Articles

“Not in the Atlantic Provinces”:

“Not in the Atlantic Provinces”: The Abortion Debate in New Brunswick, 1980-1987

La correspondance entre le gouvernement progressiste-conservateur du premier ministre Richard Hatfield et des militants pro-choix et pro-vie indique que le régionalisme et la religion étaient au cœur de l’idéologie pro-vie omniprésente et du rejet du mouvement pro-choix entre 1980 et 1987. Malgré des données statistiques prouvant que les services d’avortement n’étaient pas accessibles, le gouvernement a reçu l’aide de la communauté médicale pour adopter une loi contre l’avortement, qui interdisait les cliniques d’avortement et semblait maintenir le statu quo. Cet article offre une perspective régionale sur l’histoire de l’avortement au Canada mais, ce qui est plus important, il examine comment les croyances religieuses et culturelles ont façonné la politique et la société.

Correspondence between Premier Richard Hatfield’s Progressive Conservative government and pro-choice and pro-life activists indicates that regionalism and religion were central to the pervasiveness of pro-life ideology and the rejection of pro-choice arguments between 1980 and 1987. Despite statistical evidence that proved abortion services were inaccessible, the government received assistance from the medical community to pass anti-abortion legislation that prohibited abortion clinics and appeared to maintain the status quo. This article provides a regional perspective on the history of abortion in Canada, but it more importantly probes how religious and cultural beliefs shaped politics and society.

1 ON 14 MAY 1969 THE CANADIAN GOVERNMENT passed the long-anticipated omnibus bill C-150, which finally legalized abortion after it had been condemned as an indictable offence in 1892. An abortion was only legal and funded, however, if performed in an accredited hospital and approved by a hospital’s Therapeutic Abortion Committee (TAC), consisting of at least three physicians. The TACs were responsible for determining if the pregnancy endangered a woman’s life or health. Once the legislation was passed, the federal government handed over the abortion issue to the provincial governments, encouraging hospitals to set up TACs and decide who was eligible for an abortion. The bill immediately created dissatisfaction nationwide. Women’s liberation groups argued that women had the right to “abortion-on-demand” while anti-abortion groups asserted that abortions should only be performed to save a mother’s life. The abortion issue demonstrated an increasing division within Canadian society due to changing perceptions of women’s rights and motherhood.

2 While scholars of various disciplines have contributed invaluable and insightful works on abortion, the politics of abortion in Atlantic Canada remain under- investigated.1 This article focuses on the abortion debate in New Brunswick between 1980 and 1987, the period in which pro-life and abortion rights activists began to challenge the abortion law thus making it a political, social, and economic issue in the province. These concerns were expressed through letters sent to Premier Richard Hatfield’s Progressive Conservative government and to editors of various newspapers, pro-choice and pro-life newsletters, petitions, government statistics on abortions provided in and out-of-province, and inter-office memos. The various sources indicate that regional economic and political concerns as well as cultural beliefs were central to the strength of the pro-life movement and the rejection of pro- choice arguments in New Brunswick. Despite statistical evidence that proved abortion services were inaccessible in the province, the government strengthened restrictions on abortion services.2 With the assistance of the New Brunswick Medical Society and the College of Physicians and Surgeons of New Brunswick, the government passed a new law in 1985 that prohibited abortion clinics and appeared to maintain the status quo. In reality, the law highlighted the extent to which cultural, economic, political, and social forces shaped the government’s decision to decrease abortion services province-wide and pass an anti-abortion bill.

3 The article explores the emergence of provincial pro-choice and pro-life activism and their effect on government policy. Pro-choice activism increased during the 1980s due to the creation of organizations such as Planned Parenthood New Brunswick (PPNB), the New Brunswick Advisory Council on the Status of Women (NB ACSW), the Committee for the Retention of Abortion Rights, and the Canadian Abortion Rights Action League (CARAL) chapter in Moncton, as well as the advances made by abortion rights activist Dr. Henry Morgentaler in the province. I argue, however, that pro-choice advocates struggled to convince citizens that abortion was a morally justifiable act. The strong presence of religious activism in the province allowed the pro-life movement to strengthen, and subsequently access to therapeutic abortions decreased. By drawing on Ruth Fletcher’s theory of fundamentalisms, I demonstrate that fundamentalist beliefs were central to the strength of the pro-life movement. While pro-life activists opposed the termination of all pregnancies – not only abortions performed on religious adherents – the New Brunswick pro-life movement primarily focused on stopping hospitals from performing therapeutic abortions and preventing the establishment of abortion clinics in their region.3 Residents, such as G.G. from Grand Falls, requested that Hatfield “prevent Morgenthaler [sic] from setting up an abortion clinic in our province, or hopefully not in the Atlantic provinces.”4 In addition, citizens were concerned about the morality of abortion and about the economic consequences that might arise from funding out-of-hospital abortion services (e.g., being a further economic drain during a time of rising inflation and unemployment rates). Despite the concerns of pro-life activists, government memos indicate that the Hatfield government appeared to maintain a temperate approach to the debate in the early 1980s, and that this only changed when Morgentaler requested permission to open a freestanding abortion clinic in the province in 1985. By challenging the government to reconsider its stance on the issue, Morgentaler ironically compelled the government to pass anti-abortion legislation. This article situates the historical narrative about abortion in New Brunswick within the larger debate over the power of religious movements in shaping public policy.5

4 Before turning to the New Brunswick debate specifically, it is important to examine the pro-life/pro-choice dichotomy and its implications. Activists on both sides of the debate have long contested the use of the terms “pro-choice” and “pro- life.” Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, the pro-choice slogan changed in Canada from “free abortion-on-demand” to “a woman’s right to choose” – broadening the movement’s political and cultural appeal.6 Pro-life activists criticized the slogan, arguing that the pro-choice movement overlooked the foetus’s right to choose. In addition, some feminists asserted that pro-choice activists needed to validate women’s unpleasant abortion experiences, address the moral element of terminating pregnancies, consider men’s rights in the decision to choose an abortion, and examine how a feminist’s stance on non-violence might be contradictory to their willingness to abort foetuses. Feminist Kathleen McDonnell feared that if feminists did not respond to these developments they would become “rigid, stagnant and ultimately irrelevant.” She warned feminists of the limitations of the term “choice,” asserting that women were often coerced into abortions because of their socio- economic conditions or because the foetus might be physically disabled.7 The term “pro-life” was similarly criticized by feminists as they argued that the criminalization of abortion would force women to seek back-alley abortionists and risk their lives. Therefore, pro-choice activists asserted that the pro-life movement was full of contradictions and did not value the life of the woman. To broaden their own appeal, debunk the opposition, and restore credibility to their ideology, transnational pro-life organizations often referred to pro-choice groups as “pro- death” whereas pro-choice organizations substituted “anti-choice” for pro-life.8 This article uses the terms “anti-abortion/pro-life” and “pro-choice” to ensure consistency and historical accuracy, as they were the terms used by the New Brunswick media, government, and activists throughout the 1980s.

