Articles

Outport “Girls in Service”:

Newfoundland in the 1920s and 1930s

Interviews with former domestic servants as well as published memoirs provide a glimpse into the backgrounds, work lives, and migration patterns of young Newfoundland women who worked in service in St. John’s and smaller communities during the 1920s and 1930s. Migration from outport communities into domestic service work was a common experience for young women with few other options. “Girls in service” found positions not only in the homes of the wealthy but also in middle class and some skilled working class households. Domestics reported a sense of “difference” from their employers and engaged in a variety of strategies to resist exploitation.

À partir d’entrevues réalisées auprès d’anciennes employées domestiques ainsi que de mémoires publiés, cet article donne une idée des origines, de la vie active et des caractéristiques de migration de jeunes Terre-Neuviennes qui furent en service à St. John’s et dans de plus petites localités pendant les années 1920 et 1930. Chez les jeunes femmes de petits villages isolés, qui avaient peu d’autres options, c’était une expérience courante de devoir migrer pour s’engager comme domestiques. Les « filles engagées » trouvaient du travail non seulement dans les maisons des bien nantis, mais aussi dans des maisons de classe moyenne ou chez des travailleurs spécialisés. Les domestiques rapportèrent que leur employeur leur faisait sentir une « différence » entre eux et s’engagèrent dans diverses stratégies pour résister à l’exploitation.

1 “I CAN’T THINK OF ANYTHING [THE MAIDS] . . . DIDN’T DO. They got the coal, cleaned and washed and got the big copper pot boiling to wash the sheets with lye . . . . They had a regular routine for the housekeeping and cooking . . . . I was 5, 6, 7, 8; they were probably 17, 18, 19 but they seemed adult. They stayed for years, some of them, and usually left to get married.” So recalled Janet Story, a St. John’s nurse and nursing archivist, of her childhood years during the interwar era. Janet Kelly, a prominent city businesswoman, remembered that “almost everybody had maids. We did when I was a young kid. My father worked in St. Mary’s Bay, so we had a source, people who knew the family and would trust us with a young girl coming to St. John’s. It was not just the well-off had maids,” Kelly continued. “The middle class, if they could manage it at all, had a maid, because they weren’t paid much . . . . It was an opportunity for a young woman to get into St. John’s. It was one less mouth for a mother and father to feed.”1 While it was more difficult to find maids during and after the Second World War, as more opportunities for women’s paid labour emerged, a smaller stream of young women migrating from the outports for domestic work continued into the second half of the century.

2 These reminiscences tell part of the story of girls in service during the economically difficult decades of the 1920s and 1930s. They were young, rural migrants, and many of them came to the capital city of St. John’s for work; some went further afield to Canada or the United States.2 It was not uncommon for outport girls to leave school in order to make a contribution to the family economy. Some were able to send home money or goods, but for those who could not their employment still mattered as it meant one less person to feed. Migration and out-migration for work have been familiar patterns on the island of Newfoundland and in Atlantic Canada generally since the late 19th century. While men historically left Newfoundland to find work in places such as industrial Cape Breton, women have migrated in search of paid domestic work – one of the few occupations open to rural women seeking to help their families or perhaps widen their horizons.3

3 The last decade has produced a wealth of scholarship on women’s migration and work patterns, with some scholars focusing particularly on transnational migration patterns of domestic workers (most often from developing countries). In an age of increasing globalization, growing numbers of female migrants of colour are working in western industrialized countries as domestics – taking jobs that women of the host country do not fill.4 This emphasis on the transnational has tended to overshadow older patterns of rural to urban migration as well as intra-regional migrations that have been so important in Atlantic Canada. Recent historical scholarship on household workers has also opened up new ways of looking at domestic labour, emphasizing the middle-class home as a workplace in spite of its definition as “private” space and thus providing the possibility of seeing the home as a place of class conflict. Vanessa May’s study of domestics in the United States highlights the “servant problem” as a form of class conflict that involved “skirmishes over wages, hours and workers’ personal autonomy.” Networks formed by domestics (often immigrants) assisted them with jobs and higher wages as well as helping to define what was acceptable work for domestics. May reminds us that domestics were not merely exploited but could insist on dignity and respect, engaging in a variety of strategies such as using networks to find better jobs, resisting certain forms of labour, appealing to the courts, or quitting without notice.5

4 Such strategies of resistance and examples of agency in negotiating their work lives can be found among Newfoundland domestics, many of whom moved from the outports to larger centres such as St. John’s to find work. This article examines outport women’s paid work patterns in a time and an economy that provided few opportunities for women to earn a living – the economically depressed decades of the 1920s and 1930s. Such a study builds on other scholars’ work while contributing to a nuanced portrait of domestic service in a particular locale and time frame, thus contributing to several fields of historical study: women’s history, labour history, and, in particular, the social history of Newfoundland. While the 1930s are often the focus of economic study because of the widespread Depression, in Newfoundland the 1920s also presented severe challenges in an economy based largely on resource extraction; fishing was the major economic driver, supplemented by farming, trapping, and logging. The recession that followed the First World War not only saw a drop in salt fish prices but also additional financial difficulties resulting from a war debt of about $35 million and an annual railway debt payment of $1.3 million.6 There were numerous attempts to diversify Newfoundland’s economy, as discussed by the economic historian David Alexander; he observed that in its quest for foreign investment, the country failed to provide for “Newfoundland equity participation, either public or private.” In his view, “Newfoundland had progressed from a domestically owned one-product export economy to a substantially foreign-owned three-product export economy, for in 1929-30 some 98 per cent of exports were accounted for by fish, forest, and mineral products.”7

