Forum

New Brunswick’s Mural Legacy:

A Roundtable Forum

1 “THE MOST EXCITING THING,” PEGI NICOL MACLEOD wrote from Fredericton to a friend at the National Gallery in Ottawa in 1941, was that she had been commissioned to paint “a mural.”1 A year earlier, in an interview published in the Ottawa Citizen, Nicol MacLeod had called for a Canadian mural movement. What better way, she asked, could there be to memorialize Canada’s war effort?2 It was not in Ottawa, however, but in Woodstock, New Brunswick, that Nicol MacLeod was given opportunity to execute a mural herself. Reflecting on the experience, Nicol MacLeod was still enthusiastic: “Every artist should get off a few murals in a life time . . . the material spaces in murals are as wide open as the mental.” For her labour Nicol MacLeod was paid in kind with homespun and tweed materials produced by the school’s students and she invited other artists to do likewise: “With such good painters in the Maritimes, not to say elsewhere in Canada, more schools might have murals. Work for the credit and let the cash go. The labor will be repaid.”3

2 In New Brunswick between the 1930s and the 1960s more schools did get murals, as did universities, hospitals, train stations, churches, and other buildings.4 These were murals of a kind that Marylin McKay, in A National Soul: Canadian Mural Painting, 1860s-1930s, categorizes as “modern murals,” by which she means they were executed in modernist idioms and influenced by contemporary muralists in Mexico and the United States. McKay suggests that “modern” murals were rare in Canada: if this is generally true, New Brunswick must be regarded as an exception.5 On a per capita basis, but possibly even absolutely, artists worked on more “modern” murals in New Brunswick than anywhere else in the country. Artists whom Nicol MacLeod would undoubtedly have included among the “good painters in the Maritimes” worked for months, and in some cases years, on mural projects. Not all followed Nicol MacLeod in letting the “cash go,” but until recently one might have asked with the retrospect of a half century – thinking of murals hidden in storage, of murals physically damaged, sometimes beyond repair; of a petition calling for the removal of a mural; of murals uncompleted, lost, or destroyed – how has their labour been repaid?6