5 The pervasiveness of pro-life ideology in the late 1970s and 1980s was influenced by the rise of the New Right in the United States and fundamentalist groups throughout Europe. After the United States Supreme Court liberalized abortion in 1973 in Roe v. Wade, Protestant fundamentalists joined forces with Roman Catholic groups to place pressure on the government to reverse this decision. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the New Right also heightened anti-abortion harassment of abortionists – and access to abortion declined substantially by the 1990s.9 In the Republic of Ireland, Roman Catholic pro-life groups were even more effective. Pro-life advocates rallied to create an amendment to prevent abortion, and in 1983 Article 40.3.3, the Eighth Amendment, extended rights to the unborn child. The Republic of Ireland distinguished itself as a pro-life nation.10 As very little research has been conducted in Canada to determine the impact of transnational pro- life movements on Canadian abortion politics, this article explores how those movements informed New Brunswick’s pro-life movement.11

6 Examining the impact of religious beliefs on society and politics is a complex task. Canadian studies indicate that region and religion were central to the New Brunswick abortion debate, but they do not explore why so many citizens were vehemently opposed to abortion. In his study of Canadian religious trends in the 1970s and 1980s, Reginald W. Bibby argued that the “nation’s ‘Bible Belt’ is found not on the Prairies but in the Atlantic region.” His sociological findings suggested that the Maritime Provinces had the highest religious commitment and anti-abortion advocacy in Canada during the 1970s and 1980s due to the significant proportion of conservative Protestants and Roman Catholics, but he did not explore why this manifestation of religious activism occurred.12 An examination of government documents and newspapers demonstrates that members of conservative Protestant churches, such as First United Baptist Church in Moncton, Florenceville United Baptist Church, and Bethany Bible College in Sussex, as well as numerous citizens from the Saint John River valley – a region known for its high percentage of conservative Protestant adherents – opposed abortion. The number of Roman Catholic supporters in New Brunswick was even more significant during this period. In 1981, over half of New Brunswick’s citizens – 371,245 of the province’s 696,403 citizens – were affiliated with the Catholic Church.13 The church’s anti-abortion stance did much to shape pro-life beliefs in New Brunswick. Not only did Pope Paul VI’s condemnation of abortion in the 1968 encyclical Humanae Vitae validate anti-abortion sentiments and influence the formation of transnational grass-roots movements,14 but also Saint John’s Catholic newspaper, The New Freeman, kept citizens informed about global abortion politics and provided a forum for clergymen and pro-life associations to promote pro-life sentiments.15

7 The high percentage of Roman Catholics in the province, however, does not mean that the pro-life movement was a Catholic movement, as not all Catholic citizens unanimously accepted or advocated the pro-life ideology.16 In Michael Cuneo’s study on pro-life activism in Toronto, he indicated that prominent Canadian bishops and Catholic elites interpreted Humanae Vitae as an ideal and they did not universally support or condone the actions of the national and local pro-life movements. 17 It is

8 also important to recognize that many Roman Catholic men and women dissented from the Vatican’s anti-abortion stance and promoted free choice. Through the creation of Catholic pro-choice organizations, such as Catholics for Choice, religious women demonstrated their determination to make reproductive decisions based on the primacy of conscience – the Catholic declaration that encourages individuals to follow their own conscience.18 Therefore, examining anti-abortionists’ religious affiliation will not fully explain their opposition to the procedure.19

9 Transnational studies on anti-abortion activism demonstrate that special purpose groups were central in shaping anti-abortion policies. In Canada, transdenominational coalitions, such as the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada and the Right to Life Association, emerged in the 1960s and 1970s to ensure that public policy reflected what its members viewed as Christian principles.20 Ruth Fletcher’s concept of fundamentalisms emerges from her study of abortion politics in the Republic of Ireland, where she defines fundamentalisms as “political movements which rely on religion to justify their quest to have the absolute authority of their principles recognized.” Fletcher argues that fundamentalisms are different from traditional, conservative, religious movements because they are absolutist in their approach. Fundamentalisms “remove social issues from the human world to the realm of the divine” and insist that everyone is subject to their moral principles. Fundamentalists involved in the abortion debate adopt dominant discourses, such as scientific and human rights discourses, to attract support from religious and secular-minded individuals; they refer to the foetus’s genetic makeup to prove its “membership in humanity” and its right to life.21 While Canadian evangelical Protestants are often referred to as fundamentalists, the concept of “fundamentalisms” and the term “fundamentalists” is used in this article to explore the social and political impact of transdenominational movements.22 An examination of the New Brunswick abortion debate indicates that the pro-life movement was dominated by fundamentalist beliefs.

The politics of choice

10 The debate over a woman’s right to choose if or when she became a mother was a significant issue for the province’s citizens during the 1980s. Abortion rights activists made small gains in the 1970s with the establishment of Planned Parenthood New Brunswick in 1972, and the New Brunswick Advisory Council on the Status of Women in 1977. Both organizations gained government support by focusing on decreasing the need for abortion and maintaining a temperate stance in the debate.23 By 1980, however, the pro-life movement was arguing that PPNB promoted “unrestricted abortions,” and pro-life activists attempted to stop the United Way and the Department of Health from funding the organization. Pro-life aggression towards PPNB caused the organization to put forth a new abortion policy: PPNB would endeavour to decrease the need for abortion through family planning clinics and education, but still maintained that the issue of abortion should be “resolved by the woman, her partner where possible, and her doctor.”24 Throughout the 1980s, PPNB worked with the government to establish family planning clinics in each health region in order to help lower the number of unwanted pregnancies.

