such as church halls and other public places. MCDP activities also made women critical players in community improvement projects.73 For example, in 1961 the women of Whycocomagh raised enough money to outfit their church with new locks, interior decorations, floor tiles, and paint.74 This was part of a wider pattern whereby Mi’kmaw women became the financiers of community development initiatives.75

28 The MCDP also eventually encouraged women’s involvement in programs that were not stereotypically feminine in orientation and were not initially opened to women. Men’s low attendance rates meant that women’s participation in Extension Department general meetings – gatherings that emphasized the “masculine” realms of band politics and economic development – came to be specifically encouraged. Given that Mi’kmaw women had been denied the right to participate in federally sanctioned band politics until 1951, such meetings could help familiarize them with political protocols from which they had been barred for many years. The general meetings, which included women only incidentally at first, were eventually dominated by women. For example, in November 1962, a general meeting at Whycocomagh was attended exclusively by “five or six women,” while two days later a general meeting at Nyanza featured “twelve women and girls but only three men.”76 An objective of the general meetings was to “teach” Mi’kmaw communities the procedures of political meetings. Ambiguously described in fieldworker reports as a “step-by-step outline of the basic points in ‘Parliamentary Procedure’,” these lessons presumed Mi’kmaw individuals’ ignorance of Euro-Canadian political protocols and were in keeping with a long colonial agenda of reshaping Mi’kmaw political practices to echo Euro- Canadian norms.77 The MCDP initially aimed these lessons at those Mi’kmaw people (primarily men) who were elected to band councils, but sessions on political protocols continued to be offered at general meetings even as these gatherings came to be dominated by women. Although the novelty of these procedural lessons for women and the extent to which they were receptive to and inclined to use them does not emerge from MCDP records, such lessons were intended to guide women as they gathered to coordinate community projects and programs.

29 In subtle ways, the MCDP also undermined its own rhetoric. Early in its operation, the MCDP emphasized men’s waged employment while it focussed on women’s unpaid work in the home.78 With growing intensity over time, however, the Extension Department focussed on Mi’kmaw women’s wage-earning potential, even if in directions informed by gendered expectations about work. By the mid-1960s, Extension Department staff continued to emphasize women’s homemaking; but staff also established programs to help Mi’kmaw women find paid work. Post- secondary training initiatives, including a series of Red Cross home nursing programs and hairdressing courses, emphasized low-paying “pink collar” work but nevertheless supported women’s wage earning and economic autonomy.79

30 In this same era the MCDP also joined forces with the Nova Scotia folk school movement and encouraged women to become involved in the production of handcrafts, especially baskets made in both traditional and new designs. With this initiative, the MCDP followed in the footsteps of Indian Affairs’ frequent attempts to champion handcrafts as a means of promoting subsistence in communities. These federal undertakings, which were chronically underfunded and ineffective, tended to be viewed by IAB officials as “a panacea suited to women.”80 The MCDP had very high hopes for basketry and other crafts production, and looked to develop a craft industry capable of large-scale production that would supply major retailers such as Simpsons.81 In one proposal, the Extension Department specified that its goal was to have a “fully-autonomous,” Mi’kmaw-controlled handcraft industry that provided “fulltime sources of income.”82 The creators of the MCDP handcraft program do not seem to have envisioned a craft industry conducted by women in their spare time, between their domestic routines. Rather, this was an economic agenda for Mi’kmaw women that contradicted the MCDP’s own focus on female domesticity. Mi’kmaw women’s interest in these opportunities attests to both community needs and their own activism, which stood in opposition to the discourses of domesticity. Given the successes of their projects, women soon became the public faces of the MCDP initiative. Echoing a phenomenon identified by Aroha Harris and Mary Jane McCallum in their study of state-run homemaker programs in Canada and New Zealand, the MCDP and its IAB backers “capitalized on the voluntary labor of Indigenous women, harnessing their influence for the purpose of reform in homes and communities.”83 In this fashion, newspaper stories and photographs featuring Mi’kmaw women’s activities were circulated locally and nationally to promote the successes claimed by the MCDP and to serve as public models for other Indigenous women. For example, a 1964 story featuring several photos of women engaged in the MCDP home nursing program appeared in the New Glasgow Evening News and was nationally circulated via the Winnipeg-based, IAB-published, Indian Record.84 Similar press was afforded a 1970 fashion show consisting of items sewn and knitted by Mi’kmaw women’s clubs at Pictou Landing.85 This sort of public exposure presented Mi’kmaw women in a positive light, challenging the negative stereotypes that marked wider community perceptions of Indigenous women.

