Private and Government Funding:

The Case of the Moncton Hospital, 1898-1953

W.G. GodfreyMount Allison University

1 IN JANUARY 1941 HOSPITALS WERE "at a cross-roads never before reached in history", Moncton Hospital superintendent Alena J. MacMaster informed her board. An "entirely new philosophy of hospital financing" had come of age, she said. It now seemed widely accepted that "private and voluntary philanthropy as a source of revenue" would be supplanted by "government or alternative forms of support".1 In reality, as MacMaster was well aware, this shift of responsibility was not a sudden epiphany but rather had been underway at her own institution throughout the interwar years. She also knew that this transformation of public attitude and policy was far from complete. Nevertheless, her remarks revealed quite a substantial change in hospital funding perceptions compared to the optimistic expectations of the Moncton Hospital’s first president, George B. Willett, roughly 45 years earlier. As he stated in 1895, "It was not proposed to build this hospital on the charity plan". A few years later, he was elated that "receipts from paying patients [had] considerably increased"2 and were becoming ever more important. This reliance on private support contrasted with MacMaster’s 1941 perception of a shift to government or alternative forms of support. But both situations were some distance away from the late 1950s, when hospital care insurance measures and a Public Hospitals Act, as Hugh J. Whalen noted, "vested control of hospital services largely in provincial hands and imposed a premium-type insurance program applicable to all users".3

2 To a considerable extent, the Moncton Hospital completed the journey from a largely privately funded hospital to an increasingly governmentally funded institution during the 1898 to 1953 period. In the area of major capital expenditures, private donations had been supplanted by grants from various levels of government. Operating costs were, by the 1950s, met by enhanced provincial contributions, by a more substantial municipal and county role in hospital finances and by patient payments, whether direct or from a third party (government or hospital insurance schemes). A focus on changing patterns in hospital finances from the vantage point of a single institution allows for exploration of an often neglected issue which is acknowledged to have "played a key role in shaping the modern hospital".4 It must be recognized that "long-standing governmental unwillingness to intrude in the delivery" of hospital care5 prevailed in both the United States and Canada for much of the period under examination. Yet, as Rosemary Stevens has demonstrated, in certain parts of the United States and at certain times, government funding support for hospitals deserves attention because it was present and significant.6 Unfortunately studies of Canadian hospitals are not yet a match for the work of Stevens, Charles Rosenberg and Paul Starr,7 among other scholars treating the American hospital system. What both countries do have in common is a tendency to allow the final outcome to influence the emphasis: in the American case, the emergence of hospitals as private money-makers shades various studies with a critical tone,8 while in Canada the eventual emergence of a government presence through medicare and hospital insurance leads to an almost "relentlessly progressive"9 tone. While American studies question "why there is no national health insurance in the United States",10 Canadian scholars focus on key decisions leading to Canadian health insurance, the medical profession’s reaction to these changes or a present-minded and positive presentation of the evolving state role.11

3 What is not captured, however, is how small Canadian general hospitals (which were the overwhelming majority of Canadian hospitals)12 survived and grew in the first half of the 20th century. This is a particularly timely question in an era of government cutbacks in health care services and much talk of what would amount to a return to privatization of such services. Admittedly, G. Harvey Agnew has provided a worthwhile overview of the Canadian hospital system which benefited from his direct involvement in questions such as standardization and hospital financing.13 But what is lacking is an updated and detailed synthesis of the tide of hospital histories which crested in the last quarter century.14 Such a synthesis would have to wrestle with the diversity within the system: hospitals launched with substantial endowments and connected with major medical schools; hospitals which could, from day one, make a strong case for substantial provincial government or municipal support; and hospitals which were independent community ventures launched with broad-based private support which quickly turned to reliance upon paying patients because initial government support was token and private philanthropy was limited.

4 The Moncton Hospital falls into the latter category. From its humble 1898 birth in the Moncton almshouse, with less than 20 beds and $600 in renovation costs, the Moncton Hospital grew to a $3 million, 225-bed facility in 1953; but two site changes and many difficult financial arrangements marked this transformation. While the funding of public general hospitals in Ontario has been examined utilizing an individual hospital perspective,15 the New Brunswick hospital situation, and that of the Maritimes in general, have only been alluded to in hospital histories16 which have largely neglected any precise delineation of the funding realities behind the evolution of these institutions. In New Brunswick the situation was further complicated by the division of hospital responsibility between provincial, county and municipal authorities with the gradual intrusion of a limited federal presence. This conflicting thicket of responsibility, or evasion of responsibility, was only cleared away by federal-provincial actions in the late 1950s and the Equal Opportunity programme of the 1960s.17 The Moncton Hospital is a particularly intriguing case study because, from the outset, it served not only its urban constituency but also the surrounding counties of Westmorland, Kent and Albert and, initially, French- and English-speaking communities. When provincial, municipal and county support was limited or static, paying patients from the constituencies served were vital to the survival of the institution. Consequently, funding realities were closely tied to usage figures and governmental policies (or non-policies) concerning hospital support. The hospital also depended on its own resourcefulness in adjusting its services to remain an attractive and worthwhile proposition deserving the support of the communities it served.

5 As late as 1953 the "financing of public hospitals [in New Brunswick] under the voluntary system" was described as "very much of a ‘hit and miss’ affair"18 by Doctor Donald F.W. Porter, the executive director of the Moncton Hospital. The same can be said of the situation in turn-of-the-century New Brunswick. Hospital advocates in communities such as Moncton appealed to private donors for the support necessary to establish a hospital and, if these supporters lobbied successfully, small annual grants might also be secured from the various levels of government. The degree of government support depended upon the effectiveness of the hospital case, the political weight exerted and the response of taxpayers at the local level. Moncton was fortunate that by the mid-1890s a very active women’s organization, the King’s Daughters (later to be reshaped into the hospital’s Ladies’ Aid), took up the hospital cause. Allied with prominent citizens, clergymen and physicians, their campaign sparked press coverage and public debates until incorporation of the Moncton Hospital as an independent body, to which Moncton city council might make grants if the ratepayers approved, was achieved in 1895. Donations from the general public were actively solicited but municipal and provincial support was also required before any hospital could open its doors. A further three-year campaign finally led to the far from lavish city council commitment of $600 to renovate for hospital use the second and third floors of the Moncton almshouse, actually located outside of Moncton at Léger Corner (present-day Dieppe).19 Although sharing quarters with the city almshouse which still occupied the first floor was not the most auspicious beginning, hospital supporters had nonetheless achieved their goal. On the eve of the 11 June 1898 opening ceremonies, hospital authorities received word concerning a $300 grant from the provincial government which, before the first year elapsed, was almost matched by a $200 grant from Moncton city council.20

6 From its early planning moments, backers of the hospital had made clear that the institution must serve both paying and non-paying patients. As a result, there was a consistent effort to avoid the image of the hospital as only serving charity cases and thus only meeting the needs of the poverty-stricken within society. No doubt this perception, of a hospital as "fundamentally a charity for the custodial care of the sick poor",21 was reinforced by the initial location of Moncton’s hospital in the almshouse. A different location as well as more spacious quarters could remedy this perception problem and, by the summer of 1901, the case and campaign for expansion on a new site were launched.22 Over the next several years a successful and well-publicized fund-raising campaign produced donations exceeding $20,000, culminating in November 1903 with the opening of a new and larger 50-bed Moncton Hospital on King Street. The response from Moncton and surrounding areas was heartening and represented a resounding vote of confidence in the hospital’s contribution to the community. Both the private and public sectors, individuals and organizations responded generously. Leading the way was the Ladies’ Aid, with numerous endeavours and donations, along with another group of women called the Ladies’ Hospital Sewing Circle, led by Mrs. (W.F.) Emma Humphrey. Together the two groups raised more than $5,000 for the hospital fund. The Ladies’ Hospital Sewing Circle was first off the mark with more than $2,000 achieved by March 1902 to purchase the selected new site, the Harris homestead on King Street.23 The Ladies’ Aid and the Ladies’ Hospital Sewing Circle actively solicited individual private donations as well as raising funds through public concerts, teas, "At Homes", parlour concerts, bazaars and soda fountain sales.24 The churches provided supportive sermons and collections with Father Henry A. Meahan offering especially strenuous support at Saint Bernard’s Roman Catholic church. He suggested that "every wage earner lay aside the full earnings of one full day and give that amount to the hospital building fund".25 Workers in various industrial enterprises – for example, the male and female employees of the cotton factory – gave at work.26 A major source of support was the Intercolonial Railway, whose employees in the different shops combined to contribute almost $300. Government grants were vitally important and a now firmly committed Moncton city council gave $5,000, while Westmorland County council contributed $2,000 and Kent County donated $500. Of the approximately $20,000 raised, more than one-third came from municipal and county governments and the remainder from private contributions.