11 The New Brunswick abortion debate intensified in June 1982 when the Moncton Hospital stopped performing abortions for six months due to pressure from the pro- life movement. Two-thirds of the province’s abortions were performed at the Moncton Hospital, and the five gynaecologists on that hospital’s TAC were targeted by the pro-life movement. According to the Moncton Times, the pro-life activists “exerted tremendous psychological pressure by calling the physicians murderers and the hospital an abattoir.”25 Dr. Robert Caddick, one of the five gynaecologists, informed a reporter from the Globe and Mail that the moratorium was a result of lobbying from the Right to Life Association and the Moncton Pro-Life Association. The pro-life groups demonstrated in front of the hospital on Mother’s Day, a month before the TAC was disbanded. On 21 June 1982 Dr. Victor McLaughlin, chief of the medical staff, declared that the five gynaecologists would no longer perform abortions at the hospital, despite the reluctance of Caddick to acquiesce in the decision. The executive director of the hospital, William Kilpatrick, informed the press that the hospital would maintain a TAC so that the physicians could refer women to other hospitals. The hospital’s decision caused pro-choice citizens, including Caddick, to consider other options for women in the province. Caddick informed the Globe and Mail that he contacted abortion rights activist Dr. Henry Morgentaler about establishing an abortion clinic in the city.26 In addition, the Committee for the Retention of Abortion Rights was formed promptly after the Moncton Hospital’s decision, and it began collecting signatures to have abortion services reinstated. The reality of the pro-life movement’s influence compelled thousands of New Brunswick citizens to choose a position in the debate.

12 The issue of abortion did not take precedence in the campaigns of the NB ACSW until the physicians ceased performing abortions at the Moncton Hospital. As a government agency founded to promote equality for women, the agency disseminated sexual health information and had remained quiet on the abortion issue.27 When asked the council’s stand on the issue in July 1982, chair Madeleine LeBlanc stated that abortion had not been a “priority issue” until abortion provisions were cancelled.28 In September, the council’s board met and adopted a motion in which the organization’s position was that the “pregnant woman should be the one to make the decision about continuing or interrupting her pregnancy, and THAT government-sponsored services should offer information about all options available to her.”29 In addition, the council decided that the NB ACSW would continue to emphasize the importance of family planning and sexual health education to decrease the need for abortions. The NB ACSW’s sudden involvement in the abortion rights movement propelled the provincial pro-choice movement into the mainstream media and compelled citizens to evaluate the reasoning on both sides of the debate.

13 Throughout the fall of 1982, the Moncton Hospital attempted to gauge the sentiments of Moncton citizens before deciding the future of abortion services at the hospital. In an interview with the Moncton Times, Caddick stated that the hospital needed feedback from other pro-choice groups before determining whether or not abortion services would be reinstated.30 In response to the hospital’s request, coverage of pro-life activism intensified in the media. The Right to Life Association printed a poster in the Moncton Times on 27 November 1982 that featured a picture of a smiling baby and the statement “Here’s One Small Reason Why You Shouldn’t Have an Abortion.”31 Below the image of the baby was a picture of a garbage can filled with aborted foetus’ limbs and the caption “Here are some others.” The poster went on to request that citizens “help us stop this silent Holocaust” by signing a declaration on the poster and mailing them to the Right to Life Association to proclaim their “absolute respect for all human life from the first moment of conception until natural death.” On 22 December 1982 the Right to Life Association published an 18-page proclamation in all five New Brunswick newspapers and three weeklies.32 The proclamation contained 33,000 signatures of citizens who claimed “absolute respect for all human life,” and the Right to Life Association obtained signatures from approximately 119 out of 800 medical doctors. The physicians’ signatures were publicized separately on the first page of the proclamation to demonstrate that a large number of medical professionals opposed abortion.33 Pro- choice activists also organized petitions, and on 10 December 1982 the newspaper revealed that the Committee for the Retention of Abortion Rights had collected 2,000 signatures.34 While the pro-choice campaign was less successful on paper, it is possible that pro-choice activists expressed their views through other means (such as through direct letters to the hospital, telephone calls, or in person).

14 On 28 December 1982 the Moncton Hospital re-established abortion services with the support of four of the five gynaecologists, the hospital medical staff, and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. The staff at the city hospital voted 98 per cent in favour of supporting the gynaecologists’ request to reinstate abortion services. While one gynaecologist remained opposed to performing abortions at the hospital, Caddick indicated in an interview with the Moncton Times that the committee decided to resume abortion services after hearing from citizens who supported a woman’s right to choose an abortion.35

15 Pro-choice activism accelerated in 1982 and 1983 as the NB ACSW became a vocal pro-choice advocate and grass-roots activism took shape through the founding of different pro-choice organizations in Moncton. In addition to numerous citizens speaking out against the pro-life movement through letters to the editor of the Moncton Times, for instance, men and women established a Committee for the Retention of Abortion Rights and a Canadian Abortion Rights Action League chapter in Moncton, and held a protest in front of the New Brunswick Legislature in 1983.36 While the movement appeared to be strengthening, its choice of rhetoric often polarized citizens. For example, the Moncton Times quoted the chair of NB ACSW, Madeleine LeBlanc: “Behind a beautiful name like pro-life, is a fascist movement who wants to impose their own view on the government and the population.”37 Despite her efforts to promote equality for women, LeBlanc’s extreme language created a distrust of pro-choice ideology. Hatfield received letters from women who were alarmed by NB ACSW’s involvement in pro-choice activities and asserted that LeBlanc should remain neutral in the debate if she wished to represent the women of New Brunswick.38 Ironically, the struggles of the pro-choice movement to gain a foothold in the abortion debate increased polarization and caused citizens to question the role of the NB ACSW and consequently the pro-choice stance.

16 While local grass-roots activism was central to the growth of the pro-choice movement, the nature of provincial abortion politics was dramatically affected by Morgentaler’s interest in opening a free-standing abortion clinic in Moncton. Morgentaler had received national attention in the 1970s after he was acquitted by three different juries for operating an illegal abortion clinic in Montreal. During the moratorium on abortions being done at the Moncton Hospital, Dr. Robert Caddick contacted Morgentaler and discussed opening a clinic.39 On 17 September 1982 The Province printed an article entitled “Abortionist plans clinic in Toronto,” stating that Morgentaler “hopes to set up similar clinics in western Canada and in the Maritimes.”40 Morgentaler did not directly contact the New Brunswick government until 25 January 1983, when he sent a letter to the attorney general and suggested that the provincial government prevent unnecessary legal battles by permitting women equal access to legal abortions.41 On 1 June 1983 the attorney general agreed to discuss the matter at the next meeting of the federal and provincial attorneys general. However, he warned Morgentaler that charges would be laid if he opened a clinic in the interim because the government was willing to prosecute him.42

