Articles

Development and Degradation:

The Emergence and Collapse of the Lobster Fishery on Newfoundland’s West Coast, 1856-1924

Même si la pêche à la morue a souvent été au cœur des nombreuses études sur les changements socio-écologiques survenus à Terre-Neuve au cours des 20 dernières années, d’autres espèces et industries ont joué un rôle significatif dans l’histoire de l’île. Cet article s’intéresse à la pêche au homard sur la côte ouest de l’île. Il fait valoir principalement que si les changements dans l’industrie de la pêche à la morue étaient importants pour la pêche au homard dans cette région de l’île, l’industrie était étroitement façonnée par la nature des homards eux-mêmes, l’évolution de la situation écologique locale et régionale et la nature changeante de l’économie régionale du nord-est de l’Amérique du Nord.

Although the cod fishery has most often been central to the many studies of socio- ecological change in Newfoundland during the past 20 years, other species and industries were also significant to the island’s past. This article examines the lobster fishery on the island’s west coast. Its main argument is that while changes in the cod fishery were important for the lobster fishery in this part of the island, the industry was intimately linked with and shaped by the nature of lobsters themselves, by alterations in local and regional ecological circumstances, and by the changing nature of a northeastern North American regional economy.

1 OVER THE PAST 20 YEARS, STUDIES OF SOCIO-ECOLOGICAL CHANGE in Newfoundland have proliferated.1 Such works reflect a confluence of researchers’ theoretical interests with circumstances in Newfoundland itself.2 The collapse of northern cod stocks impelled the federal government to close the fishery in 1992, thereby ending a 500-year-old industry and throwing approximately 40,000 people out of work.3 These dramatic events illustrated the connections between ecological and social change, and highlighted the importance of cod in those processes in Newfoundland. The resultant studies have been both necessary and fruitful, for it is difficult to understand broader processes of socio-ecological change in Newfoundland without attention to the fortunes of this fish. Localized depletions of particular year classes of the species in the 19th century, for example, provoked both a spatial expansion of the fishery and the implementation of new, more intensive gear that not only caused political controversy, but also had important social and political consequences as men and women ventured farther from home to catch fish.4 Declining prospects in the staple trade also led to the exploitation of other marine species such as seals and to the development of minerals, timber, and other landward resources.5

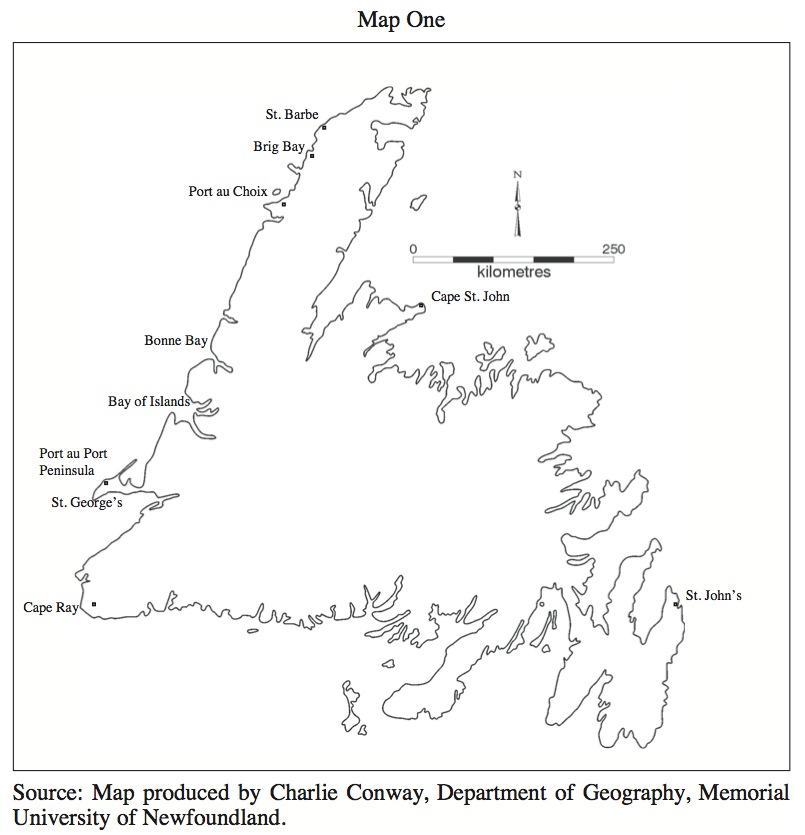

2 While historians have provided important insights into the timing, rationale, international linkages, and labour relations within some of these industries, many still remain largely unexplored. This article contributes to our understanding of socio- ecological change in Newfoundland by considering historical aspects of one such industry: the west coast lobster fishery. It considers the fishery on this coast for two main reasons. The first has to do with ecology. The west coast has some of Newfoundland’s choicest lobster grounds, and it was the site of one of the earliest commercial lobster fisheries on the island. The second is linked to sources. From the time of first European contact onward, Newfoundland, like a large number of other colonies, was caught up within the conflicts and subject to the diplomatic arrangements among competing imperial powers. The French and the British were particularly significant for Newfoundland. While the French recognized British sovereignty over the island in the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, they also secured rights to fish and to dry their catch on portions of the coast. As of 1783, the “French Shore” began at Cape St. John on the island’s northeast coast and included the eastern and western sides of the Great Northern Peninsula and the entire west coast of the island down to Cape Ray (see Map 1).6 Newfoundlanders and other British subjects were not permitted to erect structures inhibiting, or otherwise interfering with, the French fishery along this stretch of coast. The agreement originally seems to have been satisfactory to all concerned. By the mid-19th century, however, a series of rebellions dovetailed with a global economic crisis to produce new approaches among imperial officials. Increasingly, these men promoted the expansion of the “settlement of British peoples in colonial spaces” as a means of lowering the costs of administration while also securing tracts of overseas territory.7 Such approaches fuelled the nationalist project of imperial expansion in Newfoundland and elsewhere, and for many Newfoundland politicians and merchants the fact that a foreign power had claims to a piece of the territory they now imagined as part of their dominion led to turmoil amongst them, the French, and the British.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 13 This strife is a boon for historians for two reasons. First, the overlapping claims on the treaty coast meant that the region lay outside of the Newfoundland government’s jurisdiction until after the French relinquished rights to it as part of the 1904 Entente Cordiale. While canners on the shore were not subject to the colonial government’s regulations, they were required to give an accurate record of the products of their industry. Moreover, the potential for conflict led the British to send out regular naval patrols to survey conditions on the coast while also conducting various investigations into the “French Shore question.” The source materials for the treaty coast, then, include detailed information about the spread of the commercial lobster fishery on the coast, the output of particular factories, and the changing patterns of work. They also include interviews with fishermen, merchants, clergymen, and justices of the peace. While the surviving evidence is uneven, it provides a more detailed record of changing conditions in the region and in this fishery than do census returns and other materials available for other parts of the island.8