7 Conspicuously absent from the government contributions was any funding from the provincial government. Although its annual grant to the operating expenses of the hospital rose and fell through the hospital’s first decade (it was $500 in 1909),27 the province assumed that the cost of new buildings or extensions should be met by the local governments and private donations. As in other provinces, however, public health problems and the growing hospital system forced the government to slowly expand its involvement. It did so reluctantly, and the province’s experience with hospital care for tuberculosis, "the number one killer in New Brunswick" at the beginning of the 20th century, reinforced this reluctance. Faced with a substantial private donation of buildings and land, the New Brunswick government established the Jordan Memorial Sanatorium in River Glade, which welcomed its first patient in 1913. Both costs and political criticism quickly mounted until, by 1916, the government was contributing $25,000 to the Jordan Sanatorium at a time when the total expenditure on grants to the general hospitals in the province was only $10,000. This experiment with "government-run health institutions" had become "a sink-hole for money" and, ironically, was not "an effective form of control" for the disease. A desire "to evade financial commitment lingered" in the area of tuberculosis treatment and no doubt influenced the government’s general policy of aid to hospitals.28

8 Despite this experience, concern about public health remained an issue and, in 1917, Doctor William F. Roberts was appointed "the first Minister of Health in the Empire". As a result of the New Brunswick Health Act which was passed a year later, this new department, among other activities, supervised and provided monetary support for "the Tuberculosis Sanatoria and public hospitals".29 For the province’s general public hospitals, New Brunswick’s financial contribution remained in the form of small annual lump-sum grants which were to cover the cost of indigent, non-paying, public ward patients. In Ontario a more enlightened, if not all that more generous, system of hospital aid had developed. For example, in 1897 Ontario’s Hospitals and Charitable Institutions Act provided per diem grants to public hospitals for the maintenance of indigent patients while an amendment in 1912 outlined as well the municipal responsibility for an indigent patient per diem rate.30 Although there were constant complaints about the skimpiness of these grants, by 1928 the Ontario provincial grant was 60 cents per day while the municipalities contributed $1.75 per day with some hospitals accepting a lump-sum grant from the municipality rather than the per diem rate.31 Any suggestion that the province and municipalities should lower these rates, a rumour in 1932, provoked a horrified outcry.32

9 By 1927 in New Brunswick, the provincial government was funding 14 hospitals with annual lump-sum grants totaling $11,700, ranging from $250 for a 12-bed institution to $3,800 for the 200-bed Saint John General Hospital.33 The Moncton Hospital received $700 that year. This amount increased to $2,000 in 1930 when its bed capacity went from 86 to 125.34 All provincial hospital grants were reduced by 25 per cent in 1932. As a result, Moncton’s grant fell to $1,500 and remained at that level until after the Second World War. In the 1930s the provincial government made it clear that these lump-sum payments for the care of the indigent were "not based upon per diem consideration" and would continue in this form despite hospital agitation for a switch to the per diem basis.35 The provincial government did legislate in 1923 that the "Cities, Towns, Incorporated Villages or Counties" would have to pay for indigents’ hospital services at the "average cost per diem per patient" in the current year or the year preceding admission.36 The Moncton Hospital opted instead to continue to receive annual grants from its surrounding counties – sporadically in the case of Albert and Kent, regularly from Westmorland – until the hospital switched to per diem requests in the 1930s. Extracting county payments for indigent patients was made even more difficult because of the problem in establishing the residence of patients. Consequently, the provincial government introduced new legislation in 1931 to more closely designate the legal entitlement [settlement] of an indigent patient, to make possible the collection of fees".37

10 If provincial and county government support was limited and slow to increase, at least the city of Moncton’s grant to the hospital rose more rapidly and substantially. It moved steadily upward, reaching $1,500 in 1908-09, $3,500 in 1918-19 and $9,000 in 1929-30. When the total provincial, county and municipal grants in 1929-30 (amounting to $14,700) are compared with the 1926 provincial and municipal grants to similar-sized Ontario institutions, the Moncton Hospital’s government support lagged considerably behind. In 1926, when comparable figures are available, the 96-bed Kitchener hospital received $23,287 in municipal support and $3,319 from the provincial government for a total of $26,606. In the same year, the 100-bed St. Thomas hospital received $12,000 and $5,728 for a total of $17,728, while the 125-bed Stratford hospital received $15,751 and $2,818 for a total of $18,569.38 The gap between these figures and the 125-bed Moncton Hospital’s $14,700 in government support in 1929-30 might have further widened as the Ontario hospitals ended the prosperous 1920s. Not only was government support less than that available at comparable Ontario hospitals but the decline in that support as a percentage of the hospital’s total revenue was far more severe at the Moncton institution. A comparison with the Owen Sound General and Marine Hospital, based in a small town and founded only a few years before the Moncton Hospital, reveals that its provincial and municipal income was 30.7 per cent of its total income in 1910, 23.6 per cent in 1920 and 23.1 per cent in 1930.39 At the Moncton Hospital, 31.6 per cent of its total income came from provincial, municipal and county grants in 1908-09, 20.3 per cent in 1918-19 and 12.0 per cent in 1929-30.

11 Of course, this declining percentage of government support might have been because funds from paying patients had far outdistanced these other income sources, which was not necessarily a negative development. Indeed, the Moncton Hospital’s 1903 move, quite literally out the shadow of the almshouse, paid quick dividends in that the institution shed any image of itself as primarily a charity-care institution. This move to attract paying patients was similar to the process at work in other hospitals.40 Victoria General Hospital in Halifax worked hard to make itself attractive to middle-class patients in the 1890s and 1900s and made careful distinctions between private and public patients in order to attract paying patients. Staff physicians at the Hamilton City Hospital recommended the construction of private wards in 1896 and, one year later, an addition was built "to attract the affluent".41 By 1893, 20 per cent of the Kingston General Hospital’s revenue came from paying patients; by 1907, the Montreal General Hospital had achieved a 29 per cent level; at Owen Sound General and Marine Hospital by 1905 "the fees of paying patients already had become the hospital’s single most important source of income".42 At the Moncton Hospital, while some years witnessed a slip downward in the number of paying patients, the general trend was steadily upward. In 1898-99, approximately 19 out of 70 patients admitted were paying; by 1903-04 in a considerably enlarged facility, 83 out of 181 patients were paying; in 1908-09, 288 out of 497 were paying patients. At the same time, in 1905-06 the 54 per cent of total revenue these patients provided quickly became, as in the case of Owen Sound, the largest financial support of the hospital. In Moncton, paying patients as a percentage of total patients had risen from just above 27 per cent in the first year of operation to nearly 58 per cent in 1908-09.43 This pattern persisted in the pre-Depression period as private paying patients, which included semi-private as well, peaked at just under 84 per cent in 1929-30. The Depression considerably reduced the paying percentage, but it resumed its upward course during and after the Second World War.44

