Forum

Miller Brittain’s Mural Cartoons for the Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital:

From Creation to Conservation

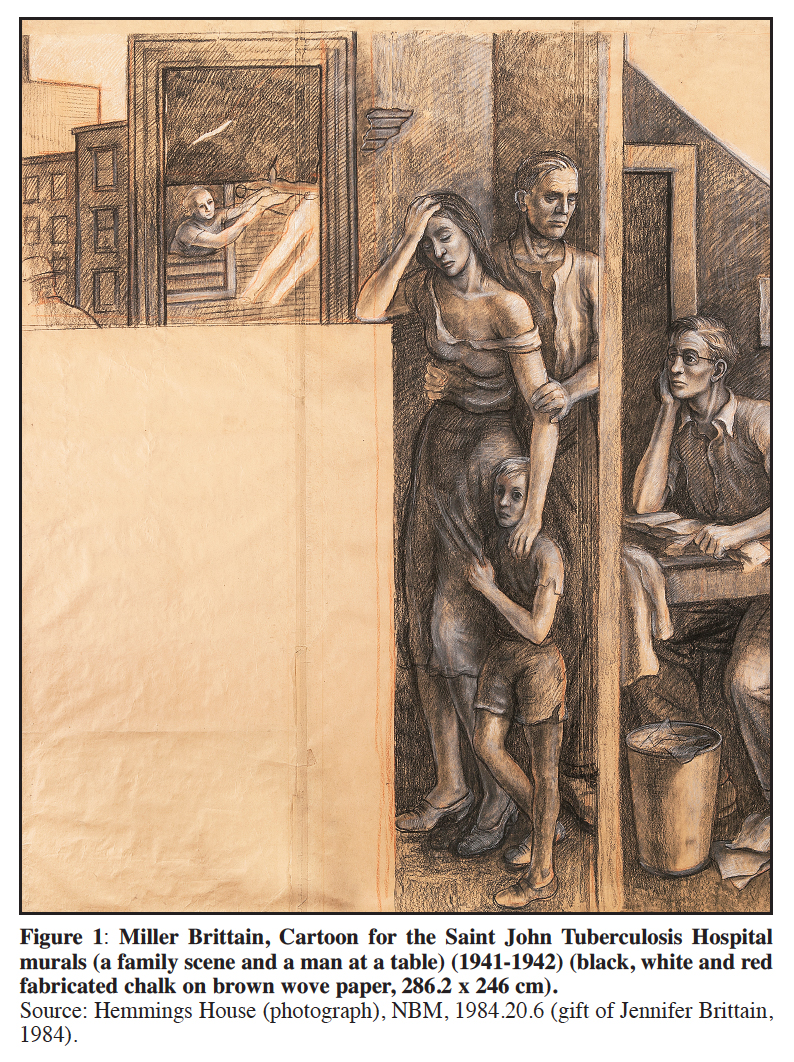

1 VIEWING MILLER BRITTAIN’S striking Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital mural cartoons for the first time prompts several immediate responses. These are unusually large drawings: each of the 11 drawings is full scale, about 2.5 meters square, as they would have been painted in the halls of the hospital. They are vibrant, developed drawings using three colours of chalk (red, black, and white) on a brown kraft paper support, which also serves as a middle ground colour in the compositions. The artist was a very capable draughtsman and invested significant time and energy to develop the compositions beyond line and the suggestion of form to include individualized appearance, expression, and a sense of light and shadow. They are beautiful and powerful works in their own right (Figure 1). The mural was never painted, but the full-scale preparatory drawings were retained by the artist and the New Brunswick Museum (NBM) as a major artistic achievement of Brittain’s pre-war oeuvre. The cartoons were completed immediately before Brittain began active service as a bomb-aimer in the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1942. After the war Brittain continued his work as an artist but his artistic work, very much affected by his wartime experience, took a new path.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 12 In March 1966 the NBM hosted a retrospective exhibition of Miller Brittain’s work, less than two years before the artist’s death in January 1968. The cartoons were on public display for the first time in decades, and black-and-white photographs of them were published in the NBM’s Art Bulletin.1 These photographs became the basis for future scholarly discussion of the drawings. The drawings themselves would not be accessible to the public again for another 40 years.

3 In the years between 1966 and 2006, the cartoons attracted scholarly attention because of their significance to Canadian art history.2 Very few scholars, however, had the opportunity to see the original drawings. Limited access to the cartoons has been due in large part to the size of the drawings and the related difficulty in handling, displaying, and photographing them. Beginning in the 1960s, the NBM made attempts to preserve the cartoons and worked on plans to repair them and present them to the public.3 These initiatives were frustrated in each instance. Fortuitously, because the drawings were handled infrequently and were well stored, they have remained in relatively good condition.

