Paths to the Assembly in British North America:

New Brunswick, 1786-1837

Kim KleinShippensburg University of Pennsylvania

Abstract

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, New Brunswick assemblymen followed paths to the assembly that conformed to colonial British American standards. These paths included securing appointments to important local offices and accumulating wealth and economic influence. Because many first-generation assemblymen successfully transferred these assets to their political heirs, prominent social origins and the family connections that accompanied them had become important components of electoral success by the time that the colony’s second generation of elected political leaders entered the assembly during the 1810s and 1820s. This development signified the emergence of local oligarchies in numerous New Brunswick constituencies.Résumé

À la fin du 18e siècle et au début du 19e siècle, les députés du Nouveau-Brunswick empruntèrent des voies menant à l’Assemblée qui étaient conformes aux normes de l’Amérique coloniale britannique. Ces voies comprenaient l’obtention de nominations à des postes importants sur la scène locale et l’accumulation de richesse et d’influence économique. De nombreux députés de la première génération réussirent à transmettre ces atouts à leurs héritiers politiques, de sorte que les origines sociales distinguées et les liens familiaux qui les accompagnaient étaient devenus d’importants facteurs de succès électoral au moment où la deuxième génération de dirigeants politiques élus de la colonie firent leur entrée à l’Assemblée, dans les années 1810 et 1820. Cette situation entraîna l’émergence d’oligarchies locales dans de nombreuses divisions électorales du Nouveau-Brunswick.1 AT THE CONCLUSION OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION in 1783, thousands of defeated Loyalists had few options but to leave their homes and begin life anew in another part of Great Britain’s truncated American empire. Although British authorities assumed that the Loyalists were unified by their continuing allegiance to the British Crown and would assimilate relatively easily into Britain’s remaining colonies, the experiences of those who sought refuge in the sparsely settled northern territory that, in 1784, would become the colony of New Brunswick contradicted their assumptions. Along with the challenges of creating viable settlements in New Brunswick’s demanding physical environment, the social, cultural, and economic diversity of the Loyalist refugees, coupled with their ongoing conflicts with the territory’s Native inhabitants and earlier French and British settlers and their complicated relationship with the British Crown, created considerable turmoil in the new colony in the immediate post-war years.1

2 Out of this disorder, though, New Brunswick’s diverse inhabitants created a stable and economically significant colony in Great Britain’s restructured American empire.2 Critical to this transformation was the development of stable provincial political institutions – lieutenant governor, council, and representative assembly – based on British and colonial British American models. Thomas Carleton, the colony’s first lieutenant governor, and the Loyalist elites who served on the appointed council, anticipated that the representative assembly would serve as a mere “ratifying body” for their executive decisions. But in a process that mirrored the struggles between executives and legislatures across British America before the American Revolution, the increasingly assertive group of elected political leaders who served in New Brunswick’s representative assembly gradually wrested power from the colony’s appointed governor and council. By 1837, when the representative assembly acquired control of New Brunswick’s most valuable resource (its Crown lands), it had become the colony’s dominant political institution.3

3 The men who served in the colony’s increasingly influential representative assembly powerfully shaped the character of the representative government that emerged in colonial New Brunswick during its first half century. Throughout the early modern British Atlantic world, power in representative assemblies was generally vested in prominent and prosperous men who had the independence and ability required to promote the institution’s important responsibilities: safeguarding the people’s rights and liberties and advancing the public good.4 Yet in New Brunswick, local and visiting observers expressed concerns about the qualifications and motivations of those elected to serve in the colony’s assembly. Prominent Massachusetts Loyalist Edward Winslow captured these concerns after the elections held to select the members of New Brunswick’s Second Assembly in 1792-93, when he complained “our Gentlemen have all become potato planters and our shoemakers are preparing to legislate.”5 And Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Gubbins, a British officer who toured the colony in 1811, recorded disparaging observations in his diary: “The members of the lower house are many of them poor and ignorant to whom the ten shillings a day whilst employed, is their greatest object of ambition and their private interests and popularity are more consulted than is the public good.”6

4 Despite these misgivings, an examination of the backgrounds of the 152 men who served in the colonial assembly between 1786 and 1837 reveals that the paths to the assembly that New Brunswick legislators followed conformed to those established by assemblymen throughout colonial British America, before and after the American Revolution.7 Colonial New Brunswick assemblymen were increasingly distinguished by their prominent social origins, extensive records of service in local offices that demonstrated their fitness for offices of greater public trust, wealth that guaranteed the independence of their actions, and – to the extent possible in a new colony – formal education. As first-generation assemblymen built on these foundations to consolidate their local influence and convey power to their political heirs, their actions had important implications for the character of representative government in colonial New Brunswick. Ultimately, they contributed to the formation of local oligarchies that would dominate electoral politics in many constituencies in colonial New Brunswick.8

