Articles

The Pursuit of Gentility in an Age of Revolution:

The Family of Jonathan Worrell

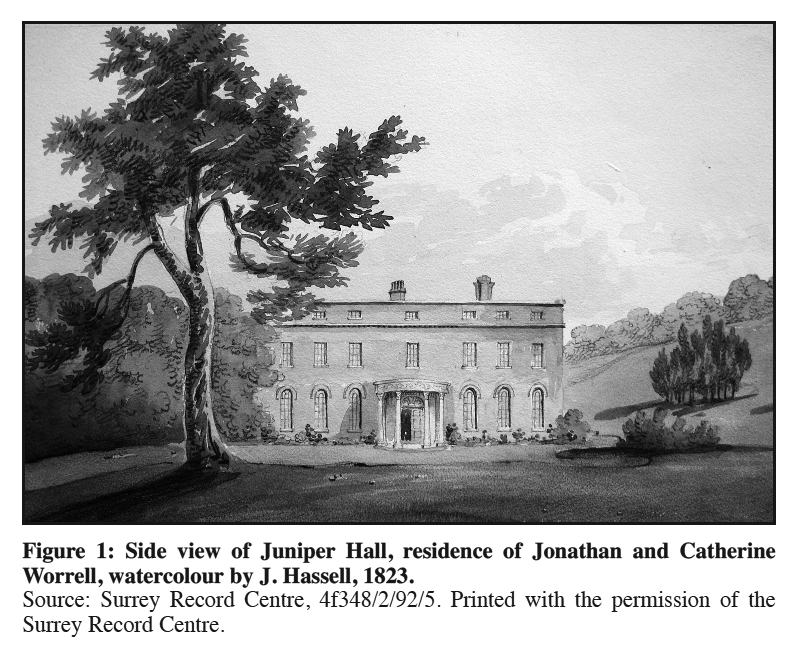

The Worrell family’s half century of connection with Prince Edward Island began in 1803, when Jonathan Worrell, a Barbadian plantation owner living in England, purchased 47,000 acres of land in Kings County. Jonathan’s son, Charles, moved to the Island and managed the estate for more than 40 years, doubling its size. Across these years, the Worrell family dealt with war in the transatlantic world, emancipation of the enslaved peoples who worked their sugar plantations, and demands for an escheat of large landholdings on the Island. This article considers the Worrells’ decision to invest in PEI within that broader context.

La relation d’un demi-siècle entre la famille Worrell et l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard s’amorça en 1803, lorsque Jonathan Worrell, propriétaire d’une plantation en Barbade qui vivait en Angleterre, fit l’acquisition de 47 000 acres de terre dans le comté de Kings. Charles, le fils de Jonathan, vint s’installer à l’Île et administra le domaine durant plus de 40 ans, doublant sa superficie. Au cours des années, la famille dut faire face à la guerre dans le monde transatlantique, à l’émancipation des esclaves qui travaillaient dans ses plantations de canne à sucre et aux demandes en faveur d’un escheat (une confiscation) de grandes propriétés foncières dans l’Île. Cet article examine la décision de Worrell d’investir à l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard dans cette perspective élargie.

1 THE WORRELL FAMILY NAME WAS ONCE WELL KNOWN on Prince Edward Island, as Worrells were proprietors of an estate that, for a time, comprised nearly 100,000 acres.1 For most of the first half of the 19th century, Charles and Edward Worrell managed the Worrell family’s lands, tenants, shipyards, mills, and store from a grand house overlooking St. Peters Bay in northeastern Kings County. They entertained distinguished guests at their residence and were active participants in Island politics and social life. The Worrells’ engagement with the Island began with the purchase of tens of thousands of acres at the beginning of the 19th century, and ended with their departure and the sale of the estate at mid-century. They came, they invested, and then they left.

2 To date, the best explanation of what the Worrells sought to achieve on Prince Edward Island is found in Brook Taylor’s biography of Charles Worrell in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.2 The account that follows builds on Taylor’s fine work by situating Charles’s years on Prince Edward Island within the broader history of the Jonathan Worrell family, and by placing the Worrells’ Island investments in the context of family choices that unfolded in Barbados, Britain, and France as well as in Prince Edward Island. Viewed from this perspective, we can see the extent to which the Worrells’ choices reflected an attempt to maintain cross-generation gentility in the face of challenges posed by a large family and the destabilizing dynamics of a revolutionary age. As well, we can better see the interconnectedness of the Atlantic world that the Worrells occupied and the place of Prince Edward Island within it.

3 The wealth that permitted the Worrell family to acquire one of the largest estates on Prince Edward Island in the early 19th century came originally from sugar plantations on Barbados. John Worrell, the grandfather of the Jonathan Worrell who bought land on Prince Edward Island, appears to have accumulated capital by working as a tailor. By the early 1700s, he had acquired a small sugar acreage, and slaves to work it, in the fertile but hilly parish of St. Thomas in central Barbados. Four generations of Worrells would make St. Thomas their home. Their marriages and christenings took place at the Church of England there, and members of the family were buried on Worrell land that came to be part of a plantation named Sturges. The port of Georgetown, six miles off to the southwest and the capital and mercantile hub for the colony, was visible from the high hills around St. Thomas.3

4 In the years after John acquired land in St. Thomas parish, the Worrells became closely linked by marriage with other families of the district. Marriage agreements and inheritances tended to keep property within a limited cluster of relatives.4 John’s youngest son, Jonathan, became a doctor in St. Thomas and married Mary, daughter of William Bryant. Bryant’s wealth included sugar holdings in the northern St. Andrew Parish of Barbados that would become part of a plantation known as Sedgepond. Jonathan and Mary’s only son, also named Jonathan, was born in St. Thomas in 1734. Educated at the University of Glasgow, Jonathan graduated in 1752 – a year before his father died. On Jonathan’s return to Barbados he assumed control of his father’s property, which became his when he turned 25. He also inherited the property of his grandfather, William Bryant, who died in 1757.5 In 1760, Jonathan was elected for the first of two terms that he served in the Barbados House of Assembly. That summer he married Jane Harrison, daughter of his first cousin George who was himself a wealthy St. Thomas doctor and plantation owner. The following year, Jane gave birth to a daughter, Mary, who does not appear to have survived childhood. In 1762, Jonathan became chief justice of the Court of Grand Sessions of Oyer and Terminer.6

5 Sometime in 1763 or early in 1764, as the Treaty of Paris confirmed the end of the Seven Years’ War, Jonathan Worrell and his household moved to London. As with other Caribbean planters who moved to Britain, Jonathan and Jane appear to have brought at least one of their household slaves with them. Court cases mounted by the crusading abolitionist Granville Sharp in 1765 and again in 1772 raised doubts, however, about the legal status of slaves brought to Britain, and the powers of those who claimed to own them. Lord Mansfield’s landmark ruling in the second case was particularly troubling to slave owners resident in Britain, and the West India planter interest in general, as the popular press interpreted it as abolishing slavery in Britain.7

