Forum

Revision and Recovery:

Fred Ross’s Fredericton High School Memorial Murals

1 “ON THE WRITER’S FIRST VISIT TO SAINT JOHN, some years ago,” Avery Shaw wrote in 1947, “the impression of especial activity in art was remarkably strong, and has remained so.” Shaw had moved to Saint John to become curator of art at the New Brunswick Museum (NBM), but he continued to ask himself “why should this city, deplorable in its economic and physical conditions, produce so much creative vitality?” He could not explain it, but nevertheless “the fact of this vitality remains as obvious as ever. Painting is accepted as a lifetime pursuit.”1 Shaw had observed and then became a participant in an extraordinary period for artistic activity in Saint John. From the 1930s to the 1950s, the artists of New Brunswick’s largest city produced an impressive body of paintings and drawings, many of which have been recognized for their significance to the history of Canadian art.2 Through the financial hardships of the Great Depression, the tumultuous years of the Second World War, and continuing in the postwar years, the artists of Saint John found visual inspiration in their circumstances and locality – creating a body of work that is exceptional for a city of its size.

2 Fred Ross (1927-2014) is generally viewed as the youngest painter associated with the artistic “golden age” in Saint John. Ross was one of the most accomplished artists in Eastern Canada, and his work regularly hangs in the National Gallery in Ottawa. Yet beyond the books, honours, accolades, and numerous public collections that feature his drawings and paintings, the catalyst that launched his career was a body of work that he began in his teens: a series of large-scale public murals, executed during the 1940s and 1950s, that stand today as one of the most impressive and unique examples of socially conscious visual art in Canada.3 In a 1955 newspaper article on Ross, the first sentence immediately identifies him as “one of the outstanding mural painters in Canada.”4 Fred Ross’s early murals are hybrids inspired by multiple traditions, including Renaissance and American Works Progress Administration (WPA) murals, and, most significantly, by Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and the Mexican mural movement. Ross’s early murals are critical to understanding his development and inclusion in the professional art circles of New Brunswick.

