Articles

Working for Uncle Sam:

The "Comings" and "Goings" of Newfoundland Base Construction Labour, 1940-1945

Steven HighNipissing University

1 "RARELY HAS THE RISK OF WAR TRANSFORMED A COUNTRY SO DRAMATICALLY FOR THE BETTER", wrote Kevin Major in his recent history of Newfoundland and Labrador.1 The Second World War was a turning point for the country in many respects. It signaled a shift in the dominion’s orientation away from Great Britain and towards North America. Canadian and American goods supplanted old British favourites, and traffic regulations requiring automobile owners to drive on the left side of the road were revised to the North American standard. Most importantly, the war brought full employment to a country in desperate need of economic relief.

2 Newfoundland’s close proximity to North Atlantic shipping lanes and to the Great Circle route used for trans-Atlantic aviation made it of tremendous strategic value to the allies. This fact came to the world’s attention with the signing of the famous destroyers-for-bases deal on 2 September 1940.2 In exchange for 50 aged destroyers, Great Britain agreed to lease base sites on the island and in other British territories in the western hemisphere. Soon Newfoundland became one of the most militarized places in North America. The United States built four sprawling bases: Fort Pepperrell on the outskirts of the city of St. John’s; a second Army post, Fort McAndrew, across the Avalon Peninsula at Argentia; the U.S. Navy’s operating base, also at Argentia; and an Army air base, Harmon Field, on Newfoundland’s west coast at Stephenville. These four sites were joined by the Canadian air and navy bases also being built in Newfoundland and Labrador. At the height of the construction boom in 1942, fully 20,000 Newfoundlanders found steady employment on these foreign bases.3

3 The onset of wartime prosperity was met with welcome relief by Newfoundland’s 300,000 residents, who had endured two decades of mass unemployment and widespread destitution. The collapse of the salt fish trade and government insolvency forced the people of Newfoundland to accept the suspension of democratic institutions in favour of a British-appointed Commission of Government in 1934. Yet, the suffering continued unabated. For example, the monthly economic and social reports filed by members of the Newfoundland Rangers, a rural police force formed in 1935, observed many families sinking into debt. Another government study estimated that the average annual income from fishing in 1935 amounted to a meager $135.82.4 Hard times thus forced a large proportion of Newfoundland’s population onto the government dole of six cents per day.5 Widespread poverty, in turn, contributed to malnourishment and a rate of tuberculosis so high, reported one American doctor, that it accounted for one in six deaths on the island.6

4 Yet rural Newfoundlanders were a remarkably versatile and resilient group. They planted gardens, raised livestock, fished and hunted to feed their families. In the off-season, fishers worked in the woods for the paper companies or on the roads for the Newfoundland government. A large number of men also ventured to the mainland in search of higher wages and steady work. Indeed, residents had a long tradition of moving back and forth between wage labour and the often cashless fisheries. There were many fishermen-farmers, fishermen-miners and various combinations thereof.7 Occupational pluralism thus represented a fundamental feature of the Newfoundland labour market.

5 With the arrival of thousands of highly paid American servicemen and civilian construction workers in 1941, problems arose. In Newfoundland in the North Atlantic World, Peter Neary has sketched out the many points of friction or uncertainty that accompanied the "friendly invasion" of Newfoundland: the removal of hundreds of families to make way for the bases, confusion over criminal jurisdiction and customs duties, the spread of venereal disease and the usual brawls and rowdyism on Water Street in St. John’s. However, the most troublesome problem for the Commission governing Newfoundland proved to be the one involving wage rates and labour turnover. To minimize the disruption to Newfoundland fishing, logging and mining industries, the British and Newfoundland governments quietly lobbied the United States to pay the rates already prevailing in the country.8 The Commission also urged fishers and loggers to return to their seasonal jobs in 1941 and again in 1942. These efforts proved partially successful; the resulting high rate of labour turnover on the base construction sites had some unforeseen consequences.9

6 Foreign officers and diplomats interpreted this high rate of turnover as an absentee problem, reporting to their superiors that Newfoundland men were lazy and idle. They were, one concluded, "as a group restless, and given to frequent changes in employment".10 Canadian High Commissioner Charles Burchell likewise blamed this phenomenon on a general indisposition to do continuous work.11 Newfoundlanders, he confidently stated, were simply unused to modern work discipline. The U.S. Consul General in Newfoundland, George D. Hopper, agreed with this assessment, reporting that the island’s male inhabitants had the habit of hibernating for two to ten weeks in the winter months. During this time, he added, they loafed at home until they ran out of money.12

7 These alarming and harsh judgments have found their way into the historical scholarship of the period. The U.S. Office of the Chief of Military History published a volume on North American cooperation that claimed that Newfoundlanders had a "proclivity for long week ends" and refusing to work during the harsh winter weather.13 These often essentialist observations about Newfoundland character have been repeated ever since. Even historians of the caliber of Peter Neary have let these comments stand without comment.14 What is most disturbing about this historiographic trend is that in repeating these claims without questioning their validity or even asking why mainland observers drew these negative conclusions, historians have left the unmistakable impression that this collective portrait was an accurate one. This paper holds that the comings and goings of base construction workers in Newfoundland should not be attributed to loafing or laziness. To the contrary, the high rate of labour turnover resulted, in large part, from the longstanding occupational pluralism of Newfoundland rural communities and from the Commission’s own efforts to convince fishers and loggers to combine base employment with their seasonal work. Wages paid to base workers thus proved too low to keep them on these construction sites year round, but they were high enough to keep them coming back.

