“Delinquents Often Become Criminals”:

Juvenile Delinquency in Halifax, 1918-1935

Michael BoudreauSt. Thomas University

Abstract

During the early part of the 20th century, juvenile delinquency in Halifax was perceived to be a serious social and moral problem that had to be solved without delay. Consequently, between 1918 and 1935, many of Halifax’s criminal justice officials fully embraced most facets of Canada’s modern juvenile justice system in order to deal with the local juvenile delinquents. By utilizing this new regulatory regime (notably the juvenile court and probation) to grapple with juvenile delinquency, Halifax was in the forefront, along with other cities, of the efforts to regulate and criminalize the lives of primarily poor, working-class children and their families.Résumé

Au début du 20e siècle, la délinquance juvénile à Halifax était perçue comme un sérieux problème social et moral qu’il fallait résoudre sans tarder. Par conséquent, entre 1918 et 1935, de nombreux représentants de la justice pénale de Halifax endossèrent pleinement la plupart des facettes du système judiciaire moderne du Canada applicable aux jeunes afin de prendre des mesures contre les jeunes délinquants de l’endroit. En faisant appel à ce nouveau régime de réglementation (notamment le tribunal de la jeunesse et le système de probation des jeunes) pour lutter contre la délinquance juvénile, Halifax était à l’avant-plan, aux côtés d’autres villes, des efforts visant à réglementer et à criminaliser la vie d’enfants essentiellement pauvres et issus des milieux ouvriers, ainsi que de leurs familles.1 THE CENTRAL GARAGE ON GRAFTON STREET in downtown Halifax had been the site of two thefts in the spring of 1923. A 14-year-old boy came to the service station twice and asked for a few cents worth of gasoline. While the attendant on duty carried out his requests, the young boy emptied the cash box, once getting $5 and the following week getting $13. When the boy returned for the third time, however, a “representative of the law was lying in wait” and caught him in the act.1 This boy was part of Halifax’s “juvenile delinquent class.” In an effort to explore this “class” of children, this article will examine the attitudes of social reformers and experts regarding juvenile delinquency as well as the city’s juvenile delinquents themselves during the 1918-1935 period: their home life, the crimes that they committed, the treatment accorded them by the police and the juvenile court, and how the community viewed these youthful lawbreakers.2 The 1918 to 1935 period was chosen for two reasons: Halifax experienced a series of socio-economic changes during these years that heightened many residents’ anxiety over crime and juvenile delinquency and, secondly, in response to the perceived threat that crime posed to social order, efforts were made during these years to improve how the criminal justice system in Halifax handled boys and girls who committed such acts.

2 Juvenile delinquency in pre-1950 Canada, and how girls and boys were dealt with by the law on the basis of their gender, class, and ethnicity, has been explored in seminal works by Joan Sangster, Tamara Myers, and Bryan Hogeveen among others.3 However, there is a dearth of studies on juvenile crime in Halifax specifically, and in the Maritimes generally. Sharon Myers’s article on the Boys’ Industrial Home in interwar Saint John remains one of the key scholarly assessments of the experiences of juvenile delinquents in the region.4 This article is a case study of how the Maritime’s major urban centre framed the issue of delinquents and crime and how its juvenile justice system dealt with them. It also underlines how criminal justice history and the history of childhood and the family can enrich one another. Historians of the family and childhood, Neil Sutherland has noted, have taken into account “such matters as the effects of geographical and institutional location, and of gender, class, religion, race, and ethnicity, on children and families.”5 But the criminal law must also be included in this lexicon of analysis. As will be demonstrated here, an assessment of the implementation and interpretation of the law, and the apparent causes of delinquency, can help to uncover how some children were viewed and treated by the juvenile justice system and by middle-class society in interwar Halifax.

3 The years from 1918 to 1935 were tumultuous ones for Halifax. The city underwent a dramatic and disruptive social and economic transformation. As a result, many Haligonians viewed crime as something that could potentially threaten their personal safety along with the moral and social order of the city. Within the context of this fear of crime, as Peter King and Joan Noel have argued, juvenile crime acquired an added significance. This was due mainly to the widespread belief, in Halifax and elsewhere, that children represented the future of society. And if too many boys and girls became delinquents then the possibility of them turning to a life of crime as they grew older increased, which placed the progress and stability of society in jeopardy.6

4 In order to try to prevent this from occurring, to counteract contributing factors such as urbanization and city life generally, and to help instill within juvenile delinquents a respect for lawful authority, a campaign arose in Halifax between 1918 and 1935 to modernize the city’s criminal justice and juvenile justice systems. This process of modernization included the hiring of policewomen, utilizing the latest in crime-fighting technology (such as finger-printing), and the opening of a juvenile delinquents court. This court would deal specifically with boys and girls who had breached the provisions of the Juvenile Delinquents Act of Canada (1908); its establishment was also a recognition that children who broke the law must be treated differently than adult criminals. To do otherwise, many felt, would be to doom these young people to a life of further hardship and criminal activity.7 Thus this article, in providing a case study of juvenile delinquency in Halifax, not only broadens the analysis of juvenile delinquency within the region but also demonstrates how there was, within Halifax’s juvenile justice system, a gradual, but important, transition from traditional to more modern ways of classifying and dealing with children who had committed crimes.

5 According to some newspapers and juvenile court judges, Halifax had a “juvenile delinquent class” lurking within its midst. Most contemporaries, however, were quick to distance this “delinquent class” from the more general criminal element. To have viewed juveniles as the same as adult criminals would have made the problem of juvenile delinquency, in the outlook of those dedicated to juveniles’ reformation, more serious. For their part, judges did not want to condone the actions of these delinquents by handing down a lenient sentence. But they also wanted, at the same time, to try to prevent these youths from becoming “hardened” criminals. As a compromise, most delinquents in interwar Halifax received some form of punishment and/or rehabilitative care. Similarly, many progressive social reformers, and those generally concerned with crime, the implementation of justice, and the maintenance of social order, considered youthful offenders to be worthy of reform. There thus emerged signs of Halifax’s justice system employing modern methods of dealing with juvenile delinquents.8 These methods, which were practised in several Canadian cities, included treating juvenile offenders as separate from adult criminals, attempting to improve the environmental factors – notably the home and educational milieus – which contributed to children’s delinquency, and utilizing a system of probation to monitor their activities.9