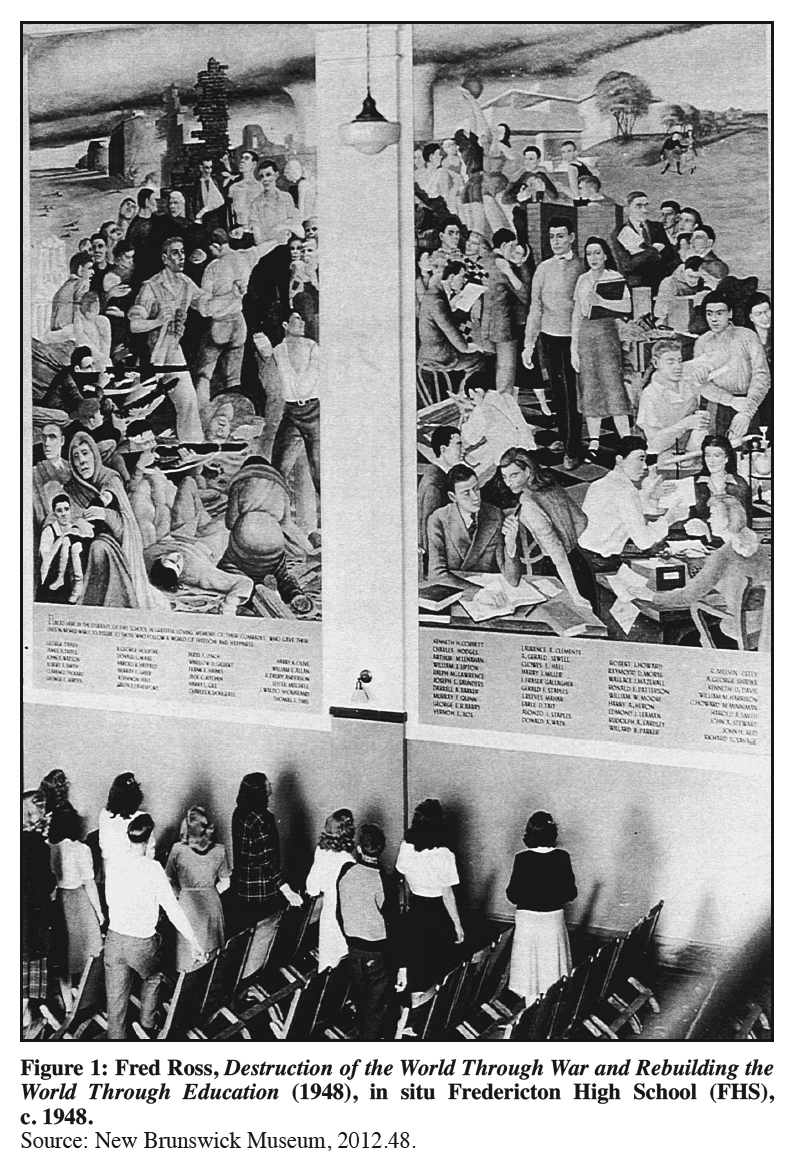

3 Ross’s principal murals, executed between 1946 and 1954, are Annual School Picnic (Saint John, 1946), The Destruction of War & Rebuilding the World Through Education (two panels, Fredericton, 1948 – see Figure 1), City Slums (Saint John, 1950), and Humanistic Education (Saint John, 1954). Another mural was painted in Mexico at the Hotel de la Borda (Taxco, 1949). While many of the murals were either removed or destroyed in the 1950s and 1960s, in a stunning turn of revisiting history the missing panels of The Destruction of War & Rebuilding the World Through Education were recreated in their full-scale glory in 2011 by an energetic group of studio artists using the original surviving cartoons. This mural diptych is now installed in the large gymnasium/auditorium at the Richard J. Currie Center on the University of New Brunswick (UNB) Fredericton campus (see Niergarth’s forum introduction, Figure 1 on p. 101). The second unveiling was a powerful and poignant affair, with the 84-year-old Ross in attendance along with a number of others who were at the original inauguration in 1948.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 Ross showed early promise in art as a youth, so he registered in the Art Program at the Saint John Vocational School in 1944 with the intention of becoming a commercial designer. Here Ross benefited tremendously from the tutelage of Ted Campbell, who taught at the school between 1934 and 1965. Campbell encouraged his students to formulate their work and subject matter from their daily lives and surroundings. He also brought his students into contact with local artists such as Jack Humphrey, Miller Brittain, Julia Crawford, and Kjeld and Erica Deichmann. Within this tight-knit community of artists and with the educational opportunities afforded at the Vocational School, Ross thrived.

5 One of the most admired art movements in North America before the Second World War was the production of large-scale murals that embellished public buildings, the most notable of which were those painted in Mexico by Diego Rivera. Seen as an art form for the benefit of all and not simply the rich or privileged, the Mexican mural movement was internationally acclaimed and inspired thousands of Depression-era murals throughout the United States and, to a lesser extent, Canada. During the 1940s the Saint John Vocational School placed a strong emphasis on muralism, as was evident through its monthly advertisements in Canadian Art magazine that cited “mural painting” and “old master techniques” as the sole non-craft-related fields of visual art study.5

6 Ross remembers Campbell having a genuine esteem for both contemporary and historical muralists in his classes at the Vocational School: “[Ted] was a real promoter of the Mexican and Renaissance artists. He felt that the Mexican mural paintings were the greatest murals since the Renaissance, so he was encouraging [us] to go [to Mexico] to look at them.”6 With this inspiration, Ross resolved to “not become too involved with commercial art techniques”; instead, he “would concentrate on drawing and figure composition with the idea of eventually becoming a mural painter.”7 Ross’s time at the Vocational School not only provided him with the technical foundation and confidence to design and paint murals, but also the physical space to carry them out.

7 In 1945, Campbell asked his students to design a sketch layout of “something you know” for a hypothetical mural to surround a large window at the Vocational School. Campbell was so impressed by the 18-year-old Ross’s design, entitled Annual School Picnic, that he encouraged him to produce a permanent, full-scale mural based on the drawing. Installed in 1946, Annual School Picnic surrounded a four-foot wide by twelve-foot high window within one of the school’s main stairwells. The mural portrays a lounging group of teenagers and young children on a summer day. While Ross used his friends and classmates as models, in the upper corner he drew a self-portrait – a practice he would repeat in most of his murals that followed. This mural met with strong local approval and it would prove to be enormously significant in establishing Ross as a serious muralist and as a nationally regarded young artist.

