Articles

The Moving Image on the North Atlantic, 1930-1950:

The Case of the Grenfell Mission

Cet article établit les liens entre des images animées et la documentation de changements anthropiques et environnementaux à partir du cas de la mission de Grenfell, à Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador. Les films d’archives inédits de la mission de Grenfell, qui font partie de la collection du Labrador Institute, constituent un univers médiatique remarquable qui élargit notre façon de concevoir l’historiographie environnementale comme une pratique qui incorpore la « spécificité des médias » dans ses modes de fonctionnement et d’argumentation. Cette approche exige que l’on examine non seulement comment les images de l’environnement ont été produites, diffusées et reçues au fil du temps, mais aussi comment ces environnements ont été produits en tant qu’entités à part entière spécifiques au médium.

This article maps the relationship between moving images and the documentation of human and environmental changes through the case of the Grenfell Mission of Newfoundland and Labrador. The Labrador Institute’s collection of never-released film footage of the Grenfell Mission constitutes a distinct media environment that opens up ways of thinking about environmental historiography as a practice that incorporates “media-specificity” into its modes of operation and argumentation. This approach asks us to examine not only how images of the environment have been produced, circulated, and received over the course of time, but also how these environments were produced as distinct, medium-specific entities in their own right.

1 DR. WILFRED GRENFELL BEGAN TRAVELLING to the outports along the coasts of northern Newfoundland and Labrador in 1892 aboard the medical ship Albert sent by the Royal National Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen of London. In the popular North Atlantic imagination, Grenfell is an ambiguous figure: doctor, pseudo-saint, author, fundraiser, and missionary. In recent literature, Grenfell is presented as a social reformer who, for better and for worse, “intervened to change the patterns of living” in northern Newfoundland and Labrador.1 The mission he worked to establish, culminating in the incorporation of the International Grenfell Association (IGA) in 1914, was an organization that eventually oversaw the construction and work of hospitals, nursing stations, schools, orphanages, cooperative stores, and light industries. It became a vast northern health network that was transferred to the provincial government only in 1981. Known as Grenfell Regional Health Services, it merged with Health Labrador Corporation in 2005 to create the Labrador-Grenfell Regional Health Authority.

2 In the province of Newfoundland and Labrador today, Grenfell’s legacy is a complex combination of the material and the immaterial. Many of the buildings the mission built are still standing, the surface of the roads they traced paved smooth, and the localization of medical care in northern coastal communities throughout Newfoundland and Labrador is an ongoing reminder of where the mission had been. On the immaterial side of the ledger, there is a certain ideology of self-reliance, confidence, and mutual aid and co-operation in the staying power of communities whose ancestors have lived through worse. While incorporated as the International Grenfell Assocation in 1914, the “Mission,” as it is still referred to locally, was a vast, international network of volunteer labour. Women and men, as nurses, doctors, nutritionists, care givers, teachers, craft instructors, carpenters, and brick layers from across Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia, as well as other countries, came through St. Anthony, the mission’s headquarters on the Great Northern Peninsula, as they moved on to various nursing stations and hospitals along the coast of Labrador. Whether civic-minded or driven by a missionary concern and sense of action, this vast and multinational group of volunteers were “serving” differing ideals of religious and secular obligation and ultimately cohered into “a sort of Peace Corps.”2

3 The Labrador Institute, a research centre located in the town of Happy Valley- Goose Bay, holds a collection of never-released film footage belonging to the IGA. Consisting of six distinct reels, the films amount to roughly two hours and thirty minutes of silent footage of northern Newfoundland and Labrador and the various mission works (buildings, ships, roads, etc.) as well as practices (plays, dog sled races, pageants, etc.) undertaken from the 1930s to the 1950s. As such, they offer a comprehensive if non-teleological and non-narrative portrait of missionary medical cruises along the coast of Labrador, the arrival of the seasonal steamer in St. Anthony, and footage of mission orphans at play (running races, putting on pageants, etc.) that exemplify Grenfell’s good works in this part of the British colonial world. Overall, the footage is one of those difficult-to-place documentary artifacts that historians often come across: neither fully sanctioned by the institution that created it, yet part of its archival record. In other words, it is a body of evidence with an inchoate historicity that is nonetheless an image-based portrait of a particular environment undergoing multiple forms of human-induced and environmental change.

