Articles

Equality Deferred:

The Origins of the Newfoundland Human Rights State

Le Canada s’est doté du régime de protection des droits de la personne le plus perfectionné du monde, et pourtant les conditions locales ont conduit à l’émergence et à la mise en œuvre de lois sur les droits de la personne. Terre-Neuve en fournit un exemple typique. L’appui médiocre du gouvernement terre-neuvien à la politique des droits de la personne illustre comment les gouvernements peuvent restreindre l’application du droit. De plus, la prédominance des plaintes pour discrimination sexuelle jette un éclairage particulier sur la dynamique des inégalités entre les hommes et les femmes durant cette période. En dernier lieu, cette étude de cas met en lumière le rôle crucial exercé par les mouvements sociaux dans la mise en œuvre de lois sur les droits de la personne au Canada, qui historiquement a été conditionnée par la participation d’acteurs non étatiques.

Canada has constructed the most sophisticated human rights legal regime in the world, and yet local conditions have determined the emergence and implementation of human rights law. Newfoundland is an ideal case study. The government’s lackluster support for human rights policy demonstrates how governments can inhibit the application of law. In addition, the predominance of sex discrimination complaints offers a unique insight into the dynamics of gender inequality during this period. Finally, this case study demonstrates the critical role that social movements have played in implementing human rights law in Canada, which has historically depended on the participation of non-state actors.

1 FRED COATES, THE DIRECTOR RESPONSIBLE FOR ADMINISTERING the Newfoundland Human Rights Code, prepared a detailed memorandum for the Minister of Manpower and Industrial Relations in 1976 outlining how provincial statutes violated the Newfoundland Human Rights Code.1 The list of discriminatory practices, especially with regards to women, was striking. Women, for instance, had only been permitted to sit on juries as of 1972 and, as late as 1979, female civil servants were required to retire upon marriage unless the minister gave them permission to keep working. Women working at Memorial University (not including faculty) were also required to quit after they were married.2 The minimum wage for women, in 1970, was $0.50/hr compared to $0.70/hr for men. Women in the civil service received lower pensions, could not claim their pension until they were 65 years old (60 years for men), and could not receive compensation if they were injured on the job. Outside the civil service, women in Newfoundland were prohibited from changing their surname while married, unmarried girls (not boys) under 16 years old were banned from employment without parental consent, and a married woman’s place of residence (for elections) was based on her husband’s address even if the spouses were living apart. And the Family Relief Act implied, according to Coates, that being an unmarried female was a disability while the Limitations of Actions Act apparently placed married women in the same category as persons of unsound mind. Overall, Coates identified 20 discriminatory statutes.3

2 From their inception until the early 1980s, most of the complaints submitted to human rights commissions in Canada involved race or sex discrimination. In Ontario and Nova Scotia, both with substantial African-Canadian populations, the highest number of human rights complaints involved race; the second most complaints came from women. In every other province sex discrimination complaints predominated. This was unsurprising given the prevalence of sex discrimination at the time, the increasing number of women entering the workforce, and because women constituted the largest class of people under the legislation.4 Perhaps for this reason, Coates focused on sex discrimination in his 1976 memorandum. The government of Newfoundland eventually amended its laws to conform to provincial human rights legislation and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.5 For women, at least, human rights laws transformed their legal status in the province.

3 Far too many studies of human rights focus on international treaties and institutions to the detriment of local studies. As American human rights scholar Julie Mertus argues in her recent book, “among human rights advocates, the dominant wisdom is that the promotion and protection of human rights rely less on international efforts and more on domestic action.”6 In this vein I argue that it is essential to consider the history of human rights in a local – in this case, Newfoundland – context, and this includes the existence of a predominantly denominational education system, the lack of political support for the law, and the lack of both visible minorities and commission funding (most studies of human rights law in Canada focus on Ontario, where a majority of complaints dealt with race and where the commission was relatively well funded). I also argue that, prior to the 1980s, provincial government support for the human rights state in Newfoundland was intermittent and often lukewarm. As a result, the history of the Newfoundland human rights state is an example of how the state can (indirectly) inhibit the application of law. Finally, I argue that the Newfoundland experience illustrates how social movements can be integral to the human rights state.7 The Newfoundland Federation of Labour (NFL), the Newfoundland Status of Women Council (NSWC), and the Newfoundland-Labrador Human Rights Association (NLHRA) promoted awareness of human rights legislation, lobbied for legislative reform, and facilitated the complaints process. Thus, the success of the human rights state in Newfoundland depended on the participation of non-state actors.

4 The “human rights state” refers to laws that bind the state to enforce human rights principles, as well as their enforcement mechanisms. Human rights legislation, administered by human rights commissions, is the most visible manifestation of the human rights state in Canada. The first anti-discrimination laws were introduced in several provinces in the 1950s, and were later consolidated into expansive human rights laws. Human rights laws initially prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, religion, and ethnicity. Over time they expanded to include other prohibited grounds such as sex, disability, place of origin, and age. The law applied to services, employment, and accommodation, although, in practice, the vast majority of complaints dealt with race and sex in employment.8 Every Canadian jurisdiction introduced human rights legislation between 1962 and 1977. In Newfoundland, Premier Joseph R. Smallwood presided over the passage of the provincial human rights code in 1969.9