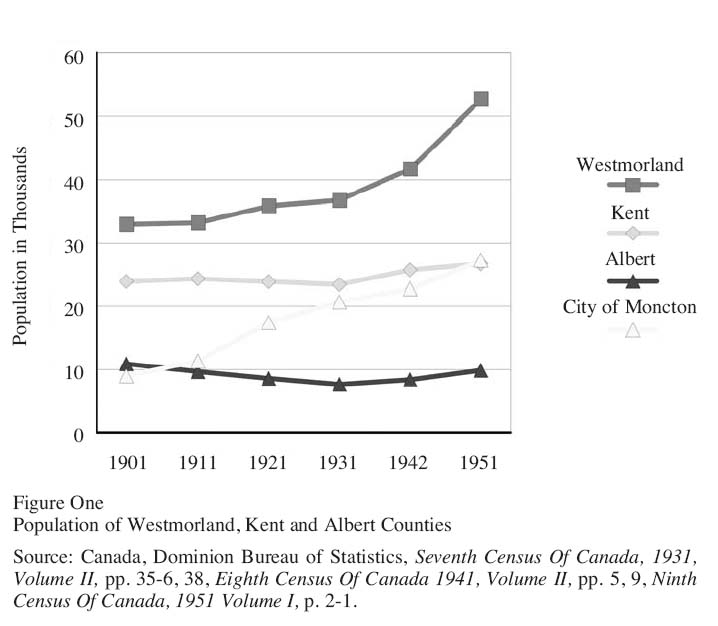

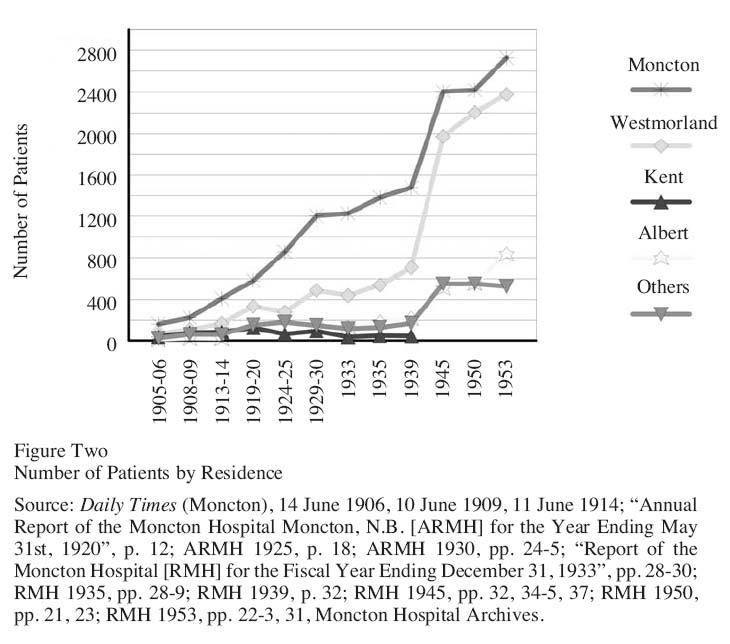

12 Hospital board members carefully watched these numbers but were equally attentive to the residence of the patients using the Moncton Hospital. Moncton was the all-important home base, but patients from the counties had to be attracted as well. At least initially, Moncton offered the smallest potential clientele base compared to Westmorland, Kent and Albert counties. But, as Figure One45 demonstrates, there would be substantial shifts over time in the makeup of the potential clientele, with Moncton and Westmorland County becoming the growth areas while Kent and Albert counties remained relatively stable. By 1911 Moncton’s population had increased to slightly more than 14 per cent of the hospital’s potential clientele, edging it ahead of Albert County which slipped to nearly 12 per cent. Moncton’s population growth further accelerated during the war years, outdistancing the pace of growth in the other primary areas served by the hospital. At the same time, rural depopulation took its toll in Kent and Albert counties as both dropped in population, from 31 per cent to 27.8 per cent and from 12.3 per cent to 10 per cent respectively, in terms of potential clients served.

Figure One : Population of Westmorland, Kent and Albert Counties

Display large image of Figure 1

13 In the years after the First World War, the city of Moncton continued its expansionist trajectory. Although the nature of its basic economic activities significantly changed, in its adjustment the city fared considerably better than other comparable-sized communities in the region.46 Moncton grew in population from 17,488 in 1921 to 22,763 in 1941 or, as a percentage of the total regional population served by the Moncton Hospital, from 20 to 23 per cent. In the same period the population of Westmorland County, excluding Moncton, expanded from 35,899 to 41,723, which represented an increase of less than one per cent in its proportion of the hospital’s potential clientele. Kent County increased in population from 23,916 to 25,817 but declined from 27.8 per cent to 26.2 per cent of the total within this southeastern corner of New Brunswick. From 1921 to 1941 Albert County declined both in population and in potential percentage served from 8,607 (10 per cent) to 8,421 (8.5 per cent). The high hopes of Moncton boosters, and hospital backers, that the city’s growth would be so spectacular as to necessitate separate city and county institutions, were not yet realized, but the growth was substantial enough to put severe pressures on the hospital.

14 Behind Moncton’s own 20-year population increase of 30 per cent lay fundamental changes in its economic and ethnic complexion. Economically, the city underwent a transformation from a primarily industrial community, largely controlled by an indigenous elite, to a branch plant manufacturing centre increasingly dependent on the transportation, warehousing and service sector.47 While the major employer in the city remained Canadian National Railways, the number of its Moncton employees steadily declined from slightly more than 2,500 in 1920 to 1,387 by 1938.48 At the same time other industrial enterprises peaked in 1920 when 90 establishments employed 3,061 people with the numbers of such employers declining to 40 in 1927. These figures levelled off in 1938, with 46 enterprises employing 1,801 workers. This represented "the lowest employment level in this sector since 1923".49 Considerable offsetting compensation was provided by gains in the service sector, such as the T. Eaton Company opening a mail-order house employing more than 750 in 1920, followed by a retail store in 1927. But Eaton’s presence, along with the onset of the Depression, contributed to the 1931 closure of the long-established and locally owned McSweeney department store.50

15 Change also prevailed in the ethnic composition of the city and Westmorland County as the Acadian presence reached new levels of visibility and necessitated an overdue accommodation. In Westmorland as a whole, the French ethnic proportion of the population increased from slightly more than 39 per cent in 1921 to nearly 42 per cent in 1941, while in the same time period the Acadian presence grew 2.5 points to 33.6 per cent within the city of Moncton. Province-wide, New Brunswick’s French-speaking residents soared from 21.8 per cent of the population in 1911 to 35.8 per cent in 1941.51 As the major urban centre which served overwhelmingly Acadian Kent County and an increasingly assertive French-speaking community in Westmorland and within the city’s own boundaries, Moncton had to adjust to this reality. In the area of health services, Acadian leaders pushed for a separate French-language Roman Catholic hospital. In 1922, as a result, the first Hôtel-Dieu de l’Assomption welcomed patients in a renovated house, and by 1928 a new building on the north side of Union Street was opened as the Hôtel-Dieu, which eventually evolved into the Georges-L. Dumont Hospital.52 Even with two hospitals to serve the city and counties, the Moncton Hospital’s patient numbers continued to mount. Through the war and post-war years the city and counties served by the hospital underwent considerable growth. On the surface, Moncton experienced an "unprecedented period of growth" during the Second World War. As many as 15,000 airmen were stationed, however briefly, at five major bases scattered in and around the city.53 In reality, in the decade from 1941 to 1951 Moncton’s growth rate was more than matched by that of surrounding Westmorland County and, in terms of the potential clientele served by the hospital, it was the county that received the greatest percentage increase. Moncton grew by one-fifth in the same period, from a population of 22,763 to 27,334, while Westmorland County, excluding Moncton, increased by more than 25 per cent, from 41,723 to 52,678. In percentage terms Albert County grew considerably as well during this decade, registering a nearly 18 per cent increase, from 8,421 to 9,910. Meanwhile, the largely French-speaking Kent County’s growth was more restrained. Its population increased by almost four per cent as it moved from 25,817 residents in 1941 to 26,767 in 1951. The percentage of residents claiming French as their first language declined slightly in both Westmorland as a whole, to 41.1 per cent in 1951, and in Moncton where francophones went from 33.6 to 30.0 per cent of the city’s population at mid-century.54

Figure Two : Number of Patients by Residence

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 3

16 These changes in the size and composition of the potential population served by the Moncton Hospital were reflected in the shifting usage patterns among patients treated. Because of the increased population in southeastern New Brunswick, hospital admissions grew from 70 patients in its first year of operation55 to 6,466 in 1953,56 necessitating an increase in the Moncton Hospital’s bed capacity to 50 in 1903, 125 in 1930 and 225 in 1953. Despite Moncton’s smaller population compared to Westmorland County, the city quickly became the major user of the hospital, accounting for almost 52 per cent of the patients in 1905-06. It maintained that position until 1953 although, as Figure Two indicates, Westmorland County became the second most important user and closed the gap considerably during and after the Second World War. In 1945, Westmorlanders (excluding Moncton’s) represented slightly more than one-third of patients admitted compared to Moncton’s 44.2 per cent. By 1953 county residents made up 36.7 per cent of the hospital’s total patients while Moncton contributed 42.2 per cent. Kent and Albert counties lagged considerably behind although, gradually, Albert County supplanted Kent as the hospital’s third most important customer. Kent provided 15.9 per cent of the hospital’s clientele in 1908-1909 compared to Albert County’s 4.6 per cent, but by the late 1920s the largely French-speaking residents of Kent were serviced by Hôtel-Dieu and redirected themselves and a portion of the county grant accordingly. Only 1.9 per cent of Moncton Hospital’s patients in 1939 were from Kent County, and by 1945 it was no longer listed separately in hospital statistics. Albert County, on the other hand, contributed increasing numbers until in 1953 its residents amounted to 12.9 per cent of the Moncton Hospital’s patients. The only substantial downturn in patient admissions came in the early 1930s and affected Moncton as well as all the counties.