4 This article seeks to map the relationship between moving images and the documentation of human and environmental changes on two interrelated levels. The first examines the relationship as a potential historiographical practice. That is, it mines the emergent relationship between historical and theoretical media scholarship and environmental history. This approach, in part, assumes that we can draw distinctions among diverse forms of inquiry for the purposes of comparison and mutual engagement. It also, in turn, raises the question as to why it is important to examine what media studies can contribute to and learn from environmental history, and vice versa. In what follows, I propose that we think about such representations of environmental change as media environments that offer their own forms of artifactual legibility that can deepen our understanding of how such emergent sites of media historical scholarship come into being. The second level of analysis extends this characterization of the Grenfell Mission footage as a distinct media environment in order to devise ways of thinking about environmental historiography as a practice that incorporates what could be thought of as “media- specificity” into its modes of operation and argumentation. As such, over the course of the article I will explore how and why media environments cohere. The footage’s status as moving imagery of conveyable events (since they were partly intended to communicate the mission’s work to its international network of donors and potential donors) make of it a media environment that could open up past environments captured by various recording media to the analytical purview of environmental and other historians. This approach asks us to examine not only how images of the environment have been produced, circulated, and received over the course of time, but also how these environments were produced as distinct, medium-specific entities in their own right. The Grenfell Mission’s century-long presence in northern Newfoundland and Labrador introduced forms of change that were at once medical, social, and cultural, but that were above all else environmental in that they fundamentally altered the set of relationships between humans and their surrounding North Atlantic environment. The mission’s found footage that I consider here allows us to track these environmental changes, as well as to examine how the Grenfell Mission actively “made” northern Newfoundland and Labrador into a communicable missionary media environment through its use of film as a documentary medium. While the mission’s media environments may only be tangible in the digital byte or film stock, they are nonetheless real and available for environmental historical analysis.