17 On 19 April 1985 the debate intensified when Morgentaler sent letters to Minister of Health Charles G. Gallagher, the Globe and Mail, the Canadian Press, and the Daily Gleaner that declared his interest in opening a free-standing clinic under Medicare in New Brunswick with the assistance of the provincial government. In the letter, Morgentaler explained that a free-standing abortion clinic would be more cost-efficient for taxpayers, would utilize the best equipment and techniques for abortions, would provide counselling services, and would make abortion more accessible for women in the Maritimes. In acknowledgement of the controversial nature of his request, he stated “I know it is customary for politicians to hide behind the conventional wisdom of defending the present law in not allowing any innovations, not even the most useful ones. I, therefore, urge you to take a fresh look at these proposals which would provide improved services within the confines of the present law.” Morgentaler indicated that Minister of Health Charles G. Gallagher could declare a clinic the same as a hospital and set up a TAC at the clinic.43 Through his letter, Morgentaler challenged the provincial government to set aside its biased perspective on his abortion clinics in Quebec, Manitoba, and Ontario and change the situation of abortion access in New Brunswick.

18 In response to Morgentaler’s letter, Hatfield gave a ministerial statement to the legislature on 25 April 1985 in which he rejected Morgentaler’s request to set up free-standing abortion clinics. In his speech, the premier stated that the “government is prepared to take the necessary action to ensure that this policy is upheld and to that end I will be seeking consultation with the New Brunswick Medical Society, the College of Physicians and Surgeons, and the New Brunswick Hospital Association.”44 While acknowledging that the “Criminal Code is no longer an acceptable means to deal with this issue,” Hatfield argued that there was a process to amend the law. Canadian newspapers reported that Hatfield’s statement “won thunderous applause from both sides of the legislature.”45 The government hastily passed legislation to make it illegal for abortions to be performed in clinics. On 27 June 1985 Bill 92 – An Act To Amend An Act Respecting The New Brunswick Medical Society And The College of Physicians And Surgeons of New Brunswick – was passed to prohibit abortions performed outside of hospitals as defined by the Public Hospitals Act.46

19 New Brunswick was not alone in its opposition to abortion clinics; Morgentaler’s request to set up clinics in each province was rejected by all of the provincial governments in 1985. Because the Quebec, Manitoba, and Ontario governments failed – despite numerous attempts – to prevent Morgentaler from establishing abortion clinics in their provinces, the remaining provinces did not welcome discussions about abortion provision with the doctor. The New Brunswick debate, however, deserves attention because it illustrates the cultural, economic, political, and social forces that compelled the Hatfield government to abandon their temperate stance on the issue and pass anti-abortion legislation, and thus provides insight into the extent to which regionalism and religion shaped public policy.

Protecting “tomorrow’s citizens”

20 While pro-choice advocates worked extensively to increase access to abortion services throughout the period, an examination of the correspondence between pro- life advocates and government officials indicates that the pro-life movement was much more effective in promoting its agenda. The New Brunswick pro-life movement was predominately influenced by the New Brunswick Right to Life Association, which was established in Sussex in 1973 and, to a lesser degree, Moncton Pro-Life, a Dalhousie Alliance for Life chapter, and Association Pro-Vie de la Péninsule Acadienne.47 As the Right to Life Association gained the support of at least 33,000 citizens through its campaign to stop abortions performed at the Moncton Hospital, the pro-life movement continued to lobby the government and medical professionals by voicing its opposition to abortion through letters to the Hatfield government and newspapers, holding protests outside hospitals, and hosting pro-life conferences (such as the Alliance for Life national conference in Moncton from 30 June-3 July 1983). While the Moncton Hospital’s decision to reinstate abortion services in December 1982 was a setback for pro-life activists, it did not discourage them and merely confirmed their belief that they needed to fight for the termination of abortion services.48

21 Furthermore, Morgentaler’s announcement on 17 September 1982 that he would be opening free-standing abortion clinics across Canada contributed to a major letter-writing campaign that demonstrated the intense anti-abortion sentiments in the province. Morgentaler’s declaration that he would open clinics in the Maritimes was perceived as a threat to the pro-life movement and New Brunswick citizens. Pro-life activists appealed to Hatfield to protect New Brunswick’s “unborn citizens” from Canada’s “archabortionist.”49 Throughout the fall of 1982 New Brunswick citizens, including the Grand Knight of the Knights of Columbus in Campbellton and the Riverside Council of the Catholic Women’s League of Canada, sent letters to the government informing the premier of his obligation to protect the lives of the “unborn.”50 Hatfield assured citizens that “the Department of Health has received no request from Dr. Morgentaler for opening of abortion clinics and certainly has no intention of approving such clinics.”51

22 Despite the assurances from the premier, concern about “unborn” citizens and the arrival of Morgentaler persisted throughout the province due to events in Winnipeg and Toronto. On 5 May 1983 Morgentaler opened a clinic in Winnipeg and on 15 June 1983 a clinic was opened in Toronto. Even though the clinics were raided immediately, equipment was impounded, and new criminal charges were laid against Morgentaler and his staff, the events created anxiety amongst pro-life members in New Brunswick.52 New Brunswick citizens dedicated to these pro-life sentiments continued to pressure Hatfield and his government to refuse Morgentaler access to the province and to stop abortions that did not threaten the life of the mother.53 When Morgentaler approached the provincial government in April 1985 and requested assistance in setting up free-standing abortion clinics, Hatfield swiftly put in place measures that would block Morgentaler from effectively operating a clinic. The Hatfield government’s decision to pass Bill 92 in June was an unmistakable victory for the pro-life movement, and the government’s firm stand against Morgentaler and abortion clinics caused numerous citizens to send letters thanking the premier for opposing “abortion-on-demand.”54

23 The strength of pro-life ideology may best be understood through the lens of fundamentalisms. Pro-life activists’ absolute conviction that abortion was evil and morally wrong was based on their belief that life begins at conception. And to attract the attention of both secular and religious-minded citizens, New Brunswick pro-life advocates used a human rights discourse to highlight the inhumane nature of abortion. The majority of the activists used human rights terminology to depict abortions, such as killing a “child in the womb,” a “helpless infant,” and “unborn babies.”55 Other activists, such as a group of women from St. Stephen, argued that “the right to life is one of our basic freedoms which no individual has the right to deny another.”56 The Grand Knight of the Knights of Columbus in Campbellton feared that Morgentaler would “violat[sic] the civil right to life of the child in the womb, the elderly or the handicapped.”57 The belief that the pro-choice movement had no respect for life was a consistent theme throughout the pro-life letters.