Figure Four : Residence of Public and Ward Patients

Display large image of Figure 4

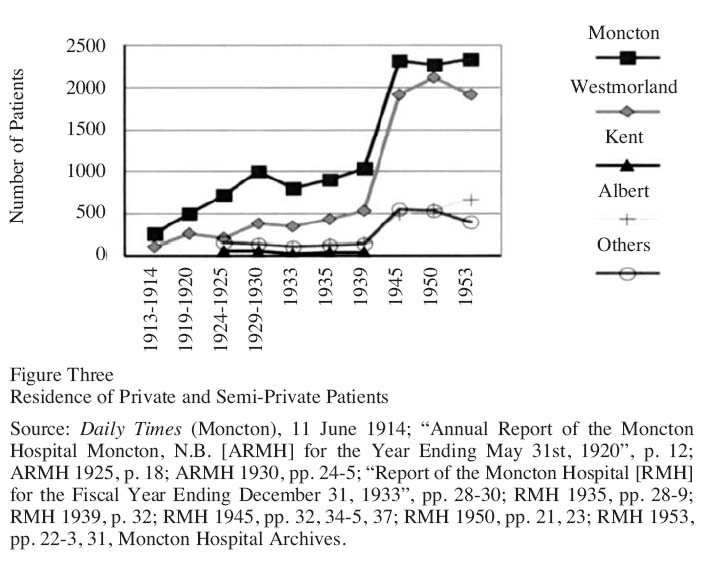

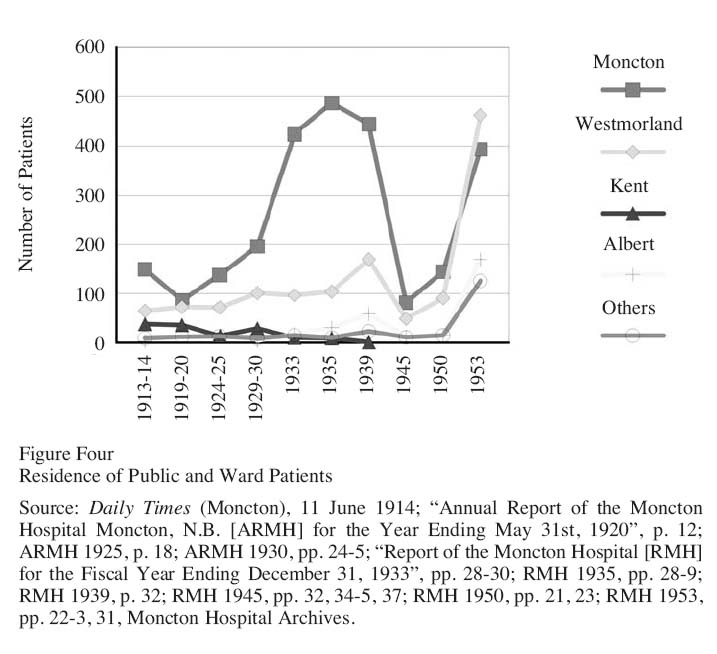

17 Increases in county or city patient numbers usually brought stronger hospital solicitation for increased support, particularly if the increase was among non-paying or low-paying public/ward patients. Figures Three and Four examine the residence of private and semi-private patients compared to that of public/ward patients. On the positive side, from the vantage point of hospital board members, the city of Moncton contributed handsomely to hospital revenue by consistently providing the largest number of private and semi-private patients. On the negative side, during the economically troubled 1930s, the city delivered by far the largest number of public/ward patients. Among the two largest hospital users, Moncton and Westmorland County, their ratios of private-paying versus public/ward patients roughly tracked each other with two exceptions. In the 1910 to 1918 period Moncton went from a nearly 60:40 per cent private/public ratio to a roughly 73:27 per cent private/public balance. To the chagrin of Moncton Hospital officials, Westmorland County’s ratio moved in the opposite direction, from approximately a 63:37 per cent private/public ratio in 1910-11 to a 52:48 per cent proportion in 1917-18. Within two years, however, Westmorland pushed its paying patients up to 78 per cent of the county’s patients admitted and, throughout the 1920s, all parties maintained a healthy ratio of paying versus non-paying patients. The Depression considerably altered this patient balance as increased use of the public wards, especially by Moncton residents, caused concern among hospital administrators. Moncton dropped sharply to a 65.5:34.5 per cent paying/non-paying ratio in 1933 and only recovered to a 70:30 per cent ratio in 1939. Westmorland experienced a far less severe decline, dropping only two points over the same period to approximately a 76:24 per cent ratio in 1939.

Figure Five : Per Diem Patient Costs

Display large image of Figure 5

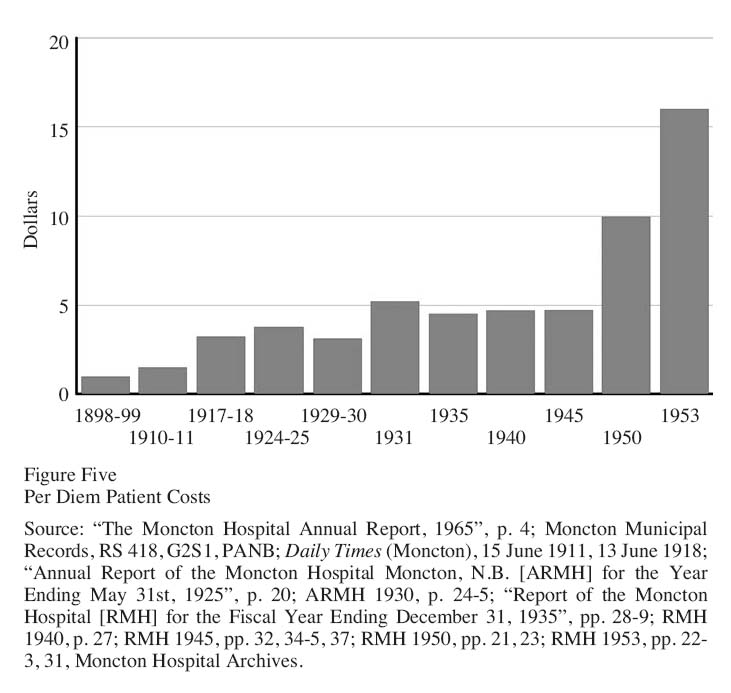

18 There was a greater use of public ward facilities in the difficult thirties as patients were unable or unwilling to pay the rates charged by hospitals for private and semi-private rooms.57 Among potential patients, a willingness to avoid hospital treatment if at all possible also took its toll. Across Canada, hospital-bed occupancy declined while Prince Edward Island, Ontario, Manitoba and New Brunswick were especially hard hit by the increase in public ward patronage and a corresponding fall in private and semi-private usage. Hospitals adjusted by transforming private rooms into semi-privates and semi-privates into public to secure more ward units.58 These changes in the use of hospital facilities resulted partly from the Depression, but there also was a growing public reaction against rising hospital charges. Rates were tied to costs and, at the Moncton Hospital, as Figure Five indicates, per diem costs per patient increased steadily and decreased only slightly for brief periods in the late 1920s and mid-1930s before resuming a steady rise upward.

19 The Moncton Hospital’s per diem patient cost and the rates it charged patients in the 1899 to 1932 period went through two distinct phases. In the first, paying patients bore the brunt of the increased rates. In the second phase, the burden was shared, although the largest increases were directed at public ward occupants or their patrons. From 1899 to 1918, when the per diem patient cost went from 99 cents to $3.20, the public ward patients who paid, admittedly few in number, faced a charge which remained unchanged at $3.00 per week or 43 cents per day. Private patients initially paid $6.00 to $10.00 per week or 86 cents to $1.43 per day.59 Ward patients were treated by the hospital staff doctors free of charge while private patients were allowed to have (and to pay) their own doctors. In addition to the lack of privacy in the large public wards, other distinctions, such as more restricted visiting hours for public ward patients, made clear the different status accorded private and public patients. In 1914 the charge for a private room increased to $12.00 per week or $1.71 per day. This was followed in April 1918 by the introduction of a sliding scale for semi-private and private rooms which brought their daily cost up to the $2.00 to $3.71 range.60 Compared to the 1917-18 per diem patient cost of $3.20 (a 223 per cent increase from the hospital’s first year of operation), most of the rates were not keeping pace, although the roughly 130 to 160 per cent increase in private and semi-private rates made clear on whose funds the hospital depended. Moreover, rising costs for anaesthetics, drugs and operating room use, coupled with surgery fees, x-ray charges and laboratory expenses might add considerably to the private and semi-private patient’s bill.

20 During the next phase, from 1918 to 1932, the per diem patient cost went from $3.20 to $5.21, an increase of more than 62 per cent. In 1923-24 the Moncton Hospital’s public ward rate increased to $5.00 per week or 71 cents per day which patients were now urged to pay if at all possible.61 Better ward accommodation arrived when a new hospital addition opened in 1930 with four-bed wards replacing the large public wards.62 In the early 1930s, rates reached the levels where they would remain for more than a decade. The cost for public ward patients from adjoining counties was set at $2.00 per day, paid by the patient or the county, while Moncton public ward patients were "expected to pay $1.50 per day for their treatment". Public ward patients from any other counties or municipalities were charged at approximately the prevailing per diem cost.63 Semi-private patients, by 1931, paid $2.50 per day while private patients were offered a range of options from $3.50 to $6.48 per day.64 As a result of these changes, public ward rates had doubled or tripled in the 1918 to 1932 period while semi-private charges grew by 25 per cent. Some private room rates were up as much as 74 per cent, while those at the low end of the scale had actually been reduced by some five per cent. While both per diem patient cost and the hospital rates charged had increased substantially, the Moncton Hospital situation was roughly comparable to that of hospitals in the rest of Canada.65