Environmental historiography

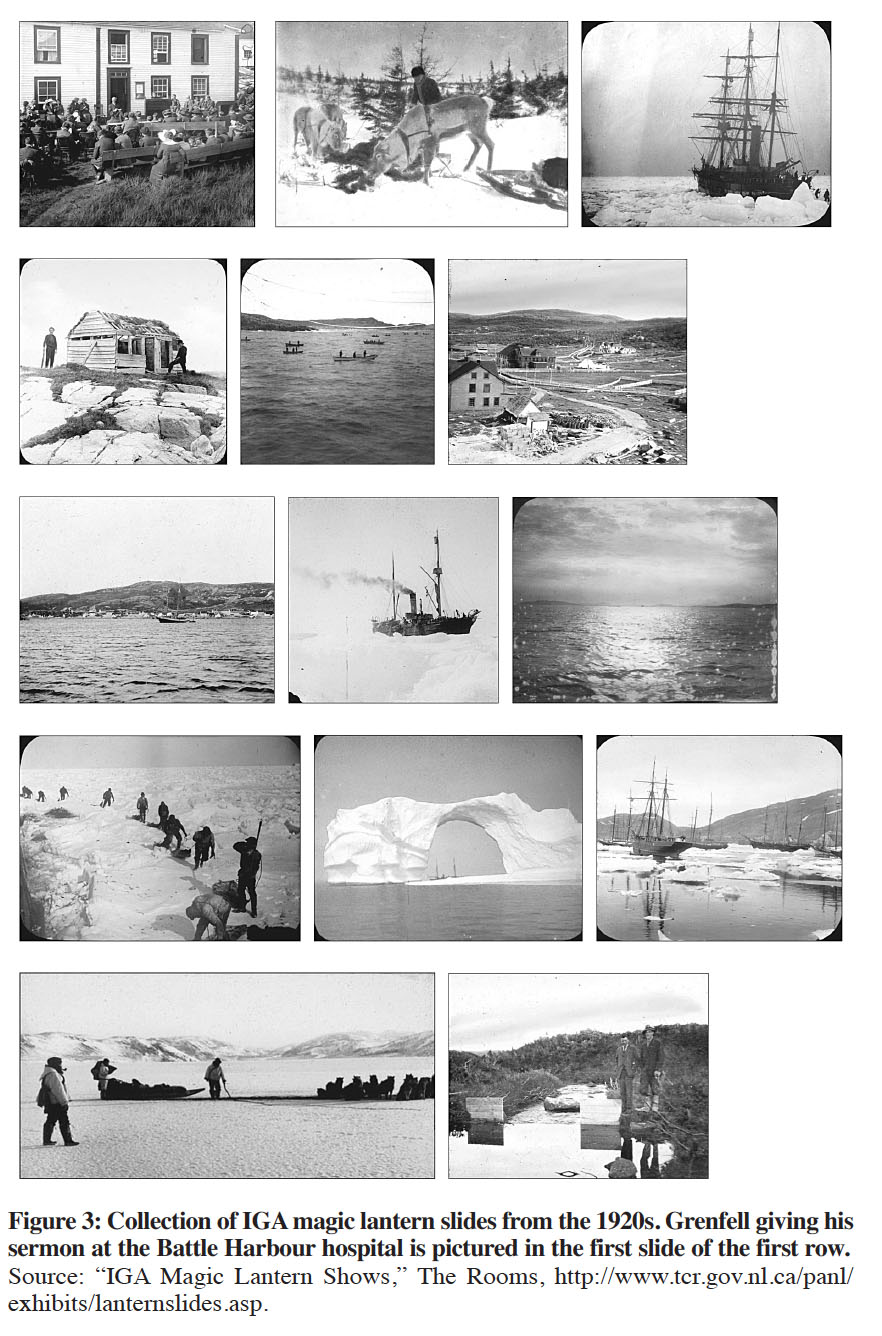

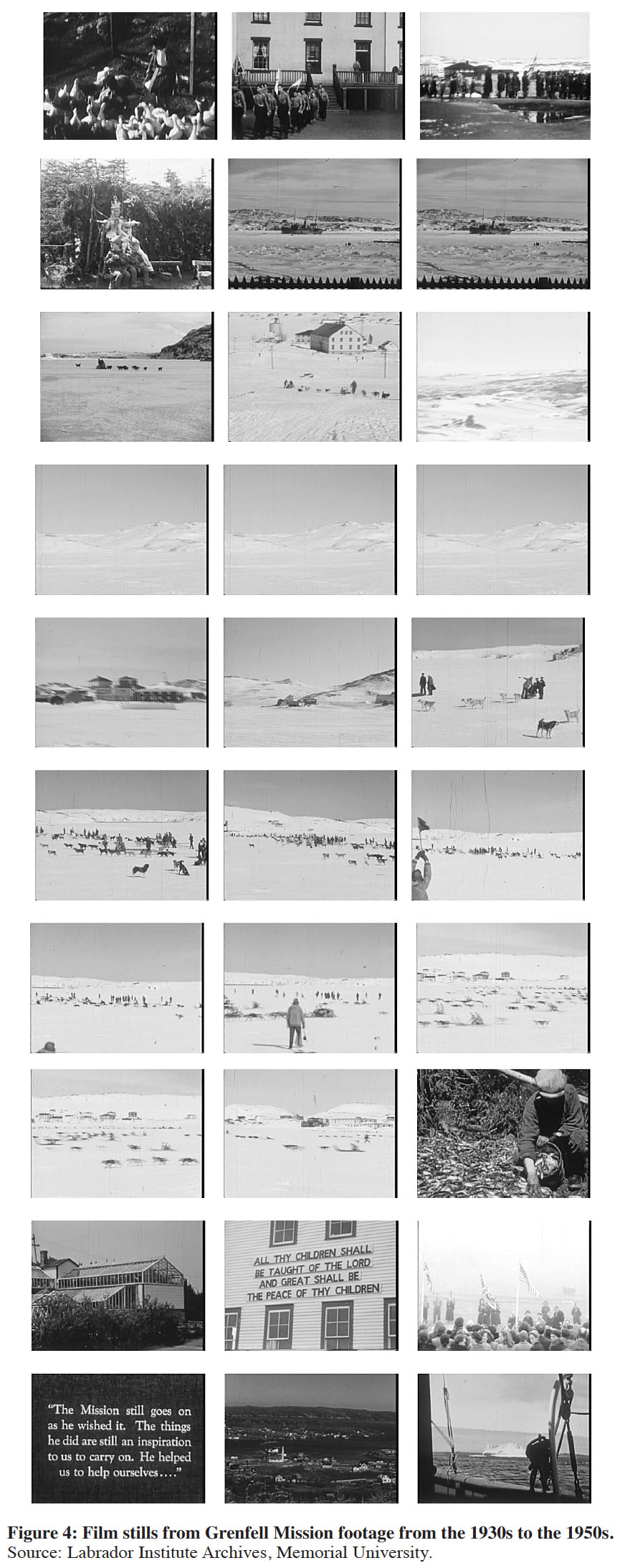

5 The Labrador Institute footage is difficult to discern as a whole. Its current neatness as digitized files belies its messy past as distinct reels of film stock. Moreover, having undergone the tidying process of becoming part of the archival record with the donation of the International Grenfell Association fonds to the The Rooms Provincial Archives (The Rooms), it has been set off into categories of metadata that relate its approximate date of production (ranging from the 1930s to the 1950s), its authorship and ownership (the IGA), and its precise forms of materiality as mainly 16mm film stock. Two sequences can be viewed on the Acadiensis website (www.acadiensis.ca). On one level, taken within the context of the Grenfell Mission’s own media history, the footage represents the evolution of the mission’s work of self-representation. Over the course of the mission’s nearly 100-year history, it mobilized the chronological, sequential, and imagistic media of magic lantern slides, photography, and eventually film to construct documentary evidence of both the conditions of “need” prevailing on the coasts and its own pragmatic and constructive responses to it. The images taken, reproduced, and disseminated by the mission through various channels of print publication and fund-raising lecture tours from the 1890s to the post-Second World War period, represent precise instances, in both a past real time and space, of philanthropic actions it undertook: a 16mm film of orphans at play adjacent to the newly built orphanage (Figure 1); a photograph in the mission magazine, Among the Deep Sea Fishers, of a group of local Girl Guides on parade to mark the mission’s recently completed hospital in St. Anthony in 1927 (Figure 2); or a magic lantern slide of Grenfell giving a Sunday sermon at the door to the Battle Harbour hospital (Figure 3).

6 Visual materials have held a fundamental place in environmental history from its inception. Maps, photographs, films, and other media have, it could be argued, constituted the common ground mediating scholars’ understanding of past environments. In recent scholarship, these have moved to the foreground. Finis Dunaway, Gregg Mitman, and others have characterized this as a “cultural turn” in environmental history.3 Moreover, visuality, as a condition of scholarly production, continues to play an integral role in the work done by many environmental historians, even though it is largely, though not exclusively, confined to an illustrative function. This raises the suggestive question, that I will only address tangentially and partially in what follows, of how to integrate the practices of environmental historians into the broader project of the visual culture of the human-nature interface within media studies.

