Merchants, the State and the Household:

Continuity and Change in a 20th-Century Acadian Fishing Village

Derek JohnsonUniversity of Guelph

1 A WIDE RANGE OF SUBSISTENCE activities, supplemented by work for cash or credit, sustained the households of Val Comeau, in New Brunswick’s Acadian Peninsula, in the first half of the 20th century. Local merchant companies played a central role in domestic economic strategies, providing access to money and credit. This changed in the 1950s as these companies withdrew from Val Comeau, and the Canadian state increasingly assumed the role they had once played as a source of cash and security. Subsistence activities declined as federal transfer payments grew. Fishing increasingly became the most important economic activity in the community, in part because work in the fishery provided reasonably secure access to income from unemployment insurance. As a consequence of these changes, the economic base supporting the residents of Val Comeau became narrower and more vulnerable. Yet another shift appears to be underway in recent years as the state withdraws from the role it had assumed in the local economy. Throughout a century of changes, however, there has been an important continuity: the centrality of the household to production and social organization.

2 The persistence of a household-based adaptation that permitted residents of Val Comeau to survive the challenges of the 20th century deserves exploration, for it reveals much about the texture of economic change and social life in the community. Household-based economic strategies, coupled with community co-operation, allowed residents to secure a living in difficult times and in a context where steady employment was scarce. The pooling of household-produced resources has been essential for effectively responding to economic uncertainty. It remains to be seen, however, whether these strategies will be sufficient to overcome the challenges posed by environmental degradation, reduced access to resources and the withdrawal of state support for the community’s residents.

3 The data for this study come primarily from interviews conducted with 59 residents of Val Comeau and neighbouring settlements in the summer of 1993, and on shorter visits between 1991 and 1997. The interviews were open-ended and guided by the methodology of ethnography. Sixteen of the informants lived in Val Comeau, but others provided useful information as well about the village, the neighbouring town of Tracadie, and the Acadian Peninsula in general.1 Their recollections provide valuable insight into the lives of ordinary people. Both memory, upon which anthropologists rely, and archival materials, which are dear to historians, are selective in what they reveal. Although there is a loss of precision in constructing history from oral testimony — much of which was, in this case, collected well after the events discussed — the limitations of the approach are offset, to some extent, by the advantages to be gained by directly probing zones where written records are sparse or silent. The recollections of the men and women of the Acadian Peninsula allow us to see the details of the complex patterns of life that have enabled the residents of Val Comeau to make that stretch of coast their home.

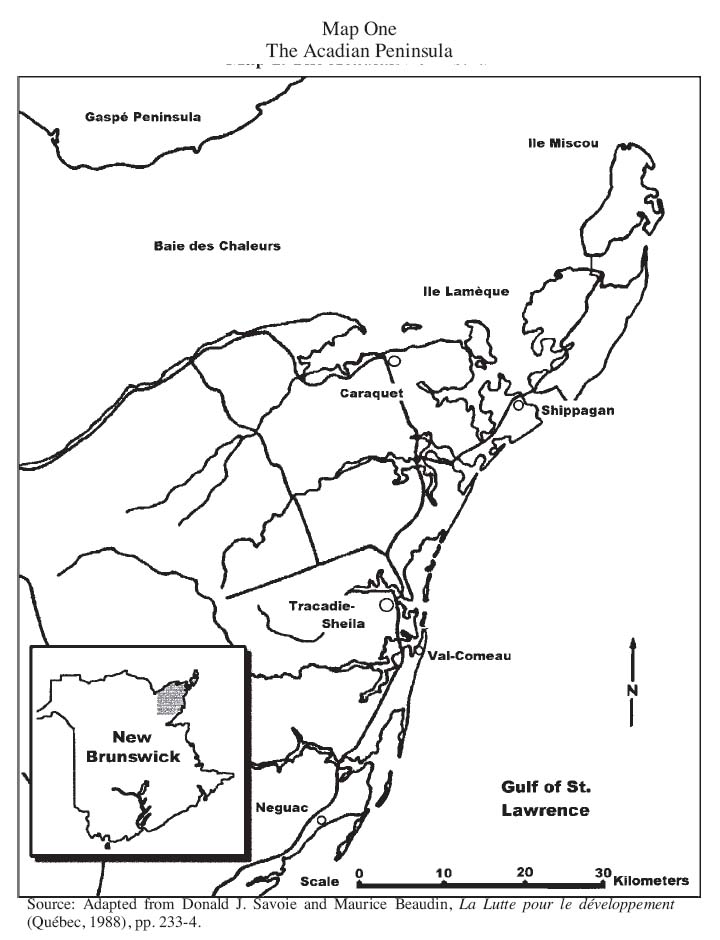

4 Val Comeau is known today as a fishing village. It is situated on the east coast of New Brunswick’s Acadian Peninsula, about five kilometres to the southeast of Tracadie-Sheila, the principal commercial centre for the Peninsula (see Map 1). The 1991 census lists 547 inhabitants who, like most residents of the Peninsula, speak French.2 Val Comeau used to be known as La Dune, reflecting its location on a triangle of land three kilometres in length which provides a break between the Atlantic to the east and the bay of the Tracadie River to the west. The village has a wharf on the calm bay side and 33 fishing boats used it in 1993; 25 of these boats were owned by villagers.3