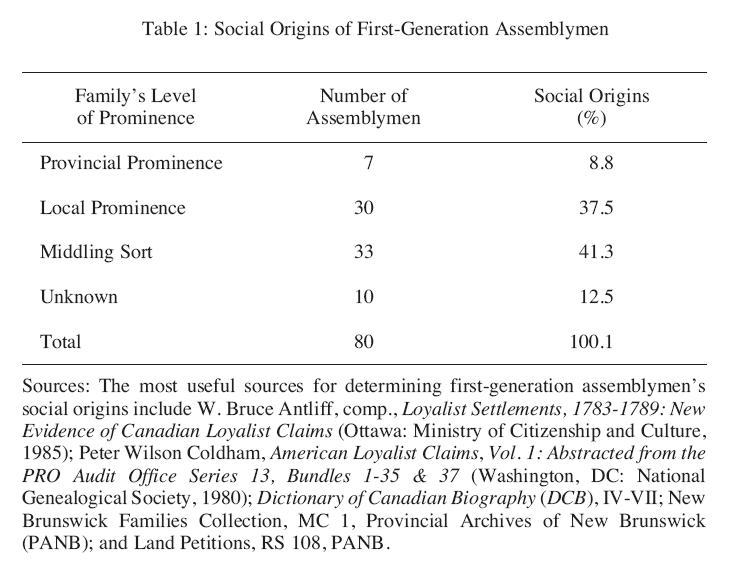

5 As Edward Winslow noted, not all of New Brunswick’s earliest assemblymen could claim illustrious family origins. Table 1 summarizes the social origins of New Brunswick’s first-generation legislators.9 Only seven of New Brunswick’s eighty first-generation assemblymen were members of the leading families of Great Britain’s former American colonies. Members of these families had colony-wide reputations, commonly held provincial offices, controlled substantial fortunes, and had college educations. John Robinson, who represented Saint John City in New Brunswick’s Third Assembly (1803-1809), epitomized assemblymen whose families possessed provincial prominence in British America before the American Revolution and successfully transferred their prominence to New Brunswick. Robinson was the son of Beverley Robinson, one of New York’s largest landowners and most prominent Loyalists, and the grandson of John Robinson, whose many offices in pre-revolutionary America included the presidency of the Virginia Council. The future New Brunswick assemblyman married into another prominent colonial New York family, the Ludlows. His father-in-law, George Duncan Ludlow, was an associate justice of the New York Supreme Court from 1769 to 1776. After the American Revolution, Ludlow moved to New Brunswick and secured one of the colony’s most important patronage appointments as chief justice of the Supreme Court in 1784.10

Table 1: Social Origins of First-Generation Assemblymen

Display large image of Table 1

6 Almost two-fifths of the colony’s first-generation assemblymen were drawn from locally prominent British and colonial British-American families. The family of Saint John assemblyman Bradford Gilbert typified assemblymen with locally prominent origins. Before the war, Gilbert resided at Freetown, Massachusetts, where his father, Thomas Gilbert, was a justice of the peace and colonel of the local militia. Thomas Gilbert also represented his county in the Massachusetts General Court, but he did not become a leader in the colonial legislature and thus his prominence remained primarily local in nature.11

7 By emphasizing their loyalty and wartime sacrifices and service to the Crown, these colonially and locally prominent families often gained preferential access to land grants and patronage appointments in New Brunswick. This preferred treatment, along with the capital that they brought to New Brunswick and the capital that they gained through their successful claims to reimbursement for property lost during the American Revolution, provided the foundations for continued social prominence and prosperity in their new homeland.

8 For the majority of New Brunswick’s first-generation assemblymen, however, prominent social origins were not a prerequisite for gaining an assembly seat. At least two-fifths of New Brunswick’s first-generation assemblymen were members of families of the middling sort, including the tradesmen whose political aspirations Edward Winslow held in such contempt. The difficulty of determining the social origins of another ten of the first-generation assemblymen suggests that they were also members of the middling or lower social ranks.12 Yet while the majority of first-generation Loyalist assemblymen may have had relatively undistinguished social origins, the American Revolution and resettlement in New Brunswick provided significant opportunities to enhance their position in colonial society. Assemblyman Munson Jarvis is a case in point. Before the American Revolution Jarvis worked as a silversmith in Stamford, Connecticut, where his family had resided since the 17th century, earning their living primarily as tradesmen and holding few local offices. The dislocations of the American Revolution provided Jarvis with opportunities to improve his rank in colonial society, and he acquired wealth and status as a leading merchant in Saint John after the war.13 And even assemblymen who migrated to the region before the American Revolution found significant opportunities to improve their status. Assemblymen James Simonds of Saint John and Charles Dixon of Sackville had relatively humble social origins as the sons of a middling Massachusetts farmer and a Yorkshire bricklayer respectively. But after they settled in Nova Scotia during the 1760s and 1770s, they began successful mercantile enterprises, amassed substantial landholdings, and became prominent officeholders in the region.14

9 A record of public service in local civil, military, and religious offices that demonstrated fitness for positions of greater public responsibility was an almost mandatory qualification for men aspiring to elected provincial office in Britain’s pre-Revolutionary American empire.15 Yet in New Brunswick voters selected the members of the first assembly a few months after the province’s first county and parish officers received their appointments from Lieutenant Governor Thomas Carleton in June 1785.16 Although a few of the colony’s earliest assemblymen had been appointed to local offices in the former British colonies and in Nova Scotia, those serving in the First Assembly had scant opportunity to prove their capability for membership in the assembly by carrying out the duties of a variety of local offices in New Brunswick.17

10 Although they could not point to long records of public service in New Brunswick, aspiring first-generation assemblymen could emphasize their records of military service and leadership during the American Revolution. In the nascent society of colonial New Brunswick, military rank acquired as an officer in the provincial forces during the American Revolution was a conspicuous indicator of status. Loyalist officers included men from both prominent and modest colonial American families. For John Saunders, for instance, serving as an officer in the Queen’s Rangers during the American Revolution reinforced his status as a member of a locally prominent Virginia family. Acquiring an officer’s rank in the Second Battalion of DeLancey’s Brigade also enhanced the status of Elijah Miles, a middling Connecticut farmer. Although Saunders and Miles were members of families of differing social ranks in colonial British America before the war, both were addressed as “Captain” in New Brunswick after the war, and the rank that they earned during the American Revolution was a significant component of their status and was cited as an important qualification for political office in colonial New Brunswick.18

11 Because Loyalist officers often led the resettlement of their provincial regiments in colonial New Brunswick, their leadership roles carried over into civilian life in the new colony.19 The close relationships that officers formed with their troops during years of fighting and resettlement provided a strong foundation of support for the officers’ electoral bids for assembly office in colonial New Brunswick, and officers in the British provincial forces were prominent among New Brunswick’s first generation of political leaders. Approximately one-half of the members of the earliest New Brunswick assemblies were officers of Loyalist regiments, who were on half-pay after the American Revolution. New Brunswick’s First Assembly (1786-1792), for instance, included 14 half-pay officers among its 28 members. Many soldiers supported their former officers because of the personal bonds forged during wartime and the material rewards that officers had provided for them in the past and might provide them in the future.20 By 1810, however, the political influence of the American Revolutionary generation was waning, and only about one-sixth of the members of the New Brunswick assembly were Loyalist half-pay officers.21

