The Riddle of Peggy Mountain:

Regulation of Irish Women’s Sexuality on the Southern Avalon, 1750-1860

Willeen KeoughMemorial University of Newfoundland

1 A STRIKING SCENE FROM THE LIFE of an Irish-Newfoundland woman, Peggy Mountain, emerges in the court records of the southern Avalon and the diary of a local magistrate. In early December 1834, Peggy brought her husband, Michael, before the local magistrates at Ferryland for desertion. She was pregnant and the court ordered that Michael support Peggy and the expected baby during the winter; arrangements would be made with a Patrick Welsh to take her into his home at Michael’s expense. Michael initially indicated his willingness to comply "as well as his ability would allow", but the very next day, he reneged on his promise "by order of [Catholic parish priest] Father [Timothy] Browne". Michael held his ground, even when the magistrates ordered that he be put in jail for contempt and kept on bread and water for a month. Meanwhile, Peggy was temporarily placed at a local public house, but Father Browne, "under threat of the highest nature he could inflict", ordered her removed and, as there was no other accommodation available, the justices housed her in the local jail. Magistrate Robert Carter, Jr., was taken aback by the activities of Father Browne and wrote in his diary: "The Priest is inveterate against a poor unfortunate female under his displeasure and against whom he appears to direct his greatest malice and enmity. . . . How such conduct will end let time decide". Matters came to a head rather quickly. Peggy was very ill and the jailer reported that there were no coals for heating her cell. The priest did not relent and continued to speak out against Peggy in the chapel and wrote an open letter against her that was read publicly at the jailhouse. In the meantime, the local magistrates arranged for a Mrs. Cahill to attend Peggy in the jail. Peggy finally gave birth to a daughter on a night so cold that the ink froze in Carter’s office and the bread froze in his storeroom. The child survived only a few hours. Peggy was then moved to Mrs. Cahill’s house, but again, the priest ordered that she be removed. Finally, magistrate Carter himself took her in. Several days later, Peggy left for St. John’s in the Water Lily and slipped quietly out of the annals of the southern Avalon.1

2 This episode raises many questions. Why was the priest so angry at Peggy? Did he blame her for the breakdown of the marriage? Did he suspect that the coming child was not her husband’s? What threat did he perceive in Peggy’s continuing presence in the community? Although the historical record does not provide the specific reason for the shaming and ostracization of Peggy Mountain, it seems that Father Browne’s anxiety over "aberrant" female sexuality was central to the issue. Especially intriguing is the sharp contrast between the responses of the local magistrates and the priest to Peggy Mountain’s circumstances, for they represent two important mechanisms for patrolling the boundaries of female sexuality – the legal system and formal religion.2

3 Feminist scholarship has argued that an important indicator of patriarchal domination is the degree to which a society seeks to regulate women’s bodies in terms of marriage, sexuality and reproduction.3 As Newfoundland was a British fishing station/colony in the period under study, hegemonic discourses on female sexuality in contemporary Britain provide context for the discussion as the extent of their infiltration into the local context is tested. By the 18th century, the British legal tradition was a patriarchal regime that relegated women’s bodies to the control of fathers or husbands. Concerns about patrilineal inheritance and the legitimacy of heirs lent particular urgency to the protection of the chastity value of wives and daughters. At the same time, Enlightenment thought was challenging the association of sinfulness with sexuality that had been the legacy of 17th-century Puritanism. Yet men and women did not have equal access to the sexual freedom of the age. Uncontrolled female sexuality was seen as a threat, not only to property and legitimacy, but also to the very foundation of the social order itself. Female sexuality was, therefore, channeled into marriage and motherhood, while the division between public (rational, active, individualist, masculine) and private (emotional, passive, dependent, feminine) domains was underscored.

4 These discourses grew within the context of late-18th- and early-19th-century evangelicalism as it shaped middle-class ideals of female domesticity, fragility, passivity and dependence. Female sexuality was further constrained as middle-class ideology fashioned a dichotomized construction of woman as either frail, asexual vessel, embodied in the respectable wife and mother, or temptress Eve, embodied in the prostitute. Separate sphere ideology intensified. Women who occupied "public" spaces or who demonstrated a capacity for social or economic independence, even physical hardiness, were increasingly seen as deviant. Overt female sexuality was particularly problematic for it "disturbed the public/private division of space along gender lines so essential to the male spectator’s mental mapping of the civic order".4 As the 19th century unfolded, legal, medical and scientific discourses continued to embellish the construction of woman as "the unruly body", consumed by her "sex", problematic by her very biological nature and requiring increased monitoring and regulation.

5 These discourses on female sexuality and respectability were infiltrating 18th- and 19th-century Newfoundland through its British legal regime and an emerging local middle class of administrators, churchmen and merchants, many of whom maintained strong ties with Britain.5 On the island, gender ideology was tempered by the exigencies of colonial policy as it was articulated by central authorities in St. John’s. And this ideology also assumed ethnic undertones as the Irish population in Newfoundland increased. From the mid 1700s onward, as Irish servants increasingly replaced English labour in the fishery and as an Irish-Newfoundland trade in passengers and provisions expanded, Irish migration to the island swelled.6

6 British authorities in Newfoundland watched the growing number of Irish migrants with levels of concern ranging from wariness to near hysteria. Official correspondence and proclamations for the period articulated several common themes about the Irish population. The authorities claimed that the Irish were a "disaffected", "treacherous" people who would prove to be Britain’s "greatest Enemy" in times of war. They bred prodigiously and were already overtaking the local English-Protestant population in numbers. Officials claimed these "Wicked & Idle People", who were prone to excessive drink and disorderly behaviour, terrorized "His Majesty’s loyal Protestant subjects" and were responsible for most of the crime that occurred over the winter. Thus, a battery of orders and regulations attempted to limit the numbers of Irish remaining on the island after the fishing season was over.7

7 Three important contextual elements framed the perspective of visiting British authorities towards the Irish in Newfoundland. First, their attitudes reflected contemporary English perceptions of difference between the Anglo-Saxon and Gaelic "races". Second, most of the Irish in Newfoundland were Catholics, and were therefore subject to a penal regime similar to that which existed in Ireland and Great Britain at the time. Third, Britain was ambivalent about permanent settlement in Newfoundland until the early 1800s. For centuries, British authorities had viewed Newfoundland as a fishing station rather than a colony, and had struggled to promote the migratory fishery, at the expense of a resident sector, in order to preserve the hub of the industry in the West of England and to maintain Britain’s nursery for seamen. Nonetheless, British authorities in Newfoundland expressed more concern about the Irish remaining on the island than the English, and official discourse constructed "Irishness" as inherently feckless, intemperate, disloyal and unruly. The Irish were a "problem" group that required constant regulation and surveillance.

8 Part of this official discourse focused on an image of the Irish woman immigrant as a vagrant and a whore. This fits within a broader context in which British authorities discouraged the presence of all women in Newfoundland. The very characteristics that made women essential to colonial ventures on the mainland – their stabilizing effect, their essential role in forming a permanent population – posed a threat to British enterprise in Newfoundland, as a resident fishery would weaken the migratory sector. As Capt. Francis Wheler, a naval officer in Newfoundland, reassured the home government in 1684: "Soe longe as there comes noe women they are not fixed".8 While official policy discouraged women migrants in general, authorities in St. John’s highlighted the undesirability of Irish women in particular. Official documents of the period portray Irish women immigrants as degenerate, unproductive and dangerous to the social and moral order. Central authorities argued that these women caused "much disorder and Disturbance against the Peace" and inevitably became a charge on the more respectable inhabitants of the island. Many "devious", single Irish women, they said, arrived in Newfoundland pregnant and disguised their condition until they had hired themselves out to unsuspecting employers. Running through the records was a subtext that once Irish women were permitted to remain, all the elements for reproducing this undesirable ethnic group would be in place. The Irish woman immigrant, then, was a particular "problem" for local authorities, requiring special regulation of her own. In particular, the single Irish female servant required monitoring, for her social and economic independence from a patriarchal family context and her potential sexual agency flouted a growing middle-class feminine ideal that embodied domesticity, economic dependence and sexual passivity. Still, early governors were not without solutions to the "problem". In 1764, Hugh Palliser ordered that no Irish women be landed in Newfoundland without their providing security that they were well behaved and would not become a charge on the inhabitants. Thirteen years later, John Montague ordered that the transportation of Irish women servants to Newfoundland cease altogether.9

9 Despite these characterizations and orders, employers continued to hire male and female Irish servants for service in the fishery and domestic work, particularly in Conception Bay, St. John’s and on the southern Avalon. The Irish presence increased and took on more permanence as the migratory fishery, plagued by almost continuous years of warfare, declined and the resident fishery expanded, in both proportionate and absolute terms. Along the southern Avalon, Irish men and women formed fishing households and hired servants of their own. Away from the watchful eyes of visiting governors, an Irish planter society took root in most harbours.10 It was reinforced through increasing Irish migration through the close of the 18th century and into the early decades of the 19th century.

