Articles

Bureaucratizing the Atlantic Revolution:

The "Saskatchewan Mafia" in the New Brunswick Civil Service, 1960-1970

Lisa PasolliUniversity of Victoria

Abstract

Louis J. Robichaud recognized at the time of his election as premier in 1960 that bureaucratic modernization was urgently needed to translate the political gains of the "Atlantic Revolution" into workable social and economic programs in New Brunswick. To provide leadership in civil service reform, Robichaud recruited seven ex-Saskatchewan Co-operative Commonwealth Federation bureaucrats who became known as the "Saskatchewan Mafia." This article uses their experiences to explore the bureaucratization of the Atlantic Revolution, and argues that this group played a crucial role in the transformation of New Brunswick’s political bureaucracy and thus in the modernization of the province as a whole.Résumé

Lors de son élection comme premier ministre en 1960, Louis J. Robichaud reconnaissait qu’il était urgent de moderniser l’appareil bureaucratique afin que les gains politiques de la « Révolution atlantique » se traduisent par des programmes sociaux et économiques réalisables au Nouveau-Brunswick. Pour exercer le leadership dans la réforme de la fonction publique, Robichaud recruta sept anciens fonctionnaires sous le gouvernement de la Co-operative Commonwealth Federation de la Saskatchewan, que l’on appela la « Saskatchewan Mafia ». À partir de leurs expériences, cet article explore la bureaucratisation de la Révolution atlantique et fait valoir que ce groupe a joué un rôle crucial dans la transformation de la bureaucratie politique du Nouveau-Brunswick et, par conséquent, dans la modernisation de l’ensemble de la province.1 NEW BRUNSWICK’S FIRST ELECTED ACADIAN PREMIER, Louis J. Robichaud, came to power in 1960 determined to move the province into the 20th century socially and economically. By Robichaud’s own estimation in 1969, the province had, prior to his election, "been dealing with its difficulties on a piecemeal basis, achieving only limited industrialization, its people in many areas underemployed and undereducated, unfairly taxed and over-governed."1 Robichaud’s Liberal administration had ambitious plans for reform, but the bureaucratic capacity to manage and implement those plans was lacking. Above all, New Brunswick needed personnel and leadership to expand, professionalize, and modernize its civil service.2Luckily for Robichaud and his advisors, in 1964 Ross Thatcher’s Liberals defeated Woodrow Lloyd’s Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF – and soon to be the New Democratic Party) in Saskatchewan, and upon Thatcher’s assuming power many CCF officials resigned. Donald Tansley, the chair of the Medical Care Insurance Commission, was one. Recognizing the value of Tansley’s experience, Fred Drummie (Robichaud’s economic advisor) invited him to Fredericton to explore the possibility of taking up a position in Robichaud’s administration. In early 1964 Tansley visited Fredericton to meet Robichaud and other members of the government and civil service. In a discussion with the premier, Tansley outlined his experience with state-managed programs such as medicare and government insurance, prompting Robichaud to declare: "Well, I’m for all those things too, but I’m no bloody socialist!" Undaunted, and armed with the conviction that Robichaud was a socialist "in everything but name," Tansley accepted an offer to become New Brunswick’s new deputy minister of finance and industry.3 He moved to Fredericton in July 1964, and was soon followed by six other ex-Saskatchewan bureaucrats – Robert (Bob) McLarty, Paul Leger, Graham Clarkson, Nancy Bryant, Donald Junk, and Desmond Fogg – creating a contingent of former CCF civil servants in New Brunswick who became known as the "Saskatchewan Mafia."4

2 This article examines the role and activities of this mafia in New Brunswick’s civil service and uses their experiences to shed light on the broader process of bureaucratic modernization necessitated by Robichaud’s programs. In the context of a series of exciting political gains for the Atlantic region known as the "Atlantic Revolution," as well as a nation-wide recognition that a new breed of bureaucrat was needed to manage the developing welfare state and state-run economic programs, Robichaud was eager to recruit talented civil servants who could allow him to capitalize on political excitement to create viable programs.5 This article argues that the Saskatchewan Mafia, and Tansley in particular, drew upon their Saskatchewan experience to provide guidance and direction to the modernizing Robichaud civil service. That is not to say that aspirations of modernization did not exist among the native New Brunswickers in the administration; Robichaud’s small stable of advisors recognized that the transformation of the provincial bureaucracy was a priority. They also realized, however, that the province required additional help in making this happen. Their recruitment of the Saskatchewan Mafia demonstrated their commitment to serious and prompt change. Without the presence of this mafia, the New Brunswick bureaucracy would not have transformed as efficiently and rapidly as it did.

3 Across Canada in the 1960s, the creation and growth of welfare state programs and state economic planning necessitated the expansion and reorganization of civil services at both the federal and provincial levels. In Ottawa, this need was recognized in 1960 when Lester Pearson appointed the Royal Commission on Government Organization (Glassco Commission) to investigate the activities and organization of government departments and agencies.6 Provincial administrations, in particular, experienced rapid growth. The number of provincial public employees increased by 447 per cent from 1946 to 1971 (compared with a still-impressive increase of 80 per cent at the federal level). From 1961 to 1971 alone, provincial government employment in Canada grew by 108 per cent.7 Perhaps more importantly, during these years the role and characteristics of senior civil servants changed. Expected to move beyond purely administrative duties to embrace policy-oriented activities, civil servants entered into a partnership with politicians that Ken Rasmussen describes as "political administration."8 The ideal bureaucrat in a post-Second World War public administration environment, according to Rasmussen, had a background in specialist and technical education, was hired based on his or her merit rather than through a patronage appointment, had a respectful relationship with politicians, and held a commitment to collective bargaining for public employees.9

4 How these transformations in the provincial bureaucracy unfolded in New Brunswick has been largely neglected.10 Under Robichaud’s leadership, from 1960 to 1970, the province’s political, cultural, and social landscape underwent far-reaching changes; but we do not yet know enough about the machinery of government that managed those reforms. Studies of the Robichaud decade, including Della Stanley’s, highlight the role that senior civil servants played in terms of policy roles, but rarely probe deeply into the workings of bureaucratic reform.11 What is missing from our understanding of the Robichaud era is a portrait of the details of bureaucratic change that provided the foundation for all other reform programs. This article begins to fill that gap by focusing on the experiences of the Saskatchewan Mafia – all of whom played roles in the transformation of the day-to-day bureaucratic mechanisms.