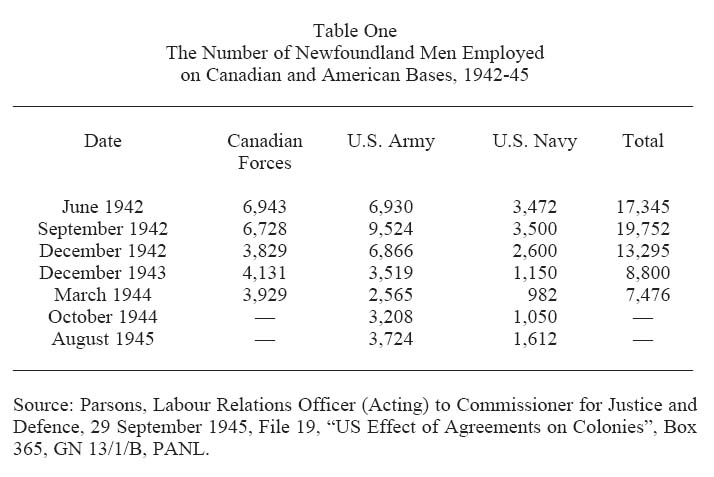

8 The base construction boom quickly transformed Newfoundland’s labour surplus into a labour shortage, particularly in areas adjoining the major bases. As Table One illustrates, a majority of the 20,000 workers employed on the foreign bases worked for the Americans. In September 1942, for example, the U.S. Army employed nearly 10,000 people and the U.S. Navy another 3,500. Fort Pepperrell employed the largest number of Newfoundland civilians, more than 5,000, in November 1941. This was followed by the air and naval bases at Argentia, Harmon Field and Fort McAndrew. In its annual economic and financial review of the island, the American Consul General’s office reported immediate results: the large influx of military personnel had resulted in "large disbursements of funds which modified, at least temporarily, the internal economy of Newfoundland".15 Wages were high and the population was fully employed. Even at war’s end, the foreign bases continued to employ more than 5,000 residents on a semi-permanent basis.

9 Newfoundlanders quite naturally gravitated to job sites closest to home. One of the results of this inclination was the development of five labour catchment areas around key construction sites. Two of these centred on bases being built for the Canadians. The inhabitants of Labrador and the Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland found jobs at the huge Canadian air base being constructed at Goose Bay. Those inhabiting Newfoundland’s north coast or living along the railroad line cutting through the island’s interior found work at the Canadian air bases at Gander and Botwood. Construction of the American airfield at Stephenville in turn drew workers from coastal communities in the southwest corner of the island and from the larger communities to the north such as Corner Brook. However, beginning in Harbour Breton, South Shore residents (particularly those from the Burin Peninsula) caught the coastal steamers east to the U.S. Army and Navy bases at Argentia. This massive construction site also attracted a large number of workers from the Avalon Peninsula. Finally, the Canadian and American bases in the vicinity of St. John’s employed people from the capital and from across the Avalon Peninsula.16

Table One : The Number of Newfoundland Men Employed on Canadian and American Bases, 1942-45

Display large image of Table 1

10 From the moment that the Americans arrived, Newfoundlanders were determined to find work at the bases. But poor winter working conditions, a lack of accommodation and an oscillating demand for labour marred the first months of base construction. After having financed the journey by rail or steamship with credit from local merchants, many hopeful employees had to return home empty-handed in early 1941.17 Joseph Hanrahan of Marystown on the Burin Peninsula, for example, had stayed in Argentia for a week in a fruitless search for work. Some nights he slept under an upturned dory on the beach and on other nights he joined almost 200 others in a coal shed. "There is no doubt about it", reported one Newfoundland Ranger, "the men are keen to get at this work".18 Each day men from the widely scattered communities along Newfoundland’s southern coast made their way to Argentia using "every available means, jackboat and steamer, and even motor boats". As a result, one of the enduring images of construction at Argentia were the dozens of fishing boats moored off-shore. Base workers slept on-board these vessels, finding their way "back and forth to their temporary quarters in dories".19

11 The number of people seeking to work at Argentia was so great, in fact, that the limited number of coastal steamers plying Newfoundland’s isolated south coast proved unable to handle the increased demand. Steamers were filled beyond capacity, making men and women wait weeks or even months for passage. One 1941 report from Bay l’Argent proved typical: "When the S.S. Glencoe arrived here on March 3rd she was filled and could take no passengers, the same occurred again on March 28th when she was again full and had to leave 130 men behind in Fortune Bay. It will be another three weeks before there is another boat east and possibly the same thing will happen".20 As a result, the time it took to travel between coastal communities and Argentia often depended on the availability and frequency of coastal steamers.

12 The foreign bases offered outport residents relatively good wages, a long work week and a ready source of cash. It was thus widely reported that rural Newfoundland was emptied of men: "practically every able bodied man" (Lamaline), "most of the men" (Burin) and "practically everyone who could creep or crawl" (Harbour Breton) had gone to work at the bases.21 Women, young boys and those with disabilities also found remunerative work at Argentia and other American bases. In 1942, 80 women were employed as stenographers, laundresses and waitresses at the naval base at Argentia and another 150 at the adjoining army base. The waitresses typically earned $12.50 per week and lived in special "Girls Barracks" where guards were posted to ensure that men did not visit.22

13 Once construction was underway, Newfoundland Rangers reported an infusion of currency into coastal communities that had hitherto functioned on credit. The large number of residents from Harbour Breton who found work at Argentia, for example, had "brought cash to the majority of families" in the town "who hardly knew before the real meaning of its use or sight".23 This development, as seen in Flowers Cove, was a "novel innovation for the people, as wages or earnings were hereto entirely controlled by the local merchants".24 The American invasion of Newfoundland thus triggered far-reaching social and economic changes.

14 It was suggested by some contemporaries that Newfoundlanders were "dazzled" by the wealth of the Americans and, as a result, they squandered the money that they earned on "luxury" goods instead of investing their wind-fall into new fishing equipment.25 Monthly Ranger reports, however, paint a very different picture. People used their earnings to pay old debts, to make long-needed repairs to their homes and to purchase new fishing equipment. In fact, hundreds of homes in each district received badly needed repairs and a fresh coat of paint. Newfoundlanders also bought foodstuffs and consumer goods that had been beyond their means only a few months previously. An obviously pleased W.R.D. Bishop, a Ranger stationed in Marystown, saw a young man "whose father had been on the relief lists for a number of years past, walk into a store and order a large grocery list, included in which was a sack of sugar. This, I imagine, was more sugar than the entire family had seen for the past number of years".26 Long-suffering families in coastal communities thus attained a higher standard of living than they had been accustomed to over the previous two decades.

