"After Midnight We Danced Until Daylight":

Music, Song and Dance in Cape Breton, 1713-1758

Kenneth Donovan

1 LIFE WAS PHYSICALLY DEMANDING for the French who settled along the coast of Cape Breton (Ile Royale) in the early 18th century. The work associated with fishing properties seemed endless: obtaining fresh water, clearing land, building boats, preparing stages, erecting flakes, mending nets, planting gardens, cutting firewood and processing vast quantities of fish. And then there was the construction of the massive stone fortifications at Louisbourg – the largest in North America – requiring the labour of hundreds of workers over a 30-year period. During the busy fishing and shipping season from May until October, there was little time for leisure activities. Louisbourg residents such as Jerome Lartigue, the king’s storekeeper, lamented the endless drudgery and lack of intellectual and cultural stimulation in Cape Breton. Returning to Louisbourg in September 1754 after a voyage to France, Lartigue complained that it was "too bad that he [had] lived for such a long time in a country so rugged, and where the men are so little civilized".1 Compared to France, in the midst of the Enlightenment, Cape Breton, with its approximately 10,000 people (civilians and military), seemed devoid of French culture.

2 Despite Lartigue’s pessimistic assessment of life in Louisbourg, there is evidence that there was a significant transfer of European cultural life to Cape Breton in the early 18th century.2 The educated elite brought their elaborate meals, fine china, delicate fabrics, geometric gardens, scientific curiousity, music and their books. Michel Des Bourbes, a lieutenant in the garrison, for instance, read works such as John Locke’s Essai Concernant L’Entendement Humain (Amsterdam, 1729) while in Louisbourg.3 With literacy rates of perhaps 10 per cent in Cape Breton and around 30 in France, Des Bourbes’ facility with the written word was the exception. Although the Enlightenment was increasing the popularity of books and reading, European culture in the 17th and 18th centuries still emphasized oral communication and the primacy of hearing and touch.4 Story-telling was a much-appreciated social skill and many people gained access to books by hearing them read aloud. In this context, music was of central importance to the lives of people at all levels of society. Whether at court, at church, at home or in the tavern, music was a part of everyday existence in 17th- and 18th-century France.5 This was the case in Cape Breton too, as French immigrants carried their musical tastes and traditions with them. Musicians and their instruments helped ease settlers’ transition to the New World, as they had the power to lift people’s spirits and soothe the pains of loneliness and to reach the literate and the illiterate.6 The importance of music to life in Cape Breton, however, is not immediately apparent from archival resources, as most music was played, sung and danced without musical notation and thus there is little record of it.

3 Some of the transfer of Old World musical traditions was a matter of conscious policy. Fishing companies, for instance, sought to keep up the morale of their men by providing musical entertainment. Such was the case with Antoine Carin, an indentured servant from Meaux (a town near Paris), who was recruited to work as a musician for an Ile Saint Jean (Prince Edward Island) fishing company and arrived on the Comte de Toulouse in 1719 along with three other skilled servants.7 Military officers and royal officials recruited musicians in France as well to play at numerous private and public functions in the colony. Jean Pernay, a musician-soldier who came to Louisbourg from Nancy in 1758 was a cantor.8 Some of the musicians Louisbourg military authorities hired were from renowned backgrounds. In 1729 Antoine Sabatier, attorney general of the superior council, arranged for 14-year-old Christophe Chiquelier junior to come to Louisbourg.9 His father, also named Christophe, had accompanied the young Polish Princess Marie Lesczynska, the future queen of France, on various musical engagements throughout France during the 1720s.10 An accomplished musician and instrument maker who maintained the musical instruments in the king’s chambre, Chiquelier senior specialized in building and repairing harpsichords.11 Chiquelier also attended to Louis XV (1715-1774) on his musical sojourns and maintained the harpsichord for him at Versailles, Fontainebleau and Marly, among other locales.12 After his discharge from the military in the early 1730s, Chiquelier junior returned home and in 1737 he succeeded his father as maker of harpsichords and keeper of the musical instruments for the royal family.13 Until his death in 1792, Chiquelier was charged with transporting, maintaining, tuning and repairing all of the instruments in the king’s chambre.14

4 Although recruited as a musician, Chiquelier was not so described in his military company. Similarly, although musicians were not usually listed as crew members aboard the king’s vessels that came to Louisbourg and other ports of the New World during the 18th century, it was common practice for the captains of French vessels to recruit a few musicians who could provide entertainment for officers and crewmen.15 The memoirs of Sieur de Dièreville, a French surgeon who came to Port Royal in 1699 to collect specimens for the Royal Botanical Gardens in Paris, reveal the sophisticated musical tastes aboard some French ships. Dièrville noted that Chevalier de Chavagnac, the captain of the Avenant on which he returned to France, ensured that a few crew members served as ship’s musicians as well as officers. Two of the ensigns, Monsieur D’Albon, and Monsieur le Gardeur, both "sang very agreeably" and there was instrumental music to accompany them.16 Dièreville writes of another passenger, Monsieur de Frontenau, an official charged with government instructions for proposed settlements in New France, as "very fond of Music & sings tolerably, [He] had brought a Musician with him; he had a Clavecin, a viol & other instruments, to which were added three Hautboys belonging to the Crew of Monsieur de Chavagnac: in fine weather, concerts were given, & the pleasure we took in them made us forget that we were on the deep".17 On the voyage Dièreville wrote a number of songs set to the melody of several operas "for a little Entertainment, which our Musicians had devised".18

5 Hundreds of king’s vessels such as the Avenant, with musicians among the crews, called at Louisbourg.19 Music was also vital to shipboard life among smaller vessels calling at Cape Breton. When ship captain Marc Leblanc died on a voyage from Saint Domingue to Louisbourg on 8 August 1732, his possessions included two bells – ideal percussion instruments.20 Nine years later, another ship captain, Jacques Brulay of the 25-ton L’Esperance, died in Port Dauphin (St. Ann’s) shortly after arriving from Martinique. His possessions included a violin, two bows and "a case filled with papers and lists of music".21 Louisbourg residents contributed to the music aboard ship. Jean Lascoret, a native of Bayonne, who came to Louisbourg in 1734 to serve as a clerk for various merchants, had a transverse flute and the body of a guitar with him when he died on a return voyage from the West Indies in 1741.22

6 In garrisoned towns and communities such as Louisbourg, Placentia, Canso, Halifax, Annapolis Royal, Boston, New York, Quebec and Montreal, military personnel did double duty as musicians.23 Jean Hardouin, who served in the Louisbourg garrison during the 1740s, was known by his nom de guerre, "La Musique".24 Pierre Geoffrey, a 32-year-old married soldier and carpenter by trade, came to Louisbourg in 1750 as a member of the cannoneers, an elite company. He was known by his nom de guerre "La Vielle" (hurdy gurdy).25 Two musicians recruited for the garrison in 1751 included 19-year-old Dominique Antoine, a native of Avignon and member of Captain Thierry’s Company, and 20-year-old Antoine Duval, a soldier since the age of 14.26 Drum major Pierre Boziac, a member of the garrison in 1754, was a dancing master who taught the young girls of Louisbourg.