4 A careful examination of these materials suggests that the lobster fishery was in some ways tied to, and shaped by, the changing nature of the cod fishery. It also indicates, however, that the biological nature of lobsters themselves, as well as the particular conditions under which the lobster fishery in northeastern North America developed, gave the fishery in Newfoundland its own distinct logic and history. The founders of the earliest commercial lobster fishery were neither interested in the cod fishery nor from Newfoundland. Instead, the origins of this trade in Newfoundland were linked with developments further down the eastern seaboard. Partly drawn by the prospect of expanding in a lucrative trade and partly pushed north as stocks of lobster declined off their own coasts, investors in the lobster industry from Maine and the Maritimes pioneered the Newfoundland fishery. The subsequent expansion of the trade, and the ways conflicts surrounding it unfolded, reflected the reality that a wide range of distinct social, political, and ecological circumstances (many of which were far removed from late-19th-century Newfoundland temporally and spatially) combined in unexpected ways to shape the history of this industry. The salmon and herring fisheries, for example, had long been important to residents and traders of Newfoundland’s west coast. Like the lobster fishery, those fisheries emerged in Newfoundland partly in response to overexploitation elsewhere in North America and in Europe. And while the late-19th-century decline in the shore cod fishery had been important in the west just as it was in the east, the simultaneous depletion of herring and salmon stocks created a critical situation for working people and merchants. For both groups, lobster became an industry of last resort and, in the years after 1880, Newfoundlanders witnessed a flood of investment and of labour into this trade. Despite efforts to save the industry, though, by the early decades of the 20th century harvesters depleted stocks to such a degree that the Newfoundland government imposed a moratorium on the fishery.

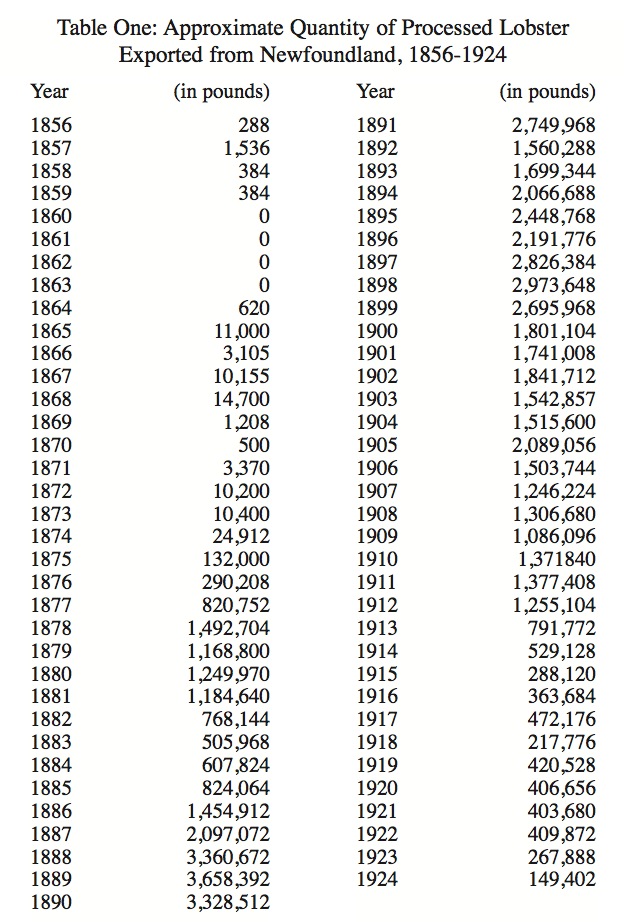

5 It is likely that lobsters contributed to the diet of European sojourners and settlers in Newfoundland, as elsewhere along the eastern seaboard, from an early date.9 There is, however, no record of a commercial trade in the crustaceans before 1856. In that year, customs returns indicate that six cases left the island and, after that time, there was a consistent, if uneven, trade up until the early 1870s when a more regular fishery began (see Table One).10 The advent of a commercial lobster fishery in Newfoundland, the timing of the shift from an irregular and relatively small-scale industry to a permanent and intensive one, and the conduct of the fishery itself reflected earlier developments within the lobster fishery elsewhere on the Atlantic seaboard. The earliest commercial fishery for lobster in North America emerged in New England in the late 18th century, and the nature of lobsters themselves shaped the way it arose and changed over time. Early in the history of the fishery the most important determinant of spatial orientation and technological innovation was the delicate nature of lobsters once removed from the water. Unless they are kept cool and hydrated, lobster do not live long out of water and, after they die, they decompose quickly. The earliest fishery, then, was a live trade in which fishermen supplied the growing urban populations of such cities as Boston and New York.11 As lobster stocks adjacent to such centres thinned, local men of capital sought out new ways of accessing stocks further afield. Their initial strategy was to outfit small schooners with circulating seawater holding tanks in which lobsters could be stored live. 12 These vessels, known as “smacks” or “well smacks,” sailed along the New England coast collecting live lobster throughout the first half of the 19th century.13

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 16 This arrangement worked well for a regionally oriented fishery. Some of the most important emerging markets for lobster (and for other inexpensive sources of protein) in the mid-to-late-nineteenth century, however, were in Brazil, the British West Indies, and in growing urban-industrial centres in Britain, France, and Germany. The desire to sell to these distant markets soon led New England capitalists interested in the lobster trade to adopt new technologies. 14 In particular, they took an interest in the work several European inventors-cum-businessmen conducted into preserving food by hermetically sealing it in glass or metal vessels.15 William Underwood, a native of New Orleans, along with Ezra Daggett, Charles Mitchell, and Thomas Kensett, all of whom apprenticed in Britain, operated some of the earliest canning businesses in the United States.16 By 1836, Underwood was preserving not only lobsters but also fruits, jams, jellies, and sauces in bottles.17 One of the chief problems these men faced in their early operations was acquiring a sufficient quantity of glass bottles, as Britain was the main source of these containers. Taking the lead from his counterparts in England, in the late 1830s Underwood began experimenting with metal canisters – a method he perfected by the 1840s.18