6 Shortly after moving to Britain, Jonathan Worrell found himself a widower with an infant son. Jane’s second child, William Bryant Worrell, was baptized in London in 1764, shortly before Jane’s death.8 Jonathan moved to Ipswich, in Suffolk, and in January 1766 he married Catherine, the 18-year-old daughter of Charles Weston, a banker and seller of lottery tickets resident in Norwich.9 That Jonathan lived the remaining years of his life in Britain, not in Barbados, was likely related in part to his choice of a young wife with no apparent ties to Barbados. Many years of possible childbearing in a relatively healthy British context rather than a Barbadian one with high child mortality rates significantly improved the chances of Jonathan having a large family.10 Jonathan and Catherine’s first child, Jonathan Jr., born in 1766, was followed by seven siblings born while the family lived in Ipswich.11 During these years Catherine sat for a portrait by Benjamin West, who portrayed her as Hebe – the goddess of youth and cupbearer of the gods. Ozias Humphry, the famous painter of portrait miniatures, created a small likeness of Jonathan that was set in a brooch surrounded by diamonds.12

7 As with the commissioning of works by prominent artists, the Worrells’ choice of residences in Britain reflected their aspirations. The property they purchased on Silent Street in Ipswich had a double coach house, stables, a walled garden planted with fruit trees, and a courtyard surrounded by iron palisades. The interior featured a mahogany staircase, a chimney decorated with marble, a wine vault, and ample space for servants.13 In 1781 the Worrells moved to Hainford in Norfolk and purchased Hainford Hall, a three-storey, slate-roofed country house. The property is likely the “commodious Brick Mansion-House” advertised for sale by auction in October 1780, with stabling for 12 horses, a brick barn, and a large garden well-planted with fruit trees.14 There, Catherine gave birth to three more children.15 Jonathan’s Barbadian wealth provided the resources for purchasing a British country seat and as well for assuming roles in Britain suitable to a man of his status. Jonathan served two terms in the mid-1780s as one of the sheriffs of Norfolk, and supported various cultural and charitable institutions and appeals.16

8 Despite their comfortable lives, Jonathan and Catherine must have worried about how to use their resources to provide for appropriate futures for their children. Jonathan’s oldest son and Catherine’s stepson, William Bryant, became a barrister in 1788 after fulfilling the requirements for membership in Inner Temple, one of London’s Inns of Court.17 He may have seemed the obvious person to manage the family’s property in Barbados, given that he would inherit several of the plantations on his father’s death and, through his legal training, might have acquired skills and connections that would be useful in running a plantation and participating in Barbadian politics and society. It seems that both William Bryant and his half-brother, Jonathan Jr., travelled to Barbados in November 1788. The young men were in their early twenties, and a revolution was just getting underway in France that would have significant implications for life in Britain, the Caribbean, and the broader world.18

9 When the Worrell brothers travelled to Barbados, William Bryant and his father appear to have been considering selling some of their holdings but events elsewhere soon changed the context of their decision-making. The slave rebellion that broke out in Saint-Domingue in 1791, and ultimately led to the creation of the state of Haiti, benefitted British sugar producers, as did renewed British/French hostilities beginning in 1793.19 In these circumstances, Jonathan Jr. deepened Worrell ties with Barbados. In 1796 he married Rebecca Wilson Hinds, daughter of Samuel Hinds of St. Peter Parish, and for £10,000 purchased a 200-acre plantation adjoining the Worrell holdings at Sturges. His brother Thomas, nine years younger, joined Jonathan Jr. in Barbados around the turn of the century. Thomas died on Highland Plantation in 1802 at the age of 26.20 William Bryant made quite different choices, returning to London but eventually settling in Rouen, France, a major port for the French West Indies trade.21 William acquired a house in Rouen and a nearby farm, and in 1795 he married French subject Marie-Anne Elizabeth Catherine Amand. She was described on the marriage certificate as a “marchande de modes” with a business premise in Rouen; William Bryant is described as a “fabricant.”22 Although William Bryant visited London from time to time, it seems that Rouen was his primary residence until his death there in 1832, and that he was able to sustain himself comfortably in France “on his income” from his Barbadian properties.23 William Bryant’s widow also died in Rouen, in 1853.24

10 In 1795 Jonathan Sr. moved his family from Norfolk to Juniper Hall, an elegantly appointed, three-storey house on 50 acres that he purchased in Mickleham, in Surrey, 20 miles south of London (see Figure 1). The estate included an adjacent 78-acre farmstead with a house, barns, stable, and granary. A previous owner had rented the main residence to a cluster of prominent refugees from the French Revolution.25 When Jonathan and Catherine Worrell moved to Mickleham, the Worrell household included two sons, Edward and Septimus, ten and eight years old respectively, along with their three older sisters, Harriet and Bridgetta, both unmarried women in their twenties, and Celia Maria, aged thirteen. Three other siblings, Catherine, George, and John, appear to have died in childhood. Charles, Jonathan Sr. and Catherine’s second son, was completing a five-year clerkship begun with a solicitor in Norfolk in 1787; by 1798 Charles was a solicitor in a small firm in Lincoln’s Inn in London, handling, among other things, land sales and bankruptcies.26 Septimus, the youngest child, acquired a commission in the Coldstream Guards, and was on active service as an assistant surgeon from 1813 to 1821. He later became an improving landlord in Suffolk, although London seems to have been his primary residence.27 Edward became a lieutenant in the Mickleham Volunteers in the fall of 1803, when Britain’s war with France resumed after the brief Peace of Amiens. The following spring he gave up that position and moved, with his brother Charles, now in his mid-thirties, to Prince Edward Island. There, they established themselves as prominent estate owners on land that their father had purchased.28

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 111 Why, after generations of landownership in Barbados and decades of residence in Britain, did Jonathan Worrell purchase land in Prince Edward Island? Several factors may have been relevant to the decision not to invest more money in lands in Barbados, or in other sugar colonies, despite the presence there of Jonathan Jr. and others with whom the family maintained close relations. Barbados had offered several generations of Worrells the opportunity for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth, but Jonathan Sr., like many of his wealthy contemporaries, appears not to have considered it as his home.29 “Home” was the imperial centre, and one of the many benefits of acquiring a fortune from sugar was that it permitted retirement to a life of gentility in Great Britain. The relative risk of disease in tropical and temperate climates shaped this preference. Barbados was not a healthy place for the British, as Thomas’s death in 1802 indicated, and as evidenced by a one in five annual mortality rate among British soldiers stationed in Barbados in the period between 1795 and 1805.30

