Articles

Nova Scotia Lost and Found:

The Acadian Boundary Negotiation and Imperial Envisioning, 1750-1755

Abstract

The Acadian boundary negotiations (1750-1755) marked a transition in the use of geography as an imperial tool. The discussions followed a two-step process: appointed commissioners representing Britain and France pored over old maps and geographic tracts but were unable to identify the most "ancient" Acadian boundary; direct diplomatic discussions then used cartography in an attempt to establish mutually agreeable limits in the northeast. These debates were shaped by Atlantic connections and competing Euro-Aboriginal claims to sovereignty. In lieu of material power on the ground, geography was used as a multi-faceted tool to address overlapping territories and the threat of war.

Résumé

Les négociations entourant les frontières de l’Acadie (1750-1755) marquèrent une transition dans l’utilisation de la géographie en tant qu’outil impérial. Les discussions se déroulèrent en deux étapes : des commissaires nommés représentant la Grande-Bretagne et la France étudièrent de près de vieilles cartes et de vieux lotissements géographiques, mais furent incapables de déterminer la plus « ancienne » frontière de l’Acadie. Ensuite, des discussions diplomatiques directes eurent recours à la cartographie en vue d’établir des limites acceptables pour les deux parties dans la région du nord-est. Ces débats étaient façonnés par des relations atlantiques et des revendications concurrentes entre les Européens et les Autochtones en matière de souveraineté. Au lieu de la puissance matérielle sur le terrain, les parties en cause utilisèrent la géographie comme un outil aux multiples facettes pour régler la question des territoires se chevauchant et la menace de guerre.

1 IN JULY 1755, THE FRENCH MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS angrily dispatched Étienne Silhouette, who represented France at the Acadian boundary negotiations, to "scold" one of France’s most prominent geographers. 1 Their meeting went unrecorded, but Silhouette apparently chastised Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon D’Anville for producing maps that supported Britain’s claims to Nova Scotia and Acadia – a strategic part of northeastern North America that France was loath to surrender. French geographers were not unaccustomed to state reprimand. In the 17th century, Louis XIV is claimed to have quipped that French surveyors shrunk his kingdom more than any opposing army; according to French administrators nearly a century later, D’Anville was continuing that trend. 2

2 Perhaps D’Anville should have foreseen that Nova Scotia would become the site of sustained geographic competition. The region, with its amorphous and contested boundaries, existed as at least three separate places: for the French, it had been Acadia since the arrival of Sieur de Mons in 1604; for the Mi’kmaq, the land was part of Mi’kma’ki and had been since time immemorial; and for the British, it had been New Scotland since King James I/VI granted the land to Sir William Alexander in 1621. The region’s boundaries advanced and retreated with wars and treaties throughout much of the 17th and 18th centuries as the British, French, and Aboriginal groups competed and negotiated for territorial control. In 1713, at the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht that ended the War of Spanish Succession, the British and the French decided to leave the determination of Acadia’s exact boundaries to a future date. In the 12th article of that peace (dealing with the delicate question of territorial sovereignty), France ceded to Britain

2 Britain was awarded Acadia or Nova Scotia "according to its ancient limits." In an imperially strategic region with poorly defined boundaries, these ancient limits would be hotly contested. France hoped to keep Britain pinned to the peninsula’s eastern coast, while the British hoped to extend Nova Scotia to New England.

3 The years 1750-1755 represented a transition point in the use of geography as an imperial tool. Using Nova Scotia as an example, this article advances the argument that geographic knowledge – including maps, geographic tracts, surveys, and discussions of limits and boundaries – was a diplomatic tool used to negotiate territorial sovereignty given weak political authority and limited military power. 4 There were two distinct attempts during this period to resolve the geographic uncertainties surrounding the limits of Acadia/Nova Scotia. The boundary commission, which met from 1750 to 1753, used maps to determine geopolitical location and argue for Acadia’s "ancient" boundaries. After these meetings failed to resolve the issue, direct diplomatic negotiations held in 1754 and 1755 relied on geography not only to determine the extent of Acadia’s limits, but also to resolve issues on the ground by using maps to create new boundaries and address geopolitical disputes. 5 In both instances French and British officials were frustrated by the lack of reliable surveys, and both crowns took lessons from the Acadian experience and applied them to future imperial endeavours. By the mid-1760s the British had launched an extensive survey of their North American territories and had initiated a massive cartographic project in India, both of which were meant to incorporate new territories into the British Empire. Similarly, French officials under Napoleon used surveys and maps in an attempt to transform Egypt into French territory after its invasion in the late 18th century. 6 The Acadian boundary negotiation was a crucial moment for the development of imperial geography. Maps and surveys transitioned from tools used to express past possession to methods by which empires could express authority over territory in light of weak material power on the ground. 7

4 The years leading up to and during the negotiations were far from quiet ones in Nova Scotia, and local actions increased the pressure on imperial administrators to prevent future conflict. After the British founded Halifax in 1749, there was a flurry of fort construction. The French built or strengthened forts Beauséjour, Menagoueche, Nerepis, and Gadiaque, while the British erected forts Edward and Lawrence. Another source of contention was France’s forced removal of Acadian settlers from the English to the French side of the isthmus of Chignecto. In 1750, Governor Cornwallis of Nova Scotia learned that Louis La Corne, a French officer, and the missionary priest Abbé Le Loutre were working to strengthen the French settlement at Beauséjour by forcing Acadians to remove themselves from their village at Beaubassin to the French part of the isthmus. Their method was to encourage migration by threatening the Acadians with massacre and burning their houses. 8 Their threats were not idle ones, and Beaubassin was eventually burned to prevent the British from taking it. While the British demonized Le Loutre for his actions, the priest had the support of officials in Quebec and France making it difficult to determine where official orders ended and his own volition began. 9 When British officials in London learned of La Corne’s actions, they discussed how best to deal with the situation. The Duke of Bedford wrote to the Earl of Albemarle, the British ambassador to France, asking him to force the issue on the French and request that the matter be settled. Should the French do nothing, it "may destroy the good intelligence which subsists between the two crowns." 10 Negotiating a suitable boundary was not an intellectual exercise, but rather a necessary response to local violence and the threat of another war in North America.

5 Historians have increasingly looked to maps and geography as a lens through which to explore the past. The cartographic theory of J.B. Harley, who argued that maps were not simply representations of space but rather political texts capable of making or refuting arguments about territory, has had wide influence. 11 Yet recent scholarship has suggested moving beyond the dichotomy of maps as reflections of physical geography or as cultural and political texts that represent the biases of the mapmaker or map reader. Following Paul Mapp, this article will examine how extant geographic information, regardless of its source or method of construction, influenced those who had to make decisions about territory. 12 This article will focus on both the boundary commission – comprised of official representatives for both Britain and France – as well as the subsequent diplomatic discussions that gained momentum in 1754 after the boundary commission stalled. These two attempts at resolving territorial issues demonstrate the malleability and multifaceted nature of cartographic investigation, and its centrality to imperial competition.

