Building a "New Nova Scotia":

State Intervention, The Auto Industry and the Case of Volvo in Halifax, 1963-1998

Dimitry AnastakisTrent University

1 WHEN THE FIRST VOLVO "Canadians" rolled out of the company’s new assembly facility in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia in the summer of 1963, the event was heralded by Premier Robert Stanfield as the harbinger of a "New Nova Scotia", which would quickly vault the province to the forefront of the manufacturing age. This sentiment was echoed by Volvo officials as well, who saw the plant as a crucial beachhead into an important foreign market. As the earliest non-North American-owned automotive facility built on this continent (Honda opened its first American facility in 1982), the plant emerged as a result of the federal and Nova Scotia governments’ efforts to actively encourage industrial development. Yet Volvo’s experiment in North America fell far short of the governments’ lofty goals: operated as a simple assembly venture, the facility reached a maximum production of never more than a few thousand vehicles and employed only hundreds of workers in the province. After its initial burst of enthusiasm, the Volvo Corporation itself exhibited a lukewarm attitude towards the plant, providing only limited investment and support for its Canadian offspring. By the late 1990s, overcapacity in the auto industry in Europe and North America, reorganization of Volvo and the new realities of the quickly changing global auto industry resulted in the parent company’s decision to close the plant. In 1999 Volvo was purchased by Ford of the United States, allowing the company to import the cars directly from Sweden duty-free under the 1965 Canada-United States Automotive Products Trade Agreement (Auto Pact). A year later in 2000, this arrangement ended with the demise of the Auto Pact at the World Trade Organization.1

2 The story of the Nova Scotia Volvo plant is part of the end of "national" auto strategies and auto companies and the emergence of a world industry. The Volvo experiment is also the story of state intervention in the Canadian auto industry from a regional perspective. Provincial and federal government industrial policies provided incentives to the company to locate in Nova Scotia during a particularly activist period of state initiatives in industrial development. The federal government’s auto policy was shaped by determined civil servants in Ottawa who were keen to generate as much economic activity as possible in this important sector of the Canadian economy. Interventionist industrial policy was central to the new Liberal government of Lester Pearson, and the creation of the 1965 Auto Pact, a key driver in encouraging automotive production, reflected this new approach. In Halifax, provincial politicians and policy-makers were also keen to develop Nova Scotia’s industry beyond traditional resource extraction, and utilized the newly created Industrial Estates Limited (IEL) to foster their activist bent. This new attitude was epitomized by the provincial government of Robert Stanfield. The Volvo plant provides a case study of the motives of these economic policy-makers. Volvo’s experience in Nova Scotia points to some obvious questions: How did Volvo fare at the hands of the federal government in comparison with the rest of the automotive industry, which was overwhelmingly located in central Canada – principally Ontario? On balance, given that the venture lasted for nearly four decades, could the Volvo plant be considered a successful venture? Why did Ontario plants thrive under the Canadian state’s central automotive policy – the Auto Pact – but the Volvo plant did not? How did the Halifax plant fit into Volvo’s corporate strategy? In the final analysis, were the policies implemented by the two governments to persuade Volvo to locate and remain in Nova Scotia a success?

3 By focusing on the impetus to create the plant and its initial years of operation, this article attempts to provide some understanding as to why federal and provincial policy-makers encouraged Volvo to establish in Canada and supported the plant with incentives and tariff concessions. It also gives a brief history of the facility’s operational life and provides some reasons as to why the plant eventually closed. In a period characterized by the federal government’s efforts to improve Canadian industry and the economic status of the Atlantic provinces through the creation of the departments of Industry and Regional Economic Expansion – and similar efforts by the Nova Scotia government such as IEL and the Voluntary Economic Planning Board – the establishment of Volvo in Dartmouth-Halifax stands out as a fascinating case in the industrial evolution of both Canada and the Maritimes. Although both the federal and provincial governments were instrumental in facilitating the establishment of Volvo in Nova Scotia, the operation was beset by numerous difficulties, including issues surrounding the plant location and operation of the facility, a changing market that put Volvo products at a disadvantage and the failure to achieve new or a broader range of production in the facility. In the end, however, these problems only partially contributed to the demise of the plant. The story of Volvo Halifax is a unique tale that illustrates the limits of 1960s-era federal and provincial industrial development initiatives in the rapidly changing and highly competitive global auto sector. Although instrumental in luring the plant to Nova Scotia, limited tariff reduction measures, small-scale direct infrastructure concessions and local boosterism could not sustain Volvo’s small Halifax operation, a reflection of changing trade regimes, the large economies of scale required by the evolving automobile industry and the shifting worldwide strategy pursued by Volvo by the 1990s.

Federal and Provincial Intervention in the Canadian Auto Industry: 1958-65

4 Although it remained a unique industrial experiment in North America for decades – it was the first true "transplant" in the U.S. or Canada, long before the arrival of Japanese, German and Korean plants – the Volvo experience in Nova Scotia has received surprisingly little scholarly treatment, especially from historians.2 Indeed, state intervention and the auto industry has been a focus of historians and political scientists of a number of countries almost solely on a federal or national level. During the 1960s, governments in Canada, Brazil, Australia, Mexico and other Latin American countries took a much more active role in their auto industries. All of these countries shared common traits: widespread penetration by American multinational auto companies, little or weak domestic manufacture and parts production and balance of payments difficulties owing to its dependence on foreign automotive imports. In response, the range of intervention by these host countries included increased local content rules, wholesale nationalization of industry (or the threat thereof) and innovative approaches to import substitution. These efforts met with varying levels of success, and provide a basis for comparison of state intervention in national auto industries.3

5 Between 1962 and 1965, Canadian policy-makers sought new methods to encourage industrial development in the automotive sector, primarily through the use of duty-remission schemes that were export incentives.4 Responding to demands for change in the industry from workers, firms and academics, the governments of Progressive Conservative John Diefenbaker and Liberal Lester Pearson created these programs in an effort to spur auto industry production and solve an increasingly difficult balance-of-payments problem. In October, 1962, the Diefenbaker Conservative government created a special "remission plan" for automatic transmissions, an item which had been predominantly imported by Canadian industry until that time. Manufacturers were now forced to pay the 25 per cent duty on automatic transmissions (a measure that had not been enforced previously), but received a 100 per cent rebate (and a 100 per cent rebate on up to 10,000 imported engine blocks as well) for every dollar increase in the amount of Canadian goods they exported over and above a 12-month base period. The plan worked well, and by the time the Liberals came to power in 1963, the rebate scheme was having a positive impact on the industry.5

6 The newly elected minority Liberal government, also searching for ways by which to reduce the massive deficit on current account goods, took aim directly at the auto industry. In October 1963, C.M. "Bud" Drury, the minister of the newly created Department of Industry, introduced a plan that was intended to both alleviate the balance-of-payments burden and boost production even more than the Conservative plan had. The Liberal’s new plan was a drastic expansion of the Conservative’s rebate scheme. Now, for every dollar of exported goods over and above the base year, manufacturers would be allowed to remit an equal amount on dutiable exports; the plan was also extended to all automotive exports. It was expected to run for three years and could, according to Drury, lead to an increase of between $150 and $200 million dollars in exports, a substantial chunk of the expected $500 million deficit for 1963-64.6

7 While the Conservative plan had raised few American eyebrows, the Liberal’s broad, far-reaching scheme provoked an immediate response. The Americans were dismayed at the Canadian unilateral action, and chided the Canadian government that "any measures adopted to deal with Canada’s balance-of-payments problems should not artificially distort the pattern of trade or interfere with the normal exercise of business judgement". The U.S. State Department warned that American trade laws left open the possibility that a private interest might take exception to the plan, which could force the American government to take retaliatory measures.7 By April of 1964, the American predictions were realized. That month, the Modine Manufacturing Company of Racine, Wisconsin initiated a complaint with the U.S. Treasury Department that, under U.S. trade law, the Canadian program constituted an unfair trade advantage. Section 303 of the United States Tariff Act was a little-used clause which had been previously invoked in only the most serious cases. It required the government, if after finding in an investigation that a foreign government was providing unfair "bounty" or "grant", to slap prohibitive countervailing duties on the products being imported. With a private corporation forcing the U.S. government’s hand because of Canadian unilateral actions (while the Canadian government steadfastly defended the program), relations between the two governments became strained. Both governments quickly realized that unless they resolved the issue, a trade war in the important automotive sector would be unavoidable.8 As a result, the two sides negotiated the far-reaching and innovative Auto Pact, which erased tariffs for automotive trade between the two countries as long as each side achieved certain requirements.

