Articles

Africville and the Dynamics of State Power in Postwar Canada

Tina LooUniversity of British Columbia

Abstract

This article examines the program of urban renewal undertaken by the City of Halifax in the mid-1960s that resulted in the destruction of the African Canadian neighbourhood of Africville. Focusing on how the relocation was carried out gives us a very different view of the workings of the postwar state – specifically, of the contingencies of power and the complexities of its exercise. Africville is important not just as an example of racism, but for what it reveals about the dynamics of state power and the meanings of the good life embedded in the welfare state.Résumé

Cet article examine le programme de rénovation urbaine mis en œuvre par la Ville de Halifax au milieu des années 1960, qui a conduit à la destruction du quartier d’Africville, habité par des Afro Canadiens. En mettant l’accent sur la façon dont ses habitants ont été relocalisés, cet article nous donne un aperçu très différent du fonctionnement de l’État dans l’après-guerre, plus précisément des contingences du pouvoir et de la complexité de son exercice. Le cas d’Africville est important non seulement comme exemple de racisme, mais aussi pour ce qu’il révèle au sujet de la dynamique du pouvoir de l’État et de ce que signifie la qualité de vie coulée dans le moule de l’État providence.1 IS THERE ANYTHING MORE TO SAY ABOUT AFRICVILLE? The very word resonates, suggesting the familiarity people have with the place and its history. As many Canadians know, Africville was an almost entirely black community located at the north end of Halifax fronting the Bedford Basin. Established in the 1840s, it was razed in the mid-1960s and its residents – then numbering about 400 – were relocated by the city as part of a redevelopment plan designed by Gordon Stephenson (a student of the high modernist architect Le Corbusier). Perhaps stung by Stephenson’s observation that Africville "stands as an indictment of society and not of its inhabitants," municipal authorities used relocation to rid Halifax of one of its "blighted" areas and to try to improve the lives of its residents.1

2 Like many postwar schemes to improve the human condition, urban renewal in Halifax fell short of delivering on its promises. The residents of Africville were certainly removed and the "slum" cleared, but the hoped-for integration and uplift were not entirely achieved. There were those who were glad to have left their old neighbourhood behind – Africvillers who believed their lives and their children’s were much improved by the relocation. But others continued to suffer from insecure and inadequate housing. Moving from one marginal rental to another, they became urban nomads in an often unforgiving and unfamiliar environment. Some found themselves on welfare for the first time, unable to find a job that would pay the monthly rent – a new experience for those used to the more informal economies that governed life in Africville. Still others discovered the difference between good housing and a good life. For all its physical privations, life in Africville had afforded them privacy, freedom, and community.

3 As was the case with other forced relocations, the resettlement of Africville inspired a vibrant popular culture of loss and regeneration.2 Thanks to writers, poets, musicians, filmmakers, and former residents, Africville has become a place both lost and found. Their work highlights the solidarity, self-help, creativity, and resilience of its residents. In doing so it remaps the settlement, asserting a new cartography of community that rejects the dominant view of the neighbourhood as a slum and its inhabitants as downtrodden, dissolute, and violent. The Africville that emerges is rural, "your typical seaside village" inhabited by "folk" of a different yet familiar kind.3 Relocation destroyed the fabric of community, ending an idyllic age of innocence at Bedford Basin. "What was lost was invisible to those ‘well-meaning’ bureaucrats because they never lived in Africville," reflects jazz musician Joe Sealy. "They never chased baseballs across the field on cool summer evenings, or scrambled for blueberries in the scrub on the hill, as the children did. They never heard the piano music from the parlours or the voices raised in praise from the church. They never knew what it was like to be six years old, living in Africville and knowing you’re safe because you’re home."4

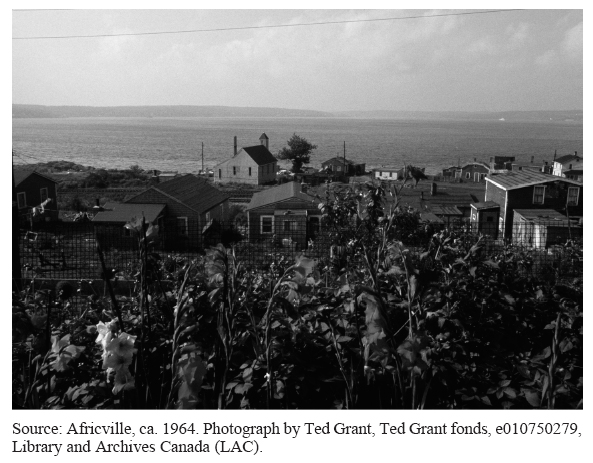

4 The emphasis on the unseen beauty of Africville is also apparent in Shelagh Mackenzie’s powerful documentary, Remember Africville. In a pivotal moment in the film, black educator and lawyer Gus Wedderburn, who had supported the relocation, admits that his position at the time was based on an incomplete understanding of Africville. Listening to residents talk about the rich and fulfilling lives they had led and what they had lost in the relocation made him realize he had not understood the place fully. Holding up a photograph of the community, he says, "I did not see the flowers . . . I did not see the flowers."5

Display large image of Figure 1

5 Through the efforts of artists like Sealy and Mackenzie, among many others, Africville has been rebuilt. As poet and literary critic George Elliott Clarke argues, their "re-membering of a dis-membered community" constructed a new, more politicized identity that helped mobilize Black Nova Scotians as "Africadians." The injunction to "Remember Africville!" echoes "Je me souviens"; it also means not to let such a thing happen again – to combat the racism that the relocation exemplified and to overcome the differences that prevented unified action.6

6 While Africville has been the focus of a great number of artistic works that themselves have become the subject of academic inquiry, the history of the relocation has received somewhat less attention from scholars.7 For those who have examined it, Africville exemplifies the violent power of racism. To Howard McCurdy, for example, the concentration of noxious industrial development in and around Africville over the 19th and 20th centuries, combined with the city’s neglect in providing other infrastructure like sewers and safe water, makes Africville a textbook case of environmental racism.8 Race and space are also at the heart of Jennifer J. Nelson’s work. For Nelson, the razing of Africville and the displacement of its residents was the outcome of a process of racialization that saw the social become the spatial. She argues that the Africville that was bulldozed was the creation of Halifax’s white community. In newspapers and in the pronouncements of municipal civil servants, it was portrayed as a dangerous black slum meriting surveillance, abandonment, and, ultimately, demolition. Not only was defining Africville as a wasteland necessary in order to obliterate it, but doing so was also central to maintaining white identity. For Nelson, Africville’s destruction was a signal moment in nation-building.9