7 In catching, immediately cooking, and canning the crustaceans, it was possible to avoid spoilage and thus to access a far wider network of markets. The benefits of preserving lobster in this way did not escape those interested in the trade. Throughout the 1830s a growing number of canners in northeastern North America began adding lobsters to the list of products they preserved, while after 1840 an increasing number of individuals began to focus exclusively on the crustaceans. Charles Mitchell, a Scot who had worked in salmon canning near Aberdeen, for example, arrived in Nova Scotia in 1840. Soon thereafter he entered into partnership with a Mr. McPherson and established a lobster factory in Liverpool, Nova Scotia (one of the earliest on the eastern seaboard).19 The real nucleus of the early trade, however, was in New England. Underwood himself had long realized that there was money to be made in seafood, including lobster, and he soon focused on these crustaceans and on cod and haddock.20 He built his first factory focused exclusively on lobster at Harpswell, Maine, in 1844. And while he may have been a pioneer in industrial food preservation in the United States, Underwood did not maintain a monopoly on his methods. Often employees of an established firm, on learning the “secrets of the trade,” went into business for themselves. The bulk of new entrants received their training in New England establishments. Men such as Winslow Jones and Samuel Rummery exemplify this tendency well. Both men began working for Underwood and later went on to head up their own substantial canning operations. Jones eventually played a leading role in W.K. Lewis and Brothers, while Rummery headed up Rummery and Burnham (later Burnham and Morrill Comany).21

8 Though they varied in size, most of these early factories employed at least 15 to 20, and sometimes more than 40, hands. Not long after such factories began operating, managers “rationalized” work into a series of specialized tasks. In the larger factories there were workers who specialized in boiling the animals, others who only cracked the shells, and still others who specialized in picking meat from one or another section of the lobster (for example, there were both tail pickers and arm pickers). Other tasks included making tins, painting, washing, covering, weighing, sealing, and wiping cans as well as labeling and packing cans into crates. As Richard Rathburn, a government official who visited many of the factories noted, these factories employed both men and women, and work was highly gendered. Men performed heavier work (such as cracking and breaking) and “skilled work” like soldering and sealing, and women occupied themselves with “unskilled” tasks like extracting meat and washing, filling, and weighing cans.22 Predictably, women received approximately half of the wages men received. While at smaller factories one person sometimes performed more than one task, this specialization within the labour process was entrenched soon after the canneries began, and the job titles Rathburn noted reflected this fact. In addition to superintendents and foreman, at most factories there were boilers, bath men, crackers, breakers, sealers, tail shellers, arm pickers, weighers, coverers, and cleaners.23

9 While the nucleus of the early lobster fishery may have been in New England, soon the number of large-scale enterprises in the Maritimes and Quebec increased as well.24 There were two main reasons for the expansion of the industry into these areas throughout the latter half of the 19th century. First, it could be a highly lucrative industry, and this profitability during the early years encouraged established canners to expand into new territories. William Underwood and Company, for example, was one of the earliest canners operating on the Bay of Fundy in New Brunswick, W.K. Lewis and Brothers built some of the earlier factories near Halifax, and Burnham and Morill established early canneries in Halifax and Guysborough counties before branching out into Cape Breton and the Northumberland Strait.25 Maine packer Winslow Jones established factories in New Brunswick, Quebec (including the Magdalen Islands), and Nova Scotia, while members of his family, having learned the trade from him, headed off to pioneer the salmon canning industry on the Pacific Coast.26 Similarly, while it is not clear where he learned the trade, A.C. White, a native of Haverill, Massachusetts, partnered with a tin smith named Whidden of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. While White’s first forays into the industry were disappointing, he went on to success in Port Mouton. And similar to W.K. Lewis and Samuel Rummery, who apprenticed in Underwood’s factories and later struck out on their own, sometimes employees of these larger firms continued that tradition by beginning their own operations. I.B. Hamblen, for instance, who originally migrated to Nova Scotia from Maine as part of the crew working for W.K. Lewis and Brothers near Halifax, went into business with fellow worker Benjamin Baker (originally from Massachusetts), to start Hamblen, Baker, and Company, a firm that continued on and expanded under Baker’s son.27

10 The other reason for expansion had less to do with the profitable nature of the industry and more to do with ecological change. While canning dealt with the problem of spoilage, it also allowed for an increased rate of exploitation and ultimately facilitated the overall depletion of lobster stocks. The pattern of depletion, which had important consequences for the ways processors and fishermen conducted themselves, again reflected key qualities of lobsters as a species. Lobster begin their lives as free- swimming larvae and gradually become oriented to the ocean floor.28 After descending to the bottom, they migrate at a slow pace to regions where the temperature and food supply are suitable – and in which there are large rocks or an abundance of cavities to inhabit thereby minimizing the risk from predators. Though generally they grow slowly, they can have a long life and can grow quite large (the largest recorded being as much as a century old and weighing upwards of 45 pounds). Untouched grounds contained many generations of animals, many of which were in the 4-10 pound range.29 That lobsters begin their existence and behave in this manner fundamentally affects their distribution and the amount of fishing effort a particular portion of the stock can withstand before becoming depleted. The most densely populated regions, and those most quickly replenished, are those regions (e.g., the heads of bays and places with an onshore wind) to which ocean currents and prevailing winds carry larval lobsters.30 Vast and dense stocks of the crustaceans made large factories viable over an extended stretch of the New England coast. Almost immediately, however, harvesters noted decreases in the average size of lobsters, as well as a scarcity of animals in easy-to-access, shallow areas and localized depletions elsewhere on the lobster grounds (probably in regions which, being further from the areas where prevailing winds and currents deposited larvae, were quickly depleted and slow to replenish).31

11 A large number of New England canners were well aware of these early signs of decline. While many of them successfully pressured their state governments to impose size limits and other conservation measures by the early 1870s, enforcement appears to have been difficult.32 Rather than conserving the resource, then, harvesters tended to offset the thinning of the stock and the depletion of large animals by developing new gears (first hoop traps and later cage traps, a version of which is still widely used today). Both gear types allowed fishermen to access stocks in deeper water and in ever more remote parts of the lobster grounds. Moreover, by decreasing the spacing between laths in cage traps, fishermen could offset an overall decline of larger, older animals by catching more, smaller lobsters for a time.33 While spatial and technological changes in the New England fishery during the mid- 19th century enabled processors to maintain their operations for several decades, these changes ultimately had a devastating effect on the overall health of the regional stock. Even while established canners, and sometimes their employees, rushed to cash in on the lucrative trade, then, declining stocks of lobster in areas long fished also forced them to find new sources of raw material.34

12 The assertion that with each passing year ecological degradation became more important as a determinant of the spatial orientation of fishing and of the structure of the lobster canning industry is not to suggest that the trade in Maine and other early centres of the fishery collapsed altogether. Indeed, in Maine the annual catch continued to increase until 1889 before an uneven but certain decline thereafter.35 As stocks declined, the concentration of large canneries, whose viability depended on comparatively dense stocks of lobster, gradually shifted up the eastern seaboard. In their wake a large number of smaller factories sprang up, often run by one or a few fishing families. The smaller operations allowed the trade to persist. They also further eroded the stocks laying off the New England coast, making a resurgence of the earlier predominance of large industrial processors unlikely. By 1872, for instance, there were more than 40 large lobster canneries in the Maritimes and Quebec, most of which were operated by New England firms. By 1880, however, the number of Canadian establishments had climbed to 200, and two-fifths of these were owned or controlled by US firms; the number of such canneries in Maine and Massachusetts had fallen to around 20. By 1890 the number of factories in Canada had climbed to at least 331 (133 in Nova Scotia, at least 100 in New Brunswick, and 98 in Prince Edward Island).36 Five years later, when canning ceased almost altogether in the United States, the number of operations in Canada had increased to approximately 650, though here again the large canners found it increasingly difficult to sustain themselves and smaller operations began to take their place.37