12 Moreover, while Barbadian investments offered the possibility of great returns they carried considerable risk as well. The tropical climate produced unpredictable storms of potentially devastating consequence, and fortunes built up over generations might be wiped out in a day. The great hurricane of 1780, for instance, destroyed plantations across Barbados and killed nearly 3,000 people.31 In Jonathan’s lifetime, war also posed serious risks. The American Revolutionary War cut off food supplies for Barbados and plunged the colony into depression, starvation, and crisis.32 The French Revolution and the wars it triggered demonstrated yet again the vulnerability of Barbados’s lines of supply. The slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue, which emerged in the wake of the French Revolution, highlighted another risk as well. Although Barbadian sugar exports benefitted from the destruction of the French sugar industry, Barbadian planters, like those in Saint-Domingue, relied on the coercion and violence of slavery and, in consequence, faced the ever-present possibility of a slave revolt. What happened in Saint-Domingue could happen in Barbados. Growing political pressure for the abolition of slavery was yet another threat to planters’ investment strategies.33

13 These concerns may explain why Jonathan Sr. and William Bryant appear to have considered the sale of the family’s plantations and other Barbadian property.34 In 1804, one of Jonathan’s town properties sold for £1,000.35 Certainly the risks posed by war were on Jonathan Sr.’s mind when he drew up his will in 1811, which included provisions “in case there shall be any invasion of the Island of Barbados by an enemy . . .”.36 All of these vulnerabilities, and the longer-term consideration that sugar production reduced the fertility of soils and tended to be most profitable in new zones of production rather than older sugar colonies such as Barbados, no doubt played some role in shaping the Worrells’ choice – Jonathan Jr. excepted – to begin investing somewhere other than in Barbados.37

14 In the years prior to the American Revolution, Britain’s colonies on the southern mainland had provided opportunities for planters looking for alternatives to Barbadian investments.38 The Revolution changed the boundaries of the British Empire, and thus reduced opportunities for those who wished to keep their land holdings within it. The Revolution also changed what was available to purchase in the coastal portions of what remained of British North America. In the post-Revolution period, because of escheats and a new policy for granting Crown land, large tracts were increasingly rare. Prince Edward Island was an exception. There, in the years after the Seven Years’ War, the Crown had distributed most of the land in lots or townships of 20,000 acres, and land continued to sell in large blocks at the beginning of the 19th century.39

15 Buyers interested in establishing themselves as members of a North American landed elite, or in developing the commercial potential of North America’s woods, soils, and waters through fee simple ownership, were likely to find more opportunities in Prince Edward Island than in other eastern British North American colonies. As well, Island lands were relatively cheap. In the late 18th century, it was not uncommon for townships of 20,000 acres to change hands for £500, or less.40 Prices were low in part because of lingering questions arising from the conditions in the original Crown grants, which required grantees to make annual quit rent payments to the Crown and to establish settlers. Some feared – while others hoped – that Island grants would be escheated to the Crown because of proprietors’ past failures to meet the settlement obligations, or that the Crown would seize land to pay years of quit rent arrears and would expect owners to pay quit rents regularly in the future. For a variety of reasons, including political developments on the Island and in London, the 1790s and early 1800s were a time of flux for imperial policies on quit rent collection and escheat. This uncertainty created the possibility of bargains, as some Island landlords came to believe that they should sell their properties while they could lest their titles become worthless.

16 London was the main hub of exchange for information about the possibilities and risks of investing in Island properties. It was there that imperial planners shaped the prospects for the newly acquired colony with policies on the terms of land distribution, and there, too, that owners of Island lands met irregularly to further their collective interests. London was headquarters for many of the merchants with Island business, and for lawyers and land brokers who handled Island land transactions. Island lands were advertised in London and regional papers, and often sold at auction at Garroway’s and Christie’s coffee houses.41 Members of the Prince Edward Island elite, some of whom played a significant role in Island land transactions, moved in and out of London on a regular basis. Charles Worrell, with his solicitor’s practice in London, was well placed to learn about the possibilities of land acquisition on Prince Edward Island.

17 In 1803 and 1804, Jonathan Worrell Sr. purchased 44,700 acres of contiguous land in northern Kings County for £3,703 sterling. Jonathan, in a transaction involving two conveyances from William James Wray, arranged for one of Charles’s former law partners, Henry Maddock, to take title as trustee to 20,000 acres, with Jonathan, Charles, and Edward, who was still a minor, as the beneficiaries. The remaining purchases, from Alexander Ellice and Robert Shuttleworth, were to be conveyed to Jonathan as sole owner. Jonathan’s will and the terms of some of the conveyances indicate that his immediate objective at the time of purchase was to help establish Charles and Edward as proprietors of Island land, but also to acquire land for the family as a whole, in case others of his children, William Bryant included, might wish to take an interest in the Prince Edward Island estate. 42

18 Jonathan’s purchases involved him in a complicated round of Island land transactions. Alexander Ellice had retired to Britain after a long and successful career as a fur trader and Atlantic merchant. Ellice, whose estate was valued at £450,000 at the time of his death in 1805, owned plantations and properties scattered about the West Indies and the Americas. The 4,700 acres that he sold to Jonathan Worrell was part of a sell-off of his 64,700 acres on Prince Edward Island.43 William James Wray had recently acquired the township that he sold to Jonathan Worrell from his cousin, the substantial landowner and sometime Whig parliamentarian Sir Cecil Wray, to whose baronetcy William Wray was heir. William Wray sold another 20,000-acre township that he had acquired from Sir Cecil to Charles’s other former law partner, Plowden Presland. Present as witnesses to the conveyances were two major figures in Island land transactions: the collector of quit rents, John Stewart – from whom Wray had originally purchased the townships in 1794 – and his brother-in-law William Townshend, the Island’s collector of customs.44 The 20,000 acres that Jonathan purchased from Robert Shuttleworth was by far the most expensive of the parcels, because of its locale on St. Peters Bay and because it included a grand house that Shuttleworth had built for his family. Shuttleworth, heir to extensive landed wealth, had moved to the Island during the 1790s; when he decided to return home after two years, he left an estate that offered some of the accoutrements of gentility.45