5 There were, for example, several foreign-owned industrial enclaves outside of St. John’s, such as the pulp and paper mills in Corner Brook and Grand Falls, that enjoyed some success. Neil White’s recent book, Company Towns: Corporate Order and Community, delineates the development of the mill town in Corner Brook and the succession of foreign companies that built the industry and the town. Both Grand Falls and Corner Brook employed men in the interwar years, a time when traditional strategies of survival such as outmigration were interrupted by the dire economic times. For women in these towns and surrounding communities, domestic service and working in the retail sector provided the most common forms of paid labour. The onset of the Second World War meant increased prosperity for these industrial towns as the demand for pulp and paper grew. In St. John’s the presence of Allied soldiers and, notably, the building of the US military base at Fort Pepperrell markedly changed the city, providing more economic opportunities for both men and women who built and serviced the base.8 Women working as domestics in the capital during the war could command much higher wages than before; domestics, according to Steven High, could now earn $30 per month instead of the previous going rate of $10, thus making it difficult for some families to keep a domestic.9

6 As well as drawing upon the limited number of existing Canadian studies of domestic service and available newspapers, theses, and memoirs, this article is also based on a series of interviews conducted in the 1990s with 21 former domestics. Most of the interviewees originated from small outports on Conception Bay or from the Southern Shore of Newfoundland, south of St. John’s. Those from the Southern Shore reflected a population that had a majority population of Irish Catholics with an admixture of with English Protestants, while the Conception Bay South area was largely English Protestant. Beginning with the context for domestic service in Canada and Newfoundland, the article examines the job market for girls in service through newspaper advertisements and by exploring the circumstances that help to explain why young women went into service. Following this context, a demographic portrait of the interviewees suggests some of the common patterns among these young women in terms of age, religion, education, father’s occupation, and family characteristics. Work experience and living conditions in service range from being treated like a member of the family to instances of abuse. Pay rates, job mobility, and the interviewees’ assessments of their experiences are also discussed. Almost all of these women, as the quotation at the beginning of the article suggests, were eventually married, often to men from their home or neighbouring communities. And most did not continue or return to service jobs after marriage – although one-third of them did work after marriage, sometimes because of a husband’s illness or death. In a sense, service became part of the life cycle for many outport women who left the small communities of their childhood and youth for places in more prosperous and socially stratified communities such as St. John’s.10

7 Thus, a central argument is made that the middle class in St. John’s, and not just elite families, offered employment to outport young women who worked for very cheap wages and who sometimes had kinship ties or other links to the city. Indeed, the employment of domestic labour stretched remarkably deep into the layers of social stratification in comparison with urban areas elsewhere that have been studied. In Boston, for instance, Betsy Beattie notes that around the First World War and later “live-in servants were becoming concentrated in the households of the wealthy while middle-class families were less frequently willing, or able, to pay for round-the-clock help.”11 In some cases the household was a place of class conflict and cultural clash as outport domestics tried to find remunerative employment to help themselves and their families in a precarious economic time during the 1920s and 1930s. Girls in service, however, were not just “victims”; as with other seemingly powerless women, but in ways that distinctively reflected the depth of their pervasiveness in non-elite households, they demonstrated agency when they quit without notice, violated curfew, refused heavy work beyond their strength, changed jobs frequently, confronted their employers about working conditions, or took their employers to court for unpaid wages. This is not to deny that domestics also suffered from unemployment, homelessness, and abuse nor to deny that they were the subjects of police and judicial attention when they wandered the streets, broke the law, or appeared drunk in public. Yet for outport women, the opportunity to work for wages using their domestic skills provided a strong inducement to migrate to a community such as St. John’s. As Katrina Srigley reminds us, historical context is important and an examination of the individual and the local helps us to understand the complex results of systems of social power while still recognizing agency at the individual level.12

8 Canadian historian Eric Sager, among others, has noted the decline of domestic service in Canada during the 20th century. Domestic service attracted more women than any other sector in the early part of the century – 42 per cent of women working in paid occupations in 1901 – but by the early 1930s service accounted for 33.8 per cent of working women.13 While Marilyn Barber’s research on British immigrant domestics in Canada explored employers’ preference for women from the UK, it also suggested that only those who had no other choice entered service.14 According to Sager, “Here was a job that quickly repelled most who entered it.” Sager’s recent research using the census demonstrates that the decline in service began in the 1890s, and that the earnings of female domestic servants fell below the average annual earnings for women employees in 1901. When estimates are made of the costs of room and board, however, their earnings compare favourably with those of other women workers. In addition, Sager points out that servants, unlike many occupations, were employed for an average of 11 months in the year. Within two decades, however, room and board did not compensate for the disparity with the earnings of other workers. By 1921, “the real earnings of domestic servants had not increased over the previous 20 years.” Sager also reinforces the finding that by 1901 most domestics were Canadian-born women of British or French Canadian descent rather than immigrants. Most were literate young women who had gone to school, and about a third were urbanites. Employers were more likely to be merchants, professionals, or government officials than the white collar workers or skilled artisans of the 19th century, and thus class differences had become more pronounced. Economic changes also gave women more occupational choices and they increasingly steered away from domestic service, preferring better pay and rejecting low-status service work.15

