Trouble in the North End:

The Geography of Social Violence in Saint John 1840-1860

Gordon M. WinderUniversity of Auckland

1 SECTARIAN VIOLENCE BETWEEN the Orange Order and Irish-Catholics tore apart Saint John in the 1840s. While the conflict emerged from transplanted antipathies and traditions of violence, it resulted in specific local clashes in Saint John. To a large extent, this violence centred on the Irish Catholic ghetto at York Point. Orange Order parades through York Point met with violence, and groups on both sides resorted to vandalism, arson, assaults and riots. These sectarian clashes, which also included resistance to measures imposed by authorities, carried the hallmarks of pre-industrial social violence. At the same time, these were public and political acts imbued with ritual, drama and publicity, and they involved struggles to define the community identity within a changing urban terrain. By analyzing the geographical relationships between these aspects of the social violence and the city’s physical, social and symbolic terrain, this paper revises interpretations of the role of the Irish Catholic ghetto in the troubles.

2 The dramatic urban riots of 1847 and 1849 in Saint John have been interpreted in the contexts of an ethno-religious conflict transplanted across the Atlantic, local undercurrents of socio-economic disparity and massive in-migration during the Irish famine migration. Building on the traditional view of the big riots as sectarian clashes, Scott See identifies both an urban geography and an annual timetable of marches and disturbances.1 The troubles are shown as a particular case of social violence in which Irish-Catholic immigrants, encountering a hostile reception, defended their turf in bounded, local clashes. Representatives of all classes defended their positions in society, and since a "socio-economic chasm separated Irish-catholics from the host society", "a class conflict lay embedded in the more explicit ethno-religious struggle".2 According to See, there were "skirmishes on several fronts, including cultural and religious institutions, the workplace and market place, and ultimately local and provincial politics",3 but the Orange Order had defined the scenario for the major riots, nativist Protestant ideology had triumphed in the York Point battle and the Orange Order had secured hegemony in the city’s political patronage system.4After the 1849 riot, civic authorities banned Orange parades from the streets, and urban violence diminished in intensity. An economic revival, the end of the Irish famine migrations and an official local accommodation of the Irish-Catholics all assured peace in the 1850s. Tensions continued but the protagonists fought in no more large-scale clashes. In general, then, See interprets Saint John’s social violence as pre-industrial crowd behaviour associated with ethnic group antipathies and conflict between immigrants and native-born, much of it focused on an urban ghetto — problems similar to those facing residents in many North American cities.

3 Central to See’s interpretation, but underdeveloped in his analysis, is the idea that York Point was an Irish-Catholic ghetto surrounded by Protestant neighbourhoods. Although never stated in this fashion, See’s interpretation seems to rely on the view that the city’s charter group attempted to segregate Irish-Catholics into low-class accommodation and work. To do so they used Orange Order vigilantes, discrimination in housing and job markets and their control of the administrative apparatus. Sectarian violence stemmed from these practices and from resistance to them, especially when residents tried to expand the ghetto and thus gain control over additional resources. There is considerable evidence to support such an interpretation of the city’s social violence, but one important fact raises doubt. While a sizeable group of poor, Irish-speaking, Irish-Catholics from Cork did cluster in Saint John’s York Point tenements,5poor Irish-Catholics also settled in numbers in every ward and parish. As a result it is difficult to believe that the Orange Order’s parades enforced and produced residential segregation. Characterizations of York Point as an ethnic ghetto need to be reviewed, as do assessments of social violence in terms of vigilantism and resistance. What forces shaped Saint John’s "ghetto", and what role did the "ghetto" play in the social violence that troubled Saint John at the middle of the 19th century?

4 That an immigrant ghetto should be at the centre of social violence is a recurring theme in the way urban theorists relate ghetto formation and social violence to residential segregation.6 However, urban theorists identify many geographic patterns of ethnic segregation and clustering, only one of which is a ghetto. This diversity of experiences arises locally, Paul Knox has observed, as "the rate and degree of assimilation of a minority group will depend on two sets of factors: (1) external factors, including charter group attitudes, institutional discrimination, and structural effects, and (2) internal group cohesiveness".7 The exclusionary practices of residents, property owners and real estate agents play crucial roles in segregation and mean that much of a city’s housing stock may be unavailable to minority groups. The structure of the housing market may force minorities to cluster in the available cheaper accommodation, and groups may resort to social violence when settling issues relating to access to housing. Segregation may be driven by local practices of segregation, bolstered and legitimized through representations of citizenship and of outcast ethnic groups. Alternatively, minorities may construct ethnic neighbourhoods for their own purposes. Some minority groups cluster for defence during times of social violence, others gather for mutual support or cultural preservation and some concentrate to facilitate attacks upon the charter group.8 Through various combinations of these forces, a wide variety of local patterns of residential segregation and ethnic experience emerge. F.W. Boal identifies several distinct spatial patterns on a continuum from enclave (where internal cohesion is strongest) to ghetto (where external factors are dominant).9 Boal’s continuum helps make sense of the claim that in England, "If they were segregated in some towns, the Irish were never pressed back into ghettoes".10

5 Local circumstances shaped North America’s social violence. While family, clan and religious affiliations structured riots among the Irish, the battle lines among groups varied enormously from city to city and from region to region. In Philadelphia, Irish migration translated into violence on the docks as migrants battled African Americans for work, but in Upper Canada, Irish-Catholics fought each other for canal work.11 In the Ottawa Valley and in the New Brunswick woods, rival patronage networks in the timber trade divided along ethno-religious lines, and groups of male workers clashed over elections.12 In Lowell, Massachusetts, Irish-Catholics gathered together in relatively peaceful neighbourhoods, and eventually won a place in Lowell’s civic politics and society.13 The politics and outcomes of ethnic segregation were different again for the Irish in Montreal and Toronto.14 New immigrants acted to gain control over resources by building ethnic institutions, developing patronage networks, controlling niches in the labour market, winning elections and parading the streets to demonstrate civic legitimacy.15 While migrants were versed in crowd tactics associated with the society they had left, they developed new practices in their destination environments as they adapted to local circumstances.16

6 Perhaps the closest parallels to Saint John’s pattern of social violence are to be found in Toronto, where G.S. Kealey outlines a repertoire of practices, centred on the use of crowds and violence in the streets, used in conflicts over plebeian Orange-Tory domination of the city corporation.17 The Orange-Tory faction controlled civic offices and exercised municipal powers, including tax assessment and collection, engineering, labour for corporation work, relief, police and the licensing of taverns, carters and cabmen. In the streets, Orangemen burned effigies and staged demonstrations, burned buildings in political protest and used mobs to control election polling, and marched, sometimes armed, to demonstrate their power. Orangemen used taverns as meeting places for their activities and defended them against rivals. Until the professionalization of the force in the 1850s, the Orange-dominated city corporation could count on a monopoly of violence through their control of the police and magistracy, as well as the city’s fire companies. Reformers strove to curb the powers of the Orange-Tory coalition through acts to ban secret societies, control party processions, restrict tavern licences, spread elections among multiple booths and outlaw the carrying of firearms, party flags and colours in parades. According to Kealey, Reform politicians eventually secured both a professionalization of the police force in the name of order, respectability and efficiency, and a new bourgeois consensus with Orange-Tory leaders over public order. Residential segregation played little part in Toronto’s social violence.

7 Urban growth disrupted the "cohesive communities" of early North American society,18 but local geography continued to matter in these urban transformations. Citizens used places to establish order in the city. Densely packed, highly differentiated over short distances and with streets as public places, cities increasingly subdivided into exclusive locales and complex localities, all linked by the street. Developers created suburban houses, supervised parks and halls and elite neighbourhoods to offer privacy, safety and order. Model behaviour was represented, situated and constituted in appropriate locales, so that deviant behaviour could be identified and policed with physical force. Elaborate categorizations (the un/deserving poor, drunk, ill, insane, criminal, class, race) lent moral authority to the use of force. Right conduct was to some extent prescribed by the new built structures of each locale, as with the asylum or school, and the construction of new buildings proved an important tactic shaping society.19 Residential segregation in the property market helped to generate group identities and to tie them to neighbourhoods. Parades, monuments, crowds and new public and commercial buildings celebrated this emerging symbolic and built geography of the city. Canadian urban communities of mid-century adjudicated social conflict and built consensus in the city’s central streets.20 Moreover, citizens built social order through parades. In parades, the town functioned as a "theatre of the crowd", with its streets and squares as stages, its balconies as audience platforms.21 Each parade, display, and celebration modelled civic order in elections, civic events, royal and military occasions, political meetings and demonstrations. Citizens constructed a new urban order by remaking the fabric of the city and by remaking the identities of residents.

8 In the face of all this, some groups resisted attempts to define a new urban order. "Trapped in space" by attempts to create civic order, the disadvantaged banded together in small scale communities marked by mutual aid and mutual predation, in order to appropriate space and resources they could not own. As David Harvey has noted, "The result is an often intense attachment to place and ‘turf’ and an exact sense of boundaries because it is only through active appropriation that control over space is assured. Successful control presumes a power to exclude unwanted elements. Fine-tuned ethnic, religious, racial and status discriminations are frequently called into play within such a process of community construction".22 Thus, towns subdivided territorially, as crowds and gangs established battle lines and conducted subcultures of misrule.23 In this context, the charter group might use social violence to define and enforce the idea of a ghetto. Alternatively, when a group clusters to form a base for attacks on the charter group, the territorial borders of their ghetto may have little to do with the geography of social violence. Attacks will target important resources outside the ghetto. Moreover, given the many lines of tension within urban societies, disorder may be unrelated to neighbourhood territories. Instead, groups may riot to disrupt unwanted representations of civic order, or to contest political and economic resource allocations. Thus it is important to establish which places constituted the sites for conflict and how they relate to social tensions and urban development.

