Articles

The Quest of the Volk(swagen):

The Bricklin Car, Industrial Modernity, and New Brunswick

Three thousand Bricklin cars were built in New Brunswick between 1974 and 1976 with government support before the company went bankrupt. This article examines the Bricklin as an idea of industrial modernity, reflecting a long-standing thread within national policies around the world linking the emergence of a successful automotive sector to economic and political maturity. It shows how politicians, policymakers, and the media attempted, through Bricklin, to shape collective and regional identity in order to achieve an industrial modernity that was associated with car manufacture. Bricklin was far more than a simple car company – it was an attempt to reshape the very idea of a province.

Entre 1974 et 1976, 3 000 automobiles Bricklin ont été fabriquées au Nouveau- Brunswick avec l’aide du gouvernement, avant que l’entreprise ne fasse faillite. Cet article s’intéresse à la Bricklin en tant que conception de la modernité industrielle, qui reflète une constante de longue date parmi les politiques nationales partout dans le monde, soit le lien qu’elles établissent entre l’émergence d’un secteur automobile prospère et la maturité économique et politique. Il montre comment les politiciens, les décideurs et les médias ont tenté, par l’entremise de la Bricklin, de façonner l’identité collective et régionale en vue d’atteindre une modernité industrielle qui était associée à la fabrication d’automobiles. La Bricklin était beaucoup plus qu’une entreprise de fabrication d’automobiles; c’était une tentative pour refaçonner l’idée même de province.

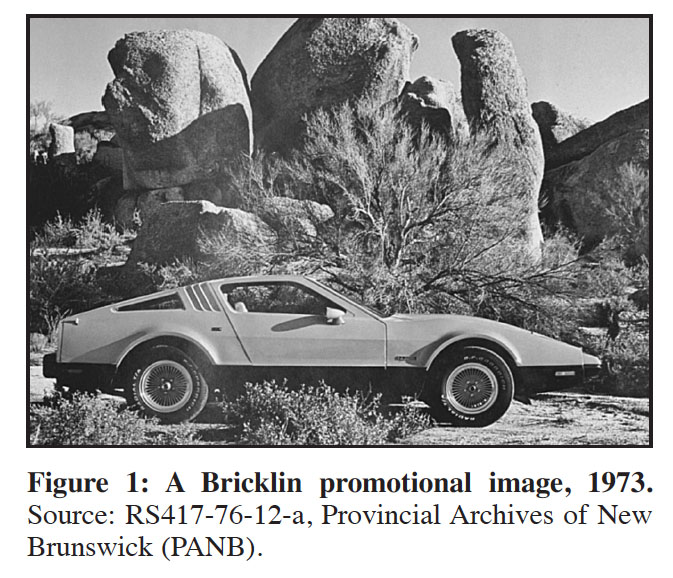

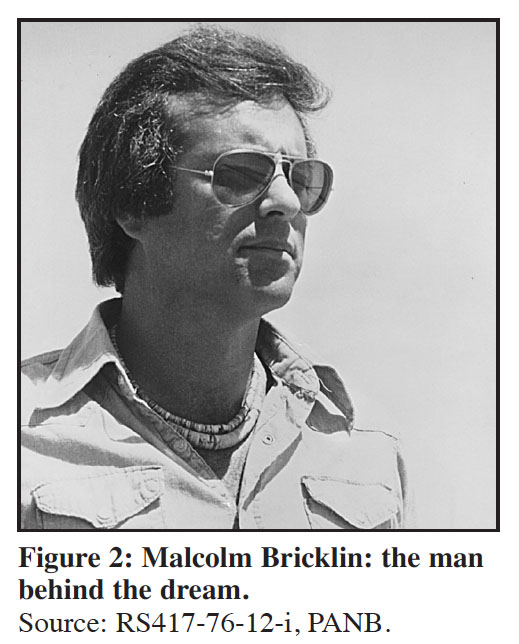

1 MALCOLM BRICKLIN, A YOUNG, CHARISMATIC, SELF-PROMOTING American automotive entrepreneur who was best known for bringing Subaru cars to the United States, announced to great acclaim in 1973 that he was going to build a dazzling new vehicle, the Bricklin SV1 (SV standing for Safety Vehicle). The “Bricklin,” as it was to be known, was going to be the latest, greatest sports car. Promoted as a technological and engineering marvel, the car would have “gull wing” doors, acrylic body panels, and the most innovative safety features (including a “safety frame,” roll cage, and above-average bumpers). Bricklin, a consummate showman, immediately launched a massive public relations and advertising campaign, appearing on numerous American television shows, in magazines, and the trade press. The response was enthusiastic, and Bricklin was heralded as a throwback to a bygone era: the last great automotive entrepreneur and a rags-to-riches story of American know-how and individualism, akin to a Henry Ford or Walter Chrysler. By 1974, the car’s distinctive image was entrenched in the North American collective consciousness. Bricklin and his cars appeared on the Today Show, in an episode of the hit American television comedy Chico and the Man, in Playboy and People magazines, and were featured prizes on popular television game shows such as The Price is Right and Let’s Make a Deal.1

