Forum

The Peripatetic Journey of Miller Brittain’s The Place of Healing in the Transformation from War to Peace

1 SINCE ITS OFFICIAL UNVEILING at the Lancaster Department of Veterans Affairs Hospital (DVA) in West Saint John, New Brunswick, in May 1954, Miller Brittain’s mural, The Place of Healing in the Transformation from War to Peace (Figure 1), has endured repeated relocation in an ongoing search for a suitable and permanent home. The mural’s narrative confronts viewers with three diverse images: a devastating battle, an operating room with a surgical procedure underway, and a futuristic vision filled with optimism and co-operation. Brittain’s mural shows modern medical intervention as facilitating victory in a great battle. It was designed for the intended installation site – a veterans’ hospital – but was also inspired by his personal military experience. Originally intended to honour the sacrifices of Second World War veterans, its forceful message became diluted, and occasionally regarded as problematic, as it moved to different venues and was seen by various members, and new generations, of the viewing public. Currently (August 2014), the mural is in storage at the New Brunswick Museum (NBM) awaiting a final decision on its ultimate destination and display. Given some of the conflicting attitudes towards aspects of its message over the past six decades, it is providential that the mural has survived at all.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 12 Miller Gore Brittain has been widely acknowledged as one of the country’s outstanding artists and draughtsmen. The son of James Firth Brittain and Margaret Bartlett Lord, he was born on 12 November 1912 in Saint John, New Brunswick. After his early art studies in Elizabeth Russell Holt’s class at the Saint John Art Club and graduation from Saint John High School, he made his way to the Art Students’ League in New York. There, between 1930 and 1932, the creative approaches and philosophies of two of his teachers, Harry Wickey (1892-1968) and Mahonri M. Young (1877-1957), had a profound impact upon his work. Wickey and Young were both etchers and sculptors and strong proponents of social comment as well as the use of the figure, and their influence remained with Brittain throughout his career.

3 After his studies, Brittain returned to Saint John in 1932. In order to support himself he pursued a number of odd jobs including general labour at the coal company that his father directed. In fact it was not until 1937 that he was actually listed as an artist in the Saint John City Directory, which was soon after his socially conscious and satirical drawings of everyday life caught the attention of a number of art critics – most notably Graham McInnes in Toronto and Robert Ayre in Montreal. Throughout the 1930s, Brittain’s scenes documenting the reality of living in a city so severely affected by the Great Depression resonated profoundly with the public. His works from this period have come to define not only Saint John but also the urban Maritimes nationally. By 1936, Brittain had been elected a member of the Canadian Society of Graphic Art and he exhibited in the society’s annual exhibitions between 1936 and 1939. He also displayed examples of his work at the annual spring exhibitions of the Art Association of Montreal in 1938 and 1939, and he was one of the artists who represented Canada at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. With the inclusion of his work in the Contemporary Arts Society members’ exhibition in 1940, Art of Our Day in Canada, he was one of the few New Brunswick artists to achieve some level of national prominence by the time of the Second World War.1

4 In the late 1930s Brittain became involved with a very large commission. He was approached by Dr. Russell Johnson Collins, the head of the Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital, to produce murals for hallways and alcoves of the facility. The project would feature images that showed the causes and effects of tuberculosis as well as depictions of the treatments, cures, and prevention. Though he subsequently took the project to a point of very well developed full-scale drawings, or cartoons, by 1942 it was clear that due to lack of funds, and possibly some other political factors,2 the commission would never be completed. The cartoons were then rolled up and put into storage at the NBM. Around the same time Brittain joined the Royal Canadian Air Force. His artistic career was briefly, but profoundly, interrupted by his serving as a bomb-aimer on at least 37 missions. In April 1945, he was appointed an official war artist and he lived and worked in Toronto for almost two years. His paintings and drawings from this period documented some of his experiences during his time on active duty. He also began a number of works inspired by the Bible as well a number that addressed serious concerns about the social realities of his native city, where he returned in 1947.