7 Both fields – environmental history and media studies – are relatively young. They took institutional shape in the 1960s and 1970s within broader and more established disciplinary formations such as periodized and regionally situated forms of historical scholarship, as well as, for media studies, on the margins of departments concerned with rhetoric, public communication, and other comparable forms of media-derived knowledge production. They also share a number of commonalities: expanded understandings of agency that do not necessarily privilege human actors; taking “ecologies” as both modes of analysis and subjects of study; a gradual acknowledgment of the importance of “relations” over “objects” – that is, how environmental phenomena are part of a holistic system whose parts are constantly evolving and interrelating; and the study of interactions between human-made technical systems and their broad environmental, political, cultural, and economic contexts of production and reception. I would argue that environmental history is, in many ways, already media history in the sense that to know how and why environments change we have to understand the complex human and non-human mediations to which they have been subject. This contention is partly predicated on taking an expansive view of “media” and communication, akin to that first espoused by the political economist and communications theorist Harold Innis. While much media scholarship, from the 1950s up until today, confines “media” to the domain of technical devices – or systems that facilitate the communication of information between human and non-human agents – recent reassessments, coming over the last decade or so, of Innis’s work from the late 1930s to the early 1950s have built upon his ambition to broaden our commonplace and acceptable definitions of immaterial and material “media.” For Innis, as Jody Berland notes, material processes “structure and normalize the ratios of reason and emotion, technique and memory, power and location, space and time,” and within that framework “communication technologies mediate the social relations of a particular society by setting the limits and boundaries within which power and knowledge operate.”4 Innis made apparent the importance of devising responsive and more incisive ways of critiquing the mediations that are at stake under the guise of “connective” communication technologies. For Innis, space mattered.5 Berland foregrounds precisely how Innis’s “material processes” get at questions of ideology, state-sanctioning, and class inequalities, amongst others, through a historical-analytical engagement with “rivers, railways, radios, and rationalizations.”6

