"A Reluctant Concession to Modernity":

Alcohol and Modernization in the Maritimes, 1945-1980

Greg MarquisUniversity of New Brunswick

1 LIQUOR LAWS IN THE MARITIMES UNDERWENT significant changes in the years following the Second World War. Amendments to alcohol control legislation in all three Maritime Provinces proceeded in the common direction of increased liberalization, though at an uneven pace and with local variations. These changes in the regulation of alcohol consumption were a form a "boosterism" supported by a conjuncture of social, economic and cultural forces. Changes in public morality, increases in disposable incomes and greater attention to consumer choice were among the underlying reasons for the shift in public attitudes, but in the post-1945 era the liberalization of liquor laws was also closely associated with the idea of modernization. Much like modern highways, urban renewal, industrial parks, expanded higher education, access to improved health care and cheap electricity, changes in alcohol regulation were seen as part of a larger transformation of regional society. The new provisions were seen as characteristic attributes of a prosperous post-war North American society based on a relaxed secular morality and increased spending power and leisure time. Alongside the discourse of anti-modernism that promoted an image of the Maritimes as a refuge from the North American mainstream, the Maritimes also participated in a contemporary narrative of modernization that emphasized economic development, technological advance and cultural change.1

2 Regional studies are necessary to a fuller understanding of how society has regulated and responded to controversial substances such as alcohol, tobacco and narcotics.2 A regional framework for alcohol regulation is as problematic as any other comparative topic on the Maritimes.3 Nova Scotia and New Brunswick had abandoned prohibition in favour of state control in the 1920s, while Prince Edward Island retained a form of prohibition until 1948, and Nova Scotia permitted licensed premises in the late 1940s, more than a dozen years before New Brunswick. Nonetheless, the three provinces shared several important characteristics in respect to the place of alcohol in regional society at the end of the Second World War. Their liquor laws, particularly those dealing with public drinking, were among the most restrictive in Canada; temperance groups, although declining in numbers, retained considerable political and symbolic power; the rate of alcohol consumption was below the national average and the percentage of abstainers was above the national average4 – 51 per cent among adult Maritimers compared to 33 per cent among adult Canadians in 1948.5 Finally, in the 1940s and 1950s, provincial treasuries were relatively more dependent than those of other provinces upon liquor revenues.6

3 The central question governing alcohol in Canada after 1945 was liberalization. Under the "control" regimes established on the provincial level starting in the 1920s, no one had an absolute right to consume beverage alcohol. Liquor commissions held a partial or full monopoly on the sale of alcohol. Elaborate controls were put in place, including provincially-owned liquor stores and self-policing by private beer parlour operators, to ensure moderation, public order and state revenue protection.7 The control era, which lasted into the 1960s, represented a transition stage between prohibition and the age of alcohol as a largely depoliticized leisure commodity, for which individuals assumed the associated health and safety risks.

4 It is tempting to confine discussions of support of liberalized liquor laws to an instrumentalist approach that stresses groups with immediate interests: brewers, distillers, hotel and restaurant owners, and certain trade unions. In the public debate on alcohol, there was little organized support for liberalization outside of these groups. Yet general support for liberalization was evident in editorials, publications and lobbying efforts on the part of local and provincial boards of trade, the Maritime Provinces Board of Trade and the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council (APEC).8

5 In temperance rhetoric, pressure for liberalization emanated not from the public but from the self-interest of the "liquor traffic" and its allies, including corrupt or misguided politicians. In reality, opinion polls indicated that the public increasingly supported the removal of restrictions on alcohol. This misreading of public sentiment helped ensure the continued decline of dry organizations following the introduction of government control. The Maritime temperance movement, represented by the Sons of Temperance, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and other voluntary organizations, lacked the numbers and organizational base of the 1910s and 1920s, although drys could still rely on a network of Baptist and United Church ministers and congregations into the 1950s and 1960s.9 The United Church until the early 1960s counselled voluntary total abstinence and advocated nationalization of the alcohol industry and a ban on liquor advertisements.10

6 One organized constituency that supported liberalization, the region’s alcohol industry, was limited in scope. By the late 1940s, Maritime breweries were producing less than four per cent of Canada’s beer and employed fewer than 350 people.11 Canada’s wine industry was concentrated in Ontario. In the 1950s, a sacramental winery operated at Rogersville, N.B., and by the early 1960s a small apple wine business existed in the Annapolis Valley. A decade later the Kentville firm was joined by Abbey Wines of Truro and Normandie Wines of Scoudouc.12 Nova Scotia’s McGuiness Distillery, which took over bulk rum handling from the provincial liquor commission in the late 1950s, was situated at Bridgetown. A wave of industrialization and governmental assistance in the 1960s would add a rum distillery at Richibucto, a new Oland’s brewery in the Saint John area and a Moosehead brewery in Dartmouth. These facilities represented a considerable addition to the industrial tax base.13 The Maritime breweries had loyal customers, in large part because of the policies of provincial liquor commissions which marketed draught and bottled beer through liquor stores, Legions and taverns. Protective provincial policies amounted to barriers to trade. Brewery workers were unionized and relatively well paid, and brewery executives, who in past decades had maintained a low profile because of the sensitivities of temperance organizations, were well regarded in business, political and media circles. In the early 1960s Victor Oland was president of the Halifax Board of Trade and vice-president of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce. In the late 1960s Moosehead’s Philip W. Oland was chair of the Saint John Port and Industrial Development Commission and a member of the Atlantic Development Commission.14 The strategy used by alcohol producers since the 1930s to legitimize their industry centred on the economic benefits of investment, jobs, raw materials purchases and revenues to government. Like tobacco companies, brewers, distillers and wine producers never tired of reminding government and the press that the state, not the private sector, took the lion’s share of every dollar spent by the consumer on their products.15

7 A second constituency that stood for liberalization in the 1940s and 1950s were military veterans. The Canadian Legion was an important social institution not only in urban neighbourhoods, but also in small towns and rural areas. By the early 1970s in New Brunswick, more than 80 local branches counted 30,000 members.16 As part of a network of private clubs, Legions had enjoyed liquor privileges prior to the Second World War. In 1939 and 1944, the PEI provincial command of the Canadian Legion of the British Empire Service League had urged the repeal of prohibition (in the name of "British freedom") and the adoption of a liquor control statute.17 During the war, tens of thousands of Maritimers, nearly half the eligible male population, had enlisted in the armed forces, and military bases had been expanded or built across the region. The Canadian military was a wet service. For Prince Edward Island, the construction of air bases meant wet canteens in a province with statutory prohibition.18 Whether or not they joined the local Legion (not all branches served alcohol), veterans as a social group enjoyed considerable status in the late 1940s and 1950s. Once pension, education, housing and medical benefits were secured, the provincial and local Legions turned to social activities and community projects. Organized veterans were key non-economic advocates of liberalized liquor laws, and the local legion often was the only place in town where members and guests could drink outside the home. The national magazine, The Legionary, carried advertisements from distilleries and breweries.19

8 A third group, organized labour, was one of the most consistent voices of liberalization. Although trade unionists had been an important part of the early 20th-century social gospel movement that had helped to secure prohibition, for the most part labour was wet. Union leaders had spoken out in favour of moderation and government control in the 1920s. During the Second World War they had criticized federal restrictions on beer. Although PEI’s labour movement was limited, in 1945 Charlottetown workers appealed to democratic principles for an end to prohibition, which they equated with rule by a bigoted, feudalistic minority.20 In 1948 Nova Scotia labour groups, which supported beer parlours for the "working man", met with the provincial cabinet to discuss liquor laws. The Nova Scotia executive of the Trades and Labour Congress of Canada lobbied for improved quality of product for consumers and the right to sell beer in union clubs. The Nova Scotia Federation of Labour (NSFL), pressed for better quality beverages, reduced prices and a more open system for taverns and beer parlours. The NSFL, and the United Mine Workers, called for taverns owned and operated by the state, a suggestion one cabinet minister dismissed as socialistic. In the 1940s in Nova Scotia and the early 1960s in New Brunswick, the provincial governments formalized input into liquor policy from organized labour.21