15 While this new prosperity was derived in large part from the thousands of jobs created at the bases, other factors were at work: wartime demand had made fishing much more profitable than it had been for decades. The prices paid to Newfoundland fishers in 1943 were 30 per cent above those paid in 1942 and three times those of the best inter-war year.27 Rural families also benefitted from multiple incomes. The exodus of adult men from coastal communities freed lower paying jobs for the very old, for the very young and for women. Ranger Bishop of Marystown noted that it had become a common sight during his patrols to see small children of "tender ages" on the flakes drying fish. Older men were similarly reported to be employed casting for capelin. For their part, women found increased work and higher wages on the bases and in their home communities. While women always had an important role to play in the family economy, the fact that they now earned wages proved significant. The U.S. Consul General complained of the increased wages for "lower groups" such as domestics. An experienced housemaid, he lamented, "could be had two years ago for ten dollars per month, but at present one finds advertisements offering thirty dollars as a starter".28 The same held true in smaller communities outside of St. John’s.

16 In reviewing the reports of the Newfoundland Rangers it becomes clear that it is impossible to give an exact accounting of how many Newfoundlanders worked at the U.S. bases, as men and women were "coming and going" daily.29 Members of practically every outport family spent some time working at the bases from 1941 to 1943. Along the south coast, this meant that every steamer saw "a certain number of men going and each successive steamer brings a further number back".30 Understanding the reasons for this constant movement to and fro requires an examination of the question of wages.

17 A deceptively simple question emerged over the winter of 1940-41: what should the wage rates be for local labour on the new American and Canadian bases? Many Newfoundlanders hoped that the Americans would agree to pay the higher wages common on the mainland. Newfoundland employers, however, insisted that local rates be respected. The wage question represented one of the most troublesome problems created by the friendly invasion. According to Newfoundland Governor Humphrey Walwyn, base contractors from the United States by paying higher wages threatened to "upset the whole labour system".31 The government, he reported, was "alert to prevent this disturbance" and "succeeded in keeping rates of wages for unskilled workmen down to a reasonable level". The government’s efforts proved so successful that the labour costs were just a fraction of what the United States had originally budgeted. According to the financial records of Newfoundland Base Command, the U.S. Army saved as much as two-thirds of its projected labour costs, or $18.5 million (U.S.), in the first 16 months alone.32

18 In effect, the British and Newfoundland governments pressured the United States into lowering the wages it paid local labour. For their part, the British advised Washington of the "difficulties which might arise if the rates of pay to be paid by the United States authorities to the laborers employed in the construction of the bases were to be substantially in excess of the local market rates".33 In January 1941, these efforts secured a verbal promise from the Americans to consult the colony or dominion before setting wages.34 The Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, directed that a prevailing wage clause be inserted into all construction contracts on 28 January.35 But unbeknownst to the British, President Franklin D. Roosevelt quietly ordered the U.S. Army and Navy to pay "top scale" rather than "average scale" wages.36 That is to say that the American armed forces would pay local labour at a rate of pay comparable to the best local employers. The decision to pay slightly above the going rate was designed, perhaps, to make the Americans appear more generous than the British. It proved to be a brilliant strategy as it secured labour in a tight market and won the Americans considerable public approval.

19 Having apparently induced the U.S. government to agree to a prevailing wage policy at the leased bases, the British government subsequently denied having anything to do with this decision.37 When questioned in the House of Commons, the British government publicly disavowed any responsibility. Officials in the Colonial Office knew otherwise. The "position of Great Britain and the United States", one wrote, stemmed from a fear that "considerable labour trouble" might arise if the American bases paid more than the going rate.38 Another key official in the Colonial Office, Arthur Creech-Jones, even suggested that reactionary colonial governments had induced the U.S. to pay a prevailing rate that was far too low.39 He had a point. The wage rate policy, if vigorously enforced, had the effect of prolonging Depression-era wages in British territories hosting American bases. This was especially true given that the prevailing wage standard acted more as a ceiling than as a floor.

20 While these diplomatic notes crossed the Atlantic, base construction was already underway in Newfoundland. This early start meant that the wage issue was also being negotiated on the ground. Sir Wilfrid Woods, the career British civil servant appointed Commissioner of Public Works, took the lead. According to confidential biographical data compiled by the U.S. Consul General, Woods was a "conservative in every meaning of the word".40 He often argued, for example, for the saving of money and for the most efficient expenditure of funds. Woods’ conservativism would profoundly shape Newfoundland’s wartime wage policy.

21 On 17 January 1941, an American engineer at Argentia asked Newfoundland to furnish him with the prevailing rates of pay. Commissioner Woods telegraphed the following response: "Rates of pay for unskilled labour twenty five cents important that this should not be disturbed".41 This curt message was quickly followed by a more lengthy explanation of Wood’s thinking on the subject:The Government is necessarily interested in the rates paid by the Americans and Canadians who are just now becoming active in this country. The Newfoundland Government cannot afford to pay more than 25¢ per hour for unskilled labour and it is important that this rate should not be upset by the new employers. There is bound to be dissatisfaction when different rates are paid and as I have already said, this Government is not in a position to increase its rate.42To ensure that there was no mistaking his wishes, Woods informally let it be known to the visitors that their wisest course for the time being was to pay the government rates which were all but unchanged from the 1930s.43

22 Despite the adamant position adopted by Woods with the newcomers, the Commission had yet to decide on its wage policy. To clarify matters, Woods circulated a memorandum on 17 January calling on the government to discourage the visiting forces from paying more than the government rate of 25 cents per hour for unskilled labour:I feel sure, however, that unless we encourage other large employers to keep in step with us the problem will get out of hand. If the Canadians and Americans, under the pressure of the urgent character of their work, adopt a higher standard of wages than that of other good employers there will be a sudden demand for higher wages all round.44Woods found it "neither practical nor sound" for the Commission to declare itself neutral in the matter. He justified his stance as a necessary step towards full employment. Higher wages, he warned, would convince employers to employ fewer people. Woods also expressed the fear that a sharp increase in wages might "kill" the vulnerable mining, forestry and fishing industries. It was a widely shared assumption in official circles that the wartime bubble of prosperity would burst once the foreign bases had been completed.

