Articles

Contested Nationalism:

The “Irish Question” in St. John’s, Newfoundland, and Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1919-1923

From 1919 until 1923, Irish nationalist networks flourished in St. John’s and Halifax. This article is a comparative study of responses to the Irish Question in the two cities, and it suggests that Irish identities did not evolve in isolation. Rather, their intensity and expression were profoundly influenced by the interaction of local, regional, national, and transnational ethnic networks. Although those of Irish descent who participated in the Self-Determination for Ireland League meetings, rallies, and lectures tended to be at least a generation removed from their ancestral homeland, they remained part of a transnational Irish diaspora until well into the 20th century.

De 1919 jusqu’en 1923, les réseaux nationalistes irlandais étaient florissants à St. John’s et à Halifax. Cet article est une étude comparative de réponses à la question irlandaise dans les deux villes et montre que les identités irlandaises n’évoluaient pas en vase clos. Leur intensité et leur expression étaient plutôt profondément marquées par l’interaction entre des réseaux ethniques locaux, régionaux, nationaux et transnationaux. Même si les personnes d’origine irlandaise qui participaient aux assemblées, aux rassemblements et aux conférences de la Self- Determination for Ireland League avaient généralement quitté leur pays ancestral depuis au moins une génération, ils faisaient encore partie d’une diaspora irlandaise transnationale jusque tard dans le 20e siècle.

1 THE SCHOLARLY UNDERSTANDING OF IRISH EXPERIENCES IN CANADA has developed considerably since the 1960s, but significant lacunae remain.1 How those of Irish birth and descent in the space we now call Canada engaged with the political struggles of their ancestral homeland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, for example, has only been examined in a cursory manner, at least until recently. Since the early 1990s, and especially in the last decade, studies of Irish Canadian nationalism have become the most productive area of the field thanks to scholars such as Robert McLaughlin, David Wilson, Mark McGowan, Brian Clarke, William Jenkins, Rosalyn Trigger, Simon Jolivet, and Carolyn Lambert.2 It is work in progress, with much remaining to be done. Most research, particularly the recent monographs by McLaughlin and Jolivet, focuses on responses to Irish nationalism in Ontario, Quebec, and, to a lesser extent, New Brunswick. With the exception of Pádraig Ó Siadhail’s short investigation of the Irish self-determination movement in Halifax and Lambert’s study of St. John’s, the extent to which nationalist networks extended into Nova Scotia and Newfoundland in the 20th century remains understudied.3

2 This article is a comparative study of responses to Irish nationalism in St. John’s, Newfoundland, and Halifax, Nova Scotia, from the end of the First World War to the end of the Irish Civil War in 1923. These were the years of the Anglo-Irish War, 1919-1921, when republican forces led by Eamon de Valera and Michael Collins waged a guerrilla war against British government in Ireland, as well as the Civil War, which in 1922 and 1923 followed the establishment of the Free State. The conflicts were transnational events funded in large part by contributions from the Irish diaspora, notably communities in Great Britain, Canada, Australia, and, especially, the United States. Although the Irish in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland were generally more than one generation removed from the ancestral homeland, nationalist organizations extended into both places and allowed those of Irish descent in St. John’s and Halifax to participate in the diasporic movement for Irish self-government. These political groups, most notably the Self-Determination for Ireland League (SDIL), tended to be of North American origin, diffusing into eastern cities from the west.

3 The relationship between nationalism and ethnicity is complex. The extent to which the members of an ethnic community participated in the political affairs of their ancestral homeland represents just one expression of their broader ethnic and cultural identities. Nevertheless, numerous scholars focus on diasporic nationalism in order to gain a clearer understanding of how old-world networks and connections continued to influence the invention and reinvention of ethnicity in the new. Ethnicity was, and is, complex, variable, and often highly personal. As Kathleen Conzen, Herbert Gans, and others point out, however, in times of political turmoil in the old country, private, romantic, and symbolic ethnic identities can be transformed into widespread public action, linking individuals and communities together through diasporic nationalist networks.4 Such instances provide the historian with an opportunity to study this assertive, public facet of ethnicity.

4 An examination of how those of Irish descent in these two port cities responded to the Irish struggle for self-determination contributes to the expanding historical literature in a number of ways. As we are well into what Irish historians have referred to as the “decade of centenaries” – 2013 to 2023, which the anniversaries of the First World War, the Easter Rising, the Anglo-Irish War, the formation of the Irish Free State, and the Civil War – a comparative study of St. John’s and Halifax can enhance our understanding of diasporic Irish nationalism as well as the depth and persistence of Irish identities more broadly by focusing on communities that were almost exclusively North American-born. Although those of Irish descent who participated in the nationalist networks examined here tended to be at least a generation removed from Ireland, they remained connected to a transnational Irish diaspora until well into the 20th century. Furthermore, this study fits into a growing body of comparative scholarship on Irish ethnicity, particularly works that examine how British or imperial identities interacted and intersected with Irish ones.5

Irish communities on the continental periphery: St. John’s and Halifax

5 From their earliest development, both St. John’s and Halifax maintained close links with Ireland. In St. John’s, the Irish connection emerged via the transatlantic networks of the migratory cod fishery. By the 18th century, English vessels were recruiting young male Irish labourers, primarily in Waterford. Initially, this migration was seasonal. Few overwintered in Newfoundland, and fewer still remained permanently. With the collapse of the migratory cod fishery in the 1790s, however, seasonal migration increasingly became permanent emigration. During the first third of the 19th century some 35,000 Irish passengers were recorded, most arriving in St. John’s.6