9 The tourism and hospitality sector was the largest constituency that stood for liberalized alcohol controls. By the late 1950s, municipal, provincial and federal politicians, journalists, business groups, service clubs and other organizations viewed tourism as an important part of the region’s economic salvation. Earlier discussions of tourism had focused on hunting and fishing, or on attracting American and Central Canadian elites to resorts and lodges.22 Mass tourism would benefit not only the hospitality industry, but also the retail and public sectors. The strategy of attracting larger numbers of visitors from the United States, Ontario and Quebec dovetailed with other contemporary booster projects, such as hard-surfaced roads and highways. Middle-class families on vacation would tour the region by automobile, and cars became a unit of measurement in the developing industry. Infrastructure modernization in the case of the Trans-Canada Highway and the "Roads-to-Resources" programme provided federal support of highway and road construction designed to benefit not only mining, forest industries and the fishery, but also tourism. The Maritimes, according to the Atlantic Advocate, earned close to $140 million from tourism in 1964.23

10 A cursory look at tourism marketing in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s suggests that accessibility, low cost, scenery, outdoor recreation, climate, history and friendly "locals" dominated the imagery. Marketing played on familiar themes: salmon streams, covered bridges, provincial and national parks, natural attractions such as New Brunswick’s Reversing Falls, the fictional tales of Evangeline and Anne of Green Gables, the Cradle of Confederation, Nova Scotia bagpipers and Scottish kilts, the Cabot Trail, Nova Scotia fisherfolk, the schooner Bluenose, friendly Acadians and the Annapolis Valley Apple Blossom Festival.24 In other words, the tourist was not enticed to the region with promises of alcohol; the debate on liberalization was primarily an internal affair. However, the argument that liberalized access to alcohol was part of the necessary infrastructure for tourism was not new. It had featured prominently in the debates and plebiscites on alcohol in the 1920s. National Breweries Limited, which provided free tourist guide books to New Brunswick had advised Nova Scotia Premier E.N. Rhodes that booze attracted thousands of American tourists and convention delegates to Quebec. Supporters of a "progressive Halifax" in the 1940s argued that beer parlours and restaurants serving drinks with meals would benefit tourism.25 The Nova Scotia Innkeepers’ Guild in 1948 lobbied for the right to serve wine and beer in hotels and tourist resorts regardless of local option votes.26 In the 1950s elements within the hospitality sector supported cocktail lounges, serving mixed drinks made from spirits, to support tourism. As one member of Nova Scotia’s South Shore Board of Trade explained to Premier Angus L. Macdonald, for patrician American visitors the cocktail was "the most important drink of the day".27

11 One influential voice promoting liberalization in the post-war years, the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council, adopted a broader analysis based on marketing, responding to outside opportunities and responding to tourist families as consumers. Founded in the mid-1950s, the organization was quick to establish a tourism committee. In the late 1950s APEC promoted hospitality as the region’s industry of the future. In the words of Professor William J. Dalton, post-war prosperity had brought cheaper travel, paid vacations and greater disposable income. In 1957 Dalton argued that tourism was an undeveloped sector that could help close the regional income gap identified in the recent Gordon Report. In the competitive world of North America’s family tourism, "natural attractions" in themselves were not enough. Middle-class tourists expected inexpensive, yet modern facilities and comforts, such as constructed campsites, housekeeping cottages and trailer parks. These informal travellers also demanded "the same liberties they enjoy at home" in terms of beverage alcohol. Liquor licences, to repeat the argument of hotel owners, would allow proprietors to upgrade facilities. Unfortunately, Dalton noted, Prince Edward Island had opened liquor stores only in 1948, and in New Brunswick, outside of Legions and other private clubs, liquor by the glass was illegal. This was a barrier to development. Echoing the hospitality industry, Dalton identified "more realistic liquor laws" as a necessary precondition for economic development.28 Similarly, D. Leo Dolan, former head of the Canadian Government Travel Bureau, wrote that more than 55 million Americans lived within driving range of the Maritimes. Relaxation of "antiquated methods" of alcohol control, he noted, would be "a progressive and civilizing step" that would help boost tourism.29 In 1959 APEC, which had conducted a survey of Canadian alcohol control regimes, called on the Nova Scotia government to appoint a commission to investigate the relationship between liquor laws and tourism. A year later APEC’s president, addressing the Nova Scotia Innkeepers’ Guild, warned that the industry was being held back by "public apathy", shoddy accommodations and poor dining facilities. According to Michael Wardell, the British editor of the Fredericton-based journal Atlantic Advocate, "busybody restrictions" interfered with not only visitors, but also the majority of Maritimers. American tourists resented having to drink "without their woman-folk, in places reserved, like public lavatories, for ‘men only’".30

12 Appealing to a new way of doing tourism had tremendous currency in Maritime public life in the 1960s. A New Brunswick entrepreneur described family tourism as a positive alternative to "the smokestack syndrome". A similar message was found in the 1960 Rand Report on Nova Scotia’s coal industry, which had recommended federal development of Fortress Louisbourg and the Cape Breton Highlands National Park to offset job losses in mining. The fact that the majority of tourists who reached the region in the 1960s hailed from Central Canada did not detract from the basic argument: consumers in Ontario were accustomed to licensed restaurants and hotels, to nightclubs and lounges and to relatively numerous government liquor stores and private beer stores. Residents of Quebec enjoyed similar privileges, plus a 40-year tradition of buying beer in corner stores [wine became available later].31

13 A number of tourism and development advocates were ambivalent or hostile towards a "wide open" approach to alcohol licensing and sales. A number feared that regional quality of life would suffer from over-commercialization, homogenization and "Americanization". New Brunswick Progressive Conservative organizer Dalton Camp commented in 1964: "if we must solicit tourist business by glorifying drinking alcohol through the pink hibiscus, then the industry is in serious trouble".32 Yet for the press and provincial governments, cautious liberalization seemed both desirable and inevitable. Tourism, furthermore, was a central tenet of economic diversification and regional development by the late 1960s, forming one of the cornerstones, for example, of PEI’s Comprehensive Development Plan. By the early 1970s the sector was estimated to be worth $100 million to the four Atlantic provinces, and New Brunswick and Nova Scotia each were attracting more than one million visitors yearly.33

14 The media, which supported development, was another voice of liberalization. Expressed in letters to the editor, newspaper and magazine stories and news coverage, this support was framed in terms of not only direct tourism benefits but also the individual rights and lifestyle of Maritimers themselves. Philip More, in the Atlantic Advocate, reflected a cosmopolitan, permissive attitude towards alcohol and rejected attempts by the minority to control the morality of the majority: "The present laws controlling liquor, wine and beer hereabouts are unfortunately subject to pressure from relatively small and narrow-minded groups". He concluded that "no body or group has the right or privilege to try to make it difficult to buy an honest and lawful drink in pleasant surroundings".34 Although per capita and regional income lagged behind the rest of Canada, in the post-war era Maritimers enjoyed an improved standard of living and were spending more on alcohol and other leisure items.35 Wardell editorialized in 1961 that "the people of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, who together spend more than a million dollars a week on liquor and who represent a large majority of the electorate, are entitled to a law they can accept and respect".36 A decade later, a correspondent from Newfoundland praised St. John’s for its many taverns, extended drinking hours, hip entertainment and go-go dancers (all benefits of "a tolerant society"). By Newfoundland standards, Maritime liquor restrictions were "uptight" and reflected negatively on "the quality of everyday life" on the mainland.37

15 By 1960, supporters of liberalization were able to recognize signs of change in the public regulation of alcohol. In Nova Scotia a royal commission was appointed, and the election in New Brunswick of a Liberal government under Louis Robichaud38 was followed by the appointment of a similar commission. Modelled on the more ambitious Bracken Commission which examined liquor policy in Manitoba in 1954, these inquiries reflected what contemporary Halifax cartoonist Bob Chambers symbolized as the tendency for contentious social and economic problems to be investigated by commissions of experts.39