5 The Acadian Peninsula was one of the principal sites of Acadian resettlement after the Deportation, and the first Europeans probably settled in what was to become Val Comeau in the late 18th or early 19th century.4 By the 1920s, it was a small but thriving community, well situated to take advantage of a diversity of marine and land-based resources.5 Fishing, agriculture and forestry were the three principal economic activities at this time. During the spring and summer, the village bustled with fishing and agricultural activities. After the harvest in the fall, it became calmer as most of the men in the community left for work in the woods and their families settled in for the harsh winter.

6 Despite access to many natural resources, Val Comeau’s residents needed to spend long days at physical labour throughout the year in order to meet household needs. Families were large, often with more than ten children, which made for crowded conditions in the small houses of the village.6 The healthy adults worked hard to feed and clothe young and old, and dependents contributed as they could.7 The elderly knew no age of retirement, and children assumed household tasks early in life, expanding their roles after they left school, generally at an early age.8 Much of that work was for subsistence and was shaped by the seasonal rhythms associated with different primary resources. Residents also incorporated into their schedules available opportunites for wage labour — principally with fish companies and lumber companies.

Map One: The Acadian Peninsula

Display large image of Figure 1

7 In the early 20th century, household members worked from late spring through the early fall, stocking up on the bulk of their provisions for the winter. All but the poorest households had gardens sufficient in size for their winter needs.9 Potatoes, beans, turnips, onions and carrots were the most important vegetables, grown in plots behind each house. Beans were dried, carrots canned and the other vegetables were stored in the cellar or in a deep pit in the yard. There they remained cool but did not freeze. Buckwheat and oats were also grown for household consumption and as fodder for domestic animals. Horses were kept as draft animals, sheep for their wool, cows for milk and butter, and chickens for their eggs.10 Residents hunted moose, deer, geese, ducks and rabbits at different times of the year to supplement meat from chickens, cows and pigs.11 They preserved some meat by salting, to use when fresh meat and fish were not available. Most of the meat eaten during the winter had been salted, pickled or dried, but on some occasions households slaughtered a pig and shared the fresh meat among neighbours.12 Families gathered blueberries, raspberries, cranberries and strawberries, and made them into preserves. They also collected wild plants, primarily for medicinal purposes, though they ate dandelion leaves and used wild anise as a spice for cookies.13

8 Fishing was central to stocking up for the winter. In the late 1920s, at least five households owned rowboats that permitted them to catch a variety of fish.14 Lobster, salmon, herring and cod were the most important of these. The merchants of the area bought salmon and lobster that they tinned and exported. During the lobster season lobster heads were free for the taking at W.S. Loggie Company’s canning plant in Val Comeau.15 Residents ate some of these, but used most of them to supplement the manure and river sediment with which they fertilized their fields.16 They preserved herring at home for the winter by salting them in barrels of 200 pounds, know as "un quart".17 They salted and dried cod as well, and during the summer months harvested clams.18 They also caught gaspereau, eels and trout in the river and bay to the north and west of the community, and they scooped capelin up by the bucketful to use as an intensely odiferous compost.19

9 October’s harvest activities were the last big rush of subsistence work before the winter set in. The men of Val Comeau went to settlements further inland at this time as well, where they paid landowners for the right to cut firewood for the winter. Five dollars or a "quart" of herring was sufficient payment for as much as a horse could pull out 20 times.20 Soon after the harvest, men from households with little land left Val Comeau to work for logging companies.21 Larger landowners in the village might forgo the wages such work offered as returns from their properties gave them the freedom to remain in the village for the winter. Men working in the woods tended to be absent for between three and six months and usually did not visit their families during this time. Those who returned after three months came for the smelt fishery, which they conducted from shanties they built over holes in the ice on the bays along the coast. In the late winter, some residents of Val Comeau fished for herring as well, through the ice of the open ocean.