24 Because the Canadian constitution did not extend rights to the foetus, Canadian pro-life activists also adopted a scientific discourse to help condemn abortion – in large part because the rise of reproductive technologies, particularly ultrasound imaging, had validated the role of science in reproductive matters and transformed transnational pro-life rhetoric.58 In 1984 Dr. Bernard Nathanson and the American Right to Life Committee produced the pro-life film The Silent Scream, which showed an abortion being performed via ultrasound at twelve weeks gestation; it also depicted the “child” in its “sanctuary” and argued that one can see the “child’s mouth open in a silent scream.”59 The film greatly altered people’s perspective on abortion and intensified pro-life activism across North America. As the film was directed, filmed, and narrated by Dr. Nathanson, it had an “aura of medical authority.”60 The use of scientific rhetoric and technology reinforced the pro-life movement’s claims that the foetus’s survival should be valued more than a woman’s right to choose. Fetal imaging technologies created the possibility for foetuses to gain rights and a perceived independence from women’s bodies that outweighed women’s rights.61

25 The involvement of the medical profession and scientific technology in the pro- life movement reinforced citizens’ beliefs that life began at conception. In an extreme use of the scientific discourse, an unnamed New Brunswick citizen wrote a letter to the government containing an abortion monologue to prove that abortions performed between the seventh and twelfth weeks of pregnancy were barbaric:

Dear Mommy, It is so nice and warm in here. You keep me safe and you nourish me. I already love you so much. I even know your voice. Someday I want to grow up to be just like you, mommy. . . . Ahh! My tummy; a knife is cutting it. Oh no! my leg and my other foot. The blood is gushing in my face. This pain! What are they doing to me? It hurts so bad . . . (here the tiny body is scraped into the hospital garbage can). . . . I’m sorry mommy if I did anything bad! I promise I won’t do it again. Please don’t leave me like this mommy, I need you! I’m so scared and I hurt so bad! Don’t go mommy, I want to live!!!!!

Following the monologue, the female writer informed the government that she had considered “this act of human butchery” but that she changed her mind and now had a five-year-old daughter.62 Both The Silent Scream and the unnamed New Brunswick citizen used the scientific discourse to “prove” that life begins at conception, and they suggested that the foetus was capable of speech but that it was silenced within the womb. The scientific discourse blurred the boundary between conception and life, enabling pro-life activists to view the foetus as an “unborn child.”

26 While the government records do not demonstrate that the medical community universally opposed abortion, many members of the New Brunswick medical community promoted this scientific discourse throughout the 1980s and were successful in using it to limit a woman’s ability to obtain an abortion. This is evidence of their absolutisms; once the moratorium had ended at the Moncton Hospital, for instance, Dr. R.H.B. from Campbellton informed the Times-Transcript of his hope “that Moncton would become the springboard for a roll-back against the movement of abortion in Canada” and that “I for one, as a physician whose professional goal it is to preserve life, cannot reconcile this departure from Hippocratic standards. Further, as a Christian, whose unconditional respect for life is essential to my faith, I must virtually weep over the present state of the art.” Dr. R.H.B. thus expressed a fundamentalist perspective on abortion by arguing that doctors who performed abortions overlooked “Hippocratic standards” while those who stood against abortion demonstrated an “unconditional respect for life.”63 Other New Brunswick physicians also spoke out against abortion after Morgentaler requested to establish an abortion clinic, and drew on fundamentalist abortion ideology to support their anti-abortion position. Twenty-five male physicians, for example, signed a petition stating that “to attempt to meet the problem of unwanted pregnancy by the taking of unborn life is a misguided and destructive act against humanity, itself. Therefore, it is an act against women as well as against men. It is our wish to see the practice of abortion in Canada stopped.”64 Seven of the doctors were from Dalhousie, one of the regions in which there were no abortion services available.

27 The strong push by some doctors to stop abortions in the province forced some doctors to approach the government and voice their dissatisfaction with the inaccessibility of abortion services. In 1986, a physician from St. Stephen wrote a letter to the Department of Health and Community Services to complain about one of her patients being denied a late-term abortion (20 weeks) at the Moncton Hospital because St. Stephen was “not in the Moncton Hospital’s geographic area.”65 The doctor referred her patient to see an obstetrician at the Saint John Regional Hospital, where she was informed that the Saint John Regional Hospital could not perform a saline termination (but that they were able to perform a hysterotomy). The patient declined the hysterotomy due to her poor health and the risks involved with having major abdominal surgery, and she opted to travel to the Moncton Hospital for a saline termination.66 When the St. Stephen doctor was informed by the Moncton Hospital that it was unlikely the TAC would grant approval of the application, she threatened to go public with their decision and within an hour of the phone call the application was accepted. The deputy minister responded on 24 January 1986, and informed the doctor that there was no easy solution as “the number of hospitals with Therapeutic Abortion Committees in New Brunswick is a bit limited [and] no one can force a hospital to set up such a committee.” The case brought before the deputy minister was not a case of “abortion-on-demand”; the 37-year-old patient’s “amniocentesis report revealed the presence of a trisomy 13 fetus as well as an elevated alphafetoprotein level.” The laboratory testing of alpha-fetoprotein levels and the detection of Trisomy 13 became common in the 1980s due to technological advances, and they helped determine if a foetus would likely have mental and physical disabilities and a short life span. The St. Stephen physician argued that the health of the mother and the care of her 14-year-old child were more important than the foetus.67 While the lack of doctors willing to establish TACs indicates fundamentalisms within the medical community, it is also possible that doctors did not perform abortions in fear of compromising their professional positions and being ostracized by the medical community.