13 The advent of a commercial lobster fishery in Newfoundland was directly linked with these earlier developments in New England and the Maritimes. The small- scale, sporadic nature of the Newfoundland fishery before 1870 reflected that those operating on the west coast were aware of the growing market for the crustaceans, but also that lobster was not the target species. Instead, as a Captain Campbell, the first observer to provide a written commentary on the fishery on the west coast explained, those who canned the lobsters shipped in 1856 were Nova Scotians who traveled to the Humber River to can salmon. It appears that even though they targeted salmon, many Newfoundland fishers, like their counterparts who operated in Nova Scotia, were aware of the growing demand for lobster. By the middle of the 19th century, they were turning their attention to lobster after they finished with salmon for the season.38 Gradually the profitability of the industry and the decline of stocks further down the Atlantic coast translated into a regular, and increasingly vast, fishery dominated by large canners after 1873.39 Initially the expansion of the industry mostly reflected the migration of Maritime capitalists with prior experience in the lobster industry into Newfoundland.40 A Mr. Rumkey, a Nova Scotian, opened the first lobster factory in 1873 on the coast at Brig Bay near the tip of the Northern Peninsula. A number of other Maritime investors and firms soon joined him.41 In 1878 a Nova Scotian named Hutchings established a factory at East Bay on the Port au Port Peninsula, and this factory was the first in a series he built in the same area. Rumkey and Co. opened another factory in St. Barbe in 1881.42 And, while Maritimers dominated the Newfoundland industry in its early years just as American firms had dominated the early industry in Canada, the increasing size of the output also reflected a growing interest in the industry among some Newfoundlanders as well. The earliest Newfoundland-owned factory for which there are records is that of a Mr. Forsey of St. John’s, who built a factory in 1880 at Brig Bay (a community on the northern part of the Great Northern Peninsula). Not long after Forsey opened his operation, leading St. John’s merchant James Baird established a factory in 1882 at The Gravels (a settlement on the Port au Port Peninsula).43

14 A central difference between the New England fishery and those that developed after it was the pace of depletion. Natural barriers to over-exploitation, and particularly the rapid decomposition of lobsters themselves after death, limited the pace at which harvesters could exploit stocks initially. In fact, the history of the New England fishery was the history of overcoming such obstacles, first through the use of smacks, and later through immediately preserving lobster meat in bottles or cans. It was also the story of finding ways to collect large numbers of lobsters in the context of declining stocks through introducing or modifying gear types. Though there is little record of the way in which processors developed their system of removing meat from lobsters after they were cooked, it is reasonable to presume that a certain amount of trial and error was involved. In Nova Scotia, and later in Newfoundland, no such learning curve existed. Experienced fishermen also knew the best ways to catch lobsters in a variety of conditions. The comparatively rapid decline of the Maritime fishery (about 40 years as opposed to nearly 100 years for New England) reflected the greater efficiency with which harvesters and canners conducted their work.

15 In Newfoundland the first commercial lobster fishermen, like their counterparts further down the coast, encountered a virtually untouched stock. According to Wilfred Templeman, it probably consisted of about 20 generations of lobsters.44 Here, as in Nova Scotia, harvesters initially employed all of the methods that harvesters in Maine had earlier developed – including hooking, spearing, and hoop and lath traps – simultaneously. Moreover, during the earliest years of the lobster fishery many of the Nova Scotia-based firms brought their own workforces with them.45 Many of the factories employed 15 to 20 workers, though in some there were as many as 80 people employed and as many as 40 processors working in large facilities. Both men and women worked in processing at the outset, and all were paid a wage. It is not clear what wages workers received, but the division of tasks was similar to that which had earlier taken place in the Maine factories that Richard Rathburn had observed. In Newfoundland, as elsewhere, men took on “skilled” work such as soldering cans while women performed lower-paid tasks such as extracting meat from shells and filling and weighing cans.46 The actual catching of lobsters appears to have been predominantly a male preserve, and initially the factories paid fishermen with a combination of wages, room and board, and piece rates.47

16 The fact that skilled, experienced crews used proven technologies and methods on a nearly untouched stock meant that at the outset the factories were tremendously productive. In 1881, for example, Commander W.C. Karslake of the Fantome observed that there was a factory in St. Barbe. While it was owned by Rumkey and Co. (the same Halifax firm that started the first west coast factory in 1873), a Mr. Gower managed the operation. He brought with him from Nova Scotia 16 experienced hands. Gower reported that his crew landed about 5,000 lobsters a day for the period 1 June to 23 July. Mr. Hutchings’s two Port au Port factories were even more substantial. The factory at West Bay, for example, employed 34 men, women, and children. From 1 May to 1 August, this operation produced some 1,800 cases (86,400 one-pound cans) of lobster.48 It is difficult to determine exactly how many lobsters were represented by a can, for it generally took more than one lobster to produce a pound of meat. Moreover, there was no fixed ratio of animals to unit of processed product. In fact, the ratio changed as stocks were depleted and the average size of lobsters decreased. In 1886, however, most captains reported that the ratio of live weight to canned weight was on average two or three to one.49 At a slightly earlier time, there is evidence to suggest that in some locales the ratio may have been one and three quarters to one.50 The West Bay factory, then, would have caught somewhere between 173,000 to 250,000 lobsters. Hutchings had a still larger operation at East Bay. It employed some 80 people who packed a total of 2,800 cases of lobster during the same period. This factory also employed a number of tradesmen who manufactured cans and crates within which hands working at this and other Hutchings-owned factories in the area shipped product to market.51

