Present and Past / Présent et passé

Privileges and Entanglements:

Lessons from History for Nova Scotia’s Politics of Energy

1 IN JULY 2009, THE GOVERNMENT OF NOVA SCOTIA made a striking announcement: by 2015, 25 per cent of the province’s electricity would be supplied by renewable sources (at that point only 11 per cent of its electricity came from renewables and the rest from generating plants fired by imported coal). Nova Scotia then became the first province in Canada to place hard caps on greenhouse gas emissions in the electricity sector.1 Six months later the province sent a delegation to the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 15) in Copenhagen to promote its sustainable energy projects, in particular a new tidal turbine in the Bay of Fundy (site of the world’s highest tides). That same month, a report commissioned by the Nova Scotia Department of Energy as to how to reach the 2015 target stated confidently that by 2020 “energy poverty would be eliminated. There is no financial, economic, environmental, social or technological reason why this should not happen.”2 Evidently encouraged, in the spring of 2010 the province released its Renewable Electricity Plan, reaffirming the 2015 target and adding a further goal of 40 per cent from renewable sources by 2020.3 By 2012, the 2020 target was cemented as law, in large part on the basis of an unprecedented agreement with the province of Newfoundland and Labrador to develop jointly a hydro-electricity project on the Lower Churchill River.

2 That is an awful lot for a very small jurisdiction to promise in three years, let alone one that has struggled with economic torpor for much of the 20th century. But in all the discussion about energy realities and energy futures there has been no reference to Nova Scotia’s energy history, or the role this history has played in creating the province’s political culture and identity. While energy has always been one of the most contentious aspects of federal/provincial relations in Canada, there has been little public discussion about how energy resources profoundly shaped Nova Scotia’s place within first the British Empire and then the Canadian federation in ways that continue to resonate today. As is often the case with environmental issues and environmental decision-making, Nova Scotia’s energy profile is presented through a compression of time that features only the present and future, emphasizing a sense of crisis, the importance of innovation, and predictions for future outcomes.

3 But the environmental historian sees the story differently.4 During the mid-19th century wind and tides gave rise to the twin industries of shipping and shipbuilding, which in turn nurtured a confidence and commitment to a global trading system among the colony’s merchant and political elites. Much of their opposition to Confederation in the 1860s stemmed from a sense of environmental investment: resistance to a framework oriented toward a continental interior and away from a maritime economy and a coastal way of life. Indeed, Canada’s industrial heartland soon demonstrated that it considered Nova Scotia most valuable to the federation for its coal resources – literally fuel for nation-building projects concentrated west of the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. This external demand for coal and steel bound the province into a web of corporate and political dependencies that lasted for a century – a web that entangled industrial development with great costs in environmental sustainability, public health, and energy security. And yet, for decades, Nova Scotia, like many other Canadian provinces, has promoted particularly fossil fuel production as a means of (re)gaining both political and economic leverage within Canada and, specifically, against the federal government. The current campaign featuring (without irony) both renewable and offshore energy is a new chapter in a debate that began over two centuries ago: what is Nova Scotia’s place in Canada and the world – and how might it use energy resources to answer that question?

4 This essay, then, attempts something rather unusual. It asks us to consider eastern Canada in energy history – a subject that has more typically drawn the attention of political scientists focused on the rise of the “new west” – and one that in Atlantic Canada has been cast more as a study of labour than of environment or politics. The essay deliberately takes a longer view: connecting patterns across a colonial and postcolonial past, pointing out broader themes relevant to the current discussion, and thus demonstrating how an historical perspective can be usefully incorporated into public debate and policy formulation about the environment. It tries to recognize the importance of cultural and political memory as well as economic and technological change. It points to the depth and variety of Nova Scotia’s energy sources, throughout its history, to suggest a small jurisdiction’s capacity as an historical energy producer – including but, importantly, not limited to the Cape Breton coalfields of the 20th century and the Scotian Slope parcels of the 21st. At the same time it emphasizes how energy production profoundly shapes the political experience of a small jurisdiction, especially one in a larger political framework – whether a colony of empire or a province of Canada.

Canvas on every sea: early colonial energies

5 Nova Scotia’s energy resources first drew the attention of the French as they colonized the region they called Acadie during the early 17th century, when they discovered coal outcroppings along the Atlantic shores of Cape Breton Island. These coal deposits would prove to be the most important (bituminous) coalfields in eastern Canada.5 The first commercial coal mine in North America was operating at Port Morien on Cape Breton (then known to the French as Île Royale) by the early 18th century. While there were shipments to other New World colonies, the French were primarily interested in coal for their major construction in the colony, the Fortress Louisbourg, which stood guard over the Atlantic fishing grounds and the critical route to the continental interior at the mouth of the St. Lawrence. After France surrendered Île Royale along with almost all its holdings in North America to Britain in 1763, the region’s coal drew even greater attention in the new imperial centre and its rapidly industrializing cities. As early as 1800, coal royalties formed the most important source of revenue for the then-separate colony of Cape Breton, establishing a pattern – and problem – that would endure. An economy of resource exports would be intertwined with state-building – “at the service of, and indeed an activity of, statecraft.” 6 At the same time, though, the burgeoning coal industry cultivated an early public association that resource extraction was detrimental to colonial rights and local interests. By the 1830s, reformers in the colonial legislature were campaigning for higher royalties from the London monopoly controlling mining operations on Cape Breton; these reformers would help make Nova Scotia the first colony in the British Empire to achieve responsible government a decade later. 7

