Forum

Alex Colville’s Trajectory as a Muralist

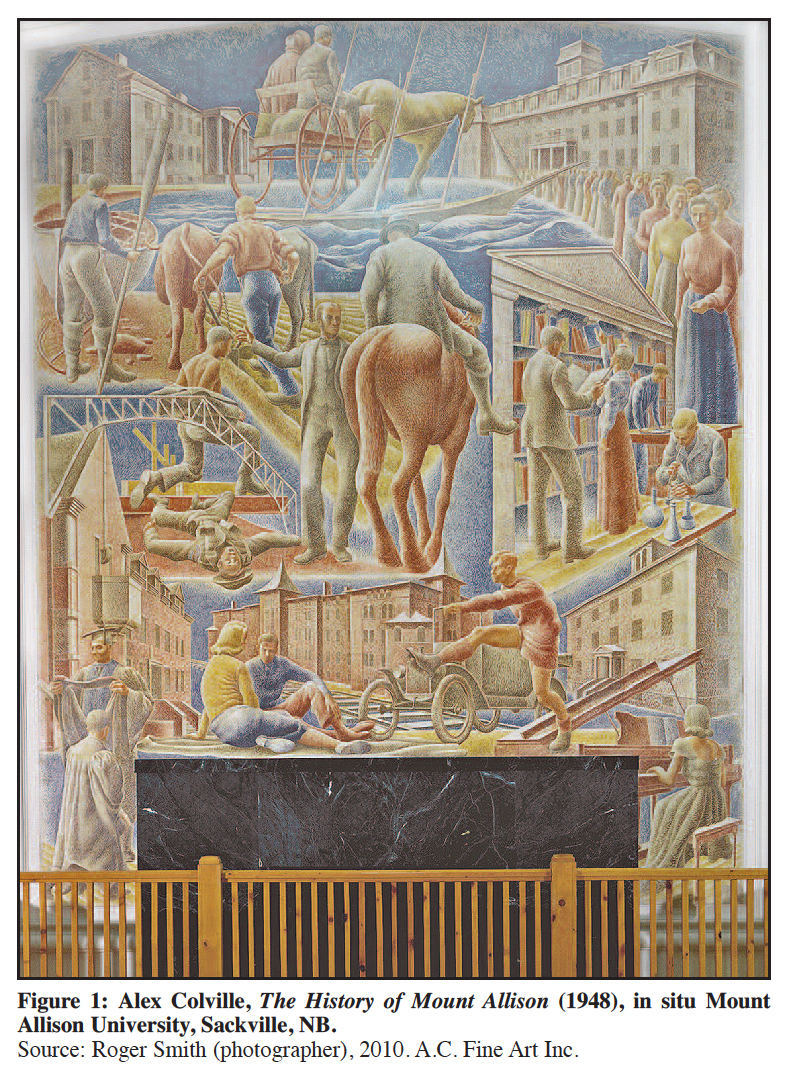

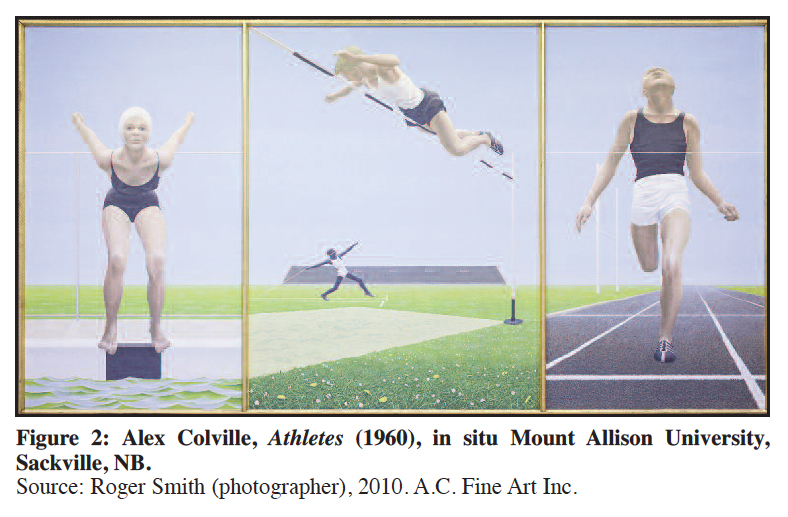

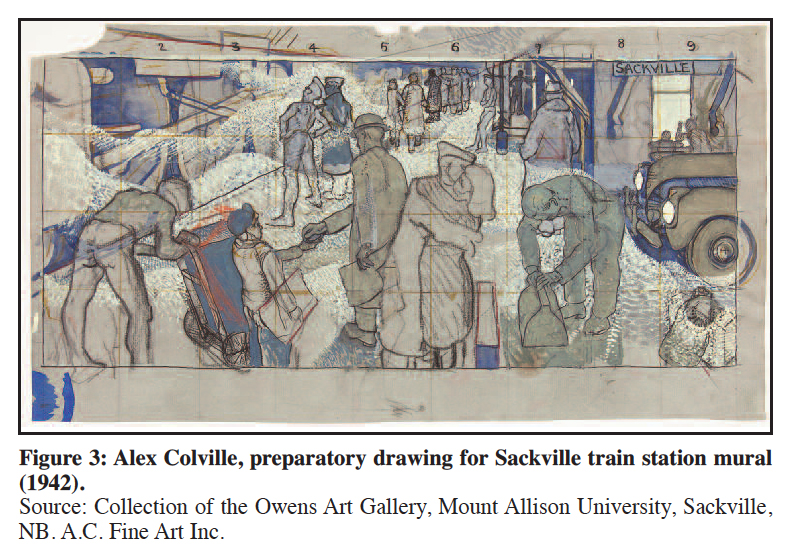

1 ALEX COLVILLE (1920-2013) is arguably Canada’s best-known artist of recent times. He has been the subject of solo exhibitions at the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. His work has been well documented in monographs, exhibition catalogues, and catalogue raisonnés. Not well known, however, is the fact that Colville produced at least three murals early in his career; two of these, The History of Mount Allison (1948 – Figure 1) and Athletes (1960 – Figure 2), are in situ on the campus of Mount Allison University campus in Sackville, New Brunswick. The third, entitled Sackville Train Station, was destroyed, although a preparatory drawing for this mural is in the collection of the Owens Art Gallery (Figure 3). Colville’s murals are of interest to us today both as evidence of his development as an artist and as significant examples of mural painting in Canada at the time. They also reflect Colville’s own ambitions. The History of Mount Allison, commissioned by Mount Allison University, can be considered a tour de force for an artist only 28 years old and at the start of his career.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 32 Alex Colville graduated in fine arts from Mount Allison University in 1942, and returned to teach there in 1946 after service as a Canadian war artist. In 1948 the university commissioned him to undertake a mural painting on the theme of Mount Allison’s history. Colville took the project seriously. He undertook extensive research on the history of the university, its buildings, and the various aspects of student life and produced in the process over 150 preparatory drawings, ranging from freehand sketches to schematics for the final composition. These drawings, donated by the artist to the Owens Art Gallery in 2002, reveal the evolution of the work. We can see, for example, that Colville changed his mind at one point in the process, replacing the image of an artist at his easel in the lower left of the composition with that of a graduating student receiving his degree.