10 Given the large families in Val Comeau in the early 20th century, the partial absence of men during the fishing season and their longer absence during the winter, women played an important role in sustaining the household. They assumed primary responsibility for feeding and watering livestock, which included the heavy work of drawing well water. In some seasons, men and women shared farming tasks, but even in the summer men were only available in the afternoons after returning from the morning’s fishing.22 As a consequence, women had to be able to do everything that the farm required, from turning the soil in the spring to cutting the hay in the fall.23 Women were also responsible for household maintenance, often while pregnant and almost always with children to mind. Simply keeping the household fed required constant daily effort. Women had to organize winter provisions, which meant packing supplies into the outdoor root cellar and basement, if the house had one. They had to ensure that sufficient high quality seeds were preserved for the following year’s growing season. In addition to canning fish and game, they canned clams and berries, which they gathered at the end of the summer and in early fall. They had to milk the cows twice daily and churn the butter before putting it into brine to preserve it for the calving season when milk would not be available. Throughout the year, women prepared the day’s meals and snacks. This included the time-consuming tasks of rehydrating dried beans and salted fish, and kneading and baking bread. Raising the latter was an overnight process as the leavening agents were potatoes fermented for a week with sugar, ginger, a bit of old yeast and locally-gathered hops.24

11 Keeping the family in clothes in the early 20th century was no easy task either. Cotton cloth was available from merchants, but warm clothes were made from wool carded and spun in the household itself.25 Groups of women gathered together to do the work in what was known as "un job", and the woman whose wool was being carded or spun would supply cake and cookies and make the sharing of the work a festive occasion. Women moved from house to house over the course of the year until everyone’s wool was ready for knitting. Older men often had responsibility for making moccasins for the family.26 As footwear was in scarce supply, children went barefoot as soon as the snow melted.27 Washing was an especially arduous task involving much scrubbing and rinsing in tubs of hot and cold water.

12 Household livelihoods were buttressed by support from the larger community of Val Comeau and from neighbouring communities including Sheila, Tracadie, Benoit, Rivière du Portage, Brantville and Pont LaFrance, where the residents of Val Comeau had links through marriage. They maintained kinship ties, and broadened them, by meetings at mass and in the stores of Tracadie, the service centre of the area since at least the 1920s.28 One of the favourite pastimes of the Acadians of the area was to walk the roads between communities, stopping to visit friends and family here and there.

13 The deep connection of the people to the land, ocean and forest of the region strengthened community bonds in Val Comeau. One resident of Tracadie claimed that the people of Val Comeau spoke with a distinct accent, which, if true, suggests the depth of interconnection among the people of the place.29 They celebrated their solidarity in popular entertainment, which included music, story-telling and pantomime. The most exciting event of the season was the mi-câreme, held over three days at mid-winter, when a disguised band of villagers moved from house to house making enormous amounts of noise, scaring all they visited, playing music, telling tales and caricaturing different people in the village.30

14 Community bonds helped to sustain households in the early 20th century. The rotation of pig slaughtering, for instance, increased the days when fresh meat was available. Families adopted a similar strategy by sharing milk when their cows were dry.31 When a household was unable to complete its preparations for winter due to illness or other circumstances, neighbours organized "frolics" and villagers turned out to help with tasks such as cutting hay or splitting wood for the winter. The beneficiaries of frolics would reciprocate by offering a party afterwards with food and drink.32 The community cared for the aged, the poor and the mentally disabled, even in situations where they had no close kin, taking food to their houses and providing shelter on occasion. The very poor of Val Comeau had access to government assistance as well, known as "la relief", but people were hesitant to take it because of the stigma involved.33 Relief was administered from Tracadie and consisted of a bag of flour and a pound of tea per month. One informant claimed that those who took government assistance in the early years of the century lost the right to vote.34

15 Although there were few social distinctions between households in Val Comeau, there certainly were economic differences. Some households experienced economic difficulties that were eased only by the help of their fellow villagers and the assistance of the state. There were longer-standing economic differences between villagers with substantial amounts of land and those with less. Those with ample land tended to be decendants of the original settlers of Val Comeau who had retained generous land grants from the 19th century.35 In the 1920s and 1930s, four or five households had roughly 60 acres each. The remaining 30 or so households owned only an acre or less.36

16 Differences in land ownership in Val Comeau led to differences in the patterns of work of households. Those with substantial land holdings had a greater degree of independence. Their farms and large numbers of animals provided them with more than sufficient subsistence for the year. They were the only households in Val Comeau that grew wheat, which they had milled at Pont Landry, near Tracadie. Production of their own wheat eliminated dependence on merchants for that most critical staple. Presumably, households in this group sold or traded farm surpluses with merchants for their commodity requirements, relieving them of the need to engage in wage labour and undertake the winter migration to find work with logging companies.37 In the winter the men of these households concentrated on smelt fishing, and in the summer they worked on their farms and fished from their own small boats. Those households with the largest land holdings in the village hired labour to help harvest their potatoes at the end of the season.38

17 Although subsistence production was central to Val Comeau’s economy in the 1920s and 1930s, all households, with the exception of the few with abundant land, relied on work for wages or credit to ensure their survival and to allow for the minimal luxuries that money permitted. Most families went to Tracadie once a week to shop or simply to look at what was available. Basic household commodities were also available at the few small stores in Val Comeau. Once a year, in the late summer, families made a bulk shopping trip to Tracadie to obtain necessities for winter, including flour, tea, molasses, cotton thread, paraffin, lamp wicks, lard, salt and sugar.