5 Studies of human rights laws in Canada form a small but increasing component within the Canadian historiography about human rights; only R. Brian Howe and David Johnson have produced a book-length study.10 Recent studies by Janet Ajzenstat, Dominique Clément, Michel Ducharme, and Christopher MacLennan have examined both the impact of rights-talk on political discourse and the proliferation of legislation since the 1960s to protect rights. 11 Clément and MacLennan also argue that a declining influence of parliamentary supremacy on Canadian politics and law set the stage for a constitutional bill of rights in 1982. Others have documented how 20th-century rights discourse spawned new social movements or helped transform old ones.12 Carmela Patrias and Ruth Frager, as well as MacLennan, Miriam Smith, and James Walker, have further argued that grass- roots mobilization has been central to legal reform.13 By contrast, Howe and Johnson’s study of human rights laws credits the state with innovations in modern human rights law. This article complements the literature by drawing on similar themes: the relationship between human rights commissions and both the state and social movements, the impact of human rights laws, and the implications of underfunding human rights commissions. It will explore the ways in which local events, actors, and issues have influenced the adoption and enforcement of human rights law.

6 Newfoundland was one of the last provinces to introduce anti-discrimination legislation when the government passed the human rights code in 1969.14 The province’s delay can be explained by a number of factors, including the perceived lack of ethnic or racial discrimination. Smallwood, for example, insisted that “we have no racial discrimination. I know of no part of North America that even compares with Newfoundland in its racial tolerance.” William Keough, the minister of labour who drafted and introduced the legislation in 1969, shared this view: “I can honestly say that I know of no case of racial and ethnic discrimination that has taken place in this province.”15 Another factor was the initial absence of social movement organizations lobbying for such legislation. The Jewish Labour Committee (JLC), for example, was at the forefront in lobbying for anti-discrimination legislation in several provinces but had no presence in Newfoundland.16 Elsewhere, the influx of immigrants to fuel the post-war economic boom in Canada’s major economic hubs, combined with dramatic instances of discrimination, had forced politicians to confront such issues. Although Newfoundland’s legislation was influenced by this wider national experience, the province remained the most demographically homogenous in the country. 17 Public indifference could also explain the failure to act. During a national conference on human rights held in Ottawa in 1968, the Newfoundland-Labrador Human Rights Committee (NLHRC) advanced just this interpretation: “We may not have the kind, or the magnitude, of the problems that may exist in many of our sister provinces but to say we do not have any problems would be a denial of the facts. . . . The attitude, by and large, is one of apathy and indifference by many of our people and the press in particular.”18

7 Hence, it took the International Year for Human Rights (1968) to provide an impetus for the creation of the human rights state in Newfoundland. The government itself established the NLHRC (later known as the NLHRA) to organize educational events promoting the anniversary of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In addition, the government formed a cabinet committee to consult with the human rights committee and recommend new legislation for the province.19 The committees jointly recommended the implementation of expansive human rights legislation and, within a year, the Smallwood government passed the Newfoundland Human Rights Code. The code contained two important innovations: it was the first Canadian jurisdiction to prohibit discrimination on the basis of political opinion, and it was only the second jurisdiction (after British Columbia earlier that year) to ban sex discrimination in employment.20 Otherwise, the statute’s basic framework was similar in every respect to other human rights laws in Canada. The code prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, religion, colour, or ethnicity, as well as national or social origin. It applied to employment, accommodation, and services.

8 The statute, as was the case in other jurisdictions, had many limitations. The equal pay provisions only applied to the “same work” in the “same establishment” – a remarkably narrow definition that would prevent any application to the vast majority of employed women. The lower minimum wage for women in the province remained in force for all-female workplaces.21 Moreover, the Newfoundland code, like the British Columbia Human Rights Act (1969), only prohibited sex discrimination in employment. Sex was not included in the sections banning racial, ethnic, and religious discrimination in services, accommodation, and the display of signs. The government of British Columbia never explained the omission, and William Keough only partly addressed the issue in the Newfoundland House of Assembly: “You will note that sex is not included in the accommodation practices provisions of this Bill. We did not think it proper for instance that the male should have the right in law to demand accommodation to an institution operated exclusively for the accommodation of females.”22 In addition, both provinces allowed sex discrimination if the employer could demonstrate a “bona fide occupation requirement.” The term was not defined in either statute, and no other grounds for discrimination, such as race or ethnicity, were similarly qualified.

9 The Newfoundland legislation was also noteworthy because it exempted all educational institutions. Other jurisdictions in Canada offered similar exemptions, but only in Newfoundland did religious groups hold a monopoly over public education. Confederation in 1949 with Canada was bitterly contested in Newfoundland, and might not have occurred without a provision in the Terms of Union to entrench denominational education.23 The exemption from the code insulated the entire school system, which was a major employer and service provider in the province. The NLHRC had been critical of the denominational education system, and its successor, the NLHRA, would later claim that the system actively discriminated on religious grounds. The education system’s supporters, by contrast, argued that the law protected minority and religious rights.24 Education would emerge as a major human rights issue in the province.