7 If there is more to say about Africville, perhaps it can come from changing the focal point of inquiry. My intervention does not so much take on the existing interpretations as it asks different questions. Mine is another story, both smaller and larger than the one that has been told. It is smaller in the sense that it is historical, attentive to the other contexts in which urban renewal occurred. As much as Africville and its relocation were the outcome of longstanding racism, the decision to raze the community was also a manifestation of a set of ideas characteristic of a particular historical moment. Relocation was an outcome of the progressive politics of the late 1950s and early 1960s and the solutions they offered to inequality.

8 It is also smaller in its attentiveness to the ground, if not Wedderburn’s flowers. Thanks to the access I obtained to the municipal records relating to Africville and the research materials that were collected for the 1971 Africville Relocation Report carried out by Donald H. Clairmont and Dennis W. Magill, I was able to map the physical and social geography of Africville and follow the route taken by some individual residents and the city in reaching agreements for compensation.10

9 In that sense, what follows is also an exercise in cartography, and one that engages questions of legibility. In Seeing Like a State, anthropologist James C. Scott argues that systematic state interventions like urban renewal are premised on making the objects of intervention visible, or legible, first. Indeed, much of modern statecraft is taken up with standardizing measurement, collecting vital statistics, and instituting a national census and system of taxation – all projects that constituted populations or property as units of administration.11

10 In Halifax, implementing urban renewal was hindered by a lack of clarity surrounding property ownership. To the municipal state Africville was illegible, and the only way it could make sense of it was to rely on those practiced in the paleography of place: its residents. Without local knowledge to clarify ownership, Africville’s relocation would not have proceeded as the city planned. But involving residents had important consequences. Getting local knowledge took time: it took lots of meetings to establish a working relationship between the city and each resident before discussions about compensation could even begin – and discussions demanded yet more time. While Nelson argues there was only a "pretence of consultation," analyzing the process of relocation suggests there was much more discussion between the city and residents than she acknowledges.12

11 Moreover, the necessity of local knowledge meant that the exercise of state power was entangled in a thicket of local rivalries, jealousies, fears, obligations, and friendships that resist easy analysis. On the ground, relocation ceased to be an abstract matter of "spatial management" aimed at the "containment" of areas of "troubling blackness."13 Instead, the process of negotiating compensation reveals how contingent and subtle state power could be. In addition to giving us insights into its dynamics, these negotiations allow us to understand something of the amplitude, tone, and timbre of that power – of how it was experienced by those who exercised it and those over whom it was exercised.

12 The Africville relocation also sheds light on some of the tensions inherent in the liberal welfare state, and it is in this regard that the story I tell is larger. While current scholarship frames Africville in terms of racism, for officials of the City of Halifax, and the liberal-minded more generally, Africville was a "welfare problem" – one that required them to figure out ways to meet the multiple and concrete needs of its residents. Racism might have been the reason Africvillers were disadvantaged and immobilized both socially and spatially, but the solutions liberals offered were aimed at meeting Africvillers’ needs – for education, employment, adequate housing, and access to capital – rather than eliminating racial prejudice directly. The first step towards doing so was to move Africvillers out of their ghetto and physically integrate them into the city. As Africvillers discovered, however, integration was not belonging. In laying bare the gulf between the two, Africville shows us both the possibilities and the limits of the liberal welfare state to create the good life.

Making Progress

13 To many people Africville was appalling not only because of its substandard housing, lack of sewers, and contaminated water, but also because it was a ghetto. The physical segregation and poverty of the black Haligonians who lived there were manifestations of the kind of deep-seated racism that was increasingly under attack in the North America of the late1950s and the early to mid-1960s. As Time (Canadian edition) magazine put it in 1970: "The bulldozing of Africville exemplifies a determined, if belated, effort by the municipal and provincial government to right an historical injustice."14

14 Razing Africville and integrating the people who lived there defined progressive politics and social action at the time: it was a way to fight discrimination and to articulate and defend human rights; indeed, it was progress. But it was not the only manifestation of progressive politics and social action; the wave of urban renewal that swept Africville away was part of a larger one that hit North American cities in the postwar period, and part of a broader liberal moment in the province. Singled out for its racism by one social scientist in 1949, Nova Scotia took important legislative steps towards equality during the 1950s and early 1960s, dropping a clause in its education act that sanctioned segregated schools for blacks and passing laws regarding fair employment and accommodation practices as well as its first human rights act.15 At the same time, the province also succeeded in modernizing its system of social welfare, finally replacing the poor law – which had not been significantly revised since 1879 – with social assistance acts in 1956 and 1958.16

15 In this context of reform, the Stephenson plan enjoyed broad support. Not only did it appeal to those interested in racial equality, who saw it as the next logical step in improving the lives of the city’s poorest residents, but it was also backed by the members of Halifax’s financial and business communities who were keen to see it become a modern and prosperous port city.17 Urban renewal and relocation would result in both better housing and an end to segregation. The alliance of progressives forged around Africville brought together blacks and whites; it included representatives from labour, business, and the churches; and it engaged politicians, planners, and social workers as well as some residents of the community itself.

