Rooted in the Soil:

Farm Family Persistence in Burton Parish, Sunbury County, New Brunswick, 1851-1901

Timothy D. LewisUniversity of New Brunswick

1 AT THE MIDDLE OF THE 19TH CENTURY, 35-year-old John Payne worked as a ship carpenter in Burton Parish, Sunbury County, New Brunswick. At home, 28-year-old Anne, who like her husband was an Irish Protestant immigrant, cared for the couple’s three young children: Mary 7, William 5 and Anne 2. A decade later there were seven Payne children in all. However, the local shipyards that gave employment to men such as John Payne had not fared so well, a situation which forced large numbers of men to leave the parish. But John Payne stayed, found work as a sawyer, and he continued to support a large family. All were still at home in 1871 (except the eldest daughter Mary), and the oldest son William’s earnings as a carpenter must have helped augment the family’s income. By 1881, however, John was dead and only Anne, John Jr. and daughter Ellen remained in Burton. Ten years later, only the widowed Anne remained to remind long-time neighbours of the once full and active Payne household.1

2 In a number of ways, the experiences of the Payne family encapsulate much of what scholars have learned to date regarding the demographic history of the Maritime Provinces in the second half of the 19th century. Rural depopulation was a concern throughout much of North America and Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.2 But, as the dispersal of the Payne family suggests, the Maritime region was particularly hard hit, losing several hundred thousand residents from a population of less than one million.3 First apparent in long-settled rural areas such as Burton Parish whose economies relied heavily on agriculture or shipbuilding, out-migration became a common feature of late 19th-century Maritime life.4 Of particular concern, the majority of migrants, like the Payne children, were young men and young women.5

3 Given the magnitude of the exodus from the Maritimes, it is not surprising that historians of the eastern provinces have focused considerable attention on the way in which out-migration affected Maritime development. From this work, we have acquired a better idea of the number of individuals who left the region in the late 19th century, learned much about the economic factors that contributed to the migration and identified the destinations of many of the migrants.6 Yet repeated emphasis on the regional migration has, as Phyllis Wagg recently noted, unwittingly obscured the experiences of those who did not participate in the emigration.7 Drawing on evidence from a study of the geographic persistence and mobility of the population of Burton Parish between 1851 and 1901, this study identifies some of the characteristics that typified those who remained the area’s long-term residents.8 Although this parish experienced a significant population loss, local households continued to exhibit considerable geographic stability. For at the same time Burton was experiencing unprecedented levels of out-migration, the geographic stability rates of parish families remained as high as, or higher than, those recorded elsewhere in North America during this period. By the dawn of the 20th century, individuals from the parish’s most geographically stable families comprised an even larger proportion of Burton’s population, a situation produced by a combination of family strategies, limited in-migration and selective out-migration from the parish. Far from creating social instability, the experience of Burton Parish suggests that the late 19th-century migration from the Maritimes left the region with an increasingly stable population.

4 The core of this enduring population in Burton, as elsewhere in rural North America, were farm owners and their families.9 Ownership of farm land, of course, substantially improved the likelihood of a family maintaining its presence in a rural community such as Burton. It is a reminder of the extent to which farm families formed the economic, social and political backbone of the late 19th-century Maritimes. In according much of their attention to the end of the age of sail and/or the Maritimes’ industrial development, scholars have tended to overlook the fact that the region remained overwhelmingly rural. This work, then, aims to take up Daniel Samson’s recent challenge to put the "countryside and its people . . . at the centre of any history of economics and society in Atlantic Canada".10

5 Before the 1870s, Burton Parish and its surrounding environs was a place migrants flocked to rather than fled from. Located in the fertile valley of the navigable St. John River, where it joins the Oromocto River, Sunbury is the smallest county in New Brunswick. Long occupied by members of both the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet First Nations, Burton’s first permanent non-Native settlers arrived from Massachusetts in the 1760s. Shortly after, in the wake of the American Revolution, much of the parish was set aside for incoming Loyalists, and, by the mid-1800s, the area was also home to large numbers of Catholic and Protestant Irish immigrants.11 Attracted by the fertile land and thick forests found along the banks of the parish’s two main rivers, settlers relied heavily on agriculture, lumbering and shipbuilding for their livelihood. It is not surprising that the ups and downs of the parish’s primary industries proved pivotal in determining which of Burton’s families would remain in the parish over the long term.