5 In 1949, Brittain was invited as the first participant in a series of solo exhibitions at the NBM featuring the work of contemporary provincial artists. On display were some of the 11 cartoons for his never-completed Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital mural project. The exhibition pamphlet also mentioned that “at present Brittain is under contract for another large mural . . . .”3 Ultimately this turned out to be the Lancaster DVA Hospital mural, The Place of Healing in the Transformation from War to Peace.

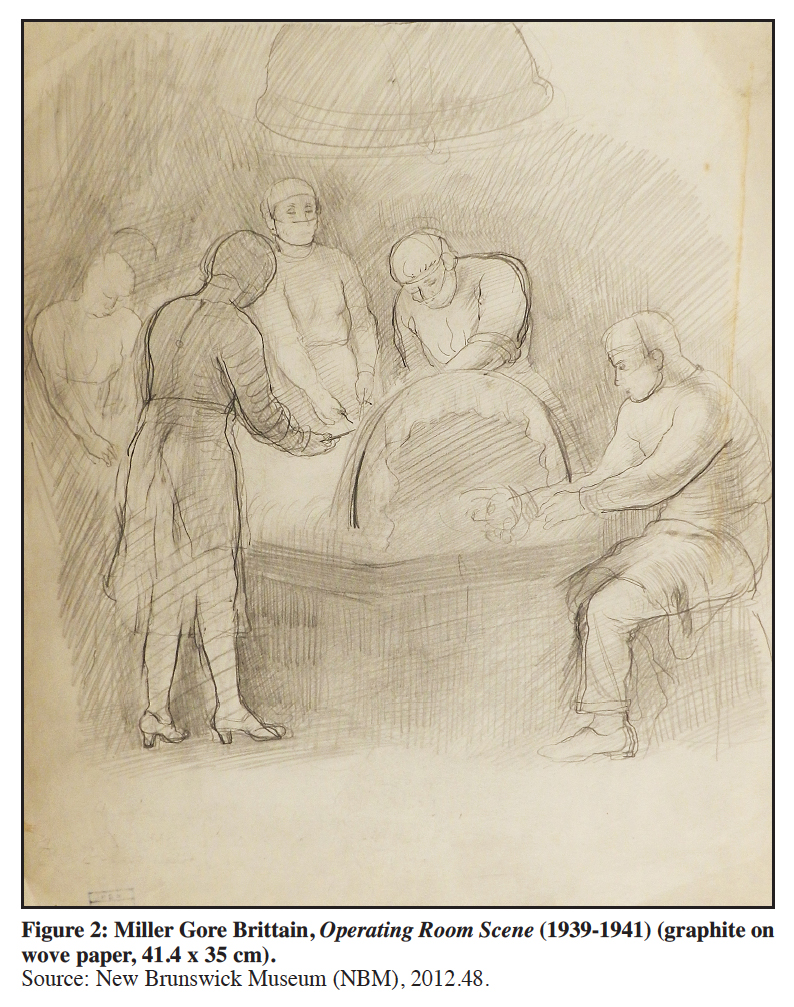

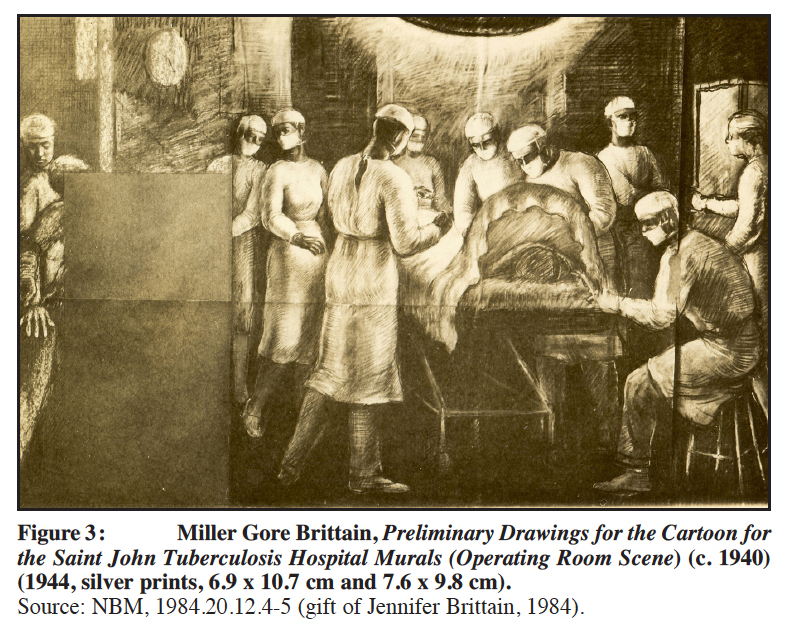

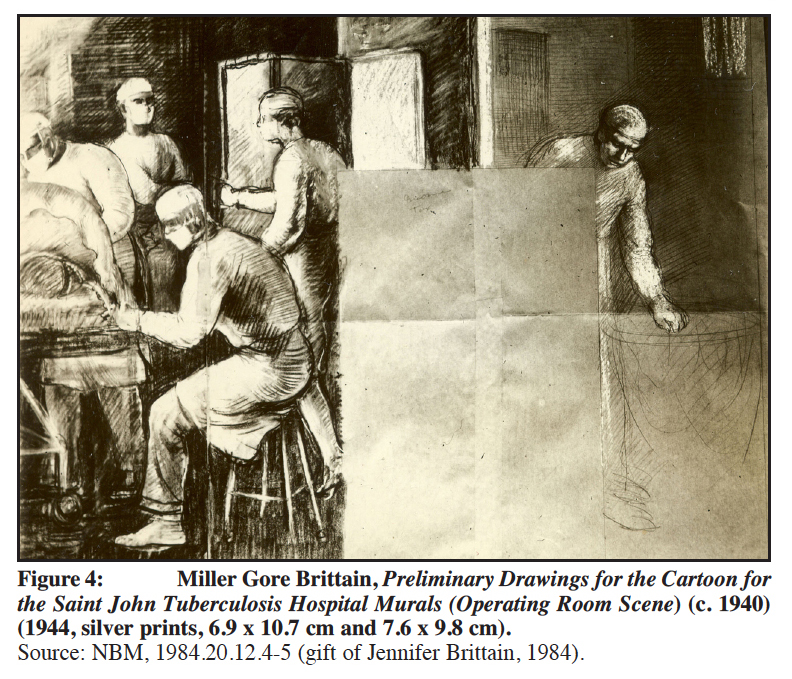

6 The story of the DVA mural cannot be explained without examining Brittain’s previous, uncompleted mural for the Tuberculosis Hospital – a project that began with the sketch Operating Room Scene (1939-1941 – Figure 2). In order to understand and prepare for the project, Brittain was invited to the hospital where he observed a surgical procedure. Brittain’s daughter, Jennifer, vividly recalls her father’s graphic account of the operation and the powerful impressions made by the sights, sounds, and odours – impressions that he never forgot.4 The sketch shows a patient undergoing thoracoplasty, the removal of several ribs in order to collapse the lung – one of the most invasive methods used in the treatment of tuberculosis. This drawing is probably the first preparatory sketch for the entire Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital project and it is the only one to have surfaced to date. It displays Brittain’s remarkable capacity for capturing the form and volume of figures with a minimum amount of descriptive line and very little cursory shading. This preliminary sketch was subsequently used as the basis for a more developed drawing. The only evidence of that particular drawing derives from documentary photographs that show it at its next stage of completion (Figure 3 and Figure 4).5 Drawn on brown kraft paper, the drawing shows figures and perspective that have been slightly altered from the original drawing but within a much more complex composition: rather than a single focus on the operating table, a broader sweep of the operating room is shown. To the left, a nurse assists a doctor to don surgical gloves and to the right a figure, perhaps a doctor, appears to discard something into a trashcan. In general, the modelling of the figures is more fully developed as well. The blank rectangular spaces seen in the photographs are the spaces where doorways in the hospital hallway would have been located and which would have not been painted in the final mural. By doing a rough calculation based on the photographs of the ¼ scale drawing and the incomplete cartoon, the whole operating room scene likely would have been about 9 feet x 27 feet (275 x 823 cm) when finished – easily the largest, most dramatic, and central theme in the whole mural project.6 It was also probably intended to indicate the immense importance accorded the hospital in the ongoing battle against tuberculosis. A decade later, the core of these ideas was distilled and incorporated into the DVA Hospital mural, The Place of Healing in the Transformation from War to Peace.7