6 The vast majority of these migrants came from within 30 miles of the port of Waterford: southwest Wexford, south Kilkenny, southeast Tipperary, southeast Cork, and County Waterford. One of the most significant characteristics of Irish- Newfoundland migration is that “no other province in Canada or state in America drew such an overwhelming proportion of their immigrants from so geographically compact an area in Ireland for so long a time.”7 Direct migration from Ireland trailed off dramatically in the 1830s, and by 1840 had virtually ceased. St. John’s and the rest of Newfoundland were largely unaffected by the vast waves of emigrants fleeing the Irish potato famine in the late 1840s.8

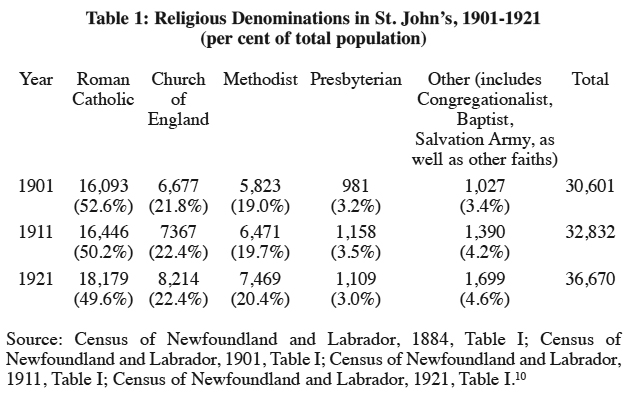

7 In addition to being one of the earliest sustained migrations from Ireland to North America, Irish settlement in Newfoundland was overwhelmingly Catholic. Few Irish Protestants ever settled in the place, and owing to the absence of any other significant influx of Catholic settlers – such as Italians, Poles, French, or even Highland Scots – the formula “Irish equals Catholic” held true for St. John’s perhaps more than any other city on the continent. During the 19th century, St. John’s was primarily Catholic and Irish. In 1836, 77 per cent of the inhabitants of St. John’s were Roman Catholic – almost all of whom were of Irish birth or descent. The high ratio of Catholics to Protestants was maintained through mid-century. The 1845 census recorded a Catholic population of 78 per cent, while by 1857 the proportion had dropped to 73 per cent.9 The percentage of Catholics to Protestants in St. John’s decreased as the century wore on, falling to 62 per cent by the 1880s before exhibiting a much slower decline after 1900 as shown in Table 1.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 18 The gradual drop in the relative size of the Irish Catholic population of St. John’s was almost certainly a result of their propensity to emigrate to Canada and the United States in the late 19th century. Edward Chafe has established that almost 80 per cent of those who left the island in the mid-19th century were Catholics of Irish birth or descent, though unfortunately no reliable data exist for peak decades of emigration or for St. John’s specifically.11

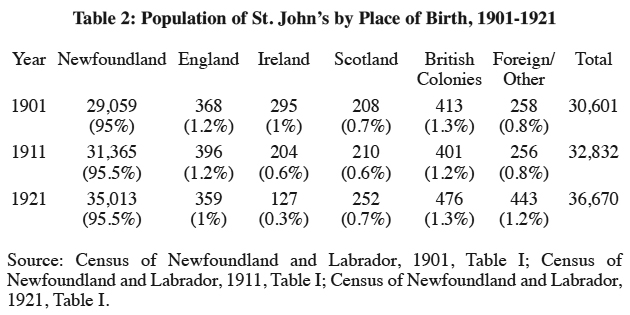

9 Although there were substantial numbers of Catholics of Irish descent in St. John’s by 1900, the proportion of residents born in Ireland was tiny. Because migration from Ireland to Newfoundland largely ceased before the famine, the percentage of Irish-born residents in the town had fallen to just 16 per cent in 1857 and declined to 1 per cent or less in the 20th century as shown by Table 2.

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 2The most salient feature, then, of the population studied here is that it was almost entirely Newfoundland-born. In 1921, only 127 residents of St. John’s had been born in Ireland. Because the Irish Catholics of St. John’s had arrived so early and formed such a high percentage of the population, they were by then well integrated into the colony’s political and economic structures. A substantial Catholic middle class existed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and relations with Anglo Protestant neighbours were harmonious; examples of ethnic or sectarian violence were rare.12 The study of St. John’s, therefore, provides us with an opportunity to examine a socially stratified, multi-generational Irish ethnic community within a British North American context.

10 Halifax’s Irish connections date from its foundation in 1749. An Irish Protestant population, many of whom were connected to the British military, was present in the 1750s. By the late 1760s, there were enough Irish Catholics in Halifax for Terrence Punch to refer to them as the town’s “first minority group.”13 In 1767, out of a population of 3,022, about 470 (15.6 per cent) were Irish Catholics – a significant number, even if a small proportion compared to 18th-century St. John’s. Irish Catholic immigration to Halifax increased substantially in the early 19th century. Some came directly from the Irish southeast, and many more arrived from Newfoundland as part of a “two boat” movement. Newfoundland declined as a source for migrants after 1820, but direct migration from Ireland continued; there was, in addition, a small influx from the Miramichi region of New Brunswick, where Irish Catholics were engaged in agriculture and the timber trade.14 As with St. John’s, immigration from Ireland to Halifax declined considerably during the middle decades of the 19th century.

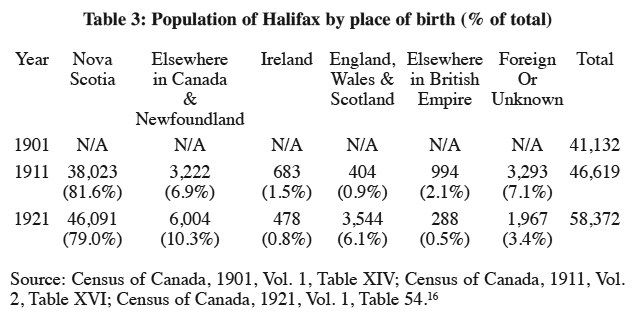

11 By the early 20th century, Catholics of Irish descent were a significant minority in Halifax. In 1901, 10,427 (25.4 per cent) of the population declared themselves as of “Irish” origin in the Canadian census.15 Although there were undoubtedly more Protestants of Irish descent in Halifax than in St. John’s, a majority of Halifax Irish were Catholic. A key difference between the two ports was the ethnic composition of the respective Catholic populations. In Halifax the Irish predominated, but there were also French, German, and Scottish Catholics in the city as well as small numbers of southern and eastern Europeans by the 1920s. In their neighbourhoods, workplaces, schools, and even within the institutions and associations of the Catholic Church, Catholics of Irish descent in Halifax lived amidst greater ethno- religious diversity than their contemporaries in Newfoundland’s capital. As in St. John’s, however, by the 20th century the vast majority of the Halifax Irish were Canadian-born, as shown by Table 3.

