Forum

Female Slaves as Sexual Victims in Île Royale

1 FEMALE SLAVES WERE VULNERABLE throughout the French Atlantic world – and more widely – because owners had power and control over slaves and their bodies. Whether captured on slave ships during the Middle Passage, labouring in the cane fields of Saint Domingue, or doing household chores in the towns and villages of New France, these women were assaulted by white males and men of all ethnicities. Women’s degradation was a key tenet of slavery.1 The French Atlantic context provides some necessary background to help explain the often brutal sexual exploitation of female slaves in Louisbourg and in the outport communities of Cape Breton (Île Royale).

2 Brought aboard the slave ship and stripped of their clothing, women were restricted to the quarterdeck during the day; there they ate their meals, washed, and danced. Slave traders forced female and male slaves to dance because they believed that exercise was vital to preserve the health of the enslaved. Females often danced to the music of African instruments whereas men generally kept time to the pounding of chains on the deck.2 Many women crouched in shame in order to hide their genitals. Female slaves were not put in irons since it was believed that they did not have the physical strength to revolt and take over the ship. During the day, if weather permitted, the men were kept in irons on the main deck and part of the quarterdeck; they were separated from the women by a barricade that divided the ship. Since the women’s living quarters were below deck near the officers’ accommodations, the officers had easy access to the women. In fact, to pass from the slave deck to the quarterdeck the women had to climb stairs that passed through the officers’ cabins. Women were thus subject to sexual advances and it was typical for an officer to choose a female slave to wait on him “at the table and in bed.” Some crew members joined slaving voyages because they wanted free access to African women.3

3 Most seamen chose to believe the old European myth that African women were sexually permissive with insatiable sexual appetites. This common portrayal of black female slaves as licentious beings justified mistreatment of black women and the black race. Advocates of slavery maintained that black women simply could not be raped because they were so promiscuous.4 And ships’ officers and crew took full advantage of their beliefs. One young French officer reported that seamen usually selected favourites from among the women, giving them additional rations in exchange for sexual availability. These slaves, so the thinking went, also “adjusted better” to the journey because they bonded with the sailors.5 Another eyewitness, the captain of the Jeannette, a Nantes slave ship, allowed his sailors access to the slaves, “given the custom among them that each one should have a woman.”6

4 When female slaves debarked from the Jeannette and thousands of other slave ships in the French West Indies, they faced further sexual abuse. By the beginning of the 18th century, there were few white women in the West Indies because white males dominated the commodity production of slave plantations. Although white families had been established in the West Indies during the 17th century, the enormous growth of the slave plantation in the 18th century altered domestic arrangements and familial structures as slave mistresses and black domestic servants took the place of European wives.7 In combination with the disappearing white family, male slaves began to outnumber female slaves in Saint Domingue throughout the 18th century. The smaller number of female slaves in the white and black communities of Saint Domingue put further pressure on female slaves for sexual favours. Since female slaves had no legal standing and little status, they became susceptible to rape, sexual harassment, and some of the more sadistic forms of cruelty by whites. Unlike male slavery, female slavery had a psychophysical dimension because white men often gained sexual pleasure and gratification by inflicting physical and mental pain on enslaved women.8 The sexual exploitation of slave women by whites also resulted in a multitude of children. During the 1830s and 1840s thousands of mixed-race children and their mixed-race mothers were freed in the French Caribbean. More generally, the large population of people of Afro-European descent in the Iberian Americas provided further evidence that African women were not merely units of labour but were sexually abused by their European owners.9