18 The type of work available to generate the savings, or credit, needed to make these purchases varied, depending on gender, age and season. In the 1920s, the major employers for the residents of Val Comeau were two merchant fish trading companies — A. & R. Loggie and W.S. Loggie — and various logging concerns around New Brunswick. A. & R. Loggie bought the Val Comeau fishing sheds and factory of the older William Ferguson Company in the 1910s, canning lobster there until the early 1930s, when it switched all of its fish processing to its Tracadie factory, the centre its operations for the area.39 After that, A. & R. Loggie used the buildings in Val Comeau for storage but little else as the dories it depended on for its most important activity, salmon fishing, could not get through the gully of Val Comeau to safe anchorage on the bay side.40 Anything that the dory crews needed to load or unload at Val Comeau had to be rowed out to them from the beach. The W.S. Loggie company fished lobster and bought clams and lobsters. It also canned both throughout the 1920s and 1930s. It was the more important of the two companies in Val Comeau, having extensive factory facilities there.41 The logging companies that hired men from Val Comeau were all based further afield in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Maine.

19 The largest group of women who were in a position to work for wages during extended periods were those who were not married. Women in their mid to late teens and early twenties commonly sought wage work which would allow them to save for their weddings.42 Some girls went to do live-in domestic work for families in neighbouring communities. Wages were minimal, but sending children to work away reduced the burden of upkeep among the larger families of Val Comeau.43 Women of all ages might obtain canning work with W.S. Loggie during the lobster season.44 Cooking was also a common occupation, either at W.S. Loggie’s boarding house, which housed workers from outside the village, or at lumber camps during the winter. It was common for women to leave the village for work. Some went to lobster factories at Wishart Point, Neguac or as far away as Richibuctou, and others worked as nurses in the area’s hospitals.45

20 Most of Val Comeau’s men fished for W.S. Loggie or A. & R. Loggie, in the spring and summer. Those few men with their own boats used them to fish for salmon, lobster, cod, mackerel and herring, most of which they sold to the commercial companies and some of which they kept for their own household consumption.46 Most men fished in boats owned by the companies and had their monthly wages put against their outstanding accounts in the company stores. The greater number of men worked in the companies’ smaller boats for the May to June lobster season. Part of their work was to set nets for herring for bait, some of which was salted for use the following year.47 A few men worked on larger sailing dories called "goëllettes"; these fished cod from the middle of May to the middle of June, switched to salmon through June and July, and then reverted to cod for the rest of the summer.48

21 At different times during the year, women and men had other ways to earn cash or augment their credit. At the end of the summer entire families picked blueberries for a penny and a half to three cents a pound.49 There were a number of different buyers, including, in the 1920s, one man who also had a boat building business.50 Money from blueberries was particularly important as it came just before people needed to purchase winter provisions and children’s school supplies.51 Following the blueberry harvest, some work was available digging potatoes for the larger landholders of the region, including the church.52 In the winter, men fished smelts and sold them for a penny a pound to W.S. Loggie. One man sold salt cod to a dealer in Shippegan53 and others sold clams to W.S. Loggie and to a local man, Maxime Breau, for canning. Breau also purchased lobster and mackerel for canning, although on a much smaller scale than W.S. Loggie, from fishers who had their own boats. Other men, such as Ephrem Godin, acted as intermediaries, or "jobbers", for the Loggies, buying and canning lobster for them.54 Adults and the elderly also made fishing nets at the end of the winter and sold them to W.S. Loggie for three dollars per hundred or a penny a pound for all types.55

22 By working for W.S. Loggie and A. & R. Loggie and selling local produce to them, the residents of Val Comeau gained essential but constrained access to needed commodities. The relationship between the residents of Val Comeau and the merchant companies was based on a system of credit that ensured the latter a steady supply of cheap labour. At two points in the year, the households of Val Comeau required access to supplies from the larger market. In the fall they needed to purchase supplies for the winter.56 In the spring they needed to purchase seed for the summer crops and perhaps food to top up their diminished larders.57 As the Loggie companies were the dominant link to the market, they provided the required goods. Having little or any cash, villagers had to take their goods on credit with the promise to pay the balance through their summer wages or through payment in kind. Rarely did their work result in cash in their favour.58