10 The legislation also did not provide for an effective enforcement mechanism. In Ontario, a permanent human rights commission, together with full-time human rights officers, enforced the human rights code. Ontario’s human rights officers were responsible for receiving and investigating complaints. If an individual had a legitimate complaint, the officer would first attempt conciliation between the two parties. If this failed, the commission could recommend that the case be sent to an independent board of inquiry appointed by the minister of labour at which the commission itself would represent the complainant. Complainants thus did not have to shoulder the burden of investigating and litigating the complaint, which was one of the major obstacles to seeking remedy through the courts.25

11 In Newfoundland, by contrast, the Smallwood government did not establish a standing human rights commission. Instead, it hired a commissioner, Gertrude Keough, and a director, Fred Coates. Coates was responsible for the day-to-day operations of administering the law (i.e., receiving and investigating complaints), essentially ran the entire program, and reported directly to the minister; Keough’s role was simply to chair the occasional inquiry.26 Coates was responsible for forwarding complaints to the minister of labour if an investigation substantiated the complaint. A minister, if convinced that a complaint was justified, could “activate” an ad hoc human rights commission (a formal inquiry) by asking Keough to chair the inquiry and recommend a course of action. The practice placed enormous power in the hands of the minister to determine the validity of complaints, and was stridently criticized in the 1973 Report of the Committee on Government Administration and Productivity.27 To be sure, Newfoundland was not alone: Nova Scotia, Alberta, and Prince Edward Island initially delayed the creation of permanent human rights commissions for several years.28 Without a permanent commission to fulfill the human rights state’s adjudication, education, and enforcement process, however, the legislation was largely ineffective.29 There was no agency responsible, for instance, for representing the complainant before a board of inquiry. In 1974, the legislation was amended to create a permanent commission; however, Keough and Coates were the only members of the commission. As director, Coates continued to be responsible for administering the legislation and, after 1974, participating in commission hearings whereas in other jurisdictions, such as Ontario or British Columbia, the director would represent complainants in the commission hearings.30 Except for Prince Edward Island, the other provinces recognized the need for an impartial hearing, and separated the process of receiving and investigating complaints from adjudication.31

12 Smallwood’s decision in 1971 to appoint Gertrude Keough as commissioner was controversial (under the 1974 legislation her formal title changed to chief commissioner). The wife of the recently deceased minister of labour, Keough admitted that she knew little about the legislation or the issues.32 The Evening Telegram and the NLHRA, both of which were critical of the Smallwood government at this time, opposed her appointment, interpreting it as a reflection of the government’s refusal to establish a strong human rights state. Keough may not have been the ideal choice, but her appointment should be considered in context. The chair of a government commission was invariably a political appointment, and politicians across Canada had been hard-pressed to find individuals with appropriate expertise to guide commissions in their infancy. Human rights commissions, after all, had never existed before, and experts in human rights adjudication were simply not available in 1969. As her daughter later insisted, Keough

did not have specific expertise in the area, but very few would have in this period. Furthermore, she was the recent widow of the Minister of Labour who had just drafted Newfoundland’s first human rights legislation, so she knew more about the issues than many. While the Evening Telegram may have looked disdainfully upon her as some “little woman” who had been plucked from the obscurity of the kitchen . . . the lives of politicians’ wives in this period were usually much more complex. [Gertrude] was a college- educated former teacher who was very engaged with her husband’s work and who frequently hosted and attended gatherings in which the social and political issues of the day were discussed. She was also very much involved in community work and engaged with the world around her. She was well read, devoured newspapers, and watched the CBC news. . . . She was no “little woman.”33

13 In practice, Keough’s role was limited to chairing commissions and acting in a supporting role. The relationship between the two key figures in the Newfoundland human rights state was friendly and respectful. Coates communicated regularly with Keough, and they met on occasion to discuss their work. Still, Keough’s role was strictly limited, and ultimately it was Coates who was the driving force behind the program. Coates was a former Toronto police officer who had been born and raised in Newfoundland, and had returned to the province in 1961 to start his own food catering business. A future mayor of Conception Bay South, he was an inspector for the Tourism Bureau when Smallwood appointed him in 1971 (he served until 1984).34 Except for a stenographer, the only other staff member assigned to the commission was Herbert Buckingham, a lawyer within the Department of Justice who provided part-time legal advice. During the early years, therefore, Coates faced the impossible task of administering the province’s entire human rights program across a broad geographic area with, in effect, no staff and no resources. A full-time investigator was not hired until 1982.35 In contrast, most provinces began training a cohort of professional human rights investigators in the 1970s.36 New Brunswick had at least two investigators as early as 1975, and Manitoba employed seventeen staff by 1979 (including eight investigators). Saskatchewan and Prince Edward Island also employed at least two staff members by 1981.37