3 For an artist so young and with no experience working on such an ambitious scale, the mural was a demanding project and, once completed, a remarkable accomplishment. In it, the complex problems of time-space relationships in a two-dimensional form are well handled. The composition revolves around the central image of a standing figure and a horse and rider, a direct reference to the Diego Velazquez’s painting The Lances – a work that depicts the surrender of the Dutch city of Breda to the Spanish in 1625 by showing the Dutch governor handing over the keys of the city to the Spanish conqueror. In Colville’s version, the central scene depicts the conversion of university founder Charles Frederick Allison to Methodism by an itinerant preacher on horseback. The figure of Allison himself is taken from a full-length portrait by William Gush in the Owens collection, a work that Colville would have known well from his student days.

4 The unfolding of Mount Allison’s history in the mural includes the representation of various academic disciplines, athletics, music, student life, and the importance of the education of women at the Ladies’ College. Other scenes in the mural tell the story of the Town of Sackville and environs, with sailing ships in the Bay of Fundy and the tilling of the land. The reference to war is also prominent in the painting. Coming as he did from his commission as a war artist, Colville was keenly aware of the human costs of war. Mount Allison students killed in battle are represented in the mural by the image of the fallen soldier.

5 Colville’s experience as a war artist had taught him pictorial techniques for narrative structure and the depiction of the figure in a setting. His time in Europe had also been crucial to the development of his interest in art history. He had spent two days at the Louvre in May 1945 where he was especially struck by Early Renaissance and Northern Renaissance painters and by Egyptian art. These experiences would inform his work for the rest of his life.

6 When Colville painted The History of Mount Allison, mural painting was a well-recognized and important art form that had been revived first by the Mexican muralists, notably Diego Rivera and David Siqueiros, and widely embraced as means of creating art for the people. While, for the Mexican artists, the mural was a weapon in the fight for political reform, in Canada mural painting was relatively free of political agendas. Certainly Colville’s murals are not political in any way, although they do carry a strong message about the individual human spirit.