8 Volvo’s interaction with the Canadian state emerged parallel to and as a part of the federal government’s automotive policy. As we shall see, Volvo asked for and achieved special status within the Canadian government’s automotive policy and then continued to receive special treatment under the new automotive regime that governed automotive-state relations after 1965. Canadian state planners were willing to "bend the rules" to ensure that Volvo could operate in this country; in exchange, the presence of the company provided jobs and investment and promised to be a catalyst for further industrial development.9

9 While this explains the federal government’s interventionist role in the auto industry, it does not explain the efforts of Nova Scotia’s government to play a role in luring Volvo to Nova Scotia nor the motives and policies of the Nova Scotia government concerning provincial intervention in the auto industry. Indeed, while a considerable body of literature has emerged on the question of federal and provincial intervention in regional economic development in Nova Scotia and Atlantic Canada in general, no study has explicitly addressed the auto sector.10

10 In 1956 Conservative Robert Stanfield won the Nova Scotia provincial election on a platform that espoused industrial renewal based on effective state intervention in a number of sectors in the Nova Scotia economy. Stanfield was determined to diversify the province’s economy, which had suffered the collapse of traditional Nova Scotia industries – especially coal. Since the end of the Second World War, Nova Scotia had faced increasing unemployment and slowly declining economic prospects. As part of its platform, Stanfield’s new government implemented a host of economic policies designed to assert government planning more forcefully in directing the provincial economy. These policies began to take a clear shape after 1960, and chief among them were the Voluntary Planning Act of 1963, which was intended to improve business-government communication, and IEL, the provincial development Crown corporation.11

11 The creation of IEL stemmed from the Stanfield government’s 1956 election promise to create a "Nova Scotia Industrial Development Corporation", to be financed equally from government coffers and the public sale of shares in the company. But the provincial development plan took a different turn, as the government feared that selling shares to the public could cause undue complications and conflicts between creating jobs or making profits for the company. Instead, in 1957 the government enacted legislation to create IEL, an idea patterned upon a similar program in the United Kingdom. The wholly owned Crown corporation was backed by a $23 million government investment. Initially, the company was intended to build industrial parks to lease space to companies, but IEL also built factories for companies that leased at rock-bottom prices. One advertisement for the company proclaimed: "Industrialists! Have IEL finance and build your plant in Nova Scotia! The company will develop the site of your choice, finance and build your plant, lease it to you at low rental and, if and when you wish, sell it to you at book cost". Eventually IEL became a direct lender to companies, both for capital projects and for equipment.12 Volvo was an early and longstanding beneficiary of IEL’s largesse, both in the form of loans and support for plant, and, as we shall see, in facilitating direct subsidies for transport costs.

12 IEL’s first president was Frank Sobey, the scion of the supermarket chain, who was appointed in 1957. Considered a titan amongst Nova Scotia’s business elite, Sobey worked at the unsalaried position until 1969, during which IEL attracted numerous business to the province, including textile, rubber, food processing and, of course, automotive companies.13 IEL’s "philosophy and policy" as Sobey stated in a 1968 Financial Post interview, was based on four points: to maintain the interest and active participation of prominent Nova Scotia businessmen on its board of directors, to maintain a small but effective development and office staff, to make an aggressive search for new manufacturing enterprises on an international scale and to keep an eye out for Nova Scotia firms that might be able to profit from IEL. To that end, the Crown corporation attracted companies from outside Nova Scotia and Canada and helped a number of Nova Scotia firms through direct lending and providing facilities. By 1968, more than 60 firms had been supported by IEL initiatives, and Sobey boasted that nearly 10,000 jobs had resulted from IEL agreements and projects, adding $40 million to the province’s revenue.14

13 In the case of Volvo, both provincial policies (IEL’s direct support for plant and investment) and federal policies (tariff concessions) were key to attracting it to the Dartmouth-Halifax region in the early 1960s. Yet Volvo’s decision to come to Nova Scotia stemmed from more than just the incentives offered by the two governments.

Volvo Arrives in Canada: 1962-65

14 Volvo, which means "I go" in Latin, was founded in 1924 by Assar Gabrielsson and Gustaf Larson, two employees of ball-bearings maker SKF, and it became an independent company in 1935. From the first hand-built model in the 1920s, the company grew impressively. By 1962 Volvo production reached over 100,000 cars, buses and trucks at 13 facilities in Sweden employing 18,000 workers. The company’s ethos was very conservative and focused on quality: there were only 15 different vehicle designs in Volvo’s history, the vehicles were offered in only seven different colour choices and 11 per cent of its employees were involved with product inspection. As one excited Volvo Canada employee later reported, "Volvo rejects more component parts than any other car maker in the world".15

15 Volvo Canada was incorporated on 21 July 1958, a year after the first importation of Volvos to Canada by a British Columbia firm which arranged to distribute the cars nation-wide. After 1959 Volvo sales increased dramatically, and the company responded by setting up its Canadian administrative headquarters in Toronto, which established a dealer network. With the nation-wide growth in Canadian sales, in early 1962 the company began to consider setting up a plant in Canada. The company’s president of Canadian operations, D.W. (Pat) Samuel, a New Zealander, was key to hatching the agreement that saw Volvo arrive in Canada.16 Samuel was dispatched by the parent company to negotiate with the federal and provincial governments towards gaining better terms for the company to facilitate the establishment of a plant and ease its initial production.

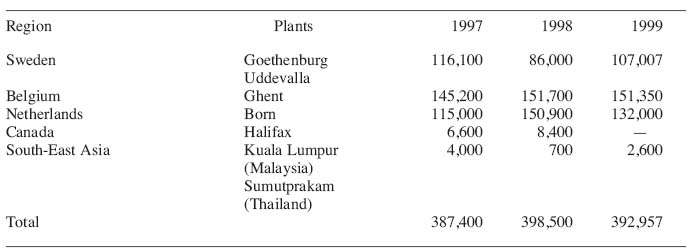

16 Samuel arrived in Ottawa in October of 1962 to begin discussions with Diefenbaker’s Minister of Finance George Nowlan. Volvo had decided upon setting up their operation in Nova Scotia, Samuel told Nowlan, due to the province’s relative proximity to Sweden and its year-round ice-free ports, a prerequisite for a venture which was to be heavily dependent on imports from the home country. The company was keen to begin production as soon as possible, Samuel argued, but the current content regulations for automotive production were unrealistic for an operation as small as Volvo. Under the 1936 Tariff Act, which still governed the auto trade in 1962, the most-favoured-nation (MFN) tariff rate was 17.5 per cent for all autos and most parts. In order to gain duty-free access for imported parts, a company was required to achieve 40 per cent Commonwealth (essentially Canadian) content for companies producing 10,000 units, 50 per cent for companies producing between 10,000 and 20,000 units and 60 per cent for companies producing over 20,000 vehicles (see Table One) .17 In Ontario, the tariff schedule had the effect of facilitating much Canadian production by the established U.S.-owned manufacturers, but would be punitive for any other company in its initial production stages. For a company like Volvo, which had the added cost of importing from the distant locale of Sweden, it was impossible to reach the 10,000 vehicle mark in the first period of production. In other words, without some special dispensation, Samuel argued, Volvo could not make a go of it.