16 At the same time the Stephenson report was issued, organized labour was at work in Nova Scotia to bring incidents of discrimination to light. In 1957, Sid Blum of the Jewish Labour Committee travelled to the province, interviewing blacks about their experience with discrimination and recording their views about what life in Nova Scotia’s towns and cities was like.18 There clearly was a problem with discrimination in the province; according to Maclean’s magazine, Halifax was the eastern front of Canada’s war for civil liberties – "the last frontier for the professional do-gooder."19 But while Nova Scotia might have been a "model of race relations" in terms of its legislation, there was still much room for improvement on the ground.20 As Sid Blum discovered, Halifax was the place where black women who graduated from secretarial school discovered that promises of employment made over the telephone evaporated when they turned up in person; where white barbers refused to cut black men’s hair; and where a realtor could tell a middle class, black Baptist minister and his wife that the price on the house they were looking at had increased by 50 per cent when they expressed an interest in buying it.21

17 So when Blum received a visit and letter from some Africville residents four years later in 1961 expressing frustration and concern about their housing situation and the possibility they would be forcibly relocated, he likely was not surprised and he certainly had a context in which to place their request for assistance.22 In response, Blum told them he would send "our best man in this field" to help. Although he had no specific course of action to recommend, 30-year-old lawyer Alan Borovoy felt the residents had to make a deal with the city.23 To put them "in a position where they had some strength and would not be screwed," he convened a meeting of civil rights organizations at the Nova Scotian Hotel in August 1962 as a first step towards building a broad-based progressive coalition that would fight the good fight, which in his view was one aimed at integrating Africville rather than continuing its segregation.24

18 The coalition that emerged from the meeting at the Nova Scotian would come to be known as the Halifax Human Rights Advisory Committee (HHRAC), a group that played a key role in the relocation process by overseeing the compensation agreements struck between Africville residents and the city. Although it had a membership of thirty-one, its core consisted of ten people: three were Africville residents, who had organized themselves into a "Ratepayers Association" following the meeting with Borovoy, and the others – three blacks and four whites – were not.25 The latter were middle class outsiders who came to civil liberties work through the faith communities they belonged to, their commitment to education or, in the case of some, a combination of both.

19 For instance, HHRAC members Charles Coleman and W.P. Oliver were both ministers at Cornwallis Street, the "mother church" of the African United Baptist Association. The American-born Coleman was also pastor at Seaview Baptist, Africville’s church, and his views on human rights were shaped by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and its first president, Martin Luther King, Jr. His experience in Harlem had also left its imprint, making him more militant than other Black Nova Scotians, and certainly more so than his clerical counterpart, W.P. Oliver.26 Oliver, who had been criticized by Sid Blum for his "apologetic" stance on racism, was nevertheless a pioneer in the movement for racial equality in the province.27 In 1945, he founded the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People, an organization he considered the "secular arm of the church," and which, among other things, had taken on the cause of Viola Desmond, "Canada’s Rosa Parks."28

20 By 1963 this association was headed by educator H.A.J. "Gus" Wedderburn, who also served as the HHRAC’s chair and who recruited lawyer George Davis to the cause.29 At the time of Borovoy’s visit to Halifax, Wedderburn was involved with another civil rights organization, the Inter-racial Council, which was represented at the Nova Scotian Hotel by Fran Maclean. Prior to joining the HHRAC, Maclean had worked towards improving educational opportunities for black students by tutoring youth through her work with the Voice of Women.30 Her husband, Donald, was the HHRAC’s secretary. Like Fran, he was active in the Inter-racial Council, among many other organizations, and shared her commitment to education. Donald Maclean worked for the province’s Adult Education Division before taking a job as the assistant director of Dalhousie University’s Institute of Public Affairs. Officials at this institute viewed human rights as an "integral part" of the organization’s mandate, and they carried out many of the socioeconomic studies that revealed the extent and impact of racial discrimination in Nova Scotia.31

21 The Macleans’ interest in education, as well as Oliver’s interest in an activist church, was shared by Lloyd R. Shaw, another key member of the HHRAC. A successful businessman and lifelong democratic socialist, Shaw encouraged such progressive practices as profit-sharing and employee ownership, promoted corporate responsibility, and was actively involved in a range of social issues (including housing, health care, and unemployment).32 His interest in social reform generally and in Africville specifically grew from his Baptist faith. First Baptist, his church, ran a two-week long Bible school every summer for 50 to 60 children from Africville. The experience convinced many members of First Baptist of the need to broaden their involvement, shifting from delivering a service to helping community members lobby the municipal government for more.33

22 For these members of the HHRAC, integration and improved living conditions and opportunities were the prime motives for becoming involved with Africville. Shaw, for instance, "didn’t feel that any group of people should be living anywhere in that kind of condition," a sentiment that Gus Wedderburn agreed with. Wedderburn’s motives were also "personal. Deep down inside I felt that members of my race were being treated unfairly," he recalled.34 Wedderburn was also influenced by adverse publicity about Africville: "I heard stories about Africville . . . . It was sometime around Christmas when we picked up a newspaper. In it was the story of a family in Africville that had been burning old car batteries which had been scavenged on the dump to keep them warm and, as a result of burning those batteries, the family was lead poisoned and had to be taken to the hospital. I asked myself the question, God, what is this? What is this? . . . . As a result, when I was invited to attend a meeting dealing with Africville and the decision of the city fathers of Halifax to remove the residents of Africville, I figured I had to be there."35

23 According to George Davis, the goal of the Halifax Human Rights Advisory Committee was integration. He and his colleagues felt "it would be an advantage to the coming generation to be placed in a position where they would not be a separate community but part of a larger community in which they would be competing as far as work, education, and housing were concerned." For Fran Maclean such opportunities constituted "having rights to be a full citizen," something necessary for "the development of the latent talents of all people."36

24 The involvement of people like Oliver, Coleman, Wedderburn, Davis, the Macleans, and Shaw connected Africville to different networks of power: to people in the municipal and provincial governments and in business, to the university, to the national community of planners, and the international world of human rights. These links raised the profile of Africville, and guaranteed the issues raised by members of the Halifax Human Rights Advisory Committee would get a hearing. When the well-connected Shaw, for instance, together with his HHRAC colleagues Gus Wedderburn and Charles Coleman, met with Alderman Allan O’Brien to suggest that it would be useful if the city had the advice of a housing expert in coming to a decision about Africville, they were taken seriously and their recommendation implemented.37 In 1963 the city retained Albert Rose, a professor of social work at the University of Toronto and architect of Canada’s first and largest social housing project, Regent Park, which had been completed in 1957. Shaw and Rose were familiar with each other, both being members of the Community Planning Association of Canada.38 Rose’s philosophy of social housing likely resonated with the members of the Halifax Human Rights Advisory Committee as a whole: he believed the key to healthy housing lay in planned diversity. Regent Park’s success was rooted in the range of ages and incomes of its tenants. For Rose, diversity was the bedrock of community. Integrating different populations was what made a place like Regent Park work, and work better than the other major housing trend of the 1950s: the ubiquitous suburb.39