6 As these discussions progressed, maps were used for distinct purposes. During the official meetings of the boundary commission, British and French representatives attempted to determine which maps were "ancient" enough to address the question of Acadia’s limits by poring over old maps, questioning the biases of their creators, and comparing maps to treaties and state correspondence. Did Acadia and Nova Scotia overlap? Did Nova Scotia exist before 1713, or was it simply a "mot en l’air"? Largely ignoring the Aboriginal claims to much of the northeast, the commissaries sought authority and legitimacy in ancient geographers and their maps. 13 The diplomatic discussions, on the other hand, used cartography as a tool with which to create new boundaries and new territorial authority while juggling British, French, Acadian, and Native claims to territory on the ground. Instead of arguing over decades-old boundary lines as selected by long-dead geographers, diplomats (to a certain degree) recognized or assigned Native space on maps while plotting new limits that would then be imbued with political authority. Put simply, during the Acadian boundary dispute geographic knowledge was used as evidence to argue for a specific version of the past and as a tool to construct imperial boundaries and assert territorial authority. Geographic information existed as one element in a complex matrix of methods (including war, settlement, and establishing legal regimes) used to claim sovereignty over a region, but its use was not static.

7 There is an abundance of research on Nova Scotia and Acadia that examines the region’s connections to New England, and its influence in British North America, but too few scholars have sufficiently examined the signal contribution the Acadian boundary negotiations made to ideas of imperial governance and geographic authority. 14 John G. Reid has made compelling arguments for incorporating the Mi’kmaq and Wulstukwiuk (Maliseet) influence on local and imperial affairs, arguing that the Mi’kmaq and their allies retained significant influence in the region into the early 19th century. 15 The boundary dispute illustrates that despite the appointed commissaries’ disregard of the Native groups who controlled much of the territory in Nova Scotia, Native territorial strength and positioning did in fact contribute to the diplomatic discussions indirectly by shaping opinions on how new boundaries were to be drawn. There is also work on early Atlantic Canada’s cartographic history, much of which lays a solid foundation onto which future work can build. Joan Dawson’s analysis of early maps of Nova Scotia demonstrates how depictions of the region served imperial purposes, while John G. Reid has examined how British officials after the 1707 union with Scotland exploited Sir William Alexander’s settlement of "New Scotland." 16 Yet several studies on 18th-century Acadia and Nova Scotia overlook or downplay the Acadian boundary commission. For example, John Mack Faragher argues that the negotiations "in the end produced no result." 17 Map historians have come to similar conclusions about the commission; Mary Pedley’s examination of the commission’s published reports, for instance, concludes that cartography had no real influence on the proceedings. 18 Yet in the absence of other expressions of British or French sovereignty, such as military prowess or established legal regimes, imperial administrators looked to geography – manifested in assertions of boundaries and definitions of space – to negotiate authority over contested territory. In effect, during the Acadian boundary dispute maps and geographic knowledge became the language of negotiated sovereignty used to prove past possession, disprove untenable territorial assertions, and project future imperial holdings in a region where material power was almost non-existent. Rather than simply informing imperial visions, maps and geographic knowledge became the avenue through which decisions were made.

Commissaries and the commission

8 Boundaries had been a topic of concern in Nova Scotia since 1713. The Treaty of Utrecht assigned no official limits, and the weak British presence stationed at Annapolis Royal – one of several pales under British authority – was powerless to control the Acadians and Mi’kmaq (both of whom continued to live largely as they had before the treaty). In the 1720s the British and French attempted to regulate Nova Scotia’s limits, but to no avail. The British-Mi’kmaq treaty process that ended Dummer’s War in 1726, for instance, included declarations of peace and friendship, but never land surrender. For the Acadians, the first decades of British rule in Nova Scotia witnessed what N.E.S. Griffiths has called a "golden age" during which population and prosperity increased in large part because British officials at Annapolis Royal were incapable of exerting influence over the region’s French inhabitants. 19 Only at the end of the War of Austrian Succession in 1748, followed by the British founding of Halifax in 1749, did Britain and France fully realize the importance of settling the Acadian boundary before another war broke out. The stalemate that lasted (officially) from 1748 to 1756 provided a window for each to air their geographic grievances, which became increasingly necessary as both sides continued to shore up defences on the ground. 20 The meetings themselves provided a forum in which the British and French could evaluate maps and discuss their utility as evidence. Anne Godlewska has characterized 18th-century French geographers as concerned less with establishing limits and boundaries than with developing "a language of representation sufficiently simple to be widely understood and rich enough to fully express a growing knowledge about the world." 21 Yet it was likely not that simplistic. Christine Marie Petto has recently argued that by mid-century French geographers provided positivist information "to administrators . . . who sought to classify better their domains in an effort not only to know the extent of the lands they controlled but also to be more effective administrators." 22 Members of the boundary commission were thus faced with evaluating geographic evidence that not only aimed to create a comprehensible language of space, but also contributed to establishing reliable content in respect to geopolitical positioning.

9 Appointing commissaries to settle the Acadian boundary illustrates the importance of combining local knowledge with an understanding of geography. France selected the Marquis de la Galissonière, a naval officer and former commandant of New France who worked in the Dépôt des cartes et plans de la Marine, and Étienne de Silhouette, a French civil servant whose published works on economy and trade had caught the attention of French administrators. The British chose as their commissaries William Shirley, the governor of Massachusetts Bay who had commissioned Charles Morris to create maps of Nova Scotia, and William Mildmay, whose step-brother was Robert D’Arcy, the Earl of Holderness. The first task these men faced was determining the order in which three topics would be discussed: the possession of St. Lucia, the Acadian boundary, and compensation for ships taken since the War of Austrian Succession. It was not long before Acadia emerged as the most pressing issue. The Duke of Newcastle wrote: "I think [Acadia] the most ticklish, and most important point, that we have almost ever had, singly, to negotiate with France." 23 For that reason, both the French and the British commissaries were given explicit instructions for the negotiations. La Galissonière and Silhouette were informed that the ancient limits of Acadia ran from Canso to Cape Forchu (present-day Yarmouth, Nova Scotia), and did not include Port Royal, which was ceded separately at Utrecht. Part of the peninsula and Canso belonged to France, but those lands could be ceded if the British promised to leave them vacant. In return, the French expected the British not to establish themselves on any rivers that ran into the ocean via the St. Lawrence, the St. Louis, or the Mississippi. 24

10 Though Native land claims were not raised during the commission, French officials in Acadia had long relied on their Aboriginal allies’ territorial control to stave off British encroachment. Before the commission officially began, French officials received a memoir from Governor La Jonquière and Intendant Bigot arguing that lands along the western coast of the Bay of Fundy were either French or Native, but certainly not British. 25 Because Native groups were not invited to Paris, the French and British could exaggerate alliances and appropriate lands in ways that did not reflect realities on the ground in Nova Scotia or New France, where Aboriginal groups initiated most territorial discussions and would respond quickly to any over-extension of European power. 26 The Mi’kmaq and their allies might have been willing to share land with the British or French, but they rarely ceded it permanently. 27 This reality of cultural co-existence was ignored at the negotiating table.