28 The role of absolutisms in abortion politics is perhaps best demonstrated by activists’ opposition to abortion in instances of rape and incest. Activists insisted that adoption was the only acceptable alternative for unwanted children.68 On 30 July 1982 a piece by Peter G. Ryan of the Right to Life Association appeared in the “Public Opinion” column of The Moncton Transcript; it argued, erroneously, that “rape pregnancy is extremely rare (it appears that rapists tend to have an unusually high incidence of sterility also that there commonly is a psychosomatic reaction in the rape victim’s body that renders her temporarily infertile).” He also insisted

when it does occur this is a prime example of when family and community should pull all stops in proffering an abundance of moral and economic support to enable the mother to cope at least until the baby is born. If the mother feels unable to care for the child after birth, he/she may be placed with one of the many couples you mention who are “desperate to have a child and eager to adopt”; more than 700 such couples are presently registered with the Department of Social Services.69

The Right to Life Association indicated, in other words, that the needs of citizens who were unable to reproduce were more important than the emotional turmoil a woman might experience from carrying a rape pregnancy to term. Numerous citizens supported the association’s viewpoint on rape and informed the government that abortion was a selfish and unnecessary act.70

29 Examining the language used by New Brunswick pro-life activists also indicates that fundamentalisms were central to activists’ perception of Morgentaler. They considered abortion to be murder, and commonly associated abortion with the Holocaust. Despite Morgentaler being a victim of the Holocaust himself, pro-life activists considered him akin to Adolf Hitler and the Nazis – a tendency that intensified with Morgentaler’s decision to open clinics nationwide. During 1982, for instance, citizens referred to Morgentaler’s abortion clinics as “illegal killing chambers,” comparing abortion clinics to the gas chambers in the Nazi concentration camps.71 In 1986, a Moncton citizen argued that “the photographs of the Jewish hollocoust [sic] during the war Sir which we have seen over and over again do not look any different than the hollocoust [sic] of our own unborn citizens, the only difference Sir, is the size of the victims.”72 While only a small percentage of the letters linked abortion with the Holocaust, pro-life activists unanimously considered abortion murder and Morgentaler, by extension, a murderer. Morgentaler was frequently referred to as a “mass murderer,” a “paid killer,” and a “cruel monster.”73 In a letter congratulating Hatfield for refusing Morgentaler’s service in the province, a clergyman of the Bayview Pentecostal Church in Bathurst also warned that the nation was under a “Satanic attack” and Hatfield was responsible for guiding the province away from the wicked ways.74 The language used by pro-life activists indicates that Morgentaler’s abortion clinics not only represented a threat to “tomorrow’s citizens” of New Brunswick, but they also foreshadowed the potential deterioration of society as a whole.75

30 While religious beliefs spurred grass-roots activism, a significant percentage of New Brunswick citizens were against accessible abortion services because they feared that a decline in the fertility rate and the use of tax dollars for abortion clinics would weaken the Atlantic Canadian economy even further. Throughout 1981, The Campbellton Graphic stated, the “two-headed monster of inflation and unemployment” devastated the economic system and the Hatfield government was faced with an economic recession.76 New Brunswick’s lumber industry suffered severely due to the decline in exports to the United States, and by 1985 New Brunswick’s unemployment rate was 14.8 per cent whereas the national rate was 11 per cent. The Hatfield government was re-elected for the fourth time during the recession, and the government was not able to deliver the programs that were promised during the election campaign.77 Furthermore, funding cuts within hospitals and schools caused employees to fear for their employment security.78 Middle-class citizens also lost their homes and/or savings due to increasing interest rates.79

31 Pro-life activists responded to the recession by promoting adoption and reproduction as a means to boost the economy.80 Pro-life organizations nationwide contacted each provincial government, insisting that the loss of “unborn babies” was connected to the weakening national economy.81 In 1987, a petition sent to the New Brunswick government from pro-life advocate F.E.R. and others in Salmon Arm, British Columbia, requested that all provincial governments stop performing abortions because “we are very short of babies. When a country is short of babies, first nurses are put out of work, then teachers and all people in all walks of life suffer with bad economy.”82 The petition also stated “lots of babies mean lots of needs; lots of needs mean lots of jobs!” By no longer funding abortions nationwide, Canada would “start to hum like a healthy beehive coming to life in the springtime.” At the same time, others were more concerned about their tax dollars being used to establish abortion clinics.83 And numerous letters sent to the government stated that Premier Hatfield would not be re-elected if he chose to support “abortion-on- demand” and use taxpayers’ dollars to fund abortion services.84 Moreover, the recession itself caused New Brunswick citizens to be more concerned about how their tax dollars were spent and, as a result, provincially funded abortions and family planning clinics were increasingly scrutinized by civil servants.85

Anti-abortion bill and the decline in abortion services

32 While the declining economy certainly influenced the government’s opposition to abortion clinics, an examination of correspondence between civil servants demonstrates that the Hatfield government was against abortion at a deeper level. After delivering the ministerial statement in the legislature on 25 April 1985, in which the government declared its opposition to abortion clinics, Hatfield stated that the government would consult with the New Brunswick Medical Society, the College of Physicians and Surgeons, and the New Brunswick Hospital Association.86 Over the next two months, the minister of justice and the minister of health worked with the medical community to draft an act that would prevent Morgentaler from performing abortions in the province.

33 While Minister of Health Charles Gallagher informed reporters in June 1985 that the government passed Bill 92 at the request of the medical community, inter-office memos indicate that the government drafted numerous proposals to prohibit abortions in non-hospital locations weeks before meeting with the College of Physicians and Surgeons.87 On 30 June 1985 the deputy minister of justice informed the attorney general that, in regards to criminal prosecution, the police could arrest Morgentaler if he performed an abortion in the province without the approvals laid out under the Criminal Code of Canada and the provincial Public Hospitals Act. Morgentaler could also be convicted for failing to comply with section eight of the Public Hospitals Act, which forbade physicians from “operating an unapproved hospital.” The penalties could include a $1,000 fine for each abortion performed and the suspension of the physician’s medical license. In addition, the deputy minister of justice indicated that the “issuance of an injunction is the most effective remedy as a violation of its terms would likely result in imprisonment.” To ensure prosecutions for violating the Public Hospitals Act were successful in court, the deputy minister of justice suggested an amendment of section eight to clarify and strengthen the definition of hospital. Instead of focusing on the issue of abortion, the government would argue that the issue was “one of hospital approval and standards of medical practice.”88