2 To the surprise of many Canadians, Bricklin announced that the vehicle would be built in, of all places, New Brunswick. He had decided upon the province for the site of his new auto-building venture after striking an agreement with the Progressive Conservative government of Premier Richard Hatfield. Hatfield, recently elected, saw in the Bricklin project a means of vaulting his province, which some saw as an industrial backwater, into the first rank of car-producing regions. Enraptured by the idea of building a sexy sports car in New Brunswick, the Hatfield government granted Bricklin millions in loans and facilities, and eventually took a majority ownership stake in the company. Bricklin, like a number of other projects in the region during this period, represented a yearning for an industrially modern economy in the Maritimes. This was an impulse as powerful – if not more so – as any desire for a tourist economy based on tradition or nostalgia. Bricklin would mean jobs for New Brunswickers, an influx of investment, industrial and economic development, and, perhaps just as importantly for Hatfield, a new respect for his province. With Bricklin, New Brunswick could transform itself into a new Detroit or, at the very least, a Windsor or Oshawa in Ontario.2

3 Instead, Bricklin and Hatfield’s dreams quickly turned into a nightmare. The firm’s shortcomings – poorly engineered cars, lack of experience, and corporate disorganization – crippled the company. Bricklin had also greatly underestimated the cost of launching a new vehicle. Nor did it help that the tumultuous 1970s auto market lurched from one regulatory or gas-price crisis to the next – a difficult situation for any carmaker, let alone a new entry into a highly competitive marketplace. 3 In the fall of 1975, after building nearly 3,000 cars, Bricklin was unceremoniously put into receivership when the New Brunswick government, which by then owned 67 per cent of the company, pulled the plug. The province had poured nearly $20 million dollars into the project. Hundreds of workers were left unemployed, and Hatfield would spend years attempting to escape the political taint of the Bricklin debacle. For his part, Malcolm Bricklin endured ignominious bankruptcy court proceedings in his home state of Arizona. Instead of transforming New Brunswick into a new Detroit, Bricklin became famous as a cautionary tale of entrepreneurial hubris, state intervention in the economy, and the difficult realities of carmaking in the era.4

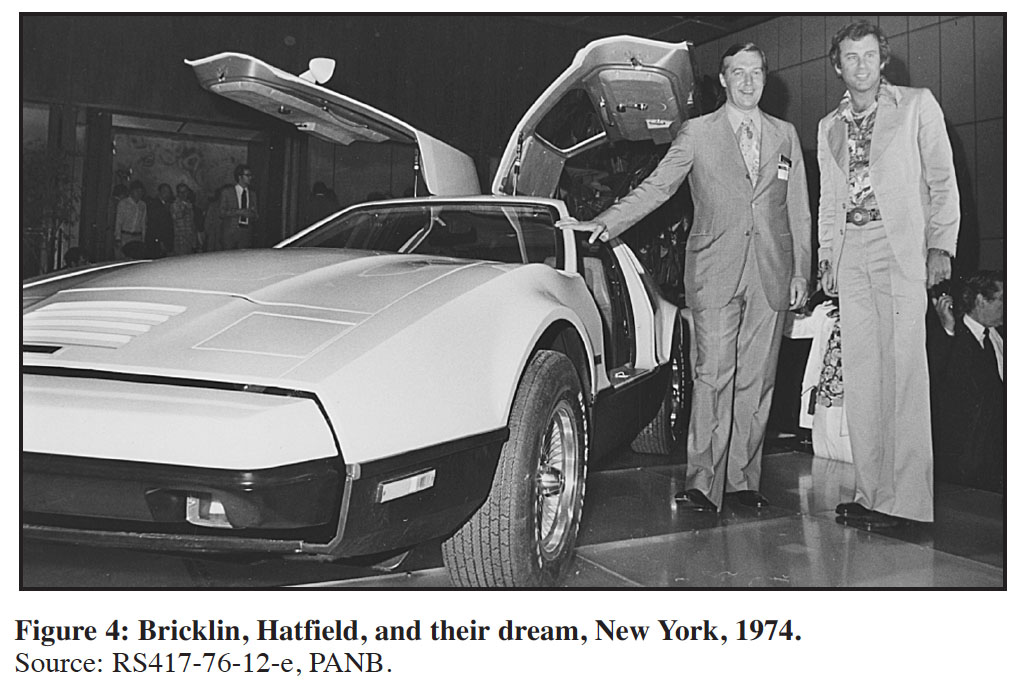

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 14 Why did Hatfield and New Brunswick take the chance on what seems, in retrospect, such a risky venture? The auto industry was (and remains) the highest-profile, most-demanding, and most-competitive and technologically advanced industrial sector on the planet. What made Hatfield think that starting an auto industry in New Brunswick was a reasonable possibility? Certainly, jobs, investment, and development drew him to the project. But the answer also lies, in part, in the allure of the auto sector as the pinnacle of what can be referred to as “industrial modernity”; having a car industry was seen, especially in the post-1945 period, as the essence of industrial maturity, technological ability, and international economic status.5 Hatfield was willing to take the chance because in Bricklin he saw an opportunity to recast New Brunswick’s image and economy – a chance to capture some of the glory represented by the modern automobile and its industry.