12 From 1919 to 1923 we are likewise dealing with a native-born population of Irish descent, primarily Catholic, the overwhelming majority of whom were several generations removed from the old country. In neither St. John’s nor Halifax did the Irish form isolated, economically marginalized immigrant communities. Rather, they were diverse, socially stratified, native-born populations – the majority of whom would have identified primarily as Catholic Newfoundlanders or Canadians. Despite the generational distance from Ireland, however, Irish nationalist associations, particularly the SDIL, flourished in both cities during the early 1920s. A comparative study of responses to Irish nationalism in St. John’s and Halifax clarifies the strength, depth, variety, and persistence of ethnicity in the Irish diaspora, and how a strong affinity for the British Empire was reconciled with an increasingly radical and republican nationalist movement. Owing to the contentious nature of Irish nationalism in the postwar period, moreover, expressions of support for Irish self-government, and particularly the SDIL, were met with more focused opposition than in any previous era.

Display large image of Table 3

Display large image of Table 3The Self-Determination for Ireland League of Canada and Newfoundland in Halifax

13 The 1880s and the 1890s saw considerable engagement with the politics of Ireland by those of Irish descent in Halifax and St. John’s. Fundraising and public rallies supporting the Irish National Land League and, later, Charles Stewart Parnell’s political struggle to achieve Home Rule for Ireland within the British Empire took place in both cities. This enthusiasm for Irish self-government gradually waned following Parnell’s death in 1891, and the 1900s and the 1910s were quiet decades for diasporic Irish nationalism. No branches of the United Irish League, North America’s foremost nationalist association, were established in either city. Even responses to the Easter Rising of 1916 and the subsequent rise of republican nationalism in Ireland were eclipsed by the patriotic participation of both cities’ Irish communities in the First World War.17 The cessation of hostilities in 1918, and the beginning of the Anglo-Irish War in early 1919, established a new context within which those of Irish birth and descent in British North America identified with their ancestral homeland through a direct and active engagement with Irish nationalism. In St. John’s and Halifax, an Irish ethnic reawakening occurred, much as it did in Irish communities throughout North America, as the nationalist struggle evolved into a transnational movement that spanned the diaspora.

14 In both cities renewed interest in the political destiny of Ireland was led in large part by the Self-Determination League for Ireland of Canada and Newfoundland. The organization was formed in Montreal in May 1920. In that city, tension existed between the Friends of Irish Freedom (FOIF), an Irish American nationalist association committed to a fully independent Irish Republic, and the more moderate Irish Canadian National League. The latter publicly refused to support a republic, opting instead for the less-controversial objective of “self-determination” in order to avoid provoking Anglo Canadian opposition and alienating the support of Montreal’s loyal, pro-imperial Irish Catholics. While touring the United States, Eamon de Valera sent Prince Edward Island native Katherine Hughes to Montreal to set up an independent, Canadian, pro-republican organization.18 Hughes, a teacher and journalist, as well as the niece of the former Archbishop of Halifax Cornelius O’Brien, had developed a passionate interest in Irish nationalism during a tour of Ireland in 1914. In 1918 she moved to Washington, where she worked with the Irish Progressive League and, subsequently, the FOIF to lobby for support of Irish self- government. Hughes was an adept organizer. She clearly grasped the significance of expanding the FOIF beyond its bases in New York City and Washington. By establishing local branches throughout the United States, the movement would benefit from a strong, unified, network of Irish American nationalists. To this end, in 1919 Hughes toured the American south, working with local Irish ethnic and benevolent associations, such as the Ancient Order of Hibernians, to establish FOIF branches.19

15 Hughes developed a close working relationship with de Valera following his arrival in America in 1919, and it is not surprising that, owing to her Canadian origins, he chose her to lead the reorganization of the nationalist movement in Canada.20 By mid-May 1920, Hughes had succeeded in uniting the two Montreal groups, and, assisted by former Orangeman Lindsay Crawford, had established the SDIL.21 The new organization was to serve primarily as a propaganda machine. Although Hughes, Crawford, and the other SDIL leaders were republican nationalists, they were keen to avoid controversy. Aware that most Irish Canadians were hesitant to support Ireland’s full separation from the empire, as noted by Pádraig Ó Siadhail, the SDIL adopted the non-committal concept of “self- determination” for Ireland “to recruit as broad a range of support as possible while reducing the risk of suppression by the authorities.”22 Once the league was established in Montreal, Hughes embarked on a cross-Canada tour to expand the organization.23

16 The league was primarily urban. Hughes operated by contacting prominent Irish Canadians in each city she planned to visit. It was they who would find a venue for her lecture and publicize the local meeting. Hughes deliberately sought well-respected public figures to lead local branches – ideally, a “senior, sober and prominent community figure” who could not be easily dismissed as a “hothead or radical.” 24 Although, in the absence of membership lists, it is difficult to analyze the SDIL from the perspective of class, Hughes, Crawford, and the local branch leaders made every effort to portray the league as loyal, middle class, and respectable.

