Articles

Between Community and State:

Practicing Public Health in Cape Breton, 1938-1948

Sasha MullallyUniversity of New Brunswick

Using the experiences of a Nova Scotia Public health nurse, Phyllis Lyttle, this article shows how practical considerations and local needs largely defined rural public health work in the early years of the provincial system (1938-1948). Examining public health reports and community narratives reveals how Lyttle expanded her role to include primary care and midwifery services – a role similar to that of a late-20th-century nurse practitioner – in response to the needs and expectations of the local population and the local general practitioner, C. Lamont MacMillan.

Cet article puise dans les expériences de Phyllis Lyttle, une infirmière de la santé publique de la Nouvelle-Écosse, afin de démontrer comment des considérations pratiques et des besoins locaux ont défini dans une large mesure le travail en santé publique dans les régions rurales durant les premières années du système provincial (1938-1948). L’examen de rapports sur la santé publique et de récits collectifs révèle comment Lyttle a élargi son rôle afin d’inclure les soins primaires et les services de sage-femme – un rôle semblable à celui des infirmières praticiennes de la fin du 20e siècle – en réponse aux besoins et aux attentes de la population locale et du médecin généraliste de l’endroit, C. Lamont MacMillan.

1 IN 1938 THE PROVINCE OF NOVA SCOTIA sent a public health nurse, Phyllis Jane Lyttle, to Baddeck, a small Nova Scotian community on the southern shores of the Bras D’Or lakes. As a new employee of the Cape Breton Island Health Unit, she arrived to set up a new provincial public health program and would work out of the county seat serving all of Victoria County. One of the first people she went to see was the local physician, Dr. Carleton Lamont MacMillan. The physician admitted in his autobiography published some decades later that he was rather abrupt and defensive when the tall young nurse announced herself at his office. “Miss Lyttle did complain to me (years later),” he wrote, “about the reception I gave her.” Her arrival was unexpected, and he was irritated to have had no notice from the provincial government or the division authorities in Sydney that a new public health program was set to launch in his district. After demanding to know how old she was, Dr. MacMillan shot several questions at the young nurse – asking about her qualifications and details of the public health program she intended to set up. He then summarily dismissed his new colleague to attend a patient.1 It was hardly an auspicious beginning.

2 It was left to the doctor’s wife to “soothe” the situation with the flummoxed Phyllis Lyttle. Over a cup of tea, Mrs. MacMillan offered Lyttle a room in their home until she found local accommodations. Despite the awkward first meeting, Lyttle eventually came to terms with the local physician and settled into her job. Both the work and the location agreed with her, and she spent just over ten years in Baddeck. But Lyttle quickly realized that coming to an accord with MacMillan would be crucial to her success: “If I was going to work in Baddeck I would have to set up terms of reference with someone. . . . The doctor and I developed a way of working together. It was not always agreeable to the Public Health department, but it seemed to work for us.”2

3 Phyllis Lyttle’s experiences in Victoria County – how she worked together with the physician to carve out a place for herself as a rural health care provider – occupy the pages that follow. Her work as a rural public health nurse speaks to a variety of historiographies, including the histories of public health, the history of nursing, and women’s history in Atlantic Canada. A collection of diverse sources generated by and about Lyttle’s rural public health work can provide scholars with a better understanding of these early public health workers, many of whom were women who found that they were required to manage a series of personal and professional challenges at the community level. These challenges, as we shall see, required that they manage tensions between community and state in the delivery of public health services – services conceived, managed, and funded by central provincial authorities but delivered in idiosyncratic ways at the local level. Lyttle spoke and wrote both publicly and privately about her work in Victoria County. Records of her activities form part of the Nova Scotia Department of Health’s records in the 1930s and 1940s. Lyttle’s memories of her work and commentary about her scope of practice are also extant in the private manuscript and oral history collection of Dr. C. Lamont MacMillan (Sr.), the well-known rural physician referenced above who worked in the same district to which Lyttle was assigned. Although this physician had a private practice in addition to his position as a local municipal officer of health, and although the Lyttle was a provincially employed civil servant, their medical work became intertwined over the ten years Lyttle spent as a public health nurse working out of Baddeck. Building upon the work of nursing historians, and historians who study the history of rural health care,3 this article will use Lyttle’s work as a case study to discuss the structures of power and authority at rural and remote bedsides in these early years of provincial public health expansion as well as the service overlap between private practice and local public health authorities. This case study will provide examples of how Lyttle negotiated rural community expectations, rural health needs, and state purview in the practice of public health in Nova Scotia. The records of her activities unequivocally point to the important place she and other public health workers played in the delivery of health services at this time. But there is also a clear disconnect between, on the one hand, the stated goals, scope of activities, and mandate of public health nursing and, on the other hand, how it was actually practiced in the community. This discrepancy requires examination.

A Brief Overview of Lyttle’s Career

4 The decade that Phyllis Lyttle spent in Baddeck was a relatively brief, but vibrant, chapter in a nursing career that spanned over half a century. Phyllis Lyttle’s career was also well-rounded, including hospital nursing as well as public health work, and she spent equal time in the field as a clinician as she did in the boardroom as a public health administrator. Although she may not have impressed Dr. MacMillan at their first meeting in 1938, she would finish her career as the superintendent of public health nursing for the province of Nova Scotia.