21 Bringing the Moncton Hospital in line with other modern hospitals was the major goal and eventual achievement of Alena MacMaster, who commenced more than a quarter-century of service as hospital superintendent in 1919. This required a considerable and costly expansion of services and space. In attracting MacMaster to Moncton, optimistic descriptions had been offered concerning a 50-bed enlargement, establishment of maternity facilities and enhanced x-ray services.66 These promises now rang rather hollow since assumptions about increased provincial funding and vastly improved municipal support remained unfulfilled. Hospital board president A. Cavour Chapman improved prospects in the latter area by winning the mayoralty in 1920. He was re-elected in 1921, and there was a strong connection between his outspoken presence in municipal politics and the steady increase in the city’s hospital grant.67 At public hospital functions reported in the press, when he wore both hats as city mayor and hospital president, "His Worship Mayor Chapman" was quite willing to deplore the low level of Moncton’s annual hospital grant as "unworthy of the City of Moncton", while asserting that "the amount available . . . should be nearer $150,000".68 More realistically, the Ladies’ Aid, while not losing sight of a new hospital, now called for "immediate steps [towards] temporary extensions to accommodate patients".69

22 Abandoning for the moment the dream of a new wing for the hospital, in the spring of 1920 the hospital board approved the purchase of four lots and two houses next door to the hospital for a limited expansion. Along with renovation work and structural changes, this added 36 beds to the hospital’s capacity but also produced a substantial $35,000 debt.70 While advising the hospital board that the Ladies’ Aid "would continue to give their assistance" to pay this debt, a resolution was passed by the membership that the hospital "Board and the [Ladies’] Aid [should] jointly meet the City Council to discuss the advisability of the city financing the Moncton Hospital".71 Creeping municipalization of hospital services was thus openly proposed and debated by the hospital supporters who had been most successful in meeting its needs through private donation campaigns.

23 Another community service organization was also demonstrating a new sensitivity to hospital needs and probing for more effective long-range solutions to the hospital funding problem. In August 1920, doffing his hospital and mayoralty hats in favour of his Moncton Rotary Club apparel, A. Cavour Chapman presided at a Rotary Club meeting where the plight of the hospital was addressed. Eventually the Rotarians decided that the city should play a much bigger role in financing the hospital and it was suggested that "the city might float a bond issue, the same as financing any other civic enterprise". This basic funding should be complemented by a fund-raising drive throughout the "city and neighbouring counties" along with increased and substantial assistance from "the provincial government and nearby county councils".72 A combination of the debenture approach suggested by the Rotary Club with the greater municipal role and responsibility proposed by the Ladies’ Aid was the solution embraced by the hospital board.

24 With the approval and co-operation of the Moncton city council and the New Brunswick government, two acts were passed by the provincial legislature in April 1923. "An Act to Enable the Trustees of the Moncton Hospital to Issue Debentures"73 allowed the board to issue $20,000 in debentures which would pay up to five per cent annual interest, and which were to be paid off over a 20-year period. A sinking fund, amounting to at least three per cent annually of the total debentures, had to be established from the hospital revenues to pay off the principal, and the hospital would also have to meet the annual interest payments. Funds raised in this way were to eliminate the mortgages and other indebtedness of the hospital. Another measure allowed the city of Moncton to "guarantee the payment of the principal monies and interest" of the hospital’s debentures should the Moncton Hospital ever have to default.74 In May 1924, with the paying-patient revenues it generated, along with funds raised from the sale of 400 bonds valued at $500 each and a generous $11,500 donation from the Harvey Horseman estate, the Moncton Hospital was able to report that it had retired $20,000 in mortgages, paid off a $15,000 bank note, paid the interest on its bonds and set aside $650 for its sinking fund.75

25 The state of hospital finances, on the surface at least, had vastly improved. In reality, while renovation and re-equipment expenses had been met, the need for a new hospital wing would resurface quickly. Neither MacMaster nor other hospital supporters had forgotten that, even with expanded services and temporary renovations, the hospital still required additional space. In 1925 MacMaster reminded the board of this need and, in reporting on the hospital’s 1927-28 activities, produced figures that at times it "operated at more than 100% of its rated capacity", as on occasions there were 98 patients but a "normal capacity of eighty-six beds". While the daily average number of patients for that year was 65, the realities of overcrowding at times and inadequate services in some areas had to be addressed. MacMaster concluded her report in an ominous tone: "It is not without reason that your Superintendent predicts that the next few months in the life of the hospital will determine, in a large measure, its future destiny and the hope is expressed that during this critical period those who shall be responsible for its guidance may be endowed with foresight, integrity, and prudence".76 The disturbing reality was that, in the year just passed, the Moncton Hospital had launched the most ambitious fund-raising campaign in its history and returns by the spring of 1928 were well short of the goal set.

26 In all probability, the $125,000 target set by fund-raisers was unrealistic in a community of Moncton’s size. In 1903, with a little less than half as large a population, the city, helped by the counties, had been able to raise a little more than $20,000 for the hospital, which was regarded as an heroic achievement. To set the goal six times higher in 1927 was probably overly optimistic, even in, for Moncton at least, the relatively buoyant economy of the 1920s. As well, by 1927 francophone residents had their own hospital campaign which required their financial support.77 Nevertheless, when the final returns were in the total raised stood at $74,000, with a further $7,000 in unpaid pledges.78 Despite this respectable achievement, in the spring of 1928 Alena MacMaster had reason to wonder how the obvious shortfall in funding would be met. With the co-operation of Moncton city council, further debentures were seen to be the answer.79 Not all debentures authorized were issued, since donations or ordinary revenues could be used instead and the hospital was reluctant to float bonds not guaranteed by the city. Only an approximation is available for the final total cost of the hospital addition, furnishings and equipment, with $400,000 the usual figure cited. In 1931, however, the bonded indebtedness of the hospital had increased by $300,000, of which $280,000 had been guaranteed by the city of Moncton and $20,000 was hospital guaranteed.80 In addition, the original 1923 debenture issue of $20,000 had not yet been paid off.

27 On opening day in October 1930, optimism and confidence were not yet eroded by the Depression. Alena MacMaster was probably typical of many when, a few months earlier, she had proudly outlined the eagerly awaited expansion of services which the new 75-bed wing (which brought the total capacity to 125 beds) would bring to the Moncton Hospital. "We hope to immediately develop a regulation Out-patient Department", she wrote, noting as well plans for a physiotherapy department, an eye, ear, nose and throat clinic, and for expanding and shifting other departments into the new quarters. The changes, she honestly admitted, required additional staff which meant "additional operating expenses [and] a noticeable advance in our per diem cost".81 She was right, as the per diem cost, which had actually moved downward in the late 1920s, from $3.78 in 1924-25 to $3.09 in 1929-30, would soon rise to $5.21 in 1932 and be at $4.72 in 1940. The general deflation of the 1930s apparently had only a limited impact on hospital expenses. Faced with rising costs, the traditional answer had been increased charges. But by 1932 both private and public charges were at levels where further increases would be difficult if not impossible. Patient charges were laid out in a special issue of The Busy East in 1931 which focused on the Moncton Hospital as "A Great Community Asset". At times, the magazine was defensive about the rates, for there was a widening consumer reaction against further hospital rate increases demonstrated most forcibly in a decline in hospital usage. The Busy East emphasized that there were "no extra charges" to public ward fees, that additional charges paid by private and semi-private patients were "slightly below the fee[s] usually assessed" at other institutions and that the hospital rates were actually quite "moderate". Moreover, given the real per diem operating costs of the hospital, compared with what municipality, county or part-pay public ward patients contributed, the hospital was being forced to subsidize patients "from its own resources or earnings". By 1931 as well, reported The Busy East, the "problem of collecting the money due the hospital for the care of patients is a constant one, especially in these days of depression and unemployment".82

28 As the Depression deepened, the hospital’s financial situation in 1933 deteriorated to the point where the ratio of patient fees versus government support underwent a substantial readjustment, and the city of Moncton emerged with significantly increased responsibility for the hospital. The total revenues of the hospital fell from just more than $122,000 in 1929-30 to approximately $86,500 in the 1933 fiscal year, partially because of a decline in the number of patients admitted, from 2,087 to 1,955, and, more importantly, because of the surge in the number of public ward patients. The decline in paying patient revenues was particularly noticeable, when they bottomed out at $62,823 in 1933. But the increased number of public ward patients, the inability of the adjoining counties to meet their financial responsibilities for several years (a temporary phenomenon rectified in 1935) and the obvious incapacity of the hospital’s strained resources to meet its debenture obligations all had contributed to a financial crisis.83