5 New Brunswick’s bureaucratic modernization took on new urgency in the 1960s because of the nature of Robichaud’s sweeping slate of political, economic, and social reforms, which have been documented in detail by a number of historians and political scientists. Scholars have focused particularly on Robichaud’s Programme of Equal Opportunity, a reform package based on the Royal Commission on Municipal Finance and Taxation chaired by Bathurst lawyer Edward Byrne. At the heart of Byrne’s recommendations was the centralization of "services to people" at the provincial level, including health care, education, welfare, and the administration of justice.12 Byrne’s report formed the basis of the 1965 White Paper on the Responsibilities of Government, which signified the government’s commitment to dealing with social development in a meaningful way.13 The result was the Programme of Equal Opportunity, a collection of approximately 130 pieces of legislation that transferred a huge amount of administrative responsibility from municipalities to the provincial government, which necessitated not only an expanded civil service but new sources of financing.14

6 Equal Opportunity and the accompanying plans for state-driven economic initiatives were ambitious; but they were thought possible in large part thanks to the gains of what Margaret Conrad calls the "Atlantic Revolution" in the 1950s.15 The Atlantic Revolution was of critical importance to the provinces because, despite legitimate efforts in the post-Second World War era to stimulate the region’s lagging economy, regional interests had consistently been "sidelined" by federal policies.16 In the 1950s, however, political and business leaders in the Atlantic Provinces put aside their partisan differences in the common belief that "state planning was the only alternative to economic inferiority, and that federal aid was the necessary condition for the success of such planning"; they subsequently presented a united front to Ottawa and insisted on the need for more federal funding for the region. This Atlantic Revolution resulted in a number of highly publicized political and financial victories for the region, including the creation of the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council (APEC) in 1954, the inaugural meeting of the Conference of Atlantic Premiers in 1956, the introduction of equalization in the 1956 federal budget, Diefenbaker’s $29.5 million loan to New Brunswick’s Beechwood power project, and the earmarking of $25 million annually for four years for the region in the form of the Atlantic Provinces Adjustment Grants.17 Into the 1960s, these federal commitments to the region took the form of initiatives such as the Agricultural Rehabilitation and Development Act in 1961 (ARDA), the Atlantic Development Board (ADB) in 1962, and the Fund for Rural Economic Development (FRED) in 1966.18 This influx of federal transfers, along with a willingness to run budget deficits,19 meant that Robichaud’s administration could commit itself to action – especially on social initiatives.

7 What is less well understood, and what this paper seeks to address, is the administrative and bureaucratic effort that was required to turn political will into practical programs. Optimism regarding the future of the region was running high when Robichaud was elected in 1960, but the new premier recognized that despite public victories the "Atlantic agenda remained unfinished business."20 The Atlantic Revolution had outlined the necessary scope of economic and social development for New Brunswick, and the political commitment for change (that would eventually be represented by Equal Opportunity) was present, but to translate political victories into workable programs required effort at another level. What was required, in other words, was the bureaucratization of the Atlantic Revolution.

8 The Saskatchewan Mafia in New Brunswick was crucial to ensuring this bureaucratization occurred as smoothly as possible. Tansley and his colleagues had many years experience working with the CCF administrations of Tommy Douglas and Woodrow Lloyd (1941 to 1964), where they had become knowledgeable about state-run social and economic initiatives. Robichaud and his advisors knew in 1960 that the civil service needed to be revamped, but they also knew that the people and resources to make that happen were lacking within the existing bureaucracy.21 The influence of the Saskatchewan Mafia within New Brunswick’s public administration led to changes in financial management, budget preparation, federal-provincial relations, personnel organization, and employer-employee relations in the civil service. Tansley, in particular, had a long-lasting impact on how government administration was undertaken in New Brunswick, and his experiences are the focus of this article. Tansley was recruited to New Brunswick fresh from creating the entire administrative structure of medicare in Saskatchewan, and his expertise and confidence helped ensure that New Brunswick’s administrative overhaul occurred as efficiently as possible. He was the principal architect of the province’s new financial administration structure, but his influence extended to many other areas of administration, including civil service staff relations and even economic policy.22 McLarty and Leger were also principal players in terms of economic planning and relations with Ottawa; Bryant, Clarkson, Junk, and Fogg played lesser roles, but they were still important players in the sense that they applied Saskatchewan lessons to New Brunswick. Viewing this mafia’s experiences as an important part of bureaucratic modernization in New Brunswick allows us to better understand how the success of Robichaud’s reforms depended in large part on the transformation of the provincial bureaucracy.