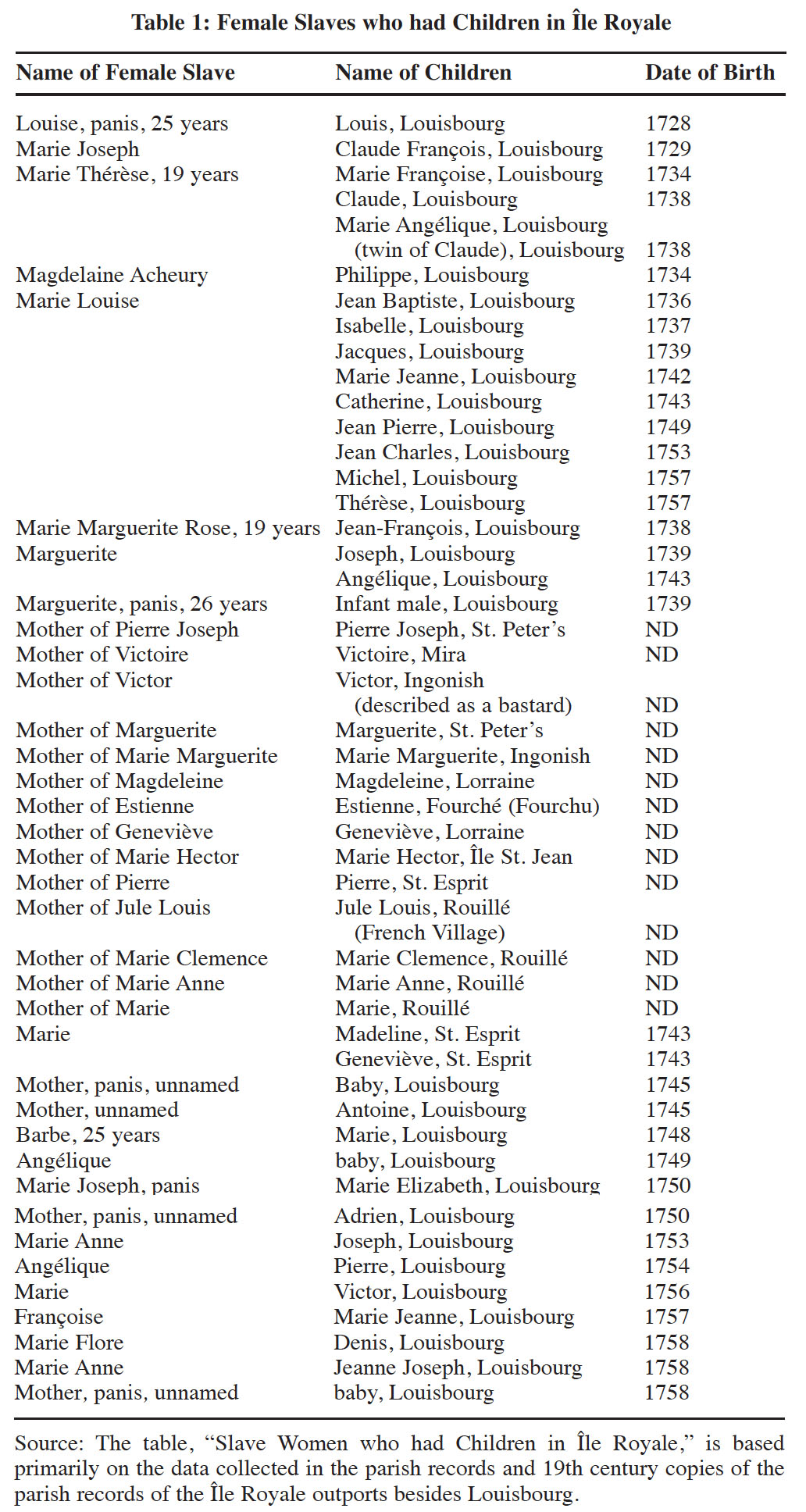

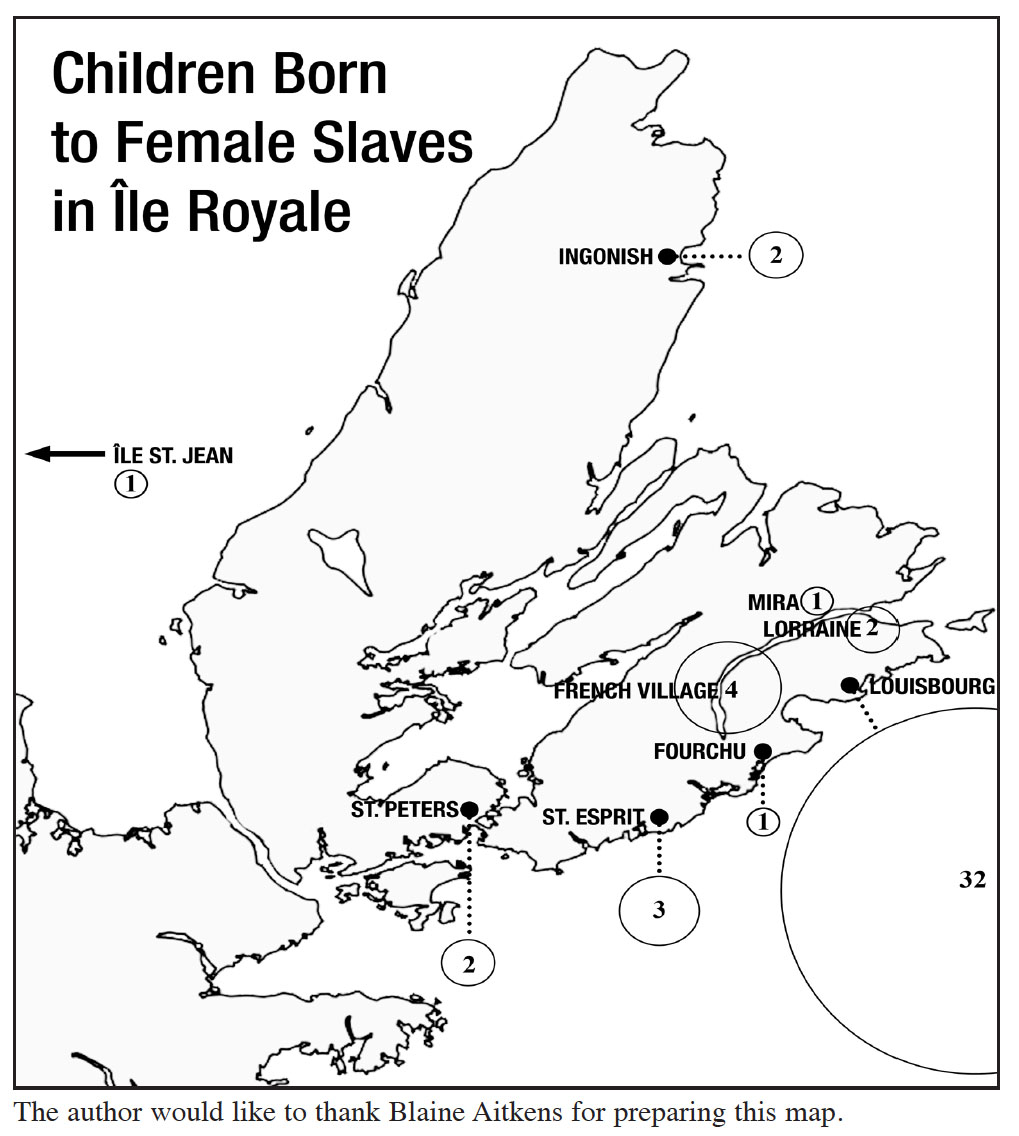

5 Whether on French slave ships or in the French West Indies, female slaves became sexual victims of whites as part of a shared culture of abuse throughout the French Atlantic World and thus it should come as little surprise that female slaves in Île Royale were subject to rape and sexual harassment. There were 70 adult female slaves in Île Royale and, like other women in service, they were vulnerable to sexual exploitation by their owners. As many as 36 of the 70 women slaves gave birth to a total of 48 illegitimate children. Thus, in Louisbourg 21 slave mothers gave birth to 32 children while 15 slave mothers in the Île Royale outports delivered 16 babies. The 34 adult female slaves who did not have children were either beyond their child- bearing years, had miscarriages, or had died as young adults before giving birth.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1 Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 16 Louisbourg’s illegitimacy rate of 4.5 per cent represented 101 children out of a total of 2,233 baptisms in the Louisbourg parish records; 12 slave women gave birth to 19.8 percent (20 of 101) of the town’s illegitimate babies. In five instances, the women voluntarily identified fathers who were not their owners, but in the remaining 15 cases the fathers were listed as unknown.10 Research from other sources, besides the parish records, has revealed another 9 slave women who delivered 10 children in Louisbourg.11