5 This was a precipitous rise for a woman from a modest rural background. Lyttle was born in Ellershouse, a small village in Hants County, Nova Scotia.4 After graduating from Windsor Academy High School, she took her training at Payzant Memorial Hospital School of Nursing (a hospital founded in 1905 in Windsor County).5 After her graduation in 1930, Lyttle’s career did not take the common career trajectory into private-duty nursing.6 Seen as one of the abler graduates in her class, Lyttle was offered a job on the wards of Payzant Memorial once she had earned her nursing cap. She lived in Ellershouse and worked in the hospital for eight years, joined there in 1933 by her younger sister Gertrude.7 The two sisters lived at home and worked together for almost six years until they parted company. Gertrude got married and moved to New York City, and Phyllis went off to Montreal where she earned a diploma in public health from McGill University. When she graduated from McGill in 1938, Phyllis Lyttle returned to Nova Scotia to take up a job as a public health nurse in Victoria County.8 For about a decade, from 1938 to 1948, she built up a provincial public health program. The first year or two her work seemed to take her through the entire far-flung expanse of the rural county district, up through the Bras D’Or Lakes to Ingonish and occasionally Cape North. But by 1940 Victoria County had split into two working districts, and Phyllis Lyttle focused her attention on the southern lakes region in and around Baddeck.

6 Lyttle, however, would not finish her career in Cape Breton. During 1948-49 she made the move from Baddeck to Halifax in order to take up a position as field supervisor for the Atlantic public health district, a regional service based in Halifax (a post she held until 1952). Lyttle then went back to school, this time at the University of Toronto, where she took post-graduate studies in public health administration. For the last 20 years of her career, she was superintendent of nurses for the Department of Public Health in Nova Scotia.9 Her accomplishments occurred during a period of public health expansion in Nova Scotia, and the pursuit of specialized training in the field of public health opened up significant opportunities for this ambitious woman – career opportunities that would hardly have presented themselves had she remained working on the wards of the Payzant Memorial in Windsor.10

Public Health Expansion in the 1930s and 1940s

7 The interwar period is an important era in public health history. Megan Davies has shown in her study of British Columbia that while public health expansion in Canada is generally a product of the post-war era, the interwar period was when the structure of the 20th-century system was established. Provincial public health activities during the Great Depression era cast a long shadow into the decades of federally funded prosperity to follow.11 Nova Scotia, for its part, had some catching up to do during these decades; by 1929, it ranked last in public health spending among provinces in Canada.12 As E.R. Forbes and others have shown, the Maritime Provinces had experienced an incomplete recovery from the post-First World War recession and funding for social programs in the region was scarce.13 Traditionally, any public health services in the province were funded and administered locally. Since the 1890s Nova Scotia had relied on a system of county boards of health, which in turn supervised boards organized at the municipal level (outside of incorporated towns and cities, these boards were organized by rural polling district). The province had also engaged in the fight against specific diseases like tuberculosis. In 1904 the province built a sanatorium in Kentville and, while this was a significant investment at the time, the sanatorium could only take a small percentage of the total number of Nova Scotian afflicted with tuberculosis; those who could not pay for hospital treatment were excluded as a matter of course.14

8 By the 1930s the Nova Scotian government was set to expand and organize public health services in keeping with public health reforms elsewhere in Canada and the United States.15 While the local and county boards had the power to offer a substantial range of public health services, the many boards lacked the means to hire specially trained staff and this resulted in an uneven, ad hoc system. One policy-maker in favour of adopting a more professional model of public health complained “most of the [county health boards] undertake little beyond elementary sanitary inspection and the enforcement of regulations regarding communicable disease control.”16 Licensed physicians carried out these tasks as appointed medical officers of health, and often these physicians were the local general practitioner, like Lamont MacMillan, who served the municipality of Baddeck and area for a number of years in this capacity while at the same time operating his private practice. Although the pay was minimal, often such activities injected much-needed cash into the coffers of local doctors who otherwise found they had to accept payment in kind – a sack of onions, some salt cod – for medical services rendered.