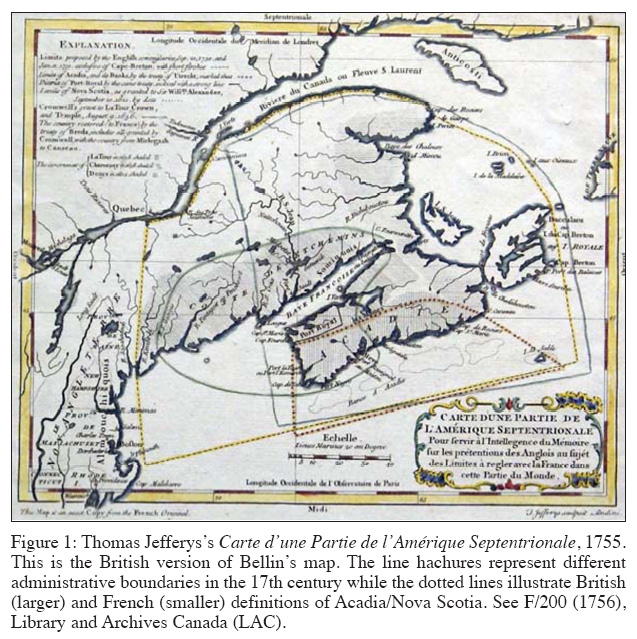

11 The British and French had different interpretations of Acadia’s limits. Silhouette and La Galissonière were instructed that Acadia was only the southern coast of the peninsula (Figure 1), though the French were willing to cede most of the peninsula if the British promised that they would not restrict French navigation in the Gulf of St. Lawrence nor harass French settlements. 28 To that end, La Galissonière and Silhouette maintained a defensive strategy, informing their counterparts that because Britain was the "demandant" it was up to it to define Acadia’s limits; Shirley and Mildmay summarized the French position to Bedford, noting "whatever [Britain] could not prove to belong to us would of course belong to [France], they being in possession." 29 Shirley and Mildmay were consequently sent detailed instructions from the Board of Trade, informing them that Acadia began at the Penobscot River, running straight north to the St. Lawrence, following that river to its gulf, running through the Gut of Canso east to Sable Island, and from there running southwest to the Penobscot. 30

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

12 French officials were unhappy with British claims. When the Marquis de Puyzieulx, the French minister for Foreign Affairs, learned of the contents of the British memoir, he informed the Earl of Albemarle, Britain’s ambassador to France, that the claims "were extended beyond what they had expected; and that his Most Christian Majesty had been much surpris’d at the largeness of the demand." 31 On 21 September 1750 (O.S.), the first written memorials were exchanged. The British memoir defined Acadia’s limits as described above, but the French maintained their more restricted interpretation. 32 The French argument rested on three main points: first, Annapolis Royal (known as Port Royal to the French) was not contained within the ancient limits of Acadia but was ceded separately at Utrecht, an indication that Acadia did not encompass the entire peninsula; second, Canso was situated in the mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and therefore belonged to France, following the French interpretation that islands located in the St. Lawrence were not included in the treaty; and third, the boundaries between New France and New England had not changed since 1713, and should be in 1750 what they were then. 33

13 The memorials provided an opportunity to debate cartography’s ability to define possessions, and maps became embedded in the language of negotiation. Yet each empire found the other’s demands absurd. La Galissonière and Silhouette wrote to Puyzieulx on the day the memorial was received to inform him that "if we give them this, we give them all of Canada, as we won’t be able to support it, nor will we be able to travel to Quebec as soon as they decide to cut off navigation of the river." Although the written memorials facilitated the exchange of ideas and demands, La Galissonière and Silhouette realized that a visual aid would help make each nation’s demands more clear. "We propose to send you a map as soon as possible," they wrote to Puyzieulx, "on which will be marked the British claims to clarify the matter." 34 Puyzieulx remained appalled by Britain’s "monstrous demands" to such a wide swath of land, but reminded his commissaries that they must wait until they received proof from the British commissaries to substantiate the claim. In the meantime, La Galissonière and Silhouette were instructed to prepare a response in which they would emphasize that l’Acadie was only a small part of the peninsula following "the line traced along the map that La Galissonière sent me." 35

14 Maps were necessary to clarify intentions that often became confused in written and oral communications. The British report, of which Shirley was the principal author, arrived in late September 1750. The memoir argued that although the region was called Acadia before it was known as Nova Scotia, the grant from King James I/VI to Sir William Alexander included much of what France called Acadia. From the 1620s to the 1750s the region had changed hands several times, and eventually the two regions became known simply as "Nova Scotia or Acadie." The British did not address the question of competing crowns granting the same land. Shirley continued to argue "that part of Acadie which form’d the territory of Nova Scotia & which we should in this conference call by the name of Nova Scotia proper," to distinguish it from "Nova Scotia or Acadia," comprehended all the lands currently claimed by Britain. 36 In other words, Shirley suggested that Nova Scotia and Acadia were different places. Shirley’s nomenclature annoyed the Board of Trade, who wished to assert that Nova Scotia was Acadia. Semantic gamesmanship was also a tool of the French. La Galissonière responded to Shirley’s explanations by arguing that until the Treaty of Utrecht, the name "Nova Scotia" was a "mot en l’air" which carried no meaning and had not yet begun its existence. 37 The Board of Trade admonished Shirley for raising the question of a separate Nova Scotia and Acadia, leading the Massachusetts governor and his cocommissary to apologize and promise to be more careful in the future. 38

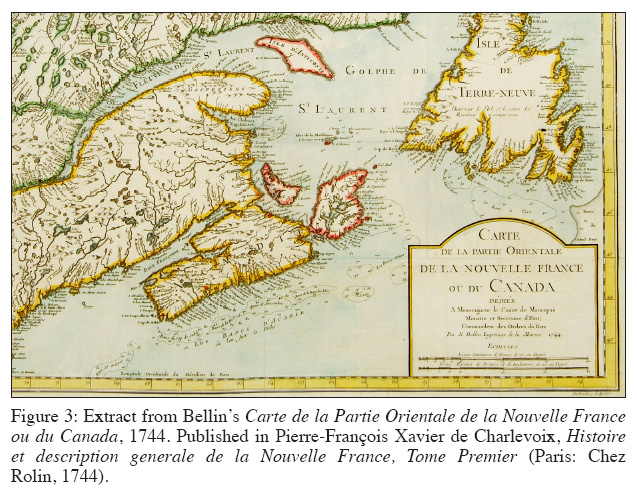

15 With this early misstep behind him, Shirley turned to cartographic evidence as an important instrument in clarifying and countering the French commissaries’ geographic claims. He wrote to Bedford and detailed France’s continued belief that the British had rights only to the southern coast of peninsular Nova Scotia, leaving for France the valuable (and settled) regions of Minas and Chignecto. Shirley believed French maps contradicted these claims, and offered as evidence for the western boundary of Nova Scotia the French geographer Jacques Nicolas Bellin’s 1744 Carte de la Partie Orientale de la Nouvelle France, ou du Canada "in which the lands lying between the River Pentagoet or Penobscot and the River St. Croix, which are not within the limits of Nova Scotia, but parcel of Acadia, are laid down as part of the country of Nova Scotia." Maps also helped counter the French argument that Nova Scotia was but a "mot en l’air". Shirley argued that ancient geographers had engraved the name on their maps in ways that conformed to the British claims established in the Treaty of Utrecht. 39 Despite his best intentions, though, Shirley’s work came to naught. The board crafted its own response and jettisoned evidence, such as Sir William Alexander’s grant, that offered unclear distinctions among the contested territories of New France, Canada, and Acadia. 40 With these evidentiary issues settled and adjusted by the Board of Trade, the British presented their memoir to the French commissaries on 11 January 1751 (OS).