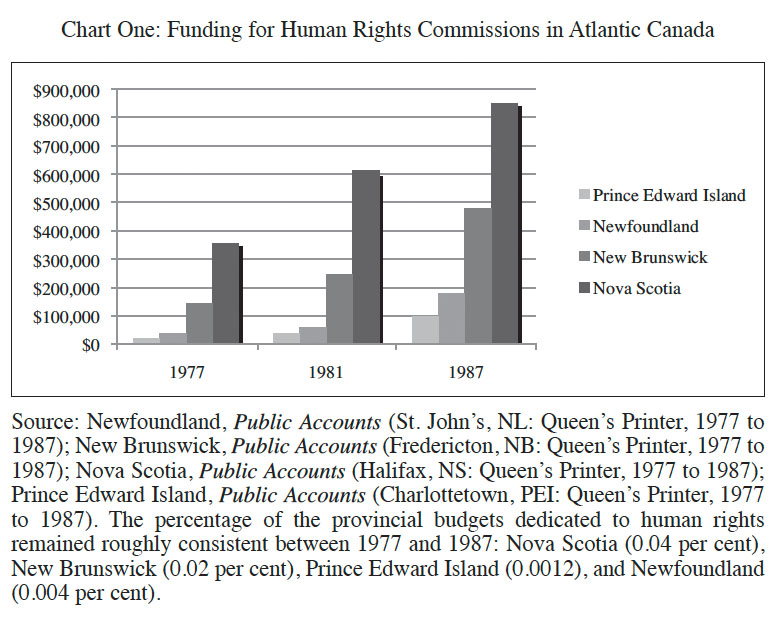

14 By refusing to hire adequate staff, the government effectively undermined the human rights state. On a per-capita basis, Newfoundland provided the least amount of funding for its human rights program of any of the other Atlantic provinces – not that other provinces were especially generous (see Chart One). Human rights commissions in Canada have a long history of being underfunded and understaffed. But Newfoundland stood out in the 1970s for starving its human rights program. A review of government administration in 1972 noted that the “Commission has no funds to enable it to undertake research or to engage in even minimal public relations.”38

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 115 Coates did respond to complaints. Over the years he recommended formal inquiries on a broad range of issues, from employers firing individuals because of their religion to discrimination within a company town. Primarily, though, he dealt with sex discrimination complaints. He had barely moved into his new office when he received complaints surrounding discriminatory job advertisements. The Evening Telegram routinely published advertisements for employment restricted to men or women, or for people over 25 years old. The Department of Social Services in 1972, for instance, insisted on advertising for male welfare officers in the Telegram because, as the department told Coates, “there are bona fide qualifications which we consider to be particularly male in nature.”39 In its defense of an advertisement for female clerical staff over 25 years old – who had to be unmarried as well – Marystown Shipping Enterprise explained that “we requested a female employee simply because our Accounting Office is female oriented. . . . Continuity of employment is an important factor, [and] from this point of view young married women would not, for obvious reasons, be a suitable candidate.”40 Despite repeated protestations from the NLHRA, Coates mailed these businesses copies of the legislation and let the matter drop.41 Where Coates was proactive was in making the minister aware of numerous examples of state policies that discriminated against women. In addition to the laws he identified in his 1976 memorandum to the minister of justice, which are described in the introduction to this article, he discovered a policy requiring single mothers to name the father of their children if they wished receive social assistance. Another policy required pregnant civil servants to provide proof that any day off work was not due to pregnancy. Gender was also a factor in determining candidacy for becoming a foster parent. As well, women were routinely denied employment and paid lower wages in the public and in the private sectors. According to the 1974 Royal Commission on Labrador, for instance, the largest employer in the region – the Iron Ore Company – had an unofficial policy of not hiring married women. The commission also found that in Davis Inlet the provincial government paid men higher wages for working overtime in manual labour than it did women.42

16 Newfoundland was no different from most other provinces in facing a large number of sex discrimination complaints. Still, at times, the human rights state had to respond to local circumstances. One of the most challenging early cases was a complaint from a former employee of the Iron Ore Company. Joel Seaward was fired for being drunk at work and was banned from venturing onto company property. Seaward never denied that Iron Ore had legitimately fired him, but he soon found that nobody else would hire him in this company town and that he faced eviction from his company-owned home. Five other former employees of Iron Ore, fired for drunkenness, theft of company property, or participating in illegal work stoppages joined Seaward in a hearing against the company before a human rights commission. The complaint ultimately failed because the case did not fall within the categories of discrimination outlined in the code, although the commission did ask the company to desist voluntarily from discouraging other employers from hiring former employees.43

17 When he was not preoccupied with administrative duties or investigating complaints, Coates endeavoured to go to local schools, unions, and government agencies to promote the legislation. Without sufficient funding, however, he was unable effectively to fulfill the statutory mandate of educating the public.44 And education was a significant component of the human rights state.45 The mandate of the human rights state was prevention; punishment was a last resort. Education was thus a critical component of the human rights state, and one of the most important duties of a human rights commission.46 Expansive human rights education programs were undertaken in other provinces in the 1970s. Newfoundland, though, had no similar program. As Coates admitted in 1978, the commission had yet to produce any educational materials.47

18 Social movement organizations helped to fill the gap. The government was fully aware of the commission’s non-existent education program in these early years, and in fact hoped that the NLHRA would fulfill the role of educating the public.48 By the mid-1970s the NLHRA was a fully independent advocacy group with funding from the federal secretary of state. Biswarup Bhattacharya, a psychiatrist at the Waterford Hospital, was the president throughout the 1970s. The group claimed dozens of members as well as a board of directors that included lawyers, novelists, professors, teachers, and other professionals in St. John’s concerned with human rights.49 The NLHRA soon became a leading force for promoting human rights education. In 1976, for instance, the NLHRA secured a major grant from the federal government’s Opportunities for Youth program to conduct a survey and publish a booklet on Newfoundlanders’ awareness of their legal rights.50 The province also provided the NLHRA with funding for human rights education, including a $37,000 grant in 1984 for high school workshops.51 The NLHRA organized seminars, public lectures, education fairs in schools, and press conferences; submitted articles to local newspapers; and produced educational flyers about human rights and the role of the commission.52 The NLHRA, as well as the Newfoundland Federation of Labour (NFL) and the Newfoundland Status of Women Council (NSWC), also conducted extensive research throughout the 1970s, particularly in the area of equal pay. The organizations used this research to lobby for legislative reforms and to sensitize the commission to the challenges facing women workers.53