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

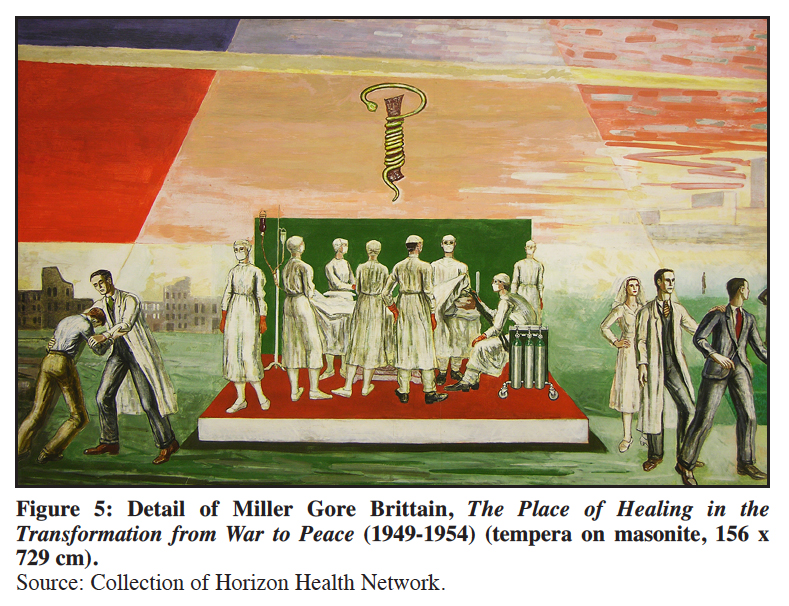

Display large image of Figure 47 Somewhat less ambitious than the extensive Tuberculosis Hospital mural concept, the theme of The Place of Healing in the Transformation from War to Peace unfolds in three vignettes within a single narrative with the pivotal role assigned to the medicine and the operating room. The left panel, with its violent red sky, includes a gigantic figure wielding a sword. The great sword is the traditional physical attribute of the red horse and rider in the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, which symbolizes war or mass slaughter. In the background are the charred ruins of a city with a tangle of supplicating, prostrate, and tortured victims in the foreground. The menace engendered in this panel is arguably the mural’s most striking and evocative imagery. In the central panel (Figure 5), a white-coated figure supports one of the victims from the scene of destruction. A nurse, garbed for surgery, is awaiting them on the nearby dais. In the very centre of the panel, surmounted by the Rod of Asclepius, the symbol of healing, a surgical procedure is underway. This panel has the most direct parallel with Brittain’s earlier work, and incorporates the concept of the critical importance of the actions necessary for healing. Also implicit is the notion of the extensive team required for the success of the medical intervention, a reference perhaps to a conviction that a co-operative society is essential in a civilized world. On the right of this panel, a doctor and nurse release a presumably cured patient into the future. The right panel incorporates some of the imagery from other Tuberculosis Hospital project cartoons, including family groups, students, labourers, architects, and others working together with building materials to construct an optimistic future symbolized by a bright sun shining over a gleaming metropolis.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 58 The Place of Healing mural was originally commissioned by the federal government for the Lancaster Department of Veterans Affairs Hospital (DVA) in West Saint John, New Brunswick. The site had been occupied by a military hospital since the 1920s. It comprised a number of buildings and the complex had undergone some demolition and reconstruction, with a new wing started in 1951 or 1952. The hospital was also a great source of civic pride, and it was included on the itinerary for important events such as the royal visits of Princess Elizabeth in 1951 and, as Queen, again in 1959. Dr. Russell Johnson Collins was responsible for the tuberculosis ward of the DVA and the mural was installed in the reception area there.8 In the mid-1970s the facility was decommissioned and the complex was sold to the provincial government. Patients were transferred to the newly constructed Ridgewood Veterans Health Wing a short distance away. The mural, too, was removed and re-installed in a reading room at Ridgewood and then later transferred to the lobby of the facility. By this time, all the exposure and moving had taken its toll. When the Horizon Health Network (then the Atlantic Health Services Corporation) became responsible for Ridgewood, the mural – in the meantime dismantled and stored – underwent a full conservation assessment and treatment. The report noted that the upper central panel had been broken in the removal attempts and a triangular section was missing. As well, the paint layer in several areas had been compromised by ill-advised attempts at surface cleaning.9 The final treatment included replacing the missing portions, inpainting, selective glazing, and varnishing. After review by a hospital board committee comprising a doctor, nurse, hospital administrator, board member, veteran, art community representative, and a citizen-at-large, it was decided that one of the walls in the lobby of the Saint John Regional Hospital was suitable. There it was installed and officially unveiled on 11 May 1991.10