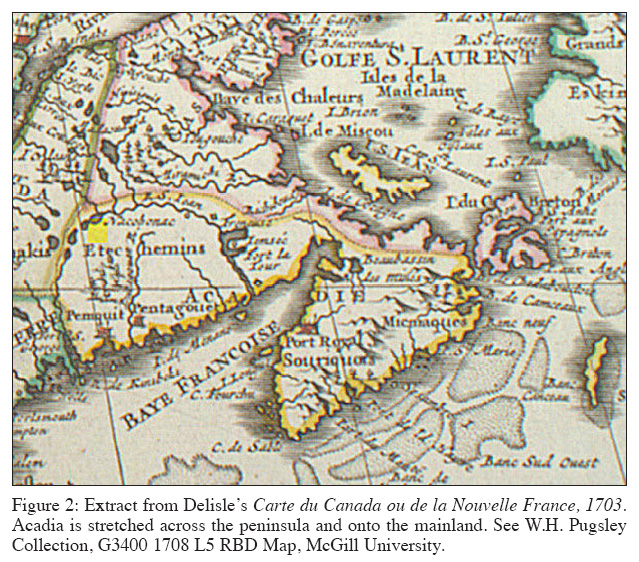

16 British officials depended on maps to counter French arguments, and brought into evidence French maps that challenged the French claim that maps made by all nations limited Acadia to the peninsula (which was a natural territorial division). The board responded that maps "of the best authority are against France in this point." 41 Four French maps were referenced: Guillaume Delisle’s Carte de l’Amérique Septentrionale (1700) and Carte du Canada, ou de la Nouvelle France (1703) (Figure 2); Bellin’s Carte de la Partie Orientale de la Nouvelle France (1744); and Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville’s Carte de l’Amérique Septentrionale (1746). Delisle’s map extended Acadia’s limits to the Pentagoet (Penobscot) River and bound New France to the northern side of the St. Lawrence. 42 Bellin’s maps followed similar boundaries, extending Acadia north towards the St. Lawrence as far as the most northern point of Île St. Jean. The British memoir relied heavily on the fact that these maps were dedicated to, or produced with the support of, the French state. The memoir stressed that Delisle’s map was "informed upon the observations of the Royal Academy of Sciences," and that Delisle himself was the "King’s Geographer" (which was, in fact, a rather meaningless title). 43 The British argued that Bellin’s map was directed by the ministère de la Marine, and that Bellin himself remarked "cette carte est extrêmement diférente de toute ce qui a paru jusqu’ici; je dois ces connoissances aux divers manuscrits du Dépôt de cartes, plans, et journaux de la Marine & aux Mémoires que les R.R.P.P. Jésuites de ce pais m’ont communiqués." 44 Put simply, the British bolstered their claims by emphasizing that leading intellectuals and statesmen had approved these maps.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

17 Yet the British were reluctant to support cartographic evidence without reservations. They returned to the assertion that political authority was something apart from geography, and could be constituted in other ways. Aware of cartography’s limitations, officials demanded that maps be examined alongside other evidence that spoke to territorial sovereignty. The sources from which maps were created should be subjected, in other words, to inquiry to ensure that arguments were based on objective information and not imperial ideology or self-interest. In fact, the memoir proceeded to argue that maps were "slight evidence" and "most uncertain guides." Geographers created maps, and while the memoir did not go so far as to suggest that maps could be created to serve a particular purpose, it did note that cartography was too often based on faulty evidence or repeated mistakes. Even when the maps were geographically accurate – correctly demonstrating the location of rivers, mountains, and settlements – they "can never determine the limits of a territory, which depend entirely upon authentic proof." 45 British officials argued that the proofs used (including treaties, official letters, and state-sponsored surveys) were better evidence than the maps they informed.

18 If lines on a map were ill-suited to define imperial territory, natural geographic formations, according to the British, were no better. Their memoir argued that the French were making different arguments based on different maps. In particular, the British commissaries questioned France’s insistence on natural geography to delineate imperial boundaries, evidenced by the French belief that Acadia could be no more than the peninsula. The British questioned this logic, "as if the rights of the Crown of Great Britain were to be affected by the accidental form and figure of the country." 46 Even if they were, the St. Lawrence was as good a natural division as any other. In the quest to establish territorial sovereignty, maps were investigated as vigorously as other sources. The ease with which the British dismissed natural boundaries suggests that the commissaries could be ambivalent about any evidence that went against their claims. It was the interpretation of evidence, more than its form, that vexed officials.

19 In these first few meetings, geographic knowledge remained suspect yet essential evidence. Maps and surveys were clues to past possession and hinted at feasible arguments regarding the "ancient" limits of Acadia. As windows into the past, maps were attractive sources because they were interpretable and could be used not only to advance arguments but also to counter claims. Though eager to forward the strongest case for Acadia’s limits, British and French officials were not attempting to create new boundaries and therefore did not have to deal with the geopolitical realties in Acadia.

20 Initially, French interpretations of maps and other sources demonstrated a less ambivalent and more nuanced approach to boundaries. La Galissonière delivered to Shirley the French response, all 240 folio pages, on 4 October 1751 (OS). The French commissaries and their superiors had spent nearly 11 months crafting a reply that they believed answered every British argument. They questioned by what right a country could assert territorial sovereignty, claiming that simple discovery did not secure possession. The French memorial worked through the various attempts at English settlement, concluding that the earliest English voyages aimed not to settle land but to discover trade routes. When settlement was attempted after 1585, it failed. England’s first colony in North America, Virginia, was not founded until 1607, and the New England colonies were not truly established until 1630-39. These delayed settlements, according to France’s commissaries, stood in stark contrast to French efforts in the region. Basques, Bretons, and Normans had been fishing the Grand Banks from at least 1504, Jean-Denys de Honfleur published a map of the Newfoundland coast in 1508, and Jacques Cartier took possession of lands around the St. Lawrence in 1535. 47 These actions and their cartographic legacy illustrated France’s historical claims to the region.

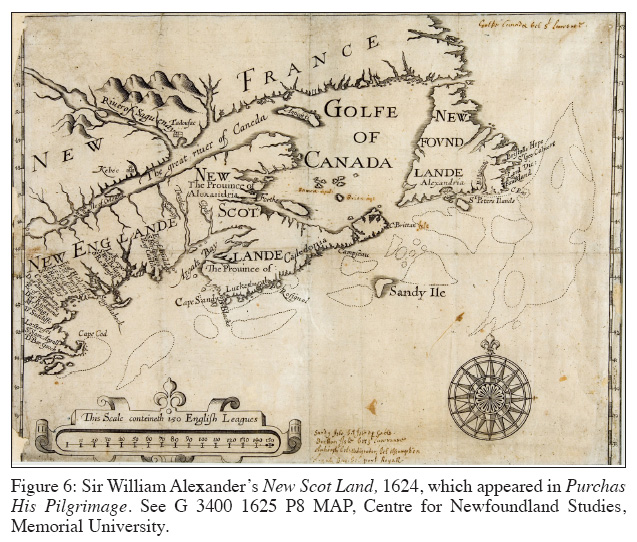

21 An important issue was the British claim to territory previously settled by French subjects. Consequently, the memoir was quick to dismiss the validity of Sir William Alexander’s settlement in (and map of) Nova Scotia largely because France had already established itself on the peninsula and named the region l’Acadie and not "Nouvelle Écosse." The French representatives claimed that both Nova Scotia and Annapolis Royal were terms unknown in France before the Treaty of Utrecht, and the simple act of changing a region’s name did not grant that territory an ancient pedigree. The point was moot, according to La Galissonière and Silhouette, because it was against all human and divine laws to grant territory that was already in the possession of another (Christian) power. 48 The territory included in Alexander’s grant had already been granted by France in 1603 and established in 1604. Therefore, "the concession from James I must be considered null in all respects: and, consequently, the name Nova Scotia, which could only become real by this grant, has never existed; it was a name in the air, that is to say, it has no meaning." 49

