Is Atlantic Canadian History Possible?

James K. HillerMemorial University of Newfoundland

1 ALMOST 40 YEARS AGO, and almost to the month, a bewildered earlier version of myself clambered off a bush plane onto the ice which covered the harbour at Nain, Labrador. For a child of the London suburbs, just out of high school, the encounter was something of a shock. But I stayed in Nain for almost a year and a half, and it proved to be the experience that has made all the difference. It was, though I could not have guessed it then, the beginning of a lifetime’s connection with Atlantic Canada — which by my definition means four provinces, and Labrador.1

2 My time at the Moravian mission in Nain was supposed to be a constructive interlude between high school and university. But three years later I was back. I had a B.A. by that time, and my family hoped and expected that I would soon obtain "a proper job". But I negotiated another interlude, enrolled in the M.A. programme at Memorial University and took the coastal boat back to Nain. The result was an M.A. thesis on the history of northern Labrador, the discovery of academic life and a decision to postpone that "proper job". It was, in fact, postponed sine die, since Memorial’s History Department encouraged me to complete a Ph.D. and come back as a member. The thesis was originally intended to be about Labrador once again, but it turned into a conventional study of late-19th-century Newfoundland.

3 This fitted in well with Memorial’s agenda at that time. It was, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, an expanding, youthful place, which placed great emphasis on studying the province. The History Department actively encouraged research in Newfoundland and Labrador history — and, improbably, the history of India — and went out of its way to recruit faculty and graduate students who might contribute to this end. Similarly, the social science departments were promoting locally-focused research, and Folklore was beginning to separate from the English Department. It was a stimulating atmosphere, and there was a sense that we were rebuilding Newfoundland history. The "we" at Memorial included, among others, Keith Matthews, David Alexander and Ian McDonald, and later Shannon Ryan, Bill Reeves, Rosemary Ommer and Melvin Baker. Peter Neary, at the University of Western Ontario, has made his significant contribution from afar.

4 In fairness, the modern academic writing of Newfoundland history had begun earlier, with a sequence of theses at London and Oxford universities supervised by A.P. Newton and Gerald Graham — dated now, but some still useful — which created a chronological framework up to 1832, the year that the colony received representative government, and beyond. The vantage point was that of imperial history. Among the last of them was Gertrude Gunn’s study of Newfoundland politics between 1832 and 1864, published in 1966.2 Not surprisingly, perhaps, Gunn seemed not to know that since the late 1950s the relatively new History Department at Memorial, under the guidance of Gordon Rothney and then Leslie Harris, had been proceeding with its own sequence of M.A. theses, which in time covered the political story up to the early 1870s, with others on the railway, the Orange Order, the Fishermen’s Protective Union and so on. The last batch of the English-based Ph.D.s were completed in the early 1970s by myself, Matthews, McDonald and S.J.R. Noel, by which time the ground had been more or less covered up to the 1950s.

5 It was a broad brush approach, and the bulk of this work was political, diplomatic and constitutional. But Matthews, Alexander, Ryan and others began to inject a strong dose of economic history, while historical geographers — for example, John Mannion, Alan Macpherson, Gordon Handcock, Grant Head, Patricia Thornton, Rosemary Ommer — began to look closely at migration and settlement. Social history per se was comparatively late in its arrival, but arrive it did in the 1980s, with important work soon being produced on labour and women’s history, and on informal and household economies. In all of this, it should be noted, Labrador has not (on the whole) received the same degree of attention as the Island and, as Olaf Janzen has remarked,3 it is an anglo-centric historiography which tends to neglect the important impact of the French. Yet another point to be noted is the influence of social scientists, particularly in the late 1970s, who had their own historical agendas to pursue.4

6 There was, initially, very little reference to the Maritime Provinces. This was the construction of a national history for Newfoundland, and the frame of reference was North Atlantic rather than North American, with a strong Nordic flavour, for there was considerable interest in some quarters in the experience of Norway and Iceland as fishing countries. What preoccupied students of Newfoundland history then — and still does to some extent — was why the colony’s economic development had been comparatively slow, backward and unsatisfactory. Why had Newfoundlanders failed to create a prosperous, diversified economy? What had gone wrong? And following from this, why had the experiment of independence failed? What had caused the humiliation of 1933-34? And Alexander began to ask what had gone wrong after Confederation in 1949, which led him on to broader questions about the nature of the Canadian state.5

7 Though Alexander was interested in the Nordic comparisons, it was he who initiated a swing to the west in Newfoundland historiography. Perhaps because he was, at that time, the only mainlander among those of us interested in the province’s history, Alexander began to look at Newfoundland in an Atlantic Canadian context, and he went on to write a series of important articles on the economic development of the region and its place within Confederation.6 At the same time, this reorientation towards the mainland was encouraged by the Atlantic Canada Shipping Project (ACSP) which began in 1976. Based at Memorial, the project attempted, with some success, to construct an historical framework relating to the regional economy in a finite period. The project encompassed all four provinces, and tackled questions of fundamental importance. Meanwhile, at the University of New Brunswick, the foundation of Acadiensis and the inauguration of the allied Atlantic Canada Studies conferences encouraged the development of a genuinely regional historiography.