6 For several decades, shipbuilding was the most vibrant sector of the local economy. Despite its inland location, the parish possessed a number of natural advantages for the building of wooden ships. Both the Oromocto and St. John were rivers sufficiently broad and deep to make them accessible to ships of a considerable size. The forests contained large stands of tamarack, a wood ship carpenters prized for its durability, and as a result local timber was used for ship construction as early as the 18th century. In the middle decades of the 19th century, builders in the villages of Oromocto and Burton produced at least 45 vessels of various sizes and descriptions.12 Shipbuilding’s contribution to the local economy is evident from the Industrial Schedule of the 1871 census. In that year, the 28 shipyard employees in Burton earned a total of $9,500, while the other 26 industrial workers in the parish combined to earn only $1,950.13 Moreover, these figures come from a time when the area’s shipbuilding industry was already showing signs of decline. Vessel construction in Burton ceased altogether in the mid-1850s when the capital normally provided by Saint John-based merchants was diverted to the United States following the ratificative of the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854.14 The local shipyards sprang to life again later in the decade, but given that the number of ship carpenters in the parish fell from 61 to 8 between 1851 and 1861, they obviously operated on a much smaller scale. By 1876 the local era of wood, wind and sail was more or less over.15

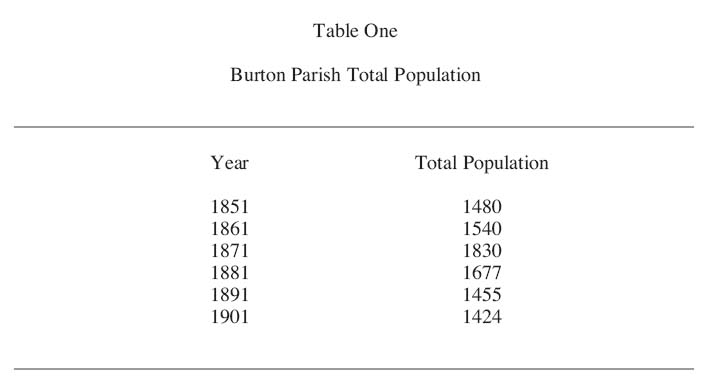

Table One : Burton Parish Total Population

Display large image of Table 1

7 The demise of local shipbuilding contributed to a dramatic drop in Burton’s population from 1,830 people in 1871 to 1,455 in 1891 (see Table One). Indeed, several families, such as those headed by ship carpenters Thomas Hicks and William Scoullar, left the area even earlier. These men had been very active in local shipbuilding in the 1830s and 1840s, but neither they nor any member of their families were resident in Burton Parish by 1861.16 Other, less prominent, ship carpenters tried to keep their families in the area somewhat longer. For example, 59-year-old Joseph Hoyt turned to work as a labourer in the hopes of maintaining his 41-year-old wife Elizabeth and their seven children in the Burton home where, as of 1861, they had lived for more than ten years. Hoyt succeeded only temporarily. Most of the family was still resident in Burton a decade later, but by then the four remaining children were working to help support their now widowed mother (23-year-old George was a carpenter, while daughters Jane and Sarah were employed as servants, as was 12-year-old David).17 Apparently none of the Hoyt children were able to find suitable long-term employment in Burton, as they all eventually left the parish. Nor was this an isolated case. Rex Grady documents the migration of more than a dozen inter-related Burton Parish families who, in the late 1860s, set out for the North Lake district of Charlotte County along the New Brunswick-Maine border, where jobs were more numerous thanks to the expansion of a local tannery.18

8 Census figures suggest that the jobs lost in the decline of the shipbuilding economy were partially replaced by the growth of local logging and sawmilling operations, as between 1871 and 1881 the number of resident lumber or mill workers rose from 5 to 32.19 The late 19th century also saw many Burton residents relocate, either permanently or seasonally, to work at the Mitchell log boom in neighbouring Lincoln Parish.20 At its peak, the Mitchell boom employed as many as 180 men, and it was one of several such operations that swung into action each spring after the break-up of the winter’s ice in the St. John River. The boom’s function was to collect and sort logs cut along the river valley the previous fall and winter, many of which were American in either origin or destination. The Canadian and American governments had an agreement at this time whereby logs cut in the State of Maine and New Brunswick’s Upper St. John River Valley could be floated down-river, rafted and sorted at a boom and then towed to Saint John. Once in the Port City, the logs were either processed at a mill or shipped whole to the United States in order to avoid the American tariff on finished lumber products.21 Yet, despite the good number of former and continuing Burton residents who gained seasonal employment at the Mitchell boom, it was not until the winter of 1907-08, when the River Valley Lumber Company established a sawmill in the village of Oromocto, that the parish began to reap significant long-term employment benefits from the forest industry.