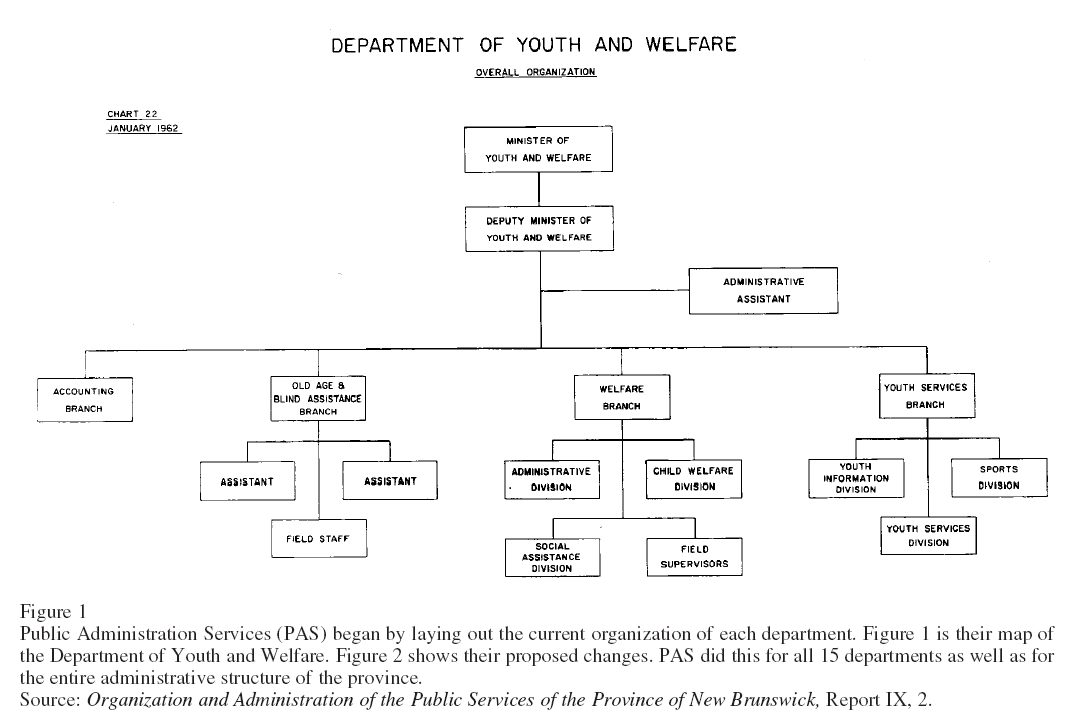

9 The civil service that Robichaud had inherited in 1960 has been described as "inward-looking" and "in general . . . still being run and based upon rules which had been established during the Depression."23 Civil service reform was therefore a priority for Robichaud in his first term, indicated by his almost immediate commissioning of the Chicago consulting firm Public Administration Services (PAS) to provide a portrait of what the scope of reform would entail. PAS undertook studies of position classification, pay scales, and, eventually, an intensive study of the organization of the entire administration. Their report of 1962, the Organization and Administration of the Public Services of the Province of New Brunswick, made it bluntly obvious that the current systems and practices of the civil service were inadequate, and their condemnation of the civil service extended into virtually every department and agency. They suggested that study and planning for policy development, especially in the economic arena, were "lacking in quality and intensity and [were] performed in a less than fully coordinated matter." Budgetary administration, they argued, proceeded in an "informal and less than adequate fashion" and, in terms of personnel administration (which they pointed out "profoundly influences the effectiveness" of the public service), the report suggested that a new plan was needed to ensure that staffing was adequate to meet program requirements. They put much of the onus on the Civil Service Commission in terms of the responsibility for carrying out these recommendations. In addition, they suggested that new systems of training, recruitment, discipline, and supervision were needed at all levels and recommended that more employees of the provincial government (i.e., non-permanent employees) actually be brought under the authority of the Civil Service Act, which would further the goal of reducing patronage and improving training programs.24 Besides these general recommendations that affected the whole of the government organization, the PAS report also included detailed plans for reorganization on a department-by-department basis, which they laid out in organizational charts (see figures 1 and 2).

10 To address PAS’s recommendations, Robichaud began working towards building up a stable of talented bureaucrats to manage the modernization of the province. Hiring young officials such as Economic Advisor Fred Drummie and economist Bill Smith was a first step, but to fill out the roster of senior civil servants, as Stanley argues, "the province had to find them beyond its borders."25 In 1964, personnel issues took on new urgency with the retirement of Provincial Treasurer Thomas O’Brien. This was when Drummie began looking for the "best person in Canada" to fill the position.26 Looking west to the pool of jobless bureaucrats in Saskatchewan (by choice or otherwise), he first offered former deputy minister of finance and industry A.W. Johnson the job.27 Having already accepted a position in Ottawa, however, Johnson recommended Donald Tansley. Drummie readily agreed, noting that Tansley was "known within the community of other provincial governments and in Ottawa, and within the financial community," and this made him an attractive person to have in New Brunswick’s corner as it embarked on reform programs – the success of which rested in large part on productive federal-provincial relations. Furthermore, Tansley’s background in the tradition of CCF social and economic planning was a "bonus" to complement his "good solid understanding of what provincial government is about," his "clear philosophical position of . . . public service," and the "awful lot of detailed know-how" that he possessed.28

Figure 1. Public Administration Services (PAS) began by laying out the current organization of each department. Figure 1 is their map of the Department of Youth and Welfare. Figure 2 shows their proposed changes. PAS did this for all 15 departments as well as for the entire administrative structure of the province.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

11 Robichaud was eager to infuse his administration with the kind of talent and capability Tansley offered, and it was an easy decision to install him as the deputy minister of the Department of Finance and Industry.29 Tansley arrived in Fredericton excited to be part of what he called "perhaps the most fundamental, most dramatic and most rapid reforms to local government and provincial services which have ever been attempted in Canada."30 He was soon followed by, and in fact had a hand in recruiting, six of his former Saskatchewan colleagues. In Saskatchewan, these seven public servants had developed their skills in the "Saskatchewan tradition of public administration" and particularly in the Saskatchewan Budget Bureau, which Allan Blakeney has called the "best college of public administration in Canada at the time."31 An emphasis on long-term and closely integrated planning and budgeting functions was a hallmark of the Saskatchewan tradition,32 along with progressive policies with regards to employer-employee relations.33 As creators and managers of welfare state programs, medicare foremost among them, Saskatchewan civil servants gained administrative experience that civil servants in other jurisdictions were years from acquiring. Graduates of the Saskatchewan tradition left the CCF administration after its defeat with skills that made them attractive to other administrations, and a number of them made a particularly significant impact in Ottawa with the Lester Pearson government.34