7 Planned festive activities, especially music and dance, were the highlight of the Louisbourg social life during the pre-Lenten carnival from 1 January until Ash Wednesday. Military engineer François De Poilly attended 10 balls during January and February 1758. At least three of the formal dances lasted all night, and offered food as well as music. For example, on 29 January there was a ball hosted by Monsieur Cabarus which began at eight o’clock together with a buffet that was served at two o’clock in the morning. Poilly noted: "After midnight we danced until daylight". With two days rest, Poilly wrote on 31 January that he only danced until one o’clock but there was a buffet which "was served in abundance". The last two events Poilly attended prior to the beginning of Lent were wedding feasts. On 5 February the Bourgogne Regiment hosted a ball and buffet in honour of Captain de Chauvelin who married Mademoiselle de Thierry. Finally, on 19 February, after more than a month of dancing and revellery, Poilly attended the wedding feast of Captain de Couagne and Jeanette de Loppinot.27

8 Dancing was part of the cultural identity of the French and they brought their traditions to Cape Breton and other parts of the New World.28 Louisbourg’s high-ranking officials sponsored musical and theatrical performances and, as Poilly indicated, dancing was usually part of the entertainment. Poilly and his contemporaries, such as the officers of the garrison and captains of the king’s and merchant ships, were familiar with aristocratic entertainment in France, such as the ballets de cour (theatrical spectacles with dancing) that included vocal and instrumental music.29 Marie-Elisabeth Bégon (1696-1755), born and married into the governing classes of New France, described how François Bigot, the former commissaire-ordonnateur of Louisbourg (1739-45), and the recently-appointed intendant of Canada, planned to come to Montreal in the spring of 1749 and sponsor dances and festivities to commemorate his appointment. In anticipation of his arrival, she noted on 19 December 1748, "everybody was learning to dance". Eight days later she wrote that there were not enough dancing masters "for all those who wished to learn to dance".30 Dancing was hardly restricted to the elite, having been the most popular pastime among all classes of society for centuries.31

9 During the 18th century, the majority of dances throughout the Western world were of French origin or had been adapted by the French, especially those incorporating the minuet, the gavotte, the rigaudon, the bourré and the branle. It was through the practice of French dance that the two-part form movement became the accepted standard. Rhyming poetry and dances had used a two-part rhythm since the Middle Ages and the music to accompany the poetry and dances merely followed suit. It was only during the 18th century, however, that the two-part movement with reprise reached its height and furnished a structural plan for dancing.32

10 The citizens in New France, as well as people in British-controlled Nova Scotia, kept abreast of recent developments in musical composition, sharing in a popular "new interest" in music that began to emerge among cultured people throughout the 18th century.33 The movements of musicians and instrument makers helped them to do so. Christophe Chiquelier had spent a year as an apprentice to master-instrument maker Jean Claude Goujon of Paris prior to coming to Louisbourg in 1729.34 The French cleric Jean Girard (1696-1765), who came to Montreal in 1725 and became "maitre de chant" in the Sulpician school and organist in the parish of Notre Dame, brought his extensive musical knowledge to his post. His superior, François Vachon de Belmont, had asked for a school teacher who could teach plainchant and Girard, who worked at the boys’ petite école, doubtless taught his students to sing canticles. In addition to having extensive training in plainchant, singing and percusson keyboard instruments, Girard may have studied organ with the renown French organist Louis Clérambault (1676-1749) or with Jean-Baptiste Totin, the nephew of Guillaum-Gabriel Nivers, Clérambault’s predecessor.35

11 Individuals such as Chiquelier and Girard brought the music of western Europe to the New World. The works of Jean Baptiste Lully, the dominant figure in French music from 1657 to 1687, whose compositions defined the French style in ballet, comedy-ballet and opera, were familiar in Louisbourg and elsewhere in New France.36 Lully’s march La Générale was played by the Louisbourg drummers each day as part of their rounds of the town.37 The intendant in Quebec, Claude Thomas Dupuy, had most of Lully’s operas in his library. Julien Guignard, a chef for Monsieur de Pontbriand, Bishop of Quebec, had a small book of drinking songs "set to Lully’s airs".38 In the same manner, there is evidence that the officers among the British garrison at Annapolis Royal kept abreast of musical developments in England. In May 1735, King Gould, British supplier to the garrison, sent a copy of "Purcell’s music for the fiddle" to William Shirreff, a member of the first governing council of Nova Scotia and a long-serving officer at Annapolis.39

12 Within the New World, music travelled across imperial boundaries. One of the people who facilitated this was Peter Faneuil, a leading Boston merchant who began trading with Cape Breton as early as 1728. A patron of the arts, Faneuil had a keen interest in the development of music and drama in New England. By 1740 Faneuil, one of the wealthiest men in Boston, had donated £100 towards the purchase of an organ at Trinity Church and that same year he offered to erect a building as a public market and town hall for the benefit of the poor.40 After Faneuil Hall was opened in 1742, the building was often used as a concert room and in 1747 Governor Charles Knowles of Louisbourg sponsored a public concert there.41 By 1738, Faneuil was providing Louisbourg with books of music, appointing Thomas Kilby as his agent at Canso.42 Jean Baptiste Morel, Faneuil’s agent at Louisbourg was a native of St. Didier, France, and a successful merchant with numerous contacts in the community.43