6 If mining rights were carefully leased by Whitehall, no one could secure exclusive rights to wind and tides. And if Nova Scotia’s coal resources were useful to the empire, its ports were much more so. From 1749 until 1905 Halifax was a principal base for the Atlantic squadrons of the imperial navy – indeed, the need for a naval base in Acadia was the entire reason for founding the city – while along its 13,000 kilometres of coastline smaller communities emerged, fuelled by three intertwined industries all based on wind and biomass: shipbuilding, the shipping trade, and the fishery. Communities on the Atlantic, Fundy, and Northumberland shores – towns such as Lunenburg, Shelburne, and Maitland – became known internationally for their schooners and dories, especially as demand grew from the emerging offshore fishery sailing to the Grand Banks as well as from the growing transoceanic trade within the British Empire. Shipping tonnage owned in the colony, for example, increased from 80,000 tons in 1830 to 400,000 tons in the late 1860s. 8 This fostered a sense of confidence and international presence among Anglo-Saxon merchants, including shipbuilder William D. Lawrence of Maitland:

7 Wooden sailing vessels had been largely relegated to local use by the time of the First World War. But a romanticized memory of the age of sail has remained the defining public image of Nova Scotia, its golden age and preferred historical point of reference. This is thanks in large part to one, already somewhat anachronistic, fishing schooner: the Bluenose. Built in Lunenburg in 1921, it famously won a series of international races and became such a symbol of the province that it appears on the Canadian ten-cent coin and inspired a reconstruction that still sails annually. Even in 2011, Irving Shipyards capitalized on the sentimental/historical association with shipbuilding to win a $25-billion share of a national shipbuilding contract. The Nova Scotian “Ships Start Here” campaign characterized Nova Scotians as natural shipbuilders by assembling a genealogy that ran from Samuel Cunard to the Bluenose to the late-20th-century capabilities of the Irving Shipyard to the anticipated patrol fleet. The words “Ships Start Here” were emblazoned atop an archival photograph of workers building a schooner in 1920s Lunenburg. 10

The cost of Confederation: a new energy economy

8 Problems were inevitable when a colony that had prized above all its place on the Atlantic seaboard entered into a new continental framework. The seven colonies remaining in British North America in 1864 were divided by uneven populations, asymmetrical economic growth, and disparate histories; but all (with the exception of British Columbia) were reasonably clustered in some geographical proximity and still heavily oriented to maritime commerce and communications (although generally we do not conceptualize Confederation-era Canada around the Gulf of the St. Lawrence, and we might). History, though, has generally emphasized the colonies’ common insecurities introduced by their Atlantic affiliates, whether the loss of imperial and continental trade agreements, an imperial government increasingly disinclined to support them economically or militarily, or an American neighbour eyeing British territory for possible annexation even as it was divided in civil war (quite an accomplishment). What began as a discussion of Maritime Union of the three smallest colonies was subsumed by the more ambitious proposal from politicians from the Province of Canada – comprising the old Lower and Upper Canada – for a federation of all British North America into a new nation-state, a veritable dominion.

9 One of the central debates of Atlantic Canada’s historiography has been the extent to which Nova Scotians accepted or distrusted the terms of Confederation, but it is worth looking again at the strongly environmental dimension of much of the criticism. Fears of being overshadowed by the larger and more populous Canadas extended beyond scale of territory or representation in Parliament; at the core of anti-Confederate sentiment lay an anxiety that the Maritime colonies’ seaboard history, identity, and livelihood would be disregarded. Confederation would subject “this people, their revenues, resources, and independence, to the virtual denomination [sic] of another colony” read one petition from southern Queen’s County; Nova Scotians, said another from King’s County, “do not desire to be transferred to the dominion of a sister Province with which they have no connexion: almost no trade, and which being frozen up for five months of the year, and possessing no navy or troops to spare, is incapable of forming a new nationality or protecting the seaboard of Nova Scotia.”11 Allying with non -maritime colonies interested in an undeveloped interior seemed to make little sense, whether in economic terms or suggesting any kind of common neo-national affiliation. With the ties to (and profits from) foreign ports visible daily, it seemed counterintuitive to “turn their backs upon England and fix their thoughts upon Ottawa.” 12

10 It also seemed a voluntary surrender of status – was it not better to be a smaller fish in a bigger (imperial) pond, than to cast their lot with other colonials? From a later perspective, it is clear that either Nova Scotians were naive in their confidence in the privileges bestowed by their British affiliation, or anti-Confederates overstated the colony’s standing in the empire (or both). But it was a useful political strategy. Just as the pro-Confederates used a grandiose rhetoric of continentalist, sea-to-sea nation-building to elevate a largely pragmatic arrangement concerned with revenue jurisdictions and railways, anti-Confederates traded on the prestige of the British Empire and its overtly oceanic character (sea and sea) to heighten their economic vision for Nova Scotia. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that through much of the 19th century Nova Scotian politicians were equating dependency on coal royalties with colonial exploitation and maritime energies of wind and tide with cosmopolitanism and colonial empowerment.