19 Other investors, too, were buying large quantities of Island land during this period. The 5th Earl of Selkirk purchased more than 115,000 acres in 1803-1804, and added 30,000 acres more during the following two years. His purchases were scattered and cost him around £2,105 in all, only 56 per cent of the Worrells’ investment, and only 40 percent more than Plowden Presland paid to Wray for his 20,000 acres. Selkirk sailed to Prince Edward Island in 1803, remaining for a few weeks to assist in establishing three vessels of settlers he had directed to the Island.46 The other large buyer contemporary with the Worrells was James Hodges, a wine and timber merchant of London and Chepstow. He was a partner in the firm of Boucher, Hodges & Watkins, which by 1807, if not sooner, was building large vessels in Britain ranging in size from 400 to 800 tons. Hodges purchased 50,000 acres, primarily from Ellice, for a total price of £5,150, almost two and a half times what Selkirk had paid for his much larger estate.47 As Alexander Ellice observed, Island townships were attracting purchasers from among “respectable and industrious men.”48

20 Early in 1804, Charles, likely accompanied by his brother Edward, sailed for Prince Edward Island to manage the Worrell lands as well as Presland’s adjacent township.49 Prince Edward Island, at the time, had a population of around 7,000 scattered across 2,000 square miles, a twenty-fifth of the population density of Britain and a hundredth that of Barbados.50 Charlottetown had 416 residents in 1798; the population of London was nearing one million.51 Edward stayed for almost three decades and Charles for more than four (with occasional trips back to Britain), and they expanded the family’s investments in the Island.

21 As Brook Taylor has observed, the evidence does not suggest that Charles sought to practise law on the Island – although in 1842 he agreed to act as land agent for absentee proprietor Lady Westmorland when, as a widow, she regained control of the lands she had inherited before her marriage. Her holdings on Lot 53, which she had toured in 1840, adjoined part of Charles’s estate. Given proprietors’ problems with finding reliable agents on the Island, Charles’s services as lawyer or land agent would have been in demand.52 Ellice, who met Charles in Britain, had considered retaining him, but Ellice’s resident agent and the Worrells’ neighbour on the Island, John Cambridge, may have warned Charles of the risks of a career that might require him to sue Island notables united by close ties of family. Cambridge had been nearly ruined by a long legal and political dispute with William Townshend and other members of the Island elite. In 1803 Cambridge informed Ellice that he would prefer not to act on Ellice’s behalf in collecting debts from the well-entrenched members of the extended family of chief justice Peter Stewart, including his son, John Stewart, and son-in-law, William Townshend; Cambridge thought it “not very expedient to Wage War with so powerful an Army so well fortified.”53 In 1811 an Island lawyer described Charles as, perhaps, “the most peaceable Lawyer in North America,” who had not been heard to “professionally utter half as many words as he possessed acres of Land.”54

22 There was much in Charles’s and Edward’s lives on the Island that paralleled that of their father in Barbados and in Britain, though much that differed as well. Within a few years of arriving on the Island Charles was appointed as a justice of the peace and keeper of the rolls for Kings County, and in 1808 he was appointed high sheriff – posts similar to those that had been held by Jonathan Sr.55 Edward served on the grand jury in 1812. Both Charles and Edward were officers in the Kings County militia.56 The manor house and farm that Jonathan Sr. acquired for his family at Mickleham in Surrey provided the family with an identifiable status, even after Juniper Hall was sold.57 Prince Edward Island, too, had its grand houses and country seats, occupied by those seeking to construct a life of gentility. Charles and Edward came to be identified with Morell House, which was one of the grandest private dwellings on the Island. Visitors during the 1830s noted Charles’s desire to show off his garden and farm, and to call attention to the different vistas the property offered.58 In the vicinity of Morell House, other significant landowners also used their residences to establish their place in Island society. Mount Stewart on the Upper Hillsborough River was the residence of John Stewart.59 Captain John McDonald, the proprietor of Lot 36 who had also inherited leadership of the Glenaladale branch of Clan MacDonald, occupied the opulent Glenaladale House, which he had built along the shore in the late 18th century. Such luminaries also maintained a seasonal presence in the capital city, Charlottetown, just as their British counterparts did in London.60

23 Jonathan Sr. had participated in electoral politics in Barbados, but that was not part of his role as a country gentleman in England. Charles and Edward, having moved to the Island at a moment of heightened state and popular attention to landlords’ obligations, became involved in politics in part to protect the material basis of their status as gentlemen. One of Charles’s first political acts after his arrival on the Island was to join with John Cambridge and William Townshend in presenting a memorial to the Island’s new lieutenant-governor, J.F.W. DesBarres, on behalf of resident and non-resident proprietors. The proprietors emphasized the extent of their investments in the Island in order to counter any “unfavourable impressions” that DesBarres might have formed from listening to members of the elected assembly who, under the “baneful influence” of “the levelling principles of France,” were calling for enforcement of quit rent payment and the escheat of undeveloped townships.61

24 Across their decades as Island landlords, Charles and Edward faced a persistent and growing popular demand for an end to the concentration of control of land in the hands of a few – and an end to the concentration of power that came with it. They responded with political activity on the Island and lobbying efforts in London. Charles was elected three times to the Island House of Assembly, serving from 1812 to 1824. John Cambridge’s son, Lemuel, nominated Charles to be speaker of the house for the 1818-19 session. Charles lost the vote, though, to Angus Macaulay, who had helped to recruit the immigrants that Selkirk brought to Prince Edward Island but over time had become a spokesperson for growing rural discontent with the Island’s land system.62 In the mid-1820s Charles was appointed to the Island’s combined legislative and executive council, which acted as the upper chamber of the legislature and as the lieutenant governor’s cabinet, a position he held until 1836. In 1839, when the two councils were divided, Charles was appointed to the legislative council and served for four tumultuous years while radical land reformers held a majority in the lower house. Charles resisted taxation on landlord holdings, whether through quit rent collection or new taxes to be paid to the Island government, and fought persistent demands for an escheat of large estates. From his position in council, Charles tried to shape assembly politics by lending his support to candidates who would resist land reform.63

25 Importantly, too, Charles and Edward worked closely with other landlords on the Island and in Britain to protect their common interests. They established a close working relationship with another pair of brothers, David and Robert Stewart, who were seeking to develop an Island estate that in some ways paralleled that of the Worrells. The Stewarts, professional estate managers in Britain, acquired Island land shortly after Jonathan Worrell made his first purchase there, and they enlarged their holdings with the purchase of tens of thousands of acres in the second quarter of the 19th century.64 David met with Charles when the former visited the Island in 1831, and the two appear to have agreed on the need to construct an effective lobby group to promote proprietors’ interests.65 On his return to London, David wrote to the sixth Earl of Selkirk for assistance in coordinating landlord lobbying and reported that Charles Worrell was the only person he had encountered in the colony who was truly supportive of the interests of great proprietors.66