31 Mi’kmaw women also had some capacity to shape the direction and scope of the women’s programs. Historian Kathryn Magee’s observation that Native homemakers’ clubs in Alberta “were a vehicle for education, activism and agency” rings true for Mi’kmaw women engaged in programs affiliated with the MCDP.86 In choosing to participate, Mi’kmaw women helped shape MCDP programs. Even when not participating, their actions illustrate the politics of development measures and localized opposition to them. Extension Department records make clear that Mi’kmaw women’s participation in the MCDP was not universal; not all women welcomed Extension Department staff or supported their undertakings. In 1963 fieldworker Audrey MacDougall lamented that women at Barra Head were uninterested in the creation of a homemakers’ club, a rejection of the MCDP’s domestic mandate.87 Other fieldworkers’ reports highlight the opposition of Mi’kmaw women. In one candid account, a fieldworker complained that a Mi’kmaw woman had “little interest in community affairs and seems to feel that no good will come of any project.”88 Another Extension worker wrote about how an allegedly intractable Mi’kmaw woman was said to “believ[e] that any [Extension] worker in the area is a servant and can be treated as one.” The fieldworker went on to outline her fractious relationship with this woman: “On one occasion I was forced to drive away from her screaming figure while she threw insults at the departing car. She would be a good woman to be on the good side of not because she assists, but because she is a trouble maker when one is on the wrong side.”89 Some Mi’kmaw women clearly rejected the presence and work of Extension Department staff in their communities.

32 Mi’kmaw women also took up the lead in MCDP projects, either co-opting programs first established by fieldworkers or by spearheading their own; in both scenarios, Mi’kmaw women abandoned the lead of Extension Department staff. In 1967, a fieldworker reported that the women of Afton had taken over a MCDP project that saw them manufacture and sell wreaths. Said the fieldworker: “I felt no obligation to continue doing the leg work on this project and the interested women took the initiative themselves.”90 In 1966, another group of Mi’kmaw women coordinated a quillwork program that saw 20 women taught the art of quillwork production by a group of Mi’kmaw women from Shubenacadie. The quillwork program, a joint initiative of Mi’kmaw women and the Nova Scotia Department of Education Handicraft Division, was sanctioned by the MCDP but had been initiated by a local Mi’kmaw woman who had “expressed the need” for the program and who had “personally interviewed the director [of the Handicraft Division].”91 Similarly, the basket-making program referred to above was also community-driven and originated with women. Occupying “chief roles” in the basket project, Mi’kmaw women manufactured hundreds of baskets before they sought out the MCDP to assist with the marketing of them.92

33 At other times, fieldworkers’ private aims for projects were undermined by the goals of Mi’kmaw women. In 1962, for example, Malinowski was annoyed when an initial plan to dedicate funds raised by women to the erection of street lights in Nyanza was altered by the community’s women and the monies instead were dedicated to church renovations, a development Malinowski opposed and, for unstated reasons, described as “disheartening.”93 Mi’kmaw women did not universally support Extension Department activities and, in opposing them, Mi’kmaw women were in some ways able to shape the initiatives sponsored by the MCDP.

34 Finally, and significantly, the MCDP became a venue through which Mi’kmaw men and women could voice complaints about the colonial pressures they faced. Early in the program, the MCDP assumed the role of supporting Mi’kmaw critiques of government policy. Extension Department workers did this by acting as liaisons between the Mi’kmaq and federal and provincial state agencies, and by advocating for Mi’kmaw women. Reflecting what historian Linda Gordon has noted about social workers, fieldworkers of the MCDP had the capacity to inject into their work a “flexibility, creativity, and empathy beyond the strictures of agency policy.” Sometimes they became advocates for Mi’kmaw women in a way that their positions did not intend.94 In a 1965 report, fieldworkers noted that they routinely wrote letters to members of Parliament on behalf of Mi’kmaw people and, in the process, bypassed both the Extension Department and the Indian Affairs Branch. They explained that “while we did not encourage this approach we nevertheless found ourselves at the Indians’ request in the capacity of typing their proposals as they sought to tap this political resource.”95 By helping Mi’kmaw individuals access state agencies, the MCDP served to loosen the grip of the Indian Affairs Branch, which had insisted that any communiqués between the Mi’kmaq and other governmental agencies be routed through the local Indian agent. Such support was particularly valuable for Mi’kmaw women who sought the influence of the MCDP to seek restitution on issues related to welfare services. In 1968, for example, fieldworker Effie MacIsaac helped a recently widowed Mi’kmaw woman attain financial support from the Department of Veterans Affairs in connection to her deceased husband, a veteran.96 In 1969 Elizabeth Tower helped one Mi’kmaw family to access a mattress for an ailing child, and another to secure welfare assistance.97