12 In New Brunswick, the hiring of "outsiders" was, as Tansley suggested, a big step for the small province.35 This was especially true when it came to Tansley himself, the most influential and publicly recognized of the Saskatchewan Mafia. His role in the administration extended "far beyond his assigned duties" as deputy minister of finance and industry and secretary to the Treasury Board, and the various roles he played in the government often put him at the centre of the political storms created by Equal Opportunity legislation and controversial industrial ventures.36 For many, his status as a newcomer – a person "from away" – only contributed to the displeasure many people had with his hiring. "Tansley – that’s not a New Brunswick name, is it?" was a query he heard more than once upon his arrival to Fredericton. It was not only political opponents who were irritated by his appointment. Tansley recalls at least one "hate note" being sent from an anonymous member of the bureaucracy, and Minister of Public Works André Richard initially opposed his hiring.37

13 One thing that Tansley could not be criticized for was a lack of training and experience in public administration. A Saskatchewan native, he was born in Regina in 1925 and, after serving in the Second World War, returned to attend the University of Saskatchewan where he received Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Commerce degrees in 1950 with specializations in economics and business administration. Immediately upon completion of university, he accepted a job with the Douglas government in the Treasury Department, where he remained until 1960. His reputation as a skilled administrator earned him the role of temporarily replacing Johnson as deputy minister of finance from 1957 to 1960.38 Upon Johnson’s return, Tansley moved on to serve as executive director of the Government Finance Office from 1960 to 1962, an organization that functioned as a holding company for the province’s Crown corporations. By 1962, Premier Woodrow Lloyd was on the lookout for someone to chair the Medical Care Insurance Commission, a position that would require thick skin and superior organizational and management abilities. Beginning with little more than "a table, a telephone and a piece of legislation," Tansley created the structure of the commission and maintained it for two years. Following his four-year tenure in New Brunswick, Tansley, like nearly all other members of the Saskatchewan Mafia, ended up in Ottawa where, among other roles, he served as the administrator under the Anti-Inflation Act, a role which gave him the quasi-judicial functions of adjudicating wage and price cases heard by the Anti-Inflation Board.39

14 Of all of the Saskatchewan Mafia installed in New Brunswick, it is Tansley whose career provides the most insight into Robichaud’s modernizing civil service. As deputy minister of finance and industry from 1964 to 1968, he was involved in financial administration as well as programs for economic and industrial development. Along with his deputy minister portfolio, Tansley also served as secretary of the Treasury Board and secretary of the New Brunswick Development Corporation. His close ties with Drummie, both professionally and personally, meant that he was consulted on all of the most pressing issues facing the government, including the drafting of the White Paper on the Responsibilities of Government in 1965 as well as the details of the Programme of Equal Opportunity. During his years in New Brunswick, Tansley reformed the province’s accounting and budgeting procedures, contributed to better staff relations in the civil service, fostered better federal-provincial relations, and gave new direction to public administration in the province by instituting new standards for consistency, coherence, and accountability.

15 Upon arriving in Fredericton in 1964, Tansley assumed the administrative reins of a finance department that had, in his words, "everything but the quill pen."40 The department relied on a hand-written account ledger book to oversee the financial management of the province, a system obviously inadequate for the new responsibilities that came along with Equal Opportunity. One of Tansley’s first undertakings, then, was to transform the Department of Finance into a "professionally staffed, modern, computerized" department.41 He personally recruited and hired a number of financial specialists and accountants to work in the department, and remained concerned throughout his stay in New Brunswick that the government make a concerted effort to recruit professional and technical staff.42 Tansley made no secret of the fact that he was interested in "stealing" key Saskatchewan talents, since his experience in the Saskatchewan Budget Bureau had familiarized him with the importance of sound financial management and he was confident in the abilities of his former colleagues.43 Credit for the creation of a modern finance department in New Brunswick belongs almost entirely to Tansley.

16 A key component of the transformation of the overall financial administration of the province was the introduction of a new computer system. New Brunswick had first started using a centralized computer system for accounting functions early in 1963, but by late 1964 it was found that some "features have proven to be unsatisfactory both to operating departments and to the Department of Finance."44 Tansley struck an Accounting Review Committee, which included himself, Drummie, and four others, to undertake a detailed study of the accounting system and the entire computer operation. This study covered questions such as whether the present computer applications were appropriate and economical as well as whether the equipment being used was the best available (especially with regards to accounting systems). The committee submitted a report to Treasury Board in August 1965 recommending the acquisition of a new computer and, most importantly, a "greatly expanded staff of professional people" to operate and maintain the system.

17 Treasury Board agreed with the recommendations and empowered Tansley to purchase a new computer as well as approving new positions (a director of Computer Services and systems analysts).45 Recruitment of trained technical personnel proved a problem, so Tansley enlisted the help of the Toronto consulting firm KCS, which he was familiar with from his medicare days.46 KCS used one of their own people as acting director of Computer Services for the government until a permanent director was found, and in the interim managed the operations of the province’s new G.E. 415 computer and trained staff to operate the system.47 The introduction of a computer system was an invaluable asset not only to the financial management of the province, but also to the management of provincial responsibilities such as property assessments and tax collection. It allowed the government to increase consistency and efficiency in its business, and was also symbolic of the centralization of administration that was taking place in the province.