9 In Newfoundland, while St. John’s as the capital and largest city on the island attracted the largest numbers of migrants, some women migrated from outports to the smaller industrial centres. Ingrid Botting’s 2000 thesis explored domestic service in the industrial town of Grand Falls in central Newfoundland. The construction of a pulp and paper mill by the British-owned Anglo-Newfoundland Development Co. in 1909 changed the area by drawing in not only male migrant labour but also young women domestics to work in the homes of mill workers as well as in the homes of managers. Similar to the pattern in St. John’s, domestics worked not only in well-off households but also in those of skilled workers and some white collar employees. In the communities surrounding Grand Falls, both male and female migrants left fishing communities where the fishery was in trouble. As Botting’s informants noted, mill workers often went to their home communities to find young girls, some of them relatives, to work in their households. By contrast, in more elite/managerial households, domestics were recruited through advertisements. Getting a “Grand Falls job” meant steadier work and higher wages.16

10 Research on women’s work in St. John’s by Nancy Forestell revealed that domestic service accounted for a significant proportion of women’s labour force participation. Using the Newfoundland censuses of 1921 and 1935, Forestell sampled every third household where a woman worked for wages and found that domestic service employed 39 per cent of women in 1921 (compared with 25.8 per cent in Canada), which rose to almost 42 per cent in 1935 during the Depression (33.8 per cent in Canada in the 1931 census).17 Compared with the Canadian census findings, it is clear that domestic service was significantly more important in Newfoundland in the twenties and thirties. Limited urbanization and industrialization, and a much narrower economic base in the latter, severely circumscribed economic opportunities for employable women. Young, single women aged 15 to 24 were the largest age group employed, partly because of their family’s financial need but also because of an absence of compulsory schooling and child labour laws until 1942 and 1944 respectively. The city’s male labour force worked in the fishery and other waterfront activities as well as in tanneries, an iron foundry, breweries, and carriage, nail, and furniture factories; many, though, were thrown out of work in the early 1920s as factories and other businesses closed or reduced their labour force. Some women found work in the clothing industry as well as in boot and shoe production and in cordage, tobacco, and confectionery factories, but the largest number worked as domestics during the 1920s and 1930s. The Second World War provided more opportunities for women’s paid labour, and the census of 1945 confirmed the decline of service as an occupation for women.18 Moira Baird Bowring, who was from a privileged merchant family and who married into another prominent merchant family, confirmed the shortage of local women willing to work in service in 1950. In a letter to her “darling Mother,” Bowring agreed with the suggestion that a German maid might be the answer as “it is absolutely hopeless to get a local one. They are so independent and quite a few of our friends living in town are without maids now, so I know I would have no hope.”19

11 The pre-war job market for domestics, however, had clearly favoured the employer. Advertisements in the St. John’s Evening Telegram in the 1930s were very specific in their requests for references or specific skills such as “plain cooking,” ability to make bread, or to do child care. Age and marital status were crucial factors in negotiating the terms of employment, and thus employer advertisements usually specified whether they wanted a young girl (sometimes “outport girls preferred”), a middle-aged woman, or a widow. In December 1930, for example, Mrs. Hubert Hutton advertised for a “nurse girl, about 14 or 16 years, of age, to take care of baby.” Employers also requested maids for temporary or seasonal work. Mrs. G. Lowe, for example advertised for a “reliable girl to cook for four fishermen for summer months; outport girl preferred.” In 1936 one advertisement specified “A housekeeper to go to an outport. Must be fond of children. No person under 30 years of age need apply. Applicant must be able to milk cows . . . .” In some instances, maids were sought to fill jobs elsewhere – usually in other parts of the island, the US, or Canada. In December 1932 an advertisement appeared wanting “a maid to proceed to Montreal; must be fond of children; references required.” And in some cases, employers specified that they had a religious preference: “Wanted, an experienced maid, outport girl preferred (United Church or Church of England); apply with references to 5 Cabot St.” And occasionally men would advertise for wives: “Wanted, a wife between the age of 45 and 60 (Methodist preferred); have a good home of my own.”20

12 Employees advertising their services also designated their age and status, and some advertised their years of experience or special training. For example, in January 1930 an “Experienced lady” wanted a position as “nursery governess, companion or attendant to invalid or elderly person or as an overseeing housekeeper. Can furnish excellent references.” Occasionally a graduate nurse would advertise looking for a position as a lady’s companion, care giver to an invalid, or as a child minder. Widows advertised their availability for domestic work quite frequently, some clearly in economic straits such as the young widow who wanted to work by the day, or take in washing and “will accept either money or clothing” as payment. Another widow with two children wanted employment in an office as she had “some knowledge of typing and book keeping and general office work. Would accept small salary.”21

13 Wages were seldom mentioned in the advertisements and where specified they generally ranged from $5 to $20 per month. Some employers promised good wages in their advertisements: “Wanted by 1 June, Nursemaid to care for one child, ten months old; no other duties; good wages will be paid to a competent girl, who must have references.” The Domestic Help Bureau in 1930 advertised for 10 general maids and cooks, with wages from $10 to $15 per month. This same bureau advertised in September, promising wages of $10 to $30 per month for older, more experienced housekeepers. Advertisements for maids to go to the US promised higher wages; an ad for a maid to go to Boston promised “Wages $10.00 per week to right party,” four times the $10 per month often offered in St. John’s. Eight years later, one advertisement looked for a “good reliable outport girl, who can cook, not under 30 years of age, to go to Newfoundland family in Boston. Wages $10.00/week; references required.” Wages varied, however, and even in 1939 some employers in St. John’s advertised wages as little as $7 or $8 per month. And in a few cases the amount was as little as $4 or $5 per month.22 Wages in small communities could be very low or in kind. ERT (born 1934) reported her experience in the 1940s working during a summer for a fishing family; although she was promised $10 per month, she only got room and board and some clothing. Stella Ryan recounted her days in service at Pilley’s Island on the northeast coast in the 1930s when she was between 14 and 18 years old. She reported being paid nothing, or sometimes with hand-me-downs – a point also made by Eva Abbott, who worked in service on the west coast of Newfoundland for ten years in the 1920s and 1930s.23