Table One : The Canadian Auto Tariff of 1936

Display large image of Table 1

17 Moreover, Samuel informed the minister that Volvo’s initial plan was to be a bare-bones operation, one in which the company simply reassembled partially knocked-down (PKD) vehicles. There would be few Canadian parts added to the major vehicle components shipped from Sweden and bolted together in Nova Scotia. The Canadian plant would not even paint the vehicles, as the parts would arrive already coloured in Volvo’s famous seven-colour range of choices. The operation was to employ Canadian labour and include some Canadian parts (headlights, bumpers and perhaps tires) but, again, the scale and size of the operation made it difficult to reach even basic Canadian content levels. While the facility would be an important step in Nova Scotia industrial development, Volvo in Nova Scotia was not going to be the next Windsor, Oshawa or Oakville – at least not yet.18

18 Nowlan was sympathetic. As a native Nova Scotian and a "red tory," he believed in the utility of interventionist programs that could help areas such as his home province.19 The Volvo idea also fit well within federal plans for the entire Canadian auto sector. A 1961 Royal Commission on the Automotive Industry chaired by University of Toronto economist Vincent Bladen pointed to the need for exports in the industry, which was hampered by short production runs designed for a small market and a dependence on U.S. parts imports.20 This dependence on U.S. parts imports stemmed from Canadian tariff law, which allowed duty-free imports for any parts of "a class or kind" not made in Canada. The almost entirely U.S.-owned Canadian assembly industry took advantage of this situation to import massive amounts of vehicles and parts. As a result, the Canadian industry faced a difficult situation: If the market for autos in Canada performed poorly, employment and production declined. If the market performed well, massive U.S. parts and vehicle imports would send the Canadian trade balance spiralling downward. By 1962, auto imports accounted for 90 per cent of Canada’s nearly $500 million trade deficit. In response, the government had created the duty-remission scheme that allowed companies to increase their imports of transmissions and engines duty-free if they increased their exports of other parts from Canada.21

19 While Volvo could not take advantage of the transmission/engine program (the company did not yet have facilities in Canada), Nowlan was eager to find some relief for Volvo so that it could begin production in Canada. Thus, the company was granted a number of tariff concessions from the Diefenbaker government to ease their way into production, as Volvo represented a "special case" that involved the establishment of new enterprise in Canada. In return for assurances that Volvo train 500 Canadians as mechanics and hire at least 400 workers at their new plant, the company received remission of duties on bodies, engines and parts through a process similar to the transmission/engine program. The company’s Canadian content requirements were to be slowly increased as Volvo adapted to the Canadian market.22 In Nowlan’s view, Volvo gained the benefit of "temporary tariff arrangements", and would be "increasing their purchases in Canada quite quickly once they become well established". Initially, Volvo was allowed to begin production with virtually no Canadian content while importing their parts duty-free.23

20 Samuel also held talks with the Nova Scotia government regarding the Volvo plan. In September and October of 1962, Samuel met with IEL President Frank Sobey, IEL General Manager R.W. Manuge and Nova Scotia Minister of Trade and Industry E.A. Manson in Toronto and Montreal to make his case. Samuel made it clear that the company’s decision hinged on two factors. First, the company needed to ensure that it received a preferential rail shipping rate for Volvo cars from Halifax to Toronto and Montreal. Current freight rates, argued Samuel, were far too expensive for the company to profitably transport their vehicles to the lucrative central Canadian market. Second, Volvo would not come to Nova Scotia unless it received a favourable loan to secure an appropriate facility in Halifax or Dartmouth. The two issues, Samuel hinted, were linked.24

21 Provincial government and IEL officials were eager to facilitate the company’s arrival, which would provide a significant boost to Nova Scotia manufacturing. While trade minister Manson stated that the provincial government had no authority with rail shipping rates, IEL’s participation could circumvent any problems. After bringing the issue to the attention of the federal cabinet, meeting with Canadian National Railways representatives to seek the lowest price possible and presenting the idea to the IEL board, it was decided that IEL propose to pay a "partial indemnity" to subsidize the shipment of vehicles to central Canada. On 22 January 1963, the Nova Scotia Cabinet approved the partial indemnity, which was also approved by the IEL board the next day. Through IEL, Nova Scotians would subsidize the transportation of Volvo cars from the Halifax/Dartmouth plant to the tune of $9.67 for every vehicle shipped to Toronto and $9.33 for every one shipped to Montreal. The indemnity for shipping Volvo cars westward was capped at $150,000 over the next three years – thereafter, it was to be open-ended, a considerable expense if Volvo were to expand its production, but one that IEL and the government were willing to bear if the facility took off as they hoped.25

22 The site for a plant was also to be supported by Nova Scotia tax dollars through the granting of loans to the company to secure a facility. Samuel and company representatives investigated a number of sites in late 1962, and decided that Halifax-Dartmouth was the best location: since the company was dependent on shipments from Sweden, and Halifax was the closest major North American port to Sweden, it made sense to locate there.26 The city’s good road and port infrastructure also helped to convince Volvo. In January 1963 Samuel informed IEL that the company had leased a 55,000 sq. ft. dockside former sugar refinery owned by Acadia Sugar Refineries Co. in Dartmouth for $2 million for three years. For its part, IEL loaned the company funds for the lease at very favourable terms (8 per cent) until a plant could be built "to order" by the Crown corporation.27 The new Volvo facility was little more than a converted warehouse. With the rail transportation issue and lease with IEL worked out, Volvo began working closely with Nova Scotia trade minister Manson to identify Nova Scotia companies as potential suppliers.28

23 Halifax was also ideal because of its lower labour costs, especially in comparison to those in the traditional Canadian automotive-producing communities in Ontario. Volvo officials were well aware that the average hourly industrial wage in Halifax in 1963 was $1.86 while the average hourly wage of a GM worker in Oshawa was between $2.16 and $2.29.29 Thus, Nova Scotia’s proximity to Sweden was not the only locational benefit bestowed upon the company as the Halifax location would produce a significant labour cost advantage. By February 1963, Canadians were being trained in Sweden in anticipation of the plant’s opening.30

24 On 21 February 1963, the announcement of Volvo’s Nova Scotia plant was made simultaneously in Halifax and Ottawa. Publicly, Samuel and the company enunciated a number of reasons for Volvo’s decision to locate in Nova Scotia. In interviews with the financial press, Samuel stated that Volvo’s move was because of the potential for both the market in Canada and production in Nova Scotia: "The main one is that we think we have a car that is suitable for the Canadian market and Canadian conditions . . . . I also believe that to sell a car in volume in Canada you must build it in Canada". He also saw a "growing nationalistic spirit" among Canadians, and that the plan was an "experiment" for the parent company.31 Samuel boldly predicted that the plant would produce 5,000 vehicles in its first year and 7,500 in its second. Dartmouth Mayor I.W. Akerley’s efforts in the final negotiations was also pointed out by Samuel as being pivotal to Volvo’s decision to locate in the area as was the help of the provincial government – especially IEL.32 While he did not mention IEL’s role in facilitating the export of Volvo cars to central Canada, Samuel did state that Halifax’s excellent rail connections to central Canada and the eastern United States had played a role in the company’s decision.33