5 Building Bricklins in New Brunswick was about more than just jobs or investment. It would allow the province to cloak itself in the modernity, newness, and technology represented by the automobile. Doing so would break off the shackles of what was seen as an industrial backwardness and second-class status within Canada. This was particularly true in terms of New Brunswick’s relations with Ottawa, central Canada, and what Hatfield perceived to be central Canada’s prejudicial capitalist class – one that looked down upon the Atlantic Provinces. More than just another economic development venture, Bricklin represented a new beginning for New Brunswick – one embraced by so many nations and regions in the post-war period as they sought to achieve industrial modernity.

6 In interpreting the Bricklin episode, this article has three interconnected aims. First, it provides a brief contextual background and the argument that the Bricklin – despite its later status as a cultural touchstone for failure – could reasonably have been regarded initially as a realistic venture. Second, the article explores the notion of the automobile as an idea of industrial modernity. It examines how New Brunswickers imagined the Bricklin and its impact upon their province, and especially the views of Premier Hatfield and his government – highlighted by the so-called “Bricklin election” in 1974. Finally, an effort is made to draw broader meanings out of what the Bricklin episode can reveal about New Brunswick, modernity, and the automobile. The aim here is not to outline the entire story of Bricklin in New Brunswick or the reasons for its eventual failure, but to explore some of the ideas and currents that underlay and help to explain why Hatfield and his province were willing to take such a chance on what, in hindsight, seems to have been such a dicey proposition.6

The Bricklin story

7 Looking back it is easy to scoff at the notion of the potential success of Bricklin, or that the idea of a car company in New Brunswick was even remotely realistic. Given what we know now, Bricklin seems absurd – a dream destined for inevitable failure. And time has not been kind to the Bricklin. If it is remembered at all in the cultural consciousness, it is as a shorthand for 1970s excesses – a type of post-modern, post- embargo Edsel.7 Books such as How to Brickle (1977) made a mockery of the car and the whole episode, as did songs such as Charlie Russell’s “The Bricklin” (1975), whose chorus went:

Is it just another, wait an’ see

We’ll let the Yankees try it

An’ holignee to God they’ll buy it

Let it be dear Lord let it be. 8

For automotive aficionados, the Bricklin regularly appears on lists of the worst cars of all time, and the commentary attached to the vehicle is usually brutal in its assessment.9 So unserious is the notion of the Bricklin that a musical comedy recently premiered in New Brunswick to rave reviews: The Bricklin: An Automotive Fantasy portrays Bricklin as a suave and swashbuckling American, with Hatfield in the role of the earnest yet ambitious provincial who sings songs such as “High Risk Venture” and “Keep it Under Your Hat” (the riskiness of the venture, that is).10 The car has become, like its far-more-famous gull-winged doppelganger, the DeLorean, something of a joke and a cultural punch line for failure.

8 But this was not the case, at least initially. The idea of a sexy new sports car – and especially the car itself – were not considered a joke when Bricklin held a glitzy 1974 launch of the vehicle in New York City’s Four Seasons ballroom. With Broadway crooner Sammy Kahn singing “The Most Beautiful Car in the World,” (instead of “girl”) as an added touch of publicity, the car received largely favourable reviews. The Bricklin’s rakish appearance, and the promise of making a virtue out of “safety” – an issue increasingly on the minds of American consumers in the early 1970s – generated genuine optimism about its potential and a remarkable amount of media attention. Many observers heralded the car as a breath of fresh air in an automotive world bedeviled by regulations, gas shortages, and bland styling.11

9 Moreover, the potential sales of such a car were considerable. When Bricklin had first announced the idea of a new high performance vehicle two years earlier, the size of the sports car market in America was massive and growing; Bricklin set his sights solely on the American car market; sales in Canada were an afterthought. By the mid-1970s the Mustang and Camaro “pony cars,” which had so enticed the first wave of baby boomers in the 1960s, were still selling hundreds of thousands of vehicles each year. Bricklin’s aim to slice off a fraction of that market was not at all unreasonable at the time, and many auto observers welcomed the competition that the car represented.12 After all, others had already recognized the potential for sports car sales in America. Japanese manufacturers had successfully entered the market with cars such as the Nissan/Datsun 240Z (introduced in 1970), followed by the RX- 7 at the end of the decade. Both vehicles had done very well, and reflected yet another example of the audacity of the “Japanese invasion” of the US auto market. For many American car-enthusiasts, the Bricklin represented a classic American response to the challenges posed by the Japanese – an individual tale of innovation and ingenuity that could reclaim America’s sports car crown.

10 Designed by well-known auto stylist Herb Grasse, who had worked at Ford and Chrysler before being hired by Bricklin to visualize his new “safety vehicle,” the car was sleek and attractive. Most notable were the gull-wing doors, which provided an element of innovation and unorthodoxy for a mass-produced vehicle (only a tremendously expensive 1954-57 Mercedes-Benz had such doors). Powered by hydraulics, the doors kept the car low to the ground, and helped to create a futuristic image of speed. Playboy magazine gushed that the Bricklin had a “gutsy, don’t- tread-on-me look about it, somewhere between a Datsun 240Z and a Maserati Ghibli, with Mercedes 300SL-like wings thrown in for good measure.”13 The Bricklin promised to be a technological and stylistic marvel.