16 Nova Scotia, host to a strong temperance tradition that dated back to the 1820s, had ended prohibition in 1930 following a plebiscite in which government control had triumphed. Province-wide prohibition under the Nova Scotia Temperance Act had existed since 1916, but local option votes made most of the province officially dry prior to the First World War. The new Liquor Control Act reflected the post-prohibition compromise position that alcohol was a dangerous commodity, and no liquor stores were opened in areas that supported prohibition in the 1929 plebiscite.40 The local vendors who had distributed alcohol for medicinal purposes from 1916 to 1930 were replaced by government liquor stores. Between 1930 and 1948 the number of stores grew from under 30 to 45. The Nova Scotia Liquor Commission (NSLC) justified expansion on the need to undercut bootlegging. However, store hours were restricted and many Nova Scotia communities (and three entire counties as of 1956) were not served by stores. Private clubs such as the Legions and military messes afforded one outlet for social drinking, but public consumption was illegal and bootlegging continued. In 1946, writer Dorothy Duncan noted that because Halifax lacked saloons and taverns, men congregated on streetcorners. In Wolfville, in the heart of Baptist country, Duncan was reminded that there were no nightclubs "east of Montreal".41 In 1948, there were only two liquor stores in the entire Annapolis Valley.42

17 Halifax and other urban centres in 1946-47 staged straw-poll plebiscites that revealed support for sale of beer by the glass. As part of a review of alcohol policy, the Nova Scotia government had engaged in unprecedented public opinion polling. The surveys suggested a tendency towards liberal attitudes, especially for off-premise drinking. In 1946, one-quarter of those polled did not consider beer and wine as intoxicating. The surveys indicated that Nova Scotia men wanted additional liquor stores, taverns and beer in private clubs, whereas women were more conservative. In a province that had been one of the pillars of organized temperance, those who would ban the sale of liquor outright declined from 20 per cent in 1945 to only 12 per cent in 1947. Private clubs were slightly more acceptable than hotel taverns and stand-alone taverns, although the latter still enjoyed an approval rating of 57 per cent.43

18 The 1948 amendments to Nova Scotia’s liquor law, opposed by only two Members of the Legislative Assembly, permitted sale of beer and wine in restaurants and beer only in taverns. Prior to their introduction the Liberal caucus had divided on the issue. Following a fact-finding mission to the West, Geoffrey Stevens, minister in charge of the Liquor Control Act, made the basic recommendations that formed the draft legislation.44 In the spirit of the political compromise of 1930, and following the example of Manitoba, licensing would be subject to local option plebiscites. Requests for plebiscites had to emanate from municipal councils or from petitions of residents, and votes had to be at least five years apart.45 The Nova Scotia Temperance Federation (NSTF) was unsuccessful in attempts to secure amendments that would have allowed communities to vote out liquor stores once they had been established.46

19 In the political process that produced the first legal public drinking establishments in three decades, the language of moderation and gradualism was noticeable. Introducing a bill to allow beer and wine by the glass, subject to local plebiscites, Stevens promised that the measure would "bring down consumption of spirits". A graduated gallonage tax promised to prevent the creation of "beer barons" by draining off excess profits to the province. Pro-tavern forces also claimed that more outlets would lead to less consumption and drunkenness. These arguments were rebutted by the Sons of Temperance and the NSTF, which warned that overall alcohol consumption levels would rise.47 The wet forces in Halifax, who recalled 19th-century reformer Joseph Howe’s criticisms of prohibition, depicted the tavern as a "social asset", where a working man could enjoy a glass of beer in "respectable surroundings". The citizens’ committee for a "no vote" included the president of Dalhousie University, former Premier A.S. MacMillan, industrialist L.E. Shaw and the president of the Maritime conference of the United Church of Canada. Its campaign literature and advertisements repeated the classic temperance arguments of a century or more. A third group, backed by labour, called for public ownership of taverns, with profits devoted to social services. The July 1948 plebiscite in Halifax resulted in a majority of 5,000 for taverns. The first tavern was the Sea Horse, which sold local beer at 35 cents a quart.48 Dartmouth held no vote on the issue. Drys prevailed in Westville, Springhill and Digby, but in industrial Cape Breton, Sydney and North Sydney were the only towns to reject taverns.49 Between 1951 and 1958, in nine municipal votes for licensed premises, drys prevailed in eight. In the lone wet victory, Sydney voted for taverns but against licensed dining rooms.50

20 Local option served to limit the spread of licensed premises, and municipal zoning kept them away from middle-class neighbourhoods. By the late 1940s taverns were largely confined to industrial Cape Breton (17) and Halifax (14), with one each in Parrsboro and Chester.51 The law was amended in 1951 with a provision that 20 per cent, not 10 per cent, of electors in a municipality had to petition for a plebiscite on taverns, licensed hotels and government stores. Requests for plebiscites on stores could also originate with municipal councils. Liquor could not be served in restaurants on Sundays. Licences for all premises, including private clubs, were issued by a "tavern" committee, chaired by a county court judge and including one representative of labour (three of the four original members were abstainers). That licence decisions were politically sensitive was indicated by the fact the committee in practice reported not to the liquor board, but to the cabinet. Prior to the 1948 changes, private clubs such as Legions technically did not sell beer or spirits to members; rather members maintained supplies on the premises and were charged a "corkage" fee.52 Clubs, which included golf, yacht and curling clubs, now were allowed to sell beer to members, and serve spirits from members’ own supplies. They also were exempt from the local option rule.53

21 Many areas of Nova Scotia remained officially dry, especially in terms of public drinking, and the province’s per capita consumption rates remained well below the national average.54 Despite the wishes of the provincial Innkeepers’ Guild, which in 1947 had lobbied for licensed dining rooms and lounges in hotels, few such establishments were licensed. The hoteliers had good reason to be interested, as in other parts of Canada bar profits were a greater percentage of hotel receipts than room rentals. Polite culture, such as travel writing, offered sanitized views of drinking that clashed with police and court records. For example, when Maritime author Will Bird stayed overnight in Sherbrooke, Guysborough Co. in 1949, he was offered "cocoa and cookies". As the Innkeepers’ Guild admitted, thirsty guests who relied solely on liquor store purchases were left to drink in their hotel rooms, with often negative results for other guests and staff.55

22 By the early 1960s, the provincial liquor commission operated close to 60 retail outlets. Yet, as the Dominion Brewers’ Association complained, the ratio of retail outlets to population was significantly below the national average, the beer was warm and restricted hours made it difficult for many working people to make purchases.56 Outside of urban areas, Nova Scotians were cool to public drinking spots. Amendments in 1954 that permitted the sale of tobacco, soft drinks, light refreshments and the ubiquitous pickled eggs created slightly less austere premises. The Bracken commission, which had investigated liquor control systems in other provinces, found little public support for allowing women into Nova Scotia’s taverns. The fact that so few taverns were located in hotels, in contrast with the situation in Ontario and western Canada, reflected the NSLC belief that most hotels were below standard. In the early 1960s the liquor commission licensed 38 males-only taverns, 13 dining rooms and more than 200 non-profit private clubs, including 81 Canadian Legions.57

23 Gradually, support grew in urban areas for other types of licensed premises. This was justified not to increase consumption or proliferate bars, so much as to offset the supposed detrimental atmosphere of "noisy, smoke-filled taverns . . . . not conducive to sensible, well-mannered drinking".58 Other concerns were abuses by private clubs, such as selling beer on Sundays or to minors and non-members, or operating beyond a non-profit capacity.59

24 In 1960 the Progressive Conservative government of Robert Stanfield appointed a royal commission under lawyer Frank Rowe to examine "the whole field" of the manufacture, sale, distribution and consumption of alcohol. The commission held hearings in several towns and received more than 100 briefs, a majority of them expressing temperance viewpoints. In addition, the commissioners visited western and Central Canada and New England to study control systems. The commissioners explained that in a free society "public interest and the general welfare of the people" must be decided "by the people themselves through an expression of majority opinion".60