13 Books of music were sold to the general public in shops throughout Louisbourg. Jacques Rolland, for instance, had 45 books of music for sale in his shop near the parade square in 1743, 38 small books of pastorales and seven books of noels.44 Pastorales were instrumental or vocal compositions with a pastoral theme whereas noels were mostly parodies, set to music with flexible rhyme schemes and part of a large body of chansons populaires.45 These books were from the genre of litterature de colportage or pedlar’s literature, written for the lower classes and concerned with religion, magic, entertainment and popular sensibility. They were printed on poor-quality paper with inferior bindings and were suitable for reading and singing in Louisbourg homes and drinking establishments.46 Yet another Louisbourg merchant who had song and hymnal books for sale was Pierre Lambert, who operated a shop on rue St. Louis beginning in 1741. He had seven small Cantiques sur la mort de Notre Seigneur and 10 books entitled Cantiques de Marseilles at the time of his death in 1756.47 Blaise Lagoanere, a prosperous merchant, had music books and verse in his library, including one work entitled Les sept psaumes en vers français.48 It was also possible to buy musical instruments from Europe. Jean Chevalier, a Louisbourg merchant was able to purchase a violin with its case, bow and 12 assorted strings for 10 livres in 1721.49 And some immigrants sold musical instruments on a speculative basis. Captain Goubert Coutis, who sailed the St. Esprit from Bayonne to Louisbourg in October 1752, brought 24 violins that he sold for 20 livres each.50

14 Louisbourg officials and their families followed musical taste and tradition in Europe by purchasing books such as Les sept psaumes en vers français and the Cantiques de Marseilles. Songs with historical themes rooted in classical mythology were common in Europe and, according to one eyewitness, they were popular in Louisbourg as well. Visiting the home of a Louisbourg family in 1755, a Mi’kmaq visitor noted that each night the master of the house took out a songbook and led his family in singing: "They continually sang and recited material from the [song] book each evening" and "the father would also put down the [song] book and lead the family in singing from memory".51 Some Louisbourg officials had relatives in Quebec or France who were musically trained, and this too helped them to keep abreast of musical trends and developments. Captain Michel DeGannes of the Louisbourg garrison had a brother who was a canon at the cathedral in Quebec City.52 Robert De Buisson, who spent a year in Louisbourg in 1726-27 as a subdelegate of the intendant for New France, was the son of Jean-Baptiste Poitiers De Buisson, the organist in the church of Notre Dame in Montreal from 1706 to 1727. Robert De Buisson was doubtless also trained in music.53

15 Louisbourg residents maintained musical contacts with France and Quebec by other means as well. Some Louisbourg parents, believing music to be an essential part of their children’s education, sent them to France and Quebec for schooling, including musical training.54 Such was the case with Marie Anne and Antoine Peré, owners of a fishing concession that employed 40 fishermen by 1724.55 When Antoine died in 1727, his wife assumed responsibility for the fishing business and for the education of their children.56 Although illiterate herself, Marie Anne sent her youngest son, 14-year-old Antoine, to Saint Servant, Brittany, in 1731 to attend "a good boarding house where he can benefit the most and while he is young he can receive all the education a young man can be offered".57 Antoine’s boarding school had at least three different instructors offering courses in arithmetic, writing, navigation, dance and violin. Music and dance comprised an integral part of Antoine’s schooling and two teachers instructed Antoine how to play the violin as well as to dance. The costs of Antoine’s schooling in 1732-33 included two livres one sol for "a month of dancing school" and 10 sols for a violin and strings. Antoine’s musical education continued throughout 1733 and 1734, with yet more dance and violin lessons and instruction in reading music.58

16 For those parents unwilling or unable to send their children to France or Quebec, there were, at different times, at least three dancing masters in Louisbourg who offered instruction in music, dance and the delicate arts of walking, talking and sitting gracefully. Dancing master Simon Rondel, a native of Namur, France, (now Belgium) came to Louisbourg in the 1720s and, except for a period of absence in 1729-32, lived in the town with his wife and three children and taught dance and music.59 Although the French style of singing was primarily confined to salons and theatres, French dancing masters and dancers travelled throughout Europe teaching French dances.60 When they emigrated to the New World, French dancing masters tended to move to the British North American colonies rather than New France since their much larger populations provided more employment opportunities for them.61

17 Decoudray Feuillet was another of Louisbourg’s dancing masters, tutoring the children of prominent families. In 1754, after at least five years in the colony, Feuillet left his wife in Louisbourg and went to New York to teach music and dance. Writing in December 1754, Thomas Pichon, former secretary to Louisbourg Governor Jean Raymond, noted that "Decoudray, whose wife keeps a pot house and is greatly favoured by the authorities, has been in New York for the past six or seven months. This man, who has spent his life among the soldiers and constabulary of France, plays the violin and teaches dancing. His violin would enable him to earn a living in a land, whose language I do not think he understands".62 Decoudray Feuillet may have left for New York because he was experiencing competition from another Louisbourg dancing master, Pierre Boziac, who was visiting homes throughout the town teaching children how to dance. A drum major in the Louisbourg garrison, 38-year-old Boziac visited the home of Jean Baptiste Duboe for two months in 1754 where, for six livres per month, he taught the daughter of Thomas Power, an Irish merchant in Halifax, how to dance. Boziac had a number of students besides Power’s daughter and travelled to the Barrachois, just outside Louisbourg’s main gates, "to give lessons" to his female students there.63

18 Amand DeGraves, a native of Bordeaux who lived in Louisbourg during the 1740s, went to Boston to teach French and possibly dancing too in the 1750s.64 Louisbourg dancing masters doubtless taught in the nearby English-garrisoned settlement of Canso as well, and this probably explains how Deborah How, who was raised on Grassy Island in Canso Harbour from 1725 to 1744, received a good education in French and dance. Deborah was the daughter of the influential Edward How, the leading merchant and civilian official in the fishing outpost and a frequent visitor to Louisbourg.65 Deborah How eventually opened a "female academy" in Halifax where she taught French and dancing as well as reading, writing, arithmetic and sewing.66 She was following in the steps of Henry Meriton who opened an academy on Grafton Street in Halifax in 1753 (the same year Thomas Power and his wife sent their daughter to Louisbourg to be taught music and dance) offering French and dancing as well as reading, writing, arithmetic and Latin. "Young ladies as well as Gents", noted the prospectus, were to be "taught dancing every Wed & Sat afternoon". Three years later Hanna Hutchinson also offered French and country dancing lessons in Halifax.67 In a similar fashion, some Louisbourg children and young adults were sent to Boston and Newburyport to learn English.68 Other Louisbourg children studied music as part of the educational curriculum they received from the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre Dame, who taught the singing of canticles – sung outside of mass, especially at catechism and during the school day.69 Since canticles were sung in French, the children did not necessarily have to learn the Latin of the liturgy of the mass.70