23 Woods also responded to those who had suggested to him that there was no great need for the government to control wages. The higher wages traditionally offered by the paper companies should not, he insisted, be cited as proof that the military authorities could pay substantially more than the "general level" without disturbing it. As both Bowater’s Newfoundland and the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company hired mainly permanent local residents in Corner Brook and Grand Falls respectively, they had little effect on the wages paid outside the two company towns. By contrast, the base construction sites would attract thousands of Newfoundlanders from across the island. Hence, whatever rates were established by the military authorities would soon become the standard for all other employers: "The argument will be irresistible that anything less than the Canadians and Americans are willing to pay must be too low; that this Government should treat its own labour at least as well as the Canadians and Americans treat their labour in this country".45

24 Woods urged the Commission to keep its role secret. He feared that if word got out it would invite public criticism and bolster trade unionism in Newfoundland. His advice to the other appointed commissioners governing the dominion was characteristically blunt: "I think the wisest course of action at this stage is to refuse point blank to reveal any discussions we may have had or may hereafter have with the Canadian and Americans on the subject of wage rates on the grounds that these are confidential". In the meantime, he hoped that the foreign employers would be convinced to respect the government rates. The other commissioners concurred and directed Woods to act generally upon the lines described in his memorandum.46

25 The government’s behind-the-scenes efforts to hold down wages did not go unnoticed by the hundreds of Argentia residents forced to make way for the bases in the middle of the winter. Many of these people resisted relocation until such time as they were compensated for their lost homes and property. Area residents also insisted on the right to negotiate wage rates directly with the United States "without Government interference".47 When asked to clarify the government’s position on the wage issue at a public meeting in Argentia, Woods would say only that the question was one of the utmost importance to the future economic welfare of Newfoundland. In what would become a familiar refrain, he added that the government had no power to fix the rate of wages paid by the Canadian and American authorities. This claim, while technically true, did not acknowledge the influence the Newfoundland government exercised.

26 As Woods expected, the government’s effort to hold down wages dove-tailed with the desire of the United States and (especially) Canada to minimize construction costs. Lieutenant Colonel Philip G. Bruton, the District Engineer for the Army Corps of Engineers, asked Woods on 27 January to review the rates proposed by the U.S. and make "such modifications" as necessary "to bring them into conformance with the local prevailing rates".48 While this consultation was consistent with the newly made promise to the British, Roosevelt’s secret order to pay slightly more than the going rate soon came into play.

27 Paying the local prevailing rate no doubt enjoyed a certain logic, but it presupposed the existence of a Bureau of Labour that maintained accurate wage statistics. No such institution existed in 1940s Newfoundland. Woods later conceded to the Royal Canadian Navy that there was simply no method of establishing a "fair wage rate" for labour outside the government’s payroll.49 Newfoundland’s own labour relations officer, a position created in 1942, similarly confirmed that without properly collected and compiled statistics it was impossible to be sure what the prevailing wages were.50

28 How then did Newfoundland determine the wage standard for a myriad of occupational job-types? In effect, the government adopted the existing wage schedule of the Department of Public Works as the standard. This stand proved advantageous on two counts. First, the occupational categories in the department’s wage schedule approximated those required at the base construction sites. But more importantly, as the government wage rates tended to be among the lowest in the country, the policy allowed the government to save money. Thus, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers inquired into government and private sector wage schedules, the government deliberately forwarded only its own (lower) wage rates.

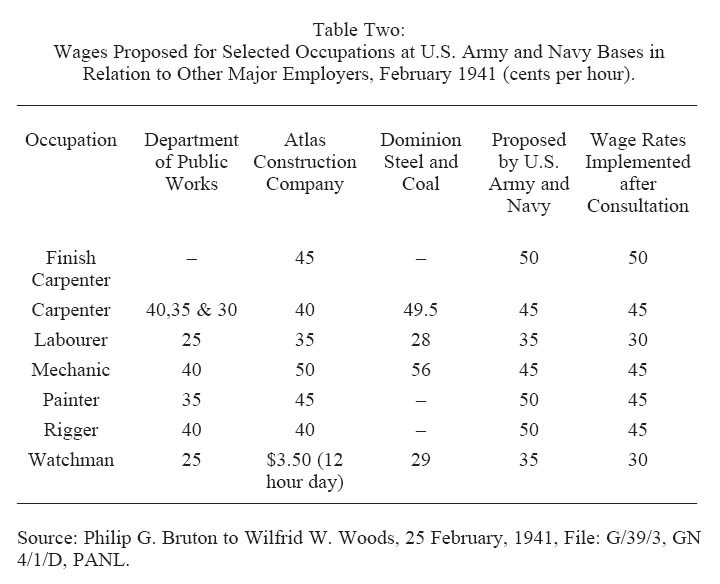

29 In spite of these efforts, the Army Corps of Engineers obtained a copy of the wages paid by Dominion Steel and Coal at its Bell Island mine and those paid by the Atlas Construction Company at the Canadian air base at Gander, using them to justify a somewhat higher schedule than that of the Newfoundland government. Of 57 occupational categories, only 11 paid as poorly at the Department of Public Works. As Table Two shows, the Americans proposed to pay more, at times significantly more, than the Newfoundland government.