22 The French memorial also questioned what qualified as sufficiently "ancient" sources. In the final section, the French turned their attention to the role of cartography and geographic descriptions in imperial affairs and land disputes. The commissaries began with an examination of the maps that the British had employed in their last report. French officials’ analysis of these sources indicates their awareness that maps could be misinterpreted or simply erroneous; cartography’s influence was limited by available information and technologies of production. According to the French, British cartographic evidence did not address the question at hand because the maps were fairly recent, quite different from each other, and supported France’s arguments more than Britain’s. Although the Delisle maps restricted New France to the northern side of the St. Lawrence, the British ignored that these maps extended the word "Canada" over both coasts. New France and Canada were essentially synonymous ("presque synonymes"), and therefore Delisle’s account of the boundaries was contrary to that of the British commissaries. The French recognized that these maps contained elements that supported the British cause (they marked some of Acadia’s territory along the St. Lawrence and into the Etchemin coast), but the maps dated from the early and mid-18th century and this hardly qualified them to account for the "ancient" boundaries sought in the dispute. 50

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

23 The French had an easier time challenging the British reliance on Bellin’s map (Figure 3). According to the commissaries, Bellin was a prominent French geographer (in the employ of the ministère de la Marine and charged with collecting and cataloguing French maps), who had erred by following British geographers. Because Shirley had argued that there existed an Acadia separate from Nova Scotia, the French responded that such a distinction was exactly what Bellin had included on his map, with Nova Scotia running along the coast from New England towards the isthmus. Following the French argument made earlier in the memoir – that Nova Scotia did not exist before 1713 – the commissaries stated simply that the map contained false geographic information. They were reluctant to discount Bellin altogether, though, because he placed Acadia on the peninsula only. D’Anville’s map had similarly followed the errors of other cartographers, but the French commissaries were happy to note that he too confined Acadia to the peninsula. The French suggested that the British were relying on recent maps because there existed no ancient maps to support their claims. Yet even these modern maps failed to depict Nova Scotia’s limits exactly as set by the British. 51

24 Despite the fact that the French commissaries went into detail discussing the weaknesses of British cartographic evidence (which suggests it was worthy of careful investigation), they generally rejected a map’s ability to support land claims and outline political territories. Both the British and the French were frustrated about the lack of detail in extant maps, expressed a shared ambivalence towards cartography as an imperial tool, and were aware of how easily one map could contradict another. Investing maps with political authority was a risky endeavour, as both empires were constricted by the limits of geographic technology. Working within the limits of geographic evidence, both Britain and France preferred at this stage of the dispute to use maps as negative evidence to disprove a point. "It is true that in general," the French commissaries noted,

24 Determining the various ways in which maps attempted to codify geographic language and record boundaries and limits was nearly as troublesome as locating the oldest representation of Acadia.

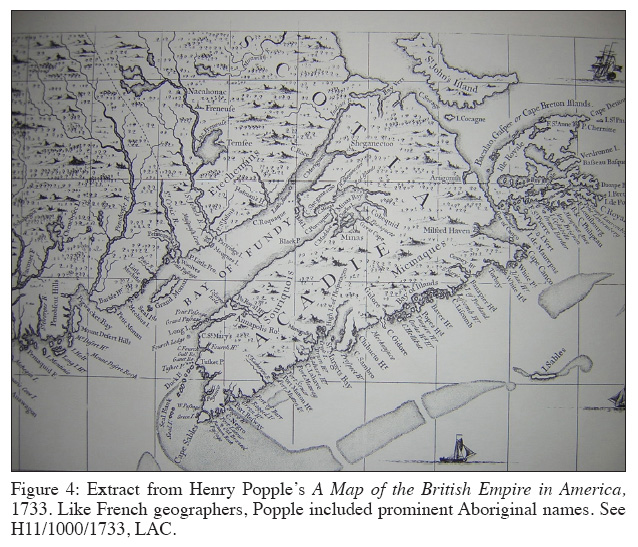

25 The commissaries could not avoid maps and, in fact, British and French officials employed a similar cartographic strategy. Shirley and Mildmay had used French maps to support British claims, so La Galissonière and Silhouette used British maps in their rebuttal. They began with Popple’s map of British possessions in North America (Figure 4). They first established the authority under which this map was produced, noting that Popple had consulted ancient maps and titles, marked royally granted lands better than most geographers, and had received approval (and presumably assistance by way of colonial charts) for his work by the Board of Trade. He limited Acadia to the peninsular coast and "sensibly" marked Minas and Chignecto not as part of Acadia, but as dependencies of the lands claimed as Nova Scotia, and therefore part of New France "because this claimed Nova Scotia was never itself but part of New France." Also important for the French commissaries was the fact that Popple relied more often on names than marked boundaries to delimit territory. The large tract of land between Nova Scotia and New England (much of which was included in the territories being negotiated) was, according to the French, New France. For a British geographer to stamp the territory as French would have troubled his superiors, and so "he could find no better expedient than to leave the region unnamed." 53 The French concluded that although these maps could not be considered wholly accurate, even the most qualified British geographers limited "l’Acadie propre" to the southern peninsula.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

26 Cartography was part of a wider discourse of geographic knowledge and represented historical moments that were recorded in historic texts as well as on maps. The French commissaries’ final argument on the subject of Acadian boundaries demonstrates geographic knowledge as part of larger narrative histories that speak to claims of territorial sovereignty. France argued not from ancient maps, but from the earliest travellers to (and governors of) New France and Acadia. These men made maps and left descriptions. Nicolas Denys was the governor of the land from Canso to Cape Roziers, which he declared was not part of "Acadia." Samuel de Champlain referred to various territories – "Gaspé," "Etchemins Coast," "New France," and "Acadia" – now claimed by Britain under the umbrella title of "Acadia." Marc Lescarbot, who wrote a history of Sieur du Mons’s first Acadian establishment at Île St. Croix (1604), never called the region "Acadia" but instead described it as "New France," "Canada," "Pays des Etchemins," or "Norumbega." The engraving that accompanied this history was entitled "Port-Royal en la Nouvelle France," which the French took as support for their claims. 54 The French evidence was meant to demonstrate not only that British claims to an extended Acadia were incorrect, but also that there existed an established historical record to illustrate Acadia’s restricted limits.

27 The French commissaries also attempted to distinguish how they used maps. They saw their task as not to use maps to create new boundaries, but rather to determine which ancient boundaries were most accurate. Nothing could be taken from geographers who believed that Acadia and Nova Scotia existed separately, because the French had proven that Nova Scotia had never existed at all. The only proof to be drawn from these maps was in respect to the existence of an "Acadie propre," which the best informed geographers placed on the southern peninsula. This general geographic information was perfectly acceptable, but "it is not by maps that we can determine the fixed limits of Acadia." 55 La Galissonière and Silhouette were growing weary of geographic arguments, and Shirley seemed to agree. He suggested that a British reply to the points raised by France (and increasingly considered inviolable in that country) might do some good to the British cause, "tho’ the points may not be likely to be settled between the respective Commissaries, by their memorials and conferences." 56 Even as frustration grew over the lack of progress concerning maps and geographic evidence, the commissaries had little else to go on.