17 After 1885 there was a considerable increase in the number of factories on the coast. In part, the increase reflected the addition of French factories. They established their first operation at Port au Choix in 1886 and continued to build several others thereafter.52 By the time the Mallard reached that factory on 24 June (having been in operation from around 1 June), the factory’s 74 employees had caught and processed about 48,000 lobsters (or about 2,000 lobsters per day).53 The increase in the number of factories also reflected the continued migration of Maritime capital to the region. Edward Saunderson, one of the naval authorities charged with patrolling the coast, indicated that a Prince Edward Islander named J. Cairns and his son had established a series of factories on the coast during the first half of the 1880s.54 Saunderson’s counterpart, W.R. Hamond, noted that Payzant and Fraser – a firm that Octave Payzant, a Liverpool, Nova Scotia, tinsmith, had pioneered – also established a factory in Bonne Bay in 1886, and it was no small concern.55 It employed 64 people (fishers and processors) and had for the first two weeks of its existence during the first half of June processed 1,000 tins of lobster daily. After that time, it produced on average 2,000 tins daily.56 By about the same time, S.S. Forrest, a Scot and one-time employee of Maine packer Burnham and Morill Company, entered the trade. Forrest, who first struck out on his own in PEI and who entered the Newfoundland fishery when he purchased Rumkey’s Brig Bay factory in 1881,57 reported that the 32 hands he employed had caught and processed about 40,200 lobsters. When the Mallardsailed into Port Saunders toward the end of July, the manager of the factory there related that the 32 hands employed at his establishment had caught and processed some 220,000 lobsters – filling just over 62,000 one-pound cans. The manager of Forrest’s Brig Bay factory reported that his 36 hands processed 404,640 lobsters filling 134,880 one-pound tins, while a factory at Bonne Bay had a similarly impressive year.58 By the end of the season in early October, that factory’s 50 hands produced about 115,000 one-pound cans, having caught and processed around 6,000 lobsters per day. 59 The following year Payzant and Fraser opened factories at St. Paul’s and at Woody Point in Bonne Bay. Fishermen caught as many as 8,000 lobsters per day in St. Paul’s, and at Woody Point they brought in about 7,000 per day, producing approximately 134,000 cans of lobster during the season. In addition to factories at North Head, Lower Crabb, Rope Cove, Portland Creek, Gull Marsh, and Sally’s Cove, Nova Scotians also operated plants at Port Saunders and Brig Bay where fishermen and processors frequently took from 4,000-7,000 lobsters a day and packed around 3,000 cases at each plant by the fall.60

18 The number of Newfoundland firms also increased considerably after 1885. In 1886 Thomas Carter opened a factory in Birchy Cove, and in the following year he opened factories on Wood Island and in Liverpool Cove in the Bay of Islands. Pleased with the success of his first operation on the Port au Port Peninsula, James Baird opened a series of factories along the coast (he eventually had factories in Lewis Brook, Broad Cove, Beach Point, and Round Head Cove). H.H. Haliburton, a native of St. Georges, began his career working as a manager for Baird. While he continued to work for Baird throughout the late 19th century, he also opened his own factories at Little Brook and Trout River in Bonne Bay. J. Halfyard of Bonne Bay soon joined Haliburton by opening factories in Lobster Cove and Berryhead Cove (areas just north of Bonne Bay).61 In 1887 a British captain charged with patrolling the coast noted that McDougall and Templeton, drapers from St. John’s, started a “small factory” (it employed 20 hands) at Codroy. At Sandy Point a Mr. Butt, according to the captain, a local man, had a factory that employed 15 people, while a Mr. Lance, also a local man, had a factory employing the same number of hands at St. Georges. By 1 July both Lance and Butt’s employees processed about 100 cases of lobster (4,800 one-pound cans). At Lark Harbour (a part of the Bay of Islands), a Mr. Bell of Fortune Bay had begun a factory employing 25 people and by the end of the season his workers had packed some 8,000 cans. At nearby Wood’s Island a factory was established as well, and there were plans afoot to start two more factories on the mainland nearby. Reportedly, workers at the Wood’s Island factory landed and processed about 2,500 lobsters per day.62

19 By 1888 there were at least 33 factories, 29 English and 4 French, on the west coast. At this time the factories employed more than a thousand people. While in the early years most factory owners imported crews, by the early 1880s residents of the coast comprised the bulk of the labour force. Most workers entered the trade because it was lucrative.63 During the early to mid-1880s, the income fishermen could have procured in this industry was significant despite the fact that they received what seems now a paltry sum for their catch (50-60 cents per hundred lobsters in 1887). The sheer abundance of the crustacean when the fishery first began meant that a harvester could do well in comparison to other available occupations. Take, for example, S.S. Forrest’s factory at Brig Bay. In 1886 it employed a total of 36 hands. Of those, 23 were processors and 13 were fishermen. Fishing began at Brig Bay on about 1 June. In about two months (the captain of the Mallard visited the factory on the 10 and 11 August) the 13 fishermen had caught some 404,640 lobsters. On average, this would have worked out to about 5,800 a day, a figure that was often surpassed at other factories on the coast during the first years of the fishery. In total, this number translated into 134,800 one-pound cans of lobster.64 It is not clear what wage the processors were paid, but the fishermen would have received a total of $2,023.20. Assuming that each fishermen caught about an equal share of lobsters, and assuming that they used company-provided gear and received the lower piece rate, each would have received about $155.63 for the entire 71-day period, or about $2.19 per day.

20 At about the same time most common labourers in St. John’s received less than a dollar a day while workers constructing the railway received exactly a dollar a day, and newspaper editors, politicians, and workers themselves considered that a good wage.65 Moreover, the comparison holds even if we move outside of Newfoundland and the Maritimes. A survey of evidence presented to the Royal Commission on the Relations of Labour and Capital (1889), for example, reveals that adult male industrial workers in Ontario received from 90 cents to $1.00 per day for 12 hours work.66 A fisherman working at a reasonably (but by no means the most) productive area on the west coast, then, would have received at least twice the wages of those working in other positions open to them. Of course, the fact that large numbers of Maritimers initially traveled to Newfoundland to work in the lobster fishery, and that residents of the coast eagerly replaced them, is itself evidence that the expected earnings were comparatively high. By the 1880s in the Maritimes, as in Newfoundland, there was a well-established tradition of working people travelling to other parts of Canada or to the United States when jobs were scarce at home. There is no reason that such men and women should have travelled to Newfoundland if wages were better elsewhere.67

21 High wages and substantial returns on investment, therefore, were clearly important in attracting resident fishermen and different mercantile groups operating on the treaty shore to the lobster fishery. At the same time, however, changing ecological conditions outside of the fishery also encouraged the migration of labour and capital into the trade, even if the motivations for distinct groups of investors and working people involved differed. Most of the Newfoundland merchants interested in the trade, for instance, operated out of St. John’s. For them, the mid-1880s was a gloomy time. Declining catch rates in the shore fishery and a global depression were themselves disconcerting. These tendencies were, however, exacerbated by structural and production problems within the fishery itself. To deal with declining catch rates, merchants restricted credit to fishers who could and would invest in technologies like bultows, cod seines, and cod traps that enabled them to catch more of a declining resource locally, or to those who could afford the larger vessels needed to seek out and harvest fishing grounds either further offshore or in more remote regions off the coast of Labrador.68 The intensification of fishing effort on the Grand Banks and Labrador fisheries helped, at least temporarily, to solve the problem of declining catch rates. Yet it also meant that processors (the “shore crew”) had to contend with large quantities of fish all at once. At the same time, the introduction of steamers, which carried larger cargoes than ever before, changed the dynamics of the fishery for exporters significantly.69 To command the best prices for fish, Newfoundland exporters had to get their products to market before their Norwegian and French competitors. The emphasis on both getting cargoes together and getting fish to market as quickly as possible led merchants to relax their standards. Indeed, during the last half of the 19th century many fish exporters, and particularly those dependent on the Labrador fishery, began purchasing fish tal qual (just as they come). With decreased selectivity, fishers often concentrated on catching rather than curing fish, and overall there was a decline in the quality of fish produced in Newfoundland that, in the long term, made it difficult to capture a larger share of rapidly expanding foreign markets in the late 19th century.70 The decline in the competitiveness of Newfoundland fish, in combination with increased tariffs in what had been key markets for the island’s exporters, only made an already difficult situation worse.71