30 In response, Wilfrid Woods arranged a meeting with Lieutenant Colonel Bruton in yet another bid to hold down wages. Bruton agreed to roll back wages for a number of occupational classes including drillers, labourers, painters, powder men, rigger foremen, riggers and watchmen.51 The most important of these changes was the agreement to lower the hourly wage of unskilled labourers, the single largest occupational group, from 35 cents to 30 cents per hour. The downwardly revised American wage schedule was released to the public the following day. The Commission also recommended the maintenance of regional wage differentials whereby government employees were paid more in St. John’s than in rural Newfoundland. The resulting patchwork of government rates for road work proved to be arbitrary in the absence of reliable wage data. Even before the war, road managers sometimes found it difficult to justify to their employees why those living on one side of a particular line should earn one rate and those on the other side another.

31 On this matter, however, the Commission of Government failed to convince the U.S. to conform to past practice. U.S. Army and Navy base contractors agreed instead to make all wage rates uniform across Newfoundland.52 Lieutenant Colonel Bruton told Woods that this decision could not be avoided as the base contractors required a great deal of labour drawn from distant points of the island. Not surprisingly, Woods was not pleased by this turn of events. In adopting a universal standard for the whole island, even after the Canadians had agreed to respect Newfoundland’s regional rates, the Americans created a situation where their wages greatly surpassed those formerly predominating outside St. John’s.

32 The Newfoundland government’s attempt to regulate wages failed in another important respect. To his future regret, Woods had not foreseen the employment of large numbers of women at the foreign bases. As a result, the wage schedule created in early 1941 did not include female wage categories such as waitresses, laundresses and clerical workers. This oversight worked to the advantage of many women as the U.S. could set its own wage rates. Over the course of the war, the Newfoundland government had trouble filling vacant female jobs and repeatedly complained about the high wages paid to base clerical staff.

Table Two : Wages Proposed for Selected Occupations at U.S. Army and Navy Bases in Relation to Other Major Employers, February 1941 (cents per hour).

Display large image of Table 2

33 Public demands for higher wages grew louder in light of ineffective or non-existent government price controls. Wage earnings were thus quickly eroded by wartime inflation. The cost of living in Newfoundland, always higher than in either Canada or the United States, increased another 57.8 per cent between 1938 and 1945.53 Those residents on fixed incomes such as the wives of servicemen were the hardest hit.54 Unskilled labourers also found their take-home pay of decreasing value. With the exception of messenger boys, they were the lowest paid male occupational group on the foreign bases, accounting for almost 40 per cent of the total payrolls.55

34 It was not surprising, then, that labourers would be the first to demand higher wages. They faced an uphill battle, however, as the entire wage schedule was scaled upwards from the hourly rate for general labour. In effect, a raise for labourers meant a raise for all male employees. Raucous public meetings, ultimatums and loosely organized unions at Argentia and Fort Pepperrell followed the publication of the first wage schedule in February 1941. Delegates from the many small trade unions in St. John’s, for example, resolved that there should be a 40 cents minimum.56 One unidentified labourer wrote to the Evening Telegram stating that Newfoundland was the only place in the British Empire where wages had not risen since the onset of war:Our American and Canadian friends are paying the lowest rates of wages for unskilled labour. We know that the rates of pay in the United States for general labour is much higher than the above. Ninety five cents an hour was the rate quoted in one of our newspapers a few weeks ago. Surely we in Newfoundland are worth at least forty cents an hour for general labour.57

35 The Evening Telegram also reported that workers at Argentia were greatly dissatisfied with the rates of pay. To defend their collective interests, upwards of 200 labourers formed the Federation of Workers Union in March 1941. All of the union’s officers, save one resident of Fox Harbour, belonged to the Argentia area. In his report of the meeting, Constable James Heaney wrote that these were very well educated and sensible men. They were, he concluded, "very good men for the positions if there must be a union".58 The new vice-president of the union, James Houlihan, reportedly claimed that only the Commission of Government was opposed to higher wages.

36 While government officials privately complained that the initial wages paid by the Americans were "generally higher than we pay", ordinary residents had expected a much higher rate of pay.59 In light of public criticism, a revised wage schedule appeared in March 1941. The most notable change was the sub-division of the old labourer category. Under the new scale, labourers could earn as much as 35 cents an hour. Emphasizing the significance of these changes, Lieutenant Colonel Bruton told the Evening Telegram that as soon as a labourer showed adaptability he would be placed in the senior wage category. Carpenters were likewise divided into two groupings. In practice, the sub-division of job classifications meant an increase in pay for most workers. Newfoundland labour was nothing if not adaptable.

37 Government officials in the meantime developed contingency plans in case the March 1941 changes did not satisfy organized labour. In a second memorandum on the troublesome problem, dated 29 April, Woods informed his colleagues that Newfoundland trade unionists continued to insist on a 40 cents per hour base rate for unskilled labour. Having discussed the matter with Lieutenant Colonel Bruton, Woods believed the government was faced with a decision:I imagine that the Canadians and Americans might fall into line if the Newfoundland Government set 40¢ per hour for common labour as a minimum wage for its own employees, but I think the consequences of such action would do harm to Newfoundland’s economy. Certainly it would be unreasonable for Government to take this action without consultation with the larger employers throughout the country. My own view is that the Government should be in no hurry to alter its own rate of 25¢ an hour for common labour on road work and similar jobs.60If the unions persisted with their demands, Woods argued that the government could afford a nominal ten to 15 per cent increase. If this offer failed to satisfy, the government was prepared to "give protection" to those workers willing to break the strike.