14 Low wages in St. John’s contributed to the desperation of poorly paid domestics as revealed in the reports of the Magistrate’s Court in the Evening Telegram, which showed domestics resorting to theft to make ends meet. Others used the court to claim unpaid wages or to press charges of rape or assault. In January 1930, for example, a 17-year-old girl from Carbonear was convicted of stealing clothing and cash from a boarding house. Since this was not her first offense she was sentenced to three months imprisonment. In a 1936 case a domestic who pleaded guilty to theft of $12 was put under a bond of $25 and ordered to “make good the amount stolen.” Another method of making money was to sell liquor, as was the case in January 1930 when a housekeeper was charged with selling liquor in a “house for immoral purposes.” The court could also provide an arena for a domestic to contest her wages. In the case reported on 27 February 1931, a domestic from Gander Bay was arrested for stealing a coat and sweater from her mistress who had refused to pay her two weeks’ wages. Although the judge chastised the domestic for taking the goods, he also ruled that she could claim a month’s wages. In another case in 1933, a domestic who left her mistress without giving notice sued for a month’s wages of $7 and a dollar owed on a previous month. The court awarded the domestic one dollar but disallowed the claim for the month’s wages “as there was an agreement between the parties about notice to quit.”24

15 Assaults on domestics, though not reported frequently, could be quite violent and were sometimes fuelled by alcohol as in the case with a St. John’s man who insisted on accompanying a young maid home; he suddenly “caught her by the throat and swore he would take her life.” A witness detected the influence of liquor and, while the accused could not account for his action, the judge said drunkenness “did not excuse his blackguardly conduct” and he was sentenced to two months imprisonment. One Hubert Rice was arrested for an assault on a St. John’s domestic in October 1932, and a man who was sentenced for an assault on another domestic that same month was found mentally unsound and sent to the Hospital for Mental and Nervous Diseases. Another domestic, in Corner Brook, was so brutally assaulted that she was “confined to bed for three days” and needed a doctor.25

16 Magistrate’s court cases also demonstrated the danger faced by some domestics, who were objects of sexual assault or rape. One case in July 1930 involved a rape of a domestic by a man who gave her a false name. The wily domestic arranged to meet the man again and the police were able to catch him. Another case earlier in 1930 involved an indecent assault on a young outport girl in service, resulting in conviction and a five-dollar fine for the defendant. In one unfortunate case involving an adolescent in 1934 a 31-year-old businessman was charged under the Criminal Law Amendment Act for offences against his 15-year-old domestic, who gave birth to a child. No further reference was found to this case and its ultimate outcome. Given the nature of these charges, it is likely that such assaults were underreported unless charges resulted.26 Unemployed, vagrant maids were often sent to the police lockup or to a probation officer because they had nowhere to go. As the court reporter noted in 1939 of a 22-year-old domestic: “She has frequently been given shelter at the lockup and appears to be one of the victims of circumstances for which social services has no provision.” A few were so desperate that they threatened suicide: “A 29 year old domestic who had no home was taken in at the lockup for safekeeping was discharged. She threatened to drown herself and a few minutes after the release went to Baird’s wharf with the evident intention of putting her threat into effect. A police constable saw her and brought her to the lockup.” In 1939 the newspaper reported the apparent suicide of an 18-year-old domestic who had lately left the employment of a veterinary surgeon. Whether her unemployment caused her despair is not known.27

17 Interviews with 21 former domestics who were born in one of Newfoundland’s many outports confirm some of the trends discussed so far and they provide a more intimate portrait of girls in service in the interwar period. These interviews were carried out by an older and experienced woman interviewer in the interviewees’ homes and occasionally in a seniors’ home. The interviews are silent, however, on some aspects of servants’ experiences; for example, the interviews do not refer to criminal behaviour and rarely allude to sexual misbehaviour on the part of employers. Given the age of the women interviewed (15 of the 21 were 75 or older), it is not surprising that some could not recall information or gave contradictory information. That many of the women looked back on the experience positively may be explained by their hesitancy to be critical of others or of their own life experiences. With few exceptions their lives were hard and their pay low. The interviews do provide, however, instances of resistance and conflict that reveal domestics’ awareness of their different class status and their struggle for dignity and respect, a trend noted by Vanessa May.