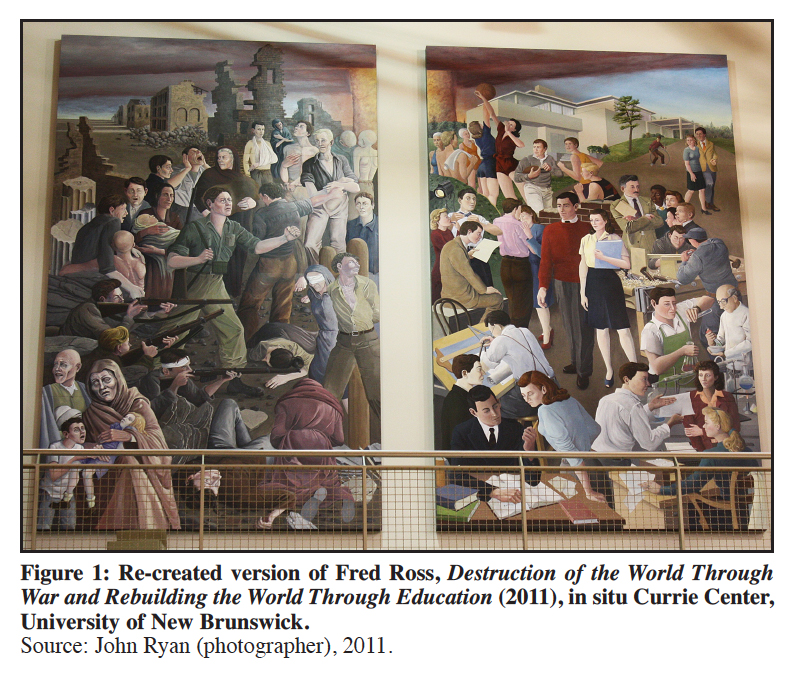

3 The answer to this question may be changing. In recent years, both individuals and institutions have engaged in efforts to preserve, restore, contextualize, and, in the extraordinary case of Fred Ross’s war memorial mural, to re-create physically New Brunswick’s “modern” murals. These efforts prompted a 2012 symposium in Fredericton entitled “New Brunswick’s Mural Legacy: The State of the Art.” The symposium, sponsored by the international research project “The Decorated School Network,” was held in the Richard J. Currie Center on the Fredericton campus of the University of New Brunswick (UNB) in proximity to the new version of Ross’s mural, The Destruction of War/Rebuilding the World Through Education (Figure 1).7 After the original panels had been missing for almost 60 years, a team of New Brunswick artists, under the guidance of Ross, re-created the mural for this UNB venue in 2011.8 This seemed an ideal location to contemplate the relationship between Ross’s work and that of other muralists with whom he was a contemporary in the province. Participants delivered papers on murals in Fredericton, Saint John, and Sackville. Given the difficulties a number of these murals faced in being understood and valued in the decades following their creation, participants considered the ways in which they might be conserved, displayed, and interpreted in ways that make them relevant to present and future viewers. Revised versions of five of these presentations are published here.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 In “Revision and Recovery: Fred Ross’s Fredericton High School Memorial Murals,” historian and architect John Leroux explains the history of Ross’s Destruction/Rebuilding. This war memorial, commissioned in 1946, commemorated the war-dead of the province’s largest secondary school, Fredericton High. Ross, who went on to a very successful career as an easel painter, was then a recent high school graduate and an aspiring professional muralist. When unveiled with much solemn ceremony at a well-publicized event in 1948, the mural was expected to serve for all time as a reminder of the human costs of war.9 In fact it only lasted on the school’s auditorium walls for six years. It was removed when the building was being renovated in 1954, languished in storage for years, lost, found (in damaged condition), and then lost for what seems to have been the final time in the 1970s.

5 Leroux explains the circumstances that led to the re-creation of the mural in the Currie Center. These included the fact that Fred Ross,10 though an octogenarian, was still a working artist able to participate in the project; that the patron, the University of New Brunswick, was supportive; and, finally and very significantly, that a network of local artists, activists, and scholars had kept the memory of the mural (and its destruction) alive and helped push for this kind of restorative action. Contemplating the story of the re-created mural in relation and comparison to other murals in New Brunswick and elsewhere raises important questions. What makes a work of art in a public space meaningful? How can such meaning, or value, be sustained for users of the space over time? Which works, or kinds of works, get preserved (or in this case, re-created) and why?11

6 In a discussion about these issues, one symposium participant noted that what the New Brunswick murals of this era shared in being designed for schools, universities, hospitals, and churches was an “institutional audience”; this meant that they were designed for spaces that people visited for purposes other than contemplating art. Such an insight suggests a possible reason why few of these murals have remained on the walls where they were originally installed. Renovations, for example, to an art gallery or a museum would be made with the preservation and display of works of art as a high priority; but this would not be and has not been the case for institutions such as hospitals or schools, which have different mandates and concerns to address. To preserve a mural requires various kinds of expertise. What environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, light) need to be controlled? What steps need to be taken to regularly maintain or, when damaged, restore a mural? What is the mural’s artistic and historic significance – in other words what makes it worth preserving – and how can this significance be communicated to viewers? The symposium brought together historians, curators, conservators, local artists, and heritage activists, and the papers published here reveal how it is truly a community effort to ensure that large-scale murals survive both materially (as physical objects) and symbolically (as meaningful works that are understood in historical context).

7 The survival of a mural in both senses of the term is addressed by Peter Larocque in “The Peripatetic Journey of Miller Brittain’s The Place of Healing in the Transformation from War to Peace.” Brittain’s mural, unveiled in 1954, was, like the Ross mural, a war memorial that depicted the horror of war and the promise of peace, with modern medicine depicted metaphorically to represent the healing that was required for the world to be transformed from the former to the latter state (see Figure 1 in Laroque’s forum contribution, p. 118). This narrative and metaphor were entirely appropriate to the mural’s original setting, a hospital for war veterans, but as Larocque, curator at the New Brunswick Museum (NBM), explains, Brittain’s mural, like Ross’s, has had a troubled history. Brittain’s mural was moved from its original setting to, first, a retirement home and, second, the Saint John Regional Hospital. There it attracted complaints from those who objected to what they perceived as disturbing subject matter. At one point, hospital employees circulated a petition calling for the mural’s removal. Now the mural has potentially found a permanent home in the NBM and Larocque explains how the work connects in its theme and in some of its subject matter to other works in Brittain’s oeuvre in the museum’s collection – particularly to the enormous preparatory drawings (called, for murals, “cartoons”) that Brittain had created for a previous mural project at the Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital in the early 1940s. The museum, as Larocque suggests, may be an appropriate venue for learning about the mural, its history, and the context of its creation: this kind of appreciation, the petition would lead one to conclude, was more difficult to achieve in the lobby of a busy hospital.