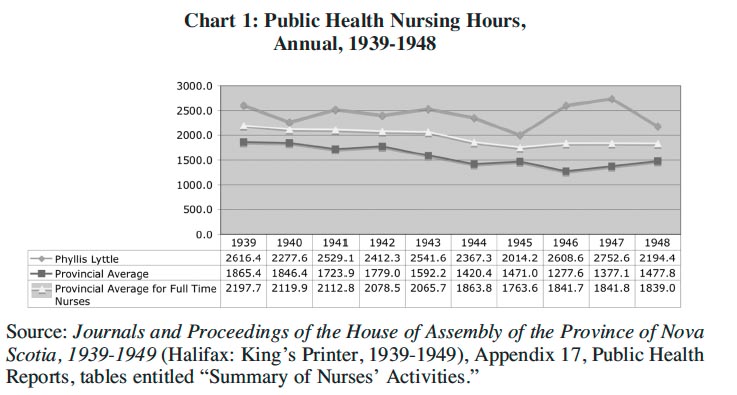

9 During the Depression decade, though, this was set to change as public health took a first step toward professionalization. In 1931 the public health administration in Nova Scotia was reorganized into a new Department of Health, whose primary responsibility was tuberculosis control.17 Then, in 1933, the Liberal government of Angus L. Macdonald was elected on a broad platform of social programs that promised to expand the purview of this new government office even further. The new premier believed in employing expertise to study social problems,18 and so the province appealed to the Rockefeller Foundation for help. The Rockefeller organization was heavily engaged in public health philanthropy at this time, and the new government saw an opportunity to have the Rockefeller team of experts survey health administration in Nova Scotia and make recommendations about its reorganization.19

10 Dr. W.A. McIntosh undertook the Rockefeller-sponsored survey, publishing his findings in 1935. The “McIntosh Report” recommended the provincial government create a system of public health services – one that would work in cooperation with the county and local boards but bring the additional monies of the province to bear in professionalizing public health. Rural physicians such as MacMillan would find their public health jurisdiction overlapping several municipalities. In 1935, 67 physicians were employed as medical health officers in Nova Scotia and all but one of these individuals were employed on a part-time basis for an honorarium of approximately $100 per year.20 Public health work, while it brought in some cash, was not a priority for the majority of these general practitioners. One public health official in Cape Breton pointed out that many such physicians were so busy managing their practices that it was “not to be wondered at” that they often neglected public health work, such as infectious disease notification, and other “details so essential to public health administration.”21 The other employees of the county boards, such as the sanitary inspectors, also worked part-time and carried out the most basic inspections of the milk and water supplies.22 Few boards outside of Halifax and the other large towns of the province employed public health nurses.23

11 From 1937 onward, the provincial government took steps to implement a parallel provincial program alongside this network of county, municipal, and regional boards. The aim was to expand public health education, maternal health services, and inoculation programs to bring down the death rates for infectious diseases, respiratory and digestive diseases, “conditions peculiar to the first year of life,” and maternal mortality. This new provincial program created and expanded a detachment of nurses specially trained in public health. All experts recognized that public health nursing activities were understaffed, and most authorities agreed that one of the serious weaknesses of the Nova Scotia system, including Cape Breton, was “too little public health nursing.”24 As provincial employees, these nurses were expected to offer a series of public health services directly to the population – services designed to reduce rates of maternal mortality as well as infectious diseases, particularly those afflicting children (with an emphasis on endemic problems like tuberculosis).25

12 The new provincial program would operate through a system of five public health units, each with a divisional health officer. The operation of tuberculosis and venereal disease clinics constituted a large share of the public health work at this time, but from 1938 to 1948, when Phyllis Lyttle was in Victoria County, Cape Breton, the department extended their activities substantially to include maternal and child health clinics, immunization programs, sanitary inspections, school health work, public health education, and what was delicately phrased as “the stimulation of better standards of service by the local health authorities.” The public health nurses worked under the supervision of a provincial superintendent of nurses, but reported directly to their divisional health officer. Their work varied, and cut across most of the programs listed above. Those nurses who worked in rural areas were expected to carry out school inspections and provide school nursing services.26 In this way the provincial public health nurses would work in the community, ideally with the local county public health personnel, but follow the dictates of the state-run service.

13 Cape Breton Island operated the first of these units, which was a pilot program of sorts for what would eventually be a province-wide system, and Phyllis Lyttle was among the very first nurses hired in Cape Breton. As might have been expected, the new provincial staff found that close cooperation with the municipal school nurses in Sydney and Glace Bay, with the Victorian Order of Nurses (VON), and the health officers employed by county and municipal boards of health was crucial to the success of the provincial programs, and therefore many aspects of the older administration of public health endured within the Cape Breton Island Health Unit.27 Not only did elements of the older administration remain operational at the same time the province expanded its new services, but the staff associated with the VON, the county boards, and municipal officers of health remained vital partners for the provincial public health service infrastructure. As Twohig observes: “Cooperation and mutual support between local and provincial authorities proved critical to the success of the programs during this implementation phase.”28

The Scope of Rural Public Health

14 But what did such cooperation entail in the day-to-day life of public health nursing? What kinds of accommodation did individual nurses have to make as they acted as the arms of the province reaching out into the counties to offer public health service? What had to happen at the grassroots level so that the practitioners, the communities, and the state could meet their needs and achieve their goals? These questions are difficult to answer because few first-hand accounts from the public health grassroots of this era have survived to the present day. While annual reports from field supervisors still exist, the reports from individual nurses based in the community have not, for the most part, been saved and archived. In Phyllis Lyttle’s case, however, we can use a variety of narrative accounts about her work to get a better idea of what scope of practice rural public health required and to understand how she garnered the authority to build a wide-ranging public health program in a remote rural county. A good part of this requires understanding her working relationship with C. Lamont MacMillan, the private practitioner who retained local responsibility for the county public health program.