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 38 When it comes to thinking through the significance of visual materials, many environmental historical approaches tend to focus on the representational content of the artifacts under examination rather than the properties of the media themselves. What the field at large seems to lack is both a comprehensive approach to the conventional media (such as photographs, archival records, or old newspapers) that constitute its objects of research and its means of dissemination and preservation, and also a set of analytical-interpretive lenses through which to apprehend its own field-specific sense of mediation.

9 This in turn raises the question of how to examine the variable agencies at work in the actual production of environmental historical scholarship. The “human” and the “environment” are often the two prime agents of historicity though, as Linda Nash notes, recently environmental historians have been ascribing a greater degree of autonomy and agency to the environment. And yet, as Nash also acknowledges, exactly what this means in terms of historical writing and understanding is not always clear. Nash believes that environmental historians are ideally placed to enact a form of scholarship that “contribute[s] to this rethinking and rewriting of agency because we study the interactions of humans and the non-human world in such detail.” For Nash, the task for environmental historians is to foreground agency in their historiographical practices. And this has important stakes. By questioning both human and environmental agency, we avoid teleological readings of the human- ecology interface. In other words, this approach destabilizes one-dimensional narratives that focus on human reason and technical expertise. In folding agency into a single dispersed and expanded heuristic entity, historiographical practices also have to respond to the media through which that entity is apprehended. “Perhaps our narratives should emphasize that human intentions do not emerge in a vacuum,” Nash writes, “that ideas cannot be clearly distinguished from actions, that so-called agency cannot be separated from the environments in which that agency emerges.”7 If the relation between humans and environments is one of co-emergence and co- shaping, then it follows that environmental historical scholarship is always already reliant on mediation as a critical practice. In order to devise more responsive “narratives” that can really address Nash’s problematic, it also follows that focusing on the broad processes of mediation (of which historians are an integral part) could yield environmental historical narratives that actually describe the relation between “humans” and “environments” as evolving and ongoing. This approach could start to inform what could be thought of as a form of environmental historiography. By examining how we privilege the very media through which we apprehend past environments, we can start to think about how new patterns of agency can emerge from such artifacts as the Grenfell Mission footage.