7 Other key influences on the increasing popularity of mural painting in the United States and Canada were the growing number of paintings depicting American life. Loosely described as regionalism, or American Scene Painting, this movement is best understood as comprising in its heyday the work of Thomas Hart Benton, Stuart Curry, Grant Wood, and the hundreds of artists in America who, through the sponsorship of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), painted murals in many post offices and government buildings in the United States.

8 The popularity of mural painting as an art form quickly informed the training of young artists. Many schools and art departments across the country incorporated mural painting into their curriculum. At Mount Allison in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, fine art students were given assignments to design murals for specific sites in buildings all over the campus. Over the years, with renovations and changing tastes in public art, all of these student efforts have been removed and several are stored in the vaults of the Owens Gallery. However, Colville’s own student mural, Sackville Train Station, has not survived.

9 The mural Athletes was commissioned by Mount Allison in 1960 for its new athletics building. The 12-year span between Colville’s History of Mount Allison and this one is significant in terms of the artist’s developing career and his changing approach to his art. Athletes is a triptych, with two side panels each half the width of the central panel. While The History of Mount Allison is vertical in format and meant to be viewed from below looking up, Athletes is horizontal and meant to be viewed nearer to eye level. This difference in the viewer’s physical relationship to the work underlines Colville’s emphasis on the individual, rather than on narrative. Athletes is not an illustration of events, but an expression of existentialist themes that had become central in his work.

10 A number of significant events had taken place in Colville’s professional and personal life in the intervening years between the painting of The History of Mount Allison and Athletes. In 1952 Colville went to New York and formed a relationship with the Edwin Hewitt Gallery, a venue that specialized in the work of American realists and magic realists such as Edward Hopper, Jared French, George Tooker, and George Vickery – all artists Colville admired. In this post-war climate, often referred to as the Age of Anxiety, Colville was also drawn to French writers Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. The “extreme experience” and sense of anxiety or dread in the work of these artists and writers finds its own particular articulation in Colville’s work. The mural Athletes reflects the relationship between the figure and space, both physical and psychological.

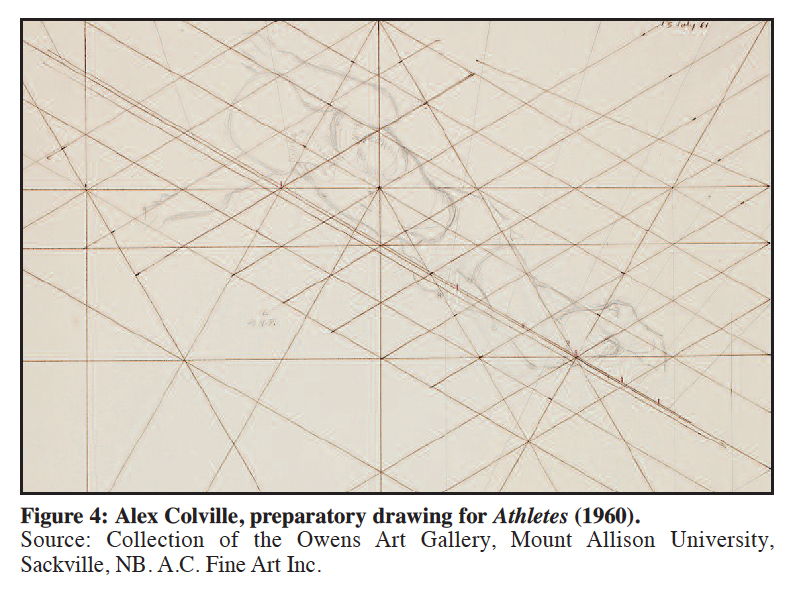

11 In the summer of 1949 Colville did no painting, devoting his energies instead to renovating his house in Sackville. The experience of building and of measuring marked the beginning of his rigorous use of geometry in all his artworks, both as an ordering principle in composing pictorial space and as a profound symbol of the human condition in a metaphysical sense. In Athletes, we see Colville employing complex geometrical forms to create the space into which he then inserts the figure (Figure 4). At the same time, Colville wants to reveal the underlying structure of the painting so that the geometric elements in the work serve a representational function – as, for example, the tape at the finish line, the goal posts, and the high jump bar. The two side panels of Athletes show a single figure placed frontally – on the left a woman who prepares to dive and on the right a runner about to cross the finish line. The central figure is suspended on a diagonal that extends his torso into deep space. It has been noted that these panels represent the beginning, middle, and end, thus adding a temporal comment to the spatial matrix.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 412 Murals are most often installed in public spaces. While this exposes them to viewers who might not venture into the more controlled environment of an art gallery, it also presents great challenges for those who act as their custodians. Both of Colville’s murals on the Mount Allison campus are in public buildings, in environments which have neither temperature nor humidity controls and which, until recently, offered no security measures for the protection and well-being of the work.