25 Other Volvo company officials were equally enthusiastic at the new facility’s prospects. "You must appreciate the fact", stated Jan Nytzen, a Volvo controller, "that in Sweden we are regarded as a conservative company. We are not given to flamboyant promotions or ideas. Yes, most certainly we are serious about our Canadian operations. We hope we are here to stay, and grow".34 Gunnar Engellau, Chairman and Managing Director of Volvo, explained in February 1963: "We are establishing our first overseas factory in Nova Scotia because we like the environment very much. Everybody is so enthusiastic there – and that is important. Your government has given us good co-operation. You have an excellent year-round harbour. And the labour situation is very attractive". Moreover, market factors were also a part of the decision. "We have chosen Canada", said Engellau, "because we have the kind of cars that should give us special standing there – and because, too, I have always had a strong feeling for Canadians". 35

26 The Volvo announcement sparked a burst of Nova Scotia pride. Volvo’s arrival was likened to an "economic miracle" by Stanfield in the legislature, an event he "could hardly believe. . . . For years we have all dreamed of something like this, and now the dream has become a reality".36 The Halifax Chronicle-Herald also captured the spirit unleashed by the announcement: "All Nova Scotians should rejoice in the good fortune of Dartmouth, chosen yesterday as the location for a branch assembly plant of the giant Swedish car manufacturer, Volvo".37 Volvo’s Samuel heralded the choice of Nova Scotia as a testament to the "inherent traditions of quality of workmanship dating back to Nova Scotia’s period of eminence as one of the world’s biggest builders of wooden ships". Nova Scotia was, according to Samuel, "The cradle of Canadian craftsmanship".38 Samuel himself was feted by the Chronicle-Herald as a man of "confidence" who helped embody the spirit that Volvo was bringing to Nova Scotia.39

27 Editorialists also praised the federal government and its helpful co-operation with the province: "There is plain evidence that there exists an effective co-operation between federal and provincial development authorities, as a result of which restless, searching capital may be convinced that investment here is worthwhile". There was praise too for the federal Minister of Finance: "Mr. Nowlan . . . who negotiated the temporary tariff concessions which make attractive the importation of the semi-finished product from Sweden, has demonstrated once again the necessity and desirability of public incentives for private enterprise". The Volvo announcement also justified IEL and the lease-back principle: "For all its criticism levelled at it from time to time, [IEL] remains the most effective self-help organization that we in Nova Scotia have yet established".40 The sentiment was echoed in the legislature, where Stanfield stated: "Volvo’s decision to come to Nova Scotia will cause many industrialists, whom we have not yet been able to interest in Nova Scotia, to look seriously at our province now".41

28 The official opening of the Dartmouth plant in June 1963 was a colourful affair. Dignitaries in attendance included Stanfield, the president of Volvo, Gunnar Engellau, and even Prince Bertil, the eldest son of Sweden’s king, who cut the ceremonial ribbon and led dancers at a formal ball. Stanfield was heralded as the founder of a "New Nova Scotia", and the booming Swedish presence personified by the Volvo endeavour was not lost upon the premier. During the ceremony, Stanfield joked that the province’s name should be changed to "New Sweden". The plant represented what a visiting American economist saw as a "Second Wind" for the province, a spurt of industrialization which would compel Nova Scotia to the front ranks of Canadian industrial development.42 Volvo’s presence was increasingly being seen as "not only an economic boost but a psychological lift" for the Halifax region, Nova Scotia and the Maritimes. Volvo management stated that the future was bright for the facility and that there was "no limit to our expansion possibilities". Privately, Volvo representatives hinted to IEL officials that the company intended to have other products besides autos built at the facility, and that Volvo might be "coming to us soon to arrange for a permanent plant".43

29 Stanfield himself was presented with the very first Volvo that rolled out of the Dartmouth plant. He turned the vehicle over to the government and then purchased another Nova Scotia-built Volvo for his own use and suggested other cabinet ministers do the same "to set an example for the province".44 Some of them took Stanfield up on the suggestion: the Financial Post reported that at least one Nova Scotia cabinet minister, future premier G.I. Smith, purchased a vehicle from the company and stated "I regard it as a Nova Scotian product".45

30 The arrival of Volvo prompted an economic mini-boom in the region. Within weeks of Volvo’s start-up, a number of other automotive and automotive-related companies announced their intentions to establish operations in Halifax, including Continental Can Co. and Surrette Battery.46 Within months, William Docsteader, sales manager for the company, stated publicly that he expected many different firms to follow Volvo to Dartmouth. The company’s move to the area was, in his opinion, not only big news in Canada, but "big news all over the world".47 In an effort to spur such growth, Volvo worked with Nova Scotia trade minister Manson to organize a Volvo-oriented trade show for prospective firms to understand the company’s supplier needs.48

31 Volvo’s arrival also generated interest from other non-North American auto companies about the possibility of setting up facilities in the province. In March 1963, IEL General Manager R.W. Manuge quietly held talks with Reneault and Peugot, and the province was actively recruiting Toyota through Canadian Motor Industries Limited, an outfit fronted by Toronto entrepreneur Peter Munk, which was also trying to establish auto assembly in the province.49 In April it was reported that the United Kingdom’s main auto association, the Society of Manufacturer’s and Traders Limited (SMMTL), was canvassing Nova Scotia locations for potential future sites. While the Volvo move had turned some heads in Europe, a 10 per cent surcharge on European imports by the Diefenbaker government had also generated newfound interest by British companies in Volvo-like knock-down operations in Canada.50

32 Notwithstanding the initial enthusiasm for the prospects of the Volvo plant and the development it might generate, the plant’s beginnings were humble. The first crew of Volvo Nova Scotians received 12-weeks training. None had any experience in automotive assembly, yet many had backgrounds as mechanics. Assembly operated on a one-station system as opposed to a fully automated assembly line.51 Only 5 of the first 100 employees were from Sweden. Initially, the company produced 15 to 20 vehicles a day. The company assembled imported body shells from Sweden, which were matched with Canadian-assembled Swedish engines and mechanical parts plus some parts supplied by Canadian manufacturers.52

33 Although it was a relatively small operation (especially in comparison to the Ontario facilities of the Big Three U.S. manufacturers), the United Auto Workers was keen to organize the facility; in September 1963 the company and the union reached a three-year agreement that was ratified by 98 per cent of the workers in the plant and created UAW Local 720. Although the UAW did not achieve wage parity for the Dartmouth plant’s workers with those in Ontario, as it had originally hoped, the initial contract did produce good results in wages and benefits for the first Volvo workers.53 In December 1963, six months after the first two-and four-door Volvo "Canadians" rolled out of the warehouse, Canadian content in the Dartmouth-assembled Volvos, including labour, reached 30 per cent, while production went from 55 to 66 cars a week.54

34 By then, the new Pearson government had announced its expanded duty-remission scheme, which allowed automotive companies to boost their imports if they exported more of their products. The plan was aimed at the U.S.-owned companies in Ontario, which were importing massive amounts of parts for use in their Canadian plants. Volvo, with its parent company in Sweden, could also take advantage of the expanded remission scheme, and was actually the first company to do so. In late November 1963, Volvo Canada announced that its parent firm would purchase $100,000 worth of rear axles from Hayes Steel Products of Thorold, Ontario; this purchase allowed Volvo Canada to import duty-free a corresponding amount from its home country.55