11 The anti-Confederates’ stronger argument, in hindsight, was that Confederation threatened to suffocate Nova Scotians’ sense of self-determination and difference tied to both an economy and an identity based on maritime energies. The priorities of a small coastal colony invested in global trade would undoubtedly be displaced by the industrial and landward interests of the larger, wealthier Canadas once within a national (rather than imperial) economic framework. Not surprisingly, the debate over Confederation divided Nova Scotians along geo-economic lines: merchants and coastal communities dependent on international trade generally opposed the deal while places like Cape Breton, which could supply coal to the factories of the St. Lawrence valley but which would need a national railway to do so, were in favour.13 But anti-Confederates could also appeal to the emotional or psychological cost of a divorce from the sea. That master of the 19th-century art of public rhetoric, Joseph Howe, knew to appeal to his public’s cultural investment in a particular environmental orientation. “Take a Nova Scotian to Ottawa, away from tidewater, freeze him up for five months, where he cannot view the Atlantic, smell salt water, or see the sail of a ship,” Howe warned direly, “and the man will pine and die.” 14

12 Like most pieces of legislation during the 19th century, in setting out the terms of Confederation the British North America Act of 1867 divided nature by resource because this explained and framed the natural world in terms of utility and thus of revenue. Critically, the provinces were given jurisdiction over public lands, timber sales, and mineral rights. In other words, energy resources – from fossil fuels to riverine hydroelectricity – were embedded in provincial statecraft from Canada’s conception and would form the nucleus of nearly every major campaign for provincial rights. Within two decades of Confederation, “Empire Ontario” had used legal challenges over resource rights and development projects (notably in hydro-electricity) to enhance its standing in the federation. In Nova Scotia, coal royalties represented the greatest single source of revenue for the provincial government in the early 20th century. 15

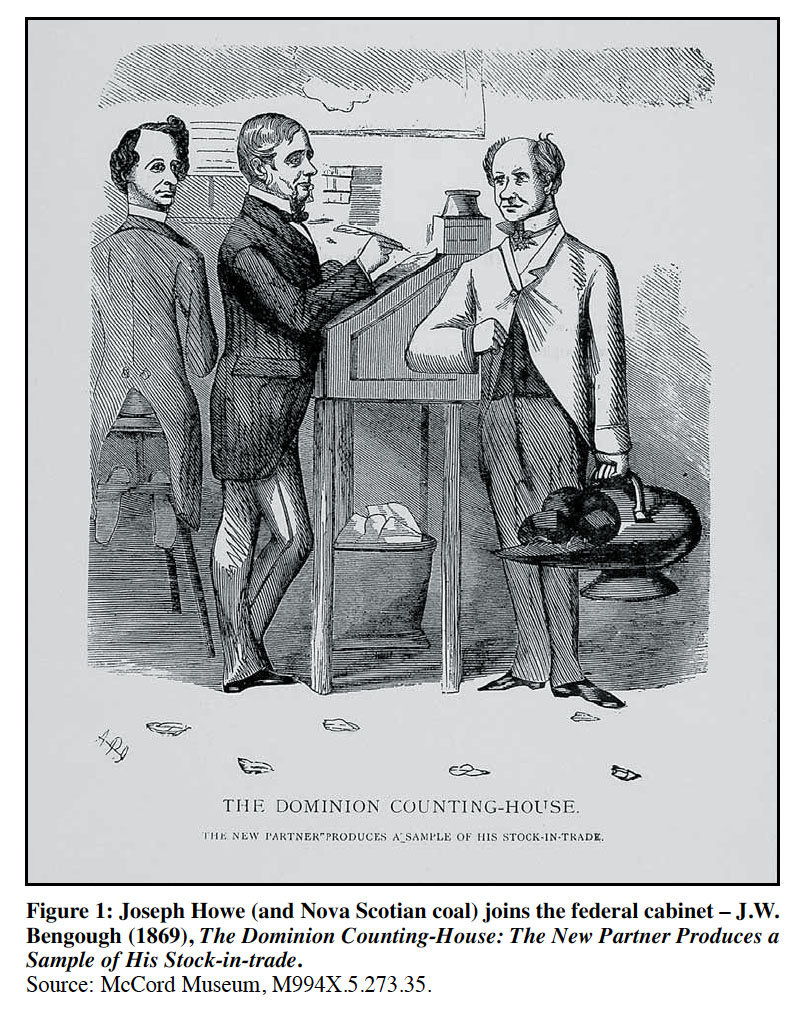

13 But in the Maritimes the potential for autonomous development was countermanded by a determined, centralist federal government still in possession of the territory and resources of the vast northwest, and itself very much in the possession of Ontario and Quebec voters. For decades Nova Scotians would complain of Ottawa’s preoccupation with developing the west – not the east – and they would be divided over the benefits of a National Policy designed to favour domestic manufacturers. Certainly there was significant economic growth from the late 1870s onward, thanks to this new federal framework and new transprovincial markets.16 The Intercolonial Railway linking Nova Scotia to Quebec was completed by 1879, and communities in the coalfields, such as New Glasgow, became major centres manufacturing consumer and industrial products from glassware to railway stock. But as continental economic integration steered Nova Scotia from international markets to internal ones, and from trade and shipbuilding to manufacturing, it also concentrated on one kind of energy the province had to offer, the one most suited for steam-powered manufacturing: coal. An 1869 cartoon by J.W. Bengough (Figure 1) captures this perfectly: “The Dominion Counting-House. The New Partner Produces a Sample of His Stock-in-trade” shows Joseph Howe accepting his seat in cabinet with a laden coal scuttle, while Minister of Finance John Rose and Prime Minister John A. Macdonald look on approvingly. Such a warm reception to the province’s coal dowry contrasts with the federal cabinet’s tepid response to simultaneous campaigning to make Halifax the “wharf of the Dominion,” a role based on the city’s environmental advantages as a year-round port and one still alive today as “the so-called ‘gateway concept’ . . . a 150-year dream, which has never been fully realized.” 17