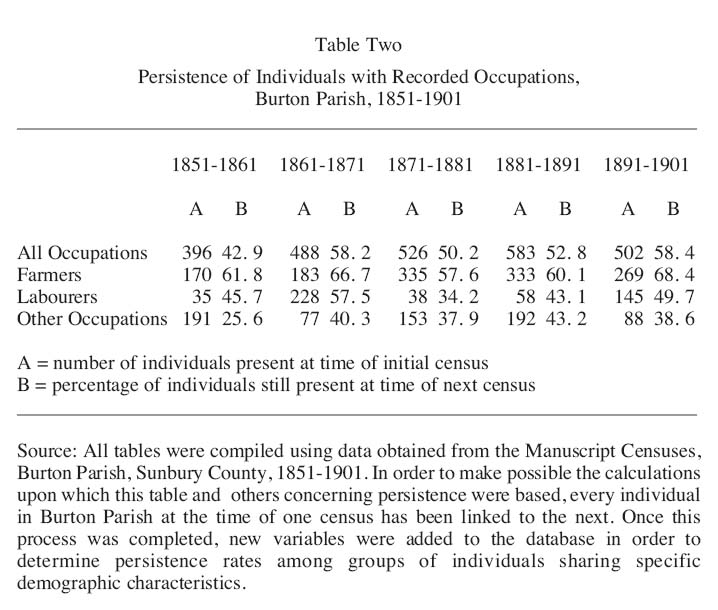

Table Two : Persistence of Individuals with Recorded Occupations, Burton Parish, 1851-1901

Display large image of Table 2

9 The one relatively stable sector of Burton’s economy in the second half of the 19th century was agriculture. Farmers formed the largest occupational group in the parish throughout the latter half of the 19th century, and following the collapse of local shipbuilding they accounted for considerably more than half of all the listed occupations in Burton (see Table Two). The vast majority of local farmers owned their own land (the 1871 census records 226 farm owners in the parish and only 14 farm tenants); there were, however, some dramatic differences in the scale of operation of area farms. Approximately ten per cent of Burton’s agricultural holdings consisted of less than 50 acres, while the parish’s largest farm was 40 times that size.22 Farm properties of between 100 and 200 acres were the norm, however.23

10 Whatever their holdings, most families operated mixed farms that produced a variety of grains, vegetables, livestock and dairy products.24 For the most part, these goods were consumed locally, but regular steamship service allowed farmers operating above the subsistence level access to markets in the cities of Saint John and Fredericton.25 Significant surpluses were apparently not the norm in Burton, as the agricultural data collected for the 1871 census suggests that only nine per cent of the parish’s farms operated on a large scale.26 As most of Burton’s best farm land had been occupied since the late 18th and early 19th centuries, late-comers who hoped to carve out an agricultural livelihood faced a difficult challenge. Though it perhaps offered more stability than other occupations, agriculture did little to stimulate significant demographic or economic growth in Burton Parish.27

11 In many ways Burton Parish was typical of the late 19th-century Maritimes. A long-settled rural area, economically reliant on shipbuilding and agriculture, it experienced a significant population decline and large-scale out-migration.28 But the story was much more complex. Personal data gathered on every individual listed in each of the decadal censuses of Burton Parish between 1851 and 1901 reveals that although large numbers of people did leave the area, the region’s inhabitants simultaneously exhibited high levels of geographic persistence equal to or surpassing those found in most other late 19th-century communities.29

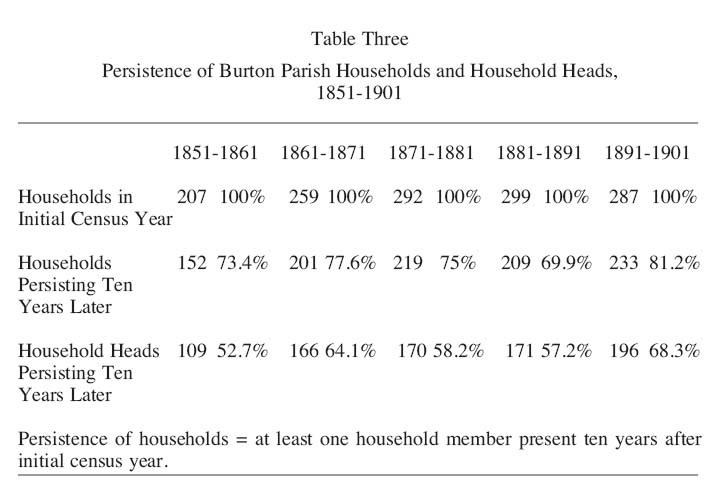

Table Three : Persistence of Burton Parish Households and Household Heads, 1851-1901

Display large image of Table 3

12 Persistence measures the number of families or individuals in a population or cohort (often expressed in percentages) who remain in a given geographical area within a specific time-frame.30 The standard means of establishing persistence rates has been to determine the number of household heads in an initial census year who remain resident in the same area at the time of the next census.31 This practice poses several problems, however. The implicit assumption underlying this method is that whole families relocated whenever the absence of a household head is recorded. This is misleading. Many heads of households, several of whom were elderly, may well have died in the ten-year interval between census years, while others may have regularly left home for extended periods to pursue employment opportunities – or they may simply have been missed by the census taker. At the same time, some or even most other members of the household might well remain in the census area for generations to come.