6 These techniques of dealing with children who had broken the law were enshrined within the Juvenile Delinquents Act. This act, which also created juvenile delinquents courts, provided a blue-print for the treatment of delinquents – one that envisioned them as distinct from adult offenders and as individuals who should receive care and training rather than a harsh punishment. As the act stated: “The care and custody and discipline of a juvenile delinquent shall approximate as nearly as may be that which should be given by its parents and that as far as practicable every juvenile delinquent shall be treated, not as a criminal, but as a mis-directed, misguided child and one needing aid, encouragement, help and assistance.”10 Proponents of child welfare also had as a goal the defence of society. They wanted to ensure that children would not grow up to become paupers, drunkards, or criminals. By so doing, they hoped to improve not only their world, but the world that their children would inherit. For those children who did come into contact with the law, the Juvenile Delinquents Act – with its emphasis on the rehabilitation of the child within a family-like environment – provided what many felt would be the best remedy for “problem children.”11 Armed with a set of powers and institutions to “correct rather than punish the delinquent” and “to set the child on the pathway to a better future,” the act entrenched a new category of crime in early 20th-century Canada.12

7 The act also signalled the emergence of a new conception of the “child” in child welfare and criminal justice discourse. Indeed, the Juvenile Delinquents Act formally distinguished children as separate legal entities from adults.13 As one contemporary legal scholar said in 1924 of the act’s outlook towards children: “Children are children even when they break the law, and should be treated as such, and not as adult criminals. As a child cannot deal with its property, so it should be held incapable of committing a crime strictly so called.” Children, in other words, practised their own brand of criminality. In the matter of rehabilitation and detention, the act’s decree that “no child . . . shall be held in confinement in any county or other jail or other place in which adults are or may be imprisoned, but shall be detained in a detention home or shelter used exclusively for children” gave legal sanction to the distinct needs of children.14 By defining a “child” as a boy or girl under the age of 16, the act acknowledged that these early childhood years marked a particular stage of development for a person. These years were a window of opportunity for the justice system to steer delinquents away from a life of crime.15 In the case of Halifax, juvenile justice officials relied upon a two-tiered institutional structure in order to achieve this goal: the juvenile court, which owed its creation to modern notions of judicial practice, and the reformatories, which combined a progressive initiative to reform delinquents with a 19th-century emphasis on denominational and gender segregation. In this sense, reformatories in interwar Halifax continued to serve as moral guardians for children.

8 In certain respects, delinquents posed a more critical problem for the preservation of law and order than did adult criminals. In the minds of those who were concerned with the welfare of children and/or the preservation of law and order, criminal tendencies started with the young. To prevent the spread of juvenile crime, criminal justice authorities believed, would be to help stem the tide of adult criminality. Across North America, late 19th- and early 20th-century social reformers, juvenile court judges, medical experts, and social workers looked to poverty and inadequate parental care and education as the main causes of delinquency. In conjunction with the state, these “child savers” instituted a host of measures, including child labour laws, compulsory school attendance, and training for mothers in the proper care of their children – all of which were designed to improve the lives of youths.16

9 All of these social reform and criminal justice initiatives for juvenile delinquents implied a new degree of state regulation over the lives of mainly poor, working-class children and their families. But the degree of legal agency that the Juvenile Delinquents Act bestowed upon children was rather hollow since the criminal justice system, and by extension the state, did all that it could to restrict the activities and the lives of “problem” children. In this sense, by criminalizing much of the behaviour characteristic of poor, urban youth, juvenile delinquency – in North America and Europe – was “legislated into existence,” imposing a strategy of power or a “morality of domination” upon children, their families, and civil society.17 The institution entrusted with this power was the juvenile court. The Halifax Juvenile Court, which led the fight to “save” juveniles from a life of crime, was established in February of 1911, following the proclamation in Nova Scotia of the Juvenile Delinquents Act.18 As one of the first locations for a juvenile court in Nova Scotia, and indeed in Canada, Halifax apparently suffered from a serious problem with juvenile delinquency.19 Overseeing the administration of juvenile justice in Halifax during the years 1918 to 1935 were four judges: W.B. Wallace (1918-1919), who was the first judge appointed to the juvenile court in 1911; Dr. J.J. Hunt (1919-1925); E.H. Blois (1925-1933); and W.W. Walsh (1933-1935).20

10 In the minds of many child welfare advocates, the juvenile court, whether it was in Halifax or elsewhere in Canada, had to be a “child saving station” – a place where children were shown guidance so that they could become a “citizen saved to the state.” The court also had to be an “intelligent instrument for the defence and protection of the unfortunate victim, rather than a tool of retribution and destruction.” And perhaps most importantly, the juvenile court had to be not a “place to punish children, but [a place to] help and protect them from themselves and others.”21 This emphasis upon “maternal justice” became a hallmark of juvenile courts in Canada and an extension of state authority into the lives of mainly working-class children and families. Besides a judge, the Halifax Juvenile Court employed a probation officer. Probation was another form of social regulation for many children in Halifax. J.E. Hudson, the city’s probation officer, spent much of his time keeping a close watch over young offenders who had been released on probation. In addition, Hudson, like many probation officers, could influence the outcome of a case. Before a case came before the court, the probation officer investigated the relevant details and then recommended to the judge, bearing in mind the best interests of the child in question, how the case should be handled. In other words, the probation officer could help to determine whether or not the court would give the accused a suspended sentence, place them on probation, impose a fine, or sentence them to a reformatory.22 The juvenile court also worked closely with the Children’s Aid Society of Halifax, the police department, and local reformatories to help curb the growth of juvenile crime and ensure the reformation of delinquents.

11 In Halifax, the “youth” who drew more attention from social reformers and juvenile court officials were boys rather than girls. Halifax, like other major cities in interwar Canada, grappled with a “boy problem.” In essence, as Tamara Myers has demonstrated, delinquent boys – more so than girls (who were seen to embody moral delinquency) – were considered to be in danger, rather than dangerous. As a result, many felt that boys could be reformed.23 Although the “boy problem” was socially constructed by the media and some juvenile justice officials, it was nevertheless seen as a crisis that demanded immediate attention from the juvenile court and Halifax society. As one writer to the Morning Chronicle in 1929 stated, with proper care and supervision, boys could be redeemed for society as “the money now expended in importing undesirables from Europe might better be employed in establishing reformatory institutions for the reclamation of the youthful law breakers of our own country.”24 Bryan Hogeveen has demonstrated that efforts to solve the “boy problem” were part of a larger scheme to control the politically weak and maintain existing class relations.25 In Halifax’s case specifically, a solution to the “boy problem” would also allow the city to preserve its aura of middle-class respectability and social order.