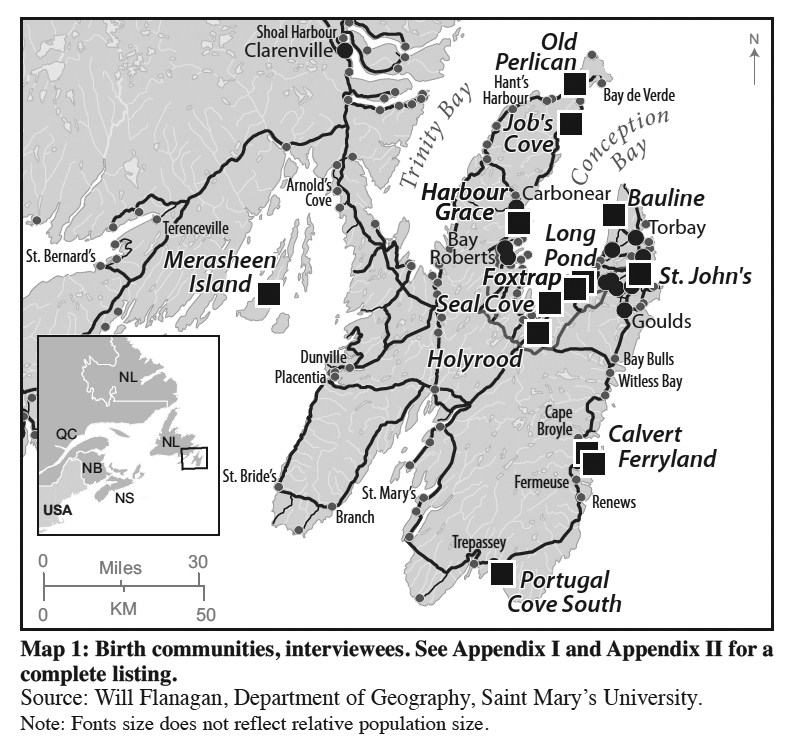

18 Where did these women come from and what can be learned from their testimony? From the interviews we can observe some geographic and demographic patterns. The 21 interviewees came from communities surrounding St. John’s, mostly from the Southern Shore south of the capital city (9) and from outports on Conception Bay (9).28 At the time of their interviews in the 1990s, however, 13 of 21 women lived on the Southern Shore, 3 in Conception Bay communities, and 5 in St. John’s, thus demonstrating the pattern of wives moving to their husband’s community. Bored with school, living in poverty, and/or lacking other paying work, many young outport women – often at their parents’ urging – pursued jobs in service. Most of these women were 14 to 16 years old when they took their first jobs (13 of the 21), 5 were 17 years old, and only 3 were under 14 years old. The majority went into service during the 1920s and 1930s, decades of economic difficulty. Published narratives of 8 other domestics confirm a similar age profile for domestics, and 7 of the 8 also worked in service in the 1920s and 1930s.29 Among the interviewees, 10 women came from families with 4 to 7 siblings while 7 (or one-third) came from families of 8 or more children.30 In terms of birth order, just under half were the oldest or second oldest of the siblings who went to work in service – thus suggesting that older siblings may have experienced significant pressure to help out the family. Since two-thirds went into service aged 14-16, they would have had limited education with few finishing high school. More than half were Catholic (11) while 5 identified as Anglican and 5 were of unknown religious affiliation (if any). In terms of education, for the 17 interviewees who provided this information, 7 had Grade 4 or less, 1 had attended up to Grade 7, and 9 reported school attendance for grades 8 to 11.31 Not surprisingly, the majority reported their father’s occupation as fisherman and most of these families also had gardens in which they grew potatoes, carrots, turnips, cabbage, and other crops.32 Some fathers were fishermen for only parts of their lives and 7 worked in industrial occupations such as iron worker, mine-related labourer, construction worker, boiler man, cement worker; 1 worked on dredges. A few worked as craftsmen (farrier, carpenter), and it was not uncommon for the male head of household to work several occupations such as fishing in the summer and into the fall and logging in winter.

Display large image of Figure 1Note: Fonts size does not reflect relative population size.

Display large image of Figure 1Note: Fonts size does not reflect relative population size.

19 When examining the 8 published narratives available, as well as the 21 interviews, the patterns are congruent. These 29 women with experience as domestics tended to be in their mid-teens when they started working, to have limited educational opportunities, and to be from communities dependent on fishing, farming, logging and occasionally industrial work. Most married in their 20s, a handful as early as 17 to 19.33 A number of these women had sisters or other relatives also in service; some had friends who were domestics. Having a relative or friend in service provided a network that helped with finding jobs and learning what to expect in terms of the work required and the wages paid. These networks also assisted domestics who were dissatisfied with their employer to find a new position. Two- thirds of the interviewees had contact with other domestics while in service, and many of them got together regularly on afternoons or evenings off. AS (born 1913), for example, had a sister in service and remembered meeting with other girls in Bowring Park in the west end of the city. Going for walks with other servants provided a cheap form of leisure, as did window-shopping.

20 MB (born 1920) remembered discussions among her counterparts, particularly when problems occurred; dissatisfied domestics demonstrated agency by looking for a new place, sometimes through the plentiful newspaper advertisements or through their networks. VT (born 1931) remembered hearing complaints from other domestics about their treatment or about mistresses themselves, but she cautioned that the relationship between mistress and servant was “a two-way street.” Domestics would compare wages, according to MD (born 1917), and some only made $3 or $5 per month. BG (born 1918) remembered “there was a lot of girls like myself – they all had to leave young to help out home.” She also recalled that they were “hard times but not bad times.” MJ (born 1924) noted that service was a very common experience for outport girls because there were few other choices. Her first job doing babysitting and housework at 15 earned her $5 a month. In retrospect she said “I’m not sorry that I went [into service]. Sometimes I wished that I . . . many times, I suppose, I wish that I had gone to school, but apart from that, I’m not sorry I went out early and all that.” BM (born 1925), on the other hand, regretted going into service as she had wanted to be a nurse, a theme that also appears in Janet Winsor’s memoir of her 20 years in service before becoming a nurse.34 RP (born 1915), who had two sisters in service and was acquainted with others, and in referring generally to the employers, noted “they could pay, yes, whatever they wanted.” ER (born 1912) also had a sister in service, and she was aware of the much higher wage earned by MS (born 1910), a domestic also from her community. MG (born 1913) recalled that her sister worked for a St. John’s widow with three children and who was a clerk in government, but the sister was never paid for her six years of service. Thus wages could vary quite widely among those employed as domestics.