25 While forming a coalition with civil liberties advocates strengthened the position of Africville’s residents as Borovoy argued it would, doing so did not guarantee their wishes would be heeded. Both they and the members of the Halifax Human Rights Advisory Committee – some of whose members lived in Africville – agreed that there was a housing problem in Africville and that it would be useful for the city to have expert advice. But in recommending Albert Rose, a proponent of integration, the committee narrowed down the possible futures for Africville to one: relocation. Despite the fact that many residents had made it clear they did not want to leave Africville, Rose told them it was in society’s (and their) best interests to do so and to integrate themselves with the rest of the city.40 Overwhelmed and devastated by the conditions Africvillers lived in, he addressed a meeting of residents and the members of the Halifax Human Rights Advisory Committee: "Can a modern urban metropolis tolerate within its midst a community or grouping of dwellings that are physically and socially inadequate, not served with pure water and sewage disposal facilities?" he asked. "Can a minority group be permitted to reconstitute itself as a segregated community at a time in our history, at a time in the social history of western industrialized urban nations, when segregation either de jure (in law) or de facto (in fact) is almost everywhere condemned?"41 For Rose, as for all the progressives involved with Africville, the answer was "no."

26 At a time when the civil rights movement in the United States was working to end segregation – particularly residential segregation – as well as fighting for multiracial public housing, people like Rose and the members of the Halifax Human Rights Advisory Committee just could not understand the desire on the part of some of Africville’s residents to rehabilitate their neighbourhood or to be moved to their own public housing facility. Nor could city officials. As Maclean’s reported in 1965, Halifax’s aldermen and bureaucrats were "thunderstruck" when "suspicion" rather than "gratitude" greeted the city’s decision to finally end years of neglecting its responsibility for Africville by razing the community and relocating its residents. The rhetoric of racial equality, not to mention the race riots that had begun to shake American cities, had clearly not prepared them for encountering a "Black ghetto that fears integration."42

27 The extent to which both progressives and city officials were open to treating Africville differently was a direct result of their acknowledgement of its "unique" past: settled for over a century, Africville had endured a history of longstanding municipal neglect and poverty. Given these special circumstances, city officials were reluctant to simply impose the law. Although tearing down Africville’s substandard buildings and expropriating the land was appealing in terms of economics and efficiency, and the fastest and cheapest way to initiate the redevelopment of the area, R.B. Grant, the director the Halifax’s Development Department, advised against such an approach in 1962. While expenditures would be kept to the "absolute minimum," applying the letter of the law would be costly both to the city’s reputation and the lives of the residents of Africville. Instead, the city needed to "temper justice with compassion in matters of compensation and assistance to families affected." Despite the risk of setting "unfortunate precedents," Grant insisted the course of action he outlined was justified in the "interests of history and fair treatment to [Africville’s] residents."43

28 The Development Department’s arguments for treating Africville differently were echoed by Albert Rose just over a year later. Although his report advised the city to act quickly to relocate and rehouse Africville’s residents, Rose also urged municipal authorities to recognize the community’s "unique" situation, one that required a comprehensive approach to resettlement. Africville was "far more than a housing problem": it was "a welfare problem . . . a multidimensional task" of a scale no government had dealt with before. There was a lot at stake in relocating the community’s residents: for the first time in 25 years of slum clearance, public housing, and redevelopment activity, "the removal of a severely blighted area will take away from a large proportion of the residents, not merely their housing and their sense of community, but their employment and means of livelihood as well . . . ."44 City officials would have to plan carefully.

29 Rose’s report was approved at a meeting of Africville residents in early January 1964, and by the city council shortly afterwards.45 In deciding to negotiate rather than expropriate, and to treat relocation as a welfare issue rather than simply a housing issue, city officials acted in accordance with a notion of natural justice that stemmed from their recognition of Africville’s history and the city’s own role in creating the problems that plagued its residents. Formal expropriation proceedings worked against the interests of property holders: they were expensive, they put the onus on them to prove title, and they kept compensation within narrowly defined limits. Negotiations allowed for greater latitude. Acknowledging the welfare dimensions of relocation, city officials also agreed to assist with rehousing Africville residents and develop employment and education programs that would improve their economic and social prospects.

30 The decision to acknowledge and act on the community’s differences in this way shaped the exercise of power and reveals much about the character of the welfare state and the character of Africville.

Groundwork

31 Implementing the relocation fell to one man, 40-year-old Peter MacDonald, a provincial social worker seconded to the city to deal with the Africville file.46 That a single individual was given the responsibility for relocating 400 people in just 20 months is indicative of the character of the welfare state at the municipal level: its power was neither anonymous nor, it seems, particularly extensive. This was not simply a matter of economy, but also of humanity: relying on one individual to be the face of the relocation program reflected a belief held by city officials that "personal contact" was a key part of planned social change. MacDonald "was not somebody sitting behind a desk, or some distance away, he was a person you probably had in your home, had tea with, discussed matters with them," said Director of Development Robert Grant. "I think this was the essential element in making the thing go."47 If we can refer at all to "technologies of oppression and regulation" operating in the Africville relocation, as Jennifer Nelson does, we need to bear in mind that they were a little like the Great and Powerful Oz, manipulated by a single, over-extended social worker working against an impossible deadline.48

32 If the machinery of power that characterized the welfare state in Halifax was not particularly robust, the context in which it worked made MacDonald’s task all the more daunting. Like many of residents of Halifax, and like many of the members of the Halifax Human Rights Advisory Council, MacDonald was not especially familiar with Africville’s residents or with how the place operated as a community before he was assigned the relocation file. Initially, his lack of knowledge was an obstacle to doing his job, but an even greater hurdle was the confusion surrounding land tenure.