12 As Karen Dubinsky notes, crime, whether adult or juvenile, affects not only the criminals and the victims, but also the reputation, well-being, and prosperity of the entire community.26 This was certainly the case for Halifax. From 1918 to 1935, in the aftermath of the Great War and the devastation wrought by the Halifax explosion, the city, in an effort to secure social order, actively sought to control criminal activity. The application of the criminal law was thus dictated in part by those who deemed law and order to be essential to social stability and harmony. While many Halifax residents, especially the middle class, believed that crime occurred in their city, they also felt confident that law and order could ultimately prevail. Chief of Police Frank Hanrahan echoed this belief at the beginning of 1923 as part of his department’s New Year’s pledge to the city. The Halifax Police Department, Hanrahan declared, shall “preserve the King’s peace in . . . Halifax, [it will] run down lawbreakers and keep this city as it is today, one of the most peaceful and secure in the dominion of Canada.”27 Hanrahan’s reference to the “King’s peace” underscores the city’s dedication to social order and to a “legal environment” within which the state and the criminal justice system strove to control crime.28

13 At the end of the First World War, Halifax was a rapidly changing city. In 1920 the “new” Halifax, as seen through the eyes of “One Who Knew It In The Old Days,” was a thriving metropolitan centre where people attended the theatre, stores overflowed with merchandise, businessmen poured money into the local economy, and the waterfront had apparently lost none of its lustre.29 But this buoyant view of the city concealed the dire economic conditions that beset Halifax’s economy and adversely affected some residents. For example, a plan to build steel ships on the waterfront had faltered by the end of 1920, which caused unemployment to rise and wages to fall.30 Similarly, Halifax’s industrial-based economy had begun to crumble. Once the federal government had reduced protective tariffs and the East-West freight differential, many of the city’s industries could no longer maintain their competitive edge. Between 1921 and 1931, the number of workers in manufacturing fell from 2801 to 2508. Although manufacturing did not disappear in Halifax, it could not keep pace with growth outside the region and the output of durable goods for export began to collapse.31

14 The high wages and job security that had returned for some workers by the late 1920s quickly vanished with the advent of the Depression. As the economic climate worsened in the late 1920s and early 1930s, poverty became a way of life for more and more Halifax residents. A 1932 housing report, commissioned by the Citizens’ Committee on Housing, found that 11,197 men, women, and children lived under circumstances of “bad housing.” These included “woefully meagre” bathing and sewer facilities, yards littered with garbage, and an overall degree of uncleanliness. As well, adequate lodging for a family of five at a cost of $20 per month – the affordable level of rent calculated by the report – was nearly impossible to find in Halifax.32 As County Court Judge W.B. Wallace asserted, adequate housing put a working man and his family “in the best class of citizens [which] makes him a staunch upholder of law and order.”33 Without such housing, however, so the argument went, working-class families, particularly their children, became more susceptible to the lures of crime. It would not be until at least 1935, with renewed state funding and building contracts, that Halifax exhibited some signs of escaping from the clutches of the Depression.34

15 While most of the city’s middle-class populace avoided the economic ravages of the late 1920s and early 1930s, they still feared that dire economic conditions would undermine social order. As one writer in the Halifax Herald stressed, “We must aim to be as splendid in civic life and order as in material greatness.”35 To this end many citizens of Halifax placed a strong emphasis upon building a city of order, and a campaign arose in Halifax from 1918 to 1935 to modernize the city’s machinery of law and order – particularly the juvenile justice system, the police department, and the penal system – to meet the challenges posed by crime during this period. Part of becoming that city of order was dealing with crime, and nowhere was the dilemma of crime in Halifax seen to be more serious for social order and the city’s future stability than with regards to juvenile delinquency.

16 The Halifax Juvenile Court stood as a testament to a more modern approach to juvenile crime and delinquency. This more modern approach had first appeared in Nova Scotia in 1890 with the passage of the Act to provide for the Reform of Juvenile Offenders. As part of this legislation, any boy under the age of 16 who was found guilty of breaking the law could be sentenced to a reformatory rather than to a county jail, where he would have been housed alongside adult criminals.36 In this sense, the Halifax Juvenile Court represented a continuation – and a refinement – of the province’s earlier attempts to tackle juvenile delinquency. This was a significant development, and the establishment of juvenile courts in North America has been heralded as one of the notable innovations of the Progressive era. Some of its supporters even considered the juvenile court to be an instrument of “social betterment” – not only for children, but for society as a whole.37 Similarly, the entire juvenile justice system, Tamara Myers contends, was considered to be an improvement over adult courts because it was intended to operate on the principle of treatment rather than punishment.38 The Rev. C.L. Ball saw the need for a specialized procedure for treating juvenile offenders. Writing in the Halifax Herald, Ball believed that lumping juvenile and adult criminals together only “tends to confirm the criminal in crime.” Instead, Ball argued, “we should not treat a juvenile . . . as we would an adult offender.” To remedy the situation, Ball proposed that less “severity of punishment” and more supervision be applied to children through probation. Only by regulating their lives, maintained Ball, could children who broke the law be “saved . . . as good citizens.”39

17 The architects of the juvenile court in Halifax no doubt felt the same way. The Nova Scotia Society for the Prevention of Cruelty had spearheaded the drive for a juvenile court and laws that would protect the interests of children. Members of the organization also felt that parents should shoulder more of the blame for their children’s delinquent ways.40 In this sense, it was hoped that the juvenile court would hold parents accountable for any part that they may have played in contributing to their children’s delinquency as well as neglecting them. The government tried to meet the society’s demands, but government officials also realized that a juvenile court would not be an ultimate panacea for the problem. Commenting in 1918 on the recently tabled report of the superintendent of neglected and delinquent children, the province’s Attorney-General, Orlando Daniels, insisted that a juvenile courtis not a complete remedy, or cure-all, for crime. It is not, and cannot be, a substitute for parental care, moral and religious training and good environment. . . . It is not really a court for deciding cases, but rather a bureau of practical justice, and a “clearing house” where conditions of juvenile delinquents are adjusted. It is not so much a method of investigation with a view to the punishment of a delinquent act as a remedy for conditions from which the delinquent act probably arose.The government created the juvenile court, Daniels continued, because “every child [who has broken the law] has a right to a fair chance to become an honest, useful citizen.” Bearing this in mind, Daniels concluded that “the business of the court is to search out the underlying causes of juvenile delinquency and to supply preventive measures.”41 Hence the prevention of juvenile crime and delinquency became a cornerstone of Halifax’s newly created juvenile justice system.