15 According to MacMillan’s autobiography, Memoirs of a Cape Breton Doctor, Lyttle arranged clinics that accommodated the doctor’s schedule and, since supply lines from state to community were tenuous in these early years, he provided her with supplies from his own practice. Inoculation clinics occurred three times a year, during which time the pair would visit more than 50 schools in the 130 miles between Iona and Capstick. In his Memoirs MacMillan recounts how he and Lyttle quickly established a rapport, and Lyttle is quoted as saying that working with the popular country doctor became “a source of real pleasure, once I got started.”29

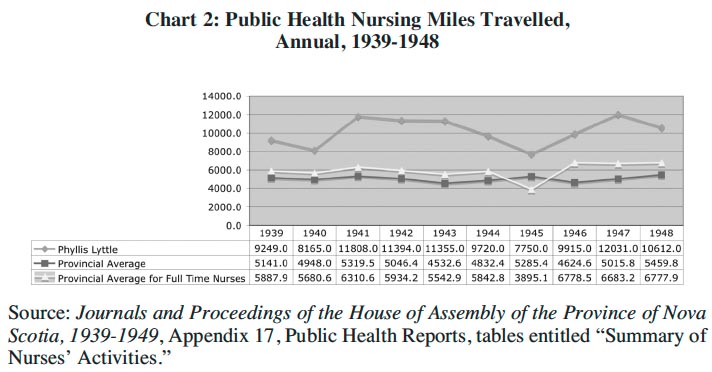

16 It seems, from the statistical records of her activities, that she got started quickly and was soon working at an extremely vigourous pace that she did not give up for a decade. The demands of rural public health nursing emerge clearly in a comparative statistical analysis of annual hours Phyllis Lyttle spent on the job and the annual number of miles she traveled. These data are then compared to other public health nurses working in Nova Scotia at the time.

Chart 1: Public Health Nursing Hours, Annual, 1939-1948

Display large image of Figure 1

Chart 2: Public Health Nursing Miles Travelled, Annual, 1939-1948

Display large image of Figure 2

17 The two charts show that Phyllis Lyttle worked more hours and travelled more miles on average than other nurses in the public health nursing service in Nova Scotia during the 1940s. Comparing her hours to the provincial average for other full-time nurses in Chart 1, she worked between 200 and 900 more hours a year than her counterparts elsewhere in the province. Overall, the number of average annual hours worked by public health nurses declined over this ten-year period, probably due to increases in staff (from 16 in 1938 to 25 in 1945 and 32 in 1949). Lyttle’s workload was not only consistently heavier, but she did not seem to benefit from the increase in staff. While it seemed her workload was adjusting to something closer to the provincial average during 1939-40, her hours on the job suddenly increased again in 1941 and levelled off until 1945. In 1945 her hours on the job once again seemed to be closing in on the provincial average for other full-time public health nurses, only to see another dramatic increase between 1945 and 1946. In 1947 Lyttle saw her busiest year – working a total of 2752.6 hours – which was more than twice the average number of hours worked by public health nurses in Nova Scotia and 45 per cent more hours than the average full-time public health nurse in the province.

18 The number of miles traveled in public health nursing work, captured in Chart 2, suggests that many of her on-duty hours were spent travelling. Here the numbers show an even wider gap separating the work of the exceptionally busy Lyttle from the provincial average of number of miles travelled by full- and part-time public health nurses and the average number of miles travelled by the other full-time public health nurses. In 1941, when she was still new to Baddeck, she travelled almost twice as many miles as the average for other full-time provincial public health nurses. Like the hours worked, the travel burden held steady for a few years, then decreased significantly to 1945. The travel would jump again in the immediately post-war years, to an all-time high in 1947. The fluctuations in her workload and travel raise interesting questions about workload distribution between nurses in the provincial public health service. It may well be that the travel imperative required of rural medicine accounts for the extra hours and miles. Nonetheless, Lyttle’s workload trends run counter to the provincial average between 1945 and 1949. The increase in both hours and miles over these years is a puzzle. Since it is unlikely that Lyttle would accumulate those hours and miles just doing immunization clinics and school inspections, a snapshot of the distribution of working hours offers further insight into the ways in which she organized her work differently from her other colleagues.

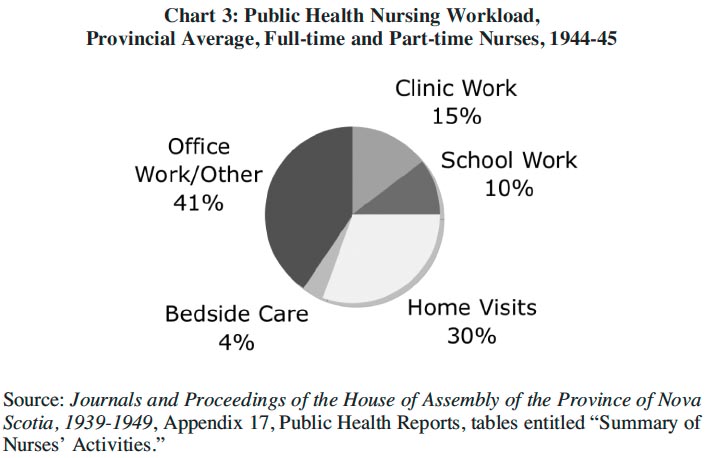

Chart 3: Public Health Nursing Workload, Provincial Average, Full-time and Part-time Nurses, 1944-45