13 Athletes, in the Athletic Centre, is not adhered to its support wall, and in fact was temporarily removed to be included in the Art Gallery of Ontario’s travelling exhibition of Colville’s work in 1983 and again this year in the AGO’s current Colville retrospective. The mural was installed behind a plexiglass frame, and for many years fronted with a planter that passers-by and viewers used as an ashtray and garbage bin. A steam leak, creating a kind of greenhouse effect, caused the paint to flake. The university has since taken measures to stabilize the environment for this work. The planter was removed and the steam pipe sealed off. Owens Fine Art Conservator Jane Tisdale has recently repaired the damage done by the steam leak, and discussions have begun with the university administration to address the complex issues of its display and care when the work returns to campus after its tour.

14 The History of Mount Allison was installed in 1948 in Tweedie Hall, a meeting room within what was at the time the principal men’s residence at the university. A contemporary photograph shows ashtrays underneath the painting as was typical of all public spaces of the day. The mural was painted on linen adhered to the wall above a fireplace with a chimney directly behind the wall surface. Open for many years, the chimney created dramatic fluctuations between the air behind the mural and the air on its surface. Windows in the room allowed exposure to high ultraviolet light – up to 400 lux in direct sunlight. Humidity in this space was also a problem. While the ideal environment for artwork is 45-65 per cent relative humidity (RH), Tweedie Hall in the summertime records humidity levels of 70 to 80 per cent RH, with wintertime levels of 15-30 per cent RH.1 And, as is the case with many murals, the medium and installation technique used in The History of Mount Allison have posed difficulties for conservation. The mural consists of large pieces of canvas attached with weak rabbit-skin glue to a wall that has shifted and cracked. As a result, nearly one-third of the canvas has detached from the wall in various “pockets” throughout. Egg tempera is notoriously susceptible to abrasion; hence damages from activities around the mantle area. Gesso is very porous, affected by moisture and fluctuating RH.

15 As early as the 1980s, there were discussions about removing The History of Mount Allison from the wall, attaching it to a rigid support, and then re-installing it. This huge project will likely need to be undertaken eventually because of the gradual detachment of the canvas from the wall, which continues slowly as the environment fluctuates over time. Certainly the care and upkeep of the Colville murals has emerged as a priority for the university as custodian of these two significant works.

16 Situated as they are in two of the most frequented buildings on campus, the Colville murals have a wide viewership. Indeed, it is likely that the audience the university had in mind when the murals were first commissioned was only in part its resident students and staff and that, in fact, Mount Allison was looking beyond the local in order to signal its ambitions nationally and internationally to establish itself as a modern institution aware of current art world trends that saw mural painting as the preeminent public art form.2 The murals continue today to afford the university gravitas, especially since Colville’s reputation has soared since the first of the murals was installed. Visitors continue to make special trips to campus to view the Colville murals, as do school tours and other organized groups. And while it may be less obvious what the murals mean to the students who live with them daily, there is no question that, to date, Colville’s work has had great staying power. Understanding Colville’s legacy in the future, especially within the unique context of the artist’s alma mater, will form an interesting and challenging field of research.

GEMEY KELLY

- In 1970 it was observed that the linen was pulling away from the wall, and that there were scratches and paint loss, mostly around the fireplace mantle from various activities in the hall.

- In 1979 conservators from the Canadian Conservation Institute treated the mural, and cleaned and consolidated flaking paint. The suggestion was made to install a permanent barrier around the base, to limit activities in the hall, and install window blinds.

- In 1980 damage was reported, with resulting paint loss near the centre from steam and/or dripping liquid which dissolved some of the conservators’ fills and inpainting done the year before.

- In 1983 Ian Hodkinson from the Queen’s University Art Conservation program supervised conservation work, including filling and inpainting losses.

- In 1986 more vandalism was reported, leading to the recommendation to install a barrier around the mural and to control the use of Tweedie Hall; a little wooden fence was installed soon after.

- In 1994 the chimney was capped off and insulated.

- In 1997 scaffolding was installed and areas of damaged paint examined and treated. Flaking paint was re-adhered, and losses of paint filled and inpainted.

- In 2012 a glass barrier was installed in front of the mural, providing ideal viewing conditions, circulation of air, and protection from both intended and inadvertent damage to the mural.