26 The sixth earl’s uncle, Andrew Colvile, managed the Selkirk estate during these years, and Colvile worked closely with the Stewarts in responding to the threats to proprietors of Island land. Like the Worrells, Colvile had Caribbean roots and owned West Indian plantations.67 Colvile was an experienced player in the sugar trade and the West Indies lobby, and an important figure in the affairs of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Island proprietors’ lobby group, the Prince Edward Island Association, which had begun to take shape after David Stewart returned to Britain from the Island, was formally launched in 1834. Similarly to the West India Committee, the Prince Edward Island Association held regular meetings in London, reviewed relevant developments in Prince Edward Island, and lobbied vigorously and persistently at the Colonial Office.68

27 Unlike their father, Charles and Edward never married. Also unlike Jonathan Sr., they became merchants. In Prince Edward Island, Charles and Edward discovered that they would have to accept rents in farm produce, wood, and labour in order to realize returns from leasing land as specie was scarce. They also learned that the best way to make a profit on goods collected from tenants, or produced with tenants’ labour, was to market those goods themselves. The Cambridges, who lived on a large farm across St. Peters Bay from Morell House when the Worrells moved to the Island, had for many years combined boat-building and trading in agricultural and wood products with estate ownership.69 Charles and Edward followed suit. They opened a store on their estate and sold goods ranging from necessaries to luxuries, including rum, salt, powder, shot, nails, needles, thread, cloth, and wine glasses. In November 1806 Charles and Edward sent a 49-ton vessel loaded with barrels of salted meat, oats, potatoes, and live sheep to St. John’s, Newfoundland; the next year they sent shiploads of farm produce to the Burin Peninsula. In time the brothers built and acquired larger vessels and, as well, commissioned other ship owners to carry their goods, mostly to Newfoundland, which provided an important market for live cattle, sheep, and pigs, but also to Halifax and other ports. As well, they exported vessels and wood products processed in their mills for sale in Newfoundland and Great Britain.70

28 Charles and Edward purchased yet more land as they consolidated their commercial and social positions, and Charles continued to buy into the 1840s.71 While many of those who assembled large estates on the Island acquired townships or parts of townships scattered across the colony, the Worrells incrementally bought land in the immediate vicinity of their father’s earlier purchases on Lots 39, 40, and 41 – a core region in the earlier French development of the Island. By 1841 the Worrell estate included property on Lot 38, to the west of the lands Jonathan Worrell had purchased, as well as land on Lot 42 and Lot 43 to the east and Lot 66, which lay to the rear of Lot 38.72 They also acquired town lots in Charlottetown and Georgetown, and the voting rights that went with them.73

29 Charles and Edward, despite their bachelor status, developed close relationships with leading families on the Island, including the neighbouring Cambridges. When the Worrells had arrived on the Island, John and Mary Cambridge had been attempting to survive various legal and financial setbacks, including bankruptcy, by pursuing commercial farming and trade. Gradually, they rebuilt their business interests.74 Their sons, Artemas and Lemuel, when they came of age, followed other members of the Island’s elite in alternating residences on either side of the Atlantic.75 Also closely linked with the Worrell family was that of Robert Gray, a Loyalist who had served with Colonel Edmund Fanning during the Revolutionary War. Gray came to Prince Edward Island in 1787, the year after Fanning was appointed lieutenant-governor, and served as Fanning’s personal secretary. His father-in-law, George Burns, was an early owner of the land that the Worrells purchased from Shuttleworth.76 Charles and Edward may have met Gray in London, as he resided there on several occasions in the years prior to and during the Worrell purchases and was active among those with an interest in Island lands. The relationship between the Worrell and Gray families came to include Charles and Edward’s siblings and Gray’s six children, who were quite young when their mother died in 1813.77 Charles and Edward’s unmarried sister, Harriet, for example, seems to have offered assistance to a youthful John Hamilton Gray, a future premier of Prince Edward Island, when he moved to England to complete his education.78

30 All of this is to say that the Worrells assimilated quickly and thoroughly into Prince Edward Island’s landowning elite. Name choices and the distribution of legacies provide a small window into the complex layering of connectedness that bound Island families and spanned the Atlantic. Robert Gray (Jr.), John Hamilton’s brother, who resided in London in the mid-19th century, was executor of Harriet’s will. She distributed over £5,900 among the four surviving Gray siblings and their children. These beneficiaries included her god-daughter, Harriet Worrell Gray, who was John Hamilton Gray’s first daughter, and also the five children of Jane Gray and her husband Artemas Cambridge.79 Edward, too, named “his old friend Robert Gray” as his executor and distributed over £10,000 to members of the Gray family, including Edward Worrell Jarvis – the son of Chief Justice Edward Jarvis by his second wife Elizabeth Gray.80 Others who gave the name Worrell to their children were less fortunate. There were no provisions in the Worrell wills for Edward Worrell Webster, born about 1810, for Charles Worrell Townshend, son of John Dalton Townshend and grandson of William Townshend and born about 1831, or for Charles Worrell MacEwen, born about 1836.81

31 Jonathan Worrell’s disposition of his estate played a significant role in shaping how the family would function after his death in 1814, and in enabling Harriet and Edward many years later to be so generous to the Grays and others. In 1811 and 1812, when he made his will and added a codicil, Jonathan Sr. owned Juniper Hall in Surrey, sugar plantations in Barbados, and the land that he had purchased early in the 19th century in Prince Edward Island. Jonathan Jr. owned Highland Plantation in Barbados in his own name, and William Bryant was heir to the plantations that his father held as life estates through marriage to his first wife Jane Harrison. Charles and Edward had property they had purchased in their own names in Prince Edward Island. When Jonathan Sr. died only two of his children, William Bryant and Jonathan, were married, and their wives had no children. After providing for an annual income for his widow, Jonathan left his goods and plantations in Barbados to William Bryant Worrell for his life. If William Bryant died without children, the properties were to be divided among Jonathan Sr.’s children in equal shares. Jonathan gave 20,000 acres in Prince Edward Island to Charles and Edward, and divided the remaining 24,700 acres among their siblings. After Jonathan’s death, rather than becoming Island proprietors themselves, resident or otherwise, they sold their interests to Charles and Edward for a total of £3,286 sterling, which had been set by two independent valuators from the Island.82

32 As Charles and Edward grappled with the threats of escheat, demands for quit rent payments, and the imposition of new taxes on their lands, they were not alone among the members of the Worrell family in having to deal with threats posed by popular unrest and the emergence of a seemingly ever more activist state that was responsive to popular demands. In Barbados, too, the Worrells faced threats to their interests. The example of Saint-Domingue showed that slave societies could be changed. Britain’s abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in 1807 inspired hope for reform, and generated demands for a slave registration system to restrain any illegal trade in slaves. Barbados plantation owners vehemently, but unsuccessfully, resisted enactment and enforcement of legislation that would require them to provide periodic inventories of the enslaved people living on their plantations and, to add insult to injury, to pay for the registration system. Planter resistance to slave registration, however, had the unexpected consequence of helping to trigger a major revolt of enslaved peoples in Barbados. Rumour among the black population of Barbados cast slave registration as evidence of Parliamentary intent to end slavery, and portrayed planter resistance as part of a plot to defeat that laudatory goal. In April 1816, Bussa’s Rebellion, as it came to be known, spread across much of the island. Roughly a fifth of the sugar crop was burned, along with many plantation houses and other buildings. Hundreds of enslaved peoples and free blacks and mulattoes were killed in battle, shot on capture, or subsequently executed.83

