Forum

Archaeology and Atlantic Canada’s African Diaspora

1 “SANKOFA” IS AN AKAN WORD FROM AFRICA and, in its most basic form, means “return and get it.”1 That is what archaeologists do – return to the places where people lived to get the pieces, and the stories, they left behind. For black people in the Americas, the stories available through the democracy of the archaeological record are inimitable records of their ancestors’ perspectives on life. We archaeologists return to get their stories yet unheard.

2 Black Atlantic Canadians should not be categorized as being descended from slaves. They are descended from Africans and their children, many of whom were enslaved – but not all. These people came from and created rich, dynamic cultures steeped in heritage and tradition. Throughout the African diaspora, individuals further developed and strengthened their regional identities, which, in this region, gave rise to the Black Atlantic Canadian culture that is here today. Unlike in the United States, the Caribbean, and South America, where archaeological research of African traditions and culture on black sites has been well-explored for upwards of 30, 40, or even 50 years, there has been a shameful lack of black archaeology in Canada. The most notable exceptions have been the Underground Railroad work in central Canada and work in Birchtown, Nova Scotia, the latter initiated by the threat of a landfill on an area known to Black Loyalist descendents as a former area of their ancestors’ settlement and now a forested hinterland.2 The bottom line, however, is that archaeological research of the African diaspora in Atlantic Canada is only recent, and it has focused on sites in Nova Scotia to the veritable exclusion of the other three provinces in the region. Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, and New Brunswick remain in need of theoretically grounded archaeological investigation of their African diaspora culture and heritage.

3 My doctoral dissertation focused on Black Loyalists as a significant segment of Atlantic Canada’s African diaspora heritage.3 The research explored whether threads of African cultural heritage continued to be woven into the culture of these Africans and their descendants as they made their homes in Atlantic Canada and became Black Atlantic Canadians. I approached the archaeological data using an Africentric interpretive perspective in my analysis of the objects, their immediate contexts, and the cultural landscapes in which those contexts were understood. Such an approach conforms to a body of academic thought labeled standpoint theory, a recent development in theory discourse. Essentially, an Africentric theoretical approach prioritizes the African or African-descended explanation of data from an African diaspora site or the African diaspora layer (interpretive or cultural landscape layer, not physical layer) of a multicultural site rather than the Eurocentric explanation. For example, many blacks throughout the Atlantic World used ceramic dinner settings that were manufactured in England. The European manufacturers intended these items to be used for eating foods from a typical Georgian meal of meat, potatoes, and vegetables – all separated on the individual’s plate – thereby making the plate the central piece of the setting. For many African diaspora individuals, whose cultural background may have been more heavily influenced by their African heritage, the bowl would have been the central piece of the set, as stews and similar potage-type meals were the more common meal type in an Africentric diet.

African diaspora archaeology elsewhere

4 From African diaspora archaeology conducted outside of Atlantic Canada, we know that certain objects in certain locations in past landscapes bespeak African diasporic cultural behaviours.4 Particular items appear again and again in archaeological excavations that, without Africentric interpretation, would be discounted as garbage or detritus. These include crystals or “flashy” glass, blue beads, pierced coins, seemingly out-of-place marine shells, pipes, objects with “X”s on them, handles cut off of utensils, copper-alloy objects, bones, cutlery, white saucers (or fragments of them), nails, iron, and white chalk or similar material. These items of conjure – tools with which users can summon or invoke spiritual power to impose their will – are frequently found in northeastern corners of rooms and buildings, often embedded in structures as they are built or renovated; but the pattern discernible at an inter-site scale of analysis indicates that the placement was purposeful. The broader African diaspora archaeological discourse has also taught us that some African diasporic people consumed goods differently than white Euro-colonial people. African diaspora individuals, for example, often bought tinned, controlled food – at least in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – as opposed to locally derived foods since quantities and qualities of tinned food could not be easily altered by the seller for prejudicial reasons.5 Some archaeologists have suggested that in the Bahamas enslaved blacks selected ceramics whose decorative colours reflected palettes similar to those seen in African textiles, a major commodity for West Africans in displays of wealth and fashion.6 Further, the segregation of settlement areas is not unique. Cultural neighbourhoods or cultural-majority communities are a fact and are furtive ground for cultural integrity and transmission. The next step in analysis draws from African diaspora discourse emergent from studies of resistance and oppression, largely on plantations. This methodology attempts to grasp how landscapes and spaces were understood by African diasporic people. The most recent discourse, however, has viewed African diaspora landscapes as active and positive as much as, if not more than, reactive and secondary to a hegemonic landscape. For example, yards were swept clean to bare earth as an African cultural choice rather than keeping a bare yard surface because of a lack of opportunity to grow a lush, grassy lawn. The difference resulted from preference as opposed to consequence.