4 In 1984, after receiving the suggestion that “if the works were donated to the museum there is a good chance of us having them professionally restored,” the artist’s daughter, Jennifer Brittain, gave the drawings to the museum.4 It was hoped that the resources required to complete the conservation treatment of the cartoons could be found, thereby preserving them for the benefit and appreciation of the public then and into the future. Finally, in 2006, a convergence of factors helped to move the long-anticipated project forward.

5 This essay will outline the work that has been undertaken to conserve Brittain’s tuberculosis mural drawings between 2006 and the fall of 2013. The focus will be on how the conservation treatment of the cartoons became an institutional priority for the NBM and how the conservation of the cartoons was, ultimately, a project supported by a number of collaborating institutions. Ultimately the unique requirements of treating these enormous drawings have allowed the museum to present the public with a glimpse of the behind-the-scenes work of the museum conservation staff, thus fostering a new and intimate understanding of Brittain’s brilliant drawings.

6 In 2006, in anticipation of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery’s retrospective exhibition, Miller Brittain: When the Stars Threw Down Their Spears, the condition of the Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital mural cartoons was once again discussed, this time by the current generation of NBM staff including CEO Jane Fullerton, Curator of New Brunswick Cultural History and Art Peter Larocque, and Claire Titus, a conservator with a specialization in the conservation of art on paper. With museum administration and curatorial interests engaged, the drawings were examined over five days in a makeshift workspace in one of the museum’s galleries, one of the few spaces large enough to unroll these enormous drawings. Since it had been more than 20 years since the drawings had been unrolled, it was the first time that any member of the team had seen the drawings for themselves. Excited by what lay before them, team members resolved to see this conservation project through to completion.

7 The 2006 examination of the drawings revealed that they could not be displayed in their current condition. The artist had assembled the paper support for each drawing using three separate sheets of kraft paper, taped together using water-activated brown paper tape. Many of the original joins had failed. Later applications of masking tape held the joins and tears but threatened the integrity of the art with potential staining and the inevitable failure of the masking tape repairs themselves; as the masking tape becomes desiccated, the carrier separates from the adhesive layer and no longer supports the damaged paper. The NBM team determined that it was a high priority to treat all 11 drawings as a single artwork to avoid preparing one drawing for display, which might become over-exposed while the others might never be seen. However, there would not be enough time to prepare all 11 drawings for loan and display as part of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery’s travelling exhibition.

8 Nonetheless, in the summer of 2007 the NBM supported the Beaverbrook Art Gallery’s Miller Brittain: When the Stars Threw Down Their Spears by displaying a selection of the cartoons in four, daylong events at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery. The drawings were shown lying horizontally for a number of hours to limit exposure and to display them in a way that did not require mounting. Larocque and Titus were on hand to discuss the artistic, historical, and conservation issues with an interested public. A similar program of display and interpretation was offered when the Brittain show came to Saint John and was installed at the NBM in 2009.

9 Bringing the drawings to the public, even briefly, elicited interest and support from scholars and devotees of Brittain’s art. In addition, it was clear that the subject matter of tuberculosis was also of great interest to the public. There was also curiosity about both the condition of the drawings and what would be required to preserve the drawings so that the entire series could be displayed for the public. This enthusiasm signaled the importance of the drawings to the public and, further, raised the conservation treatment of the cartoons to an institutional priority.

10 It was obvious that the conservation treatment project would demand resources beyond those that could be afforded by the museum alone. But how much time was required and what resources were needed? These questions had to be answered before the conservation project could begin. Towards that end, the NBM developed inter-institutional partnerships and sought support from public granting agencies. The first significant collaboration came in the form of support from the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI). In order to establish a conservation treatment approach for the entire series of the Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital mural cartoons, the CCI invited Titus to travel to the CCI in Ottawa in the winter of 2009 with one of the drawings in order that it could be photographed, examined, and analyzed. Working closely with the CCI’s Senior Conservator of Art on Paper Sherry Guild, and in consultation with other conservators and conservation scientists, Titus’s six weeks of work resulted in specific observations about the condition of the drawing (the pH of paper and the media and adhesives used) and recommendations for the conservation treatment interventions (methods, materials, and equipment) required for all of the drawings in the series. The research and analysis done at CCI also provides much guidance to current and future custodians of the cartoons regarding the parameters of their physical requirements and limitations. Further, the CCI’s endorsement and “in kind” financial support of the NBM plan to conserve the cartoons served to leverage further investment in the undertaking by validating the project as an institutional priority requiring exceptional museum resources and by informing the conservation treatment work to be accomplished at the NBM. Thus, the door was opened to potential funding and training opportunities for emerging Canadian conservation professionals.