25 The temperance and church organizations which appeared before the inquiry were fairly predictable in their recommendations. According to Rowe, drys, either organized or individual, believed themselves to be defending "the social, moral and spiritual interests" of Nova Scotians. In terms of legislation, they recommended either the status quo or turning back the clock on alcohol sales, plus more aggressive prosecution of forms of bootlegging. The NSTF attributed demands for liberalization to the selfishness of vested interests. The WCTU and the Sons of Temperance, predictably, called for strict enforcement of the Liquor Control Act and no new outlets. All temperance advocates dismissed the tourism argument as a red herring.61

26 The major churches were not unanimous in their official views. The Halifax Ministerial Association demanded a major clean-up of taverns and expressed concern about the prevalence of liquor at social functions ( liberal opinion pointed out that restrictions created "bottle under the table" practices). United Baptist and United Church leaders registered the strongest objections to liberalization, suggesting that the public good had to triumph over individual rights. Roman Catholic officials took no part in the hearings. The Social Service Council of the Nova Scotia diocese of the Church of England expressed traditional Anglican skepticism towards prohibition, dismissing total abstinence as unrealistic, and calling for treatment of alcoholics, an improvement to "depressing taverns" and the promotion of beer over spirits. Other than the WCTU, the only major women’s organizations to make submissions were the Presbyterian Women’s Missionary Society and the United Baptist Women’s Missionary Union.62

27 Although mainstream temperance could count on vocal minority support, it had lost its monopoly on alcohol expertise. For example, although a summer school of "alcohol studies" organized at Nova Scotia’s Pine Hill Divinity College in the late 1950s attracted adult learners from across the region, it was criticized for perpetuating outdated prohibitionist ideology. The media, politicians, bureaucrats, liberal Protestants, organized labour, social workers and the public in general were more impressed by the scientific approach of the alcoholism movement, which viewed alcohol abusers as victims of a medical condition, not the dupes of an evil "liquor traffic".63 Although not based on science, the self-help Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) movement enjoyed similar prestige. AA appeared in the region in the 1940s and had at least 30 chapters in the province by the time of the Rowe inquiry.64

28 Business groups also were consistent in promoting their particular agendas. The brewers repeated their complaints on NSLC beer pricing and distribution. The restaurant industry proposed that only "high class" establishments, where food sales would always surpass liquor sales, should be licensed. Restauranteurs and hotel owners resented having to compete in the conference and catering business with private clubs. Hotel and motel owners opined that an expanded hospitality sector would augment municipal and provincial tax coffers. Boards of trade recommended longer hours for liquor stores in order to facilitate travellers. The commissioners, paradoxically, regretted that almost all the pro-liberalization briefs came from companies or organizations that stood to gain financially, yet they rejected the temperance claim that liberalization was driven primarily by economic forces.65

29 The briefs and testimony of organized labour employed the language not only of class, but also of consumer rights and the public interest. The Nova Scotia Federation of Labour denounced the existing liquor law as archaic, the product of government failing to resist a vocal minority. Consumers deserved home delivery of beer, cold beer in government stores and an end to local option. Both the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees (CBRE) and the Halifax-Dartmouth Labour Council (HDLC) voiced concerns over corporate profits in the alcohol sector. The HDLC counselled against licensed premises controlled by breweries or distilleries, urged registration and monitoring of liquor company agents, supported price regulation and advocated locally-owned distilleries. Both the CBRE and HDLC supported general liberalization, such as abolishing individual purchase permits and local option, allowing product advertising and legislating a non-discrimination clause for patrons of licensed premises. No labour body, or any other group, advocated full access to taverns for women.66

30 The Rowe report proposed an updated statute that would bring Nova Scotia more into line with the rest of Canada. Gender discrimination aside, equal rights was a strong message of the report. The tourism argument, according to the commissioners, had been overstated. Their specific recommendations included a licensing board independent from the NSLC, dining room and cocktail lounge licenses for hotels and restaurants, special club licenses with permission to sell spirits, beverage rooms for men only, and new local option provisions.67 Unlike PEI’s 1948 reforms, government would not seek the will of the people through a plebiscite. Following the release of the report, a committee chaired by Attorney-General A.G. Donohue prepared draft legislation. Individual Protestant ministers and the NSTF appealed to the committee and the government to avoid any relaxation of the existing law. According to the NSTF, 40 per cent of Nova Scotians were abstainers and up to 60 per cent opposed taverns, cocktail bars or other licensed premises. Reverend Eaton of the NSTF advised that "this is no time for catering to our indulgences and pleasures". Both Conservative and Liberal members of the Assembly denied temperance allegations that the contemplated amendments were being promoted by the "liquor interests".68

31 The Liquor Control Act of 1961 set up a liquor licensing board and retained local option provisions for adding (but not removing) government stores in a municipality. Local option, common in other regions of Canada, was the Rowe report’s concession to the temperance forces. In licensing areas without licensed premises, the earlier plebiscite rules applied and the onus for initiating a vote rested with wets, not drys. Where voters had previously endorsed licensed premises, no further votes were required for additional businesses. The tourism industry scored one victory: resort hotels that catered primarily to visitors were exempt from local option. The amendments also broadened the variety of on-premise licences: clubs, taverns, beverage rooms, restaurants, dining rooms and lounges. The age of the cocktail lounge had finally arrived. Women, furthermore, could be admitted to "ladies beverage rooms", separate sections in taverns for women and male escorts. Beverage room licences were granted only to hotels. The first beverage room opened in 1963 in Halifax, and by 1970 the number had crept up to three. The Rowe commission had recommended against this last change, but had urged the licensing authorities to improve the atmosphere of taverns, which under the 1948 regulations appeared to have been designed "exclusively for drinking".69

32 Prior to the early 1960s, New Brunswick also had maintained a "liquor control" regime since provincial prohibition had ended in 1927. The Intoxicating Liquor Act had been introduced as a "temperance" measure that would end bootlegging, allow moderate consumption, restore respect for the law and capture revenues for the public treasury. The Act established a system of retail outlets but permitted no public drinking establishments. The New Brunswick Liquor Control Board (NBLCB), although officially an independent entity, like its Nova Scotia counterpart was important in provincial patronage matters. Party loyalists were provided with jobs, trucking, fuel and supply contracts and leasing agreements for buildings. Liquor companies, like other businesses, contributed funds to political parties. According to a Nova Scotia party "bagman", prior to the 1970s brewers, distillers and wine manufacturers paid "tolls" to the ruling party on each bottle or case of alcohol sold.70

33 In New Brunswick, "government stores" sold packaged liquor – beer, wine and spirits – that was stored behind counters. Customers had to fill out order slips for their purchases. Unlike Nova Scotia, there was no local option provision; the board supposedly determined the number of outlets on the basis of population and local sentiment as expressed by political elites. The NBLCB supplied the network of stores from three central warehouses, and in the early years operated a mail-order home delivery service. Hours of sale were limited. As in Nova Scotia, liquor stores closed during the early afternoon on Saturdays and all day on Sundays.71

34 Following the Second World War, rumours circulated that the government would authorize sale by the glass or open bottle in order to expedite tourism. The provincial tourism association supported cocktail lounges in hotels and resorts in order to help counter a perennial New Brunswick problem: visitors passing through en route to PEI and Nova Scotia.72 It was impossible to drink draught beer in a beverage room or a glass of wine with a meal in New Brunswick until the early 1960s. But many New Brunswickers had access to Legions and other private clubs, which enjoyed a quasi-legal recognition from the NBLCB. There were no licences, only written or verbal "permissions" granted by the commission.