7 Whereas Louisbourg’s parish records survived intact from 1722 to 1745 and from 1749 to 1758, only partial parish records remained for the outports of Baleine, Lorraine, Little Lorraine, St. Esprit, Mira, and Rouillé.12 The parish registers for all 18 of the Île Royale outports were returned to France after the colony was taken from the French in 1745 and 1758. These records, summarized in the 19th century, included the names of the people who were baptised, married, or died. The original, detailed parish entries were subsequently lost, but the slaves were named and identified by the word “nègre” in the summaries.13

8 One of the clearest cases of sexual exploitation in the Louisbourg records involved Louise, a panis slave who arrived from Quebec during the summer of 1727.14 Louisbourg innkeeper Jean Seigneur purchased 25-year-old Louise from Captain Pierre Dauteuil in order to use her as a servant in his inn. Seigneur paid Dauteuil two barrels of red wine for Louise, and he agreed to complete the transaction the following year with two more barrels of wine. By February 1728, however, Seigneur realized that Louise was eight or nine months pregnant and therefore unsuitable as a servant in his establishment. In Louisbourg, as in France, it was customary to discharge servant girls when they became pregnant in order to avoid public scandal.15 Louise had been impregnated by her former owner and Seigneur now refused to keep her on two counts: she “gave a poor example to his family, especially his young daughters, and he could not call on her services in his inn.” 16 This was essentially the prevailing attitude to servant girls who became pregnant in France and Île Royale.

9 At the time this happened, Seigneur and his wife Marie Corporon, born and raised in Acadia, had four daughters ranging in age from 2 to 12 years. Seigneur took Dauteuil to court, claiming that Dauteuil had sold Louise under false pretences. A priest, Michel Leduff, was summoned for a private discussion with Louise and learned that, on the voyage from Quebec during the summer of 1727, when “the crew were quiet,” Louise had slept in Dauteuil’s cabin and was now expecting his child. Even though Louise was pregnant, Dauteuil had sold her to Seigneur – warning her to say nothing, but promising to return for her prior to the birth of the baby. There may have been an emotional bond or a perceived emotional bond between Louise and Dauteuil. At the very least, Dauteuil used both coercion (warnings) and promises to keep Louise silent, which suggests a multi-faceted relationship. Since she was a slave, Louise had little choice but to obey Dauteuil and had no recourse when he failed to keep his promise. As in the French West Indies, a slave such as Louise submitted to her owner’s sexual advances from a mix of “fear and hope.”17 Louise delivered her baby, Louis, on 3 April and he was baptized with Angélique, one of Seigneur’s daughters, serving as godmother. It was common in Louisbourg for young white children to become godparents of child slaves, especially within the family. Four months after the birth, Dauteuil and Seigneur appeared before a Louisbourg notary and agreed that Louise and her baby should be sold in Martinique for 600 livres and replaced by 14-year-old Étienne, who cost 650 livres.18 Upon his arrival in Louisbourg, Étienne was baptized and put to work in Seigneur’s inn.

10 Louise’s rape by Pierre Dauteuil was one of the few cases in the Île Royale archives, composed of 750,000 documents, which describes a white male owner’s sexual exploitation of his female slave.19 This is typical, because the French archival records of the 18th-century slave trade, similarly to records of Île Royale slaves, are almost entirely silent when it comes to the sexual abuse of enslaved women. In spite of the sheer number of the 1,101,000 French slaves imported from Africa to the French West Indies from 1701 to 1800, and the ready access of the officers to the women on thousands of French slave ships, there is little or no mention of women having sexual relations with white officers or seamen.20 The same is true of the French West Indies. Arlette Gautier, in her Les Soeurs de Solitude, the pioneering study of female slaves in the West Indies, noted that patriarchal relations, prevalent throughout Europe and Africa, were maintained in the French islands. Whites and male slaves, in spite of their vast differences in power, status, and class, had one thing in common: they ensured that female slaves remained subservient to them.21