22 The resident population of fishermen on the west coast faced a slightly different set of issues. A decline in the cod fishery would have had an adverse affect. Yet, the nature of cod stocks in this region meant that declines in this fishery were probably not as important for settlers as they were for those living in other parts of the island. Most cod caught on the west coast were part of a migratory stock.72 In the spring of the year, the fish would move along the west coast following the Esquiman channel (a deep trench that runs parallel to most of the west coast of Newfoundland and that nearly touches shore at Port au Choix) and would come into shore in pursuit of capelin and other pelagic fish like herring.73 They first struck land near the Port au Port Peninsula and gradually made their way up through the Strait of Belle Isle and on to Labrador.74 As such, fishermen on the coast probably were not as dependent on cod as were their counterparts on the east coast. While fishermen did engage in intense periods of cod fishing as the fish passed through the waters near their communities, their livelihood depended on other fisheries as well. In the early years of settlement during the early 19th century, many residents of the coast engaged in salmon fishing as stocks of this fish fell off drastically in Europe and the United States.75 They also hunted seals extensively76 and, from about the middle of the 19th century, the west-coast herring fishery grew substantially, both as a result of the depletion of stocks off the United States and the Maritimes and from growing demand for protein among expanding urban-industrial populations in Europe.77 In fact, a substantial number of the region’s settlers first migrated to the coast from Nova Scotia to pursue this trade, selling the fish as both food and as bait to French, American, and Newfoundland bankers that became important as the shore fishery dissipated.78

23 The last decades of the 19th century were less than prosperous for all of the west coast fisheries. The herring fishery, once the staple fishery in the Bay of Islands and elsewhere on the west coast, for instance, dropped off after 1860.79 By the 1860s the seal herds off the west coast were depleted as well.80 There were also troubling signs in what had been a staple for many residents – the salmon fishery – during the early 1860s. By the middle of the 19th century, after about four decades of sustained fishing, government officials and harvesters began to notice a falling off in the numbers of fish landed in some localities. The depletion was noticeable enough that the government undertook a formal inquiry into the fishery during 1860. Matthew H. Warren, originally of Devon, England, conducted the inquiry. He was familiar with the history of the salmon fishery in the British Isles. He noted that salmon had once been abundant in Britain. In fact, so common and so inexpensive was the fish that “it was often . . . inserted in . . . Apprentices’ indentures that they should not be compelled to eat Salmon oftener than twice a-week.” While at one time “almost every river in the United Kingdom and Ireland swarmed with Salmon,” the “vile practice of fishing at all times and seasons and by all appliances has driven the dogged, but noble fish from many rivers, and lessened the numbers frequenting others, causing destruction of a greater portion of the fisheries.” The decline of this fishery in Britain and in the northeastern United States is seemingly partly what inspired early merchants in the Straits of Labrador such as Thomas Bird to pursue the fish, as a market for salmon still existed in Britain even though the fish did not.81 Warren argued that while the salmon fishery of Newfoundland was “as valuable as those of any of the British Provinces,” if some means were not devised, “and laws enforced for their preservation, their total annihilation will be the consequence.” 82

24 Over the next several decades naval captains visiting the west coast continued to comment on declining catches and destructive practices. By 1880 the situation had become serious as catches in once-productive rivers like the Torrent and East Rivers just south of Port au Choix declined from annual yields of around eighty barrels of salmon a year each to just one-and-a-half barrels a year.83 The cause of the decline, according to W.H. Kennedy, captain of the Flamingo, was clear. Despite longstanding warnings about the dangers of doing so, commercial fishers from Newfoundland and elsewhere barred the rivers with nets and other devices thereby catching a large percentage of the fish that ascended the rivers and preventing them from laying their eggs. As Kennedy observed: “There is hardly a river or brook in this country which is not beset with either, weir, mill-dam, trap, net, or other engine which the ingenuity of man can devise for the capture of salmon in defiance of all laws, proclamations, and the dictates of humanity or common sense.” In some streams, he continued, “the practice has been carried out so persistently for many years, that the salmon have deserted the river altogether.” While he and other captains could prevent people from barring rivers when they encountered the practice, they were well aware that after they left, fishers basically did as they pleased. The result was a general decline in the fishery. As Kennedy noted, “‘salmon is scarce’ is the doleful cry where-ever we go round these coasts.”84 Over the next several years naval captains reported that the “doleful cry” remained the same and the words “scarce” and “nil” filled the portion of most logbooks devoted to salmon.85

25 In this context of decline, and in some cases exhaustion, of local fisheries, the lobster fishery was an industry of last resort. For many working people, the situation was desperate. While some could migrate to take up work elsewhere, many had no such options.86 For them ecological degradation meant hunger and privation, and naval captains and other officials on the coast noted the increasingly dire straits in which many residents found themselves.87 In 1887, for example, the local justice of the peace in Bonne Bay reported that in the previous winter about 150 families had applied to the government for relief. While a number of barrels of flour were forthcoming, residents of the bay received little else and many families were “half naked,” had no blankets, and had to “lie around their stoves at night in winter to keep alive.” It is likely that malnutrition contributed to the outbreaks of disease about which naval captains reported with increasing frequency.88 In this setting, the lobster fishery was an important alternative. In fact, according to the justice of the peace, “the only people who could support themselves were those who had worked in the lobster factories.”89 It is not surprising that by this time factory owners from the Maritimes no longer imported their crews, for an abundance of desperate men and women on the coast, as Nova Scotia canner William Anguin later recalled, made this a “needless expense.”90

26 For the French, the situation was different again. Preliminary evidence suggests that the long-noted late-19th-century decline in the east coast shore fishery was an island- wide phenomenon. Fishermen on the west coast, like their counterparts in the east, had to use more intensive gear to maintain catch rates, and they noted an overall decline in the size of the average fish.91 The decline of this fishery made it unprofitable for the French, causing them to abandon long-held rooms on the coast and to focus more on the bank fishery.92 For them, the lobster fishery served a variety of ends. In the context of a declining shore fishery, it helped them to provide their colonists on St. Pierre and Miquelon with a livelihood and an area of investment.93 It also, however, had to do with more than just the lobster fishery per se. Aware of the declining prospects in the shore cod fishery, and hoping to create a disincentive for key competitors in the cod fishery, the Newfoundland government passed the Newfoundland Bait Act in 1888 that restricted French purchases of bait on the south coast.94 Unable to prosecute the still lucrative bank fishery without a local source of bait, the French depended all the more heavily on the west coast herring fishery in particular. In maintaining a presence on the shore, they sustained their claims to the fishery in the region and to the bait necessary for the prosecution of their offshore fishery.95