14 The triumph of fossil fuels over wind and sea during this period is still visible in the physical and demographic geography of Nova Scotia. Consider again William Lawrence and his adopted town of Maitland. In the latter 19th century Maitland was, like other towns on the Bay of Fundy, busy with shipyards and confident in its role as a gateway to international prosperity. Lawrence was a shipbuilder with diverse mercantile interests and, not surprisingly, also a representative in the House of Assembly from 1863 to 1871, where he campaigned against Confederation. In 1874 he launched the William D. Lawrence, at 2,459 tons the largest full-rigged vessel ever built in Canada. The message was unsubtle, to put it mildly: the “Great Ship” was designed to symbolize the strength and capacity of Nova Scotia as a maritime power, profiting “by its own enterprise and by its own vigorous exertions.”18 Today, however, Maitland is a designated heritage conservation district with a population of about 1,700, a line of lovely if somewhat decrepit Victorian houses far removed from any highway traffic. The provincial museum system operates the Lawrence House Museum, complete with a model of the Great Ship, and the town hosts the annual “Launch Days,” a summer weekend festival commemorating, as expected, the ship and the age of sail.19 Maitland, in other words, is in many ways a museum to the 1870s. In contrast, Cape Breton Regional Municipality, which emerged in the same period as the pre-eminent coal district in eastern Canada even as Maitland declined, became and remains the second biggest urban entity in the province; Truro, located on the Intercolonial Railway near to the Cumberland coalfields and still billed as “the hub of Nova Scotia,” is the third.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 115 Nova Scotian coal, however, never really became a major international export due to its difficult location largely under the ocean floor, the superiority of coal in Pennsylvania and the Appalachia fields nearer to major American cities, and, by the start of the 20th century, the development of western Canadian reserves. Integration into a national economy did bring more investment capital into the province, and expanded the scale and output of Nova Scotia heavy industry. But as regional activists observed at the time and historians would argue decades later, it also triggered an erosion of entrepreneurial autonomy as Montreal-based corporations absorbed the corporate interests of most major Nova Scotia manufacturers. Empowered by American and British capital, outside investors also propelled the amalgamation of collieries in Cape Breton. It became the largest coal and steel operation in the country, accounting for half of Canada’s coal and steel production. But the area’s role in the national project was increasingly, if predictably, as a resource hinterland. As one observer wrote for the Canada Mines Branch in 1917:

Such an analysis – recognizing the advantages of Nova Scotia’s coastal location on the one hand, and the balance of power in Confederation draining its resources and rate of growth on the other – will sound eerily familiar to anyone reading the business and op/ed sections of any Nova Scotia newspaper through much of the late 20th century and even in the early 21st. In particular, the analogy with a mining camp was apt for a number of reasons by this point: the famously poor quality of life in company towns, the rapid influx of migrant labour, and the struggle to meet new industrial demands for power and water supply.21 The trend of three decades culminated in the postwar era with creation of the British Empire Steel Corporation (BESCO) in 1920: one of Canada’s largest corporations and a true empire of coal mines, steel mills, foundries, railways, and ports across Nova Scotia. BESCO also engendered some of the worst labour conflict in North American history, where the politics of energy were as much local as national: municipal efforts to expand electricity production were often blocked by existing monopolies, and in 1924-1925 BESCO cut off coal, electricity, and water to miners’ houses. 22

16 The uneven and unequal relationship between centre and east was both mirrored in and accelerated by the Maritimes’ relatively little and ever-decreasing political influence in the federation. With the population booming in the new western provinces, Nova Scotia’s representation in the House of Commons shrank from 19 seats of 181 in 1867 to 14 of 245 in 1924.23 Marginalized politically, and unable to effect significant changes to the intranational framework beyond temporary economic concessions, Nova Scotia and the other Maritime provinces simmered in frustration – the roots of what Ontario-born and Alberta-based Prime Minister Stephen Harper would famously deride 80 years later as a “culture of defeat.” 24 Harper’s phrase was both overstated and unfair, but even by the 1920s very few believed Nova Scotia’s commerce would again extend “from the cold north to the sunny south.”

Provincial energies, provincial power

17 In the confident economic climate following the Second World War, the political experiment of Canada seemed to have succeeded. But energy remained one of the key sources of federal/provincial tension, especially when Ottawa attempted to impose national energy plans – whether for pipelines, production, or pricing. For Nova Scotia, however, the relationship was less contentious than co-dependent, as both levels of government tried to shore up a failing mining industry. The same is true today, of course, with the federal and provincial governments across the country each offering subsidies for oil and gas development in the form of tax breaks and royalty reductions. 25 By the early 1960s, BESCO’s successor, the Dominion Steel and Coal Company (DOSCO) was shutting down poorly performing mines in the Pictou and Sydney coal fields, and in 1965 announced its remaining mines had only 15 years of production left. A royal commission concluded it was “ethically wrong and economically unsound” to sustain the industry, plans were made for a mining museum to commemorate “a way of life that is fast disappearing,” and Ottawa and the province nationalized DOSCO’s coal and steel operations with plans to phase both out entirely.26 The opening of new operations in northern Alberta drew a new flow of Maritime outmigrants, newly unemployed miners self-described as “economic refugees.” 27