African diaspora in Atlantic Canada

5 In Atlantic Canada, however, African diaspora archaeology has only recently begun to expand – primarily, if not solely, in Nova Scotia. Theoretically grounded academic archaeological research has been conducted in recent years, much of it focused on data from Birchtown: explorations of architecture, spatial analysis, and overall site history. Smaller research projects have been conducted, including a cemetery along Nova Scotia’s eastern shore that had to be moved due to coastal erosion, a survey in Antigonish and Guysborough Counties, work to prepare for the reconstruction of the Africville Church, and occasional commercial archaeological impact assessment projects in advance of developments. The most recent projects are two doctoral research programs: my own and that of my colleague Catherine Cottreau-Robins. Certainly, historical research of black history in Atlantic Canada has seen increased activity and many of the archaeological projects that have been undertaken in Nova Scotia rely on historical research to help plan the fieldwork and expand the local archaeological discourse. As part of that expansion, however, we must see the other three Atlantic provinces tapping into their archaeological records and exploring their own African diaspora archaeological resources. In so doing, the investment of effort into historical research goes that much further.

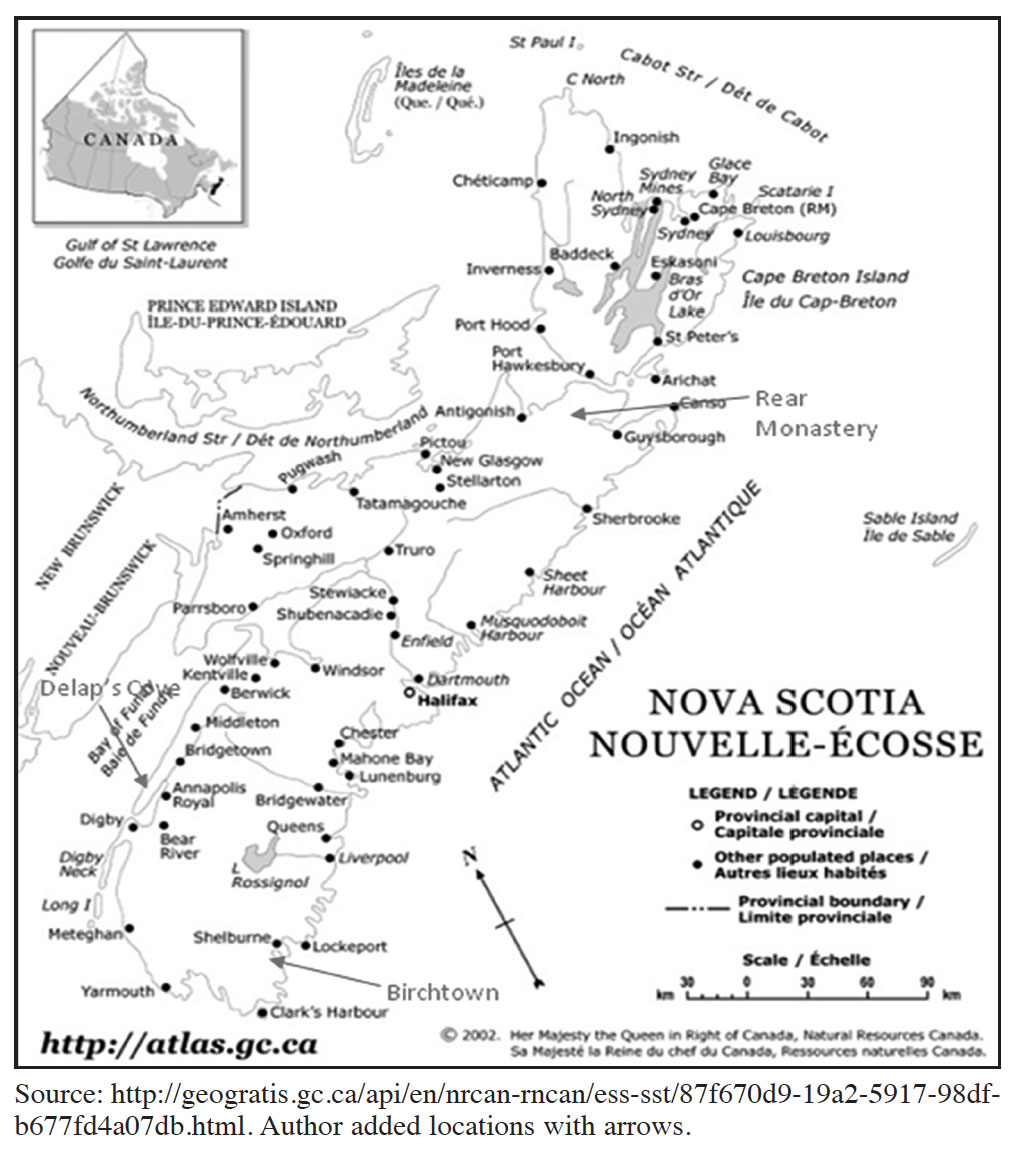

6 My own doctoral research used data from four communities in total, three of which are African-Nova Scotian: Birchtown in Shelburne County, Delap’s Cove in Annapolis County, and Rear Monastery, which bridges Antigonish and Guysborough counties.

7 The fourth community, Coote Cove, was not a black site; it was settled by Irish immigrants and was roughly contemporary with the earlier periods of the black Nova Scotian sites in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Coote Cove was used in the research to keep in check the inclination to rely too heavily on ethnicity-based explanations when the explanation may derive, rather, from economic or social position. As with enslavement, being black or a member of the African diaspora was just one part of people’s lives and identities; it was not the totality of their being: they were mothers, fathers, children, poor, well-off, community leaders, and so forth. The Irish who settled at Coote Cove shared the characteristic of poverty with many 18th- and 19th-century black Atlantic Canadian settlers. Including a non-black community that was impoverished was meant to help explore the extent to which finances, as opposed to ethnicity or cultural heritage, were responsible for consumption patterns evident in the African Nova Scotian archaeological samples in this study.