9 The peculiar circumstances of Saint John’s urban growth, economy and society shaped patterns of accommodation, segregation and social violence differently than in other North American cities. If we are to understand Saint John’s big riots, then we must study the relationships between urbanization, segregation and social violence and try to understand the role of built form in the generation of group identities. In our analysis of Saint John’s social violence, we need to go beyond the model of a ghetto as a compact ethnic territory to be attacked and defended. Poor Irish-Catholics found homes in every ward and parish and not solely in the tenements of York Point and the Portland wharf district. So why did riots concentrate in the north end tenement districts? Did the Orange Order’s parades enforce and produce residential segregation? How were Irish-Catholics "trapped in space"?

10 Much recent geographical inquiry contends that, as locales, places are historical forces too. Social rules constitute locales, but locales also shape behaviour. Social conflict often develops over the ways in which locales constitute social behaviours.24 We need to consider the ways in which sites within Saint John were contested, and themselves were constructed and destroyed as part of the struggles, and also influenced the struggles. Riots outside the Mechanics’ Institute, a prominent Orangeman’s home or inside a theatre have rather different connotations than riots in the York Point "ghetto". Beyond the crowd events are the arson cases. The first "incident" in the troubles saw Irish-Catholics firing merchants’ stores on 12 July 1837. "Traditional rioting" may have "quickly eclipsed incendiarism"25 but arson and fires of unknown cause troubled Saint John throughout the 1850s, with fires laying waste to large sections of the city. Parades, riots, assaults and arson concentrated in King’s ward and Portland parish, a larger territory than the ghetto. By examining arson, assaults and the construction of symbolic and built environments we may discern a different geography of conflict. To date, research has focused on sectarian clashes. Researchers must now pay attention to the social violence associated with other conflicts within the community. If residents used social violence to contest the development of Saint John’s symbolic, economic and built environment, then we may have to rethink the emphasis upon ethno-religious tensions and the ghetto in explaining the city’s social violence. What places did residents attack, parade, control and put to the torch? What do the places tell us about the nature of the troubles? Why were York Point and parts of Portland parish the settings for much of the crowd violence? What other places were involved and why?

11 This study proceeds by geographical association and correlation. An account of crowd events, parades, riots, fires and assaults in Saint John from 1840 to 1860 was compiled from three local newspapers, The Courier, Morning Freeman and Morning News. This account is by no means a complete catalogue, given the gaps in the newspaper record and the partiality of the observers, yet the events the newspapers did record can be situated on the terrain of Saint John to reveal some patterns. Work, meeting, public and other places stand as intermediaries between the events and the tactics, targets and strategies of the protagonists. The result is a discussion of Saint John as a terrain of conflict. By explicating geographic relations between town and crowd in the context of patterns of urban growth, the apparent anomaly between See’s interpretation and the evidence on ethnic segregation in Saint John may perhaps be unravelled. First, the pattern of urban growth 1840 to 1860 is discussed, and in particular the place of the "ghetto" in Saint John’s urban fabric. Then an examination of civic parades reveals a geographic context for the big riots in terms of a symbolic civic space and the meanings attached to parades, authority and disorder within that space. Analysis of several riotous incidents reveals a geographical patterning of locations for violence. From this analysis the troubles are best characterized as an ongoing negotiation of economic and symbolic identities. The conflicts are wider in scope than a simple Irish-Catholic vs. nativist confrontation. Most of the parades, assaults, riots and fires targeted specific places in a highly charged terrain in the city’s north end — a wider territory than the ghetto, and encompassing King’s, Wellington and Prince wards, as well as the parts of Portland parish adjacent to the city.

12 Although large-scale migration flows passed through Saint John, the city grew only slowly. The 1841 census enumerated 26,923 people in Saint John. From 1844 to 1847, 30,000 migrants landed at Partridge Island quarantine station. Although Saint John had the potential to emulate the spectacular population increases experienced in other European and North American cities in the 1830s and 1840s, the city did not experience such rapid urban growth. There were only 31,174 people in the city and adjacent parishes in 1851, and by 1861 there were 38,817 people.26

13 The ways in which Saint John figured in the mobility patterns of residents, migrants and country folk lie at the heart of Saint John’s relatively poor urban growth performance. Outmigration partly counterbalanced the immigration flow. Many of the migrants chose Saint John because it was a cheap destination on the Atlantic seaboard, and about one-third of the migrants moved on to New England. Others moved on to rural, town and city locations across the Maritimes and British North America. The census enumerators’ snapshots of who lived in Saint John miss many of those who floated in and out of the city as part of their daily, weekly or seasonal work migrations. Sound estimates of how many people moved between city and countryside are impossible, but many folk moved among public works projects, work on farms and in the woods, industrial jobs and fish work in the countryside, labouring in the city ports and sawmills and work in Atlantic shipping. Movements of predominantly working-age male workers among these seasonal job opportunities structured the Saint John economy and society.27 Economic activity generally lasted from April to November. The winter months saw the well to-do engaged in leisure and the poor in hardship, indoor relief or transience, while some found work in the woods.28

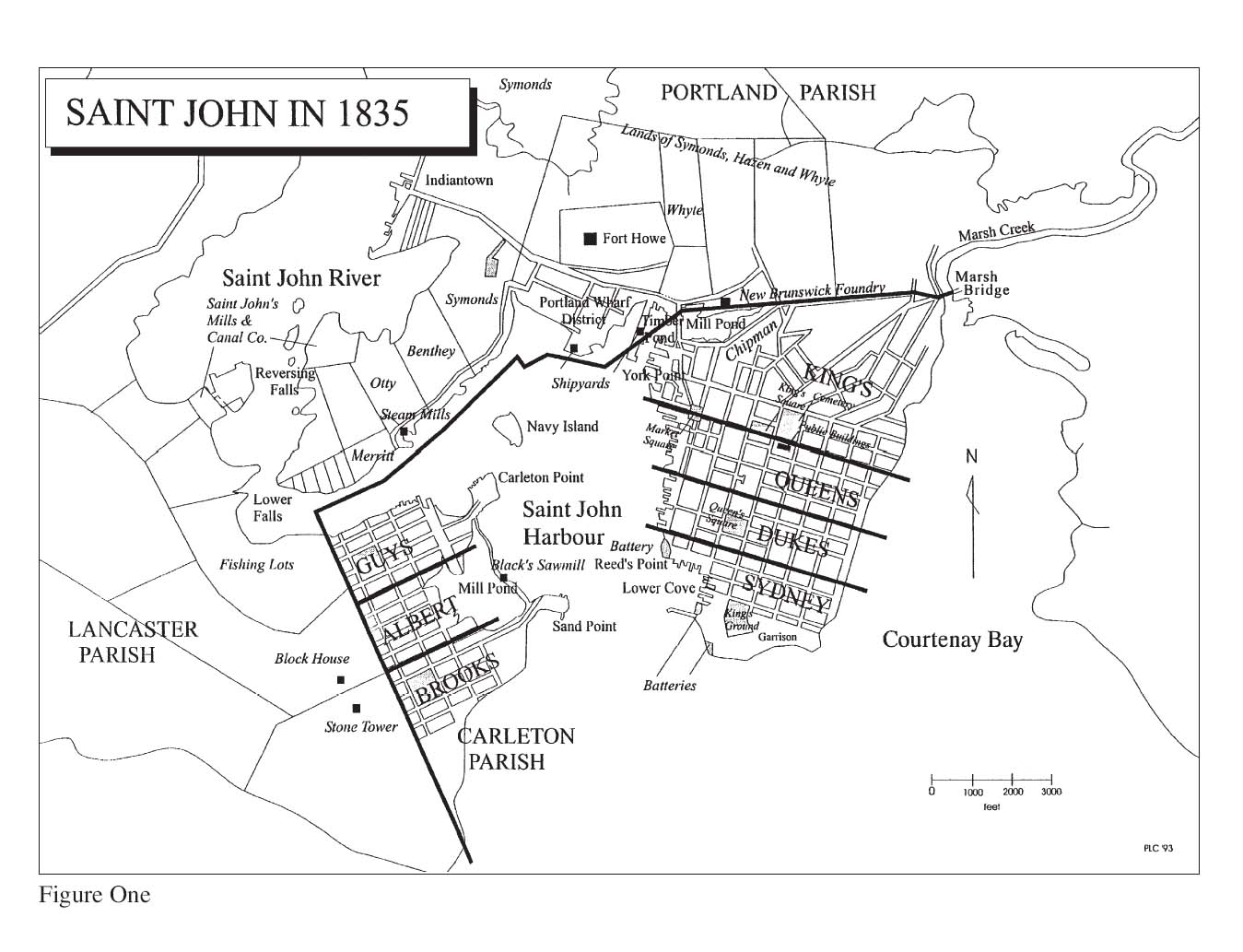

14 The city’s relations with the countryside and the slow pace of urban and industrial growth influenced the city’s built form. In 1841 Market Slip focused the city’s provisions trade (Figure One). Longshoremen unloaded goods from vessels for distribution by cart and dray from Market Square. Prince William and King, the city’s main commercial streets, ran to the south and east of Market Square. Sydney, Duke’s and Queen’s wards comprised the older parts of the city, with mixed populations of artisans, merchants, labourers, their families and servants. Large parts of King’s ward (soon to be subdivided into three separate wards) remained undeveloped. Portland comprised a series of rural landholdings with sawmills and shipyards along the waterfronts. Portland’s landowners set aside land for Anglican and Methodist churches. The New Brunswick Foundry indicated the area’s industrial potential. Carleton parish remained largely undeveloped. The military barracks took up the south end of the city. The military had abandoned or failed to maintain many of the fortifications scattered around the harbour. Spring timber drives on the St. John River provided the city’s staple trade. The 1851 census lists 26 sawmills, mostly clustered along the Portland and Carleton shorelines, and employing more than 700 men.29 Ship labourers, cartmen and draymen transferred timber around the port. By 1861 the city housed 1,600 labourers, but many others moved in and out of Saint John’s boarding houses.30