17 Halifax was Hughes’s first stop. Her initial lecture on 2 July 1920 was poorly attended, but following several successful days in Cape Breton she returned to Halifax and gave a talk on 11 July that attracted more than 1,000 people. Despite being sent by a republican leader, Hughes’s Halifax speech adopted a distinctly loyal, pro-imperial tone. She praised the role of the Irish in the First World War, with particular emphasis on Irish Canadians who died fighting for the self-determination of small nations. After some initial hesitations, enthusiasm for the league grew as “the fear of being stigmatized as disloyal and of jeopardizing political, social and economic gains clearly failed to stop sizeable numbers of Irish Catholics from participating in the SDIL.”25

18 The structure of the league was designed to link local Halifax passion for Irish self-government into a regional, national, and transnational movement. A provincial council, including both men and women, was named to coordinate efforts throughout mainland Nova Scotia, while a local council was established to lead activity within the city itself. W.A. Hallisey, a Halifax insurance agent, was appointed to liaise with branches elsewhere in the Maritimes. Many of the city’s wealthiest and most respectable Irish Catholics were involved. The first president of the Halifax branch was Judge Nicholas H. Meagher, while a prominent lawyer and Conservative politician, the Irish-born John Call O’Mullin, was vice-president. Women were likewise active on the executive. Mrs. W. Smith and Ruth Kavanagh were second vice-president and treasurer, respectively. W.P. Burns, who owned his own plumbing company, was elected provincial chairman.26 Although we cannot be sure whether they formed a majority of its members, the middle class Irish Catholics of Halifax were heavily involved in leading the SDIL.

19 Most of the higher Catholic clergy do not appear to have been involved with the organization. Several parish priests, most notably the Irish-born pastor of St. Thomas Aquinas, Fr. Thomas O’Sullivan, were important figures. Archbishop Edward McCarthy appears to have ignored the SDIL almost completely. Indeed, his letters and circulars for the period rarely mention the Irish situation at all. His only formal engagement with the old country was in raising funds to aid women and children in Belfast who had been displaced by the violence in the early months of 1921. McCarthy sent a circular to every parish in the Archdiocese, stating that it was the charitable duty of “every Catholic Canadian throughout the length and breadth of the land” to aid the suffering of women and children of Belfast.27

20 The society’s membership is impossible to reconstruct, but there is evidence to suggest that, in at least some cases, it transcended ethnic boundaries. Herbert Aucoin, a clerk for the Worker’s Compensation Board, was named second vice- president, and at one meeting gave a stirring address on Acadian support in Nova Scotia for Irish self-determination. This type of support was not restricted to Halifax. In Quebec, prominent French Canadian nationalists such as Henri Bourassa were closely involved with the SDIL.28 Nevertheless, it appears that the vast majority of league members and supporters were Catholics of Irish descent.

21 The objectives of the Halifax SDIL were clarified in a letter to the Halifax Herald from chairman Burns on 10 August 1920. The piece reflected a pro-imperial outlook, focusing on the need for principles of British justice and liberty to be applied to Ireland. Burns clearly stated that the Halifax SDIL was neutral regarding whether Ireland should be granted Dominion Home Rule or become a fully independent republic, demanding only a form of self-government that was acceptable to a majority of its population.29 Letters highlighting British atrocities in Ireland, likely penned by the parent branch of the SDIL in Montreal, were published in local newspapers, and lectures featuring Irish American speakers took place through the autumn of 1920.30 The league raised funds by selling Terence MacSwiney calendars for 50 cents each.31 A provincial convention was held at the end of August, before Hallisey, Burns, and Mrs. M. Durand left to represent the branch at a national convention held in Ottawa in October. The organization appears to have grown rapidly, for by the autumn of 1920 it claimed 1,500 members in Halifax alone.32

22 A key role of local SDIL branches was to attract nationalist speakers from elsewhere in North America. The most prominent to visit Halifax was the league’s national president Lindsay Crawford, who arrived in the city in mid-November. A large public meeting was held at which Crawford, Fr. O’Sullivan, and city alderman W.P. Buckley gave lengthy addresses. Crawford made every effort to portray the SDIL as loyal and respectable. He argued that the Irish nationalist struggle was not against the English people, but rather the British government and specifically its mismanagement of Ireland. The meeting concluded with the singing of “God Save Ireland” and “O Canada.”33 Lectures and rallies continued through the winter and spring of 1921, and included a direct appeal from the provincial chairman for Protestant support. He called upon “the Protestant people not to stand indifferent to the cause of Ireland, the sore spot of our Empire. . . . This patriotic work will bring blessings to our own land, and will weld together this Empire more fairly than ever.”34 It is unclear whether Burns hoped to gain Irish Protestant support specifically, or that of Halifax Protestants more generally. In either case, there is no evidence to suggest that he was successful.35

23 In Halifax, SDIL proclamations of loyalty had little effect on how the organization was perceived. Widespread opposition to the league emerged in the city, with the first resolution against it passed by the Orange Order. At a large meeting in September 1920, the Orangemen denounced Halifax’s Catholic associations as disloyal: “[With] organizations such as the Knights of Columbus, the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the SDIL and other organizations of a Roman Catholic character, united as they are to dismember the greatest Empire in the world, surely we in our loyalty to the King and Empire should do all we can to unite Protestant Christians to defend our British and free institutions.”36 The inclusion of the invariably loyal Knights of Columbus, who at no point during this period made any public comment on the situation in Ireland, foreshadowed the anti-nationalist paranoia that would quickly follow.