33 Africville was almost completely illegible to the state. The city had agreed to compensate property holders at "full market value," but as it acknowledged, and as MacDonald soon learned, doing so was no easy task. It was difficult, if not impossible to ascertain from city records who owned the lands on which Africville residents lived. In planning for Africville’s relocation, staff at the city’s Development Department searched the original land grants back to 1750s. Unfortunately, after 1795 the records became "vague."49 While an 1878 city atlas indicated that about 80 per cent of the land in Africville was owned by the city, the volume had no legal standing. Some clarification of title in the area came with the Canadian National Railway expropriations in the early 20th century, and with the expropriations for Halifax’s "Industrial Mile" in 1957.50 With regard to the latter, however, it soon became apparent that the residents whose properties had been expropriated in 1957 had never been informed of that fact, probably because the "Industrial Mile" never materialized.51 They had no idea they did not still possess the properties they lived on. Given its failure to inform them, the city agreed that it would proceed as if the 1957 expropriations had never taken place.52

34 City neglect also meant its tax rolls were no help in clarifying property ownership. Africville properties were not assessed regularly or at all until after 1956. Even then, because of the uncertainty around title, the city only evaluated the worth of the buildings.53 In all, only 14 of the community’s nearly 400 residents had registered deeds for their properties. Useful as they were in clarifying ownership, many of the deeds were not as helpful as they might have been. At least 11 had been "plotted in the most imprecise manner" and, in two cases, the boundaries were so poorly drawn that it was "impossible" to locate the property.54

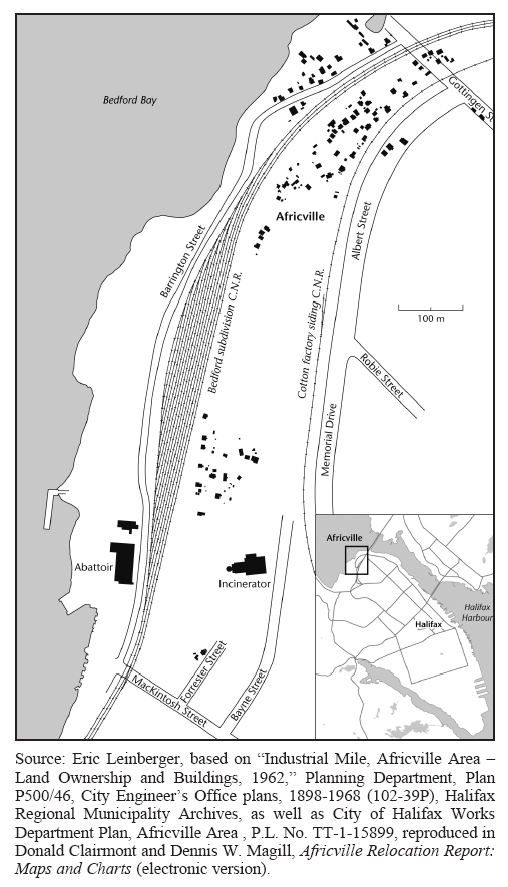

35 Not being able to even locate a property might sound incredible, but a map and an understanding of how Africville’s settlement evolved go a fair distance to explaining how and why this was the case. As the map indicates, there was no grid pattern of settlement in Africville because there was nothing even approximating a grid as only a small part of the community was ever surveyed.

36 The area, about 12 acres in size, was first settled in the 1840s by descendants of Black refugees from the War of 1812-14. Like much of Halifax’s north end, Africville was rural in character and remained so into the 20th century: people kept chickens, pigs, goats, and horses, supplementing their tables by fishing in the Bedford Basin. As Halifax grew in the second half of the 19th century Africville grew as well, expanding out from the initial 12-acre settlement. The municipal government allowed industry to encroach: railway tracks were laid through middle of community in the 1850s and expanded twice before the First World War, and a number of factories opened that manufactured bone meal fertilizer, cotton, and nails among other things. A coal handling facility on the waterfront and a stone crushing plant added to area’s industrial character. As well, Africville was also the location of an abattoir, the city’s sewage disposal pits (1858), the infectious diseases hospital (1870s), and a dump (1950). A residential population grew up amidst these developments, building houses and outbuildings in the spaces in between, giving the area its somewhat anarchic appearance.55

37 Africville’s illegibility meant that MacDonald’s job began with deciphering land tenure – determining what, literally, was to be negotiated. Ascertaining the boundaries of the properties in question and their genealogy was made even more complex by the fact many, if not most, of Africville’s property holders died intestate.56 In the absence of legal records, city officials realized they would have to investigate long-term occupation as well as registered deeds as legitimate sources of title in Africville.

Display large image of Figure 2

38 To establish possessory title, Peter MacDonald had to rely on the local knowledge of neighbours and long-time residents.57 Although it took some time for him to gain their trust to the extent they felt comfortable sharing what they knew, his patience was rewarded often with precise information.58 For instance, in determining the extent of one piece of land allegedly purchased in the 1920s, MacDonald reported that "the older residents of the community, including Mrs A, have stated that the approximate dimensions of the property when purchased were 100’ x 100’. Shoreline has receded so the property has an angular appearance and is now about 100’ x 60’."59 In another case, where ownership was at issue, the social worker confirmed that the "senior residents of the community of Africville" not only verified that B was the owner of Building No. --, but that she also built it: "They stated that in 1958 or 1959, Mrs B and Mr C built dwelling No. --. Mrs B supplied the funds for material and Mr C the required technical skills."60

39 In summarizing how he worked, Peter MacDonald emphasized how important community views were to ascertaining ownership. At first he "tried to get the story from the owner, and from there find out something at the records office, both at city hall and at the court house." But MacDonald also noted that "where there were no actual deeds . . . [we] pretty well went along with the story . . . the people would give. The property was handed down [from generation to generation], more or less by word of mouth . . . . So there was actually no written document for each particular property saying that one member of the family owned so many square feet and another owned another section or part of the property. So . . . [we] went along pretty well with the status quo as it was in the community."61