18 Ironically, this inspired a rich new body of cultural production in and about Nova Scotia, its industrial landscapes, and its tendentious relationship with the nation’s east-west axis. In the iconic film Goin’ Down the Road (1970), the camera moves

In the more comical New Waterford Girl (1999), the former mining town of New Waterford is on the fringes of the known world – literally where the road ends. The teenage heroine sardonically rhymes off the “grand tour” of the town’s dead-end geography to an unwisely enthusiastic newcomer: “My house, your house. There’s the shore. The mine. The main drag. Hospital, tavern, church, tavern, church, church, rink, school, train station, road to Sydney.”29 The sense of economic fragility also enlivened a new generation of academic critique directed toward the “hidden injuries of dependence” and the power imbalance in Confederation – just as anti-Confederates and secessionists had argued decades before.30 In 1966 Premier Robert Stanfield told the Empire Club of Canada, one of the most symbolic seats of Ontario’s power, “If Nova Scotians had allowed themselves to be governed by economic considerations . . . Canada would not have been created in 1867.” 31

19 The expanded activist state of postwar Canada responded to the decline of the coal industry and the economic stagnation of Atlantic Canada in two main ways. The federal government created a bureaucratic soup of agencies and funding programs targeting underdevelopment, in particular in rural areas.32 Both Ottawa and the provinces tried to promote economic diversification, especially through tourism (a not entirely effective approach given the notoriously low-wage, seasonal jobs tourism generates). This reached its greatest expression in the most coal-dependent and thus most depressed region with the reconstruction of the 18th-century fortress at Louisbourg, designed as much to provide jobs in the coal- and employment-exhausted communities of eastern Cape Breton as to commemorate the heights of la Nouvelle France. 33

20 But, as is often the case in history, these initiatives for change did not fundamentally dislodge a foundation of continuity. Energy megaprojects remained singularly the most lucrative means to prosperity and political advantage, a crucible for provincial nationalism that has produced some of the most famous moments of provincial ambition and provincial/federal conflict in recent Canadian history. Thanks to the current political climate and the resulting preoccupation of political scientists, we typically think of energy politics as a hallmark of western – specifically Albertan – interests. Alberta’s defiance of the federal National Energy Policy in 1980, encapsulated by the bumper sticker that read “Let the eastern bastards freeze in the dark,” epitomized the association between fuel revenue and political autonomy. But the eastern provinces have been as committed to local energy production as a means to greater fiscal and constitutional sovereignty. In 1963, as part of its Révolution Tranquille, Quebec nationalized the hydro-electricity sector in order to claim “that white oil that is the wealth of Quebec” and as one of the first steps in becoming “maîtres chez nous.” Pointing to the offshore drilling at Hibernia to the east and the new expanded hydro development on the Lower Churchill to the west, the premier of Newfoundland and Labrador declared in 2007 that the province would realize “economic equality within the Federation . . . and becoming masters in our own house.” New Brunswick began construction on the only nuclear plant in Atlantic Canada at Point Lepreau in 1975, as the oil crisis made energy security a concern for most administrations in the industrialized world. 34 Even Canada’s smallest province attempted to use energy technologies to leverage self-sufficiency in the 1970s, albeit in a very different way. Prince Edward Island – smaller, poorer, and suffering more from outmigration than even Nova Scotia – briefly led the world in alternate energy design thanks to the government-funded Institute for Man and Resources and its experimental housing counterpart the Ark. 35