13 Therefore, although the persistence rates of Burton’s household heads are noted in Table Three, a more precise measure of the persistence of the area’s population is obtained by identifying the number of parish households in which at least one member remained to be counted from one census year to the next.32 Weaknesses exist with this approach as well – for a household is considered persistent even if only one member of what was once a large household remained in the parish – but specialists in the field of demographic history generally agree that results are more reliable when families or couples are linked from one census to the next rather than only individuals or household heads.33 Moreover, the vast majority of Burton’s persistent households had more than one member persisting between censuses.34 In fact, given the lack of available marriage records for Burton, and the resultant difficulty in tracking women once they married and changed their surnames, the number of long-term persistent households may well be underestimated in this study.

14 As it charts every listed inhabitant of Burton Parish for six consecutive censuses, this study also limits errors arising from omissions in individual censuses or from a sampling method, and this methodology also makes it easier to properly identify individuals whose names may have been incorrectly or illegibly transcribed by census takers. Nor is Burton Parish a large geographic region, a factor which reduces the inflated persistence figures inevitably produced whenever a study area is so large that individuals or families may move long distances and still be considered persistent.35 By restricting itself to the relatively small confines of Burton Parish, this study underestimates the actual number of individuals or families who remained in the general vicinity, since even those who moved only a few miles to one of the adjoining parishes of Sunbury, or who relocated just a little further to the neighbouring counties of Queens or York, are classified as migrants.36 Nonetheless, this limited geographic scope, combined with the 50-year period of analysis, allows for a reasonably accurate look at the number and nature of families who persisted in one small section of the late 19th-century Maritime countryside.

15 Although the population of Burton Parish fell steadily throughout the latter half of the 19th century, the area’s families maintained an impressive level of geographic stability. On average, three out of every four households enumerated each census year between 1851 and 1901 were represented by at least one member in the subsequent census (see Table Three). Persistence figures for heads of households in Burton ranged from 52.7 to 68.3 per cent. Compared with rates from studies published in the 1960s and 1970s which found that the persistence rates of household heads in many late 19th-century North American centres were between 25 and 45 per cent, the Burton rates are high.37 Most of these works focused on either rapidly expanding cities or emerging frontier regions – areas prone to large-scale population turnover – so it is somewhat misleading to compare their findings to those from a long-settled rural region such as Burton Parish.38 The level of geographic stability maintained by Burton households during the second half of the 19th century is comparable to that found in more recent studies of family persistence, which examine other long-settled rural areas in northeastern North America. Although hundreds of thousands of migrants left that section of the continent in the late 19th century, many communities retained a large and stable population base.39

16 How could Burton’s population maintain or even increase its rate of persistence at the same time it was experiencing unprecedented levels of out-migration? One explanation for this phenomenon lies in the area of family limitation. Whether it was a deliberate response to the trying economic conditions the region experienced is difficult to ascertain, but census data suggests that persistence levels in Burton Parish were maintained, at least in part, due to a falling birth rate. For example, in 1851 57.7 per cent of mothers in Burton Parish between the ages of 30 and 45 had five or more children living under their roof. By 1901, however, only 34.3 per cent of mothers in this age category reported a similar number of children in their households. Moreover, the average size of farm households in Burton fell from 7.2 members in 1851 to 4.9 members in 1901.40 This smaller family size presumably would have placed less strain on the parish’s limited economic resources, thereby reducing population pressure, and, in turn, limiting out-migration and boosting persistence levels.41