18 The Halifax Juvenile Court dealt with wayward children by classifying them into two categories: “neglected” and “delinquent.” Neglected children included those whose parents had failed to provide or care for them and who had suffered accordingly. If uncared for, court officials believed, these children would soon become delinquents. In cases where the court found parents guilty of neglecting their children, or contributing to their delinquency, the judge could impose a fine of up to $500, or imprisonment for one year. As Judge W.B. Wallace commented: “I have had occasion to enforce a fine more than once with good effect.”42 Delinquents, on the other hand, were those juveniles found guilty of deeds that would be deemed criminal if the perpetrators had been 16 years of age or over. Some of these acts included truancy – “the forerunner of many great offences,” according to Judge E.H. Blois – as well as petty theft, damage to property, and mischief. Judges had the discretion to suspend a child’s sentence if they felt it to be in his or her best interests. This, judges hoped, would give young offenders an opportunity to forsake their deviant ways. And if they considered the conditions in a child’s home to be a hindrance to his or her reform, the judge could send them to a reformatory.43 The average length of stay for children in a reformatory tended to be two years, but some did receive indefinite sentences. As one commentator said about Judge Hunt, he imposed sentences “not as punishment, but as an aid towards building up character.”44 It was expected that juvenile court judges, like Hunt, would embody masculine virtues of honesty and moral character and thus serve as role models for young boys to help them change their delinquent ways. Indeed, character-building was considered to be one way to reform wayward boys.45 The Halifax Juvenile Court, and its judges, represented one attempt on the part of judicial officials and the state to rehabilitate a segment of the city’s criminal element. Some feared that as soon as juveniles became adults, all chances of “rescuing” them would vanish and the criminal justice system would have to deal with these older lawbreakers as it saw fit.46

19 To avoid this eventuality, reformatories in Halifax, in accordance with some of the prevailing attitudes towards young offenders, tried to advance the lives of the girls and boys placed in their charge. Adhering to the belief that children, boys in particular, should be taught a trade, receive food “suitable for a growing boy,” and fresh air while under institutional care, juvenile reformatories in Halifax set out to turn delinquents into respectable and productive citizens. The juvenile justice system in Canada, according to Joan Sangster, was charged with the task of re-moulding children’s values. Children who had run afoul of the law, so it was thought, had apparently rejected parental guidance and formal schooling, along with respect for social order. In addition, delinquent girls (and some boys), were seen to lack sexual and moral decency.47 This process of re-moulding children was also gendered. As “citizens-in-waiting,” boys needed to learn respect for familial and community authority, private property, and a work ethic. As one writer in 1929 emphasized, “If anything permanent is to be done for [the] average man, it must be done before he is a man. The chances of success lie in working with the boy, not the man.”48 Girls, however, had to be taught how to be decent, moral wives and mothers. And, in general, juvenile delinquents required protection, discipline, and self-control.49 Juvenile court judges in Halifax had this formula firmly in mind when they sent the young people brought before them to the city’s industrial schools and reformatories.

20 During the 17-year time span covered in this article, four institutions handled the majority of the commitments from the Halifax Juvenile Court. While the juvenile court and the penological philosophy underlying these reformatories was rather new, the system itself still relied on traditional agencies (such as the church), and methods (notably segregation), to achieve its ends. Clinging to their 19th-century roots, all of these institutions were organized according to religious affiliation and gender. The Halifax Industrial School and the Saint Patrick’s Home cared for Protestant and Roman Catholic boys respectively, the Monastery of the Good Shepherd housed Roman Catholic girls, and Protestant girls had to travel to the Maritime Home for Girls in Truro. Private organizations managed the two Protestant homes, while the Christian Brothers operated St. Patrick’s and the Sisters of the Good Shepherd tended the monastery. Each institution underwent a regular state inspection and received per capita grants from the provincial treasury for each child committed by the juvenile court.50 All of these institutions dedicated their efforts to reclaiming for society the wayward children who had been placed under their guidance.

21 The Halifax Industrial School epitomized this initiative. Founded in 1863 by a “number of public spirited citizens,” and incorporated two years later, the school was described by one of its superintendents, H.O. Eaman, “not [as] a place of punishment nor a prison in any sense of the term, but a training school where boys because of circumstances, usually over which they had no control, have become a community problem, receive the instruction and training best adapted to mould and perpetuate good character, establish habits of industry, and impart knowledge that will fit them to take their places in the community when their course of training is completed.”51

22 Eaman and his successor, the Rev. W.D. Wilson, a former pastor of the Central Baptist Church, along with their colleagues, hoped to accomplish this task by combining class-room instruction in the “general precepts of the Christian religion, the power and goodness of God, and lessons of morality and virtue” with training in carpentry, farming, and some basic academic subjects. The boys who were sent to the Halifax Industrial School often came from poor homes, which were considered to be lacking in parental discipline. In the words of the superintendent, the boys “come from homes very near to the poverty line – from homes where parental rule has lost its authority. There has been no authoritive rule in their lives and they have drifted into trouble.” The purpose of the industrial school, the superintendent concluded, “is to correct if possible these early defects.” Some of these boys quickly settled down and adjusted to their new life in the school, but the “majority who are sent here are little rebels and refuse for a time to recognize any authority.” “Our business,” Wilson continued, “is to help these boys to become good citizens” for the benefit of themselves and society and for the maintenance of social order.52

23 The efforts of the Halifax Industrial School to reform neglected and delinquent boys highlight the practical, if not modest, approach that the juvenile justice system adopted for some juvenile delinquents. The school officials felt that vocational rather than “bookish” training for boys would be their “salvation” and set them on a path to become “independent, self-respecting, useful [citizens] and turned away from wasted years of vagrancy and crime.”53 As Frederic Sexton, Director of Technical Education for the Province of Nova Scotia, observed in 1930, most of the boys in the Halifax Industrial School were either truants or “mild” delinquents. And, according to Sexton, “this class of adolescent was a potential criminal. They almost always come from a bad home environment.”54

24 Sexton also considered them to be “victims of . . . poverty . . . cruelty, neglect . . . or other unfortunate circumstances for which they were not responsible.” Only a few of these boys were “mentally defective, vicious, or asocial and will probably not be redeemed by any system of education.”55 The majority, in Sexton’s mind, “have a high enough order of intelligence to be satisfactorily trained for useful occupations.”56 To this end, in 1930 the Halifax Industrial School began a series of instructional classes in woodworking, shoe repair, and printing. Over the course of the next five years, until 1935, Sexton praised the progress that was being made by these boys. They were described as “keen and zealous workers,” some of whom had already secured positions as apprentices. For Sexton, this was “most gratifying.”57 This portrayal of these boys as helpless victims who were to be pitied and assisted is in keeping with other images of boys in cities such as Montreal. By socially constructing these boys in this manner, they appeared to be in danger rather than being dangerous. This made the “boy problem” seem to be less daunting and more manageable, if not solvable.58