29 Even with total revenues well above the $100,000 mark, it would have been extremely difficult for the hospital to meet on its own the annual debenture interest payments on $320,000 worth of bonds plus sinking fund obligations and also cope with its other increased expenditures. Although faced by the need to pare expenditures, a reduced tax base, uncollectible revenues and a growing relief burden, Moncton city council responded to the challenge.84 The city’s annual grant to the hospital increased drastically, taking different forms in response to the hospital’s Depression woes. At a city council meeting in late February 1931, with the brief explanation that hospital bonds had been guaranteed by the city, approval was given to the regular $9,000 grant as well as to $12,000 for interest on hospital debentures and $3,679 for its sinking fund.85 In 1932 the city’s formal grant dropped to $8,100 but it was supplemented by a grant of $14,000 towards the hospital’s debenture interest and a $4,757.61 sinking fund contribution, for a total of $26,857.61. By 1935 the Moncton contribution took the form of a $5,000 grant for indigent patients, $14,000 for interest on the hospital bonds and $4,292.40 as a sinking fund grant, for a total of $23,292.40.86 City support, as never before, had become a vital factor in the fiscal stability of the hospital. In addition, over a ten-year period the balance between private patient revenues and total government grants had significantly changed. In 1924-25 paying patient revenues of some $45,200 represented two-thirds of the hospital’s total revenue, while government grants amounting to $12,000 made up about 18 per cent of the total. In 1935 patients paid just under $75,000, or about 64 per cent of the hospital’s total revenue, while government grants/payments did not quite reach $32,000, or approximately 27 per cent of total revenue. More prosperous times did not substantially alter this new ratio since in 1939, patient fees represented 62 per cent while government grants/payments were a bit more than 26 per cent of the total revenue of nearly $134,000. The major government supporter was the city of Moncton, providing almost three-quarters of government funds available in 1935 and about two-thirds in 1939.87

30 In other Canadian communities as well, municipalities had emerged as the major government support for local hospitals, but with uneven results. Some hospitals were forced to close because of deficit situations and, in some cases, municipal financing was badly disrupted by the burden of hospital costs.88 In New Brunswick, and in Moncton more specifically, the perils of municipal over-reliance, or over-commitment, were recognized, and alternative sources of support were sought. Obviously, the provincial government was one possibility. By 1934 New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island were the only provinces still offering lump-sum payments to hospitals instead of the per diem grant schemes for indigent patients that were in place in other provinces. Three of the western provinces went even further in their support, with per diem grants covering all patients.89 Per diems were assessed as delivering more funds than lump-sum grants, and per diems for all patients would be even more of an improvement. But a 1935 recommendation by the New Brunswick Hospital Association that the provincial government "increase its subsidies to hospitals by making a per diem allowance per patient" available,90 produced no change in provincial policy. As the Second World War broke out, New Brunswick provided $19,162.50 in hospital grants for 17 institutions, lump-sum grants varying from $187.50 to $3,750 depending upon the bed-capacity of each hospital.91

31 Other options such as group hospitalization or even national health insurance provoked considerable discussion. Given the state of provincial finances and federal caution, compulsory national health insurance appeared some distance away. Private group hospitalization schemes, however, seemed attainable and, in the Maritimes, they were enthusiastically embraced.92 Already by the late 1930s "amazing developments" were reported in schemes guaranteeing hospital care to groups of individuals in return for monthly or annual payments. Approximately 30 such plans had been created across Canada, including a Moncton experiment.93 Alena MacMaster had been an early proponent of such schemes and, at least partially at her instigation, a Group Hospitalization Service Commission, sponsored by the Moncton Hospital board and Hôtel-Dieu, emerged in 1937 and formally incorporated in April 1939.94 Urging an emphasis on group subscription rather than what MacMaster felt to be the "actuarially unsound" individual enrollment in plans, the Moncton Hospital superintendent was pleased to report the success of the new plan. In 1940 four to five per cent of the patients admitted were under this hospital care scheme. They "received 1,382 hospital days service at a charge to the Plan of $7,586.50".95 MacMaster’s valued assistant, Ruth C. Wilson, resigned in 1943 to play a leading role when the Maritime Hospital Association formed the Maritime Hospital Service Association, which eventually became part of the Blue Cross organization.96 Two years later MacMaster commented that both the Group Hospital Service Association and the Blue Cross "have served the Hospital well" and were "expanding State and province wide". Acknowledging the hospital’s space problems, she expressed "regret [that] we cannot always provide the desired accommodation" for patients covered by such plans.97

32 By 1953 Blue Cross had become the dominant player in this sector. It absorbed the Moncton Group Hospitalization scheme in 1949, which brought in the Canadian National Railways employees who had been covered by the older and more expensive "preferred service" plan ($2.20 per month for family coverage). Railway workers, and other Monctonians who had used the Group Hospitalization plan, now secured semi-private coverage for $1.50 per month, and ward accessibility, previously not part of their plan, at an even lower monthly premium.98 This was a major factor in the surge of ward patient numbers at the Moncton Hospital from 1950 onward.99 By 1948 hospital insurance in New Brunswick was estimated to cover just more than 24 per cent of the province’s total population, and at least 3,000 Moncton area residents were added to the Blue Cross subscriber lists under its 1949 expansion.100 Across Canada by 1952, approximately 5.5 out of 12.5 million Canadians (excluding residents of British Columbia and Saskatchewan since they had compulsory provincial government hospital care plans) had voluntary hospital insurance coverage.101

33 Hospitals clearly benefited from hospital insurance plans, but a large number of potential patients remained uncovered. A national health insurance scheme could provide the universal coverage to make hospital care accessible to all. The Second World War and post-war years witnessed not only the expansion of private health insurance but the growth of expectations and support for an always imminent but never quite implemented national health insurance programme. All political parties, it was reported in 1942, were "on record as approving health insurance" in general, although when was not clear.102 A Gallup poll the same year revealed that 75 per cent of Canadians were willing to pay "a small part" of their monthly income for medical and hospital care.103 Further polls in 1944 and 1949 demonstrated even more support, at the 80 per cent level in both instances, for a national health plan whereby a flat rate payable each month would provide "complete medical and hospital care by the Dominion Government".104

34 The federal government had emerged as a potential major player in the field of hospital care but its intervention required provincial co-operation which was not easily secured. The Heagerty Committee report, presented to Parliament in the spring of 1943, was welcomed as "the most comprehensive report on health insurance ever compiled in this or any other country [and] of vital concern to every doctor, nurse and hospital trustee in the country". It was assumed that "this or similar legislation [was] inevitable".105 Expectations for immediate federal legislation were dashed at the post-war Dominion-Provincial Conference on Reconstruction several years later when the federal government’s health insurance measures were presented as a part of its "Green Book Proposals". Once that conference collapsed in disagreement, "the health insurance proposals were, if not dead, at least in limbo".106 Resurrection came in May 1948 when Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King announced a national health grants programme in the House of Commons. Thirty million dollars annually for an initial five-year period were committed to health care. The largest item was a $13 million annual grant for hospital construction. For a province to access the construction funds it had to match the federal funds, and local support, municipal or voluntary, was required. Hospitals could also profit, if their provinces participated, from allotments available for tuberculosis and venereal disease control, funds for professional training and money for cancer research and control. In addition, federal funds were to be granted for health surveys, general public health, mental health and the care of "crippled children". The hospital construction grants, venereal disease and cancer control programmes were on a matching-cost basis. However, the other grants were non-matching and, except for the health survey funds, all involved recurring funding, and several were to be increased.107 A complete national hospital insurance scheme had not yet been achieved but the new federal programme was a major contribution to health care in Canada and to hospital development. Provincial governments, even those in the poorer provinces, would find it difficult to resist what was offered.

35 The New Brunswick government welcomed and soon shared in these federal health care programmes. Prior to this federal initiative, New Brunswick’s post-war tax-rental arrangement with Ottawa and an increase in the province’s normal revenues combined to create "a tremendous revenue increase".108 Stung at the same time by criticisms from the New Brunswick Medical Society about the total inadequacy of medical services in the province, including "a gross shortage [of] hospital accommodations of all types",109 the traditional policy of limited aid to hospitals underwent considerable change. At the 1947 session of the legislature, provincial grants to hospitals were raised from slightly more than $20,000 annually to approximately $125,000 in 1948 when the increase took effect. Hospital grants were now to be 30 cents per patient-day for all hospital patients for the first 5,000 patient-days ($1,500) and then 20 cents per day for each additional patient-day.110 In 1951 the grant was increased to 50 cents per patient day.111 As its own grants were revised upward, the provincial government also put pressure on municipal and county governments to increase their contributions.112 There were still severe criticisms from the provincial director of hospital services about "inadequate funds" available to his department, delays and uncertainties in the allocation of construction funds and the lack of planning and study to achieve an integrated hospital system.113 Despite such serious deficiencies in provincial health policy, the New Brunswick government’s investment and involvement in the hospital system had increased substantially to the point where health spending was no longer the "minor budgetary item" of the past.114

36 Increases in federal and provincial hospital spending could not have come at a more appropriate moment from the vantage point of the Moncton Hospital. From 1941 to 1953 the number of patients admitted to the hospital increased by 77 per cent while the annual number of hospital days required to treat these patients grew by 44.5 per cent. This compared with an even more explosive growth pattern at Hôtel-Dieu where, over a slightly longer period, the number of patients admitted had increased by 275 per cent from 1938 to 1953 and the annual total of hospital days had jumped by 177 per cent.115 This sister institution’s growth diminished the pressure on the Moncton Hospital as did, to a much lesser extent, the July 1946 opening of the 22-bed Sackville Hospital, in the eastern end of Westmorland County.116 Nevertheless, increased patient numbers in the early 1940s forced constant adjustments to meet overcrowded conditions and encouraged the widely shared assumption that hospital facilities must be expanded considerably once the war ended. At Moncton Hospital, Alena MacMaster reported 100 per cent occupancy of its rated capacity of 125 beds in 1943, despite measures she had taken a year earlier to discharge maternity patients at the end of a week’s stay and to discourage admission of chronic and "rest-cure" types who might be handled at home. In 1944, as a temporary solution, the Moncton Hospital raised its bed-capacity to 150 by converting three front and two rear sun porches into wards, but the space inadequacies remained.117