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 28 To explore the degree of Africentrism within Black Atlantic Canadian cultural heritage, I considered three primary areas of inquiry: cultural landscape, aesthetic consumption practices, and magico-religious traditions. I considered cultural landscape at inter- and intra-community levels as well as at the household level. For aesthetic consumption practices I explored the decoration of ceramic wares, specifically decorative colours and motifs. These elements were selected based on their potential to reflect an Africentric colour palette or design style, as per Laura Wilkie and Paul Farnsworth’s conclusions in their study of Bahamian identity. 7 The magico-religious traditions were initially to be considered only as a presence or absence study through test excavation of specific contexts that have proven on other African diaspora sites to contain material assigned religious or magical significance in Africentric ritual practices. African diasporic systems frequently reflect religious traditions and belief systems of African cultures. Gospel music is undeniably unique and African-descended in its tone, message, rhythm, and performance. Vodun, Voodoo, and Hoodoo are systems of belief, folklore, healing, and sociopolitical action widely recognized and established in the Americas and firmly grounded in African practices. The experience of slavery and the presence of African-born peoples, living both enslaved and free, amplified the potential for African-derived spirituality to endure and metamorphose throughout the diaspora. Initially, I had not expected to find anything related to such practices here in Atlantic Canada despite a commitment to examine northeastern corners of house features and rooms, hearths, and thresholds. This was likely because nothing had been identified as such in earlier work on African Nova Scotian sites as well as the dismissal by other local and seasoned researchers that there was anything identifiably unique about African Nova Scotian settlers other than skin colour. I was surprised and delighted to find items that, with adoption of an Africentric-interpretive approach, might indeed be evidence – like that from the United States, Caribbean, and South America – of African-derived magico-religious practices for healing or spirituality. Interpreted collectively, the objects from Rear Monastery offer a new perspective on African diasporic material culture in this region. As such, this interpretation is not yet definitive. Additional quantification is necessary to support it. The data’s presentation and explanation is an exercise in how understanding might advance in Atlantic Canada if consideration were given to interpretations that contextualize the data from this region’s black past within the larger picture of the African diaspora. The next step will require researchers either to challenge the interpretation through systematically defined negative evidence or to expand it through quantification at other sites.