21 Wages were not the only subject of complaints. DW (born 1916) commented that conversations among servants revealed that some were asked to do work beyond their strength. Speaking of other domestics’ experiences, DW recalled “They were demanded to do things that was impossible for them to do, because they never had the strength, like lifting beds around and things like that.” Speaking of her own situation DW spoke more positively, noting “I learned to tolerate, where I wouldn’t maybe. And I also learned to speak up for myself. Because if you don’t, you’re walked over.” Some women reported poor circumstances where the food was locked up, the employers restricting time off, or them looking down on their domestics. Speaking of her 12 years of service, AS said she did not mind the work but also did not look back on those years with any joy: “The best of my youth went there.”

22 Having a relative or friends in service nearby helped to combat loneliness, but this did not totally dissipate homesickness among young domestics. Janet Winsor remembered crying herself to sleep every night for the first year of her employment even though her employers were kind and supportive: “The thought of my family expecting me to earn my own living prevented me from giving in.” ERT’s first job at 12 years of age was in the fishing community of Port de Grave watching three children and doing housework for the summer while the parents worked in the fishery; despite her homesickness she never confided it to her father, who visited her regularly. Stella Ryan similarly hid her loneliness from her father, who carried the mail to Pilley’s Island where she worked: “I was too proud to tell him how much I wanted to go home.” Several interviewees mentioned Christmas as a difficult time to be away from family. MG got a position in St. John’s through a woman with ties to her community and for six years never spent Christmas at home. Her friend, KR (born 1910), also from Bauline on Conception Bay, remembered her first Christmas in the city as very difficult and that she spent a lot of time in church as a result.35

23 Although some domestics tended to remember their years in service in a positive light, there were many critical comments about how they were treated by employers. A short published reminiscence in 2007 by Peggy Johnson, the daughter of a domestic, noted that her mother was forced to sleep in “an unfinished basement between a coal furnace and the coals bins” in her first job in St. John’s. As Johnson recalled, her mother was young and “soon discovered that [while] the family members were not necessarily unkind, they were simply insensitive to the human needs of their indentured servant.”36 Interviewees were asked about their relationship to the employer’s family through a series of questions – and their answers revealed a sense of “difference.” Servants were generally from a different class from that of their urban employers, who ranged from a few skilled workers to members of the elite. As Linda Cullum has noted in her study of domestics in St. John’s, domestics made it possible for middle and upper class women to engage in social reform and other public activities. Servants also made possible the reproduction of family life and social activities; their work was central to daily life and to a family’s social standing.37 The 21 interviewees commented on the differences they observed between domestics and their employers. Many noted working conditions that separated them from the employer’s family or demonstrated the authority of the employer, including the curfews and limited hours for socializing with other girls in service. In some cases domestics reported that their employers would not let them take a holiday. A few mentioned uniforms paid for out of their wages. VC (born 1921), who worked on the fashionable Queen’s Road in St. John’s as a cook and server, remembered wearing a uniform for work; in addition, she had to share her room with one other domestic. Writer Helen Porter recalled returning a book to a friend’s house and being greeted by a domestic who “wore a stiff printed pink dress under a starched white apron and the little white cap on her neat head stood off like a decoration on a cake.” Uniforms clearly pronounced the status of the wearer, emphasizing the difference between mistress and maid, and the Evening Telegram often carried advertisements for uniforms.38

24 There were also variations in comments about spatial divisions, coping with unfamiliar or onerous tasks, strange food, and the amount of entertaining by employers. ER, for example, complained about her employer’s three or four nights a week of entertaining when she worked in St. John’s in the late 1920s. Despite late nights of cleaning up, domestics were expected to be on the job early the next morning – thus demonstrating their important role in maintaining middle class standards.39 MJ, who worked on prosperous Maxse Street in St. John’s, was clearly aware of the spatial division between servants in the kitchen and the family in the dining room, a commonly noted experience; in addition, she had to share a room with the cook. She also remembered that the lady of the house was “into many things, you know she wasn’t home. Very seldom was she home a day, put it that way.” While MJ had charge of the couple’s six boys and took care of their needs, she also helped the cook with the washing up. AS remembered that some employers who were well-to-do looked down on their domestics and treated them badly. Referring to her conversations with other servants, AS noted that “some of their circumstances were much worse than mine . . . they didn’t get enough to eat or anything . . . they locked the food away from them and that . . . they were all starved, they didn’t have the money to buy it, see.”