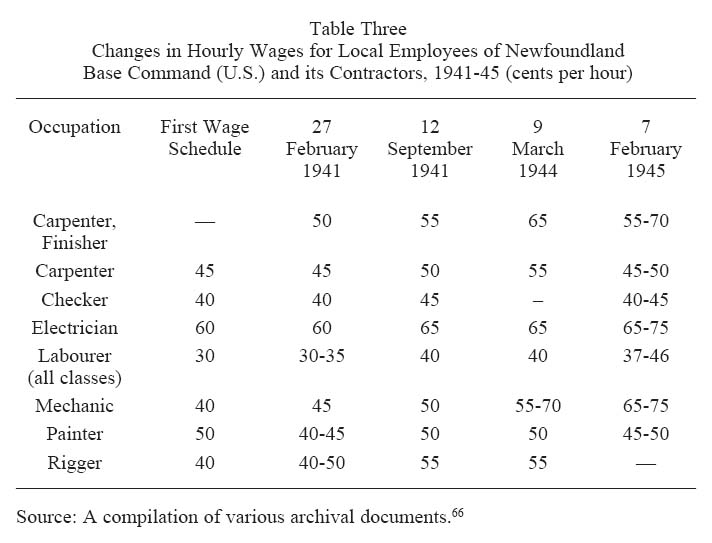

38 The wage issue refused to go away. Complaints could still be heard in June when the secretary of the Newfoundland Board of Trade visited Argentia.61 H.T. Renouf reported serious dissatisfaction among many local employees. The inferior wages, Renouf heard, had the effect of giving Newfoundlanders an inferiority complex in relation to their highly paid American and Canadian co-workers. In the busy summer months of 1941, about 1,000 labourers walked off their jobs at Fort Pepperrell for better pay. They now wanted a raise from 35 cents per hour to 50 cents. George D. Hopper reported that the U.S. Army Commander had explained to the strikers that the rate of pay was a "matter of law" and that base contractors could not unilaterally grant wage increases without a proper investigation of the prevailing rates and a decision from Washington.62 These objective criteria were a thin veil indeed. Hopper momentarily feared that the strikers would have to be removed from the base by military escort, but this "extreme measure" was avoided in view of "possible political repercussions". By the following day, almost all of the strikers had returned to work. As table three shows, the strike nonetheless contributed to the U.S. decision to revise the wage scale upwards to 40 cents in September 1941. Only then did the Department of Public Works follow suit.

39 Over the course of the war, the Commission of Government faced criticism from both business and labour. An August 1941 editorial in the Newfoundland Trade Review, for example, highlighted the concerns of the business community:There is a danger for this country along the economic lines it is traveling today. People in certain sections are earning a scale of wages much greater than they had ever known – and spending it as fast as they make it. In most cases these higher wages are due to the presence of forces of occupation in this country for, in spite of protests heard that attempts have been made to keep down wages, it is clearly evident that the scale paid by the occupation forces is above the level that had existed here previously, or is still being paid by local concerns.63To the annoyance of the government, some base contractors told their Newfoundland employees that they would like to pay higher wages, but the Commission of Government would not let them. One such incident led Gander truck driver Malcolm Moss to write Commissioner Woods to determine whether or not the government had deprived him of a pay raise:On behalf of the truck drivers working with the Belmont Construction Company I would ask if you could make us acquainted with the reason why us Newfoundland drivers are not entitled to the same rate of pay, as a Canadian driver, working side by side with us, and doing the same work, yet getting fifteen cents (.15¢) per hour more than us. We Newfoundland drivers are getting forty five cents per hour. When the question of more pay, five cents (.5¢) more per hour was put to the company, they refused because the Newfoundland Government had fixed a standard rate for truck drivers at forty five (45¢). This I think is very unfair if it is correct. We have to pay one dollar per day for board…. If us Newfoundland Drivers would get more money, per day, I cannot see that it would affect the government of our country in any way but would bring more money into circulation. For my part I am a married man, naturally I want to support my wife and family. Now that the price of food stuffs and clothing has soared to a high level, it demands a very good wage to make both ends meet.64In responding to Moss, the government assured him that "no rate has so far been fixed by the Government. . . . except in the case of its own truck drivers".65 But rumours to the contrary continued to circulate. In December 1943, the editor of the Twillingate Sun privately called on the government to clarify this "old charge": "There has been talk of our men working on Base Construction not getting pay enough according to what Contractors and Supers would pay. The Commission of Government is blamed for making agreements re. lower wage scales. I hope you can give something for publication to refute this".67 Claiming that open discussion on this question would not be in the "public interest", Woods advised a fellow commissioner not to respond: "silence is the best policy".68

Table Three : Changes in Hourly Wages for Local Employees of Newfoundland Base Command (U.S.) and its Contractors, 1941-45 (cents per hour)

Display large image of Table 3

40 The rippling effects of the base construction boom temporarily disrupted almost every sector of the economy. An unsettled labour market resulted in a situation where workers came and went as they pleased. Accordingly, the high turnover rates prevailing on the bases plagued virtually all other employers of labour. Even long established firms such as the Buchans Mining Company and the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company reported that the turnover rate in 1942 was the highest ever.

41 Production in the mining industry fell far below capacity due to an inability to recruit and retain experienced labour. Although the wartime market for copper, lead and zinc was unlimited, the Buchans Mining Company operated at only 76 per cent capacity in 1942.69 The company complained of a distinct shortage of experienced men, who had to be replaced by others with no mining or milling experience. These new hires would remain on the job for only short periods. A confidential letter written by Buchans Manager G. G. Thomas, and intercepted by wartime censors, outlined the problems faced by the company:The building of defense bases has made labor very scarce, the pity of it is that we have lost so many experienced men that we are down to about 75% capacity which means a considerable reduction in the production of lead, zinc, and copper – it is something we here cannot help – it does seem a pity when they are so badly needed. We have increased wages 20% or so but still it does not get us men – actually we get less work than before – our tons per man shift have fallen off – our costs have of course increased – there is a ceiling on prices of metals. I can only hope that with summer coming on we may get more men.70The Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation similarly reported a scarcity of qualified personnel at its Bell Island mining operation.71

42 Stiff competition for labour likewise made it difficult for the paper companies to find sufficient numbers of men to work in their woods operations. The basic wage rates for seasonal loggers were set by the Woods Labour Board, a government created body composed of the representatives of management and the woods labour unions. Annual agreements on wages were considered "final and binding".72 The minutes of the Woods Labour Board reveal the upward pressure on wage rates during the war, increasing fully 62 per cent from 1939 to 1944.73 The problem of wage rates in Newfoundland was a knotty one for the paper companies. A.W. Bentley, Woods Manager for Bowater’s, revealed at one meeting that:In Canada and the US the Company does not decide the scale of wages, this is decided by the Government, because Canada and the US industry is controlled by their Governments with a definite policy. Here we are trying to operate on a peace time basis and trying to sell our products to countries who have arranged their economy on a war time basis.74Collective bargaining, albeit under the auspicies of the Woods Labour Board, resulted in a situation where there were only informal wage controls in Newfoundland and often stringent controls on newsprint prices elsewhere. The paper companies were caught in between.