Figure one: Saint John in 1835

Display large image of Figure 1

15 As the city’s timber trade declined, Saint John developed a diversified economy comprising sawmills, shipyards, foundries, footwear workshops and clothing factories.31 The new enterprises were small affairs, and merchant enterprises continued to play a prominent role in the city’s economy. Most of the early enterprises focused upon the wharves, but by 1875 Sydney, Duke’s and Queen’s wards held only 16 per cent of the city’s manufacturing establishments. Industrial development concentrated in Portland (42 per cent), Carleton (12 per cent) and what had been the old (now subdivided) King’s ward (30 per cent). Completed in 1860, the city’s railway link to Shediac helped to concentrate industry in the city’s north end.32 Many of the factory owners, land owners and skilled workers took up association with the Mechanics’ Institute. Thus, new class relations and a cast of leaders with industrial rather than strictly mercantile interests eventually arose in the north end.

16 In terms of built form, Saint John grew only slowly during the 1840s and 1850s. The south end of the city saw very little construction. Development concentrated in the city’s north end where, in a pattern of intermittent building set back by devastating fires, a new landscape of small enterprises and private dwellings emerged among the existing developments. This emerging Protestant and artisan landscape overlapped with other activities. The warehouses and retail outlets of Market Square jostled with the Chipman estate, tenement housing, the liquor trade, tanneries, wharf activities, slaughterhouses and the city’s droving trade. Local juxtapositions of disparate locales distinguished the north end from the south end. The south end also recorded lower population densities: Sydney ward averaged 6.4 people per dwelling in 1871; the new wards subdivided from the old King’s ward averaged 9.9, as did the wards of Portland parish adjacent to the City. In Saint John’s development, discrete and homogeneous neighbourhoods did not emerge. Instead, slow growth of the new built environment resulted in a densely packed and complex north end social landscape, characterized by high levels of differentiation over short distances.

17 York Point and the Portland wharf district were diverse neighbourhoods nestled between the industrializing north end, the countryside, the wharves and the city’s commercial core. These were complex localities rather than ghettoes. York Point lay immediately to the north of Market Square, between the deep-water wharves, the mill and timber ponds and the Chipman estate. York Point had a concentration of "three-and four-storey buildings in narrow streets housing the poorest elements in the city’s population".33 These tenements offered low-cost accommodation separate from masters’ and merchants’ residences, at the centre of the largest concentration of labouring and industrial jobs, and right in amongst warehouses, slaughterhouses and retail outlets. Moreover, York Point was the centre of the licensed liquor trade, with 17 of the city’s 29 licensed wholesalers, and 22 of King’s ward’s 33 licensed liquor retailers. As a built environment, this western corner of King’s ward comprised a complex locality of tenements, and other residences, warehouses, docks, factories and retail outlets, short alleys, main thoroughfares and Market Square. Across the Mill Bridge in Portland lay a similar high-density district, although it lacked the liquor trade and merchant houses of York Point. The houses of leading Protestant landowners looked down on the wharves from the Douglas Road and the ridge line to the north. So while heavy concentrations of Irish-Catholics, the poor and itinerant labourers emerged in York Point and the Portland wharf district, the north end as a whole had no large and distinctive neighbourhoods and no well-defined internal borders. When immigration added strong group identities to this mix, the entire north end became a contested terrain.

18 Saint John could neither house nor employ the wave of Irish migrants arriving in the city during the 1840s. City authorities transferred migrants from quarantine to city wharves, to be discharged to friends and relatives living in the city or housed in sheds on the docks (Figure Two). Unless they had means or sponsors, immigrants remained in the care of city authorities. Many were transferred to the Poor House, the Alms House or Infirmary, "later to become wards of the community or forced to subsist by begging".34 The Alms House proved inadequate, and in 1847 the city built an Immigrant Hospital next to it. When authorities built a Provincial Lunatic Asylum, it too housed disproportionate numbers of Irish. When cholera swept through the city in 1854, the Board of Health established a Cholera Hospital in a barn on Fort Howe hill. Most of the 1,500 victims treated there were Irish Catholics.35 The locations of these new facilities further complicated the local geography of neighbourhoods on the edge of the city.

19 Within Saint John, Irish Catholics settled in each and every ward, but heavy concentrations appeared in King’s and Sydney wards. A large group of Irish-speaking Irish Catholics from Cork clustered in York Point, making this perhaps the most exclusive residential concentration of poor Irish Catholics in the city. Just how exclusive the area was as an ethnic residential quarter awaits further research, but this line of inquiry misses the key points: York Point was not simply a residential district; it was not surrounded by homogeneous Protestant neighbourhoods; and its relative location on main roads, docks and Market Square gave the area civic, commercial and labour market significance. Sydney ward had the lowest population densities in the city, so the ward’s high proportion of Irish Catholics did not translate into a big population.36 Protestant Irish also landed throughout the city, but in numbers in the north end. Within the city as a whole, Irish Catholics outnumbered Irish Protestants. In 1871, 5,196 Irish Catholics and 2,616 Irish Protestants resided in King’s, Prince and Wellington wards. The Irish Protestants more nearly matched the Irish Catholics in Portland (3,675 to 4,157) and in the southern city wards (2,362 to 2,385). Most of the migrants found housing in the north end, but, despite the cluster at York Point, it is hard to identify segregated ethnic neighbourhoods.

20 In most trades, newcomers found no foothold. Apprenticeships were costly and involved the transfer of skills and resources within extended family, church and other social networks. The majority of newcomers in the 1840s were not eligible. The one notable exception was in the Lower Cove, where successive contingents from proximate fishing villages in County Louth gradually secured influence in the city’s fish market.37 Irish Catholics in the north end faced stiff competition for labouring jobs. Predominantly from the south and west coasts of Ireland, they found no place in shipbuilding, coopering and the metal working trades. Among the 14 blacksmith shops in King’s ward in 1857, only two smithies were run by Irish Catholics. Only 11 of the 65 blacksmiths listed in the ward’s 1851 census were Irish Catholics, only one of whom had arrived in the city after 1840. Irish Catholics had some success in the highly politicized liquor trade, and they infiltrated carting, both activities subject to municipal licensing. In 1857, Irish Catholics comprised four of the 17 liquor wholesalers in King’s ward (only one of whom arrived after 1840) and seven of the 33 King’s ward liquor retailers. The 1851 census lists 83 cartmen in King’s ward where there had been only 40 in 1837. Of these 83 cartmen, 22 were Irish Catholics, 13 were Irish Protestants and 31 were Irish of unknown religion. Only six of the 69 immigrant Irish cartmen arrived in Saint John after 1840. It appears that this trade was hotly contested. As late as 1860, cartmen of King’s ward complained "that while men of other Wards and even from Portland, are constantly employed in King’s Ward, these residents are strictly excluded from all shares even in the road work".38 These modest achievements hint at harsh competition and discrimination in labour markets.

21 While their origins were different from those of the Lower Cove Irish, their position in the city labour markets also differentiated north-end Irish Catholics. Curiously, thousands of poor Irish Catholics located in the city’s north end, right in among the city’s new workshops, warehouses, wharves and main thoroughfares, only to be shut out of Saint John’s labour market. Patronage networks influenced access to both skills and employment. City patronage networks also dispensed relief. It is worth noting that the small black community housed in the Loch Lomond ghetto, Simonds parish, "received regular provincial aid from 1838 to 1848" and not just for the sick and indigent, but for education.39 Access to city, parish and provincial relief proved more difficult for some than for others.