25 St. Patrick’s Home for Catholic boys functioned along similar lines as that of the Halifax Industrial School. Opened by the Catholic Church in 1885, and incorporated in 1925, St. Patrick’s cared for delinquents committed either by the juvenile court or the boys’ parents.59 The boys attended school for five hours a day and also received manual training, art lessons, and “physical instruction.”60 While not ideal homes, these reformatories still provided delinquent boys with a degree of comfort some may have never known and which these boys would certainly not have received in any of Halifax’s adult prisons.61 Moreover, these reformatories demonstrate, despite their drawbacks, the importance that those in the juvenile justice system placed upon diverting children away from a life of crime.

26 Those Roman Catholic girls who strayed to the wrong side of the law underwent their reformatory treatment in the Monastery of the Good Shepherd. Built in 1892, the monastery fell under the guidance of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd. Trained in rescue work and offering “experienced and sympathetic supervision,” the sisters opened their doors to “lost” and convicted girls, in addition to some women, usually unwed mothers, found guilty of minor offences. All of the monastery’s inmates encountered a strict regime of educational and practical instruction. Academic lessons continued up to grade six, while industrial classes gave every girl the opportunity to learn a host of gender-specific tasks: sewing, knitting, crocheting, dress-making, and domestic science.62 While some may have welcomed the opportunity to work in return for their lodging, the education and training they received would not provide most with the necessary means, upon their release, to escape a life of poverty or prescribed gender roles.63

27 Protestants in the Maritimes responded to the need to reform their own delinquent girls with the Maritime Home for Girls. Built in 1914, the home cared for and educated those Protestant girls between the ages of seven and sixteen years deemed to be “incorrigible or delinquent.”64 The home provided the girls under its care with moral discipline and practical instruction in most “branches of household science” to help ensure that they became “worthy” members of society.65 Despite one estimate that 50 per cent of the girls were “definitely mentally abnormal,” members of the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene, which surveyed the home in 1920, found residents to be “happy and industrious.” “There can be no doubt,” the committee members added, “that girls leave this institution very much better than when they entered, and it is a model for similar organizations of its kind in Canada.”66 Thus in Halifax, juvenile delinquents did have recourse to a system of reform unavailable to most adult criminals sentenced to the city’s jails and prisons. Children, it seems, warranted specialized care. But those beyond the age of childhood innocence who had committed crimes, many criminal justice officials concluded, did not deserve the same treatment.

28 Despite the reform impetus of these institutions, the legal framework provided by the Juvenile Delinquents Act, and the progressive underlying notions about delinquency and the child, juvenile crime remained a serious problem for legal authorities in Halifax. The struggle that those within Halifax’s juvenile justice system waged against delinquent crime from 1918 to 1935 underlines this fact. A comment made in 1912, one year after the opening of the Halifax Juvenile Court, provides some indication of what criminal justice officials and social reformers were up against in the battle against juvenile delinquency. Bryce Stewart, who in that year had conducted a preliminary social survey of the city, remarked in his report: “Much of our juvenile delinquency can be traced to community apathy with regard to such matters as the employment of children in street trades, the sale of trashy literature, the presence of children upon the streets at night, lack of training in sex hygiene, and failure to provide recreational facilities. The number of older persons contributing to juvenile delinquency in Halifax is quite alarming.”67 From this collection of social ills sprang what P.F. Moriarty, a member of the Halifax Prisoners’ Welfare Association, called the “juvenile delinquent class.”68 Halifax’s chief of police made similar references to juvenile delinquents. In his 1921-1922 annual report, Frank Hanrahan found juvenile crime to be a “difficult problem to handle at the present time,” especially with regards to break-and-enters in homes and stores throughout the city. “Every effort,” Hanrahan assured his superiors, “has been made by this Department to control criminals of this class and age,” but nonetheless a number of youths had appeared before the juvenile court during the past year. “It would seem necessary therefore,” Hanrahan continued, “that some system be devised whereby youths of this class could be given more personal attention and more earnest efforts made by the Government to redeem such youths before they have been able definitely to enter upon a career of crime.”69