35 Changes to liquor administration had been a promise of the successful Liberal election campaign of 1960, and Louis Robichaud received strong support from northern New Brunswick and Acadian areas which were more liberal on alcohol issues. The Tories had inherited an outdated statute which had been jealously guarded by temperance organizations, evangelical churches and successive premiers. The RCMP and municipal police found it difficult to regulate not only bootleggers, but also close to 200 private clubs. In keeping with its election pledge, the new Liberal regime appointed an investigatory commission which included a labour leader, two judges and two lawyers, but no clergy or representatives of temperance organizations.73

36 New Brunswick’s Bridges report was released in the fall of 1961, just as Nova Scotia was implementing its legislative changes. The major recommendations closely resembled those of the Rowe report. They included the creation of a separate commission responsible for licensing and inspections; licensing of private clubs, taverns, dining rooms, hunting and fishing lodges and trains; additional liquor stores; the right of status Indians to purchase liquor and limited advertising by liquor companies. The temperance recommendation for a local option provision was rejected.74 New Brunswick’s new Liquor Control Act took effect in 1962, with a number of licences granted in time for the start of the summer tourism season. The province now had a framework for licensed clubs, restaurants and taverns, although women could not be admitted to the latter. Taverns were dismal, utilitarian facilities, usually located in business or industrial zones of urban communities.75

37 According to connoisseur Stanley Mills, these reforms, however modest, were an encouraging sign that New Brunswickers were exploring "the pleasures of moderate social drinking", supposedly a European custom, in contrast to the Canada’s "crude excess of drinking merely to get drunk".76 This liberal opinion viewed the region’s lingering temperance traditions as an anachronistic embarrassment. Furthermore, the province’s drys, by closely monitoring the operation of the system of government control introduced in 1927, had created a "guilty drinker" phenomenon. As public drinking prior to 1962 was illegal, thirsty New Brunswickers had to buy bottles of spirits and wine or cases of beer from government stores and consume them in private (or in fields, alleyways, dance halls and gravel pits). Mills labelled Robichaud’s policies, which still contained many vexatious restrictions, "a reluctant concession to modernity". Liberal discourse, shared by the managers of Saint John’s Admiral Beatty Hotel and the Riviera Restaurant, explained that more open liquor laws would lead to less binge drinking and less public intoxication.77 Wardell blamed not Maritime drinkers but temperance forces identified with evangelical Protestant churches for sustaining "an era of make-believe, hypocrisy and lawlessness" which gave the Maritimes some of the highest per capita rates of arrests for public intoxication in Canada.78

38 In Prince Edward Island, according to the law prior to 1948, alcohol was available only as medicine.79 For the first half of the century, the Island had been under provincial or federal prohibition regimes. Prohibitionists such as John Linton of the Canadian Temperance Federation attributed PEI’s "favourable social conditions", such as low rates of juvenile delinquency, crime and divorce, to its liquor legislation.80 The PEI Temperance Federation enjoyed a special relationship with the ruling party. One sign of this was its access, through the premier’s office, to the records of doctors and their alcohol prescriptions. In the early years beer below 2.75 per cent alcohol content had been exempt, and authorized vendors dispensed alcohol for bona fide medicinal or sacramental purposes. The Island, long admired by North American prohibitionists as a glorious holdout against "moderation", began to loosen up its alcohol statute and regulations in 1945, when individuals with a doctor’s prescription "script" and a permit could buy one case of beer or bottle of spirits per week. In part the strategy was meant to undermine the entrenched practice of making illegal moonshine. In 1944 Premier Walter Jones had argued that Islanders were abusing the prescription system and that the amount of legal liquor sold in the province was surpassed by illegal quantities. Prior to the amendment, Protestant church and temperance organizations submitted their protests to Premier Jones. The 1945 amendment was marked by a constitutional crisis, as the lieutenant governor, who had associations with the provincial temperance federation, had refused to give assent to the bill. The measure passed following the appointment of a new royal representative.81

39 In 1948 PEI became the last province in Canada to abolish prohibition in favour of a government control regime. According to Edward MacDonald, although the anti-liquor forces, clustered in evangelical churches, remained vocal, and the ruling Liberals included prohibitionists, the Island’s dry law had been protected by inertia as much as by ideology.82 Following ratification by the electorate, the Temperance Act established a commission in control of liquor stores. In keeping with the amendments of 1945, residents with permits could purchase one 24-ounce bottle of spirits or one case of beer each week; an inexpensive tourist permit allowed for four bottles of spirits or four cases of beer or a combination thereof. During the 1950s, tourists purchased more permits than residents, which seemed to counter the assertion of one Women’s Institute that visitors came to "get away from the open flow of liquor". In 1949-50, the Temperance Commission’s five vendors earned a gross profit of three-quarters of a million dollars. An important part of provincial revenues, alcohol spending became a target for concerned temperance advocates. As in Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick beginning in 1962, there was no home delivery of beer. The vendors were closed at night.83

40 The lack of public drinking premises, specifically beer parlours, on PEI reflected an important characteristic of regional alcohol sales: a high percentage of spirits (62.5 per cent for PEI in 1960) as compared to beer and wine.84 Political realities meant that private clubs, as in neighbouring provinces, enjoyed special privileges. In 1954 the Temperance Commission authorized special permits for 16 Legions, eight military clubs and seven non-profit clubs.85 The statute was amended in 1952 to allow customers to buy their four weekly rations at one time each month, and in 1960 quantity restrictions were abolished. A court ruling on the status of private clubs forced the government to enact a regular licence regime in 1964.86

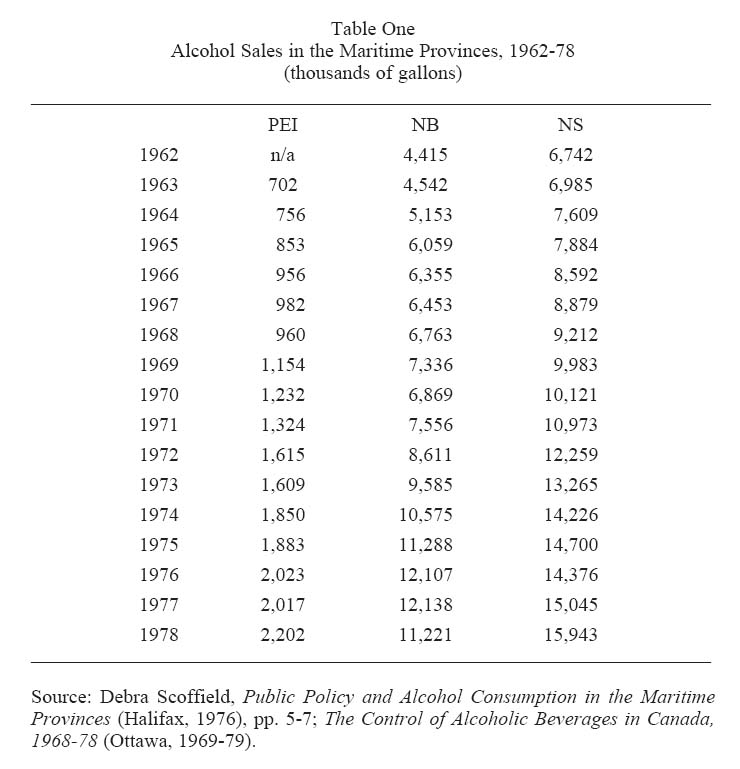

41 Until the 1950s, liquor commission reports in the Maritimes were apologetic when discussing the matter of increased sales; government control, after all, had promised to limit consumption or at least cause "a more temperate use of alcoholic beverages".87 By the early 1960s, the apologetic tone was gone. Beginning in that decade, and continuing into the 1980s, provincial governments followed a Canada-wide trend of implementing more liberal liquor laws. The prediction of 1930s and 1940s temperance groups that liberalization, including greater numbers of licensed premises, would lead to increased drinking, seemed to be realized. Per capita consumption was rising, with increased numbers of women and youth imbibing. By the mid-1970s, three out of five Atlantic Canadians admitted to using alcoholic beverages.88 Consumption per capita in Nova Scotia more than doubled between 1945 and 1978. In Halifax-Dartmouth and Cape Breton between 1970 and 1976, consumption rates climbed by 23 per cent; along Nova Scotia’s south shore and in the Annapolis valley, the increase was 50 per cent. Consumer purchasing power resulted in increased liquor sales in the Maritimes, as Table One indicates.89