25 MG related her situation during the 1930s, emphasizing the arduous labour involved. She worked for a family with two children, who lived in a three-storey house on Military Road in the salubrious area adjoining Bannerman Park. In this household she had to do heavy labour, while the woman of the house complained a lot, paid her late, and deducted half of her $8 per month salary for a uniform. She described this situation as a “nightmare for two and a half years.” She recalled the heavy work keeping the fires going: “And we had a hall stove, . . . and a fireplace up on the 2nd floor, grate, another fireplace in the dining room downstairs. So that was 2 fireplaces were going, plus the hall stove. So you had to carry the coal from the basement, clean the ashes from the grates every morning and sift the ashes when it cooled and put it out, take the cinders burnt [to put them back in the fireplace].” MG was forced to shovel two tons of coal, and also cooked, did the laundry and the ironing, waxed floors, made beds, and other chores. Her mistress kept strict control over the household: “I’d take the pail, like anyone, you’d put your duster and your cleaning stuff in it, to go upstairs to do the bathroom or the windows or whatever. And if I forgot something, she scolded me, for going up over the carpet the second time.” MG was not allowed to use the bathroom to wash; her employer “had a grey enamel pan on top of that [an orange crate] for a washpan. I wasn’t allowed to wash in the bathroom.” Although she got along with the husband and had a good relationship with the children, she was not allowed to have friends over and did not eat with the family. Food deprivation was a particular grievance. Describing her mistress as “mean,” MG recalled that she was not allowed to make tea or have snacks when she was hungry. As a result she lost weight. The mistress also waited up for her on her nights out. The last straw was an order to wash the ceiling on a hot July day, which MG refused; the wife threatened to refuse her a reference, but MG told her off: “It was the first time I answered . . . I said, I don’t need your reference . . . I have a place to go.” Quitting suddenly without notice was a means of resisting unreasonable demands and asserting a domestic’s individual worth. For MG another job in St. John’s in 1935-36 was also unpleasant, as the widower who headed the household terrified the rest of the family. In these two jobs MG felt abused, which led her to reflect negatively on her six years in service (1930-1936); as she commented, it took the best six years of her life. She did, however, also report several jobs where she was treated well and remained in touch with these families after she married in 1936.

26 RP also had mixed experiences in her five different domestic service jobs, the last three in St. John’s. Like MG, she left employment at her third job after six months because she felt like a stranger in their household. She also related that curfews were strictly enforced: “Oh, if you go out and come in a bit late, they’d get mad with you. You know, you’re supposed to be in half-past ten. If you go out, come in around 20 to 11 or 25, they didn’t like it. . . . And they’d let you know they were really mad about it.” The main reason she left this job, however, was that the children were “saucy” towards her: “Well, I’ll tell you, I didn’t like the children. I said that when I left.” Her next job in a businessman’s family on well-heeled Waterford Bridge Road lasted for a year, but was also unpleasant because the wife was stingy about meals and locked up the food: “She was very mean, though. She used to lock up all the food . . . she had a place down in the basement where she used to lock the food up.” Like MG, RP related that she was often cold and hungry: “I say, winter nights was cold . . . myself and the other girl used to put down the oven. Open the door to get warm, in the kitchen. She came in and caught us one night. Oh, she said everything to us.” The oven incident suggests that domestics found ways to circumvent difficult working conditions. Her final service experience was much better and after two years with this family she married in 1940 at the age of 26.

27 JH (born 1907) was the only one of the interviewees to spend her service time in the United States, among very wealthy employers. Her first job at 17 involved caring for two toddlers. Her employer urged her to work for the telephone company because she was literate, but she resisted because she would not have room and board with such a job.40 As she put it, she enjoyed being with the “grander bunch” of people because of her education and, unlike other Newfoundland domestics who spent their free time at Coney Island, she often stayed home on her days off to do crewel work and crocheting to make money. While she clearly felt superior to other domestics, she also could be feisty with employers if she felt they took advantage of her. When a doctor’s wife piled more and more work on her she left their employ and refused to reconsider when the doctor called to try to get her back. JH replied that she had not been appreciated enough to return. Her last job in service was as a companion to a rich widow, and when she married in 1936, her sister Madeleine took her place.

28 The most extreme case of abuse happened to MP (born 1915), whose mother and father died when she was very young; as the oldest child she was sent into service By the age of 11 or 12, she worked for a St. John’s family with five children where the father worked as a blue collar public servant. When the mother of this family died of TB in 1937, MP “raised the family for them” having promised the mother that she would take care of them. Her presence was essential to the day-to-day reproduction of this family’s life after the mother died. The husband was a drunk, and a violent man who beat her. According to MP, the mother also beat her and this treatment left her scarred and her sight diminished. Although at first she maintained hopes of being adopted by this family she suffered great cruelty including isolation, broken bones, confinement, and attempted molestation. Instead of being treated as a member of the family, MP was, in her words, “just a slave.” Eventually she ran away and was assisted by a woman who found her a place at a boarding house where the landlady treated her kindly. Some years later, at her third placement with a family where the husband was a boss on the docks, MP experienced some problems with his wife who was stingy with the food and who threatened to cut her wages. Despite her experience of poor treatment, she resisted the wife’s threats; she voted with her feet, competing successfully with eight other girls for a job on Military Road. Here she was treated as a member of the family and her employers were very sad when she left to get married in 1945 to a man who worked as a carpenter on the American base.

29 On the more positive side, some interviewees commented that they had learned skills such as how to set a table or how to interact with their employers and their visitors. MJ appreciated learning about the “better off,” while MD commented that she met lots of people in her role and that she learned how to get along with people. MG commented that she learned the value of an education for her children and how to be economical, although she also said she felt abused. Working in service helped RP grow up and prepared her for working in her own home as well as teaching her respect for the elderly. Service showed MS how different city life was. Although she learned a number of domestic skills in service, ERT confessed she had few good memories of that time. DW learned to be more tolerant but also to assert herself as a worker. By the end of her time as a servant working for the St. John’s elite, she felt that she was treated with more respect. Indeed, DW reported that she enjoyed asserting herself and figuring out people.