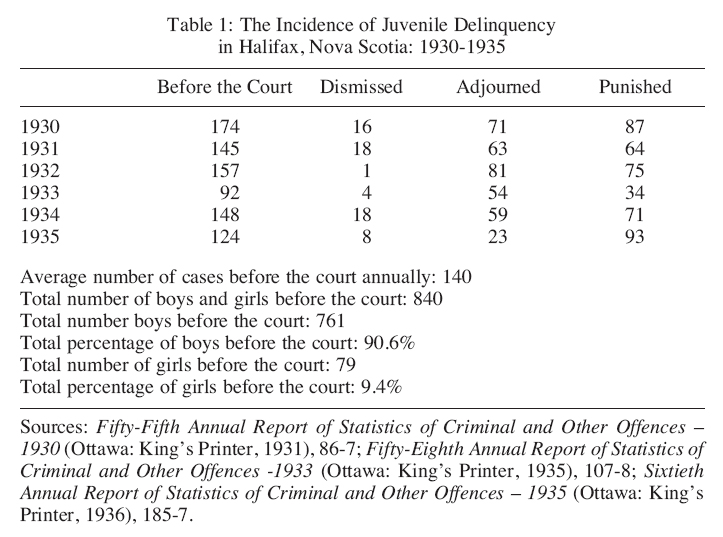

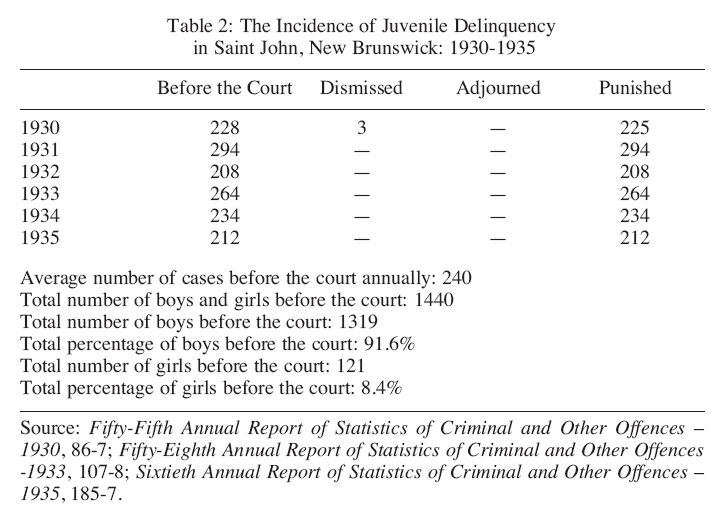

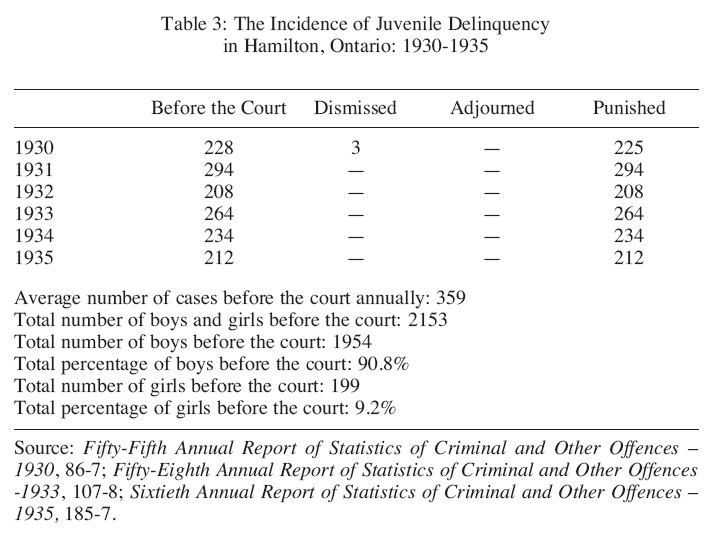

29 Officials of the Halifax Juvenile Court pursued this goal with mixed results. Between 1930 and 1935, for example, the court handled an average of 140 cases annually. In half of these cases (50.3 per cent), the court convicted and subsequently punished the offenders, while 42.2 per cent of the cases were adjourned and the remaining 7.5 per cent were dismissed (Table 1). Punishments ranged from a sentence in a reformatory to a fine or to probation, but all of these punishments were also meant to keep children out of jail and provide them with proper guidance to escape a life of depravity and criminality. The high percentage of adjournments is open to interpretation. It does seem to indicate that the juvenile court did not function as efficiently as local officials had hoped it would. Moreover, the court may have been forced to adjourn cases because of the inability of the police to gather sufficient evidence against the accused. In addition, adjournments may have allowed the court time to probe the backgrounds of both the children and their parents to strengthen the case against them and/or to determine a suitable sentence. The state, in other words, tried to monitor the lives of some parents and their children beyond the scope of the courtroom.70 This perception of local justice officials’ reluctance to punish most acts of juvenile criminality in Halifax is underscored by comparing what happened in Halifax with what took place in some other Canadian cities. For the same 1930 to 1935 period, for instance, the juvenile court in Saint John, New Brunswick, meted out punishments to all but three of the 1440 cases before it (Table 2). In Hamilton, Ontario, a similar pattern appeared: the Hamilton Juvenile Court passed sentence on 90.3 per cent of the cases it heard during these years, dismissed 5.8 per cent and adjourned 3.9 per cent (Table 3). While none of these cities could likely claim to have had a more serious crisis with juvenile crime and delinquency, these figures point to the fact that the juvenile justice system in each city differed in the approach that officials felt to be most appropriate in tackling this situation and ensuring that delinquent children did not continue to engage in criminal activity.71

30 The sex composition of the “juvenile delinquent class” in Halifax mirrored that of known adult criminals. Boys far outnumbered girls in the crimes reportedly committed by juveniles. From 1930 to 1935, 90.6 per cent of the total number of delinquents who appeared before the Halifax Juvenile Court were boys (Table 1). And much like their older counterparts, juveniles engaged in a host of major and minor crimes. In 1922 for example, the Halifax Juvenile Court registered 81 convictions for major offences and 59 for minor infractions. Theft and “house-breaking” comprised the bulk of the major offences, while the minor offences ranged from truancy, stone throwing, trespassing, and shouting in public, to coasting on the street.72 Convictions for major offences usually resulted in the offender being sentenced to a reformatory while those children found guilty of committing minor offences would often be placed on probation or simply released. Although these minor offences were at times depicted as examples of boyhood exuberance, the fact that the law classified them as illegal attests to the state’s desire to regulate the lives of mainly poor, working-class children.

Table 1: The Incidence of Juvenile Delinquency in Halifax, Nova Scotia: 1930-1935

Display large image of Table 1

Table 2: The Incidence of Juvenile Delinquency in Saint John, New Brunswick: 1930-1935

Display large image of Table 2

Table 3: The Incidence of Juvenile Delinquency in Hamilton, Ontario: 1930-1935

Display large image of Table 3

31 This need for regulation and close supervision of children surfaced in particular around the question of truancy. In the opinion of Judge Hunt, truant children “soon become delinquent and delinquents often become criminals.” Thus every effort had to be made, Hunt asserted in 1920, “to fasten on the minds of our boys the advantages of a clean life and high ideals.”73 Included among these “high ideals” was the importance of staying in school. Yet convincing every school-aged child in Halifax of the virtues of attending school on a regular basis proved to be an impossible task.74 The truant officer’s annual reports document the never-ending war he and the juvenile court waged against children who failed to come to class. The figures for the number of children apprehended for truancy fluctuated from a high of 301 in 1919 to a low of 40 in 1924 and, for the years 1918 to 1935, an average of 121 children were reported annually for truancy.75 According to government officials, the truancy law in Halifax was “carried out very efficiently.” “Persistent” or “habitual” truants were tried before the juvenile court, with most being given a suspended sentence for their first offence along with a card, which their teachers had to sign, indicating that they had attended class. Each child had to then report to the truant officer every Saturday and show him his or her signed card. If this system of surveillance was ineffective, then the “truant” was committed to a reformatory.76 A.H. MacKay, the province’s superintendent of education, felt that the truancy law should also be amended to include a system of fines that could be levied against truants’ parents. Under his proposed scheme, a set amount of money would be assigned for each day that a child was absent from school and then a bill would be sent, periodically, to their parents. Under this plan, in MacKay’s words, “the whole onus of proof of necessity of absence [is] thrown upon” the parents.77

32 Officials cited poverty, “street trades,” and lack of parental guidance as the causes of truancy. Truant Officer Anderson noted in 1921 that a “great many” children did not attend class, particularly during the winter, because they did not own adequate clothing and boots. The parents of these children, most of whom Anderson believed to be unemployed, could not afford to clothe their children and thus kept them at home. That same year, Anderson granted permits to 51 boys and 14 girls, all over the age of 14, to leave school for part of the year to work to supplement their families’ incomes. He repeated the practice the next year and then stopped, no doubt in response to pressure from juvenile justice officials to keep children in school.78 This underlines the hardships some families endured during the early 1920s in Halifax. It also raised doubts about the effectiveness of imposing fines upon parents as a way to combat truancy.