42 Prince Edward Island was also affected by these trends. In 1961, a delegation from the Maritime Provinces Board of Trade met with Premier Walter Shaw and his cabinet, urging them to study the liquor control regime with a view to liberalization.90 Ghosts of the past still loomed in terms of government-liquor industry relations; the PEI statute, reflecting prohibitionists’ concerns about corruption, dictated that no agent of any alcohol supplier that sold to the liquor commission could live on the Island.91 But by 1963, anticipating the celebration of Canada’s centennial four years in the future, the head of the Temperance Commission (soon to be renamed Liquor Control Commission), following a tour of NSLC facilities, was urging the government to budget for a new warehouse and liquor store in Charlottetown in order to promote the commission’s prestige, services and above all profits.92 As provincial budgets mushroomed with the growth of social welfare and economic development programs and as new sources of provincial revenues became available as a result of federal regional development policy, liquor commission profits and taxation on alcohol became relatively less important to gross general revenue. Yet absolute profit and taxation totals increased each year, and these were not revenues that provincial regimes wanted to relinquish.93

Table One : Alcohol Sales in the Maritime Provinces, 1962-78 (thousands of gallons)

Display large image of Table 1

43 Although Maritime governments rejected privatization of retail sales, their liquor commissions adopted the philosophy of British Columbia’s 1970 liquor inquiry: the fewer restrictions on alcohol sales the better.94 The general trend was to increased numbers of outlets, longer hours, more consumer choice, better service and self-service stores. Retail outlets were opened in shopping malls. The real price (based on the price of a gallon of alcohol as a percentage of per capita disposable income) of alcohol fell in the 1960s and 1970s, but consumers in the Maritimes paid the highest prices in Canada for their beer, spirits and wine and spent a greater percentage of disposable income for a given purchase.95

44 In Nova Scotia and PEI, customers in the early 1960s were still required to purchase annual permits. As in other parts of Canada, individual permits, a holdover from the early "control" decades, fell by the wayside. In 1954, one-quarter of Nova Scotia’s adult population purchased permits. In 1964, PEI issued nearly 9,400 resident permits, indicating that a good percentage of the adult population did not patronize liquor stores. However, more than 20,000 tourist permits were issued.96 One purpose of the permits had been to monitor individual purchases in order to counter resale bootlegging. Even when permits were abolished, individuals suspected of buying suspiciously large amounts were placed on interdiction or prohibited lists. In Nova Scotia, the RCMP and local police automatically sent the liquor commission information on court cases involving the Liquor Control Act and the police were informed when individual permits were "lifted".97 Permits also were useful for analysing distribution patterns. In 1950s Manitoba, for example, they revealed that ten per cent of customers purchased more than 50 per cent of the liquor. In late 1950s Nova Scotia, only 3 per cent of tourists purchased temporary permits. The New Brunswick Liquor Control Board enforced similar rules without permits, simply through the recommendations of local liquor store managers. In an era that promoted administrative fairness and civil rights, such practices were deemed arbitrary. Use of permits ended in Nova Scotia in 1965, and they were removed from the Liquor Control Act some years later.98

45 At the close of the 1970s, most drinking continued to take place at home and government liquor stores remained firmly established institutions. In the fiscal year 1979-80, PEI operated a dozen stores and New Brunswick and Nova Scotia 65 and 80 respectively.99 Polls indicated that most Maritimes, unlike most Quebecois and a majority of Canadians, were cool to the idea of beer sales in private corner stores, but they supported longer retail hours, greater product choice and the move to self-service. According to critics, self-service encouraged impulse buying. According to its supporters, it was simply good business sense, giving the consumer more freedom of choice.100 The minister in charge of the NSLC in 1971, J.W. Gillis, explained that its new stores "will resemble a supermarket. Products will be displayed on shelves and classified. He noted that women, increasingly, were making the purchases. Customers, provided with shopping carts, would now avoid traditional line-ups".101 Other than statutes, regulations, opinion polls and marketing studies, liquor commission administrators had another important source of information on trends in the industry: a national association of provincial commissions. The association served as not only a professional forum, but also a conduit of information on legislative and regulatory amendments in other jurisdictions. These were passed on to provincial cabinets.102

46 Increasingly, the Maritime provinces authorized greater varieties of licensed premises, such as taverns, clubs, restaurants and cocktail lounges.103 In addition, licensing incorporated greater procedural fairness such as public hearings and the right of appeal. All license bids would go through a public hearing. Yet the onus was still on the applicant to show why a licence should be granted, and third parties could voice objections. The licensing of taverns in Nova Scotia in 1948 and New Brunswick in 1962 created a new lobby, tavern owners, who established organizations and dealt with governments on matters such as pricing, customer service, hours of sale, entertainment and the admission of women. Once organized, tavern operators lobbied for further concessions, such as the right to sell cases of beer for off-premise consumption after liquor stores closed. They were soon joined by licensed lounge owners. Starting in 1961, the licensing of dining rooms in Nova Scotia favoured medium-sized and large hotels.104

47 Taverns, with their all-male and generally working-class clientele, continued to suffer from negative publicity despite rules against drunkenness or "notoriously bad characters". In 1961, the Associated Tavern Keepers of Nova Scotia, conscious of the open, "barn like" nature of their establishments, had pressed for the right to install partitions and to serve food.105 Waiters in the province had to be free of Criminal Code and Liquor Control Act convictions within three years of applying for their licences. In 1964 Nova Scotia amended its regulations in the attempt to improve tavern facilities, which were still strictly monitored in terms of customer service, space, cleanliness and staff. In 1961 Truro voted against licensed premises; Kentville and Mahone Bay residents voted otherwise. The town of Yarmouth, situated in an historically dry county, opened a tavern in 1963; three years later the dry town of Shelburne voted to keep taverns out. A liquor store opened in Wolfville in 1968 following a plebiscite, and in 1969 the town of Digby voted 2-1 in favour of a tavern.106

48 In the early 1960s, the brewers, with a view to expanding sales, had suggested that the presence of women in taverns would exert "a good influence with regard to conduct, habit of speech, dress and so on". In other Canadian jurisdictions prior to the Second World War, the question of admitting women to beer parlours invariably raised concerns about prostitution and immorality. Ending gender segregation was related to women’s labour force participation, which in Atlantic Canada rose from 23.3 per cent in 1961 to 37.4 per cent in 1976. New Brunswick taverns excluded women until the early 1970s, when "ladies beverage rooms" for women and male escorts were added to existing premises.107 Later in the decade, new taverns, serving both men and women, were opening in communities across New Brunswick and Nova Scotia and established taverns were converting. Licensing authorities also authorized later closing hours.

49 Prince Edward Island by the early 1970s had refused to authorize the sale of draught beer.108 Islanders could socialize at private clubs such as the Legions, yet the Temperance Commission chair in 1963 had complained that enforcement of liquor privileges in the clubs was exceedingly difficult. He suggested imitating the Nova Scotia and New Brunswick model of licensing and inspecting not only private clubs but also hotel and motel dining room licences. A more formal licensing regime was instituted the following year, with a total of 63 licensed clubs, military canteens and dining rooms/lounges issued by 1965. Lounge licences were issued only to holders of dining room licences. By 1970, Island residents and tourists could patronize a dozen lounges and less than two dozen licensed restaurants.109

50 A generation after prohibition, the spectre of the saloon still loomed large in the licensing and regulation of on-site drinking premises. In the Maritimes this meant that in addition to gambling, cashing cheques, extending credit, admitting women and accepting loans from breweries, tavern operators were forbidden from staging live music and entertainment, or, in beverage rooms where women were permitted, allowing dancing. Nova Scotia taverns in the 1950s were permitted to install television sets. By the late 1960s, voices in the media were speaking in favour of providing "nightlife" not simply for the tourist-consumer, but also the residents of the region. A writer in the Atlantic Advocate called for cabarets, wine with meals, dinner dances, sidewalk cafés and other signs of urbanity. Richard Hatfield’s colourful tourism minister, Charlie Van Horne, blamed New Brunswick’s substandard food and accommodations sector on hypocritical liquor laws.110 Beginning in the 1970s, licensing authorities allowed pool tables and other games, live entertainment (including exotic dancers in parts of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia) and dancing to recorded music in "discos" that cropped up in almost every town across the region. Many taverns were transformed from cinder-block warehouses into inexpensive nightclubs with live bands, dancing and young people lined up outside the door. During daylight hours they catered to office workers on lunch breaks.