19 Masks for costumed balls, dances and displays were commonly imported into Louisbourg. Masks were a requirement for formal dances and theatrical displays. Masked balls, the highlight of the French court during carnival season, were spectacular events usually restricted to the nobility. Throughout the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the order of the dances at the royal masked balls followed a set pattern: the branle was performed first, followed by a gavotte and a minuet. Dressed in their exotic costumes, the dancers spared no expense to gain the recognition of the assembled courtiers. Although the balls were always expensive, they became even more elaborate near the end of the 17th century. French journals such as the Gazette de France and the Mercure, as well as foreign newspapers, reported on these lavish balls in great detail.71 In this manner, the people of Europe, as well as the king’s own subjects, at home and abroad, became aware of the grandeur of the state and began to imitate, in a more modest fashion, the entertainments of the French court. On 12 July 1752 Captain S. Herogoyen arrived in Louisbourg from Bayonne in the Le Notre Dame De Paix with 60 masks for sale. Less than a month later, Captain Louis Le Brun sailed La Dauphine into the harbour with another 60 masks. The masks were sold for two livres each.72 Another 48 masks were imported into the colony the following year and sold for three livres each.73 Masks were usually for sale in Louisbourg’s shops. During the summer of 1757 Bernardine Poinsu purchased seven common masks as well as six fine masks at an auction in Louisbourg; a Monsieur Laurvin purchased four masks at the same sale.74 Masks were essential for masquerades as well, which had a long history by the middle of the 17th century. A type of ballet, the formal masquerade included a group of people dressed in costume to suit a particular theme. The participants moved around together at a masked ball but may or may not have participated in the dancing. With light-hearted themes, masquerades could be comedies or burlesques, usually with a rustic setting. Masquerades also referred to short dances performed during the course of masked balls, particularly during carnival time at court in the late 17th century.75

20 Although there is no evidence of public theatre in Louisbourg during the French regime, dramatic presentations took place among small groups of people as part of an intimate entertainment. Some Louisbourg residents had books of poetry and burlesque among their libraries.76 Dramatic performances were also sponsored by the Catholic Church in order to make the liturgy more accessible. Choral music and plainchant were featured in the celebration of the mass as well. In Quebec, the Ursuline nuns sponsored pastorales. With no dramatic conflict or plot, the pastorales were not so much plays as recitals of passages accompanied by music;77 usually written in praise of someone, the pastorale was a poem that was made dramatic by a number of different readers or performers.78 Judging by the many pastorals for sale in Louisbourg shops, dramatic readings were commonplace.

21 Theatrical events featuring comedy or burlesque had been performed almost from the beginning of permanent French settlement in North America. The first commissioned musical performance in New France was a masque commemorating the return of Baron de Poutrincourt, lieutenant governor of the new colony at Port Royal, on 14 November 1606. Entitled the "Theatre of Neptune", the masque, composed by Marc Lescarbot, contained some verse which was to be sung in four parts with cues for the playing of trumpets. Lescarbot’s masque was part of a welcoming address, also known as a réception or entrée royal, that had become a formal tradition in France during the 16th and 17th centuries, prior to the establishment of Versailles as the seat of government in 1682. As the king moved from town to town staying at various chateaux and manor houses, he was greeted with a royal reception featuring mimed scenes, verse and some music.79

22 Royal entries, military victories, fairs and important political events such as the birth of the son of the king or the signing of a peace treaty were usual occasions for public celebrations.80 In volume six of the Encyclopédie, Louis de Cahusac described in detail the Royal Banquet at the Paris town hall on 8 September 1745, commemorating the victory of France at the Battle of Fontenoy, in the hope that the description would be "of use to the history and development of the arts".81 To celebrate the king’s return from Fontenoy, the governor’s chambers were decorated as a concert hall, an ode on his majesty’s return was presented by Roy and later that evening, as the king, queen and royal family sat down to dinner at a table with 42 place settings, an orchestra of 60 musicians provided entertainment.

23 Although modest by comparison, similar celebrations were held in Louisbourg to commemorate events such as the birth of the Dauphin, the first son of Louis XV, in 1730, and the birth of the Duc de Bourgogne, the first son of the Dauphin, in 1752. The celebration in Louisbourg to commemorate the birth of the Dauphin followed the pattern of those in towns and cities throughout France. When word of the Dauphin’s birth reached Louisbourg in the fall of 1730, the acting governor, François De Bourville, arranged a celebration that included the singing of a Te Deum – the traditional Latin hymn of thanksgiving – during high mass in the chapel, special meals, distribution of wine to the citizens, a procession through the town, the lighting of lanterns in homes and numerous musket and cannon volleys. There was also a large public bonfire with smaller bonfires in front of some of the houses. As acting governor, Bourville sponsored a banquet for 80 followed by a ball. That same evening ordonnateur Le Normant De Mézy hosted a meal for 28 leading citizens of the town, including justice officials. Since his residence was too small to assemble everyone at one time, De Mézy hosted two other meals of 16 and 20 place settings for the captains and principal officers of the town. In return, the officers of the garrison, as a "sign of their happiness" with the birth of the Dauphin, put on a ball with a meal of 80 place settings. All of these festivities, which were described in detail to authorities in France, included music and dance just as they did in France.82 Even more extravagant celebrations were events planned for the birth of the Duc de Bourgogne in 1752 when, as in 1730, a band played for a ball for the officers and prominent citizens of the town, and six barrels of red wine were distributed for the citizens of the town.83

24 Louisbourg’s military drummers played a vital role in the various public celebrations throughout the town. As with most urban centres in continental Europe, martial music affected almost every aspect of daily life in Louisbourg, since the drummers beat signals which regulated the soldiers’ day as well as that of civilians. Initially, Louisbourg’s garrison was allocated one drummer per company within the Compagnies Franches de la Marine, so that there were approximately six to 10 drummers in the garrison throughout the 1720s and 1730s. In 1741, allocation was increased to two drummers per company so that by 1745 there were 21 drummers in the Louisbourg garrison: 16 for the Compagnies Franches, four for the Swiss Karrer Regiment and one for the artillery company, the Cannoniers Bombardiers (cover illustration). One fifer was designated to serve the eight companies of Compagnies Franches soldiers and one for the Karrer Regiment prior to 1745.84 By the mid 1740s there were five guard posts within the walls of the town and drummers were required to be continuously on guard at these posts. One drummer was also stationed with his company at the Royal Battery on the north shore of Louisbourg harbour.