10 How did hegemonic constructions of womanhood, and particularly Irish womanhood, play out on the southern Avalon, where community formation was still in its early stages among an essentially plebeian Irish population and where gender relations were still contested terrain? How were they interpreted by the local middle class and received within the essentially plebeian Irish community of the area? On the southern Avalon, the plebeian community was comprised primarily of fishing servants, washerwomen, seamstresses, midwives, artisans, small-scale boatkeepers and planters, and by the 19th century, numerous "independent" fishing families (in as much as they could be independent from their merchant suppliers). The plebeian community shared a common consciousness and exerted political pressure on occasion – either in the form of the "mob" in direct collective actions or as the menacing presence behind anonymous actions and threats. They were not a working class for they lacked class consciousness. But they did have a distinct and vigorous plebeian culture, with its own rituals, its own patterns of work and leisure, and its own world view. Their social superiors were the local merchants or merchants’ agents, vessel owners and masters, Anglican clergy and more substantial boatkeepers and planters, who were part of an emerging middle class in Newfoundland in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. They functioned as quasi-patricians with their control of employment opportunities, relief, supply and credit, and administrative and magisterial functions. Although tied to the plebs through interdependence in the fishery, this group maintained social distance through religious affiliation and exclusive patterns of socializing and marriage.11

11 The ways that Irish womanhood was constructed by these distinct yet interdependent groups may provide a key to unlocking the riddle of Peggy Mountain. In Britain, the working class adopted and refashioned middle-class feminine ideals during the 19th century to support their own bid for respectability in the Chartist movement and to satisfy the male-centred agenda of trade unionism. Furthermore, the British middle class encouraged this development of a working-class respectability – one that imitated middle-class ideals while maintaining sufficient difference to preserve class boundaries. In rural Britain and Ireland, as well, women were impelled into domesticity by a powerful combination of proscriptive ideology and the marginalization and devaluation of women’s labour in agriculture and cottage industries. But did similar processes occur on the southern Avalon? Or were there tensions between hegemonic rhetoric and the realities of Irish-Newfoundland women’s lives that delayed the intrusion of such feminine ideals into plebeian culture? And did a lack of consistency between the attitudes of secular and religious authorities in the area towards Irish female respectability further attenuate the encroachment?

12 In order to answer such questions, it is first necessary to examine Irish women within the context of the plebeian culture of the southern Avalon. Within this population, women acquired significant status and authority in family and community as they assumed vital social and economic roles during immigration and early settlement.12

13 With increasing numbers of women moving to the southern Avalon and elsewhere in Newfoundland, the fears of the British government were confirmed. Once women came, the population became fixed. Given the transient nature of employment in the Newfoundland fishery, male fishing servants commonly found employment in different areas from year to year, moving in and out of districts, and between harbours within a district, as work opportunities shifted. In time, the presence of women tied them to particular communities. On the southern Avalon, some Irish fishermen were joined by wives or fiancées from the home country or married women from the small, established English planter group. Increasingly, however, they found wives among single or widowed Irish immigrant women and, by the turn of the century, among an expanding group of local first- and second-generation Irish-Newfoundland women. Matrilineal bridges often factored in the clustering of families in particular coves and harbours, while matrilocal/uxorilocal residence patterns played an intrinsic role in community formation, as many couples established themselves on land already occupied by the wife or apportioned from or adjacent to the family property of the wife.

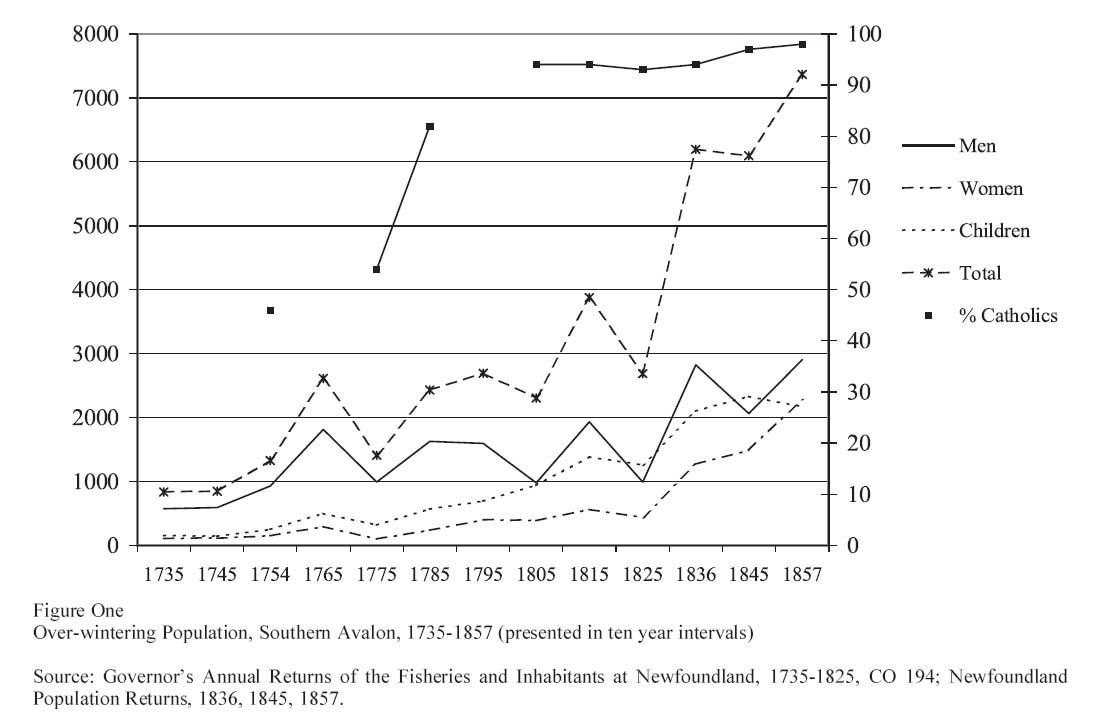

14 The Irish did not establish separate communities on the southern Avalon but intermingled with English planter families and servants already in the area. The result was the almost total assimilation of the old English planter society into the Irish-Catholic ethnic group. In the late 17th century, there had been a strong English-Protestant planter presence on the shore; a century later, the population was almost totally Catholic (Figure One).13 This shift corresponded with the influx of Irish into the area, but it was not just the net result of Irish in-migration and English out-migration. Parish records and anecdotal evidence provided by Catholic and Anglican clergy indicate that intermarriage, conversion and assimilation worked in conjunction with Irish immigration to produce this change. Indeed, a sense of fatalism pervaded the records of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel as the Anglican clergy bemoaned the loss of "the multitude into the strange pastures" of Catholicism.14 The Catholic clergy, by contrast, noted with mounting satisfaction the numbers of Protestants converting from "the flock of the stranger" to "the bosom of Christianity".15 The English Protestants were not moving out; they were merely shifting religious allegiances. This was particularly true within plebeian culture, where families with English surnames such as Glynn, Williams, Yard, Carew, Maddox and Martin were steadily incorporated into a growing and maturing Irish-Catholic population. Irish women played a vital part in the process, as potential spouses or cohabiting partners of not only incoming Irish-Catholic migrants but also English-Protestant men. By the turn of the 19th century, much of the population of the southern Avalon, particularly within plebeian culture, was Irish or partly Irish. A beleaguered English-Protestant group, composed mostly of middle-class mercantile and administrative families, retreated and turned inwards on itself, occasionally recruiting marriage partners from St. John’s or England to maintain its homogeneity.16