Black Atlantic Canada

Nova Scotia

9 Black history in Atlantic Canada extends back, roughly, as far as that of European peoples’ settlement history. The first historical record of a person of African descent here is of Mathieu Da Coste, who it is believed was the language interpreter for Samuel de Champlain and his entourage at Port Royal in 1605.8 A year after the first record of Da Coste, there is another record of the death of a black person from scurvy circa 1606-07.9 In any event, the documentary record alone proves that black history in Nova Scotia is at least 400 years long. While Da Coste was a free man, the enslavement of African peoples in Atlantic Canada by those of European extraction may have a history just as old – perhaps in the seasonal fishery.

10 Historical research has shown that African diasporic peoples, both enslaved and free, were among those who built Halifax, established in 1749. Citadel Hill, the most prominent terrestrial landscape feature of the city, was the worksite for many of Halifax’s early black settlers.10 Slave auctions were held on the early town’s waterfront by Joshua Mauger, who advertised in the same newspapers where runaway slave ads indicate enslaved people’s resistance to the imposition of the condition of enslavement.11 Following the Acadian Deportation, when English settlement was encouraged across the Nova Scotian landscape by settling New England planters on the former Acadian farmsteads, blacks enslaved by those planters further expanded the slave society in Atlantic Canada.12 The New England planters engaged in agriculture on the fertile lands of Nova Scotia’s rolling plains, not-so-rocky shores, and reclaimed saltmarshes with the aid of their enslaved blacks, though not on the scale of the agricultural plantation slavery of the American southeast. This influx of Africans into Nova Scotia was followed by one event that, perhaps, must stand among the most influential events in the history of the African diaspora in North America and the Black Atlantic – the landing of the Loyalists and their servants in Nova Scotia. More than 10 percent of them, numbering more than 3,000, were of African descent (the Black Loyalists). It was a new social, political, and racial frontier they encountered in Atlantic Canada, where they were free British subjects living, en masse, beside their European equals.

New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island

11 To begin the archaeological search for the African diaspora in these less-considered provinces, the geographic starting points may be Loch Lomond, outside of Saint John, and “The Bog,” a community on the historic boundaries of an earlier version of Charlottetown.13 These black communities, like Africville or Preston, were enclaves near or amidst the urban settlements where whites predominated. Urban sprawl may have claimed the traces of much of these communities, but it is the archaeologists who can return and obtain evidence of the lives lived there.

Newfoundland

12 On the island of Newfoundland, black presence is, so far, indicated through archival documents and has been neither sought nor identified archaeologically. Slave societies clearly existed in the early settlements on Newfoundland. A 17th-century letter to Charles II from Thomas Oxford of St. John’s records a “Negro Servant” among Oxford’s property in the 1670s.14 A late-17th-century merchant’s ledger from Plaisance, the fortified French stronghold on the Avalon Peninsula known today as Placentia, records the sale of cotton to a local planter “pour sa negresse” or “for his black woman.”15 The time was 1677, nearer the beginning of French occupation of this settlement in 1662 than its end in 1713. Further research may reveal a notable black presence in historic Newfoundland as these disparate references converge into a nascent narrative. F.L. McGhee’s recognition of links between the African diaspora and maritime archaeology through whaling, fisheries, and other commercial seafaring activity can be extended to Atlantic Canada.16 Given the role of the fishery, the sea, and Atlantic World commerce in Newfoundland’s history, it was likely that the black presence in Newfoundland’s history was more extensive than we currently understand.