25 Like the soldiers, civilians were awakened by the sound of the reveille at sunrise. Every morning drummers at each gate around the fortress would play La Diane for 15 minutes while the gates were unlocked. Playing La Garde called all drummers for daily inspection and gave notice to the new guard to prepare themselves for duty. Two hours after beating La Garde, the drum major led the drummers on a route throughout the town playing the Assembly, calling the soldiers of the new guard to assemble for inspection. During the evening the drummers marched again throughout the town playing the Retreat, which signalled the end of the day. Other drum signals were used for salutes, burials, prayers, public auctions and the proclamation of notices.85

26 Since the drum calls were part of a prescribed routine, they functioned as a time signal for the military and civilians. These routines and their concurrent activities gave a strong sense of order and community to the town’s citizens. For example, in 1732 Irish servant Thomas Eaton recalled arising before sunrise and retiring just prior to the sound of the Retreat. Drum calls such as Le Ban became so linked to public auctions that it became difficult to gather a crowd without a drummer. To highlight the vital role of drumming in French-garrisoned towns, two drums, together with crossed swords and flags, were included in the crest of Louisbourg’s Maurepas Gate facing the ocean.86 The large drums on the crest above the gate reminded visitors that martial music was a vital element in the life of a garrisoned town.

27 Intended for public consumption, drumming, in a sense, was every person’s music as it provided a live show for the elite, as well as for ordinary citizens. Whereas access to formal music performances was limited to the well-to-do, folk music and song, like drumming, were popular among all classes. Satirical songs of wandering musicians were a hallmark of popular culture throughout France in the 17th and 18th centuries.87 Only three years after the arrival of the French in Cape Breton, one official complained (1716) that "a maker of bad songs" had commenced to exercise his satirical muse. Judged to be "another pest on society", the authorities decided to impose silence on this "new poet" from Canada (Quebec).88 Ditties, sea chanties and derisive ballads, together with more traditional folk songs, were composed in Cape Breton and some of these have survived in the Louisbourg documentation.89

28 Taverns in Cape Breton, like those in France, were centres for music, ribald songs and accompanying dances.90 Tavern keepers such as Claude Morin, Marguerite Desroches and Madame Decoudray Feuillet, who was married to the violinist and dancing master Decoudray Feuillet, owned violins and presumably entertained patrons in their establishments. Marguerite, who was a fishing proprietor, had brought her violin with her from Saint Malo, Brittany.91 Music was simply part of the regular fare at some Louisbourg inns, and patrons were expected to pay for the entertainment as part of their room and board. Apprentice baker Bertrand Bonier stayed at Pierre Santier’s inn for a month in April 1737 and included among his expenses was one livre "for music".92 This was in keeping with French practices, where patrons paid for their music in taverns in and near Paris by the beginning of the 18th century, and professional musicians often went from tavern to tavern making a living by playing for dances. In other cases, tavern waiters played music for dancing and sought payment by using a money box for donations.93

29 Music, song and dance, combined with alcohol in the 90 drinking establishments that existed in Louisbourg between 1713-1758, could lead to difficulties for town authorities. Louisbourg officials issued an ordinance in 1720 forbidding the sale of alcoholic beverages during divine services on Sundays and holy days of obligation. The ordinance was repeated five times between 1734 and 1749.94 Taverns throughout Acadia (mainland Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island) also catered to drinking, singing and dancing on Sundays. In 1742, Bishop Pontbriand of Quebec issued a circular letter to the priests of Acadia prohibiting taverns from selling liquor on Sundays, feast days and especially during mass. The same circular chastised Acadian communities that permitted men and women to dance together after dark and even allowed the singing of "lewd songs".95

30 Lewd songs, drunkenness and dancing after dark offended many clergy and officials. The hours of divine service on the most solemn feast days, lamented Louisbourg ordonnateur Pierre-Auguste Soubras in 1719, were the times "selected for the most outrageous debauchery". And while the priests in Acadia were admonished for allowing dancing after dark, their permissiveness paled in comparison to the antics of the Louisbourg Recollect Superior, Bénin Le Dorz, who served in Louisbourg from 1724 to 1727. The Recollect was in the habit of "getting drunk three or more times a week in public". In spite of repeated warnings by the Bishop of Quebec, authorities noted in 1727 that Le Dorz "has continued, and continues still to become intoxicated and in that state to dance and do other excessive things".96

31 The other "excessive things" may have included singing derisive songs. During the reign of Louis XV the era of derisive laughter through song reached its peak, with more songs composed during his reign than any previous time. Favourite targets of these songs were Cardinal André de Fleury (1653-1743), the powerful minister of state, and Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour (1721-1764), the king’s mistress. Cardinal Fleury responded in kind, urging Jean-Frédéric Maurepas, the able minister of marine (1723-1749) who was in regular correspondence with Louisbourg, "to flood the streets with verses attacking his enemies".97 Maurepas’s satirical lyrics eventually cost him dearly since he was dismissed as minister of marine in 1749 for composing an indiscreet song about Madame de Pompadour.98 Lewd ballads, including songs of the Pont Neuf, the Parsian bridge which was a centre of popular culture in Paris, were well-known in Louisbourg and throughout New France. Even the expression "like a song of the Pont Neuf" was recognized as a mark of derision and cynicism in Louisbourg.99

32 Most songs in Cape Breton and New France, however, were folk songs directed towards the general populace, and were part of the language and folk traditions of ancient France, transported overseas to the New World in the early 17th century. Some 9,000 French Canadian folk songs have been collected within the past 150 years and more than 90 per cent of these originate in northern France. Sung in the homes, in the fields and at most social occasions, these folk songs were traditional unaccompanied songs that can be traced back to the troubadours of the Middle Ages.100 Some including "la chanson de Louisbourg", have survived among Cape Breton’s Acadians, whose family ties date to the French settlement of the island in 1713.101