24 In the wake of the Orange Order’s resolution, Irish nationalists in the city vociferously defended their cause. A letter to the Chronicle, almost certainly written by Fr. O’Sullivan, argued that he had served as a chaplain in the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the Great War in order to help secure the freedom of small nations like Belgium. Agitation for Ireland was no different. In Halifax, he wrote, “The Self-Determination League is avoided because a few flag-flappers raised the cry of disloyalty.”37 By late November, organized opposition to the SDIL extended beyond the Orange Order. A large crowd attended a “mass meeting” to proclaim their support for imperial unity, and to decry the “organization within our midst whose insidious aim is the destruction and disunion of the British Empire” while praising the justice and integrity of the British presence in Ireland. This meeting was organized by the British Empire Alliance, a newly formed group that subsequently led anti-SDIL activity. Members resolved to “no longer allow the slanderous abuse of our wonderful Mother Empire,” while, at another meeting on 10 December, Lindsay Crawford was denounced as disloyal.38 These events drew a response from the local league’s new president, W.A. Hallisey. In a letter to the Herald he challenged “any person to quote one phrase offered by our speakers that can be styled slanderous.” He maintained that the SDIL’s only objective was to promote the right of the Irish people to govern their own affairs, and subtly accused opponents of sectarianism by stating that the league’s members would not have their rights to free speech “curtailed by the machinations of any clique operating under the guise of loyalty.”39 Debates in the press continued, with some comments bordering on outright bigotry. Dr. Charles E. McGlaughlin, an Anglican dentist and Great War veteran, born in Annapolis and secretary of the British Empire Alliance,40 attacked Fr. O’Sullivan’s writing style, noting that his shortcomings were not surprising “coming as he does from that part of Ireland where mongrel language is spoken and his kind are doing their utmost to exterminate the finest and most extensively spoken language in the world.”41

25 Given the intensity of the debate, it is no surprise that those of more moderate opinion wished to emphasize cooperation and conciliation in order to avoid a spike in local sectarian tensions. In this, the Charitable Irish Society (CIS) took the lead. Established in 1786, the CIS had long stood as the city’s foremost Irish ethnic association. Although many of its founders and early members were Irish Protestants, by the mid-19th century it was composed largely of middle class Irish Catholics – and overwhelmingly so after 1900. Nevertheless, members still took pride in its non-denominational status and through its meetings, resolutions, and toasts the CIS married a proud, assertive Irish identity with a devout loyalty to Canada, the monarchy, and the British Empire. On 4 November 1920 CIS members assembled to discuss the escalating situation in Halifax, and passed a resolution that condemned all efforts to portray the Irish Question as an “irreconcilable feud between different religions,” which were likely “to produce incalculable disaster.” Many members of the SDIL were also CIS members, and gave short speeches, including W.P. Burns, Justice J.W. Longley, W.P. Buckley, and J.C. O’Mullin. Colonel Hayes of the British Empire Alliance also spoke at the meeting. Those present emphasized that the society brought together Catholics and Protestants in the spirit of mutual respect and cooperation.42

26 Although it publicly repudiated British reprisals in Ireland, the CIS maintained its pro-imperial outlook throughout this period. The society’s resolutions on Irish affairs display a deep concern with the old country’s political destiny, but also a desire to avoid controversy and any potential suggestion of disloyalty. The minutes refer to the 4 November resolution, noting that the discussions surrounding it were “highly loyal and patriotic in character” and expressing the hope that the British government would “grant Ireland a measure of self-government which would be satisfactory to the Irish people, but would also preserve Ireland as a partner in the Commonwealth of British nations [of] which we in Canada are a part.”43 Unlike the SDIL, the CIS explicitly supported Home Rule nationalism even as such moderate ideology disappeared in Ireland.

27 Other Catholic societies also commented on the situation in the old country. The St. Mary’s Young Men’s Total Abstinence and Benefit Society passed a resolution supporting Irish self-determination. Members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians were also active, organizing a mass meeting of Halifax Hibernians in early October 1920 to declare support for the hunger strike of the nationalist Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney, and for Irish self-determination.44 Both the CIS and the AOH cancelled St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in 1921 to protest the activities of the British forces. On that day, many of Irish descent in the city wore “mourning buttons” consisting of a white shamrock on a black background.45

28 The intensity of the debate surrounding the SDIL died down considerably through the winter of 1921 but it did not disappear altogether, and in April the Halifax District Loyal Orange Lodge passed a resolution against any potential Irish Republic. One month later, the British Empire Alliance held a meeting involving a number of other pro-imperial organizations, including the British Empire League, Loyal True Blue, the St. George’s Royal British Veterans, and the Orange Order. The assembly was called “to oppose the upcoming provincial SDIL convention in Halifax where treasonable utterances would be made.”46 Their opposition was unsuccessful: the convention went ahead at the beginning of June. Regional cooperation was again in evidence, with delegates from New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island joining with Nova Scotians to support Irish self-government.47

29 For most of the Halifax Irish, it is not surprising that the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed in December 1921, was an acceptable solution to the Irish Question. The CIS held a special meeting in February 1922 to celebrate the treaty. The SDIL, meanwhile, proclaimed its support pending the measure’s ratification by the Irish Parliament, the Dáil. W.P. Burns stated simply: “Whatever suits the people of Ireland, suits us.”48 Following the passing of the treaty in Dublin, public commentary on Irish affairs declined dramatically in Halifax. The SDIL faded away, and the CIS no longer passed resolutions on Irish affairs. Even the Civil War evoked little local response in the city, although the violence was covered by the press.

The Self-Determination for Ireland League of Newfoundland

30 Whereas in Halifax the nationalist resurgence occurred after Katherine Hughes’s visit in 1920, engagement with the Irish Question in St. John’s began in the early months of 1919. Having been silent for the duration of the First World War, the city’s oldest and most prominent Irish ethnic association, the Benevolent Irish Society (BIS), again discussed events in the old country. On 17 February a speech to the society by Brother J.B. Ryan, an Irish-born Christian Brother who taught at St. Bonaventure’s College, praised the nationalist spirit that abounded in Ireland.49 The society passed a more formal resolution several weeks later. Mirroring a trend common in Irish American nationalism during and after the war, the BIS called on President Woodrow Wilson to uphold the principles of Irish “self-determination” at the Versailles peace conference, although a vote on the resolution was delayed and it seems that it was never sent to Paris.50 Like the CIS in Halifax, BIS nationalist support was articulated within a loyal, pro-imperial framework. One of the resolution’s central arguments was that Irish self-government would lend strength and unity to the empire.