35 Another way in which MCDP fieldworkers undermined colonialism was by hiring Mi’kmaw staff. Employing Mi’kmaw people in MCDP programs contradicted a long-standing colonial aversion to engaging Indigenous people in their own administration.98 Perhaps the MCDP, like the IAB itself, was motivated to involve Indigenous people in programs as a means of deflecting criticisms in an era in which colonial regimes were being challenged.99 Still, by hiring Mi’kmaw men and women, the MCDP offered Mi’kmaw individuals positions that gave to them new outlets for old Mi’kmaw critiques of state policy. The hiring of Noel Doucette and Roy Gould serves as an important example. Both Mi’kmaw men worked for the Extension Department and, in February 1965, with personnel and financial support of Extension Department staff, they revived after a 30-year hiatus the Micmac News, a publication that became an important vehicle of Mi’kmaw rights advocacy.100

36 Significantly, it was not just Mi’kmaw men who offered trenchant critiques of state policy. Sister Kateri of Membertou, whose given name was Dorothy Moore, had a recurrent role in the MCDP. In 1961, and again in 1963, Sister Kateri was hired by the Extension Department to speak to short course participants on “The Education of Children.” Her Roman Catholicism and her endorsement of Euro-Canadian schools for Mi’kmaw children (she herself was a teacher) might have, in some ways, aligned her with the MCDP and the colonial state more generally, but Sister Kateri’s ability to speak the Mi’kmaw language served to affirm the value of her Mi’kmaw culture. The fact that she urged her people to “stand up for their rights” can also be read as a challenge to the very essence of colonialism.101 Although the proposal to hire Sister Kateri as a full-time employee of the Extension Department did not come to pass, she nevertheless had an ongoing interest and presence in women’s MCDP activities. In 1964, for example, Sister Kateri was featured in photographs celebrating the graduation of several women from the Membertou home nursing course.102 The engagement of a Mi’kmaw woman such as Sister Kateri in the MCDP is significant, for this sort of positioning of Mi’kmaw women ran against the story- line of Canadian colonialism that had long marginalized and denigrated Indigenous women. Sister Kateri’s work also no doubt reinforced for other Mi’kmaw women the legitimacy of their own perspectives, and affirmed their capacity to voice them.

37 Thus, the Micmac Community Development Program walked a tenuous line as it both endorsed and challenged federal colonial policies. By the end of the 1960s, its own critiques of federal “Indian” policy had substantially aligned with Mi’kmaw political aspirations in the aftermath of the 1969 White Paper. In 1970 the Mi’kmaq, citing their desire to direct their own affairs, ended their relationship with the MCDP and formed the Union of Nova Scotia Indians, a self-directed organization that assumed the mantle of community development on its own terms. The 13-year run of the MCDP, however, offers a lens through which to view the complicated lives of Mi’kmaw women in northern and northeastern Nova Scotia. By foisting on Mi’kmaw women well-worn middle-class criticisms of Indigenous women’s homemaking, childrearing, and morality, and by facilitating the reach of the Indian Affairs Branch into Mi’kmaw families and their communities, the MCDP continued to subject Mi’kmaw women to assumptions that characterized them as failed women in need of guidance in the domestic realm. Simultaneously, the MCDP provided to Mi’kmaw women new opportunities that, in some ways at least, served to undermine this colonial praxis that had historically isolated and silenced them. Community projects established and overseen by Extension Department workers provided to Mi’kmaw women of all ages a means of connecting with each other, both within and between Mi’kmaw communities across the Maritime region. In addition, positive media coverage of women’s MCDP activities created an alternative public discourse that undermined negative stereotypes of Indigenous women as they celebrated – rather than disparaged – Mi’kmaw women’s contributions to their communities. Finally, the MCDP’s own criticism of colonial assumptions, along with its willingness to offer to Mi’kmaw people, including women, positions of authority within its programs, created a context that legitimized Mi’kmaw women’s resistance to state policy.