8 These promising, integrative initiatives have not had the results which one might have expected. There has been no successor to the Atlantic Canada Shipping Project, and the promise of the 1970s, that a school of Atlantic regional history might emerge, has not been fulfilled. Was this a false hope? Or, if such a history could have emerged, why has it not done so? Before attempting an answer, let me give a few indicators of what I am talking about. Acadiensis is the leading journal for the history of Atlantic Canada. Over the period from 1971 to 1999, 16 articles out of a total of 255, 6.25 per cent, can be said to deal with the whole region, and that is stretching things a little. Forty-six articles, 16.1 per cent, deal with two or more Maritime Provinces. Seventy-three per cent of articles, 186, deal with a single province.

Table 1: Acadiensis Articles, 1971-1999

Display large image of Table 1

9 In the same journal, the periodic bibliography has an "Atlantic Canada" category, which includes any publication dealing with more than a single province. I did a rough and ready analysis to isolate works dealing with the region as a whole, excluding theses, bibliographical works, Dictionary of Canadian Biography articles, shipwrecks and "popular" history. The bibliographies started in 1975 and run to 1999. The analysis found seven books, 16 articles, and 26 essay collections. Of the collections, five were published by the Atlantic Canada Shipping Project, four by Acadiensis.

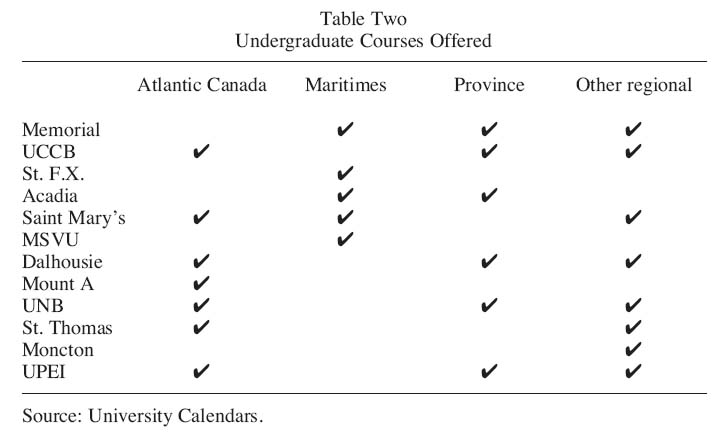

10 University calendars were the next source examined. This was also tricky, since the relationship between what a calendar may say, and what actually happens in a classroom, can be somewhat tenuous. Of the 12 institutions surveyed, seven offer undergraduate courses on "The Atlantic Provinces". Of the five which do not, four offer courses on the history of the Maritimes. L’Université de Moncton concentrates on Acadian history.

Table Two: Undergraduate Courses Offered

Display large image of Table 2

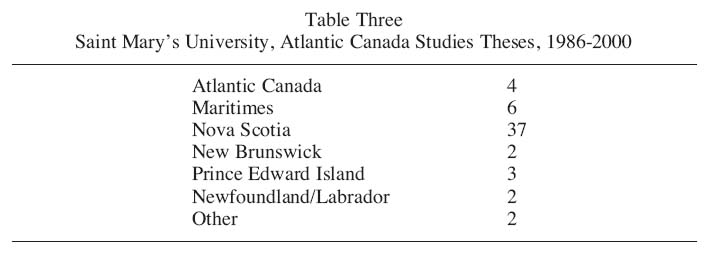

11 At the graduate level, Atlantic Canada seminars are available only at Saint Mary’s and the University of New Brunswick, but it is clear that graduate research into many aspects of the region’s history is thriving, subsumed into Canadian history programmes. Only at Saint Mary’s is there an Atlantic Canada Studies graduate programme as such. Again, I made a quick analysis of the 56 theses completed there between 1986 and 2000. Of these, 37 were on Nova Scotian topics, or 66 per cent. So far as I could tell from titles alone, only four (seven per cent) dealt with Atlantic Canadian subjects.

Table Three: Saint Mary’s University, Atlantic Canada Studies Theses, 1986-2000

Display large image of Table 3

12 On the basis of this evidence, unsatisfactory as it is, it seems that while we teach a fair amount of Atlantic regional history, certainly at the undergraduate level, very few of us write it. We write about our own provinces for the most part, with some attention sometimes to what was going on in other parts of the region. We have a lively but localized historiography. Very few attempts have been made at regional syntheses,7and there is a strong sense that while the Maritimes may indeed constitute an historical region, Newfoundland and Labrador do not "fit"; that it is a very different place, in a sense a foreign country (or countries). Indeed, the phrase "Atlantic Canada" is not infrequently used to mean the Maritimes, and historians of Canada, and even the region,8 have tended to assume that Newfoundland and Labrador, because politically divergent, can be safely sidelined, or even ignored between 1867 and 1949. Some historians of Newfoundland and Labrador have agreed, and do agree with the separation, emphasizing the distinctiveness of their province’s experience and its North Atlantic orientation; but others believe that the province’s history can and should be placed within a Canadian or North American regional context.