40 The information gathered in the process of establishing ownership and setting compensation was not confined to boundaries and buildings. As MacDonald observed, arriving at an amount was not a matter of applying a formula: "You couldn’t go across the board and say this type of house, this type of property will pay X number of dollars." Instead, "a fair and equitable settlement" required considering whether the individuals involved were elderly or had dependent children, what their source of income was, and what debts they had – particularly for back taxes or hospital care. These would be cleared, and the amounts owing added to the compensation package.62 As well, MacDonald made a determination about what in the way of appliances or furnishings people might need in their new lodgings, adding a "furniture allowance" to relocatees’ financial settlements.63

41 Property assessment and an assessment of character, as well as circumstance, could go hand-in-hand, as MacDonald’s notations about who was "steadily employed," kept up their houses, or fostered children, suggest.64 But the social worker was not alone in making judgements: Africville residents had opinions about each other that also influenced the settlements that were struck. In reporting on DE’s situation, for instance, MacDonald noted that the "general feeling in the community is that Mr. E is a very industrious individual and that very rarely does he lose time from work because of his drinking problem." Although the Es were separated because of "Mr. E’s excessive use of alcoholic beverages," the social worker’s informants felt that there was "a possibility that upon the successful completion of a property settlement with the city, Mr. and Mrs. E may decide to assume their role as husband and wife."65

42 The extent of local knowledge and the degree to which some of MacDonald’s informants were able to comment on the circumstances of their neighbours speaks to the degree to which the relocation process was intertwined with community dynamics and could be incorporated into the local repertoire of welfare practices. Some residents of Africville saw the negotiations with MacDonald as a way to extend their informal network of community-based social security. If DE’s negotiations with the city went well, for instance, he might be able to salvage his marriage, something that could benefit both his estranged wife and him. Relocation would also help widow FG. At age 79 or 80, she was "becoming forgetful" and was "a source of worry to her neighbours." When "some persons in the community" took advantage of her by "charging long distance telephone calls to her number," a "general consensus" emerged among residents that "it would be to Mrs. G’s advantage if she were to sell and move away to live with her adopted daughter."66

43 As illustrative as these examples are of the networks of social security that existed in Africville, it is important to remember that the personal nature of responsibility and obligation meant that support could be withheld as well as bestowed; when given, it was given – or received – willingly, grudgingly, or strategically. "Community" was about acceptance, but it could have an astringent quality too; this was something that the poet Robert Frost captured well in this exchange between a husband and wife: "Home is a place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in," offered Warren. "I should have called it something you somehow haven’t to deserve," Mary replied.67

44 Some Africvillers experienced the astringency of home directly, when references to their propensity to drink to excess, perhaps made innocently or in passing, or perhaps purposefully, ended up being repeated in the Halifax City Council’s Africville Sub-Committee as it discussed settlements: "If he got a grant of so much money it would end up back in the provincial coffers via the liquor store. . . . Okay, maybe in those cases we were playing God, I don’t know," recalled one alderman. "But in these cases we felt that nothing would be served by giving that person a larger grant. Whereas you had a fellow, like I say, who had a good steady job and was of fairly good character, you would stake him."68

45 If the illegibility of Africville made it impossible for MacDonald to simply impose settlements and forced him to consult with residents, then it also prevented residents from acting collectively. Just before the relocation, there was an effort to organize the people who lived in one area of the community to sell their land as a bloc. The attempt failed because some people had title to their land while others did not; in other words, efforts to organize came to naught because land title could not easily be clarified for the entire area, which put off potential buyers.69

46 While the uncertainty surrounding land ownership was an obstacle to collective bargaining, so too was the absence of a single leader or group of leaders in the community who could deal with the city. MacDonald came to his job in Africville thinking he would work with a handful of individuals who spoke for the community. His expectations were shaped by his experience in Cape Breton, where the union defended the interests of individual workers who would otherwise be disadvantaged if they had to deal with mine management directly. "Being brought up in that kind of a system, I just assumed . . . I would be able to talk to one or two or three people who would have more or less the control of the rest of the community," he recalled. "I found that wasn’t so." While Africville certainly had its leaders, in MacDonald’s view none of them, either as individuals or together, commanded a following that was large enough to be considered a majority.70

47 In part, the absence of a leader or leadership group reflected the diversity of the community and the divisions within it. Africville may have been a single place, but it housed several distinct groups of people.71 Noting that intermarriage linked Africvillers, and that the community was stable, Clairmont and Magill identified four different groups, each distinguished by their origins and kinship ties, their housing status, the part of Africville they lived in, and their involvement with the Baptist church – one of the anchors of the community.

48 The "marginals and transients" did not have any kinship ties to people in Africville, nor were they active in the church. The group included a handful of whites who, along with their black counterparts, lived in rented lodgings in an area known as "Around the Bend" in reference to the railway tracks that ran through the community. "Mainliners" had married into the community and had lived in Africville’s main settlement area for a significant length of time. The community’s elite had regular jobs and owned property; some were particularly active in the church. "Oldliners" were, as the name suggests, the people whose ties to the community went back to the mid-19th century. They were the heart and soul of Seaview Baptist Church and usually owned homes, either in the main settlement or Around the Bend. Finally, there were the "residuals," a group whose kin ties went back no earlier than the last quarter of the 19th century. They were not involved in the church, had no legal claims to land or property, and rented or squatted in "Big Town" – ten houses that comprised what one resident called "the baddest part of Africville."72

49 Important itself to understanding the complex character of Africville, this pattern of social differentiation also manifested itself in different attitudes towards relocation. Not surprisingly, oldliners, who were the most deeply rooted in Africville, showed the most reluctance to leave, as did those Clairmont and Magill called residuals. In general, regardless of social group, the oldest Africvillers were the ones who opposed relocation the most. Mainliners comprised the handful of residents who did not like Africville and were most willing to move.73 Interestingly, the three individuals whose names appear most often in the records as community leaders were mainliners: two were born in neighbouring communities, and the third was from the West Indies. Although Africville’s leaders commanded a following of perhaps four or five families each, both they and their supporters were divided by different views on compensation.74 The oldest among them argued that the city should give "a home for a home," while another pushed for financial compensation based on land value, reasoning that this would allow residents to purchase whatever kind of property they wished. The third, who removed himself from both a leadership role and the community early on, wanted something in between; indeed, he supported rehabilitation rather than relocation.75