Figure One : Over-wintering Population, Southern Avalon, 1735-1857 (presented in ten year intervals)

Display large image of Figure 1

15 Plebeian women in the study area were an intrinsic part of the economic life of their fledgling communities. They played a vital role in subsistence production for their households. In addition, women ran public houses, looked after boarders, provided nursing services and took in paid washing and sewing – mostly catering to single, male, fishing servants. Women were "shipped" as servants to merchant, administrative and planter families, and while the majority were recruited as domestic servants, a smaller number worked as fishing servants, heading, splitting, salting and drying fish as part of shore crews.17 Regardless of the type of service, and whether "shipped" by oral agreement or written contract known as a "shipping paper", the law looked upon these arrangements as formal contracts and required both servants and employers to fulfill their obligations under the agreements.18 The existence of this system of contractual employment, recognized by law, conjures up an image of the Irish woman servant that was far more purposeful than the impoverished, immoral woman of 18th-century governors’ proclamations.

16 Some women, primarily widows, were fishing employers and operated fishing premises in their own right.19 A greater number ran fishing plantations with their husbands or common-law partners,20 with the responsibility for boarding fishing servants and dieters (winter servants working only for room and board) added to their other household and subsistence duties. And increasingly, plebeian women became shore crews for the family production unit in the fishery, replacing the hired, transient, primarily male servants who had been the backbone of the traditional planter fishery.21 On shore, they performed the crucial work of salting and drying fish, a process that required careful attention and good judgment to ensure the quality of the cure. Along the southern Avalon, the momentum for the shift to the household unit began as early as the 1780s – again, that period when the Irish were arriving in ever increasing numbers.22 The post-war recession that followed the Napoleonic Wars saw the final demise of the older system of waged labour. War-time inflation carried over into post-war wages and provisions but fish prices plummeted. Planters, unable to offset their losses, either went bankrupt or turned increasingly to family labour to meet production needs. With the old planter fishery in its death throes and the resident fishery in crisis, women stepped into the breach and took the place of male fishing servants on the stages and flakes, producing saltfish for market. Their presence at these public sites of economic production and their vital and recognized contribution to the process was an important source of power for these women, even into the 20th century.23 This was terrain worth retaining, and even when fishing families hired servant girls, it was not to replace the women of the house in outdoor work, but to assume household tasks in order to "free" their mistresses to contribute to more important family enterprises.

17 Further evidence of women’s participation in the public, economic sphere is provided by mercantile records, which suggest that women were a vital part of the exchange economy of the area.24 Significant numbers performed some independent form of economic activity and held accounts in their own names as femes sole, regardless of marital status.25 Some were heads of households that produced saltfish and oil for market. Many more sold pigs, fowl, eggs and oakum. They earned wages haying, tending gardens or making fish on merchants’ flakes. They also did washing and sewing for local single fishing servants and middle-class customers. Many combined their paid services in a package of economic coping strategies that helped families make ends meet. Women’s work for a mercantile firm was credited to their accounts. Work for other people in the community was "contra’d" against the accounts of their customers; in other words, a balancing entry was made in the merchant’s ledger, giving the woman credit and her customer a debit entry. Some women had credit balances or received a small amount of cash when they "settled up" in the fall. Some even had their profits applied towards the debts of male relatives. Many others had debit balances, but so did most men in the community – a chronic symptom of the truck system that underpinned the resident fishery. Merchants carried these debts forward and rarely wrote them off, suggesting confidence in the women’s earning abilities. Of course, men’s names headed the accounts more frequently than women’s, for merchants would have been mindful of the repercussions of coverture26 in relation to debt, but legal principle and accounting practice masked the full extent of women’s participation in the exchange economy. Women’s labour in family work units contributed to the production of fish and oil credited to accounts of fathers or husbands. Women used many of the goods appearing under the names of male household heads for household production, expending labour and producing goods that were assigned no market value and therefore were not included in formal business ledgers of the day. Furthermore, merchant books did not record female networks of informal trade – the exchange of eggs for butter, for example, or milk for wool – which helped women keep their families clothed and fed.27

18 Religion in both orthodox and informal observance was another important source of informal female power within the Irish community of the southern Avalon, particularly before the encroachment of ultramontanism and the devotional revolution of the mid to late 19th century. There is evidence that Catholic women in Newfoundland performed religious rites and assumed religious authority in the century before these intrusions. Bishop Michael Fleming complained to his superiors that prior to the establishment of Catholic missions in the late 18th century: "The holy Sacrament of Matrimony, debased into a sort of ‘civil contract’, was administered by captains of boats, by police, by magistrates and frequently by women. The Sacrament of Baptism was equally profaned".28 Fleming was also dismayed that midwives had assumed the authority to dispense with church fasts for pregnant women. Dean Cleary’s "Notebook" refers to women at St. Mary’s taking "the sacred fire from the altar to burn a house" – perhaps a rite of exorcism of some sort, but certainly an act with ritualistic overtones.29 According to the oral tradition, women primarily kept the faith alive before the priests’ arrival by observing Catholic rituals and teaching children their prayers. Indeed, as one informant stated and most others implied: "If it was left to the men, sure there’d be no religion at all".30 These references suggest that women played an important custodial role in relation to the Catholic religion in the period of early settlement. Furthermore, female figures were prominent in the Irish-Catholic hagiolatry of the area. To this day, the Virgin Mary, St. Brigid and "Good St. Anne" are a powerful triumvirate. On the southern Avalon, as in Ireland, there was an alternative pre-Christian religious system operating in tandem with, and sometimes overlapping, formal Catholic practice. This melange of ancient beliefs and customary practices made up a very real part of the mental landscape of the Irish community, and women were important navigators of this terrain. Women made and blessed the bread that had special powers to keep fairies from stealing their children; the same bread could help people who were "fairy-struck" – lost in the woods or back-meadows – find their way home. Women anointed their homes with holy water and blessed candle wax to protect their families from dangers such as thunder and lightning. Women read tea leaves and told fortunes. They ritually washed and dressed the dead, "sat up" with corpses at wakes to guard their spirits overnight, smoked the "God be merciful" pipes,31 and keened at gravesides to mourn the departed and mark their passage into the next life. Certain women had special healing powers – the ability to stop blood with a prayer, for example. A widow’s curse, by contrast, had the power to do great harm. The bibe, the equivalent of the Irish banshee, was a female figure, as was the "old hag" who gave many a poor soul a sleepless night.32 And places like Mrs. Denine’s Hill, Peggy’s Hollow and Old Woman’s Pond (named for the women who had died there) had magical qualities that could cause horses to stop in their tracks and grown men to lose their way.33 Thus, in both formal and informal practice, Irish women acted as mediators of the natural and supernatural worlds and, by extension, played a vital role in reinforcing the identity of the ethno-religious group in the area.

19 Court records for the area reveal that plebeian women also featured in numerous collective actions and individual interventions to protect personal, family and community interests during the period – deploying power through verbal threats and physical confrontations that did not fit middle-class ideals of femininity.34 The women of the Berrigan family, for instance, were an important force in the family’s struggle to hold fast to their fishing "room"35 on the south side of Renews harbour in the late 1830s and early 1840s. John Saunders, a local merchant and JP, made repeated attempts to take possession of their premises (likely for rent arrears or non-payment of debt), but his efforts met with persistent resistance from the family, including the Berrigan women. In 1838 and 1842, family members were charged with violently assaulting two different deputy sheriffs as the officers tried to remove them from the property. Finally, in 1843, the Berrigans were found guilty of intimidating and assaulting John Saunders, himself, as he tried to take possession of the fishing room. There were variations in terms of the family members involved in each case, but Bridget and Alice (daughters, sisters, or relatives by marriage) were involved in two of the three incidents, while the family matriarch, Anastatia, was present every time.36 These women’s participation was not unusual within the historical context of this fishing-based economy. As essential members of their household production unit, the Berrigan women were defending a family enterprise in which they felt they had an equal stake, using compelling means to protect their source of livelihood in the face of perceived injustice at the hands of their supplying merchant and the formal legal system.