31 There is some evidence that more radical, republican support for the Irish cause existed in St. John’s, even in the immediate aftermath of the Great War. A branch of the American-oriented FOIF was established as early as 1919. Perhaps owing to its small size, or the controversial nature of its politics, only scattered references to this group have survived. A note in the Evening Telegram of 9 April 1920 reported on a meeting at which 20 new members were admitted, and St. Patrick’s Day greetings from “the central committee for America” were read by the local president.51 One week later, another meeting took place, with a “large attendance”; 17 more applicants were admitted to the “Padraig Pearse Branch, St. John’s Newfoundland,” and a musical celebration was planned for 23 April to celebrate the anniversary of the founding of the Irish Republic in 1916. If this event did take place, it was not reported in local papers. By September 1920, regular monthly meetings of the FOIF were being held at the Total Abstinence Armoury in St. John’s, but unfortunately no details of these meetings have survived nor any evidence of who participated.52

32 Engagement with Ireland continued in other ways through 1919 and early 1920, as lectures and letters to the press became increasingly common. On 8 April 1919, for example, Thomas Kelly, who would become the secretary of the SDIL, gave a lecture on the republican Sinn Féin party to the Star of the Sea Society, a Catholic fishermen’s association.53 As the situation in Ireland escalated, P.J. Kinsella, a regular Telegram correspondent, submitted a piece attacking the British government’s handling of Irish affairs. He concluded by reproducing the full lyrics of the republican anthem, the “Soldier’s Song,” deeming it “no more objectionable than the French Marseillaise.”54 Such responses to Irish affairs do demonstrate an interest in, and engagement with, Ireland amongst some St. John’s Catholics – particularly the members of the BIS – but they were limited, and involved only a tiny percentage of the community. The arrival of Katherine Hughes in October 1920, and the subsequent establishment of the Self-Determination for Ireland League of Newfoundland (SDILN) precipitated the most popular, concentrated engagement with Irish nationalism observed at any point in St. John’s during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

33 Hughes first came to St. John’s in early October 1920, towards the end of her tour. She arrived by train from the west coast of the island, and was met by some of the city’s most prominent Catholics.55 Her first public lecture was given to more than 1,000 people at the Methodist College Hall, Long’s Hill, on 5 October. She immediately emphasized that the question was not a sectarian one, and that both Irish Catholics and British Protestants should support Ireland’s fight for self- determination. The arguments were cautious, as in Halifax, with Hughes focusing on the idea that the freedom of small nations such as Ireland had been a central aspect of the empire’s objectives in the Great War.56

34 The day after Hughes’s initial lecture, the SDILN was organized. Customs Inspector R.T. McGrath served as chair, and it was decided that a provisional committee would govern until elections were held in the new year. The Canadian branch supplied literature that was disseminated locally, and also sent nationalist speakers to the town. J.M. Devine and John T. Meaney, a tailor and the colony’s liquor inspector, respectively, were selected to represent the Newfoundland branch at the national convention in Ottawa, while McGrath was named chairman of the Dominion Council.57 On 19 October the SDILN met to elect its provisional council. Its composition suggests that the movement was led by the middle class, and, as in Halifax, some of the city’s most influential Catholics were involved. Chairman R.T. McGrath was a former politician and the colony’s chief customs inspector, while W.J. Higgins was a prominent lawyer, president of the BIS, and a member of the House of Assembly. St. John’s native Philip F. Moore, who owned and operated his own plumbing business, was a respected member of the BIS dramatic company and also represented Ferryland in the House of Assembly from 1909 to 1928.58

35 The SDILN remained closely connected to its Canadian counterpart. Both Meaney and Devine gave passionate addresses on behalf of Newfoundland at the Ottawa convention. Devine rejoiced that “this Dominion [has] linked hands with Canada in the noble cause for which Irishmen were fighting,” while Meaney’s speech contains some of the most direct evidence that, at least for some St. John’s Catholics, the pro-imperial outlook was beginning to erode when faced with the draconian actions of British forces in Ireland. The liquor controller stated that his only son had been killed fighting for the empire during the Great War, but that now he “would not have permitted [his] son to fight for the British flag, because of what had been perpetrated under its aegis. Ireland never could and never should trust the word of a British statesman.”59 Such strong words from a Catholic Newfoundlander, particularly one who held public office, would have been unthinkable during the war.

36 Lobbying and the dissemination of propaganda remained the primary objectives of the SDILN. Letters were submitted to the local press, beginning in early November 1920, that dealt with various aspects of the Irish Question. All provided nationalist arguments. British mismanagement of Ireland, especially the violent Black and Tan reprisals, were highlighted and impugned, even if letters were always careful to avoid overt support for republicanism. As in Halifax, the concept of self- determination was left intentionally vague so as to evoke as little controversy as possible and to draw support from beyond the Irish Catholic community.60

37 The SDILN also held regular meetings at which the nationalist movement was discussed. Women were prominent at these meetings, frequently giving addresses, singing songs, and reciting poetry alongside their male counterparts.61 The Catholic clergy were notable for their lack of involvement. In the opening decade of the century, it had often been St. John’s Irish-born churchmen who led responses to events in the old country. There does not seem to have been any clerical representation in the SDILN, however, nor did priests give addresses at their rallies – almost certainly due to the organization’s controversial status.