12 An important qualification shared by other members of New Brunswick’s earliest assemblies was their leadership of the civilian refugees who fled to the territory that became New Brunswick. At least seven first-generation assemblymen were instrumental in organizing the movement of civilian Loyalist refugees to New Brunswick. The board of the largest refugee organization, the Bay of Fundy Adventurers, included two future assemblymen – Amos Botsford and James Peters. Two other assemblymen, Robert Pagan and William Pagan, led the Penobscot Association of refugee Loyalists, and Samuel Dickinson, Ebenezer Foster, and Samuel Denny Street also had prominent roles in the migration of refugees to New Brunswick.22 Their leadership of the refugee movement provided opportunities for these future assemblymen to demonstrate their abilities and build a foundation of electoral support among the refugees that they led and settled with in New Brunswick. For example, in his role as an agent, Amos Botsford travelled to Nova Scotia in the fall of 1782 to identify land suitable for Loyalist resettlement and determine how it would be distributed to Loyalist migrants. During the subsequent voyages to New Brunswick, agents were often responsible for distributing provisions. And after the Loyalists arrived in New Brunswick, these agents further facilitated the resettlement process by assisting with refugees’ applications for land grants.23

13 Although the colony’s earliest assemblymen lacked extensive local civil service credentials and relied on their records of service during and immediately after the American Revolution in their bids for electoral support, those who served in later assemblies, like their counterparts in pre- and post-Revolutionary British America, were usually experienced local officeholders. Service in local offices provided opportunities to demonstrate fitness for offices of greater responsibility and public trust, and such service was a key step on the path to the assembly.

14 British imperial policies heavily influenced the nature of local government and office-holding. As Britain moved to strengthen its authority over its North American colonies after the late 17th century, county government became the predominant form of local government in newly established British colonies because it permitted greater centralized control, including over the selection of local officeholders. When Lieutenant Governor Thomas Carleton was working with the council to create institutions of local governments in New Brunswick during the summer of 1785, he followed imperial instructions by establishing county governments with appointed local officers in the new colony.24

15 New Brunswick’s counties were subdivided into parishes, and parish office was commonly the first stage in a local public service career. The justices of the county courts of general sessions appointed parish officers annually. A survey of parish office-holding careers reveals that two distinctive patterns were evident in New Brunswick assemblymen’s early public service careers. In the most prevalent pattern, aspiring assemblymen progressed through a series of increasingly responsible and prestigious parish offices. Often beginning their careers by holding minor parish offices such as fence viewer, pound keeper, and constable, they eventually acquired the more important positions of assessor and surveyor of roads. In the years immediately preceding their election to the assembly, they were likely serving as commissioners of highways and overseers of the poor. The local public service careers of the men representing the Saint John River Valley counties – Kings, Sunbury, and York – generally followed this pattern and they served, on average, in 11 increasingly responsible parish offices before winning election to the assembly.25

16 Although assemblymen commonly demonstrated their fitness for office by serving in numerous parish offices, a substantial minority had undistinguished records of service in parish offices before seeking election to the colonial legislature. Of the legislators whose pre-assembly public service careers can be reconstructed, almost one-third served in fewer than four parish offices before seeking election. In the most notable contrast to the Saint John River Valley counties, a record of local service proved less significant in the electoral bids of Northumberland County candidates. Of the ten residents who represented the county after 1789, half served in only one parish office or none at all.26

17 While appointment to parish offices was of varying importance in the pursuit of provincial office, appointment to county offices was of consistently greater significance. The colonial executive appointed all county officers, and county appointments were signs of executive favour that confirmed their recipients’ local status. County officers were allowed to use the title “Esquire,” which set them apart from other New Brunswickers. More than marks of status, county appointments also conferred significant powers over other county residents. In New Brunswick’s county government, the most prominent appointed county officials were magistrates – the justices of the peace, quorum, and inferior court of common pleas – who exercised wide-ranging authority over the county’s administrative and judicial affairs. The magistrates’ administrative functions included appointing and overseeing parish officers, administering public works projects, auditing parish accounts, licensing and regulating liquor retailers and tavern keepers, and setting rates for county and parish assessments that had been authorized by the provincial assembly. They also judged criminal cases and civil cases involving smaller amounts of property. Given these broad responsibilities, the offices vested significant political and economic power in their holders over other county residents and were highly sought after.27 In New Brunswick, approximately three-quarters of the assemblymen received appointments as magistrates, and two-thirds of those commissioned as justices of the peace eventually received more prestigious commissions as justices of the quorum and justices of the inferior court of common pleas. The magistrates’ considerable powers, which were designed to advance the public good, could also promote their private interests on election days.

18 Acquiring a commission as a magistrate was an important step on the path to the assembly in colonial New Brunswick, just as it had been in British American colonies before the American Revolution.28 In their election campaigns, magistrates frequently referred to their service as an important qualification for office. In his assessment of the qualifications of the candidates running for the assembly in the 1827 election in Saint John, the editor of the New Brunswick Courier wrote, “Mr. [Gregory] Van Horne is a gentleman well known among his fellow-citizens, having discharged the duties of a City Magistrate for several years with credit to himself and benefit to the public.”29