20 Indeed, plebeian women on the southern Avalon were not reluctant to use physical violence in sorting out their daily affairs. In assault cases brought before the southern Avalon courts during the period, women were aggressors almost as often as they were victims (by a proportion of 86:100). Of the 111 complaints involving women during the period, 50 were laid against male assailants of female victims, but 61 involved female aggressors.37 Furthermore, these women assailants were not particular about the sex of their victims: 32 were women and 28 were men (with child victims in the remaining case). All the female aggressors were of the plebeian community. Most episodes involved the use of threatening language and/or common assault with a variety of motivations, including defence of personal or family reputation, employment disputes over wages or ill-treatment, defence of family business, enforcement of community standards and defence of individual or family property. The physical assertiveness of these women and the court’s matter-of-fact handling of these cases suggest that women’s violence was no more shocking to the community than men’s. Gender relations within the plebeian community were fluid and these women felt they had the right to carve out territory for themselves and their families in the public sphere.38

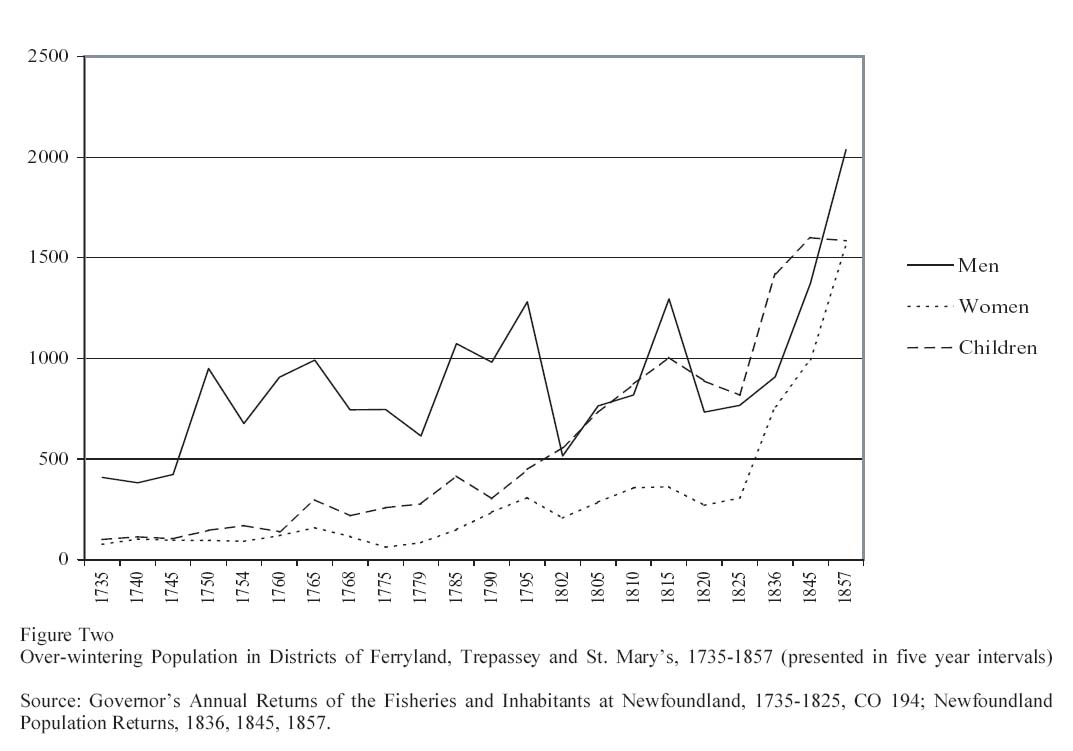

Figure Two : Over-wintering Population in Districts of Ferryland, Trepassey and St. Mary’s, 1735-1857 (presented in five year intervals)

Display large image of Figure 2

21 Of course, there were 50 cases involving plebian women victims of male violence. These ranged from complaints of threatening language and ill treatment to more serious charges of physical and sexual assaults. In feminist scholarship, male violence against women – actual or potential – has been cited as a mechanism of patriarchal control. Yet it is evident that on the southern Avalon, the use of physical violence was not gender-specific; this was not a context characterized primarily by male aggressors and female victims. Clearly too, plebeian women felt that it was their prerogative to take their abusers to court. They perceived themselves as individuals with rights which should be protected by the legal system, and they were not deterred by notions of female respectability and self-sacrifice from asserting their claims to justice in a public forum.

22 Irish plebeian womanhood on the southern Avalon was not engulfed by the constraints of separate sphere ideology or constructions of passivity, fragility and dependence. Nor was it easily channeled into formal marriage – a key site for the control of female sexuality within the English common-law tradition and middle-class ideology. In marriage, a woman was accessible to male sexual needs and could fulfill her destiny as reproducer of the race; yet her sexuality could be safely constrained within the roles of respectable wife and mother. Indeed, a woman’s entire person was subsumed in the identity of her husband within marriage. As feme covert, she could not own property, enter into contracts without her husband’s approval, sue or be sued. And her husband had a regulatory interest in her body and sole rights to her services, both domestic and sexual (the latter, again, reflecting anxiety over the legitimacy of heirs).

23 While formal marriage was institutionalized as the proper means of ordering society, within the predominantly Irish plebeian community of the southern Avalon, informal marriages and common-law relationships were tolerated and seen as legitimate.39 Given the different understanding of gender that had evolved in Gaelic Ireland – one in which traditions of transhumance, communal property and partible inheritance contrasted with English preoccupations with private property and patrilineal inheritance – this is, perhaps, not surprising. Within the Irish tradition, the chastity requirement for wives and daughters was muted, and informal marriages and divorces, illegitimacy and close degrees of consanguineous marriage were tolerated. Irish traditions differed from English norms of sexual behaviour.40

24 In 1789, Father Thomas Ewer, the Catholic priest stationed at the new Catholic mission in Ferryland, complained of the irregularity of marital arrangements in his parish.41 What Ewer was observing were frequent incidents of common-law relationships and informal marriages, separations and divorces in the area, part of a marital regime that kept fairly loose reins on female sexuality and, in effect, provided freedom for a number of women from the repercussions of coverture. It is difficult to determine the extent of such relationships on the southern Avalon, given the lack of parish records, particularly before the 1820s. However, the 1800 nominal census of 166 family groupings in Ferryland district suggests the existence of as many as 33 such relationships (20 per cent of the total), either then or in the recent past.42 References to common-law relationships also appeared occasionally in court hearings and governors’ correspondence.43 Such arrangements were accepted by the local population, especially when children were cared for in stable family relationships and did not become a charge on the community.

25 Irish plebeian women who entered into formal marriages on the southern Avalon were not readily constrained either, given their vital role as co-producers in family economies. In this, they were similar to their counterparts in rural Ireland, or certainly 18th-century rural Ireland, where women gained status from their role as co-producers in a mixed farming and domestic textile economy.44 Within both contexts, married women exercised considerable autonomy in running their households and also had significant influence over matters outside home. While a facade of patriarchal authority was usually maintained in both cultures, male decision-making was frequently directed by women behind the scenes. Clarkson describes this family power structure in Ireland as a "matriarchal management behind a patriarchal exterior".45 The oral tradition on the southern Avalon has a more homespun equivalent: "She made the cannonballs, and he fired them".