Display large image of Figure 3

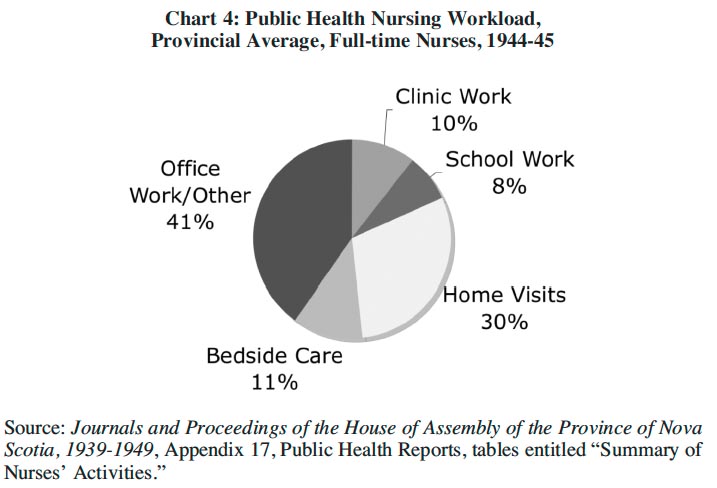

Chart 4: Public Health Nursing Workload, Provincial Average, Full-time Nurses, 1944-45

Display large image of Figure 4

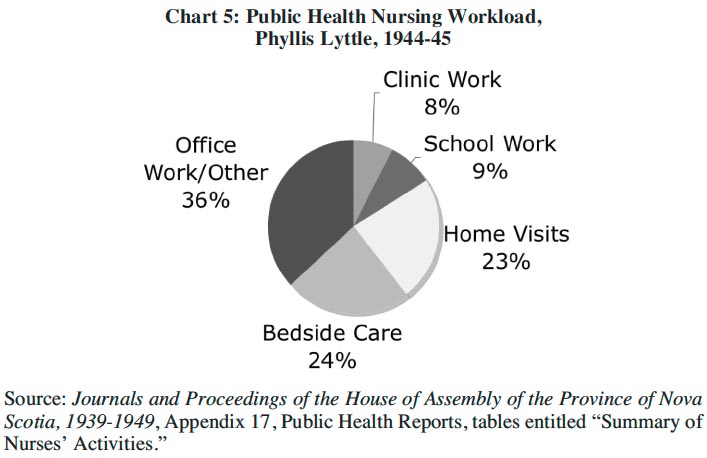

Chart 5: Public Health Nursing Workload, Phyllis Lyttle, 1944-45

Display large image of Figure 5

19 Charts 3 through 5 offer a breakdown of the hours spent in public health nursing during one of the years Phyllis Lyttle was in Baddeck. Of particular interest is the additional time Lyttle spend giving “bedside care.” While bedside nursing was not a significant part of public health nursing work overall (see Chart 3), it comprised a comparatively larger slice of the work done by the provincial department’s full-time nursing staff. And Phyllis Lyttle spent twice as much of time at the bedside as the average full-time public health nurse, even though she spent less time doing home visits.

20 Certainly the contours of rural nursing care were challenging in the interwar period. A 1943 Survey of Nursing conducted by the Canadian Nursing Association predicted a shortage of nurses in rural areas, mainly due to workload issues. Young women were unwilling to serve in these areas, the report claimed, because the conditions were more difficult and rural health work “frequently seemed to exploit the spirit of service a tradition upon which the nursing profession is based.”30

Nursing a Practice

21 The miles travelled and hours spent at the bedside – indicators of Lyttle’s “spirit of service”– are in many ways explained by narrative sources about her life and work. In MacMillan’s autobiography, we learn how, right from the outset, Lyttle agreed to go with the doctor on confinement cases although MacMillan noted “such duty was not called for as part of her service in the department of public health.”31 In his published Memoirs, the Cape Breton doctor credits her with being a “good sport” on several “hair-raising” travel adventures over mountains and across ice, through snowstorms and mud. It was a dramatic change for a woman who, before she came to Baddeck, had never traveled on an unpaved road.32 Far from being a reluctant traveler, several of MacMillan’s anecdotes indicate the young nurse was especially keen to attend childbirth, and resented the occasions when she was left behind. His Memoirs recount a story offered by Lyttle, for the purposes of his Memoir project, about a winter trip out to a country home:One Saturday night I gave up something I particularly wanted to do, went with the doctor to South Gut in the car, and then transferred to the sleigh with the doctor and Jimmie [McIvor, the doctor’s driver]. The horse went through the ice a couple of times near the shore, and we all had to get out to help him, each time getting wetter and madder. Then finally the doctor told me to go home; the sleigh was just too heavy with the three of us in it. I went home all right! I took the doctor’s car and I had no intention of going back to South Gut in the morning to pick him up. He could get home any way he liked. But his wife sort of made me feel that that wasn’t what I should do. I should go down and pick him up, so of course all was forgiven and forgotten in short time.33