33 As with the music of the Acadians, songs and music of the Breton, Norman and Basque fishermen who were among the earliest residents of Cape Breton during the 17th century have also survived.102 Prior to 1713 the people of Louisbourg settled in the fishing community of Placentia, Newfoundland and at least one of the surviving songs appears to have been written by three French fishermen before their emigration from Placentia to Louisbourg. Entitled "Chanson des terreneuvriers" and dated 1725, the song comes from a collection of manuscripts found locked in a secret drawer of a desk of a merchant family at Avranches Manor on the Normandy Coast in the 1960s.103 All of the papers in the collection date from the mid 1720s, so it is possible that the drawer had not been opened in more than 200 years.104

34 The song described the life of a three-man fishing crew aboard a shallop in the inshore fishery at Placentia, Newfoundland. Composed of 10 verses and written by several hands, the song described working conditions in the inshore fishery.105 The fishermen usually worked all day without drinking or eating, wore a large sheepskin apron dressed with wool, and had to work on Sundays and feast days. Dangerous at best, the work was usually done in bitterly cold weather:"Chanson Nouvelle des Terreneuviers" (1725)

Brave garçons des Iles qui voullez naviguet

n’allez pas terreneuve pour vos jours abregée

il n’y a que la paine sants jamais nul plaisir

toujours de sur les ondes au danger d’en mourir

Et puis quand on arrive, au bois fut aller

le long de la journee sans boire ni sant manger

au soir quand omne se couche dedans un petit coin

a l’ombre d’une de sus un peu de foin.

Et puis quand onne arrive dans ce mechants pays

l’onne se mait amorfondre dans des peaux de brebis

tous le monde resemble a se que vous voyez

en France sur les traites pour la farce jourir.

O Dieu est le mistaire de nous voir en le bord

du paint et du brevage encore n’avont pas trop

de la morue pourri et ne boire que de l’eau

n’est il pas pitoyable les vie des matelots

Retournons en nos Isles c’est un heureux sejour

allons voir nos maitresse et leur faire lamour

Leur contant le mistaire qu on nous a fait souffrir

pendant qu’ils sont a terre a bien leur rejouir.106The inshore fishery of Placentia had moved to Cape Breton in 1713 and thus the "New Song of the Newfoundland Fishermen", although written in 1725, described a period prior to the emigration of the French from Newfoundland to Cape Breton. The Cape Breton fishermen worked under similar conditions to those noted in "New Song of

the Newfoundland Fishermen", but fishing owners in Cape Breton took steps to ensure that their men were treated better, as labour was in high demand.