Media environments

10 This focus on emergence, mediation, and the documentation of change points to the artifactuality of this Grenfell Mission footage. What does the body of film actually comprise? With basic metadata, it is possible to connect the footage to a general geographic location and time period; but the moving images themselves are elusive. In the absence of sound or aural narration, they act as documenters of locations to which they bear witness. For instance, in one sequence (Figure 4), the camera pans over a group of children playing with a flock of geese. This is followed by a cut, and several shots of a group of scouts parading in front of the Mission’s St. Anthony hospital. Another cut brings us a brief glimpse of a pageant put on by a small group of children that is followed in turn by a long shot, held for a few seconds, of a steamer caught in the ice in St. Anthony’s Harbour. The sequence goes on to capture, in an extreme wide shot, a dog sled race, with team after team moving across the frozen bay. While intertitles betray some editing, its overall composition shows how the mission sought a broad sense of documentation when it came to showing its diverse forms of influence in the region. The footage also shows the extent to which the Grenfell Mission served as a mediating organization, seeking to disseminate an image-driven visual culture of both need and reform. In the mission’s dissemination practices moving images could become one circulating medium among others, an imagistic node in a media infrastructure destined to bolster the IGA’s bases of support across North America and Europe as well as to document the mission’s wide range of evolving activities across communities in northern Newfoundland and Labrador.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 411 Although the collection of footage under examination here is largely unedited and out of sequence, the mission did produce institutionally sanctioned and finished films. An article in the July 1928 edition of Among the Deep Sea Fishers states that “at last talking-moving pictures have been made of Sir Wilfred and the work of the Grenfell Mission.”8 This film, assembled from nearly seven miles of footage, was largely shot by Varick Frissell and Herbert Threlkeld-Edwards, with the participation of the Bristol Company of Waterbury, Connecticut – an early studio specializing in the production of “talking movies.” While Threlkeld-Edwards was a mission volunteer keen to use his newly acquired DeVry machine,9 Frissell was an aspiring director and documentarian. Beginning in the 1920s, Frissell, a recent Yale graduate, volunteered with the Grenfell Mission. Over the next decade he made several documentary films on Labrador, such as The Lure of Labrador (1928) and The Great Arctic Seal Hunt (1928), which were both inspired by the work of Robert Flaherty – an influential American filmmaker and director of Nanook of the North (1922).10 The film was the mission’s first foray into the world of moving pictures and came at the significant cost of $3,000, which was mostly spent on the preparation of the disparate footage into a series of vignette-like films by the Bristol Company. It was also, in the IGA’s view, of the most value because it made up a permanent “living and imperishable record of Labrador’s greatest personality.” Film also constituted a kind of “mechanical speaker” that shifted the burden of public speaking away from Grenfell while generating rental income from school, church, and university audiences to whom the topic of the mission appealed. The medium of film became, for the IGA, the best means of creating a lasting “historical record” of the mission’s activities.11