33 The violence in Barbados must have confirmed Jonathan Jr. and Rebecca Worrell in their decision to sell Highland Plantation and leave Barbados in 1816. After the Treaty of Paris (1815) ended Britain’s long war with France, Jonathan Jr. – like Jonathan Sr. after the Seven Years’ War – moved to Great Britain. He purchased an estate in East Grinstead, Sussex, known as Frampost, and remained there until his death in 1843 (see Figure 2). His will revealed his continuing connections with plantation owners from Barbados who were also living in Britain. These included George Carrington of Missenden Abbey, whose son George at times served as the British agent for Barbados, and William Grasett, who had once been a member of Council in Barbados and had a family connection to Rebecca.84

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 234 When slave registration on Barbados began in 1817, the registry documents simplified the complexities of Worrell family property ownership by treating all the remaining plantations of the late Jonathan Worrell Sr. as the undivided property of William Bryant Worrell. In identifying properties, the records consolidated several plantations into three entities: Sturges, with 28 enslaved people; Neils, in Saint Michaels Parish, just east of Bridgetown, with 75 enslaved people; and Sedgepond in the north, with 123 enslaved people. As would be expected, given the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, most of the enslaved people on the Worrell plantations had been born in Barbados. There were no African-born enslaved people at Sturges while there were two at Neils and seven at Sedgepond, including the youngest of this group at age 35. There were also nine people listed as “coloured” rather than “black” at Sedgepond, compared to one each at Sturges and Neils. The logic of the plantation economy was reflected in the various field gangs, ranging from the “first gang” which was assigned the most strenuous work, to the third, or grass-gathering, gang composed of children between six and fourteen at Neils and Sturges, and between six and eleven at Sedgepond. A few people on each of the plantations held specialist positions such as carpenters, watchmen, and house servants. The thirty-year-old carpenter at Sedgepond bore the name William Bryant, as did a three-year old boy who is listed as “coloured.”85

35 As the Great Reform Act of 1832 and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 transformed the fundamentals of the world into which the Worrell children had been born, the Worrells remained connected to the old plantation economy. With Jonathan Jr.’s withdrawal from Barbados in 1816, William Bryant was the Worrell with the greatest property interests at risk in the Caribbean. He, however, did not see the changes brought by slave emancipation, as he died in Rouen in 1832 leaving all of his property to his widow. Obtaining the proprietors’ compensation payments under the Abolition Act and managing the Worrell property in Barbados became matters for her to deal with in conjunction with other members of the Worrell family.86

36 In Prince Edward Island, meanwhile, the 1830s ushered in a period of vigorous popular demand for the escheat of landlords’ estates, those of Charles and Edward included. A serious economic depression in the late 1820s sent shock waves through the Island merchant community, as it did elsewhere in the Atlantic World. A contraction of credit proved disastrous for many, including well-established merchants such as the Worrells’ friends Robert Gray, Artemas Cambridge, and Lemuel Cambridge – who had worked together in various combinations and at various times as traders and merchants in Bristol and Prince Edward Island; all became bankrupt.87 Hard times diminished tenants’ ability and willingness to pay rent and increased their opposition to a land system that required them to do so. Sporadic harvest failures during the 1830s, and yet more sharp downturns in the Atlantic economy toward the end of the decade, fuelled extensive popular unrest on the Island. News of the Reform Act and the Slave Emancipation Act was received on the Island as evidence that the time was ripe for realizing other popular demands for change. Those seeking to liberate Island tenants from proprietors pointed to parallels with the emancipation struggle. If the imperial government could intervene in the supposed property rights of plantation owners, why could it not do the same with the supposed property rights of Island landlords? And if the imperial government could afford to pay 20 million pounds sterling to compensate plantation owners in order to right a social wrong on tropical plantations, why could it not provide the much smaller sum necessary to buy out proprietors on Prince Edward Island?88

37 The slave emancipation precedent provided useful evidence that there were times when the state needed to interfere with the “sacred rights” of private property in order to ensure social justice. Beginning in the late 1830s, and continuing for many years, reform-minded Island legislators proposed arrangements for state intervention to eliminate landlordism on Prince Edward Island, including state funding for landlord compensation.89 Island historiography has tended to highlight landlord resistance to these initiatives, and for good reason. Many proprietors vehemently and effectively made their objections known to imperial officials and the public in general. But behind the scenes, some landlords began to explore the merits of state intervention in landlord/tenant relations on the Island and the possibility of state purchase of their increasingly contentious property rights. Charles Worrell was among the first of the owners of large estates to broach the idea of state purchase of his lands in private correspondence with the Colonial Office.90

38 Catherine Worrell noted in her will, written in 1832, that Charles and Edward had “been very unfortunate with their property in Prince Edward Island.” The following year, Edward moved back to London. Although he continued to be active in landlord lobbying efforts, and attended to British facets of the partnership’s merchant trade, he sold his share of Island lands and other assets of the brothers’ partnership to Charles in 1837 for £5,250 Island currency (£3,500 sterling).91 The sum does not suggest that their business venture was going well. Visitors to Morell House in the 1830s commented that it was “going fast into decay” and that the Worrell estate was poorly managed and unprofitable.92 These comments, however, require contextualization. Morell House was, no doubt, showing its age, and its grounds and gardens did not compare favourably with the well-tended English and Barbadian properties that informed some of the observations. Nor did Charles’s practices as landlord and storekeeper conform to models some observers embraced. For them, his leases were too short, his rents too high, and he was insufficiently vigorous in collecting debts. Charles’s description of the estate when he advertised it for sale in 1846 paints a much more favourable picture: it emphasized the geographical logic of the estate that formed “one entire block” of between 90,000 and 100,000 acres; it highlighted the 100 miles of roads and extensive frontages on seacoast, bays, and rivers as well as four shipyards, five sawmills, a gristmill, and a carding mill; and it noted the 400 tenants who were making the land productive. The advertisement also highlighted the planning that had informed the Worrells’ estate design. Tenants, who for the most part occupied farms of roughly 50 acres, all had access to an adjacent 50 acres that they might purchase or lease in the future. Rents were graduated, and the £1,000 per year in rents currently due from tenants would soon become £2,000 per year. In short, the advertisement described a well-planned, large estate designed to facilitate increased rentals over time and capable of providing “a man of capital” with “permanent provision” for himself and his family.93 The advertisement did not warn that these projections were contingent on collecting rents and securing landlords’ property claims in a context in which doing so was becoming increasingly difficult. Nonetheless it is telling that in 1854, when the Prince Edward Island government finally purchased the Worrell estate, the price, after final adjustments, was more than £21,000 Island currency (roughly £14,000 sterling), and this after Charles had sold a great deal of land as small freeholds and after his successors in title had sold off a particularly valuable farm on the ocean for £1,400.94