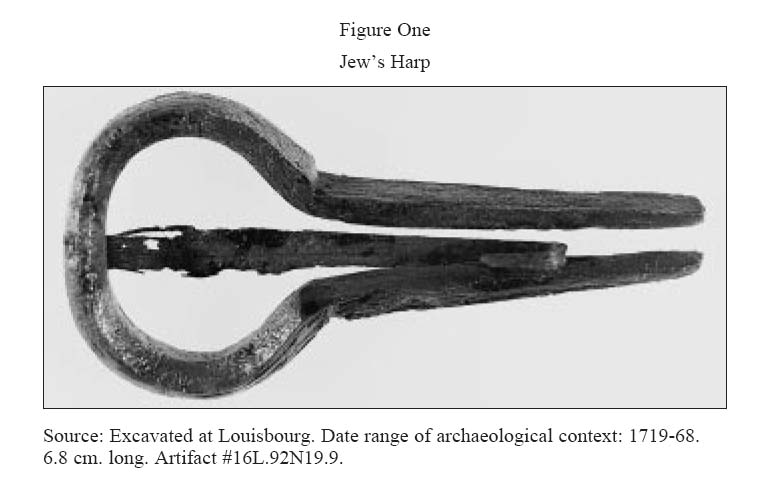

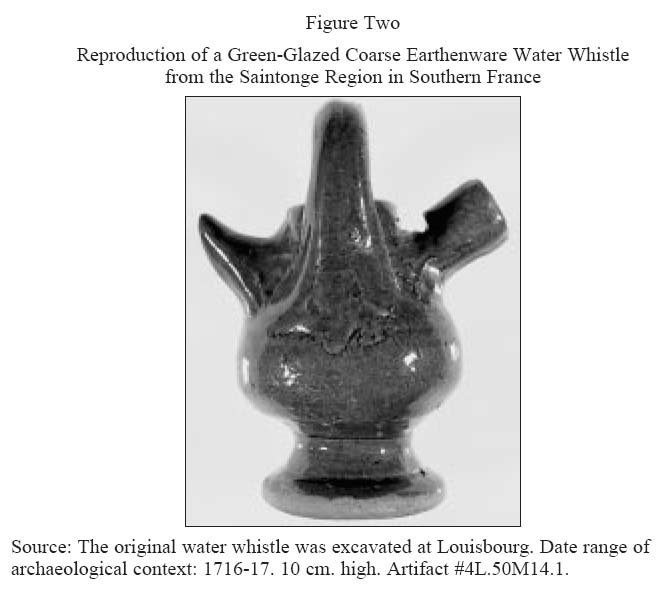

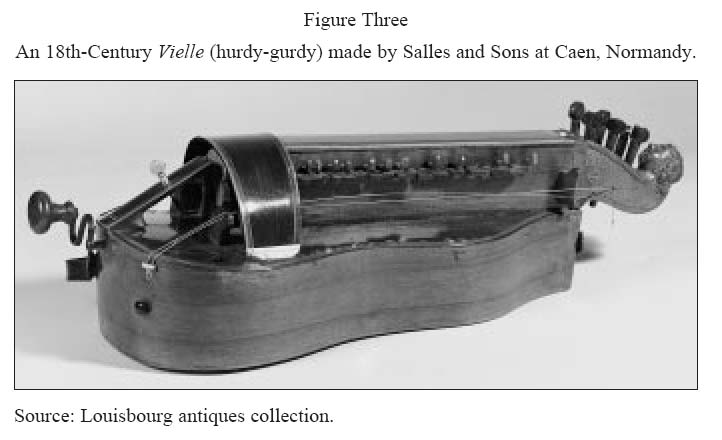

35 Although few instruments were listed among fishermen’s possessions, there is evidence that fishermen in Cape Breton entertained themselves with violins, flutes and Jew’s harps.107 The latter were available for sale in Louisbourg shops, and 19 iron and seven brass Jew’s harps have been found during historical excavations (Figure One). Whistles were also popular, and six coarse earthenware, three bone whistles and one brass one have been unearthed at Louisbourg (Figure Two).108 So too was unaided whistling. Louis Blaquiere of Montpelier, who was posted to Louisbourg in 1750 as a member of the garrison, was known as the "whistler".109 At taverns, fancy balls and theatrical presentations, music makers used folk instruments such as whistles, flutes and Jew’s harps together with such portable instruments as violins, guitars and vielles (hurdy-gurdies). One of the well-known players of the latter instrument (Figure Three) was Charles Duval, who had come to Louisbourg from Normandy in 1730 seeking work as a joiner and wood carver.110 Another joiner and master carpenter, Charles Lalu, known as "La Musette", may have played the musette, a small bagpipe pumped by the left elbow.111 These instruments, with accompanying songs, were part of the musical heritage of France and Europe.

36 Throughout New France the monodic plainchant was sung in Latin by one, two or three cantors as part of the liturgy of the Roman Catholic Church, ranging from midnight psalms to evening prayers. Often, two cantors, in alternating sequence, would answer each other. Instruments were not an essential part of the programme, but if there was organ music it would alternate with the sung verses. In New France, as in all Catholic colonies, the mass was the primary means of celebrating liturgical music. French Catholics maintained such a close connection between music and church ritual that singing was usually a part of the mass even when celebrated in private homes. Rosalie Trahan, a resident of Baye des Espagnols (Sydney), noted that on 11 February 1754 she attended a wedding mass which was "sung in the home of Paul Guedry".112 Much of the service of the mass, known as the "Ordinary", remained the same throughout the liturgical year, but the music of the plainchant changed according to the circumstances such as the feast day, the time of year or the category of the mass. An inventory of the Louisbourg chapel in 1724 revealed such standard musical compositions as a psalm book, a gradual, a gradual in plainchant, together with an ordinary missal for the mass in plainchant, a psalm book in plainchant and a vesperal in plainchant.113

Figure One : Jew’s Harp

Display large image of Figure 1

Figure Two : Reproduction of a Green-Glazed Coarse Earthenware Water Whistle from the Saintonge Region in Southern France

Display large image of Figure 2 Source: The original water whistle was excavated at Louisbourg. Date range of archaeological context: 1716-17. 10 cm. high. Artifact #4L.50M14.1.

37 The priest in the Louisbourg chapel would usually be accompanied by three cantors. An inventory of the chapel in the King’s Bastion in 1731 included a bench for the cantors in the choir.114 The cantors must have been in good voice when Antoine Paris (1677-1731), a prominent Louisbourg merchant, died that same year; eight members of the local religious orders assisted in his funeral mass and interment at a cost of 25 livres. There were also two solemn services for Paris for an additional cost of 36 livres.115 Three years later the cantors sang a high mass in honour of the recently deceased Louis-Simon La Boularderie (1674-1734), a former naval officer and distinguished resident of the colony. Celebrated on 18 November 1734, the mass in "Voix Chante" cost 10 livres.116

38 The high masses sung for Boularderie and Paris, to the accompaniment of musical instruments, were exceptional only for their expense. Almost from the initial settlement of Louisbourg, settlers began to distinguish between high and low masses with accompanying singing. On 29 April 1718, François Florenceau, the king’s storekeeper, requested in his will that eight high masses be sung together with another 100 masses to be sung in a low voice.117 In the 59 wills that have survived from Louisbourg during the French regime, roughly one-third of the testators wanted to leave money to the church for the offering of masses, hymns and prayers after their death, though in most cases the amount left to the church for these purposes was to be determined by surviving family members. On his death bed in January 1731, Andre Angr, a Swiss soldier, requested a "solemn service" be sung in the chapel of the hospital prior to his burial. He also left 300 livres to clergy in Louisbourg to "pray for him, his parents, friends and comrades and to sing every Saturday for ten years the Litanies of the Blessed Virgin".118 Four years later, Marie Anne Ponce, a widow, left 760 livres for 366 Requiem Masses to be celebrated from the day of her death until one year later and at the end of the year to hold a "solemn service in the ordinary manner".119 Even those dying as visitors to Louisbourg, such as captain Jean Giraud of the ship L’Aimable Marguerite, wanted to be buried in holy ground with accompanying music to smooth the passage into the next world. On 12 June 1750 Giraud asked for a high mass to be sung at his death and, on the eighth day after his burial, for a service in the chapel.120

Figure Three : An 18th-Century Vielle (hurdy-gurdy) made by Salles and Sons at Caen, Normandy.

Display large image of Figure 3

39 Choral and sacred music were performed every day and were so much a part of peoples’ lives that they were easily taken for granted and were rarely mentioned, except when individuals were nearing death and thoughts of the hereafter were foremost in their minds.121 A specific reference to sacred music in Louisbourg occurred in the will of Louisbourg widow Anne de Galbarret. After leaving money to the church for masses in memory of her late husband and brother in an earlier will, she requested in 1742 that the annual rent from one of her properties be used to pay in perpetuity for a low Requiem Mass with the benediction of the Blessed Sacrament to be celebrated each Thursday afternoon between four and five o’clock with a De Profundis at the end of the Mass.122

40 Sacred music was not restricted only to funerals and solemn occasions. The Te Deum was a central part of public celebrations throughout France and its colonies. Extraordinary observances such as royal marriages, royal births or military victories called for the singing of a Te Deum, usually accompanied by cannon fire and bonfires.123 Thus in 1719, after the victory of King Louis XV’s forces over the Spanish at Fontarabie, a fortified town in the Basque region near the French border, the king ordered that a Te Deum be sung in Louisbourg. The king’s letter stipulated that the superior council was to attend, ceremonial bonfires were to be lit and the cannon were to be fired with all of the accustomed marks of public rejoicing.124