11 Captured by its appearance, and its safety and performance potential, contemporary observers in the auto industry were indeed enthusiastic about the Bricklin. Car & Driver’s September 1973 cover story trumpeted “The Best American Sportscar: Bricklin or Corvette? (The Answer May Surprise You).” Road & Track declared: “From what we have seen of the car so far we have to think that the future of the Bricklin is a bright one, but only time and sales will tell.”14 This enthusiasm spilled over to the members of the car-buying public, whom also seemed keen on the Bricklin. As late as September of 1975, Mechanix Illustrated published an article entitled “We Test the Amazing Bricklin” that overlooked the car’s persistent quality problems and enthused that “we look for the ’76 and ’77 models to show even better craftsmanship and design development.”15 Even as the company went under in the fall of 1975, whatever Bricklins were coming off of the production line in New Brunswick were being sold as soon as they shipped. In fact, every single Bricklin produced had a buyer, and even in receivership the company had a backlog of orders for the car. The Bricklin was, initially, a success at least from a sales and marketing perspective.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 212 Behind it all was the man himself, Malcolm Bricklin. Bricklin was the classic American success story. He had first found fortune in the hardware store business, becoming a millionaire by his mid-twenties. In the late 1960s, Bricklin got involved in the motor-scooter business, and then moved onto the auto industry. This pursuit reflected his brash personality. In January of 1975 the Saint John Telegraph Journal, a paper that had intimately followed the Bricklin story, pegged him perfectly: Bricklin was “a dreamer, a promoter and an entrepreneur. He is imaginative, confident, cocky, and he just plunge[s] ahead. He doesn’t believe in looking back.”16

13 Bricklin had envisioned the car, put it into production, and had orchestrated the massive and successful publicity campaign that had resulted in such an initial burst of enthusiasm. How had he managed it? After all, others had already failed where Bricklin dared to tread, and launching a new automobile – for all the opportunities that the marketplace had to offer – was an incredibly risky, costly, and daring act. The North American auto industry had, since the 1930s, operated as an oligopoly, with the Big Three of General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler dominating sales with over 90% of the market. Indeed, after the 1960s, when the Big Three had essentially squashed much smaller competitors such as Nash and Studebaker, only the American Motors Corporation remained as an “independent.” By then the cost of a new vehicle launch was often in the tens of millions, and new competitors faced a daunting challenge entering the auto marketplace.17

14 In fact, during the post-Second World War period there had been only two serious attempts to launch a new American car company. Both had occurred in the late 1940s, when the disruptive effects of the war opened new opportunities to makers outside of the Big Three and the handful of independents that remained. One was the Kaiser-Frazer Corporation: Henry J. Kaiser started his company in 1946, but eventually ended car production in the early 1950s. The brand, however, continued to exist under the Willys name, building the famous Jeep until it was bought by American Motors in 1970. The other was the famous Tucker, but Preston Tucker never managed to get to the production stage.18 Bricklin was building the first new American car in nearly three decades, a venture that was not for the faint of heart.

Modernity, industrial modernity and the automobile

15 For all of its challenges and difficulties, and notwithstanding the very few actual examples of an attempt to build a car after 1945 in North America, carmaking in the postwar period retained an allure that gripped the imaginations of entire nations, regions, and state-builders. New Brunswick was not exceptional in this regard; in fact, in its quest to build the Bricklin and an auto industry the province simply reflected long-standing impulses that had been present since the beginning of the 20th century.

16 This was the case, in part, because the automobile was so intimately connected to the very notion of modernity. Though the onset of modernity was a longstanding process – one which spans centuries in some scholars’ views – the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought an acceleration of the seismic transformations to human society most often defined as “modernity.” Historian Keith Walden has catalogued these changes:

The automobile was but one step in this catalogue of modernity, but cars represented particularly profound change. Ian McKay has described the condition of modernity as “the lived experience of unremitting change,” one fuelled largely by industrial capitalism.20 The automobile was the epitome of Joseph Schumpeter’s entrepreneurial “creative destruction,” a process that unleashed and accelerated change.21

17 More so than any other technological, social, or political artefact or construct, the automobile exemplified what it meant to be modern: the automobile itself was a machine, one that changed conceptions of time, place, work, leisure, space, and home, while the industry that had created it – personified by Henry Ford and his moving assembly line – was the exemplar of industrialization, efficiency, scale, and wealth creation. Just as importantly, the car and its industry had destroyed older notions of work and life and automobility had forever changed the established institutions and conceptions of society – from business to the built environment to the activities of the state to notions of individuality.22 “Fordism” became a worldwide phenomenon, one that described a number of causes and consequences of this new form of mass industrialization. At the same time that Fordism described the mass production, standardization, and scale of the moving assembly line and the hugeness of Ford’s vast industrial factories, notably the gigantic Rouge Plant in Detroit, it also described (along with the work of F.W. Taylor or “Taylorism” – the scientific management of labour) the idea of paying workers well enough to actually purchase the products they built (the famous “$5 dollar day”). Fordism was also used to describe the paternalistic, corporate welfare approach to workers. Henry Ford became the wealthiest man on the planet, and his “system” and cars ushered in an economic and social revolution.23