Figure Two : Catholic Spaces - Landing the Irish Migrants

Display large image of Figure 2

22 Saint John’s associational life also took on a more complicated geography in the 1840s. Before the famine migrations, Irishness overlapped (in space) with other affiliations and was not particularly controversial.40 In the next decade, however, Catholic ultramontanism, Protestant evangelicalism, temperance, protectionism, Orange Order nativism and the famine migrations challenged both the number of meeting places and the city’s apparent social cohesion. In a city where associations had co-habited built space, they now built exclusive halls. Because of the slow growth of the city’s built structures, these were inevitably located next door to each other. The Orange Order flourished in each ward and parish. By 1846 Saint John’s Orange Order boasted ten city lodges, scattered around the city.41 Not one was located in an exclusively Protestant neighbourhood. Similarly, the Roman Catholic Church only gained sites for churches on the edge of the city. Initially, Catholics heard services in St. Malachy’s Chapel, Queen’s ward, and St. Peter’s church, Portland (Figure Two). The church built a chapel just beyond the Carleton parish boundary in 1847. The hall, convent and school located across the road in Carleton opened in 1857. The cathedral complex, built on Waterloo Street, opened in 1855.42 None of these churches centred a distinct Irish Catholic neighbourhood. Generally, each association built its own identifiable place of meeting, but ended up as a close neighbour to competing associations within an intricately differentiated north-end landscape.

23 In these different ways, Saint John’s urban growth involved a spatial sorting. The south end experienced little population growth, built few new industrial establishments and remained low in population density. The north end became a more contested terrain since it was the location for most of the new institutions and arrangements. The north end accommodated most of the Irish immigrants, along with industrial development and the older timber and shipbuilding economies. York Point and the Portland wharf district lay at the centre of this terrain. Together they comprised a high-density concentration of badly connected immigrants competing for labouring jobs. But these districts were not a large, coherent or homogeneous ethnic residential neighbourhood. The tenements, boarding houses and other rental accommodation were strung out behind the Portland waterfront, across the Mill Bridge, around the Mill Pond and down to Market Square. Warehouses, sawmills, retail stores, factories, slaughterhouses, lumber piles, cess pits, docks and private houses broke up and juxtaposed the tenements. The places and institutions of the Protestant Irish, industrialism and skilled workers surrounded this general area and intruded into it.

24 From this perspective, then, York Point and the Portland wharf district were complex localities, but their relative "location" complicates any attempt to identify the troubles of the 1840s with a simple Irish Catholic versus Orange Order confrontation. The tenements sat in a "new town" of industrial locales under construction in the north end. The city boundary with Portland parish cut through the district. The north end also boasted the city’s commercial and civic centres where citizens gathered to celebrate the city’s identity. New government buildings, some of them controversial, would all be built in the parishes surrounding Saint John City. York Point and Portland’s wharf district also happened to be the sites of the main thoroughfares connecting Saint John to the Atlantic and to the countryside, and the sites for most of the city’s accommodation for temporary workers. Large numbers of taverns, including some run by Irish Catholic proprietors, meant that King’s ward in particular housed the central places of unruly, male working-class sociability and solidarity. For all of these reasons, the north end would be the city’s most contested terrain. The salient features of this terrain were high levels of mobility and transience, and the absence of large, homogeneous, ethnic residential neighbourhoods separated by clearly identifiable boundaries. The specific (and micro-scale) geography of this north end shaped the identities, life chances, crowd events and parade routes that residents contested through social violence.

25 Residents hotly contested the new Irish presence in Saint John, but they also negotiated other identities and institutions. Civic parades celebrated the city’s major achievements: railway building, transoceanic telegraph laying, an industrial exhibition. Conflict took varied forms. Orange-Catholic violence took centre stage, but residents also engaged in assaults and riots, protests against prohibition,43 attempts by trades unions to regulate work and protests over the handling of the 1854 cholera epidemic. Mechanics protested against an offensive play. Arsonists torched buildings, and crowds engaged in riots and looting at fires. Factories and warehouses lay outside civic symbolic space, and crowds did not gather there, but factories did burn in suspicious fires. In combination, these incidents force a broadening of our interpretations of Saint John’s troubles. Not only was the social violence broader than the Orange-Catholic clash, but social violence proved to be the usual avenue for settling disputes. Time and again, the local geography of the city sited and shaped the social conflicts. Time and again, the protagonists who resorted to these tactics did so in the city’s north end. The making of civic symbolic space in parades, the general pattern of assaults and riots, the opposition to the Board of Health’s activities during the 1854 cholera epidemic, the struggle by labourers to control work hours on the docks, the riot at Hopley’s Theatre and the city’s record of fires all stand out as examples of how social issues were negotiated in the city’s streets and squares.

26 Through parades especially, citizens constituted a civic symbolic space and defined citizenship. Increasingly, parades in Saint John celebrated Loyalist, Protestant, merchant and skilled worker identities, as well as temperance, industry and civic authority. During the 1840s, marchers chose new gathering points and parade routes. Citizens embarked on parades rather than settling into celebrations and feasts at the city’s squares, and they organized teetotal soirees to bring order to festivities in the squares.44 Parade routes began to link King’s Square with Portland. Orangemen, firemen and mechanics took over the role of marching from the military. Representations of Irish Catholic and labourer identities were confined to celebrations of temperance, to religious places and to crowd gatherings rather than parades. Denied a place in the civic pageant, Irish Catholics disrupted the most overtly exclusionary celebrations. They could do so because York Point straddled the emerging parade route of civic pageantry.

27 King’s Square provided Saint John’s central civic space. The royal salutes, Queen’s birthday and coronation parades of 1838 to 1840 were all performed there.45 Military units fired saluting volleys and paraded through the city streets to or from the barrack grounds and King’s Square, with the North Market Wharf and Queen’s Square figuring prominently in the routes. Annual inspections of the militia companies took place in King’s Square and the Barracks Square.46 Election crowds gathered outside the Court House in King’s Square. The victorious candidates in the 1843 provincial election rode sleds through the wintry streets to celebrate their taking of the town.47 For these and other civic occasions, the Common Council set up ale and provisions in King’s and Queen’s Squares, and the days’ events degenerated into drunkenness.

28 Innovations began in 1838 when temperance supporters set up their own soirees featuring coffee and tea but no alcohol. The 1840 procession to lay the corner stone of the Mechanics’ Institute, Germaine Street, mustered in King’s Square, but featured a new cast. Civic officers, the Lieutenant-Governor, clergymen and the officers of the Mechanics’ Institute replaced the usual military parade.48 Following controversy in the 1843 provincial election and the 1848 King’s ward election, officials spread polling for the 1849 provincial election throughout the city wards, in order to disperse the election crowds.49 The papers reported few incidents at election meetings and crowds did not figure prominently in the city’s elections, but when they did, it was in King’s Square.