51 One prediction of temperance organizations in the 1930s and 1940s was that the "liquor traffic" would press governments for the right to advertise products via magazines, newspapers, radio and television. Where forbidden from newspaper, billboard and exterior sign advertisements, brewing companies found more subtle ways of marketing, flooding the country with promotional items such as cigarette lighters, ash trays, calendars and bottle openers. Governments in the Maritimes in the 1940s and 1950s did not allow product advertising in media produced in the provinces, but New Brunswick tolerated institutional advertising by breweries. The Nova Scotia opinion polls of 1945-47 indicated that abstainers, rural people, women, those with higher incomes and the elderly were most likely to oppose beer product advertising.111

52 Maritime newspapers, including those that in the past had supported temperance and prohibition, had long supported the right to earn advertising revenues from brewers, distillers and wine producers. In the 1950s, the prospect of distillers sponsoring events such as the Dominion Drama Festival or engaging in charitable activity was still controversial in elite circles. Manitoba’s Bracken Report of 1955 recommended that no product or institutional ads be allowed other than interior signs in liquor stores, and that provincial governments strive for a uniform liquor advertising code. In other provinces, notably Quebec, advertising rules were more open. When the Macdonald government was rumoured to be considering legalizing liquor advertisements in 1952, Nova Scotia church and temperance leaders protested.112 The following year, 17 daily and weekly newspapers came out in favour of institutional liquor advertisements.113

53 By the 1960s, liquor advertising was big business across North America. Advertising flooded in from outside the Maritimes in the form of magazines. Alcohol manufacturers, like the tobacco industry, insisted that the purpose of advertising was to protect brand loyalty, not to increase sales. In the 1960s and 1970s, federal regulations banned brand advertising of spirits on radio and television114 The Rowe report had recommended an advertising code for Nova Scotia newspapers.115 In order to reassure the New Brunswick Temperance Federation, the WCTU, Acadian temperance organizations and Baptist and United Church clergy, Robichaud from 1962 onwards refused to allow liquor advertising in New Brunswick’s print and electronic media. This led to a dispute with provincial newspaper publishers such as Wardell, whose Atlantic Advocate had carried institutional beer advertisements. As the province barred internal advertising, one regional brewery in the 1970s broadcast ads from Quebec radio and television stations. Prince Edward Island continued to ban alcohol advertisements in newspapers printed in the province and screened its residents from out-of-province electronic advertisements. Nova Scotia by the early 1960s permitted print ads, but liquor advertisements, promotional items displayed in licensed premises and newspaper ads for lounges were all subject to licensing board approval. Brand or product advertising could not encourage the use of alcohol, or depict open bottles or women in "immodest, vulgar or provocative dress or situations". Billboard advertising, at least up to 1966, was illegal.116

54 Meanwhile, in the 1960s and 1970s new alcohol problems were identified by experts and interest groups, resulting in new national and provincial legislation and programmes. Following the Second World War, expert opinion on alcohol abuse was increasingly medicalized, with less emphasis on morality and more on the physical and psychological risks of heavy drinking. Although acceptance of the disease concept of alcoholism was uneven in Canada, governments began to pay lip-service to the concept.117 Statistics indicated that accidents, morbidity, mortality, cirrhosis and psychiatric admissions were often linked to alcohol, and experts warned that the rate of alcoholism rose with consumption rates. Beyond individual problems, alcohol abuse also created difficulties for the social welfare and criminal justice systems. This information was considered important by provincial governments. Ontario, for example, founded the Alcoholism Research Foundation (ARF) in the early 1950s to conduct research and to treat and rehabilitate abusers of alcohol. The mandate of Manitoba’s 1954 liquor inquiry included the study of the relevant literature in the medical and social sciences. Both entities were attempting to find a "middle way" between what the new experts considered the biased views of both temperance and alcohol industry advocates.118

Table Two : Alcoholism per 100,000 Persons Aged 20 and Over

Display large image of Table 2

55 By the late 1960s, non governmental organizations, health care professionals and provincial officials were supporting the decriminalization of public drunkenness, an offence that continued to provide the bulk of jail commitments. Instead of the "revolving door" of arrest and incarceration (usually through inability to pay fines), chronic drunkenness offenders, reformers urged, should be handled as medical cases, treated through counselling, clinics and half-way houses.119 A study of the "public inebriate population" of Nova Scotia revealed that only a minority of more than 6,000 people sentenced to jail between 1973 and 1975 had been interviewed by addictions counsellors.120

56 The medical establishment tended to ignore alcohol abusers, and mental and general hospital staff were hesitant to admit them. Expanded treatment implied not only in-patient and out-patient facilities, but also changes to criminal and public health legislation and an expanded role for non-governmental organizations such as Alcoholics Anonymous. Organizations such as the Ontario ARF and Nova Scotia’s Alcoholism Research Commission, organized in 1959, attempted to create greater sympathy for alcoholics and increased political support for treatment. North American alcoholism literature was portraying most alcoholics not as "rummies" living on the street, but as employed, married men who were not selfish, immoral or weak, but victims of a disease.121 Nova Scotia’s commission, with a physician as executive director, estimated in 1961 that the province contained several thousand alcoholics, most of whom either did not recognize their condition or concealed their disease owing to social disapproval.122 Policy was shaped by the ongoing public debate, especially in the media, on the social costs of addictions. The federal commission on the Non-Medical Use of Drugs, for example, which had been established to examine the legal status of "soft" drugs such as marijuana, pronounced alcohol Canada’s worst substance abuse problem.123

57 PEI had organized an Alcoholism Treatment Foundation in 1966; a decade later it had grown into a crown corporation, the Addiction Foundation.124 The Island government, which depended on federal support for its developing social welfare system, resorted to an innovative fiscal mechanism to finance rehabilitation. Beginning in 1971, it levied a surcharge on alcoholic beverages. PEI and Nova Scotia had long charged a health tax on liquor sales. The Brewers’ Association of Canada marshalled evidence to claim that ear-marked taxes of this nature were questionable, and that the surtax unfairly penalized beer, a beverage of moderation, and benefited distilled spirits. A similar plan was deferred in New Brunswick in 1972.125

58 Nova Scotia led the region by establishing an alcoholism council in the late 1950s. Two decades later it had broadened into a provincial drug dependency commission, with a programme of research and a network of local committees and staff. The initial focus was on detoxification, which professionals viewed as a temporary measure. The Halifax out-patient clinic which dealt with several hundred patients and their families yearly was joined by a similar centre in Sydney in 1970. Administrators did not judge these programmes a success: there were no detox centres in the province, counselling case loads were light, research efforts were token and most alcoholics remained unidentified and without treatment.126 During the 1970s, discussion of alcohol problems expanded beyond alcoholics to include "problem" and heavy drinkers. Public health research suggested that high aggregate consumption levels were a problem for society as a whole. In 1980, the provincial cabinet was briefed on the yearly cost of alcohol abuse in Nova Scotia, which was estimated as $170 million.127

59 New Brunswick did not organize an alcohol commission until the early 1970s, following a task force which toured the province seeking information on the medical and social costs of alcohol abuse.128 The ensuing report suggested that the province had 17,000 alcoholics and that liquor was a leading public health threat.129 By the early 1980s the Addiction and Drug Dependency Commission maintained three rehabilitation centres and eight treatment centres. Male clients outnumbered female by more than 5 to 1. In 1980 most clients had less than a Grade 12 education and were single, separated or divorced; 56 per cent were labourers or tradesmen. Their net per capita income tended to be less than $800. Including family members, this network dealt with 3,000 to 4,000 New Brunswickers each year but admitted less than 400 to treatment.130