11 The first priority for both conservation and curatorial purposes was to produce colour photography of the mural cartoons. As a first step in conservation treatment, photography provides an important visual record of artifacts. Prior to 2011, the only photographs of Brittain’s mural cartoons were the black-and-white images taken in the 1960s. These prints were woefully poor representations of the vibrant and complex drawings; colour photography of the cartoons would offer new and more accurate visual records for study and discussion by scholars. Working with Mark Hemmings of Hemmings House Productions, in space provided by the Imperial Theatre, one day was booked to photograph all 11 drawings using the stage of the theatre and the theatre’s man-lift to raise the photographer to the required distance from the drawings.

12 With photographs in hand, and exactly 99 years after Miller Brittain’s birth, the NBM’s Gallery Three was opened as a publicly accessible conservation treatment workspace on 12 November 2011. In museology and in conservation circles it is currently seen as very desirable to raise public awareness of what the museum does behind the scenes.5 Highlighting the role of the museum, raising awareness of the role museums play in preserving our material history and culture, and exposing the general public to the field of conservation are seen as helpful, if not critical, ways to rally financial and popular support for the work of the museum. With a greater understanding of the work that goes on in a museum, a greater appreciation for the role of the museum will surely follow. In keeping with these trends, the long conservation treatment project of Brittain’s cartoons was turned into a dynamic and engaging exhibition. With a large public gallery serving as a dedicated conservation workspace, visitors had opportunity to learn about Brittain’s art and about the conservation procedures undertaken by the museum to preserve its collection while watching the slow-moving conservation treatment progress over many months.

13 The work of conservation treatment was carried out with the assistance of internships made possible through the Young Canada Works (YCW) program. In 2011 the NBM was granted the first of three consecutive annual YCW internships to fund a recent graduate of a conservation-training program to begin a post-graduate internship in paper conservation. After an orientation, the competitively selected interns worked on the conservation treatment of the cartoons under Titus’s supervision. Danny Doyle worked as the first post-graduate paper conservation intern (funded by YCW) from September 2011 until June 2012. As a graduate of Algonquin College’s Applied Museum Studies program, Doyle had received training in conservation and also brought experience in public interpretation to the project. He created examples to illustrate the consequences of using poor-quality materials such as masking tape and installed an exhibit case to show how light and handling can damage collection materials. Doyle investigated and developed an appropriate mending technique using double-sided acrylic and methylcellulose mending tissue, to be used in areas where original brown paper tape had failed. He completed the conservation treatment of two of the cartoons and was available to the public several afternoons each week.