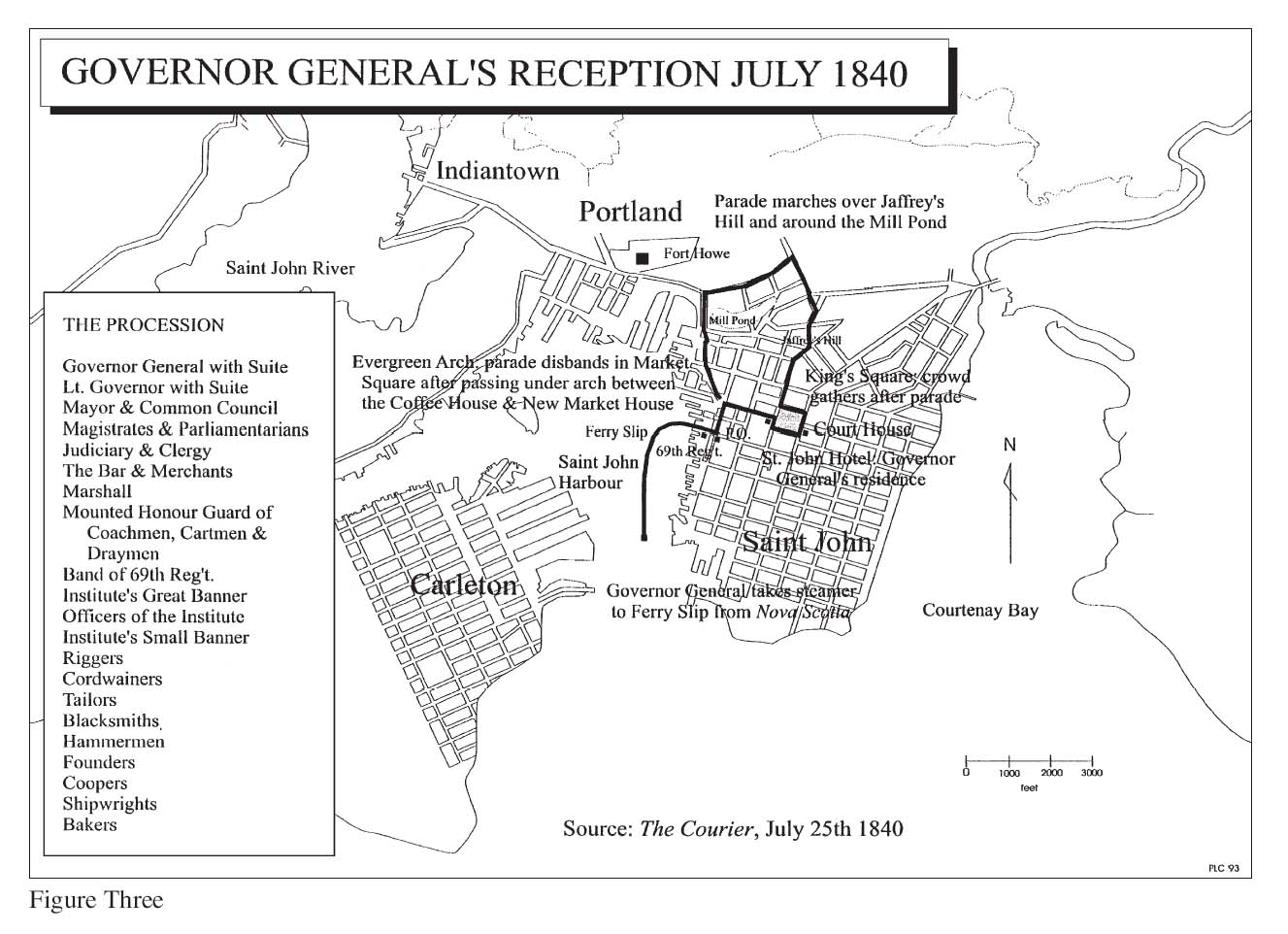

29 Increasingly, parade routes linked Portland to King’s Square. The July 1840 reception for the governor-general set the precedent for later parades circling through Portland (Figure Three). For this parade an arch of evergreens connected the market and coffee houses in Market Square. The parade passed under the arch before proceeding along King Street, over Jaffrey’s Hill and through Portland by way of the Mill Pond. Marchers returned to the city via the Mill Bridge and Dock Street and again passed the arch as they entered Market Square. There the parade disbanded but a large crowd gathered outside the St. John Hotel, King Street, where the governor-general was to stay.50 Subsequent parades in the 1840s and 1850s regularly crisscrossed the city’s northern border with Portland parish. By including Portland in parade routes, marchers indicated the growing importance of the parish, its businesses, landowners and institutions in the city’s development. The Orange Order parades of 1842, 1847 and 1849 each featured a procession through Saint John City and Portland.51 Similarly, the temperance procession of May 1851 "perambulated some of the principal streets of the City", Portland and Indiantown, before returning to King’s Square for speeches and an evening soiree at the Custom House.52 In opening the Industrial Exhibition of 1851, the parade followed a similar route, but featured a "water demonstration" as a fountain played for the first time in King’s Square.53 Indeed, one columnist commented over the omission of Portland in the royal parade route arranged for Prince Alfred’s visit in 1860. King’s Square featured prominently in the reception for the Prince of Wales, who stayed at the Chipman house in King’s ward.54 The pavilion erected at Reed’s Point for the Prince’s arrival and his send-off at the railway’s Nine Mile Station mark new points for arrivals and departures.55 In 1859 the regatta shifted to the Kennebecassis River.56 The openings of the Intercolonial Railroad depot and the sod turning for the European and North American Railway further focused civic parades in the north end and in Carleton.57 In Saint John’s space for civic pageant and theatre, Portland parish figured more and more prominently as the city spilled over its northern boundary.

Figure Three : Governor General's Reception July 1840

Display large image of Figure 3

30 Protestants dominated the parades. In the 1840s the Mechanics’ Institute (whose band comprised Orangemen) and the Orange lodges gradually eclipsed the militia as the chief marchers. In the early 1850s, the new fire companies took prominent places in civic pageants. Fire Engine House No. 2, on King’s Square, hosted the 70th anniversary celebrations of the Loyalist Landing.58 A Queen’s Birthday parade dedicated new fire engines for Carleton.59 In contrast, Irish Catholic parades showed less access to Saint John’s symbolic space. In the St. Patrick’s Day celebration of 1842, about 1,000 people wore the green sash in a "Teetotal Procession", but the crowd did not proceed out of King’s Square. After an address the marchers retired to their homes.60 Saint John Catholics gathered at the cathedral site in 1853 to dig out the foundations, but no parade occurred.61

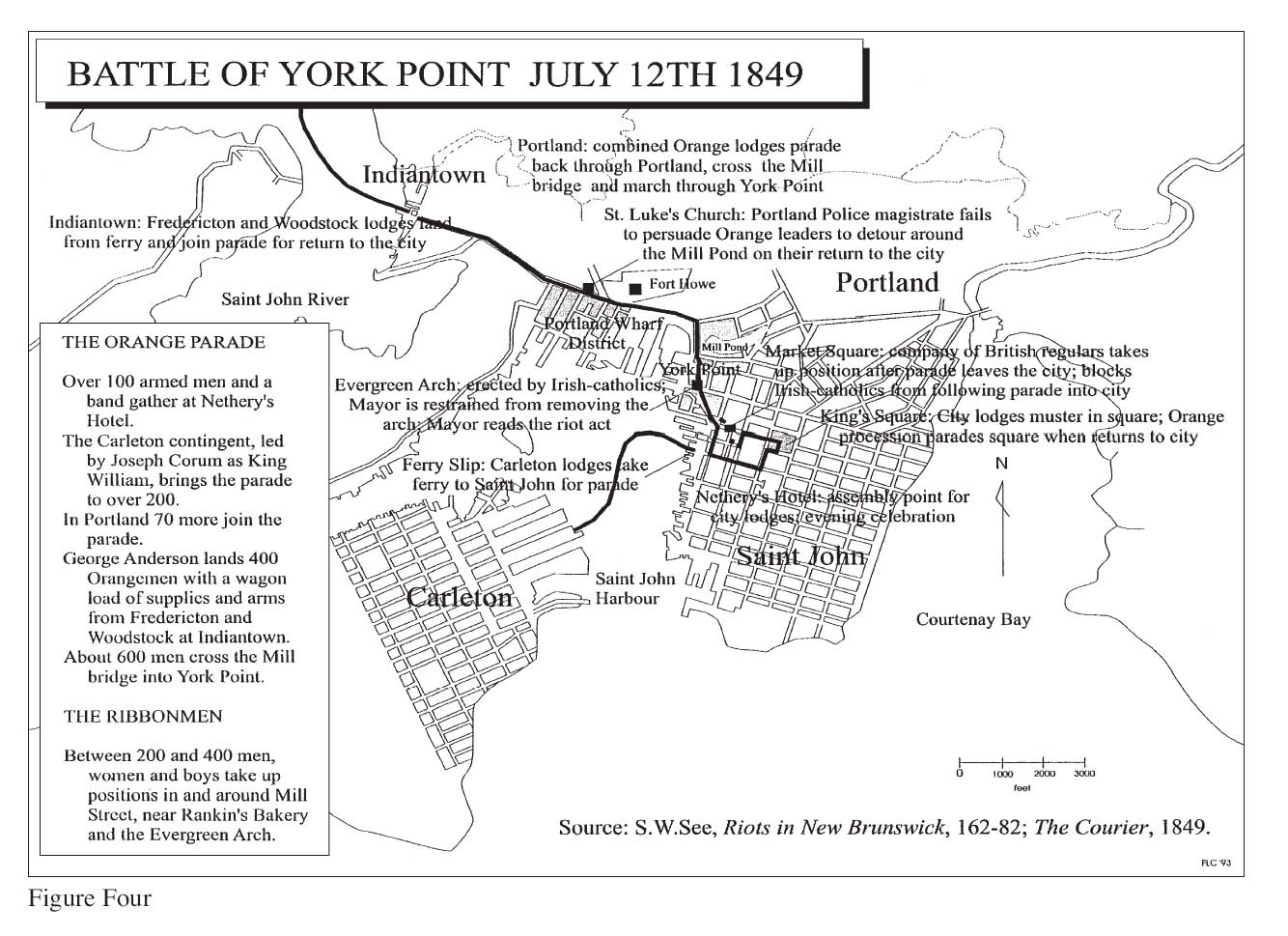

31 The city’s two major riots occurred in 1847 and 1849 as Orangemen chose 12 July to parade through the city and Portland with the Mechanics’ Institute and Wellington Lodge (Portland) bands.62 For the 1849 occasion (Figure Four), Orangemen from the city and Portland gathered at Nethery’s Hibernian Hotel before marching to the ferry slip to meet their Carleton supporters. The parade marched north into York Point, where an evergreen arch set up across Mill Street forced the marchers to dip their banners. Decorated with symbols that were anathema to the Orangemen, the arch signified Irish Catholic supremacy in the street and city just as the arch between coffee and market houses featured in the governor-general’s reception of 1840 signified merchant supremacy. Generally, civic arches signified the power and authority of the hosts of the parade. Passing into Portland, the column received armed reinforcement from Portland, Fredericton and Woodstock contingents. Undeterred by Portland’s police magistrate, the parade leaders changed their return route to the city, marching instead back into York Point. In the ensuing melee on Mill Street, Orangemen cut down the offending arch.63

Figure Four : Battle of York Point July 12th 1849

Display large image of Figure 4

32 By taking the form of (armed) civic parades, the Orange marchers situated the conflict in symbolic space. They marched to declare the city and Portland to be Protestant and Loyalist. Some Irish Catholics contested this representation by erecting an arch over the parade route and decorating it with competing symbols. Thus, they challenged Orange rights to march and the idea that Saint John was Protestant and Loyal, implicitly declaring York Point independent from Orangeism and perhaps the city corporation as well. The arch invited Orange response, and Irish Catholics turned out to defend it. Arches featured in related controversies in other Canadian cities. The Prince of Wales’s visit to Canada in 1860 sparked a series of incidents in Belleville, Kingston, Aurora and Toronto, as the Prince’s advisor, the Catholic Duke of Newcastle, refused to receive addresses from representatives wearing Orange insignia or to parade under arches decorated with Orange emblems. Ontario Orangemen vowed to practise their right to "arch and march".64 The Saint John riots took place in York Point, but, with no clearly defined ghetto to defend, the riotous Irish Catholics asserted their own identities in the city’s symbolic space. They did so through parody of the normal symbolism of civic, and especially Orange, parades.