22 There is certainly the impression, gleaned from the repartee written into MacMillan’s Memoirs, that the doctor and the nurse developed a collegial and sometimes even affectionate relationship. Here Lyttle is clearly teasing MacMillan about choosing his driver over the public health nurse, and the story relates her chagrin at the time at being left behind. It is noteworthy how the doctor’s wife once again steps in to “soothe” the tension between doctor and public health nurse, just as she did on the occasion of Lyttle’s arrival. One realizes from this, and most of MacMillan’s published stories, a clear sense of the limits of collegiality and of the hierarchy of authority in the clinical setting in country homes. However light-hearted Lyttle may have been recounting this story four decades later, at the time her second-class status was irritating. Since his horse and driver conveyed them to the bedside, MacMillan could choose his traveling companions and tell Lyttle to go home if he felt the method of transportation could not accommodate her. In a private practice the physician was in charge of determining not only the terms of care, but also the company he would keep when out on a call. The physician wanted above all else to arrive well-rested, and it seemed as though this concern overrode any need for clinical assistance. This anecdote indicates that when he was forced to make a choice, he would choose the driver MacIvor over nurse Lyttle. MacMillan considered himself the more important practitioner, and his comfort and keep were his primary considerations. For this reason, the gendered hierarchy also rarely allowed chivalry. Lyttle recalled that MacMillan could always “put one over” on her when there was only one bed available when they were waiting for a confinement case, because he always seemed to manipulate the situation to get a little sleep. Sometimes, Lyttle claimed, the doctor convinced the expectant mother to get up and walk so the labour would progress, and then he would slip in and take a nap in her bed. The demands of working with the physician in an assistant capacity seemed to physically exhaust Lyttle, but she ostensibly accepted the situation, saying, “If the nurse was going to go, she had to follow along and keep the same hours as the doctor.” In the Memoirs, though, she could not resist pointing out that she kept the same hours “without the benefit of those little naps.”34

23 Although initially suspicious of this public health nurse sent in by the province, MacMillan was able to partner with her and incorporate her services in support of his general practice. This doubtlessly went a long way toward easing any potential inter-professional tension from his perspective. Developing a working relationship with such a doctor, on the other hand, seemed to benefit Lyttle as well. She used this association to create a place for a public health regime alongside a general practice. Meryn Stuart has shown how the professional etiquette between rural doctors and public health nurses during the interwar period in Ontario ran along traditional gender lines. Nurses were encouraged to, and often did, make themselves available to local physicians in their district in order to smooth over any concerns over infringement of professional territory.35 It also provided the nurse, who was new to a territory, with a ready introduction into community lives and homes. Phyllis Lyttle remarked years later how useful it was that “we were always invited to all the weddings . . . the doctor and his wife and the public health nurse,” because that was where “we’d start to plan the prenatals!”36 Though offered as a humourous anecdote, Lyttle’s observation suggests how social engagement facilitated public health work, just as her work with the well-known local physician facilitated her social integration into the communities in Victoria County.

24 One should be careful, however, not to overstate the primacy of the physician in this relationship nor his centrality to all health care services in Victoria County. MacMillan’s Memoirs, while useful, leaves the reader with the strong impression that Phyllis Lyttle, in large part, eventually came to work for Dr. MacMillan more than she was employed by the provincial public health service. She accompanied him on house calls, and attended not only confinement cases but surgical cases as well. In many ways, MacMillan’s book depicts her as an obstetrical assistant as much as she was a public health worker. Other sources, however, suggest the relationship was more complex. An analysis of other primary sources suggest that Phyllis Lyttle eventually came to assert a good deal of independence in her public health work, and that she even came to play a role in the delivery of primary care.

25 In the manuscripts and interview transcripts in the physician’s research files – work that preceded his published autobiography – MacMillan is full of praise for the nurse. In these sources, he offers more details about their working relationship than in the Memoirs that ultimately went to press.37 Based on an interview he recorded with Lyttle in the early-1970s, MacMillan’s earlier manuscripts are full of anecdotes illustrating the ways in which she quickly became “a great help to [the] practice” when she arrived in 1938. Part of the problem that Lyttle helped to address, for instance, was that while obstetrical care was falling solidly under the purview of the typical general practitioners by the Depression decade, rural physicians like MacMillan were finding it difficult to keep up with the demands for this service: “In the earlier days . . . there were midwives. But midwives were becoming fewer and fewer and very often I had to rely on a neighbor to drop choloroform or to assist me.” Lyttle seemed to be a godsend to the overworked country doctor, who could rely on her clinical training to effectively monitor the condition of the parturient mother. “After she came,” he wrote, “ I certainly got a lot more sleep when we were on those long calls through the country.”38