Final efforts and commission stalemate

28 The commission’s progress slowed as time passed, and by 1752 Shirley was recalled. Officially, the negotiations had kept the governor away from Massachusetts for too long, and he was sent back to Boston with the King’s thanks for his efforts. It is also possible that Shirley was removed due to his stubbornness and poor working relationship with Mildmay. 57 Shirley’s removal suggests that Britain wanted to clear any obvious barriers to reaching an agreement. Mildmay was promoted to Shirley’s position and a new commissary – Ruvigne de Cosne – was appointed in 1752. Cosne had worked at the British embassy in Paris as the personal secretary to Lord Albemarle, and had been promoted to first secretary of the embassy in 1751. 58 The British continued to consider maps, and became more invested in their examination of cartography’s role in establishing sovereignty. That neither Britain nor France would dismiss maps out of hand points to geography’s entanglement with other expressions of sovereignty used to envision imperial settlements and shape the way administrators thought about their territories.

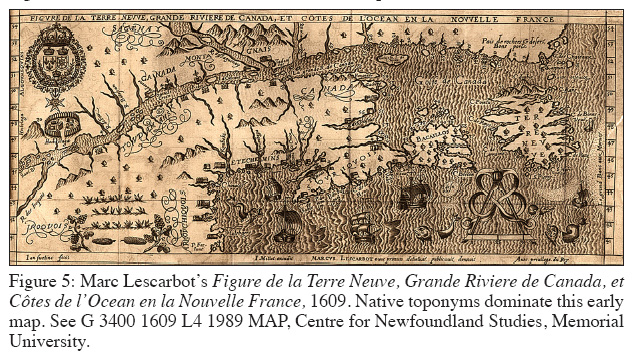

29 The final British investigation into maps makes clear how difficult it was to ignore geographic evidence that supported a claim. Despite their best efforts, the British could not restrict their use of cartography "but to correct the mistakes made by French commissaries." The French had dismissed British cartographic evidence because the maps argued for the limits of Nova Scotia, which French officials did not believe existed before 1713 and because the maps were not sufficiently "ancient." The British response was to revisit the maps France used to support its case. Marc Lescarbot’s 1609 map, which the French had cited, was indeed ancient, published only a year after the founding of Quebec (Figure 5). However, the British argued that "Acadie" was not included on the map, and the rest of the names were "ignorantly placed and assigned." 59 This map was better support for Native land claims, as before there was an Acadia or a Nova Scotia, there was the peninsula that Lescarbot entitled "Souriquois" (who were ancestors of the Mi’kmaq) and the eastern continental coast under the name "Etchemins" (ancestors of, among others, the Maliseet). The British, unlike the French, were in no position to argue that they had a right to Native land (in Nova Scotia) through longstanding alliance. 60 The more cordial relationship that existed between the French and the Mi’kmaq (and their allies) is evidenced in part by the enduring use of terms such as "Etchemin Coast" on maps and in political correspondence. While Popple’s maps used these names, more common was the British practice of renaming Native territory as an act of appropriation. 61

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

30 After challenging ancient French maps, the British returned to using cartography to assert a claim – arguing that that Sir William Alexander’s map (Figure 6) was indisputable proof of Nova Scotia’s extended boundaries because it was the first produced by a geographer who had investigated the region. The map marked "both the boundaries of every territory within it, and the limits of Nova Scotia or Acadia in every particular, contrary to the description of the French commissaries." 62 Because this map appeared so beneficial to the British cause, the commissaries (and, more specifically, the Board of Trade) invested it with political and imperial power by referencing the limits it defined, a pragmatic approach that complicates their earlier claims that maps could not depict political boundaries. Popple’s map, for example, was not considered by the British to be authoritative. Although the French argued that the map was created with the support and approval of the Board of Trade, the British argued that though the board had approved the undertaking it had not supervised its execution. Popple included a marginal note stating the map’s authority, which was a common practice among geographers, but this statement was intended primarily to secure a favourable public reception. He never claimed that the Board of Trade approved of his efforts, and the geographic decisions he made were his alone. 63 In fact, the map itself is inconsistent with the records it claimed to have copied, and "has ever been thought in Great Britain to be a very incorrect map, and has never in any negociation between the two crowns been appealed to by Great Britain, as being correct, or a map of any authority." 64

31 British cartographic ambivalence continued, but administrators nuanced their approach; the commissaries distanced themselves from geographic evidence in favour of treaties, but they could not avoid citing maps. "This is the system upon which we shall argue," the memorial summarized, "in defence of which we shall have no occasion to magnify the authority of maps made in the times of little credibility, or to rely singly upon the inconclusive testimony of the earliest historians of America." This conveniently vague distinction allowed room to "rely singly" on maps produced in times that were considered credible. The treaties referred to by both crowns listed locations, boundaries, rivers, and settlements that existed in London and Paris only as places marked on maps. When the British rebuked France’s argument that Nova Scotia did not exist before 1713, they argued that the name appeared on the best maps from 1625 to 1700 regardless of France’s refusal to refer to the region as such. "Nor indeed is it possible to suppose France not to have had an idea of the country call’d Nova Scotia," argued the British, "after it had been so frequently mentioned in the best maps and histories of America, as Purchas’s Pilgrim, Laet and Champlain." 65 British reliance on Purchas his Pilgrimage to defend their rights to Nova Scotia is not surprising. Samuel Purchas, a 17th-century travel writer, editor, and compiler, was hardly an unbiased source. As David Armitage has argued, Purchas was anti-Catholic and depicted England as a chosen land meant to extend Protestantism across the ocean. 66 The religious undertones to this cartographic evidence served further to differentiate Britain and France, a nationalist theme that, as Linda Colley has demonstrated, continued into the 18th century. 67

32 The commissaries’ efforts to resolve the Acadian boundary question demonstrates how maps and geographic knowledge were used to determine ancient boundaries. Officials’ cautious approach to cartographic evidence illustrates the dangers inherent in asserting sovereignty without material strength. One the one hand, Native territorial strength was marginalized in favour of an imperial view of land control. On the other hand, the ease by which one map could raise doubts about another prevented either side from basing their claims on maps alone. Nor, however, could maps be ignored. If geographic investigation was incapable of determining the most "ancient" Acadian boundaries, perhaps new maps with negotiated borders could solve the conflict.

Direct diplomacy, Acadia, and the Seven Years’ War

33 As the boundary commission faltered and was replaced with direct diplomacy, the use of geographic evidence transitioned from delimiting geopolitical positioning to working proactively to resolve issues on the ground. The process of determining sovereignty from across the Atlantic speaks to the importance of understanding imperial geography as a language of negotiation and a supplement to limited material power and authority. Diplomatic discussions provided British and French officials with a second opportunity to envision their empire in northeastern North America, this time using maps as a tool of creation instead of a lens into past possession. Although Natives were excluded from diplomacy, this second round of negotiations incorporated Aboriginal geography in ways that the commission did not. Diplomats (like mapmakers) could choose how to represent Aboriginal territorial strength: they could marginalize Native regions, emphasize British or French place names, or simply fold Native land into British or French territory. Yet administrators attempting to create new boundaries in Nova Scotia were forced to acknowledge the Native presence, recognizing their de facto geographic dominance. Examining the Aboriginal influence on these discussions helps incorporate the Mi’kmaq and their allies into the imperial conversations that so greatly affected their lives. 68 Diplomatic historian Max Savelle has argued that this second round of negotiations was, at least in part, a stalling tactic that would allow France to strengthen its military in preparation for war. 69 Yet the flurry of exchanges that occurred between 1754 and the late spring of 1755 suggests a genuine interest in avoiding war, or at least limiting the extent of the conflict. As early as 1750, just as the boundary commission was beginning its work, the Duke of Bedford suggested to the Marquis de Mirepoix, the French ambassador to London, that the negotiations be suspended in favour of traditional lines of diplomacy, presumably because he believed direct talks had a better chance of success. Newcastle renewed the proposal in 1752. 70