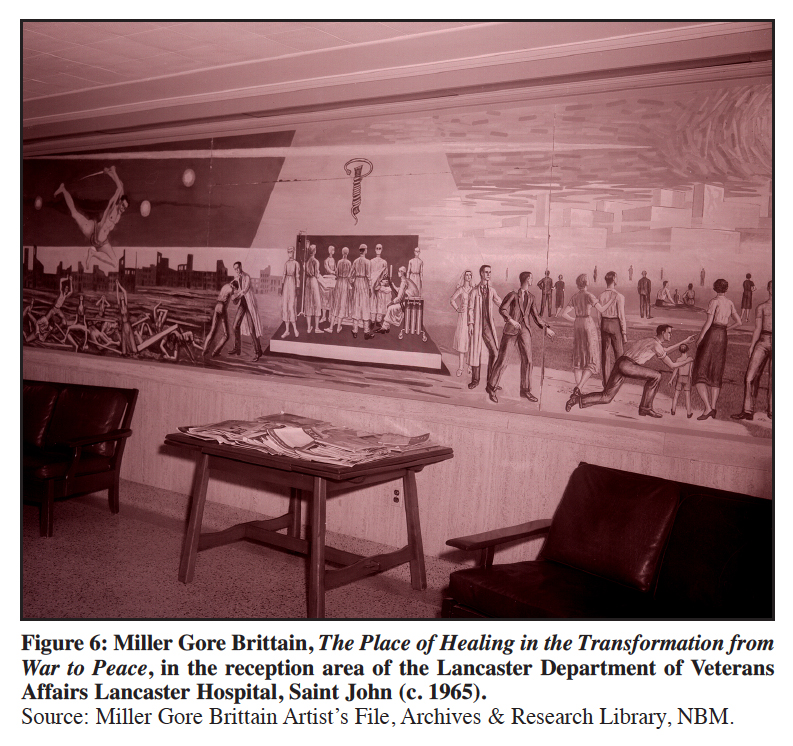

9 The graphic depiction of war and destruction in the left panel has been the subject of much controversy. In its original location, the reception area of the DVA Hospital (Figure 6), the mural was viewed more directly and viewers were more likely to be able to read its narrative sequence. Located at eye-level and in a more confined space, the mural would have been viewed as a series of successive and progressive scenes. It was also more likely to be experienced by someone directly influenced by war and its aftermath. In this setting, Brittain’s mural’s narrative would neither have been incongruous nor contentious. As time passed and a mental distance from the horrors of war increased, this strong reminder of mortal struggle and sacrifice seems to have become generally less acceptable. Its relocation to the Saint John Regional Hospital, though well intentioned, was problematic. Fifty years removed from involvement in the Second World War, the staff, patients, and visitors at a general hospital would bring distinctly different expectations and attitudes to an artwork removed from its original context.