33 Family poverty meant that some children turned to the streets in order to earn a living. In 1923, an editorial in the Halifax Herald declared that too many children could be seen begging on the city’s streets. By giving to these children, the Herald editorial claimed, people made it “very profitable for our younger citizens to become expert in lying and probably stealing. . . . Surely conditions are not so bad in Halifax that our babies are forced to beg! . . . There can be no doubt that by encouraging these children . . . we are giving them the very worst training for good citizenship.”79

34 Selling newspapers in downtown Halifax also prevented children from going to school. According to Judge Blois, newspaper selling tended to be the most common cause of truancy, and the money boys earned from this trade was usually spent, without their parents’ knowledge, on candy and movies. Other boys, Blois maintained, used this job as a front for begging. When someone bought a newspaper the boys would ask them for an extra nickel.80 Other boys worked such long hours that it could not help but affect their performance in school. One 12-year-old boy, for instance, sold papers before and after school and then worked in a bowling alley until midnight. He eventually came before the juvenile court for neglecting his school work. “Such boys [in] street trades,” decried Judge Hunt, are “exposed to undue temptation, their work interferes with their school studies and they are brought into contact with undesirable adults at an age when they are not able to withstand such evil influences.”81 As was the case in other cities, officials in Halifax felt that boys who worked in, or roamed, the streets, were often the unsuspecting victims of “bad company” who usually led them astray.82

35 To overcome the dilemma of truancy and its concomitant ills, judicial and state officials called for the punishment of parents and the strict supervision of children. In 1919, and again in 1922, the court summoned a number of parents to explain why they had allowed their children to remain at home. Most could not provide the court with a satisfactory answer and were thus handed fines of $5 or $10.83 Some parents told the court that they did not have the money to purchase new clothes and boots for their children to wear, but occasionally judges expressed little sympathy for their plight. In one case a woman could only send her son to school after she had borrowed a pair of boots for him to wear. She was fined $5 for previously allowing her son to loiter on the streets during school hours; however, the court also held that the boy did not have to attend classes until he received a new pair of boots.84

36 In addition to punishing parents to help prevent truancy, the city also tried to closely monitor the activities of children. Section 927 of the Compulsory Attendance at School Act gave a truant officer the power to arrest without warrant any “truant or absentee child found wandering about the streets, or other places of resort.”85 Halifax City Council as well took aim at “street trades” involving children after receiving numerous complaints about minors selling newspapers in downtown Halifax. In January of 1932, council drafted a set of amendments to Ordinance 21 – “Petty Trades” – designed to keep children off the streets. The amendments, in part, stated: “No newspaper shall be sold on any street of the City . . . by any person under the age of twelve years after the hour of eight o’clock in the evening.”86 Similar restrictions were put in place in some American cities. By 1915, 30 states had outlawed boys from selling newspapers and engaging in other street trades.87 Reformers and the juvenile justice system in Halifax seemed determined not only to eliminate truancy, but also to ensure, by limiting their activities on city streets, that children did not succumb to the temptations of crime.

37 Their efforts, of course, did not always prove successful. The outbreak of more serious crimes among the city’s youth sparked fears of successive juvenile crime waves. In May of 1923, for instance, the police commented on the exceptional number of juvenile “misdemeanours” occurring in the city. The police spent much of their time answering calls from irate citizens about their lawns being torn up, flower pots destroyed, and windows broken. The Herald attributed some of this vandalism to the arrival of spring when youthful spirits, pent up during the winter, sought release, and added these words of wisdom: “Parents who desire to protect either the morals or safety of their children, will do well to see that they are not allowed to play or roam promiscuously about the streets.”88 From breaking windows to theft, it seemed to many residents that juvenile crime had not subsided in interwar Halifax. In sentencing two fifteen-year-old boys to indefinite periods in a reformatory, Halifax Juvenile Court Judge Hunt characterized them as two of the most desperate young criminals he had ever dealt with during his career on the bench. The boys reportedly had taken great delight in telling the court about the several robberies that they had staged. Had they not been apprehended, the Morning Chronicle insisted, their spree of crime would have continued unabated.89

38 September of 1924 also saw another juvenile crime wave, and within a 24-hour span the police had brought in an “unprecedented” number of young boys, some under the age of ten, to the police station for questioning in relation to various unsolved crimes in the city. Two brothers admitted to stealing $2 from a hardware store and three pencils and two mouth organs from Cleveland’s bookstore, both on Gottingen Street. Another boy, arrested for nabbing a woman’s purse, received a two-year sentence in the Halifax Industrial School. According to the Halifax Herald, Halifax was “in the midst of a juvenile crime wave.”90 This “juvenile crime wave” resulted in a vigorous debate regarding the best course of action to take in order to solve the problem of juvenile delinquency and, as a means of addressing the city’s “juvenile crime wave,” reformers and criminal justice officials turned to modern arguments and schemes for dealing with neglected and delinquent children. Most agreed on a distinct set of origins for juvenile delinquency: “1) Complete lack of parental control and discipline. 2) Neglect which is the result of extreme poverty, obliging both father and mother to go out to work and leave the children all day to do as they like. 3) Poor and squalid living in the streets with their evil lures, [and] 4) Lack of Religious Training.” The vital importance of children to society, Judge Hunt insisted, meant that if parents could not care for them then the community and the state had a responsibility to do so. In this vein Hunt favoured the construction of supervised playgrounds as the “best means of keeping down juvenile delinquencies” and the opening of a juvenile library as a “powerful factor in promoting their welfare.”91