39 Despite the challenges that Edward and Charles had faced, the Worrells’ presence on Prince Edward Island appears to have played a role in drawing emigrants and visitors who had connections to the family’s Barbadian past – particularly as the economic depression of the late 1820s and the end of slavery in the early 1830s forced many among the Barbadian elite to reconsider how best to provide for their families. Among these were the Barrows, who had once owned several sugar properties, including Sunbury Plantation in St. Phillip’s Parish in Barbados with its 250 enslaved workers. John Barrow had lived in Britain at the family’s country seat in Kent as well as in Barbados, and had a family connection to the Worrells through Jonathan Jr.’s wife Rebecca.95 By the early 1830s the Barrows had lost control of Sunbury Plantation in a Chancery Court battle and had settled into Hillsborough House in Charlottetown, where John Barrow served as puisne judge of the Island Supreme Court. In the aftermath of the uprisings in Upper and Lower Canada in the winter of 1837-1838, and major demonstrations of tenant power on Prince Edward Island, Barrow assumed a leadership role in calling a public meeting in Charlottetown to declare loyalty to the Crown. His speech was published in full in the Barbados press and lauded by the editor of the Barbadian.96

40 Rev. John Packer and Nathaniel T.W. Carrington, who had Barbadian connections to the Worrells, visited both the Barrows and Charles Worrell in 1837. Carrington reported that the Barrows continued to “live in sumptuous style,” although they regretted “the loss of their Barbados property and the luxuries afforded by it.”97 Carrington was the grandson of Jonathan Worrell’s sister and was visiting the Island as part of a family tour of eastern North America. Packer, who was 38, had been rector in St. Thomas since 1832, and also a teacher of classics. Before leaving Prince Edward Island he signed an agreement to purchase a 1,250-acre property from Charles and Edward’s acquaintance, Chief Justice Edward Jarvis. When Packer returned with his wife and family in late August, he assumed duties at St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Charlottetown.98

41 There were at least four other Barbadian arrivals on Prince Edward Island in 1837-1838. A Mr. Taylor purchased Lot 65 in the spring of 1837, and the Allen family came to the Island that fall, followed by the interrelated Boyce and Farnum families. Naboth Greaves Boyce had been a planter in St. Thomas, and, like Jonathan Worrell, had served as a St. Thomas representative in the Barbados House of Assembly.99 John Edward Worrell Alleyne and his family moved from Barbados to Prince Edward Island in 1838. His mother was Martha Worrell, sister of Jonathan Worrell Sr. The Alleynes made Hillsborough Castle on Township 38 their home, and he served as a Kings County justice of the peace from the early 1850s until his death in 1868.100

42 Some of the Barbadian emigration to Prince Edward Island was directly linked to the established presence of the Worrells, whose connections with family and friends in the Caribbean were continuous and long-standing. When, for example, Dr. J.W.W. Carrington of St. Thomas, Barbados, died during a voyage to Britain in 1855, Harriet and Edward both immediately provided substantial financial support for his widow.101 Dr. Carrington was the grandson of Jonathan Worrell’s sister Mary, and thus the first cousin once removed of the Worrell siblings. In their wills, Catherine, Charles, Harriet, and Edward all left legacies for relatives in Barbados, totalling £4,700. As well, Harriet and Edward left money for the J.E.W. Alleyne family in Prince Edward Island.102 Other Barbadian emigrants may have been drawn by promotional work orchestrated by the Prince Edward Island Association. The Worrells likely had a hand in that as well, given their prominence in the organization.103 Certainly there was a flurry of interest; Lord Selkirk’s agent noted reports in the late 1830s that the West India Bank would be establishing a branch in Prince Edward Island.104 It is difficult to establish just how many emigrants came to the Island from Barbados during the 1830s, and how many stayed. Rev. Packer’s residence on the Island was brief, as was that of some other emigrants. Packer chose to leave after one winter, citing the health of one of his family members as the reason. The Boyce and Farnum families were on board the steam packet to Pictou with him when he left Prince Edward Island, and were back in Barbados roughly a month later.105 No doubt Prince Edward Island’s winter weather discouraged the emigrants, but they were likely disheartened as well by agitation against landlordism, extensive resistance to land agents and law officers, and continuous discussion of demands for radical land reform in the legislature and beyond.106

43 In the mid-19th century, the family of Jonathan Worrell completed arrangements for ending both its longstanding property ownership in Barbados and its more recent estate holding in Prince Edward Island. Neither development unfolded easily. William Bryant Worrell’s death in 1832 placed much of the Worrell property in the hands of his widow and heir Marie-Anne Catherine (Amand) Worrell, although the Worrells’ share of Crown payments for slave compensation was collected primarily by the surviving Worrell children.107 Following the death of William Bryant, the government of Barbados asserted that his plantations had escheated to the Crown because Mrs. Worrell was not a British subject and therefore not entitled to hold real property in Barbados. The escheated Worrell properties, about 450 acres in total, were auctioned in January 1840 for more than £30,000. William Bryant’s widow, supported by her British in-laws, petitioned for the return of the properties or for the money paid for them, and the imperial government ultimately instructed the Barbados government to transfer the proceeds of selling the properties to the Worrells.108

44 In Prince Edward Island, radical land reformers, who came to be known as Escheators, had gained control of the House of Assembly in 1838. Their efforts to redistribute land by escheat were thwarted by the Legislative Council and the Colonial Office, but pressure for land reform persisted. Popular activism undermined the legitimacy of landlords’ property claims, impeded their ability to collect rents, and eroded the norms and assumptions that had sustained a land system based on the original British township grants. The final, state-led termination of landlordism on the Island did not come until the 1870s but, as with slavery, the likelihood of its demise was there for prescient people to see well in advance of the end.109