Display large image of Figure 6

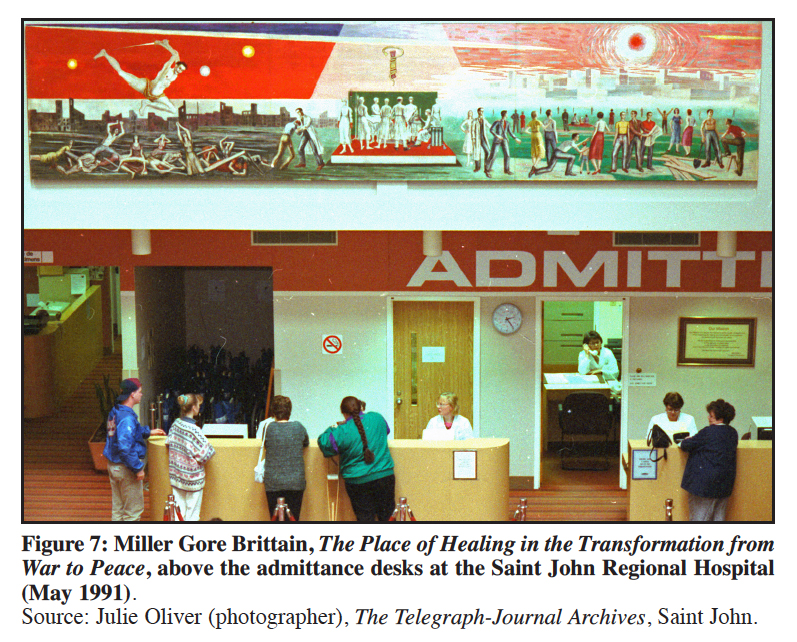

Display large image of Figure 610 A recurring claim in newspaper reports discussing the mural in the 1990s was that it was disturbing to patients and visitors. In 1995, citing a number of public complaints, staff at the Saint John Regional Hospital began circulating a petition asking for its removal and relocation to another area of the hospital.11 Staff did not unanimously support the petition, and in the end the hospital administration opted to leave the mural in place. Once situated high on the wall, the most prominent element of the mural was the fearsome figure with a sword. In order to see the work, viewers had to strain to look upwards or to view it from a mezzanine across the lobby (Figure 7). These physical limitations, combined with a lack of interpretive text or opportunity for education, had the effect of alienating the viewing public from Brittain’s fundamentally positive statement.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 711 In 2005, the mural was removed to ensure its safety during extensive renovations and repair to the lobby space. Since its installation there, the mural had experienced some minor damage as the result of a leak in the roof. Ensuring its long-term preservation was also a challenge in view of the uncontrolled environmental conditions in the lobby, which had direct access to the outdoors. Responsibility for the mural currently lies with the management and board of Horizon Health Network. The mural itself is housed in storage at the NBM and negotiations for its official transfer to the collection there have been under way since 2005. Between April 2007 and March 2010, the mural was displayed in seven facilities as part of a national travelling exhibition on the career and work of Miller Brittain.

12 All things considered, the NBM may be better situated to provide access to the messages that Miller Brittain intended. In an atmosphere less charged with anxiety than a modern hospital, the museum provides a venue in which viewers could learn of the relationships between this mural and Brittain’s other works, such as the preparatory drawings for the Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital murals. They would also have the opportunity to understand the mural more fully in relation to his personal experiences of the terrible violence of the Second World War and its impact on his artistic vision. The original setting of the mural – the DVA hospital – can be explained to viewers who will then recognize how Brittain’s depiction of modern medicine was both appropriate to that setting and was an eloquent metaphor for the kind of healing he thought the world needed in order to make the transformation from war to peace, for good to triumph over evil. In a museum environment, viewers will be able to take the time to consider the mural in its entirety and to be able to comprehend Brittain’s optimism for the creation of a better world – an optimism he was able to express even amidst the pervasive anxiety of the early years of the Cold War. The historical, intellectual, and artistic context of this mural’s creation, presentation, and reception are subjects that the museum is well prepared to communicate in an atmosphere conducive to teaching, inquiry, and reflection. Given the misunderstanding that has followed the mural in its travels, this kind of viewing experience, which proved difficult to achieve in the lobby of the Saint John Regional Hospital, is a most fitting approach to honour this aspect of Brittain’s legacy.

PETER LAROCQUE