39 The Halifax Herald, while endorsing this general assessment of the causes of juvenile delinquency, laid much of the blame on parents. An editorial in the paper attributed the “lamentable looseness in the behaviour of an increasing number of young people” in Halifax to the “inefficiency of home training.” “Parental authority,” the editorial continued, “has become very much weakened. Children are allowed to ramble about the streets day and night. If they have any inclination to mischief they are likely to find congenial companions, and the steps from stealing fruit, injuring fruit trees and other not very serious offences to house-breaking are easily made.”92 The large number of people near the age of 20 in Canadian penitentiaries, the Herald editorial concluded, “is evidence of the rapid progress which youngsters can make in crime.” The Herald’s editorial writer’s belief that children would grow up to be criminals if something was not done to guarantee their wholesome upbringing was shared by many within Canada’s juvenile justice system.93 This environmental view of juvenile delinquency found favour amongst other local social activists. J.B. Feilding, Chairman of the Halifax Prisoners’ Welfare Association, in a speech before the annual convention of the Union of Nova Scotia Municipalities in 1924, argued that crime among adults began at an early age. This, he said, reflects a “weak spot in our system of moral reformation.” Feilding urged his audience to look to repeat juvenile offenders “for the start in crime and the cure to some extent.”94 For former Halifax Juvenile Court Judge Wallace, “Juvenile delinquents are not born, but made.” Delinquency could be traced, he emphasized, to “defective home conditions involving, as a rule, shameful carelessness or moral obtuseness of a parent.” Moreover, the “strong temptation, environment and mis-directed energy” of the city created a “boy problem.” Indeed, many child welfare advocates argued that city life seduced young people into crime and immoral behaviour.95 In Wallace’s opinion, only religious instruction could guarantee the proper development of a boy, for without “training of the will . . . to direct the will towards good, and away from evil, then the education of the boy is a failure.”96

40 Alongside the rhetoric associated with the care and reform of juveniles and the prevention of delinquency, there also arose a more specific discourse around the “boy problem” in Halifax. The “boy problem” was a symbol of the growing presence of boys in public spaces – a presence that, if it could not be removed from the city’s streets, had to be regulated.97 Moreover, for many social welfare experts and criminal justice officials, the image of children and the future their parents were to bequeath to them was decidedly male-oriented. The “boy,” not the “girl,” held the promise of the future.98 As a result, in Halifax at least, boys under the age of 16 received more attention than girls when it came to the problem of juvenile crime and delinquency and its solution. In an editorial entitled “The Boy’s Value,” the Halifax Herald decried the lack of funds allocated to the protection of boys because the city spent nothing more than the cost of school administration for its “boy population” (estimated in 1920 to be 7, 500). In contrast, the city allotted more than $150,000 for the fire department. “It does look as though,” the Herald announced, “we thought more . . . of our houses than of the boys who dwell within them.” The editorial also indicated that “if an effort at all comparable to that which protects our buildings from fire were made by the community to save our boys,” then there would be fewer cases appearing before the juvenile court. The editor could only hope that the day would come when people would place a greater value on boys than on real estate.99

41 Two years later, in 1922, a representative of the Halifax Police Department maintained that its members were making a special effort to keep boys out of trouble. “Every boy is worth one chance,” remarked Chief Detective Horace Kennedy, in reference to the number of boys the police interrogated but never formally charged. Kennedy himself often brought first-time offenders to his office, questioned them, and then released them with a warning. In most cases, said Kennedy, it set the boys “on the right track . . . [as] a talking to with the threat that on future occasions treatment will not be so light” usually deterred them from any further mischief. A similar practice of police and probation officers dealing informally with boys who had been detained for mischievous behaviour was common in Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, and Vancouver.100 This helped eliminate the need for many more formal, and perhaps lengthy, court proceedings.

42 The “boy problem” was also often seen to be solvable with the right balance of moral and social reform. Speaking at a luncheon meeting of the Halifax Commercial Club in 1924, Father Charles Curran, President of the St. Mary’s Boys Club, called for greater interest in boys’ work and a more concerted effort on the part of all public-spirited men to give the destitute boy the chance in life he deserved. Many boys in Halifax, Curran asserted, had to leave school and work to support their families. This deprived boys of the opportunities they needed to succeed. Without these opportunities, Curran maintained, boys often had little choice but to resort to crime. Curran thought that Halifax should provide boys with more recreational facilities to occupy their idle time. If given the means to work and develop, in Curran’s opinion, most boys would become “valuable citizens.”101 In addition, the absence of moral development in under-privileged boys was also seen by Curran as contributing to their criminality.102

43 While not all of the suggestions for stemming juvenile crime and reforming youthful offenders came to fruition in Halifax, the general idea of leniency rather than corporal punishment, as espoused by Detective Kennedy, did become a common element of local judicial practice. A 1934 editorial summed up this situation: “It has been noted with much satisfaction that there is a growing tendency among our [juvenile court] judges . . . to be lenient with youthful first offenders, and that the brand of a conviction or sentence is not to be lightly imposed. . . . We think in many cases, perhaps in most cases, that this treatment will have better effect than a sentence, or even a remand.”103 Children who broke the law could be and deserved to be reformed and their lives renewed for their sake and for the advancement of society; this was the view held by many middle-class social reformers and judicial authorities in Halifax.

44 Juvenile delinquency was the one law-and-order issue in Halifax around which a consensus seemingly prevailed. Crime among adults, many thought, originated in their childhood years. Keeping juvenile delinquents from becoming professional criminals would thus deal a decisive blow against the proliferation of crime in the city. In the pursuit of this goal, making sure children stayed in school by attacking truancy and passing laws designed to regulate children’s public lives was an important plank in Halifax’s social reform platform for juvenile delinquents. For its part, the Halifax Juvenile Court served as the conduit for the administration of delinquents and, by sentencing children to local reformatories, placing them on probation, or giving them a reprimand, the court and its judges – in attempting to be lenient with juvenile delinquents – acted as paternalistic overseers of errant children in Halifax.104 The importance of children to the future development of the nation also prompted members of the Halifax juvenile justice and social reform communities to debate the steps needed to solve juvenile delinquency, of which the “boy problem” was one part, with the hopes of putting a stop to juvenile crime and turning these young criminals into productive members of society. Similarly, the city’s attitude towards the “juvenile delinquent class,” notably the boys who belonged to this so-called class, often through no fault of their own, does suggest a sense of optimism about the redeemable nature of some criminals in interwar Halifax. These developments in the approach to juvenile delinquency in Halifax not only meant that criminal justice officials and child welfare advocates had embraced most facets of Canada’s modern juvenile justice system, but also that Halifax was at the forefront, along with other Canadian cities in the interwar period, of the efforts to regulate and criminalize the lives of primarily poor, working-class children and their families.

Notes