34 The diplomatic process reveals how cartography was used as an innovative tool to solve problems by creating new maps and setting new boundaries. The task was not to rely on history or judge historical evidence, but rather to use maps to establish new norms for the present. Maps and their use could be adapted to changing times and provide those in positions of power with the information they needed to formulate arguments and render decisions. The diplomatic discussions were under more pressure than the commission negotiations because hostilities had broken out in North America over possession of the Ohio Valley. Both nations professed a desire to avoid war, and therefore continued the diplomacy in an attempt to stave off widespread conflict. Diplomats dealt with three main issues: the possession and extent of Nova Scotia/Acadia, possession of and settlement in the Ohio River valley, and who should control which Caribbean islands. Unlike the commissaries, whose cartographic ambivalence made negotiations difficult, diplomatic discussions illustrate how important maps were to addressing imperial differences. Direct diplomacy crystallized views on territorial sovereignty by creating new boundaries; these discussions enabled British and French officials to define not only Nova Scotia’s geographic limits (as they saw them), but also its strategic position within their respective imperial systems.

35 Nova Scotia’s position in the British and French empires was complicated by the presence of strong Aboriginal groups. Diplomats quickly seized the opportunity to use Native space as a tactical instrument in the zero sum contest for imperial sovereignty. Both British and French officials approached Native territory in three primary ways: it could be claimed through alliances, serve as buffer zones, or was beyond either European power because the land could not be defined. At different times, the officials relied on whatever interpretation best served their empire. 71 The idea of Native buffer zones was first discussed in regards to the Ohio River Valley. At a cabinet meeting, British diplomats suggested removing all forts in the area and "leaving that country a neutral country, where each nation may have liberty to trade; but to be possess’d by the Natives only." 72 Thomas Robinson, who had been appointed secretary of state for the Southern Department in 1754, suggested a similar compromise for Nova Scotia. He wanted for Britain the peninsula together with a tract of land running along the west side of the Bay of Fundy north towards the St. Lawrence and south towards New England. He also maintained "that the rest of the country, from the sd tract of . . . leagues, & by a line, dropped perpendicularly from the river St Laurence, opposite to the mouth of the River Penobscot, be left uninhabited by both the English, or French." 73 This swath of land would have been recognized for what it was: territory inhabited and controlled by members of the Wabanaki confederacy. 74

36 While largely ignored during the boundary commission, Natives influenced diplomatic discussions because they could be used to create buffer zones and act as defensive agents to prevent ceding territory to Britain or France. Mirepoix reported to Antoine Louis Rouillé, the minister of the Marine, that the early meetings with Robinson had gone well. They had discussed the limits of New York, New England, and Acadia. The concept of a Native buffer zone seemed useful, and Robinson had strongly approved of the idea. Yet much of the discussion of geographic boundaries existed at the level of abstraction, and it was necessary for both sides to have an image of what was being surrendered and what was being retained. Mirepoix noted that "after having consulted together, over maps, the regions we had discussed," Robinson stated that he would forward along the proposal and issue a prompt response. 75

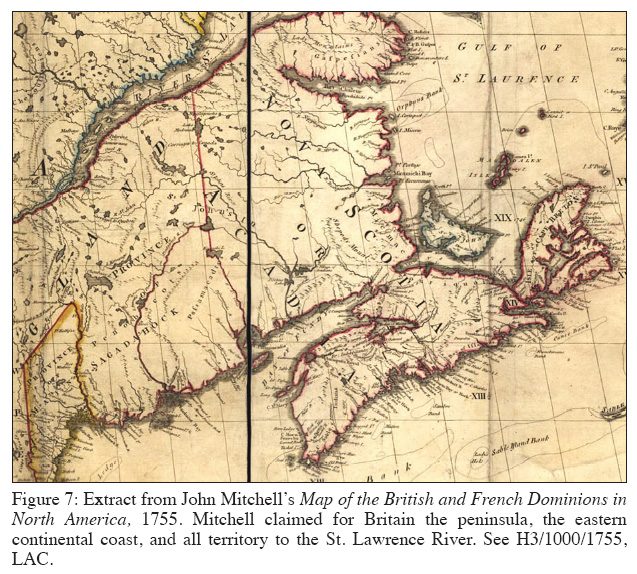

37 Lord Halifax, the president of the Board of Trade, had concerns over reserving land for Natives. To create a Native territory along the Ohio as proposed would surrender much of the settled areas in Pennsylvania. As for Nova Scotia, Robinson’s recommendations were too vague. In a meeting between Robinson and Philip Yorke, the Earl of Hardwicke, Halifax’s critiques were strengthened by a cartographic investigation. The men compared Halifax’s concerns with John Mitchell’s map of North America – which, at that time, was unpublished but overtly pro-British – and confirmed the fact that Pennsylvania and New York would lose territory if part of the Ohio was reserved for Natives (Figure 7). 76 The map also made clear that territorial limits determined by natural land marks – specifically the Appalachian or Allegheny mountains, but presumably also high water marks in Nova Scotia – would yield "a most dangerous & uncertain rule." 77 It would be much preferable to draw a new line than to follow natural markers.

38 Central to the diplomatic discussions was the separation of public and official geographic knowledge. As tensions rose in Europe over fighting in North America, officials attempted to facilitate negotiations by limiting the influence of public imperial sentiment. Hardwicke emphasized the political influence of published maps. Mitchell’s map, if made widely available, could jeopardize any chance of reconciling their differences with France. It would be better to delay the biased publication, for "if it should come out just at this juncture, with the supposed reputation of this author, & the sanction of the Board of Trade, it may fill people’s heads with so strong an opinion of our strict rights, as may tend to obstruct an accommodation." 78 As a tool of geographic knowledge, the map illustrated points made in writing; as a tool of political influence, its very publication could derail imperial negotiations. In this instance, a British official recommended cartographic constraint and prevented the publication of Mitchell’s map for long enough to continue the negotiations without public pressure.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

39 In addition to public opinion, British and French diplomats were forced to evaluate their opinions concerning Native territorial land claims. Rouillé was unconvinced that either Crown could lay claim to Aboriginal territory because it had no definable limits. In reference to the Ohio Valley, he argued that "the American tribes have preserved their liberty and their independence," and "if any Englishman claimed to exercise any authority over this people, the commission with which this court equipped him would not guarantee his life against the danger with which they would threaten it." There were three primary reasons behind Rouillé’s argument: first, the British had never had a governor nor a magistrate in Iroquois territory, so to claim sovereignty over this region was impossible; second, Native tribes changed alliance at their whim, so an ally today could be an enemy tomorrow; and third, Rouillé (wrongly) argued that most Native tribes had no fixed territory, choosing instead to wander from one region to another as they desired or as demanded by the hunt for resources. It was therefore impossible to claim jurisdiction over Aboriginal land because that land was indefinable. 79 By denying the existence of measurable Native territory, Rouillé hoped to prevent the British from using alliances to secure land by proxy.