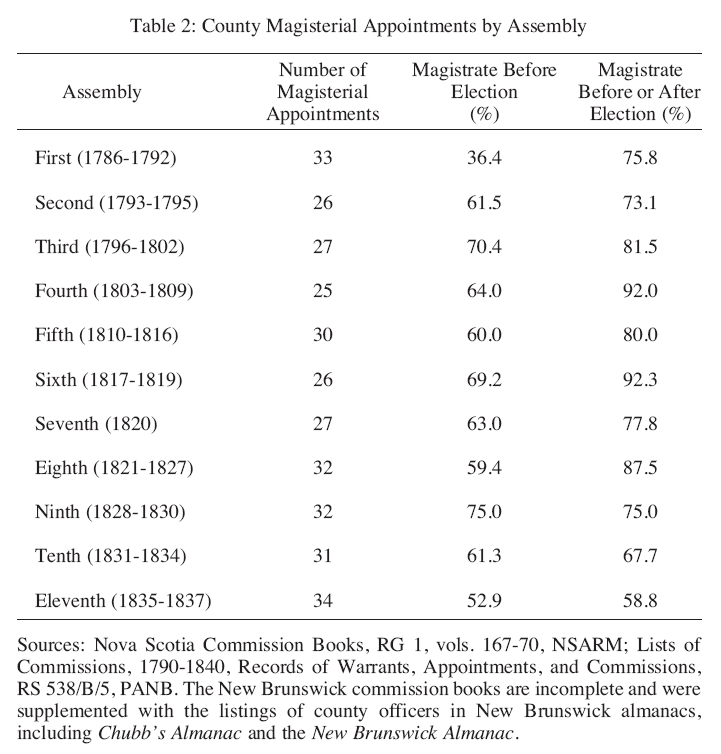

19 Because early records of county magisterial appointments are incomplete, the proportion of New Brunswick assemblymen who are known to have received commissions before their election was relatively low in the First Assembly (1786-1792). But as Table 2 indicates, a majority of those elected to each succeeding assembly were magistrates at the time of their election. More than 60 per cent of the members of the Second Assembly (1793-1795) were county magistrates at the time of their election, and the proportion remained consistently at or above 60 per cent for next four decades, reaching a high point during the Ninth Assembly (1828-1830), when three-quarters of the legislators held magisterial commissions.30

20 Of the 35 assemblymen who did not receive magisterial commissions, at least one-third received other important county appointments before their election to the assembly. One assemblyman served as a county sheriff and at least four served as county coroners, but the most common other county office awarded to future assemblymen was the clerkship of the peace and the inferior court of common pleas. At least seven assemblymen were appointed to this important county office before their election to the assembly.31 According to the original county warrants issued in 1785, the qualifications for clerks included “integrity, skill and knowledge of the Laws”; so it is not surprising that all seven appointees had legal training.32 The clerks’ duties including taking the minutes of the courts of general sessions of the peace, preparing legal documents, managing county correspondence, and a variety of other responsibilities related to administering county affairs. Appointments to these important county offices were another sign of executive favour that confirmed their holders’ local status. Although only one county clerk is known to have served in the assembly before 1810, their numbers increased thereafter. At least two county clerks served in the Fifth Assembly (1810-1816), and one county clerk served in each of the three assemblies that convened between 1817 and 1827. Two clerks served in the Ninth Assembly (1828-1830), and three clerks were elected to the Tenth (1831-1834) and Eleventh (1835-1837) assemblies. Even though the proportion of those who received magisterial commissions before their election to the assembly declined during the 1830s, the presence of an increasing number of county clerks in the assembly underscores the fact that an executive appointment to county office continued to be an important prerequisite to launching a successful bid for assembly membership in colonial New Brunswick.

Table 2: County Magisterial Appointments by Assembly

Display large image of Table 2

21 A few other assemblymen did not receive county appointments before their election to the assembly because they had instead received higher appointments. Three members of the First Assembly (1786-1792) received provincial appointments before their election. Jonathan Bliss was the colony’s attorney general, Ward Chipman, Sr., was the colony’s solicitor general, and John Saunders, who was elected to the assembly in a 1791 by-election for York County, had been appointed a justice of the New Brunswick Supreme Court a year earlier. Only two other assemblymen – John M. Bliss and Thomas Wetmore, who served as solicitor general and attorney general respectively – received provincial appointments before serving in the assembly. The frequent protests during elections warning against the dangers of increasing executive power if government appointees dependent on government salaries were elected to the assembly – warnings that were common in 18th-century British American politics – may explain why so few high appointed and salaried government officials won election to the assembly.33

22 Like appointments to county civil offices, appointments as officers in the county militias both confirmed and conferred local status and power. Consequently, a militia appointment became another important step on the path to the assembly in colonial New Brunswick. New Brunswick, a product of the American Revolution, faced threats of war – if little actual combat on its soil – from its earliest settlement through its first 50 years. Although the British government usually maintained a small force in the colony, and the assembly consistently asserted that defense should be an imperial and not a local colonial responsibility, the militia was considered a key part of the colony’s defense. New Brunswick’s first militia act, passed in 1787, authorized the organization of militia regiments in each county, and all males resident in the colony between the ages of 16 and 50 were to be enrolled in the county regiments. The regiments were subdivided into battalions as the population grew, and the battalion officer ranks were lieutenant colonel, major, captain, first and second lieutenant, and ensign.34 According to the Militia General Orders published in the Royal Gazette, those appointed as officers were to be “fit gentlemen” of “experience and weight in the Society.” The provincial commander-in-chief and the executive made appointments based on recommendations from local commanding officers. Initial appointments were usually made at the lowest level – ensign – unless the appointee had prior military experience, and advances through the officer ranks were made as vacancies occurred.35