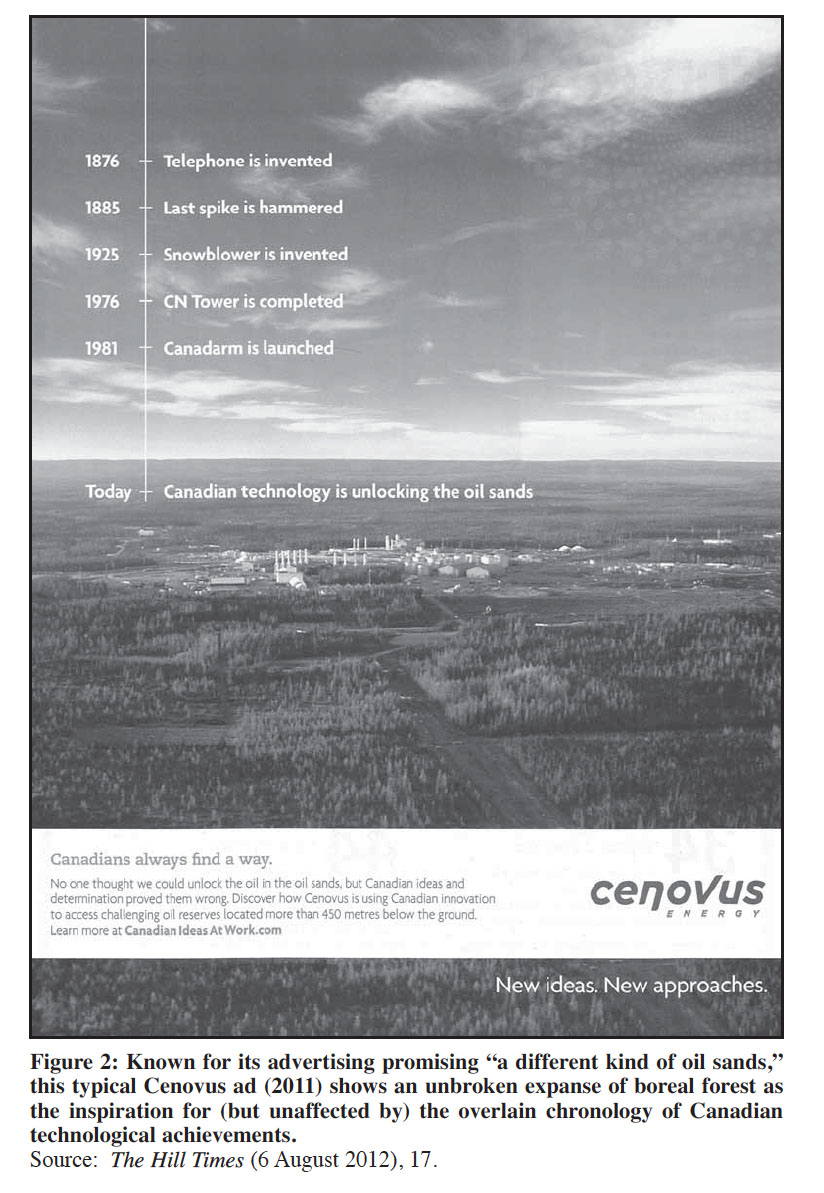

21 The consistent interest in hydro-electricity notwithstanding, fossil fuels have always been viewed by the provinces as their constitutional ace-in-the-hole. Sustained by both the entrenched nature of the industrial grid and ever-new hopes for political gain, non-renewable energy has often been treated like the only viable game in town. The two alternatives occasionally proposed since the 1960s to the demonstrated instability of the fuel market – economic diversification and renewable energies – have been repeatedly shunted aside by a series of ever-larger projects involving coal, then oil, now gas. The OPEC-driven oil crisis of the mid-1970s prompted Nova Scotia to reignite its coal-fired electricity plants in hopes of reducing its reliance on foreign energy sources; but with Cape Breton largely exhausted these plants were using imported coal and petrocoke 20 years later. The province’s commitment to fossil fuels remained intact even through two of Canada’s biggest environmental disasters: the wreck of the Arrow in 1970, which contaminated 300 kilometres of Atlantic shoreline in the largest oil spill in Canadian history, and the realization that the “tar ponds” of decades-old steel and mining waste at Sydney were the most hazardous waste site in the country (making them a cause célèbre of North American environmental groups). Today hopes linger that the Imperial Oil refinery on the Halifax harbour – dating to 1918 – will experience a “renaissance” with the as-yet-unproposed pipelines from western sources, although the refinery has been for sale for over a year and such hopes are likely kept alive by the current lobbying for a pipeline from Alberta to the port of Saint John.36 Such optimism is mirrored and reproduced in the successful media campaigns of major energy corporations across Canada, which cast energy technologies as a heroic story of innovation and “made in Canada” ingenuity while quietly reinforcing the myth of inexhaustibility (Figure 2).