23 As W.S. Loggie and A. & R. Loggie had credit relationships with the men in Val Comeau for household and fishing supplies, the latter had little choice but to work for companies and sell them their catches in order to pay off their debts. Along with the credit came the stipulations that all fish caught while the fisher still owed money be sold at company rates and that all purchases for the household be made in company stores in Val Comeau or Tracadie.59 Even after a season fishing with A. & R. Loggie or W.S. Loggie, men often ended up in a situation of "square John": not owing the company money, but also not getting any pay from them.60 Women who worked for W.S. Loggie in Val Comeau were restricted in where they could make purchases, as they were given a credit note for their wages that they could use only at the company store in Val Comeau.61 Men and women who worked for W.S. Loggie found it doubly difficult to pay off their loans because they ate three meals a day on company credit. The meals were hearty, but costly.62

24 The merchant-dominated system offered important benefits to fisher households. Merchant credit acted as a form of insurance against poor seasons. During hard times, households were still able to obtain credit to buy basic supplies, such as flour, and they might get through the winter without starving.63 At the same time, with subsistence production as the base that assured household survival, the merchants did not have to provide a living wage to their workers, because much of what their labourers needed they produced themselves.64 The merchants did not, however, have absolute control over the local economy.65 One striking indication of this is that some residents of Val Comeau had sufficient cash to purchase cars as early as the mid-1920s.66 Clearly, some of Val Comeau’s surplus was being retained by the villagers themselves. This surplus supported at least two small locally-owned stores in Val Comeau, offering alternative outlets for the purchase of household goods.67

25 Some of the explanation for the limitations of merchant power in Val Comeau may lie in the specifics of the community’s history. A. & R. Loggie was a newcomer to Val Comeau. The company first gained a foothold in the community in the 1910s, although it may have hired local sailors well before that. W.S. Loggie’s roots were likely deeper, but it still never had a monopoly position in the village. Prior to the arrival of A. & R. Loggie, it faced competition from the long-established William Ferguson Company. As well, the companies had to contend with landholders in Val Comeau who had the means to be independent of merchant control, and who may have provided other residents with alternative sources of credit. This may have been true as well with Maxime Breau, the "jobbers" of the village and the managers of the local stores. Alternative sources of income for residents limited the commercial power of the two Loggie companies as well. Logging work outside the community, which was the main form of wage labour, allowed men to earn from 50 cents to $1.00 a day in the 1930s. From such wages, they might send home $10.00 a month and return at the end of the season with $25.00 in savings.68 Some years, though, they earned almost nothing and would have required greater support from the merchants.69

26 Through the 1930s there were indications that Val Comeau’s economy was diversifying away from the control of the merchants, and more residents of Val Comeau began to compete with W.S. Loggie for a greater share of the returns from fishing. In the mid-1930s one young man bought old factory buildings from A. & R. Loggie and attempted to rejuvenate the canning business that the company had wound up a couple of years earlier.70 He did not have much success, perhaps due to the difficult economic times.71 During the 1930s, several men in Val Comeau introduced longer fishing boats of 25 feet, which gave them greater independence from the merchant companies. In the late 1930s, they began to install small one horsepower "whippet" engines on the boats.72

27 At the beginning of the 1930s, competition in fish purchasing increased when a new lobster buyer came to Val Comeau. He offered 12 to 25 cents a pound for lobster, depending on size, while W.S. Loggie offered only eight cents.73 The established merchants came under pressure from another quarter as well at this time. The Catholic church began to promote credit unions, co-operatively managed stores and fisher cooperatives in order to challenge merchant dominance in the Acadian economy.74 Though none of these organizations were present in Val Comeau, they challenged A. & R. Loggie and W.S. Loggie in nearby towns including Tracadie, Neguac and Inkerman.75

28 Although Val Comeau’s economy continued to centre on fishing, forestry and farming during the 1940s and 1950s, the village’s economy was transformed in these decades. The role of merchant capital declined sharply while at the same time the Canadian state increasingly made its presence felt in the affairs of the village. The experience of the Second World War broadened the horizons of Val Comeau’s residents, opening the community to larger economic and social forces. During the war many of the young men of the village served in the armed forces, and some went overseas.76 Military service introduced them to the benefits of earning a regular salary and exposed them to new ideas. Other residents migrated to work in the war industries of Saint John, Montreal and Ontario.77 As with the soldiers, those people too gained an appreciation of a regular wage. Remittances from wage earners and government payments to compensate for the temporary loss of their sons allowed those who remained in Val Comeau to share in the monetary rewards available in the wider world.78

29 The new employment opportunities and increased cash flow of the war years stimulated a boom in the Acadian economy, and a consequent rise in the standard of living.79 In Val Comeau the boom continued into the early 1950s and had several important effects. There was an acceleration in the shift from barter relations to cash-mediated relationships, as the amount of currency in circulation increased.80 The demand for horses rose to the point where, as one informant put it, "Les gens commencaient à changer les chevaux comme maintenant le monde change les chars".81 Growing numbers of horses, and cars, made it easier for people to go to Tracadie to obtain goods, and it became an increasingly important meeting place for the people of the region. Some of the new income from the war years was invested in businesses and equipment for work, including, by the late 1940s, new and bigger fishing boats.82