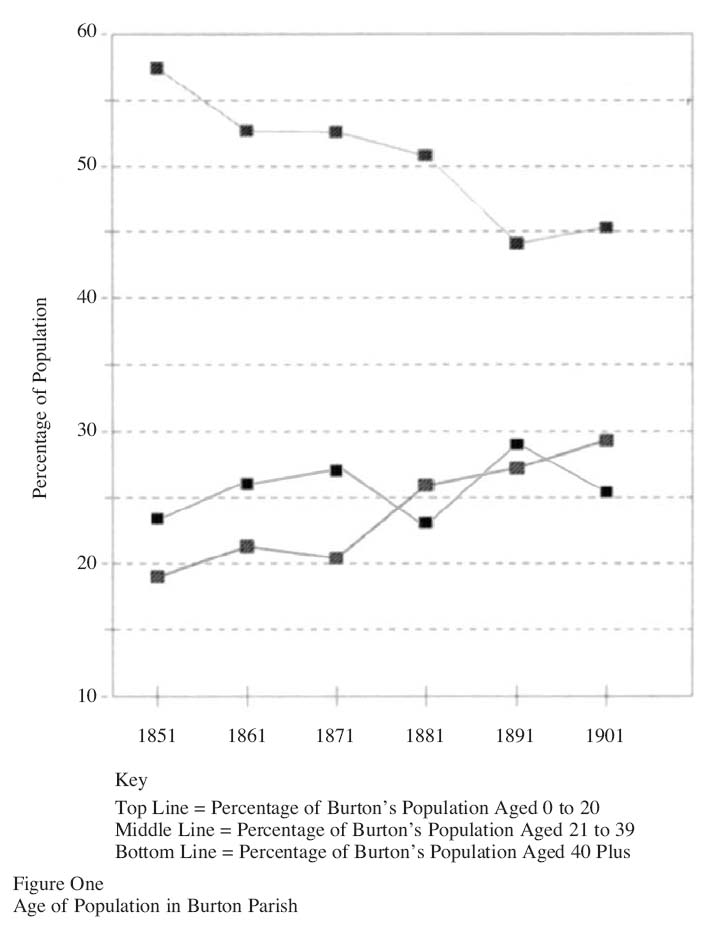

17 But perhaps the best explanation of how a region such as Burton could experience both large-scale out-migration and significant levels of persistence is provided by Hal Barron’s study of 19th-century Chelsea, Vermont. Chelsea, like Burton, was a long-settled rural community which experienced considerable out-migration following an extended economic downturn, but here too Barron found significant levels of household persistence. This situation was a product of the selective nature of out-migration from Chelsea over time. For example, Barron found that young people left the Vermont community in large numbers, a factor which left the remaining population not only older but more sedentary.42 The same pattern emerged in Burton. Young people left the area in large numbers. Other than the most elderly, those aged 10 to 25 were consistently the least persistent members of Burton’s population.43 Accordingly, the late 19th century witnessed a significant ageing of Burton’s population (see Figure One). Moreover, as in Chelsea, the older Burton’s populace became, the more geographic stability it exhibited. The highest overall persistence rate recorded in the parish during the second half of the 19th century coincided with the period – 1891 to 1901 – when the proportion of Burton’s population over the age of 40 was at an all-time high (see Table Three and Figure One).

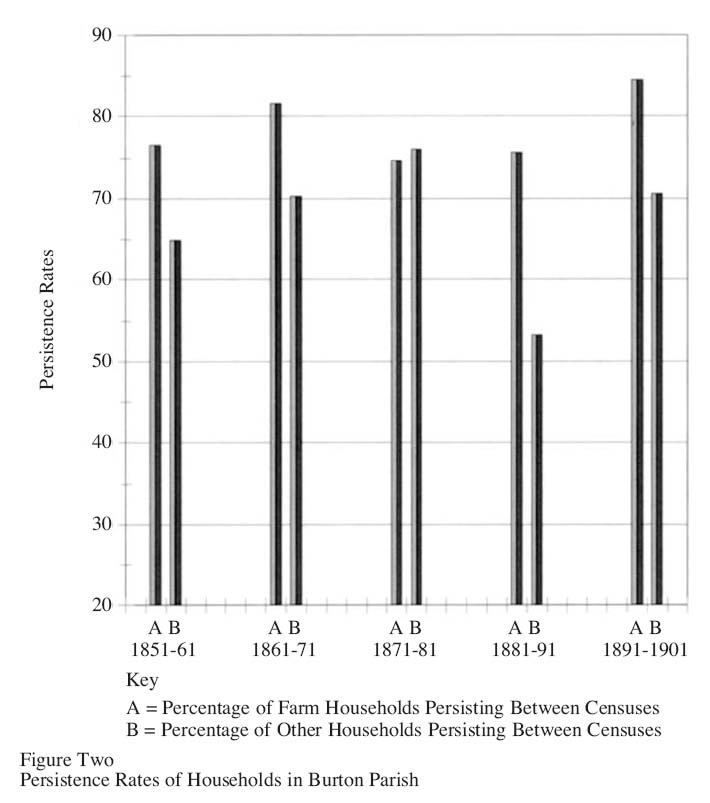

18 Barron found that those who had an economic stake in the Chelsea area were much more likely to remain in the community over the long term. In particular, farm owners formed a significant part of the township’s substantial persistent population.44 The same was true in Burton Parish. The primary factor which allowed large numbers of area families, even those as apparently divergent as the pre-Loyalist, New England Protestant descendants of Richard Kimball45 and the Irish-Catholic immigrant progeny of Thomas McCafferty,46 to remain in Burton decade after decade was their ownership of farmland. Farmers made up the largest occupational grouping in Burton Parish, and were consistently more persistent than the members of other occupations (see Table Two).47 The occupational figures from the 1891 census reveal that although 25 fewer people lived in the parish than in 1851 (Table One), there were almost 100 more farmers than had been the case 40 years earlier (see Table Two).48 It should come as no surprise, then, that farm families made up the majority of the parish’s long-term residents and were considerably more likely to be persistent than their non-farm counterparts (see Figure Two). A strong correlation existed between the ownership of farmland and household persistence. Other factors, such as religion and place of birth, appear to have had comparatively little impact on whether or not a family or individual remained in Burton Parish over the long term.49