Display large image of Figure 2

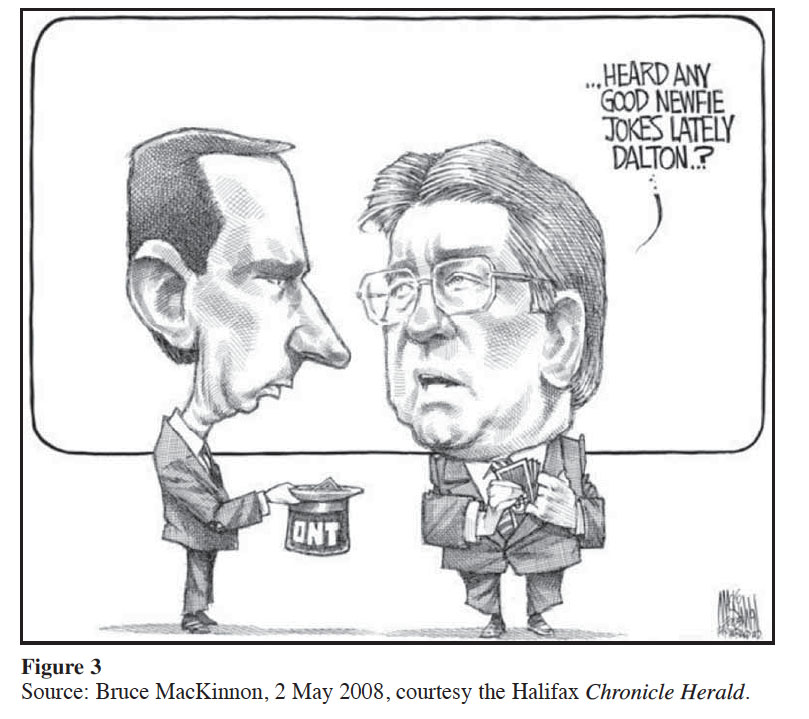

Display large image of Figure 222 Since the 1960s and the decline of the region’s coal industry, these historical patterns and investments – political and economic – have been preserved in Nova Scotia’s energy sector by the exploration and development of offshore oil and gas. While the province counts natural gas towards its clean energy targets, it still is, of course, an extractive non-renewable energy source. Exploration of the Scotian Slope, about 250 kilometres away, established massive natural gas operations near Sable Island (1999) and Deep Panuke (2007), thanks in part to active research funded by the province. “We will continue to invest in important geoscience information and knock on the doors of the world’s top oil and gas companies,” said Premier Darrell Dexter in 2012, sounding not unlike his predecessors a century earlier.37 In a contradictory but utterly Canadian moment, Sable Island was also proudly named a national park reserve in 2010, and attained the full status of a national park in 2013. In January 2012, the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board awarded $970 million in offshore exploration rights to Shell Canada; four months later, it issued the largest call for offshore bids in the province’s history. Accordingly, much of the federal/provincial dialogue since the 1980s has been taken up with negotiation over federal transfer payments in light of – or more precisely, in anticipation of – new fuel royalties. Transfer payments are literal compensation for Confederation, attempts to create “economic equality within the Federation” between so-called “have” and “have-not” provinces. While Newfoundland is presented as the Atlantic “have” province (Figure 3), Nova Scotia has not yet made the transition from the one to the other on the basis of its oil and gas sector. But the historian sees in these negotiations an echo of the calls for “better terms” after 1867 and attempts to negotiate greater federal subsidies for decades thereafter. 38

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 323 Even the proposals for renewable energy require the construction of massive new infrastructure, and have been couched – by governments, and repeated in the media – in language primarily if not almost exclusively about economic growth, investment and cost, and provincial (forgive the pun) empowerment.39 Tentative ventures in tidal energy on the Bay of Fundy have been characterized in terms of advancements in hydraulic machinery and as a means of technological incubation in the province.40 The NDP government has argued for a massive hydro-electricity project on the Lower Churchill River in Labrador at Muskrat Falls, to be jointly developed with the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, as a lower-cost alternative for energy supply. A key consultant report submitted early in 2013 ranked domestic generation (particularly wind power) higher than hydroelectricity supplied by either Muskrat Falls or Hydro-Québec in delivering on the province’s lesser goals: diversity of supply and, eventually, cleaner energy. But the report recommended the Maritime Link Project above the other two options on essentially economic grounds: reliability of supply, which in turn promises more competitive pricing. More telling was the report’s ranking of the Maritime Link higher on achieving emission and renewable targets.41 In a country well-versed in the high-modern logic of hydroelectric dams, these conclusions themselves were predictable.

24 But woven throughout are reminders that key to all of this is Nova Scotia’s geographical location in Atlantic Canada, and that such technological innovation may carry with it political reincarnation. The proposed “Maritime Link” transmission cable, designed to carry electricity from Labrador to Cape Breton – and possibly at some point on to New England by way of New Brunswick – suggests the coastal affinity of a Maritime Union and the memory that for Nova Scotia schooners “there isn’t that much ocean between Boston and St. John’s.”42 And it is as easy to call to mind a parallel thread of history as well: an older suspicion of central Canada. One of the criticisms levelled against the Muskrat Falls deal by the Liberal opposition has been that the Nova Scotia government discounted a possible arrangement with Hydro-Québec too quickly; the NDP responded with an ad clearly designed to hit a regionalist nerve:

Even the government’s characterization of the Muskrat project as “fair energy” suggests a contrasting history of unfair energy.44 It is a skillful political maneuver, calculated to evoke anxieties about an erosion of authority to a more powerful jurisdiction, and to echo Joseph Howe’s warnings of 150 years ago:

Energy futures in energy past

25 Nova Scotia has been trapped by past and present: in the grooves of past practice and the realities of a global economy still driven by fossil fuels.46 It does not yet have the economic or political motivation to support dramatic environmental innovation. A privatized energy utility will prefer cheaper imported coal and existing infrastructure to maximize profit; infrastructures and ideologies of energy extraction and distribution take on a technological momentum of their own.47 Like most of Canada, the province’s economy is still oriented toward natural resources. It lacks the depth of revenues and expertise of Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, and British Columbia – provinces to which, ironically, Nova Scotian expertise migrates, and doubly ironically, often to employment in the extractive industries.48 And, despite efficiency programs, the bulk of the discussion has centred on new production rather than reduced consumption, which is arguably more important for long-term energy supplies. Lastly, there has not been a real groundswell of public support for a new energy paradigm; the majority supports the clean energy targets in theory, but local communities do not always want wind farms in practice. This is a relatively older, conservative audience with a “history of mistrust and politicization” of energy supply and innovation. 49

26 But history informs – it need not prescribe. As David Wheeler, co-author of the 2009 renewable energy strategy, reflected in 2013, there has been a notable change in the political climate: “Between 2007 and 2010, this province established something of a political consensus on energy policy,” including a commitment to increase energy efficiency, phase out coal-fired power generation, and expand wind power.50 Even alongside the dominant emphasis on oil and gas exploration, these new priorities are not immaterial (however much that sounds like damning with faint praise). In light of Canada’s historical incapacity of developing a national energy strategy, responsibility for change will fall to the provinces.51 And it can be argued that Nova Scotia’s history might make it more sympathetic to renewable energies than other jurisdictions. In focusing on the economics of environmental innovation, we likely underestimate the role of “sentiment and symbolism” in maintaining or, more to the point, changing attitudes about environmental practices.52 There is a remarkable palimpsest of energy landscapes here, and renewable energy projects can be cast as making use of familiar regional features. This is a constructive use to which the golden age might be put: invoking the imagery of propulsion by wind and tide. We now plant tidal turbines where we used to plant ship cradles, both activities making use of the unique heights and speeds of the Bay of Fundy. Most of the existing wind projects follow the old path of the Intercolonial Railway into the Pictou highlands and the mining towns of Cape Breton, finding new use for a topography exhausted in and by heavy manufacturing and coal production (Figure 4). While biomass is a small part of the renewable strategy, the construction of a new biomass plant at a struggling mill in Port Hawkesbury is far from coincidental; it is meant to find new use for the longstanding and locally critical forestry industry of Cape Breton. 53