18 This could be seen in the car’s tremendous impact upon North America and Europe by the 1920s and 1930s. Utilizing vertical and horizontal integration on a scale never before seen by humankind to build his machines, by 1927 Ford had sold 15 million Model-Ts, and soon much of the world was on wheels – or wanted to be. Henry’s first international subsidiary, Ford Canada, working from its own “modern” facilities in Windsor, Ontario, built and sold hundreds of thousands of cars to far flung locales as distant as Malaysia, Australia, and South Africa. Giant companies such as General Motors utilized a new class of professional managers to create modern finance, advertising marketing, branding, and sales and distribution networks. The effect of these sprawling, bureaucratic corporations was no less than a re-ordering of the market as well as the birth of entirely new notions of consumption and production.24 Moreover, the social impact of the car was tremendous, reshaping and remaking everyday life by impacting issues as diverse as traffic, work, pollution, sex, city-design, home-building, accidents, travel, and even the rituals of birth, marriage, and death (to name but a few).25

Display large image of Figure 3

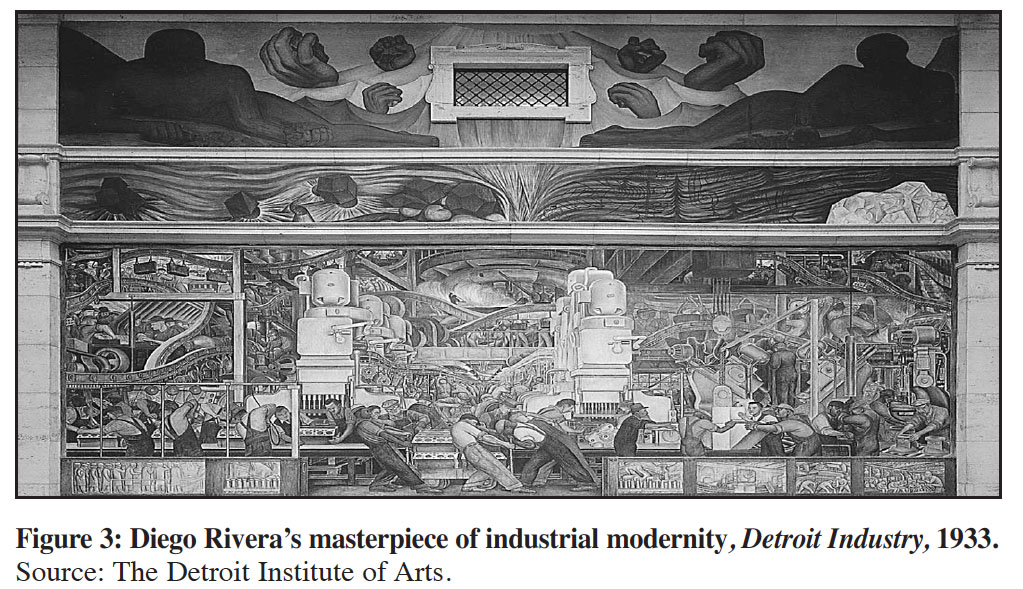

Display large image of Figure 319 The automobile’s imprint as the talisman of modernity became ubiquitous not only in everyday life, but in artistic expression. In his famous film “Modern Times,” Charlie Chaplin mocked and immortalized Ford’s moving assembly line and its reduction of humanity into faceless automation.26 In literature, works such as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World imagined a future where Ford was elevated to the status of a god. F. Scott Fitzgerald made the car a central aspect of The Great Gatsby, as did other American and European authors who placed the automobile at the centre of modernity.27 Diego Rivera’s industrial murals in the Detroit Art Institute became famous both as expressions of industrial modernity and as critiques of the life-changing impact of the car and the processes that had created it.28

20 But automobile modernity was more than a state of being, more than a consequence for individuals and communities. It was also an aspirational goal for nations and governments. In countries around the world, “automania” became the order of the day during the interwar and post-Second World War periods. From Brazil to the Soviet Union to Japan the car was embraced, and car production was lusted after as the mark of a modern industrial economy. Brazilians took a chance on a massive Ford rubber- growing operation in the 1920s and 1930s, while at the same time encouraging local car production as a way to achieve a modern economy. The car and its industry, according to the historian Joel Wolfe, created for Brazilians “hope for an eventual industrial transformation of society . . . . The opening of automobile factories held out the promise of the creation of a disciplined, nonradical working class that mirrored what Brazilians perceived to be the experiences of workers in the United States . . . driven by an established mythology about the ways automobility would transform the nation and its poor.”29 Mexicans, for their part, saw the development of an auto sector as an essential element of the “dream of modernity.”30 In Soviet Russia, of course, car production was seen as the epitome of state planning and a goal of industrial accomplishment, one that was meant to rival the Americans though it often fell somewhat short.31 Japan’s economic “miracle” in the postwar period was only truly recognized when it became a successful manufacturer (and exporter) of automobiles; the ascendency of firms such as Toyota, Honda, and Nissan (Datsun in the early 1970s) granted Japan a rank in the “first world” of “modern” economies.32 Industrial modernity, and the status it conferred, was a worldwide goal of state politicians and planners as well as something supported by the general public.