30 Despite positive comments from some domestics, it is striking that so many remarked on disdainful treatment, conflicts with employers, and examples of exploitation. Half of the women interviewed, for example, noted that they ate in the kitchen separate from their employers’ family, thus illustrating class distinctions. Some reported overt conflict with their mistresses over curfews, withholding of food, or permission to go home. A few quit their positions in protest against their treatment: IA (born 1906) quit when her employer lied about wages; MG left when her employer ordered her to perform heavy labour and threatened to withhold a reference; DW quit when refused time to go home; RP quit her third domestic position after six months because of conflict with the family; and Stella Ryan left her first job after six weeks and no pay. Despite the employer’s power over wages, working conditions, and references, some domestics insisted on fair treatment and respect.

31 Despite the evidence of discontent, girls in service left very little evidence that they considered unionizing. A single letter in the Evening Telegram in April 1938 by “A Maid” asked the editor “Isn’t it time they (housemaids) started a union for these unfortunate girls; they have the longest and hardest hours to work?” The author also noted that maids “are looked down upon as inferior to everyone else” and, though some had a good education, hard times often “compelled [them] to work for somebody who don’t know how to treat a girl, but makes them work all they can from seven in the morning until late at night for less than twenty cents a day.” The author underlined the need for “fair play” so that maids could be “treated as human beings and not machines.”41

32 In conclusion, without cost of living data it is difficult to estimate how these young women compare with those in Canada studied by Sager. But young rural or immigrant women in Canada often had more diverse employment opportunities if they migrated to urban areas, while almost all outport young women seeking employment and wages would have had service work as their most likely option. Unlike female migrants to New England or to Canada’s industrial towns and cities, young outport women had few opportunities for industrial employment. Outport women, in addition, were not immigrants from outside the island as was often the case in Canada, where there was a long association with immigrating servants coming from the British Isles, Scandinavia, and Western Europe.42 While Sager identified service as an employment of last resort, in Newfoundland outports it was the first and last option for most young women. These young women worked in a variety of households, ranging from those of the very wealthy business elites such as the Crosbies and the Hickmans to boarding house or restaurant owners to a few professionals and also some who worked in retail jobs and transportation. A lesser number of employers were fishing or farming families, and some were retired or elderly couples whose background is unknown. Thus it is not accurate to claim, as one recent publication does, that only the wealthy could afford to hire outport girls as domestics.43 As the interviews and opening quotations for this article demonstrate, families from middle class backgrounds and a few from the skilled working class also employed servants well into the 20th century because of domestics’ low wages. In contrast, the backgrounds of girls in service were more limited: two-thirds came from fishing families, with a sprinkling of fathers in industrial or artisanal occupations. Outport girls were often preferred, as the advertisements tell us, not only because of their cheap labour but also because they were hard workers, taught from an early age how to do basic domestic chores such as cooking, baking, cleaning, and child care. As the interviews and narratives demonstrate, the experiences of these women could vary quite significantly – changing with each new employment situation. Networks of relatives and friends in service could assist a domestic in finding or changing employment, particularly in problem situations. Although some women evaluated their overall experience in service positively, closer examination of the interviews and narratives reveals considerable recognition of class differences, examples of differential treatment, exploitation and outright conflict with employers, and events that demonstrated domestics’ agency during the 1920s and 1930s. As Vanessa May has reminded us, exploited domestics are not just victims; they used their networks to change employment and obtain higher wages or more personal autonomy. Maids engaged in “skirmishes” with mistresses about their work and working conditions, and some left their employment without notice to protest their treatment. May’s work demonstrates that the household can be viewed as a workplace where conflicts regularly occurred between maids and mistresses. Outport domestic servants in Newfoundland were certainly exploited and at times were subjected to abuse, but many of them demonstrated an awareness of class differences and some used strategies to resist exploitation and to insist on more respect and dignity for their work. Conditions would change during the Second World War as more opportunities opened up for non-domestic employment in the capital city, and domestics could claim higher wages both during the war and in the immediate post-war period.

Appendix I – Interviewees (including place of interview and date)

- IA, St. John’s, date missing [1994]

- BB, Calvert, 22 June 1994

- MT, Calvert, 8 July 1994

- VC, Cape Broyle, 9 August 1994

- MD, Seal Cove, 28 March 1994

- MG, Bauline, 7 June 1994

- BG, Renews, 5 July 1994

- JH, Holyrood, 13 April 1994

- MH, St. John’s, 6 May 1994

- MJ, Long Pond, 19 May 1994

- AL, St. John’s, 10 August 1994

- BM, Aquaforte, 9 August 1994

- RP, St. John’s, 29 April 1994

- MP, Fermeuse, 8 July 1994

- KR, St. John’s, 20 June 1994

- ER, Calvert, 22 June 1994

- M S, Calvert, 15 June 1994

- AS, Calvert, 14 June 1994

- ERT, Long Pond, 13 June 1994

- VT, Long Pond, 21 June 1994

- DW, Long Pond, 4 May 1994

Appendix II – Birthplaces of Interviewees

- Avalon Peninsula, Southern Shore: 9 (Calvert, 5; Ferryland, 2; Portugal Cove South, 2)

- Conception Bay South: 5 (Foxtrap, 2; Holyrood, 1; Long Pond, 1; Seal Cove, 1)

- Conception Bay: 4 (Bauline, 2; Harbour Grace, 1; Job’s Cove, 1)

- St. John’s: 1

- Placentia Bay: 1 (Merasheen Island)

- Trinity Bay: 1 (Old Perlican)