18 Another problem area was the province’s financial legislation. Realizing that the finance department had neither the time nor the resources to undertake a thorough review and rewriting of the existing legislation, Tansley looked to Ottawa for assistance. A federal consultant was seconded to Fredericton and within six months he had drafted the new Financial Administration Act, which rationalized the basic foundation and organization of the province’s financial management. Under the new legislation the Treasury Board was given broader authority, especially with regards to budgetary procedures and rates and conditions of employment in the civil service. The draft also called for the creation of a Consolidated Revenue Fund that would eliminate the need for separate bank accounts for "special purpose monies" and that would greatly benefit the management of government accounts by simplifying "accounting and cheque issues procedures" and allowing for more careful supervision of funds.48

19 To complement the new Financial Administration Act and the modernized Department of Finance, Tansley also worked to introduce new procedures for budget preparation and review. These changes were first felt as departments started to prepare their estimates for the 1965-66 budget. According to Tansley, the new budget review system was a "straight copycat" of what he used in Regina, and it required detailed information regarding revenues and expenditures from each department.49 As both the deputy minister of finance and secretary of the Treasury Board, Tansley had perhaps the most authority of anyone to influence the direction of the budget and he used his influence to collaborate closely with all deputies.50 Individual meetings with these deputies were arranged in which Tansley and the respective deputy went over, line by line, the department’s estimates. This was often a shock to deputies, who had never before had anyone say to them "No, you can’t have 30 new employees – try and justify 10 for me" (as Tansley often had to say). With this new emphasis on bureaucratic accountability, it was no wonder that a common refrain heard around budget time was "Tansley can’t add, but he sure as hell can subtract."51

20 This new emphasis on closely supervised budgeting procedures was meant not only to "promote more accurate budgeting" but also to encourage greater emphasis on departmental planning, improve the timing of estimates submissions (which had in previous years been rushed and, therefore, carelessly done),52 and, most importantly, "provide Cabinet with a greater opportunity to participate in the formation of the budget and . . . provide for a more thorough consideration of policy and the financial implications of all budgetary requests."53 Ministers and their deputies were expected to stick to a timeline that included strict deadlines for the submission of estimates and departmental "Budget Plans." A cabinet budget conference was held for the first time in December 1964 to plan for the 1965-66 budget and, following the conference, departments were again expected to review their budget plans and further justify any new programs or increases in expenditures to Tansley and Drummie. In other words, by the time the budget was introduced in early 1965 it had been rigorously reviewed and re-reviewed by departmental staff, senior civil servants, and ministers – a process that up until then had not been the usual practice.54

21 Coming from a province considered the national leader in granting rights for public employees, it is no surprise that Tansley also made it a priority to reform civil service staff relations. Pension reform figured largely into his plans, but that was far overshadowed by the negotiations around collective bargaining – the achievement of which marked an important milestone in the modernization of the civil service and brought New Brunswick’s personnel relations up to the standards of other provinces.55 Tansley characterized New Brunswick’s Civil Service Association (CSA), probably somewhat harshly, as the "poorest excuse for employee representation I’ve ever seen."56 Due in large part to Tansley’s insistence, as well as lobbying by the New Brunswick leadership of the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) and the CSA itself (along with action at the federal level that culminated in the Public Service Employment Act of 1967), Robichaud appointed McGill University professor Saul Frankel to head the Royal Commission on Employer-Employee Relations in the Public Services of New Brunswick.57 After extensive hearings, the Frankel Commission reported in July 1967 and called for a new act regarding public servants in the province that would "provide for a system of collective bargaining for many categories of employees that are . . . excluded from the existing New Brunswick Labour Relations Act." Frankel also suggested that Treasury Board be the representative of the government in negotiations with employees, which would leave the Civil Service Commission "with the important responsibility of maintaining the merit system in recruitment and promotion."58 In addition, Frankel recommended that employees have the right to belong to a representative organization of their own choosing. Frankel’s recommendations were heeded closely by the Robichaud government, and in the fall of 1968 the Public Service Labour Relations Act was passed, which gave full collective bargaining rights to all public employees (including the right to strike). In December 1969 a new Civil Service Act was passed as a companion to the Public Service Labour Relations Act, within which responsibility for the negotiation of pay and employment conditions, organizational planning, position and wage classification, and overall budgetary control of personnel services was transferred to the Treasury Board, leaving the Civil Service Commission little to deal with but the staffing of departments. Although its responsibilities were severely curtailed, the commission praised the new Civil Service Act and the right to strike as a positive step for the civil service.59

22 Tansley’s experience in Saskatchewan’s Government Finance Office served him well in the other component of his portfolio – that of industry. Robichaud has been criticized for failing to develop a comprehensive economic strategy during his administration, but the social content of Equal Opportunity along with the social policy orientation of federal shared-cost programs meant that, in relative terms, economic policy had had to take a back seat.60 Lack of an overarching plan, however, did not mean that Robichaud was not committed to action on economic initiatives.61 Tansley was heavily involved in procedures "to protect the government . . . from itself in involvement with industry."62 Surprised at the lack of protection the government had given itself on projects such as Brunswick Mining and Smelting, and especially in terms of their dealings with K.C. Irving, Tansley set to work creating rigid conditions for government loans and guarantees.63 And the New Brunswick Development Board benefited from having Tansley as its secretary as he introduced new financial procedures in much the same vein as he had for the entire government administration.64 He was also involved in such development projects as the Grand Falls Industrial Complex, the Westmorland Chemical Park, and especially the Noranda takeover of Brunswick Mining and Smelting.65

23 A close colleague of Tansley’s when it came to the economic side of government planning, Bob McLarty arrived in the fall of 1964 to take up a position as an economist. Originally from Ottawa, McLarty had taken up a position with the Saskatchewan government at the urging of Johnson, who offered him a job working in federal-provincial relations. After becoming familiar with the New Brunswick administration, Tansley saw a need for someone with experience in the kind of intergovernmental work that McLarty had done in Saskatchewan, and invited him to consider a position in Fredericton. McLarty joined Drummie in the Office of the Economic Advisor (OEA) as the director of economic research in the summer of 1965. Specializing in federal-provincial relations, he held positions in New Brunswick and Ottawa simultaneously, continuing to work part-time for Johnson in the federal finance department.