33 Small wonder that York Point witnessed the major clashes. York Point sat astride the key thoroughfare between Portland and the city — a thoroughfare of symbolic importance in Saint John’s theatre of the crowd. The city’s Protestant mechanics and Orangemen had increasingly dominated civic symbolic space. Irish Catholics were denied entry to Saint John’s symbolic world. York Point Irish protested civic displays through parody and physical disruption, but they could not stop the ongoing celebration of Saint John’s civic identity as Protestant, Loyalist, industrial and mercantile. York Point lay at the heart of a contested labour and housing market, but the big riots did not seem to have any direct connection to efforts to achieve or break free from residential segregation. In the 1849 battle, Irish Catholics did not so much "defend their territory" against invading forces intent on pillaging resources or evicting tenants, as seek to disrupt the parade and thus contest Orangemen’s claims to control over the city’s symbolic space. Indeed, the battle is inappropriately named, as only from an Orange and symbolic point view was this a battle to secure York Point. These riots have perhaps received undue attention because of their size, but their main significance lies in the geography of the city’s symbolic space and the way in which this shaped conflict. Certainly, there was no cessation of social violence when the Orange lodges ceased to parade after 1849.

34 Locations in the north end figured prominently as sites for assaults and riots. General rioting with attacks on property was concentrated in York Point and Portland.65 However, there are few reports on the specific properties attacked, and therefore the precise nature of the violence, its causes and targets, remains elusive. Crowds attacked officials and other would-be participants who tried to interfere.66 Rioters saw off the mayor in both the riot of July 1855 and the York Point battle (Figure Four).67 Many of the assaults were on men crossing the Mill Bridge. A visiting sea captain romanticized these attacks as a series of contests each time someone carried a sword cane through York Point.68 Sometimes the confrontation was abusive rather than physical, as with the crowd that abused Alexander McLeod, newspaper editor, on his visit to the city in 1842.69 The authorities in Portland were partisan, and watchmen were assaulted on Christmas Eve 1844.70 This attack served as prelude to a week-long occupation of the Mill Bridge by a 200-strong Irish Catholic crowd. Soldiers cleared the bridge on New Year’s Eve. The crowd’s nocturnal bridge occupation blockaded "particular enemies", but it is unclear just who these enemies were.71 Catholics carried out several assaults in Mill Street, Simons Street and York Point in 1847, beginning about the time of 12 July celebrations.72

35 In addition to the big riots, Orange-Catholic violence took the form of assaults and general rioting on or about Christmas, St. Patrick’s Day or 12 July. Riots during the slack winter months testify not only to holy days as occasions for ethno-religious clashes, but also to the presence of many men, out-of-work, hungry and perhaps angry over poor access to firewood, liquor or relief. York Point featured strongly in this violence, but assaults spilled over into surrounding districts. Orangemen attacked the McAvoy party while they were out on a picnic in Lancaster Parish.73 Catholics loitered outside lodges to identify Orangemen.74 Much of the Orange-Catholic violence occurred on one side or other of the city-Portland boundary at or near the Mill Bridge. Although the bridge did not join a homogeneous and exclusively Protestant Portland Parish to an exclusively Irish Catholic York Point ghetto, the violent activities around it generated the idea of a symbolic border. Lack of adequate policing on the Portland side facilitated both the violence and the emerging mental map. The assaults and riots, See notes, "proved neither indiscriminate nor uncontrolled. Catholics and Orangemen went armed if they crossed into each other’s territories, and carefully picked fights only with ‘certain . . . obnoxious individuals’",75 but it is unclear what comprised these "territories".

36 Two possible explanations of the Orange and Green territories can be discounted. Perhaps the assaults and riots stemmed from a group of Irish Catholics using York Point as a base for attacks on particular individuals and resources in surrounding areas. Alternatively, outsiders used "York Point" as a category to define a target for violence. Problems of transience, seasonality, resistance and lack of cohesion in the tenements cut across any sustained development of an exclusive, homogeneous and militant ghetto in York Point. At best, their "territory" could be established only at night and during the winter months when work was scarce. At worst, their "territory" was both undefendable and unidentifiable. Note that the York Point tenement residences were seldom themselves the targets or locations for assaults and riots. For contrast, in Manchester’s Little Ireland, "attempts to serve legal executions for rent, debt, or taxes, had to be conducted like a minor military action against an embattled population".76 Most of the misrule in Saint John occurred in the street, especially on the main roads or outside prominent individuals’ houses, sometimes located in Portland, at other times in King’s ward, but not in York Point. These actions tended to target individuals and symbols rather than territories. Named for a dockside slip, "York Point" is itself something of an obfuscation. By referring to an unofficial neighbourhood, newspaper editors avoided naming individuals and specific premises, and thus obscured the identities and practices involved, but they also generated the idea of a (very small) ghetto as a symbolic problem area.

37 Although the sectarian clash did not feature clearly, Portland and York Point continued to figure prominently in the assaults and riots of the 1850s. Indeed, most of the city’s attacks occurred in the north end.77 A riot at the Portland watch house in 1851 featured firemen.78 Vandals attacked St. John’s church in 1857.79 A fight at York Point between Kearns, O’Neil and McCarthy, and general rowdyism over Christmas 1858, continued the violence.80 A crowd attacked the militia and band when they marched up Mill Street in Portland in May 1860.81 These were violent times in the country too. The Slavin murders on the Black River Road in 1857, and a stabbing in Gore’s still-house at Golden Grove in 1859 testify to the transience connecting Saint John with its countryside. While the Slavin murders were not strictly speaking examples of social violence, they confirmed "for ‘respectable’ New Brunswickers that many of the lower orders literally lived in another world",82 and that Saint John’s troubles persisted into the 1850s.

38 While these assaults and riots lacked the intensity of the big 1840s events and any explicit connection to sectarian violence, their locations were similar, as were the identities of some of those marching. The identities of protagonists are not always clear, as with the city’s circus riots. Two apprentices caused a circus riot at the corner of Wellington and Carleton streets in 1841.83 Police exerted a measure of control during another circus riot near the Valley Church, Portland, but this was a rare event.84 A similar circus riot occurred in Toronto, where Kealey has established fire company and Orange Order affiliations among the riotous crowd, who "acted as a community enforcer acting on unwritten codes of moral economy".85 Such affiliations are hidden in reports of the Saint John circus riots, but these may well be incidents of a type. There are hints in the assaults and riots of the 1840s and 1850s that diverse local issues were hotly contested in the city’s north end as Orangemen, mechanics, firemen, tavernkeepers and other Protestant plebeians used violent means to impose order, and that they were resisted. These and other incidents suggest that we must look beyond the obvious badges and apparent territories if we are to explicate patterns of social violence in the north end.

39 The riot at Hopley’s Theatre crystallizes other elements of the troubles in the north end. A disreputable theatre in a disreputable neighbourhood, Hopley’s stood next to the Golden Ball tavern on a major east-west thoroughfare on the border between Prince and Wellington wards.86 Hopley, an Irishman, staged some professional theatre, but otherwise featured amateur groups and Irish pieces. In April 1845, Hopley’s staged "The Provincial Association", authored by Thomas Hill, editor of Fredericton’s Loyalist. The play satirized the protectionist political forces in Saint John. Riots ensued on the first two nights as mechanics attempted to suppress the play. The protagonists left their sashes at home for the riot at Hopley’s Theatre, turning up as mechanics instead.87 The mayor ordered an end to performances, but Hopley’s opened unopposed several nights later. A crowd then thoroughly vandalized the theatre in another riot.88

40 The significance of the theatre riots lies only partly in the theatre’s and the performance’s "location" in contested terrain, and the apparent friction between erstwhile Loyalist allies Hill and the mechanics. Civic pride demanded that Saint John have a respectable theatre. Once the mechanics demonstrated that "protection" ruled Hopley’s Theatre, it was up to the merchants and gentry to establish a respectable theatre in the city that they ruled. The new Prince of Wales theatre opened in June 1845. By locating the theatre on the more respectable corner of Duke and Sydney streets, promoters meant the theatre to "be convenient to the wishes, convenience and accommodation of the gentry of Saint John".89 When this theatre burned in December 1845, some commentators suspected arson, while others blamed poorly fitted stove pipes.90

41 Saint John theatre remained amateur and closeted in association halls until 1857. In that year Lanergan’s Dramatic Lyceum opened on the south side of King’s Square, and the Royal Provincial Theatre opened on Prince William Street. Both theatres attracted respectable audiences. In 1870 "leading citizens" planned a grander theatre to be called the Music Academy.91 In the early 1850s, the Mechanics’ Institute and the St. John Hotel staged theatre, but the directors of the Institute would not permit regular performances. The riot literally meant that theatrical performances were subject to censure (by the city’s mechanics). Together, the riot at Hopley’s, the fire at the Prince of Wales and the new theatre openings removed professional theatre from the contested north end terrain, placed it in carefully controlled spaces in Queen’s ward, south of the civic centre, and made theatre into a pastime of the respectable. These moves are reminiscent of the spatial tactics inherent in building the Paris Opera House.92

42 As in the Battle of York Point, crowds rioted at Hopley’s Theatre in a conflict over representation in civic symbolic space. In this case, mechanics disrupted the theatrical representation of themselves by trashing the theatre. By doing so, they gained de facto control over theatrical performances for a decade or more. It took time for respectable residents to establish a new professional ordering of theatre-going by building new theatres. Thus, the city’s built form proved to be more than simply a setting for social violence. Theatres themselves were media for cultural representation, and they thus became targets for social violence in a conflict over symbolic representation. The geography of theatres bore no relationship to the concentration of tenements, and the theatre riot shows that major riots erupted at sites within the north end other than the "ghetto".