38 One of the most significant public events organized by the league was the visit of the Canadian national president Lindsay Crawford in late November 1920. Crawford spoke to a full house at the city’s Majestic Theatre, with his arguments focusing on how the fight for Irish self-determination was neither “racial nor religious in its origin.” His central objective appears to have been to appeal for “a broader spirit of toleration in the discussion of the Anglo-Irish problem,” nearly identical rhetoric to that being produced by the Halifax SDIL at the same time. The SDILN was actively attempting to gain support from the entire community, arguing that one did not have to be Catholic or of Irish descent to support the cause of Irish self-determination. The meetings finished with a display of loyalty, as the assembly sang both “God Save Ireland” and “God Save the King.”62

39 Despite the best efforts of Crawford and the SDILN executive to gain general support, the movement was met with significant organized opposition. As in Halifax, hostility was led by the Orange Order. The first public pronouncements against the SDILN, however, were made by a Presbyterian minister, Rev. Dr. Jones, during a lecture on the position of Ulster. Jones, one of very few Ulster Protestants in the town, called for the league to be disbanded and accused it of being “admittedly anti-British” and of inciting “sectarian and racial animosity” within the colony. Chairman R.T. McGrath immediately responded to these accusations, emphatically denying the charge of anti-Britishness by arguing that the principles of Irish self-determination were in line with British ideals of justice and had been implicit in the empire’s objectives in the First World War. He also denied that the league was creating sectarian discord within the community, stating that it would “never willingly give rise to any division among the people of Newfoundland” and pointing out that the league welcomed men and women from all sects and that its meetings were public.63

40 Further public denunciations of the SDILN continued over the next month. T.B. Darby, a regular correspondent to the Telegram, argued that the league was aggravating sectarian hostility in the community, and that because of this the affairs of Ireland should be ignored. Jones, in a lecture to the Llewellyn Club in early December, criticized the league regarding the vagueness of the concept of “self- determination.” He argued that the SDILN should overtly support Dominion Home Rule, and rule out any adherence to republicanism, so as to create a support base among St. John’s Protestants. As it stood, all those “who were imperial in their mindset would strongly and openly oppose it.”64 Evidently, there was a widespread belief that the league was a republican organization, and responses to the Irish Question in Newfoundland appeared to be developing a sectarian dimension. Although overt opposition was largely restricted to the Orange Order, few Anglo Protestant Newfoundlanders actively supported the SDILN.

41 Around the same time that Jones gave his speech, the Orange Order, much as in Halifax, was mobilizing against the league. On 1 December a special meeting of the Provincial Grand Lodge was convened to discuss the local situation. Orangemen from St. John’s and the outports attended the meeting, and the roll showed “the largest number registered at a regular meeting of [the] body.” The public resolutions were printed two days later, objecting to what they perceived as disloyal and seditious acts by members of the colony’s legislature and civil service:

The resolutions concluded by calling on the government to dismiss disloyal civil servants and politicians.65 When compared to Halifax, and even more so to other parts of Canada such as Ontario or New Brunswick, the bitter Orange Order opposition to Irish nationalism in St. John’s is particularly interesting. Unlike lodges elsewhere, members of the Orange Order in Newfoundland were almost exclusively Anglicans or Methodists of English descent.66 United by their Protestantism, loyalty to the empire and monarchy, and, undoubtedly, at least some measure of anti- Catholicism, the Orangemen of St. John’s and vicinity did not oppose Irish nationalism because of an ancestral connection to Ulster or Irish Protestantism but rather because of the fraternal connections of the Orange Order. In this instance, the pan-Protestant, imperial, transatlantic networks of Orangeism transcended the ancestral origins of its members and coalesced into a cohesive anti-Irish nationalist movement that spanned British North America.67

42 Arguments for and against the SDILN appeared in the local press throughout the following months. Secretary Thomas Kelly and the league’s press committee continued to publish letters on the Irish situation, but at no point was support for an Irish Republic openly articulated. Other commentators continued to identify the league as disloyal and seditious, and accused it of promoting sectarianism.68 The overtly pro-imperial Archbishop Edward Roche, who had ridiculed the suggestion that Irish republican sympathy existed in Newfoundland during the war,69 wrote to R.T. McGrath regarding Orange Order opposition to the league. He urged the league and its members to be cautious and tactful in responding to the accusations in order to avoid “the throes of a sectarian war.”70 The concern in this letter is evident, and passions regarding the Irish Question were clearly running high.

43 The truce, negotiations, and the Anglo-Irish Treaty were debated at length in the local press and by the BIS, but not by the SDILN. Most commentators expressed their hope that Ireland would remain within the British Empire. The more radically minded J.T. Meaney wrote to the Daily News, expressing his support for de Valera as the Dáil debated the treaty, but noted that he expected it to be passed. Archbishop Roche, who had been following the Irish situation closely, was cautious, and rejected calls for public masses of thanksgiving to welcome Irish peace since so many opposed the treaty and a return to armed conflict was possible.71 The BIS staged a public debate on the measure, in which the pro-treaty arguments were supported by a large majority. Its ratification, and the establishment of the Irish Free State, were widely celebrated.72

44 The SDILN itself made no public pronouncement on the treaty, and was generally quiet after the truce was declared. Its organization remained in place for two years following the ratification, however, and it continued to act as the mechanism through which Irish Newfoundlanders participated in the transnational nationalist movement. Chairman R.T. McGrath selected W.J. Browne, a young St. John’s law student at Oxford, to represent the organization at the 1922 Irish World Race Congress in Paris. Browne, one of the youngest representatives at the congress, was noted for his vigorous defence of open, public proceedings when it came to the Irish economy.73 References to the SDILN gradually disappeared from the St. John’s papers through 1922, and a final meeting was held to formally wind up its affairs in May 1923.74 Although active involvement with the self-determination movement was over, the rise in popular interest in Ireland did not disappear immediately. A successor organization, the Newfoundland Gaelic League, which appears to have had no formal connection to its cultural-nationalist namesake in Ireland, was established in 1922. This group organized lectures on Irish history, politics, and literature; staged St. Patrick’s Day celebrations and Irish music nights; and held Gaelic language classes throughout 1923.75 At the same time, BIS membership increased steadily through the early 1920s.76