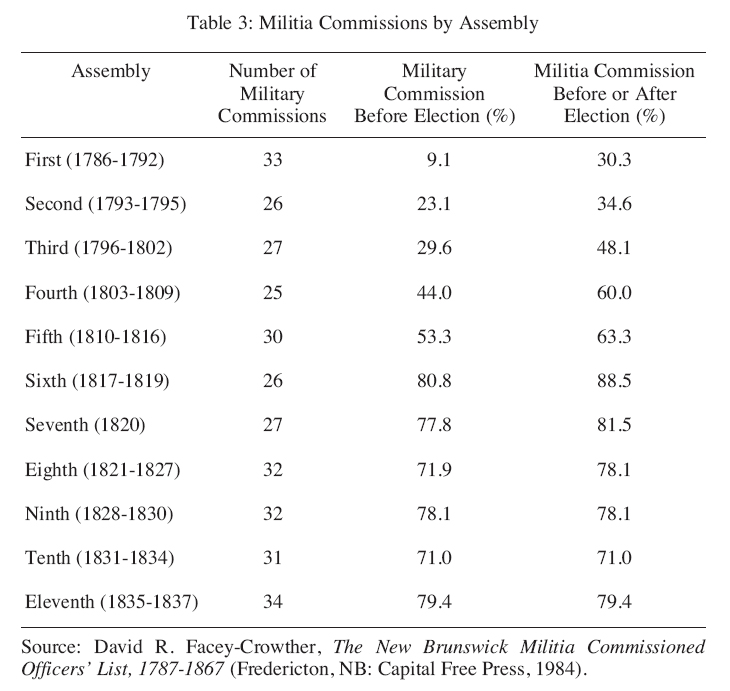

23 Nearly three-fifths of New Brunswick assemblymen received a commission as an officer in the county militia, and one-third of them eventually commanded their local battalions.36 Of the 88 New Brunswick assemblymen who received militia commissions, 80 per cent received their commissions before their election. As a step on the path to the assembly, as Table 3 indicates, a militia commission became significantly more important over time.

Table 3: Militia Commissions by Assembly

Display large image of Table 3

24 The proportion of assembly members who received commissions as officers in their county militia regiments increased steadily until the mid-1810s, when more than four-fifths of those who served in the Sixth Assembly, which met from 1817-1819, had received a commission as an officer in the county militia before their election. Thereafter, approximately three-quarters to four-fifths of those elected before 1837 had received officer commissions before their election. Even though the role of the militia in colonial New Brunswick remained largely “ceremonial and social rather than military,” a commission as a militia officer was an important mark of official favour and local status that elevated prospective assemblymen above the rank and file of colonial society while also conferring power over their fellow county residents on annual mustering days.37

25 In filling positions of responsibility in local civil and military affairs, New Brunswick’s future assemblymen demonstrated their leadership skills, commitment to public service, and suitability for higher office in a variety of local settings. Not all assemblymen, though, were model officeholders. The provincial executive dismissed at least two county militia officers due to “improper behavior,” and other appointees were dismissed because they refused to carry out the responsibilities of their offices.38 Yet, in most constituencies, appointment to these county offices was an important prerequisite to securing the status and power that was essential to obtaining elective office. And, over time, appointments to county offices were increasingly influenced by the recommendations of the then-current officeholders; accordingly, such appointments signaled the support of not only the colonial executive but also of prominent members of the local community, who increasingly controlled access to appointed positions of political power through their connections to the colonial executive.

26 As local officeholders occasionally complained, their positions were “of trust and responsibility rather than emolument.”39 Although a few county magistrates collected considerable sums in fees, in most cases the fees that parish and county offices commanded were usually meager and officeholders could spend hundreds of hours each year discharging their official duties with scant promise of financial reward. Therefore colonial office-holding required not only the willingness to carry out often-onerous duties, but also the financial means to do so. The economic costs of assembly service were particularly dear. Before 1800, annual assembly sessions usually lasted fewer than four weeks. By the 1810s, the colonial assembly was commonly in session for two months or more each year. Moreover, many legislators lived at a distance from the seat of government in Fredericton. Although assemblymen included a travel and per diem allowance in annual budget requisitions, the sum hardly covered the costs of service, especially when considering the potential losses associated with long absences from their farms and other business endeavours.40

27 While the guidelines that regulated New Brunswick’s first two elections did not include economic qualifications for candidates, the election act that went into effect in 1795 specified that candidates possess £200 of real estate free of encumbrances.41 The property requirement for candidates reflected prevailing principles that only propertied men had the personal independence required to be disinterested public servants and legislate for the public good and not in their own narrow interests.42 Some of the colony’s earliest candidates undoubtedly barely met the property requirement.43 By the 19th century, however, men whose wealth set them apart from ordinary New Brunswickers dominated the assembly, including men such as Charles Simonds and Hugh Johnston, Jr., of Saint John, who had accumulated such extensive mercantile fortunes that they were able to retire from business and pursue careers in public service.44

28 Because assemblymen were elected locally, determining their economic status within their local communities is more significant in understanding their paths to the assembly than determining where they ranked on the provincial level.45 Parish assessment lists, which include assessments of the real property owned by parish residents, are the most accessible source for analyzing assemblymen’s local economic status. Scattered assessment lists for the period before 1837 are extant for select parishes in four counties – Charlotte, Northumberland, Sunbury, and Westmorland – and these lists include assessments of the real property owned by one-quarter of the assemblymen. With few exceptions, legislators included in the assessments owned real property that placed them among the wealthiest ten percent of their parish’s residents. For example, two assessment lists for Charlotte County’s most populous and important mercantile centers, St. Andrews and St. Stephen, are extant for the 1820s. The lists include 11 of the 21 assemblymen who represented Charlotte County between 1786 and 1837. The 1822 assessment for St. Andrews includes seven assemblymen, all of whom rated among the top ten percent of property owners in the parish.46 In St. Stephen, assessors rated four assemblymen in the parish’s 1823 assessment. Three of the four ranked among the top ten per cent of property owners in their parish. Only George S. Hill, a 27-year-old attorney who did not win election to the assembly until 1830, was not yet among the parish’s economic elite.47 During the 1820s and 1830s, Northumberland County assemblymen were also consistently ranked the top five property owners and paid the highest assessments in their parishes.48