21 Thus, by the early 1970s the idea of carmaking as a bridge to modernity was not new. Some scholars even referred to the impact of the automobile upon society as multiple stages of “automobile consciousness.”33 Even the growing backlash against automobiles in North America – one personified by Ralph Nader’s safety attacks on the car and General Motors, and the growing unease about cars’ emissions – did not dissuade planners and politicians on both sides of the border from seeking auto investment. For a region such as New Brunswick, with high unemployment, out- migration, and a long history of economic decline based on resource extraction, the idea of an auto industry was enthralling. This was especially true for the idea’s main advocate, Premier Richard Hatfield. Hatfield was simply following in the footsteps of a long line of industrial development promoters in New Brunswick, other Atlantic provinces, and well beyond the confines of North America in pursuing a dream of industrial modernity through automobile production.

New Brunswick and Maritime attempts at industrial modernity and the Bricklin

22 New Brunswick, and the Maritimes more generally, had not been immune to the attractions of industrial modernity before Bricklin. There are many examples of attempts to “modernize” and to become “industrial.” These two concepts are not necessarily connected. Industrial development, as an element of regional economic development, does not necessarily mean modernity. The efforts to revive the coal and steel industry in Nova Scotia, or the expansion of resource extractive industries, were attempts at economic development, but not necessarily industrial modernization through mass manufacturing. But there are several examples of Maritime or Atlantic Canadian efforts to grasp the brass ring of both industrial and economic development and modernity in the Maritimes: wholesaling, power development, and consumer goods.34

23 Indeed, the vast range of efforts by state planners and politicians in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in the “modern” era challenges narratives of a hegemonic anti-modernism in the region. While McKay’s Quest of the Folk makes a spirited argument about the prevailing influence of anti-modernism as a touchstone of Nova Scotia in the interwar (and into the postwar) period, others have challenged this view. As historian Greg Marquis notes in his assessment of McKay’s book,

This can be seen in Nova Scotia’s efforts to build a viable high-technology sector in the province. In the postwar period, Nova Scotia attempted to establish – primarily through government support such as loans and grants – a number of advanced technology sectors and firms in the province. Industries as diverse as the production of radios and heavy water were started with significant government investment, most of which were not successful. New Brunswick, similarly, had its own industrial development initiatives that attempted to develop a higher industrial and technological profile for the province, such as the Westmorland Chemical Plant.36

24 But the auto industry held out a much more tantalizing embrace of technology, capital, and mass production than any of these previous attempts. The car, even in the 1970s, was the epitome of industrial maturity, and the wages, spin-offs and scale of a car plant had a potential that enticed politicians in many jurisdictions to encourage automotive investment. Nova Scotia provided incentives for Volvo to set up a plant in the early 1960s, and the Swedish firm was ramping up production at its Halifax-area plant by the time Bricklin announced his venture. In the same period that Bricklin was settling on New Brunswick for his new venture, Nova Scotia was also home to Canadian Motor Industries or CMI, a rudimentary Japanese assembly plant in Cape Breton that put together Isuzus and Toyotas beginning in 1968. CMI has the distinction of being the first Japanese automotive assembly facility in North America.37

25 Indeed, though the Maritimes seemed to be a destination for new automotive ventures in the postwar period, New Brunswick was not in fact Bricklin’s first choice. The initial contact was with the Quebec government, but Quebec already had its own nascent auto sector with a GM plant and a few parts outfits. The Quebec government’s money was also already going to a number of other state-sponsored industrial development projects. In addition, the Bricklin plan did not look that sound to Quebec officials. But across the border, in New Brunswick, a young premier eager to make his mark was looking for something to spark the provincial economy. Someone in Quebec knew someone in New Brunswick; Bricklin soon had an audience with Hatfield, and quickly convinced the politician of his dream. The dream became Hatfield’s, too, as the premier was captivated by the idea of building flashy cars in his otherwise economically dreary province. By the summer of 1973 the company had an agreement to build cars in New Brunswick, and money from the provincial coffers (and eventually a loan from the federal government) to get started.38 Bricklin had successfully sold himself – and his car – metaphorically, to the government and its premier.

26 When it came to New Brunswick and the Bricklin, it was easy to see how part of the allure of the automobile was the car’s high profile and its potential to draw attention to the province. This was different from resource extraction or even the heavy industries that existed in New Brunswick. Hatfield himself felt as much, stating at one point “What sets the [Bricklin] apart from an investment, in the expansion of a port or a chemical complex, is the publicity that attaches to the manufacture of a new automobile by a new automobile company. It has a high visibility, it attracts wide attention and speculative comment.”39

27 Moreover, building a car was different, required different skill sets, and reflected a commitment to precision, complexity, and innovation that simply did not exist in those other, older sectors of the economy. Building cars could forever bury the idea of New Brunswickers as “hewers of wood and drawers of water.” And the Bricklin itself was even a step above most cars being produced in the 1970s; in its marketing (if not its production reality) it was sold as a high-tech car, one with the latest advances in plastics, engineering, and safety features. After its initial launch, the SV1 was heralded in magazines and trade journals as an innovative advance on automobile technology. Bricklin and his car were honoured by the Ontario Science Centre for exemplifying what one member of its board of trustees said was “the philosophy of the centre.”40 The car was also featured at the Canadian National Exhibition, and even at the Chicago Consumer Electronics Show.