50 Although Seaview Baptist Church had been an important anchor of the community historically, at the time of the relocation its influence had eroded significantly such that Clairmont and Magill argued it was "an inadequate base for community action." Indeed, it was only after the community was destroyed that the church regained its power – this time as a locus of "relocation grief" and a cornerstone of the imagined community that arose from the rubble of its razed buildings.76

51 Not being able to deal collectively with the residents, MacDonald was forced to negotiate with them family by family or one by one. This had a corrosive effect on what solidarity there was among Africville residents, as well as – occasionally – MacDonald’s own legitimacy. In a small community, there were few secrets, least of all about who got what compensation. Sensitive to this, the city tried to control the flow of information: although it was required to publish settlements in the newspaper, it did so by property number, rather than the names of the owners. Jealousies were aroused nevertheless, and when rumours circulated about what their leaders had received, some Africville residents accused them of being selfish and disingenuous – acting as community spokesmen in order to leverage their own position.77

52 Peter MacDonald also found himself caught in the cross-currents his decisions created: he was either the dupe of the cunning men and women of Africville or the nearest thing Halifax had to Niccolò Machiavelli, playing residents off each other. Dealing with people individually also undercut his authority: it made his decisions appear more arbitrary and perhaps less legitimate. While his job required him to deal with all of Africville’s residents, it was clear to them that MacDonald spent more time with some people than with others. It could hardly have been otherwise. Those he got along with personally or who were supportive, received more attention; so, too, did the people he identified as possessing some influence, like the community’s senior residents or those who had a position of authority in the church.78 Those who rented or squatted got relatively little attention, in part because MacDonald’s energies were focused on the all-consuming task of sorting out the ambiguities surrounding property ownership.79

53 While it is hard to say whether more consideration meant better treatment, the time MacDonald spent with people created a space for some residents to shape the process of relocation. The three to four months it took on average to come up with a deal, and the time MacDonald spent with people during the follow-up after relocation, gave some Africvillers the room to wiggle a better deal for themselves.80 For instance, one woman recalled how she routinely tricked the social worker out of money from the city. After she had been moved from her home in Africville, she "used to call up and casually ask for repairs, or casually state some problem she had," and MacDonald would almost always comply as part of the relocation program’s follow-up initiative. She was particularly delighted about one occasion when she convinced him to pay for a whole new floor for her house, but she also extracted grocery money from MacDonald by manufacturing one of her "freek [sic] accidents with her washing machine or some other machinery." In her opinion, "if more people in Africville had been as smart as she [was] then they would have got more out of Peter MacDonald." Indeed, "tricking Peter" showed that she "was as smart as white folks and even smarter because she was getting their money."81

Remembering Africville

54 Looking at how the relocation was accomplished on the ground reveals continuities in the delivery of welfare. The postwar state had some pre-modern qualities: welfare was still a face-to-face matter, characterized by a good deal of discretion and moral judgement. Mapping the details of dispossession also divulges the complexities of Africville as a place. Its social differentiation as well as its illegibility meant that MacDonald’s decisions were entangled with community dynamics, giving state power a hybrid quality and casting its oppression in a more multifarious light.

55 In the end, however, Africville was still destroyed, and its residents scattered throughout the city. So why does this story matter?

56 For one thing, it matters because it helps us understand the people who were involved as more than abstractions. They were not just "officials" or "authorities," "residents" or "relocatees," "whites" or "blacks," but imperfect people who acted, or tried to act, as thoughtfully as they could when they could. They did so within the context of profound racism, before a more militant language of rights had been articulated and before citizen participation was an accepted and financially supported part of urban planning.

57 Acknowledging this context does not mean individuals should not still be held to account for what they did – for exacting harm in the name of extending help – or that we ignore the structures of inequality that conferred power on some and took it away from others. Nor does it deny the possibility that the progressive politics of the members of the HHRAC as well as Robert Grant and Peter MacDonald might have masked a murkier and more longstanding agenda held by other city officials and supported by certain members of the public. It simply means that we also need to acknowledge who they thought they were and what they thought they were doing. Avoiding what E.P. Thompson called the "condescension of posterity" means taking everyone who was involved in the relocation on their own terms – as well as ours.82

58 Remembering Africville means acknowledging Robert Grant’s insistence, as Halifax’s director of development, that the city not expropriate – that its officials act with compassion. Remembering Africville means taking Peter MacDonald seriously when he said he tried to give Africville’s residents choices where he could. For the Cape Breton social worker, "everyone had a right to a decent standard of living" and decency was determined by being able to choose – what your Africville property was worth, what sort of lodgings you wanted to house yourself in after you left that community, and what kind of furniture you had.83 Because a decent life was also determined by how you were treated by others, MacDonald worked hard at establishing what he called a "meaningful relationship" with everyone he dealt with.84 Finally, remembering Africville means recognizing that it was a point of pride with Mrs X that her "freak accidents" fooled the social worker – that she managed to pull the wool over his eyes time and time again – proving she was smarter than her neighbours and white folks as well. It did not change the fact she lost her home and community, but to turn a deaf ear to her laughter and satisfaction at besting "the Man" seems wrong – as does ignoring the ways that Grant and MacDonald chose to act.

59 When Donald Clairmont and Dennis Magill did the interviews for their report on the relocation, they asked a number of people who had lived in Africville to describe it. One of the responses helps make my point: "Africville was a place where coloured people lived together trying to do the best they could."85 Although the respondent was referring to its residents, what he said applied to everyone involved in the relocation: Africvillers, the city’s bureaucrats, the social worker, and the members of the Halifax Human Rights Advisory Committee. Africville was a place where all these people tried to do the best they could.

60 Perhaps this is just a story about how the road to Hell is paved with good intentions. I think it is more than that. Ultimately, the map of power that emerges from looking at the Africville relocation matters because it shows us people trying – at desks, over fences, around kitchen tables, and at community meetings. To a great extent, these are the spaces where we live our lives – where we become who we are. The choices we make in these spaces, small though they might be – to be decent and devious, kind and cruel – are how we make our own history not under conditions of our own making, where we do our best and worst. They are the spaces where we are most human, and for that reason we need to take notice of them.