29 Wealth was a foundation of status, and it also provided economic power that could be converted into votes on election days. Merchants dominated the New Brunswick assembly before 1837, and the legislators who engaged in mercantile activities, ranging from the great merchants of Saint John to the timber merchants of the Passamaquoddy and the Miramichi to the country storekeepers of the Saint John River valley, had the economic status and influence to match their political aspirations.49 The merchants’ business ledgers, estate inventories, and mortgage records demonstrate the extensive economic power that they wielded over local residents due to their control of access to credit, supplies, timber, employment, and markets. This considerable economic power was often used to influence voters’ choices.50 In the 1785 election, for instance, Northumberland County’s sheriff, Benjamin Marston, attributed William Davidson’s electoral victory to his powerful economic influence, noting that he “has great influence over the People here many of them holding lands under him & many others being Tradesmen & labourers in his employ.”51 Economic coercion continued to influence the outcome of Northumberland County elections into the 19th century. After the 1828 by-election, for example, an observer wrote:Can it be but expected that men here, will use their influence as in every other quarter? Is it unfair or unreasonable if I have been under obligations to a merchant, I should oblige him by voting for his friend, when I have reason to think he knows the qualifications of a Representative better than I do, and has more interest in procuring a fit and proper one. Should it be expected that I would vote against the friend of a man who held a bond on my property, and could ruin me if he pleased.52

30 Attorneys were members of the one important occupational group in the New Brunswick assembly that did not consistently possess the economic prominence that most assemblymen achieved.53 As the colony’s earliest lawyers lamented, a legal career provided scant opportunity to acquire wealth in colonial New Brunswick. One of the colony’s most accomplished first-generation lawyers, Ward Chipman, Sr., complained: “There are so many other men in the profession that I find myself almost without any business at all and I cannot condescend to seek it.”54 To attain a measure of economic security, many of the colony’s lawyers focused their efforts on securing one of the colony’s few government offices. For example, Ward Chipman, Sr., successfully utilized his connections to imperial authorities in London to secure his appointment as New Brunswick’s first solicitor general.55 Second-generation lawyers often found considerable economic success by combining their legal practices with patronage appointments to fee-generating offices and mercantile activities. Lawyers Edward B. Chandler of Westmorland County and John W. Weldon of Kent County received appointments as clerks of their county courts and John A. Street profited from his legal training by serving as Northumberland County’s registrar of wills and deeds. All three were also involved in successful mercantile ventures.56

31 Although lawyers were often the least prosperous members of the assembly, they were often among its most influential leaders. A lawyer usually served as the speaker of the house of assembly, and lawyers chaired many of the assembly’s most important committees. The lawyers in the assembly possessed one important attribute that many other assemblymen lacked: education above the basic level of literacy. The education, professional training, and skills associated with their occupation were viewed as important qualifications for political office and often became more important bases for pursuing office than the wealth and economic influence that they might acquire from their legal practices.

32 Higher education generally was also relatively common among first-generation political leaders in New Brunswick, and Loyalists in particular possessed higher levels of formal education than most other first-generation assemblymen. In New Brunswick, seven of the original 26 members elected to the First Assembly (1785-1792) had earned degrees from American universities. The Harvard graduates included Jonathan Bliss (1763), Ward Chipman (1770), Daniel Murray (1771), and William Paine (1768). Amos Botsford (1763) and Daniel Lyman (1770) graduated from Yale, and William Hubbard earned a degree from King’s College of New York. In addition to the seven college graduates, John Saunders and Peter Clinch attended the College of Philadelphia and Trinity College, Dublin, respectively, although neither completed a degree.57

33 None of the succeeding ten assemblies, though, achieved the high educational standards set by the First Assembly. Despite the Loyalist leaders’ efforts to establish educational institutions in New Brunswick, few schools were organized during the colony’s first three decades. Although the colony’s first institution of higher education, the College of New Brunswick, was founded in 1785, persistent funding and personnel problems meant that it did not graduate its first students until 1828. The necessity of traveling outside the colony severely limited higher educational opportunities for second-generation New Brunswickers.58 Nearly four-fifths of those who served after 1792 did not receive any formal higher education. Overall, only one-eighth of New Brunswick’s assemblymen who served before 1837 attended college, and only one-fifth are known to have received any formal education beyond the basic level of literacy. Many candidates did not acquire even a basic education, a failing pointed out by an elector in 1795 who found it “inconceivable” that men “without even the advantage of a common School Education, should aspire to a Trust of this nature.”59

34 With this limited access to institutions of higher education, training in the professions – especially law – became a common supplement to or substitute for higher education for New Brunswick’s aspiring political leaders. Although a few assemblymen, including John Saunders and Ward Chipman, Jr., attended the Inns of Court in London, most of New Brunswick’s future lawyers during this era followed a reading program and clerkship with a lawyer practicing in the colony.60 Saint John assemblymen Ward Chipman, Sr., and Ward Chipman, Jr., were the most prolific mentors of future legislators. Ward Chipman, Sr., provided legal training for 13 students, including future assemblymen William Botsford and Thomas Wetmore as well as his own son, Ward Chipman, Jr.61 The nine students of Ward Chipman, Jr., included Robert Parker, Jr., Daniel L. Robinson, and George S. Hill.62 The only lawyer outside of Saint John to have a significant impact on the training of future political leaders during this period was Westmorland County assemblyman William Botsford, who oversaw the legal education of Edward B. Chandler, William End, and John W. Weldon.63 In British North America, formal education was not a prerequisite for success in most occupations (even law), yet the possession of formal education and professional training distinguished lawyers from the rank and file of colonial society.

35 For most New Brunswick assemblymen, accumulating a combination of appointments to local offices, wealth, and education were important steps on their paths to the assembly. Yet York County assemblyman John Allen lacked nearly all of these components. Allen was just 25-years-old when he won his first election in a competitive York County contest in 1809, becoming the youngest man to serve in New Brunswick’s assembly. Allen’s education was undistinguished. Although he had received a recent appointment as the captain of the First Battalion of the York County militia, his civil public service career was limited to serving in the parish offices of assessor and surveyor of highways. Allen’s economic activities were varied but often unsuccessful, and his sisters were continually rescuing him from his financial difficulties. Yet he was the only son of Isaac Allen, a prominent New Jersey Loyalist who served as a judge of the New Brunswick Supreme Court and as a member of His Majesty’s Council from 1784 until his death in 1806. John Allen’s status as the only son of one of New Brunswick’s most prominent Loyalist settlers was the key factor in launching a political career that included eight terms in the assembly.64