30 As fishers acquired more of the means of production and their wealth increased, pressure on W.S. Loggie grew. The company had never had a monopoly position in the community, but in the 1930s it faced growing competition that further constrained its ability to retain cheap labour. Throughout the 1940s, it remained the largest business and employer in Val Comeau, but its position was increasingly threatened. W.S. Loggie was no longer the only source of summer employment for the residents of Val Comeau, nor was it the major source of money for the purchase of household and fishing supplies. An indication of the company’s vulnerability came as early as 1943, when it stopped providing a monthly salary to the fishers who worked on its boats. From that date, W.S. Loggie switched to paying for all fish by the pound.83

31 The growing number of private boats in the late 1940s allowed fishers to further escape the control of W.S. Loggie. Fishers had noticed by this time that Shippegan fishers who owned their boats were getting significantly higher prices per pound than men in Val Comeau who still worked on company boats. This inequality tempted fishers who still worked for W.S. Loggie to defraud the company by selling, before they returned to port, part of their catch to other buyers who offered higher prices.84 Beyond reliance on an outdated set of relations with the fishers, W.S. Loggie was also hurt by its obsolete technology, including its many small, inefficient factories.85 This all proved too much for W.S. Loggie, which closed its Val Comeau factory in the late 1950s; closure of the Tracadie store soon followed.86

32 The end of W.S. Loggie’s operations was not a catastrophic blow for the fishers of Val Comeau and their families as, by this time, many had acquired their own boats and gear. As well, they were receiving government unemployment insurance payments that tided them through the off-season. Unemployment insurance came to play much the same role in fishing communities as merchants once had, providing the capital to see fishers through the lean season.87 It has had, however, a different effect on the local economy, for while the merchant system depended on and stimulated occupational pluralism and household production, unemployment insurance has muted it. State expenditures in infrastructure became increasingly evident in Val Comeau in the early 1950s. Roads were paved, electricity was brought to the community, and a wharf for fishing boats was built on the sheltered bay shore to the west of the village. In the late 1950s, the state assumed an even greater role as a development agent and supplier of transfer payments.

33 In the post-war period the federal government set out to modernize the economy and society of peripheral regions in order to raise standards of living and better integrate them into Canada.88 Realizing these goals with its fisheries policy was problematic, given that it was informed by a capital-intensive, Fordist model of production.89 The large, vertically integrated firm was to be the wave of the future for fisheries development, and this meant favouring a limited number of centres of economic growth as a means to achieve economies of scale and more efficient methods of production. It followed that the residents of small, isolated villages should be encouraged to move to growth poles, and that new, sophisticated technology should replace labour-intensive production.90

34 The full and rapid implementation of a Fordist strategy of development on the East Coast would have meant enormous social dislocation, uprooting communities and concentrating the fishery in the hands of a few large firms. To cushion coastal residents during the transition and reduce political fallout, the federal government broadened its unemployment insurance programmes in 1957 to include seasonal workers.91 This action directly countered the logic of the Fordist development strategy and went against the government’s original rationale for unemployment insurance. By instituting a more liberal unemployment policy, the state provided the resources for people to stay in their isolated communities and continue to practice an "inefficient" small-boat fishery. Unemployment benefits shifted from providing a temporary support during times of job loss, to serving as a routine income supplement for the off-season.92

35 The changes in unemployment policy at the end of the 1950s, which were strengthened through the 1960s and solidified in 1971, revealed a fundamental contradiction in the direction of development in Atlantic Canada. Unemployment benefits raised incomes and reduced regional disparity in Canada, but they did so through regional income transfers, not through productivity gains. At the same time, they enhanced a dualism in the regional economy by buttressing the small-scale fishing sector of coastal communities that persisted alongside the growing industrial sector of vertically integrated fishing companies. This strategy of development floundered in the late 1980s as overfishing threatened to sink both sectors of the East Coast’s fishing industry.