43 Longshoremen tried to write their presence into the landscape by having bells erected on the city wharves to ring out the work day. Their tactics included gathering a crowd and establishing authority through control of a public monument erected in the street. The longshoremen located their bell in a highly symbolic space: in the Market Square, surrounded by merchant warehouses and other centres of merchant status and activity, in amongst the carters’ wagon berths, at the head of Market Slip and thus adjacent to many shipping berths, within sight of the York Point tenements and King’s Square, and on the main civic parade route. Violence did not feature in the longshoremen’s campaign, but, unsurprisingly, city merchants contested their first use of the wharf bell. After all, the bell was located in their symbolic territory and directly threatened their authority in the work place.

44 Workers established three trades unions in 1849: the Longshoremen’s Labourers’ Society, the Saint John Ship Carpenters’ Society and the Saint John City and County Sawyers’ Society. See interprets these associations as reactions by the city’s established artisans,93 but one of these unions organized across religious lines. The Irish Catholics James Muldoon and Jeremiah Sullivan were prominent when 400 labourers gathered in Jacob’s Long Room to form the Longshoremen’s Labourers’ Society. The longshoremen campaigned against patron-client relationships at the docks. The labourers’ causes included a minimum wage of 4 shillings a day and a ten hour day. They erected a bell at the head of Market Slip so that the work day could be sounded. The alliance of Catholic and Protestant labourers also demanded a ban on work for stevedores.94 Merchants of the North and South Market Wharves successfully petitioned Common Council for a by-law forbidding ringing of the bell, but this opposition proved ineffectual when one merchant broke ranks to ring the bell. Beginning in 1851, another bell rang in Carleton’s Market Square.

45 The wharf bells symbolized the triumph of labour solidarity over the merchants. They erected a monument to worker solidarity in a central, merchant-dominated, public square, and they gained the right through this appropriation of space to control the timing of work. This triumph of brotherhood among labourers coincided with the calls from Catholic and Orange associations. Around the corner from Market Slip lay York Point, scene of the major confrontation between the Orange lodges and Irish Catholics the very same year the first bell was erected. The union’s wharf bell illustrates the multiple codings of particular places in the north end, as well as the centrality of public space in negotiating residents’ lives. Although violence did not feature in this struggle, the controversy over the wharf bell is symptomatic of the struggles over the north end terrain by many different groups, each trying to gain control over resources. Residents seldom fought over access to housing. More often, they fought over authoritative symbols located in public space.

46 When housing did feature in a prominent social issue, the cholera epidemic of 1854, Saint John citizens negotiated the issue in the streets, alleys and tenements by resorting to social violence. The events surrounding the epidemic indicate just how complex the residential, work and sanitary terrain of the north end were. On this issue, participants made no particular mention of York Point. Indeed, the epidemic ravaged the entire north end. Even so, specific buildings and enterprises, rather than a broad homogeneous territory, became targets for vandalism, cleansing and removal.

47 During and after the 1854 cholera epidemic, in which perhaps 1,500 people died, the Board of Health imposed new bureaucratic measures on the city. The board endeavoured to cleanse the city by washing down the streets and tenements, burning tar to purify the air, establishing a cholera hospital and removing pigs and slaughterhouses from the city.95 The board’s efforts met with opposition, and partly because of the geography of the epidemic. Even though the first cholera victim died in Duke’s ward, the streets hardest hit were all in the north end of the city. Following a thunderstorm, the cholera cases spread north to York Point, Mill Pond, Portland and Indiantown, and eventually to Loch Lomond. The epidemic spread through the north end, and, in this contested terrain, the board ran into opposition. Residents attacked the meeting hall chosen by the board as their preferred cholera hospital site and the board eventually used a barn at Fort Howe instead. Only those who had no home in the city could use the hospital, and thus its patients were overwhelmingly Irish Catholic. Although the barn was close to the worst affected areas, it lay outside the city limits. Citizens called for the closure of slaughterhouses and the dead house at the city jail. Dissatisfied with the lack of action, "inhabitants of St. Patrick Street . . . launched a demonstration on 20 July and threatened to tear down the slaughterhouses. Only with some difficulty was a riot averted".96 Other residents abused the board’s inspectors when they tried to impose fines on those keeping dirty houses and pigs. When the board called for one Mr. Flaglor to clean up his alley — where 200 people lived over a cesspool — he refused. The board did the job at public expense, but the tenants petitioned the provincial government over the board’s "arbitrary action". Riot and abuse greeted the city authorities when they endeavoured to solve the problem at the tenants’ expense. The editor of the Morning News sanctioned this use of social violence: "If people must take the laws into their own hands, the authorities will only have to blame themselves. In such cases the authorities would know how to make use of the Policeman".97

48 "Bureaucratic" measures were not neutral. The board targeted poor families and tenement dwellers, but left slaughterhouses running. Residents associated cholera with tenements, and the Morning News reacted by investigating (false) intelligence that the source of the pestilence was in tenements in the Lower Cove. The editor blamed the board for not acting on its orders to drive pigs and slaughterhouses from the city and blamed the water company and the Council for the dry water plugs that prevented cleaning of Mill, St. Patrick’s and Brussels Streets. The newspaper demanded that the board "send men into all the slums and filth holes about the city, and have them cleaned out, and charge the landlords, no matter what the cost".98 Of course, the board’s prospects for fixing the cost on landlords were bad. Further, Geoffrey Bilson implies in his study of the epidemic that bitter controversies over Mayor James Olive’s refusal to grant liquor licences, and over the poor performance of the Saint John Water Company, contributed to the board’s frustration. Residents resisted the board’s bureaucratic solutions. Moreover, the intricate social and physical geography of the north end’s streets and alleys shaped the conflict over cholera measures. The tenements were hard hit, but cholera struck throughout the north end. Decent citizens protested to get action because they lived in among the slaughterhouses and tenements. The board had to locate the cholera hospital in Portland because some city residents resisted attempts to commission a hospital in their neighbourhood. In resolving the issues surrounding public health, various groups of residents resorted to protest, violence and court action, and in the process they thwarted any effective response to the epidemic.

49 Saint John and Portland burned, especially in the 1850s. A reading of the Courier reveals 207 fires between 1840 and 1864, including 34 arson cases and 115 fires of unknown rather than accidental cause. Even if this was a comprehensive list, it is difficult to explain these fires or their significance, and commentary must be speculative. Arson can be a tactic in social violence but it can also have other associations, and it is seldom discussed in the literature on crowds and riots. Many fires are accidents, and unsafe fires and stove pipes contributed to many blazes among Saint John’s wooden houses. Nevertheless, the partial account gleaned from the Courier reveals some interesting patterns, especially when set against the patterning of Orange-Catholic violence and other lines of conflict.

50 In terms of the number of fires, 1858-61 were the worst years, and accounted for 12 of the 34 arson cases. The most destructive fires were all in the north end. A fire in November 1850 consumed 122 dwellings in Prince and Wellington wards. Two fires in 1851 together destroyed 57 Portland buildings. Other Portland fires in 1857, 1858 and 1864 together razed 154 more dwellings. Winter and the riot seasons coincided with the worst months for fires. Generally, May had the most fires, followed by December, January and March. However, the arson cases show little correspondence with the record of riots. May and October were the worst months for arson. Arsonists also struck in December, February and September. The most important discrepancy with the record of riots is that so few fires were reported in the 1840s. Moreover, of the 45 fires reported in that decade, nearly two-thirds were in Queen’s, Duke and Sydney wards. Seven of the ten arson cases were fires in the city’s south end. Apart from the Mechanics’ Institute Hall, a stone-cutting business, a shed and a barn, the arson targets were all dwellings, and there seems little to link the record of fires to the sectarian violence of the 1840s.

51 In the 1850s, however, it was the north end that burned. Portland and King’s ward together accounted for 68 per cent of the 107 fires recorded by the Courier during the decade. They also accounted for 11 of the 15 arson incidents. The incendiaries’ targets included the Cholera Hospital in May 1857 and Carleton’s Temperance Hall in January 1858. A total of 26 dwellings and a barn in Portland, and three dwellings in King’s ward burned in other arson cases. Moreover, while firemen declared 49 per cent of the 1840s fires "accidental", they confirmed only 28 per cent of the 1850s fires as accidental. More than 70 per cent of the 62 fires with unknown causes burned in the city’s north end and Portland. These fires of unknown cause consumed prominent enterprises in the north end, including mills opposite Indiantown and at Spar Cove, a carriage factory, shipyard, pail factory and cabinet makers’ shop. Twenty-seven stores burned in the December 1851 fire on Portland’s Commercial Wharf. In 15 other fires of unknown cause, 64 Portland houses burned. In King’s, Prince and Wellington wards, such fires consumed a steam saw mill, livery stable, clothing store and foundry. Six houses, two stores, a stable, barn and outhouses burned in nine other King’s ward fires. Also, in November 1853 the Immigrant Hospital burned down in a fire of unknown cause.