27 The notion of advancing provincial “revenues and independence” through energy resources is equally familiar. Energy security here means independence or protection from external control, whether unstable global fuel markets, a minority status in national politics, or Canada’s deteriorating international reputation. Nova Scotians “will want to be self-reliant to the greatest extent possible,” concluded the 2009 strategy, “and not have their energy prices dictated by actors outside of Nova Scotia who do not answer to Nova Scotians or their responsible authorities.”54 What the authors of that report did not recognize (or mention), of course, was that “how Nova Scotians feel” about volatile fuel prices in 2012 could also have been said about concentrated corporate ownership in 1925, national tariffs in 1867, or inequitable royalty rates in 1830. The renewable energy initiative itself arose for the same reasons that have always motivated individual provinces to develop their own energy resources: to assert autonomy within the federation and to further their particular economic interests. What is new is that while fossil fuel-rich provinces such as Alberta continue to defy federal control of energy resources in the spirit of provincial rights, they also tout their alternative energy projects as symbols of their ability to be maîtres chez eux. This has become more important, and more obvious, in the last decade, with the sharp decline in Canada’s international reputation for environmental protection. At COP 15 in 2009, for example, the provincial delegation presented itself clearly as Nova Scotia first and Canadian second in its entrepreneurial promotion of local projects and its conscious effort to disassociate from the federal government.55 Like the merchants of the 19th century, the green energy campaign tries to present Nova Scotia as a small but vital and autonomous member of the global community.

28 The renewable energy program’s emphasis on community-scale projects also recalls (however unwittingly!) the colonial-era history of smaller coastal communities self-reliant in energy production but linked in commerce and character. Urging community-scale investments (as the current plan does) counters the 20th-century trend of centralization and externality, whether coal conglomerates or a single provincial utility, in favour of something resembling more the seaboard communities of colonial Nova Scotia with their own “revenues, resources, and independence.” While Halifax Regional Municipality, a World Energy City, has attracted the most attention for its geothermal buildings and “solar city” program, even more appropriate – and suggestive for other Nova Scotian communities – is the geothermal system in Glace Bay, which uses water underground in abandoned mines for heating.56 A return to small-scale municipal energy strategies, using a diverse array of sources, may be an answer for coastal communities in Nova Scotia.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 429 On that note, it is worth noting the similarities between Nova Scotia (and, for that matter, neighbouring Prince Edward Island) and another small, coastal territory with a leading profile in renewable energy. While Nova Scotia returned to its coal-fired generators amid the oil crisis of the 1970s, Denmark took a longer forward-looking view by committing to research and development of a renewable energy sector, specifically wind turbine design, and safeguarding a domestic market for renewable energy, notably through feed-in tariffs. This hybrid model of energy delivery has managed to combine locally-generated power with the conventional large-scale grid, a hybridization that required state commitment (including national R&D), sympathetic utilities, the adaptation of small-scale equipment manufacturers to wind technologies, innovations in near- and off-shore wind power, and, notably, decentralized local ownership of turbines. This combination of large and small is what has enabled the island of Samsø to render itself carbon-negative, and a net exporter of electricity to the mainland.57 While the 2009 Nova Scotian strategy frequently referenced Ontario’s renewable energy plan as a comparator and model, Nova Scotia arguably shares more with Denmark. Obviously a nation-state is more fully autonomous than a province, but the key lesson is that long-term state commitment is essential, maritime environments are wonderful sources of sustainable energy, and small size need not be a deterrent.

Conclusion: “The wind itself is free”

30 Much Canadian history has focused on the encouraging, stabilizing, and progressive narrative of nation-building, which prioritizes the accomplishments (or shortcomings) of the nation-state after Confederation. The relationship between or continuities along colonial and postcolonial status has not been as central.58 The paradigm of metropolis and hinterland, preferred by historians of post-Confederation Canada, can apply to a colony and imperial centre as much as to a province or to the national capital. But apart from the resentment of a western hinterland sometimes wanting in, we have not really applied either dynamic to the story of energy in Canada – even as postcolonial historians elsewhere are questioning energy as both a tool and legacy of colonization and global dynamics in terms of where it is produced and by whom and where its results might be transported. 59

31 Historians of Atlantic Canada have put a heavier emphasis on the costs of Confederation as an explanation for the fate of the region in the 20th century, when provincial and national paths diverged in the political woods, and the path travelled by Nova Scotia made all the (lamentable) difference. This is true as far as it goes: after all, getting lost in the woods is what happens when you turn inland, away from the coast. But Nova Scotia’s complicated and multi-faceted energy profile shows that it is important to take the long view, and not telescope history to 1867. The province’s commitment to unsustainable fossil fuels not only predated Confederation, but was and remained entwined with the demographic and political realities of a smaller entity in a larger federation. Fossil fuels, whether coal or offshore oil, have been seen as the means of escaping a status of inherent disadvantage, although history has not borne this out. But history also reminds us that there is more to Nova Scotia than coal (or oil): there is a second tradition of entrepreneurial, self-reliant, and globally minded thinking, supported by other energy sources – energy sources to which the province is now returning. In 2012, the provincial energy minister commented “Nova Scotia has one of the best wind regimes in North America. The wind itself is free . . . .”60 The wind, Joseph Howe might add, would not be the only thing.