11 Throughout the French Atlantic white slave owners exploited their female slaves, including the French West Indies and Île Royale. Slave women suffered and were coerced on two levels: from slavery itself and from males, whether black or white, slave or free.22 By 1730 slaves made up four-fifths of the French West Indies population and thus the French islands had “more in common” with the English and Spanish islands than with the northern colonies of New France.23 And yet the great majority of black slaves who were brought to New France, including Île Royale, were either born in the French West Indies or came to the colony after having been “seasoned” in the islands. Marie Louise, a native of Guinea, Africa, and the slave of merchant Louis Jouet, was one of the most exploited slave women in the colony. Marie had nine illegitimate children while working in the Jouet home.

12 Slave women in Île Royale were subject to abuse even in remote and isolated communities. There were at least 31 slaves living throughout the island in such communities as Ingonish, Mira, Lorraine, Fourchu, Rouvillé, St. Esprit, and St. Peters. Of the 31 slaves, 16 were children born to 15 slave women from approximately 1713 to 1758. Although the parish records for most of the outports have not survived, the fishing community of St. Esprit was an exception. Marie, a young black slave woman, for instance, lived with her owners Jean Peré and his wife Marguerite Guyon. Jean Peré had married Marguerite on 18 January 1735; she had two children by a previous marriage.24 Madelaine, the first of Marie’s two children, was born on 12 May 1743. Marie’s second child, Geneviève, was born on the 5 September 1744 but only lived seven days.25 There were at least 80 slaves baptised in Île Royale largely because there were no slave owners or plantation managers who opposed religious instruction of the slaves.26

13 Jean Peré’s sexual abuse of Marie reflected the wide chasm in power between slave and slave owner. As was typical, few records survive about Marie – her life and personality – except that she lived with one of the most powerful fishing and merchant families in Île Royale. Jean Peré came from a privileged background. His parents, Antoine and Marie Anne Peré, had moved from Newfoundland to Île Royale in 1713. Granted a fishing concession in Louisbourg in 1717, Antoine Peré was a prosperous fishing proprietor employing 40 fishermen by 1724.27 Peré died in 1727 leaving his 47-year-old wife with five dependants. Marie Anne proved to be a resourceful woman, who successfully assumed ownership of her husband’s fishing business. The total value of Madame Peré’s estate, including her fishing properties in Île Royale, amounted to 40,807 livres when she died in 1735.28

14 Whether providing a dowry for her daughters or supplying them with appropriate clothing, no detail concerning the welfare of her children seemed too insignificant. Marie Anne Peré continually wrote to her commercial agent in France requesting either material or complete suits of clothing for her children, including the future slave owner Jean.29 “Please,” she wrote her agent in Nantes on 22 December 1733, “send me whatever is necessary to make a suit of cinnamon colour for my son; jacket, vest and two pair of pants with lining of scarlet material; and all the trimmings; a hat priced about 18 livres and a wig with a bag that costs no more than 18 livres and a pair of woollen stockings, all to match the suit.”30 As part of the family’s fishing operation, Jean Peré employed 25 men in the winter and summer fishery at St. Esprit, a fishing village 20 miles southwest of Louisbourg. By 1735 the Peré family employed an additional 37 fishermen in Louisbourg, including George, a slave, who was a fisherman.31 Jean Peré and his siblings, reared in a slave-owning household, went on to buy slaves for their own households. Jean had three slaves by 1744 and his sister Jeanne (married to Louis Jouet) eventually owned 17 slaves.