24 Aside from Tansley, McLarty was the Saskatchewan Mafia member who was most closely involved with the government’s day-to-day operations. Respected for being a first-class economist with a good feel for government, McLarty was chosen to replace Fred Drummie as provincial economic advisor when Drummie assumed the directorship of the Office on Government Organization (OGO) in 1965.66 In 1966 McLarty was already thinking about an overall development strategy for the province and drafted a memo to Drummie proposing a research strategy that could "facilitate the organization and carrying out of an integrated economic development policy by the Government of New Brunswick." Excerpts from this memo figured largely in the anonymous major report entitled "Development Policy Formulation and Administration," which was presented at the 1967-68 cabinet budget conference. In both McLarty’s memorandum and the report, it was recommended that the government undertake a detailed review of the province’s economic policy – one that would assess future development potential, determine priorities, and recommend actions. McLarty suggested that these actions would "clear away a lot of the underbrush" and enable economic choices to be made by a fully informed government.67

25 McLarty’s experience in federal-provincial fiscal relations was called upon frequently. Having Johnson in Ottawa as the deputy minister of finance was a definite benefit to New Brunswick’s intergovernmental relations, and McLarty was able to use this connection to foster a productive relationship between Fredericton and Ottawa, especially in his attendance (along with Drummie and Tansley) at meetings such as the 1965 federal-provincial conference.68 McLarty’s expertise was also called upon in the recruitment of specialists, particularly statisticians and economists, who would provide a solid personnel foundation for the OEA as the province embarked on more ambitious economic development initiatives.69

26 Leaving the OEA in McLarty’s hands allowed Drummie to focus his attention on Equal Opportunity, in which capacity he began to work closely with Paul Leger. Leger arrived in New Brunswick armed with a graduate degree in public administration and an arrangement with Bill Smith whereby he would work part-time with the university and part-time with the government.70 When he moved into full-time government work in 1966, he became director of OGO, taking over from Drummie. OGO’s critical role in the development of Equal Opportunity legislation made it the site of some of the most exciting developments in public administration during the middle part of the decade.

27 Created in early summer of 1965 as the secretariat to the also newly formed Cabinet Committee on Government Organization, OGO housed many of the most senior civil servants in the province and was the driving force behind Equal Opportunity.71 The series of events that occurred during the summer of 1965 highlighted the importance of OGO’s role. It was during these few short months that the politicians and civil servants most directly involved with Equal Opportunity had given themselves several key tasks regarding this program: to clarify "broad policy objectives"; to "review and agree on the basic goals of government in education, welfare, health, justice, and municipal affairs"; to define "program implications of policy decisions"; to explore the "implications of program decisions for provincial-municipal finance"; to "review the basis or organization for the provincial administration of new program responsibilities"; to review and write new legislation; and to undertake a program of public information "to ensure the widest public understanding of the legislation and implementation program."72 The staff of OGO was behind the scenes of all this activity, preparing research reports and "homogenizing" the legislation into a broad policy framework. It is a testament to the ability, efficiency, and devotion of OGO employees that it had ready by the end of October 1965 a full set of preliminary Equal Opportunity legislation – almost 130 pieces of it – to introduce in November. Even more than the ministers themselves, it was the members of OGO and the deputy ministers who were considered to be the real experts on the legislation that was the substance of Equal Opportunity.73

28 When Leger replaced Drummie as director in 1966, OGO staff had moved beyond the "conceptual period" of policy development and legislation drafting and shifted their focus to "coordinating the development of the administrative structures and systems necessary in the provincial government to give effect to the legislation associated with the ‘Program of Equal Opportunity’."74 In other words, it was up to Leger to provide the government with the nuts and bolts of the administrative machinery that would allow Equal Opportunity to become a reality. OGO was home to 11 employees under Leger’s directorship, all of whom were involved in a great number and variety of projects from writing endless research papers to public relations to establishing new financial procedures for the transfer of municipal services.75 As director of OGO, Leger was responsible for managing and overseeing the establishment of a new system for property assessment notices and tax collection, the creation of a new procedure for calculating municipal tax rates, the establishment of regional offices, and wrapping up the loose ends of such legislation as the Schools Act and the Assessment Act.76 When OGO was disbanded in late 1967, Leger moved into the Department of Youth and Welfare, a position that he retained even when Richard Hatfield took office in 1970.77

29 One of Leger’s most senior employees in OGO was fellow Saskatchewanite Nancy Bryant, who was unique among the Saskatchewan Mafia in New Brunswick as the only female. Bryant, along with Graham Clarkson, Donald Junk, and Desmond Fogg, assumed a less prominent role in the administration than Tansley, McLarty, and Leger. Their activities are less evident in the archived memos and reports that circulated within the government, but what we do know reveals that their Saskatchewan experience and networks shaped their role in New Brunswick. The lack of a paper trail around Bryant, Clarkson, Junk, and Fogg is also a commentary on the nature of the civil service in the 1960s. The administration was so small, and officials were so well known to one another, that decisions were often made by visiting the office down the hall rather than crafting correspondence.78 Less involved in the "big picture" policy-making, Bryant, Clarkson, Junk, and Fogg remain relatively invisible in their day-to-day administrative duties.