52 The city’s north end blazed from September 1858 to May 1859 in a reign of terror that smouldered on to 1864. Following arson fires among Portland houses in September and October 1858, unexplained fires consumed a tannery, shanties in York Point, three dwellings in Indiantown, the Portland gas house, a house on the City Road, four dwellings by the stone church and two dwellings in Portland’s Paradise Row. Then seven buildings went up in smoke on the Long Wharf in a premeditated fire. In April and May 1859, seven more fires consumed an office in Portland, eight dwellings in Indiantown, a mill and three houses in Portland and a shipyard near the Marsh Bridge. Later that year arson destroyed a cottage and barn opposite the Portland Engine House. Five more arson cases lit up the city’s north end in 1860. In June 1864 someone fired a barn in Golden Grove, a rural seat of the Orange Order. Unexplained fires in June and December 1864 consumed seven Main Street and 97 Portland houses. Unexplained fires also consumed the Lower Cove fish market, a fish house on Navy Island and Carleton’s fire engine house and Temperance Hall, but Portland and King’s ward locations figured overwhelmingly in these deliberate and suspicious fires.

53 It is impossible to assign causes to these fires, and the inventory of arson targets, suspicious fires and collateral damage is at best suggestive. Factories, association halls, hospitals, houses, stores, barns and offices all burned. It is impossible to associate Orange-Catholic violence with specific fires. The burning of the cholera and immigrant hospitals and of the fish market resonate with Irish subtexts, but there is no hard evidence. A fire in Portland could have various nefarious implications. Perhaps incendiaries or careless workers burned the assets of merchants, sawmillers, shipbuilders and factory owners? Maybe residents settled scores in the liquor trade or with fire companies? Perhaps old scores from the 1840s riots remained to be settled? Is it conceivable that owners cleared out their tenants? There is insufficient evidence to demonstrate the significance of any of these possibilities. Nevertheless, the spate of arson cases in 1858-60 indicates misrule of some kind, and the location of the fires in Portland and King’s ward signals that the tensions behind the vandalism grew out of the volatile social mix of this north-end community.

54 Fires in Portland did provide occasions for collective social violence in the form of fire-fights. Arsonists set fires, which partisan fire companies, police magistrates and crowds presided over, and this occasioned crowds and looting, as well as water fights and quarrels among the fire companies.99 Unlike the weekend "fire-fights" among Philadelphia’s fire companies,100 the Saint John fire incidents had sinister connotations because residents accused the fire companies of abandoning the fires to participate in the fights. Riots were commonplace at fires in Portland in the late 1850s.101 The Morning Freeman gives several different accounts of the riot at the fire on Portland’s Long Wharf, but found that Portland engine companies threatened city firemen who tried to fight the fire. Once the fire was out the Portland companies attacked the city crews, and later that night rioters picked another quarrel in York Point. Patrick Bogan, a resident whose house was saved, locked himself in his house to prevent looters and firemen entering. Later, he denied any foul play.102 Fire-fights also broke out between city engine companies.103 The Snow Birds, a gang associated with Number 2 Engine Company, conducted various acts of misrule through the late 1850s and early 1860s.104 As the new fire companies became more prominent in civic parades they also became the centres of riot activity and vandalism. Newspapers report two break-ins at Number 6 Fire Company.105 The fire companies became prominent in the city’s social violence after the Orange lodges’ role diminished. Equipped with new engines, civic status, prestige and Orange Order linkages, these companies constituted authorities in the streets and became associated with vandalism, crowds and riot. Volunteer firemen played a similar role in Toronto in the 1850s, where firemen engaged in fire-fights, and the "fire-bells, under the control of Orange fire companies, were the standard Orange call to arms".106 Far from introducing a professional bureaucracy, Saint John’s new fire companies of the 1850s remained tainted by the old patronage networks and perhaps continued the business of the 1840s riots. Residents persistently undertook acts of misrule to subvert "professional" and "bureaucratic" answers to urban problems, and firemen carried out social violence as they participated in local vendettas and patronage politics.

55 York Point residents did not gather in crowds to defend their neighbourhood against fires, arsonists and fire companies. In the 1850s, fires consumed large swaths of the north end and particularly Portland rather than York Point. Residences featured in the associated acts of misrule, but unless York Point residents ventured out to attack sites in Portland from their base in the city — a scenario for which there is no evidence — then York Point has little significance in the events. Acts of arson and misrule associated with fires were keyed to particular buildings, widely scattered across the north end. The geography of these activities casts doubt on the idea of York Point as an enduring or pivotal feature in Saint John social violence.

56 Saint John residents hotly contested representations in civic symbolic space, and this is a principal reason why particular places in the north end figured prominently in the troubles. Competing assemblies struggled for civic representation and dominance. Since groups gained civic status through public performance, protagonists contested parades and other symbolic representations. At issue was who was to have official sanction as an exemplar of civic solidarity. Parades celebrated the city’s Protestant, Loyalist and industrial future by parading through Portland. Mechanics and firemen marched to celebrate the new railways, transoceanic telegraph lines and fire halls. As citizens renegotiated Saint John’s "theatre of the crowd", the north end came to house all of the city’s civic spaces. Crowds and parades therefore concentrated in King’s ward and Portland. Symbolically, riots occurred as parades connecting the administrative, commercial and industrial centres passed through Mill and Dock streets. Some Irish Catholics protested the Orange Order’s use of this route. Symbolically, such parades asked whether Irish Catholics had a place in the civic pageant. The Orange Order won a decisive victory in the York Point battle; hence, Irish Catholics had no part in the civic pageant either as marchers or by providing a site for celebration on the route of march. Even after the 1849 moratorium on Orange parades, Orangemen continued to parade, but wearing fire company or Mechanics’ Institute badges. Mechanics won a similar victory in their riot at Hopley’s Theatre. Following this riot, theatrical performances were confined to associational halls. As a result of these riots, Orangemen, firemen and mechanics dominated the "theatre of the crowd". Other groups, even circus performers, assembled under the threat of violence and intimidation.

57 The making of a separate ghetto for Irish Catholics was not the primary spatial component of the city’s social violence. The big riots of 1847 and 1849 were not about defending a distinct and segregated "Little Ireland" from the vigilante tactics of nativists. Indeed, it proved impossible to establish such a ghetto. New construction concentrated in the north end, but it was slow and disrupted by fires. The famine migration swamped the city’s housing stock, and Irish Catholics appeared in large numbers in every ward and parish. In this situation, the tenements and boarding houses in York Point and the Portland wharf district developed as high-density concentrations for the city’s poor and for seasonally mobile male workers, but they could not serve as segregated ethnic neighbourhoods. Neither York Point nor the Portland wharf district had clearly definable boundaries or homogeneous Irish Catholic populations. These were complex localities rather than ghettoes. The tenements nestled amongst wharves, saw mills, factories, warehouses, retail shops and private houses. These districts lay in between the city’s commercial heart and its emerging industrial economy and astride a key thoroughfare linking the city wharves and the countryside. Failure to establish segregation in the north end resulted in the overlapping of social groups in space, and this politicized the lack of work and relief in an economy characterized by seasonal layoffs, transience and an over-supply of labour. Recent immigrants fared poorly. Gatekeepers controlling job opportunities and municipal licences used group identities to structure access to jobs and relief. Even so, many Irish Catholics did get work and housing. One group of Irish Catholics (itinerant male workers, recently arrived from the west and south coasts of Ireland) used York Point as a base for attacks on individuals and property in the north end. However, such conflicts were dominated by mechanics, firemen, Orangemen and other Protestant crowds. Indeed, while in the 1840s the Orange-Catholic divide figured prominently in clashes over civic symbolic space, in elections and in assaults and other riots, north-end residents wearing different badges clashed over other matters throughout the 1840s and 1850s.

58 In Saint John’s hierarchical preindustrial society, groups attempted to gain control over resources and resisted new institutions such as fire companies, police, boards of health and the Orange Order, whose activities residents perceived in the contexts of local patronage networks.107 Tensions developed over free trade, temperance, elections, the board of health and the fire companies. Social violence spilled over into the "quiet" 1850s but remained concentrated in the city’s north end. And Saint John’s social violence was not consistently sectarian. When rioting occurred in York Point, it was not Saint John’s Irish Catholics who rioted, nor the city’s Protestants, but some Irish Catholics and some Protestants. Incidents were not confined to York Point and the Portland wharf district but scattered throughout the north end, and into the surrounding countryside. Irish Catholics demonstrated outside key seats of Orange Order activities such as Squire Manks’s house and Nethery’s Hibernian Hotel. Assaults targeted partisan wayfarers in Portland, King’s ward and Carleton. Acts of social violence occurred at specific sites over a broad area within the north end. It is impossible to tell whether some of these were struggles over access to labouring jobs, carting or liquor trade licences, but these were certainly local conflicts, with hints of economic subtexts to the incidents. Some of the badges came from across the Atlantic, but residents made their own trouble in the north end.