19 The commission was routinely criticized for having a low profile in the community, which was exacerbated by the lack of funding for education and promotion. In 1973 Coates admitted in a letter to Daniel G. Hill, former chairman of the Ontario Human Rights Commission, that “very little was going on” and that there was little attention to human rights issues in the province.54 And the minister of labour was often confronted in the legislature during this period about the commission’s poor visibility and inactivity.55 Given the commission’s non-existent education program, it is not surprising that the agency was largely unknown for most of the 1970s.56 The Department of Justice admitted in the early 1980s that the “commission has had a very low profile over the years.”57 Thus, despite the signs of vigour emanating from the NLHRA and other organizations outside the commission itself, the human rights state in Newfoundland had made only a tentative beginning. However, the seeds of reform had already been sown.

20 The Newfoundland Human Rights Code underwent a series of amendments in the 1970s and 1980s.58 It was amended four times in fifteen years to include new prohibited grounds of discrimination: sex and marital status (1974), physical disability (1981), sexual harassment (1983), and mental disability (1984).59 The government also established a permanent human rights commission in 1974. Many of the amendments were an attempt to respond to some of the demands from social movement organizations. The NSWC, for example, lobbied the government to add marital status and a right to childcare to the statute, to eliminate the loopholes for equal pay, and to establish an office in Labrador.60 The NLHRA repeatedly accused the commission of failing to promote awareness of the code. And the NFL, which first addressed the human rights code in its 1974 annual report, was equally critical of the government’s human rights policy: “The indifference to the Human Rights Commission on the part of the government means that Newfoundlanders have less protection in this area than any other province of Canada. . . . This is an intolerable situation and should be corrected immediately.”61

21 The NLHRA, NSWC, and NFL campaigned extensively to reform the government’s weak legislation. The 1974 reforms represented for them an important victory in areas such as prohibiting sex discrimination in accommodation and services, banning discrimination on the basis of marital status, broadening the equal pay provision to “similar work” (as opposed to the same work, albeit within the same establishment), and, of course, the creation of the permanent human rights commission. As Edward Maynard, Minister of Manpower and Industrial Relations, put it: “I would single-out the Newfoundland-Labrador Human Rights Association and the Newfoundland Status of Women Council for their tremendous assistance in providing comprehensive briefs relating to the Amendments.” Maynard later acknowledged the NFL’s role as well.62 Although the government ignored recommendations to separate the investigation and adjudication process, transfer the commission from the Ministry of Labour to Justice, increase fines, and remove the exemption for educational institutions, all but the exemption for educational institutions were later adopted.63

22 Yet still Coates struggled to fulfill his legislative mandate, while the rarity of formal inquiries greatly limited Keough’s activities as chief commissioner. By 1976 the commission had received and investigated a mere 260 complaints. In contrast, New Brunswick had received hundreds more and had investigated 698 cases between 1969 and 1976.64 There are no records for the Newfoundland commission between 1977 and 1984, except for 1980 (when the commission investigated 160 complaints). That year, however, appears to be an anomaly: between 1985 and 1989 the commission investigated a total of only 289 complaints.65 And in very few cases did the complaints lead the minister to appoint a formal inquiry. Human rights commissions (the equivalent of a board of inquiry in other jurisdictions) represented the most powerful weapon available in the human rights state’s arsenal. A commission could require employers to pay lost wages or rehire a former employee, force people to provide a tenant with accommodation, offer a service, or simply apologize. The government appointed 18 formal inquiries between 1971 and 1988.66 In other words, the vast majority of complaints received by the Newfoundland Human Rights Commission were either dismissed or settled informally.67

23 By comparison, the record across Canada was mixed. The New Brunswick Human Rights Commission investigated hundreds of complaints but only appointed 19 formal inquiries by 1995.68 A similar situation prevailed in Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, and Alberta. In contrast, hundreds of formal inquiries were appointed in other provinces, including Nova Scotia and British Columbia. But Newfoundland was firmly in the category of those governments that were unwilling or unable to dedicate sufficient resources to sustain a commission and allow it to investigate complaints and educate the public. The budget for the Human Rights Commission was barely 0.004 per cent of the provincial budget (see Chart One); doubling or tripling the budget to hire staff and fund education programs would have had a negligible impact on the province’s finances. Coates identified this state of affairs as early as in 1973, and suggested that there was a lack of support in the government: “Maybe it was the indecision of the Committee to establish clear cut ground rules for the agency or, perhaps it was because one or more of the senior civil servants may have reacted in an overly cautious manner towards the activities of the agency that the agency has been curtailed in its activities and that an isolationist, don’t rock- the-boat attitude has been imposed on the Human Rights agency in our Province.”69

24 Social movement organizations offset this attitude at least partially through their influence on the complaints process. Volunteers with the NSWC pored over newspapers to identify discriminatory job advertisements, and then contacted employers to inform them that they were violating the code.70 Volunteers with the NLHRA often investigated human rights violations on their own or referred complainants to the commission. At times the NLHRA even appeared to be doing the commission’s work.71 A young man in Corner Brook, blind in one eye, was refused entry into a machinists program in 1982 until the NLHRA intervened and convinced the college to admit him.72 Bhattacharya, as NLHRA president, described other incidents as follows:

For an example, one day Mrs. X phones me, stating that she was being wrongfully evicted. I contacted the landlord who had no time for our Association and was not interested in Mrs. X’s problem, either. Having come to an impasse, I then contacted his lawyer who listened to me with sympathy and finally revoked the eviction order. In another case a man’s livelihood depended on having his own car. For financial problems his car was taken away from him. After much discussion with the creditors and the lawyer this was averted and the man retained his car. 73

The NLHRA also found itself responding to cases involving substandard housing for children, landlords abusing their tenants, mentally ill patients not receiving proper medical attention, police abuse of prisoners, child abuse, and individuals falsely detained at a psychiatric hospital. Often the organization successfully intervened to settle complaints informally. Similar to the volunteers with the NSWC, in many cases the organization simply called employers to inform them that they were (often unwittingly) violating the Newfoundland Human Rights Code and the issues were resolved.74 In this way, the NLHRA was as central to the functions of the human rights state as the commission.

25 In those rare cases when complaints reached a formal inquiry, the success rate varied. Between 1971 and 1977 the minister appointed five human rights commissions or formal inquiries. Two cases involved adherents of the World Wide Church of God who were fired for refusing to work on the Sabbath; one was a bus driver who refused, for no apparent reason, to carry a passenger; one was a female janitor who was paid less than a man doing the same work; and one was a complaint against the Iron Ore Company of Canada for discriminating against former employees. Three additional cases, all involving workplace sex discrimination, reached the commission stage in 1982. Only three of the eight complaints were successful.75

26 Few records have survived on complaints to the human rights commission. As of 1986, however, the general trend remained the same. Most of the commission’s work involved sex discrimination in employment and only a handful of cases reached formal inquiries. One woman was fired for being pregnant; she was awarded a $2,500 settlement. Another was refused a job as a security guard because, according to the employer, businesses did not want female guards. Several women complained to the commission about sexual advances from their employers, or of having to deal with sexist comments, and were often awarded $1,500 compensation. One taxi-driver stand operator ordered all women to stop driving after 10:00 pm until the commission’s investigator convinced him to stop the practice. Eighteen women at a St. John’s hotel filed a complaint in 1987 when their employer threatened to fire them if they did not sign their names to cards to be placed in guest rooms reading “A Goodnight Kiss.”76 The files suggest that, in these cases at least, the commission successfully fulfilled its mandate.

27 Indeed, if it could be said that the human rights state in Newfoundland had any genuine impact at all by the 1980s, it would be in the area of sex discrimination.77 As Keough’s children later recalled, the chief commissioner was especially interested in equal pay:

We do remember, though, that the notion of equal pay for equal work was relatively new when the commission was created, and there was a lot of work to be done on that front. [For instance], the “broom-size” case, in which men were being paid more to do the same janitorial job because they used bigger brooms. . . . Memorial University well into the 1980s rationalized that the tech services ‘guys’ – and there were no gals in those days – with the same education and years of experience as secretaries running whole departments had to make more money because they were supporting families. Mom was appalled by this kind of reasoning, and worked towards achieving equal pay for work of equal value.78

28 The human rights state resulted in equal pay for many women, especially in the civil service. After the human rights code came into effect in 1971 the provincial government added $805,000 to female public servants’ salaries to comply with the law’s equal pay provisions.79 In addition, the government amended a host of statutes (or changed policies) to end blatantly discriminatory practices: female civil servants were no longer required to ask permission to keep working after marriage; the separate minimum wages were eliminated; women were allowed to sit on juries; civil servants’ pensions were no longer determined by gender; married women could change their surname; and a married women, living separately from her husband, no longer had to use his place of residence for elections.

29 These achievements notwithstanding, Newfoundland continued to struggle with the legacy of a weak human rights state. Even the lengthy appointment of the commission’s first chairperson came to symbolize this legacy. The Conservative government of Frank Moores (1972-1979) had asked Keough to remain chief commissioner.80 When she retired in 1981 at the age of 70, Keough was the oldest and one of the longest-serving commissioners in Canada. That she was the only full- time commissioner until the early 1980s hampered the commission’s activities. There was also a perception in government circles by that time that “a more dynamic person” was needed but that Keough’s lack of pensionable service was an obstacle to her retirement.81

30 More generally, by the early 1980s significant reforms and resources were necessary to reform the flawed model the Smallwood government had created in 1969 and which Moores’s administration did nothing to address. The Newfoundland Human Rights Commission had continued to operate on a meager and piecemeal basis. Whereas most provinces were able to establish regional offices, the Newfoundland commission did not have the resources to expand outside St. John’s. There were several consequences arising from this geographical limitation, including the complete absence of Aboriginal people from the commission’s files (although confusion over jurisdictional issues and sheer Aboriginal mistrust of government were other likely factors).82 Furthermore, the government had failed, by the mid-1980s, to provide adequate resources for an education program on human rights in any part of the province. Despite the efforts of various social movement organizations, the Newfoundland human rights state had yet to mature fully by the early 1980s. Activists faced immense obstacles to organizing campaigns in Newfoundland, such as the lack of resources as few organizations in St. John’s had the same resources as their counterparts in major cities across Canada. Limited immigration to the island may also have contributed to a lack of organizations specifically representing minorities.83 Given the extent to which such organizations had prompted the success of the human rights state in other provinces, it is perhaps understandable that the human rights state was especially weak in Newfoundland.84 Until 1981 the entire budget of the human rights commission was nothing more than two salaries.85 The commission’s budget continued to lag behind Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, topping only Prince Edward Island throughout the 1980s (see Chart One).