Figure One : Age of Population in Burton Parish

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

19 That land ownership was a key factor in promoting persistence is clearly illustrated by the census figures from 1851 and 1861 which divide farmers into proprietor and tenant categories. In that decade, persistence levels for farm owners were twice as high as those for all other occupational groups combined: 65.6 per cent vs. 32.8 per cent.50 The connection between ownership of farm land and household persistence was even more evident between 1871 and 1881: 77 per cent of farm families who owned property in 1871 were still in Burton in 1881. Moreover, families who owned large amounts of farm land were particularly apt to be persistent. Fully 85.7 per cent of those who owned 200 or more acres of farm property in 1871 were still in the parish ten years later. On the other hand, those who owned less than 50 acres of agricultural land, although they fared much better than non-farmers, persisted at a rate of only 62.5 per cent, and even fewer – 57 per cent – of the parish’s 1871 farm tenant families maintained a presence in Burton in 1881.51 Farm families who possessed fewer economic resources were significantly more likely to join the regional out-migration than were those who held more extensive holdings in Burton.52

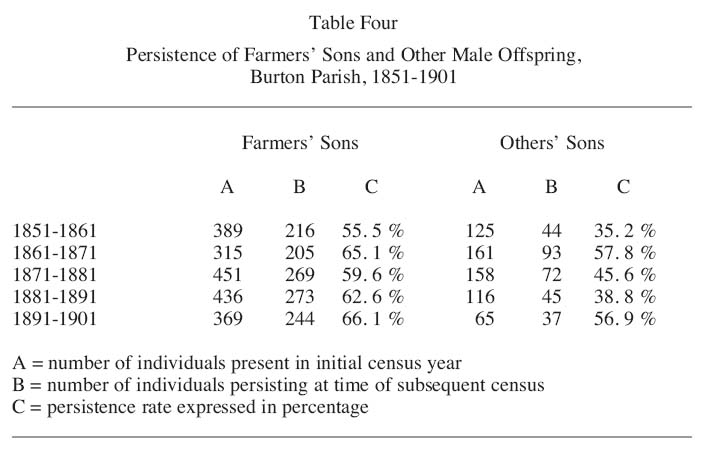

Table Four : Persistence of Farmers’ Sons and Other Male Offspring, Burton Parish, 1851-1901

Display large image of Table 4

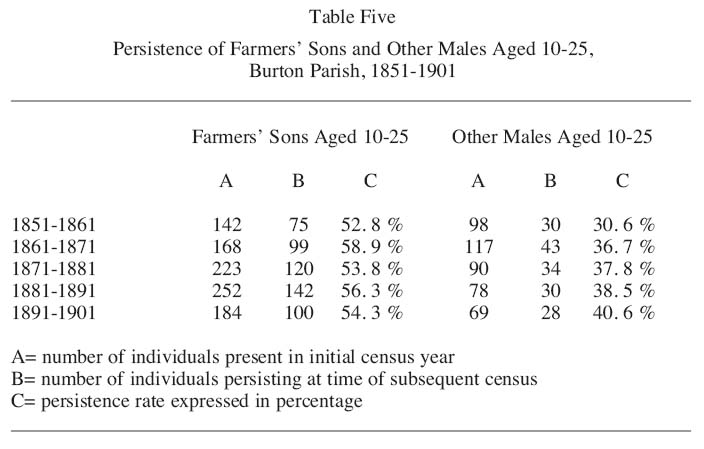

20 Although it was hardly a guarantee of prosperity, farm ownership significantly increased the likelihood of a family’s children remaining in Burton Parish. Between 1851 and 1901 farmers’ sons were much more likely to remain in Burton than were their non-farm counterparts (see Table Four). Particularly striking are the persistence rates for those aged 10 to 25, the least persistent segment of Burton’s population in the latter half of the 19th century (see Table Five). Although the low rates in this age category stem, at least in part, from the difficulty of tracking young women who married between census years and took their husband’s name, it also suggests the extent to which Burton’s male youth were utilizing out-migration as a strategy for combating the limited economic opportunities available in the parish.53 The average persistence rate for all those aged 10 to 25 between 1851 and 1901 was 40.7 per cent and only 36.8 per cent for sons of non-farmers (see Table Five). In contrast, farmers’ sons in this age bracket persisted at an average rate of 55.2 per cent. Clearly, farmers’ sons were significantly more likely to be able to make a permanent home for themselves in Burton than were their non-farming friends and neighbours, although the gap in persistence rates between the two groups was apparently narrowing by the end of the century.