37 As the war drew to a close, the hospital board commissioned a study of the institution’s needs by A.J. Swanson, superintendent of the Toronto Western Hospital. He strongly endorsed the need for hospital expansion, suggesting that an increase in the demand for services was about to be matched by an increase in government funds. Almost "a million young men and women will be returning to civil[ian] life in the not too distant future", he pointed out, and "they will know that it is a good thing for the State to take care of that highly important welfare measure".118 Once the report was digested, there was agreement that hospital expansion was necessary, but an imbroglio of legendary proportions broke out in 1947 over whether it should be a limited on-site expansion or a new hospital on a new site. Favouring the former option was a core of veteran board members including board chairman Ambrose Wheeler. Calls for a brand new and expanded hospital on a new site came from Moncton city council, a number of board members, the hospital’s staff of physicians and the newly-formed Moncton Taxpayers’ Association. The public donnybrook only ended with the election in April 1947 of a new mayor, J. Edward Murphy, who was committed to the new hospital option. Moncton city council then, under a revised Hospital Act, appointed an entirely new hospital board of 11 members.119 Since 1917 Moncton had been represented by three members of city council on the independent 25-member hospital board. Under the changed legislation, the city assumed total control over the hospital board. Major municipal responsibility for hospital finances was now matched by municipal control over the governance of the institution.

38 Newly appointed hospital board chairman Leonard Lockhart’s hope that construction of a new hospital should be "started in the early summer of 1948 at the latest" soon disappeared.120 Using the argument that Westmorland County patients were roughly one-third of the hospital’s patrons while Albert County residents numbered about one-tenth of the clientele, he plunged into lobbying the neighbouring county councils to win their support for the new hospital project. It was an eye-opening and, at times, disappointing experience for Lockhart. Negotiations would drag out over a year with Albert County approached on two different occasions and responding each time by "politely and promptly" refusing to provide the ten per cent of the funding support requested.121 Westmorland County council proved equally difficult causing Lockhart to comment privately that "I was up to my ears in the rottenest and the dirtiest kind of politics that anyone could ever get mixed up into". County councils in general, he observed, "are not in favour of spending money". They were composed, he believed, "for the most part of farmers, the majority of them being good decent chaps but their one ambition in life is to get everything they can without paying for it". In the final analysis, Lockhart believed, Westmorland County surrendered only when, for not co-operating, the hospital imposed a $2.00 per day surcharge on every Albert County patient and Westmorland sensed it was next in line for such treatment.122

39 Fortunately for the hospital cause, the rather blunt chairman of the hospital board was more than balanced in the negotiations by the politically astute mayor of Moncton. J. Edward Murphy took over negotiations with Westmorland while his own city council approved a total commitment of $1.5 million in hospital debentures.123 Acceptance of a gift from Donald A. MacBeath as the site of the new hospital, over ten acres in what was described as the "Mountain View Sub-division", was formally recommended to the Moncton city council in the spring of 1948.124 By that time as well, with the requirement that county representatives be added to the hospital board, Westmorland County council came on side. It sought and received the New Brunswick legislature’s approval for its own guarantee of up to $850,000 in debentures.125 The final piece in the funding puzzle fell in place when the federal health grant for construction became effective on 1 April 1948, clearing the way for federal-provincial shared-cost funding to make up the difference between the hospital’s total cost and the city/county funding.126

40 At long last, in the late fall of 1950, hospital board chairman Lockhart was able to report that architectural plans had been considered by bidding contractors and tendering had been completed.127 Total cost of a hospital with a capacity of 224 adult beds and 53 bassinets was estimated at around $2.8 million. The federal and provincial governments contributed equally, for a total of just above $470,000. The balance of the cost was to be assumed two-thirds by Moncton (just under $1.6 million) and one-third by Westmorland County (roughly $787,000). One point that Lockhart had underlined on several occasions was that the city and county guarantees of hospital debentures meant a substantial on-going financial commitment on the part of these local-level governments. As he put it, "It is clearly understood that both the City of Moncton and the County of Westmorland will have to pay the interest as well as provide funds for the sinking fund to cover Moncton Hospital Bonds".128 There was no promise or pretense, as there had been when the Moncton Hospital first issued debentures in the 1920s, that it could meet out of its own revenues the annual bond interest charges (which could be as high as five per cent but were actually three per cent) and the three per cent annual cost of the sinking fund. The point was not lost on Mayor Murphy who, early on in these funding arrangements, expressed his hope that this burden on local governments in the near future would be a responsibility shouldered elsewhere. It was his expectation that a "National Health Scheme" would eventually take over "all hospitals and the responsibility shift[ed] from the Municipal to a superior government".129

41 Responsibility for construction costs of hospitals, as well as new equipment, now had been assumed by government, with the municipal and county levels sharing a heavier burden than their provincial and federal counterparts. As per diem operating costs wildly escalated after the Second World War,130 governments moved to increase their support. The increased per diem grants of the New Brunswick government were more than matched in January 1949 by a $1.00 per day grant from Westmorland County and Moncton for each of their residents admitted as patients to the Moncton Hospital.131 For the most part, patient rate charge increases were delayed by the war but the post-war years brought substantial increases. Already at the ward level in 1940 the per diem payment required from Westmorland and Albert County patients increased from $2.00 to $3.00, while Moncton patients were still expected to pay $1.50 per day.132 Other increases were postponed, but from 1945 to 1953, for patients at all levels, there were three increases of 50 cents per day as well as one of $1.00 per day.133 Also implemented were increased charges for other services including operating room, outpatient and ambulance fees. Budgets somehow were balanced, except for a few exceptional years such as during the 1953 move to the new hospital, as the Moncton Hospital grew from an institution with annual operating expenses of about $150,000 in 1940 to one with operating expenditures amounting to nearly $820,000 in 1953.134

42 As per diem patient costs soared from $4.74 in 1945 to $16.00 in 1953,135 the increased costs and charges were rationalized at the national and local levels in the same ways. Leonard Lockhart argued that the Moncton rates were "equally as high" as rates at other New Brunswick hospitals.136 Speaking for the New Brunswick section of the Maritime Hospital Association, Donald F.W. Porter explained that the "dramatic increase" in per diem cost, for the most part, was because of factors at work across Canada. As he outlined the situation, "The increases in our costs are caused chiefly by improvement in existing services, addition of new services, higher wages, increase in total staff, the Provincial Social Service and Educational Tax and, in certain hospitals, increase in Bond interest and depreciation".137 Hospitals congratulated themselves on the increased revenue extracted from patients, which was ascribed to the "increasing general level of prosperity" and, more importantly, "the phenomenal growth of plans for the prepayment of hospital expense of which Blue Cross is a notable example".138

43 Any possibility of deciphering the precise amounts which hospital and medical insurance schemes, as well as increased government support, contributed to the hospital’s increased revenue is unfortunately, as a result of changes in accounting practice over the years, buried in the Moncton Hospital year-end reports. While certain government grants, and Blue Cross payments on occasion, were specifically listed, other government programme support and voluntary insurance payments were more frequently simply rolled into the revenues from private, semi-private or ward patients. It was estimated, however, that by 1954 New Brunswick hospitals "receive revenues up to 65% of their total income from voluntary insurance schemes, the outstanding example of course being our Maritime Blue Cross".139 If the paying uninsured are added to this percentage, patient payments at the Moncton Hospital were probably in the 75 to 85 per cent range, an increase from the roughly 62 per cent patient payments contributed to hospital revenue in 1939, when the figures were clearly presented in the hospital’s annual report.140 What can be more readily tracked, and compared with the Ontario situation, are the basic government grants (provincial, municipal and county) as a percentage of the hospital’s total revenue. In Ontario, from 1940 to 1950, it was estimated that while patient payments (including insurance payments) increased from 66 to 76 per cent of total hospital revenue, payments from municipalities and the provincial government had actually decreased from 26 to 21 per cent of total hospital revenue.141 The Ontario provincial and municipal contribution continued to decline, falling just below 19 per cent in 1954.142 In the case of the Moncton Hospital, while the years after 1945 brought a substantial increase in government funding for the hospital’s operating expenses, the percentage government contribution to total hospital income declined even more substantially than in Ontario. Whereas in 1939 grants from all levels of government amounted to more than 26 per cent of total hospital income, by 1945 this had declined to just 13 per cent and by 1953 to nearly 12 per cent.143 A substantial gap remained between government support of hospitals in Ontario and government support in New Brunswick even at a time of allegedly buoyant government revenues.144