26 In general, then, middle-class constructs of female respectability and anxieties about regulating female sexuality did not easily insinuate themselves into Irish plebeian culture on the southern Avalon. Women’s essential role in community formation, powerful position in an alternative belief system, deployment of informal power in community life, and essential roles in subsistence production and the fishery mitigated against the adaptation of middle-class ideologies that did not fit local realities. Furthermore, because the southern Avalon remained a pre-industrial society into the 20th century, plebeian women’s status did not undergo the erosion experienced by their counterparts in the industrializing British Isles. In rural Ireland, the marginalization of women from agricultural work and the collapse of the domestic textile industry and the "potato culture"46 in the early 19th century led to a depreciation of women’s worth, both as producers and reproducers. Similarly, in England, the masculinization of farm labour and dairying and the mechanization and industrialization of cottage industries led to the devaluation of women’s labour.47 On the southern Avalon, however, women’s status as essential co-producers in the fishing economy, as well as reproducers of family work units within that economy, remained intact and forestalled any masculinist project within plebeian culture to circumscribe their lives.

27 If members of the local middle class were going to attempt to introduce feminine ideals into the fishing community, then this was the network of plebeian gender relations with which they must contend. And one of the forums in which they might have made efforts to rein in Irish womanhood on the southern Avalon was the local court system. Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, justice in Newfoundland had been a makeshift affair, dispensed by fishing admirals – the captains of the first fishing vessels to reach every harbour at the start of the fishing season. This system, with a right to appeal decisions to the visiting naval commodore, was given legislative sanction in 1699. In 1729, in grudging acknowledgment of the over-wintering population, the naval governor at Newfoundland was permitted to appoint justices of the peace and surrogates to hear fishery disputes in the absence of fishing admirals and seasonal governors. As the century progressed, the legal regime in Newfoundland expanded to include customs officers (1739) and courts of vice-admiralty (1744), oyer and terminer (1750) and common pleas (1789). In 1791, a court of civil jurisdiction was introduced and its jurisdiction was broadened to include criminal matters the following year. But the face of the law most frequently encountered by the plebian community on the southern Avalon was that of the local, middle-class magistrate. Magistrates were appointed from among the principal merchants and inhabitants of the area and, throughout the study period, they were overwhelmingly members of the mercantile community, although several Anglican clergymen and a resident doctor also sat for brief periods.48

28 Feminist scholarship has argued that within the British legal tradition, the court system – a regime dominated by male legislators, judges, lawyers and juries – was one of the chief mechanisms for regulating female sexuality.49 Women did, however, have varying degrees of agency within this framework, depending on specific historical contexts. On the southern Avalon, plebeian women were a vital part of local court life, as civil litigants, as complainants and defendants in criminal matters, as witnesses and petitioners and as parties in estate matters. Indeed, the courtroom was more often a site of their empowerment than their oppression. Women’s visibility in the court system and their reception by magistrates suggests that the legal milieu, at least at the local level, may not have been as inhospitable as it was in other jurisdictions.50 Court cases dealing directly with issues of female sexuality in the southern Avalon reveal a laissez-faire attitude on the part of local magistrates in monitoring plebeian womanhood.51

29 Seduction law in the 18th and early 19th century fit comfortably with constructions of female sexuality as passive and of women as virtual possessions. This civil action, which was based on the English common-law principle that a master could sue for the loss of a servant’s services due to injury, could be taken only by a woman’s legal guardian (usually, the father). Damages were evaluated in terms of the guardian’s loss of a daughter’s or ward’s domestic services during pregnancy and lying-in, not in terms of her pain and suffering or reduced social and economic expectations.52

30 The seduction action was not uncommon in other jurisdictions. It is intriguing, then, that only one case survives in the court records for the southern Avalon. On 4 October 1827, Catharine Delahunty, a widow, complained that James H. Carter had seduced her daughter, Ellen, and asked for £100 compensation for the loss of Ellen’s services. Ellen appeared at the trial as a witness and told the court that for the past year, Carter had persistently courted her attention, first by offering her work, knitting socks and cutting "sounds"53 on the stage head, and then by suggesting assignations in the woods to cut firewood. The couple had gone on several woodcutting expeditions and, eventually, Ellen had become pregnant. Her mother claimed that Ellen had been unable to carry out her duties from the seventh month of her pregnancy onwards, that her recuperation from childbirth had been slow and that her capacity to work thereafter had been reduced as a result. Ellen’s sister, Catharine Kelly, appeared as a witness for the defence, claiming that she had recently had to warn Ellen against "walking with Robert Brine . . . a married man". Catharine countered with character witness Martin Conway, who swore that he had "never seen Ellen Delahunty conduct herself differently from what well behaved Girls in her situation in life do". The effort by the defendant to present Ellen as an "unchaste" woman would not have disproved Catharine’s suit, as the action was for compensation for loss of household services; however, he may have been hoping to lower the award for "damaged goods". Certainly, the £30 recommended by the jury was far less than the £100 compensation sought by Catharine; but this was still a substantial amount of money, and a significant award for this particular court.54 Indeed, given that seduction suits generally garnered higher awards than paternity suits and given that James Carter was a member of a wealthy, middle-class family in Ferryland, Catharine and Ellen demonstrated a fair degree of legal savvy in proceeding in this manner. Certainly, no local awards under the bastardy law approached £30 during the period.

31 Still, the bastardy action provided another option for pregnant women who wished to make reluctant fathers live up to their paternal responsibilities. Unlike the seduction suit, the bastardy action was taken by the woman herself. On the southern Avalon, bastardy suits were more common than seduction actions, suggesting a degree of female agency in the courts. Still, there were only nine bastardy cases for the period. Women may have had other informal community mechanisms to bring to bear on reluctant fathers, or, perhaps, single mothers on the southern Avalon had social and economic opportunities, such as a reasonable expectation of work, future marriage or family support, that minimized the need for bastardy actions. Still, it is significant that nine women were willing to take public, political action by bringing the alleged fathers of their children to court. By using the court system in this way, these women acted as autonomous legal entities rather than legal dependents.

32 The results of their actions are known in only six of the nine cases. In all six, support for the child was ordered, and in half of these cases, the mothers were also awarded lying-in expenses. In early April 1791, for example, Catherine Oudle (also, Audle), a single woman of Ferryland, appeared before the magistrates and named John Murray, Sr., a fisherman at Ferryland, as the father of her unborn child. When Catharine gave birth to a boy on 22 April, Murray was ordered to pay the following support and expenses:the sum of ten shillings . . . toward the Laying in of the sd. Catherine Audle & ye maintenance of ye sd. Child, to the time of making this Order . . . the sum of two shillings weekly & ever[y] week from this present time for the maintenance of the sd. Child – so long as the Child shall be chargeable to the sd. Harbour . . . [or alternatively] weekly & ever[y] week ye sum of two shillings & sixpence, in Case the sd. Catherine Audle shall not Nurse or take Care of the Child herself.55Similarly, when Manus Butler admitted to fathering Elizabeth Carney’s child, the court was thorough in its support order for £9.19.6, detailing expenses for a midwife’s attendance (£1.1.0), nursing services for a childbed illness suffered by Elizabeth (£2.2.0) and the nursing and clothing of the child from its birth to the court hearing (£6.16.6). In addition, the court ordered 3s.6d. per week continuing maintenance for the child.56

33 There is no indication that either the mother’s character or her sexual history was called into question in any of the cases examined. Furthermore, the mother’s word seemed sufficient to establish paternity, although in three of the nine cases, the fathers also admitted the claim. In four of the cases, the purported fathers had left the district, usually before the claim was made. In one case, more dramatically, a reluctant father, William Walsh, ran from the courtroom and later successfully resisted arrest by brandishing a knife at the two constables dispatched to fetch him back. Walsh was not apprehended, but several of his companions were later fined for helping him escape.57 Indeed, the magistrates took pains to track down absconding fathers or, if unsuccessful, to attach any wages remaining in the hands of employers in the district. Of course, the court was primarily acting to ensure that mother and child not become a charge on the community. But the bastardy law provided women with some access to financial assistance and the opportunity to act as independent agents in the court. Furthermore, local magistrates were receptive to their claims and made reasonable efforts to have fathers acknowledge their responsibilities.58

34 Infanticide and concealment of birth cases were also potential terrain for patrolling female sexuality. The vast majority of defendants in these cases in British and colonial courts shared a similar profile. They tended to be young, unmarried, plebeian or working-class women, especially servants. Most, already caught in difficult socioeconomic circumstances, acted out of fear of the social disgrace and reduced employment prospects that unwed motherhood would bring. Courts were generally reluctant to prosecute and juries were generally reluctant to convict on infanticide charges; the lesser charge of concealment was more commonly employed with success, although even in such cases, the courts were often sensitive to the desperation and limited options that motivated the mothers’ actions.59

35 Remarkably, no cases of infanticide or concealment of birth survive in the court records for the southern Avalon. It is unlikely that the local court would have turned a blind eye to such matters. Given that illegitimacy did not carry a heavy stigma within the Irish plebeian tradition of the southern Avalon in this period, family or community support probably cushioned the hardship of illegitimate births. Single, plebeian mothers may have been in a relatively strong position to survive socially and economically. Furthermore, they had access to the court system to seek financial assistance from reluctant fathers and reason to expect successful results. Thus, the fear of unwed motherhood was, perhaps, not as keenly felt on the southern Avalon as elsewhere.