28 Not only was the car innovative, it was spectacularly stylish as well. This made it even more attractive to a politician like Hatfield, who was keen to use Bricklin as a dramatic showcase for the province’s innovative potential. As Hatfield admitted in a 1985 Maclean’s interview, “It’s not that I was ever very much interested in cars. It was the sheer sculptured beauty of the Bricklin, with its doors like a gull’s wings: the idea that something so revolutionary could be made here, in New Brunswick.”41 It was, the Daily Gleaner reported, “the most modern and sophisticated product ever produced in the history of New Brunswick.”42 During the 1974 provincial campaign, referred to by some journalists as the “Bricklin election” despite the many other issues also prominent in the election, Hatfield drove across the province in a leased Bricklin, and his party’s television advertisements featured the car and Bricklin’s assembly line.43 The car, and the idea of building Bricklins in New Brunswick, was more than a simple subtext to the campaign – there was an explicit understanding that a Hatfield mandate meant the province’s continued support for the venture. At campaign events, rallies, and in the news, Hatfield, Bricklin, and the car itself were seemingly always present. When Hatfield won the election on the promise of a Bricklin-fuelled better future, Bricklin was there to celebrate “decked out in Western-style garb, the epitome of the Playboy male.”44 If ever there was an electoral campaign built around the allure of the auto industry in the postwar period in North America, this was it.

29 Even opponents of the car hedged their criticism initially, given the Bricklin’s innovative potential. Though Liberal opposition leader Robert Higgins was “a bit on the sceptical side” regarding the car, he “sincerely” hoped it would work and understood what the car could mean: “I don’t want to be the guy that turns down the Wright brothers.”45 Others were not so enamoured, and one critic later mockingly called the car the “Great Pumpkin out of Cinderella.”46 But on balance, despite the close election results – Hatfield’s Conservatives won 33 seats to Higgins’s Liberals’ 26 – many New Brunswickers were willing to take a chance on Hatfield and his and Bricklin’s dream.

30 At the same time, the process of building the Bricklin was different as well. For all the critiques – and there were many detractors of mass production as exemplified by the automobile’s production – the notion of the modern assembly line was still held aloft as a mark of industrial maturity. An automobile assembly line would put New Brunswick on the map. Economic Development Deputy Minister Harry Nason put it this way:

31 This discourse, to be able to implement Fordism and exhibit an ability to create things on the same scale as a Detroit, Toyota City, or Oshawa, reflected an allure of the assembly line that still drew politicians and planners – and dreamers such as Hatfield and his government.

32 These kind of dreams also required faith, which Hatfield and his colleagues had in no short supply. Along with the dependence on technology and industrial modernity, Bricklin required a good dose of belief since the end product was a risk. Risk reflected the nature of business and entrepreneurialism that was also such a feature of modernity. Hatfield was not unaware of these risks, but proclaimed “I hope and believe the Bricklin car will now become a symbol of what New Brunswick and its people can do, an example of the risks we must run, the patience we must show, the faith we must keep if we are to become a province of economic opportunity and diversity.”48

33 Hatfield’s invocation was echoed by his economic growth minister, Paul Creaghan, who told New Brunswickers in 1974 that “now is the time to have faith” in the Bricklin. This prompted one waggish citizen to reply “Indeed, for the well being of this province, all we can do is have faith, though many experts in the field do not, and are impatiently awaiting the first disaster . . . . Seeing it is our ‘pennies’ involved, Mr Creaghan, we must indeed have faith in it.”49 Similarly, the Moncton Times opined that

34 At the car’s glitzy New York launch in June of 1974, Hatfield sounded more like a revivalist minister than a hard-nosed politician: “Evidence of faith, they say, is evidence of things not seen.” Hatfield had “invested a lot of faith in this car. When I say that I’ve invested a lot of personal faith in this car, that’s what I mean from the point of view of my political career because if it all goes bust, as a lot of people have said it would, everybody would say I was a damn fool.” But he was still hopeful: “I still think you’ve got to try, and you’ve got to believe, and you’ve got to try new things. Some may go under and some of them may succeed. But nothing will happen unless you try something.”51

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 435 Yet for Hatfield the Bricklin was more than just a matter of faith; it also provided an opportunity to get back at the naysayers. Hatfield could point to the car’s futurism, and his province’s ability to build it, as a way of sticking it to Ottawa and the central provinces who, in his eyes, had for so long looked down upon his province.52 Ottawa had proven very difficult in terms of providing support for Bricklin, either through regional development loans or through granting the company status under the 1965 Canada-US Auto Pact (which would have helped the firm considerably by giving it duty-free importation rights from the US). This was a very important consideration for a company that planned to build all of its cars in Canada and sell all of them in the US; a Canadian sales network, ironically, was never established. In its dealings with the federal government over the loan, Ottawa rejected Bricklin’s first application and only gave Bricklin money after he put more of his own financing into the project. When it came to Auto Pact status, one of the terms that Ottawa set out was that Bricklin be a Canadian-owned operation. This was what prompted the provincial government to take a 51% equity share in Bricklin; it would likely not have done so if the federal government had not driven such a hard bargain and made Canadian ownership of a requirement for Auto Pact consideration – status that was, in the end, never granted.53