34 Despite the government’s public assertions that it was not against abortion, inter- office memos drafted in May 1985 demonstrate that it intended to take an anti- abortion stance.89 On 10 May 1985 a proposal entitled “Abortions in Non-Hospital Locations” was submitted by the deputy minister of justice and the deputy minister of health and community services to Hatfield; it outlined potential options for New Brunswick abortion prohibitions. The proposal suggested that there were several advantages and disadvantages involved with prohibiting abortions in non-hospital locations under the Public Hospitals Act, R.S.N.B. 1973 and the Medical Act, S.N.B. 1981. If the government decided to prohibit abortions “except in hospitals approved under the [Public Hospitals] Act,” the advantages would be twofold: a trial would be held before a judge instead of a jury and the prohibition would not breach the Charter of Rights. However, the civil servants acknowledged that the “prohibition would probably be found unconstitutional if challenged.” The second proposed option was to amend the Public Hospitals Act to state that “abortions are identified as one of a number of high risk procedures not to be performed in non-hospital settings.” In addition to the advantages listed in the first option, the amendment “masks the fact that section is really anti-abortion.” There were numerous disadvantages listed, such as the prohibition could be found unconstitutional, the procedure might not be high risk, and they feared an increase in facility costs. While the government was eager to conceal its anti-abortion stance, officials warned the premier that prohibiting abortions under the Public Hospitals Act would most likely result in Morgentaler defeating the government in court.90

35 The government concluded that the prohibition of abortions performed in non- hospital settings could be considered constitutional under the Medical Act if they received the support of the College of Physicians and Surgeons. The act would “deem the performance of abortion outside a hospital as being ‘professional misconduct’.” The only disadvantage noted was that the prohibition “invades jurisdiction previously granted to College of Physicians surgeons [sic].” The deputy minister of health and community services suggested the premier meet with officials from the College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Department of Health, and Department of Justice to “resolve ‘a valid concern’ as it is the subject of criminal law.”91 On 15 May 1985 the government requested the college’s support in amending the Medical Act (1981) to prohibit abortions in non-hospital settings as defined by the Public Hospitals Act and to temporarily suspend members as “unfit to practice or incapacitated” because they performed such abortions. The college agreed to amend the act after a council meeting in June, and the new act was passed by the end of the month.92 The minister of health’s statement in The Times-Transcript, therefore, that “on May 15, a request for the enactment of legislation was received from the Medical Council of the Society” demonstrates the government’s unwillingness to take a public stand in the abortion debate.93 By suggesting that the bill was passed at the request of the medical community, the government was able to mask its opposition to abortion.94