15 The exploitation of Marie by Jean Peré, and Louise by Pierre Dauteuil, had universal characteristics that went beyond boundaries, time, and space in all colonies with slaves. Annette Gordon-Reed, in her award-winning book The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family (2008), offered some provocative insights on the question of sex between enslaved women and white men. Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), the third president of the United States (1801-09) and the principal author of the American Declaration of Independence, inherited 150 slaves from his father and father-in-law and had more than 150 slaves when he penned the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Over the course of his life he had a total of more than 600 slaves.32

16 Sally Hemings, one of those 600 slaves, had six illegitimate children by Jefferson. Gordon-Reed maintains that it was impossible for Sally to give permission for sex since there was a “state of war” between masters and slaves. Hence, no enslaved woman “would ever have wanted to have sex with any white man. Faced with white men who showed interest in them, enslaved women, for completely sound ideological reasons, would be unwilling. Evidence that sex took place between the two – a child for example – would itself be evidence of rape.” Only male slaves, according to Gordon-Reed, were acceptable as female slave sex partners because men of African origin shared the same legal status and the same race. By combining years of analytical research with historical imagination, Gordon-Reed attempts to understand the thinking of Sally Hemings and all enslaved women. She concludes that all female slaves, given a choice, would have avoided sex with white males.33

17 This radical historiographical perspective maintains that all slave women were placed in a compromised position, powerless against their male white owners. Marie thus had no lasting appeal to Jean Peré other than as a sexually attractive young woman. She was expected to do all of her chores during her pregnancy, much like pregnant slave women on plantations in the French West Indies and all places where slavery was legal. Marie’s work during her pregnancy may have contributed to the death of Geneviève, her second child, who died on 12 December 1744 just seven days after her birth. Marie, a young slave mother in St. Esprit, was powerless in comparison to Jean Peré, her brash and confident owner. Were all female slaves in Île Royale and beyond as vulnerable as Marie? There is a growing body of historical research and literature on slavery, rape, and sexual consent that suggests female slaves had cards to play – that they were able to use their sexuality to gain favours such as improved living conditions from whites. By acquiescing to sexual relations with their masters, other whites, and fellow slaves, enslaved women might be able to obtain rewards for themselves and their children and sometimes even win their freedom.34

18 Besides Marie and the women of African descent, there were at least six panis enslaved women who were sexually abused by white males (five of whom were their owners) and who had children in Louisbourg. Françoise, a member of the Michel Dumoncel’s household, was baptised to great fanfare on 4 June 1754, with eight witnesses signing her baptismal certificate. Dumoncel, a successful merchant, and his wife Geneviève Clermont had lived in Louisbourg since 1733 and had six children by the time they purchased Françoise in 1754. The elaborate baptismal ceremony, together with his wife and six children, who were present at the ceremony, did not prevent Dumoncel from impregnating Françoise, who delivered baby Marie Jeanne on 9 May 1757.35 Françoise doubtless had a son by Dumoncel as well, because there was an anonymous male who died when the Dumoncel family debarked at La Rochelle on 28 April 1759. As was customary when a slave had a child, the name of the father was not mentioned in the baptismal records. Marie Anne, another panis, shared much the same fate as Françoise; purchased by Louis LaGroix, another prominent Louisbourg merchant and his wife Magdelaine Morin, Marie Anne helped to look after the three young LaGroix children and had her own child, Jeanne Josephe by LaGroix, in 1758.36

19 Slaves such as Marie Anne and Françoise had children by their slave owners and yet the families remained intact because the wives ignored their husbands’ sexual abuse and continued the pretence that all was well. David Eltis has examined “Gender and Slavery in the Early Modern Atlantic World” in his book on The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas (2000). An expert on the transatlantic slave trade, Eltis concluded that the nuclear family and European serial monogamy were not endangered by slavery in the Americas in spite of the European dominance over Africans: “European settlers in the New World did not reshape European norms in family and sexual conduct whether they were living in predominantly slave or predominantly free societies.”37 The same pattern held true in Île Royale. Of the 277 French slaves in the colony, there were 70 adult females who served as domestic servants and nannies and who helped mothers cope with the stress of bearing children. Although these enslaved women assisted young mothers, they were vulnerable to sexual assault and 36 of them bore illegitimate children. Skin colour did not matter in terms of white males’ sexual desires. Slave life in Île Royale was shaped by the history and culture of the island, yet it also reflected the lives of slaves throughout the French Atlantic world where racism and slavery went hand in hand. The wives in Île Royale and other French slave colonies looked the other way and preserved harmony within their families, and the abuse of slave women continued unabated.