35 The company quickly took advantage of the U.S. market under the scheme as well. Gunnar Engellau, president of parent company AB Volvo, who appeared at the Dartmouth grand opening, stated that the company was "definitely interested in the export market". He was hopeful that the company could develop a market for its Canadian-built cars among Commonwealth countries, and that the Nova Scotia plant would produce for the U.S. market.56 In December 1963 Volvo Canada announced that 75 Volvos would be sold in New England. Although Volvo already sold 18,000 vehicles in the U.S., Canadian sourcing was seen as a way to boost production in Canada and a way to save on tariffs by taking advantage of the export-incentive nature of the duty-remission scheme. Moreover, Volvo had faced continuous product shortages in the United States.57

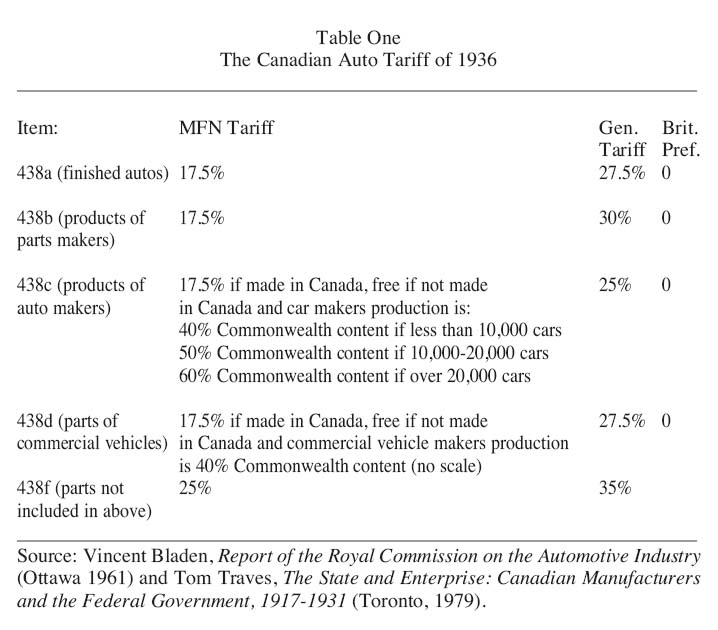

Table Two : Volvo Canada, Production and Sales, 1960-65

Display large image of Table 2

36 Notwithstanding the initial production increases and potential for the export market in the U.S., Volvo’s output in Canada fell far from the company’s early, optimistic predictions of Volvo Canada President D.W. Samuel. Instead of 5,000 vehicles in 1963 and 7,500 in 1964, Dartmouth had not even broken the 4,000 vehicle mark by 1965. By June 1965, Canadian content was up to approximately 40 per cent and Volvo was producing 75 cars per week, boosting its annual production to 3,500 cars.58 Employment, which had originally been targeted at 300-400, had stalled at 101 employees. Faced with the difficulties of slow production and disappointed expectations, the company also faced the uncertainty created by a significantly altered automotive trade and regulatory regime after 1965.

Volvo Under the Auto Pact, 1965-95

37 On 16 January 1965 Prime Minister Lester Pearson and President Lyndon Johnson signed the Canada-United States Automotive Products Trade Agreement at Johnson’s "L.B.J. Ranch" in Texas.59 The agreement aimed to rationalize the North American industry for the benefit of producers and consumers alike, cement the strong continental ties and spirit of cooperation between the two countries and resolve a difficult issue in the U.S.-Canadian trade relationship. The creation of the Auto Pact was precipitated by the unilateral Canadian efforts in 1962-64 to boost Canada’s flagging auto industry and redress its rapidly deteriorating current account balance, a deficit that was largely the result of massive auto and parts imports from the United States. When the U.S. and Canadian governments realized that the issue might deteriorate into a full-fledged trade war between the two countries, negotiations began in earnest.60

38 By the fall of 1964, the two sides came to an agreement. Duty-free trade in autos and parts was to be limited only by the different provisions governing each country. The agreement stipulated that imports to the U.S. could come only from Canada and required 50 per cent North American content. In Canada, only certain bona fide manufacturers that maintained a ratio of production to sales and a base Canadian value-added rate were allowed to import from any country, though the U.S. was the most likely country of origin. This intergovernmental agreement was complemented by a series of agreements between the Canadian government and the U.S.-owned Canadian subsidiaries of the major auto producers referred to as "letters of undertaking". The companies promised to boost their investments in Canada over the next three years and to increase the Canadian content of their production by 60 per cent of whatever increase might occur in their sales in a given year.61 Instead of unrestricted free trade, the Auto Pact provided for a tightly managed limited sectoral trade area in autos and parts.

39 As the two governments and the American Big Three auto makers had been the instigators of the new agreement, it was primarily designed to benefit the U.S.-based companies, largely to the exclusion of offshore manufacturers. While the Canadian government consulted extensively with the Canadian Big Three presidents, Volvo’s representatives did not participate in the Auto Pact discussions. But with Volvo in mind, the Auto Pact did include a part which stipulated that the government of Canada could designate a manufacturer "not falling within the categories" in the Annex as being entitled to duty-free treatment. This allowed the government to designate Volvo under the agreement at a 40 per cent Canadian value-added (CVA) rate (being the dollar amount of Canadian labour or parts added to a vehicle), which was in keeping with the company’s previous content commitments and did not preclude the company’s participation in the new regime.62

40 Although the new agreement provided immense benefits for GM, Ford and Chrysler, as they could now import and export across the border tariff free as long as they maintained their commitments in Canada and content requirements in the U.S., Volvo would benefit as well. The company could now import duty-free from Sweden, as the Canadian negotiators had ensured that the Canadian aspects of the agreement applied to third countries. In other words, Volvo could import parts from Sweden duty-free if they continued to maintain their Auto Pact commitments. This meant massive savings, and provided an opportunity for further growth as long as Volvo increased its Canadian presence.63

41 In its first years of operation, the Auto Pact proved to be immensely successful as expansion in the auto sector was impressive. The main players in the industry, the American Big Three, expanded their facilities greatly in the period immediately following the agreement’s signing. One Department of Industry official estimated that of the over 50 major automotive-related projects announced by October of 1965, nearly half were by subsidiaries of U.S. companies. The official noted that in many instances, the companies specifically declared that the reason for the growth was the automotive agreement, though many had been planned before 1965 because of growing Canadian demand.64 During the first two years of the Auto Pact, every major manufacturer, including Volvo, opened or expanded at least one major facility in Canada, which accounted for much of the $260 million target in the letters of undertaking.65 By the late 1960s, the Big Three had all boosted production and increased their investments. In 1969, the Canadian auto industry produced over one million vehicles for the first time, a massive increase over the 325,000 total vehicles produced in 1960.

42 Nonetheless, companies did have problems meeting their commitments under the agreement. A slowdown in the U.S. market threatened to cool the expected export programs of all the manufacturers.66 Volvo, too, faced difficulties, although its problems were of a different nature. In late 1965, Volvo Canada sought permission from the government to alter its original commitments. Because of the company’s particular circumstances, the government’s requirements under the letters of undertaking signed by the company were less than that expected of the Big Three. While it needed to maintain its ratio of sales to production and CVA for the base year of 1963-64, Volvo was only required to increase its additional CVA by 40 per cent of the growth in its market, as opposed to the 60 per cent expectation placed upon the Big Three. Moreover, the company’s expected additional investment by 1967-68 was only $600,000 (compared to the $228 million expected by the Big Three). With the downturn in the Canadian demand for Volvo products, which matched the U.S. slowdown, the company hoped to lessen the government’s requirements.