31 Newfoundland’s Conservative government under Brian Peckford (1979-1989) initiated several reforms, including a substantial increase in the commission’s budget. After Keough retired in 1981, the government replaced her with six part-time commissioners located throughout the province, thus finally making an effort to extend the commission’s operations outside the Avalon Peninsula. The human rights program continued to depend largely on Coates’s work, although in 1982 Gladys Vivian was hired as a full-time human rights investigator (and subsequently more staff would join the commission). Thanks to the increases to its budget, the commission was able to initiate its first education program during the mid-1980s.86 And yet even the Peckford government continued to provide less funding than any other province in Canada. Per capita spending for human rights in the other provinces was between $0.65 and $1.37 in 1988; per capita spending Newfoundland was $0.38.87

32 The provincial government made other changes to the human rights state in response to activists’ continued demands for reform, which stretched back to the early 1970s. In 1980, after extensive lobbying from women’s rights organizations in the province, the government established an arm’s-length Provincial Advisory Council on the Status of Women to advise the government on women’s issues.88 Soon after, the council joined forces with the NSWC, a grass-roots women’s rights organization, to lobby for extensive reforms (especially the weak provisions on equal pay).89 Meanwhile, the NLHRA was still frustrated with the commission’s low profile. The president of the NLHRA, now William Collins, wrote to Premier Peckford in 1981 to lament the commission’s failure to fulfill its basic mandate. “I am sure you are aware,” he stated, that “the Human Rights Commission in Newfoundland has been completely ineffective. . . . We [the NLHRA] have been doing the work, which . . . should have been done by . . . paid civil servants.”90 Despite extensive lobbying campaigns by all three organizations to strengthen the law’s section on equal pay, they had failed to secure even modest changes in this area.91

33 Still, the Peckford government was partially responsive. St. John’s City Council became embroiled in a controversy in 1983 when it acceded to pressure from a citizens’ group in Amherst Heights to withdraw support for a transition home for the mentally disabled. The debate contributed to the government’s decision in 1984 to add disability to the human rights code.92 Then, in 1988, the Peckford government introduced an entirely new human rights code.93 Sexual harassment was added to the statute, as was a supremacy clause: the human rights code would henceforth override other provincial laws. Most importantly, the procedures for dealing with complaints were altered. If informal conciliation was unsuccessful, the human rights commission, rather than the minister, was responsible for dismissing the complaint or forwarding the case to an independent board of inquiry.94 Moreover, members of the commission were not permitted to sit on the board of inquiry; instead the commission represented the complainant before the inquiry. In these ways, the Peckford administration had gone much further than any previous government to create a viable human rights state.

34 Yet limitations persisted. Debates erupted in other provinces during this period surrounding the question of whether or not to ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.95 Not only did the Newfoundland government refuse to follow Ontario and Quebec’s lead by adding sexual orientation,96 but indeed the 1988 legislation was almost jettisoned when the cabinet became embroiled in the debate over sexual orientation.97 Two years later the issue continued to divide policy- makers. Paul Dicks, the minister of justice in 1990, feared that the amendment would protect pedophiles and insisted that such discrimination did not exist in Newfoundland. The commission’s files indicate that it never investigated a case of discrimination against gays and lesbians before 1993, even though at least two such incidents were documented by the NLHRA in 1990.98 Significant as the 1988 reforms were, the debate surrounding sexual orientation demonstrated policy- makers’ continued ambivalence towards the human rights state. Except for Prince Edward Island and Alberta, every other jurisdiction in Canada had banned discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation before Newfoundland did the same in 1997.99

35 Undoubtedly, however, the continuing limitations on the human rights state were best exemplified in a debate prompted by the unique status of denominational education in Newfoundland, where secular schools did not exist and Christian churches monopolized state-funded education. This situation resulted in numerous actions that elsewhere would have been deemed human rights violations. Teachers were fired for not following the tenets of their school’s denomination, such as restrictions on marriage outside the church.100 Voting or standing in consolidated school board elections required belonging to the Salvation Army, Anglican, Presbyterian, Pentecostal, or United churches.101 Discrimination also affected students. Even though restrictions might be informally waived at times, the system as such disallowed students from attending neighbourhood schools if they were not of the proper religion, and children could be “bumped” from over-registered enrichment programs because of their religion.102

36 A case involving a teacher had brought the denominational education system under close scrutiny in 1972, when Judy Norman sought a teaching position soon after her graduation and refused to indicate her religious affiliation on an employment form. The school board rejected her application.103 Coates later recalled how emotionally charged the issue was in Newfoundland:

This particular individual who had just received a teaching certificate, felt it was discriminatory to ask what her religious beliefs were. So consequently she couldn’t get a job anywhere. But two different denominations, two men of the cloth, went to bat for her, and of course consequently both of them got themselves transferred outside of Newfoundland. And she later got herself a job in Ontario. . . . I felt it was very, very narrow-minded. Very bigoted. But they were protected by legislation. There was no way of challenging it. The schools boards were exempted from the provisions of the Code. . . . It certainly shook the school boards that I went to visit at the time. But no way were they going to give that up.104