36 The manifestation of female sexuality which most induced patriarchal anxieties about the moral order was prostitution. More than any other woman, the prostitute, with her blatant sexual agency, flouted middle-class constructions of female passivity and threatened the rationality and self-control that defined middle-class masculinity. Furthermore, by conducting her business in public, she transgressed the careful ordering of separate spheres. Yet, ironically, courts in British jurisdictions often treated prostitutes with a degree of tolerance, seeing them as a necessary social evil; they serviced male lust in ways that were beyond the capacity of "respectable" wives and mothers. Only the most outrageous examples received the full brunt of the legal system.60

37 No evidence of charges against women for prostitution or the catch-all vagrancy survives among the court records of the southern Avalon. On the surface, this seems to suggest that local constables and magistrates were little concerned about women of "ill repute". The court did, however, take action against female complainants who were deemed to be threats to the moral order in two sexual assault cases. In 1773 Mary Keating accused Stephen Kennely of attempting to rape her. He had come into her house, she claimed, and "sat upon the Bed after her husband went out . . . [and] treated her in a barbarous and cruel manner wanting to get his will of her". Kennely would have killed her, Mary claimed, had not one John McGraugh prevented him. Various "principal Inhabitants" of Ferryland testified, however, that the Keating house was a "disorderly house" where they entertained "riotous friends"; the defendant, Kennely, by contrast, was represented as "a man of an Honest Character". Based on these character profiles, the magistrates ordered that Mary and her husband be "turned out of the country".61 The court took similar action against Catharine Power of Renews, a woman notorious for her drunken and promiscuous behaviour, when she complained in 1806 that William Deringwater (also, Drinkwater) had sexually assaulted her in her home. The court, however, was not convinced by the "unsoported solitary deposition" of this "woman of infamous character". Furthermore, a defence witness swore that he had put Catherine to bed intoxicated earlier in the evening and three others testified that Deringwater had been at his own home at the time of the alleged assault. The court acquitted the defendant and ordered that the plaintiff, Catharine, be sent back to Ireland at the first opportunity.62

38 The most intriguing aspect of these two cases is the order for removal of the complainant. Local courts issued sentences of transportation to the home country with some regularity in cases involving property crimes, especially in the 18th and early 19th centuries. However, in terms of breaches of the peace or crimes against the person, magistrates generally ordered deportation only in the most extreme cases of violence or riotous behaviour. The banishment of Mary Keating and Catharine Power suggests that the behaviour of these women of "infamous character" was similarly seen as an extreme threat to the moral and social order. Despite a generally relaxed attitude towards the conduct of plebeian women, the middle-class magistrates of the southern Avalon did set some boundaries for their sexual behaviour.

39 Incidents of rape and other forms of male violence against women are indicators of unequal power relations between men and women. It is notable that only eight cases involving complaints of rape or assault with intent to commit rape survive in the local court records for the period. Of course, such incidents were likely under-reported. However, women’s ability to fend for themselves in physical confrontations may have acted as a deterrent to sexual assault. Of the eight reported cases, three resulted in guilty verdicts and three were dismissed. In another, the defendant was cleared of the rape charge but found guilty of a common assault. Any record of the disposition of the remaining case has not survived. This middling conviction rate might initially suggest an ambivalent attitude towards the crime on the part of the southern Avalon magistrates. In the cases resulting in convictions, however, the magistrates and juries appeared responsive to the women complainants. Corroboration was not essential to proving the charge, for in only one of the three cases – the attempted rape of Mary Jenkins – did the complainant provide a supporting witness. In the Jenkins matter, the main offender absconded and could not be punished, but two of his companions were convicted as accessories and ordered to pay fines (£1 each) and compensation to the victim (£2 each), an unusual resolution of an assault case for this particular court. Even the witness for the complainant, a timid shoemaker who had been present in the house at the time of the attempted rape, was fined for not rendering assistance.63 In the other two cases ending in convictions (in 1829 and 1841), the defendants were given prison terms of 12 months and one month, respectively.64 Both attacks, but particularly the violence of the 1829 assault, attracted sentences beyond the court’s standard correctives of small fines and orders to keep the peace.

40 In many jurisdictions, the treatment of female sexuality as a precipitating factor in sexual assault made rape trials an ordeal for victims. Using "a model of female sexuality as agent provocateur, temptress or seductress",65 justices and defence lawyers often minutely examined the sexual, moral and social history of the complainant and her previous relationship with the accused to determine how she had "contributed to her own downfall". On the southern Avalon, however, the former character of the woman complainant was called into question in only two cases – the alleged assaults of Mary Keating and Catharine Power – reflecting the persistent attitude in the justice system that women of "ill repute" could not be raped. Yet only in the case of Mary Keating did the court make its finding solely on the basis of the previous characters of the parties involved.

41 The British legal system could also monitor female sexuality by protecting the husband’s right to consortium. Because a husband had the right to control his wife’s body, he had several legal recourses if denied her sexual services. He could seek a court order to have his wife return to the matrimonial bed. He could also initiate various court actions against a third party and demand compensation for loss of consortium: criminal conversation (having sexual relations with the wife), enticement (encouraging the wife to leave her husband) and harbouring (providing the wife with refuge after she had run away).

42 There are only two brief references to loss of consortium matters on the southern Avalon during the study period. A court order in the 1773 records for Ferryland district directed Simon Pendergrass to pay Edward Farrel £5 in compensation for having had "criminal correspondence" with Farrel’s wife, a relationship that had apparently been going on "for some time".66 The second matter was fleetingly referred to in the letterbooks of the colonial secretary’s office in St. John’s. In October, 1760, Governor James Webb ordered William Jackson, JP of the district of Trepassey, "to take up and send hereunder custody one Clement O’Neal, who has carried with him ye Wife of Josh. Fitzpatrick as Likewise all his Moveable Effects".67

43 While details are sketchy, the two cases appear to have been handled in different ways, possibly reflecting a difference in attitude between the authorities involved. The Ferryland court seems to have dealt fairly leniently with the former case: it ordered a small payment to compensate the plaintiff, Farrel, for a rather long-term encroachment on his proprietary rights. The second order, which the governor issued after a hearing at St. John’s, had a more ominous and punitive tone. O’Neal was to be arrested and his effects attached. The order implied that Mrs. Fitzpatrick was to return to the matrimonial home. While the evidence is meagre, it is possible that the local magistrates had a more lenient attitude towards the issue of consortium than authorities more removed from local circumstances. Nonetheless, the scarcity of consortium cases fits with the prevalence of informal marital arrangements, the acceptance of informal separation and divorce, and the lack of pre-occupation with primogeniture68 and legitimacy in the southern Avalon – all elements of a marriage regime that kept relatively loose control over female sexuality.