30 Nevertheless, we do know that Bryant worked under Tansley in the Saskatchewan Budget Bureau as well as in the office of the deputy minister of finance with Johnson. Described as "an absolutely brilliant researcher" who worked "well below her capacity," Tansley and Drummie nonetheless assert that Bryant’s gender had nothing to do with her being underemployed.79 As a single mother, Bryant may also have had difficulty working the long hours required of senior civil servants. Like most of the other members of the Saskatchewan Mafia, Bryant eventually ended up in Ottawa, where she spent a number of years working for the federal Department of Finance. While in New Brunswick, she took a variety of roles in the Robichaud administration: it was recognized among senior bureaucrats that Bryant could "be used effectively at a senior level with either OEA or Finance," the areas of administration in which she had gained much experience in the Saskatchewan Budget Bureau.80 It was generally thought, however, that her experience in financial administration and research would be extremely valuable to OGO. In addition to assisting Leger in his duties as secretary to the Cabinet Committee on Government Organization, she was also involved in a number of "special projects" for OGO, including a study of records management, a study of the responsiveness of regional centres across the province, and, as the province began to think about medicare, a review of the departments of health and youth and welfare. Bryant was also actively involved in a "detailed examination" of the province’s policy with respect to military bases in Oromocto and Chatham and, more broadly, in federal ex-gratia grants. OGO had been serving as the liaison between the provincial and federal governments on the subject of ex-gratia grants, but until Bryant’s appointment there had not had anyone devoting substantial attention to the issue.81

31 Graham Clarkson was a relatively late arrival to Fredericton, taking up the role as deputy minister of health and welfare in 1967.82 A native of Scotland, Clarkson had moved to Saskatchewan to take special training in hospital administration at the University of Saskatchewan and had remained in the province to work in the Douglas administration. Clarkson was a key player in the doctor’s strike of 1962 and, after the strike was resolved, he was offered a position in Tansley’s Medical Care Insurance Commission. He survived Thatcher’s purge of CCF civil servants to serve as the executive director of the commission and later as deputy minister of health, a position he held until his move to New Brunswick in 1967. It was during that year that Robichaud was becoming very interested in medicare, and he and his advisors recognized that a qualified, experienced person was needed to oversee the province’s transition to publicly funded health care services. On the advice of Tansley, Clarkson, a medical doctor as well as a skilled administrator, became their top choice. He was known not only to Tansley but also to people like Drummie and cabinet minister Norbert Thériault, who had crossed paths with Clarkson during intergovernmental meetings on the medicare issue during the 1960s.83 Clarkson was a forceful personality whose capabilities allowed him, recalled Tansley, to radically redesign and restructure the health care system in New Brunswick with "very little fuss."84

32 During Clarkson’s time as deputy minister, the Department of Health and Welfare was in the midst of reforms to a number of its programs, including changes to the mental health program and welfare services. These reforms required aggressive administrative skills, something that Clarkson certainly possessed. Upon his arrival in Fredericton, one of his very first official duties was attendance at the annual general meeting of the New Brunswick Medical Association. Surprising everyone, Clarkson requested permission to speak. After introducing himself, Clarkson got right to the point and declared that the doctors’ fee schedules were too high and needed immediate reform. While some may have been shocked by his boldness on the first day on the job, Clarkson’s take-charge personality would prove invaluable to the reform of health care administration in the province.85

33 One of Clarkson’s colleagues in the Saskatchewan Department of Health had been Donald Junk, and when Clarkson identified the need for an assistant, he suggested Junk for the job. Junk arrived in New Brunswick in 1968 to take up the job as director of research and planning as well as administration within the Department of Health and Welfare.86 Junk, along with Desmond Fogg, played important administrative supporting roles: Junk in personnel functions and Fogg as assistant to Minister of Labour Bud Williamson. Junk remained in Fredericton into Hatfield’s administration, and in November 1973 replaced J.C. O’Connor as assistant treasurer of Treasury Board.87 Fogg left Fredericton for Yellowknife, where he drew upon his journalism and communications background to establish a newspaper.88