26 The unpublished manuscript also contains many more stories involving Phyllis Lyttle than were ultimately included in the published autobiography. For one, the reader learns more about the challenges particular to rural medicine. Lyttle and the doctor managed not only to travel over broken ice, but had many logistical obstacles at the bedsides. They often worked, for example, in environments with no running water. They had to regularly manage the cold in poorly insulated country homes and sometimes found it necessary to take time to caulk and seal up drafts to avoid putting mother and newborn in danger from exposure to wintertime cold. Lyttle also had many scrapes and accidents over the years in Victoria County, and some are captured as adventurous travel tales in MacMillan’s Memoirs. Most of these occurred in winter, and Lyttle suffered exposure on one occasion that left her frostbitten. And some of the challenges would have a lasting effect on Lyttle’s health. After inhaling 16 ounces of chloroform from an accidentally dropped bottle, Lyttle developed a chest cough that posed an acute problem for a year – a problem that recurred periodically for the rest of her life. Finally, possibly because she was seldom able to partake of the little naps that supported MacMillan, she found it difficult to manage chronic fatigue. The physician relates with some sympathy how she bore the greater strain during a few occasions over the years. In the winter of 1941, for example, the doctor and nurse delivered three difficult confinement cases spread over 72 hours. Lyttle returned home from this marathon and collapsed. She would lie in bed in full dress for close to two days trying to recover from the ordeal, until her landlady found her and woke her long enough for a meal.39

27 In addition to details of the hardships either shared or managed alone, MacMillan’s manuscript reveals Lyttle’s expanded clinical capacities as a result of her years in Baddeck. Some stories highlight Lyttle’s growing independence and an evolving role in community maternal care of far greater importance than that of an obstetrical assistant. As the following extract describes, by the mid-1940s she was delivering many babies on her own:In the early hours of the morning of December 31, 1946, I got home from the north country about three o’clock. My wife told me that Miss Lyttle, the nurse, had gone out to Chris (Bentinck) MacRae’s on a confinement case and she was expecting me to go out as soon as I got home. I said, “Look, I’ll just lie down on the couch here for about five minutes. She’ll likely be calling in soon.” I had barely hit the couch when I went sound asleep and didn’t wake up until I heard Miss Lyttle coming in the door sometime after daylight. She had delivered a set of twins out at Chris Bentinck’s.This story suggests midwifery came to be a regular part of Lyttle’s work in the district, and this narrative reveals a high level of competence if she delivered twins without physician support. While the anecdote is framed to highlight the physician’s chronic fatigue, it also depicts the public health nurse as a clinician competently working (and traveling) on her own in the community as well as the physician trusting her knowledge and ability sufficiently to sleep through a strenuous, but normal, delivery. The doctor tells readers in his manuscript version how Lyttle was often confused for a midwife, and was often offered payment for attending confinement cases, which she, as a civil servant, refused.40 In these stories, Lyttle is cast in a more independent light, as a clinician who eventually seemed to occupy a parallel, complementary, and not necessarily subordinate position to the doctor in the health care hierarchy of the rural region where she was stationed.

28 Rural nurses and public health nurses like Lyttle acting as quasi- or fully independent midwives is not wholly unusual in rural Canadian health care of the interwar period. Wendy Mitchinson has shown how midwifery retained a role in Canadian childbirth through the first half of the 20th century, with a particularly strong presence in poor, isolated, immigrant, and Aboriginal communities.41 Unlike outport nurses in Newfoundland, or Red Cross outpost nurses in remote regions of western Canada, however, Lyttle would have had very little training for midwifery work. It is likely that she would have been exposed to some childbirth on the wards of the Payzant Memorial and in her basic public health nurse training at McGill, which focused on community work; but any competence Lyttle gained in midwifery was largely through association with MacMillan – learned at the bedside on their rounds in the lakes region of Cape Breton. In the transcript of her interview with MacMillan, Lyttle in fact admits that one of the reasons why she was so “anxious to go” on confinements with the doctor was because she had had no experience with home births before arriving in Baddeck and that she desired this competency; they were, as she put it, “quite a novelty” for her early in her career. While she might say that her assistance was rather inconsequential in the early years that she worked with MacMillan,42 by the time she moved on to the Atlantic region in Halifax Lyttle’s role as public health nurse had underwent an evolution toward greater professional independence, a wider scope of practice, and an expanded clinical role. This might account for the extra workload borne by Lyttle, and perhaps explains the increase in hours and miles observed over the last four years of her decade in Baddeck. It seems clear from these community narratives from Cape Breton that Lyttle had accumulated from the community the type of skills and become the resource that local necessity dictated would best serve public health in the rural, far-flung reaches of Victoria County.