13 As the French left Plaisance to establish Louisbourg on Île Royale (Cape Breton) following the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), the governor of the colony, Pasteur de Costebelle, brought with him Georges, his recently purchased enslaved 16-year-old African boy.17 Costebelle seems to characterize the trend for Île Royale’s early French residents, which has been examined in greater detail by Ken Donovan. Donovan further notes that there were 381 people enslaved in Cape Breton between 1713 and 1768, 277 among the French and 104 among the English. Most of these black slaves lived in Louisbourg. In terms of archaeological research, the enslaved population of Louisbourg holds a great deal of promise if only the archaeologists look for the evidence left by members of the African diaspora and are able to recognize potential Africentric material in the data as they uncover it – at both Louisbourg and Plaisance.18

14 A century following the French and African emigration from Plaisance to Louisbourg, likely during a fishing expedition, the body of a man of African descent was interred on the shore at L’Anse au Loup, Labrador, wearing typical English garb for the time and bearing the initials “WH” carved into the sole of his leather shoe.19 It seems there are instances of black presence in many parts of present-day Atlantic Canada.

Conclusion

15 The search for African-descended traditions is waning in other parts of the diaspora, partly because the idea that Africentric traditions existed and were transformed has become an established principle within the discourse on African diaspora archaeology. There is also agreement that interpretations of black sites and material culture data need to be informed by Africentric perspectives. In response to this early volume of investigation, research has advanced to more theoretical and sophisticated questions of identity formation, gender, consumerism, landscape, and the intersections of these belonging to various cultural groups and the ways in which these intersections happened. We are not yet at that point in Atlantic Canada, but we have both the potential and, I suggest, the responsibility to get there. This will only happen as others undertake archaeological research on African diaspora sites in Atlantic Canada and adopt an Africentric interpretive perspective, especially when analyzing data from a multicultural site of black presence.

16 Although some might argue that the work to the south of Atlantic Canada is sufficient for Atlantic Canada to understand its African diasporic past, such a view denies the regional identity that characterizes Atlantic Canada as a distinct location in the Atlantic World – even in comparison with nearby New England. Harvey Amani Whitfield’s work testifies to the importance of this latter point. Atlantic Canada occupies a unique position in the landscapes of the Atlantic World, the African diaspora, the Black Atlantic World, Canada, and northeastern North America. This unique position has fostered a distinctive cultural incarnation, and it is deserving of its own investigation and explanation based on its own evidence. Specifically, while the African diaspora of Atlantic Canada is strongly related to larger patterns, local identity is critical and black Atlantic Canadians deserve to know their past and integrate it with their own sense of identity as much as any other cultural or ethnic segment of this region’s population.

17 Archaeologists have only recently begun to consider blacks as detectable in the archaeological record of multi-ethnic sites, and their limited work has not extended to sites in Canada’s Atlantic region from the 17th century. Historical archaeologists now have the opportunity to develop this nascent understanding and to investigate the African diasporic people throughout the Atlantic Canadian region. The pieces of African Atlantic Canadian heritage must be researched and seen as fertile ground for African cultural substance throughout Atlantic Canada. African diasporic lives, realities, and perspectives in Atlantic Canada’s history are most accessible through the discipline of archaeology. Archaeology takes on all the greater significance because black people in Atlantic Canada, as in other regions of the Atlantic world, were kept on the margins and received little attention in the traditional historical records. Black people came to this region from all over the Atlantic World and created a unique, African diasporic cultural position. The challenge now is to ascertain and to uncover that layer of the region’s history that is Black Atlantic Canada and to weave it into its rightful place in the fabric of the Atlantic World’s African diaspora.