45 Although no data exist to indicate the overall size of the SDIL in St. John’s, the passion of the debates surrounding it, and the fact that Orangemen travelled from across Newfoundland to oppose it, suggest that it was far from an isolated movement. Many of the most prominent Catholics of St. John’s were involved, and thousands more participated in the SDILN’s meetings and lectures. More than at any point since the 1880s, thanks to the organizational networks and nationalist literature of the SDILN, the Catholics of St. John’s were aware of being part of a broader diasporic movement for Irish freedom. Not all, probably not even a majority, of those of Irish descent in the city were caught up in this ethnic resurgence; but it was a tangible phenomenon that manifested itself in this and other ways, including a dramatic increase in applications for BIS membership and the success of the Gaelic League in 1923.

Conclusion: ethnicity and identity in the Irish diaspora

46 In the autumn of 1920 and the spring of 1921, many Catholics of Irish descent in St. John’s joined the local branch of the Canadian-based SDIL. The Irish Question was hotly debated in the local press, and the league held meetings and lectures in order to forward the cause of self-government for Ireland. The organization and its objectives were opposed by the Orange Order, the unionism of which was motivated not by ancestral linkage to Irish Protestantism or to Ulster, but rather by British North American and transatlantic networks of Orangeism. A similar series of events took place in Halifax, as Catholics there also participated in the league’s organization while being opposed by the Orange Order and the British Empire Alliance. A comparative investigation of Irish nationalist networks in these two cities leads to a number of conclusions regarding the strength, depth, and persistence of Irish ethnicity in the diaspora. It is significant that even in communities with so few Irish- born residents, Irish nationalist associations such as the SDIL flourished to the extent observed in St. John’s and Halifax. Even more striking is the fact that the sudden surge in interest in the Irish Question came after two decades of relative apathy towards the political destiny of Ireland. This pattern suggests that ethnicity did not decline in a linear fashion, but rather that identification with the ancestral homeland rose and fell depending on circumstances in both old world and new. Of course, the extent to which individuals of Irish descent identified with the old country varied considerably. While many Catholics of Irish descent in St. John’s and Halifax actively participated in SDIL rallies, meetings, and lectures, many more did not.

47 The evolution of the Self-Determination for Ireland movement was not identical in the two cities. In St. John’s, the SDILN continued to operate following the Anglo- Irish Treaty, overseeing Newfoundland’s participation in the Irish Race Convention of 1922, while the Halifax organization disappeared quite quickly. Controversial speeches, such as J.P. Meaney’s, moreover, suggest a more militant or radical stance on the part of the St. John’s branch, though when faced with direct accusations of disloyalty both groups vociferously defended the legality and respectability of their organizations without ever publicly committing to either Home Rule within the empire or republican nationalism. The controversial statements in St. John’s are more likely a product of the individual personalities, rather than a broader tendency towards republicanism in Newfoundland.

48 The role of external organizations in motivating this ethnic resurgence is revealing. Although local Irish ethnic associations such as the BIS and the CIS, and also the well-established Ancient Order of Hibernians in Halifax, had led local engagement with the politics of Ireland, in the cases examined here the organizational impetus for widespread, popular interest in the Irish Question came almost exclusively from outside these cities. Although public discussions of Irish nationalism did take place in St. John’s prior to mid-1920, it was only with the visits of Katherine Hughes that the political destiny of Ireland became a major, public issue of contention in St. John’s and Halifax. In the first two decades of the 20th century this was largely private, expressed publicly only on ethnic feast days such as St. Patrick’s Day. The organizational structures of the SDIL were the key factors in transforming this symbolic ethnicity into a widespread, active engagement with diasporic nationalism. Spatially, these networks were oriented to the west. The organizational impetus, the nationalist speakers, and nationalist literature diffused from the centres in central Canada to these north Atlantic port cities. The ethnic connection to Ireland was, therefore, reinvented within a thoroughly British North American context, as opposed to direct transatlantic connections to the old country, and we can clearly see not only how ethnicity evolved over time, but also how it diffused from place to place.

49 Responses to Irish nationalism in St. John’s and Halifax demonstrate how those in British North America reconciled their Irish identities with British imperial identities at a time when the struggle for Irish independence was becoming increasingly radical and republican. With the fascinating but little-known exception of the FOIF branch in St. John’s in 1919 and early 1920, virtually all public expressions of support for the cause of Ireland were made within the context of staunch loyalty to the British Empire. Catholics of Irish descent in Halifax and St. John’s had lived happily within this imperial context for generations, and it seems that most struggled to conceive of an Irish state existing beyond the boundaries of the empire. Undoubtedly, there were some ardent, republican nationalists present in both communities; but in order to appeal to the majority of those of Irish descent, nationalist rhetoric was explicitly framed within a loyal, pro-imperial context. This differentiates the nationalist movement in British North America from the more radical support that predominated amongst the Irish in the United States during this era.

50 Overall, the SDIL movement, led by men and women several generations removed from their ancestral homeland, shows how a latent ethnic consciousness could be transformed into discernible political action. The rise of Irish nationalism and identity in the public discourse of St. John’s and Halifax was neither universal nor permanent, but it shows how Irish ethnic networks transcended space and how North American Irish nationalism extended as far as the northeastern extreme of the continent. Irish ethnic identities were complex, and they did not evolve in isolation. They were not necessarily passed from one generation to the next in a linear fashion, but, rather, were constructed, invented, and reinvented over time and space by a myriad of both domestic and external forces. In this way they became a part of the transnational movement for Ireland’s freedom that connected Catholics of Irish descent in St. John’s and Halifax into a broader, interconnected diaspora during the early 20th century.