45 Charles was in his early sixties at the start of the tumultuous 1830s, and by the end of the decade was sole owner of Worrell properties on the Island. His share of the family’s slave compensation money likely provided welcome cash in a period of economic stress and tenant rent resistance. Charles, surprisingly, opted to purchase yet more land in eastern Prince Edward Island in the late 1830s and early 1840s during a period of rent strikes and Escheat Party electoral success, and even as he was considering selling his estate. Perhaps he was a compulsive purchaser of land, or perhaps he saw deals that were too good to pass up. Some purchases may have been part of package arrangements that allowed him to collect outstanding debts, or to assist friends and relatives facing financial difficulties. Or he may have thought, in some cases, that particular additions to his holdings would render the estate as a whole more valuable. Whatever the case, selling his estate and returning to Britain came to dominate Charles’s thinking in the 1840s. If he had hoped to sell the estate to the government, his timing was not propitious. While the Escheat Party was in power, the colonial secretary rejected proposals for imperial support for a voluntary buy-out of landlords; only in the early 1850s did new political alignments make this approach possible. Nor was Charles successful in finding a private buyer for the estate as a whole. In the summer of 1848 he departed for Britain, leaving the management of his estate in the hands of trustees. The Island government, soon after, opened negotiations to acquire the Worrell estate, but members of the local elite used insider knowledge and connections to purchase the estate from the trustees and resell it to the government at a price well above what Charles would have accepted for it. Although Charles did not share in the ill-gotten profits, the transaction became known as the “Worrell Job.” Prince Edward Island’s version of state-orchestrated emancipation began on a sour note.110

46 The last chapter of the colonial experience of the Worrell family was set in the imperial centre, where the surviving Worrell children established their households. Bridgetta had married a few months after her father’s death in 1814, but died the following year without children.111 William Bryant and Jonathan Jr. had also died prior to Charles’s return to London, without any children to carry on the Worrell family name. At mid-century, the remaining sons and daughters of Jonathan Worrell Sr. lived in various fashionable parts of London. As they distributed their property on or before their deaths, they looked after each other, friends and acquaintances, charitable organizations, and their relatives in Barbados, Britain, and Prince Edward Island. The estates of the richest ran to nearly £35,000. That of the poorest, Charles, was evaluated at under £7,000. The death in 1869 of Celia, a widow without children, marked the end of the Jonathan Worrell family line.112

47 So what should we make of the Prince Edward Island component of the Worrell family experience? The evidence suggests that the Worrells did not realize the possibilities that Jonathan Sr., Charles, and Edward had seen in acquiring Island land at the beginning of the 19th century. Jonathan Sr. had imagined that his investment on Prince Edward Island might provide an income, and perhaps a home, not just for the two brothers who moved there in 1804 but for others of his children, too. The remaining siblings, however, sold the Island property they inherited to Charles and Edward on their father’s death. Certainly the brothers did not enjoy the financial success of Jonathan Jr., who returned to Britain when he was 50 and spent the rest of his years enjoying the comforts of Frampost and the company of other Barbadian planters who, like him, had retired to England. Part of Jonathan Jr.’s success lay with making a good marriage while he resided in the colonies, and Barbados was a propitious place for doing so as there were many wealthy families and more daughters seeking marriage partners than there were eligible men.113 As well, in Barbados Jonathan had the advantage of extensive family connections. If Charles and Edward had entertained the hope of marrying money and status, Prince Edward Island in the first years of the 19th century was not a good place for doing so as there were few families of their station, or higher, residing on the Island.

48 Some purchasers of large blocks of land on Prince Edward Island in the early 19th century likely believed that their purchases offered an opportunity for significant commercial gain. James Hodges invested for this reason, as did the London firm of Birnie and Waters.114 William Gosling and Son, London wine merchants, hoped to profit from a trade linking Prince Edward Island and the Atlantic coast of British North America with the wealth of Bermuda, the Caribbean, the Atlantic Islands, and Iberia.115 For a few brief moments, some of the many hopeful investors who gambled on the value of Prince Edward Island’s land and resources managed to make good returns on well-timed ventures in lumbering and ship-building; but the perils were great and the bankruptcies many.116 Although the Worrells engaged in the sale of wood and ships, their investments in these enterprises were relatively modest – particularly given the scale of their resources. However, the broad reality was that Prince Edward Island would never be a 19th-century equivalent of Barbados; wood and northern crops were not a replacement for sugar, nor was fish.

49 While Charles and Edward no doubt had expectations of commercial success that were not fully realized, other aspects of their experiences on Prince Edward Island may have come closer to what they hoped. As David Hancock has noted, the acquisition of land and the development of estates, in Britain and the colonies, was a common feature in the construction of gentility among London merchant elites in the late 18th century. Although these investments, made in the hope of realizing a good return, tended to be financially losing propositions, they were not necessarily a loss socially or culturally.117 For the Worrells, land purchases in Prince Edward Island gave Charles and Edward the opportunity to construct lives of gentility, albeit a rustic gentility. Barbadian money made it possible for them to occupy one of the grandest houses on the Island and to be lairds of an estate of tens of thousands of acres, peopled by hundreds of their tenants. In an Island context, Barbadian wealth placed Charles and Edward among the elite of the colony and provided Charles with the opportunity to hold many of the colony’s high offices. Had Jonathan’s land investments been made in Britain rather than Prince Edward Island, Charles and Edward’s circumstances, and profile, would have been much more limited. Such would also have been the case in Barbados. Even the full value of Juniper Hall, which was sold to fund legacies for Jonathan and Catherine’s children, would not have been sufficient to buy Jonathan Jr.’s Highland Plantation of less than 200 acres. The relative value of property in a transatlantic context, however, was such that the Worrells, for the price of Juniper Hall, might at the turn of the 19th century have purchased nearly half of Prince Edward Island.118 Gentility, in short, could be acquired at a discount on Prince Edward Island.

50 Gentility aside, there are many reasons why the Worrells, and many others, failed to prosper by investing in Prince Edward Island at a time when it was just beginning to develop as a British colony. Not the least of these was the changing political and social context of a revolutionary era. Who knows what the future could have held for Barbadian planters had the struggles for emancipation not undercut their labour and investment strategies? They faced many other problems as well, including declining agricultural productivity. In Prince Edward Island, agricultural output grew across the first half of the 19th century, as did the extent of cleared land. The value of landlords’ holdings might have been expected to reflect these changes in the Island’s productivity had struggles to end landlordism not reduced the returns from proprietary estates, and engendered doubt about the security of landlords’ titles. Tenant activism ultimately put a terminal date on the possibilities for living on income from landed wealth in Prince Edward Island. In 1875 the Island government expropriated the remaining large proprietary estates, whether owned by residents or absentee landlords, and offered them for sale in small lots.119 If Charles and Edward had established their own families, their children would not have been able to live out their lives at Morell House and sustain themselves with rents in cash, in kind, and in labour. The forces of a revolutionary age closed those options.