60 On PEI, as in other provinces, a majority of individuals incarcerated in provincial jails had been charged with public drunkenness, a situation that encouraged the Campbell government to plan for their diversion and treatment. A half-way house for problem drinkers opened in 1966. A task force on corrections in 1968 summarized the status of alcoholics on the Island and made recommendations for future programmes. Using the well-known Jellinek formula, the report estimated that there were close to 800 alcoholics in the province. Persons in contact with the law because of alcohol misuse or admitted to treatment in 1966 and 1967, according to Premier Campbell, amounted to a slightly larger number.131 Campbell’s government organized an Alcoholism Treatment Foundation, with a main treatment facility in Charlottetown handling both "withdrawal" and rehabilitation cases.132

61 The governments of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, while liberalizing alcohol policy, attempted to placate dry opinion with modest support for temperance education. Nova Scotia’s revised liquor control statute of 1948 provided for a full-time temperance educator. Working within the Department of Education, this official visited provincial high schools, "giving sane, scientific advice to the students on the use of alcohol", and urging the formation of branches of the Allied Youth, a temperance organization.133 By the late 1960s PEI had 4,000 Allied Youth members. New Brunswick in the 1950s provided a small annual grant to the province’s anglophone temperance federation, and Robichaud’s later reforms included the appointment of an alcohol education and rehabilitation director.134 The Maritime approach impressed the Bracken commission, which recommended a similar approach for Manitoba, as well as integrating "alcohol education" (not "scientific temperance") into the school curriculum and teacher training.135

62 By the 1960s, the more religious and moralistic commentary of temperance, most of which had been aimed at the "liquor traffic" and its allies in government and the media, gave way to activity by more secular, voluntaristic and community-based organizations such as Alcoholics Anonymous, local councils on alcoholism and counselling and treatment staff. The new approaches to alcohol problems focused on alcoholics and problem drinkers, not the liquor industry or alcohol itself.136

63 Temperance groups attempted to adapt some of the new discourse on alcoholism to their own purposes. In 1960 the Maritime United Baptist Convention, citing the "social blight" of alcoholism, called on governments to restrict, not increase, drinking facilities.137 Traditional temperance voices had warned that corrupt government-liquor industry relations would further "the liquor traffic’s plot against youth".138 Yet in the age of liberalization, pressures mounted for lowering the age of majority, the voting age and the legal drinking age from 21. The demographic and political impact of the Baby Boom made these questions particularly germane. In New Brunswick by the early 1970s, more than half of the population was under 25. Conservative opinion held that a lower age would lead to more drunkenness, disorder and impaired driving. The opposing "integrationist" theory promoted the idea that normalizing alcohol use among young adults would decrease irresponsible drinking.139

64 Changes to the minimum legal drinking age in Nova Scotia in 1971 and New Brunswick in 1972 came as a result of amendments to the age of majority and were not directly connected to the issue of alcohol. In 1967 Prince Edward Island lowered its voting age to 18. New Brunswick voters, in a plebiscite, rejected a similar proposal. PEI lowered its drinking age to 18 in 1972.140 Following the lowering of Nova Scotia’s drinking age to 19, tavern and lounge operators feared suspension or loss of licences for violations. In response the NSLC began to issue proof-of-age cards to young drinkers.141 Despite the attention in the media to marijuana and other illegal drugs, alcohol was the drug of choice for Canadian youth, and unlike their parents and grandparents, they preferred to consume it in public.142 Nova Scotia’s chief liquor inspector captured this sentiment in a 1973 memo. The arrival of gender-integrated taverns and bars, "coupled with a more permissive trend in the social habits of today’s youth has resulted in a more liberal attitude towards liquor, and it is now evident that beverage rooms and lounges particularly have become the ‘in’ place for young people to gather".143 Research in the 1970s indicated that Canada’s young people did most of their drinking in bars and taverns.144

65 One exception to liberalization was the implementation of amendments to the Canadian Criminal Code which sought to control impaired driving. The issue was not new: the Code had been amended as early as 1921 to deal with the menace of drunk drivers, and by the 1940s temperance organizations loaned out educational moving pictures on the issue. Temperance advocates, along with physicians, bar associations, the police and the insurance industry, were among the earliest supporters of testing the blood or breath of suspected impaired drivers. In 1961 Nova Scotia’s Rowe commission had recommended against breath testing, based on cost, lack of scientific agreement on effectiveness and civil liberties concerns. By the early 1970s, Statistics Canada reported that between one-seventh and one-fifth of fatal and non-fatal automobile accidents involved alcohol. In contrast to newspaper editors, insurance industry representatives, police and medical officials who placed the blame on individual drivers, temperance advocates, and a number of alcohol researchers, pointed to the increasing availability and social acceptance of alcohol.145

66 Beginning in 1969, it was an offence to operate a vehicle with a blood alcohol content of more than 0.08 per cent, and an offence to refuse to submit to a breath test. The outcome of enforcement and awareness campaigns is beyond the scope of this study, but preliminary observations can be based on the Nova Scotia experience. The RCMP, which patrolled the provincial highways, and municipal police departments acquired breathalyzer equipment and trained officers and technicians. The Mounties were earlier to receive the equipment and training and kept better records on traffic offences. In contrast to small and medium-sized town police, they were more likely to stop, test and charge individuals. According to a Nova Scotia Drug Dependency Commission study, municipal police were more restrained and selective in enforcement. Interestingly, none of the magistrates interviewed for the study believed that the breathalyzer provisions were a real deterrent. Impaired driving offenders, like most persons in conflict with the law, were primarily young, male and either unskilled or semi-skilled, but unlike the typical offender, they enjoyed "social stability" such as a high rate of employment and marriage. They tended not to regard their actions as deviant and rejected allegations that they were anything other than social drinkers.146

67 By the mid-1970s, police were requesting mobile "roadside" testing equipment to assist in their war on the drunk driver. Amendments in 1975 gave the police the right to take breath samples as part of spot checks and introduced a mandatory jail sentence for a second offence.147 Provincial governments also implemented mandatory alcohol awareness courses for drivers convicted under the breathalyzer section. In the 1970s, aside from localized controversies over licensed premises and debate over enforcement of the "breathalyzer law", the Maritime public generally supported continued liberalization. But governments and liquor commissions had to act cautiously, as suggestions for cold beer in liquor stores, Sunday sales or the sale of beer and wine in corner stores usually provoked controversy in the media. Although church organizations voiced concerns into the 1980s, traditional temperance was largely dead as a movement.148 As Robert Campbell notes for British Columbia, through liquor commission reports, commissions of inquiry, task forces, addictions foundations and anti-impaired driving campaigns, the state was producing new knowledge on alcohol. The key point in this knowledge was that alcohol was a legitimate beverage for most adult Canadians.149

68 At the end of the 20th century the process of liberalization and homogenization was continental, even global.150 Canada’s alcohol distribution and consumption practices still retained regional and provincial distinctions, such as the hotel beverage rooms of the West and Ontario, Ontario’s private wine outlets and beer stores, and Québec’s dépanneurs which sold beer to go. In terms of beer marketing, both off and on-premise sales appealed to regional or provincial brands and imagery (for example, Schooner ale, Alpine lager and the invented "heritage moments" of the Keith’s India Pale Ale television advertisements). Maritime liquor consumption rates remained below the Canadian average, and there were some slight variations from other provinces in terms of licensing and retail outlets. But minor differences aside, the distribution of alcohol was characterized by the commercialization and homogenization that critics had fretted over in the 1960s. In an era when the federal and provincial states were expected to be more active in economic planning and development, health care, education and social welfare, most Maritimers supported relaxing state moral surveillance of drinking. Fulfilling consumer desire, not exercising control of a socially problematic commodity, was now the guiding principle of provincial liquor policy. Changes to legislation permitted home brewing and wine making (but not home distilling), brew pubs and micro breweries ( but no brew-your-own micro breweries) patio bars, licensed sporting events, food and soft drinks served to children and spirits in taverns and draught beer in lounges. Distinctions between taverns and bars became blurred. By the 1990s public lounges and private clubs were also equipped with legalized gambling devices, video lottery terminals (VLTs), a lucrative source of revenue for bar owners and provincial governments.