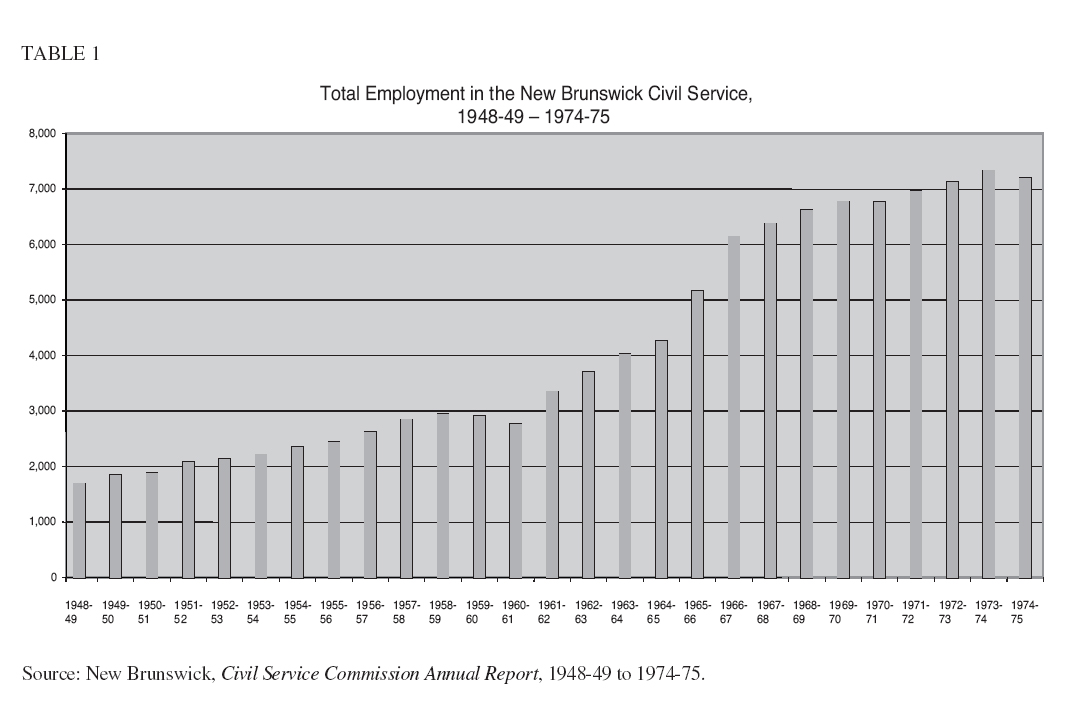

34 By the end of the 1960s, the New Brunswick civil service had changed in both quality and quantity. Not only did the administration undergo remarkable change in a short amount of time, it had to accommodate dramatically more people in doing so, growing by 133 percent (see Table 1).89 At the level of new structures and processes, the civil service was transformed into a modern and professional institution: departmental reorganization, new accounting and budgeting procedures, enforcement of the merit principle, the introduction of collective bargaining, a renewed focus on research and planning, and a new approach to economic development were the characteristics that defined this transformation. Over the course of the decade, Robichaud’s administration became one that was capable of managing the new responsibilities required of it as the province adapted to Equal Opportunity and the gains of the Atlantic Revolution.90

TABLE 1. Total Employment in the New Brunswick Civil Service, 1948-49 – 1974-75

Display large image of Figure 3

35 Provincial administrations in the other Atlantic provinces paid close attention to what was happening – and who was making it happen – in New Brunswick. Recognizing that Robichaud and his team were undertaking a remarkable program of modernization, the other Atlantic premiers were eager to learn from the process and, in many cases, to borrow the expertise nurtured in New Brunswick. Prince Edward Island in particular was attempting to address the same types of economic and social problems that New Brunswick faced as well as the reforms to the civil service that were required as a prerequisite.91 In 1967 Del Gallagher, a Robichaud advisor, made the move from New Brunswick to Prince Edward Island to head up the newly formed Economic Improvement Corporation (EIC), which had a mandate to plan and manage development programs under the premiership of Alexander Campbell.92 The Civil Service Commission of New Brunswick reported in 1969 that "we . . . were able to advise Civil Service representatives of . . . Prince Edward Island who asked for help in setting up Civil Service Commissions." This was also true in Newfoundland, where bureaucrats also requested help from Robichaud’s officials.93 Nova Scotia benefited from the expertise of Fred Drummie, who was recruited to the Gerald Regan administration in the early 1970s to work in economic development. New Brunswick was not unique in its progress in civil service reform, but it was certainly a leader in terms of how quickly and ambitiously reform was embraced, and it did not take the other Atlantic provinces long to mine the Robichaud administration for policy and people.

36 The modernization of New Brunswick’s bureaucracy would not have happened as efficiently or rapidly if not for the leadership of the Saskatchewan Mafia, and in particular Tansley, Leger, and McLarty. Della Stanley has suggested that during the 1960s bureaucrats such as these three acquired such responsibility that they virtually took over from politicians and became a "legislating body" as well as a management one.94 In interviews Tansley disputed this, but this denial may have been the result of modesty or stemmed from the fact that he had wielded more power than he himself recognized.95 While Tansley may not have "taken over" – and both he and Drummie insisted in interviews that the final word rested with politicians – it is difficult to deny the strength of Tansley’s influence. Besides creating an entirely new financial structure for the province, in his capacity of secretary of Treasury Board and director of the NBDC Tansley held sway over economic policy in the province – a role he stepped into naturally given his responsibilities in Saskatchewan’s Government Finance Office. Furthermore, in a civil service as small as New Brunswick’s it is pertinent to note that Tansley was well-liked personally as well as professionally. The high regard in which he was held meant that Tansley’s opinion carried a lot of weight, no matter what the issue.96 Without him, and without McLarty and Leger and the remaining members of the "Saskatchewan Mafia" to supplement New Brunswick’s growing and modernizing civil service, New Brunswick’s development after the Second World War may well have looked quite different.

37 The 1960s was an exciting time to be a civil servant in New Brunswick: government programs facilitated by federal money necessitated an ambitious and energetic administration while bureaucrats were afforded more influence in the policy process than ever before. Benefitting from the changes that established the structures and processes of a modern bureaucracy, the civil service played a key role in planning, implementing, and managing the reforms of a rapidly changing province. By 1969 Robichaud had the chance to reflect on the changes in his administration:We have been most fortunate in the past nine years in recruiting highly competent, professional teams of specialists to staff our government departments. The new recruitment, and the use of dedicated staff already employed in the public service when we came to office, made it possible to create the administrative framework without which it would have been impossible to implement the massive legislative program which Equal Opportunity involved. It was indicative of the new administration’s attitude toward government that the political background of the teams of specialists was of no concern. The only prerequisites for employment were the ability to get things done and the acceptance of new challenges and new ideas and new solutions to both old and new problems.97

38 Robichaud’s bureaucratic modernization facilitated the sweeping social and economic reforms that characterized New Brunswick in the 1960s. Understanding the roles played by members of the Saskatchewan Mafia allows us to appreciate the nature of the changes required to make the political victories of the Atlantic Revolution a reality and to modernize New Brunswick as a whole.

Footnotes