36 At the Saint John plant’s opening, Hatfield declared that Bricklin’s “success will be our success. We have come this far despite the pessimism of some politicians and the scepticism of self-appointed experts.” After all, in his view, the people of his province were “not just building a car. We’re building a better New Brunswick. If it were produced in Ontario or Quebec there would be more optimism. We are not supposed to have dreams. This ceremony proves they are wrong.”54 Later, as the company teetered on the brink of bankruptcy and critics called for the province to disclose everything about the venture, Hatfield remained defiant, especially towards those outside his province whom he saw as scuttling the effort. Hatfield admitted that “we cannot guarantee the success of any venture”; but, he challenged, “the government cannot leave the economic development of New Brunswick to the mercies of the Canadian banks, the Toronto boardrooms or the federal bureaucracy. Without the involvement of the provincial government, there will be no sustained economic development in New Brunswick except for the tasks these remote institutions think us capable of and suitable for.”55

37 Bricklin was more than just an industrial development scheme, and the continued unwillingness of Ottawa to grant the company status under the Auto Pact or additional economic development loans – Ottawa was unwilling to sink any more than its initial $3 million investment into the company – simply strengthened Hatfield’s commitment. According to one study, Hatfield “saw the response to the Bricklin proposal as another instance in which the economic development of his province was being hindered by the excessive conservatism of a federal government dominated by central Canadian interests.”56

38 As Bricklin wavered on the brink of failure, some New Brunswickers argued that the project had been worth all the trouble and that Hatfield should be given the benefit of the doubt. One anonymous “Bricklin Booster” wrote to the Saint John Times-Globe: “It’s high time someone had a few good words for both the Premier and the Bricklin project . . . which no matter what anyone says, has made Saint John the most publicized city in North America these days.” Bricklin Booster even included a copy of a poem, “The Opposition,” written by Leora Foster of North Lake. The poem included stanzas such as the following:

He fulfilled them every one,

And if they give him half a chance

And if you are so worried

About our Province dear

Just put your shoulder to the wheel

And help him with this deal.

About this nifty car

And how it is a bargain

That will take you far.

And even buy a car or two

And then you’ll see the Bricklin

Roll off the assembly line.57

39 For all this hope, in the end Bricklin was a spectacular failure. In September of 1975, when it became clear that Bricklin was not making enough money and needed more financing, the government put an ultimatum to Malcolm Bricklin. Government-appointed members of the company’s board told Bricklin that he needed to find more outside money in order to get continued government support. When he produced a recapitalization proposal designed to keep the company afloat and asked for another $10 million in financing from the province, it was deemed unacceptable.58 In the middle of a board meeting, Hatfield dramatically arrived to tell the Bricklin directors that no more money would be forthcoming.59 The company was done, and Bricklin’s – and Hatfield’s – dreams dashed. A few days later Hatfield told reporters “I want to say that we still have confidence in the car. Unfortunately, however, there is a limit beyond which it would not be prudent for a government to risk further funds on the basis of such confidence.”60 By that point, New Brunswick had poured over $20 million into the venture.

Conclusion

40 There are many reasons that help to explain the Bricklin’s eventual demise. This article has not focused on those reasons, but instead has tried to connect the Bricklin case to wider conceptualizations of modernity and industrial development, to the local, regional, and national political economies surrounding New Brunswick, and to economic development ideas particularly around the automobile industry.

41 Bricklin reflected the attempts by a sub-national government to bring to its region an industrial driver that would help to alleviate the economic insecurity the region faced (high unemployment, out-migration) and to break the region’s dependence on resource extraction and seasonal and low-wage employment. In doing so, New Brunswick was not unlike many other regions around the world that sought out automotive investment as a panacea for economic uncertainty. Even in North America as late as the 1970s, in a period about to become known for deindustrialization, auto investment was still seen as the pinnacle of economic “maturity” and a sign of a vibrant industrial development. From Mexico to Brazil to Japan, nations and regions only “arrived” and became “major players” after they had achieved an automobile industry.

42 But at the same time, of course, Bricklin was more than that. The nature of the auto industry, itself a harbinger and cause of “modernity” as we understand it, attached to itself something more than a patina of newness, technological advancement, and sheer scale and scope. Auto was different from other types of industries, and its image – one created, condemned, and glorified by nearly a century of representation – drew politicians and planners such as Richard Hatfield like moths to light. Auto production was the height of industrial modernity, and this helps to explain why Hatfield and his province were willing to take such a chance on what seems, in retrospect, such an improbable proposition.

43 The dream of the Bricklin as a spur to launch New Brunswick into a new era of economic prosperity, modernity, and industrial maturity died hard. Even after the traumatic failure of the firm and the political backlash that intermittently and sometimes intensely dogged Hatfield for the remainder of his time in office, Bricklin remained both a reminder of that dream and the high cost of that dream: as late as 1987 the government was still responding to questions from interested parties about restarting production of the car, long after all the machinery had been auctioned off, the company’s records carted off to settle eventually at the Detroit National Automotive History Collection, and the schematics deposited in the provincial archives.61 But this is not surprising, given the allure of an idea of building such a dramatic and stylish product in a place as unlikely as New Brunswick.