27 The appeal of the lobster fishery for both merchants and working people translated into a dramatic increase in investment and output during the late 1880s. After a slight decline in the early 1880s, exports increased to just over 2,000,000 pounds for Newfoundland as a whole in 1887. The following year those engaged in the trade shipped over 3,300,000 pounds, and in 1889 exports reached almost 3,700,000 pounds of processed lobster (which represented nearly 18 million pounds of live weight). While there are no reliable annual statistics, in 1888 west coast canneries produced just over 1,300,000 pounds (more than half of the total Newfoundland catch).96 The late 1880s and early 1890s, however, marked an important turning point in the history of the west coast lobster fishery. There was a decided shift away from the large, industrial processing facilities, coupled with the emergence of a large number of smaller operations. In part this shift had to do with changing diplomatic arrangements governing the coast. In 1890 the imperial government imposed limitations on new entrants into the industry on the west coast. Two years later it also allotted particular lobster grounds to each factory in the hopes of pre-empting conflict among increasingly competitive factions of merchants interested in the trade.97 St. John’s merchants, who increasingly saw the west coast as rightfully part of their “island home,” found the limitations on their participation, or expanded involvement, in the lobster fishery unacceptable. Fishermen on the west coast, in increasingly desperate straits because of the falling off in other staple fisheries within the region, objected to the de facto system of private property rights that grew up under these new rules because this regime made it more difficult for them to negotiate higher prices for their catch at precisely the moment when a maximal price was imperative.

28 It is impossible to explore all of the implications of these rifts and schisms in this article.98 Nevertheless, one of the central outcomes of this situation was that, for a time at least, merchants (primarily St. John’s merchants) were excluded or limited in the fishery, and the poorer residents of the west coast collaborated in an illicit trade that satisfied the needs and aims of both parties. The clandestine nature of this trade meant that small, temporary factories made sense. Such operations were generally small and easily disassembled and hidden in the woods at the sight of a naval vessel.99 Ultimately, though, the illicit trade produced both social tensions and a finished product of uneven quality, the latter of which threatened to give the Newfoundland pack more generally a “bad name.”100 As a result, the British sought to quell unrest and to rid the industry of the small operations by opening all lobster grounds assigned British canners to fishermen. The idea was that British canners would have to pay fishermen a competitive rate thereby reducing the desirability of canning illicitly.101 Even while diplomatic circumstances may have first encouraged small-scale production, the small factories that predominated the illicit trade of the early to mid- 1890s became more pervasive as time went on, though the key cause of this tendency had more to do with ecology than politics, diplomacy, or class tensions.

29 Like lobster stocks off Maine and the Maritimes, those off Newfoundland showed signs of localized depletion (probably in areas furthest from the places in which larval lobsters first descended to the bottom) not long after the fishery began in earnest. St. Barbe, for example, was one of the earlier localities in which canners began operations. By 1885 the captain of the Tenedos reported that the factory was “not doing well as lobsters are scarce.” By the following year harvesters had thinned the stock to such a degree that the factory owner moved his establishment to Brig Bay, as there were no longer enough lobsters in the original locality to sustain the operation.102 The following year Commander Karslake of the Fantome reported similarly that in Bonne Bay “large quantities of Lobster have been taken.” He suggested, however, that the prevailing rates of exploitation could not be sustained, and that to ensure the long-term viability of the fishery “it would be advisable to have a closed season yearly.” Several years later, in 1887, Lieutenant Masterman of the Bullfrog, although making recommendations about managing the fishery, noted that he had been coming to the coast for several years, and observed that the decline of the cod and salmon fisheries meant that the lobster fishery had “attracted many fishermen.” He believed that the crustaceans were “by no means fished out.” Indeed, in that year especially the lobster factories at Brig Bay and Port Saunders had “not had a bad season.” Yet he was also aware that the lobsters were “neither so plentiful, nor so large as they were a year or two ago on this part of the coast.”103

30 It turned out that Masterman was correct. The overall catch continued to increase after 1887 and, as in localities further down the Atlantic seaboard, the catch of 1889 was enormous. Yet the Newfoundland case differed somewhat from New England and the Maritimes. In Newfoundland the stock was never as extensive as it was further down the seaboard.104 As a result, it could sustain the intensive levels of exploitation for a comparatively short period of time; despite its comparatively late start, the fishery peaked on the west coast at about the same time as fisheries further down the seaboard. In fact, 1889 was the most productive year in the history of the Newfoundland lobster fishery. By the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, every indicator pointed to a marked decline in lobster stocks. Virtually every interviewee with knowledge of the lobster fishery, for instance, told commissioners inquiring into conditions on the treaty shore in 1898 that lobsters were both fewer in number and smaller than in years past.105 Some, such as H.H. Haliburton, agent for St. John’s merchant James Baird and a factory owner in his own right, were more precise. At the time of the commission he had resided on the west coast for about 15 years. He recalled that when he first arrived, “from 13⁄4 to 21⁄4 was the average number of lobsters to a one pound can” at his factories. By 1898 that number had increased to “from 5 to 8 lobsters to the pound can.”106 Commodore Bourke noted that in some places conditions were even more desperate. As he explained, it took between four and a half to five nine-inch lobsters to fill a one- pound tin. While he personally had seen factories having to use eight to fill a can, he also had heard that in locales such as the Bay of Islands that number was sometimes as high as “twelve to thirteen to the 1lb. tin.”107 Changes in the ways factory owners paid for lobsters further reinforced his observation. While they continued with the earlier practice of paying for the crustaceans by the hundred, by the later 19th century factory owners began to count two or three lobsters as one because at that time it took two to three lobsters to equal what had been the weight of one average lobster in earlier years.108 Moreover, even while overall catches remained respectable, it took more gear to acquire the same yield. As Bourke noted, in 1898 the French factories fished 3,000 more traps than they had the previous year and still they only managed to catch the same amount of lobster. During that same year, the English factories fished 6,000 more traps than the previous year and they managed to pack 3,000 less cases of finished product.109