37 Denominational education was protected under the Terms of Union with Canada and was exempted from the provisions of the human rights code. Despite the strength of the feelings that Coates apparently entertained privately on the Norman case, even he was disinclined on pragmatic grounds to campaign for removal of the exemption: “I suggest there would be a possibility that the deletion of this Section would give many people the false impression that the various Denominational Education bodies would come within the ambit and be subject to the provisions of the Code when in reality there would be no change in the matter. There is a possibility that we would be subject to much harsher criticism as the facts became known and in the interim there would be the further possibility that we may have offended the people who are opposed to such changes needlessly.”105

38 Coates’s successor Herbert Buckingham, who served from 1971 to 1984, went further and vehemently defended the education system: “The denominational educational model is a fact of life in Newfoundland. . . . My hope and my wish is that the administrators of our educational system . . . will exercise their obligation to be preferential with the least possible adverse affects to persons who do not fall within the category for which preference is to be exercised. However, it is not an answer to accommodate persons outside the preference category to the detriment of those who have an established priority.”106 Buckingham acknowledged the discriminatory nature of the law, but he insisted in 1985 “the denominational education system is a fact of life in Newfoundland and is such because it is in accord with the wishes and desires of a large majority of the Province’s population.”107

39 It fell to the NLHRA to stir up public debates about human rights violations under the denominational education system.108 From its inception, the NLHRA had opposed the churches’ monopoly over education as the “greatest single threat to equality of religion and freedom of worship.”109 At a gathering of 120 people at Memorial University in 1987, Lynn Byrnes (president of the NLHRA) insisted that the system was “based on some very blatantly discriminatory policies which we feel must be changed. . . . If these legal rights allow such cut and dried examples of religious discrimination then the legal rights are wrong.”110 Whereas the human rights commission did nothing, the NLHRA kept the issue alive and lobbied for reforms. In 1985 the association caused a public stir when Byrnes engaged in a fierce debate with Archbishop Alphonsus Penney on CBC television. During that same year, the association polled election candidates and published their views on religious education.111 A few years later the association organized a province-wide petition campaign that included advertisements in newspapers across Newfoundland.112 The NLHRA played a prominent role in contributing to the eventual dismantling of the denominational education system, which occurred following two provincial referendums (in 1995 and 1997).113

40 The beginnings of the human rights state in Newfoundland, therefore, was complex in ways that suggest important conclusions not just for human rights history in the province itself but also for Canada as a whole. On paper, the human rights state was remarkably uniform across the country. Every jurisdiction introduced similar human rights legislation enforced by commissions with comparable mandates and enforcement mechanisms. And most human rights complaints in Canada involved racial or sexual discrimination in employment.114 Especially, though not exclusively, after the reforms of the 1980s, Newfoundland had a system akin to its counterparts across the country.

41 Yet there was an obvious disjuncture between uniformity on paper and the law in practice. On one hand, the human rights state in Canada was an impressive achievement. No other country had enacted such an expansive human rights state with strong enforcement mechanisms. Newfoundland followed other provinces in adopting the Ontario model in the 1960s and 1970s. Federalism, in this case, facilitated the measures that could lead to the creation of a strong human rights state from coast to coast. And yet, because of the federal division of powers, the provinces were responsible for enforcing human rights legislation. Enforcement therefore varied widely. The Newfoundland human rights state was starved for resources. Whereas citizens living in cities of similar size across Canada, such as Victoria, British Columbia, or Kingston, Ontario, had access to relatively strong human rights machinery in the 1970s, victims of discrimination living in St. John’s had much weaker mechanisms at their disposal. Even people living outside major cities in many provinces had access to regional offices of the provincial human rights commission. Saskatchewan, for instance, had three regional offices in 1980. Newfoundlanders did not have comparable access. Human rights protection, as a result, was unevenly distributed across Canada.

42 The history of the Newfoundland Human Rights Commission demonstrates the need to study local conditions so as to understand adequately the evolution of human rights law in Canada.115 In the case of Newfoundland, the government undermined its own legislation by not providing adequate resources for the human rights program. The viability of the human rights state depended on an actively supportive government, a condition that did not exist in Newfoundland in the 1970s and 1980s. Local social movement organizations partially filled the gap. Although the lack of organizations representing visible minorities was a limitation, organizations such as the NLHRS, NSWC, and NFL played a key role as part of the Newfoundland human rights state by promoting the legislation, facilitating the complaints process, and lobbying for reform. These developments, as well as human rights controversies such as denominational education, or specific complaints as in the case of the Iron Ore Company in Labrador, demonstrate how the human rights state was affected by the economic and social conditions facing the community. The results of it all were mixed. In addition to failing to contribute to the debate surrounding denominational education, the human rights state struggled even to address its core issue during the 1970s: sex discrimination. Women’s employment rate in 1980 was 15.1% and the median female annual income in the province was $4,980 compared to $10,259 for men. Because the legislation was restricted to “similar work in the same establishment,” it did not affect the vast majority of female workers clustered in clerical and service occupations.116 And according to the NFL, the government and private employers had not, by the mid-1980s, taken advantage of the provisions for affirmative action permitted under the legislation.117 The Newfoundland human rights state, though significant, was far from transformative. It was a symbol of equality, but all too often of an equality deferred.