44 The southern district court records for the period reveal only four cases involving domestic violence against women. Although such incidents, as with rape, were likely under-reported, the low numbers may have been a further indicator of plebeian women’s significant status within their families and their ability to hold their own in physical struggles. The magistrates on the southern Avalon appeared to be responsive to the woman complainant in each of the reported cases. In two matters, the alleged abusers were made to enter into peace bonds and ordered to return for trial; unfortunately, the judgments in these two cases were either not recorded or have not survived. The other two cases resulted in what were essentially court orders for separation and maintenance. There was no indication in the records that the magistrates, in their handling of the four cases, made any effort to encourage the complainants to return to their husbands.

45 Indeed, in a 1791 matter involving extreme domestic violence, the court moved quickly to protect wife and children and remove them from the abusive situation. Margarett Hanahan (also, Hanrahan) complained on 31 January that upon returning home the previous evening, she had discovered her husband, Thomas, trying to suffocate their youngest child and that he had later "ill-used" and flogged their older child with a bough "to oblidge it to make water". When Margarett had tried to interfere, Thomas had threatened her with a hatchet. The court observed the marks of violence on wife and children and sentenced Thomas to 39 lashes on the bare back as well as imprisonment until he could provide security for a peace bond. The magistrates also granted Margarett’s request to be separated from her husband. And two and a half months later, the court ordered the husband to leave the district. This was, effectively, an order for divorce – more than 175 years before the Supreme Court of Newfoundland had jurisdiction to grant divorces.69 Given the flexibility of the local marital regime, Margarett was certainly free to move into another, informal family arrangement; indeed, by 1800, she and her two children were living with John Ellis at Ferryland.70

46 None of the women involved in these southern Avalon cases was forced to remain in abusive marriages and none was found to have deserted and forfeited all rights to maintenance and child custody. Furthermore, the outcome of Hanahan v. Hanahan indicated the court’s willingness to punish excessively violent husbands in kind. This contrasted with 18th- and 19th-century cases in England and Planter Nova Scotia, for example, in which courts generally dealt leniently with wifebeaters and encouraged women to return to abusive situations for the sake of preserving the marriage, regardless of the violence of the assault. This was an approach which frequently placed battered women in even greater danger and which certainly discouraged the reporting of domestic violence.71

47 While Newfoundland courts did not obtain jurisdiction over matrimonial causes until 1947 or the power to grant divorces until 1967, magistrates did exercise a de facto jurisdiction in granting separations and support for deserted spouses and children. On this basis, they heard at least seven matrimonial cases during the study period, including the case of Mountain v. Mountain. One was initiated by a husband who had been turned out of the matrimonial home – an intriguing case in its own right, as the wife was ordered to pay him £3, "which is to be in full of all Demands he shall pretend to have on the House and Goods in Consideration that he has a Child to maintain".72 The remaining six were initiated by wives and again the local magistrates were pragmatic and responsive to the women involved, sanctioning de facto separations and awarding maintenance for wives and children, whether it had been the wife or the husband who had left the matrimonial home. It does not appear that magistrates applied pressure on wives to reconcile with their husbands in any of these cases.

48 As well, women who had separated from their husbands were not expected to live the remainder of their lives in sexual denial or forfeit all rights to child custody and support. For example, after Mary Dunn’s successful suit in 1791 for child maintenance from her estranged husband, Timothy, she began to cohabit with a William Hennecy, with no indication in the records that she thereby forfeited her right to child support.73 Similarly, Ann St. Croix of St. Mary’s was not penalized for her post-separation relationship with another man. On 16 October 1821, Ann brought her husband, Benjamin St. Croix, to court for neglect and ill treatment and sought an order for support for herself and their seven children. Ann was only 33 years old and much younger than her 77-year-old husband, a fact that the court clerk obviously felt worthy of note as he underscored their ages twice in the court records. The unhappy couple had already been living apart since 1819 and the court recognized this de facto separation. It also ordered Benjamin to give up the use of his house and garden to Ann and the children, to pay her £6 at the end of the current fishing season and to pay £5 annually for the future support of the children, who were to remain in Ann’s care.74 Ann may have already moved into another, informal marital relationship with Edward Power, a fisherman of St. Mary’s. Whether this was the case, or whether her new-found freedom from Benjamin had simply put her in a celebratory mood is unclear, but on 17 July 1822, almost nine months to the day after her court-sanctioned separation from her husband, Ann gave birth to a male child who, she claimed, had been fathered by Power. That October, she went back to court to seek support for the child from her new paramour, but he had already left the area and was not expected to return. Nonetheless, the court ordered that the balance of his wages with his current employer, £4.15.4, be retained for the support of the child and that from this amount, 40s. be paid for lying-in expenses and 3s. per week for support until the wages were depleted.75 Furthermore, there was no hint of moral judgment about Ann’s extramarital relationship with Power, and she did not jeopardize her original claim for child custody or support from her former husband, St. Croix.

49 The wife’s character during the marriage was also not at issue in the awarding of support. On 13 August 1804, for example, Mary Kearney of Trepassey told the court that her husband, Andrew, had "turned her to Door" about 15 months earlier and that she had since been supported by her brother. Andrew testified that since the marriage, Mary had "behaved very Ill frequently getting drunk and totally neglecting her household affairs". Furthermore, six months after the nuptials, Mary had given birth to a male child who, according to Andrew, was not his. Yet, despite Andrew’s claims concerning his wife’s slatternliness and sexual immorality, the court granted Mary maintenance of 3s. per week for life, provided that she had no children by any other man. Furthermore, Mary obtained this order despite having some alternative means of support (her brother); thus, the court was acting not out of concern that Mary would become a charge on the community, but in recognition of her right to maintenance from her husband who had turned her out of the matrimonial home.76

50 What is most striking in the court life of the southern district is its relatively benign treatment of female sexuality when compared with other jurisdictions in Britain, Canada, and even Newfoundland. Christopher English has offered some explanations for the court’s pragmatism in its dealings with both men and women. He notes that the Judicature Acts of 1791, 1792 and 1809 provided that English law be received in Newfoundland only "so far as the same can be applied".77 The local magistrates were men with stakes in the community, he argues, who dispensed justice based on an understanding of local issues and a familiarity with local inhabitants; if they thought English law was deficient or inappropriate for Newfoundland situations, they simply made new law. These are useful insights into how the legal regime manifested itself "on the ground" in many outports during the period.

51 However, local magistrates and administrators (most wore a double cap) on the southern Avalon were also part of the emerging middle class with its middle-class ideals of femininity. Certainly, the behaviour of women within their own class was carefully monitored. Although there were some 18th-century women of the local gentry who led public and independent lives, most women of this class were retiring into genteel domesticity by the turn of the following century. Wives and daughters socialized only with other middle-class families in the area or in St. John’s (some also wintered with relatives in England). They married members of their own class. They did no physical labour on flakes or in fields; rather, their work entailed rearing children and supervising domestic servants. They did not appear personally in the court house. In matters that did involve them, such as probate or debt collection, they were usually represented by men from their own circle. Certainly, their names did not appear in any of the cases involving assault, bastardy, slander, rape or domestic violence. (This is not to suggest that such incidents did not occur among the middle class, but merely that they were not played out in public.) Totally absent in the area were the types of activities that gave middle-class women elsewhere a "respectable" admittance into the public sphere – church fund-raising and philanthropic work, for example, or involvement in anti-slavery and temperance movements. These women’s lives were increasingly circumscribed by the parameters of gender ideology; indeed, the gentility and respectability of these women helped to maintain class boundaries in small fishing communities where contact between middle-class and plebeian men was more frequent and social distance therefore less clearly demarcated.78

52 Yet, while middle-class contemporaries in Britain were trying to encourage a modified form of respectability among the working class – one that involved a refashioned construction of female respectability – middle-class magistrates and administrators on the southern Avalon had reason to hesitate in imposing restrictions on plebeian women. These men were primarily either merchants or agents, or connected by kinship or marriage to local mercantile families that made their money by supplying local fishing families in return for their fish and oil. And the resident fishery had become overwhelmingly dependent on household production in which the labour of plebeian women, work that took place in public spaces on stage head and flake, was essential. In addition, these women, in their various economic capacities, were also an intrinsic part of the exchange economy and the truck system – the supply and credit practices which underwrote the resident fishery. The working woman was not a "social problem"; she was an economic necessity. It was, thus, not in the interests of local magistrates to encourage the withdrawal of plebeian women into the respectability of the private sphere.79