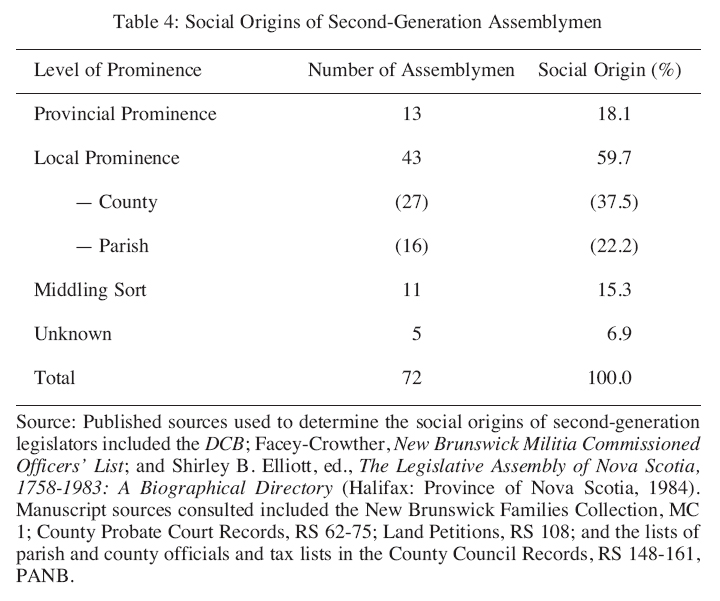

36 John Allen’s path to the assembly highlights the most important characteristic distinguishing second-generation New Brunswick assemblymen from their first-generation counterparts. Less than one-half of first-generation assemblymen were members of prominent families. But like John Allen, the majority of second- generation assemblymen had prominent social origins. Table 4 summarizes the social origins of second-generation assemblymen.65

Table 4: Social Origins of Second-Generation Assemblymen

Display large image of Table 4

37 More than three-quarters of New Brunswick’s second-generation assemblymen were members of provincially or locally prominent families. Nearly one-fifth of second-generation assemblymen were members of families who had attained prominence on the provincial level. These were the first families of New Brunswick – families whose members had managed to acquire the most important appointive provincial offices, serve in the assembly (often as its leaders), control substantial fortunes, and earn college educations. The fathers of the assemblymen in this category included two members of His Majesty’s Council, three Supreme Court justices, and nine assemblymen. The social origins of second-generation legislators George D. Robinson and Daniel Ludlow Robinson typify the members of this group. Their father, prominent Saint John merchant John Robinson, served as speaker of the assembly, provincial treasurer, and, like his own father Beverley Robinson, as a member of His Majesty’s Council.66

38 Assemblymen with locally prominent family origins constituted nearly three-fifths of second-generation legislators. More than one-third of second-generation assemblymen were members of families who had achieved prominence on the county level. The fathers of these 27 assemblymen were not only among the wealthiest residents of their parishes, but they also held important county offices (most notably commissions as justices of the peace). Eight fathers had served in the assembly, although they did not acquire leadership positions, and their influence remained primarily local in nature.67 The Morehouses of northern York County exemplified families of locally prominent standing. Assemblyman George Morehouse’s father, Daniel Morehouse, a Loyalist refugee who became a prosperous general merchant in Queensbury after the war, was the most prominent public servant in his parish. Beginning in the 1780s, he served as parish clerk, overseer of the poor, surveyor of highways, and commissioner of highways for Queensbury parish. He later received appointments to the county magistracy and county militia that confirmed his standing as a member of York County’s elite.68

39 Slightly more than one-fifth of second-generation assemblymen were members of families who achieved prominence on the parish level. Lemuel Wilmot of Lincoln, Sunbury County, was the father of three assemblymen and the grandfather of a fourth. He was the wealthiest man in his parish and held the most prestigious parish offices, including overseer of the poor, commissioner of roads, and assessor.69 His position was comparable to that of 15 fathers of other second-generation assemblymen – men who were often among the wealthiest and most prolific officeholders in their parishes, but who did not attract the notice or favour of the provincial executive who bestowed all county offices.

40 Given the high proportion of second-generation assemblymen who were members of locally or provincially prominent families, family connections were important elements of many second-generation assemblymen’s paths to the assembly. Forty-one of the seventy-two second-generation assemblymen had fathers, fathers-in-law, or uncles who served in the assembly. Overall, at least three-fifths of New Brunswick assemblymen had at least one other close relative who served in the assembly during its first half-century. In later assemblies, it was not uncommon for a legislator to have two relatives as fellow assemblymen.