43 Bowater’s Newfoundland began to experiment with new technologies and cutting strategies in late 1941. The shortage of dock workers at the Corner Brook piers encouraged the company to mechanize the unloading of pulpwood. A crane proved to be far more efficient than labour gangs using tackles and slings.75 The general manager also reported that the company shifted the location of some of its woods operations from remote interior areas to coastal areas. This new strategy allowed many Newfoundlanders living in outports to log from the comfort of home and thus avoid paying camp fees for room and board. Yet the company’s success in using tugs, barges and booms to transport the wood to Corner Brook was mixed, as the first booms proved to be insufficient against the high winds and waves.76

44 The company’s willingness to experiment extended to other aspects of its woods operations. Unable to recruit a sufficient number of men, Bowater’s proposed as early as October 1941 to employ women in the wood camps. Starting in the vicinity of Stephenville, on Newfoundland’s west coast, where the labour shortage was particularly grave, the company proposed to operate "family camps" in addition to the regular (male) camps.77 Despite the shortage of men, the government strongly opposed the proposal. After the Commissioner of Natural Resources P.D.H. Dunn had his staff examine the legislation, he was disappointed to find that nothing prohibited the employment of women in the woods. Dunn emphatically believed that women could never become "loggers". He urged Bowater’s Newfoundland to limit itself to the employment of married women in the cookhouse or the office, and only in those cases where their husbands also lived in the camp.78

45 In a June 1942 radio broadcast designed to recruit men for the paper industry, Dunn spoke to the scarcity of loggers on the island. He first appealed to the patriotism of his Newfoundland audience: "I tell you here and now that every man who takes a day off from construction work unnecessarily is making a present to Hitler and may be contributing to the downfall of the United Nations". Absenteeism, he estimated, caused one-fifth of the available labour output to be lost. There would be no labour shortage in the woods operations of the paper companies, he reasoned, had they stayed on the job. In making his urgent appeal for woods labour, Dunn went so far as to imply that the very survival of the two mills was at stake: "Without these mills Newfoundland would be very much poorer".79

46 Despite the best efforts of Dunn, the paper companies once again failed to find sufficient workers. There was an estimated 3,000 person short-fall in the spring of 1942. Newfoundland Rangers thus reported that most of the wood contractors did not get all their wood off for the spring drive.80 In fact, the mill owners were said to be unable to pay men enough wages to "induce them to give up work at Argentia to work in the woods".81 In January 1943, the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company reported that the great shortage of labour had resulted in a much reduced cut of only 50 per cent of that which was expected.82 This shortfall convinced the Commission of Government to introduce national registration as a means of appraising the labour-power of Newfoundland.

47 With higher wages now available on the base construction sites and the cost of living soaring, some unions escalated their demands for better wages. A strike at the Buchans mine and a work slow-down – involving a refusal to work nights or on Sundays – on the St. John’s docks forced the government to act. The Defence (Avoidance of Strikes and Lockouts) Regulations adopted in June 1941 enabled the Newfoundland government to intervene to settle disputes. Soon thereafter, the government adopted a second law – the Defence (Control and Conditions of Employment and Disputes Settlement) Regulations – that empowered it to appoint Trade Dispute Boards.83 Once appointed, these boards settled disputes through binding arbitration on the St. John’s docks, in a fluorspar mining operation at St. Lawrence, in the St. John’s wholesale and retail trade, among carpenters and in the iron ore mines of Bell Island. In each instance, wages were increased.

48 The comings and goings of rural people reflected the occupational pluralism that had long been a feature of life in Newfoundland and Labrador. Thousands of base workers returned home to cut wood, prepare the garden, make home improvements or to celebrate Christmas and New Years with their families. Few Newfoundlanders shifted their attention to construction work entirely. Rangers in coastal Labrador, for example, reported that residents incorporated base construction into their seasonal round. A May 1942 report from Cartwright, Labrador was typical: "Those going to work [at the Canadian Air Base at Goose Bay] were mostly trappers finished with their trapping for the season, and those returning were mostly men coming home to fix up their fishing gear and post for the salmon season".84 In many ways, the coming of the foreign armed services simply added "base work" to the occupational mix.

49 Despite many dire predictions about a return to mass unemployment, virtually all of those displaced at the end of the construction boom in 1943 quickly found work in the woods and mines of the country as well as on the still-booming mainland.85 While the wartime labour shortage temporarily disrupted the island’s mining and forestry industries, it had a more long-lasting effect on Newfoundland’s fisheries. The payment of wages to workers other than in currency had been prohibited in England since 1831, but the "truck system", whereby workers were advanced goods supplied from the shop of the employer, continued to be commonly practiced by merchants in Newfoundland’s coastal communities more than a century later.86

50 Work at the bases, and the increased earnings that came with it, nonetheless resulted in substantive modifications to the seasonal round. A study of the fishing communities of inner Placentia Bay, for example, found that base employment resulted in a decline in subsistence agriculture and in decreased holdings of livestock and poultry.87 Fishers who had previously lived in their outport communities year-round and had tended livestock and gardens when not fishing, abandoned these activities to work for the Americans. This deviation from longstanding seasonal labour patterns proved lucrative; the average income of fishers in the area increased from $135.43 in 1935 to $641.51 in 1945.