Table Five : Persistence of Farmers’ Sons and Other Males Aged 10-25, Burton Parish, 1851-1901

Display large image of Table 5

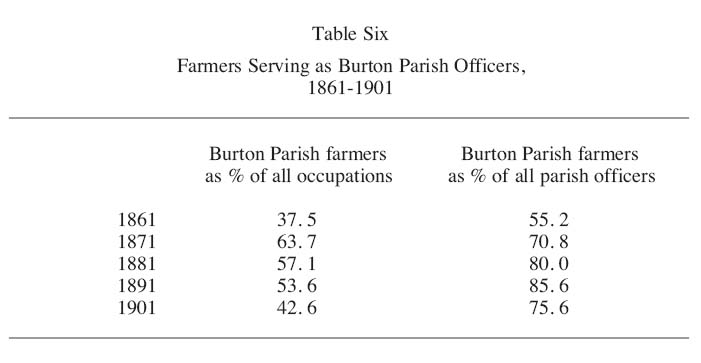

21 The numerical dominance of farm families in Burton Parish was apparent in the evidence of local participation in the structures of political authority. Municipal-level politics in rural New Brunswick allowed significant numbers of residents an opportunity to assume positions of responsibility, either as elected county councillors or, more commonly, as appointed parish officers.54 Close to 20 per cent of Burton’s white adult male population served in one or the other of these capacities each year over the last four decades of the 19th century.55 In terms of religious preferences, Burton’s parish officers and county councillors were representative of the region’s population,56 but in the area of occupation an obvious bias existed. Farmers were consistently over-represented when it came to the appointment of parish officers (see Table Six). In part, this can be explained by the fact that almost 70 per cent of the elected councillors, who made the parish appointments, were farmers themselves;57 presumably, it also reflects the fact that many of Burton’s farmers headed longstanding parish families and thus were more likely to have acquired the knowledge of local affairs required to fulfil such duties. Although they could not vote or hold office, some farm women also played an active role in the political affairs of Burton Parish. Many signed their names to legislative petitions and/or were keen supporters of the temperance movement.58

Table Six : Farmers Serving as Burton Parish Officers, 1861-1901

Display large image of Table 6

22 In contrast to the political dominance of farm families, labourers, despite their significant numbers, rarely received appointments to parish offices. In 1901, for example, labourers accounted for 29.1 per cent of all listed occupations in Burton Parish, yet only four of these 137 individuals served as parish officers. Most labourers owned little if any land, and thus they were unlikely to be considered for positions of leadership in a society dominated by those who owned property. Clearly, the persistent farm families of Burton Parish dominated local offices and were thus in the best position to shape the conduct of community affairs.59

23 As contradictory as it may at first appear, late 19th-century Burton Parish experienced both significant levels of out-migration and, thanks to the impressive level of geographic stability exhibited by the region’s farm families, a heightened level of persistence. Although a great many families left Burton, others became increasingly prominent. For instance, in 1851 there were only seven members of the Kimball family living in Burton Parish: the widowed Isabella, daughters Elizabeth and Martha and sons John, Samuel, Richard and James. Richard left the parish before 1871, but each of his three brothers and at least some of their children remained. Accordingly, by 1901 there were 21 Kimballs in the parish, each of whom was descended from the original family of seven.60 While such long-resident families were experiencing growth, the parish’s economic difficulties had forced other families to relocate and kept most newcomers away.