8 Publicity garnered by Annual School Picnic ultimately gave Ross the opportunity to produce an enormous and powerful mural at Fredericton High School (FHS) shortly thereafter. The minutes of the FHS Student Government Association of 29 May 1946 include the suggestion that “a mural as a war memorial” be considered to honour the memory of alumnae killed during the Second World War.8 Soon thereafter, on 21 June, the nationally circulated Montreal Standard profiled “Freddie Ross, untrained 18-year-old” in an anonymous multi-page feature that reproduced numerous photographs of Ross working on Annual School Picnic, along with close-ups of the cartoon drawings.9 Having read the article and spoken to the Vocational School’s staff, members of the Student Government Association commissioned Ross for $700 to undertake a large memorial mural project that would be the focal point of the school’s auditorium. Ross accepted the task, which was to occupy him full-time for 18 months from 1946 to 1948.10

9 Ross’s work on the FHS mural attracted attention and admiration. In 1947, Avery Shaw reported in Canadian Art that “Fred Ross is working on the cartoons of his huge mural for the Fredericton High School, a labour of several years, and he displays an increasing mastery of drawing and design; it is good to see an artist of his years being permitted to develop with a really big commission to exercise his talents.”11 As with Annual School Picnic, the subjects in Ross’s new murals were of high school age, but their complex treatment reflected a maturation of theme and ambition far beyond that achieved in his earlier mural. Where Annual School Picnic’s gathering of adolescent figures simply inhabit and animate a vignette attempting to portray carefree youth, the FHS murals see Ross venture into metaphor and symbolism to express his ideas about war and peace.

10 The enormous scale and contrasting subject matter of Ross’s pendant murals, entitled The Destruction Of War and Rebuilding the World Through Education, demonstrate his connection to modern Mexican and American muralists, many of whom expressed their interpretations of history and society through depictions of “good” and “evil” and inhabited by figures typical of their locale.12 Although there existed a clear physical split between the two halves of Ross’s mural because of their architectural setting on a wall divided by a pilaster, the visual unity of the entire work is successful. Ross chose atomic energy as the unifying motif for the two panels, with the exploding mushroom cloud acting as a compositional focus across the top of each panel, symbolizing the potential deadly fate hanging over the heads of the disparate groups below. While the division between the “War” and “Peace” images intensifies their contrasting symbolism, the overall geometrical layout, lines of movement, and similarly proportioned foreground/background and recessing figures work together as a cohesive symmetrical unit.

11 The scale and lofty proportions of Ross’s mural was key to its authority. Like the imposing vertical lines of a Gothic cathedral that compel the viewer to gaze upwards, instilling reverence through scale, the figures in Ross’s panels culminate in a pointed apex akin to the Gothic arch, 25 feet above the eye-level of the viewer. The size of the work is appropriate given the magnitude of the sacrifice of the former students: a small painting could not have the same overwhelming impact. The two murals, likely the largest paintings in New Brunswick at that time, each measured 16 feet high by 10 feet wide, and were installed on one of the main side walls of the school’s auditorium. Beneath the panels were inscribed the names of the commemorated students, placed in no particular order and prefaced by a short dedication by the student body.

12 The Destruction Of War is filled with the victims and consequences of armed conflict. The scene is a horrific spectacle of suffering and fighting in the shadow of a ruined urban landscape of no specific location. The image gives the viewer a feeling of claustrophobia, looking at a panel dense with civilians dressed in rags – some emaciated from hunger, others injured or lying dead. The whole is scattered with archetypal incidents of inhumanity: in the lower right corner male and blindfolded female figures are bound to wooden poles, implying torture; a man gazes upward in hopelessness with an open hand; a cluster of soldiers, some bandaged from head wounds, fire rifles; and a group of sunken-eyed figures at the upper right are based, according to Ross, on photographs of concentration camp victims at Bergen-Belsen.13 The mural’s central figure is a young “universal” soldier, with no distinguishing marks, equipment, or insignia to identify him. Ross wanted not to stress a specific religion, race, or nation but rather “the idea of the brotherhood of man breaking down all national barriers.”14 Ross carefully located a woman behind the soldier, as a round pack she carries becomes a metaphorical halo above him, placed like the corona in religious art.15

13 In the upper left corner of Destruction of War, Ross’s placement of ruined fluted columns is a device widespread not only in Renaissance painting as symbolic of destroyed civilization but also in much 20th-century painting as an icon of tyrannical empires and repressive governments as portrayed, for example, in The Eternal City (1934-37) by American artist Peter Blume. In Ross’s mural, the column ruins could function as an especially appropriate metaphor as both the regimes of Hitler and Mussolini had expressed their imperial ideals through the use of classicism as an “official” architectural language. Ross had earlier intended to make more direct reference to Europe’s fascist regimes in the Destruction of War. In a preliminary sketch, Ross has looming figures of Hitler and Mussolini as the central figures of the panel placed in front of an architectural background reminiscent of Albert Speer’s Nuremburg Rally stadium, complete with Nazi banners and dead, hanging victims of persecution.