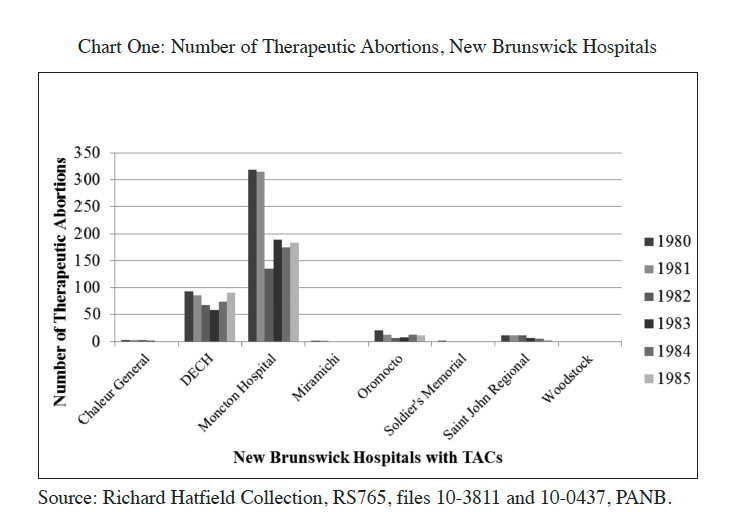

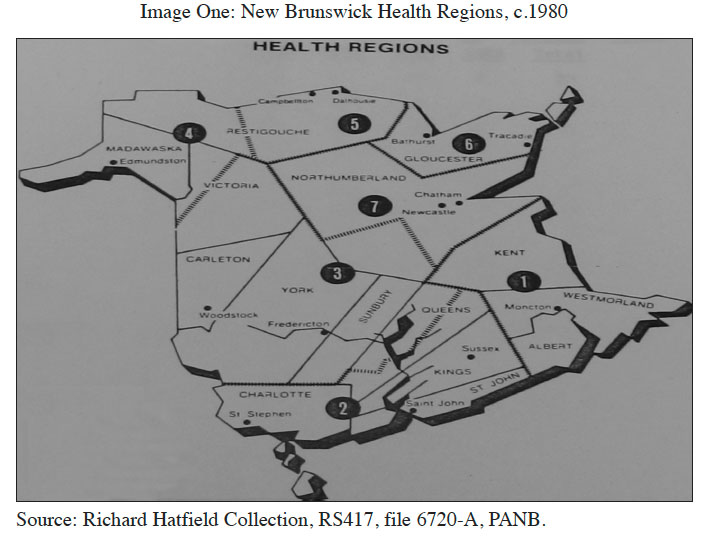

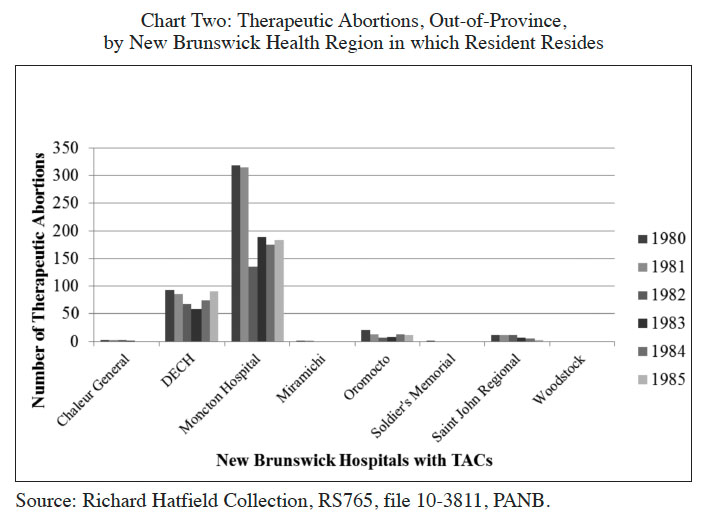

36 While there are many discrepancies in the abortion statistics in New Brunswick that were compiled by Medicare and Statistics Canada throughout the 1980s, the numbers indicate that abortion provision decreased substantially after the moratorium at the Moncton Hospital.95 In 1980, seven of New Brunswick’s thirty-four general hospitals had TACs and all seven performed abortions. In 1982, only five of the seven hospitals were performing abortions and, by 1984, Chaleur Hospital in Bathurst had stopped performing abortions and the Soldier’s Memorial Hospital in Campbellton had abolished its TAC. Between 1984 and 1987, New Brunswick women could obtain abortions at the Dr. Everett Chalmers Hospital (DECH) in Fredericton, the Moncton Hospital, the Oromocto Hospital, and the Saint John Regional Hospital. According to statistics compiled before Bill 92 was passed, there were 449 abortions performed in New Brunswick in 1980, 430 in 1981, 223 in 1982, 263 in 1983, and 267 in 1984. The Moncton Hospital, which performed two- thirds of all abortions in the province, performed fewer abortions after the moratorium (Chart One).96 In an inter-office memo sent on 22 March 1984, a civil servant from the Department of Health stated that 20.6 per cent of the women who received abortions out-of-province in 1983 were from health regions 4, 5, and 6 – the northern New Brunswick regions (Image One).97 Despite the decline in abortion services provided by New Brunswick hospitals, the government funded fewer out- of-province abortions throughout the 1980s (Chart Two).98 Determining the actual number of out-of-province abortions is challenging, as the out-of-province statistics do not account for abortions performed in illegal abortion clinics or unreported abortions performed outside Canada.

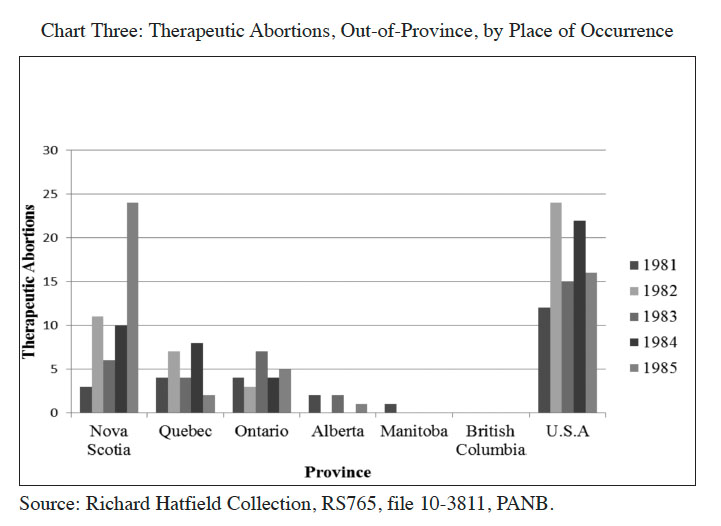

37 While statistics collected post-1985 identified significant discrepancies in the number of abortions performed in and out-of-province between 1980 and 1987, an important discovery by Planning and Evaluation was that health regions 1, 2, and 3 – the southern New Brunswick regions in which all therapeutic abortions were performed – had the most out-of-province abortions between 1980 and 1985.99 Out-of-province abortions that were paid by Medicare most often occurred in the United States and Nova Scotia (Chart Three).100 New Brunswick hospitals received approximately 252 applications for terminating pregnancies in 1982, 354 in 1983, 350 in 1984, and 330 in 1985 (Chart Four). While individual hospitals were not required to document the number of rejected applications, Planning and Evaluation Hospital Services succeeded in finding documents that indicated at least 299 women were denied therapeutic abortions between 1982 and 1986.101 In February 1988 the newly elected Liberal government conducted a preliminary report on the abortion issue and discovered that the majority of those women were single and between 15 and 24 years old. The report also indicated that the family planning clinics were not as effective as the government hoped since women continued to apply for abortion services.102

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2 Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 338 The decline in accessible abortion services after the moratorium signalled changing perceptions of a woman’s right to control her body and the government’s desire to maintain the status quo. The Moncton Hospital debate, which reporters described as a “microcosm” of the national debate, demonstrated that pro-life activists were capable of shaping public policy. While the hospital reinstated abortion services in 1983, there were significantly fewer abortions performed between 1983 and 1987. 103 The statistics demonstrate that the government’s opposition to Morgentaler and the strength of anti-abortion activism outweighed women’s needs for accessible abortion services.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5Conclusion

39 It may seem that the abortion debate in New Brunswick was no different from the debates that occurred throughout Canada during this period. However, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island continue to have the most restrictive abortion services in the country. The Hatfield government remained opposed to the pro- choice movement until defeated in October 1987 by Frank McKenna and the Liberal Party of New Brunswick, and the McKenna government upheld Bill 92 following the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision to decriminalize abortion in R. v. Morgentaler. In 1994, Morgentaler defied Bill 92 and opened an abortion clinic in Fredericton, New Brunswick. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of New Brunswick revoked Morgentaler’s license, prohibiting him from practicing medicine in the province. On 14 September 1994 the Court of Queen’s Bench of New Brunswick struck down Bill 92 in Morgentaler v. New Brunswick and declared the law unconstitutional. While the Fredericton abortion clinic remained legal, the province refused to fund abortions performed outside hospitals. Morgentaler launched a lawsuit against the New Brunswick government in October 2002 for refusing to fund abortions at his clinic. That lawsuit is ongoing.104

40 Examining the period during which the abortion debate developed in New Brunswick – 1980-1987 – is essential to understanding the political and social struggles that arose after the decriminalization of abortion in 1988 as it helps identify the emergence of the politically and socially effective pro-life movement and the struggles of the pro-choice movement to gain a foothold in the region. The pro-choice movement presented a feminist ideology that gained relatively little support from New Brunswick citizens. Pro-life activism increased substantially throughout the 1980s due to the strength of fundamentalisms in the pro-life ideology evident among many New Brunswickers. The pervasiveness of pro-life absolutisms – including the protection of the elderly, infirmed, and disabled from euthanasia – compelled citizens to become involved in the pro-life movement. However, abortion remained the central concern within the movement because it was legal. The Hatfield government’s decision to pass the anti-abortion law Bill 92, therefore, was a victory for the pro-life movement. Examining the societal and governmental responses to abortion during the 1980s suggests that abortion continues to be a contentious issue in 2012 because New Brunswick citizens have long been polarized by differing beliefs on religion, human rights, and sexuality.

41 While this article sheds light on various social and political factors that shaped the New Brunswick abortion debate, there are many avenues that remain unexplored. A deeper analysis of the medical community’s position on abortion, from the perspective of hospital committees, nurses, doctors, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of New Brunswick, and the Medical Society of New Brunswick would provide much-needed insight into the complex nature of the role of health professionals within the abortion debate.105 Moreover, the religious roots of Canadian pro-life activism remain under-investigated. And comparative analyses of abortion debates within Canada would demonstrate the extent to which national and transnational cultural discourses shaped anti-abortion activism.106