44 In January 1934 an ever-optimistic G. Harvey Agnew observed that when "one considers the origins of our hospital system, its early dependency upon charity and private philanthropy, with no thought of state support, we realize how far we have gone in the interval". Canada lacked the philanthropic resources available elsewhere, he continued, so without "municipal and state support our hospital system could never have attained its present efficiency".145 The real picture was actually somewhat murkier and greyer. In the case of the Moncton Hospital, limited government support was available from the outset but, at all levels of government, a reluctance to assume major funding responsibility was also apparent. Consequently, a reliance upon paying patients quickly emerged and became even more pronounced with the creation and growth of private hospital insurance schemes. Almost 20 years after Agnew’s pronouncement, the funding situation of hospitals remained in flux. While the costs of buildings and equipment had been assumed by government, for the most part at the local level, there remained major funding problems. Although an enthusiastic booster of the hospital cause, and of the need for the communities served to provide financial support, Leonard Lockhart’s candid assessment was that "It is most unfortunate that communities of indifferent assets have to mortgage their futures to construct new hospitals".146 The mayor of Moncton who appointed Lockhart to the Moncton Hospital board and supported his new hospital dream had the same sort of reservation about the municipal capacity, or incapacity, to bear such a burden.147 More precisely analyzing continuing hospital problems in 1953, the executive director of the Moncton Hospital, Donald F.W. Porter, argued that under "the best of circumstances" public hospital financing remained largely unsystematic and unpredictable. He maintained that "Various individual hospitals and various communities have their own approach to attempting to place on some more reasonable basis the financing of the construction, equipping and operation of our institutions". In the Moncton case, its "favourable financial operating position" was due to "a high percentage occupancy" rate which might fall in the future. To offset this possibility, he urged that a "reasonable solution to this difficult problem would appear to lie in the community making a direct money grant on a planned basis to provide for its citizens that margin of ‘safety’ to which they are entitled".148

45 That Porter directed his message at more than the local community became clear over the next several years as he spearheaded the campaign for more provincial funding and an overall funding plan. As chairman of the New Brunswick Section of the Maritime Hospital Association, in the summer of 1954 he urged a doubling to $1.00 per day of the provincial patient grant. This increase would at least provide a "slight breathing spell [until] a more rational method of financing the operation of our hospitals can be provided in our province".149 When no response was received, Porter inquired about the fate of the association’s request and explained the crisis that was at hand. Hospitals had to submit any rate increases to the Maritime Blue Cross Association and their proposed increases had been rejected by that organization. New Brunswick’s hospitals had been informed "that the premiums to the public could not be raised beyond their present level" and further hospital rate increases would require a substantial premium increase.150 Apparently, the potential private, semi-private and ward patients, although the majority were covered by private hospital insurance, could only be pushed so far as a source of revenue. The time was rapidly approaching when the "Patients of Moderate Means"151 would prevail upon governments to deliver an equitable approach to hospital patient fees through public and universal hospital insurance coverage.

46 Hospital histories tend to focus on grand opening ceremonies and the ribbon-cutting celebrations as new wings or buildings were added. Yet behind these events were the evolving funding patterns which made such space and service extensions possible. Funding was basic to hospital establishment and expansion yet it remains little examined or understood. A comprehension of hospital finances can best be achieved by an intertwined overview of local, provincial and federal policies. Employing at the same time the sometimes limited documentation within one hospital, and within the communities it served, provides a better understanding of how the changing demand for hospital services meshed with changing funding to achieve substantial growth in hospitals during the period from 1898 to 1953. Solutions to hospital capital and operating cost problems were only gradually grasped and aimed at as the Moncton Hospital’s funding predicament unfolded. The response of county, municipal, provincial and, to some extent, federal governments revealed the influence of usage patterns and public pressures on their willingness to act. In the 1920s it was clear that seeking private donations for substantial capital costs no longer worked satisfactorily. Guaranteeing debentures was the new answer. In the Depression, however, at least in Moncton, assuming rather than just guaranteeing bond interest and sinking fund requirements was necessary, and city council assumed this burden. As county usage increased in the 1940s, particularly that of Westmorland County, the adjoining counties had to be brought onside to meet the post-war needs of the Moncton Hospital. One responded, another did not. Meanwhile the French-speaking, Roman Catholic constituency, in Kent and Westmorland counties as well as in Moncton, largely redirected its focus to its own Hôtel-Dieu hospital. Across Canada, patient willingness to pay, whether directly or through a third-party arrangement, was consistently crucial through the entire period under consideration. Reluctance to meet rising rates had strongly manifested itself in the difficult Depression years, but another consumer revolt appeared on the horizon in the prosperous 1950s. Examination of these funding patterns reveals that in July 1953 the Moncton Transcript’s acclaim of "A Great Building Achievement", the opening of a new 225-bed, $3 million Moncton Hospital,152 was a report on the completion of a difficult journey as well as an indication of just another step in the continuing trek towards a solution to a perennial hospital funding problem which persists yet today.

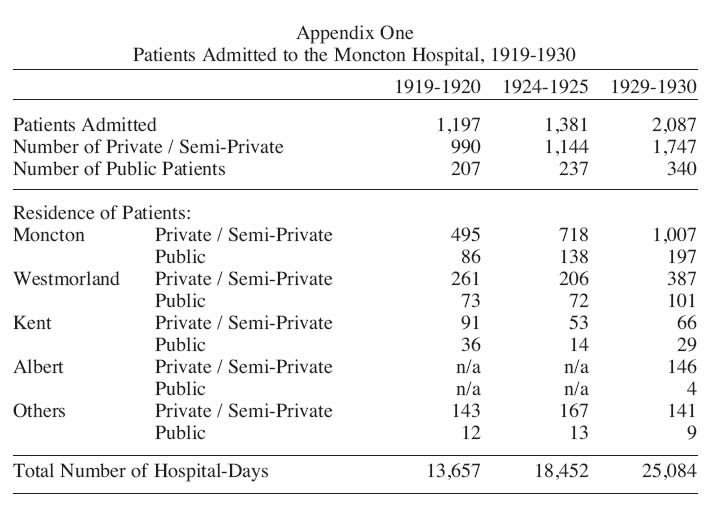

Appendix One : Patients Admitted to the Moncton Hospital, 1919-1930

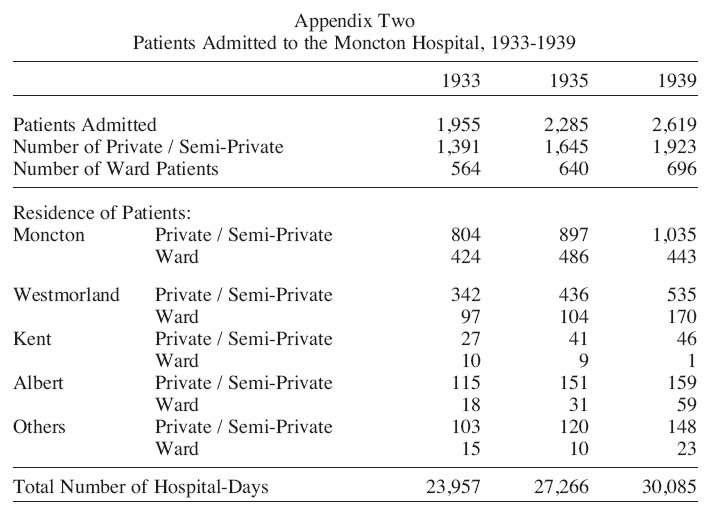

Appendix Two : Patients Admitted to the Moncton Hospital, 1933-1939

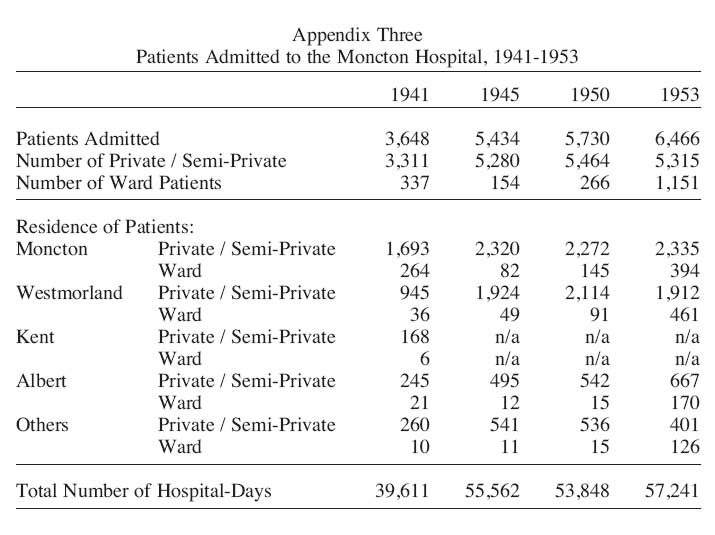

Appendix Three : Patients Admitted to the Moncton Hospital, 1941-1953

Notes