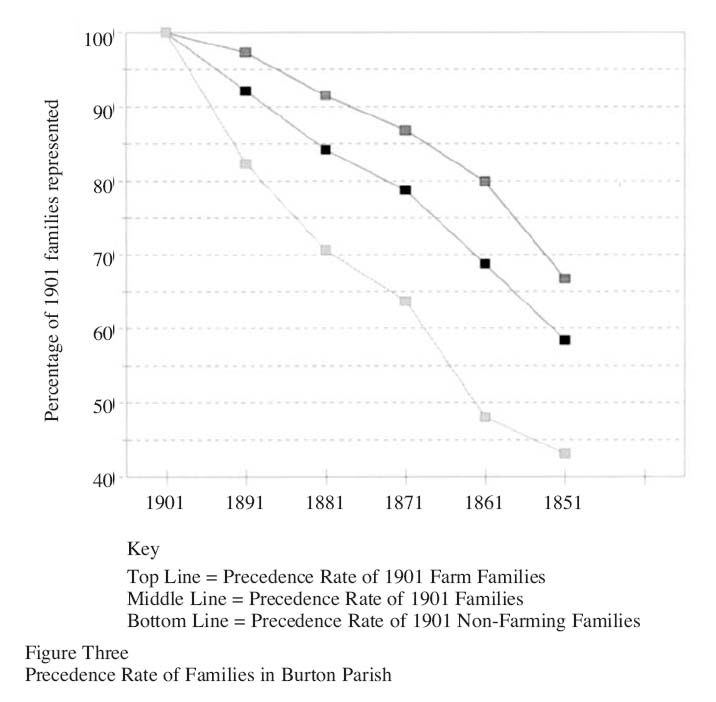

24 The increasing predominance of long-standing families in Burton Parish is evident when one examines the level of precedence (the length of time an individual or cohort has been resident in a given location) exhibited by households listed in the 1901 census.61 Using this measure, one finds that almost 60 per cent of Burton’s 1901 households included at least one member who either had lived in the parish for 50 years or more or was descended from such individuals. Moreover, almost 80 per cent of Burton’s 1901 households had at least a 30-year history in the parish (see Figure Three). Once again, it was Burton’s farm families who were primarily responsible for this phenomenon. Eighty per cent of Burton’s 1901 farm families had roots in the parish that extended back at least 40 years, whereas only 48 per cent of Burton’s non-farm families could make a similar claim.

25 Just how long Burton’s population continued to exhibit this level of geographic stability is uncertain, but there is some evidence to suggest that it may have continued for several more decades. In their analysis of New Brunswick residents who migrated to the United States between 1906 and 1930, Yves Otis and Bruno Ramirez found only three individuals from all of Sunbury County in their extensive database.62 However, a cautionary note must be appended to these figures, as they exclude the perhaps good number of Sunbury residents who may first have moved elsewhere in the province before either they or their descendants relocated to the United States.63 It is also important to note that geographic stability should in no way be equated with prosperity. For a good many residents of communities such as Burton, New Brunswick and Chelsea, Vermont, persistence may well have been more a consequence of lacking the required resources to move rather than a product of accumulated local wealth and prosperity.

26 Still, the fact remains that despite a prolonged period of out-migration, late 19th-century Burton Parish remained populated by large numbers of persistent families, the majority of whom, since they were headed by land-owning farmers, were literally rooted in the parish’s soil. The persistence of farm people in late 19th-century Burton was in large part a creation of the selective nature of the out-migration process in the parish. As the work of Betsy Beattie and others has highlighted, persistence and mobility were often complementary strategies, especially in cases where household members relied on migration, temporary and otherwise, to generate the employment income necessary to sustain the family farm.64 Was the situation in Burton an anomaly? Perhaps the persistence of the parish’s farmers, particularly those with property along the fertile Oromocto or St. John River valleys, was merely a product of the better quality of soil and accessibility to markets that their geographic location provided. No doubt there is some truth in this; but only a minority of Burton’s farmers owned property along one of the major rivers. In addition, provincial agricultural leaders frequently noted that the area’s over-reliance on the production of hay, a crop which required only limited seasonal labour, actually encouraged young men to abandon the farms.65 Moreover, Phyllis Wagg’s findings in Richmond County, Nova Scotia make it clear that Burton Parish was not the only region of the Maritimes where farm families persisted in large numbers.66

Figure Three : Precedence Rate of Families in Burton Parish

Display large image of Figure 3

27 The highly persistent nature of farm families in Burton Parish can be taken as an important reminder that community life did not disintegrate in rural northeastern North America even in the midst of the large-scale out-migration of the late 19th century. Indeed Barron suggests that modern scholars, influenced by the concerns expressed by 19th-century urban intellectuals, have overestimated the social impact of rural depopulation on many long-settled communities. Far from being unstable, socially deprived shadows of their former selves, such communities became increasingly close-knit locales that, Barron suggests, "facilitated the retention and adaptation of older values".67 Despite the poor performance of the overall economies, life in such communities marched on. While it is undeniably true that widespread out-migration did much to alter life in the region, any analysis of Maritime history in this era must also carefully consider those who persisted in their home provinces over the long term. In particular, as the example of Burton Parish suggests, more attention must be given to the region’s long-resident farm families.

28 Although farming was the largest occupation in the Maritimes into the 1950s, we know little about the values and aspirations that shaped agricultural society in the region over the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Little scholarly attention has been directed to the role of rural communities and their leaders in shaping the Maritime Provinces’ response to the economic and social problems of the era. Local participation in farmer-dominated political organizations such as the Patrons of Industry and the United Farmers, for example, has largely been either dismissed or ignored.68 An analysis of the social and political evolution of the region’s rural communities, and those who claimed to represent their interests over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, may also go a long way towards determining if there was any validity to the perception promulgated by earlier generations of Canadian historians that Maritimers of this era were essentially conservative in their social, political and economic outlook. In recent years, E.R. Forbes and other prominent scholars of the region have produced works that question this assumption.69 But if such an attitude was at all prevalent one would expect to find evidence of it among the region’s rural communities, populated as they were by long-resident farm families.

Notes