36 Changes in provincial policy enhanced the role of the state in the Acadian Peninsula during this period as well. When Louis Robichaud became premier in the 1960s, he developed policies to reduce disparities between different regions of the province and to improve the standard of living in Acadian areas.93 His reforms in school financing and in the health sector created much greater equality of services across the province. Acadians increasingly had the same chances as English-speaking residents of New Brunswick to finish their secondary studies and gain access to advanced education.94

37 The state interventions that began in the 1950s had an enormous impact on Val Comeau. One of the most obvious indications of their effect was the decline of agriculture.95 Unemployment insurance payments played a central role in this, as they provided the cash that made it possible for households to purchase their food needs in Tracadie. Stocking meat and vegetables for the winter ceased to be a survival imperative, and animal husbandry was all but abandoned.96 The only large cultivated areas remaining in the village today are scrubby blueberry fields. The merchant-credit system had depended on subsistence production in agriculture — as well as in other areas — to subsidize an extractive capitalist economy and ensure profitability. The logic of transfer payments was different as the state’s concern was to relieve poverty by adding resources. This transfer of resources reduced the need for subsistence production while also providing a surplus income to more of the community than ever before. One resident noted that in the mid-1960s he was finally able to buy household appliances and take full advantage of the electricity that had come to the village in the 1950s. Cars became common in the same period. Motorized transport allowed men and women to commute farther afield for daily work. With modern appliances and purchased food products and clothing, women could maintain the household with less labour, allowing them to take advantage of new job opportunities, particularly in fish processing and the service sector.97 Their efforts brought additional income to the household, further raising its material standard of living.

38 Unemployment insurance policies also reinforced the increasing professional separation of fishing and logging. That process began in the late 1940s, as technological innovations changed logging from a winter occupation to one where much of the work occurred in the summer.98 Increasingly the men of Val Comeau found they could no longer fish and log in the same year. With the opportunities provided by unemployment benefits, as one informant noted, residents could now work in either occupation for 26 weeks a year and obtain 26 weeks of benefits. There no longer was any need to work in both. The separation became more entrenched in the 1960s and early 1970s as unemployment benefits became more generous. Men and women who worked in the fishing and forestry industries for ten weeks in a year could rely on state support during the remainder.

39 Occupational specialization contributed to the increasingly professional and industrial character of fishing in the 1960s and 1970s. So also did growing entry costs, licensing restrictions on participation and increasing educational requirements. From the 1950s, equipment costs became more and more onerous for fishers. When W.S. Loggie left Val Comeau, fishers had to find ways to finance their own boats and equipment. With mechanization, these costs became more significant. Government loans to inshore fishers for the purchase of boats and equipment first became available in Val Comeau in 1961.99 The introduction of fibreglass boats and increasingly sophisticated mechanical and electronic equipment in the 1970s raised costs yet further. Licensing requirements for lobster were introduced in 1967, and by 1976 all commercially fished species were regulated this way.100 Restrictions on who can fish were enforced by fisheries officers as well as by the fishermen of Val Comeau themselves who kept an eye out for poachers. Under these circumstances, those without licences could not easily supplement the household food supply through fishing. Licensing requirements, electronic equipment and federal regulations have made fishing more and more akin to running a business, requiring a higher level of education than was the norm in Val Comeau in the early 20th century. The expansion of education in the Acadian Peninsula has helped to meet this need, and since 1964 the Fisheries College in Caraquet has provided formal training in skills specific to fishing.101

40 The 1950s, then, were a key moment in the transition from a merchant-supported subsistence economy to one dominated by the state. This shift distanced the residents of Val Comeau from access to the goods they required for everyday life. Villagers grew less of their own food and fished less for themselves. As well, they no longer directly produced the bulk of their household goods, nor did they obtain the remainder from merchant stores where they had long-standing relationships. The security of a subsistence-based economy was traded for an increase in the material standard of living. As a result, Val Comeau’s households became increasingly dependent on outside forces.

41 During the 1970s and 1980s, state transfer payments reached their maximum levels and became integral to the way people made a living in Val Comeau. This enabled the village to better withstand two dramatic changes: the end of work in the forest industry and the disappearance of the cod. In these decades employment opportunities in the logging industry declined sharply. The logging companies of northern New Brunswick faced growing economic difficulties beginning in 1960s, and they responded by replacing many of their workers with machinery and reserving their remaining woods workers for rocky and boggy areas where machines could not operate effectively. In the 1990s, logging virtually ceased to be an alternative occupation to fishing for the men of Val Comeau; in 1997 there were only two men still working in forestry.102

42 The decline of logging left fishing as the major economic activity in Val Comeau, with lobster as the most important species. Cod had been an important secondary species. In the late 1970s, however, cod stocks began to decline, and by the 1980s fishers were increasingly catching herring, dog fish, scallops and other species as replacements that would provide the months of employment required for the maximum duration of unemployment benefits. The middle to late 1980s were boom years for some of those in the fishery — especially mid-shore fishers based in other communities of the Acadian Peninsula — who profited from the burgeoning demand for crab.103 Many men and women from Val Comeau took advantage of job openings in the factories of Lameque and Shippegan that processed the catch, including the wives and sisters of the fishers of Val Comeau.