41 The celebrations for the capture of Fontarabie were followed by Te Deums commemorating victories at Phillipsburg in Germany in 1734, the sacking of Canso in 1744 and the capture of Minorca and Fort St. Philippe in 1756. Other Te Deums were sung to celebrate the recovery of Louis XV from illness in 1721, the coronation of the young king in 1722, the birth of twin daughters in 1727, the birth of the Dauphin in 1730 and the birth of the Duc de Bourgogne in 1752. Government officials and the clergy ceremoniously lit large bonfires and the townspeople also put candles and lanterns in windows throughout the town.125 Massive bonfires also offered a focal point for public dancing and singing. Estienne de la Tour, a contractor, supplied 200 bundles of wood for the bonfire commemorating the feast of Saint Louis on 25 August 1743.126

42 Public celebrations such as Te Deums, the carnival and the Feast of Saint Louis, together with French musical traditions, were brought from overseas and adapted to suit a distinctly New World environment. European music was modified as well by the missionaries who sought to convert Mi’kmaq to Roman Catholicism and to ensure that they remained faithful to the church. Sacred hymns had an enchanting allure for the French as well as their native allies. Abbé Pierre-Antoine Maillard, (1710-1762) the missionary of the Mi’kmaq in Cape Breton from 1735 until his death in 1762, understood this. Fluent in Mi’kmaq, Maillard developed an orthography for the Mi’kmaq hieroglyphs and translated the Lord’s Prayer, the catechism and especially ecclesiastical hymns.127 After composing and making books of hieroglyphs, Maillard distributed the works among the Mi’kmaq so that they could easily learn the prayers, the hymns and the instructions of the catechism. The Mi’kmaq, with Mailland’s encouragement, also began to copy the hieroglyphs in order to preserve the hymns and scriptures in Mi’kmaq.128 Numerous missionaries (there were approximately 100 who worked in Acadia during the French regime) and other observers commented on the devotion of the Mi’kmaq and their fondness for singing sacred music.129 Missionary Christian Le Clercq noted in 1691 that the Mi’kmaq had "good voices as a rule, and especially the women, who chant very pleasingly the spiritual canticles which are taught them, and in which they make a large part of their devotions".130 Le Clercq translated some hymns into the Mi’kmaq hieroglyphs, but it was Maillard who improved and completed the orthography in a European style. Like Le Clercq, Maillard admired Mi’kmaq singing. "The majority of the Indian women", he wrote, "have very pleasing and very soft voices, which they know remarkably well how to keep in tune in singing".131 In order to use those voices in the liturgy, Maillard began composing works for the Mi’kmaq language. Writing to Antoine-Louis Rouillé, the minister of marine, Louisbourg Governor Jean Raymond had complimentary words for Maillard’s compositions: "He taught them to praise God in their language and to listen to what they said to him. He has composed a native music and he has made some very beautiful works in that regard".132

43 Maillard noted that the Mi’kmaq women sang during the mass and for morning and evening prayers when the men were away for extended periods hunting for food, especially during the winter.133 The missionaries apparently cultivated their relationships with the Mi’kmaq women in order to encourage them to sing during mass.134 The Mi’kmaq took an active part in singing hymns during two outdoor high masses celebrated in Louisbourg in 1757 and 1758. During the summer of 1757 at least 100 Mi’kmaq and Malecite came to Louisbourg and remained in the town in anticipation of a British invasion. During July, Abbé Maillard, singing in Mi’kmaq, celebrated an outdoor high mass in nearby Gabarus to the accompaniment of Mi’kmaq singers, with hundreds of curious French spectators in attendance.135 The following year, again as a defensive measure against a British siege, Mi’kmaq, Malecite and Abenaki people met in Louisbourg and participated in a ceremonial war dance. As part of the public celebrations, including the arrival of a large French naval squadron, Maillard sang a high mass in Mi’kmaq, accompanied by Mi’kmaq singers.136 The sacred hymns of the Catholic Church complimented Mi’kmaq song and dance and have had a lasting influence on Mi’kmaq culture. Upon visiting Chapel Island in 1815, Bishop Plessis noted that the Mi’kmaq "still have the late Father Mailland’s book of instructions and hymns, and this they copy and hand down from father to son".137 Among the 6,000 Mi’kmaq living in Cape Breton, the majority of whom still speak Mi’kmaq, there are still a few who are literate in the traditional script, and Mi’kmaq prayer leaders still read from hieroglyphic texts on holy days of obligation and at ceremonies of birth, marriage and death.138 Native-language hymns are also sung in Mi’kmaq churches today, a legacy of Maillard’s work during the 18th century and testimony to the faith and perseverance of the Mi’kmaq people over the centuries.

44 Music was a part of people’s everyday lives at all levels of society, with sacred hymns among the French and the Mi’kmaq, courtly dancing among Louisbourg’s high-ranking officials, tavern dances among fishermen and soldiers, and the sounds of whistling, fluting, the playing of Jew’s harps and the drumming of the garrison beginning at sunrise. Dancing and singing, which were part of the cultural identity the French brought to Cape Breton, became even more vital and necessary as people had to provide their own entertainment in a relatively isolated settlement. With darkness approaching at five o’clock in early winter, together with an inhospitable climate, and the lack of female companionship, music and song provided comfort to lonely fishermen, soldiers and officers in the garrison, whose wives and girlfriends remained in France. Prominent Louisbourg officials and their families followed musical taste and tradition in Europe, much like other recent immigrants to North America. Whether composing a ditty, beating a drum or playing for a minuet, musicians, singers and dancers in Cape Breton were always looking back over their shoulder at Europe. Nevertheless, as the Mi’kmaq and French exchanges demonstrate, even as they did so they adapted and modified European music to suit the New World environment.

Notes

Good lads of the Isles who want to go sailing

Don’t go to Newfoundland to shorten your days

There’s nothing but trouble, never any fun,

Risking your hide at sea all the time.

And then when we get there, we have to work

All day without drinking or eating

At night we sleep in a little corner

Under a [sail] on a bit of straw

Then when we get to this wretched country

We start freezing to death in our sheepskins.

We all look like the fellows you see

Playing farces in theatres back in France.

God it’s misery to see us on board,

We don’t have too much bread or drink,

Just rotten cod, and only water to wash it down.

The sailor’s lot is a hard one.

Let’s go back to our Isles; that’s the place to be.

Let’s go see our women and make love to them,

And tell them about the misery people put us through

While they’re having a good time on shore