31 The absolute decline in the size and number of lobsters available ultimately resulted in the same outcome in Newfoundland as it had further down the coast at an earlier time. As the stock off western Newfoundland thinned, it became increasingly difficult to sustain the large, capital intensive concerns common in earlier years.110 Even while the salmon fishery improved in some places during the last years of the 19th century, the depressed circumstances that emerged after 1880 persisted – making the continuation of the lobster fishery in some capacity all the more urgent. Instead of abandoning the lobster fishery, then, fishers changed the way they conducted their trade. In essence, they expanded the practices that emerged in the illicit trade of the earlier 1890s. They abandoned large, capital intensive operations based on wage labour in favour of small operations run by one or a few families. They established these canneries, received tins needed to preserve lobster on credit, and sold whatever they produced to the supplying merchant. The division of labour strongly resembled that which prevailed in Newfoundland’s cod fishery at the same time. Men fished for lobster using gear that they and their families crafted from local materials. Women and children (those traditionally comprising the “shore crew”) processed and canned the lobsters, sometimes with, and sometimes without, the help of the men. In this arrangement, the merchant did not pay wages; instead, he deducted the cost of goods advanced from the total value of whatever a family produced and paid the surplus either in goods or cash.111

32 With each passing year the average size of a factory and, despite a few deviations, the overall catch, decreased (see Table One). In 1888 west coast factories produced some 27,880 cases (approximately 1,338,240 cans) of lobster. The smallest factory canned 300 cases, and the largest three canned 2,000, 2,800, and 3,000 cases respectively. After catches reached their all-time high in 1889, the evidence suggests that the number of factories increased dramatically – though it also suggests that the amount processed by each factory declined precipitously. In 1891, for instance, there were 84 factories worth an average of nearly 500 dollars processing an average of 144 cases each. Ten years later the number of factories had grown to 162, with each factory worth on average about 140 dollars and producing just over 60 cases of lobster. In 1911, the trend toward smaller facilities showed no sign of abating. According to the census, there were 683 factories on the west coast in that year. The average value of a factory was about 70 dollars, and on average each produced just under 19 cases of finished product.112

33 Both fishermen and government officials were well aware of the decline of the industry on the west coast and throughout Newfoundland. They were also cognizant that the roots of their own fishery lay partly with the devastation of stocks further down the seaboard, and they put in place measures to guard against the destruction of this industry. Indeed, in 1889, on the recommendation of Superintendent Adolph Nielsen of the recently created Newfoundland Fisheries Commission, the Newfoundland government required that packers be licensed, imposed minimum- size requirements, stipulated the times at which fishermen could pursue the crustaceans, and required that spawn be removed from egg bearing (“berried”) lobsters and delivered to lobster hatcheries operated by the commission (later the government would require that berried lobsters be returned to the sea).113 If followed, such regulations might have had an ameliorative affect. Yet in some of the most productive lobster grounds on the west coast the rules did not apply until after the 1904 Entente Cordiale, when the territory fell under the jurisdiction of the Newfoundland government. Moreover, often fishermen in other parts of the island were hard pressed by declining returns from other fisheries and scraping to make a living. Coupled with the fact that the number of wardens present to enforce the laws were few in number, often fishermen were willing, especially in years when lobster fetched a high price, to disregard the regulations.114

34 Difficulties of enforcement meant that despite numerous warnings, the annual catch continued to decline. As early as 1904 there was support from some fishermen and traders involved in the industry, and particularly those in districts where the decline was particularly sharp, to close the fishery for a number of years to prevent its total collapse.115 Department officials hesitated to do so, however, both because it would mean a loss of revenue for the government and because it would bring “hardship and loss” to both traders and fishing families who depended on the industry even though it was in decline.116 Instead, they initially attempted to establish a new program of propagation. Rather than removing the eggs from lobsters, as Nielson had recommended be done in the 1890s, in 1912 fisheries officials began a program of buying berried lobsters from fishermen and depositing them in holding areas (either salt water ponds or pounds).117 While department officials spoke optimistically about this program in the years immediately following its debut, as stocks thinned to a greater degree with each passing year their enthusiasm waned. Indeed, by 1918, after several years of attempts to propagate the crustaceans, detailed reports of these operations changed to hollow assurances that the fishery was “undoubtedly rapidly recuperating” – even though catch rates declined unabated in many districts.118 After 1920 department officials quit discussing the program in their annual reports and made virtually no reference to the fishery in any capacity.

35 By 1921 stocks thinned to such a degree on the west coast that it was no longer worthwhile for even those operating small factories to pack the crustaceans, and for the first time in several decades the number of operations dropped slightly (to 677). By this time the average value of a factory on the coast had declined to just under 40 dollars and each produced an average of just over ten cases. This rate was better than Newfoundland as a whole. The average for the island had dropped to about 6 cases per factory. Yet the rate of production was still a far cry from the 1880s.119 While the fishery on the west coast, as elsewhere, persisted for a few more years, the unrelenting pressure on local resources had a devastating effect. By the early 1920s, yields dropped to such low levels that significant numbers of both fishermen and businessmen who were engaged in the trade urged the colonial government to impose a closure in the fishery. In 1925, the total catch dropped to about 750,000 pounds of live lobsters (about 150,000 pounds processed) for the entire island. Well aware of the fact that their industry was in jeopardy, a growing number of fishermen and traders called for a closed season. Early during the following year the government heeded this advice and passed “An Act Respecting the Lobster Fishery,” which imposed a moratorium, seemingly the island’s first, on lobster fishing for a period of three years from 1925 to 1927.120 While the yield in the year after the moratorium ended climbed back up to over four million pounds of live lobster for the island, over the next several years it slumped back to under two million pounds, and it has never since approached the massive catches of the 1880s.121

36 The association of Newfoundland with the cod fishery is strong, and it exists for good reason. After all, it was this fishery that not only brought non-Aboriginal people to the island but also sustained them to greater and lesser degrees for five centuries. Other marine species, though, have been important to the island’s economy and society. And even while the changing nature of fisheries outside of the cod fishery may have been shaped by the island’s staple industry, they had their own separate logics and trajectories. Newfoundland’s west coast lobster fishery was fundamentally linked with earlier fisheries further down the eastern seaboard. Nova Scotia capitalists pioneered the Newfoundland trade as a way to expand their businesses and to escape the ecological destruction they themselves had initiated at an earlier time off of their own coasts. Maine capitalists seeking both opportunity and refuge from similar circumstances had pioneered the Nova Scotia fishery at an earlier date. After the advent of large-scale processing on the west coast, the Newfoundland fishery followed a pattern similar to those elsewhere in northeastern North America. Initially, the virtually untouched stocks lying off the island’s coast sustained large industrial processing facilities that sometimes employed several dozen workers. After about two decades of fishing, stocks thinned and the average size of the lobsters caught declined – necessitating a transformation in the way in which harvesting and processing took place. Increasingly, small factories operated by fishing families and supplied through the traditional credit system came to predominate. Such changes allowed a profitable, if substantially reduced, trade to continue for a time. Ultimately, however, the continued harvesting had devastating effects on the overall health of the stock and led to the earliest government-imposed moratorium in Newfoundland’s history.