14 Rebuilding the World Through Education establishes a positive contrast to Destruction of War through a less crowded panorama of young adults in settings related to school and social activities. In the lower half of the panel young men work at a drafting table, a chemistry laboratory, and a carpentry bench while other students gather around desks, talking and studying. The upper half is animated by a couple dancing, girls in harlequin dress with drama paraphernalia beside Ross’s self- portrait at the center left, students focusing on an older male teacher, and male and female athletes absorbed in basketball, swimming, football, and track in the shadow of a clean, modern structure surrounded by trees. The figures encircle a centrally placed static male and female couple, who are depicted as confident and at ease within their environment. Familiar academic incidents and dress in Rebuilding the World Through Education engage the student viewers in a projection of themselves in the panel, as young soldiers in The Destruction of War demonstrate that it was indeed their peers who fought the war and died in it.

15 Ross chose to mirror his self-portrait on the “Education” panel against the emotionally drained, conflict-weary faces on the “War” panel. He depicts himself looking directly at the viewer, implying a shared awareness of history but also confidence in his generation’s ability to take society in a better direction. This optimism, however, is overshadowed by the convergence of figures toward the central atomic cloud on the horizon, symbolizing the threatening Cold War that the world was entering. Torn between representing hope and post-war nuclear anxiety, Ross included a visual reference to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater in the upper central section of Rebuilding the World Through Education as a symbol of optimism achieved through modern architecture.16 Wright’s residential masterwork, begun in 1936 and completed by 1939, was seen as a spiritual communion with nature, embracing modern technology as an agent of peace.

16 A number of Ross’s figures, whether through size, demeanour, or pose, are metaphorically symbolic. Within The Destruction of War, they are the old woman with children at the lower left (hopelessness, the injury to civilians), the armed soldier with the head bandage (perseverance through peril), the standing male and female figures in bondage at the right side of the panel (victims of torture), both the standing young central soldier and the figure behind him with his back to the viewer – their arms outstretched in unison (strength, both military and of the private citizen) – and the dead soldier at the bottom of the mural (sacrifice). Conspicuously, his closed hand is touching the honour roll of names below, implying his association with them. In Rebuilding the World Through Education, the messages are more orderly, focusing on the two groups of young men and women at the bottom of the panel (socialization and discourse), the two male figures above them working (importance of study/knowledge), the group of attentive youths around the older man at the middle right-hand side (respect for elders/authority), the harlequin figure at the middle left-hand side (optimism and culture), and the dignified, confident couple at the center of the panel (youth as the future).

17 The composition of The Destruction of War and Rebuilding the World Through Education was influenced by murals familiar to Ross in both the United States and Mexico. One clear inspiration was Symeon Shimin’s Contemporary Justice and the Child, installed in 1940 in the Federal Justice Department Building in Washington, DC. In this work, Shimin presents an introspective woman supporting a young boy in her arms, positioned in the center of the work and gazing at the viewer. They are surrounded on the left by a group of poverty-stricken children in the shadow of a bleak factory building. The right side of the mural, in contrast, optimistically shows a group of bright, healthy, idyllic youths absorbed in sport and learning and upheld by two huge hands holding a draughting triangle and compass, symbols of planning and rationality. According to Shimin, his mural was “based on the theme of the Constructive versus Destructive elements in the life of a child. The Constructive: through intelligent planning – study and sport – all that helps to build a healthy body and mind ready to cope with vital problems when coming into manhood. The Destructive: being stumped in growth – willed through toil – destroyed by it – so that within the folds of a great country there exists, perhaps, the saddest and most tragic blight.”17 Ross recalls that “Shimin was an artist that I admired so much, and Ted did of course as well.”18 Campbell encouraged Ross to “call up” Shimin while in New York in 1946 and Ross met Shimin and spent an afternoon in his studio, discussing techniques of painting and planning murals.

18 Evidence of Ross’s admiration for Diego Rivera’s murals is also obvious in the FHS panels. Ross used pictorial strategies typical of Rivera’s practice, including the maintenance of the wall plane with a high horizon line, dynamic symmetry and proportion around the central axis, and the simple, bold modeling of figures.19 As in many of Rivera’s murals, Ross projected the action between a tightly defined foreground and a continuous sky high up on the picture plane and leading the eye upward. Although he does not recollect the influence of any one specific Mexican mural or artwork for the Fredericton High panels, Ross maintains that “from the Mexicans, I got the concept of the large idea: war and peace, and built on that. I had no experience in this type of [armed conflict] setting so I went through Life magazine for photos and ideas.”20

19 In the “Editorial” of the 1948 Fredericton High Yearbook, John W. Ward conveyed the significance of this memorial, which was reproduced on two full pages, to the students of FHS:

With great fanfare and speeches, The Destruction of War and Rebuilding the World Through Education were unveiled on the walls of the FHS auditorium to an admiring audience of students, parents, and relatives of the dead on 21 May 1948.22

20 In the years that followed, Fred Ross’s easel work brought him nationwide recognition but attention quickly faded from his murals. The Fredericton High School murals were removed in 1954 to allow the auditorium to be renovated into classrooms. They were placed in storage, nearly restored with the involvement of Ross and the FHS administration in the mid-1970s, and, soon after, thrown out by maintenance staff, who were unaware of their importance.23 The marginalization of Ross’s murals was somewhat redressed in 1993 with an internationally touring retrospective of his life’s work. Gathering material for this exhibition led to the chance discovery of the full-scale preparatory cartoons for the FHS murals in a NBM storage room. They became part of the exhibition and met with enthusiastic reception. This, in turn, led to the purchase of the cartoons by the National Gallery of Canada, whose curator of post-Confederation Canadian art deemed them worthy of inclusion in an exhibition celebrating the anniversary of the UN Declaration of Human Rights. In a strange reversal of fortune, the throwaway of a thrown-away mural became one of Ross’s most celebrated works, displayed in the principal museum of Canadian art.

21 The idea to re-create The Destruction of War and Rebuilding the World Through Education came in 2010 from the Fredericton painter, and longtime Ross family friend, William Forrestall. While walking by small framed black and white photographs of the murals near the Fredericton High School administration offices, he wondered if the work could be revived using an artist apprenticeship model. In April of that year Forrestall broached the idea to Ross, who swiftly gave his consent. Diving into the project as a volunteer organizer, Forrestall claimed “This is like a lost treasure. A hundred years from now I don’t think there’s going to be much concern that this is the second mural. It’s a historical record; it’s a memorial; it’s a great art treasure – one that was lost and has been re-found.”24

22 Along with Ross and his daughter Cathy Ross, Forrestall began carefully planning the logistics of the project. For ease of use and time, acrylic paint would be used rather than the tempera medium, although the painting would still be done on a matching masonite panel ground. As there was no strong interest from the Fredericton school board to remount the mural in FHS, Forrestall contacted the University of New Brunswick.25 The university fully supported the idea, and a large open wall in the new Richard Currie Center gymnasium was selected as an ideal site. The university provided $125,000 for the project, while the New Brunswick-based Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation gave an additional $50,000.

23 As Ross was no longer able to tackle such a mammoth project, a team of three painters – emerging artists Amy Ash and Sara Griffin along with Fred Willar, Ross’s good friend and former colleague at the Saint John Vocational School – was hired to paint the new mural from digital images of the original cartoons supplied by the National Gallery. As the team had no idea what the actual colours of the mural were, they made colour studies based on the tonal qualities of the black and white photographs of the original mural as well as asking Ross if he remembered any colour details; they also examined and compared Ross’s palate of his existing period murals at the old Saint John Vocational School building (now Harbourview High School). Ross acted as a general supervisor to the team, with artists Glenn Priestley, William Forrestall, architect John Leroux, and UNB employee/project manager Susan Montague as project advisors.

24 The completed mural was publicly unveiled to a packed house on 25 June 2011. Fred Ross and his daughter Cathy were in attendance, as were a number of individuals who were at the original mural’s unveiling in 1948. One of these was the prominent Fredericton businessman and philanthropist John Clark, who spoke at both events – as FHS student council president in 1948 and as a financial supporter in 2011. Both UNB President Eddy Campbell and Chancellor Richard Currie made laudatory remarks regarding Ross’s work and the deserved prominence of the mural in the university’s new building.26 Located on a high wall flanking the 1,500-seat performance court, the war memorial mural will be seen by many tens of thousands of visitors each year. Many of the names listed on Ross’s mural were also UNB alumni, including Kenneth Corbett, the first UNB student killed in the Second World War.

25 In January 1949, the Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada expressed dismay at the lack of a cohesive Canadian “socio-political” mural movement. The widespread successes of the well-known Mexican public art policy had not taken hold in Canada:

Fred Ross’s memorial mural at FHS was an exception to this judgment, an exception that did not long survive to prove the rule. The re-creation of Ross’s lost mural creates an opportunity to further our understanding of a vital period in Canadian art. It allows one of the most significant examples of a socially conscious mural ever painted in Canada to be given life once again. This re-creation is an appropriate honour for Fred Ross, a deeply dedicated and nationally renowned artist whose career began in and around the creation of this mural 65 years ago. It is a poetic instance of a lifetime’s work coming full circle.

JOHN LEROUX