43 At the end of 1965, the company informed government officials that they would only achieve their targets if they engaged in "uneconomic practices" and that they would not meet their growth targets unless they received some concessions from the government.67 In response, Drury informed company officials that the government agreed in February 1966 to some changes in its requirements. Although Volvo was required to maintain the production to sales ratio and the base CVA, the government loosened the Canadian content and additional CVA expectations. Instead of 40 per cent Canadian content, Drury informed Volvo president Karl Kohler the company would be allowed to hit a 25 per cent Canadian content target by July 1966, which would rise annually by 5 per cent so that the 40 per cent figure would be achieved by 31 July 1969. The government also agreed to allow Volvo to invest its additional $600,000 by the end of July 1969.68

44 While the tariff relief was welcomed by the company, continued disappointing production figures sparked stories that Volvo intended to flee to greener pastures. Compounding these rumours was the fact the company’s lease at the Atlantic Sugar Refineries Plant was expiring in 1967 and that the company did not wish to renew the lease with Volvo.69 Moving the company’s head office to Toronto in 1966, and setting up a major parts depot at a new $1.2 million facility in Toronto, did not help matters. In early 1966 Volvo Canada President Kohler was forced to quell rumours that the company was moving to Quebec; he publicly stated the company was eager to remain in Nova Scotia.70

45 Volvo did move, but only to a new facility across the harbour from Dartmouth. After difficult deliberations over choosing a new site and a host of false starts, in 1966 Volvo took possession of a new and larger plant on Halifax’s Pier 9. Built by IEL and leased to Volvo, the facility was a 190,000 sq. ft., $1 million investment by the Crown corporation.71 Incentive was further provided by the Halifax City Council, which offered a 10-year tax-benefit package. The plant’s location allowed Volvo to load shipments directly into the facility.72 Again, this move by Volvo was heralded as a signal that the company was in Nova Scotia to stay, although the company did not own the building outright.

46 By 1968 Volvo, like the rest of the industry in Canada, had improved its position. That year, the new plant produced nearly 5,000 Volvo 140 Series vehicles and had increased turnout from 360 cars a month to over 420; in November, in fact, the company boosted production at the Halifax facility from 120 to 130 cars a week. However, this optimism for Volvo’s prospects did not stop company president Kohler from reminding Nova Scotia Premier G.I. Smith that the plant required provincial assistance "to further strengthen our position in Canada, and thereby create more jobs and opportunities for your area".73

47 The company’s request for further assistance was realized when Volvo officials informed government representatives in 1968 that another expansion was necessary due to the growth in demand for Volvo cars in the Canadian market. The request was accompanied by the threat of departure: Volvo’s Kohler informed IEL board members that "we realize that IEL and NHB [National Harbour Commission, the co-owner of the Pier 9 facility] have done their utmost in the past to keep Volvo in the Maritimes, but if expansion space cannot be provided now or in the future, we must take a closer look at our future growth potential elsewhere in Canada".74 After considering a proposal that would have seen a new facility of either 20,000-vehicle or 50,000-vehicle capacity production built somewhere else in the Halifax area, the company asked for loans to expand their present Pier 9 facility by 60,000 sq. ft., and this was authorized by IEL in 1970.75 With the Pier 9 expansion, annual production capacity at Halifax expanded to 15,000 vehicles. Although they did not pursue an entirely new facility, the company’s fortunes seemed to be positive: employment had expanded to over 300 people and, in January 1971, the plant launched production of the new Volvo 142E, the first computer-controlled fuel-injected car in North America. In August, the 40,000th vehicle produced by Volvo in Halifax rolled out of the plant.76

48 Nonetheless, rumours continued to persist that the plant’s position was precarious, a situation which was exacerbated by labour difficulties. In 1974 UAW Local 720, in a strike position following the end of their contract, were locked out by the company after negotiations broke off over the issue of overtime rates. Volvo representatives made it clear to Nova Scotia officials that they could not operate the facility under the overtime provisions being demanded by the union; Volvo executives were, in the view of IEL President Dean Salsman, "very disturbed and concerned about the negotiations".77

49 IEL and government representatives were not sympathetic to the union’s position, and went to great lengths to show that Volvo’s employees were paid as well as their counterparts in central Canada. They feared that further labour disruptions would lead to the company’s always-rumoured departure from Halifax, prompting development minister George Mitchell to admit to Minister of Labour Walter Fitzgerald: "We are always very concerned about this organization and are afraid that if they suspect that they will have many more labour difficulties they may well close down their operation".78 IEL’s Salsman was even more blunt: "I am wondering whether the international union representative, doing the negotiations for the Volvo employees, is negotiating in their best interest".79 Salsman also lamented the influence of Ontario in the negotiations: noting that the union was demanding "more than the [B]ig-[T]hree are paying in the Windsor area", Salsman felt that it was "unfortunate that someone from another province can dictate the conditions for a plant in Nova Scotia".80 In the end, Volvo and the union reached a compromise and the plant reopened after a 13-week labour disruption.81

50 Along with labour disputes, the early 1970s brought missed opportunities at Volvo. In late 1971 the Department of National Defence informed Nova Scotia Minister of Development Ralph Fiske that the army had purchased two Volvo trucks to be tested as part of its plan to replace 3,000 aging three-quarter tonne trucks. When the news became public in mid-1973, Volvo officials pressed IEL and Nova Scotia government representatives, who in turn attempted to influence federal officials, particularly those Members of Parliament from Nova Scotia such as Allan MacEachen, to ensure that Volvo be chosen for the contract. Such an order would mean an expansion of the Volvo facility to begin producing trucks (perhaps on a permanent basis, hinted Volvo officials), and two to three years of employment for 80-100 additional workers.82

51 Nova Scotia pressure, while not falling on deaf ears, was ineffective in securing the contract for Volvo. Although MacEachen assured provincial Minister of Development George Mitchell "I will watch this matter very closely and do what I can to be of assistance", the army chose Chrysler products for the project. The decision was bitter for provincial and IEL officials: IEL President Dean Salsman complained that federal Industry Minister Alastair Gillespie took "a very casual approach" to the province’s concerns. Mitchell complained that Gillespie was uncooperative and failed to give the province "any real information" on the contract. In the end, provincial and Volvo officials were informed that the contract was based on the military’s desire to use a standard North American commercial vehicle for logistical and financial reasons. Such a contract would have improved the long-term fortunes of the plant facility, and the loss was a significant blow the plant’s prospects.83

52 One factor that had led to the loss of the military truck contract was Volvo’s lack of Canadian content in its vehicles, a significant criteria stipulated by the army for the truck order. After 1965, the Volvo operations continued to have difficulties in achieving substantial levels of Canadian content (including labour); it steadily decreased, hitting a very low 20 per cent by 1970. Little of the in-vehicle content was from Nova Scotia sources, and much of this was due to the company’s very high quality standards and low-price demands. For example, in 1970 the company informed the provincial government that of the few Canadian items used in the cars, they were now purchasing 75 per cent of their batteries from Ontario due to the lower prices. Nova Scotia-based Surrette Battery Co., which had been heralded in the 1960s as a success story linked to the Volvo enterprise, could no longer compete on quality or price.84 Other local companies, such as Bluenose Woodworkers, Maritime Canvas Converters and Halifax Metalworkers had also lost contracts or been rejected because of poor quality or an inability to meet the company’s price demands. The Volvo operation’s small scale also curtailed Canadian content: in some instances, local companies were not interested in the short production runs that were typical of a Volvo order.85

53 A number of other problems beyond the plant’s control hindered its operation during the early 1970s. A 1971 report from the Centre for Automobile Safety in Washington, DC claiming that Volvo’s cars were not as safe as advertised was widely publicized, and prompted the Halifax Mail-Star to question the reliability of Volvo Canada vehicles.86 In its critique of Volvo safety, the paper also erroneously stated that the company was receiving "advances" from IEL. In response, Volvo Canada strenuously defended the quality of its cars and the integrity of its workforce, and vehemently repudiated the assertion that it had received any inappropriate "advances".87 In the fall of 1973 a strike that closed the Port of Halifax led to production delays and the eventual closure of the Volvo plant for two weeks in November.88 Both incidents added to the difficulties the company faced during that period.