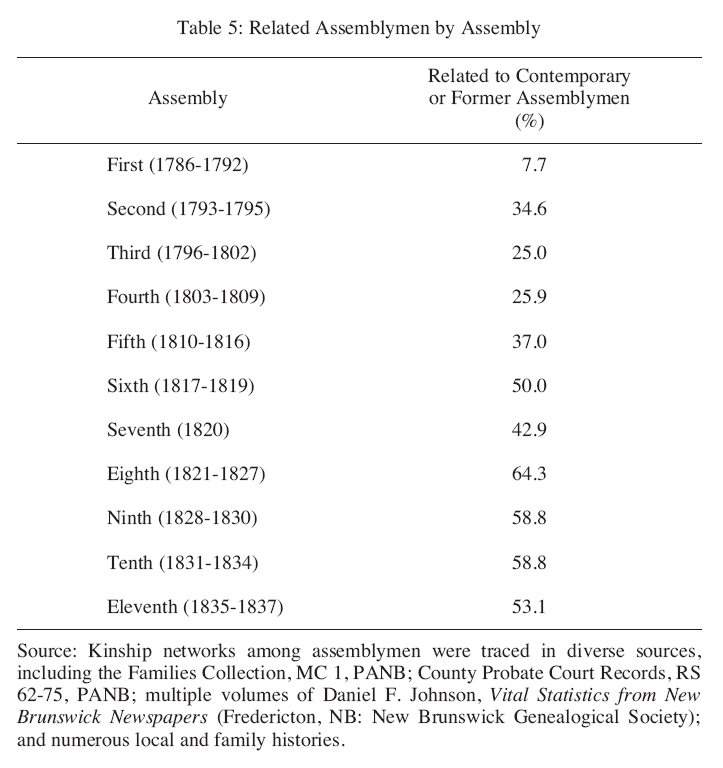

Table 5: Related Assemblymen by Assembly

Display large image of Table 5

41 As Table 5 indicates, the proportion of legislators in each assembly who were related to contemporary or former legislators increased steadily during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Two brothers, Robert Pagan of Charlotte County and William Pagan of Saint John, were the only relatives who served together in the First Assembly. By the mid-1810s, however, approximately one-half of the members in each succeeding assembly had at least one relative who served at the same time or in an earlier assembly. The proportion of New Brunswick assemblymen who were related to former and contemporary assemblymen increased steadily through the 1820s. The proportion of interrelated legislators declined slightly only after the assembly’s membership was expanded by six seats with the creation of three new counties between 1827 and 1834, which saw men without family connections to previous legislators initially win the new counties’ assembly seats.70 The assembly’s relatively small size and the fact that number of representatives per constituency did not increase between 1785 and 1827 contributed substantially to the consolidation of political power in relatively few families in many New Brunswick constituencies.71

42 Across colonial British America before and after the American Revolution, officeholders regarded elective offices as possessions that could be passed on to their male heirs.72 Thirty-six fathers and sons, twenty-five fathers-in-law and sons-in-law, and twenty-two uncles and nephews won seats in the New Brunswick assembly before 1837. Fathers and sons rarely served in the same assembly.73 One-third of the sons captured their fathers’ assembly seats in the elections held immediately after their fathers’ deaths or retirements. After the death of Westmorland County assemblyman Amos Botsford in 1812, the county’s voters unanimously elected his son, William Botsford, to fill his assembly seat. Other assemblymen treated their assembly seats as possessions that they could assign to their sons during their lifetimes. In his speech after his re-election to represent Sunbury County in the colonial assembly in 1820, Elijah Miles noted that he had been uncertain whether to stand for election again “as his utmost wishes tended to the advancement of his son [Thomas O. Miles] to this important office.” Miles decided to contest the election when “only on the day of the election did he hear that his son could not possibly return from Miramichi in time.”74 In the next provincial election, held in 1827, Thomas O. Miles was present at the Sunbury County polls and his father did not run. The voters elected the elder Miles’s son in his place. A similar case occurred in Queens County in 1816 when John Yeamans, who had represented the county since the assembly’s first session in 1786, retired, and his son, Richard Yeamans, replaced him. And in its account of the 1827 election in Saint John City, the New Brunswick Courier noted that “Mr. [John] Ward . . . steps into his father’s shoes.”75

43 If fathers lacked sons with political ambitions, they could preserve political power within the family circle by sponsoring the political careers of their daughters’ husbands. Twenty-five fathers-in-law and sons-in-law served in the assembly before 1837. The most influential father-in-law was Charles Dixon, a Methodist who migrated from Yorkshire in the 1770s and who represented Westmorland County in the First Assembly. Although none of Dixon’s three sons chose to seek their father’s seat in the assembly, two of his daughters and one granddaughter married future assemblymen, all of whom settled in Westmorland County after 1790. Dixon’s daughter, Elizabeth, married physician Rufus Smith (a Saint John native); Dixon’s daughter, Martha, married Methodist minister Benjamin Wilson (a member of a Virginia Loyalist family). And Dixon’s granddaughter, Susan Dixon Roach, married William Crane, a native of Horton, Nova Scotia, who moved to New Brunswick and became a prominent Westmorland County merchant. Through their marriages, these Westmorland County newcomers gained access to and no doubt benefitted from Charles Dixon’s local political, economic, and religious influence as they pursued their political aspirations.76

44 Family connections with former assemblymen provided tangible and intangible social, economic, and political advantages for New Brunswick’s second-generation political leaders as they launched their careers. Family capital and connections were invaluable as farmers and merchants established the successful businesses that would support and advance their political careers.77 Kinship networks were also critical to beginning careers in the professions. Becoming a successful attorney in colonial New Brunswick depended more on family connections than it did on aptitude for the law because leading Loyalist attorneys worked together to ensure that their sons and the sons of other respectable Loyalist families received legal training and were admitted to the New Brunswick bar.78 Family recommendations also helped secure appointments to the county offices that served as key steps on the path to the assembly. Because personal recommendations from those already in office influenced colonial executives’ decisions on appointments to county civil and military positions, having family members in positions to make recommendations was another important advantage that the majority of New Brunswick’s second-generation officeholders enjoyed.79 Moreover, relatives with previous political experience provided a base of knowledge about local electoral conditions and potential supporters that would be essential for first-time candidates.80 Having a relative with legislative experience was an important advantage when launching a political career, a finding perhaps best summarized by the fact that on average, sons of former assemblymen were almost seven years younger than other assemblymen when they were first elected to the assembly.81

45 During the late 18th and early 19th century, New Brunswick assemblymen followed paths to the assembly that conformed to pre- and post-Revolutionary British American standards. For New Brunswick’s first- and second-generation assemblymen, like their counterparts across British America, their paths commonly included securing appointments to important local civil and military offices and accumulating wealth and economic influence. Although a majority of New Brunswick’s first-generation assemblymen were not members of prominent families, they took advantage of opportunities during the American Revolution and resettlement in New Brunswick to enhance their status and power, and many first-generation assemblymen were remarkably successful in consolidating and transferring these assets to their political heirs. By the time that New Brunswick’s second generation of elected political leaders was entering the assembly during the 1810s and 1820s, prominent social origins and the family connections that accompanied them had also become important components of electoral success.82 The increasing importance of family connections in securing offices and accumulating wealth, combined with the limited expansion of assembly membership, had a profound impact on the emerging character of representative government in colonial New Brunswick. These developments contributed to the consolidation of political power and the formation of local oligarchies that would dominate electoral politics in many constituencies across colonial New Brunswick.

Notes