40 When territory could be measured, it was done so by drawing new lines on maps. While Rouillé questioned Aboriginal land tenure, Mirepoix continued dealing with Robinson and had to visualize what sort of boundaries and buffer zones the British desired to implement in the Ohio River valley and Nova Scotia. In this instance, maps were not only used to make arguments but also to clarify intentions. They had become the very language of negotiation itself. Robinson remained convinced that reserving land for the Mi’kmaq and their allies could satisfy Britain and France. Mirepoix wanted a better idea of what territory would remain unoccupied, and requested maps from Paris. Rouillé informed him that he would send the maps as soon as possible, but warned Mirepoix that the tactics employed by the British did not bode well for resolving the issue. 80 Moreover, when the maps arrived Mirepoix noted that the differences between French and British cartography were so great that neither side could be satisfied with proposed boundaries. Mirepoix informed Rouillé: "You will see clearly by the lines Robinson has drawn just how far the English carry their pretension"; Robinson also warned Mirepoix that while some topics were negotiable, Britain was unwilling to alter its claims to Acadia. 81

41 As diplomacy progressed, it became clear that neither side would relent on Acadia’s limits. The British were suspicious of France’s intentions, especially the French refusal to accept larger boundaries for Nova Scotia in return for consideration in other regions. 82 Robinson wrote the British minister to Spain expressing his worries, noting that Rouillé did "not intend to leave to His Majesty’s subjects the quiet possession of even half of the peninsula," which, far from inspiring British officials to back down, had caused even more alarm in London and in North America. As Robinson reported, Rouillé argued that Robinson’s insistence on a Native buffer zone would create a territory devoid of laws (assuming, as he apparently did, that the Aboriginals were lawless), and ignored that Natives had "neither limits nor boundaries and change their habitations according to their caprice." Robinson recorded that Rouillé argued that "each nation possesses more than she can use for a long time to come." 83 Too much land was as problematic as too little, and according to Rouillé it would be better for each to secure what it had instead of acquiring more.

42 For the British, Acadia remained the key to negotiations. Officials hoped that vague promises of concessions would reassure the French and hasten the charting of new boundaries on fresh maps. Mirepoix reported to Rouillé that "as to the article for the Ohio, [Newcastle] repeated to me that it was much less important to them than that for Acadia." According to Mirepoix, Newcastle stressed that "we have not the islands so much at heart as Acadia. If your court will consent to give us satisfaction on the peninsula and the Bay of Fundy, we will find means to give it to them on the islands." Newcastle reassured the French ambassador that Britain had no desire to settle near the St. Lawrence if it would make the French colonies uneasy or disrupt their navigation. 84 Robinson later reported to Newcastle that Mirepoix had agreed in principle to Britain’s demands for Nova Scotia, but was curious what they would surrender in return. To avoid providing the French with specifics, Robinson had pressed on about how to divide Nova Scotia and New France, to which Mirepoix suggested creating a Native buffer zone like the one that France had rejected in the Ohio. While Mirepoix could speak only hypothetically, Robinson reported that Mirepoix believed a dividing line could be drawn towards the St. Lawrence, but bent in such a way "so as to fall upon a point over against Quebec," leaving a communication link from Quebec to Île St Jean, "and that each side of the said line of communication should be left to the natives with a prohibition to either French or English to make forts . . . or even to trade." 85 Robinson hoped that this strip of land, left neutral, would satisfy the French desire to keep their territories along the St. Lawrence safe.

43 In negotiations over Acadian sovereignty, abstract promises of territorial concessions elsewhere were coupled with concrete suggestions for new boundaries in the northeast. Yet British willingness to acquiesce in the Ohio River valley and the Caribbean islands did not alleviate France’s concerns about Nova Scotia’s extended limits. Mirepoix reported Britain’s final demands: the entire peninsula, a swath of land twenty leagues wide along the western coast of the Bay of Fundy, and that a line be fixed from the mouth of the Penobscot running north towards the St. Lawrence, then turning east and running parallel along that river at a distance "as we [the French] shall propose." 86 This proposal was met tepidly, yet there was one last effort made to avoid war. Lord Granville hinted to Mirepoix that the British would be willing to surrender St. Lucia, but the Acadian boundary remained a divisive issue. He emphasized to Mirepoix that they would not desist on the land running from the isthmus to the Penobscot, but the French ambassador reported that on "this last object I still think we might perhaps get them to consent that the whole coast be forbidden as we propose for the northern coast of the peninsula; but they will not accord us possession of it." 87 This proposition would have reserved even more land for the Mi’kmaq and their allies, officially recognizing their territorial sovereignty. Britain’s answer to this proposal highlighted British views on Native territory and property. The memoir stated that Native land was well known and that Natives "hold and transfer [their lands] like other proprietaries everywhere." 88 Far from being transient inhabitants with indefinable territory (as Rouillé had suggested), Natives were possessors of territory and could do with that land as they saw fit. According to British officials, this meant that when the Natives became British subjects, as they believed they had, their land became British land. This argument was difficult to apply to Nova Scotia. The Treaty of Utrecht had not sufficiently addressed the question of Native alliances. The Mi’kmaq remained largely independent from the British and their sovereignty had been tacitly recognized when the British entered into treaties of peace and friendship. 89 In the end, there could be no agreement as both sides held such divergent views of the Acadian boundary. Negotiating sovereignty through diplomacy required the ability to innovate and compromise. Military power and settlers were in short supply in Acadia, so officials turned to maps and geography in an attempt to avoid another armed conflict. Ultimately, diplomacy failed to preserve the peace. However, after numerous rounds of cartographic negotiations, an important element in determining sovereignty was resolved: Britain had charted its Nova Scotia and France had found Acadia.

Conclusion

44 Determining the Acadian boundary was an exercise in territorial negotiation, and geographic knowledge was an important element in asserting and combating land claims. Maps served political and ideological purposes – outlining past possessions and projecting an image of future sovereignty. Even after the founding of Halifax in 1749, the British in Nova Scotia were militarily vulnerable to attacks from Native groups and legally weak in the face of entrenched Acadian customs. France was equally incapable of marshalling enough military power to recapture Acadia, and the Acadians were too removed from French authority and enmeshed in informal Native alliances to represent France’s claims in the region. The inability to exercise material power in this part of northeastern North America forced the British and French governments to turn to commissions, diplomats, and cartography. This two-step process witnessed a transition in the use of geography as an imperial tool: the commission relied on maps to determine ancient limits, while diplomats created new geographic boundaries to resolve problems on the ground. The appointed commissaries failed in their assigned task of determining, inter alia, the "ancient" boundaries of Acadia, which they looked for on old charts. Their reports demonstrate a cartographic ambivalence in the face of maps and geographic evidence. Yet they were unable to dismiss maps outright; instead, they used them frequently to dismiss competing assertions and cautiously to make claims. Diplomatic discussions, on the other hand, revealed how maps could be used proactively to create new boundaries. Cartography became embedded in the language of negotiations – clarifying intentions and illustrating suggestions. These diplomatic discussions were also forced to deal with Aboriginal territory; although the Mi’kmaq and their allies were excluded from negotiations, their territorial authority influenced attempts to create new boundaries that might include Native space. The boundary negotiations and the diplomatic discussions reveal the connections between Nova Scotia/Acadia’s strategic position in the British and French imperial system and cartography’s importance to assertions of imperial authority. To France, l’Acadie was an Atlantic outpost that could help protect Canada; to Britain, Nova Scotia was the crux of the continent. Both imperial powers relied on extant maps to inform their perceptions of past possession, and both used geographic information to create new boundaries in the hopes of preventing a major war. As the British and French empires grew or adjusted after the Seven Years’ War, both drew from the lessons learned in the Acadian boundary negotiations.