43 In the mid-1990s Val Comeau retained an air of stability and modest prosperity. A number of events, though, have raised questions about the viability of Val Comeau’s economy as the limits of the resources upon which it depends are more and more evident and state support is increasingly in doubt. At the end of the 1980s, the fishing boom fell off sharply as the cod disappeared and crab catches declined. The fishing industry was saved to some extent by the strength of the lobster sector, which afforded reliable catches and good prices. Today Val Comeau is primarily a lobster fishing community; 24 of the 25 fishers from the village have lobster licences, and it is by far the most lucrative species they catch. The women of Val Comeau, however, lost their jobs in the cod and crab processing industries, and there has been a troubling decline in other species, including clams, gaspereau, salmon, capelin and smelts.104

44 Some of the loss of jobs in resource industries has been mitigated by an increase in service sector alternatives, principally in Tracadie. One informant stated that Val Comeau is now divided roughly in half between those who work in fishing and fish processing and those who work in other occupations.105 Judging from the occupational data for Saumarez Parish, the lowest level of census data available for the area in which Val Comeau is situated, men in non-fishing-related work are primarily in construction and women are in service industries.106

45 Unemployment insurance is under threat as well. When I spoke with them in 1993, a number of villagers expressed worry about the future of the existing system. Their fears were heightened by changes that have been made since that time, as access to unemployment benefits was restricted in 1995 and payment periods reduced from 50 weeks to 45.107 Some residents of Val Comeau foresee a continued gradual reduction of the system with people having to find more work or make do on much less. The Maritime Fishermen’s Union has articulated residents’ concerns about the new policies and is pressing the government for greater flexibility in the demarcation between inshore and mid-shore fishing. This would permit inshore fishers to catch a wider variety of species and thereby work during a greater part of the year. A first step in that direction has been the allocation of a small part of the mid-shore crab quota to inshore fishers. Expansion of inshore fishers into mid-shore areas will require greater outlays of money for boats and equipment and this may heighten inequalities among the inshore fishers of Val Comeau. At present, only a few fishers in Val Comeau have the capacity to catch crab and they have done all the fishing for the recipients of the crab licences in return for a share of the catch.108

46 Although the importance of household-based production has declined in the 20th century, the household retains a central place in the organization of production in the community. This is seen most strikingly in the way that household members engage in a diverse range of activities in order to make ends meet. These include activities in the formal economy, such as assembling Christmas wreaths or gathering blueberries, and those in the parallel economy, such as work for unreported payment and exchange. Activities in the parallel economy may slip outside the legal framework of employment, but they are an integral part of the economy of Val Comeau, direct descendants of the frolics and other types of mutual help so prevalent in an earlier period. Subsistence activities also continue to be important to household economies. Gardening and canning persist, as do hunting, clam-digging, firewood-cutting and fishing for trout, smelt and eels. The ubiquity of the household freezer, or freezers, reflects the use of a new technology to preserve traditional subsistence foodstuffs. Although subsistence production supplies a smaller percentage of household needs now than it once did, it nonetheless provides a way of acquiring products other than by the commodity economy.

47 Although transfer payments from the state have become a way of life for most villagers, they have been adopted according to the logic of a household-based strategy for coping with uncertainty.109 Acquiring unemployment insurance benefits is another element in the range of activities that keep households together and increase options.110 A major priority for the residents of Val Comeau is to string together enough weeks of labour force activity to qualify for unemployment insurance. When household members cannot obtain sufficient employment to do so, and income is limited to provincial social assistance, household incomes suffer. For that reason, fishing boat captains are increasingly hiring female family members for their crews, thus ensuring that unemployment benefits are kept within the household.111

48 Fishing, now the most highly desirable occupation in Val Comeau because of its relatively high returns and opportunities to qualify for unemployment insurance payments, remains a household-organized activity. The eldest male of the household usually owns the boat and licence, and labour is generally provided by his sons, other close male relatives, or his wife and daughters. Capital investment decisions are made in the household, and it is here that accounts are kept. Household members on shore increasingly keep in touch with their boats via cellular telephones. Households help as well with the educational requirements of the fishery. One of the most successful fishers of Val Comeau is illiterate, but he is one of the top fishers of the village because he combines his work experience with the abilities of his wife and son to handle the paperwork.

49 The flexibility and adaptability of these household-based economic strategies have helped the residents of Val Comeau to overcome the many challenges they have faced in the 20th century. By pooling resources at a household level, and at a community level, they have enhanced their ability to cope with economic uncertainty. In the second half of the 20th century, the residents of Val Comeau creatively adapted their strategies to include the opportunities afforded by the rise of the welfare state. No doubt household-based economic adaptation will remain central to the community as it responds to the new and difficult challenges posed by the reduction of the state’s role in helping to provide income and security, as well as by the loss of access to resources and by the effects of environmental degradation. These may prove the greatest challenges the community has ever faced.

Notes