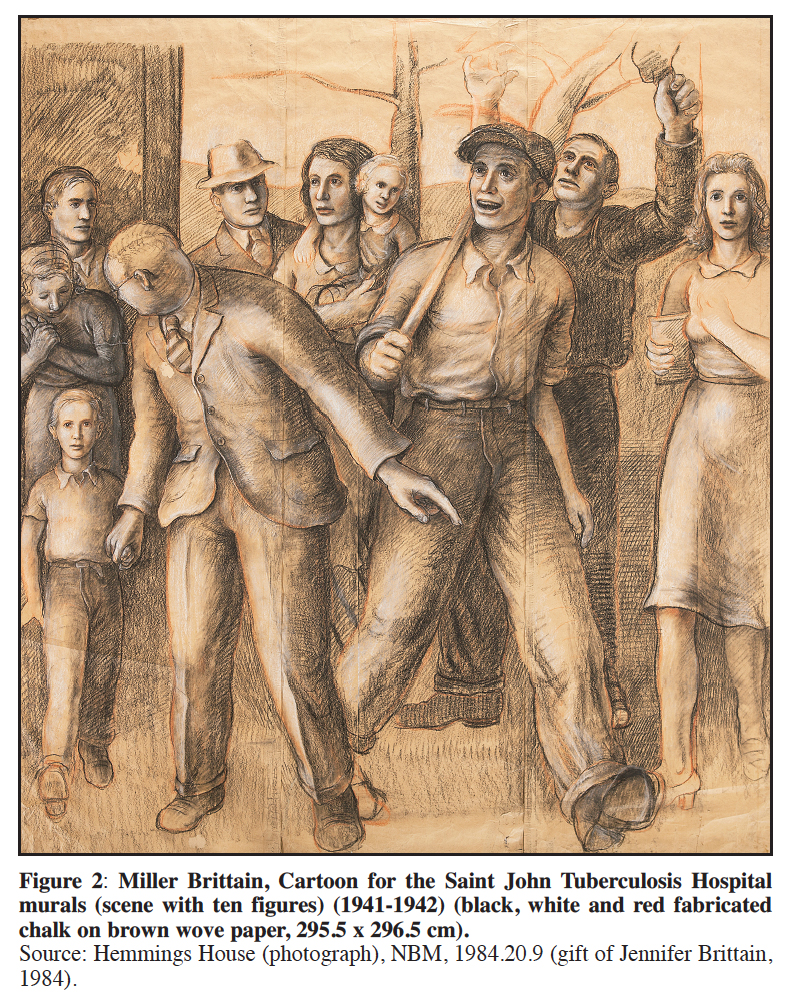

14 The second YCW post-graduate paper conservation intern was Jeanne Beaudry Tardif, then a recent graduate of Queen’s University and now Team Lead, Conservation at the Library of Parliament. Beaudry Tardif came with paper conservation experience and worked from August to December 2012. She continued the pattern of interpretation established by Doyle and added new and further-refined treatment techniques and documentation methods; she also improved documentation of the treatment by including videos to demonstrate repair methods and added the use of electric erasers to the methods used for adhesive removal from the most fragile areas of paper. Despite a demanding public schedule, due to the busy fall season of cruise ship visitors, Beaudry Tardif completed the conservation treatment of four cartoons. Another Queen’s graduate and the project’s third intern, Moya Dumville, who was funded by the NBM after the YCW funding for the year had been applied to Beaudry Tardif’s internship, added social media to her conservation and treatment work on the cartoons. Dumville posted on the progress of the project through an internet blog and on her personal twitter account. Media interest peaked at this time. One event that helped to gain media interest was the NBM’s marking of World Tuberculosis Day (or World TB Day) on 24 March 2013.6 The public event featured Brittain’s cartoons, the conservation project, and information about the history and treatment of TB. Adding a contemporary perspective on TB to the interpretation of the cartoons was unexpectedly enriching and brought new people into the gallery to learn about the project. Interestingly, Brittain’s depiction of the spread and treatment of the illness in the 1940s reflects many contemporary concerns with resurgent TB epidemics in the 21st century.7 TB remains a horrifying disease, even in a world where there is a cure. Accordingly, the optimistic concluding statement of the cartoons’ narrative – health will be restored – remains a relevant and pressing goal (Figure 2). In the final cartoon, Brittain shows previously stricken characters seen earlier in the narrative emerge into the outdoors healthy and celebrating. It was not, in fact, until after Brittain completed the cartoons, in 1943, that streptomycin was first applied to the treatment of TB, ushering in what would become the swift and effective treatment of the disease with antibiotics.8

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 215 Jayme Vallieres, another recent Queen’s University graduate, was the fourth and final intern working on the conservation treatment project. Vallieres’s internship, like those of Doyle and Beaudry Tardif before her, was funded through YCW. She completed the conservation treatment of the final cartoon in November 2013 and researched storage and display methods for the cartoons. It is important to emphasize that conservation treatments are painstaking, repetitive, and time-consuming processes. Photographs were taken at each step. Many centimeters of masking tape were removed using scalpels, solvent vapour, fine metal bristle brushes, and a variety of crepe and vinyl erasers. It takes about an hour to remove two centimeters of masking tape, and the time it takes to treat each of the cartoons is directly dependent upon the amount of tape that there is to remove. Tape staining in non-image areas was removed using a small vacuum suction table and appropriate solvents. Tears and paper joins were reinforced on the verso using Japanese paper and wheat starch paste. Where the paper tape had failed, a double-sided acrylic and methylcellulose mending tissue was used to anchor the sheets of paper where they overlap. Treatment time has varied from four weeks to three months per cartoon.

16 In spite of the painstaking nature of the work, public interest in the exhibit of the conservation treatment was strikingly positive. Some visitors came specifically to see the drawings while others came upon them coincidentally, but most were engaged by their impressive nature and beauty. Visitors were interested in discussing the drawings, Miller Brittain, the history of tuberculosis, and the Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital. The education, skill, and experience of the interns were also recurring topics of conversation, and the interns were able to tell many visitors about a facet of the museum world about which the visitors previously knew little or nothing.

17 In April 2014, the NBM received the Canadian Museums Association Award of Outstanding Achievement – Conservation for the conservation of Miller Brittain’s Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital mural cartoons. The CMA acknowledged the success and significance of the project:

The physical stabilization and preservation of the cartoons through conservation treatment, a longstanding NBM ambition is now complete. Plans are moving forward to determine a means for display. Since 2006, the project to have Brittain’s monumental drawings conserved has progressed, slowly but steadily, through planning, collaboration, and a commitment to bring the Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital mural cartoons to the public eye. In so doing, the NBM has preserved one of New Brunswick’s great art treasures, made colour photographs to assist scholars and the public to have greater appreciation and access to the drawings, shown the public what the field of conservation is in a museum context, and provided important work experience and mentoring for emerging conservators. To make this happen, it was necessary for the conservation treatment of the cartoons to become an institutional priority for the NBM and, given the climate of fiscal restraint, the conservation of the cartoons required the support and involvement of a number of collaborating institutions and funding sources. It is hard to see how this work could have been accomplished in any other way.10

CLAIRE TITUS