8 While Brittain never had opportunity to realize his mural on the walls of the Tuberculosis Hospital, the drawings themselves are remarkable works of art. They have been called the most important social realist work ever produced in Canada,12 but because the images are unwieldy and fragile they have only very rarely been seen by the public, art historians, or even NBM staff. Among those endeavouring to make these works more accessible is Claire Titus, the NBM’s conservator, who describes the ongoing efforts in “Miller Brittain’s Mural Cartoons for the Saint John Tuberculosis Hospital: From Creation to Conservation.” Titus explains how the 2006 experience of seeing the cartoons unrolled for the first time in more than 20 years provided a team at the NBM with both inspiration and sufficient resolve to see what has been a long and challenging conservation project through to completion. Two important aspects of this project stand out in Titus’s paper. First, the willingness of the NBM team to collaborate with other institutions and to cast a wide net in its efforts to marshal the resources required for such a major undertaking is an example worth emulating. Second, Titus describes the remarkable way in which the conservation of the cartoons became, in themselves, a public exhibition. This effort to make open and accessible the processes in the museum that are ordinarily “behind the scenes” both provided educational opportunities and, undoubtedly, helped to increase public interest in and support for the project.

9 Alex Colville’s murals in Sackville have also faced – and continue to face – challenges in ensuring their preservation, as Gemey Kelly, curator at the Owens Art Gallery at Mount Allison, explains in “Alex Colville’s Trajectory as a Muralist.” The mural Colville executed as a student for the Sackville railway station has not survived (see Figure 3 in Kelly’s forum contribution, p. 140) – but Mount Allison University has gone to considerable lengths to preserve the two murals Colville executed on campus. This has been difficult, Kelly explains, because The History of Mount Allison (1948) and Athletes (1960) (see figures 1 and 2 in Kelly’s forum contribution, pp. 137, 140) are “in environments which have neither temperature nor humidity controls, and which, until recently, offered no security measures for the protection and well being” of the murals. Kelly describes the university as a “custodian” of these major works by an artist of considerable national and international significance: the responsibility for caring for the murals has become an institutional priority (see Kelly’s forum contribution, pp. 139, 142).

10 Kelly shows the connections between Colville’s murals and his intellectual and artistic trajectory in the post-war decades. Colville is a much-studied artist but, as Kelly notes, his efforts in mural painting have attracted little scholarly attention.13 This is a point worth considering in relation to other Canadian artists who created murals but who are much better known for their work as easel painters. I would speculate that there is a connection between this relative neglect and the economy of an art market in which murals are not ordinarily acquired by either collectors or galleries. The relationship between market and social value (and values) is a pertinent one in considering the history of “modern” mural painting: this was a form that for some in the Maritimes and elsewhere stood for a more democratic art and a more democratic culture.14 Is the idea that murals were an art of “the people” as opposed to an art for elites and connoisseurs a part of New Brunswick’s mural legacy?

11 Reflecting on this and other questions, Andrew Nurse of Mount Allison concludes this forum as he closed the symposium, drawing together ideas raised in the presented papers.15 Nurse, who has researched and written extensively on the relationship between art and society in Canada, highlights four key common themes: humanism (as the underlying philosophy motivating muralists in this period and as an idea of continued relevance in efforts to preserve the murals), interdisciplinarity as a profitable strategy for researching this kind of art, history as a process of forgetting as well as remembering, and the contextual and shifting meaning(s) of art in public spaces. Nurse also applauded the combination of international and local perspectives at the symposium. As he put it: “The story of New Brunswick’s muralists is a story of mobility and influences, of artistic ideals, styles, and perspectives that move across borders but are also, then, localized in place to create public artistic expressions” (see Nurse’s forum contribution, p. 143).

12 New Brunswick’s “modern” murals are, indeed, a legacy – one that was for many years almost forgotten. Preserving or in some cases restoring an artistic and intellectual inheritance of this kind has required (and does and will continue to require) substantial investments of time and money. What is the return on this investment? What is it worth to have the opportunity to consider, in retrospect, the vibrant and modern rural community that Pegi Nicol painted for the inspiration of Woodstock students in 1941 or to see and imagine the way Fred Ross and the students of FHS, or Miller Brittain and the DVA hospital residents, wanted the sacrifices of the Second World War to be remembered? What is it worth to contemplate how living in a city like Saint John in the 1930s led Miller Brittain to think about tuberculosis as a metaphor for a sick society that needed curing or to read Colville’s Athletes as an expression of his existentialism? What is value of learning what these murals meant then and of considering what they mean now? At what cost do we hold on to these artifacts of memory and at what cost do we neglect them? The papers compiled here suggest that a community of scholars, professionals, and enthusiasts believe the price demanded of this legacy is well worth paying. Their efforts help ensure that present and future generations of New Brunswickers will be given opportunity to contemplate these murals anew, to glimpse in them visions of another time, and to consider what aspects of these visions remain relevant today and to tomorrow.

KIRK NIERGARTH