51 A similar pattern emerged in the agricultural settlement of Markland, 40 miles inland of Argentia. Markland was the largest resettlement scheme undertaken by the Commission of Government during the 1930s. In 1934-35, 120 families made a new start there with the government’s assistance.88 Fields were cleared and schools, churches and homes were built. The American occupation of Argentia, however, effectively ended Markland’s chances for long-term farming success. As residents took jobs at the Army and Navy bases, fields were abandoned, fences fell and livestock was killed off. The only reason that the resettlement scheme at Lourdes on the Port au Port peninsula on Newfoundland’s west coast fared better was due to the fact that residents could commute to their new jobs at the U.S. base in Stephenville.89 But here, too, few fields were being cultivated.

52 The effect of base employment on the fishery was uneven as fishers showed their preference for certain kinds of economic activity over others. The quantity of codfish landed in 1941 was "one of the lowest on record" and failed to rebound to a normal level the next season.90 While the inshore fishery weathered the war surprisingly well, the Bank and Labrador fisheries were disrupted by the temporary diversion of fishers into base construction.91 The war at sea also played a part. Newfoundlanders, it seems certain, preferred to work the inshore fishery in their own boats than work as "sharemen" – who received a share of the season’s catch – on off-shore Grand Banks or Labrador schooners. As a result, merchants had great difficulty finding crews. In the community of Grand Bank, which was the main centre for the Banks fishery, some schooners had to quit before the season was over once the crews left to work at Argentia.92 Only those firms that paid their crews a monthly wage in legal tender were able to continue operation.

53 To dissuade fishers from working at the bases, the government issued a public warning in May 1941, claiming that the Americans did not need unskilled construction labour; fishers need not apply.93 It soon became apparent, however, that the Commission had grossly underestimated the future demand for unskilled and semi-skilled workers on the bases. In the months that followed, the enormous drawing power of these bases was such that fish merchants began to complain bitterly about men abandoning the off-shore fishery in order to work construction. One such complainant, L.M. Hyde of the Change Islands off the north coast, accused a rival company of sending men to work in base construction even though they were needed at home: "This is a fishing settlement, always has been and we do not consider it good enough for our fishermen to be induced to temporarily abandon it for a year or two when all facilities are here available for the continuous prosecution of both the shore and Labrador fisheries".94

54 This complaint triggered a series of written exchanges within the Department of Natural Resources about the nature of the problem at hand. While Commissioner J.H. Gorvin acknowledged that the government could not interfere with the men’s "right of choice of occupation", he nonetheless believed that if the credit system could be cooperatively organized, the men would opt to stay in the fishery.95 His Chief Cooperative Officer, N. MacNeil, however, advised the Commissioner that there was, in fact, little the government could do about the "exodus". Instead, he urged Gorvin to establish in the vicinity of the bases, the necessary machinery that would enable these men to save as much money as possible: "Although fishing is the traditional occupation of the outport people . . . there has been involved in the prosecution of this industry so much hardship and meager returns that the fishermen will gladly leave their fishing boats if any other alternative presents itself. There is also the point that the scarcity of cash as a result of barter methods has enhanced the value of money in the eyes of the fishermen". Any attempt to dissuade these men, he concluded, would prove "futile". The opportunity to earn cash wages at the base construction sites was not to be missed.96

55 On 17 February 1942, the newly appointed Commissioner of Natural Resources, P.D.H. Dunn, issued another "Important Notice" concerning Newfoundland’s economic outlook. Hoping to convince fishers to stay in their boats, Dunn confidently predicted that the high employment levels on the base construction sites would continue only until June and that 90 per cent would be laid-off by November. Dunn urged fishers to avoid construction work: "Those fishermen who have already left the fishery or who may intend to leave it for other employment should consider their position very carefully".97 An earlier draft of the warning had included even stronger language, but it was dropped for fear that the United States government might have accused the Commission "of hindering their war effort".98

56 Within weeks of the government’s warning, it emerged that employment levels at the bases would remain at peak levels until mid-1943 and decline gradually thereafter. To the consternation of many, the Americans even had to appeal for 500 additional labourers to replace those persuaded by Dunn’s message to return home.99 Beneath the headline "Somebody Blundered", the Evening Telegram now called on the Commission to explain this mistake to the public: "Somebody has certainly been misleading the people of this country and in fairness to all the true facts should be forthcoming".100 The public’s anger was fed by a suspicion that the government was doing the bidding of the fish merchants. While nobody had a ready answer for the Telegram at the time, archival records indicate that the government may have deliberately distorted the situation in order to shore up the troubled fishery.101

57 Eventually, however, construction work tapered off and the majority of fishers returned to their boats. A total of 18,000 men were occupied in fishing in 1943, 5,000 more than the previous year. But they did so on the basis of a new cash economy. With the truck system in ruins, the Newfoundland government felt it was time to abolish the practice. Legislation was drafted to prohibit the payment of wages of workmen save domestic servants, loggers and "sharemen" who were engaged in the prosecution of the fishing voyage, otherwise than in money.102 This Act, adopted in April 1944, confirmed that the changes that had already been effected in coastal communities around the island would become permanent.

58 The coming of the Americans brought both prosperity and dislocation to Newfoundland. Although historians have noted the debate over the wages paid to local civilians employed by the U.S. Army and Navy, there has been no sustained study of the issue. No connection has hitherto been made between the Newfoundland government’s drive to hold down wages and the high rate of labour turnover experienced on the bases and in primary industries. The government’s partial success in keeping base construction wages to a minimum, combined with its public appeals to return to fishing and logging, encouraged Newfoundlanders to combine base work with other traditional activities. As a result, thousands of Newfoundlanders moved back and forth between the base construction sites and their homes, depending on the season. The government’s determined effort to encourage a return to the seasonal fisheries and to the woods operations of the paper companies had the desired effect. It was achieved, however, at the expense of the visiting forces. The constant comings and goings of their Newfoundland employees were interpreted by the visitors as an absenteeism problem. Had the Commission of Government elected to regulate base construction wages through a labour board, as it did in the woods industry, the turnover rate might not have been as high, and foreign observers might have been less likely to assume that the unstable work force reflected certain intrinsic qualities of the Newfoundland character.

Notes