Finding the Line between Community and State

29 It is unfortunate that Phyllis Lyttle never penned her own autobiography; one reporter who interviewed her on the cusp of retirement in 1966 confirmed that her stories from Baddeck would, indeed, “fill a book.”43 She did, nonetheless, inspire a work of fiction, published in the Canadian Nurse in 1949, the year she left Baddeck. “Ten Years in a Rural District,” authored by Lilias Toward, a local businesswoman and writer, revolves around a conversation struck up when an early morning fisherman catches the public health nurse on her way home from delivering a baby, something she readily does when “the doctor is called elsewhere.” This fascinating document admits to being based on Phyllis Lyttle’s career in Victoria County, and it uses many details specific to her particular situation to discuss the importance of public health nursing. It reveals that the hard-working nurse, for instance, is about to leave the district for a “suite of offices” in the “fine new provincial building” being erected in the capital. The pair reminisce about the community fundraising that went into setting up and furnishing her office in the local courthouse. She describes her typical school inspection, including a general hygiene check of the children, administering a patch test for tuberculosis, and arranging for immunizations and vaccinations. The nurse’s only regret is that she did not do more for the treatment and follow up of venereal disease in the district, although she notes that “in this rural community they are comparatively rare.”44

30 For the purposes of this article, however, the most interesting passages reflect what this fictional Lyttle considers her “most important work”: maternity care. The account offers a lengthy explanation of why the public health nurse does not organize prenatal clinics for the community as a whole, but prefers to “visit [women] in their homes and find out under just what conditions the baby must be delivered.” She believes it is critical to instruct members of the household on “how to make the bed up, the washing of the bed clothes, how to prepare blocks to raise the bed making it easier for those in attendance.” During the delivery, she will return with the doctor, or come on her own if he is not available. But unlike the physician, she will stay for a day or two after the birth to make sure “all is well” and then return once more in six months, when the time comes for immunizations and vaccinations.45

31 To describe midwifery services in terms that depict them as individualized “prenatal care” stretches the terms of reference for public health in this era. It may be that some details in Toward’s short story are embellished, but the author seems blithely unaware that most authorities would have difficulty justifying the scope of public health nursing practice she is describing. The narrative even closes, for instance, with the nurse performing minor surgery in an emergency situation that presented, predictably, on an occasion when the doctor “was away.” But the editors of Canadian Nurse did not object to the piece, and Phyllis Lyttle’s supervisor, far from censuring the depiction, cited and praised it in her annual report for 1949. While the tone and content of this friendly, early morning conversation between fisher and nurse strikes the reader as highly improbable, the scenario allows the fisherman, as community member, to articulate sentiments held by the author herself. It seems clear that Lilias Toward greatly admired Phyllis Lyttle and, while the dialogue is fabricated, the work details have a clear basis in fact and there is little reason to doubt that the sentiments for the nurse and her work are conveyed with absolute integrity.

32 Although her willingness to learn and accommodate local health needs earned her praise from the people of Baddeck, such activities eventually ran afoul of the expanding and professionalizing public health bureaucracy in Halifax. When the Nova Scotia government published a Survey of Health Facilities and Services in 1950, public health nursing was heralded as a great benefit to Nova Scotians. Public health advocates in the province pointed to “a definite decrease in death rates for infectious diseases, respiratory and digestive diseases, conditions peculiar to the first year of life, and maternal mortality.” These successes have “proven the value of public health work in these fields, and these programs should be continued and expanded where necessary.” Notwithstanding this praise, the section on public health also took considerable pains to clearly demarcate the line between private practice and public health. The authors of this survey reminded the public that health departments are established to “accept responsibility for all health problems which affect the whole community or a group of families.” Physicians, on the other hand, “should accept full responsibility for all services relating to the health of the individual and the members of a family unit.” The authors of this survey also observed that provincial public health employees had set up programs that overlapped into the scope of private practice, especially in areas where local services like “prenatal care and pediatric supervision” were lacking. The department might well have been chastising Phyllis Lyttle and C. Lamont MacMillan directly when they flatly pronounced such practices “wrong in principle” while putting the onus on the community practitioner to correct the situation by “accepting his rightful responsibility.”46 Services rendered to the individual, like performing minor surgery or delivering a baby, were not to be a part of public health programming in the province.

Conclusion

33 The stories and narratives about public health nursing, while they present problems in terms of their perspective and strict factuality, still enrich the historical record by fleshing out the details of public health nursing that are otherwise only available as bare statistics of hours and miles. At the same time, this article underlines how the early generations of public health nurses in Nova Scotia were required to operate on a tenuous boundary between community and state. As employees of the province, they were required to meet certain goals as they set up generalized public health programs throughout the province. The case of Phyllis Lyttle in Baddeck shows how community needs – an overworked physician’s need for assistance and a remote community’s need for an extra pair of trained hands in case of emergency or sudden childbirth – often surpassed the mandate of the state and required the individual nurse to make accommodation to local circumstance. Far from resenting these kinds of accommodation, some nurses like Phyllis Lyttle in Baddeck quickly realized the concomitant opportunities. Though the demands on her time and travel were great, Lyttle used this opportunity to widen her scope of practice, at least for a time, and pursue maternity work with a passion. She made accommodation with local authorities in support of the state investment in public health, but also went against administrative expectations so that she might also evolve as a health care provider. Looking back at the end of her career, with diplomas from McGill and Toronto, Phyllis Lyttle still maintained it was the time she spent in Baddeck that “made a public health nurse out of me.”47

Footnotes