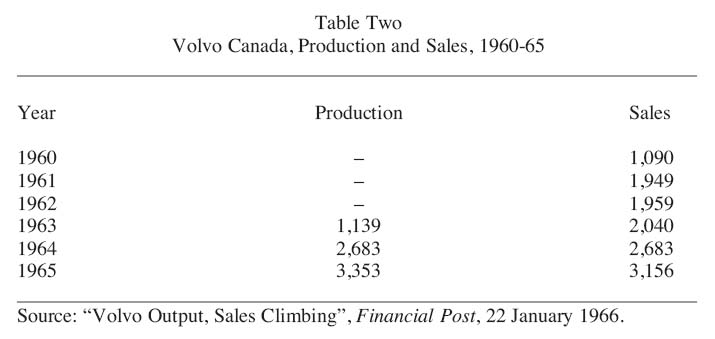

54 Notwithstanding these setbacks, in 1975 the company reached its peak production and assembled more than 13,000 units (see Table Three). For the remainder of the decade, the plant produced between 7,000 and 12,500 vehicles every year.89 By 1980, while the rest of the automotive industry was in the depths of a severe recession, Volvo representatives were cautiously optimistic of the plant’s long-term prospects. Although output usually remained less than 10,000 vehicles per year, Volvo’s sales in Canada were increasing, which led to further production increases and underlined the importance of consistent output to meet that domestic demand.90

Table Three : Volvo Production in Canada, 1970-98

Display large image of Table 3

55 By the mid-1980s, however, Volvo Canada was producing only a fraction of what had been expected in 1963. In-vehicle Canadian content was barely five per cent and the vast majority of the Canadian value added at the Halifax plant resulted from labour costs. Ironically, tires from Michelin, which had been the other significant provincial effort to attract new industry to the province, were used on Nova Scotia Volvos – but they were imported from Germany rather than being delivered from the province’s own plants in Pictou County and Bridgewater.91

56 This lack of content curtailed Volvo exports from Halifax to the United States. While Canadian officials gave the company preferential treatment to import from Sweden without achieving its content requirements, it was prohibited from exporting to the U.S. if it did not achieve a 50 per cent "North American Content" threshold, which it never attained. As a result, the company was unable to use Halifax as a source for exports to the U.S. which, by the mid-1970s, had become its largest market. To alleviate this difficulty, amid great fanfare in 1974 the company broke ground on a US$100 million plant in Virginia that was intended to produce 100,000 vehicles and employ 3,500 workers within two years. Yet by 1976 the partially completed plant was still not producing vehicles, a victim of the recession in the auto industry and increased prices for Volvo products that slowed sales. The plant was virtually abandoned until the early 1980s, when the company decided to source bus production at the facility. This venture soon fell on hard times as the bus market became increasingly competitive and crowded. In 1986, after building 120 buses, Volvo announced that it would cease production at the site; by the next year the plant was empty.92

57 A new Halifax plant did not really provide the production that was necessary for the Canadian market either. In 1987 Volvo and IEL announced that the company would leave the Halifax plant at Pier 9 to move to an entirely new facility constructed at a cost of $13.5 million by Volvo at Bayer Lake Industrial Park. Volvo’s move was sweetened by further tax breaks given by the municipal government, which required the company to pay only a fraction of its municipal tax bill for the next ten years. While some municipal councillors voiced concern about the continuing breaks for the company, especially after it was reported that Volvo Canada had been increasingly profitable during the 1980s, the municipal measures passed with little dissent.93 During the move to the new facility, Volvo planned to reduce its workforce, which led to further labour difficulties at the plant as a wildcat strike ensued. Production reached near-record lows, and Volvo workers recall the move with bitterness.94 Their bitterness would reach a breaking point only a few years later. By the mid-1990s, the company faced new challenges in its North American strategy – one which required drastic changes to its Halifax plant.

The End of Volvo’s Canadian Adventure, 1995-98

58 On 8 September 1998, Volvo announced that it was closing the Bayer Lake assembly plant, stating that it was no longer "economically viable" to produce cars in Halifax for the Canadian market. Volvo Canada President Gord Sonnenberg stated that the facility was simply too small for the long-term plans of the company. A plant that produced less than 10,000 vehicles was no match for one that produced over 100,000.95 Moreover, the company argued that economies of scale were key to their tariff concerns. Even with the 6.1 per cent Canadian tariff for complete vehicles, it was still more efficient to build the cars in Sweden at the large-scale plants and ship them to Canada. This was particularly true for the U.S. export market. The closure also provoked rumours that Volvo was in greater financial trouble than the company was letting on and that the Halifax facility was being shuttered in part to address its over-capacity problems in Europe.96 There was also speculation that the company was being pursued as a takeover target.

59 Reaction to the announcement was one of resignation. While many Haligonians lamented the departure of the company – another Swedish firm, Ikea, had just left the Halifax area – the province and city were keen to downplay the significance of the move. Nova Scotia Development Minister Manning MacDonald stated that the city was "buoyant" enough to take care of itself, while Halifax Mayor Walter Fitzgerald immediately set about to create a task force to consider options for the 223 employees who would lose their jobs.97

60 In the wake of the closure announcement, management-worker relations came to a boil after the company offered a severance package that was deemed unacceptable by the employees. A 31-year veteran at the plant stated: "It’s sad that a company which demanded so much loyalty from its workers has so little to offer in return". He felt that the company’s initial severance offer would have cut his pension practically in half. In response, the workers occupied the plant in October 1998. In the words of Larry Wark of the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) union, "The frustration has been building up and building up, so finally the decision was made this week that people were tired of waiting, tired of being stalled. Most of them were concerned that we’d get too far down the line, and Volvo would just get all its good cars out, get them into the marketplace and at any point in time, tell us that bargaining would never begin again. So the decision was made to occupy the plant".98

61 The Volvo workforce in Halifax ended its takeover of the plant and removed a blockade at the main gates after the CAW’s negotiating team announced it had reached a tentative agreement with management on pension and severance packages. The CAW had dispatched a mission to Sweden to try to save the plant, but it had been unsuccessful. Instead, the union negotiated better terms surrounding the pension and severance agreements and the workers returned to work peacefully. On 11 December 1998, the last Volvo assembled in Canada, a four-door S70 sedan, quietly rolled out of the facility and was donated to the IWK Grace Health Centre by the company and the workers.

62 Why did the Volvo venture in Canada, which had begun with such optimism and enthusiasm, end so sadly? The project, which was heralded as representing the start of a "New Nova Scotia" in 1963, ended with an unhappy and very public labour dispute and plant takeover. How did a venture which had the benefit of federal and provincial programs to spur industrial development come to such an ignominious end? Notwithstanding the plant’s uneven existence, on balance can Volvo’s Canadian venture be considered a success?