61 If Africville allows us to see who we are, it also gives us a standpoint from which to tell a larger story about why certain schemes to improve the human condition fail; it shows us the possibilities and limits of the liberal welfare state in meeting human needs.

62 James C. Scott and the scholars who have taken up his insights trace the failure of forced relocation and other large-scale, state-sponsored projects to deliver social benefit to a particular way of seeing. The synoptic or bird’s eye view characteristic of planning renders invisible the very thing Scott argues is necessary for high modernist projects to work, namely local knowledge. Local knowledge, or "metis," as he calls it, is empirical; it is substantive information that comes from an intense and deep engagement with a material place. But it also encompasses the social relations and culture that arise from that engagement and that shape identity. Not only did high modernist initiatives like urban renewal, collectivization, and scientific forestry ignore how local knowledge sustained societies, but their implementation also resulted in its destruction and the destruction of the relationships and culture that were a part of it.86

63 While the way the state saw Africville – as a slum and a ghetto with no redeeming qualities – certainly contributed to the tragedy of relocation, the failure of urban renewal to deliver what it promised was not because the state ignored local knowledge entirely. Indeed, one could argue that the tragedy of Africville occurred (at least in part) precisely because the state was able to deploy local knowledge.

64 Rather than local knowledge, the failure of this particular scheme to improve the human condition was rooted in how the state saw itself. To account for Africville we have to explore the contours of liberalism; we need to examine how liberals defined the role of the postwar state, drawing the line between legitimate and illegitimate intervention and how they conceived of human needs and how best to meet them. In other words, understanding the failure of forced relocation in postwar Canada requires understanding the ideology that structured the exercise of state power.

65 Albert Rose and the city conceived of Africville as a "welfare problem," a place whose residents had innumerable needs as a result of the racism that had shaped their lives. Meeting human needs is a challenging task for the state since needs vary both among people and over an individual’s lifetime. Liberalism has met this challenge by drawing a distinction between public needs that the state has a responsibility to meet (for things like food, shelter, education, health care, and employment), and private needs that it does not and, liberals say, it should not meet because those needs are so varied, so individual, and so elusive. And if we do not always know what we need, then how can the state presume to know, much less impose, those needs on its citizens?87

66 Public needs are the ones that become entitlements; they become, for instance, the claims or rights we have to adequate housing, health care, or education. Private needs stay private. If the state meets our public needs adequately, then all of us as individuals will be in a better position to meet our private ones – or so the theory of liberalism goes.

67 Private needs also remain private because so often it takes all the energy we have and then some first to achieve and then to maintain the public ones, especially in the face of a hostile ideological and financial climate that is often used to justify a smaller state. In the struggle to establish and keep the entitlements the welfare state grants us, it is easy to forget that public needs are not the only ones we have.

68 For all of its gains, what is lost in our focus on rights is the need for community. This is why Africville is so important: in showing us the difference between integration and belonging it exposes the limits of the liberal welfare state. In the debate over Africville, the focus was on how residents lacked adequate housing, education, and employment because they were stuck in a ghetto and immobilized by racism. Moving Africvillers into the city was a way to integrate them and meet their needs. For liberals, mobility was the key to achieving a just society. As Pierre Trudeau put it in 1968, "Every Canadian has the right to a good life no matter what province or community he lives in."88 For Trudeau, the goal of the state was to facilitate the good life, to help individuals realize their humanness most fully.89 In that sense, mobility was not just the best guarantee of the good life, but it was also the best guarantee of freedom as it afforded us the opportunity to be who we are and can be. Given this, it is perhaps not surprising that a mobility right is enshrined in Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms (s. 6), and that it is one of the few that is not subject to the "notwithstanding clause."

69 The connection between mobility and freedom is a longstanding and powerful one, so much so that governments in postwar Canada were prepared to use forced relocation – to move people against their will – as a strategy to deliver the welfare state’s promise of universality. But giving Africvillers the entitlements that other people enjoyed – giving them equal rights and the opportunities that afforded – did not do anything to reconfigure relations in Halifax in a way that would create a different sense of belonging. Maybe it would have had there been more follow through, had the programs for education and employment training been adequate, if the public needs of Africville residents had been met more fully. But that seems unlikely. What residents missed most after leaving Africville was something no program could have provided: friends and fellowship – the things that made home.

70 The failure of the Africville relocation did not lay primarily in inadequate programming. Instead, it was rooted in a fundamental difficulty the liberal state has in where and to what extent to intervene – in drawing the line between respecting individual choice and meeting needs. Halifax Mayor John Lloyd, who oversaw the relocation, captured this uneasy tension in his comments about Africville and the difficulties inherent in allowing people to make their own choices about how to live, on one hand, and forcing them to do so in a certain way on the other: "Sometimes, people need to be shown that certain things are not in their best interests and not in the best interests of their children," he insisted. "Certainly, you don’t coerce people against their will. But should there be violations of minimum [housing] standards, then you have no alternative but to enforce the law."90

71 More broadly, the failure of the Africville relocation rested in the ideas that structured the liberal welfare state – in the balance liberals struck between freedom and solidarity. That balance could not incorporate fully the human need for belonging and the extent to which belonging was also a part of the good life – a powerful source of freedom. To liberals at the time, the desire on the part of Africville’s residents to rehabilitate their community or to move as a group to another part of the city was anathema. In their view, this kind of belonging was segregation, it was exclusive, it was racist. But in place of this idea of community that seemed based on exclusion, liberals could offer only the most abstract sense of belonging – one that referenced a "universal brotherhood of man." Despite its legal power, the appeal to a common humanity and to our rights as human beings was not enough to nourish the need for community.

72 Africville teaches us many things. And one of them is that we need a better language and philosophy to think about belonging, one that is neither exclusive nor based on nostalgia but which still incorporates something of the spirit of Africville: a place where there was "always . . . room for one more" and where people were responsible to each other as well as for each other.91