53 The other key player in Peggy Mountain’s drama was the Catholic Church. Why was the response of the priest to Peggy’s situation so different from that of the magistrates? The answer may lie with the relationship between Irish plebeian women and the Catholic authorities. Father Browne also had a stake in the local community; he too was familiar with local circumstances and personalities, as he had been at the mission in Ferryland for 20 years. Yet he did not try to accommodate Peggy as did the local magistrates. Rather, he hounded Peggy out of the district because of her "deviant" sexual behaviour. It might be tempting to explain the matter simply in terms of a clash between secular and religious authorities over jurisdiction in arbitrating local disputes. Yet this model of tension must be qualified. Browne did not regularly intervene in other matters before the court. Indeed, he often socialized with Carter and other local merchants and magistrates, and would himself be shunned and stripped of his priestly faculties by his bishop in 1841 on a litany of charges, including his too frequent and conspicuous fraternizing with the local Protestant "Ascendancy".80 If this was a turf war, it was fought on the grounds of female respectability, for the tension in the episode appears to have emanated from Browne’s dissenting views on the regulation of Irish-Newfoundland womanhood.

54 Certainly, Father Browne’s reaction was not out of line with church efforts to monitor female sexuality. When Catholic clergy were finally permitted to operate openly in Newfoundland after 1784, priests were overwhelmed by the numbers of informal family arrangements in their new missions. In Father Ewer’s 1789 report on Ferryland district, it was the indecency of women’s having multiple partners that became the particular focus of paternalistic concern (or, perhaps, blame), as he noted:The magistrates had for custom here, to marry, divorce & remarry again different times, & this was sometimes done without their knowledge, so that there are women living here with their 4th husband each man alive & form different familys in repute. I would wish to know if these mariages are but simple contracts confirmed & disolved by law, or the sacrament of matrimony received validly by the contracting partys. If the latter it will be attended with much confusion in this place, with the ruin of many familys & I fear the total suppression of us all as acting against the government.81British authorities in Newfoundland acknowledged the validity of some local marriage practices, given the lack of access to formal marriage rites in the period.82 But the Catholic church, which had grown away from its Celtic-Christian roots by the late 18th century, was not so sanguine and, while realizing that it must tread carefully around local regulations, was determined to untie such bonds that yet "remain[ed] to be separated from adultery".83 With the priests, then, came a concerted effort to bring women into formalized marriages within the precepts of the church. Parish records after 1820 suggest the priests enjoyed increasing success and, as a result of their efforts, the options of cohabitation and informal separation and divorce disappeared.

55 The dichotomized construction of woman as respectable wife and mother or temptress Eve was also part of church discourse. Thus, with the priests came the practice of "churching" women after childbirth. This was a perfunctory, shady ritual, usually a few prayers mumbled at the back door of the priest’s residence over a woman who had to be "purified" for the "sin" of conceiving a child. With the priests also came a more systematic shaming of adulterous wives and unwed mothers, reflecting a double sexual standard that laid the "sin" of pre- and extra-marital sexual relationships overwhelmingly at the feet of "unchaste" women. Particularly in terms of illegitimacy, mothers were punished more harshly than fathers, suffering public humiliation, even ostracism, as they were denounced from the altar and denied (either for a limited period of public penance, or indefinitely) churching and the sacraments.84 Here, then, was a reinforcement of the chastity requirement of middle-class ideology.

56 Church efforts to control "unruly" womanhood gained momentum after Bishop Michael Fleming assumed office in the 1830s. The desire to monitor female virtue was the primary motivation in Fleming’s decision to bring the Presentation nuns to Newfoundland from Galway in 1833. In his 1837 report to Propaganda Fide, he expressed his abhorrence of the way in which "the children of both sexes should be moved together pell-mell" in the island’s schools and portrayed their intermingling as "dangerous" and "impeding any improvement of morals".85 In a later letter to Father O’Connell, he explained his urgency in sponsoring the sisters’ mission, even at considerable personal cost. It was crucial, Fleming felt, that young Newfoundland women be removed from mixed schools in order to protect "that delicacy of feeling and refinement of sentiment which form the ornament and grace of their sex". In separate schools, the nuns could "fix . . . [their] character in virtue and innocence", prepare them for motherhood and domesticity and lead them to their destiny as moral guardians of their families. A curriculum that included knitting, netting and plain and fancy needlework would ease the transition from work on flakes and in gardens to pursuits more properly reflecting womanly respectability. And "solidly instructed in the Divine precepts of the Gospel", they would abandon the ancient customary practices that were an alternate source of female power, a power that competed with the church’s own authority in the spiritual realm.86

57 The Presentation sisters did not actually arrive in communities on the southern Avalon until the 1850s and 1860s. But the effort to rein in unruly womanhood had begun with the arrival of sanctioned Catholicism, and was articulated as early as Father Ewer’s 1789 expression of concern about women’s living arrangements. Furthermore, the endeavour intensified as the 19th century unfolded. And while a conflict existed for local magistrates between ideology and economic reality, there was no such conflict for the church in the pursuit of its civilizing mission on the southern Avalon. Within the framework of Catholic orthodoxy, the denial of female sexuality, the celebration of selfless motherhood, and the increasing pressure on women to transform their homes into spiritual havens, removed from the outside world, were impelling women to retire into domesticity and respectability. These pressures would intensify as the repercussions of the devotional revolution in the Irish-Catholic church of the later 19th century were felt through the regular recruitment of religious personnel from Ireland.87

58 Still, church constructions of femininity met with resistance from the plebeian community because they clashed with the realities of plebeian women’s lives. But some inroads were being made by the 1830s. Father Browne’s success in driving Peggy Mountain out of Ferryland suggests a widening of the wedge. A further indicator was the virtual withdrawal of Irish plebeian women from the courts on matters specifically related to female sexuality. Although they continued to appear in the records on matters such as debt, wages, common assault and property, their willingness to pursue matters such as sexual assault, domestic violence, bastardy, separation and maintenance seemed negligible after the 1830s. Only four such cases survive in the records – one sexual assault (1841), one case of domestic violence (1843) and two bastardy suits (both 1854) – despite a growing population. Women were increasingly reluctant, then, to air these matters in public, a reluctance that can be linked more readily to church attributions of shame and guilt to female sexuality than to magisterial hostility. Increasingly wary of public court actions, Irish women were left with the weaker options of either handling these matters privately, or not pursuing them at all.

59 During the last half of the 18th and the first half of the 19th century, middle-class ideals of female domesticity and respectability infiltrated Newfoundland society through its English legal regime and an emerging local middle class of administrators, churchmen and merchants. These middle-class constructs of female respectability did not, however, easily insinuate themselves into Irish plebeian culture on the southern Avalon, where women played a significant role in community formation, held property, inhabited public spaces such as court house and stage head, had a joint custodial control of culture and a powerful place in an alternative belief system that ran in tandem with formal Catholicism, and played vital roles in subsistence and in the production of saltfish for the marketplace. Furthermore, while local administrators and magistrates on the southern Avalon, such as Carter, were part of the emerging middle class with its middle-class ideals, and certainly they carefully monitored the behaviour of women within their own class, they had reason to pause in trying to impose restrictions on plebeian women. As members of local mercantile networks, they were dependent on the presence of plebeian women in the public economic domain. These local magistrates, therefore had a collective interest in forestalling the equation between plebeian female respectability, and the private sphere. The Catholic clergy, by contrast, saw the regulation of "unruly" womanhood as part of their civilizing mission in Newfoundland and pursued this goal with increasing zeal as the 19th century progressed. While church ideals of femininity conflicted with plebeian realities, their efforts were already making inroads as the Water Lily slipped its moorings at Ferryland and carried Peggy Mountain into historical obscurity.

Notes