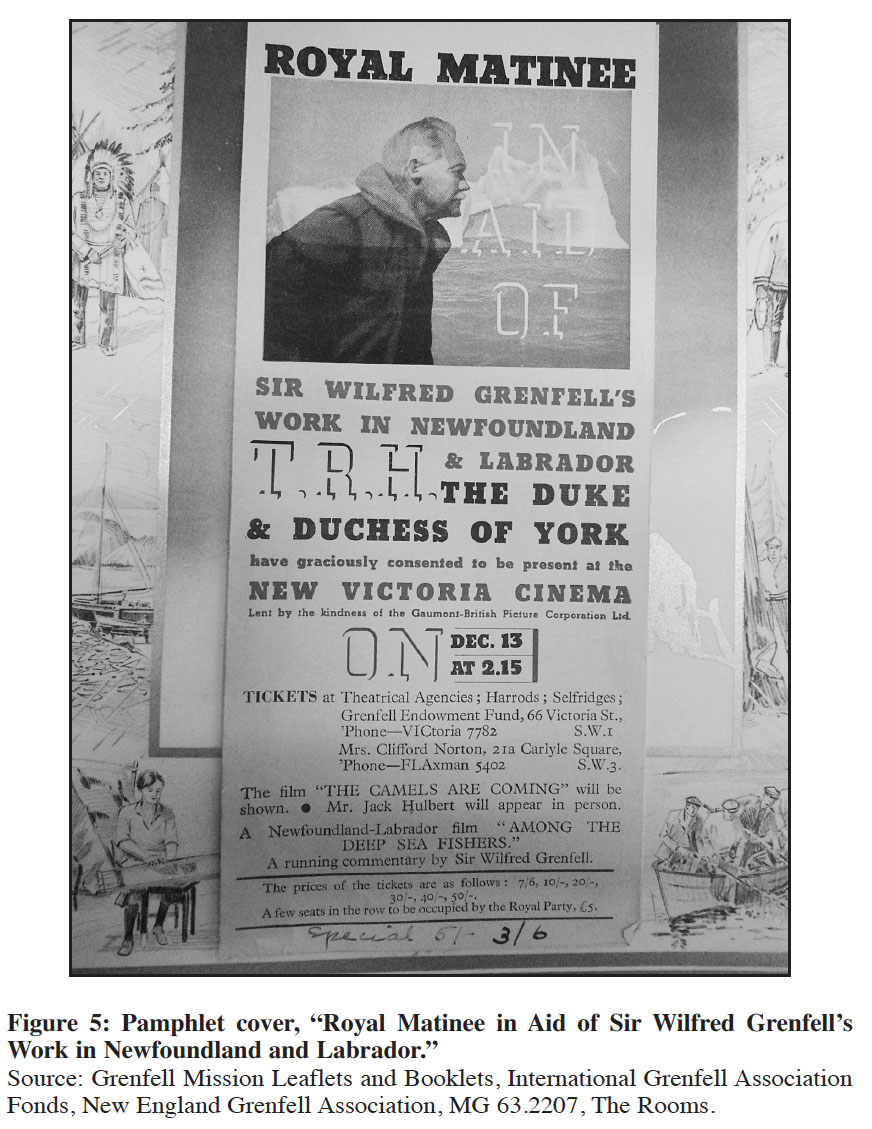

12 In this sense, film (both finished and not) figured prominently both as a generator of symbolic content and as a more generic referent in itself of a mission visuality that secured funding, support, and volunteer labour as an advertising pamphlet (Figure 6) from a December 1934 screening attests. Because of its success, other mission film projects cropped up over the course of the 1930s and 1940s. Frissell partnered with his mentor, Flaherty, to create The Labrador Film Company, based in New York. The production company, with the blessing of the Grenfell Mission, proposed to tell the story of a young doctor and nurse at one of the mission stations “based upon certain authentic and dramatic episodes taken from the history of Grenfell activities on the Labrador.”12 While the motion picture venture was a commercial endeavour that ultimately did not come to fruition, Frissell and Flaherty planned on donating 35 per cent of the film’s net profits to the mission while also making the claim that the “cinema medium” would broadcast the mission’s work to audiences around the world and thus generate interest in Grenfell’s philanthropic projects of reform.13

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 513 Yet, as moving images, and silent ones at that, rather than edited, polished, and institutionally sanctioned films, the Labrador Institute footage that was generated by these mission film projects maintains an interesting status as a historiographical artifact. To view the footage is to participate in its ability to provide us with an evolving portrait of the points of interaction between the environment of northern Newfoundland and Labrador and the ways in which it was made subject to the processes of material change introduced by the mission over the course of two decades. As the events the footage pictures unfold – whether the arrival of a steamer in St. Anthony or the contemplation of the mission’s physical plant – they tell a visual story grounded in the IGA’s varied times and places of missionary influence. As Peter Geller notes, the production of northern imagery, both in Canada and elsewhere, has historically served particular institutional interests – from state and corporate actors to missionary organizations. This production was undertaken, as the largely anonymous authorship of the Grenfell Mission footage attests, by “‘amateur’ image-makers” seeking to document and disseminate a particular form of “northern knowledge.”14 Yet because these are moving images of northern Newfoundland and Labrador that document the mission’s environmental incursions from the 1930s to the 1950s, they are also historiographical artifacts that entail and create their own forms of analytical legibility that can transcend the illustrative function of the image to which so much environmental historical scholarship has been limited.

14 This reading of the footage as moving towards a past environment situated in the filmic artifact itself stems, in part, from recent developments in the field that are invested in the semantic and discursive possibilities of the “visual” as a category that includes not only films but also “spatial imagery” of all kinds, from aerial reconnaissance photographs to 3-D modelling softwares.15 To take the “visual” as equivalent to the “discursive” is not a rejection of the narrative frame that is, as William Cronon suggests, a common mode of human understanding that makes sense of the process of environmental change.16 Rather, it is an attempt to foreground how such forms of documentary footage can take the medium-specificity of film into the scholarly practice of environmental history. As Finis Dunaway notes, following Katherine Martinez and Louis Masur,17 historians can build new relationships with the past by approaching images as something other than illustrations, and thereby start to examine how visual materials give rise to historical events, conditions, and environments.18 While this is a mode of scholarly production that has acquired its own forms of disciplinarity – notably in visual culture studies – the grounding of the analytical possibilities and problematics of visuality as a form of historiography is still a productively emergent tenet within the disciplinary formation of history, and even more so within environmental history proper.19