13 Perhaps we need to remember that "Atlantic Canada" is an expression only 50 years old in its four-province manifestation, and that a sense of the larger region takes longer than that to emerge. Living in the Maritimes, it is very easy to forget that Newfoundland and Labrador exist. St. John’s is not habitually on the way to anywhere unless you find yourself on a flight to London that stops there. And to go there, or anywhere else in that province, demands special reasons, an invitation, a special effort. Memorial University often falls off the academic radar screen.9 Maritimers look west, not east, to the known rather than the unknown. With the completion of the Confederation Bridge, now they are mainlanders all. To someone living in Newfoundland, by contrast, the Maritimes are a daily reality. We too look west, but our nearest, best west is Halifax, Atlantic Canada’s metropolis, to which we are firmly and inevitably linked in many ways. We cannot forget or ignore the rest of Atlantic Canada, and we probably know more about the Maritimes than Maritimers know about us.

14 It has to be accepted as well that there are significant differences between the histories of Newfoundland and the Maritimes, and that historians on either side of the Cabot Strait have been preoccupied with questions particular to their areas. In the Maritimes, major discussions have revolved around the economic shifts of the 19th century, and the de-industrialization that followed in the 20th. Newfoundland historians have been preoccupied with understanding the anomalies in Newfoundland history and the transition to provincial status. As a result, the larger region has not been especially important to most regional historians.

15 These considerations aside, and they are not unimportant, we should also remember that historians do not frequently adopt comparative methodologies,10 and that recent deployments in the discipline have perhaps encouraged a retreat from the broad approach and, indeed, from the region, or the province, as a unit of study. There is very little political, constitutional or diplomatic history written any more, and research tends to be closely focused. This may be in some aspects a positive development. In Newfoundland, certainly, the broad generalizations of an earlier generation of scholars are coming under criticism and re-evaluation from current and recent graduate students, who are making detailed re-examinations of some crucial areas of Newfoundland history and opening new ones.11 The field is widening and becoming richer. But while I sense in Newfoundland a feeling that these studies must ultimately feed into and inform discussion of broader "national" questions, I do not have the same impression of historical activity in the Maritimes.12 I may well be ill-informed, or have formed the wrong impression, but I do wonder about the future of regional history in the Maritimes, and therefore about the future of Atlantic Canadian history as a whole. Are we ever going to have a genuine, grand synthesis of the history of all four provinces, or are we to remain content with essay collections?

16 Others before me have argued that such a synthesis is possible, and that the histories of all four provinces can be integrated into a common framework.13 They were all British colonies, with similar economies, similar cultures, similar population mixes and a common identity as members of the British Empire. There were many links between them, formal and informal, personal and institutional. That Newfoundland chose a different political path does not override its essential family relationship with the Maritime Provinces. The problem is not in fact the integration of Newfoundland, but (ironically from my point of view) the integration of central and northern Labrador, which really form part of the Canadian North, with a history that is indeed very distinct from that of the rest of the Atlantic Region. I also believe that a synthesis is needed, not only for our own purposes, but also so that our colleagues and their students elsewhere in Canada can inform themselves conveniently and accurately about this region’s history. Otherwise I fear that our history may not receive the attention which it deserves, and that unfortunate myths, half-truths and stereotypes will be perpetuated. Most university-level Canadian history textbooks have now recognized the existence of Atlantic Canada, some more satisfactorily and accurately than others, but high school texts seem to remain tiresomely formulaic; and in any event, many high school students graduate without a Canadian history course. Our history needs to be made more accessible.

17 For all the activity of the past 30 years, there are many areas of the Atlantic Canadian past which still need examination, the history of the fisheries in the Maritimes and of religion throughout the region being prime examples. And — dare I say it? — it is time to revive political history. To fill the gaps, we need to develop successors to the Atlantic Canada Shipping Project — collaborative, comparative projects involving scholars in all four provinces, coordinated by such institutions as the Gorsebrook Institute and Memorial’s Institute for Social and Economic Research. From such initiatives might come, eventually, a solid and reliable regional historical synthesis. But even to say this betrays me as an old fogey. Post-modern critiques have eroded historians’ confidence in what they do, and social history has introduced different categories of analysis. I may think that an Atlantic Canadian history is possible, desirable and needed, and that once begun it needs to be completed. I may think that efforts should be made to knit togther the mental worlds of the Maritime Provinces and Newfoundland and Labrador. But does anyone out there agree? Is anyone interested any more?

18 I doubt that people in Nain are much concerned with all of this, preoccupied as they are with the social dislocation that dominates the news reports. But Nain has a remarkably interesting history which links together Europe, the North and Atlantic Canada. "Only connect", said the novelist E.M. Forster. Genuinely regional historians should take note.

JAMES K. HILLER

Notes