63 Some have viewed the story of Volvo in Canada as an example of corporate exploitation. Critics of the company argue that "Volvo did not ‘bring a little bit of Sweden’ to Nova Scotia; instead the company quickly adapted to and exploited the peripheral conditions of its new location".99 The company took advantage of a weakened economic jurisdiction and lower labour costs, and gained the benefit of preferential treatment in tariff, capital and infrastructure policies from federal and provincial governments – all in exchange for the promise of booming employment and increased industrial development. But that promise never materialized. Volvo never employed more than 200 people directly in the plant; its partial-knock-down system resulted in few secondary jobs in either parts or assembly; the plant produced barely 10,000 vehicles in an average year, a shadow of the over 100,000 vehicles produced at Volvo’s European operations.

64 Others might compare the shortcomings at Volvo in Nova Scotia with the success of other assembly facilities in Ontario, and place the blame at the feet of a central Canadian-oriented federal government. After all, provincial representatives often felt slighted at the hands of the federal government when it came to government contracts – such as the military truck order – or felt that Ontario conditions were dictating the terms of Nova Scotia labour. When Volvo announced the Halifax closure, local reporters noted that the executives came to the press conference "with their Ontario public relations experts in tow".100 Criticism towards the federal government, however, or its automotive policy could not be too harsh. After all, Volvo had been included in the Auto Pact, something not even the Honda and Toyota facilities in Ontario could boast.101 Furthermore, Volvo had been given preferential tariff treatment by the federal government from the outset and had even gained further concessions under the Auto Pact. Instead, when it came to federal automotive policy, Volvo’s status as a "regional" producer actually resulted in beneficial treatment. Volvo’s demise was not a result of regional discrimination in favour of Ontario.

65 The end of Volvo’s Canadian venture can also be seen as a failure in corporate strategy. Although Volvo was keen to exploit a new market, it never committed adequate resources to the plant or made a concerted financial investment in the Halifax operation. Such an effort may have paid off in far greater sales in Canada and a significant growth in Volvo’s overseas market, but the company’s managers were unwilling to commit wholeheartedly to their Canadian facility. Volvo’s reluctance to boost its facility in Canada contrasted sharply with the Canadian Big Three plants in Ontario and Quebec, particularly after 1965: the GM, Ford and Chrysler facilities received billions of dollars in new investment, not only in response to the companies’ requirements under the Auto Pact but because these firms understood the benefits of sourcing production in Canada.102

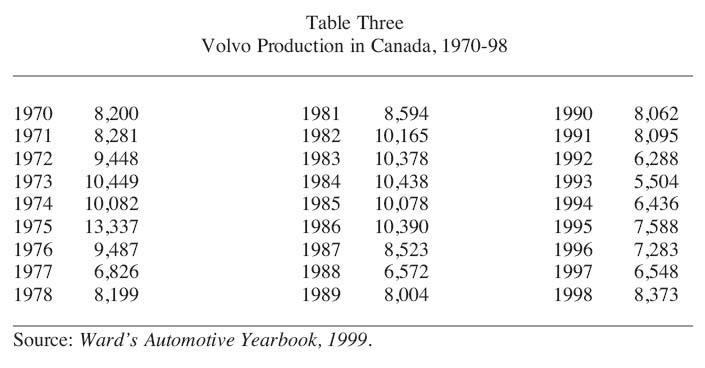

66 Volvo faced constraints, of course, that largely precluded it from taking more advantage of its Canadian facility. First, Volvo did not have the benefits of proximity that the Big Three boasted. Windsor, where much of the Canadian auto industry was located, was only across the river from Detroit, America’s "Motor City". Halifax, on the other hand, was thousands of miles from Sweden – there was no chance of developing "just-in-time" production techniques or of merging production schedules and operational plans of Volvo’s Canadian and Swedish facilities, as happened with the Big Three after 1965. By the 1990s, the Halifax operation remained a far-flung outpost of the company, a remnant of a bygone era where a niche independent auto company such as Volvo had attempted to build its own multinational presence.103 While Volvo’s other "foreign" plants established during this period – Ghent, Belgium in 1965 and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in 1967 – continued to function, their survival reflected local considerations (European integration and tariff requirements to be in Southeast Asia) rather than any coherent international policy.

67 Second, Volvo’s Halifax plant was caught in a proverbial catch-22. The plant originated under tariff rules designed for small-scale production for the Canadian market. It lacked the economies of scale necessary to take full advantage of its Auto Pact status to export into the U.S. market; doing so required hitting the necessary 50 per cent North American regional content guarantees under the agreement, a prohibitively expensive undertaking for a company of Volvo’s size at a plant of Halifax’s stature. Volvo’s corporate managers likely saw little benefit in boosting investment or production in a facility that was originally intended as a beachhead into the Canadian market and which remained as such for all of its existence. With the concessions and incentives provided by the federal, provincial and municipal governments, it cost the company little to maintain the facility. In return for these generous inducements, Volvo provided nominal employment and minimal Canadian value added while gaining a measure of good corporate citizenship.

68 Indeed, in providing continued preferential treatment, both the federal and provincial governments showed that they could only do so much in an automotive industry that experienced so much change during the period under examination. Tariff concessions and plants built for Volvo did provide an incentive for the company to set up operations in Nova Scotia but governments could not control the market or the management decisions of the company. In this case, state intervention was beneficial in attracting the firm to Nova Scotia but could do little after the plant was established in the face of the vagaries of the marketplace or the quickly changing world auto industry. State intervention can be successful, but it can only be as successful as the partners with which it is dealing.

69 At its core, the departure of Volvo from Halifax did not happen because Nova Scotia was a poor choice for an auto plant or because Nova Scotia auto workers were not capable or effective. Nor did Volvo’s departure hinge upon unrealistic tariff rules or overly demanding content regulations by the federal government. While many of the location and labour difficulties the plant faced certainly curtailed the growth of its production, Volvo left Halifax because of a rapidly changing world automotive industry, because it could not take advantage of new trade regimes to exploit its largest market, and because the economies of scale, which were realistic in 1963, were utterly unrealistic in 1998.

70 In the end, the plant itself may not have been a success, but it did provide employment for hundreds of workers in the Halifax area for over three decades. The plant takeover illustrates how valued those jobs were by the employees. As Anders Sandberg noted before the closure of the facility, "There are several reasons why Volvo workers stay in what appear to be less than satisfying jobs. The wages are high by Nova Scotia standards. There is little else to do. The workers are relatively old and know few other skills; in 1994, the average age was close to 50 years. These are facts of which the workers are critically aware and constantly reminded by management".104 For these people, Volvo’s Halifax venture had nothing to do with corporate exploitation: the company provided jobs where none had existed before, and the governments’ willingness to use taxpayer funds to provide incentives was not a case of Volvo "taking advantage" of Canadian largesse but a genuine effort at economic development that did not, in the end, have a lasting effect.

71 In the long run, the battle over the closure of Volvo Halifax may have been moot. In 1998 the Ford Motor Company purchased the auto assembly operations of Volvo of Sweden. With the new arrangement, it is highly unlikely that Ford would have continued to operate the facility, given that they could import Volvo cars directly from Sweden into the United States duty-free under the Auto Pact because of the change of ownership. Even the demise of the Auto Pact, following the 2000 World Trade Organization ruling that the agreement was contrary to international trade laws, would have likely led to the end of the plant. Without the preferential tariff treatment afforded by the agreement, Volvo would not have continued to build cars at its tiny Canadian operation. Corporate consolidation and the globalization of the automotive industry would have quickly shuttered the plant, something that sporadic production and uncertain facilities had not managed to do in nearly four decades.

Notes

Volvo’s production by plant/region (see http://www.autointell-news.com/european_companies/volvo_cars/volvo-mfg/volvo-manufacturing.htm):