15 Such an approach to documentary footage brings together medium-specificity – in this case, film – and environmental approaches to the past that take non- anthropomorphic narratives and agencies into consideration. As the film scholar Laura Mulvey notes, this approach demands a recognition of “cinema[’s] . . . privileged relation to time, preserving the moment at which the image is registered, inscribing an unprecedented reality into its representation of the past.” Here, film’s indexical quality registers and inscribes a moment of the past that “fixes a real image of reality across time.” This conception of duration, of bringing filmically real images of past realities into the present, gives film, and unedited footage in particular, a documentary valence. These images become interpretable facts that, as Mulvey points out, “[bear] witness to the elusive nature of reality and its representations.”20 To be sure, this reading could be taken to an extreme. For instance, could we not also read the footage as a quite literal inscription of northern Newfoundland and Labrador’s light conditions from the 1930s and 1950s on the filmstrip’s emulsion?21 This is a tempting, new materialist argument to make, yet it misses the footage’s status as a visual, non-narrative artifact. It also neglects its status as a form of historiographical medium that delivers its own non- anthropomorphic media environment made up of an assemblage of film stock, light conditions, camera types, etc., as well as pack ice, windswept coastlines, and rolling Subarctic landscapes that coalesce to embody a past environmental reality.

16 It is important to recall that media are what allow us to come to know our chosen objects of inquiry. In media studies, looking back at the historical record as a domain of research in and of itself has mostly been the purview of a diverse group of scholars that, in analytical-theoretical shorthand, constitute an entity known as “German media theory.”22 While adherents to German media theory share many approaches and assumptions, two of the most wide ranging are, first, that media should be understood primarily as encompassing technical systems with their own internal logics, and, second, that the “historical record is itself a media artifact.” In relation to the work undertaken by environmental historians, this points to the interface between the processes of environmental change, documentation, and the “recording” done in a broad sense by various inscriptive media technologies on which we, as historians, rely. “Memory, stone, papyrus, paper, and electricity,” as media historian John Durham Peters writes, “each yields a distinct kind of historical record.”23 In this sense, in order to come to know the sorts of histories we are writing we have to come to know better the media that we are deploying to both record and write them. “Spatial imagery,” in this reading, can create its own internal logics of exposition and understanding. As German media theorist Friedrich Kittler has put it, “Media determine our situation.”24 Media can consequently also determine the epistemological boundaries of the historical project as such.

17 To return to the mission footage, the two sequences referenced above offer starkly contrasting environments. In the second, the camera looks out over a town on a bay, with the slow arrival of a steamer in the background. We see various, almost static shots of what look like newly built buildings that serve an institutional purpose of one kind or another. Green, shorn hills, in strong sunlight, make up the backdrop of the scenes, and the topography suggests a glacial past. In the first, in black and white, we follow the arrival and departure of a ship and its journey through dense pack ice, which is examined both clumsily and closely and ending up on a dock where what look like patients disembark and make their way with white- clad doctors to what we take to be a hospital. The tentative, extra-narrative descriptors that I am using belie my own knowledge of the mission and its activities. But what are we actually seeing? In a first instance, I would claim that these are distinct media environments that re-present, through moving images, a North Atlantic, both human and non-human, world in motion. As most environmental historians now recognize, nature is not simply “out there” either in the present or the past. Here, the North Atlantic environment as such, read through the medium- specificity of film, becomes a media environment in itself that, when reinserted into the Grenfell Mission story, tells of the multiple and conflicting media underpinning its production and dissemination. As moving images of a North Atlantic past and, in this case, scarce documents in the work of recasting the co-constructed environments of historiographical practice, here northern Newfoundland and Labrador emerges as a set of distinctly filmic spaces that are newly open to analytical interpretation and optical experience. As the anthropologist Anna Tsing might put it, taking media environments into account could turn historiography itself into a “slow disturbance landscape”25 that can reveal how our knowledge practices come up against a set of given conceptual tools that can be changed. To give film footage a new historiographic agency is to recognize that the past endures across, in, and as media with varying documentary valences. It is also an open-ended invitation for environmental historians to revisit media environments of the past, filmic and otherwise, as substantive markers of non-anthropomorphic environmental change.